Abstract

The special issue on Ambivalent Sexism (Glick and Fiske 1996, 1999, 2001) reflects the current landscape of ambivalent sexism research. This introduction reviews the theory, exploring the particularly insidious case of benevolent sexism. Next, it presents the included papers, which range broadly, but generally fit one of three research streams in the development of ambivalent sexism research. Some papers focus on converging correlations, exploring ambivalent sexism’s relation to other ideologies and cultural dimensions. Other papers demonstrate causality in context, revealing impact on targets and the prescriptive power of ambivalent ideologies. A third line documents converse causality, illustrating impact on perceivers’ self processes. Finally, we discuss possible future areas of research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Ambivalent Sexism Theory (AST; Glick and Fiske 1996, 1999, 2001) bridges two separate research traditions in social psychology, sexism and close relationships, by showing how societal dominance integrates with intimate interdependence. Prior to AST, a social psychology textbook would have depicted two disparate research areas, sexism in the prejudice chapter, and heterosexual close relationships in a separate chapter. A reader would have formed completely opposing views of male-female relations: from the first, that sexism entails hostile attitudes and competitive behaviors toward the other gender, and from the second, that heterosexual close relationships are steeped with love and affection. How could these apparently contradictory literatures come together? In positing the co-existence of both antagonistic and benevolent ideologies toward the other gender, AST melds previously separate intellectual approaches to studies of gender relations. Subsequent research established that societies across the world reconcile male societal status and the genders’ intimate interdependence by holding ambivalent gender ideologies (Glick et al. 2000, 2004).

This introduction reviews AST, especially the paradox of benevolent sexism; then, as AST develops its conceptual trajectory, describes three research streams represented in the current articles; and finally, points to future directions where new research is needed.

Review of Ambivalent Sexism Theory

Hostile and benevolent sexism stem from three existing social realities in which men are the dominant group, most divisions of labor delineate along gender lines, and men and women depend on each other for sexual reproduction and intimacy. First, historically and cross-culturally, male domination in various institutions (e.g. political, economic) creates a patriarchal system in which men routinely occupy high status. Furthermore, biological differences between males and females produce social distinctions between men and women that manifest as gender identities and divisions of labor that correspond to gender, with men, perhaps due to their greater size, assuming duties outside the home, and women, perhaps due to their ability to bear children, performing domestic roles. Concurrent with these realities, men and women depend on each other for heterosexual intimacy and reproduction, creating a unique situation in which the societal dominant group (men) depends on the subordinate group (women). Such a situation provides women with dyadic power (Guttentag and Secord 1983), and creates ambivalent ideologies toward each gender, from each gender.

These widespread and prevalent, albeit not universal, conditions motivate members of both groups to adopt interrelated and oppositely-valenced gender attitudes that reflect each group’s situation. For example, in a patriarchy, men’s institutional control might elicit women’s resentment of men’s dominance (hostility toward men) concurrent with respect and admiration for their higher status (benevolence toward men). Likewise, women’s dyadic power might produce hostility toward women who challenge the gender-stratified status quo and benevolent attitudes toward women who comply. Although ideologies toward each gender may have originated in the reactions of the other gender (e.g., attitudes toward men originating in women’s reactions to male dominance), each ideology diffuses across the gender divide. Thus, both men and women recognize all of the ambivalent gender ideologies as coherent and familiar attitude clusters, though they show varying degrees of endorsement of the attitudes (Glick et al. 2000, 2004).

In sum, ambivalent sexist attitudes are rooted in heterosexual close relationships in the context of greater societal gender power relations, and represent men and women’s attitudes toward gender-relations within three areas: gender hierarchy and power, gender differentiation, and heterosexuality. Below we review these attitudes in greater detail.

Ambivalent Sexism Toward Women

The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (Glick and Fiske 1996, 1997) (ASI) consists of hostile sexism (HS) and benevolent sexism (BS) toward women. Gender power imbalance, together with gender differentiation along perceived traits and division of labor, and with partners’ genuine desire for heterosexual intimacy, breeds ambivalent and highly correlated gender ideologies relating to each of the three elements.

Dominant groups, in the interest of protecting their power and maintaining their upper hand, are motivated to uphold the status quo and endorse system-justifying ideologies (Jost and Banaji 1994). These interests breed hostile sexist attitudes toward women entailing dominative paternalism, which asserts and justifies male dominance by endorsing gender stereotypes and their attendant gender roles. These gender stereotypes assign agentic and competent attributes to men, and characterize women as weak, consequently viewing men as better fit and women as not fully competent to wield power or take structural control. At the same time, these perceived female weaknesses stir up protective paternalism, benevolently sexist sentiments that express women’s need to be protected because of these weaknesses and cherished because of their role as romantic partners. By depicting women as deserving of male protection, benevolent sexism is positive in tone, and by promising rewards of idealization by the dominant group, it is alluring to its targets. Cross-cultural data indicate the prevalence of these protective sentiments toward women within patriarchal systems (Glick et al. 2000, 2004; Guttentag and Secord 1983).

