Abstract

Drawing upon data from the 2007 UK Survey of SME Finance, the current analysis is concerned with the extent to which growth firms are discriminated on price in loan markets, or, more simply, the extent to which growth firms pay more for credit. Given relatively small turndown rates historically (Vos et al. in J Bank Finance 31(9):2648–2672, 2007), higher credit prices may be a more substantial growth constraint than the access to finance issues that have dominated the academic literature to date. To this end, we observe, inter alia, that firms who have recorded recent high growth are more likely to pay higher interest rates for the loan they obtained. Moreover, small-sized firms who intend to grow through the introduction of new products exhibit a higher probability of paying more for credit than their peers. Finally, acknowledging that banks are not risk funders, we discuss the potential policy implications of these findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

It has long been recognised that a small group of high growth firms create the bulk of the net new jobs in an economy. These are Storey’s (1998) “ten percenters” or Birch’s (1990) “gazelles”. Unsurprisingly, these firms have been the focus of considerable academic research (Henrekson and Johansson 2010) and policy attention (Hoffman 2007). Indeed, informed recent debate has focused on the merits of further shifting the emphasis of entrepreneurship policy away from the creation of new ventures to the support of high growth firms (cf. Shane 2009; Mason and Brown 2011). This view is consistent with recent evidence that suggests that the presence of “ambitious entrepreneurship” is a stronger predictor of macroeconomic growth than entrepreneurial activity in general (Stam et al. 2007). In this light, identifying and supporting growth firms are key priorities.

Much of the extant academic research has been concerned with the characteristics of growing firms (Barringer et al. 2005; Baum et al. 2001) or with the (often institutional) determinants of growth (Davidsson and Henrekson 2002; Barkham et al. 2012). Less attention has been paid to the issue of barriers to growth, that is to the obstacles faced by firms, as they expand rapidly (Lee 2013). However, an important subset of barriers that has received attention relates to finance (Becchetti and Trovato 2002; Beck et al. 2005; Beck and Demirguc-Kunt 2006). In general, this line of research has explored the extent to which limits to access to various forms of external finance constrain the growth of smaller firms. A prominent finding in this literature is that growth firms are likely to be less successful loan applicants (e.g. Freel 2007). Failure, from this perspective, is typically defined in terms of simple loan turndowns or loan scaling such that growth firms are more likely to receive either no loan or a smaller amount than applied for. These firms are credit-rationed: that is, assuming that these growth firms are otherwise observationally indistinct from successful applicants, banks are rationing credit on some basis other than price.

However, whilst growth firms may disproportionately face turndowns or loan scaling, it still remains that the majority receive the loans they apply for (Vos et al. 2007). In these cases, it is the terms of the loans which are of interest. In particular, if growing firms are shown to pay systematically higher prices for debt, then this may be of greater concern than the smaller numbers who are credit-rationed. Whilst higher price may reflect higher risk, higher loan prices may also hinder firm development, as the resources required to invest in growth are diverted to the loan provider. This question is the focus of the current study. Drawing on data from the 2007 UK Survey of SME Finance (Cosh et al. 2008), we model the price firms paid for variable rate loans. Our models contain information both on past growth and on future growth intentions, including the proposed growth strategies. We find evidence that both past growth and future growth intention, conditional on strategy, associate with higher loan prices.

The manuscript is structured as follows: Section 2 briefly reviews the literature on bank financing of small firms, with particular emphasis on growth firms, and develops three hypotheses that link loan pricing and firm growth. Section 3 describes our data. Section 4 elaborates on our models and modelling choices. Section 5 presents our empirical results. And Sect. 6 offers concluding remarks, drawing out initial implications for entrepreneurs and policymakers.

2 Literature review

In accessing bank finance, compared to large and established companies, small firms are disadvantaged by their information opacity, the relative scarcity of collateralisable assets, and disproportionately high monitoring costs (Beck and Demirguc-Kunt 2006; Berger and Udell 1998). For start-ups, lack of credit history and high rates of failure also contribute to their unfavourable situations. In consequence, the small firm sector has long been thought to be subject to credit rationing (Parker 2002; Stiglitz and Weiss 1981; Vos et al. 2007, among many): a situation in which some borrowers are denied credit or receive a lower amount of credit than they applied for. An important condition holds that these firms are, in all other respects, indistinguishable from those who have received (full) credit (Parker 2002). In such a situation, a firm is known as credit-rationed. It does not receive the money it requested despite being willing to pay a higher interest rate (de Meza 2002). In short, banks are seen to ration credit on some basis other than price.

