Abstract

This study examined 104 undergraduate college students (mean age = 19) from the Western United States regarding gender differences in their experiences of gender prejudice. Women (N = 81) and men (N = 22) responded to an online diary for 14 days, resulting in 1008 descriptions of events. Women reported significantly higher levels of negative affect than men during the experiences. Qualitative content analysis was used to analyze event descriptions and three main themes emerged including target of the event, perpetrator and setting. Significant differences were found for target and perpetrator based upon the gender of the participant. There were also significant differences in the distribution of the type of event (gender role stereotypes, sexual objectification or demeaning events) based on the setting and target.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It has been well documented that college students within the United States experience various events resulting from gender prejudice, which Eckes and Trautner (2000) define as “the attitude that a group deserves lower social status based on gender related categorization” (pp. 442) (Reilly et al. 1986; Dietz-Uhler and Murrell 1992; Shepela and Levesque 1998; Swim et al. 2001, Hyers 2007). Events based on gender prejudice can include sexual harassment, job or academic discrimination, expectations to conform to gender role stereotypes, harassment and hearing demeaning comments, as each of these forms are rooted in the basic mistreatment of a group (or individual) based on gender. When studying such experiences, many prior studies have used the term “sexism,” which Lott (1995) defines as “the oppression or inhibition of women through a vast network of everyday practices, attitudes, assumptions, behaviors and institutional rules” (pp.113). The term “gender prejudice” is utilized in this study to be more inclusive of the experiences of men, but not to imply that men face sexism in the same way women do. Previous research on sexism has examined women’s reported experiences ranging from interpersonal discrimination, put downs, offensive humor, personal distancing by men, insults and harassment to intimidation, sexual coercion, abuse, and rape (Lott 1995). Much of this research has taken one of two routes; either 1) exploring one specific type of prejudice, such as sexual harassment, or 2) including all different types of experiences under the general term of sexism, but without an examination of how these types may differ. The current study included three different types of gender prejudice including sexual objectification, demeaning or derogatory experiences and experiences involving gender role stereotypes, and examined potential differences among these types of events.

There has been considerable research demonstrating that experiences of gender prejudice often have deleterious effects on the victims, affecting their physical health (Dansky and Kilpatrick 1997; van Roosmalen and McDaniel 1998), influencing psychological well being (Cleary et al. 1994), and impacting academic achievement (Lee et al. 1996; Barickman et al. 1992). Much of the information psychologists and educators have amassed about gender prejudice results from retrospective survey research or laboratory based experiments with fewer studies employing diary techniques. Most research in this area has only included women, so less information exists describing the gender prejudice experiences of men. In addition, little is known about how events may differ based on the type of gender prejudice experienced. For instance, experiences in which a person has been sexually objectified may differ significantly from events during which a person has been subjected to demeaning comments based on their gender. It is important to explore how gender of the victim and the type of prejudice experienced may relate to other factors including characteristics of the perpetrators and targets and the settings in which such events occur.

The purpose of this study was to explore the descriptions of gender prejudice experienced by female and male college students within the United States. An online daily diary was utilized with questions answered in an open-ended format. This method was chosen to allow the students to describe their experiences in their own words, providing information that they felt was relevant. The goal was to explore potential similarities and differences between women and men in their experiences of gender prejudice, as well as to examine the influence of the type of event. While this research focused on the experiences of students within the United States, the findings are applicable to researchers around the world. For example, they may provide insight into ways that gender prejudice may function in countries with gender role ideologies similar to those found within the United States. The findings might also serve as a reminder of the importance of examining the context of a situation in which any form of prejudice takes place, including examining characteristics of the perpetrators and targets as well as the settings in which such events occur.

Gender Similarities and Differences in Experiencing Prejudice

There is considerable evidence to indicate that experiences of different forms of gender prejudice are common for college women within the United States, with studies suggesting that half of all women will experience some form of major sexual harassment during their college years (Cortina et al. 1998) and that over five million female college students have experienced some type of gender harassment (Paludi and Barickman 1991). Most research has found that women experience sexual harassment and gender prejudice at far greater rates than men (Popovich et al. 1986; Carr et al. 2000) although some studies have demonstrated that women and men experience sexual harassment at similar frequencies (Mazer and Percival 1989). In a recent study of over 1,000 adult employees, 26% of the women and 22% of the men reported having experienced sexual harassment in the workplace (Krieger et al. 2006).

Research has demonstrated that men experience gender prejudice at higher levels than previously assumed (some have assumed that men do not experience such events at all), but there are mixed results regarding gender differences. For example, one study found that out of 525 undergraduate students surveyed, 40% of the women and 28.7% of the men experienced sexual harassment by a professor or instructor (Kalof et al. 2001). While this difference regarding authority figures was significant, there were no gender differences in the students’ experiences of unwanted sexual attention in general. Similarly, Fineran (2002) found that both male and female adolescents experienced sexual harassment at part-time jobs. A significantly greater percentage of the girls reported such experiences, however (63% girls, 37% boys), and girls indicated feeling more upset and threatened by the harassment than did the boys. As most of this research has focused on sexual harassment, other types of gender prejudice have not been explored as thoroughly. This study sought to provide more information about the frequency with which both men and women experience different types of gender prejudice as well as the distress levels they experience during the event. Additionally, it examined whether there are gender differences regarding other characteristics of these events.

Type of Event

One goal of this research was to determine whether the type of event impacted the student’s experiences. This study examined the following three types of gender prejudice; 1) traditional gender role stereotypes, 2) sexual-objectification, and 3) demeaning or derogatory comments and behaviors. These types were derived from both theory and the responses of women and men in other studies of gender prejudice (Kaiser and Miller 2004; Swim et al. 1998; Swim et al. 2001).

Traditional gender role stereotypes have been defined as “culturally shared beliefs about the personal attributes of women and men” (Eckes and Trautner 2000, pp. 442). These stereotypes include beliefs about a group member’s personality traits, as well as behaviors that are deemed appropriate for members of that group (Eckes and Trautner 2000; Fiske and Stevens 1993). Pressure to conform to these expectations can cause distress for women and men. Gender prejudice events based on traditional gender role stereotypes could include being admonished to behave in a “feminine” or “masculine” way, being informed that people believe certain jobs or roles are only suitable for men or women, or hearing comments suggesting that individuals or groups possess lower abilities in some area based on their sex.

The second type of events involved sexual objectification, during which a person is treated as a body that exists for the pleasure of others (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997). Sexual objectification can be experienced through interpersonal and social encounters of sexual harassment that might include events such as being catcalled, hearing unwanted sexual comments or being “checked out.” People may also experience feelings of objectification when they interact with media (television, music videos, magazines, Internet) which treats a person as a sex object. For example, research has found that women who read beauty magazines are more likely to be ashamed of their bodies and to internalize ideals of thinness than women who do not (Morry and Staska 2001). Further, a meta-analysis of women’s experiences of viewing idealized female images in the media found that in 84% of the studies, such images increased women’s experiences of body shame (Groesz et al. 2002). While most of the research suggests that the media most often portrays sexually objectifying images of women, there seems to be a growing trend of media portrayals of men as sexual objects as well. A recent analysis of Men’s Health Magazine demonstrated that the “new meaning” of masculinity included more focus on physical appearance, and the need to have a well-toned body (Alexander 2003). Another study demonstrated the how the ideal male body image became increasingly unrealistic throughout the 20th century, as demonstrated by toy action figures. Pope et al. (1999) found that action figures of today are much more muscular than their predecessors, often to the point that they surpass the limits of human attainment. Aubrey (2007) found that for college women and men, viewing sexually objectifying media was positively associated with self-objectification, body shame and appearance anxiety.

