Abstract

Despite the omnipresent reach of the Internet, evidence exists that geography matters in crowdfunding. This paper shows that some salient characteristics of the geographical area in which entrepreneurs reside affect the success of the crowdfunding projects they propose. Specifically, we theoretically discuss and empirically document that the altruism of people residing in the area (i.e., local altruism) increases the likelihood of success. Moreover, the strength of this effect depends on the level of social capital in the area (i.e., localized social capital). Building on the extant literature, we claim that localized social capital has two main dimensions: the social relations among residents and their compliance with social norms. Using a dataset of 618 proponents that launched 457 crowdfunding projects on 13 Italian reward-based platforms, we find that social relations magnify the effect of local altruism. Conversely, compliance with social norms does not have any moderating effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In reward-based crowdfunding, backers receive non-monetary benefits in return for the money they pledge to projects, for instance, public acknowledgment, credit for an album or a video game, or the possibility of pre-ordering products or services (Belleflamme et al. 2013, p. 317). Many people (hereafter, proponents) post their entrepreneurial projects on reward-based crowdfunding platforms (hereafter, RB entrepreneurial projects), sometimes raising sizable amounts of money. The Pebble Watch Project, whose proponent raised $10,266,845 from 68,929 backers on the reward-based platform, KickstarterFootnote 1, is a case in point (see, e.g., Younkin and Kashkooli 2016 for a recent discussion).

To date, our knowledge of what drives the success of RB entrepreneurial projects remains limited because the extant studies on the topic have not explicitly focused on this kind of projects. Current research thus runs the risk of attributing to a smaller and peculiar class of projects the findings of contributions examining a larger and heterogeneous population. The present paper helps fill this gap by answering this overarching research question: Do the characteristics of the geographical area where a proponent resides affect the success of the RB entrepreneurial project(s) that s/he proposes? In our view, this research question is highly relevant to the current debate on crowdfunding. Evidence exists that local characteristics affect entrepreneurs’ ability to attract external financing (Guiso et al. 2004a, 2004b). However, the crowdfunding literature is silent in this regard, despite the fact that it has shown that geography affects this Internet-based financing channel. Specifically, prior works have found that geographical proximity between proponents and backers helps attract contributions (Agrawal et al. 2011; Ordanini et al. 2011; Hornuf and Schimtt 2016; Mendes-Da-Silva et al. 2016), as it reduces information asymmetries between the two parties. Exploring how the characteristics of the area where proponents reside affect the success of RB entrepreneurial projects is an interesting addition to this literature. Those living near proponents form a pool of potential backers who have lower information asymmetries and thus are potentially likely keen to contribute. However, people residing in diverse geographical areas are heterogeneous along many dimensions that may influence their propensity to contribute, ultimately affecting the success of local proponents in crowdfunding their RB entrepreneurial projects. In particular, scholars have found that backers’ contributions (even to for-profit projects, Gerber and Hui 2013)Footnote 2 depend not only on financial motives but also on altruism (Allison et al. 2015; Gleasure and Feller 2016;), i.e., on individual tendency to perform costly actions that confer economic benefits to other people with the aim of helping them (Fehr and Fischbacher 2003). Along this line of reasoning, we argue that the altruism of people residing in a geographical area, i.e., local altruism, positively influences the propensity of the local pool of potential backers to contribute to RB entrepreneurial projects posted by local proponents. As we explain in the following section, our insight is that despite the for-profit orientation of RB entrepreneurial projects, in reward-based crowdfunding there is no direct monetary return, and thus, people (also) contribute due to the altruistic desire to help others. Furthermore, we draw on studies of the importance of social capital in crowdfunding (Mollick 2014; Colombo et al. 2015a; Vismara 2016a; Vismara 2016b) to argue that the structure and nature of social relations in an area, i.e., localized social capital (Laursen et al. 2012a), moderate the allegedly positive effect of local altruism. Indeed, both the web of relations linking people in the area and their compliance with social norms, which are the two pillars of localized social capital (Putnam 1995), help mobilize the local pool of altruistic residents to contribute to their neighbors’ RB entrepreneurial projects.

We test our conjectures using a hand-collected dataset of 618 proponents (including individuals, teams of individuals, and organizations) who reside in 88 Italian provinces (NUTS3 level) and launched 457 RB entrepreneurial projects on 13 Italian reward-based crowdfunding platforms from October 16, 2012 to July 1, 2014. We think that the Italian context is well suited to our study, as Italian provinces differ in many characteristics and are highly heterogeneous in terms of localized social capital (Putnam et al. 1993). The results confirm that local altruism positively affects local proponents’ success in RB entrepreneurial projects; local social relations magnify this effect, while local compliance with social norms has no effect.

The paper proceeds as follows. In “Theoretical framework” section, we present our research hypotheses. “Data and methodology” section describes the dataset and the methodology used in the empirical analysis. “Results” section reports the results of the econometric estimations. “Robustness checks” section presents a range of robustness checks. Finally, “Conclusions” section concludes the paper by summarizing its main findings, acknowledging its limitations, illustrating its academic and practical relevance, and proposing directions for further research.

2 Theoretical framework

2.1 Geographical proximity and crowdfunding

Despite the omnipresent reach of the Internet, space bounds many Internet-based activities (Wang et al. 2003; Forman et al. 2005), including online transactions, which are more likely to occur between buyers and sellers in the same geographical area (Hortaçsu et al. 2009). Crowdfunding is no exception. Based on in-depth case studies of three crowdfunding initiatives, Ordanini et al. (2011) have shown that family and friends who live near proponents are usually the first backers of their projects. Taking advantage of a large dataset of funding relations between backers and proponents on Sellaband.com, an online crowdfunding site for music bands, Agrawal et al. (2011) found quantitative support for this qualitative evidence. The authors have documented that backers tend to invest in local bands and have attributed this proximity effect to musicians’ family and friends. A more recent study (Agrawal et al. 2015) has found that backers located near a proponent are less responsive to information about capital raised, which is an important signal of project quality (Colombo et al. 2015a). In a similar vein, Lin and Viswanathan (2016) have documented the existence of a home bias in lending-based crowdfunding, attributing its existence to both economic and behavioral motives.

