Abstract

In the present study, we examined sexual knowledge, sexual behavior, and psychological adjustment of adolescents with blindness. The sample included 36 Dutch adolescents who are blind, 16 males and 20 females. Results of the interviews revealed no problems regarding sexual knowledge or psychological adjustment. Sexual behavior however, was more at risk. Adolescents with blindness had less sexual experiences and were older in having sexual experiences compared with youth without disabilities in the Netherlands. Subgroup analysis showed that boys with blindness scored higher on self-esteem if they had sexual intercourse. If boys perceived their family as overprotective they less often experienced sexual intercourse. Furthermore, if boys reported more family opposition, they more often had experienced sexual intercourse. These results were not found for girls in this sample. We would like to recommend to youth with visual impairments to be active in leisure activities, outside their homes, in the presence of peers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adolescence is a complicated life stage. For young people adolescence presents a period with various challenges in making their way to adulthood. In this phase, self-reflection is important and it is a period of increased interest in intimate and romantic relationships and sexual relationships as well [1, 2]. For adolescents dating and sexual behavior are important aspects of growing independence [3]. Although a sexual relationship among adolescence is not an ignored topic entirely in social science, little is known about the experience of adolescents themselves on these topics [4]. Especially, there is a lack of information on how adolescents with disabilities experience their intimate, romantic, and sexual relationships. The aim of this study was therefore to examine the sexual knowledge, sexual behavior and psychological adjustment of adolescents with blindness.

Health problems or disabilities, like a visual impairment, threaten the quality and maintenance of relationships with friends and family, whereas at the same time these relationships play an important role in coping with the impairment [5]. Disabilities may result in moderate to severe restrictions in the performance of social roles, related to work, leisure, family, and friendships. Unique stressors associated with disabilities (e.g., social stigma, dependency) place substantial constraints on the ability to maintain and restructure relationships [6–8]. Factors that influence the chances for relationships [9]; proximity, reciprocal liking, similarity, competence in partners, and physical attractiveness, are all effected by having a disability. Due to sociological issues related to disability, adolescents may encounter negative reactions by peers in regard to physical attractiveness, personal characteristics, and their suitability as a friend or mate [10].

The few studies on sexuality among adolescents with a disability mainly address the sexual knowledge, sex education, beliefs, and behaviors among adolescents with physical disabilities. Dating occurs with a significantly lower frequency among adolescents with a physical disability [3, 11]. However, findings are not consistent about the degree to which adolescents with physical disabilities engage in sexual behavior. In contrast to the above-mentioned inquiries, for example, Suris et al. [12] found no difference among physically disabled adolescents as compared with nondisabled adolescents on the frequency with which they were engaged in sexual activity. Yet, recent studies on sexuality and quality of life among young adults with a physical disability illustrated the relatively low frequency of sexual interactions, particularly more intimate forms of sexual interaction [13, 14]. Especially young men with a physical disability reported more sexual problems.

Research shows that adolescents with physical disabilities are poor informed about general sexual knowledge [3, 11, 15]. It is suggested that the lack of knowledge has to do with the fact that these adolescents are often isolated from others of their age and that as a consequence this might lead to a lack of opportunities to learn about (their) sexuality or to engage in social activities or sexual experiences [15]. Parents on the other hand may have little knowledge about disability and sexuality issues. They could be mainly focussed on issues related to the care of their child and less on emerging sexual development and independence [10]. Although research has shown the importance of sex education for adolescents [16], there is much too little attention for sex education for adolescents with disabilities. Several authors [3, 17, 18] showed that sex education at school is often conducted in conjunction with physical education programs. Adolescents with physical disabilities do not participate. As a consequence they are often excluded from this information. Blum et al. [19], for example, show that nearly one-half of all physically disabled adolescents in their research did not receive any type of education related to sex or sexuality in their schools.