The third type of events studied included incidents involving demeaning and derogatory comments and behaviors. This can consist of hearing sexist jokes, receiving demeaning or derogatory labels or being excluded from conversations by members of the other sex (Kaiser and Miller 2004; Swim et al. 2001). Women may experience such events based on people’s belief that “feminine” traits are seen as inferior to “masculine” traits (Fiske and Stevens 1993). Men may hear demeaning comments if they behave in ways that are viewed as “feminine,” or they may be subject to derogatory experiences based on stereotypes about men. O’Neil (1981) has argued that men fear femininity as a result of unrealistic messages regarding masculinity. While demeaning comments may reflect traditional stereotypes or sexual objectification, they are more negative and directly degrading to the target (Swim et al. 2001).

Current Study

The previous research exploring gender prejudice has led to some mixed results about women’s and men’s experiences. This study sheds important light on what both male and female college students are facing on a daily basis and how their experiences may be similar and in what ways they differ. This study examined three different types of gender prejudice to better understand how these types might differ in terms of the setting in which they are experienced as well as who experiences them. It is essential that we understand the circumstances under which gender prejudice events take place in one’s daily life, in order to fully comprehend people’s potential reactions to these experiences and the impact such events can have.

The current study is unique among other daily diary studies (see Hyers 2007; Kaiser and Miller 2004; Swim et al. 2001) because it did not require the participants to label the events as gender prejudice. Research demonstrates that many people do not label negative events as gender prejudice, even when they experience situations that others have identified as prejudice (Magely et al. 1999; Vorauer and Kumhyr 2001). Whether or not women label a particular experience as sexism, however, they suffer from similar negative psychological, work, and health consequences (Magely et al. 1999), suggesting that labeling the event may be less important than the actual event itself. The participants in this study responded to a checklist of possible gender stereotype events (see Appendix), then answered open ended questions to provide more detail about the experience. The students were also asked to rate their emotional experience during the event, in order to asses the participants’ affect during the situation.

The purpose of the study was to explore college students’ own descriptions of their experiences of gender prejudice. A number of important themes were identified by the participants and explored further. These themes included: 1) target of the event 2) perpetrator and 3) setting. The study also demonstrated how each of these themes is impacted by a) gender of the participant and b) type of event.

Target of Event

Participants were instructed to endorse items on the checklist that they either experienced personally or that happened to them as a member of their gender group. Personal/group discrimination discrepancy theory suggests that people will more likely identify events that happen to their group as a whole (women as a group or men as a group) than to themselves as individuals (Crosby 1984; Taylor et al. 1994). Other research suggests that people are most likely to remember and report experiences that cause greater distress, while behavior that is less severe and transitory is more likely to be ignored (Fitzgerald and Swan 1995). If individuals experience greater distress during events in which they are directly targeted, it would seem plausible that participants would report these experiences as well.

-

Hypothesis 1a:

Women and men will report experiencing gender prejudice events in which they are targeted as an individual as well as events in which they are targeted as a member of their gender group.

It is likely that the frequencies of the different types of events will vary based on who is being targeted (an individual, women as a group or men as a group). However, as there is very little research examining different types of prejudice in the same study, it is difficult to make specific predictions.

-

Hypothesis 1b:

The distribution of the types of events will vary based on who is targeted by the event.

Perpetrator of Event

Men are most often cited as the perpetrators of gender prejudice against women. This finding has been demonstrated in many areas regarding specific types of gender prejudice, such as sexual harassment (Gruber 1998) and applies to gender prejudice in general. A study examining men from around the world found that they scored higher than women on levels of endorsement of hostile sexism, defined as feelings of hostility toward women (Glick et al. 2000). Research has demonstrated that both male and female college students are more likely to identify an action as being prejudiced when it is perpetrated by males than by females; in fact one study found that participants were eight times as likely to label an event as sexist when men were the perpetrators (Baron et al. 1991).

The theory of in group/out group behavior might predict who people perceive to be the perpetrators of prejudice. This theory suggests that under circumstances in which group membership (e.g. gender) is salient, people will make inferences about a person’s behavior based on whether they are a member of the in group or out group (Krueger and Rothbart 1988). In particular, the theory asserts that individuals hold the assumption that members of their own group would be less likely to discriminate against them than would members of other groups. One study found that when college students were asked to predict the perpetrators of vignettes where women or men had been derogated, 88% said the perpetrator was likely male when the victim was a woman (Baron et al. 1991). When the victim was male, 93% of the students predicted that the perpetrator was female. This study suggests that male participants will report that women are most often the perpetrators of prejudice. However, there are mixed findings regarding who is perceived as most likely to be the perpetrator of men’s gender prejudice experiences. O’Neil’s (1981; see also O’Neil et al. 1995 for an extensive review) research on masculine gender role conflict suggests that men often reinforce gender role stereotypes in each other through teasing or bullying. Based on this area of study, male participants will likely cite other men as perpetrators as well. These findings suggest that men and women will report experiencing gender prejudice from perpetrators of different genders. Based on previous literature, two predictions can be made:

-

Hypothesis 2a:

Women will report more male perpetrators than men will and men will report more female perpetrators than women will.

-

Hypothesis 2b:

Men will report more same-gender discrimination (events where men are the perpetrators) than women will report same-gender discrimination (events where women are the perpetrators).

The relationship between the target and the perpetrator might also differ for women and men. Women may be more likely to label negative events committed by a high status perpetrator as discrimination than are men (Rodin et al. 1990). While college students will likely experience gender prejudice from people in positions of authority (e.g. teachers, bosses) it is likely they will report experiences committed by peers as well. These peers may be someone the victim knows (a friend, a classmate, a coworker) or a stranger. Research examining traditional masculinity and how it is reinforced suggests that men will be more likely than women to experience gender prejudice perpetrated by their friends (Runtz and O’Donnell 2003). This research suggests that the relationship between the target and perpetrator will differ based on the participant’s gender. Three specific predictions can be made:

-

Hypothesis 3a:

Women will report a higher percentage of events perpetrated by authority figures than will men.

-

Hypothesis 3b:

Women will report a higher percentage of events perpetrated by opposite gender strangers than will men.

-

Hypothesis 3c:

Men will report a higher percentage of events perpetrated by friends than will women.

Further, it is likely that the gender of the perpetrator as well as the relationship between the target and the perpetrator will be related to the type of gender prejudice committed. Although men’s experiences with sexual harassment and other forms of sexual objectification appear to be increasing, women continue to experience more sexual-objectification than do men (Swim et al. 2001). Previous research has found that men are more likely to perpetrate sexual harassment than are women (Gruber 1998).

