Abstract

This paper investigates the interplay among three main elements of an entrepreneurial ecosystem: local universities, local financial system, and residents’ individual attitudes. Specifically, we study how the local availability of university knowledge interacts with the relative presence of cooperative banks in the local banking industry and with the residents’ tendency to behave opportunistically to determine the creation of high-tech ventures in a territory (i.e., Italian provinces). Our insight is that high information asymmetries impede high-tech entrepreneurial ideas based on university knowledge to attract external finance. Cooperative banks, which have trust-based relationships with the local community, are potentially a valuable source of finance for these entrepreneurial ideas, but are restrained by their inherent risk aversion. Accordingly, we argue that university knowledge and local presence of cooperative banks can interact either positively or negatively in determining the creation of high-tech ventures at the local level. We also contend that residents’ individual attitudes shape this interaction as trust-based relationships are more valuable in areas where residents tend to behave opportunistically. In the empirical part of the paper, we estimate zero-inflated negative binomial regressions where the dependent variable is the number of new high-tech ventures established in 792 province-industry pairs in the period 2012–2014. In line with our reasoning, we find that in provinces where residents tend to behave opportunistically, the relative presence of cooperative banks magnifies the positive effect of university knowledge on high-tech entrepreneurship. Conversely, this effect is negligible in provinces with less opportunistic residents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Scholars agree that entrepreneurial ecosystems consist in a set of interdependent elements (i.e., actors and factors) coordinated for enabling productive entrepreneurship within a geographical area (Stam and Spigel 2016). To date, researchers in this field have mainly engaged in identifying these elements—which include local universities, financiers, customers, infrastructures, supporting organizations, regulatory frameworks, and individuals’ cultures and attitudes (see Acs et al. 2017; Brown and Mason 2017; Spigel 2017; for recent reviews of this literature). Conversely, the issue of how these elements interact has comparatively received less attention and has been addressed mainly through qualitative methodologies, which limit generalizability (e.g., Qian and Yao 2017). This is a relevant gap. The concept of ecosystem roots in the interdependency of its constitutive elements, which reinforce and support each other. Investigating their interactions is thus crucial to fully comprehend how ecosystems nurture the creation and growth of new ventures in a geographical area (Alvedalen and Boschma 2017; Acs et al. 2014).

Using quantitative data on the Italian context, this paper makes a step in this direction by exploring how local universities, local financial system, and residents’ individual attitudes interact to determine the creation of new high-tech ventures in a geographical area. In modern entrepreneurial ecosystems, these three crucial elements encompass many dimensions (see e.g., Auerswald and Dani 2017; Cohen 2006; Isenberg 2010, 2011; Brown and Mason 2014; Qian and Yao 2017; Spigel 2017; Stam 2015), whose relevance depends (also) on the context of the study. Therefore, in formulating our research questions, we focus on specific dimensions of each element, which are highly salient for the creation of high-tech ventures in the Italian context and, as we discuss in the concluding section, in contexts similar to the Italian one. Moreover, the chosen dimensions, being measurable and sizable, are usable in a quantitative analysis. Specifically, our research questions are as follows. How does local university knowledge interact with the relative presence of cooperative banks to determine the creation of new high-tech ventures in a geographical area? How does residents’ tendency to behave opportunistically influence this interaction?

Our focus on local availability of university knowledge (as measured by the local presence of university personnel specialized in the fields of sciences that are relevant for the industry of operation of the new venture, see Section 3.2) aligns with the Knowledge Spillover Theory of Entrepreneurship (KSTE), (Acs et al. 2009; Ghio et al. 2015). According to this theory, university knowledge is a crucial determinant of the creation of high-tech ventures in a geographical area (Audretsch and Lehmann 2005; Baptista and Mendonça 2010; Fritsch and Aamoucke 2013; Bonaccorsi et al. 2013; Bonaccorsi et al. 2014). We recognize that our decision to pinpoint cooperative banks (i.e., the share of local bank branches of cooperative banks over total bank branches in an area, e.g., Deloof and La Rocca 2015) as a key dimension of the local financial system may sound weird. Contributions on entrepreneurial ecosystems concur with the entrepreneurial finance literatureFootnote 1 in recognizing venture capitalists as the main investors specialized in financing high-tech venturesFootnote 2 (Gompers and Lerner 2001). However, amidst few new ventures attract venture capital financing (Guerini and Quas 2016), the venture capital market is still underdeveloped in Italy (Bertoni et al. 2015; EVCA 2015; Kelly 2011), venture capital firms cluster around the metropolitan area of Milan and are almost absent in other territories. Banks are instead the primary source of external finance in Italy (Minetti and Zhu 2011). The country has one of the largest—regarding assets (Angelini and Cetorelli 2003)—and most heterogeneous—regarding firms’ size and ownership (Usai and Vannini 2005; Ferri et al. 2014)—banking industry in Europe. Cooperating banks are central in this industry. They have a widespread geographical diffusion and are strongly connected with local communities of entrepreneurs and other relevant stakeholders (Usai and Vannini 2005).Footnote 3 Thus, it comes with no surprise that cooperative banks play a significant role in the financing of new ventures, including those operating in highly innovative industries (Riciola and Furlò 2016). Finally, literature notes that that residents’ attidutes matter in entrepreneurial ecosystems (Alvedalen and Boschma 2017). Being more or less germane to entrepreneurship, these attidutes lead to different rates and types of entrepreneurial activities across territories (Gertler 2010). Thus, we argue that they also interact with the other ecosystem elements and, in line with our framework, we explore the effects of residents’ tendency to behave opportunistically. Indeed, as we clarify in the following, our insight is that university knowledge and local presence of cooperative banks can interact either positively or negatively in determining the creation of new high-tech ventures in a geographical area. On the one hand, cooperative banks have superior abilities to cope with the high information asymmetries (Howorth and Moro 2006; Ayadi et al. 2010; Ferri et al. 2014)—both in terms of evaluating business ideas and monitoring entrepreneurs—which impede local prospective entrepreneurs who intend to do business out of university knowledge to attract the external finance (trust-building effect). On the other hand, these banks may have a low propensity to invest in high-tech businesses based on university knowledge because they are risk adverse (Fonteyne 2007; Hesse and Cihak 2007) and have limited resources and competences to judge complex innovative projects (risk-aversion effect). Along this line of reasoning, we argue that the trust-building effect is particularly important in areas where monitoring is costly as individuals tend to behave opportunistically. Therefore, we conclude that this residents’ individual attitude shapes the interaction between local availability of university knowledge and local presence of cooperative banks.

In the empirical part of the paper, we run a series of zero-inflated negative binomial regressions where the dependent variable is the number of new high-tech ventures established in 792 province/industry pairs in the period 2012–2014. We first empirically assess whether the relative presence of cooperative banks in an entrepreneurial ecosystem moderates the (alleged positive) effect of university knowledge on the number of new high-tech ventures created in a province/industry. Then, we investigate whether this moderating effect depends on the residents’ tendency to behave opportunistically. We find that the presence of cooperative banks positively interacts with university knowledge, thus facilitating the conversion of university knowledge into new high-tech firms. This result supports the view that the trust-building effect of local cooperatives dominates their risk-aversion effect. Furthermore, in line with our expectations, the econometric models show that this effect is strong in provinces where the residents tend to behave opportunistically, while it is absent in provinces where opportunism is low.

