Abstract

Research regarding people with visual, hearing, or physical disability and their experiences with partnership is sparse. Existing studies show that experiences with partnership and sexual activity occur both less frequently and later in life. Feelings of inferiority, common beauty standards, stigmatization, immobility, and overprotective parenting are cited as reasons for this. This paper analyzes the influence of gender and type of disability on the experiences young adults with visual, hearing, or physical disability have with partnership and sexuality. Eighty-four participants aged 18–25 years, with hearing disability (n = 40), visual disability (n = 18), or physical disability (n = 26) were interviewed face-to-face or by phone. Nine out of ten participants had been in a relationship at least once. Seven out of ten had had experience with sexual intercourse. Female participants had more experience with sexual intercourse than male participants. Men had overall more relationships and experienced their first coitus significantly earlier. Participants with physical disability reported fewer relationships and their first sexual intercourse took place at a later age. The participants with hearing disability had the most relationships and experienced their first sexual intercourse earliest. The results of this study show that the study participants have significant experience with partnership and sexuality. On the other hand, the results indicate that an inclusive school system, the reinforcement of a positive self-perception, and supportive parents and educators are crucial for the development of young adults with impairments and their ability to make independent and confident decisions with regards to partnerships and sexuality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Due to many physical and psychosocial changes and challenges, adolescence is known to be an especially sensitive developmental period. A host of developmental tasks mark the transition between childhood and adulthood—finding one’s own identity, gaining emotional independence from one’s parents, and the start of intimate and romantic partnerships [1, 2].

Young adulthood is a phase in which the interest in partner relationships and sexual contacts is especially pronounced. Learning intimacy and starting and maintaining a stable relationship is a developmental task which continues into adulthood and is of central importance especially in the early adult years [3]. Even though romantic relationships in adolescent years tend to be shorter and less intimate than in adulthood, they encourage adolescents to think about who they are and who they want to be [4].

In addition to supporting identity development, adolescent romantic relationships also serve the important functions of affiliation, attachment, caregiving, and sexuality [5]. Matthiesen’s study shows that adolescent relationships are close and characterized by the ideal of romantic love. The partners quickly become the most important persons in all matters. Trust, openness and mutual understanding contribute to the cohesion of adolescent relationships [6]. Couple relationships are often the cause of strong positive (excitement, happiness) and strong negative feelings (jealousy, trouble, stress, lovesickness). Adolescents, especially girls, spend a lot of time reflecting on and talking about love relationships [7]. Romantic relationships in adolescence can have positive effects such as an improved self-esteem, an enhanced social status, as well as protection against social anxieties [8]. However, there are only a few studies that concentrate on the experiences of adolescents and their intimate and romantic relationships [9]. This issue is mostly dealt with within studies that focus on the topics of sexual behavior and sexual knowledge of young adults [10,11,12,13].

Even fewer surveys concentrate on the romantic and sexual relationships of persons with disability [14]. The few existing surveys are mainly limited to people with visual and physical disability or specific disease conditions such as spina bifida or paraplegia [15,16,17,18]. Further, studies typically investigate the sexual behavior or sexual knowledge of people with disability [11, 13, 19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26] and focus on the topic of partnership only marginally.

Language barriers complicate the inclusion of persons with visual and hearing disability from general population studies. Moreover, the lack of research may be associated with a generally fearful attitude towards partnership and sexuality with respect to people with disability; a view that dominated until the 1990’s. In particular, persons with physical disability were not perceived as sexual beings but as childlike and innocent [13, 27]. Due to the dominant inaccurate perspective and hostile social norms and attitudes towards sexuality and people with disability, it was assumed that their need for partnership and sexuality was abnormal. Contained in this view are prejudices regarding disability and sexuality—both that the people with disability are asexual or that they have an increased libido [25, 28, 29]. In recent years there has been some progress in redressing these false stereotypes. Ratified in Germany in 2009, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities identified sexual self-realization and self-determination as human rights [30]. Nevertheless, adolescents with hearing, visual and physical disability face particular challenges in the sensitive period of adolescence because the developmental tasks of adolescence are more difficult to realize due to their disability. For example, the acceptance of one’s own physical appearance, one’s own identity development, and the initiation of intimate relationships may be more difficult for those with disability [31].

Current State of Research

What can be learned from the results of international research with regard to different types of disability? A number of studies indicate that adolescents with physical disability have fewer partnerships [32,33,34] and are less sexually active than adolescents without disability [14]. The barriers and obstacles named by the respondents were the visibility of their disability and the resulting smaller range of potential (sexual) partners as well as a low sexual self-confidence [14, 32].

For adolescents with physical disability, it can be more difficult to accept their body because of negative body experiences in childhood. Further, the violation of their private sphere, stigmatization because of their disability, and overprotection and infantilization by their parents can create additional difficulties with sexuality and relationships. Female adolescents with physical disability who do not comply with current beauty ideals presented by the media are especially at risk and often experience their social environment as negative [31]. Girls with physical disability report low self-esteem more often than boys along with a more pronounced feeling of inferiority. They experience their disability as more burdensome than boys [35].