-

Hypothesis 4a:

Sexual objectification events will be more often perpetrated by men than by women.

-

Hypothesis 4b:

The distribution of the types of events will differ based on whether the perpetrator is a friend, partner, or acquaintance.

Setting

Gender prejudice can take place in any area of a person’s life. This study explored the settings in which college students indicated that they experienced these events. As little research has examined the setting of gender prejudice events, specific predictions cannot be made. This study described the settings in which men and women experienced gender prejudice and assessed whether the settings differed for women and men and if different types of gender prejudice were more likely depending on the setting.

Summary of Hypotheses

In this study, male and female undergraduate college students completed an online daily diary in which they described their experiences with three different types of gender prejudice. The study examined whether men and women experience these types of events with the same frequency and explored potential gender differences in the affect experienced during these events. Based on previous literature, this study predicted that both women and men would experience all three types of events, and that they would be targeted as individuals and as members of their gender group (Hypothesis 1a) but that the type of event experienced would differ based on the target (Hypothesis 1b). It was also predicted that, given the previous research regarding gender prejudice, both women and men would report experiencing gender prejudice committed by opposite gender perpetrators (Hypothesis 2a), but that men would report greater amounts of same-gender discrimination than would women (Hypothesis 2b). The third set of hypotheses involve the relationship between the target and the perpetrator and gender, predicting that women would report more experiences committed by persons in authority (Hypothesis 3a) and by opposite gender strangers (Hypothesis 3b), while men would be more likely to report friends as perpetrators (Hypothesis 3c). It was expected that the type of prejudice perpetrated would depend on the gender of the perpetrator as well as the relationship between the perpetrator and target (Hypothesis 4a and 4b). Finally, it is likely that the setting in which the event takes place may vary depending on the gender of the participant and the type of event; however no specific hypotheses were made.

Method

Participants

Data from this study were drawn from a larger study examining gender prejudice in the lives of college students (see also Brinkman and Rickard 2009). One hundred and ten participants from a large Western United States university participated in the study. The students were recruited from their Introductory Psychology class and were given credit for participating. For seven participants the number of experiences reported on the daily diaries was more than three standard deviations above the mean. These participants were excluded from further analysis, leaving an N = 103. The final sample was comprised of twenty-two men and eighty-one women, with a mean age of nineteen. Most of the students reported being white non-Hispanic (N = 85), while others self-identified as Native American (N = 4), Asian American (N = 3), Hispanic/Latino/a (N = 2), African American (N = 1), multiethnic (N = 4), or other (N = 4). Many participants reported being heterosexual (N = 91) and some identified as being a gay male (N = 1), or bisexual (N = 1). Most were either first year students (N = 64) or sophomores (N = 26), with some Juniors (N = 8), Seniors (N = 3) and Graduate students (N = 2).

Procedure

Participants met in a designated place and time in medium sized groups. They were given information about the study, and were informed that their answers would not be anonymous, but all information would remain confidential. The participants were given information about the website for the online diary and directions on how to log on. They were instructed to fill out the two-page diary for 14 days. The participants were informed that they would not receive research credit until they submitted the fourteenth day of the web diary. After each participant completed the fourteenth day of the online diary, they were given credit for participating and received a debriefing form.

Measure

The daily diary was created by the researcher and consisted of two parts: a checklist and a set of open-ended questions. The checklist included 18 events; six each of the three types of events 1) traditional gender role stereotypes, 2) sexual objectification, and 3) demeaning/exclusionary comments or behaviors. The checklist was created based on items listed by participants in studies of experienced sexism (Kaiser and Miller 2004; Swim et al. 2001). The checklist was first administered to a group of graduate psychology students; revisions were made based upon their comments in order to make the items more clear and easy to understand (see Appendix for checklist). The diary, including the revised checklist, was then piloted on a group of undergraduate psychology students and further revised. The checklist included items such as “Experienced unwanted sexual behaviors (pinched, slapped, touched in a sexual way),” “Heard comments that members of your gender possess lower levels of ability compared to members of the opposite sex,” “Called a demeaning or degrading label such as slut, bitch, player, etc.”

Participants were first instructed to indicate how many times they experienced each event that day, and then asked to select the event that was most distressing to them and to answer questions based on that event. One of the questions was: “Describe the situation.” If the participant did not experience any of the events, they were instructed to answer the questions regarding a stressful experience they did have that day.

The participant also rated their emotional reaction to the event using the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) (Watson et al. 1988). The PANAS consists of emotion words (this study included 10 positive and 9 negative). The negative words included examples such as distressed, upset, jittery and the positive words included such words as inspired, enthusiastic, and proud. The participant was instructed to indicate the extent to which they felt each emotion during the event using a 5-point Likert scale with 1 = not at all to 5 = extremely. The alpha coefficient reliabilities of the PANAS range from .84 to .90 (Watson et al. 1988), depending on the “period of time” instructions (how do you feel right now, in the last week, month, year, etc.). Cronbach’s alpha for this sample was found to be .85.

Analysis of Responses to Open-ended Question

Entries in which the participants described a stressful event that did not involve gender prejudice (N = 288) were not included in the subsequent analyses; a total of 1008 events were included in the analyses. The principal researcher utilized a process of open coding similar to constant comparative analysis (Glaser and Strauss 1967) to develop themes based on the participant’s responses. A number of themes emerged from this process and categories were developed for each theme, based on the participants’ data. The participants were asked to indicate which event in the checklist they were describing and the open ended responses were coded for the type of event, in order to verify what the participants had indicated. Four additional themes were coded including target, perpetrator, perpetrator gender and setting (see Appendix B for full list of themes and their categories). Four research assistants were trained to code responses based on these categories, with two assistants coding each set of data. Coding continued until at least a 92% inter-rater reliability was attained for each data set. Any discrepancies at this point were then coded by the principal investigator. The question was open ended; therefore not all of the participants wrote about each theme and the percentages did not always total 100. After the codes were developed, chi square analyses were utilized in order to compare the themes found based on the type of event as well as gender of the participant.

Results

The participants reported experiencing a mean of 38.68 (women: 38.62, men: 38.73) total events over the course of 14 days, leading to an average of 2.8 events a day. These events were divided across the three types, including sexual objectification events (women: M = 18.00, men: M = 13.41) gender role stereotype events (women: M = 10.77, men: M = 13.82) and demeaning and derogatory events (women: M = 9.85, men: M = 11.50). There were no significant differences between women and men on the total number of events experienced or the number of each type of event.

Each day, the participants selected one event to describe in more detail. This produced a total of 1008 events, which were then analyzed. Eighteen percent of these events were reported by men (N = 183), with women describing 82% of the events (N = 825). Although the women reported the majority of the experiences, key differences were found between women’s and men’s experiences based on the variables examined (such differences are outlined below) indicating that there were enough men included in the study to have sufficient power. However, as the percentages of events described by women and men were so different, nonsignificant findings related to gender should be interpreted with caution.

A chi-square analysis demonstrated that the types of events were not evenly distributed, χ2 (2) = 70.09, p < .001. Sexual objectification events were the most common (N = 461), followed by demeaning events (N = 281) and gender role stereotype events (N = 266). There were no significant gender differences in the distribution of type of events.

