Abstract

This study examined the differences between gay men and lesbian women in their negative attitudes towards gay men and lesbians who either confirm or disconfirm stereotypical gender roles. One hundred thirty-eight gay and lesbian participants read four gender-typed scenarios: in two, a gay student and a lesbian student were portrayed as more stereotypically masculine, and in the other two, two gay and lesbian students were described as more stereotypically feminine. Participants rated the targets on a scale assessing negative emotions. The results showed that the feminine gay male target provoked more negative emotions than the other three targets, among both gay and lesbian participants. Moreover, gay and lesbian participants felt more negative emotions towards the masculine lesbian target than the feminine lesbian one. In the end, while the feminine gay man target elicited more negative emotions than the feminine lesbian target, the masculine gay man target did not elicit more negative emotions than the masculine lesbian one. Implications of the results are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Although the civil rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans* (LGBT) people have been recognised in a large part of the Occidental world, sexual minorities continue to face discrimination, prejudice and negative attitudes across Europe (International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex Association, 2016; Russell & Fish, 2016). The literature investigating heterosexual people’s attitudes towards LGBT people is extensive (Baiocco, Nardelli, Pezzuti, & Lingiardi, 2013; Breen & Karpinski, 2013; Herek, 2000; Hershberger & D'Augelli, 1995; Worthen, Lingiardi, & Caristo, 2016). Even the number of studies analysing attitudes towards LGBT people among people who are sexual minorities themselves is continuing to grow (Lingiardi & Nardelli, 2014; Rubio & Green, 2009; Salvati, Ioverno, Giacomantonio, & Baiocco, 2016).

There are several factors implicated in the negative attitudes towards LGBT people, and some of them differ for heterosexual and sexual minority people. For example, sexual prejudice refers to heterosexual people’s internalization of the stigma attached to sexual minority (Herek, 2009), while internalised sexual stigma refers to LGBT people’s internalization of society’s negative ideology about sexual minorities (Herek, Gillis, & Cogan, 2015), and it describes self-referred negative feelings, attitudes and representations of sexual minorities (Lingiardi, Baiocco, & Nardelli, 2012; Mayfield, 2001).

Literature indicated that negative attitudes towards LGBT people are related to demographic characteristics too (Herek, 2002; Lingiardi et al., 2016; Pacilli, Taurino, Jost, & van der Toorn, 2011; Chi & Hawk, 2016). For example, several studies showed that older people have more negative attitudes towards gay men and lesbians, than younger people (Baiocco et al., 2013; Steffens & Wagner, 2004). Gender was found a relevant predictor of homonegative attitudes too: in particular, studies showed that males have more homonegative attitudes than females (Cohen, Hall, & Tuttle, 2009; Herek, 2002; Lingiardi et al., 2016; Santona & Tognasso, 2017). Moreover, other studies revealed that people with lower education levels had more negative attitudes towards gay men and lesbians than people with higher education levels (Chi & Hawk, 2016; Ohlander, Batalova, & Treas, 2005; Shackelford & Besser, 2007).

Other two important variables implicated in negative attitudes towards homosexuality and sexual minorities are the political orientation (Haddock & Zanna, 1998; Walch, Orlosky, Sinkkanen, & Stevens, 2010; Whitley, 2009) and the religious involvement (Hichy, Coen, & Di Marco, 2015; Jäckle & Wenzelburger, 2014; Piumatti, 2017). Specifically, people with conservative political orientation showed more negative attitudes towards gay men and lesbian than people with a liberal and progressive political orientation (Pacilli et al., 2011; Whitley & Aegisdttir, 2000; Worthen et al., 2016). Moreover, people with a greater religious involvement had more negative attitudes towards sexual minority people than less religious involving people (Reese, Steffens, & Jonas, 2014; Stulhofer & Rimac, 2009).

An additional factor often considered in studies on homonegativity is the lack of personal knowledge of gay men and lesbians (Lytle, Dyar, Levy, & London, 2017; Seger, Banerji, Park, Smith, & Mackie, 2016; Smith, Axelton, & Saucier, 2009; Walch, Orlosky, Sinkkanen, & Stevens, 2010), according to “contact hypothesis” by Allport (1954). These studies demonstrated that people with lower or no personal contacts with LGBT people tend to hold more negative attitudes towards homosexuality and sexual minorities than people with greater contacts with LGBT people. Costa, Pereira, and Leal (2015) showed that a lack of interpersonal contact might be associated with more hostility against them too. There is also a growing literature that investigated personality and psychological characteristics as correlates to homonegative attitudes such as right-wing authoritarianism (Cramer, Miller, Amacker, & Burks, 2013; Lingiardi et al., 2016; Pacilli et al., 2011), social dominance orientation (Whitley & Aegisdttir, 2000; Whitley & Lee, 2000) and being closed to experience (Barron, Struckman-Johnson, Quevillon, & Banka, 2008; Miller, Wagner, & Hunt, 2012; Shackelford & Besser, 2007).

One of the most important elements affecting attitudes towards sexual minorities for both heterosexual and LGBT people is the violation of gender roles, a set of societal norms dictating the types of behaviours which are generally considered acceptable, appropriate or desirable for people based on their actual or perceived gender or sexuality (Cohen et al., 2009; Glick, Gangl, Gibb, Klumpner, & Weinberg, 2007; Hunt, Fasoli, Carnaghi, & Cadinu, 2016). It has been shown that both sexual minorities and heterosexual people have more negative attitudes towards gay, lesbian and bisexual individuals who display gender-nonconforming behaviours (D’Augelli, Grossman, & Starks, 2006; Rubio & Green, 2009; Skidmore, Linsenmeier, & Bailey, 2006). This is true both for gay or bisexual men who show feminine behaviours (Glick et al., 2007; Salvati et al., 2016) and for lesbian and bisexual women who show masculine behaviours (Carr, 2007, Cohen et al., 2009).

However, most of these studies are focused mainly on samples of heterosexual participants. Instead, the aim of this research was to investigate attitudes towards feminine and masculine gay and lesbian people in an Italian sample composed of gay and lesbian participants. Filling this important gap in the current literature could help us to better understand stereotypes and prejudices faced by gay men and lesbians disconfirming traditional gender role may have to face, even within the LGBT community. Instead, it should constitute a safe place where LGBT people could receive support from discriminations. This study could strengthen the idea that the not adhesion to gender roles could be a more relevant variable than just sexual orientation in predicting negative attitudes towards gay men and lesbians.