In differentiating men and women along stereotypically perceived traits and social roles, competitive gender differentiation depicts only men as possessing traits and ability (e.g. ambitious, agentic) suited for powerful and high status positions and women as the weaker sex. Meanwhile, complementary gender differentiation characterizes women as having favorable traits that complement those of men: Women’s caring nature compensates for men’s lack thereof. Hence, these depictions of women not only complement, but also compliment! Furthermore, gender-based division of labor corresponds to these gender-stereotypical traits: men’s perceived ambition naturally lends itself to dominating institutions, while women’s perceived sensitivity lends itself well-suited for caretaking roles. But, both types of differentiation legitimate and reinforce the gender hierarchy: the hostile form (competitive) presents a social justification for male structural power by disputing women’s ability to assume powerful male-dominated positions. The benevolent form (complementary) further protects the status quo by merely highlighting the silver lining; it emphasizes women’s positive traits (e.g. caring) that happen to align with restrictive and subordinate roles (e.g. homemaker).

Heterosexual romantic relationships represent another double-edged sword. On the darker side, men’s reliance on women as romantic partners, mothers to their offspring, and sexual gatekeepers, allows women to gain dyadic power, creating a vulnerability for men that they may channel into heterosexual hostility, viewing women as using sexual desirability and attractiveness to control men, fueling hostility and resentment toward women. At the same time, close relationships entail a genuine desire for intimacy from both partners. Men’s desire for heterosexual intimacy promotes benevolent attitudes that romanticize their partner, revere them as the mother of their offspring, and endorse the protection and idealization of women for the dyadic roles women play. These benevolent attitudes may motivate sincere behaviors (e.g., helping, self-disclosure) that build intimacy. But in a patriarchal system, this interdependence creates a unique setting in which the dominant partner depends on the subordinate.

Much like a well-coordinated carrot and stick reinforcement system, hostile and benevolent sexism toward women work in tandem to maintain and legitimate the existing patriarchy. Hostile attitudes distinguish men’s fit and women’s lack-of-fit to high-status positions; benevolent attitudes placate and compensate women by spotlighting the non-threatening roles they should play instead. Hostile sexism essentially comprises dominative and competitive attitudes and takes an adversarial stance toward gender relations, targeting those women who potentially challenge the male dominance (Glick et al. 1997; Sibley and Wilson 2004), especially in the form of sexual harassment (Berdahl 2007). Benevolent sexism offers appeasement through rationalization and flattering depictions of women (Glick et al. 1997; Sibley and Wilson 2004).

Ambivalent Sexism Toward Men

The same three conditions—patriarchy, gender differentiation, and heterosexuality—that produce ambivalence toward women likewise produce hostility toward men (HM) and benevolence toward men (BM), ambivalent attitudes measured in the Ambivalence toward Men Inventory (Glick and Fiske 1999) (AMI). HM entails resentment of paternalism, men’s higher status in society, and male aggressiveness. Yet, BM endorses men’s suitability for exercising power and men’s traditional role as protectors and providers (of and “for” women), and seeks heterosexual intimacy.

As in any hierarchy, one group’s dominance and social structural control may create frustration and resentment among subordinate group members toward the dominant group. Within a system of gender stratification, women may express hostility in the form of resentment of paternalism, which views men less positively than women. However, these depictions, when balanced with the reality of men’s power and higher status, must take on the form of negative but powerful traits associated with status (e.g. dominant, cocky). In other words, depictions of men express negative evaluations, but acknowledge their status. In this vein, though negative, stereotypes of men help to reinforce the status quo by characterizing men as designed for dominance (Glick et al. 2004). Male societal dominance also generates a form of benevolence labeled maternalism, including notions that men have weaknesses (e.g. they cannot cook or clean) that require women to protect and nurture them. From this perspective, women are competent and powerful, in a limited domain. Disguised as female expertise and domestic know-how, maternalism allows women to carve out a safe niche and provides them with a source of group esteem without directly challenging the reality of male dominance.

As a subordinated group, women may differentiate themselves from the dominant group in a hostile manner that characterizes men negatively (compensatory gender differentiation). These attitudes allow women to compensate for their lower status by criticizing men, but in a way that does not challenge male authority. These include characterizing men as arrogant and hyper-competitive, traits that are negatively valenced but do not challenge the powerholder’s authority (as would an attribution of incompetence), or belittling beliefs confined to the domestic sphere where women are ceded a limited form of competence and authority (e.g., the notions that men are babies when sick or cannot take care of themselves at home). Yet, in acknowledgment and admiration of men’s higher status, women may simultaneously hold benevolent attitudes toward men that justify their traditional protector/provider role. This complementary gender differentiation promotes the status quo by reinforcing men’s competence (and women’s implied incompetence) in masculine domains. Indeed, consistent and stable group status differentials may encourage the lower-status group to adopt system-justifying beliefs that they are less competent (Jost and Banaji 1994).

Women’s interdependence with men combined with greater male power and sexual aggression leads to heterosexual hostility toward men, viewing them as sexual predators because of the potential for men to abuse their power. At the same time women’s traditional reliance on men to serve the protector and provider role in the context of heterosexual romantic relationships fosters subjectively benevolent attitudes toward men, such as that women are incomplete without men, reflecting a genuine desire for heterosexual intimacy. Just as ambivalent sexism toward women represents the dominant group’s attempts to maintain control while recognizing men’s reliance on the “weaker” gender (as wives and mothers), ambivalent sexism toward men represent the subordinate group’s resentment of men’s power while acknowledging women’s traditional reliance on men (as protectors and providers). Hostility comprises resistance and resentment of the domineering high status group, characterizing men negatively, while benevolence concerns acknowledgement and respect for their status, even while disparaging men in areas safe to criticize.