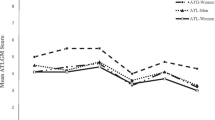

The participants rated their level of positive and negative affect during the event. All participants indicated experiencing higher levels of negative affect (M = 1.6, range = 1.0–4.33) than positive affect (M = 1.42, range = 1.0–5.0), t(1007) = 87.96, p < .01. Women (M = 1.62) reported higher levels of negative affect than did men (M = 1.53), t (1006) = -2.08, p < .05. Further, men (M = 1.67) indicated having higher levels of positive affect than women (M = 1.37), t (1006) = 5.45, p < .05. Levels of positive or negative affect did not differ based on the type of event, perpetrator of event, or setting in which the event took place.

Target of Event

As suggested by Hypothesis 1a, women and men reported experiences in which they were targeted directly as an individual as well as instances in which their group was targeted (see Table 1). For both men and women, the targets of the gender prejudice event were most often the participant themselves (women: 48%, men: 45%), although both also reported cases in which their group was targeted (women: 38%, men: 20%). One man wrote, “Particular males felt that it is inappropriate for a man to stay home and take care of the kids and let a woman work and make the ends meet in the household.”

Unexpectedly, women and men also reported experiences in which they witnessed another person being targeted. Women and men wrote about a number of events which involved another group being targeted and the participant feeling offended. Many of the events that the men wrote about involved people making comments about the roles of women, such as “A guy was saying that women aren't worth anything, haven't done anything in the world, and basically that we should be for ‘getting in the kitchen and baking a pie.’” Other times, participants described hearing derogatory jokes about women. “Today I heard a joke about women and their place… ‘What do you tell a woman with two black eyes? Nothing you already told her twice.’”

Some events involved another individual being targeted, where the participant was offended by the incident. For instance, one woman wrote, “There was a girl on campus walking out from Clark [a classroom building] and she was wearing a really short skirt, and a bunch of guys started hooting and hollering at her.” Finally, in some of the events, both genders were targeted simultaneously. All of these events involved targeting both women and men at the same time. These events took place in a range of settings and with various perpetrators, including the media (“The television show Family Guy depicts Peter, the husband, as a working man and his wife, Lois, as a stay-at-home mother.”), during school activities (“In a literature class we were talking about how women should be subordinate and men should be leaders.”), and with peers (“A coworker joked today that women need a reason to cheat, men need a room.”). Most of these events involved setting women and men in opposition to each other and some included overt assumptions that women and men differ innately, such as one student’s experience, “We have a lab class that has to do with body fitness. Every class we have to do different exercises for guys and girls. It is never the same and it is separated to different sides of the room.”

Chi-square analysis was utilized to assess Hypothesis 1b, which stated that the distribution of the types of events would differ based on who was targeted in the incident. The hypothesis was supported, and the distribution of gender role stereotype events (GRSE), sexual objectification events (SOE) and demeaning events (DE) differed based on the target, χ2 (10, 1006) = 204.6, p < .001 (see Table 2).

Perpetrator

A chi-square analysis was used to test Hypothesis 2a and 2b, indicating that there were significant differences in the gender of the perpetrator based on the gender of the participant, χ2 (3, 1008) = 154.6, p < .001. Hypothesis 2a predicted that women would report more male perpetrators than men would and that men would report more female perpetrators than women would. Hypothesis 2b indicated that men would report more same-gender discrimination (events perpetrated by men) than women would report same-gender discrimination (events perpetrated by women). Both of these hypotheses were supported. In particular, women reported that the perpetrator was most often male (N = 441, 54%), with a very small percentage of females being responsible for the events (N = 29, 4%). In contrast, while men indicated that more of the incidents were perpetrated by women (N = 52, 28%) they reported a large percentage of male perpetrators (N = 36, 20%).

Interestingly, many of women’s and men’s descriptions of events committed by women included a caveat of sorts, such as, “Although I don't think this was meant to sound the way it did, a female professor was discussing women who enjoy sailing. She mentioned that it's not a woman's sport, and that a woman who decided to take it up was like ‘a fish out of water.’” None of the descriptions of events perpetrated by men involved such explanations.

The third set of hypotheses suggested that there would be significant gender differences in the relationship between the target and perpetrator. These hypotheses were tested utilizing a chi-square analysis which examined differences between women’s and men’s descriptions of the relationship between the target and perpetrator, χ2 (9, 1008) = 161.9, p < .001 (see Table 3). Hypothesis 3a predicted that women would report a higher percentage of events perpetrated by authority figures than would men. This hypothesis was not supported, and women and men both reported such events, almost to the same degree (Women: (N = 52, 6%; Men: (N = 14, 8%). One female student wrote “I was talking to one of my professors and he made a comment about a certain job being good for women because eventually they will only have to work part-time. Implying that the rest of the time they could spend at home doing ‘womanly’ things.” Another woman reported that “One of m[y] TAs was checking me out today. It was pretty weird.” A male participant described his experience with his professor, writing “One of my instructors seemed to favor a female’s conversation and thoughts on a problem over a man’s.” Another male student talked about his experience in a work setting, “Today my supervisors, all female, ignored several of my suggestions in conversation.”

Hypothesis 3b predicted that women would report a higher percentage of events perpetrated by opposite gender strangers than would men. This hypothesis was supported, and women indicated that a single, non-specific male stranger (N = 205, 25%) was most commonly the perpetrator compared to male participants who indicated that a single, non-specific female stranger was the perpetrator in 13% of the events (N = 23). For example one woman wrote, “A man was talking about how women should dress a certain way and be skinny and sexy.” Women also reported a higher percentage of events perpetrated by a group of male strangers (N = 160, 19%) than men reported events perpetrated by a group of female strangers (N = 13, 7%).

Finally, Hypothesis 3c suggested that men would report a higher percentage of events perpetrated by friends than would women. This hypothesis was also supported, and men reported that their friends were the most common perpetrators of gender prejudice (N = 37, 20%), compared to women’s reports of friends as perpetrators in only 9% of the events. For instance, one male participant wrote “I sat to eat lunch with a couple of friends today and somehow it was brought up that guys should not be nurses.”

As predicted by the fourth set of hypotheses, the type of event differed based on the gender of the perpetrator, χ2 (6, 1008) = 65.41, p < .001 (see Table 4) as well as the relationship between the perpetrator and the target, χ2 (18, 1008) = 218.64, p < .001 (see Table 5). Results of the chi-square analysis supported hypothesis 4a, with the finding that a greater percentage of the events committed by men were sexual objectification events than the events perpetrated by women. In fact, half of the incidents in which men were described as the perpetrator were sexual objectification events (52%), compared to events in which women were cited as the perpetrators, of which 36% were sexual objectification. This difference was even larger when considering perpetrators involving a group of people. Sixty-one percent of the events committed by a group of men consisted of sexual objectification events, while only 25% of the events perpetrated by a group of women were sexual objectification events. The results also supported hypothesis 4b, and there were differences among the types of events perpetrated by a friend, a partner or an acquaintance. While acquaintances perpetrated all three types of events equally often, friends and partners were most likely to perpetrate demeaning and derogatory events.