In practice, credit institutions use a variety of techniques to distinguish between good and bad borrowers, employing different contract terms such as higher pricing, collateralisation, and sub-optimal loan sizes (Parker 2002). If banks were to use similar contract terms, employing a pooled interest rate for all types of borrowers, good borrowers would likely either exit the loan market (Parker 2002; Stiglitz and Weiss 1981) or subsidise lower-quality borrowers (de Meza 2002). Using different contract terms is a means to reveal the types of borrowers (Parker 2002) and to recognise varying risks of default. For example, collateral is perceived as a sign of entrepreneurs’ commitment and confidence in their success. The willingness to secure a loan with collateral, frequently through personal asset, acts as a positive signal to banks about the qualities of the entrepreneur as a good borrower (Berger and Udell 1998; Binks and Ennew 1996). In the presence of such instruments, and accounting for borrower heterogeneity, there is limited evidence of broad-based credit rationing in the small firms’ literature (Freel 2007). However, the absence of credit rationing does not necessarily entail the absence of discrimination. Indeed, given differing risk profiles attendant upon varying firm characteristics and strategies, banks must inevitably discriminate one firm from another in terms of contracts they offer for credit. In this case, banks seek to ration credit on the basis of price and price-related characteristics.

Firm strategy and performance are principal sources of borrower heterogeneity that may bear upon risk. As noted above, only a small proportion of small firms make much of a contribution to net job creation, innovation, or increased productivity (Shane 2009; OECD 2013, 60). Due to their importance, small growing firms have been the subject of numerous studies aiming to describe the growth cycle and to identify the factors supporting or impeding growth (Dobbs and Hamilton 2007). Financial structure and access to finance at the time of growth are common themes in these studies. Of course, access to finance does not directly cause growth, but credit constraints may affect growth by suppressing it (Binks and Ennew 1996; Vickery 2008), or forcing managers to rely on internal funds as a source of growth investment (Rahaman 2011). Internal sources of financing, often personal wealth or retained earnings, are typically the first option of an entrepreneur (Vos et al. 2007; Berger and Udell 1998). However, internal sources are likely to be limited and this limitation may act to constrain the growth of the firm (Beck and Demirguc-Kunt 2006). Indeed, Rahaman (2011) shows that as external financial constraints lessen, firms switch from internal to external funds as a means to finance growth. Moreover, these patterns of transition from internal to external funding are most pronounced in small unquoted companies (Rahaman 2011). These firms are more likely to be financially constrained and to face information problems. However, there is likely to be an important complementarity between internal and external finance: “Access to internal sources of finance may play the twin roles of proxying for internal financial capacity as well as providing a signal about the quality of future growth opportunities. Such signals, in turn, reduce the external financial constraint” (Rahaman 2011, p. 723). In short, small growing firms are eventually likely to view external sources of finance as a complement to internal sources and to increasingly use external sources to fund growth. Crucially, of these external sources, banks are consistently identified as the primary provider of external funds for small firms (Robb and Robinson 2014).

In this vein, for instance, Beck et al. (2005), based on data from a firm-level survey conducted by the World Bank, find that financial obstacles are perceived as the most important barriers to growth. The identified barriers largely revolve around bank finance and include: the provision of collateral, the bureaucratic procedures of banks, the social networks of borrowing, and the price of finance. In other studies, perceived financing constraints are also shown to have a positive association with growth intention (Binks and Ennew 1996; Nitani and Riding 2013). Firms intending to grow expect to encounter more problems than firms which actually experienced growth. That is, growing firms (who are often smaller and younger firms) anticipate that lack of credit history and an established relationship with banks will result in tighter credit availability (Binks and Ennew 1996).

Consistent with the perception of finance as a barrier to growth, recent empirical research has provided evidence that growth firms are more likely to have their loan applications refused (Riding et al. 2012), face loan scaling (Freel 2007), and identify themselves as discouraged borrowers (Freel et al. 2010). Typical rationalisation of these findings focuses on the higher risk associated with growth firms. However, despite this risk, most loan applicants go on to successfully borrow all or some of the money they sought. For instance, using data from the US National Survey of Small Business Finance, Levenson and Willard (2000) estimated that only 6 % of firms “had an unfulfilled desire for credit”, of which 2 % were actually denied funding and 4 % were discouraged from applying. More specifically, Vos et al. (2007) observed that fast growing small firms in the UK and USA, respectively, applied for and obtained more sources of financing than non-growth firms. It follows that, if most applicants are successful, the focus of the discussion should shift from credit access to terms of credit. Central to credit terms are the prices firms pay for their loans.

