Abstract

People with intellectual disabilities (PID) share the same needs for affectionate and intimate relationships as other people. In this study, a review of the literature was performed to (a) examine the opinions reported in the peer-reviewed literature regarding the sexual experiences of PID and (b) identify factors that contribute to the promotion or restriction of sexual expression by PID. Sixteen qualitative articles were identified from electronic databases and reviewed. People with PID were found to exhibit the same spectrum of sexual life as the general population, and three major themes were identified: abstinence, regulation, and autonomy. Some PID preferred to abstain from sex, whereas others considered engagement in sexual activity to have a hand that affects and influences the rights of PID to engage in sexual activity. Further empirical research on the empowerment of sexual expression of PID and the formation of the unintended invisible hand is needed, as this will provide information to families and welfare systems and thus enhance the self-determination and rights of PID to pursue sexual expression and satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Most people consider sexual relationships to be one of the most significant needs in their lives, and people with intellectual disabilities (PID) and their counterparts of people without disabilities share the same human need for affectionate and intimate relationships [1]. In recent decades, the concepts of normalization and social role valorization, particularly regarding the rights of PID, have emerged in both Western and Eastern societies (e.g., United States, Australia, and Hong Kong) [2]. According to the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD), however, PID are often perceived as asexual and as not requiring loving or fulfilling relationships; in other words, their individual right to sexuality is denied [3]. Scholars have also argued that due to various perceptions, the rights of PID to maximize their own potential in terms of sexual health (e.g., dating, entering a relationship, sexual intercourse, or procreation) were limited and not affirmed, defended, or respected as such rights would be for individuals without PID [3, 4]. In fact, the sexuality of PID should not be considered only through the narrow perspective of abuse or pregnancy prevention, but rather through the lens of empowerment to achieve an active sexual life and the sense of fulfillment made available to everyone else [5, 6].

The collection of opinions from PID is considered essential to understanding the sexual lives of PID and informing their families, service providers, and policymakers about their needs [7]. This information could benefit families, service providers, and policymakers by enabling them to recognize existing limitations and align their support with the sexual needs of PID. Based on this notion, this current literature review aims (a) to review the opinions reported in the peer-reviewed literature and thus enable an understanding of the sexual experiences of PID and (b) to identify factors that contribute to the promotion or restriction of sexuality among PID.

Methods

Search Strategy Used in this Study

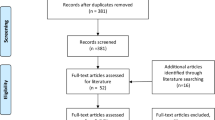

Literature searches were conducted in June 2017. Although the term “intellectual disability” is increasingly used, historically the terms “mental retardation” and “mental handicap” were commonly used for the population of PID [8]. To ensure that most relevant papers would not be excluded from the search results, the term “learning disability” was also considered. The following keywords were selected to meet the aims of the study: intellectual disability, mental retardation, mental handicap, learning disability, sexuality, sexual behavior, sex education, sexual relationship, sexual health, and masturbation. All articles were selected from peer-reviewed journals using the following online databases: ERIC, Ovid Medline, PsycARTICLES, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Science Direct and Social Sciences Citation Index (Fig. 1).

The search covered the period from 2007 to 2017 and identified a huge number (> 3000) of potential papers that might match the aims of the review. The search results were then filtered to yield a final list of articles for review. The review process used the following inclusion criteria: (1) publication in English; (2) focus on issues related to sexuality, sexual life, and relationships, and (3) collection of data from PID. This filter strategy initially identified 30 potential papers, including 4 quantitative and 26 qualitative studies.

To finalize the list for review, all potential papers were reviewed. The paper selection process, which was based on the PRISMA flow chart [9], involved the repeated reading and analysis of potential paragraphs and data. First, four quantitative papers and seven qualitative papers focused on puberty, HIV prevention, sexual violence and prevention, or legal knowledge about sexuality, which did not meet the second criterion of this review. Therefore, these papers were excluded from the review.

To ensure that the remaining 19 qualitative papers were suitable for analysis, the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) was used to evaluate the quality and relevance to the study of each potential paper (see Table 1). Responses to questions included in the CASP are assigned scores of zero, one, or two, which can be summed to yield total scores of 0–20 points [10]. Zero points are given if little or no information is provided by the article. One point indicates that a moderate amount and quality of information has been identified. Two points indicate that the article fully addresses the information required by the aim of the current study. Accordingly, the CASP score is an indicator of the overall quality of an academic paper.

To filter and identify good quality articles from the giant pool of potential papers, articles with CASP scores of 10 or lower were excluded from the review [1]. This process excluded three additional articles. Finally, 16 papers were selected via consensus among all authors of this paper. The details of these papers are summarized in Table 2.