The few surveys reporting about the relationship behavior of young adults with visual disability came to the conclusion that they start their relationships at a later age [15, 21] because they have had to overcome greater barriers to enter a romantic partnership. For example, it is difficult to assess physical cues to assess potential interest such as making eye contact or judging facial expressions and gestures. A visual disability can be a crucial disadvantage especially in social contacts. Furthermore, the common public spaces such as discos and movie theatres are only partly accessible to people with visual disability because of their limited mobility [18]. Since they spend more time alone than adolescents without disability, they have fewer opportunities to get to know someone [36]. Moreover, the probability of adolescents with visual disability making a date with someone and starting a romantic relationship is altogether lower. Since they start partnerships later and less frequently, they have accordingly less sexual experience and are older than adolescents without disability when experiencing sex for the first time [15, 21]. People with visual disability often keep to themselves attending the same specialized schools and primarily establishing friendships with others with visual disability [15, 37]. Negative social attitudes, especially among teens who do not consider adolescents with visual disability as potential partners, contribute to this isolation. Overprotection from parents as well as feelings of insecurity and dependence are mentioned as further factors explaining the later and less frequent partnerships and sexual experiences [21, 22].

The data on relationships of people with hearing disability is also very limited. Among other things, this may be due to the fact that a hearing disability is not visually stigmatizing. In contrast to a visual or physical disability, hearing disabilities seem to advantage research interest. Young adults with hearing disability are more mobile and independent than young adults with visual and physical disability. They are able to initiate social contacts as well as romantic relationships independently and without transport service by their parents. Young adults with hearing disability tend to have significantly larger circles of friends. Their friends tend to also have a hearing disability due to the early institutionalization of children with hearing disability. The more pronounced the communication disability, the more they tend to withdraw into a deaf language community. They mostly look for romantic relationships within their own deaf peer group. Sign language is a body-related language, where touches and intensive body language are common patterns. This body related culture might favor a more open-minded handling of sexuality [14]. Heimann’s study concludes that the adult respondents with hearing disability had more sexual partners than the adult respondents without disability [38]. In another study, adolescents with hearing disability were sexual active at a later age than adolescents without disability. However, the adolescent respondents with and without disability both had a similar total number of partnerships [39].

The literature mentioned concentrates mainly on sexual issues and less on romantic relationships. There is hardly any information about the gathered experiences with partnership of young people with visual, hearing and physical disability. The following work, therefore, deals with partnership experiences in general (questions 1–4), sexuality (5–6) and wishes for the future (7) of young adults with disability. In particular, gender-specific differences, as well as possible differences regarding the type of disability, will be examined in this context. Specifically, the following questions will be answered:

-

1.

Altogether, how many steady relationships did the respondents have?

-

2.

How old were they when they first started a romantic relationship?

-

3.

How content are they with their current steady relationship?

-

4.

Are they looking for partners with disability?

-

5.

Have they experienced sexual intercourse and how old were they at that point?

-

6.

How content are they with their sexuality?

-

7.

Do they have the wish to marry and have children?

Methods

Procedure

The study, Family Planning for Young Adults with Disabilities, was conducted from 2012 to 2014. Data were collected from May 2013 to April 2014. The Ethical Review Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Leipzig gave its approval prior to data collection (AZ: 026-13-28012013). Participants were recruited mainly in vocational training centers in Dresden, Leipzig, and Chemnitz, Germany. The settings were sheltered workshops and residential homes for persons with disability, as well as in colleges and universities all over Saxony. Participation was voluntary and anonymous.

The participants could choose between a face-to-face interview on-site and a telephone interview. On-site interviews were conducted with 54 participants, in most cases within the rooms of the institution; and 30 interviews took place by telephone. There were no other persons present during the interviews. One exception was that interviews with the participants with hearing disability included a sign language interpreter to translate questions and answers. The interviews lasted on average one hour and the participants received a compensation of 20€. The male participants were interviewed preferably by a male project member; the female participants were interviewed preferably by a female project member.

Instrument

The questionnaire was adapted from the survey of the Federal Centre for Health Education to study youth sexuality. This survey is performed at regular intervals to examine the attitudes and behavior of adolescents in Germany towards sexuality and contraception [10]. Our adaptation included the addition of specific questions for people with disability. Providing a barrier-free questionnaire was of enormous importance for the survey. Face-to-face interviews provide the best barrier-free survey instrument for people with hearing, visual und physical disability. For example, young adults with visual disability can be interviewed verbally without additional aids, such as a computer or a Braille display. In so doing, it was also possible to carry out the interviews with the participants with physical disability without additional aids. Due to the barrier-free questionnaire, no participants with physical disability had to be excluded from the study.