Setting

Women and men indicated that they experienced gender prejudice across various facets of their life. A one-sample chi-square test demonstrated a significant difference in the percentages of events experienced in different settings, χ2 = 221.7, df = 7, p < .001. There was no significant difference in setting of gender prejudice events for women and men. Men and women reported the media to be the most common setting for gender prejudice (women: 20%, men: 22%). These events included watching television or movies, reading magazines or listening to music. One participant described her experience of “watching rap videos that exploited women as purely sexual objects.”

One hundred and sixteen events (women: 14%, men: 18%) occurred within the school setting or while the student was at work. Many of these events took place during class time, including this student’s experience: “I was participating in a small group discussion in class today, and my comments were ignored or dismissed by the males.” Other events took place on the college campus, but not during class time. One woman wrote, “Sometimes I feel like I have stalkers around the campus.” Another wrote about “walking through campus and having a group of guys stare and gossip at you and you can just tell they are checking you out.” Other events occurred while the students were in the work environment. One man wrote “I was told to ‘stand up like a man’ after this annoying girl at work kept trying to play fight with me.” Another man talked about his experience of sexual objectification in the work place. “While placing files into a cubby for later filing an older female coworker slid past me to reach into another cubby. During which she slid her hands over my should[er]s and waist.”

The students also described events that occurred during social gatherings (women: 11%, men: 12%), such as, “Friends and I were playing ping pong and one guy said that girls couldn't play and that their place was [in] the kitchen, home cleaning, and child raising.” Another woman talked about her experience while spending time with her friends, “At my friend’s house, a group of guys were talking about how engineers needed to be males because they had more of an ability.” Some of these events were more derogatory. One woman wrote, “We were hanging out at a friends house, and I was told ‘Bitch, get me a new beer.’” One hundred and six cases (women: 11%, men: 7%) of gender prejudice took place while the participants were commuting. Many of these events involved sexual objectification. One woman wrote “I was walking the girl I nanny for and some guys were walking by and were whistling at me yelling ‘milf’.” Another participant wrote about her experience walking past a grocery store. “Several men hang out on the College Avenue side of Safeway. I walked by this afternoon and was whistled at and told, ‘You look good, girl, damn,’ in a very sexual manner. I kept walking without looking at them, and more comments followed.”

The students also described events that occurred while they were engaged in common daily life events, such as eating a meal, or running errands like going to the store or gas station, (women: 8%, men: 6%). For example, one participant described, “Today while eating lunch, I heard a joke referring to a women's job as being a cook, maid, and taking care of the kids.” Another wrote, “I was at dinner tonight and overheard a conversation from a table of guys talking about how "bitches" are only good for one thing, sex. That is the only reason they are on this earth, ‘for a good lay.’” One student’s experience describes what happened to her when she went to the store, stating, “Today when I was walking into a store, guys were whistling and blowing kisses at me.” Another woman wrote about being harassed while getting fuel for her car, “I was standing outside at a gas station waiting for my car to fill with gas when several guys in a van drove by and whistled and made remarks at me.”

Students also reported experiencing gender prejudice within their home (women: 6%, men: 6%). For a number of the students who live on campus, the dorms appear to be a common place for such experiences. “This morning a guy came down the hall searching for an iron. He was asking around for an iron complaining about how he couldn't find one and how this was a girl floor and that there should be one.” “I was sitting in my room when my roommate’s boyfriend asked to see something I had so I tossed it to him. And he told me that I threw like a girl.” Off campus housing may present problems as well. One man wrote about how he felt left out because he is the only male in his house, “I have two female roommates and, at times, I feel like because I am the only male in the house that I get alienated and I feel like I can't take part in any of the decisions we should be making as a team.”

Finally, the students described events (women: 7%, men: 5%) that took place while they were either attending or participating in a sports activity. One man wrote, “The thing that bugged me the most is that a friend said that men are suppose[d] to be all into sports; which is not true of all men.” Another man wrote “I run track and field for Colorado State and I was told by this girl at work that that’s homosexual or feminine to shave my legs.” One woman talked about being excluded because she is female “I played in a co-ed flag football game the other night. I understand football pretty well, but still I never got passed the ball. The other girls didn’t either.”

There were significant differences in the type of events based on the setting in which they occurred, χ2 (14, 1006) = 204.9, p < .001. In school and work settings, the types were fairly evenly distributed (SOE: 36%, GRSE: 33%, DE: 31%), while in other settings some types were more or less common than others. For example, sexual objectification was much more common than the other types during events wherein the participants were commuting (SOE: 84%, DE: 10%, GRSE: 6%). Sexual objectification experiences were also common in the media (SOE: 61%, GRSE: 35%, DE: 4%) and during daily life events (SOE: 55%, DE: 25%, GRSE: 20%). In some settings, sexual objectification experiences and demeaning events were much more common than gender stereotype events, including during sporting events (SOE: 52%, DE: 40%, GRSE: 11%) and social settings (SOE: 41%, DE: 41%, GRSE: 18%). Finally, in home environments, demeaning events were the most common (DE: 42%, SOE: 30%, GRSE: 28%).

Discussion

The college students experienced on average more than two gender prejudice events each day, and there were no significant differences between women and men in the frequency of events. The participants’ descriptions of the events provided valuable additional information about the experiences of college students. Using qualitative content analysis, three main themes were identified by the participants, including target, perpetrator, and setting. This study explored how each of these themes was related to the gender of the participant and the type of event experienced.

Men and women reported the affect they experienced during the events. These reports did not differ based on the type of event, perpetrator or setting, but there were gender differences. Specifically, women reported experiencing higher levels of distress than men did during these events, and men reported higher positive affect than the women. These findings suggest that while men may experience the same types of events as women do, they do not perceive them to be as distressful as women do. This may help explain findings indicating that discrimination has greater detrimental impacts of women’s psychological well-being than on men’s (Schmitt et al. 2002). It is possible that men are more likely than women to consider these types of experiences to be “normal” and acceptable behaviors. It is also likely that these events carry less threat for men than they do for women. For example, a man who is “checked out” by a stranger may be more likely to feel flattered whereas a woman being “checked out” may feel objectified or even worry about her physical safety. Further research is needed to better understand how women and men interpret their experiences with these events and whether similar events hold different potential implications to the victim.

Additionally, it is important to note that while men and women did not differ in the number of events they reported, the men were less likely to be the direct target of prejudice during those events. In fact, 23% of men’s responses included an event wherein women as a group were the actual target of the event. While women also wrote about experiences that happened to men, this was at a much lower frequency (2%). This finding suggests that the results of the t-test should be interpreted with caution and do not necessarily indicate that men are targets of gender prejudice with the same frequency that women are.