To the extent that higher loan prices reflect higher borrower risk (Berger and Udell 2003; Berger et al. 2005), one would anticipate growth firms facing higher loan rates. Firm growth implies change: change in, inter alia, employment, sales, market share, or assets. Rapid growth implies rapid change. These changes occur over a specific period of time (Dobbs and Hamilton 2007), and research has shown small firm growth to be episodic (Brush et al. 2009). In other words, growth is a temporary and dynamic phase that many firms experience (Nightingale and Coad 2014), and growing firms undertake several alterations in their business processes and products. Not only is the outcome of these changes uncertain, but the pace of change makes it more difficult for banks and credit institutions to monitor growing firms and evaluate their performance (Binks and Ennew 1996). Past research has shown that the price of obtaining funds rises as the valuation of the firm becomes less straightforward for its investors (Strahan 1999). In this way, the increased levels of information asymmetry attached to growing firms increase their risk and consequently the financial constraints they face (Beck and Demirguc-Kunt 2006; Beck et al. 2005; Binks and Ennew 1996; Nitani and Riding 2013). Higher loan price, reflecting higher risk (Strahan 1999), may be a key manifestation of financial barriers for growth-oriented entrepreneurs.

The foregoing leads us to two linked hypotheses:

H1

Firm which experienced growth in the near past pay higher interest rates on loans.

H2

Firms which intend to grow in near future pay higher interest rates on loans.

Small firms may take a variety of paths to growth (Garnsey et al. 2006). The variety in paths is likely to be underpinned by variety in strategy. Importantly, the various growth strategies that entrepreneurs take impose different levels of additional risk to their firms. For example, Wiklund and Shepherd (2005) report research that suggests that “tried-and-true” strategies lead to higher mean performance, whilst risky strategies—with higher performance variety—may lead to both greater individual successes and more frequent failures. This is consistent with the view that innovation only spurs growth in a “handful of ‘superstar’ fast growth firms” (Coad and Rao 2008), whilst for the bulk of firms innovative investments lead to zero or negative returns.

To the extent that banks primarily provide non-syndicated commercial loans to small businesses (Berger and Udell 2003), banks are not providers of risk capital. That is, banks do not share in the upside gain of spectacular growth. Accordingly, the greater risk of failure is likely to bear on the lending decision and on the price of the loan, more than the prospect of dramatic success. In this vein, Freel (2007) provides evidence that innovators were less likely to get access to all of the funds they seek from their banks (i.e. to face loan scaling). Similarly, Nitani and Riding (2013) find that costs of borrowing are higher for R&D intensive firms. In short, the foregoing leads us to anticipate that firms seeking to grow through innovation will face higher borrowing costs than firms seeking to expand by simply doing “more of the same”.

H3

Loan pricing is related to growth modes such that more aggressive growth strategies will associate with higher interest rates and safer strategies will be associated with lower interest rates.

3 Data and methodology

The data used in this study are a sub-sample drawn from the 2007 UK Survey of SME Finance (Cosh et al. 2008). Since the data were collected in autumn 2007, we anticipate that our results are not greatly influenced by the major changes in banking environment starting from December 2008 in the USA. However, we reflect upon the implications of the timing of the study in our concluding remarks. Respondents to the survey were owners or managers of firms, excluding public and not-for-profit organisations, with less than 250 employees or/and £35 million turnover. The initial sample was provided by Dun and Bradstreet with more than 82,000 firms. However, after considering the survey criteria, survey quota, and accessibility, around 25,000 firms were contacted. The response rate was 10 %. This response rate might increase the risk of sampling bias; however, the proportion of responses is the same across all sizes of companies (Cosh et al. 2008). Testing for non-response bias was not possible. In addition, weighting the respondents based on size, sector, and region and comparing them with breakdown of 4.3 million businesses in the UK show that firms with zero employees represent relatively less than population statistics. We bear these limitations in mind for interpretation of our results. The survey collected information on a variety of financial tools firms had been using (within the 3 years prior to the survey date) for business purposes including largest single outstanding loan. For these loans, data on interest rate and other terms of contract were collected.