Adolescents who are blind or have low vision may experience problems in relating with the outside world, and this may influence their social and sexual development [5, 20]. Not seeing properly might have direct and indirect effects on adolescent social and sexual development. Direct effects of having a visual impairment could be problems with eye contact, missing visual cues on appearance and behavior, difficulties with interpretation of behavior of other persons, fewer possibilities for imitation of appearance and behavior, and problems in mobility [21]. Impairment characteristics like the age of onset, the severity and the kind of impairment (stable or progressive) all could influence these effects. Social and sexual functioning may indirect be limited due to negative societal attitudes, general feelings of insecurity because of being different, feelings of dependence and physical and environmental barriers [5, 10, 22, 23].

In the present study on sexual behavior, we also included the issue of sexual education for adolescents with a visual impairment. It might be that the experiences of these adolescents with sexuality are influenced by a lack of education in this area. Parents, counselors, and teachers could withhold information in the area of sexuality to their adolescents with visual impairments. Parents might be frightened that their child will never achieve a satisfactory relationship as a result of their disability or will get hurt if he or she becomes involved with someone.

Several studies in the late 1990s compared the social activities and social relationships of adolescents with a visual impairment and adolescents without impairments [5, 8, 24–26]. Results illustrated that adolescents who are visually impaired spent significantly more time alone than sighted adolescents did. They often have fewer friends and smaller social networks, especially young men. With respect to maintaining friendships, the visually impaired group had to work harder compared with the sighted group. Their social skills seem lower and the percentage of adolescents with a visual impairment that never had dated was significantly higher than that of sighted adolescents.

Research Objectives

The studies listed above indicate that, generally speaking, adolescents with a visual impairment experience more difficulties and risks in their relationships with peers. Still, there is hardly any information regarding the sexuality experiences and the relationship with psychological adjustment of adolescents with visual impairments. The first aim of the present study was to describe aspects of sexual education, sexual behavior, and psychological adjustment of Dutch adolescents who are blind. The second aim of the study was to explore differences between subgroups within the sample like boys and girls, type of living situation, integrated education background, and time of onset of the visual impairment for these variables. Third, the relations of sexual knowledge with aspects of sexual behavior and psychological adjustment indicators like self-esteem and acceptation of the impairment were investigated. Also relations between indicators of psychological adjustment and sexual behavior variables were studied.

Methodology

Participants

The present study is part of a large nationwide scientific study—the first one in the Netherlands—on personal networks, social support, and psychosocial adjustment of adolescents who are blind or have low vision [5, 27]. This study was carried out in cooperation with the Dutch federation of parents of children with visual impairments (FOVIG). The files of special education schools, ambulant counseling services, and rehabilitation center were used in the recruitment of the respondents. Selection criteria to participate, was that respondents might not have additional impairments, such as hearing and cognitive impairments or learning disabilities.

Eight hundred adolescents between 14 and 24 years of age who were blind or had low vision were invited to participate in the above-mentioned study. Three hundred and sixteen of them (response rate = 37%) were positive to participate. From the pool of these 316 adolescents we selected 46 adolescents to participate in the study on sexuality and blindness. These adolescents were selected because they all used Braille. The response rate was 78% (N = 36). This number of included blind adolescents with no other serious impairments is approximately a quarter of the total population blind adolescents living in the Netherlands. Mean age of this sample was 21.2 years (SD = 2.92). The number of boys and girls was 16 and 20, respectively. Most participants (75%) were blind as result of a congenital disorder. Only a minority (22%) of the participants lived in an institute, 86% had followed always or at sometime in their life special education. No differences were found on these demographic characteristics between boys and girls.

Procedure of Data Collection

Data were collected by means of interviews using a laptop. Using a computer in collecting data on sensitive topics improves the quality of survey data [28]. Pilot interviews were carried out to test the procedures. Interviewers, female students psychology, attended a training program at the University. Next, they visited the participants in their homes and conducted a Computer Assisted Personal Interview (CAPI). Some participants preferred to be interviewed by telephone (Computer Assisted Telephone Interview). No other persons were present during the interview.

Measurements

Sexual Education

To measure aspects that were related to sexual education, we inquired several one-item questions [5, 23], viz: do you think that you have enough information regarding sexuality (1 = no, 2 = yes). It was also asked to whom they would turn if they want information about sexuality (parents, teachers, friends, or media). Other items that were included in the interview are: ‘Do you think you parents overprotected you on the subject of sexuality’ (1 = no, 2 = yes), and ‘Did you ever experienced opposition of your family regarding a date’ (1 = no, 2 = yes).