The questionnaire was translated into a special form of writing called “easy to read”. This special style was created for persons with learning disabilities, but people with hearing disability also benefit from this simple sentence construction. The partly standardized questionnaire contained open and closed questions and was pilot tested for comprehension. The questionnaire was available in two versions, one for male (142 questions) and one for female participants (162 questions).

To measure aspects relating to partnership, the following questions were formulated regarding the topics partnership, sexuality, and future visions with their partners. The questions were as follows:

Partnership

-

“Are you currently involved in a steady relationship?” (response categories: “yes”, “no”, “no comment”);

-

“How many steady relationships have you had altogether, that lasted longer than 3 months (including the current relationship)?” (response categories: “__ relationships”, “no” and “no comment”);

-

“How old were you when you began your first steady relationship?“(response categories: “__ years”, “don’t know”, “no comment”);

-

“How satisfied are you with your current relationship in general?“(response categories: “highly satisfied”, “rather satisfied”, “neutral”, “not too satisfied”, “not satisfied at all”, “can’t tell”, “no comment”);

-

“Did your (ex-) girlfriend/boyfriend have a disability?”(response categories: “yes”, “no”, “don’t know”, “no comment”);

-

“Does your girlfriend/boyfriend/Did your (ex-) girlfriend/boyfriend have the same or another disability than you?“(response categories: “same disability”, “other disability”);

-

“I would like to ask you to remember the situation when you got to know your current girlfriend/boyfriend/your (ex-) girlfriend/boyfriend. Where and how was that? How did it happen that you became a couple? Please tell me about it.” (open question)

-

“In general terms: Is it easy or difficult for you to find a partner for a steady relationship? (Response categories: “easy”, “neutral”, “difficult”, “don’t know” und “no comment”);

-

“What makes it difficult for you to find a steady girlfriend/boyfriend?” (open question)

Sexuality

-

“There are different types of the intimacy between two persons. Have you ever done or experienced the following? (response categories: “sexual intercourse“: “yes”, “no”, “no comment”);

-

“How old were you when you first had sexual intercourse?”(response category: “__years”);

-

“Are/were you highly satisfied, rather satisfied, neutral, not too satisfied or not satisfied at all with the sexuality in your relationship?” (response categories: “highly satisfied”, “rather satisfied”, “neutral”, “not too satisfied”, “not satisfied at all”, “can’t tell”, “no comment”);

Wishes for the Future

-

“Do you wish to spend your whole life with your girlfriend/boyfriend? (response categories: “yes”, “no”, “undecided”, “don’t know”, “no comment”);

-

“Can you imagine marrying or living in a registered partnership?” (response categories: “yes”, “no”, “undecided”, “no comment”, “I’m already married/living in a registered partnership”);

-

“Can you imagine having children someday?”(response categories: “yes”, “rather yes” “rather no”, “no”, “I already have children”, “don’t know”, “no comment”).

Data Analysis

All statistical analyses were done on SPSS version 20.0. Descriptive statistics were use to describe the study population. Linear logistic regression analysis was performed to test the association of number of partnership with the following variables: age at survey, gender, sexual intercourse, search for a partner, age at beginning of the first relationship, and type of disability. The answers of the open questions were categorized inductively following Mayring [40].

Participants

Within the study, Family Planning for Young Adults with Disabilities in Saxony, 152 young adults aged 18–25 years with a physical, visual, hearing and learning disability, as well as mental and chronic illness, were interviewed. Here, we report only on the data of participants with visual, hearing and physical disability. More young adults with hearing disability (n = 40, 47.6%) than participants with visual (n = 18, 21.4%) and physical disability (n = 26, 31%) were reached (Table 1). Average age was 21.1 years. Three of the 44 female participants described their sexual orientation as homosexual and four as bisexual. Two of the 40 male participants defined their sexual orientation as bisexual.

Most of the participants were living in residential schools, followed by one-fifth living alone or with their parents. There were obvious gender differences: whereas more than one-third of male participants lived with their parents, only 4.5% of the female participants did so. More than half of the female participants lived at a residential school and almost one-third lived alone.

Results

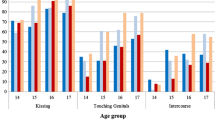

Table 2 presents the results of the total group, as well as the subgroups gender and type of disability regarding partnership, sexuality and visions for the future.

Partnership

The results show (Table 2) that the respondents entered 2.3 partnerships on average. The large majority (92.9%) had had at least one partnership. Overall, the male respondents have had more partnerships than the female respondents. In particular, young adults with physical disability (av. 1.85) have had fewer relationships than respondents with hearing (av. 2.28) and visual disability (av. 3.0). Between the participants with visual and physical disability, appears a significant difference in mean value (p = .038).

The average age at the start of the first partnership is 16.03 years. In this context, the male respondents met their first partners a little earlier (av. 15.94) than the female respondents (av. 16.1). The majority of the young adults reports being very happy in their current relationship (av. 1.26). Young adults with physical disability report being most content (av. 1.0) within their current relationship, in contrast to the respondents with hearing (av. 1.57) and visual disability (av. 1.17).