Analysis

The thematic analysis approach was used to identify the thematic components of the current study. A theme captures an important message from the data in relation to the research question and denotes a certain patterned response or connotation within the reviewed data [11]. A thematic analysis, which minimally organizes and describes data in detail [11], should be considered a foundational method for qualitative analyses, which use extremely diverse, complex, and nuanced methods [12]. Several processes were used to extract the themes of the current study: (1) reading and re-reading to generate initial ideas and codes; (2) generation of a thematic “map” by review of the relevant data, and (3) identification of the kernel and core encapsulation of each theme using the “define and refine” method [11].

Results

For the current review, 16 studies with sample sizes between 4 and 32 PID were selected, yielding a coverage of 215 participants. Five of the studies used semi-structured interviews [12, 14,15,16,17], and six used a combination of interviews and observations [6, 18,19,20,21,22]. One described the combined use of interviews and focus groups [23], two reported only the use of focus groups [24, 25], and two interviewed individual participants [1, 26]. The remaining three studies mentioned the use of interviews. Eleven studies (68%) included both genders [6, 13, 14, 16, 17, 20, 22,23,24,25, 27], whereas four studies [15, 18, 19, 21] recruited only female participants and one study [26] recruited only male participants. Three studies [16, 17, 27] used an interpretative phenomenological analysis, four used a thematic analysis [6, 15, 20, 22], two used an ethnographic approach [18, 21], one used a narrative approach [26], and one applied a grounded theory [25]. The remaining five studies did not specify the qualitative approach [13, 14, 19, 23, 24].

Sexual Lives of People with Intellectual Disabilities

Three major themes of the sexual lives of PID were identified from the reviewed papers: abstinence, regulation, and autonomy. In the first theme, self- and other-imposed abstinence were identified as subthemes. In the second theme, the sexual expression of PID under regulatory circumstances was the sole category. For the last theme, self-actualizing and struggling were identified as subthemes. Detailed descriptions of each theme identified in the articles are shown in Table 3.

Abstinence

In the general population, people may actively choose to abstain from sexual activity for various reasons, including a wish to wait for the right person with whom to engage sexually, recovery from an illness, or the maintenance of moral or religious principles. In this review, some PID were found to abstain from sexual intercourse or any type of sexual behavior. As noted, two subthemes were identified: (1) self-imposed abstinence and (2) abstinence imposed by others. According to the review, some PID self-imposed disengagement from any sexual activity, whereas a larger portion of PID reported that they experienced a sexual drive but were forced to regulate or disengage from any sexual expression.

Self-Imposed Abstinence

Under this sub-theme, some PID expressed a perception of sex as undesirable, based on their sexual experiences or perceptions about intercourse. In one study, nine women reported engaging in self-imposed abstinence to avoid sexually transmitted diseases (STD) [18]. In another study, some women with ID also perceived sex as “sickening” [19]. As quoted in the study conducted by Bernert and Odletree: “She hated doing some sexual acts she described as physically painful or making her physically ill.” [19, p. 245]

In addition to STD prevention and the avoidance of undesirable sexual experiences, PID also worried about the consequence of pregnancy. Some PID were constantly reminded by their parents that they were not capable of caring for a baby. In the study by Yau et al. one participant said: “The family suggested to the doctor to sterilize me as I cannot afford to have a baby, and my parents said the baby will be mentally handicapped.” [13, p. 102]

In addition, idealized gender roles appeared to affect the choices of male PID to engage in sexual activity. According to the review, although some male participants expressed interest in friendships with other men and women and most had been in a relationship at some point, few had experienced intimate or sexual relationships. Approximately half of the men wanted to get married and have children, but all stated the importance of being financially independent from the family. Apparently, these men held a fixated and hegemonic perspective of masculinity, in which the ideal woman should be “fit enough” to nurture babies while the ideal man should be the bread-winner [20, 28]. Therefore, the men perceived themselves as incapable of fulfilling this “men’s responsibility” and hence chose to abstain from sexual activity. In a study conducted by Schaafsma et al., a female PID in her 20 s also expressed her concerns regarding caring for a child: “Taking care of a child 24 [hour] a day. I am not sure whether I want that or whether I am able to do that. Because I also have my own problems (…) I already have enough difficulties with myself, what if the child has the same genes as I have?” [14, p. 28], indicating that female participants might also be affected by hegemonic masculinity.

Abstinence as Restrained by Others

Apart from self-imposed abstinence, some PID reported having sexual needs but experiencing restraint by their parents [13]. Some parents even prevented PID from watching any sexual or erotic scenes on television or movies by turning off the media temporarily or asking them to close their eyes [14]. According to Fitzgerald and Withers, a female participant said “My mother said never do it” when asked about her family’s response regarding the participant’s sexual activity with her boyfriend [15, p. 9].