The Curious Case of Benevolent Sexism

AST’s most influential insight has been distinguishing benevolent sexism not only from its hostile counterpart, but from contemporary sexism (see Swim et al. 1995; Tougas et al. 1995). Benevolent sexism is not a new form of prejudice because its origin differs fundamentally from other forms of ambivalent prejudice. Rather than a politically correct attitude disguised as egalitarian, benevolent sexism is deeply rooted in long-existing male-female relations. Numerous studies support its association to other traditional ideologies (e.g., Burn and Busso 2005; Christopher and Mull 2006; Feather 2004; Glick et al. 2004).

Rooted in long-standing heterosexual interdependence between women and men, benevolent sexism has an ancient history and represents a gender traditional attitude. The data underscore this point. For example, benevolent sexism uniquely relates to men’s favorable impressions of a woman breastfeeding a baby, exemplifying motherhood (Forbes et al. 2003). The most recent data indicate that benevolent sexism (at least toward women) is distinct even from traditional gender roles in the public domain (employee and educational settings) (Swim et al., under review), reflecting traditional roles within the domestic sphere (Eastwick et al. 2006; Lee et al. 2010; Travaglia et al. 2009). In short, benevolent gender attitudes are intrinsically tied to age-old gender roles and did not recently form to superficially flatter and reward non-threatening women.

The idea that BS and HS compose co-existing polarized attitudes begs the question: How does a perceiver maintain attitudinal consistency in the face of apparent ambivalence? As with other stable and paternalistic forms of group stratification (e.g., colonialism), the high-status group provides the subordinate group affection and protection contingent on their compliance (Jackman 1994). With gender disparity, BS induces compliance by its harmonious tenor through rewarding women when they conform to their prescribed domestic roles. However, hostile attitudes are reserved for women who challenge their prescribed roles and threaten male dominance. When a target individual fits into a particular subtype (e.g., homemaker, feminist), she elicits the corresponding attitudes (e.g., benevolent, hostility, respectively). Consequently, hostile sexism toward women predicts negatively valenced stereotypes of women, while benevolence toward women predicts positively valenced stereotypes of women; the same pattern holds for ambivalence toward men and stereotypes of men (Glick et al. 2004). Yet, despite their association with positive depictions of each gender, benevolent sexism often exerts more pernicious effects on gender equality, compared with hostility. Because BS contains positive images and rewards certain female subtypes, people consequently evaluate perpetrators of benevolent sexism much more positively than hostile sexists (Kilianski and Rudman 1998) and often do not classify benevolently sexist attitudes as “sexism” or prejudice (Barreto and Ellemers 2005). Longitudinal research reveals that acceptance of benevolent sexism leads women to endorsing hostile sexism (Sibley et al. 2007).

Several papers in this special issue further highlight the insidious effects of BS. Kilianski and Rudman (1998) had found that female undergraduate perceivers did not believe the same person could endorse benevolently and hostilely sexist attitudes toward women. While Bohner et al. (2010) show that this past finding may have been an artifact of the experimental design, they confirm that women generally approve of a man described as a benevolent (but not also hostile) sexist.

Additionally, Sibley and Perry (2010) demonstrate that benevolent sexism has a direct hierarchy-attenuating effect for female perceivers in that it positively predicted voting for policies promoting gender equality. At the same time, however, they find that women’s endorsement of BS simultaneously has an indirect and opposite, hierarchy-enhancing effect by encouraging greater endorsement of HS. Further, exposure to benevolent sexism increases women’s autobiographical memories of incompetence (Dumont et al. 2010), actively undermining the self-efficacy that might lead women to achieve greater equality. And Bosson et al. (2010) show that while women directly experience negative effects when treated in a benevolently sexist manner, people underestimate the initial impact of benevolent sexism and the time required to recover from exposure to it. Furthermore, benevolent sexism targets face double jeopardy—patronizing paternalism from the perpetrators and negative evaluations from third party bystanders (Good and Rudman 2010).

Taken together, these effects are ironic, given that women may adopt benevolent sexism as a self-protective measure to buffer against structural disadvantage. For example, in nations where men’s HS scores are extremely high, women’s BS is just as high as, if not higher than, men’s (Glick et al. 2000, 2004). On the individual level, women are more likely to endorse BS in response to feedback that men hold negative attitudes toward women (Fischer 2006). But feedback about men’s positive attitudes or no feedback did not change these undergraduate American women’s gender attitudes. Benevolent sexism toward women has an especially disarming effect on women high in Right Wing Authoritarianism: In a study with New Zealand undergraduates, women increased their endorsement of hostility toward women over time (Sibley et al. 2007). Thus, not only does BS maintain and justify gender stratification on its own, it also promotes it indirectly.

This Special Issue

The papers in this special issue are the product of various researchers independently branching out in myriad directions in applying the AST to a cornucopia of topics. Although ambivalent sexism grows out of heterosexual close relationships, these researchers demonstrate its wide applicability, their studies covering both the private and public domains, addressing situations of societal hierarchy (e.g., employment) and heterosexual interdependence (e.g., attraction). We are delighted to see its broad theoretical applicability and the range of nations in which the theory is being applied.