Attitudes of Heterosexual and Sexual Minorities Towards Gay Men and Lesbian Women

Past research on heterosexual people has revealed that feminine men are often assumed to be gay, and gay men are seen as possessing traits and interests traditionally associated with straight women (Lehavot & Lambert, 2007; Madon, 1997; Taylor, 1983). Likewise, masculine women are often assumed to be lesbian, and lesbian women are seen as being similar to straight men (Eliason, Donelan, & Randall, 1992; Geiger, Harwood, & Hummert, 2006). These patterns of results are the same for both sexes, as men and women hold similar stereotypes about sexual minorities (Blashill & Powlishta, 2009a; Fasoli, Mazzurega, & Sulpizio, 2016; LaMar & Kite, 1998) and endorse the idea that homosexuality is always associated with the violation of traditional gender roles. In particular, the fact that gay men and lesbian women tend to be stereotyped in ways that are congruent with the opposite gender is well explained by gender inversion hypothesis (Kite & Deaux, 1987) that offers additional support for a bipolar model of gender stereotyping, in which masculinity and femininity are assumed to be in opposition. More specifically, according to the gender inversion hypothesis, gay men and lesbians would be viewed as more similar to other-sex heterosexuals than to same-sex heterosexuals (gay men were seen as more like heterosexual women than either heterosexual men or homosexual women. Homosexual women, on the other hand, were seen as more like heterosexual men than either of the other two groups). Such similarities were expected to be found on a wide range of gender-related attributes (Kite & Deaux, 1987).

However, there are several important differences between male and female heterosexual people in their attitudes towards sexual minorities. For example, heterosexual men have been found to hold more negative attitudes towards homosexuality than heterosexual women (Cohen et al., 2009; Herek, 2002; Lingiardi et al., 2016). Moreover, previous studies have shown that heterosexual men’s attitudes towards gay men are significantly more hostile than their attitudes towards lesbians, whereas heterosexual women’s attitudes do not evidence reliable differences according to whether the target is lesbians or gay men (Herek, 1986; Kite & Whitley, 1996; Louderbeck & Whitley, 1997).

Various explanations have been given for these results. Kite and Deaux (1987) assume that members of each sex may see their own position as the reference point and view the other-sex sexual minority people as moving towards that position. Thus, heterosexual males could see lesbian women as becoming more like them, whereas for heterosexual women, gay men may be seen as adopting their characteristics. Herek (2002) attributed such differences to the different ways that men and women think about homosexuality. Heterosexual men seem to organise their attitudes more in terms of violation of gender roles and sexual identity, which results in different ways of thinking about gay men and about lesbian women. Herek (2000, 2002) argues that gay men and lesbian women probably activate in heterosexual men different sets of feelings and beliefs associated with heterosexual masculine identity. In fact, for several heterosexual men, thinking about lesbian women (and not about gay men) may constitute a positive erotic thought (Louderbeck & Whitley, 1997). In contrast, heterosexual women seem to organise their attitudes more in terms of a minority group which similarly include gay men and lesbian women (Blashill & Powlishta, 2009b; Herek, 2000; Lehavot & Lambert, 2007; Schope & Eliason, 2004). Because of the stigmatised status of homosexuality, some people could experience anxiety at the idea of being labelled gay or lesbian and they may externalise it in hostility towards LGBT people. In addition, consistently with the gender inversion hypothesis, there is still the idea that being labelled gay or lesbian refers to one’s gender as well as one’s sexuality. Men are more likely to experience strong pressures to make demonstrations of their own heterosexual masculinity and this could be achieved, among other things, by rejecting gay men (Herek, 1986, 2000). All women, both heterosexual and lesbian women, are still in an inferior power position in modern society, which is still sexist in many respects (Glick & Fiske, 2001), and women’s possible violations of traditional gender roles are considered less serious than men’s. Thus, women’s identity is less threatened by these violations and consequently, women may be less likely to view homosexuality as a threat to their identity.

The literature about sexual minorities’ attitudes towards gay men and lesbians is more limited. For this reason, in order to be able to do hypotheses about sexual minorities’ attitudes towards gay men and lesbians, we considered the role congruity theory by Eagly and Karau (2002). This theory proposes that at the base of prejudice there is the perceived incongruity between characteristics of members of a social group and the requirements of the social roles that group members occupy or aspire to occupy (Eagly, 2004). When people hold a stereotype about a social group that is incongruent with the attributes that are required for certain social roles, there is a potential for prejudice (Eagly & Karau, 2002; Heilman, 1983). Eagly and Karau (2002) assume that when a person that belongs to a stereotyped group displays an incongruent social role, this inconsistency lowers the evaluation of the group member as an actual or potential occupant of the role. In general, prejudice towards feminine gay men follows from the incongruity that many people perceive between the female characteristics and the requirements of masculine gender roles. Instead, prejudice towards masculine lesbian women follows from the incongruity between the masculine characteristics and the requirements of feminine gender roles.

According this theoretical framework, not only heterosexual people but also sexual minority people could have negative attitudes towards sexual minority people who disconfirm traditional gender roles. Feminine gay men and masculine lesbian women display an inconsistency between the attributes that are required for being men and women and the observed characteristics that violate such gender roles. Again, the role congruity theory affirms that the incongruence to gender roles could be a more relevant variable than just sexual orientation in predicting negative attitudes towards gay men and lesbians. Specifically, lesbian women and gay men could have negative attitudes towards feminine gay men and masculine lesbian women because they do not want to be perceived respectively as less feminine and as less masculine than heterosexual women and men. The fact that feminine gay men and masculine lesbian women show themselves as incongruent to all people, independently of their gender or sexual orientation, leads to think that both gay men and lesbian women could have more negative attitudes towards them, exactly like heterosexual men and women.

Consistently, Salvati et al. (2016) showed that, like heterosexual men, even gay participants may feel a negative emotion towards a gay man who disconfirms male gender roles. Moreover, Sánchez and Vilain (2012) and Sánchez, Blas-Lopez, Martínez-Patiño, and Vilain (2016) showed that most of gay men reported a preference for stereotypically masculine partners and a desire for masculine self-presentation. Unfortunately, to our knowledge, there are not similar studies conducted on lesbian participants, so that these themes in lesbian women seem to be still unexplored.

The Italian Context: Attitude Towards LGB People

Italy is a country where traditional gender norms are widespread and extremely related to the concept of machismo (Baiocco et al., 2013; Hunt, Piccoli, Gonsalkorale, & Carnaghi, 2015. Machismo can be considered overconformity to the traditional male gender role (Lingiardi, Falanga, & D’Augelli, 2005; Petruccelli, Baiocco, Ioverno, Pistella, & D’Urso, 2015). This is not surprising because manifestations of traditional gender norms are more prominent in the Mediterranean countries than in other Western countries (Pacilli et al., 2011). Machismo can be considered an expression of sexism in the Italian society, such as in other Western society, and it is still sexist in many aspects (Ioverno et al., 2017; Pistella, Tanzilli, Ioverno, Lingiardi, & Baiocco, 2017). Sexism is a system of disparities, based on gender, which states the superiority of men on women, by involving beliefs and discriminatory treatments against women (Brown, 2010; Glick & Fiske, 2001). According to the Ambivalent Sexism theory (Glick & Fiske, 1996, 2001), sexism is a multidimensional construct that includes “hostile sexism,” referring to an antipathy towards women, and “benevolent sexism,” referring to a subjectively favourable ideology of protecting women embracing traditional feminine roles. Several studies showed that benevolent sexism represents a barrier to gender equality (Becker & Wagner, 2009; Pistella et al., 2017). Sexism is often related with sexual stigma that has also been labelled homophobia, homonegativity and heterosexism (Herek, 2009). Higher levels of sexism were associated to higher levels of negative attitudes towards LGBT people (Mange & Lepastourel, 2013; Herek & McLemore, 2013; Pistella, Salvati, Ioverno, & Baiocco, 2016).