Those restraints were not imposed merely by parents or guardians, but also by service providers [14]. This kind of restraint is not uncommon for service providers to “safeguard” PID from “harm.” However, the imposition of these barrier can have a negative influence on the sexual development of PID and result in sex rejection, regardless of their needs. Under this circumstance, PID may passively choose abstinence. In a study by Fish, a staff member stated that PID could not have physical contact with others privately in their rooms because the whole setting was considered a secure unit, and thus all spaces were classified as public [21]. In another study, a male participant mentioned the regulation set by the hostel in which he was living: “No, I’m not allowed. I can’t … they don’t let me … it’s just the rules in the place. They don’t let anybody stay overnight.” [16, p. 3461].

Intellectual Disability does not weaken a person’s sexual feelings. Most people with mild or moderate ID are capable of expressing sexual desire and making sexual contact [29]. According to the reviewed paper, some PID reported that parents and service providers exercised some governance over their privacy (personal time) and space (e.g., masturbating in their bedrooms). Therefore, although PID expressed desires for sexual and romantic relationships, they were reluctant to talk with their parents or service providers [23]. A 23-year-old male participant expressed his frustration in the study by McClelland and colleagues: “When I was in a group home, I wanted to have sex with another resident, but the group home wouldn’t let us …… I really wanted to get into sex because I guess I was ready at that point. I was 19. But the group home wouldn’t let us. I was kind of upset and frustrated.” [23, p. 814].

This type of restraint was gender symmetrical (i.e., also applied to female PID). In another study, a female PID reported that although her parents were well aware of her boyfriend, she was reluctant to openly express her emotions about her relationship. She told the interviewer: “I won’t tell her how I’m feeling” and “I’d be embarrassed.” [24, p. 908]

The self-imposition of abstinence is not uncommon in the general population, wherein people may choose not to engage in any sexual activity based on personal decisions. Likewise, PID have the same right to choose sexual abstinence. However, this review revealed some concerns in that area. Although some PID chose abstinence because of negative physical and psychological feelings related to sexual experience, more reported concerns regarding pregnancy and the external regulations imposed on them that made them unable to freely enjoy their sex lives. PID were also found to have inadequate knowledge about sexuality, particularly in the areas of sexual health, safer sex practices, and contraception [30, 31]. Undoubtedly, however, PID is a population with disparities [32]. The power indifferences between PID and their families and services providers might affect the process of negotiation. PID might not have adequate power to negotiate with parents and the welfare system regarding the issue of self-determined contraception, regulations on sexual behavior, or the contents of sex education programs, or merely to discuss sexual needs.

Regulation of Sexual Life by Others

The second major theme concerning the sexual lives of PID as generated from the review was “regulation by others”. Although it was clear from the included articles that PID have the same sexual drive as people without disability and that parents and service providers were conscious of the sexual needs of PID, some PID continued to experience regulation of their sexual expression and monitoring by families and agency staff.

People with Intellectual Disabilities can value the meaning of physical contact and its relation to emotional closeness within a relationship [16]. Regardless, PID were often limited to expressing themselves sexually via caressing, holding, hugging, and hair stroking, but not intercourse or other sexual behaviors that require nudity [6]. In one study, a female PID stated: “My mother said it’s alright to have a cuddle and then leave it at that and a kiss but that’s all, not more than that.” [15, p. 9].

Although regulation was imposed, some PID also expressed their satisfaction with this regulated sexual life. One participant said that having her boyfriend’s arms around her made her feel more secure [16]. A participant in another study reported experiencing some degree of personal and physical intimacy with partner (e.g., holding hands, kissing). A female with ID stated that she and her husband enjoyed having time to “lay together, kiss and cuddle – fondle.” [6].

Sexual behavior is any action that leads to sexual fulfillment, which describes a state of positive affect activated by physical stimulation of the genitalia or mental representations of such stimulation [33]. In other words, sexual behavior can be understood as physical contact together with a psychological phenomenon. A sexual act is not merely a solitary activity, but exists on a continuum ranging from solitary activity (e.g., masturbation) to activity with another person (e.g., sexual intercourse, nonpenetrative sex, oral sex). According to the evidence, PID and their counterparts of people without disabilities have similar sexual expressions and sexual needs. Among PID, the frequency of and reason for engaging in sexual activity also vary [15, 25, 26]. However, the theme of externally imposed regulation indicates that the variety of sexual behaviors exhibited by PID was very limited. In addition, this theme shares a similar pattern with that of abstinence in that the family and service providers have taken substantial actions to intervene in the sexual expression of PID.