Sexual Behavior

To measure aspects that were related to sexual behavior, several questions were formulated [5, 23] regarding to falling in love (1 = no, 2 = yes), romantic date (1 = no, 2 = yes), having a relationship (1 = no, 2 = yes), and having sexual intercourse (1 = no, 2 = yes). All these questions were related to lifetime experience. Furthermore, we included questions about how old respondents were at the time of their first romantic relationship, number of romantic relationships and their age at the time they had their first sexual intercourse.

Psychological Adjustment

With respect to psychological adjustment two indicators were included in the present research, viz. self-esteem and acceptance of the impairment. To measure self-esteem, the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale [29] was administered. This scale comprises ten items (e.g., ‘I take a positive attitude toward myself’; 1 = strongly disagree; 4 = strongly agree). Internal reliability in this study (Cronbach’s alpha) was 0.83. A subscale of the Nottingham Adjustment Scale [30] was used to assess the participant’s level of acceptance of their impairment (e.g. In just about everything, my visual impairment is so annoying that I cannot enjoy anything). One positively formulated item was added at the original 9-item scale after a pilot study [5]. The items have response categories ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Cronbach’s alpha in this study was 0.83.

Social Demographic Characteristics

In the interview we also included questions about gender, time of onset of the visual impairment (congenital versus acquired disorder), if respondents (ever) lived in an institute, and if they (ever) attended special education for students with visual impairments.

Data Analysis

Socio demographic and outcome variables were compared between several subgroups (such as males versus females, and regular education versus special education background) and relations between variables were studied using nonparametric tests because of the small sample size. Because of the small sample and the lack of knowledge about the topic of the present study, nonsignificant trends (p < 0.10) are presented in addition to significant effects.

Respondents did have their first romantic date at an average age of 16.5 years. At an average age of 18.5 years they had their first sexual intercourse. The mean number of romantic partners was 2. Moreover, we performed a mean-split on three variables: age first romantic date (1 = <16.5 years old and 2=≥ 16.5 years old), number of romantic partners (1=< 2 partners and 2=≥ 2 partners) and age first sexual intercourse (1=< 18.5 years old and 2=≥ 18.5 years old).

Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive results of different subgroups within the sample on several aspects of sexual education, sexual behavior, and psychological adjustment.

Sexual Education

Our results show that almost 92% of the participants felt that they have enough information regarding sexuality. When the adolescents who are blind want information about sexuality and dating they turn mostly to their parents (33.3%) and to the media (such as internet/tv or books) (30.6%). Only 19.4% of the interviewed adolescents who are blind went to their friend when they want to have information about sexuality. Only one respondent reported to go to the teacher (is not included in Table 1). Almost half of the participants (47.2%) experienced overprotection of their parents regarding dating and sexuality. Thirty-six percent of the adolescents reported feelings of opposition of their close family members towards dating and sexuality.

As shown in Table 1 boys used friends significantly more often as a source for sexual knowledge than girls do, viz 35.0% of the boys and non of the girls. However, with respect to the other subgroups (respondents who lived in an institute versus those who did not live in an institute, those who attended always regular education versus those who did not, and adolescents with a congenital blindness versus a acquired blindness) no significant differences were found on sexual education variables.

Sexual Behavior

Almost all (94.4%) respondents reported that they had ever fallen in love. Most of them (75%) also had romantic dates. From the total group 86.1% had less than two romantic partners and 13.9% had more partners. From the total group 57.7% were younger than 16.5 years of age when they did have their first romantic date and 42.3% were older than 16.5. Twelve participants did not want to answer the question if they had experience with sexual intercourse. From the remaining 24 adolescents, 54.2% (N = 13) answered that they had experience with sexual intercourse. From these small group 53.8% were younger than 18.5 years of age with having sexual intercourse, and 46.2% were older than 18.5 years.