These papers also represent a range of methods, spanning quantitative and open-ended analyses of cross-sectional and time-variant data. Likewise, they capture a wide-ranging array of dependent variables, from attraction ratings, to policy attitudes, to memory, and to behavior, the medium of intergroup relations. While some studies depict the underlying construct (e.g., an interviewer expressing protective and paternal attitudes toward female applicants), others use the AST subscales (BS, HS, BM, HM). Either way of applying the theory supplies insights. The constructed scenarios are real-world encounters women may face, and the scales also express an applicable theory, efficiently demonstrating discriminant validity of each form of ambivalent sexism.

In the last fifteen years, research on the AST has taken off, and as a result, we now know much more about ambivalent sexism. The research programs follow a trajectory necessary to the development of any psychological concept, answering the Is, When, and How research questions (Zanna and Fazio 1982). In the Is stage of research, investigators ask, Does X, the concept of interest, affect or relate to Y? For example, does ambivalent sexism constitute an internally consistent variable that meaningfully relates to relevant variables, such as political ideology, as predicted? The When research stream seeks to identify the boundary conditions of initial effects, discovering important moderators. For example, what short-term contexts or target characteristics determine when ambivalent sexism is expressed? The How research stream concerns process; researchers explore what mediates the effect. For example, what processes within perceivers and within targets co-occur with ambivalent sexism’s effects?

Ambivalent sexism research has followed its own developmental trajectory, as a variant on the Zanna-Fazio themes. This special issue reflects articles relevant to three research streams: conceptually relevant correlates (establishing what AS is), causality in short-term context (exploring when AS occurs), and mediated causal effects on people’s self processes (exploring how AS influences internal states).

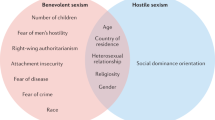

In the first stream, researchers aim to identify and investigate converging correlates. This research line asks, Which other long-term variables correlate with ambivalent sexism, and how? Some papers in this issue focus on the correlation question: How do ambivalent gender ideologies relate to other simultaneous ideologies (e.g., long-term policy preferences) or cultural values (e.g., religiosity)?

The second stream concerns causality in experimental contexts: When does ambivalent sexism have consequences for targets? This work documents its causal impact on targets, paying special attention to context. In particular, certain kinds of targets (e.g., subtypes of women) and situations make these effects more likely to emerge.

The third stream identifies and examines converse causality: it grapples with the unexpected reverse effects of (mostly benevolent) sexism on perceivers, especially women, with mediated processes ranging from affective forecasting to autobiographical memory. These research streams address the three Cs of ambivalent sexism concept development: converging correlates, causality in context, and converse causality, yielding important insights about gender relations. We hope readers will share our enthusiasm about these recent developments, which provide snapshots of the current landscape of ambivalent sexism research.

The first set of papers address the long-term correlations question, investigating ambivalent sexism and its relation to relevant ideologies or cultural values. Napier et al. (2010) explore the relationship of proxy measures of HS and BS used in the World Values survey to explore how endorsement of benevolent and hostile sexism relates to subjective well-being. Using archival data from 32 nations, this study shows that BS is associated with greater life satisfaction (for men as well as women) in relatively egalitarian, but not in more traditional, societies. Napier et al. argue that BS helps resolve the dissonance between the persistence of gender inequality and egalitarian values by celebrating the fulfillment women gain by being homemakers. By contrast, in societies where gender inequality is more entrenched (i.e., more extreme and stable), BS shows no relation to subjective well-being.

Focusing in on a particular cultural contrast to prior work, Taşdemir and Sakalli-Uğurlu (2010) examine the relationship between ambivalent sexism and long-term religiosity in a non-Christian country, Turkey. As it does with Christian religiosity, benevolent sexism, controlling for hostile sexism, significantly correlates with Muslim religiosity, and this occurs for both men and women. However, in contrast to Christian religiosity, which shows no relationship to hostile sexism, Islam’s greater emphasis on traditional gender hierarchy suggests a relationship to hostile sexism for religious men. Indeed, Muslim religiosity does correlate with men’s sexist hostility toward women, consistent with its role in justifying a gender hierarchy favoring men.

In an educational policy domain, within the same cultural context, Sakalli-Uğurlu (2010) shows that ambivalent gender attitudes, academic major, and gender correlate with attitudes toward men and women in gender-atypical majors. Turkish college men’s hostile sexism correlates with negative attitudes toward accepting women in the natural sciences. When themselves natural science majors, the men’s benevolence toward men (perhaps a kind of ingroup loyalty) correlates with negative attitudes toward other men who would choose the feminized, lower-status social science major.

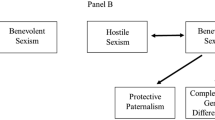

Broadening the policy focus, but still examining converging correlates, Sibley and Perry (2010) propose a process model: BS indirectly (through HS) predicts opposition toward gender-related policies, and simultaneously, directly predicts endorsement of gender equality. This model identifies one avenue through which relatively egalitarian societies manage to maintain their status quo, as these pathways are roughly equal in strength, tending toward equilibrium among New Zealand men and women. The synecdoche—ambivalence (in BS effects) within ambivalence (benevolent and hostile sexism)—demonstrates the complexity of BS. Furthermore, these findings hold promise for their applicability to political behavior: the dependent variable is behavioral intention to vote for gender-equal policies, and the authors were able to replicate the effects in a second time-lagged study.