The overarching idea of this research stream is that geographical proximity reduces information asymmetries that are particularly severe in crowdfunding. First, proximity favors face-to-face interactions (Morgan 2004) through which a project’s proponent and backers can easily share relevant information about the project’s quality and the proponent’s reliability. The widespread diffusion of social networks and Internet-based communications also allows proponents and backers to interact at long distance. However, the literature has documented that information transferred through face-to-face interaction is richer than information transmitted through the Internet, as it encompasses tacit components that are difficult to transfer without direct interactions (Boschma 2005). Second, as noted in the venture capital literature (e.g., Lerner 1995), geographical proximity favors investor monitoring of the investee. In the case of reward-based crowdfunding, monitoring primarily addresses backers’ concerns regarding opportunistic behaviors by proponents, who may solicit and accept funds by intentionally misrepresenting the nature and/or outcome of the project. Finally, the sociological literature on homophily (McPherson et al. 2001) suggests that geographical proximity breeds trust and over-optimism about transaction partners or opportunities in local areas (see e.g., Strong and Xu 2003). Similarly, Burtch et al. (2013) have found that lenders in lending-based crowdfunding prefer culturally similar and geographically proximate borrowers.

Based on the above discussion, we conclude that residents of the same geographical area as the proponent form a promising pool of potential backers who suffer from limited information asymmetries and thus are, in principle, keen to support their neighbors’ crowdfunding projects. Mobilizing this local pool is thus fundamental for proponents to achieve crowdfunding success.

2.2 Research hypotheses

We argue that mobilizing local backers is easier in areas where residents have altruistic tendencies, namely, inclinations to undertake costly actions that confer economic benefits on other individuals to help them (Fehr and Fischbacher 2003). We call this tendency of local residents local altruism. The role of altruism in mobilizing individuals to achieve a common (economic or non-economic) goal is central to the literature on collective action (Hardin 1982). Moreover, altruism has proven to positively affect participation in important crowd-based phenomena enabled by the Internet, such as Open Source software (von Krogh et al. 2012) or crowd science (Franzoni and Sauermann 2014). In reward-based crowdfunding, interviews (Zhang 2012) and surveys (Jian and Shin 2015) have shown that backers have both consumption and altruistic motives (Gerber and Hui 2013; Qiu 2013). More generally, scholars have noted that crowdfunding facilitates investment based on non-financial motives, including helping proponents and promoting their wellbeing (Lehner 2013; Ryu and Kim 2016). These motives appear to be as important as strictly financial returns (Frydrych et al. 2014). In the case of RB entrepreneurial projects, this is not surprising because backers pledge money without any (direct) monetary return based on the proponent’s promise to provide a (small) reward. Expanding on these insights, we formulate the first hypothesis.

H1

Local altruism has a positive effect on the attraction of contributions by proponents who reside in a geographical area.

We maintain that the social capital of the area where proponents reside, i.e., localized social capital (Laursen et al. 2012a, 2012b), may magnify the alleged positive effect of local altruism. Social capital is “the sum of the actual and potential resources embedded within, available through and derived from the network of relationships possessed by an individual or an organization” (Nahapiet and Ghoshal 1998, p. 243). A stream within the broader social capital literature (Payne et al. 2011) has noted that social capital exists not only at the level of individuals or organizations but also at the level of geographical areas (localized social capital, Laursen et al. 2012a), where it exerts significant effects. Scholars have indeed found that local social capital favors product innovation (Hauser et al. 2007; Laursen et al. 2012a) and expansion into international markets (Laursen et al. 2012b) by local firms. More generally, it positively relates to local economic (Putnam et al. 1993; Beugelsdijk and Van Schaik 2005) and financial development (Guiso et al. 2004a).

In the case of RB entrepreneurial projects, we expect that localized social capital strengthens the allegedly positive effect of local altruism on the attraction of contributions by proponents who reside in an area. Specifically, following the literature, we distinguish between localized relational capital—which concerns the number and intensity of social relations among people residing in an area—and localized compliance with norms—which refers to how much local residents adhere to social norms of good citizenship (Laursen et al. 2012a; see also, Putnam 1995, p. 67). In areas with high levels of localized relational capital, residents have numerous, frequent, and high-quality social relations (Laursen et al. 2012a, 2012b). Thus, proponents of RB entrepreneurial projects and their backers can count on these relations to advocate for their reliability and for project quality among altruistic residents, thus enhancing their willingness to contribute. In turn, the fact that altruistic individuals are prone to advocacy and sensitive to social pressures (Piliavin and Charng 1990) likely magnifies the effects of well-developed social networks in an area. Moreover, evidence exists that that social relations help entrepreneurs collect resources for developing and growing their ideas (see, e.g., Shane and Cable 2002). Therefore, altruistic individuals who reside in areas with high localized relational capital may envision that their contributions to RB entrepreneurial projects would not be wasted, as the proponents of these projects can attract the resources they need. This likely arouses a sense of self-efficacy in altruistic individuals, which boosts their willingness to contribute (Kuppuswamy and Bayus 2014)Footnote 3. Based on the above discussion, we formulate the following hypothesis.

H2

Localized relational capital enhances the positive effect of local altruism on the attraction of contributions by proponents who reside in a geographical area.

Finally, we envision a positive moderating effect of localized compliance with social norms. Indeed, a high level of compliance with social norms in an area breeds trust among residents and reduces the risk that they will engage in opportunistic behavior. These effects, in turn, further stimulate altruistic residents to respond to the call for funding by local proponents, as they lessen their fear of being cheated. People acting out of altruistic motives are more prone to risk-taking (Farnill and Ball 1982; Berkowitz 1987), and they tend to trust others (Piliavin and Charng 1990; Mooradian et al. 2006; Ben-Ner and Halldorsson 2010). However, we expect that being cheated arouses particularly negative feelings in them (see, e.g., Raja et al. 2011, for a similar argument). Briefly, altruistic backers would likely feel that an opportunistic proponent betrayed their generosity. Therefore, we posit that altruistic people in areas where high levels of compliance with social norms reduce the risk of opportunistic behavior are more likely to support proponents of RB entrepreneurial projects. Accordingly, we formulate the following hypothesis.

H3

Localized compliance with social norms enhances the positive effect of local altruism on the attraction of contributions by proponents who reside in a geographical area.

3 Data and methodology

3.1 Data sources and sample

This study uses information on RB entrepreneurial projects hosted on 13 Italian reward-based platformsFootnote 4, on their proponents, and on the geographical areas where these proponents reside (see “Dependent and independent variables and econometric model specifications” section for descriptions of the variables used in the empirical analysis). The data are drawn from several sources.

First, from October 16, 2012 to July 1, 2014, we monitored the 13 active Italian reward-based platforms to download information about the RB entrepreneurial projects they hosted and their proponents. We carefully read the descriptions on the project webpages to exclude projects with clear non-profit orientations. From the webpage of each RB entrepreneurial project, we downloaded information about the target capital, the starting and closing dates of the fundraising campaign, the capital collected by the end of the campaign, and whether the proponent postponed the closing date. For each project, we identified all proponents and classified them as individuals, groups of individuals (teams) or organizations. For projects proposed by individuals and teams, we also recorded the gender of each proponent.