The survey includes 2500 firms; however, for the purpose of this study, 247 firms are the focus. These are the firms which use banks’ commercial loans and mortgages, with variable interest rate, at the time of data collection. Interest rates incorporate elements of both the prevailing riskiness of the economic environment and the perceived (or measured) riskiness of the individual borrower. By focusing only on variable rates loans, we hope to control for the former and address only the latter. Variable interest rates comprise of a base rate plus some premium above base.Footnote 1 The former may be thought to capture the economic conditions at any given time, whilst the latter addresses the riskiness of the entrepreneur or firms. By focusing on the premium paid over the base rate, variations in absolute rates that may reflect different underlying economic conditions at the time of loan granting are largely controlled for. Crucially, whilst our loans were all outstanding on the survey date, they were not all awarded contemporaneously. The survey collected data on the premium paid over the base rate, rather than the final interest rate. We hold that changes in rate premiums largely reflect the dynamics of the lending environment and firm-level characteristics, and much less the underlying economic conditions. Unlike several studies (Binks and Ennew 1996; Beck and Demirguc-Kunt 2006; Beck et al. 2005; Vos et al. 2007) regarding financial constraints or loan pricing, our research deals with an objective measure of higher or lower price.

In contrast to variable rates, and to the extent that they do not vary over time, fixed rates are likely to reflect borrower riskiness and economic conditions only at the time at which they were awarded. Accordingly, fixed loan rates for loans awarded at different times are not directly comparable. We set them aside in the current analyses.Footnote 2

3.1 Dependent variable

In constructing our dependent variable, we use a survey question that asks respondents the rate they paid for their largest outstanding bank loan. The questions were only directed at those firms who reported using bank loan and mortgage facilities at the time of data collection (around 25 % of sample firms). Of these, 41 % provided information on the variable interest rate. The remainder held fixed rate loans. Firms holding variable rate loans were offered a categorical response variable, which expressed the rate in percentage points above base. Specifically, firms could indicate the rate they paid in one of the seven rate ranges. The lowest range was 0–2 %; thereafter, the next four categories increased by 2 % points at a time. The two final categories indicated variable interest rate in the ranges of 10–15 % and more than 15 % over the prevailing base rate. However, no firms reported paying more than 10 % over base rate.

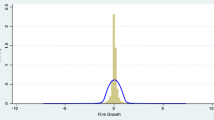

Figure 1 represents the distribution of contracted rate premiums in the sample. The majority of loans falls in the first category of 0–2 % premium rate (57 %), followed by the second category of 2–4 % (33 %). Because of the small number of observations for premium rates of more than 4 %, we recoded all these categories into one category. Accordingly, our final dependent variable has three orderings: 0–2 %, 2.01–4 %, and >4 %. The ordered nature of our dependent variable is reflected in our choice of analytical method—ordered probit—which we outline below.

3.2 Independent variable

Our independent variables are constructed to allow us to test hypotheses 1–3. Accordingly, they are concerned with growth and growth strategies. To this end, the data allow us to construct three measures of growth. In the first instance, and in line with H1, we focus on the growth history. Firms are considered to experience past growth if respondents declared they experienced 30 % increase in sales turnover for each of the 3 years preceding the survey date.Footnote 3 This is a fairly high threshold, and these growth firms may reasonably be thought of as “supergrowth” firms (Delmar et al. 2003). In practical terms, these high growth firms were coded 1, with all other firms coded as 0.

To address H2, our second independent variable focuses on growth aspirations. The relevant survey question captures the owner-managers’ growth intention over the 3 years subsequent to 2007. Owner-managers’ growth intentions are not trivial in distinguishing between actual growers and non-growers. Indeed, there is a longstanding view that “one of the most important factors [in influencing growth] is the commitment of the leader of the company to achieving growth” (Smallbone et al. 1995, p. 59). In this instance, respondents were asked whether they planned for their firm to “grow substantially”, “grow moderately”, “stay the same”, or “become smaller”. We coded firms intending to grow substantially or moderately as 1. Respondents who indicated that they wished their firms to stay the same size or to become smaller were coded as 0.Footnote 4

However, since questions relating to growth intentions are likely to be prone to both a normative bias and the over-optimism of the entrepreneurs, we also focus on specific growth strategies. By this means, we investigate our third hypothesis. To this end, the survey included a question on how firms intended to grow (directed only to those firms indicating a growth intention). Specifically, the question identifies four possible growth strategies: “move into new markets”, “introduce new products or services”, “increase sale with existing products and services”, and “hire more employees”. These strategies are not mutually exclusive and firms could indicate all, some, or none. In line with our stated hypothesis, we consider “new market” and “new products or services” to be higher-risk, more aggressive strategies, whilst “sales of existing product” and “hiring more employees” are lower-risk, less aggressive strategies. In each case, firms indicating the intention to follow one of the strategies were coded 1; otherwise, firms were coded 0. This results in 4 binary dummy variables that are entered into the models. Respondents had the option to add to these strategies, but because of small number of observations those responses are excluded from the analyses.