The paper proceeds as follows. In the next session, we develop our research hypotheses. Section 3 describes the econometric models used to test these hypotheses, data sources, and variables. In Section 4, we discuss the results from the econometric estimations, while in Section 5 we present a series of robustness checks for our results. Section 6 concludes the paper by summarizing its main findings, acknowledging its limitations and sketching directions for future research.

2 Research hypotheses

Studies in the stream of KSTE suggest the existence of a positive relation between local availability of university knowledge and high-tech entrepreneurship in a geographical area. Indeed, the central tenant of this theory is that knowledge generated by local universities spills over from its sources across territories and creates opportunities, which local prospective entrepreneurs can leverage for setting up new high-tech ventures (a review of this literature is in Ghio et al. 2015). However, transforming these opportunities into new ventures requires a wide array of resources, not the least of which is external finance (Shane and Venkataraman 2000). As we mentioned in the introduction, cooperative banks, which have a natural bent to finance local economic activities and mainly invest in proximate firms and entrepreneurial projects (Ferri et al. 2014), have both advantages and disadvantages in providing this external finance. Therefore, their local presence can either positively or negatively interact with the local availability of university knowledge to determine the creation of new high-tech ventures firms in a geographical area.

We argue that a positive interaction between university knowledge and cooperative banks may result from what we call the trust-building effect. As we explain in the following, cooperative banks have superior abilities to cope with the information asymmetries associated to university-based entrepreneurial projects. Thus, these banks have potentially a high propensity to finance prospective entrepreneurs who intend to create new ventures out of university knowledge to the extent that their presence in a territory magnifies the effect of the local availability of university knowledge on local high-tech entrepreneurship.

In case of high-tech entrepreneurial projects based on university knowledge, the evaluation of the business quality and the monitoring of prospective entrepreneurs turn out to be particularly difficult. First, the nature of university knowledge exacerbates the difficulties that outsiders—including external financiers—experience in gauging the (future) economic prospects of high-tech businesses (see e.g., Carpenter and Petersen 2002; Colombo et al. 2013; Schneider and Veugelers 2010).Footnote 4 The potential commercial value of university knowledge, which is not created for commercial purposes, is indeed hard to assess for non-scientists (Audretsch and Stephan 1999). Second, and (partially) related to the previous point, the conversion of university knowledge into marketable products and services is a long and highly uncertain process (Fontes 2005; Stephan 2012). This poses severe moral hazard problems (Lerner 1995) as it hard for external financiers to monitor ex-post the efforts that entrepreneurs put in developing their university-based business or their willingness to orient it into riskier directions.

In this framework, we contend that the lending approach commonly adopted by cooperative banks—i.e., relational lending (Berger and Udell 2002)—proves to be more effective than the traditional transaction-based lending (typical of large, non-local, commercial banks) in making financial decisions about local prospective entrepreneurs, who want to transform university knowledge into new high-tech ventures. In relational lending, cooperative bank managers can come to positive decisions about the requests for credit of these local prospective entrepreneurs even in absence of collateralizable assets and positive credit scores, which are needed when requests for financing are evaluated through transaction-based lending. Indeed, in relational-lending, bank managers assess the reliability of prospective entrepreneurs and the quality of their business idea by collecting soft information thank to their embeddedness into local communities (Usai and Vannini 2005). In so doing, they achieve a superior ability to evaluate and monitor entrepreneurial projects. First, when faced with the need to evaluate an entrepreneurial idea based on university knowledge, cooperative bank managers engage in intense face-to-face interactions not only with the local entrepreneur searching for finance but also with other key informants. For instance, bank managers can (informally) ask for advices to academic researchers of local universities or to other local technology specialists. These social contacts provide valuable information about the future prospects of the entrepreneurial project. Second, cooperative bank managers’ embeddedness into the local community lowers the costs of monitoring in comparison with commercial banks as the strong network of local connections of cooperative bank managers acts as disciplinary device for local prospective entrepreneurs. Indeed, in case of opportunistic behaviors, bank managers can not only give a negative feedback to their bank, but they can also spread their negative judgment among their contacts in local community (e.g., other investors, potential customers, or other local entrepreneurs), thus causing a bad reputation to opportunistic entrepreneurs. In turn, such a bad reputation becomes a serious obstacle to the obtainment of future funding (Howorth and Moro 2006), ultimately excluding entrepreneurs who behave opportunistically from the local credit market. In sum, through relational-lending, cooperative banks can achieve a better judgment of business opportunities developed out of university knowledge and build and reinforce trust in local prospective entrepreneurs, who intend to enact these opportunities by creating new high-tech ventures.

In line with arguments on the trust-building effect, we expect that the presence of cooperative banks in local entrepreneurial ecosystems positively interacts with university knowledge in determining high-tech entrepreneurship in a geographical area. Hypothesis H1a follows:

-

H1a: The relative presence of cooperative banks in the local entrepreneurial ecosystem strengthens the (allegedly) positive relation between local university knowledge and the creation of high-tech ventures in a geographical area.

Conversely, a negative interaction between university knowledge and cooperative banks may result from what we call the risk-aversion effect. Extant literature documents that cooperative banks are typically risk-averse, while being at shortage of resources and competencies (e.g., Ayadi et al. 2010; Ferri et al. 2014). These two features may negatively influence their willingness and ability to finance local prospective entrepreneurs who intend to create high-tech ventures out of university knowledge. First, in comparison with commercial banks, cooperative banks are more interested to maximize the value of their long-term relationship with their customers, being instead less prone to maximize their short-term profits. Accordingly, as available empirical evidence suggests, cooperative banks follow safer lending strategies (Rasmusen 1988), which generate lower loan losses (Cesarini et al. 1996; Fonteyne 2007), lower returns’ volatility (Hesse and Cihak 2007) and lower risk of default (Beck et al. 2009). Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that cooperative banks have a low propensity to take the risk of financing uncertain high-tech projects based on university knowledge. Furthermore, cooperative banks usually have limited resources and competencies for evaluating these projects, which likely are highly innovative and complex (Arnone et al. 2015). Therefore, in line with arguments on the risk-aversion effect, we contend the presence of cooperative banks in the local entrepreneurial ecosystem negatively interacts with university knowledge in determining high-tech entrepreneurship in a geographical area. Hypothesis H1b follows:

-

H1b: The relative presence of cooperative banks in the local entrepreneurial ecosystem weakens the (allegedly) positive relation between local university knowledge and the creation of high-tech ventures in a geographical area.

As aforementioned, the trust-building effect implies a superior ability of cooperative banks in monitoring prospective entrepreneurs. This ability is particularly useful in areas where, on average, residents show a strong tendency to behave opportunistically. In these areas, cooperative banks can count on their relational-lending approach and on their trust-based relationships with the local community to cope with the high probability of financing opportunistic borrowers. In comparison with commercial banks, they face lower costs of monitoring, which, in turn, result in decreased probability of credit denial to local entrepreneurs who want to create new high-tech ventures out of university knowledge. In line with these arguments, we put forth hypothesis H2:

-

H2: In areas where residents tend to behave opportunistically, the presence of cooperative banks in the local entrepreneurial ecosystem strengthens the (allegedly) positive relation between local university knowledge and creation of high-tech ventures.