Second, starting from the proponent biographies posted on project websites, LinkedIn or other websites, we determined the Italian province (at the NUTS3 level in the Eurostat classification) where each proponent resides. When the proponent was an organization, we considered the location of its headquarter. For these provinces, we collected information on local altruism, localized social capital, and other local characteristics, which we used as control variables. As we explain in “Dependent and independent variables and econometric model specifications” section, to build our measure of local altruism, we used information on local taxpayers from the Italian Agency of Tax Revenue (Agenzia delle Entrate). The data on localized social capital and other characteristics of Italian provinces are mainly from the Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT).Footnote 5 Other sources of data for the control variables include the Italian Association of Chambers of Commerce (Movimprese, for local entrepreneurial activity data) and the Bank of Italy (for local bank branch and bank loan data).

After cleaning the data because of missing information, the final sample consists of 618 proponents of RB entrepreneurial projects distributed across 88 Italian provinces. These proponents launched 457 projects that ended by July 1, 2014 (i.e., we selected only projects whose funding deadline had expired). The difference between the number of proponents and the number of projects occurs because of projects presented by more than one proponent (73, 16.0%).Footnote 6

Table 1 shows the distribution of the 618 proponents in our sample by type (i.e., individual male, individual female, male as part of a team, female as part of a team, and organization) and geographic location. When examining a proponent’s type, we observe that the success rate (i.e., the percentage of proponents whose project was successful out of the total number of proponents in the category) is higher for proponents that are part of a team, particularly, if the proponent is female (56.3%). Conversely, individual male proponents exhibit the lowest success rate (27.3%). Furthermore, substantial heterogeneity exists in success rates by the proponents’ location, with those located in the southern and northwestern regions having the highest success rates (43.5% and 40.6%, respectively).

Table 2 reports descriptive statistics on the 457 RB entrepreneurial projects presented by the 618 proponents in our sample. Approximately one-third of these projects (i.e., 152 of 457, 33.3%) met their target. On average, successful projects have lower target capital than unsuccessful ones, i.e., €3492 and €18,550, respectively. This difference is statistically significant at the 10% level. This weak statistical significance is due to the presence of projects with ambitious capital targets, which increased the estimated variance. Indeed, the difference becomes significant at the 1% level when two unsuccessful projects with capital targets greater than €400,000 are excluded. Table 2 highlights that 50% of unsuccessful projects raised less than €50.

3.2 Dependent and independent variables and econometric model specifications

In our econometric models, the unit of analysis is the project proponent. The dependent variable (proponent success) is the ratio of the amount of capital raised by a proponent for an RB entrepreneurial project to the target capital of this project. Clearly, this dependent variable has the same value for proponents who presented a project jointly.

The explanatory variables are measures of the level of local altruism (local altruism) and of the two dimensions of localized social capital, i.e., the network of social relations (localized relational capital) and compliance with social norms (localized norms) in the province where the proponent resides. Specifically, we compute local altruism as the percentage of taxpayers residing in the focal province who, in 2011, decided to donate 0.5% of their annual income tax—the so-called 5 per mille—to support non-profit entities that undertake socially relevant activities, such as voluntarism, sports and culture, and scientific and medical research.Footnote 7 Since 2006, upon submitting a tax declaration, each Italian taxpayer has had the option to specify an entity to which 0.5% of her/his annual tax income is reserved. Alternatively, s/he can refuse to donate 0.5% of her/his annual tax income, in which case it remains available to the public budget. In sum, a taxpayer’s decision to donate 0.5% is completely voluntary, and the choice of the entity to which to designate the sum is at her/his full discretion. We think that this variable is a suitable measure of local altruism, which complies with the definition of altruism we use in this paper (Fehr and Fischbacher 2003). Obviously, the 5 per mille generates an economic benefit for the recipient, a socially responsible or humanitarian organization that the taxpayer has consciously selected to support with part of her/his taxes. This selection is costly for the taxpayer, who has to devote time and effort to choose the entity to support. Moreover, once the selection is made, a share of these taxes is subtracted from other destinations, such as investments in schools, hospitals, infrastructure and public transport, which may indirectly produce advantages for her/him.

As for localized social capital variables, we follow the approach of Laursen et al. (2012a) and consider the two principal components derived from a principal component analysis (PCA) of the social capital measures described in Table 3.

Specifically, we include social capital measures that we expect capture compliance with social norms of good citizenship in the focal province (i.e., voter turnout and recycling). We also include two measures of participation in voluntary associations (i.e., number of non-profit organizations and volunteers of non-profit organizations) and a measure of friendship and spare-time socialization (satisfaction with relationships with friends). These latter three measures likely refer to social relations in the focal province. Table 3 presents the factor loadings associated with the two principal components extracted from the PCA. These components explain 82% of the total variance. Localized relational capital and localized norms are the first and second components derived from the factor loadings reported in Table 3, respectively. In particular, localized relational capital mostly relates to the two measures that capture participation in voluntary associations and to the satisfaction with relationship with friends, while localized norms relates to the two measures that capture compliance with social norms.

To evaluate the moderating effects of localized social capital variables on local altruism, we include the interactions local altruism × localized relational capital and local altruism × localized norms in the regressions.

We control for a number of additional factors that may affect a proponent’s ability to attract financial support from Internet users. At the proponent level, we include a dummy variable that equals 1 if the proponent is an organization (organization) and another that equals 1 if the proponent is an individual who launched her/his RB entrepreneurial project with other individuals (team). We also include a dummy variable that equals 1 if the proponent is female (female). Indeed, both the type (Colombo et al. 2015a) and gender (e.g., Marom et al. 2015) of the proponent may affect their ability to collect money through reward-based crowdfunding.

We then control for a number of project-level characteristics, which the crowdfunding literature has deemed important for success (e.g., Mollick 2014). Specifically, we include the logarithm of the target capital of the project (target capital) for which we predict a negative association with proponent success. We also include a dummy variable that equals 1 if the project description includes video (video); this captures the extent to which a proponent wants to provide information about the project and thus serves as an inverse proxy of information asymmetry between the proponents and their (potential) backers (Mollick 2014; Colombo et al. 2015a). Accordingly, we expect that it is positively related to a proponent’s ability to attract contributions. We also include a dummy variable that equals 1 if the project has extended the deadline (postponed), thus giving potential backers more time to make their contributions. Finally, we include time dummies that refer to the year in which the proponents posted their projects online. At the platform level, we consider the fact that platforms differ in terms of visibility and capacity to attract both projects and backers. Accordingly, we include the total number of projects hosted on the platform at the time of the campaign (project platform) and a set of platform dummy variables.