Both sexes most commonly met their partners in the context of school/vocational training and work (32.1%) or in their leisure time (28.6%). The young adults with visual disability (58.8%) in particular met their partners in the context of school/vocational training and work, in contrast to the respondents with physical (33.3%) and hearing disability (24.3%). All participants rarely used the internet for dating regardless of their sex or disability type.

More than half of the respondents had partners with a disability. The women had more often partners with disability (58.5%) than the male respondents (50%). Males were more likely to choose a partner with the same disability (83.3%) than the female respondents (58.3%). Furthermore, the young adults with visual disability were most often in a relationship with a partner with disability (64.7%). These partners had significantly more often the same disability (90.9%) than respondents with hearing (75%) and physical disability (36.4%).

The majority of the study participants described their search for a partner as being difficult (68.8%). In particular, female interviewees (73.2%) evaluated their search for a partner as more difficult than the male participants (64.1%). Further, young adults with physical disability indicated problems in getting to know a partner (70.8%). The majority of the participants stated the following reasons for their difficulties finding a partner: their own personal characteristicsFootnote 1 (28.6%), their own disability (19%), their expectationsFootnote 2 (15.5%) and basic conditionsFootnote 3 (7%). The respondents with physical disability (40.9%) suggested significantly more often their own disability as the reason for problems finding a partner, whereas the participants with hearing (48%) and visual disability (38.5%) most often cited their personal characteristics.

Sexuality

Two-fifths of the surveyed women (79.5%) and two-thirds of the male participants (62.5%) had already had sexual intercourse. The average age at the first sexual intercourse was 16.4 years. The male participants experienced their first time significantly earlier compared to the surveyed young women (15.48 vs. 17.15, p = .009). Furthermore, the young adults with a physical disability (av. 17.50) had their first sexual intercourse considerably later than the respondents with a hearing disability (av. 15.81). In addition, the female participants (av. 1.57) reported being more content with their current relationship than the male respondents (av. 1.95). In particular, the participants with a visual disability (av. 1.55) attested to being more content with their current relationship than the young adults with a hearing (av. 1.78) or a physical disability (1.73).

Wishes for the Future

The large majority of participants plan to stay together with their current partner for their whole lives. No one indicated that their current partnership is not a long-term relationship. Moreover, almost four-fifths could imagine marrying 1 day. No differences were noticeable among the sexes and types of disability regarding the desire to marry. The female and male respondents also have a similar strong desire to have children (86.4% vs. 87.5%). Only the participants with physical disability (76.9%) expressed a lesser wish to have children in comparison with the respondents with hearing (90%) and visual disability (94.4%).

Number of Partnerships

The vast majority of the respondents had already had experience with partnership at the time of the interview. To examine which variables were determinant for the number of relationships, a regression analysis was employed. The variables sex, age, sexual intercourse, the search for a partner, age at the beginning of the first relationship, as well as the variables visual and physical disability were included in the regression model. Hearing disability was later excluded because it did not contribute to the variance explanation (Table 3).

As expected, the number of relationships increases with the age of the respondents. The participants with sexual experience reported a significantly higher number of relationships. Furthermore, the respondents who enter their first partnership in an early age show altogether a higher number of relationships. The participants with a visual disability have a larger number of partnerships. The variable physical disability indicated the opposite effect—respondents with a physical disability reported far fewer partnerships than respondents with a visual disability.

Discussion

Study results point out that young adults with hearing, visual and physical disability are clearly experienced with aspects of partnership and sexuality. Particularly female respondents are more likely to have a current relationship. Scientific literature has described the opposite—that females have a harder time finding relationships than their male peers [31, 35]. One can assume that this new generation of female respondents is equipped with a more positive self-image and is, therefore able to enter relationships with more confidence. This generational change among women with disability was previously described in a study by Eiermann [41]. That study proposed that today’s young women have been raised to be more independent and confident, than older generations. The results of our study seem to reflect the progress of this development.

In line with this development, female respondents live more often in an independent housing situation than male respondents and had clearly gained more experience with sexual intercourse. The male participants, however, first experienced sexual intercourse at a significantly younger age than their female peers. An earlier study, Youth Sexuality and Disability, similarly concluded that boys are sexually active earlier than girls [14]. Scientific literature reports early sexual activity as occurring within the context of a negative body image. Young adults with disability often do not meet established beauty ideals. This can make their development of a positive self-image more difficult. Therefore, they often have greater difficulty developing a healthy body image than persons without disability [42]. Some of the respondents seem to compensate negative body images with early sexual activity, whereas the others have remained abstinent.

The female respondents consider the search for a partner to be more difficult than the male respondents. The reason cited for this is that they are generally more reserved in finding a partner, stating timidity and difficulties building trust as the main obstacles. Furthermore, they have a high ideal of partnership and criticize the limited selection of potential partners. In their main meeting places, they primary meet other persons with (similar) disability. The range of potential relationship partners is, thereby, regulated [14].