3 Data and method

To study how the three key dimensions of entrepreneurial ecosystems under-investigation, i.e., university knowledge, cooperative banks and residents’ tendency to behave opportunistically, interact to determine local creation of high-tech ventures, we resort to various econometric models with the following general form:

3.1 Dependent variable

The dependent variable N_HTVsi, j is the number of new firms created in the high-tech industry i and in the province j, during the period 2012–2014. We consider 792 industry/province pairsFootnote 5 (8 industries * 99 provinces), accounting for 3774 new high-tech firms created in the period 2012–2014. To define high-tech industries, we used the 2-digit NACE rev. 2 codes associated to high-tech knowledge intensive services (i.e. 59—motion picture, video and television programme production, sound recording and music publishing activities; 60—programming and broadcasting activities; 61 - Telecommunications; 62—computer programming, consultancy and related activities; 63- Information service activities; 72—scientific research and development) and high-tech manufacturing industries (i.e., 21—manufacture of basic pharmaceutical products and pharmaceutical preparations; 26—manufacture of computer, electronic and optical products) as defined by Eurostat.Footnote 6 Our dependent variable therefore measures new firm creation in high-tech industries, as these firms are more likely to benefit from university knowledge (Schartinger et al. 2002). The data source used to collect information on the number of new firms created in each industry/province is the Italian firm registry (Movimprese), which provides data on the total population of new and active Italian firms in each year,Footnote 7 disaggregated by their geographical location (i.e. Italian province) and industry of operation (i.e., 2-digit NACE rev. 2).

Table 1 reports the distribution of the 3774 firms in our sample by industry of operation and geographical area.

3.2 Main explanatory variables

The variable UNIKNOWi, j refers to specialized university knowledge available in the province j that constitutes the knowledge base for the industry i. More specifically, UNIKNOWi, j is defined as the sum of (i) specialized knowledge that is produced by universities located in the province j (LOCAL_UNIKNOWi, j) and (ii) a spatially weighted measure (EXT_UNIKNOWi, j) that accounts for the effect of specialized university knowledge that is produced outside the province j (Anselin et al. 2000; Fischer and Varga 2003). Therefore, we calculated it as follows:

To build LOCAL_UNIKNOWi, j, we used data from the Italian Ministry of Education and Research (Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca, MIUR) on the academic staff (i.e. full, associate and assistant professors) enrolled in the 80 research active Italian universitiesFootnote 8 during the period 2009–2011. For each university, the MIUR provides data on the academic staff disaggregated by 14 scientific fields.Footnote 9 Then, we linked these scientific fields to the focal firm’s industry i, building on the findings of Schartinger et al. (2002).Footnote 10 In this way, we were able to identify the academic staff producing specialized university knowledge, i.e., university knowledge that is relevant for the industry in which high-tech ventures operate. LOCAL_UNIKNOWi, jis therefore defined as the ratio between the average size (period 2009–2011) of the academic staff enrolled in universities located in the province j and specialized in the scientific fields that constitutes the knowledge base of the industry i, and the population of the province j as in 2011.

EXT_UNIKNOWi, j is defined as follows:

where dj,k is the geographical distance (in kilometers) between the province j and the province k, LOCAL_UNIKNOWi, k refers to university knowledge that constitutes the knowledge base for the industry i generated from universities located in province k, (with k ≠ j), and α is a distance decay parameter. This parameter is set to 2.5, as this is the value that maximizes the log-likelihood of the econometric model (for a similar approach see, e.g., Bonaccorsi et al. 2014; Ghio et al. 2016).

The variable COOPERATIVEj measures the relative presence of cooperative banks in the focal province j, and it is defined as the share of bank branches in the province j owned by cooperative banks (Alessandrini et al. 2010; Deloof and La Rocca 2015). Data on the characteristics of the Italian banking industry at the local level come from the Bank of Italy statistical office,Footnote 11 which provides information on the structure of the banking industry across Italian provinces.

Finally, as a measure of the tendency of local residents to behave opportunistically, we use the evasion rate of the fee that is due by televisions’ owners. In Italy—as in many other European countries—a national law forces all households that own a television equipment to pay a fee, the so called Canone Rai. As an external agent can hardly observe the private ownership of a television equipment, the extent to which households in a province do not denounce their possession of a television and do not pay such a fee can be as a good proxy of their tendency to behave opportunistically.Footnote 12 Accordingly, we define the variable OPPORTUNISMj as the proportion of households that do not pay the television fee in the province j, as in 2011.

3.3 Controls

We include in the model an array of control variables that likely influence the creation of new high-tech ventures in a geographical area. First, we control for the characteristics of the local financial market. Following the literature studying the effects on the local productive system of the competition in the banking industry (de Guevara and Maudos 2009; Alessandrini et al. 2009; Alessandrini et al. 2010), we control for the concentration of the local banking industry by computing the Herfindahl–Hirschman concentration index. Specifically, we define the variable CONCENTRATIONj as the sum of the square of the shares of branches held by all banks that operate in the focal province j (Alessandrini et al. 2009; Alessandrini et al. 2010). Furthermore, given the prominence of venture capitalists as specialized investors for high-tech firms, we control for the local availability of venture capital with the variable VCj, which we computed as the number of initial investments made by venture capital firms in firms located in province j, in the period 2006–2011 (Samila and Sorenson 2011).

Second, we insert three variables that account for the characteristics of the productive system in the province j. More specifically, to assess agglomeration effects in the province j, we consider two variables. Namely, INCUMBENTi, j measures the number of incumbent firms located in the province j operating in the industry i, while EMPLOYMENTi, j measures the logarithm of the number of individuals employed in the industry i in the province j (Glaeser and Kerr 2009). To account for the role of industrial technology spillovers, the variable TECHj measures the number of non-academic patent applications held by inventors residing in the province j, in the period 2008–2010 per million inhabitants of the province (Qian et al. 2013).

Third, we control for side-demand effects. The variable DENSITYj is the number of residents in the province j per square kilometer, while the variable GDPj measures the gross domestics product per capita for the province j as in 2011 and accounts for differences in the income level across residents in different provinces.

Forth, we include a series of variables, which relate to the characteristics of residents in the province j and may explain their propensity to create new high-tech ventures. The variable EDUCATIONj measures the share of the residents with a university degree or a higher academic title (Qian and Acs 2013). In line with Ghio et al. (2016), the variable OPENNESSj controls for the presence of open-minded individuals in the province j. This variable is the average, for every province, of (i) the ratio between the number of foreign children enrolled in primary schools and the total number of children enrolled in province j’s primary schools; (ii) the percentage of foreign population with a university degree that reside in province j and (iii) the percentage of households of two or more people with at least one foreign person among the components. Finally, we include industry (at the 2-digit NACE rev. 2 level) and regional (at the NUTS2 level) dummies.

To build the aforementioned control variables, we resort to multiple sources. These include the above-mentioned Movimprese database (e.g., number of new and incumbent firms operating in each province, disaggregated by industry of operation), the ISTAT databaseFootnote 13 (e.g., data on residents; gross domestic product), the Bank of ItalyFootnote 14 (data on the private sector’s bank branches), the CRIOS-PATSTAT database (data on patent applications; for a detailed description see Coffano and Tarasconi 2014), the ThomsonOne database and Venture Capital Monitor (e.g., venture capital investments at the local level).

Table 2 reports a detailed description of all the variables included in the models, while Table 3 reports their summary statistics and the correlation matrix.