With respect to the studied sexual behavior variables one significant difference was found between the subgroups, viz boys did have their first sexual intercourse at a younger age than girls. With respect to the living situation and the age respondents had at the time of their first romantic date a nonsignificant trend was found. Adolescent who were living in an institute were older at the time of their first date. For all the other subgroups no significant differences (or nonsignificant trends) on sexual behaviors were found (see Table 1).

Psychological Adjustment

Overall, as shown in Table 1, participants reported a high self-esteem and a high level of acceptation of the impairment. No significant differences were found between boys and girls on self-esteem. Respondents who lived in an institute and those who did not live in an institute did not differ significantly from each other on self-esteem. One significant difference was found for the education situation: participants who always attend regular education reported higher self-esteem scores than participants with only special education did.

Quite the same results were obtained with respected to the acceptation of the impairment, viz. no differences between subgroups on demographic variables (see Table 1). For education background the different scores for acceptance were in the same direction as for self-esteem (more positive for regular education), but reached no significant level.

Relations between Sexual Knowledge, Sexual Behavior, and Psychological Adjustment

Correlations were calculated between: on the one hand sexual education variables and on the other hand sexual behavior variables and psychological indicators (a), and between psychosocial indicators and sexual behavior variables (b). Analyses were carried out for the total group, and for boys and girls separately.

First (a), for the total group one significant association was found between the studied sexual education variables and the sexual behavior variables: adolescents with blindness who reported perceiving overprotection from their parents, were relatively older at the time they did have their first sexual intercourse (r = −0.54, p < 0.05). For the total group, there was also a nonsignificant trend between overprotection from parents and self esteem. Respondents who reported more over protection from their parents showed lower scores on self-esteem (r = −0.29, p < 0.10).

The correlation analysis separately for girls showed no associations between the studied sexual education variables and sexual behavior variables. Conversely, the same analysis for boys did show some associations. With respect to self-esteem it was found that boys with more knowledge on sexuality scored higher on self-esteem (r = 0.57, p < 0.05) and acceptation of the impairment (r = 0.51, p < 0.05). It also seems that boys who experienced more overprotection from their family, less often had experienced sexual intercourse (r = −0.66, p < 0.05). A nonsignificant trend was found for reporting more overprotection and lower self-esteem (r = −0.45, p < 0.10). Another nonsignificant trend appeared for family opposition and sexual intercourse: if boys reported more family opposition, they more often had experienced sexual intercourse (r = 0.60, p < 0.10).

With respect to the correlations between psychological adjustment and sexual behavior (b) there was a lack of significant associations between these variables for the total group. Just one nonsignificant trend was found between self-esteem and having experienced sexual intercourse (r = 0.34, p < 0.10): respondents who scored high on self-esteem more often did have experiences with sexual intercourse.

The correlation analysis separately for girls showed no associations at all between psychological adjustment indicators and sexual behavior variables. For boys we found one significant association: boys with higher self-esteem scores had more experience with sexual intercourse (r = 0.67, p < 0.05).

Discussion

The first aim of the present study was to describe aspects of sexual education, sexual behavior, and psychological adjustment of Dutch adolescents who are blind. Overall, the group blind adolescents in this study seemed to have enough knowledge about sexuality, especially provided to them through teachers and their parents. Friends seemed less popular as a source for knowledge on this domain. Almost half of our participants experienced at some level overprotection from their parents, a third also mentioned feeling opposition from their family. The group of adolescents with blindness did have some experience with sexual behaviors, although the degree in which they are involved in it, and the age of starting with sexual behaviors seem to indicate some risks. Overall, the feelings of self-esteem and acceptation of the impairment seem satisfying.

Regarding the second aim of the study to explore differences between subgroups within the sample like boys and girls, type of living situation, integrated education background, and time of onset of the visual impairment, just a few differences were found. Based on these findings, we cannot conclude that one subgroup is more at risk than another. This also has to do with the relatively small sample size. However, we would like to point out that the results in this study are to some extent less positive for boys with blindness than for girls.