Autonomy

A person’s sexual life should be sufficiently open to address all manifestations of oppression. The concept of sexual autonomy is centralized on the idea that each human individual should be respected in terms of the existence of sexuality and the space it requires [34]. This review has identified two subcategories related to autonomy. Regarding the first, self-actualization, PID were not found to differ from the individual without PID and were able to share the pleasure of sexual activity in the absence of any pressure. Regarding the second subtheme, the struggle for self-determination, PID struggled with authority figures for the right and space to engage in sexual activity.

Sexual Life and Self-Actualization

In the included articles, PID stated that sex was pleasurable between two people, especially in a committed relationship. Some PID reported having the autonomy to enjoy a sexual relationship [16]. They also described multifarious sexual experiences, including kissing, having a crush, sexual talk, lovemaking, anal intercourse, oral sex, “playing doctor,” marriage, dating, saying “I love you,” fantasy, masturbation, fellatio, vibrators, and pornography [6]. These various sexual expressions impugn the myth that adult PID lack sexual desire or a mature level of sexual development.

Dailey (1981) described sensuality as physical closeness and an awareness of the reciprocal pleasure that each body can provide [35]. This sensuality is not limited to people without disability per se. In one of the 16 identified studies [6], a male PID excitedly proclaimed that the pleasure experienced from kissing, touching, and orgasms was indeed a part of sensuality for PID. Another female participant in the same study further verified the existence of sensuality by defining masturbation as “get[ting] the release out.” Furthermore, a female participant expressed her positive perception of sex with her boyfriend and described sex as an extension of the overall relationship. She described sexual intercourse as an enjoyable and mutual experience [15]. Another participant in that study stated her interpretation of sexual life: “I really actually don’t think of it as sex. I think of it as being with a person that you care for.” [15, p. 244].

According to the reviewed papers, PID could identify a relationship as not merely involving sexual intercourse, but also care and love. In the study by Yacoub and Hall, some cohabiting participants expressed their delight in receiving support from an intimate relationship, and one participant stated: “it’s great not just so you can have each other to cuddle after a tough day, but also for ‘comfort’.” [26, p. 9]

Because sexual activity mostly involves intimate interactions with another individual, it can enhance physical satisfaction and social maturity. However, sex can also be a predicament and often a minefield during the process of personal growth. With proper guidance, young people—both those with ID and without disability—can mature and develop into responsible individuals in intimate relationships.

In one study, a young male participant reported having the autonomy to masturbate and stated that: “It is ok to have masturbation because you are a male, you got to do that sort of thing… It is in your hormones, a natural thing. You do it in private places, you never do it in front of anyone… I just masturbate when I watch porn on the computer. My father, he taught me always to respect women. Everyone used to say you shouldn’t be watching pornography but whenever I had my door locked there would be a smart arse comment, my dad would walk in and say ‘you watching porn’ and I would say maybe and he would ask if he could join me. He always taught me about respecting women…” [25, p. 475]. In the same study, a young woman who participated in a stable sexual relationship with support from her mother and counselor reported learning about the use of condoms and safe sex via her mother’s guidance, her own internet research and practice. She also described her ability to negotiate with her boyfriend about sexual needs and plans.

Struggling to have a Sexual Life

Although some PID experience autonomy regarding a sexual life, others continue to struggle for space or approval from parents or service providers regarding sexual activity [1]. Accordingly, parents or family members, as well as the welfare system, are occasionally the “enemy” of the sexual lives of PID. For example, a female participant in one reviewed study managed to exert her sexual voice and live with her boyfriend, although her mother did not like her to talk about marriage [22]. In another study, people with ID reported exerting more efforts in struggling with sexual life autonomy, especially if they were not part of a heterosexual couple. A young male participant identified himself as gay and actively fought the idea that his sexual orientation was not “normal.” By aligning himself with “any other teenager in the world,” he further emphasized his adulthood by shifting the alignment to “any other grown man” and thus asserted that his sexual identity deserved to be acknowledged and respected, despite his negative expectations [17].

The struggle of PID to enjoy sex not only involves the power of autonomy, but also the physical space. For PID who live at home with family well into adulthood or in a hostel, it may be difficult to obtain a private place in which to be affectionate or have sex. According to Couwenhoven [36], sexual activity often moves into the public arena if limits or restrictions are placed on private sexual expression. In one reviewed study, participants mentioned that restrictions placed by family and service providers had led them to explore different places where they had been sexual, including parks, back alleys, behind stores, bathhouses, the street, and other public settings [23]. One 19-year-old gay group home resident spoke of the complications of weather and his fear of getting caught: “The first time I had sex with someone we went to this park that was nearby and that time I had only half an hour to go on free time so I would have to be back. I hated it… it was in the winter… I was freezing cold and it was like, I was so afraid I was going to get in trouble.” [23, p. 815]

Both cross-sectional and longitudinal individual studies found that sexual well-being is related to life satisfaction [37]. In this review, some PID experienced autonomy regarding their sexual lives and acceptance of their sexuality and demonstrated the capacity to attribute sexual satisfaction to care and love. However, some PID experienced conditional sexual autonomy. Some struggled with the power and control imposed by family and service providers, and others were required to cope with the constraints by using spaces often considered unsafe or inappropriate for sex.