3.4 Estimation method

We resort to a zero-inflated negative binomial specification (for an application in a similar context see, e.g., Baptista and Mendonça 2010) to deal with the count-nature of N_HTVsi, j and with the sizable presence of observations for which it assumes value zero (in 351 out of 792 industry/province pairs the dependent variable assumes value zero). Specifically, we evaluate the appropriateness of the zero-inflated negative binomial regression model against the standard negative binomial model by Vuong tests (Vuong 1989; Cameron and Trivedi 2009). The results of the Vuong tests on the econometric estimates that we present in Section 4 generally confirm the superior performance of zero-inflated negative binomial model compared to the standard negative binomial model.Footnote 15

To assess potential multicollinearity problems, we perform the variance inflation factor (VIF) analysis. In all estimates, the mean VIF is below the threshold of 5, while the maximum VIF is below the threshold of 10 (Belsley et al. 1980). These results suggest that multicollinearity is not an issue in all our estimates.

4 Results

Table 4 shows the results of the zero-inflated negative binomial model estimates. To ease the interpretation of the coefficients, in the reported estimates we standardized (mean 0 and standard deviation 1) all the continuous variables. Column (I) refers to a baseline model, which includes only the direct effects of UNIKNOWi, j and COOPERATIVEj. To assess whether university knowledge and cooperative banks interact positively (H1a) or negatively (H1b), in column II, we include the interaction term UNIKNOWi, j∗COOPERATIVEj. Finally, in columns III and IV, we split the sample according to the local level of opportunism to provide evidence for H2. More specifically, column III refers to provinces in which OPPORTUNISMj is higher than its median value, while column IV shows the results when OPPORTUNISMj is lower than its median value.

Before analyzing the main variables of interest, let us briefly discuss the results of control variables. First, a higher level of concentration in the local banking industry relates negatively to the creation of high-tech ventures. Indeed, the coefficient of CONCENTRATIONj is negative and statistically significant at 1% in all models. Conversely, the creation of new high-tech ventures benefits from the local availability of venture capital, as suggested by the positive coefficient of VCj (significant at least at 5% in three out of four models). Quite interestingly, the positive effect of VCj on new firm creation is limited to provinces in which the level of opportunism is high (column III). As to variables capturing the characteristics of the local productive system, EMPLOYMENTj is always positive and highly significant (at 1% in most estimates), while the coefficient of INCUMBENTj is positive and significant (at 1%) in provinces with low local opportunism (column IV). Similarly, industrial patent production (TECHj) affects new firm creation only in provinces where the local tendency to behave opportunistically is low. The coefficient of TECHj is indeed positive and statistically significant at 10% in column IV, but not in column III. As to demand effects, results show that population density plays a prominent role, especially in provinces where the local level of opportunism is low, as suggested by the positive and strongly significant (at 1%) coefficient of DENSITYj reported in column IV. Conversely, higher income levels are negatively related to new firm creation in provinces with high opportunism. The coefficient of the variable GDPj is indeed negative and significant at 5% in column III. However, in these latter provinces, new firm creation in high-tech industries is positively related to the local availability of skilled human capital (EDUCATIONj). Other control variables are not significant at conventional significance levels.

We now turn attention to the main variables of interest on the whole sample of Italian provinces (column I and II). First, we observe that the level of local opportunism negatively affects the creation of new high-tech ventures. The coefficient of OPPORTUNISMj is indeed negative and significant at 10% and 5% in column I and II, respectively. Furthermore, in accordance with empirical studies within the KSTE, UNIKNOWi, j is positive and significant (at 10%) in the baseline model (column I). Conversely, the coefficient of COOPERATIVEj is not significant in the baseline model. Thus, a higher presence of cooperative banks at the local level does not directly affect the local creation of high-tech ventures. When introducing the interaction term (column II), we find a positive and statistically significant coefficient (at the 5% level) of UNIKNOWi, j and of UNIKNOWi, j∗COOPERATIVEj.

When splitting the sample according to the level of local opportunism (columns III and IV), the coefficient of OPPORTUNISMj is not significant in both subsamples. This indicates that in both subsamples we do not observe significant differences across provinces in new firm creation depending on the local level of opportunism. The negative and significant coefficients reported in columns I and II are therefore driven by the fact that provinces with a level of opportunism that is below the median value (i.e., the threshold used to split the sample) exhibit in general a lower number of new high-tech firms with respect to provinces with a level of opportunism above the median value. More interestingly, the coefficient of UNIKNOWi, j∗COOPERATIVEj is positive and statistically significant (at 1%) only in provinces where local opportunism is high (column III). Nevertheless, given the nonlinear specification of the zero-inflated negative binomial model, looking at the interaction term’s estimated coefficients is not sufficient to assess the statistical significance and the magnitude of the moderating effects associated to our hypotheses. For hypotheses testing, we therefore need a more in-depth analysis.

As a starting point, we evaluate whether the inclusion of COOPERATIVEj and UNIKNOWi, j∗COOPERATIVEj in our econometric specification results in an improvement in the model fit. To this end, we performed a series of likelihood ratio tests for the models presented in columns II, III and IV, under the null hypothesis that the joint inclusion of the two above-mentioned variables does not result in a statistically significant improvement in the model fit. The chi-squared value for the test with 2 degrees of freedom is 2.99 (p value = 0.084), 10.40 (p value = 0.001), and 0.23 (p value = 0.630) for models presented in columns II, III, and IV, respectively. Hence, we can reject the null hypothesis only in models presented in columns II (but with low statistical significance) and III, but not in the model presented in column IV. In other words, the local presence of cooperative banks does not exert any statistically significant influence on new firm creation if the local level of opportunism is low.

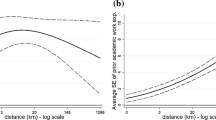

We therefore focus on the results presented in the columns II and III of Table 4 and we study the average marginal effects (MEs) of UNIKNOWi, j as COOPERATIVEj varies in the two models. The average ME is the average increase in the number of new firms in the province/industry due to a one standard deviation increase in the variable of interest UNIKNOWi, j.

Table 5 shows the ME of UNIKNOWi, j on N_HTVsi, j for different values of COOPERATIVEj, in all provinces and in provinces where local opportunism is high. The results are consistent with H1a and H2. In both cases, when COOPERATIVEj is below its mean value, one standard deviation increase in UNIKNOWi, j does not lead to a statistically significant increase in the number of local new high-tech firms. However, the ME of UNIKNOWi, j is statistically significant for high values of COOPERATIVEj (i.e., when COOPERATIVEj is above its mean). More specifically, when COOPERATIVEj is one standard deviation above its mean value, one standard deviation increase in UNIKNOWi, j leads to an average increase of 0.762 new high-tech firms in each industry/province in all provinces (significant at the 1% level).Footnote 16 When considering only the provinces with a high level of opportunism, the average increase in the number of new firms due to a one standard deviation increase of UNIKNOWi, j is even higher (1.622) and still strongly significant (at the 1% level).

5 Robustness checks

To further validate our findings on the positive interaction between university knowledge and cooperative banks in provinces in which the local level of opportunism is high, we run several robustness checks. First, one may argue that our results are driven by the lack of some relevant controls as regard to the characteristics of the local financial market. To address this concern, we run additional zero inflated negative binomial regressions on the subsample of provinces with high opportunism by including the number of bank branches per square km (BRANCHESj, in column I of Table 6), the share of bank branches owned by large banks (LARGEj, in column II of Table 6), and the share of bank branches owned by foreign banks (FOREIGNj, in column III of Table 6). All these additional controls are not significant and results concerning the interaction of university knowledge and cooperative banks in determining the creation of high-tech ventures remain unchanged. Furthermore, we also test whether our results are robust when including the interactive term UNIKNOWi, j∗VCj. We include this robustness check to further support the idea that, in entrepreneurial ecosystems, local university and local financial system interact to determine local high-tech entrepreneurship. Results (column IV of Table 6) show that this interactive term is positive and statistically significant at the 10%. However, the interaction between UNIKNOWi, j and COOPERATIVEj is still positive and statistically significant at the 1% level.