Furthermore, we include province-level controls that account for the characteristics of the province where the proponent resides (for a similar approach, see, e.g., Mollick 2014). First, we control for the fact that provinces are heterogeneous in the number of potential backers by including the population density of the province (local population density) in 2011. Then, we include the ratio of the number of local bank branches to the population of the province (local bank branches) and the ratio of the number of new firms to the number of active firms in the province (local entrepreneurial rate) in 2011. In provinces with many banks and where it is easy to start a business, proponents may pursue their entrepreneurial ideas without resorting to crowdfunding. Therefore, the inclusion of these two variables allows us to control for a possible selection effect: under favorable local conditions, the most promising entrepreneurial ideas likely obtain financing through traditional channels (e.g., bank lending), leaving less promising projects to seek crowdfunding. If this effect is at work, we should expect negative coefficients for both local bank branches and local entrepreneurial rate. Finally, in provinces where the level of local altruism and localized social capital are higher, there may be a greater propensity to use crowdfunding. Indeed, in these areas, potential proponents might believe that the probability of receiving financial support from their neighbors is higher and, thus, might post more projects. It is also likely that in these areas, the number of high-quality projects (i.e., those with a higher probability of meeting the target capital) is higher (merely because the total number of posted projects is higher). Therefore, a potential bias can arise in our estimates, as the allegedly positive impact of local altruism and localized social capital on proponent success may be partially due to this additional selection effect. We empirically address this issue using the total number of projects posted by proponents that reside in the focal province (local projects) as an additional province-level control.

Table 4 reports the summary statistics of the variables used in the econometric models, and Table 5 presents the correlation matrix. We performed a variance inflation factor (VIF) analysis, which suggests that multicollinearity is not a problem in our estimates. Indeed, the mean VIF is below the threshold of 5, while the maximum VIF is below the threshold of 10 (Belsley et al. 1980), as reported in Table 6.

In 123 of 618 cases (19.9%), the dependent variable, proponent success, equals zero (i.e., the proponent did not raise a single cent of funding). We test our research hypotheses through Tobit regression models. The reason for this choice is that the observed dependent variable results from a latent variable that we cannot observe: the attractiveness of a project to a potential backer. Only if this attractiveness is sufficiently high, we actually observe a contribution and, thus, a positive ratio of collected capital to target capital (i.e., proponent success >0). Therefore, not all zero values of the observed dependent variable are equal, as different levels of attractiveness can be associated with the case in which the observed variable equals zero. Under these circumstances, OLS would lead to inconsistent estimates (Cameron and Trivedi 2005). Finally, we control for the fact that observations in the same geographical area are probably not independent by clustering observations at the province level.

4 Results

In this section, we illustrate the results of the Tobit regressions. The first two columns of Table 7 show the results obtained without province-level variables (model 1) and with the inclusion of province-level control variables (model 2). In model 3, we add local altruism, and in model 4 we add the local social capital variables. In model 5, we include local altruism, localized relational capital, and the local altruism × localized relational capital interaction, while in model 6 we consider localized norms and its interaction with local altruism. Finally, in model 7, we include all variables of interest and interaction terms. To facilitate interpretation of the coefficients, continuous variables have been standardized (mean zero, unit standard deviation).Footnote 8

With respect to control variables, the results are robust across all specifications. The coefficients of organization and female are both positive and statistically significant (at the 1% and 5% levels in most estimates, respectively). When considering project-level variables, we find that, consistent with the literature, the coefficient of target capital is negative and significant at the 5% level in most estimates. Conversely, postponed is positive and significant at the 5% level. Moreover, we find that both local bank branches and local entrepreneurial rate are negatively associated with proponent success. As discussed in “Dependent and independent variables and econometric model specifications” section, this evidence suggests that in provinces with many bank branches and where it is easier to start a business, the most promising ideas likely obtain financing through traditional channels, leaving less promising projects to crowdfunding. Conversely, local population density and local projects seem to positively influence proponent success, although the statistical significance of these variables is low in some estimates.

Turning to the main explanatory variables, the results of models 3 and 4 are consistent with H1. In both cases, we find indeed a positive and significant (at 5%) coefficient of local altruism, suggesting that proponents who reside in areas with high levels of local altruism are more likely to attract backers to their projects. Specifically, in model 4, the average marginal effect (ME)Footnote 9 of local altruism on proponent success is 0.07. This implies that if a proponent proposes a project whose target capital is €100, a one standard deviation increase in the level of local altruism in the province where s/he resides leads to a €7 increase in the capital that s/he raises. Conversely, according to model 4, geographically localized social capital seems not to have a direct impact on proponent success: neither the localized relational capital nor localized norms coefficients are statistically significant. This may indicate that the social relations that link individuals in an area do not explain why a proponent succeeds in attracting money from the crowd of Internet users. We attribute the lack of such a direct effect to two main motives. First, crowdfunding is enabled by the Internet, and thus, proponents can leverage not only local networks but also long distance ones. Second, it is reasonable to expect that local social relations are useless in areas where (for whatever reason) residents are not inclined to finance entrepreneurial projects through crowdfunding.

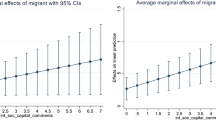

Instead, the results reported in models 5 and 7 suggest that localized relational capital positively moderates the effect of local altruism on the attraction of contributions by proponents who reside in the province. Indeed, the coefficient of the interaction term local altruism × localized relational capital is positive and statistically significant in both models (at the 5% and 1% levels in models 5 and 7, respectively). However, given the non-linear nature of the Tobit model, examining only the coefficients of the interaction terms can lead to misinterpretation of the results (Ai and Norton 2003). Hence, Fig. 1 reports the average ME of local altruism as localized relational capital varies, computed based on the coefficients of model 5. We considered increasing the values of (the standardized values of) localized relational capital from the minimum to the maximum value in the sample in increments of 0.1. The 95% confidence intervals (the dashed lines in Fig. 1) were estimated using the delta method (Oehlert 1992).

Figure 1 clearly shows that the ME of local altruism on proponent success increases as localized relational capital increases, supporting H2. Specifically, the ME of local altruism is not significant when the standardized value of localized relational capital is lower than zero (i.e., below the mean). However, when localized relational capital is at its mean (i.e., its standardized value equals zero), a one-unit increase in local altruism leads to a 0.06 increase (significant at the 5% level) of proponent success; the corresponding figure when localized relational capital is one standard deviation above the mean is 0.12 (significant at the 1% level). In other words, if a proponent proposes a project whose target capital is €100, a one standard deviation increase in the level of local altruism in the province where s/he resides leads to a €12 increase in the amount of capital that s/he raises if the level of localized relational capital is high (i.e., one standard deviation above the mean).