Discussion

Generally speaking, most people without disabilities are self-determined and can freely enjoy a sex life and express their concerns under the spectrum from abstinence to liberty. According to this review, PID experience the same spectrum of sexual expression: some preferred to abstain from sex, whereas others expressed a positive sense of engaging in sexual activity. The three themes synthesized in this review, however, obviously demonstrate that an “unintended invisible hand” created by the PID, their parents, and health professionals influences the rights of PID to engage in sexual behavior.

Sexual well-being can evoke a kaleidoscope of emotions including love, excitement, and tenderness and is a key factor associated with overall mental, physical, and emotional health in humans [38]. Although the family members and service providers of PID acknowledge that sexuality is an essential component of personal identity development, the findings of this review suggest that restrictive or prohibitive approaches remain common at both the individual and institutional levels [39]. This phenomenon is consistent with the findings of previous studies, specifically that PID are often perceived as dependent on others because of a lack of intellectual competence [40] and are even considered permanently incapable of decision-making. Some studies revealed that PID may be considered “eternal children” who are only suitable for participating in monotonous and repetitive tasks [20, 41, 42]. Accordingly, parents might consider it unthinkable to allow a “child” to engage in sexual activity and the fear of such a perceived deviance might evoke a defense mechanism [40]. Health care professionals appeared to experience similar fears. A review study revealed that health care professionals did not proactively discuss sexuality with service users [43]. These professionals’ perceptions of the vulnerability of PID were so robust that they considered it necessary to apply both protection and victim measures to PID [44, 45]. These professional perceptions were also complicated by the fear of possible legal sanction and by ethical and moral conflicts [39, 45]. In summary, families and services providers need to recognize and accept that PID have the same sexual needs and development as people without disability. Nonetheless, both families and service providers encountered tension regarding risk reduction and experienced fear and uncertainty related to the handling of sexuality among PID. These fears and uncertainties have led to the gradual development of the unintended invisible hand and the imposition of regulations on the sexual expression of PID, and possibly even an encroachment of other human rights [27].

The field of rehabilitation has considered the principles of rights, independence, choice, and inclusion of PID since the introduction of “normalization” approximately 40 years ago [27]. In the past decade, increased attention has been directed toward the problems caused by the disparities experienced by PID and the general population (e.g., employment rights, educational opportunities). Both scholars and governments have accredited the significance of encouraging the active involvement of PID in reducing those disparities and promoting positive health and wellness [46]. Unfortunately, this awareness does not seem to have been applied to the context of sexuality among PID, as indicated in this review. Families and service providers have a dual responsibility to empower and protect PID in terms of matters related to sexuality. Although parents tend to be the most influential and consistent coaches of PID in terms of sexuality, service providers certainly play a role in the communication of appropriate messages. However, the three themes that underlie the sexual lives of PID identified in this review suggest that the trajectory of interference by either the family or/and the welfare system is not an uncommon phenomenon.

Aside from reducing this trajectory of interference, PID could be enabled to achieve self-determination and thus empowerment as suggested by some scholars; in one instance, this could be achieved by increasing sexual education and thus enhancing the sexual literacy of PID [47]. Conversely, a previous review revealed that most sex education programs for PID focused on the transmission of knowledge and not on the development of positive attitudes toward sexuality [48]. In addition, the sex education programs for PID were not found to be effective, despite the commitment of the sex education program developers [49]. Consistent with the findings of this review, this inefficacy might be attributed to the prevalence of parental resistance and the unwillingness of teachers and health care professionals to conduct sex education beyond human physiology [15]. The prejudices of staff and parents were consistently identified as an obstacle to the empowerment of PID to self-determine their sexuality [50]. Undoubtedly, parents and health care professionals are committed to enhancing the rights and quality of life of PID. Nevertheless, the trajectory of intervention in the rights of PID to engage in sexual expression is recognizable, and the disparity in sexual identity among PID becomes systematic and socially constructed, consistent with fixed concepts of hegemonic masculinity and femininity [20, 28]. Together, this disparity in identities and the trajectory of interference by parents and health care professionals form the tripartite “unintended invisible hand” and eventually lead to a de facto religious paradigm that comprises autonomy, empowerment, and self-determination but fails to address the original/ultimate function of improving the sexual lives of PID [51].