Second, despite the VIF analysis (see Section 3.4) on independent variables excludes multicollinearity problems, it is worth noting that the variable COOPERATIVEj exhibits a quite high negative correlation (i.e., − 0.45) with CONCENTRATIONj. Therefore, in column V of Table 6 we exclude the variable CONCENTRATIONj. With respect to our main results, we observe a positive and significant (at 1%) coefficient of COOPERATIVEj, while results concerning the interactive term UNIKNOWi, j∗COOPERATIVEj are unchanged.

Third, to offer additional support to our insight on the superior abilities of cooperative banks to cope with information asymmetries associated with high-tech entrepreneurial projects, we check whether the positive role of cooperative banks is actually driven by the high-tech nature of firms in our sample or whether it is a more general effect towards a broader group of new firms. To this aim, we repeat estimations on a sample of new firms created in non-high-tech industries.Footnote 17 Results (column VI of Table 6) suggest that the role of cooperative banks (and of university knowledge) is in this case negligible.

Forth, one can argue that the variable COOPERATIVEj is endogenous. Unobserved factors at the province level may affect both the number of new high-tech ventures in a province and the relative presence of cooperative banks in that province. To deal with this issue, we resort to an instrumental variable approach by using data on the Italian banking system as in 1936 (e.g., Guiso et al. 2004; Benfratello et al. 2008). More specifically, we instrument COOPERATIVEj and UNIKNOWi, j∗COOPERATIVEj with the share of bank branches owned by cooperative banks in 1936 and its interaction with UNIKNOWi, j. In a pseudo first stage regression (please see Table 9 in the Appendix) we find that the share of bank branches owned by cooperative banks in 1936 is a significant (at the 1%) predictor of COOPERATIVEj when regressed with other independent variables. More importantly, results reported in the column VII of Table 6 still confirm our main findings.

Finally, we use an alternative econometric specification, in which we consider all provinces in the sample and we include the three-way interaction between UNIKNOWi, j, COOPERATIVEj and OPPORTUNISMj. Table 7 shows the MEs of UNIKNOWi, j for different values (i.e., one standard deviation below the mean, mean value, and one standard deviation above the mean) of both COOPERATIVEj and OPPORTUNISMj. Results of the zero-inflated negative binomial model when using the three-way interaction specification used to obtain the MEs shown in Table 7 are available in the Table 10 of the Appendix.

The MEs reported in Table 7 are in line with the results reported in Section 5. Indeed, for high values of both OPPORTUNISMj and COOPERATIVEj, the ME of UNIKNOWi, j is positive (4.012) and significant at the 1% level. If we keep the value of OPPORTUNISMj at one standard deviation above its mean, a decrease in the value of COOPERATIVEj leads to a decrease in the ME of UNIKNOWi, j. In other words, the relative presence of cooperative banks in the local banking industry magnifies the effect of UNIKNOWi, j in geographical areas characterized by high levels of opportunism. Conversely, for low values of OPPORTUNISMj (i.e., one standard deviation below its mean) the ME of UNIKNOWi, j is positive and significant (at the 1%) only if the relative presence of cooperative banks in the local banking industry is low. This latter result seems to suggest that in geographical areas characterized by low levels of opportunism the trust-building effect associated to cooperative banks is of little value for stimulating the creation of new high-tech ventures out of university knowledge.

6 Concluding remarks

This paper theoretically discusses and empirically documents how three main elements of entrepreneurial ecosystems—local universities, local financial system, and residents’ attitudes—interact to determine local high-tech entrepreneurship. Specifically, our findings show that, in areas where the level of residents’ opportunism is high, the relative presence of cooperative banks in the entrepreneurial ecosystem magnifies the positive effect of university knowledge on the creation of new high-tech firms. Indeed, in such areas, the trust-building effect of cooperative banks, which favors the financing of high-tech entrepreneurial projects based on university knowledge dominates the risk aversion effect, which conversely hampers this financing.

The paper offers several contributions to the current debate on entrepreneurial ecosystems. First, while the bulk of the literature addresses the diverse elements of ecosystems separately, this work focuses on their interplay. In so doing, it heeds the call for adopting a systemic perspective, when examining entrepreneurial ecosystems (Alvedalen and Boschma 2017; Acs et al. 2014). Such a perspective is still rare in the field, a fact that appears surprisingly if one considers that interactions among ecosystem elements are at the core of ecosystems’ success in new venture creation and growth (Stam 2015).

Second, the paper advances knowledge on ecosystems’ key dimensions. As aforementioned, empirical works within KSTE consistently document that the local availability of knowledge fosters high-tech entrepreneurship in a geographical area. Prior works mainly show on the direct impact of knowledge spillovers from universities (e.g., Acosta et al. 2011; Bonaccorsi et al. 2013, 2014) and incumbent firms (Lasch et al. 2013) on local entrepreneurship. Conversely, scholars have given comparatively less attention to whether and how the characteristics of the local context magnify (or hamper) the effect of these spillovers. Recent exceptions are in Qian and Acs (2013) and Qian et al. (2013), who investigated the moderating role of the local human capital on the exploitation of industrial knowledge spillovers embedded in patents. In the context of knowledge spillovers generated by universities, Ghio et al. (2016) find a positive moderating effect of the open-minded attitudes of individuals that reside in an area. To the best of our knowledge, no contribution analyzes whether and how the local financial system influences the allegedly positive effect of local university knowledge on high-tech entrepreneurship. This is a relevant gap. The financing of high-tech firms is indeed a spatially bounded phenomenon, with new ventures collecting capital mainly by local investors (Cumming and Dai 2010; Chen et al. 2010; Sorenson and Stuart 2001). Thus, the local financial system should matter for high-tech entrepreneurship in a geographical area (see Guiso et al. 2004 for a similar argument). In this latter regard, the paper originally examines a dimension of the local financial system, i.e., cooperative banks, which the literature on entrepreneurial ecosystems largely disregards. This literature acknowledges the importance of venture capitalists (e.g., Sussan and Acs 2017), business angels (Wright et al. 2017), and commercial banks (e.g. Cohen 2006); to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study, which refers to cooperative banks in the context of entrepreneurial ecosystems. This is an interesting addition to the debate in the field as cooperative banks play a major role in financing new ventures and small firms both in developed countries, like Italy or Germany (De Massis et al. 2017) or in developing ones, like India. Finally, the paper adheres to the view that residents’ attitudes are a key element of entrepreneurial ecosystems. To date, researchers have mainly spotlighted positive attitudes, including tolerance towards risk and acceptance of business failure without stigmatization (Graves 2011), open-minded (Ghio et al. 2016) and giving (Feld 2012) approaches, and positive views of the entrepreneurial profession (Acs et al. 2014). We state that also negative attitudes—like residents’ tendency to behave opportunistically—play a role and enhance the importance of ecosystem dimensions, which act as safeguards against these attitudes.