However, machismo and sexism cannot be considered the only factors explaining negative attitudes towards gay men and lesbians in Italy. The Italian context is unique because of the presence of the Vatican State, which makes it very peculiar respect to other Mediterranean countries such as Spain and Portugal, where levels of negative attitudes are less intense than in Italy (ILGA-Europe, 2016). Indeed, Spain and Portugal legalised same-sex marriage in 2005 and 2010, respectively, while Italy had to wait for 2016 for a law on same-sex unions, considered as a different legal institute from marriage anyway. Unfortunately, the recognition of civil rights for LGBT people progressed and is progressing very slowly because of the strong connections between political and clerical power too. Historically, the Vatican State had a strong influence on Italian development of moral and ethical values, and from Catholic Church’s perspective, LGBT people are seen as a threat to the cultural institution of the family. However, several Italian mayors, independently from national laws, had begun to recognise same-sex unions and several Regional Joints begun to promulgate laws against homophobia, even before that a national law on the theme was promulgate.

Italian research about homonegativity is growing too (Baiocco et al., 2013; Lingiardi et al., 2016; Worthen et al., 2016). Related to the theme of stereotypical gender roles, recent findings on an Italian sample of gay men and heterosexual men (Salvati et al., 2016) showed that feminine gay men elicited more negative emotions compared to masculine gay men. Moreover, such negative reactions towards feminine gay men were more extreme among gay men with high internalised sexual stigma and among heterosexual men with high self-perception of feminine traits. Another recent study conducted in the Italian context (Hunt et al., 2015) exposed young adult gay men to either a threat or an affirmation of their masculinity and then measured reactions to scenarios describing masculine/feminine stereotyped gay men. The findings of this study showed that, under a threat to their masculinity, gay men reported less liking for and less desire to interact with feminine gay men. These findings provide further evidence for the idea that in Italy, gay men express negative attitudes towards stereotypically feminine behaviours exhibited by other gay men because of pressure to conform to masculine norms. The fact that in the Mediterranean countries, and in Italy in particular, traditional gender roles play a role in homonegative attitudes (Baiocco, Argalia, & Laghi, 2014) and the fact that machismo and sexism are still strong could contribute to explain why gay men face prejudices and discrimination in daily life more often than lesbian women (Lingiardi et al., 2012; Pistella et al., 2016).

Current Study and Hypothesis

This study was inspired by several previous studies such as by Glick et al. (2007), Cohen et al. (2009) and Salvati et al. (2016). All of these three studies compared a different number of gender-typed scenarios of gay men and lesbians that were submitted to heterosexual people (men and women) or to gay men but not to lesbian participants. In particular, Glick et al. (2007) compared negative emotions elicited by two targets (one feminine gay man and one masculine gay man) in a sample of only male and heterosexual participants. Salvati et al. (2016) compared negative emotions elicited by the same two targets used by Glick et al. (2007), but in a sample composed of both heterosexual and gay men. Cohen et al. (2009) compared attitudes towards four new gender-typed scenarios (one feminine gay man, one masculine gay man, one feminine lesbian woman and one masculine lesbian woman), but in a sample of only heterosexual people composed of both male and female participants.

The purpose of this research is to contribute to deepening these previous findings by exploring the emotional reaction stimulated by the same four targets used by Cohen et al. (2009), but in a sample of gay and lesbian participants. To our knowledge, no previous study has compared negative emotions in response to the two lesbian scenarios in a sample of gay and lesbian participants. Moreover, to our knowledge, no previous study has investigated attitudes towards gay men and lesbians who confirm and disconfirm traditional gender roles in a sample including lesbian participants. This aspect represents the real innovative feature of this study. This study wants to contribute to fill this gap in the literature. Moreover, given that attitudes towards LGBT people could be even driven by negative reactions to violations of gender norms, it is important that they be taken into account in studies about attitudes towards LGBT people. Thus, the aim of the present research is to contribute to deepening the argument by comparing lesbian and gay participants in their attitudes towards sexual minority people that disconfirm or do not disconfirm traditional gender norms. Lesbian women’s attitudes have always received less attentions than gay men’s ones in previous literature even if they, as well gay men, are part of the LGBT community. This study could extend the previous findings obtained on gay men and on heterosexual people with the vantage of a wider comprehension of discrimination phenomena within the LGBT community that, in its entirety, constitutes a reference environment for all LGBT people.

In line with the previous literature and with the role congruity theory (Eagly & Karau, 2002; Eagly, 2004), we expected the following: (1) The feminine gay man would provoke more negative emotive reactions than the masculine gay man (Glick et al., 2007; Salvati et al., 2016). (2) The masculine lesbian woman would provoke more negative emotions than the feminine lesbian woman (Cohen et al., 2009). (3) The feminine gay man would provoke more negative emotions even than the masculine lesbian woman (Herek, 2000; Kerns & Fine, 1994; Kite & Whitley, 1996). In line with the role congruity theory (Eagly & Karau, 2002; Eagly, 2004), we expected these findings both in gay and lesbian participants.

Method

Participants

The original sample consisted of 155 gay men and lesbians. They were recruited from LGBT organizations outside of the university context in Italy. These associations provide some protect spaces where LGBT people can meet and stay together to discuss about LGBT themes, civil rights and have fun. Some of them have groups organised by range of age that meet together weekly. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) Italian nationality, (b) gay or lesbian sexual orientation, (c) 18–40 years old and (d) having completed the whole set of questionnaires without misunderstandings. According to these criteria, 14 participants were excluded because their sexual orientation was not gay or lesbian (six bisexual, three pansexual, two heterosexual), and five participants were excluded because they did not complete the whole set of questionnaires or completed it with misunderstandings. Some bisexual, pansexual and heterosexual participants were present in the original sample probably because the instruction of involving only gay and lesbian participants was misunderstood or ignored during the snowball sampling procedure. The final sample consisted of 138 participants who declared themselves gay (n = 71; 51.4%) or lesbian (n = 67; 48.6%). The participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 40 (gay men: M = 26.14, SD = 5.05; lesbians: M = 28.28, SD = 5.87). Full descriptive statistics are reported in Table 1.

Procedures

All participants responded individually to all the four different gender-typed scenarios, which were administered face to face. The order of the presentation of the four scenarios was randomised within questionnaires, according to four different orders. Participation in the study was voluntary (no compensation was provided) and anonymous, and participants were encouraged to answer as truthfully as possible. We explained to the participants that the purpose of the research was to examine the relationship between personality traits and attitudes towards homosexuality because we did not want them to know the real research objectives. The participants took about 20–30 min to complete the questionnaire.