The female interviewees also described feeling that their appearance and capacity were less than that of women without disability. This thinking suggests a negative body image. In particular, women are more susceptible to beauty ideals with regards to sexuality than men and are more harshly judged in terms of physical beauty and attractiveness. The concept of one’s own attractiveness is composed of self-observation and social feedback. With disabilities that are visible, rejection from the social environment creates feelings of insecurity and hinders a positive identity development. As such, people with disability, in particular women with visible disability, are less likely to attract partners because social expectations of beauty play an important role during partner search [31, 43].

Nevertheless, female interviewees were more likely to have relationships with partners without disability as compared to male respondents. Choosing a partner with disability can be connected with the need to feel accepted and understood. This desire for recognition seems to be somewhat stronger among men. They are more often in relationships with partners with the same disability; whereas the women interviewed were more often in relationships with partners with a different disability, if their partners had a disability at all.

Furthermore, young adults with visual or hearing disability pick significantly more often partners with a similar disability, whereas young adults with physical disability tended to choose a partner with a different disability. This difference may be due to the fact that children and adolescents with visual disability are institutionalized early. There are only two schools for blind and partially sighted children and only three schools for children with hearing disability in Saxony. Students are usually accommodated in residential schools because the distance from their parental home is often too large. Literature shows that individuals with visual disability [15, 18, 21] often have smaller social networks, show higher levels of depressive symptoms and loneliness, and have to overcome greater barriers connecting with the outside world. Further, they cannot rely the same flirting and dating methods as sighted persons. These reasons combined with the lack of inclusion in the Saxon school system could lead to people with visual disability meeting their partners primarily inside their specialized meeting places (special schools, vocational training center), where they largely meet peers with visual disability. In accordance with this assumption, the study participants with visual disability mostly stated that they met their partners in a school or vocational setting rather than during social activities, as was case in the comparison groups. Furthermore, one can assume that they want support and understanding within a partnership, which they would most likely find with a partner with the same disability.

Young adults with physical disability have a better chance of going to regular schools according to their functional impairment level and depending on the accessibility of their responsible school. One can assumed that they choose partners without the same disability for pragmatic reasons. The wish for a supporting partner with a moderate or no disability can be present especially when individuals have a severe functional restriction, for instance paraplegia.

Contrary to the mentioned obstacles and results of the cited literature, the study participants with visual disability had the highest number of partnerships. This suggests that they might have less fear of initiating contact and might have methods different from those of sighted people to signal interest in each other. Furthermore, literature shows that young adults with visual disability do not judge physical attractiveness to be as important as sighted persons do. Emotional maturity and the inner values of their partners are more important to them [15]. These factors seem to facilitate and increase the probability of starting and ending relationships, since the results of this research group indicate that these relationships break up more often.

The respondents with hearing disability tend to see their partner search difficulties only marginally influenced by their disability. As has already been described in literature, medical-technological progress has greatly altered the way younger persons with hearing disability approach the hearing culture and vice versa [14]. The number of deaf people who can communicate orally continues to grow, as more and more young people get cochlear implants to improve their hearing [44]. Furthermore, although they had sexual intercourse earlier, they were more discontent with the sex in their relationship than the comparison groups. Their early and numerous experiences with relationships and sexuality could be connected to the body-related culture of the sign language community, perhaps leading to a more open treatment of sexuality. Further explanations include unrestricted mobility, their early institutionalization and their large friend network already described in literature [14]. Finally, a hearing disability is less stigmatizing than visual or physical disabilities, as it is not visible.

The young adults with physical disability have less relationship experience and are sexually active later as compared to the other groups. They also evaluate their search for a partner as more difficult and name their disability as the main reason. This result is consistent with current research findings [14, 32,33,34,35] that explain that stigmatization creates obstacles to form sexual relationships for individuals with visible physical disabilities. People with physical disability are more stigmatized than individuals with sensory disabilities. This stigmatization can lead to a lack of acceptance of one’s own body and a low (sexual) self-confidence and, in addition, can have a negative influence on attitudes towards partnership and sexuality [31]. On the other hand, respondents with physical disability reported being significantly more content with their current relationship than study participants with sensory disabilities. They seem to appreciate the few relationships they have more, perhaps because they have more difficulty finding a partner than respondents with sensory disabilities. Interestingly, the study participants with physical disability have less desire to have children than the comparison groups. This could be explained by stigmatization in combination with the societal misconception that people with physical disability will pass on their disability. This stigmatizing attitude could have a negative influence on the wish to have children [45]. Another reason could be the poorer physical constitution of persons with physical disability, which could influence their confidence regarding the ability to support a child and the relating to tasks dependent on their specific functional disability.

The common strongly held desire of all respondents for a long-term partnership or marriage points to the fact that they have a strong relationship orientation; they all look forward to a happy and permanent relationship in the future.