Men in this study appeared to be aware of the gender prejudice that women experience and chose to write about such events, even though they were given the option of describing their own non-gender prejudice related experiences. This suggests that there is an opportunity for educators to educate men about how to become more aware of the events that happen both to themselves and to women. Many campuses around the country have developed groups that address masculinity and how men can work to end violence against women, including the Men’s Project at Colorado State University, the Interpersonal Violence Response Team at Northern Illinois University, the Sexual and Relationship Violence Prevention group at West Chester University and many others (for a list of campus peer education programs, see www.NOMAS.org)

More research is needed to understand how men and women are impacted when they witness gender prejudice, even if they are not themselves direct targets. In particular, research should explore how they, as witnesses, respond (or do not respond) when they observe someone else being victimized, and whether these responses are the same as those used when a person is targeted directly. This may be impacted by whether they are the only person to witness the event. Historically, research in social psychology has suggested that when others are present, people often do not take action in situations where a norm is being broken or someone needs help; this is a phenomenon termed the “bystander effect” (Latane and Darley 1968, 1970). However, some studies suggest that when the personal implication of the behavior is higher (such as when a person feels personally offended or distressed), a witness is more likely to intervene (Checkroun and Brauer 2002). More research is required to understand how people are impacted when they witness gender prejudice, what factors may influence whether they experience distress or not, as well as what actions they are likely to take.

As hypothesized, there were important interactions between the target of the incident and the type of event. Most of the events that targeted both women and men simultaneously were gender role stereotype events, suggesting that these stereotypes continue to divide women and men based on assumptions made about their acceptable roles within society (Broverman et al. 1972; Deaux and Lewis 1984; Prentice and Carranza 2002; Spence and Buckner 2000). In contrast, when the participants themselves were the targets, sexual objectification experiences were the most common. In fact, sexual objectification experiences were the most common overall. This finding has important implications for the lives of college students. Objectification theory (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997) suggests that individuals who experience sexual objectification learn to self-objectify, which is associated with a variety of problems including increased levels of body shame, restrictive or disordered eating, bulimia symptoms, anorexic symptoms, depressive symptoms, increased anxiety, decreased intrinsic motivation, decreased self-efficacy, increased appearance anxiety, increased shame and disgust, actual versus ideal body weight discrepancy, lowered state self-esteem and lowered math performance (Calogero 2004; Harrison and Fredrickson 2003; Hebl et al. 2004; McKinley 1998; Noll and Fredrickson 1998; Roberts and Gettman 2004; Slater and Tiggemann 2002). While some may dismiss sexual objectification as simply part of the “college experience,” such experiences have the potential to detrimentally impact individuals.

This study also provided valuable information about the perpetrators of gender prejudice. When the gender of the perpetrator was identified, men were overwhelmingly cited as being responsible for the event, both by women and men. It is not surprising that men were reported more often as the perpetrators of gender prejudice against women, as this has been found in previous studies (Glick et al. 2000; Gruber 1998). It is important to recognize this gender difference and try to understand why men are more likely than women to commit gender prejudice. Harper et al. (2005) proposed one model that presents a number of factors involved in the higher proportion of male offenders of student misconduct (including sexual harassment) on college campuses, but more research is needed.

Men reported experiencing much more same gender discrimination than did women. Runtz and O’Donnell (2003) found that men view certain behaviors and comments as “normal male buddy behaviors” (pg. 979) rather than as harassment. DeSouza and Solberg (2004) explored college students’ perceptions of man-to-man sexual harassment and found that across the board, women rated the events as more harassing, needing further investigation and deserving of more punishment than did men. In the present study, men reported that their friends were the most likely perpetrators of gender prejudice, while women most commonly cited strangers as the culprits. It is possible that men are more tolerant of gender discrimination from their friends than are women, and many men may view this type of behavior as being acceptable and expected. Men may engage in behaviors which devalue each other’s masculinity out of their own fear of appearing feminine (Cournoyer and Mahalik 1995). Future research should continue to explore the factors involved in men perpetrating gender prejudice against other men as well as against women. Additionally, studies can examine the differences in how people respond to prejudice perpetrated by their friends versus by strangers.

This study was unique in its exploration of the various settings in which events took place. Both women and men experienced the greatest percentage of events in their interactions with the media, including television, music and magazines. Many research studies have demonstrated the ways in which the media reinforces traditional stereotypes by showing women in domestic settings and men employed outside the home (Bretl and Cantor 1988), advertising toys with a focus on distinct gender differences (Rajecki et al. 1993), portraying boys as engaging in physical aggression (Larson 2003), and focusing on physical attractiveness in female characters more than in male characters (Signorielli and Bacue 1999; Lauren and Dozier 2002). Media literacy programs/classes in college could be helpful ways to reduce potential harmful impacts of media instances of gender prejudice. For example, one study found that a media literacy program increased participants’ skepticism about the realism, similarity, and desirability of media that depict a thin ideal of beauty (Irving and Berel 2001).

The wide range of settings in which gender prejudice events take place is important information. Programs that target the prevention or decrease of such events should span these settings. The fact that types of gender prejudice differed depending on the setting (for example, sexual objectification was much more common than the other types when the participants were commuting) suggests that different environments may be accompanied by different types of gender prejudice. These different environments may also illicit different types of responses; some responses may be more helpful than others, depending on the setting. It is likely that interventions which might work in the school setting will be less effective when a person is experiencing gender prejudice while commuting to work. Future research should also examine the implications of experiencing the events in these various settings. The impact on the college student as well as the coping mechanism selected may vary based on the setting in which the event occurs.

Limitations

It is important to note that the students described their perceptions of the events that took place. It is impossible from this study to truly know the intentions of the perpetrators themselves. For instance, a female participant may report that she was “checked out” by a peer, but that may not have been the peer’s intention. While it is important to note that this study does not allow one to know the intentions of the perpetrators, the perceptions of the victims are often what are valuable. If a person believes that they have been the victim of discrimination (whether that feeling is accurate or not) they may face detrimental complications as a result. Further, much research indicates that people may minimize their experiences of discrimination (Stangor et al. 2003) suggesting that it is more likely that people did not report events that actually happened than it is that they overreported events. Further, a stress and coping model suggests that a person’s perceptions and appraisals about an event will impact how they react to the situation, both in terms of their response to the perceived perpetrator as well as their own emotional response and coping mechanisms (Folkman et al. 1986).

This study asked people to report about incidents where they were the victim. However, it is likely that these college students also perpetrate gender prejudice in their daily lives. Future research could use a similar diary format to ask people to write about times they perpetrate such events.

The small sample size in this study (especially the percentage of men to women) is also a limitation. However, the participants wrote about multiple experiences over the two-week period, resulting in a large number of events. The use of qualitative research in the form of open-ended questions allowed the researchers to gather information about gender prejudice experiences in the participants’ own words. Future research can utilize the themes found in this study to develop a relevant framework for questions to ask in quantitative questionnaires to be administered to larger numbers of women and men. While the format of this study resulted in important new information, the researchers were unable to ask the participants for clarification about their responses or to ask follow up questions. Future studies could utilize individual interviews or focus groups to gather more in depth information.

Conclusions

This research indicates that college students, both women and men, experience gender prejudice in different forms and across various settings. This project demonstrated that there are important differences between women and men in their experiences of such events. This study also found that there were important implications based on the type of the event, suggesting that future studies should examine this aspect in addition to looking at the perpetrator of the event, the target and the setting in which it takes place. As long as women and men experience gender prejudice and the negative consequences associated with such events, it will be important to examine variables that influence the occurrences and how people cope with them.