Conversely, local compliance with social norms does not have any (direct and/or moderating) effect, as both localized norms and its interaction with local altruism are not significant at conventional levels in either models 6 or 7. To evaluate the absence of any effect of local compliance with social norms, we performed a likelihood ratio test under the null hypothesis that model 5 (i.e., without considering the variable localized norms) is nested in model 7. As the chi-squared value for the test (with two degrees of freedom) is 3.46, we are not able to reject the null hypothesis. In other words, adding localized norms and local altruism × localized norms as predictor variables together does not result in a statistically significant improvement in the model fit. Therefore, we do not find support for H3. We interpret this unexpected result in conjunction with the finding that the presence of local banks is negatively related to proponent success. Indeed, one may wonder whether proponents who reside in geographical areas with high levels of compliance with social norms and high bank density benefit from easier access to institutional credit (Guiso et al. 2004a), which encourages proponents with promising projects to use traditional financial channels (e.g., bank lending) instead of crowdfunding. In other words, a selection effect may partially explain the non-significant effect of localized norms in our estimates and the negative effect of local bank branches. To support this conjecture, we checked whether local compliance with social norms and bank branch density are positively associated with the amount of local bank loans in the province, thus indicating easier access to traditional financial channels. Table 8 reports the results of an OLS regression where the dependent variable is the ratio of the amount of bank loans to non-financial firms to the provincial population. As the main independent variables, we considered localized norms and the local bank branches.

As is reasonable to expect, local altruism has no effect on the dependent variable: while it affects the success of RB entrepreneurial projects, it plays no role in explaining bank loans to non-financial firms. Conversely, localized relational social capital has a negative effect on bank loans. This finding suggests that in areas where intense social relations link local residents, individuals can likely count on the financial support of their families and friends, thus having less need for bank loans to finance their entrepreneurial projects.

As expected, we observe that both local compliance with social norms and the presence of local bank branches are positively associated with the total amount of local bank loans in the focal province. Both coefficients are positive and significant at the 1% level. These results complement the evidence suggesting a non-significant impact of localized norms and a negative and significant impact of local bank branches on proponent success. In provinces with high levels of compliance with social norms and high bank branch density, proponents with promising projects can likely successfully obtain bank financing instead of relying on crowdfunding as their main source of financing.

5 Robustness checks

To further validate our findings, we conduct a number of robustness checks whose results are reported in Table 9. First, we estimated a Tobit regression model clustering standard errors at the project level instead of at the province level (model A1). Second, we estimate a Probit model of the probability that the proponent reaches the target capital for her project (model A2). In other words, the dependent variable is a dummy variable that equals one if the proponent’s project is successful, i.e., the target capital is collected by the deadline. Third, we estimate a hierarchical mixed effects model with random intercepts at the NUTS3 (Italian provinces) and NUTS2 (Italian regions, model A3) levels. Furthermore, models A4, A5, and A6 report the results from Tobit regressions with additional controls for project duration, number of Facebook friends of proponents and NUTS1 area dummies, respectively. Specifically, in model A4, we consider the logarithm of the number of days between the starting and the closing date of the campaign (duration) as an additional regressor. For some projects, we were not able to detect the exact starting date, so the number of observations with respect to estimates shown in Table 7 is smaller. However, we do not detect any significant effect of duration on proponent success. In model A5, we acknowledge that the personal social contacts of proponents may affect their ability to attract contributions for their projects (e.g., Colombo et al. 2015a, 2015b). Using the proponents’ names, which we retrieved from the crowdfunding platforms on which they posted their projects, we downloaded the number of Facebook friends to obtain an individual-level measure of relational capital. We then included the variable Facebook friends, defined as the logarithm of the number of Facebook friends that a proponent had when s/he launched his or her project, in the Tobit regression. Unfortunately, this information is available only for 277 proponents in our sample. Note that we chose not to compute this variable for organizations, as they usually do not have Facebook profiles associated with friends; in cases when a profile is present, it is usually not comparable, in terms of aims and meanings, with an individual profile. Consistent with the crowdfunding literature, the coefficient of this variable is positive and statistically significant at the 5% level. Finally, we replaced the control variables at the province level with a set of geographical dummy variables at the NUTS1 level (model A6). In all the models, the results for the main explanatory variables are substantially unchanged with respect to those presented in Table 7.

6 Conclusions

This paper examines how the geographical area in which proponents reside affects their ability to finance entrepreneurial projects through reward-based crowdfunding. Specifically, it theoretically discusses and empirically shows that the level of local altruism positively influences the amount of money that proponents collect from the crowd of Internet users, while the social capital of the area magnifies this effect.

Consistent with the themes of this special issue, our work originally adds to the current debate on crowdfunding and, more generally, on entrepreneurial financing. New sources of finance for entrepreneurial ventures are currently emerging (Audretsch et al. 2016), and evidence exists that many entrepreneurs resort to crowdfunding to finance their projects. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study explicitly focusing on the factors that determine the success of RB entrepreneurial projects. In so doing, it advances our understanding of how entrepreneurs solve the seed-financing problem. Indeed, knowledge is rapidly accumulating in the entrepreneurial finance field (e.g., Adomdza et al. 2016; Hechavarría et al. 2016). Entrepreneurship journals, such as Small Business Economics, continuously publish contributions on the role of venture capital financing (e.g., Bertoni et al. 2016), bank loans (e.g., Rostamkalaei and Freel 2016), business angels (e.g., Ehrlich and Parhankangas 2014), initial public offerings (Signori and Vismara, 2016), and informal capital (e.g., Elston et al. 2016). The fact that we still know little about how entrepreneurs mobilize Internet users to engage in reward-based crowdfunding is an important limitation. Indeed, compared to equity crowdfunding and peer-to-peer lending, reward-based crowdfunding suffers less from regulatory constraints and does not require designing corporate governance mechanisms to manage a large group of equity investors. Therefore, it is an easy and widely accessible financing mechanism, which holds potential for democratizing entrepreneurs’ access to finance.