Third, the relations of sexual knowledge with aspects of sexual behavior and several indicators for psychological adjustment, like self-esteem and acceptation of the impairment in adolescence were investigated. Also relations between psychological adjustment and sexual behavior variables were studied. No relations with falling in love, dating, number of romantic partners, and the age in dating were found. The variables with significant results or trends in this regard were: overprotection, self-esteem, having sexual intercourse, and the age for having sexual intercourse. Reporting more overprotection, lower self-esteem, no experience with sexual intercourse, and an older age for having sexual intercourse were associated with each other. This was especially the case for the boys with blindness, and not for the girls with blindness.

Comparing our results with recent results regarding the sexual education and sexual behaviors on Dutch youth without disabilities [31], lead to the following remarks. In general, Dutch youth has a good sexual—biological—knowledge. No differences with the group blind participants on this regard seem to emerge. However, the source for information regarding sexuality seems to differ. Youth without disabilities tend to turn more to their friends, while adolescents with blindness turn less to friends and more to their parents. Because of earlier described problems or difficulties with friendships and relations [22] it could be that parents are a more safe and secure haven for support. However, as Harris [32] pointed out, children’s and adolescent’s development is also largely effected by their peers. It could be concluded that adolescents with blindness are at risk in this respect.

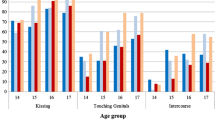

Dutch youth without impairments are starting at a younger age with dating and sexual activities [31]. In our study only a limited amount of sexual activities are included. Nevertheless, we can make some comparisons. For example: the mean age of youth with no disabilities for having their first French kiss is 14.0 years, for blind adolescents the mean age for their first date is 16.5 years. The mean age for youth without disabilities for having their first sexual intercourse is 16.7 years, for blind adolescents this is 18.5 years.

Our results seem to confirm other findings in the literature and also in the rehabilitation and education for youth with visual impairments: they are more at risk regarding dating and sexuality experiences. The frequency of these behaviors is lower and the onset of starting with these behaviors is later. Many factors play a part is the process of understanding why this is happening: characteristics of the person with the impairment, like social competence or being extravert, the way in which the parents stimulate and support their impaired children in this regard, social stigma and negative attitudes of important others in their social environment. The direct and indirect influence of not seeing properly is a very obvious factor in this process, however the magnitude of the impact is difficult to measure. One conclusion is certain: the interplay between these intrapersonal and interpersonal factors is the most important aspect to consider in educating and supporting these adolescents.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. The findings of the present study are based on self-report data. This approach has advantages, but it has disadvantages—like social desirability—as well. In the future, it would be interesting to conduct an in-depth, more qualitative design, including obtaining data from other sources (e.g., parents and peers) in order to clarify present results.

Furthermore, the cross-sectional nature of this study does not allow any conclusions regarding the direction of effects. In the present study, we present for example relations between self-esteem and sexual intercourse. Adolescents who experienced sexual intercourse maybe feel better about themselves, resulting in a high self-esteem. But it is also conceivable that adolescents who experience high levels of self-esteem are more interesting as a romantic partner for somebody else resulting in a sexual relationship. The sample size in this study on sexuality is relatively small, with negative consequences for statistical power. However, the number of included blind adolescents in this study is approximately a quarter of the total population blind adolescents living in the Netherlands. Scientific studies into sexuality of young persons with blindness are scarce. Even more, the combination of sexual behaviors and psychological adjustment received almost no attention at all in research projects with persons with visual impairments. Yet, a larger study could provide us with even more information regarding subgroup differences and associations between variables.

Finally, in the present study, sexual development of adolescents with blindness was investigated. Future research should examine the sexual development of adolescents who are partially sighted as well. This study did not include questions regarding safe sex, sexual attitudes and AIDS. Future research in this direction is needed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study showed that love is not blind. It seems to matter if you have a disability or not, resulting in more difficulties in interacting with peers, in starting with sexual behavior and experimenting with sexual behavior for adolescents who are blind. It does not seem the case that a lack of sexual biological knowledge is the cause of the difficulties in sexual behavior, since no problems with sexual education and knowledge emerged.