Before the data collection commenced, the protocol was approved by the Ethics Commission of the Department of Developmental and Social Psychology at Sapienza University of Rome. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Measures Identifying Information and Sexual Identity

All the participants completed an identifying form to collect data about demographic characteristics, such as gender, age, residency, education, employment, economic status and sexual identity. Participants were asked to report their sexual identity by answering an item with five alternative responses (1 = lesbian, 2 = gay, 3 = bisexual, 4 = heterosexual, 5 = other). In the case of the “other” alternative, participants were allowed to specify their sexual identity.

Manipulation of Scenarios

All the participants were shown all the four scenarios used in the study of Cohen et al. (2009). They were translated and adapted to the Italian context. They were different for gender and for adherence to the gender norms of the person who described himself or herself. The scenarios included (1) a gay masculine young man who described himself with characteristics and interests typically associated to men (GM), (2) a gay feminine young man who described himself with characteristics and interests typically associated to women (GF), (3) a lesbian masculine young woman who described herself with characteristics and interests typically associated to men (LM) and (4) a lesbian feminine young woman who described herself with characteristics and interests typically associated to women (LF). All four targets described themselves explicitly as gay or lesbian. Brief descriptions were preferred to other kind of stimuli such as photo or video for convenience reasons, even if they might be more evocative. This choice was due to the fact that brief descriptions were already used in other studies, showing that they work very well (Cohen et al., 2009; Glick et al., 2007; Salvati et al., 2016). Thus, they just had to be translated for using them. This allowed us to avoid spending a lot of resources to create ex novo new and more complex stimuli such as photo or video.

All the four scenarios could be read in the Appendix.

Negative Emotions Evoked by Scenarios

We measured participants’ negative emotions provoked by each of the four scenarios using a scale consisting of 17 emotions organised on three subscales (Glick et al., 2007). Participants were required to indicate how much the target evoked each emotion in them using a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not in the least) to 7 (through and through). The discomfort subscale consisted of seven emotions related to discomfort (e.g. comfortable, calm and secure; scoring was reversed for this subscale). The second subscale consisted of four items related to fear (e.g. intimidated, nervous and fearful). The third subscale consisted of six items relating to hostility (e.g. frustrated, angry and superior). We calculated an overall negative affect score for each of the four targets from the average of responses to all items. Cronbach’s alphaGM = 0.82; Cronbach’s alphaGF = 0.86; Cronbach’s alphaLM = 0.75; Cronbach’s alphaLF = 0.80.

Adherence to Gender Norms Manipulation Check

We asked participants to respond to two items in order to verify that they had perceived the four scenarios as feminine or masculine. The two items were (1) “In your opinion, how masculine is the young man (or woman) described?” and (2) “In your opinion, how feminine is the young man (or woman) described?” Participants used a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (totally) to indicate the extent to which they perceived the masculinity or femininity the two young lesbian women and the two young gay men, described in the scenarios. The perceived target masculinity score was the average of the scores for the two items with scoring reversed for the feminine item. High scores indicated that the target was perceived as very masculine, while low scores indicated that the target was perceived as very feminine. As reported by Eisinga, Grotenhuis, and Pelzer (2013), the most appropriate reliability coefficient for a two-item scale is the Spearman-Brown statistic that we reported for the four scenarios: r GM = 0.67, r GF = 0.63, r LM = 0.47, r LF = 0.66. Of course, they are quite low, mainly that one regarding masculine lesbian woman, because of only two item scores. Moreover, according to Bem (1981), masculinity and femininity constitute two different dimensions and not two extremes of a one only continuous. Thus, this could be a reason why the two items that we used for the check of manipulation may not be strongly correlated.

Data Analysis

We used the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 22.0) to conduct the analyses. Bivariate correlations were performed to assess the relationships between negative emotions provoked by each of the four targets and the other variables considered in the study. We analysed the differences in negative emotions between gay and lesbian participants elicited by each of the four targets using a mixed ANOVA. We also checked the manipulation effectiveness by using another mixed ANOVA. Before testing our hypotheses with the main mixed ANOVA, we checked possible effects of variables such as education and order of presentation of scenarios with a mixed ANCOVA 2 (participant’s sexual identity (SI): gay vs. lesbian) × 2 (gender of target (GT: male vs. female) × 2 (adherence of target to gender norms (AdT): masculine vs. feminine) × 4 (order of presentation (OP)), with education as covariate. However, because of complexity of the analysis for the high number of variables, because of the lack of effects of education and order of presentation of scenarios and because of results do not differ by results obtained by the main and simpler, ANOVA, we preferred to report only these results for major clarity for the readers.

Results

Correlations

Table 2 shows the correlations between the variables investigated in the study. All correlations between the negative emotions provoked by the four targets were positively related with a low-to-medium effect size that ranged between 0.34 (negative emotions towards the masculine gay man and negative emotions towards the feminine gay man) and 0.56 (negative emotions towards the feminine gay men and negative emotions towards the feminine lesbian woman). Also, all correlations between masculinity perception scores of the four targets were related with a low-to-medium effect size that ranged between 0.31 (masculinity perception scores of the masculine gay man and masculinity perception scores of the feminine lesbian woman) and −0.62 (masculinity perception scores of the masculine gay man and masculinity perception scores of the feminine lesbian woman).

Finally, the data show that participants with more negative emotions towards the feminine gay man tended to report lower scores of masculinity perception of the feminine gay target, r = −0.18, p < 0.05. Similarly, more negative emotions towards the feminine gay man were related to a higher score of masculinity perception of the masculine lesbian target, r = 0.25, p < 0.01. As the literature pointed out, rigid boundaries regarding gender roles are associated to more negative emotions towards feminine gay men or masculine lesbian women.

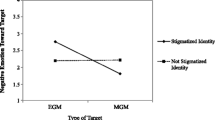

Sexual Identity, Gender of Targets, Adherence of Target to Gender Norms and Negative Emotions Evoked by Scenarios

In order to test our three hypotheses, we conducted a mixed ANOVA 2 (participant’s sexual identity (SI): gay vs. lesbian) × 2 (gender of target (GT): male vs. female) × 2 (adherence of target to gender norms (AdT): masculine vs. feminine), with the last two factors within subjects on EMO scores. The analysis yielded the expected two-way interaction between GT and AdT, F(1, 136) = 9.209, p = 0.003, η p 2 = 0.063. A simple effect analysis showed that in both gay and lesbian participants, (1) the GF target provoked more negative emotions than the GM target (hypothesis 1) and the mean difference was significant, F(1.136) = 3.942, p = 0.049; 2); the LM target provoked more negative emotions than the LF target (hypothesis 2) and the mean difference was significant, F(1.136) = 4.681, p = 0.032; and (3) the GF target provoked more negative emotions even than the LM target (hypothesis 3) and the mean differences were significant, F(1.136) = 42.062, p < 0.001, while the mean difference between the GM target and the LM target was not significant, F(1.136) = 3.355, p = 0.069, although there was a tendency to report more negative emotions towards the GM than the LM. The findings are shown in Fig. 1.