In the future service development and research might address on various levels (e.g., individual and community). At the individual level, it is essential to examine the perception of sexual self-determination and the factors that currently affect sexuality and sexual expression among PID. At the community level, researchers should use the information gathered from PID to inform parents and professionals with the aim of empowering the sexual self-determination of PIDs via shared understanding and acceptance [8]. Researchers could further foster the sexual self-efficacy of PID by incorporating this information into sexual health promotion initiatives and enabling PID to manage their sexuality in a sensual, satisfying, and safe manner [52]. At the policy development level, researchers could support PID, their parents, and professionals by informing the government of the needs of PID and facilitating policy changes in the perpetuation of systemic barriers. This could be achieved by balancing the crucial components of protection and empowerment of the sexual expression of PID and by cultivating a positive perception of sexuality as expressed by PID [53].

In summary, PID and people without disabilities share a similar wish to enjoy their sex lives and a similar spectrum of sexual expression, and parents and health care professionals are clearly dedicated to nurturing the growth of PID. However, the identification of various themes in this review have led to several recommendations for practice. First, the involvement of PID should not be ignored. Consultation with PID is required if caregivers and the system are to be informed about their needs. Second, increased support should be provided to caregivers who might need to handle the sexual needs of PID, possibly through training workshops, mutual support groups, and the use of internet and multimedia resources. The domain of concern should cover the concept of normalizing sexuality and relationships among PID and validate the anxiety induced by legal and ethical considerations. The advocacy for the rights of sexuality in the community and to drive changes in policy and culture should be addressed as well. Future research with a specific focus on the experiences of family and services providers in providing support to the sexuality of PID would meaningfully enrich the understanding of the phenomenon of the “unintended visible hand”. An examination of any overarching reason for the fear and reluctance experienced by caregivers when empowering PID with sexual life autonomy is highly important. Furthermore, cultural factors or specific meanings associated with sexuality among PID that would influence the families and service providers in terms of assisting engagement in sexual activity should be identified. Only one of the 16 papers included in this review collected data from an Asian population [13]. Generally, studies have found that Asian cultures are significantly more conservative than non-Asian cultures in terms of sexual attitudes [54, 55]. In addition, Asian culture is generally considered to be collectivistic and thus to emphasize interdependence. Several studies have reported that collectivist groups regularly exert a higher level of control over children, encourage conformity with the family and authorities, and exhibit more restraint during social play and eating [56, 57]. Therefore, additional research on cultural differences in the attitudes of PID, their parents, and service providers toward sexual behavior in Asian communities would be valuable.

Limitations

In this study, the themes were generated to examine the range of emergent issues or themes from data generated in other studies. Further empirical research, in which data are directly collected from PID with the intent to focus on their sexual lives, would be a highly valuable addition to the body of knowledge regarding the sexual needs of PID.

Conclusion

People with Intellectual Disabilities and the general population share the same spectrum of sexuality. However, the promotion of autonomy regarding sexual expression is a challenging task in the PID population. Further research focused specifically on the experiences and challenges of PID, their families and services providers in that area is particularly essential. Further research may also help to guide policymakers who handle the social, legal, and ethical concerns regarding the self-determination of PID to exercise their rights to sexual fulfillment and satisfaction.

References

Rushbrooke, E., Murray, C., Townsend, S.: The experiences of intimate relationships by people with intellectual disabilities: a qualitative study. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 27, 531–541 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12091

DiGiulio, G.: Sexuality and people living with physical or developmental disabilities: a review of key issues. Can. J. Hum. Sex. 12, 53–68 (2003)

American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD). Sexualty: joint position statement of AAIDD and the arc. https://aaidd.org/news-policy/policy/position-statements/sexuality#.WQHuCYiGNik (2013). Accessed 28 July 2017

Evans, D.S., McGuire, B.E., Healy, E., Carley, S.N.: Sexuality and personal relationships for people with an intellectual disability. Part II: staff and family carer perspectives. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 53, 913–921 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2009.01202.x

Tepper, M.S.: The missing discourse of pleasure. Sex. Disabil. 18, 283–290 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005698311392

Turner, G.W., Crane, B.: Pleasure is paramount: adults with intellectual disabilities discuss sensuality and intimacy. Sexualities 19, 677–697 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460715620573

Crawford, M.J., Rutter, D., Manley, C., Weaver, T., Bhui, K., Fulop, N., Tyrer, P.: Systematic review of involving patients in the planning and development of healthcare. Br. Med. J. 325, 1263–1267 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.325.7375.1263

Schalock, R.L., Luckasson, R.A., Shogren, K.A.: The renaming of mental retardation: understanding the change to the term intellectual disability. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 45, 116–124 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556(2007)45%5b116:TROMRU%5d2.0.CO;2