Apparently, most sexual behavior involves interaction with other persons. Being different, feeling dependent or awkward are not the preferable conditions for a great starting point in a sexual life. However, the interviewed adolescents with blindness in this study are indicating that in their eyes they are feeling quite okay. Another hypothesis could be: is a nondisabled peer also interested in investing in relations with someone who is blind? In (romantic) relations two parties are involved, and in this study we involved just one of them. Future research could shed some light on this issue.

Practical Implications

Youth with visual impairments tend to stay more at home, perform activities more on their own and spend a lot of their time with family. These circumstances are not ideal to enhance the changes for romantic relationships. Therefore, we would like to recommend to youth with visual impairments to be active in leisure activities, outside their homes, in the presence of peers. While doing various activities, there is joined interest in the same topics and adolescents are able to share information and pleasure. With only a few adjustments, a lot of activities are possible for youth with visual impairments.

To go out and dare to do something you have never done before, takes some courage. Adolescents with blindness need encouragement from significant members in their personal life to feel self-assured in those kinds of activities. Parents seem to provide their blind kids with enough (biological and sexual) information, but could still stimulate them more in going out and teach them the right social skills needed for relating with sighted peers, especially outside their home. Professional caretakers, teachers en staff members also need to pay attention to social cues that are necessary in relating with nondisabled persons in the society.

Social interaction is an essential part of life and a basic assumption for having dating experiences. To be open an honest in stimulating the dating experiences in an active way of your child with impairments is an important step in the rearing style of parents.

Our results show that in contrast with youth without impairments, youth with blindness not often talk with their peers about sexuality. The knowledge level of youth without impairments with regard to blindness and it’s consequences is low. Moreover, the same is true for the youth with blindness themselves. In the transition period of adolescence into young adulthood, they often play hide and seek with regard to their own blindness and it’s consequences. If young persons are not willing to be open about their own impairment, another person could also experience awkwardness and incomprehension as a result. Therefore, it is important that the social interaction partners should have some knowledge about impairments and consciousness about being different. The same applies for the adolescents with blindness themselves. More knowledge and consciousness in both parties, should lead to a better attitude, a more relaxed social situation with higher changes for social and sexual interest in one another.

References

Richards, M.H., Crowe, P.A., Larson, R., Swarr, A.: Developmental patterns and gender differences in the child experiences of peer companionship during adolescence. Child Dev. 69,154–163 (1998)

Sharabine, H., Gershoni, R., Hofman, J.E.: Girlfriend, boyfriend: age and sexual differences in intimate friendships. Dev Psychol. 17,800–808 (1981)

Miller, B.C., Benson B.: Romantic relationship development during adolescence. In: Fruman, W., Bradford Brown, B., Feinberg, C. (eds.) The Development of Romantic Relationships in Adolescence, pp. 99–121. Cambridge university press, Cambridge (1999)

Bradford Brown, B., Feining, C., Furman, W.: Missing the love boat. why researchers have shied away from adolescence romance. In: Fruman, W., Bradford Brown, B., Feinberg, C. (eds.) The Development of Romantic Relationships in Adolescence, pp. 1–16. Cambridge university press, Cambridge (1999)

Kef, S. Outlook on relations. personal networks and psychosocial characteristics of visually impaired adolescents. Thela thesis, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, (1999)

Eide, A.H., Roysamb E.: The relationship between level of disability, psychological problems, social activities, and social networks. Rehabil Psychol. 47,165–183 (2002)

Lyons, R.F., Sullivan, M.J.L., Ritvo, P.G. Relationships in Chronic Illness and Disability. SAGE publications, Thousand Oaks (1995).