Thus, BS and HS play distinct roles in long-term belief systems regarding women in general and atypical women in particular, especially justifying gender inequality in political, religious, and academic domains. These papers provide convergent evidence for correlates of ambivalent sexism.

The next set of papers address experimentally established causality, paying attention to the immediate context. Many investigate how ambivalent gender ideologies interact with manipulations of the target’s subtype or gender stereotypicality, determined by what people do and who they are, and therefore, demonstrate the prescriptive power of sexist attitudes; AST predicts differential evaluations of men and women who are more or less gender stereotypical. Some other papers also relate to gender subtypes, but the papers in this cluster all manipulate contextual or subtype features, establishing their causal role showing when sexism affects its targets’ outcomes.

Becker (2010) conducted two studies, one survey and one experimental, to show how salient female subtypes affect women’s sexist ideology endorsement; nontraditional women evoked endorsement of hostile sexism, and traditional women, benevolent sexism. Further, women were more likely to reject hostile statements and endorse benevolent sexism directed at themselves or at housewives, versus nontraditional types of women. These findings suggest that women’s sexism toward women is not general prejudice against their ingroup but reactions to perceived norm deviance or compliance. This paper exemplifies what happens when targets do or do not fulfill the gender roles perceived to be appropriate for their gender.

As noted, ambivalent sexism rewards conforming women and punishes non-conforming women. Focusing on the domain of sexual behavior, Fowers and Fowers (2010) present a study conducted in the US to further show how this hierarchy-reinforcing pattern operates, even for female perceivers. Women’s hostile sexism targets a promiscuous woman, but their benevolence targets a chaste woman. Consistent with its hierarchy-enhancing role, this differentiation (especially the hostility) expands with social dominance orientation. In this sexual domain, a detailed and confident sexual self-schema also increases women’s hostility toward the promiscuous target.

While most studies examine how a sexist’s gender attitudes influence his or her evaluation or treatment of women, Good and Rudman (2010) added another layer by investigating how a third-party observer’s sexism negatively impacts female targets of sexism. They show that when a third party observes a boundary-breaking (applicant for a managerial position) woman, they react most negatively to her when she is treated with BS, implying that perceivers do not believe boundary breakers deserve such benevolent treatment. Further, through sheer positivity toward the interviewer, they viewed the target lower in competence and consequently, did not want to hire her. Using meticulously crafted interview transcripts, Good and Rudman demonstrate that norm-deviant women face double jeopardy—punishment from people they interact with and from mere observers.

Two contributions further explore how benevolent sexism guides reactions to women in the sexual domain, but focus on victim-blame toward women who are subjected to sexual assault. These studies extend and refine prior research showing that perceivers’ endorsement of BS relates to more victim-blaming in cases of acquaintance rape, especially when the victim was “unchaste” (Abrams et al. 2003).

First, Masser et al. (2010) identify a crucial boundary condition (victim stereotypicality) that moderates the relationship of perceivers’ BS to rape victim blame. This study, conducted in Australia, pulls apart victim characteristics that were confounded in prior research: (1) the victim’s violation of gender stereotypes about what it means to be a “good woman” (gender stereotypicality; manipulated by whether the victim was a “good” or “bad” mother to her children) and (2) whether her reactions to being raped fit myths about how rape victims are “supposed” to react (victim stereotypicality; manipulated by whether the victim physically, not just verbally, resisted the assault and was helpful to the police). This study revealed that perceivers’ endorsement of BS was most strongly related to victim blame when the victim was doubly-deviant (violating general gender stereotypes as well as victim stereotypes).

Second, Durán et al. (2010) show how information that the perpetrator of a rape that occurs within an intimate relationship holds benevolently sexist attitudes can lead to increased victim blame. Two studies, one in Spain and the other in England, consistently reveal that benevolently sexist perceivers are more likely to blame the victim when rape is committed by a husband who expresses benevolently sexist beliefs. These studies not only reinforce past research showing that perceivers’ endorsement of BS can foster victim-blame, but show that perpetrator characteristics (not just victim characteristics) moderate these tendencies.

Thus, the second stream addresses a variety of moderator variables, detailing experimental causality in context. Finally, the following third-stream authors examine converse causality. They investigate how ambivalent sexist attitudes boomerang to a variety of self-processes for the perceiver, even female perceivers, ranging from affective forecasting to autobiographical memory. Some papers opted to rely on self-reports, while others experimentally manipulated.

Bosson et al. (2010) compare women’s reports of their affective reactions to ambivalent sexism with affective forecasts from both men and women (who reported no previous experience with being the target of sexism). People (both men and women who have not encountered being a target of sexism) overestimate the affective impact of hostile sexism and underestimate the affective impact of benevolent sexism. The researchers then propose a model in which people’s inaccurate estimates of initial intensity mediate their inaccurate estimates of recovery duration. Thus, these findings suggest that victims of benevolent sexism may not seek or receive the social support they need, due to its widespread underestimated impact.

Going beyond failures to appreciate its impact, Barreto et al. (2010) show women complicit in their own sexist treatment. Women cooperate with benevolent sexism by emphasizing their relational self and de-emphasizing their task self. Thus, women experimentally exposed to BS then self-perceive in ways that confirm the prescriptions of benevolent sexism. Understanding these mediators of BS effects clarifies its processes.