In the end, the not significant three-way interaction SI × GT × AdT, F(1.136) = 0.057, p = 0.811, η p 2 = 0.000, suggests that there were no differences between gay and lesbian participants in feeling more negative emotions towards the four specific targets. The two-way interaction SI × GT was not significant, F(1.136) = 0.098, p = 0.75, while the two-way interaction SI × AdT was significant, F(1.136) = 7.190, p < 0.01. However, this result is not relevant for the purpose of this study. Means and standard deviation by sexual identity on negative emotions elicited by the four scenarios are reported in Table 3.

Manipulation Check

We conducted a mixed ANOVA 2 (participant’s sexual identity (SI): gay vs. lesbian) × 2 (gender of target (GT): male vs. female) × 2 (adherence of target to gender norms (AdT): masculine vs. feminine), with the last two factors within subjects, to test whether participants perceived the GM target as more masculine than the GF target and the LM target as more masculine than the LF target. The results show that the manipulation was effective. In fact, the findings showed a significant effect of AdT on masculinity score, F(1.136) = 450.52, p < 0.001, η p 2 = 0.768, revealing that the GM and LM targets were perceived as more masculine (M = 5.18, SD = 0.06) than the GF and LF targets (M = 2.65, SD = 0.07). There is also a significant effect of GT on masculinity score, F(1.136) = 52.36, p < 0.001, η p 2 = 0.278, revealing that the two male targets were perceived as more masculine (M = 4.15, SD = 0.04) than the two female targets (M = 3.67, SD = 0.04).

Neither the effect of the three-way interaction SI × GT × AdT, F(1.136) = 0.506, p = 0.48, η p 2 = 0.004, nor the effect of the GT × AdT interaction, F(1.136) = 0.714, p = 0.40, η p 2 = 0.005, was significant. The two-way interactions SI × GT and SI × AdT were significant, but they were not reported for parsimonious motives and because they were not relevant for the purposes of the research.

Discussions

The aim of this research was to investigate differences in the emotions elicited by gay men and lesbians who confirm or disconfirm traditional gender norms in a sample of gay and lesbian participants. This study was also intended to contribute to deepening previous findings of studies that investigated negative attitudes towards the same kinds of targets (Cohen et al., 2009; Glick et al., 2007; Salvati et al., 2016) by exploring attitudes towards feminine/masculine gay and lesbian targets in gay and lesbian participants.

Our first hypothesis, that the feminine gay man would elicit more negative emotions than the masculine gay man, both in gay and in lesbian participants, was confirmed. This result confirms the idea behind the role congruity theory by Eagly (2004) and Eagly and Karau (2002). In particular, feminine gay man shows himself as incongruent because his feminine characteristics disconfirm the masculine gender role. Gay men could perceive such incongruity and have more negative emotions towards feminine gay men because of the fear to be labelled as incongruent, just for the fact of being gay. This result is also in line with previous studies that investigated negative attitudes towards feminine and masculine gay men in heterosexual participants (Cohen et al., 2009, Glick et al., 2007) and gay participants (Hunt et al., 2015; Salvati et al., 2016; Sánchez & Vilain, 2012), showing that gender-nonconforming gay men may also suffer discrimination from other gay men. As we hypothesised, lesbian women reported a negative attitude towards feminine gay men too, as well as gay men. This result is in line with the role incongruity theory (Eagly & Karau, 2002; Eagly, 2004) that argues that incongruity is perceived by everybody, regardless of their gender or sexual identity. Lesbian women, as well as gay men, might prefer not to be labelled as incongruent just for the fact of being lesbian.

Our second hypothesis was confirmed too: the masculine lesbian woman, or “butch lesbian woman”, provoked more negative emotions than the feminine lesbian woman, in both gay and lesbian participants (Geiger et al., 2006) and no differences between gay and lesbian participants were found. Even this result fits with the role congruity theory (Eagly & Karau, 2002, Eagly, 2004) because masculine lesbian women, as well as feminine gay men, show an incongruity between their feminine and masculine characteristics. This result is also in line with the literature indicating that both sexual minorities and heterosexual people have more negative attitudes towards lesbian or bisexual women who show masculine behaviours (Carr, 2007) and that both male and female heterosexual people like the feminine lesbian target more than the masculine lesbian target (Cohen et al., 2009).

Finally, the third hypothesis was confirmed too: the feminine gay man would provoke more negative emotions than the masculine lesbian woman, both in gay and lesbian participants. The two-way interaction shown in Fig. 1 seems to show that adhering to the dimension of femininity, by showing an incongruity with the masculine gender norms, leads to more negative consequences, than adhering to the masculinity dimension by showing an incongruity with the female gender norms. When a gay man target showed an incongruity by violating masculine gender norms (GF), he elicited more intense negative emotions than a gay man target adhering masculine gender norms (GM). However, when a lesbian woman target showed an incongruity by violating feminine gender norms (LM), she elicited more negative emotions than lesbian a woman target adhering feminine gender norms (LF), but she elicited less negative emotions than a gay man target violating masculine gender norms. This result seems to suggest that violating masculine gender norms leads to worse consequences than violating feminine gender norms.

A possible explanation of this result could be the fact that attitudes towards gay men tend to be more hostile than attitudes towards lesbian women (Kite & Whitley, 1996; Lingiardi et al., 2012). Western society is still sexist under many aspects (Glick & Fiske, 2001), and women’s possible violations of traditional gender roles are considered less serious than men’s. Other studies have shown that gender norms are more rigidly prescribed for men than women (Herek, 2000). Moreover, compared to women, men have greater loss in their social position if they express same-sex attraction, whereas women have greater opportunities to express same-sex attraction and are less subjected to social penalties for deviating from traditional social roles (Bauermeister, Johns, Sandfort, Eisenberg, Grossman, & D’Augelli, 2010).

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, all measures were self-reported, and a measure of social desirability probably should have been included, because many measures were related to sensitive topics such as negative emotions. The sample size could have been larger, but this is due to the difficulty to contact the particular sample of gay and lesbian participants that constitute a minority with respect to heterosexual participants. Moreover, we did not include two non-stereotypical targets as controls because of the great number of targets to present to each participant. Another limitation was that the generalizability of our findings is limited because we used a convenience sample. The age range was limited to 18–40 years, and results may not be applicable to adolescents and older people. Also, the fact that all participants were from Italy does not permit our findings to be generalised to gay men and lesbians from other countries.

In the end, but most importantly, this study did not consider other very central variables that might have an influence on negative emotions towards gay men and lesbians, such as internalised sexual stigma (Lingiardi et al., 2012) or participants’ adherence to stereotypical masculinity and femininity roles (Salvati et al., 2016). The lack of these two main variables constitutes an important limitation that further researches might try to solve, in order to explore in depth their effects on negative emotions towards gay men and lesbians. This research just wanted to take a first look at negative attitudes towards gay men and lesbians disconfirming traditional gender roles, in a sample of both gay and lesbian participants. The underlying processes or moderators, including internalised sexual stigma and stereotypical roles, will be examined in future studies. Future studies could also corroborate the findings of this first research, integrating them with other and more complex theoretical frameworks such as the BIAS map model (Cuddy, Fiske, & Glick, 2007; Fiske, Cuddy, Glick, & Xu, 2002). They could also use a sample composed of both heterosexual and gay and lesbian participants in order to analyse even differences between lesbian and heterosexual women, because no study has done so yet. In reality, they could also use a more representative sample of sexual minorities by involving bisexual men and women too.