As any other research, the paper has limitations that open up avenues for future research. First, it focuses on the Italian case. This setting is highly appropriate for our study, but may hamper the generalizability of our results. In particular, one may wonder whether our findings change in countries where the venture capital market is well developed. We have indeed formulated our hypotheses H1b and H2 moving from the premise that cooperative banks potentially have superior abilities to cope with information asymmetries, which hamper the attraction of external finance by local prospective entrepreneurs, who want to create new high-tech ventures out of university knowledge. However, the entrepreneurial finance literature states that venture capitalists are specialized investors that can cope with this information asymmetries, e.g., through intensive screening, participation in the board of directors, use of convertible securities, staged financing (e.g., Gompers 1995; Gompers and Lerner 2001; Kaplan and Strömberg 2003; Denis 2004). Even more importantly, venture capitalists complement the provision of financial resources with a series of value-added services—including strategic and managerial support (Hellmann and Puri 2002)—that boost the performance of firms in their portfolio (Da Rin et al. 2011). Thus, do cooperative banks still matter in areas where the presence of specialized venture capital investors is remarkable?

Second, we claim that cooperative banks’ superior abilities to cope with information asymmetries come from their relational-lending approach. However, despite this financing approach is still widespread among cooperative banks, nowadays these banks are increasingly subject to international regulations, which force them to comply with the rules typical of more traditional financing approaches (e.g., Fiordelisi and Mare 2014). This hold particularly true for larger cooperative banks whose organization resembles that of their commercial counterparts and which have more resources and competencies to invest in (risky) businesses based on university knowledge (Berger et al. 2005; Berger and Udell 2002, 2006). More generally, we welcome future studies, which take into account other traits and features of cooperative banks apart from that cited in the paper. Third, our analysis at the level of the geographical area disregards that the interactions investigated in the paper crucially depend on individual characteristics of cooperative bank managers and local prospective entrepreneurs. For instance, we stress the bright side of cooperative bank mangers’ embeddedness in local community. However, these strong social linkages may also drive the acceptance/denial of credit in improper ways, thus creating severe governance issues (see, e.g., Fonteyne 2007). Likewise, some prospective entrepreneurs may have characteristics that induce cooperative bank managers to believe that they are more prone to behave opportunistically (for instance because they have a bad reputation in the local community), despite they live in areas with low opportunism. Finally, some limitations result from the ways in which we measure our explanatory variables. Specifically, we account for the relative presence of cooperative banks in a province by using the share of bank branches in that province owned by cooperative banks. However, different branches may have different credit volumes, being differently active in lending activities. Unfortunately, we do not have province-level data on the share of bank credit from cooperative banks over the total bank credit. Moreover, in line with what we do in other published works (e.g., Ghio et al. 2016), we measure the local availability of university knowledge by referring to the size of the academic staff. However, one should also use other measures, like publications, academic patents, students, research contracts between universities and local firms, and so on.

Despite these limitations, the paper has relevant implications for the governance of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Our work states that well-functioning local financial system helps the conversion of university knowledge into new high-tech ventures. According to our findings, this holds particular true when the local context worsens entrepreneurs’ chances to access external capital as areas where residents tend to behave opportunistically. In these areas, cooperative banks, being highly effective in dealing with monitoring problems that usually lead to credit denial, can be a valuable source of finance for local prospective entrepreneurs, who want to do business out of university knowledge. Therefore, policy interventions in favor of these banks are particularly welcome in areas where opportunism is high, being instead less crucial where the level of opportunism is low and the monitoring abilities of cooperative banks are less useful. These policy interventions should also take into account that these banks are traditionally risk-adverse and suffer from liability of smallness, having limited resources and competenciesFootnote 18 in comparison with nationwide commercial banks (Usai and Vannini 2005; Ferri et al. 2014). Accordingly, in governing local entrepreneurial ecosystems, it is important to take actions that mitigate cooperative banks’ risk-aversion and liability of smallness. Indeed, these drawbacks may lead these banks to deny credit to high-tech entrepreneurial projects based on university knowledge, despite their superior abilities to evaluate these projects and monitor their entrepreneurs. For instance, interventions stimulating alliances of cooperative banks with local stakeholders go exactly in this direction. These interventions should favor the collaborations among cooperative banks and between cooperative banks and other lenders (e.g., commercial banks, but also venture capitalists and business angels) to share the risk of financing high-tech ventures created out of university knowledge. Furthermore, policy interventions should encourage cooperative banks to join forces with actors of the entrepreneurial ecosystem having strong technological expertise, e.g., incubators or universities’ technology transfer offices. Indeed, the technological competencies of these actors would ideally complement the abilities of cooperative banks to acquire soft information through their local embeddedness, further facilitating the conversion of local university knowledge into high-tech entrepreneurship within the ecosystem.

Notes

In line of this argument, having the US metropolitan areas as the unit of analysis, Samila and Sorenson (2011) have empirically demonstrated that the local availability of venture capital stimulates new firm creation at the local level.

Furthermore, it is worth noting that Italian cooperative banks are highly decentralized and poorly integrated (Ayadi et al. 2010) so that their branches have high autonomy in investment decisions.

Information asymmetries in the financing of new ventures in high-tech industry are made worse by the absence a track-record and by the fact that entrepreneurs in these industries are often reluctant to disclose relevant information on their innovative ideas to potential external investors because of appropriability concerns (Anton and Yao 2002; Ueda 2004; Katila et al. 2008. Moreover, traditional instruments that external financiers use to limit the risks associated with information asymmetries (e.g., the request for collaterals) are unsuitable for new ventures that base their competitive advantage on intangible assets, i.e., knowledge and innovation (Hall 2002; Denis 2004).

Due to data constraints, we excluded from the analysis the provinces of the Sardinia region. In 2011, the Italian Government re-organized the four provinces of the Sardinia region into eight new provinces. However, in several cases, the statistical sources of data that we use in the present study provide information on the Sardinia region by referring to the old classification based on four provinces.

Following the definition provided by the EUMIDA database, a university is “research active” if research is considered as constitutive part of institutional activities and it is organized with a durable perspective. See http://ec.europa.eu/research/era/docs/en/eumida-final-report.pdf for further information.

(1) Mathematics and computer sciences; (2) Physics; (3) Chemistry; (4) Earth sciences; (5) Biology; (6) Medicine; (7) Agricultural and veterinary sciences; (8) Civil engineering and architecture; (9) Industrial and information engineering; (10) Philological-literary sciences, antiquities and arts; (11) History, philosophy, psychology and pedagogy; (12) Law; (13) Economics and statistics; (14) Political and social sciences.

See the Appendix for Table 8 that shows the link between the high-tech industries and the 14 university scientific fields.

Faced with the problem of license fee evasion, in 2016, the Italian Government opted to lower the fee and included it into the electricity bill in an attempt to eliminate evasion.

Our findings are robust to other estimation techniques. Specifically, results (available from the authors upon request) do not change when using negative binomial and Poisson models.

The average number of new high-tech firms in each industry/province is 4.765.

According to the Eurostat classification we consider medium-tech manufacturing industries (NACE rev. 2 2 digit codes: 20, 27, 28, 29 and 30), knowledge-intensive market services (50, 51, 69, 70, 71, 73, 74, 78, and 80), knowledge-intensive financial services (64, 65, and 66) and other knowledge-intensive services (58, 75, 85, 86, 87, 88, 90, 91, 92, and 93).

While the literature depicts cooperative banks as small and characterized by self-governance (e.g., Brighi et al. 2016), exceptions exist. Large and more structure cooperative banks tend to adopt lending approaches that resemble those of commercial banks.