Dumont et al. (2010) show that benevolent sexism again affects women’s self-views. Using a Belgian sample, they show the mediators: benevolent sexism, by generating intrusive thoughts about one’s incompetence, also slows response time, and activates autobiographical memory, all of which interferes with cognitive performance. Hostile sexism does not have these effects, perhaps because it is more overtly aggressive in tone.

Fields et al. (2010) had female participants complete an essay on “what it means to be woman” to generate a rich set of narrative data tapping women’s lived experiences. Their intent was to test the construct validity of the ASI by determining whether women’s spontaneous responses map onto the constructs specified by AST and correlate with responses on the ASI’s close-ended scales. Fields et al. confirm that women’s experiences do map onto AST’s constructs, with participants specifying social pressures related to HS and BS, across all of their subdomains (power, gender roles and stereotypes, and heterosexuality). While responses suggest a narrative of progress in which women are less likely to endorse sexist attitudes as compared to older female relatives, this study (conducted with American undergraduates in the South) reveals significant endorsement of BS, highlighting how BS remains attractive to many women.

Bohner et al. (2010) present three studies with female German participants. They dispute Kilianski and Rudman’s (1998) finding that women fail to perceive that BS and HS are likely to be simultaneously endorsed by individual men, convincingly showing that this finding was probably an artifact of experimental procedure. Nevertheless, Bohner et al. confirm and extend Kilianski and Rudman’s finding that women have positive perceptions of benevolently sexist men. In the current set of studies, women believed that a purely benevolent (but not hostile) sexist was the least typical type of men, but also viewed such a man as the most likeable and romantically attractive type (compared to hostile sexists, ambivalent sexists, and even nonsexists). Contemporary women’s continuing tendency to find men’s benevolent sexism sexy provides a powerful incentive for men to endorse BS, which (as noted above) has a variety of insidious effects.

Lee et al. (2010) present findings from a survey study conducted in the US and in China that investigates the relationship between ambivalent sexism and close relationship ideals, moderated by gender and culture. Finding that 1) benevolent ideologies predict people’s partner ideals, especially in the US, and 2) hostile ideologies predict men’s ideals, the study lends support to the idea that while benevolent sexism entails a romanticized set of attitudes and employs subtle partner control, hostile sexism reflects an overtly power-based control strategy.

This last section’s articles together show converse causality, in the sense that the main targets of ambivalent sexism—that is, female perceivers—respond in ways consistent with the ideology of this belief system. Collectively, all articles in this special issue make a number of important contributions to the study of ambivalent sexism; they 1) establish its convergence with other variables and 2) demonstrate its prescriptive function, including 3) its impact on perceivers’ self-processes. Many of the findings reiterate that people underestimate the impact of BS. Further, a few studies demonstrate that observers’ own sexism interact with a perpetrator’s sexism, and highlight that sexism targets simultaneously encounter multiple forms of sexism, including from those observers with whom they have no interactions. And finally, although HS and BS were originally conceived as how men react to women (and HM and BM as how women react to men), many of these contemporary studies investigate sexism toward women from the perspective of female perceivers, indicating that sexism entails not just intergroup attitudes but intragroup attitudes as well. In so doing, these papers illustrate that each form of sexism means something different for the perceiver depending on group membership. In the case of BS, this ideology may serve both as the dominant group’s (i.e., men’s) way of placating compliant women, but it is the subordinate group’s (i.e., women’s) way of self-protection, compensating for their lower status.

Possible Future Areas of Research

The papers in this special issue have moved us forward in a significant way, sparking new questions that can guide future research. Most of the research on ambivalent sexism to date has focused on effects, forward and reversed, and almost entirely on negative consequences. This work is necessary but not sufficient. As with any other type of prejudice, research ultimately should focus on intervention. To the extent that ambivalent sexism comprises deep-seated ideologies, they pose another challenge for researchers interested in eradicating their consequences. What might lead people to change such fundamental attitudes? One promising avenue of research might rest in social norms. People are social creatures who want to belong (Fiske 2010), sometimes adopting attitudes or exhibiting behaviors they misperceive others as holding or enacting. Correcting such pluralistic ignorance or false consensus beliefs has been successful in changing a variety of social behaviors (Berkowitz 2003). The take-away message from social norms theory is that people care what other people think and use their estimates of others’ beliefs (accurate or not) to shape their own attitudes and behaviors. Interventions in prejudice research demonstrate this well—providing people with information about what outcome is desired may impact people to tune in and assimilate to such an outcome (Sinclair et al. 2005). One application of the social norms intervention approach to sexism has shown promising results, at least for HS (Kilmartin et al. 2008). Another candidate to target in future research might be men’s BS, as both men and women’s perceptions of men’s BS predict their own BS (Sibley et al. 2009).

To be sure, intervention might be especially difficult in the case of BS. As noted, AST introduced the notion that sexist attitudes could be positively valenced, and later researchers demonstrated that BS is often undetected (as prejudice), rewarded (as “nice” and “romantic”), or even likely to stir up negative evaluations of the target who rejects it from disgruntled bystanders. These findings introduce new challenges to socially minded researchers: how to detect and label affectively positive ideologies as sexism, with the aim of effectively counteracting such attitudes? Combating BS requires a new set of strategies given that it constitutes attitudes and behaviors that are not usually viewed as offensive—attempts to catch BS based on measures of offensiveness or valence are rather ineffective (see Barreto and Ellemers 2005; Kilianski and Rudman 1998). One key for making the case that BS is not benign is research that measures tangible and clearly important outcomes, such as Dardenne et al. (2007) investigation illustrating how BS undermines women’s task performance. In addition, research could consider converging evidence, i.e. newer measures (e.g. imaging) that corroborate traditional measures (e.g. behavioral ratings) (Cikara et al., under review).