Conclusion

The findings of the present study suggest there is still more work to be done to prevent intolerance and prejudice, not only considering heterosexual people as potential actors of discriminative behaviour, but also taking into account the negative attitudes of sexual minority people. In particular, feminine gay men and masculine lesbian women disconfirming traditional gender roles can face discrimination and prejudice in gay and lesbian communities too. Psychological research may offer an important contribution for limiting the negative effects of prejudice towards gay men and lesbians. Prevention projects, both for heterosexual and sexual minority people, regarding gender stereotypes or negative attitudes towards non-heterosexual sexual identities are more and more necessary in order to promote a sense of inclusion and tolerance, especially in a context such as the Italian one, where traditional gender norms are still very widespread, in order to not create a condition of marginalization among the marginalised (Taywaditep, 2001) and several negative consequence such as victimization (Toomey, Ryan, Diaz, Card, & Russell, 2010).

References

Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Cambridge: Perseus Books.

Baiocco, R., Argalia, M., & Laghi, F. (2014). The desire to marry and attitudes toward same-sex family legalization in a sample of Italian lesbians and gay men. Journal of Family Issues, 35(2), 181–200. doi:10.1177/0192513X12464872.

Baiocco, R., Nardelli, N., Pezzuti, L., & Lingiardi, V. (2013). Attitudes of Italian heterosexual older adults towards lesbian and gay parenting. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 10(4), 285–292. doi:10.1007/s13178-013-0129-2.

Barron, J. M., Struckman-Johnson, C., Quevillon, R., & Banka, S. R. (2008). Heterosexual men’s attitudes toward gay men: A hierarchical model including masculinity, openness, and theoretical explanations. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 9(3), 154–166. doi:10.1037/1524-9220.9.3.154.

Bauermeister, J. A., Johns, M. M., Sandfort, T., Eisenberg, A., Grossman, A., & D’Augelli, A. (2010). Relationship trajectories and psychological well-being among sexual minority youth. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 39(10), 1148–1163. doi:10.1007/s10964-010-9557-y.

Becker, J. C., & Wagner, U. (2009). Doing gender differently—The interplay of strength of gender identification and content of gender identity in predicting women’s endorsement of sexist beliefs. European Journal of Social Psychology, 39(4), 487–508. doi:10.1002/ejsp.551.

Bem, S. L. (1981). Gender schema theory: A cognitive account of sex typing. Psychological Review, 88, 354–364. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.88.4.354.

Blashill, A. J., & Powlishta, K. K. (2009a). Gay stereotypes: The use of sexual orientation as a cue for gender-related attributes. Sex Roles, 61(11–12), 783–793. doi:10.1007/s11199-009-9684-7.

Blashill, A. J., & Powlishta, K. K. (2009b). The impact of sexual orientation and gender role on evaluations of men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 10, 160–173. doi:10.1037/a0014583.

Breen, A. B., & Karpinski, A. (2013). Implicit and explicit attitudes toward gay males and lesbians among heterosexual males and females. The Journal of Social Psychology, 153(3), 351–374. doi:10.1080/00224545.2012.739581.

Brown, R. (2010). Prejudice: Its social psychology (2nd ed.). Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Carr, C. L. (2007). Where have all the tomboys gone? Women’s accounts of gender in adolescence. Sex Roles, 56(7–8), 439–448. doi:10.1007/s11199-007-9183-7.

Chi, X., & Hawk, S. T. (2016). Attitudes toward same-sex attraction and behavior among Chinese university students: Tendencies, correlates, and gender differences. Frontiers in Psychology, 7. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01592

Cohen, T. R., Hall, D. L., & Tuttle, J. (2009). Attitudes toward stereotypical versus counterstereotypical gay men and lesbians. Journal of Sex Research, 46(4), 274–281. doi:10.1080/00224490802666233.

Costa, P. A., Pereira, H., & Leal, I. (2015). “The contact hypothesis” and attitudes toward same-sex parenting. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 12(2), 125–136. doi:10.1007/s13178-014-0171-8.

Cramer, R. J., Miller, A. K., Amacker, A. M., & Burks, A. C. (2013). Openness, right-wing authoritarianism, and antigay prejudice in college students: A mediation model. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(1), 64–71. doi:10.1037/a0031090.

Cuddy, A. J., Fiske, S. T., & Glick, P. (2007). The BIAS map: Behaviors from intergroup affect and stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(4), 631. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.92.4.631.

D’Augelli, A. R., Grossman, A. H., & Starks, M. T. (2006). Childhood gender atypicality, victimization, and PTSD among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 21(11), 1462–1482. doi:10.1177/0886260506293482.

Eagly, A. H. (2004). Prejudice: Toward a more inclusive understanding. In A. H. Eagly, R. M. Baron, & V. L. Hamilton (Eds.), The social psychology of group identity and social conflict: Theory, application, and practice. Washington, DC: APA Books.

Eagly, A. H., & Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109(3), 573. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.109.3.573.

Eisinga, R., Grotenhuis, M. T., & Pelzer, B. (2013). The reliability of a two-item scale: Pearson, Cronbach, or Spearman-Brown? International Journal of Public Health, 58(4), 637–642. doi:10.1007/s00038-012-0416-3.

Eliason, M., Donelan, C., & Randall, C. (1992). Lesbian stereotypes. Health Care for Women International, 13, 131–144. doi:10.1080/07399339209515986.

Fasoli, F., Mazzurega, M., & Sulpizio, S. (2016). When characters impact on dubbing: The role of sexual stereotypes on voice actor/actress’ preferences. Media Psychology, 1–27. doi:10.1080/15213269.2016.1202840.

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J., Glick, P., & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6), 878. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.878.

Geiger, W., Harwood, J., & Hummert, M. L. (2006). College students’ multiple stereotypes of lesbians: A cognitive perspective. Journal of Homosexuality, 51, 165–182. doi:10.1300/J082v51n03_08.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1996). The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(3), 491. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.70.3.491.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (2001). An ambivalent alliance: Hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications for gender inequality. American Psychologist, 56(2), 109–118. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.56.2.109.

Glick, P., Gangl, C., Gibb, S., Klumpner, S., & Weinberg, E. (2007). Defensive reactions to masculinity threat: More negative affect toward effeminate (but not masculine) gay men. Sex Roles, 57(1–2), 55–59. doi:10.1007/s11199-007-9195-3.

Haddock, G., & Zanna, M. (1998). Authoritarianism, values, and the favorability and structure of antigay attitudes. In G. M. Herek (Ed.), Stigma and sexual orientation: Understanding prejudice against lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals (pp. 82–107). Newbury Park: Sage.