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D.G.: Preferred Reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 6, 1–6 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Public Health Resource Unit. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). http://www.cfkr.dk/images/file/CASP%20instrumentet.pdf (2006). Accessed 10 July 2017

Braun, V., Clarke, V.: Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Holloway, I., Todres, L.: The status of method: flexibility, consistency and coherence. Qual. Res. 3, 345–357 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794103033004

Yau, M.K.S., Ng, G.S.M., Lau, D.Y.K., Chan, K.S., Chan, J.S.K.: Exploring sexuality and sexual concerns of adult persons with intellectual disability in a cultural context. Br. J. Dev. Disabil. 55, 97–108 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1179/096979509799103089

Schaafsma, D., Kok, G., Stoffelen, J.M.T., Curfs, L.M.G.: People with intellectual disabilities talk about sexuality: implications for the development of sex education. Sex. Disabil. 35, 21–38 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-016-9466-4

Fitzgerald, C., Withers, P.: ‘I don’t know what a proper woman means’: what women with intellectual disabilities think about sex, sexuality and themselves. Br. J. Learn. Disabil. (2011). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3156.2011.00715.x

Sullivan, F., Bowden, K., Mckenzie, K., Quayle, E.: ‘Touching people in relationships’: a qualitative study of close relationships for people with an intellectual disability. J. Clin. Nurs. 22, 3456–3466 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12375

Wilkinson, V.J., Theodore, K., Raczka, R.: ‘As normal as possible’: sexual identity development in people with intellectual disabilities transitioning to adulthood. Sex. Disabil. 33, 93–105 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-014-9356-6

Bernert, D.J.: Sexuality and disability in the lives of women with intellectual disabilities. Sex. Disabil. 29, 129–141 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-010-9190-4

Bernert, D.J., Odletree, R.J.: Women with intellectual disabilities talk about their perceptions of sex. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 57, 240–249 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2011.01529.x

Björnsdóttir, K., Stefánsdóttir, Á., Stefánsdóttir, G.V.: People with intellectual disabilities negotiate autonomy, gender and sexuality. Sex. Disabil. 35, 295 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-017-9492-x

Fish, R.: ‘They’ve said I’m vulnerable with men’: doing sexuality on locked wards. Sexualities 19, 641–658 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460715620574

Tuner, G.W., Crane, B.: Sexually silenced no more, adults with learning disabilities speak up: a call to action for social work to frame sexual voice as a social justice issue. Br. J. Soc. Work 0, 1–18 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcw133

McClelland, A., Flicker, S., Nepveux, D., Nixon, S., Vo, T., Wilson, C., Marshall, Z.: Seeking safer sexual spaces: queer and trans young people labeled with intellectual disabilities and the paradoxical risks of restriction. J. Homosex. 59, 808–819 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2012.694760

Healy, E., McGuire, B.E., Evans, D.S., Carley, S.N.: Sexuality and personal relationships for people with an intellectual disability. Part I: service-user perspectives. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 53, 905–912 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2009.01203.x

Frawley, P., Wilson, N.J.: Young people with intellectual disability talking about sexuality education and information. Sex. Disabil. 34, 469–484 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-016-9460-x

Yacoub, E., Hall, I.: The sexual lives of men with mild learning disability: a qualitative study. Br. J. Learn. Disabil. 37, 5–11 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3156.2008.00491.x

Rushbrooke, E., Murray, C., Townsend, S.: What difficulties are experienced by caregivers in relation to the sexuality of people with intellectual disabilities? A qualitative meta-synthesis. Res. Dev. Disabil. 35, 871–886 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2014.01.012

Connell, R.W.: Masculinities, 2nd edn. Polity Press, Cambridge (1995)

Craft, A.: Sexuality and mental retardation: a review of the literature. In: Craft, A., Craft, M. (eds.) Sex Education and Counseling for Mentally Handicapped People, pp. 1–37. Kent, Costello (1997)

Galea, J., Butler, J., Lacono, T., Leighton, D.: The assessment of sexual knowledge in people with intellectual disability. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 29(4), 350–365 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1080/13668250400014517

McCarthy, M.: Contraception and women with intellectual disabilities. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 22, 363–369 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2008.00464.x

Krahn, G.L., Walker, D.K., Correa-De-Araujo, R.: Persons with disabilities as an unrecognized health disparity population. Am. J. Public Health 105, S198–S206 (2015). https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302182

Agmo, A.: Functional and Dysfunctional Sexual Behavior: A Synthesis of Neuroscience and Comparative Psychology. Academic Press, San Diego (2007)

Shannaham, D.S.: Sexual ethics, marriage, and sexual autonomy: the landscapes for Muslim at and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered Muslims. Contemp. Islam 3(1), 59–78 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11562-008-0077-4