The extant literature has touched a great deal on sexism toward women and less so on sexism toward men. Men also face sexism, particularly those who work in traditionally female dominated domains (e.g., male nurses, Erikson and Einarsen 2004) or when they are perceived to be too feminine or not masculine enough (Berdahl et al. 1996). This area is important to pursue and likely to reveal dynamics that differ from sexism toward women. For example, the most upsetting form of gender harassment for men was other men’s enforcement of the male gender role; men face sexism more from other men than from women (Waldo et al. 1998). While it is understandable why sexism toward men is less studied—prejudice toward the dominant group is usually less threatening, and in the particular case of male targets, they report little emotional impact (Waldo et al. 1998)—the experiences of male and female targets of sexism differ because of their group’s status in society, as future research could better illuminate.

We hope that this issue will arouse future research in a variety of areas, among others, and create new psychological insights at the intersection between sexism and heterosexual close relationships, enriching both research fields and progressively connecting them ever closer. The papers in this issue represent an important set of stepping stones in this continuing endeavor.

References

Abrams, D., Viki, G. T., Masser, B., & Bohner, G. (2003). Perceptions of stranger and acquaintance rape: The role of benevolent and hostile sexism in victim blame and rape proclivity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 111–125.

Barreto, M., & Ellemers, N. (2005). The burden of benevolent sexism: How it contributes to the maintenance of gender inequalities. European Journal of Social Psychology, 35, 633–642.

Barreto, M., Ellemers, N., Piebinga, L., & Moya, M. (2010). How nice of us and how dumb of me: The effect of exposure to benevolent sexism on women’s task and relational self-descriptions. Sex Roles, this issue.

Becker, J. C. (2010). Why do women endorse hostile and benevolent sexism? The role of salient female subtypes and internalization of sexist contents. Sex Roles, this issue.

Berdahl, J. L. (2007). The sexual harassment of uppity women. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 425–437.

Berdahl, J. L., Magley, V. J., & Waldo, C. R. (1996). The sexual harassment of men: Exploring the concept with the theory and data. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 20, 527–547.

Berkowitz, A. D. (2003). Applications of social norms theory to other health and social justice issues. In H. W. Perkins (Ed.), The social norms approach to preventing school and college age substance abuse: A handbook for educators, counselors, and clinicians (pp. 259–279). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Bohner, G., Ahlborn, K., & Steiner, R. (2010). How sexy are sexist men? Women’s perception of male response profiles in the ambivalent sexism inventory. Sex Roles, this issue.

Bosson, J. K., Pinel, E. C., & Vandello, J. A. (2010). The emotional impact of ambivalent sexism: Forecasts versus real experiences. Sex Roles, this issue.

Burn, S. M., & Busso, J. (2005). Ambivalent sexism, scriptural literalism, and religiosity. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 29, 412–418.

Christopher, A. N., & Mull, M. S. (2006). Conservative ideology and ambivalent sexism. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30, 223–230.

Cikara, M., Eberhardt, J. L., & Fiske, S. T. (under review). From agents to objects: Sexist attitudes and neural responses to sexualized targets.

Dardenne, B., Dumont, M., & Bollier, T. (2007). Insidious dangers of benevolent sexism: Consequences for women’s performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93, 764–779.

Dumont, M., Sarlet, M., & Dardenne, B. (2010). Be too kind to a woman, she’ll feel incompetent: Benevolent sexism shifts self-construal and autobiographical memories toward incompetence. Sex Roles, this issue.

Durán, M., Moya, M., Megías, J. L., & Viki, T. G. (2010). Social perception of rape victims in dating and married relationships: The role of perpetrator’s benevolent sexism. Sex Roles, this issue.

Eastwick, P. W., Eagly, A. H., Glick, P., Johannesen-Schmidt, M., Fiske, S. T., Blum, A., et al. (2006). Is traditional gender ideology associated with sex-typed mate preferences? A test in nine nations. Sex Roles, 54, 603–614.

Erikson, W., & Einarsen, S. (2004). Gender minority as a risk factor of exposure to bullying at work: The case of male assistant nurses. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 13, 473–492.

Feather, N. T. (2004). Value correlates of ambivalent attitudes toward gender relations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 3–12.

Fields, A. M., Swan, S., & Kloos, B. (2010). ‘What it means to be a woman’: Ambivalent sexism in female college students’ experiences and attitudes. Sex Roles, this issue.

Fischer, A. R. (2006). Women’s benevolent sexism as reaction to hostility. Psychology of Women’s Quarterly, 30, 410–416.

Fiske, S. T. (2010). Social beings: Core motives in social psychology (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley.

Forbes, G. B., Adams-Curtis, L. E., Hamm, N. R., & White, K. B. (2003). Perceptions of the woman who breastfeeds: The role of erotophobia, sexism, and attitudinal variables. Sex Roles, 49, 379–388.