Practical Implications

Inclusive school systems create the conditions in which children and adolescents with and without disability can come in contact with each other at an early age. In this context, prejudices and discrimination towards people with disabilities are less likely to arise. In inclusive systems, children and adolescents with disability have the opportunity to familiarize themselves with the interests and needs of students without disability. Further, students without disability are able to dismantle their fears of persons with disability and they can potentially form friendships or romantic relationships. However, high-quality, inclusive school systems require substantial financial and human resources. Universal access, teacher qualifications, and barrier-free admissions are key points in serving students with disability.

Moreover, young people with disability, especially physical disability, need support in forming a positive self-image, a prerequisite for entering a healthy relationship. Here, social workers, psychologists, teachers and parents should be sensitized. Furthermore, women should be encouraged to question social beauty norms and to view themselves as confident and independent. Positive public role models could support this progress.

Literature describes young people with visual and physical disability as spending more time at home with family than spending time with friends [15, 21, 32]. However, social interactions are elementary meeting peers and entering relationships. Therefore, it is of great importance that young people with disability are encouraged by sensitive parents and teachers to participate in leisure activities. To this end, barrier-free meeting places are necessary.

Adolescents with disability perceive their parents as being overprotective. Their parents often forego or delay appropriate sex education out of the fear that their children could have negative sexual experience [21, 22, 32]. This prevents an open and positive exchange about partnership and sexuality, and impedes sexual self-determination for these adolescents. Parents should be encouraged to give their children sex education early enough to strengthen their self-confidence. Furthermore, sex education in school is of particular importance. To have sex educators with disability providing information and accessible materials would be especially effective.

Overall, there is a lack of scientific data, especially representative studies, reporting on how people with disability experience romantic and sexual relationships. This study took a step in this direction by gathering the first scientific data on the subject partnership and sexuality. A follow-up study on the issue sexuality and partnership in young adults with cognitive disability is currently being carried out. Hope remains that both studies will lay the foundation for further scientific research in this thematic area. Further, the Federal Center for Health Education plans to develop new sexual educational materials for people with disability based on these research results.

Conclusion and Limitations

Study results show that young adults with visual, hearing and physical disability are already quite experienced with relationships and sexuality. However, there is some divergence between the sexes and the types of disability. For the vast majority, a long-term relationship is of great importance. Societal attitudes towards the topics of partnership and sexuality regarding people with disability have changed and it was recognized that the biggest impediment to opportunities and personal development that people with disability face is their restricted living conditions due to lack of accessibility, not the limitations of their functional impairment. Barriers exclude people and repress them in everyday life. The incorrect attitudes of the past are still influencing the present, but due to the improved legal rights afforded by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disability and because the taboos have relaxed regarding the topic partnership and sexuality, a sexually tolerant future can become reality for people with disability.

Some limitations of this study deserve mention. This study mainly included young adults from vocational training centers (n = 69) and sheltered workshops for people with disability (n = 8). Only seven respondents were university students. A balanced number of study participants from inclusive and non-inclusive educational institutions would have been more desirable. However, the majority of young adults with disability in Germany complete their vocational training at vocational training centers or sheltered workshops for people with disability [46]. Furthermore, a higher sample number would have been preferable to better compare the individual disability types on the issue of relationship and sexuality. For this purpose, a national study would have been necessary, because the number of people with the mentioned disabilities within the observed age group is less than 1% of all people with recognized severe disability in Saxony [47]. Furthermore, due to the small size of the sample, it was not possible to analyze the partnership experience with regard to social background or the time of the occurrence of the disability (to show possible socialization effects). Additionally, a data comparison among young adults with and without disability would have been interesting. Unfortunately, there is currently no comparable published German study for young adults without disability between 18–25 years with results concerning the research questions.

Notes

The category ‘personal characteristics’ summarizes the statements of the respondents about their obstructive personality traits when searching for a partner such as “my shyness” or “insecurity”.

The category ‘expectations ‘summarizes the statements of the respondents about their obstructive expectations when searching for a partner such as “high demands” or “precise ideas of a partner”.

The category ‘basic conditions ‘summarizes the statements of the respondents about obstructive conditions when searching for a partner such as “lack of opportunity” or “lack of choice”.

References

Havighurst, R.J.: Developmental Tasks and Education. Mc Kay, New York (1972)

Dreher, E., Dreher, M.: Entwicklungsaufgaben im Jugendalter. In: Liepmann, D., Stiksrud, A. (eds.) Entwicklungsaufgaben und Bewältigungsprobleme in der Adoleszenz, pp. 56–70. Hogrefe, Göttingen (1985)

Richards, M.H., Crowe, P.A., Larson, R., Swarr, A.: Developmental patterns and gender differences in the child experiences of peer companionship during adolescence. Child Dev. 69(1), 154–163 (1998)

Furman, W., Shaffer, L.: The role of romantic relationships in adolescent development. In: Florsheim, Paul (ed.) Adolescent Romantic Relations and Sexual Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practical Implications, pp. 3–22. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, Mahwah (2003)