References

Alexander, S. M. (2003). Stylish hard bodies: branded masculinity in men’s health magazine. Sociological Perspectives, 46, 535–554.

Aubrey, J. S. (2007). The impact of sexually objectifying media exposure on negative body emotions and sexual self-perceptions: Investigating the mediating role of body self-consciousness. Mass Communication & Society, 10, 1–23.

Barickman, R., Paludi, M., & Rabinowitz, V. C. (1992). Sexual harassment of students: Victims of the college experience. In E. Viano (Ed.), Critical issues in victimology: International perspectives (pp. 153–165). New York: Springer.

Baron, R. S., Burgess, M. L., & Kao, C. F. (1991). Detecting and labeling prejudice: Do female perpetrators go undetected? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17, 115–123.

Bretl, D.J., & Cantor, J. (1988). The portrayal of men and women in U.S. television commercials: A recent content analysis and trends over 15 years. Sex Roles, 18, 595–609.

Brinkman, B. G., & Rickard, K. M. (2009). Factors related to college women's responses to gender prejudice. responses considered and reasons given for not responding: Manuscript submitted for publication.

Broverman, I. K., Vogel, S. R., Broverman, D. M., Clarkson, F. E., & Rosenkrantz, P. S. (1972). Sex role stereotypes: A current appraisal. The Journal of Social Issues, 28, 59–78.

Calogero, R. (2004). A test of objectification theory: The effect of male gaze on appearance concerns in college women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 28, 16–21.

Carr, P. L., Ash, A. S., Friedman, R. H., Szalacha, L., Barnett, R. C., Palepu, A., et al. (2000). Faculty perceptions of gender discrimination and sexual harassment in academic medicine. Annals of Internal Medicine, 132, 889–896.

Cleary, J. S., Schmieler, C. R., Parascenzo, I. C., & Ambrosio, N. (1994). Sexual harassment of college students: Implications for campus health promotion. Journal of American College Health, 43, 3–10.

Chekroun, P., & Brauer, M. (2002). The bystander effect and social control behavior: The effect of the presence of others on people’s reactions to norm violations. European Journal of Social Psychology, 32, 853–867.

Cortina, L., Swan, R. J., Fitzgerald, L., & Waldo, C. (1998). Sexual harassment and assault: Chilling the climate for women in academia. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 22, 419–441.

Cournoyer, R. J., & Mahalik, J. R. (1995). Cross-sectional study of gender role conflict examining college-aged and middle-aged men. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 42, 11–19.

Crosby, F. (1984). The denial of personal discrimination. The American Behavioral Scientist, 27, 371–386.

Dansky, B., & Kilpatrick, D. (1997). Effects of sexual harassment. In W. O’Donohue (Ed.), Sexual harassment: Theory, research and treatment (pp. 152–174). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Deaux, K., & Lewis, L. L. (1984). Structure of gender stereotypes: Interrelationships among components and gender label. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 991–1004.

De Souza, E., & Solberg, J. (2004). Women's and men's reactions to man-to-man sexual harassment: Does the sexual orientation of the victim matter? Sex Roles, 50, 623–639.

Dietz-Uhler, B., & Murrell, A. (1992). College students’ perceptions of sexual harassment: Are gender differences decreasing? Journal of College Student Development, 33, 540–546.

Eckes, T., & Trautner, H. M. (eds). (2000). The developmental social psychology of gender. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Fineran, S. (2002). Adolescents at work: Gender issues and sexual harassment. Violence Against Women, 8, 953–967.

Fiske, S. T., & Stevens, L. E. (1993). What's so special about sex? Gender stereotypes and discrimination. In S. Oskamp & M. Costanzo (Eds.), Gender issues in contemporary society. Claremont Symposium on Applied Social Psychology (pp. 173–196). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Fitzgerald, L., & Swan, S. (1995). Why didn't she just report him? The psychological and legal implications of women's responses to sexual harassment. The Journal of Social Issues, 51, 117–138.

Folkman, S., Lazarus, R., Dunkel-Schetter, C., DeLongis, A., & Gruen, R. J. (1986). Dynamics of a stressful encounter: Cognitive appraisal, coping and encounter outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 992–1003.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 173–206.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine.

Glick, P., Fiske, S. T., Mladinic, A., Saiz, J. L., Abrams, D., Masser, B., et al. (2000). Beyond prejudice as simple antipathy: Hostile and benevolent sexism across cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 763–775.

Groesz, L. M., Levine, M. P., & Murnen, S. K. (2002). The effect of experimental presentation of think media images on body satisfaction: A meta-analytic review. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 31, 1–16.

Gruber, J. E. (1998). The impact of male work environments and organizational policies on women’s experiences of sexual harassment. Gender & Society, 12, 301–320.

Harper, S. R., Harris, F., & Mmeje, K. C. (2005). A theoretical model to explain the overrepresentation of college men among campus judicial offenders: Implications for campus administrators. NASPA Journal, 42, 565–588.

Harrison, K., & Fredrickson, B.L. (2003). Women’s sports media, self-objectification and mental health in black and white adolescent females. The Journal of Communication, (June), 216–232.

Hebl, M. R., King, E. B., & Lin, J. (2004). The swimsuit becomes us all: Ethnicity, gender and vulnerability to self-objectification. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 1322–1331.

Hyers, L. L. (2007). Resisting prejudice every day: Exploring women’s assertive responses to anti-black racism, anti-semitism, heterosexism, and sexism. Sex Roles, 56, 1–12.

Irving, L. M., & Berel, S. R. (2001). Comparison of media-literacy programs to strengthen college women's resistance to media images. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 25, 103–111.

Kaiser, C. R., & Miller, C. T. (2004). A stress and coping perspective on confronting sexism. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 28, 168–178.

Kalof, L., Eby, K. K., Matheson, J. L., & Kroska, R. J. (2001). The influence of race and gender on student self-reports of sexual harassment by college professors. Gender & Society, 15, 282–302.

Krieger, N., Waterman, C. H., Bates, L. M., Stoddard, A., Quinne, M. M., Sorensen, G., et al. (2006). Social hazards on the job: Workplace abuse, sexual harassment, and racial discrimination- A study of black, latino, and white low-income women and men workers in the United States. International Journal of Health Services, 36, 51–85.

Krueger, J., & Rothbart, M. (1988). Use of categorical and individuating information in making inferences about personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55, 187–195.

Larson, M. S. (2003). Gender, race, and aggression in television commercials that feature children. Sex Roles, 48, 67–75.

Latane´, B., & Darley, J. M. (1968). Group inhibition of bystander intervention in emergencies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 10, 215–221.

Latane´, B., & Darley, J. M. (1970). The unresponsive bystander: Why doesn’t he help?. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Lauren, M. M., & Dozier, D. M. (2002). Maintaining the double standard: Portrayals of age and gender in popular films. Sex Roles, 52, 437–446.

Lee, V. E., Croninger, R. G., Linn, R., & Chen, X. (1996). The culture of sexual harassment in secondary schools. American Educational Research Journal, 33, 383–417.