Fowers, A. F., & Fowers, B. J. (2010). Social dominance and sexual self-schema as moderators of sexist reactions to female subtypes. Sex Roles, this issue.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1996). The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 491–512.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1997). Hostile and benevolent sexism: Measuring ambivalent sexist attitudes toward women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 119–135.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1999). The ambivalence toward men inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent beliefs about men. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 23, 519–536.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (2001). Ambivalent sexism. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology, vol. 33 (pp. 115–188). Thousand Oaks: Academic.

Glick, P., Diebold, J., Bailey-Werner, B., & Zhu, L. (1997). The two faces of Adam: Ambivalent sexism and polarized attitudes toward women. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 1323–1334.

Glick, P., Fiske, S. T., Mladinic, A., Saiz, J. L., Abrams, D., Masser, B., et al. (2000). Beyond prejudice as simple antipathy: Hostile and benevolent sexism across cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 763–775.

Glick, P., Lameiras, M., Fiske, S. T., Eckes, T., Masser, B., Volpato, C., et al. (2004). Bad but bold: Ambivalent attitudes toward men predict gender inequality in 16 nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 713–728.

Good, J. J., & Rudman, L. A. (2010). When female applicants meet sexist interviewers: The costs of being a target of benevolent sexism. Sex Roles, this issue.

Guttentag, M., & Secord, P. (1983). Too many women? Beverly Hills: Jossey-Bass.

Jackman, M. R. (1994). The velvet glove: Paternalism and conflict in gender, class, and race relations. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Jost, J. T., & Banaji, M. R. (1994). The role of stereotyping in system-justification and the production of false-consciousness. British Journal of Social Psychology, 33, 1–27.

Kilianski, S. E., & Rudman, L. A. (1998). Wanting it both ways: Do women approve of benevolent sexism? Sex Roles, 39, 333–352.

Kilmartin, C., Smith, T., Green, A., Heinzen, H., Kuchler, M., & Kolar, D. (2008). A real time social norms intervention to reduce male sexism. Sex Roles, 59, 264–273.

Lee, T. L., Fiske, S. T., & Glick, P. (2010). Ambivalent sexism in close relationships: (Hostile) power and (benevolent) romance shape relationship ideals. Sex Roles, this issue.

Masser, B., Lee, K., & McKimmie, B. M. (2010). Bad woman, bad victim? Disentangling the effects of victim stereotypicality, gender stereotypicality and benevolent sexism on acquaintance rape victim blame. Sex Roles, this issue.

Napier, J. L., Thorisdottir, H., & Jost, J. T. (2010). The joy of sexism? A multinational investigation of hostile and benevolent justifications for gender inequality and their relations to subjective well-being. Sex Roles, this issue.

Sakalli-Uğurlu, N. (2010). Ambivalent sexism, gender, and major as predictors of Turkish college students’ attitudes toward women and men’s atypical educational choices. Sex Roles, this issue.

Sibley, C. G., & Perry, R. (2010). An opposing process model of benevolent sexism. Sex Roles, this issue.

Sibley, C. G., & Wilson, M. S. (2004). Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexist attitudes toward positive and negative sexual female subtypes. Sex Roles, 51, 687–696.

Sibley, C. G., Overall, N. C., & Duckitt, J. (2007). When women become more hostilely sexist toward their gender: The system-justifying effect of benevolent sexism. Sex Roles, 57, 743–754.

Sibley, C. G., Overall, N. C., Duckitt, J., Perry, R., Milfont, T. L., Khan, S. S., et al. (2009). Your sexism predicts my sexism: Perceptions of men’s (but not women’s) sexism affects one’s own sexism over time. Sex Roles, 60, 682–693.

Sinclair, S., Lowery, B. S., Hardin, C. D., & Colangelo, A. (2005). Social tuning of automatic racial attitudes: The role of affiliative motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 583–592.

Swim, J. K., Aikin, K. J., Hall, W. S., & Hunter, B. A. (1995). Sexism and racism: Old-fashioned and modern prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 199–214.

Swim, J. K., Becker, J. C., & DeCoster, J. (under review). Core dimensions underlying contemporary measures of sexist beliefs.

Taşdemir, N., & Sakalli-Uğurlu, N. (2010). The relationships between ambivalent sexism and religiosity among Turkish university students. Sex Roles, this issue.

Tougas, F., Brown, R., Beaton, A. M., & Joly, S. (1995). Neosexism: Plus ca change, plus c’est pareil. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21, 842–849.

Travaglia, L. K., Overall, N. C., & Sibley, C. G. (2009). Benevolent and hostile sexism and preferences for romantic partners. Personality and Individual Differences, 47, 599–604.

Waldo, C. R., Berdahl, J. L., & Fitzgerald, L. F. (1998). Are men sexually harassed? If so, by whom? Law and Human Behavior, 22, 59–79.

Zanna, M. P., & Fazio, R. H. (1982). Commentary. The attitude-behavior relation: Moving toward a third generation of research. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Consistency in social behavior: The Ontario symposium on personality and social psychology (pp. 282–303). Erlbaum: Mahwah.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, T.L., Fiske, S.T. & Glick, P. Next Gen Ambivalent Sexism: Converging Correlates, Causality in Context, and Converse Causality, an Introduction to the Special Issue. Sex Roles 62, 395–404 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9747-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9747-9