Second, this paper identifies a novel driver of success on top of those highlighted in the crowdfunding literature: the characteristics of the area where a proponent resides. In so doing, it takes a first step toward answering one of the questions raised by this special issue: What type of ecosystem is required to help crowdfunding flourish? Indeed, we identify a fundamental element of this ecosystem: the area where a proponent resides together with its altruistic people and social relations. This evidence adds to the stream of the crowdfunding research, which has documented the existence of a home bias, i.e., the tendency of financial transactions to occur between parties that are geographically close (Lin and Viswanathan 2016), even for entrepreneurs who seek capital on the Internet (Agrawal et al. 2011, 2015). In providing further support for the idea that space matters in crowdfunding, our work is consistent with contributions showing that the areas where entrepreneurs reside affect the financing of their ventures (e.g., Guiso et al. 2004a, 2004b; Michelacci and Silva 2007). Third, the paper complements prior studies on altruism in crowdfunding (Gerber and Hui 2013; Villarroel and Estrela 2015) and, more generally, crowd-based phenomena, such as Open Source software (Hertel et al. 2003) or crowd science (Franzoni and Sauermann 2014). Fourth, we contribute to conversations on social capital in crowdfunding and, in general, in entrepreneurial finance. Drawing inspiration from studies that have found that entrepreneurs’ social capital facilitates their fundraising (Shane and Cable 2002), scholars have shown that proponents’ social capital is an important driver of crowdfunding success (Mollick 2014; Colombo et al. 2015a). We add to these contributions by showing that proponents of RB entrepreneurial projects can count not only on their personal social networks but also on local social networks through which altruistic residents can access information about proponents and project quality and can convince others to contribute. Moreover, these social networks favor the identification and punishment of opportunistic behavior, reassuring altruistic neighbors that their generosity will not be betrayed. Finally, the sample of proponents we use in this paper is drawn from diverse platforms, a rarity in crowdfunding studies, which usually draw their data from a single platform (see Dushnitsky et al. 2016 for an exception).

As any research, this work has several limitations that create opportunities for future research. First, we do not know who support the RB entrepreneurial projects of proponents in our sample. In particular, we do not know whether they are local residents, how far they are from proponents, or whether they are friends or family members. In our robustness checks, we control for the number of Facebook friends. However, Facebook friendship is an imperfect measure of real friendship (Bryant and Marmo 2012), and in any case, we do not know whether Facebook friends backed the proponents’ projects. Generally, we think that future studies should make an effort to assess more directly the effect of geographical proximity, local altruism and localized social capital on the success of RB entrepreneurial projects. To this end, we encourage scholars to conduct surveys of the backers of RB entrepreneurial projects to ask them whether and how these factors played a role in their decision to support these projects. However, gathering reliable survey data on backers is very difficult. Often platforms do not provide information about backers’ identities, so researchers cannot address them in a survey simply because we do not know who they are. Moreover, collecting measures of altruism is complicated: respondents tend to exaggerate their level of altruism to present themselves as good fellows (i.e., social desirability bias). Third, to study the effect of backers’ altruism on the success of crowdfunding projects, one would have to survey not only current backers but also potential ones, who are almost impossible to identify.

Second, due to data limitations, we control only for a subset of proponent characteristics. Specifically, we do not have information on proponents’ human or social capital, which, according to the literature (Mollick 2014; Ahlers et al., 2015), should affect their success in crowdfunding. Further works analyzing how a proponent’s individual characteristics interact with those of the area where s/he resides would be interesting additions to our research. For example, are proponents with many social contacts better able to leverage local social networks to finance their RB entrepreneurial projects? In other words, is individual social capital a complement to localized social capital? Third, despite the richness of the set of project-level controls, some important independent variables are missing. In particular, Colombo et al. (2015a) found that the capital raised in the early days of an RB project predicts its success. Unfortunately, we do not have this information in our database and thus cannot answer an important question: Does local altruism help attract a critical mass of early contributions that trigger proponents’ success?

Fourth, we do not know what happens to the RB entrepreneurial projects of proponents in our sample once they succeed in attracting money from the crowd. In other words, we assess just one dimension of proponent success in financing their RB entrepreneurial projects: the raising of money from the crowd of Internet users. However, success is a multiform construct in crowdfunding (Mollick 2016). After winning the support of the crowd, do these proponents succeed in accessing venture capital or angel financing? Finally, our study focuses on Italian proponents. It would be interesting to repeat our analysis for other countries with diverse cultures. Culture influences backers’ willingness to contribute to crowdfunding projects (Burtch et al. 2014). Studying how local culture interacts with local altruism and localized social capital in determining proponents’ success would shed further light on its role in the crowdfunding realm.

Despite these limitations, this paper has interesting implications for proponents of RB entrepreneurial projects, managers of crowdfunding platforms, and policymakers. Our results suggest that proponents should leverage their neighbors, as they can play a significant role in driving their entrepreneurial initiatives toward success. This is probably more difficult in areas where the level of local altruism is low and localized social capital is limited. Proponents who reside in these areas and cannot relocate should be aware that they could not gain the most from the pool of potential local backers. Therefore, they should devote effort to advertise their projects at longer distances by taking advantage of Internet-based social networks and media. In turn, managers of crowdfunding platforms who are interested in the success of the projects posted on their platforms should consider designing tools that help proponents interact with people in the geographical areas where they reside. For instance, making a proponent’s location immediately visible on their her/his project page is likely a simple way to stimulate contributions from their neighbors. Finally, policymakers interested in crowdfunding as a way to solve the seed-financing problems of entrepreneurial projects should consider that geography plays a role in the effectiveness of this new financing mechanism. On the one hand, they should establish initiatives that promote crowdfunding in areas where local characteristics are favorable to project success; on the other hand, they can devote effort to improve altruistic attitudes and social relations in areas where these aspects are still lagging behind.

Notes

On the contributions of self-efficacy to crowd-based phenomena, see Hertel et al. (2003).

Bookabook (http://bookabook.it), Boomstarter (http://boomstarter.it), Crowdfundme (http://www.crowdfundme.it), Crowdfunding-Italia (http://www.crowdfunding-italia.com), DeRev (https://www.derev.com), Eppela (http://www.eppela.com), Ginger (http://www.ideaginger.it), H2RAISE (http://www.h2raise.it), Kendoo (http://www.kendoo.it), MusicRaiser (http://www.musicraiser.com), Produzioni Dal Basso (https://www.produzionidalbasso.com), Starteed (http://www.starteed.com), and TakeOff Crowdfunding (http://www.takeoffcrowdfunding.com). For an overview of the Italian crowdfunding market, see Giudici et al. (2013).

For additional details on the sources of information used to build our social capital measures, please see Table 3 in “Dependent and independent variables and econometric model specifications” section.

If the same individual (or organization) presented more than one crowdfunding project, we consider her/him (or it) a distinct proponent for each project. The proponent is therefore defined as the individual (or organization) that presented a given crowdfunding project. In other words, two proponents can refer to the same individual presenting two different projects.

For instance, these entities include universities, hospitals, and cultural associations. Note that taxpayers may change the entities to which they donate their 5 per mille every year.

The interaction terms were formed based on the standardized values of the abovementioned variables.

The average ME is the average increase in proponent success in our sample due to a one-unit increase in the variable of interest. As all regression variables have been standardized, a one-unit increase corresponds to a one standard deviation increase. It is worth noting that the coefficients reported in Table 7 represent the MEs on the latent variable (attractiveness), but they cannot be directly interpreted as the MEs on the observed variable (proponent success). Given the non-linear nature of the Tobit model, average MEs on proponent success are obtained by calculating the ME for each observation in the sample and then averaging the computed MEs.