Furman, W., Wehner, E.A.: Romantic views: toward a theory of adolescent romantic relationships. In: Montemayer, R., Adams, G.M., Gulotta, C.T. (eds.) Personal Relationships During Adolescence, pp. 168–195. Sage, Thousand Oaks (1994)

Federal Centre for Health Education.: Youth Sexuality in the Internet Age: A Qualitative Study of the Social and Sexual Relationships of young people. https://www.forschung.sexualaufklaerung.de/fileadmin/fileadmin-forschung/pdf/BZgA_Youth%20Sexuality%20in%20the%20Internet%20Age_Schutz.pdf (2013). Accessed 27 Jan 2017

Larson, R.W., Clore, G.L., Wood, G.A.: The emotions of romantic relationships. Do they wreak havoc on adolescents? In: Furman, W., Bradford Brown, B., Feiring, C. (eds.) The Development of Romantic Relationships in Adolecence, pp. 19–49. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1999)

Joyner, K., Urdy, J.R.: You don’t bring me anything but down: adolescent romance and depression. J. Health. Soc. Behav. 41(4), 369–391 (2000)

Brown, B.B., Feining, C., Furman, W.: Missing the love boat: why researchers have shied away from adolescence romance. In: Furman, W., Brown, B.B., Feinberg, C. (eds.) The Development of Romantic Relationships in Adolescence, pp. 1–16. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1999)

Heßling, A., Bode, H.: Jugendsexualität 2015. Die Perspektive der 14- bis 25- Jährigen. Ergebnisse einer aktuellen repräsentativen Wiederholungsbefragung. The Federal Centre for Health Education, Köln (2015)

Shandra, C.L., Chowdhury, A.R.: The first sexual experience among adolescent girls with and without disabilities. J. Youth Adolesc. 41(4), 515–532 (2012)

Scharf, M., Mayseless, O.: The capacity for romantic intimacy: exploring the contribution of best friend and marital and parental relationships. J. Adolesc. 24, 379–399 (2001)

Suris, J.C., Resnick, M.D., Cassuto, N., Blum, R.W.: Sexual behavior of adolescents with chronic disease and disability. Sex. Disabil. 19(2), 124–131 (1996)

The Federal Centre for Health Education (BZgA).: Youth Sexuality and Disability: Results from a Survey Carried Out at Special-Needs Schools in Saxony. Cologne (2013)

Pinquart, M., Pfeiffer, J.: What is essential is invisible to the eye: intimate relationships of adolescents with visual impairment. Sex. Disabil. 30(2), 139–147 (2012)

Wiegerink, D.J., Stain, H.J., Gorter, J.W., Cohen-Kettenis, P.T., Roebroeck, M.E.: Development of romantic relationships and sexual activity in young adults with cerebral palsy: a longitudinal study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 91(9), 1423–1428 (2010)

Verhoef, M., Barf, H.A., Vroege, J.A., Post, M.W., van Asbeck, F.W., Gooskens, R.H., Prevo, A.J.: Sex education, relationships, and sexuality in young adults with spina bifada. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 86(5), 979–987 (2005)

Hicks, S.: Relationship and sexual problems of the visually handicapped. Sex. Disabil. 3(3), 165–176 (1980)

Wienholz, S., Seidel, A., Schiller, C., Michel, M., Häußler-Sczepan, M., Riedel-Heller, S.G.: Sexuelle Bildung und Koitusaktivität bei Jugendlichen mit und ohne Behinderung. Z. Sexualforsch. 26(3), 232–244 (2013)

Bezerra, C.P., Pagliuca, L.M.: The experience of sexuality by visually impaired adolescents. Rev. Esc. Enferm. 44(4), 578–583 (2010)

Kef, S., Bos, H.: Is love blind? Sexual behavior and psychological adjustment of adolescents with blindness. Sex. Disabil. 24(2), 89–100 (2006)

Gordon, P.A., Tschopp, M.K., Feldman, D.: Addressing issues of sexuality with adolescents with disabilities. Child Adolesc. Social Work J. 21(5), 513–527 (2004)

McCabe, M.P., Taleporos, G.B.A., Dip, G.: Sexual Self Esteem, Sexual Satisfaction, and Sexual Behavior among People with Physical Disability. Arch. Sex. Behav. 32(4), 359–369 (2003)

Neufeld, J., Klingbeil, F., Bryen, D.N., Silverman, B., Thomas, A.: Adolescent sexuality and disability. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 13(4), 857–873 (2002)

Berman, H., Harris, D., Enright, R., Gilpin, M., Cathers, T., Bukovy, G.: Sexuality and the adolescent with a physical disability: understandings and misunderstandings. Issues Compr. Pediatr. Nurs. 22(4), 183–196 (1999)

Seidel, A., Wienholz, S., Michel, M., Luppa, M., Riedel-Heller, S.G.: Sexual knowledge among adolescents with physical handicaps: a systematic review. Sex. Disabil. 31(3), 429–441 (2014)