Dailey, D.: Sexual expression and ageing. In: Berghorn, D., Schafer, D. (eds.) The Dynamics of Ageing: Original Essays on the Processes and Experiences of Growing Old, pp. 311–330. Westview Press, Boulder (1981)

Couwenhoven, T.: Sexuality education: building on the foundation of healthy attitudes. Disabil. Solut. 4, 1–19 (2001)

Stephenson, K.R., Meston, C.M.: The conditional importance of sex: exploring the association between sexual well-being and life satisfaction. J. Sex Marital Ther. 41, 25–38 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2013.811450

World Health Organization (WHO). Sexual and reproductive health. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/sexual_health/sh_definitions/en/ (2010). Accessed 1 Sept 2017

McGuire, B.E., Bayley, A.A.: Relationships, sexuality and decision making capacity in people with an intellectual disability. Curr. Opin. Psychiatr. 24, 398–402 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0b013e328349bbcb

Alphen, L.M., Dijker, A.J., Bos, A.E.R., Borne, B.W., Curfs, L.M.G.: Explaining not-in-my-backyard responses to different social groups: the role of group characteristics and emotions. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2, 245–252 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550610386807

McConnell, D., Llewellyn, G.: Stereotypes, parents with intellectual disability and child protection. J. Soc. Welf. Fam. Law 24(3), 297–317 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1080/09649060210161294

Björnsdóttir, K.: Resisting the reflection: identity in inclusive life history research. Disabil. Stud. Q. 30, 1–17 (2009). https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v30i3/4.1286

Dyer, K., Nair, R.D.: Why don’t healthcare professionals talk about sex? A systematic review of recent qualitative studies conducted in the United Kingdom. J. Sex. Med. 10(11), 2658–2670 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02856.x

Starke, M., Rosqvist, H.B., Kuosmanen, J.: Eternal children? Professionals’ constructions of women with an intellectual disability who are victims of sexual crime. Sex. Disabil. 34, 315–328 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-016-9441-0

Murphy, G.H., O’Callaghan, A.: Capacity of adults with intellectual disabilities to consent to sexual relationships. Psychol. Med. 34, 1347–1357 (2004)

Shogren, K.A., Wehmeyer, M.L., Reese, R.M., O’Hara, D.: Promoting self-determination in health and medical care: a critical component of addressing health disparities in people with intellectual disabilities. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 3, 105–113 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-1130.2006.00061.x

Chinn, D.: Review of interventions to enhance the health communication of people with intellectual disabilities: a communicative health literacy perspective. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 30, 345–359 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12246

Whitehouse, M.A., McCabe, M.P.: Sex education programs for people with intellectual disability: How effective are they? Educ. Train. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. 32, 229–240 (1997)

Schaafsma, D., Stoffelen, J.M.T., Kok, G., Curfs, L.M.G.: Exploring the development of existing sex education programmes for people with intellectual disabilities: an intervention mapping approach. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 26, 157–166 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12017

Abbott, D., Howarth, J.: Still off limits? Staff views on supporting gay, lesbian and bisexual people with intellectual disabilities to develop sexual and intimate relationships. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 20, 116–126 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2006.00312.x

Wehmeyer, M.L.: Beyond self-determination: causal agency theory. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 16, 337–359 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-004-0691-x

Taleporos, G., McCabe, M.: Physical disability and sexual esteem. Sex. Disabil. 19, 131–148 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010677823338

Swango-Wilson, A.: Systems theory and the development of sexual identity for individuals with intellectual/developmental disability. Sex. Disabil. 28, 157–164 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-010-9167-3

Kennedy, M.A., Gorzalka, B.B.: Asian and non-Asian attitudes toward rape, sexual harassment, and sexuality. Sex Roles 46, 227–238 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020145815129

Cheng, Y., Lou, C., Gao, E., Emerson, M.R., Zabin, L.S.: The relationship between external contact and unmarried adolescents’ and young adults’ traditional beliefs in three east asian cities: a cross-sectional analysis. J. Adolesc. Health 50, S4–S11 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.011

Rudy, D., Grusec, J.E.: Authoritarian parenting in individualist and collectivist groups: associations with maternal emotion and cognition and children’s self-esteem. J. Fam. Psychol. 20, 68–78 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.68

Keshavarz, S., Baharudin, R.: Parenting style in a collectivist culture of Malaysia. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. 10, 66–73 (2009)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All Authors declares that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lam, A., Yau, M., Franklin, R.C. et al. The Unintended Invisible Hand: A Conceptual Framework for the Analysis of the Sexual Lives of People with Intellectual Disabilities. Sex Disabil 37, 203–226 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-018-09554-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-018-09554-3