References

Acosta, M., Coronado, D., & Flores, E. (2011). University spillovers and new business location in high-technology sectors: Spanish evidence. Small Business Economics, 36(3), 365–376.

Acs, Z. J., Braunerhjelm, P., Audretsch, D. B., & Carlsson, B. (2009). The knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 32(1), 15–30.

Acs, Z. J., Autio, E., & Szerb, L. (2014). National systems of entrepreneurship: measurement issues and policy implications. Research Policy, 43(3), 476–494.

Acs, Z. J., Stam, E., Audretsch, D. B., & O’Connor, A. (2017). The lineages of the entrepreneurial ecosystem approach. Small Business Economics, 49(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9864-8.

Alessandrini, P., Presbitero, A. F., & Zazzaro, A. (2009). Banks, distances and firms’ financing constraints. Review of Finance, 13(2), 261–307.

Alessandrini, P., Presbitero, A. F., & Zazzaro, A. (2010). Bank size or distance: what hampers innovation adoption by SMEs? Journal of Economic Geography, 10(6), 845–881.

Alvedalen, J., & Boschma, R. (2017). A critical review of entrepreneurial ecosystems research: towards a future research agenda. European Planning Studies, 25(6), 887–903.

Angelini, P., & Cetorelli, N. (2003). The effects of regulatory reform on competition in the banking industry. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 35(5), 663–684.

Anselin, L., Varga, A., & Acs, Z. J. (2000). Geographic and sectoral characteristics of academic knowledge externalities. Papers in Regional Science, 79(4), 435–443.

Anton, J. J., & Yao, D. A. (2002). The sale of ideas: strategic disclosure, property rights, and contracting. The Review of Economic Studies, 69(3), 513–531.

Arnone, M., Farina, G., & Modina, M. (2015). Technological districts and the financing of innovation: opportunities and challenges for local banks. Economic Notes, 44(3), 483–510.

Audretsch, D. B., & Lehmann, E. E. (2005). Does the knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship hold for regions? Research Policy, 34(8), 1191–1202.

Audretsch, D. B., & Stephan, P. (1999). How and why does knowledge spill over in biotechnology? In D. B. Audretsch & R. Thurik (Eds.), Innovation, industry evolution, and employment (pp. 216–229). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Auerswald, P. E., & Dani, L. (2017). The adaptive life cycle of entrepreneurial ecosystems: the biotechnology cluster. Small Business Economics, 49(1), 97–117. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9869-3.

Ayadi, R., Llewellyn, D. T., Schmidt, R. H., Arbak, E., & De Groen, W. P. (2010). Investigating diversity in the banking sector in Europe. CEPS Paperbacks. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1677335.

Baptista, R., & Mendonça, J. (2010). Proximity to knowledge sources and the location of knowledge-based start-ups. The Annals of Regional Science, 45(1), 5–29.

Beck, T., Hesse, H., Kick, T., & von Westernhagen, N. (2009). Bank ownership and stability: evidence from Germany. Tilburg University, Working Paper. Available at: http://www.tilburguniversity.edu/webwijs/files/center/beck/bankstabilityownership.pdf.

Belsley, D. A., Kuh, E., & Welsch, R. E. (1980). Regression diagnostics: identifying influential data and sources of collinearity. New York: Wiley.

Benfratello, L., Schiantarelli, F., & Sembenelli, A. (2008). Banks and innovation: microeconometric evidence on Italian firms. Journal of Financial Economics, 90(2), 197–217.

Berger, A. N., & Udell, G. F. (2002). Small business credit availability and relationship lending: the importance of bank organisational structure. The Economic Journal, 112(477), F32–F53.

Berger, A. N., & Udell, G. F. (2006). A more complete conceptual framework for SME finance. Journal of Banking & Finance, 30(11), 2945–2966.

Berger, A. N., Miller, N. H., Petersen, M. A., Rajan, R. G., & Stein, J. C. (2005). Does function follow organizational form? Evidence from the lending practices of large and small banks. Journal of Financial Economics, 76(2), 237–269.

Bertoni, F., Colombo, M. G., & Quas, A. (2015). The pattern of venture capital investments in Europe. Small Business Economics, 45(3), 543–560.

Bonaccorsi, A., Colombo, M. G., Guerini, M., & Rossi-Lamastra, C. (2013). University specialization and new firm creation across industries. Small Business Economics, 41(4), 837–863.

Bonaccorsi, A., Colombo, M. G., Guerini, M., & Rossi-Lamastra, C. (2014). The impact of local and external university knowledge on the creation of knowledge-intensive firms: Evidence from the Italian case. Small Business Economics, 43(2), 261–287.

Brighi, P., Lucarelli, C., & Venturelli, V. (2016). Predictive strenghts of lending technologies. Working Paper.

Brown, R., & Mason, C. (2014). Inside the high-tech black box: A critique of technology entrepreneurship policy. Technovation, 34(12), 773–784.

Brown, R., & Mason, C. (2017). Looking inside the spiky bits: a critical review and conceptualisation of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Small Business Economics, 49(1), 11–30.

Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (2009). Microeconometrics using Stata (Vol. 5). College Station: Stata Press.

Carpenter, R. E., & Petersen, B. C. (2002). Capital market imperfections, high-tech investment, and new equity financing. The Economic Journal, 112(477), F54–F72.

Cesarini, F., Ferri, G., & Giardino, M. (1996). Credito e sviluppo. Banche locali cooperative e imprese minori. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Chen, H., Gompers, P., Kovner, A., & Lerner, J. (2010). Buy local? The geography of venture capital. Journal of Urban Economics, 67(1), 90–102.

Coffano, M., & Tarasconi, G. (2014). CRIOS-Patstat database: sources, contents and access rules. Center for Research on Innovation, Organization and Strategy, Working Paper No. 1. Available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2404344.

Cohen, B. (2006). Sustainable valley entrepreneurial ecosystems. Business Strategy and the Environment, 15(1), 1–14.

Colombo, M. G., Croce, A., & Guerini, M. (2013). The effect of public subsidies on firms’ investment–cash flow sensitivity: Transient or persistent? Research Policy, 42(9), 1605–1623.

Colombo, M. G., Franzoni, C., & Rossi-Lamastra, C. (2015). Internal social capital and the attraction of early contributions in crowdfunding. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(1), 75–100.

Cumming, D., & Dai, N. (2010). Local bias in venture capital investments. Journal of Empirical Finance, 17(3), 362–380.

Da Rin, M., Hellmann, T. F., & Puri, M. (2011). A survey of venture capital research. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. w17523. Available at: http://www.nber.org/papers/w17523.pdf.

de Guevara, J. F., & Maudos, J. (2009). Regional financial development and bank competition: effects on firms’ growth. Regional Studies, 43(2), 211–228.

De Massis, A., Audretsch, D., Uhlaner, L., & Kammerlander, N. (2017). Innovation with limited resources: Management lessons from the German Mittelstand. Journal of Product Innovation Management. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12373.

Deloof, M., & La Rocca, M. (2015). Local financial development and the trade credit policy of Italian SMEs. Small Business Economics, 44(4), 905–924.

Denis, D. J. (2004). Entrepreneurial finance: an overview of the issues and evidence. Journal of Corporate Finance, 10(2), 301–326.

EVCA (2015). 2014 European Private Equity Activity. Statistics on Fundraising, Investments & Divestments. Available at: http://www.investeurope.eu/media/385581/2014-european-private-equity-activity-final-v2.pdf.