Sacks, S.Z., Wolffe, K.E.: Lifestyles of adolescents with visual impairments: an ethnographic analysis. J. Visual.Impair. Blindness 92, 7–17 (1998)

Dwyer, D.: Interpersonal Relationships. Routledge, London (2000)

Gordon, P.A., Tschopp, M.K., Feldman, D.: Addressing issues of sexuality with adolescents with disabilities. Child. Adol. Soc. Work. J. 21 , 513–527 (2004)

Borjeson, M.C., Lagergren, J.: Life conditions of adolescents with myelomeningocele. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 32, 698–706 (1990)

Suris, J.C., Resnick, M.D., Cassuton, N., Blum, R.W.: Sexual behavior of adolescents with chronic disease and disability. J. Adolescent Health. 19, 124–131 (1996)

McCabe, M.P., Taleporos, G.B.A., Dip, G.: Sexual esteem, sexual satisfaction, and sexual behavior among people with physical disability. Arch. Sex. Behav. 32, 359–369 (2003)

McCabe, M.P., Cummins, R.A., Deeks, A.A.: Sexuality and quality of life among people with physical disability. Sex Disabil. 18, 115–123 (2000)

Berman, H., Harris, D., Enright, R., Gilpin, M., Cathers, T., Bukovy, G.: Sexuality and the adolescent with a physical disability. Understandings and misunderstandings. Comp. Ped. Nurs. 22, 183–196 (1999)

Visser, A.P., Van Bilsen, P.: Effectiveness of sex education provide to adolescents. Patient Educ. Couns. 23, 47–160 (1994)

Blackburn, M.: Sexuality, disability and abuse: advice for life ... not just for kids. Child. Care Health Dev. 21, 351–361 (1995)

Shapland, C.: Speak up for health: preparing adolescents with chronic illness or disabilities for independence in health care. PACER Center Inc, Minneapolis (1993)

Blum, R.W., Resnick, M.D., Nelson, R., St. Germaine, A.: Family and peer issues among adolescents with spina bifida and cerebral palsy. Pediatrics 88, 280–285 (1991)

Kef, S., Dekovic, M.: The role of parental and peer support in adolescents well- being: a comparison of adolescents with and without a visual impairment. J Adolescence 27, 453–466 (2004)

Davies, J.: Sexuality Education for Children with Visual Impairments. Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia (1996)

Kalksma, S.: Eye for each other. Research into friendships of youth with a visual impairment (in Dutch: Oog voor elkaar, master thesis). University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam (2005)

Sloep, A., Reek, S.: Love is blind. Research into the perception of dating and sexuality of adolescents who are blind. master thesis. University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam (1998)

Huurre, T.M., Aro, H.M.: Psychosocial development among adolescents with visual impairment. Eur. Child. Adoles. Psych. 7, 73–78 (1998)

Rosenblum, L.P.: Best friendships of adolescents with visual impairments: a descriptive study. J. Visual. Imp. Blindness. 92, 593–608 (1998)

Sacks, S.Z., Wolffe, K.E., Tierney, D.: Lifestyles of students with visual impairments: preliminary studies of social networks. Except Child. 64, 463–478 (1998)

Kef, S.: Psychosocial adjustment and the meaning of social support for visually impaired adolescents. J. Visual. Imp. Blindness. 96, 22–37 (2002)

De Leeuw, E.D., Hox, J.J., Kef, S.: Computer Assisted Self-Interviewing tailored for special populations: overcoming the problems of special interviews and sensitive topics. Field Methods. 15, 223–251 (2003)

Rosenberg, M.: Conceiving the Self. Basic, New York (1979)

Dodds, A.G., Ferguson, E, Flannigan, L.N.H, Hawes, G., Yates, L. The concept of adjustment: a structural model. J. Visual. Imp. Blindness. 88, 487–497 (1994)

De Graaf, H., Meijer, S, Poelman, J., Vanwesenbeeck, I.: Seks Onder Je 25e. Rutgers Nisso Groep/Soa Aids Nederland, Utrecht (2005)

Harris, J.H.: The Nurture Assumption. Why Children Turn out the Way They Do. Touchstone, New York (1999)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Anoushka Sloep and Sandra Reek (educationalists and alumni of the University of Amsterdam) for their contribution in the study on sexual behavior. Parts of this study were funded by the Dutch federation of parents of children with visual impairments (FOVIG) and by InZicht, a Dutch foundation for research concerning persons with visual impairment (grant number 943-01-001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kef, S., Bos, H. Is Love Blind? Sexual Behavior and Psychological Adjustment of Adolescents with Blindness. Sex Disabil 24, 89–100 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-006-9007-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-006-9007-7