References

Adomdza, G. K., Åstebro, T., & Yong, K. (2016). Decision biases and entrepreneurial finance. Small Business Economics, 47(4), 819–834.

Agrawal, A., Catalini, C., & Goldfarb, A. (2011). The geography of crowdfunding. National bureau of economic research (No. w16820).

Agrawal, A., Catalini, C., & Goldfarb, A. (2015). Crowdfunding: geography, social networks, and the timing of investment decisions. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 24(2), 253–274.

Ahlers, G. K., Cumming, D., Günther, C., & Schweizer, D. (2015). Signaling in equity crowdfunding. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(4), 955–980.

Ai, C., & Norton, E. C. (2003). Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Economics Letters, 80(1), 123–129.

Allison, T. H., Davis, B. C., Short, J. C., & Webb, J. W. (2015). Crowdfunding in a prosocial microlending environment: examining the role of intrinsic versus extrinsic cues. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(1), 53–73.

Audretsch, D. B., Lehmann, E. E., Paleari, S., & Vismara, S. (2016). Entrepreneurial finance and technology transfer. Small Business Economics, 41(1), 1–9.

Belleflamme, P., Lambert, T., & Schwienbacher, A. (2013). Individual crowdfunding practices. Venture Capital, 15(4), 313–333.

Belsley, D. A., Kuh, E., & Welsch, R. E. (1980). Regression diagnostics: identifying influential data and sources of collinearity. New York, NY: Wiley.

Ben-Ner, A., & Halldorsson, F. (2010). Trusting and trustworthiness: what are they, how to measure them, and what affects them. Journal of Economic Psychology, 31(1), 64–79.

Berkowitz, B. (1987). Local heroes: the rebirth of heroism in America. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Bertoni, F., D’Adda, D., & Grilli, L. (2016). Cherry-picking or frog-kissing? A theoretical analysis of how investors select entrepreneurial ventures in thin venture capital markets. Small Business Economics, 46(3), 391–405.

Beugelsdijk, S., & Van Schaik, T. (2005). Social capital and growth in European regions: an empirical test. European Journal of Political Economy, 21(2), 301–324.

Boschma, R. (2005). Proximity and innovation: a critical assessment. Regional Studies, 39(1), 61–74.

Bryant, E. M., & Marmo, J. (2012). The rules of Facebook friendship. A two-stage examination of interaction rules in close, casual, and acquaintance friendships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 29(8), 1013–1035.

Burtch, G., Ghose, A., & Wattal, S. (2013). An empirical examination of the antecedents and consequences of contribution patterns in crowd-funded markets. Information Systems Research, 24(3), 499–519.

Burtch, G., Ghose, A., & Wattal, S. (2014). Cultural differences and geography as determinants of online pro-social lending. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 38(3), 773–794.

Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (2005). Microeconometrics: methods and applications. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge university press.

Colombo, M. G., Franzoni, C., & Rossi-Lamastra, C. (2015a). Internal social capital and the attraction of early contributions in crowdfunding. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(1), 75–100.

Colombo, M. G., Franzoni, C., & Rossi-Lamastra, C. (2015b). Cash from the crowd. Science, 348(6240), 1201.

Dushnitsky, G., Guerini, M., Piva, E., & Rossi-Lamastra, C. (2016). Crowdfunding in Europe: determinants of platform creation across countries. California Management Review, 58(2), 44–71.

Ehrlich, M., & Parhankangas, A. (2014). How entrepreneurs seduce business angels: an impression management approach. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(4), 543–564.

Elston, J. A., Chen, S., & Weidinger, A. (2016). The role of informal capital on new venture formation and growth in China. Small Business Economics, 46(1), 79–91.

Farnill, D., & Ball, I. L. (1982). Sensation seeking and intention to donate blood. Psychological Reports, 51(1), 126.

Fehr, E., & Fischbacher, U. (2003). The nature of human altruism. Nature, 425, 785–791.

Forman, C., Goldfarb, A., & Greenstein, S. (2005). How did location affect adoption of the commercial internet? Global village vs. urban leadership. Journal of Urban Economics, 58(3), 389–420.

Franzoni, C., & Sauermann, H. (2014). Crowd science: the organization of scientific research in open collaborative projects. Research Policy, 43(1), 1–20.

Frydrych, D., Bock, A. J., Kinder, T., & Koeck, B. (2014). Exploring entrepreneurial legitimacy in reward-based crowdfunding. Venture Capital, 16(3), 247–269.

Gerber, E. M., & Hui, J. (2013). Crowdfunding: motivations and deterrents for participation. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI), 20(6), 34:1–32.

Giudici, G., Guerini, M., & Rossi-Lamastra, C. (2013). Crowdfunding in Italy: state of the art and future prospects. Economia e Politica Industriale-Journal of Industrial and Business Economics, 40(4), 173–188.

Gleasure, R., & Feller, J. (2016). Does heart or head rule donor behaviors in charitable crowdfunding markets. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 20(4), 499–524.

Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2004a). The role of social capital in financial development. The American Economic Review, 94(3), 526–556.

Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2004b). Does local financial development matter. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(3), 929–969.

Hardin, R. (1982). Collective action. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future.

Hauser, C., Tappeiner, G., & Walde, J. (2007). The learning region: the impact of social capital and weak ties on innovation. Regional Studies, 41(1), 75–88.

Hechavarría, D. M., Matthews, C. H., & Reynolds, P. D. (2016). Does start-up financing influence start-up speed? Evidence from the panel study of entrepreneurial dynamics. Small Business Economics, 46(1), 137–167.

Hertel, G., Niedner, S., & Herrmann, S. (2003). Motivation of software developers in Open Source projects: an Internet-based survey of contributors to the Linux kernel. Research Policy, 32(7), 1159–1177.

Hornuf L., & Schmitt, M. (2016). Does a local bias exist in equity crowdfunding? The impact of investor types and portal design. Max Planck Institute for Innovation and Competition Research Paper No. 16–07.

Hortaçsu, A., Martínez-Jerez, F. A., & Douglas, J. (2009). The geography of trade in online transactions: evidence from eBay and mercadolibre. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 1(1), 53–74.

Jian, L., & Shin, J. (2015). Motivations behind donors’ contributions to crowdfunded journalism. Mass Communication and Society, 18(2), 165–185.

Kuppuswamy, V., & Bayus, B. L. (2014). Crowdfunding creative ideas: the dynamics of project backers in Kickstarter. UNC Kenan-Flagler Research Paper (2013–15).