Heilman, M. E. (1983). Sex bias in work settings: The lack of fit model. Research in Organizational Behavior, 5, 269–298.

Herek, G. M. (1986). On heterosexual masculinity. Some psychical consequences of the social construction of gender and sexuality. The American Behavioral Scientist, 29, 563–577.

Herek, G. M. (2000). Sexual prejudice and gender: Do heterosexuals’ attitudes toward lesbians and gay men differ? Journal of Social Issues, 56(2), 251–266. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00164.

Herek, G. M. (2002). Gender gaps in public opinion about lesbians and gay men. Public Opinion Quarterly, 66, 40–66. doi:10.1086/338409.

Herek, G. M. (2009). Sexual stigma and sexual prejudice in the United States: A conceptual framework. In Contemporary perspectives on lesbian, gay, and bisexual identities (pp. 65–111). Springer, New York. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-09556-1_4

Herek, G. M., Gillis, J. R., & Cogan, J. C. (2015). Internalized stigma among sexual minority adults: Insights from a social psychological perspective. Stigma and Health, 1(S), 18–34. doi:10.1037/2376-6972.1.S.18.

Herek, G. M., & McLemore, K. A. (2013). Sexual prejudice. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 309–333. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143826.

Hershberger, S. L., & D'Augelli, A. R. (1995). The impact of victimization on the mental health and suicidality of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. Developmental Psychology, 31(1), 65–74. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.31.1.65.

Hichy, Z., Coen, S., & Di Marco, G. (2015). The interplay between religious orientations, state secularism, and gay rights issues. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 11(1), 82–101.

Hunt, C. J., Fasoli, F., Carnaghi, A., & Cadinu, M. (2016). Masculine self-presentation and distancing from femininity in gay men: An experimental examination of the role of masculinity threat. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 17(1), 108–112. doi:10.1037/a0039545.

Hunt, C. J., Piccoli, V., Gonsalkorale, K., & Carnaghi, A. (2015). Feminine role norms among Australian and Italian women: A cross-cultural comparison. Sex Roles, 73(11–12), 533–542. doi:10.1007/s11199-015-0547-0.

ILGA-Europe. (2016). Annual review of the human rights situation of lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and intersex people in Europe. Brussells: ILGA Europe.

Ioverno, S., Carone, N., Lingiardi, V., Nardelli, N., Pagone, P., Pistella, J, … Baiocco, R. (2017). Assessing prejudice toward two-father parenting and two-mother parenting: The beliefs on same-sex parenting scale. Journal of Sex Research. Advance online publication.

Jäckle, S., & Wenzelburger, G. (2014). Religion, religiosity and the attitudes towards homosexuality—A multi-level analysis of 79 countries. J Homosex, 62(2), 207–241. doi:10.1080/00918369.2014. 969071.

Kerns, J. G., & Fine, M. A. (1994). The relation between gender and negative attitudes toward gay men and lesbians: Do gender role attitudes mediate this relation? Sex Roles, 31(5–6), 297–307. doi:10.1007/BF01544590.

Kite, M. E., & Deaux, K. (1987). Gender belief systems: Homosexuality and the implicit inversion theory. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 11, 83–96. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1987.tb00776.x.

Kite, M. E., & Whitley, B. E. (1996). Sex differences in attitudes toward homosexual persons, behaviors, and civil rights a meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(4), 336–353. doi:10.1177/0146167296224002.

LaMar, L., & Kite, M. (1998). Sex differences in attitudes toward gay men and lesbians: A multidimensional perspective. The Journal of Sex Research, 35, 189–196. doi:10.1080/00224499809551932.

Lehavot, K., & Lambert, A. J. (2007). Toward a greater understanding of antigay prejudice: On the role of sexual orientation and gender role violation. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 29, 279–292. doi:10.1080/01973530701503390.

Lingiardi, V., Baiocco, R., & Nardelli, N. (2012). Measure of internalized sexual stigma for lesbians and gay men: A new scale. Journal of Homosexuality, 59(8), 1191–1210. doi:10.1080/00918369.2012.712850.

Lingiardi, V., Falanga, S., & D’Augelli, A. R. (2005). The evaluation of homophobia in an Italian sample. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 34, 81–93. doi:10.1007/s10508-005-1002-z.

Lingiardi, V., & Nardelli, N. (2014). Negative attitudes to lesbians and gay men: Persecutors and victims. In Emotional, physical and sexual abuse (pp. 33–47). Zurich: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-06787-2_3.

Lingiardi, V., Nardelli, N., Ioverno, S., Falanga, S., Di Chiacchio, C., Tanzilli, A., & Baiocco, R. (2016). Homonegativity in Italy: Cultural issues, personality characteristics, and demographic correlates with negative attitudes toward lesbians and gay men. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 13(2), 95–108. doi:10.1007/s13178-015-0197-6.

Louderbeck, L. A., & Whitley Jr., B. E. (1997). Perceived erotic value of homosexuality and sex-role attitudes as mediators of sex differences in heterosexual college students’ attitudes toward lesbians and gay men. The Journal of Sex Research, 34, 175–182. doi:10.1080/00224499709551882.

Lytle, A., Dyar, C., Levy, S. R., & London, B. (2017). Essentialist beliefs: Understanding contact with and attitudes towards lesbian and gay individuals. British Journal of Social Psychology, 56(1), 64–88. doi:10.1111/bjso.12154.

Madon, S. (1997). What do people believe about gay males? A study of stereotype content and strength. Sex Roles, 37, 663–685. doi:10.1007/BF02936334.

Mange, J., & Lepastourel, N. (2013). Gender effect and prejudice: When a salient female norm moderates male negative attitudes toward homosexuals. Journal of Homosexuality, 60(7), 1035–1053. doi:10.1080/00918369.2013.776406.

Mayfield, W. (2001). The development of an internalized homonegativity inventory for gay men. Journal of Homosexuality, 41, 53–76. doi:10.1300/J082v41n02_04.

Miller, A. K., Wagner, M. M., & Hunt, A. N. (2012). Parsimony in personality: Predicting sexual prejudice. Journal of Homosexuality, 59, 201–214. doi:10.1080/00918369.2012.638550.

Ohlander, J., Batalova, J., & Treas, J. (2005). Explaining educational influences on attitudes toward homosexual relations. Social Science Research, 34, 781–799. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2004.12.004.

Pacilli, M. G., Taurino, A., Jost, J. T., & van der Toorn, J. (2011). System justification, right-wing conservatism, and internalized homophobia: Gay and lesbian attitudes toward same-sex parenting in Italy. Sex Roles, 65, 580–595. doi:10.1007/s11199-011-9969-5.

Petruccelli, I., Baiocco, R., Ioverno, S., Pistella, J., & D’Urso, G. (2015). Possible families: A study on attitudes toward same-sex family. Giornale Italiano di Psicologia, 42(4), 805–828. doi:10.1421/81943.

Pistella, J., Salvati, M., Ioverno, S., & Baiocco, R. (2016). Coming-out to family and internalized sexual stigma in bisexual, lesbian and gay people. Journal of Child and Family Studies., 25(12), 3694–3701. doi:10.1007/s10826-016-0505-7.