Lott, B. (1995). Distancing from women: interpersonal sexist discrimination. In B. Lott & D. Maluso (Eds.), Combating sexual harassment in higher education (pp. 229–244). Washington, DC: National Education Association.

Magely, V. J., Hulin, C. L., Fitzgerald, L. F., & DeNardo, M. (1999). Outcomes of self-labeling sexual harassment. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 84, 390–402.

Mazer, D. B., & Percival, E. F. (1989). Students' experiences of sexual harassment at a small university. Sex Roles, 20, 1573–2762.

McKinley, N. M. (1998). Gender differences in undergraduates’ body esteem: The mediating effect of objectified body consciousness and actual/ideal weight discrepancy. Sex Roles, 39, 113–123.

Morry, M. M., & Staska, S. L. (2001). Magazine exposure: Internalization, self-objectification, eating attitudes, and body satisfaction in male and female university students. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 33, 269–279.

Noll, S., & Fredrickson, B. (1998). A mediational model linking self-objectification, body shame and disordered eating. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 22, 623–636.

O’Neil, J. M. (1981). Male sex role conflicts, sexism, and masculinity: Psychological implications for men, women, and the counseling psychologist. The Counseling Psychologist, 9, 61–80.

O’Neil, J. M., Good, G., & Holmes, S. (1995). Fifteen years of theory and research on men’s gender role conflict: new paradigms for empirical research. In R. F. Levant & W. S. Pollack (Eds.), A new psychology of men (pp. 164–206). New York, NY: Basic Books.

Paludi, M., & Barickman, R. (1991). Academic and workplace sexual harassment: A resource manual. New York, NY: SUNY.

Pope, H. G., Olivardia, R., Gruber, A., & Borowiecki, J. (1999). Evolving ideals of male body image as seen through action toys. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 26, 65–72.

Popovich, P. M., Licata, B. J., Nokovich, D., Martelli, T., & Zoloty, S. (1986). Assessing the incidence and perception of sexual harassment behaviors among American undergraduates. The Journal of Psychology, 120, 387–396.

Prentice, D. A., & Carranza, E. (2002). What women and men should be, shouldn’t be, are allowed to be, and don’t have to be: The contents of prescriptive gender stereotypes. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 26, 269–281.

Rajecki, D. W., Dame, J. A., Creek, K. J., Barrickman, P. J., & Reid, C. A. (1993). Gender casting in television toy advertisements: Distributions, message content analysis, and evaluations. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 2, 307–327.

Reilly, M. E., Lott, B., & Gallogly, S. M. (1986). Sexual harassment of university students. Sex Roles, 15, 333–358.

Roberts, T.-A., & Gettman, J. (2004). Mere exposure: Gender differences in the negative effects of priming on a state of self-objectification. Sex Roles, 51, 17–27.

Rodin, M. J., Price, J. M., Bryson, J. B., & Sanchez, F. J. (1990). Asymmetry in prejudice attribution. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 26, 481–504.

Runtz, M. G., & O’Donnell, C. W. (2003). Students’ perceptions of sexual harassment: Is it harassment only if the offender is a man and the victim is a woman? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 5, 963–982.

Schmitt, M. T., Branscombe, N. R., Kobrynowicz, D., & Owen, S. (2002). Perceiving discrimination against one’s gender group has different implications for well-being in women and men. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 197–210.

Shepela, S. T., & Levesque, L. L. (1998). Poisoned waters: Sexual harassment and the college climate. Sex Roles, 38, 589–611.

Signorielli, N., & Bacue, A. (1999). Recognition and respect: A content analysis of primetime television characters across three decades. Sex Roles, 40, 527–544.

Slater, A., & Tiggeman, M. (2002). A test of objectification theory in adolescent girls. Sex Roles, 46, 343–349.

Spence, J. T., & Buckner, C. E. (2000). Instrumental and expressive traits, trait stereotypes and sexist attitudes. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 24, 44–62.

Stangor, C., Swim, J. K., Sechrist, G. B., Decoster, J., VanAllen, K. L., & Ottenbreit, A. (2003). Ask, answer, and announce: Three stages in perceiving and responding to discrimination. European Review of Social Psychology, 14, 277–311.

Swim, J. K., Cohen, L. L., & Hyers, L. L. (1998). Experiencing everyday prejudice and discrimination. In J. K. Swim & C. Stangor (Eds.), Prejudice: the target’s perspective (pp. 37–60). San Diego, CA: Academic.

Swim, J. K., Hyers, L. L., Cohen, L. L., & Ferguson, M. L. (2001). Everyday sexism: evidence for its incidence, nature, and psychological impact from three daily diary studies. The Journal of Social Issues, 57, 31–53.

Taylor, D. M., Wright, S. C., & Porter, L. E. (1994). Dimensions of perceived discrimination: The personal/group discrimination discrepancy. In M. P. Zanna & J. M. Olson (Eds.), The psychology of prejudice: The Ontario Symposium, 7 (pp. 233–255). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

van Roosmalen, E., & McDaniel, S. A. (1998). Sexual harassment in academia: A hazard to women’s health. Women & Health, 28, 33–54.

Vorauer, J. D., & Kumhyr, S. M. (2001). Is this about you or me? Self-versus other-directed judgments and feelings in response to intergroup interaction. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 706–719.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063–1070.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A

Online diary

Date:Time:

Please indicate the number of times you experienced each incident today. The incident may have happened to you specifically or to another person in your presence. If none, leave blank.

-

1.

___ Heard comments that members of your gender should behave in a certain way or that they should posses particular personality characteristics (women should be “feminine” and men should be “masculine”)

-

2.

___ Experienced unwanted sexual behaviors (pinched, slapped, touched in a sexual way)

-

3.

___ Called a demeaning or degrading label such as slut, bitch, player, etc.

-

4.

___ Heard sexist jokes about members of your gender.

-

5.

___ Were the target of unwanted sexual gestures (masturbation gesturing, etc)

-

6.

___ Heard comments that certain roles or jobs are NOT suitable for members of your gender.

-

7.

___ Ignored in a conversation by members of the opposite sex.

-

8.

___ Heard unwanted sexual comments, whistles, or “catcalls”.

-

9.

___ Heard comments that members of your gender possess lower levels of ability compared to members of the opposite sex.

-

10.

___ Felt like your opinions carried less weight than the opinion of a member of the opposite sex.

-

11.

___ Exposed to media (magazines, TV, music, etc.) that portrayed members of your gender as sexual objects.

-

12.

___ Heard comments that certain jobs or roles are ONLY suitable for members of your gender.

-

13.

___ Heard comments that expressed hostile or negative attitudes toward members of your gender.

-

14.

___ Felt like you were being checked out, ogled, or leered at.

-

15.

___ Exposed to media (magazines, TV, music) that portrayed members of your gender in traditional roles (women as caregivers, men as leaders, etc)

If you indicated that you experienced one of the above, please answer the following questions. If you experienced more than one, please choose the one that you felt was most distressful. If you did not experience any of the above events, please write about a stressful event that you did have today.

1. Describe the event.

Appendix B

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brinkman, B.G., Rickard, K.M. College Students’ Descriptions of Everyday Gender Prejudice. Sex Roles 61, 461–475 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-009-9643-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-009-9643-3