Feld, B. (2012). Startup communities: building an entrepreneurial ecosystem in your city. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

Ferri, G., Kalmi, P., & Kerola, E. (2014). Does bank ownership affect lending behavior? evidence from the Euro area. Journal of Banking & Finance, 48, 194–209.

Fiordelisi, F., & Mare, D. S. (2014). Competition and financial stability in European cooperative banks. Journal of International Money and Finance, 45, 1–16.

Fischer, M. M., & Varga, A. (2003). Spatial knowledge spillovers and university research: evidence from Austria. The Annals of Regional Science, 37(2), 303–322.

Fontes, M. (2005). The process of transformation of scientific and technological knowledge into economic value conducted by biotechnology spin-offs. Technovation, 25(4), 339–347.

Fonteyne, W. (2007). Cooperative Banks in Europe-Policy Issues. International Monetary Fund, Working Paper No. 07/159. Available at: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2007/wp07159.pdf.

Fritsch, M., & Aamoucke, R. (2013). Regional public research, higher education, and innovative start-ups: an empirical investigation. Small Business Economics, 4(4), 865–885.

Gertler, M. S. (2010). Rules of the game: the place of institutions in regional economic change. Regional Studies, 44(1), 1–15.

Ghio, N., Guerini, M., Lehmann, E. E., & Rossi-Lamastra, C. (2015). The emergence of the knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 44(1), 1–18.

Ghio, N., Guerini, M., & Rossi-Lamastra, C. (2016). University knowledge and the creation of innovative start-ups: an analysis of the Italian case. Small Business Economics, 47(2), 293–311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9720-2.

Glaeser, E. L., & Kerr, W. (2009). Local industrial conditions and entrepreneurship: show much of the spatial distribution can we explain? Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 18(3), 623–663.

Gompers, P. A. (1995). Optimal investment, monitoring, and the staging of venture capital. The Journal of Finance, 50(5), 1461–1489.

Gompers, P., & Lerner, J. (2001). The venture capital revolution. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15(2), 145–168.

Graves, W. (2011). The southern culture of risk capital: the path dependence of entrepreneurial finance. Southeastern Geographer, 51(1), 49–68.

Guerini, M., & Quas, A. (2016). Governmental venture capital in Europe: screening and certification. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(2), 175–195.

Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2004). Does local financial development matter? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(3), 929–969.

Hall, B. H. (2002). The financing of research and development. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 18(1), 35–51.

Hellmann, T., & Puri, M. (2002). Venture capital and the professionalization of start-up firms: empirical evidence. The Journal of Finance, 57(1), 169–197.

Hesse, H., & Cihak, M. (2007). Cooperative banks and financial stability. International Monetary Fund, Working Paper No. 07/02. Available at: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2007/wp0702.pdf.

Howorth, C., & Moro, A. (2006). Trust within entrepreneur bank relationships: insights from Italy. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(4), 495–517.

Isenberg, D. J. (2010). How to start an entrepreneurial revolution. Harvard Business Review, 88(6), 40–50.

Isenberg, D. (2011). The entrepreneurship ecosystem strategy as a new paradigm for economic policy: Principles for cultivating entrepreneurship. Babson College. Available at: http://entrepreneurialrevolution.com.

Kaplan, S. N., & Strömberg, P. (2003). Financial contracting theory meets the real world: An empirical analysis of venture capital contracts. The Review of Economic Studies, 70(2), 281–315.

Katila, R., Rosenberger, J. D., & Eisenhardt, K. M. (2008). Swimming with sharks: technology ventures, defence mechanisms and corporate relationships. Administrative Science Quarterly, 53(2), 295–332.

Kelly, R. (2011). The Performance and Prospects of European Venture Capital. European Investment Fund, Working Paper No. 2011/09. Available at: http://www.eif.org/news_centre/publications/eif_wp_2011_009_EU_Venture.pdf.

Kerr, W., Lerner, J., & Schoar, A. (2014). The consequences of entrepreneurial finance: Evidence from angel financings. Review of Financial Studies, 27(1), 20–55.

Lasch, F., Robert, F., & Le Roy, F. (2013). Regional determinants of ICT new firm formation. Small Business Economics, 40(3), 671–686.

Lerner, J. (1995). Venture capitalists and the oversight of private firms. The Journal of Finance, 50(1), 301–318.

Minetti, R., & Zhu, S. C. (2011). Credit constraints and firm export: Microeconomic evidence from Italy. Journal of International Economics, 83(2), 109–125.

Qian, H., & Acs, Z. J. (2013). An absorptive capacity theory of knowledge spillover entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 40(2), 185–197.

Qian, H., & Yao, X. (2017). The Role of Research Universities in US College-Town Entrepreneurial Ecosystems. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2938194.

Qian, H., Acs, Z. J., & Stought, R. R. (2013). Regional systems of entrepreneurship: the nexus of human capital, knowledge and new firm formation. Journal of Economic Geography, 13(4), 559–587.

Rasmusen, E. (1988). Mutual banks and stock banks. Journal of Law and Economics, 31(2), 395–421.

Riciola, & Furlò (2016) Qual è la banca delle startup italiane? Il credito cooperativo, lo dicono i numeri. http://startupitalia.eu/52853-20160324-fondo-di-garanzia-startup-credito-cooperativo. Accessed on 31st Oct 2016.

Samila, S., & Sorenson, O. (2011). Venture capital, entrepreneurship, and economic growth. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 93(1), 338–349.

Schartinger, D., Rammer, C., Fischer, M. M., & Fröhlich, J. (2002). Knowledge interactions between universities and industry in Austria: sectoral patterns and determinants. Research Policy, 31(3), 303–328.

Schneider, C., & Veugelers, R. (2010). On young highly innovative companies: why they matter and how (not) to policy support them. Industrial and Corporate Change, 19(4), 969–1007.

Shane, S., & Venkataraman, S. (2000). The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 217–226.

Sorenson, O., & Stuart, T. E. (2001). Syndication networks and the spatial distribution of venture capital investments. The American Journal of Sociology, 106(6), 1546–1588.

Spigel, B. (2017). The relational organization of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(1), 49–72.

Stam, E. (2015). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and regional policy: a sympathetic critique. European Planning Studies, 23(9), 1759–1769.

Stam, F. C., & Spigel, B. (2016). Entrepreneurial ecosystems. USE Discussion paper series, 16(13), 1–18.

Stephan, P. E. (2012). How economics shapes science. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Sussan, F., & Acs, Z. J. (2017). The digital entrepreneurial ecosystem. Small Business Economics, 49(1), 55–73.

Ueda, M. (2004). Banks versus venture capital: Project evaluation, screening, and expropriation. The Journal of Finance, 59(2), 601–621.

Usai, S., & Vannini, M. (2005). Banking structure and regional economic growth: lessons from Italy. The Annals of Regional Science, 39(4), 691–714.

Vuong, Q. H. (1989). Likelihood ratio tests for model selection and non-nested hypotheses. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 57(2), 307–333.

Wright, M., Siegel, D. S., & Mustar, P. (2017). An emerging ecosystem for student start-ups. Journal of Technology Transfer, 42(4), 909–922.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ghio, N., Guerini, M. & Rossi-Lamastra, C. The creation of high-tech ventures in entrepreneurial ecosystems: exploring the interactions among university knowledge, cooperative banks, and individual attitudes. Small Bus Econ 52, 523–543 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9958-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9958-3