Stevens, S.E., Steele, C.A., Jutai, J.W., Kalnins, I.V., Bortolussi, J.A., Biggar, W.D.: Adolescents with physical disabilities: some psychosocial aspects of health. J. Adolesc. Health 19(2), 157–164 (1996)

Specht, R.: Sexualität und Behinderung. In: Schmidt, R.-B., Sielert, U. (eds.) Handbuch Sexualpädagogik und sexuelle Bildung, pp. 288–300. Beltz Juventa, Weinheim, Basel (2008)

Alemu, T., Fantahun, M.: Sexual and reproductive health status and related problems of young people with disabilities in selected associations of people with disabilities, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop. Med. J. 49(2), 97–108 (2011)

United Nations.: Final report of the Ad Hoc Committee on a comprehensive and integral international convention on the protection and promotion of the rights and dignity of persons with disabilities. http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/rights/ahcfinalrepe.htm (2006). Accessed 16 June 2016

Ortland, B.: Behinderung und Sexualität—Grundlagen einer behinderungsspezifischen Sexualpädagogik. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart (2008)

Wiegerink, D., Roebroeck, M., Donkervoort, M., Stam, H., Cohen-Kettenis, P.: Social and sexual relationships of adolescents and young adults with cerebral palsy: a review. Clin. Rehabil. 20(12), 1023–1031 (2006)

Rintala, D.H., Howland, C.A., Nosek, M.A., Bennett, J.L., Young, M.E., Foley, C.C., Rossi, C.D., Chanpong, G.: Dating Issues for women with physical disabilities. Sex. Disabil. 15(4), 219–242 (1997)

Blum, R.W., Resnick, M.D., Nelson, R., Germaine, A.S.: Family and peer issues among adolescents with spina bifada and cerebral palsy. Pediatrics 88(2), 280–285 (1991)

Dechesne, B.: Die psychosexuelle Entwicklung bei körperbehinderten Jugendlichen. In: Dechesne, B., Pons, C., Schellen, T. (eds.) …aber nicht aus Stein. Medizinische und psychologische Aspekte von körperlicher Behinderung und Sexualität. Beltz, Weinheim, Basel (1981)

Huurre, T.M., Aro, H.M.: Psychosocial development among adolescents with visual impairment. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 7(2), 73–78 (1998)

Sacks, S.Z., Wolffe, K.T., Tierney, D.: Lifestyles of adolescents with visual impairments: an ethnographic analysis. J. Vis. Impair. Blind. 92(1), 7–17 (1998)

Heiman, E., Haynes, S., McKee, M.: Sexual health behavior of Deaf American Sign Language (ASL) users. Disabil. Health J. 8(4), 579–585 (2015)

Sangowawa, A.O., Owoaje, E.T., Faseru, B., Ebong, I.P., Adekunle, B.J.: Sexual practices of deaf and hearing secondary school students in Ibadan. Nigeria. Ann. Lb. Postgrad. Med. 7(1), 26–30 (2009)

Mayring, P.: Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken. Beltz, Weinheim (2015)

Eiermann, H., Häußler, M., Helfferich, C.: Live, Leben und Interessen vertreten—Frauen mit Behinderung. Lebenssituation, Bedarfslagen und Interessenvertretung von Frauen mit Körper- und Sinnesbehinderungen. Schriftenreihe, Band 183. Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend (Hrsg.). Kohlhammer, Stuttgart (2000)

Wienholz, S.: Sexual experiences of adolescents with and without disabilities: results from a cross-sectional study. Sex. Disabil. 34(2), 171–182 (2016)

Radtke, D.: Unsere Normalität ist anders—Behinderte Frauen und Sexualität. In: Färber, H.-P., Lipps, W., Seyfarth, T. (eds.) Sexualität und Behinderung—Umgang mit einem Tabu, pp. 104–111. Attmpto, Tübingen (1998)

Gräfen, C.: Die soziale Situation integriert beschulter Kinder und Jugendlicher mit Hörschädigung an der allgemeinen Schule. Verlag Dr. Kovac, Hamburg (2015)

Sheppard-Jones, K., Kleinert, H., Paulding, C., Espinosa, C.: Family Planning for adolescents and young women with disabilities: a primer for practioners. Int. J. Disabil. Hum. Dev. 7(3), 343–348 (2008)

Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF).: Berufsbildungsbericht 2016. https://www.bmbf.de/pub/Berufsbildungsbericht_2016.pdf (2016). Accessed 22 Sept 16

Landesamt für Statistik Sachsen: Schwerbehinderte Menschen am 31.Dezember 2011. http://www.statistik.sachsen.de (2014). Accessed 18 Oct 15

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by the Federal Centre for Health Education (Project Number 4.11/4.12).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with ethical standards of institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Retznik, L., Wienholz, S., Seidel, A. et al. Relationship Status: Single? Young Adults with Visual, Hearing, or Physical Disability and Their Experiences with Partnership and Sexuality. Sex Disabil 35, 415–432 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-017-9497-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-017-9497-5