Pistella, J., Tanzilli, A., Ioverno, S., Lingiardi, V., & Baiocco, R. (2017). Sexism and attitudes toward same-sex parenting in a sample of heterosexuals and sexual minorities: The mediation effect of sexual stigma. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 1–12. doi:10.1007/s13178-017-0284-y.

Piumatti, G. (2017). A mediational model explaining the connection between religiosity and anti-homosexual attitudes in Italy: The effects of male role endorsement and homosexual stereotyping. Journal of Homosexuality, (Online First). doi:10.1080/00918369.2017.1289005.

Reese, G., Steffens, M. C., & Jonas, K. J. (2014). Religious affiliation and attitudes towards gay men: On the mediating role of masculinity threat. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 24(4), 340–355. doi:10.1002/casp.2169.

Rubio, R. J., & Green, R. J. (2009). Filipino masculinity and psychological distress: A preliminary comparison between gay and heterosexual men. Sexuality Research & Social Policy, 6(3), 61–75. doi:10.1525/srsp.2009.6.3.61.

Russell, S. T., & Fish, J. N. (2016). Mental health in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 12, 465–487. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093153.

Salvati, M., Ioverno, S., Giacomantonio, M., & Baiocco, R. (2016). Attitude toward gay men in an Italian sample: Masculinity and sexual orientation make a difference. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 13(2), 109–118. doi:10.1007/s13178-016-0218-0.

Sánchez, F. J., Blas-Lopez, F. J., Martínez-Patiño, M. J., & Vilain, E. (2016). Masculine consciousness and anti-effeminacy among Latino and White gay men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 17(1), 54–63. doi:10.1037/a0039465.

Sánchez, F. J., & Vilain, E. (2012). Straight-acting gays: The relationship between masculine consciousness, anti-effeminacy, and negative gay identity. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41(1), 111–119. doi:10.1007/s10508-012-9912-z.

Santona, A., & Tognasso, G. (2017). Attitudes toward homosexuality in adolescence: An Italian study. Journal of Homosexuality, (Online First). doi:10.1080/00918369.2017.1320165

Schope, R. D., & Eliason, M. J. (2004). Sissies and tomboys: Gender role behaviors and homophobia. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 16, 73–97. doi:10.1300/J041v16n02_05.

Seger, C. R., Banerji, I., Park, S. H., Smith, E. R., & Mackie, D. M. (2016). Specific emotions as mediators of the effect of intergroup contact on prejudice: Findings across multiple participant and target groups. Cognition and emotion, 1–14. doi:10.1080/02699931.2016.1182893.

Shackelford, T. K., & Besser, A. (2007). Predicting attitudes towards homosexuality: Insight from personality psychology. Individual Differences Research, 5(2), 106–114.

Skidmore, W. C., Linsenmeier, J. A., & Bailey, J. M. (2006). Gender nonconformity and psychological distress in lesbians and gay men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 35(6), 685–697. doi:10.1007/s10508-006-9108-5.

Smith, S., Axelton, A., & Saucier, D. (2009). The effects of contact on sexual prejudice: A meta-analysis. Sex Roles, 61(3–4), 178–191. doi:10.1007/s11199-009-9627-3.

Steffens, M. C., & Wagner, C. (2004). Attitudes toward lesbians, gay men, bisexual women, and bisexual men in Germany. Journal of Sex Research, 41(2), 137–149. doi:10.1080/00224490409552222.

Stulhofer, A., & Rimac, I. (2009). Determinants of homonegativity in Europe. Journal of Sex Research, 46(1), 24–32. doi:10.1080/ 00224490802398373.

Taylor, A. (1983). Conceptions of masculinity and femininity as a basis for stereotypes of male and female homosexuals. Journal of Homosexuality, 9, 37–53. doi:10.1300/J082v09n01_04.

Taywaditep, K. J. (2001). Marginalization among the marginalized. Journal of Homosexuality, 42, 1–28. doi:10.1300/J082v42n01_01.

Toomey, R. B., Ryan, C., Diaz, R. M., Card, N. A., & Russell, S. T. (2010). Gender-nonconforming lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: School victimization and young adult psychosocial adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 46(6), 1580–1589. doi:10.1037/a0020705.

Walch, S., Orlosky, P., Sinkkanen, K., & Stevens, H. (2010). Demographic and social factors associated with homophobia and fear of AIDS in a community sample. Journal of Homosexuality, 57(2), 310–324. doi:10.1080/00918360903489135.

Whitley, B. E., & Aegisdttir, S. (2000). The gender belief system, authoritarianism, social dominance orientation, and heterosexuals’ attitudes toward lesbian and gay men. Sex Roles, 42, 947–967. doi:10.1023/A:1007026016001.

Whitley, B. E., & Lee, S. E. (2000). The relationship of authoritarianism and related constructs to attitudes toward homosexuality. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30, 144–170. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816. 2000.tb02309.x.

Whitley, B. J. (2009). Religiosity and attitudes toward lesbians and gay men: A meta–analysis. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 19(1), 21–38. doi:10.1080/10508610802471104.

Worthen, M. G., Lingiardi, V., & Caristo, C. (2016). The roles of politics, feminism, and religion in attitudes toward LGBT individuals: A cross-cultural study of college students in the USA, Italy, and Spain. Sexuality Research and Social Policy (Online First) doi:10.1007/s13178-016-0244-y

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Before the data collection commenced, the protocol was approved by the Ethics Commission of the Department of Developmental and Social Psychology at Sapienza University of Rome.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

This study was not funded by any grant.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Appendix

Appendix

In the next pages the four target descriptions are reported.

The first (GIACOMO) is about feminine gay man;

The second (VIOLA) is about masculine lesbian woman.

The third (IGOR) is about masculine gay man;

The fourth (REBECCA) is about feminine lesbian woman.

Below there’s a brief description that a gay boy has given about himself for a previous study. We asked to him to write about his studies, his interests and hobbies and his main personality characteristics and ambitions.

Please, read carefully the description in order to answer some questions about him at the following pages.

Below there’s a brief description that a lesbian girl has given about herself for a previous study. We asked to her to write about her studies, her interests and hobbies and her main personality characteristics and ambitions.

Please, read carefully the description in order to answer some questions about her at the following pages.

Below there’s a brief description that a gay boy has given about himself for a previous study. We asked to him to write about his studies, his interests and hobbies and his main personality characteristics and ambitions.

Please, read carefully the description in order to answer some questions about him at the following pages.

Below there’s a brief description that a lesbian girl has given about herself for a previous study. We asked to her to write about her studies, her interests and hobbies and her main personality characteristics and ambitions.

Please, read carefully the description in order to answer some questions about her at the following pages.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Salvati, M., Pistella, J., Ioverno, S. et al. Attitude of Italian Gay Men and Italian Lesbian Women Towards Gay and Lesbian Gender-Typed Scenarios. Sex Res Soc Policy 15, 312–328 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-017-0296-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-017-0296-7