Laursen, K., Masciarelli, F., & Prencipe, A. (2012a). Regions matters: how localized social capital affects innovation and external knowledge acquisition. Organization Science, 23(1), 177–193.

Laursen, K., Masciarelli, F., & Prencipe, A. (2012b). Trapped or spurred by the home region? The effects of potential social capital on involvement in foreign markets for goods and technology. Journal of International Business Studies, 43(9), 783–807.

Lehner, O. M. (2013). Crowdfunding social ventures: a model and research agenda. Venture Capital, 15(4), 289–311.

Lerner, J. (1995). Venture capitalists and the oversight of private firms. The Journal of Finance, 50(1), 301–318.

Lin, M., & Viswanathan, S. (2016). Home bias in online investments: an empirical study of an online crowdfunding market. Management Science, 62(5), 1393–1414.

Marom, D., Robb, A., & Sade, O. (2015). Gender dynamics in crowdfunding (Kickstarter): evidence on entrepreneurs, investors, deals and taste-based discrimination. SSRN Working Paper. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2442954. Accessed 3 Jan 2017.

McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Cook, J. M. (2001). Birds of a feather: homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 415–444.

Mendes-Da-Silva, W., Rossoni, L., Conte, B. S., Gattaz, C. C., & Francisco, E. R. (2016). The impacts of fundraising periods and geographic distance on financing music production via crowdfunding in Brazil. Journal of Cultural Economics, 40(1), 75–99.

Michelacci, C., & Silva, O. (2007). Why so many local entrepreneurs. Review of Economics and Statistics, 89(4), 615–633.

Mollick, E. R. (2014). The dynamics of crowdfunding: an exploratory study. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(1), 1–16.

Mollick, E. R. (2016). Containing multitudes: the many impacts of Kickstarter funding. SSRN Working Paper. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2808000. Accessed 3 Jan 2017.

Mooradian, T., Renzl, B., & Matzler, K. (2006). Who trusts? Personality, trust and knowledge sharing. Management Learning, 37(4), 523–540.

Morgan, K. (2004). The exaggerated death of geography: learning, proximity and territorial innovation systems. Journal of Economic Geography, 4(1), 3–21.

Nahapiet, J., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23(2), 242–266.

Oehlert, G. W. (1992). A note on the delta method. The American Statistician, 46(1), 27–29.

Ordanini, A., Miceli, L., Pizzetti, M., & Parasuraman, A. (2011). Crowd-funding: transforming customers into investors through innovative service platforms. Journal of Service Management, 22(4), 443–470.

Payne, G. T., Moore, C. B., Griffis, S. E., & Autry, C. W. (2011). Multilevel challenges and opportunities in social capital research. Journal of Management, 37(2), 491–520.

Piliavin, J. A., & Charng, H. W. (1990). Altruism: a review of recent theory and research. Annual Review of Sociology, 16, 27–65.

Putnam, R. D. (1995). Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. Journal of Democracy, 6(1), 65–78.

Putnam, R. D., Leonardi, R., & Nanetti, R. Y. (1993). Making democracy work: civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Qiu, C. (2013). Issues in crowdfunding: theoretical and empirical investigation on Kickstarter. Available at SSRN 2345872. http://ssrn.com/abstract=2345872. Accessed 3 Jan 2017.

Raja, U., Johns, G., & Bilgrami, S. (2011). Negative consequences of felt violations: the deeper the relationship, the stronger the reaction. Applied Psychology, 60(3), 397–420.

Rostamkalaei, A., & Freel, M. (2016). The cost of growth: small firms and the pricing of bank loans. Small Business Economics, 46(2), 255–272.

Ryu, S., & Kim, Y. G. (2016). A typology of crowdfunding sponsors: birds of a feather flock together? Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 16, 43–54.

Shane, S., & Cable, D. (2002). Network ties, reputation, and the financing of new ventures. Management Science, 48(3), 364–381.

Signori, A., & Vismara, S. (2016). Stock-financed M&As of newly listed firms. Small Business Economics. Forthcoming. doi:10.1007/s11187-016-9767-0.

Strong, N., & Xu, X. (2003). Understanding the equity home bias: evidence from survey data. Review of Economics and Statistics, 85(2), 307–312.

Villarroel, J. A., & Estrela, F. (2015). Investor motivation in crowdfunding: helping self or helping others? Paper presented at the R&D Management Conference 2015, Pisa, 23–26 June.

Villarroel, J. A., & Pinto, V. (2014). Crowdfunding: religiosity and pro-social behavior. Academy of Management Proceedings.

Vismara, S. (2016a). Equity retention and social network theory in equity crowdfunding. Small Business Economics, 46(4), 579–590.

Vismara, S. (2016b). Information cascades among investors in equity crowdfunding. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. doi: 10.1111/etap.12261.

von Krogh, G., Haefliger, S., Spaeth, S., & Wallin, M. W. (2012). Carrots and rainbows: motivation and social practice in open source software development. MIS Quarterly, 36(2), 649–676.

Wang, Y., Lai, P., & Sui, D. (2003). Mapping the Internet using GIS: the death of distance hypothesis revisited. Journal of Geographical Systems, 5(4), 381–405.

Younkin, P., & Kashkooli, K. (2016). What problems does crowdfunding solve? California Management Review, 58(2), 20–43.

Zhang, Y. (2012). An empirical study into the field of crowdfunding. Master thesis of Lund University School of Economics and Management. https://lup.lub.lu.se/student-papers/search/publication/3049774. Accessed 3 Jan 2017.

Acknowledgements

We presented earlier drafts of this paper at the XXV Annual Scientific Meeting of the Associazione Italiana di Ingegneria Gestionale in Bologna (Italy), October 16–17, 2014, the “Economics of Entrepreneurship and Innovation” workshop, June 2–3, 2015, in Trier (Germany), and the Third Crowdinvesting Symposium, October 23, 2015, in Munich (Germany). The authors thank their colleagues at these conferences for their helpful suggestions. The authors are also grateful to Vincenzo Butticè, Massimo G. Colombo, and Chiara Franzoni, who provided useful comments on earlier versions of the paper. Moreover, they wish to thank the two anonymous referees and the guest editors of the special issue for their insightful and constructive comments, which proved to be very helpful in developing the final version of the paper. Francesca Tenca, Paola Rovelli, and Gianluca Grassi provided excellent research assistance in collecting data. Responsibility for any error rests solely with the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Giudici, G., Guerini, M. & Rossi-Lamastra, C. Reward-based crowdfunding of entrepreneurial projects: the effect of local altruism and localized social capital on proponents’ success. Small Bus Econ 50, 307–324 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9830-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9830-x

Keywords

- Reward-based crowdfunding

- Crowdfunding of entrepreneurial projects

- Local altruism

- Localized social capital