In addition to the variables that allow us to directly test our hypotheses, we also estimate models incorporating a “supergrowth” variable. This variable was defined by the survey investigators (Cosh et al. 2008) such that firms characterised as “supergrowth” experienced more than 30 % increase in turnover each of the 3 years prior to the survey and intend to sustain the growth moderately or substantially over the 3 years subsequent to the survey. This measure reflects the past and future orientation of the firms, excluding start-ups (firms in business for <2 years). In essence, this variable is an interaction term between realised past growth and future growth intentions.

3.3 Control variables

In modelling small firm loan prices as a function of our independent variables, it is important to control for other influences on price. These are likely to be factors which lower or raise perceived risk. Two factors, in particular, are commonly considered in the empirical literature: the role of collateral and relational lending. Credit institutions consider collateral as a positive signal that alleviates lending constraints by reducing information asymmetries or default risks (Berger and Udell 1998; Parker 2002). The information asymmetry between banks and entrepreneurs retards banks’ ability to distinguish between good and bad entrepreneurs. However, the entrepreneur, aware of their situation, and trying to avoid imperilling their assets, increases their effort to succeed. Strahan (1999) argues that collateral makes post-investment monitoring activities easier but does not affect the price, and the riskiness of a firm is reflected in the price it pays. Whilst pledging collateral may not necessarily lower the risk (price) for growth firms, it is not an unambiguous merit (Binks and Ennew 1996). That is, as the risks of these firms increase, the gap between the banks’ valuation of the assets (at the time of probable default) and the costs of obtaining those assets from the firm rises. Hence, growing small firms, comparing to other small firms, are more prone to under-evaluation of their assets or “inadequate collateral”. To mitigate this problem and respond to growing firms’ increasing demands for funds, banks may rely on relationship lending (Binks and Ennew 1996).

The severity of information opacity can be mitigated by relational lending. Relationships allow banks to gather information about the firm and entrepreneur over time and to shift the emphasis of lending decisions from hard to soft criteria (Beck and Demirguc-Kunt 2006). This reduced problem of information asymmetry may translate into greater access to bank finance at lower prices (Binks and Ennew 1996). However, there is no general consensus about the effect of relationship banking. Sharpe (1990) suggests that banks, relying on the fact that firms are locked in, internalise the benefits of the relationship. Peterson and Rajan (1994) conclude that there is no significant association between length of lending relationship and lower interest rate, excepting an insignificant effect where the bank also provides other financial services to the firm. Moreover, loan pricing may also exhibit a cyclical pattern. That is, when firms switch to new banks, interest rate decreases in order to lock in the new customers. However, after a while, firms are charged the same price that they should have paid if they had stayed with their initial bank (Ioannidou and Ongena 2010) or an even higher price to compensate the early subsidies (Kim et al. 2012). Finally, when banks collect enough information about the firm’s performance, the interest rate decreases again (Kim et al. 2012).

Yet, despite the equivocal literature, the provision of collateral and the existence of longer-term relationships are likely to be important control variables in loan pricing models. In our model, these two variables are part of a set of controls intended to capture important aspects of the loan contract. Collateral is measured as a simple dummy variable taking the value 1 if the firm was asked to provide collateral in securing the loan, and 0 otherwise. Relationship banking is proxied by the length of relationship with the firm’s primary bank. This information was captured categorically, with the smallest category indicating a banking relationship of 0–3 years. Firms in this category were coded 0, indicating no relationship banking; otherwise, firms were coded 1.

In addition to these 2 variables, we also include indicators of the purpose of the loan and of the source of the loan. In the first instance, we are able to observe whether the intended use of the loan was for working capital or for the purchase of assets. Physical asset, purchased with a loan, can have a similar function as collateral (Berger and Udell 1998) and imply lower risk. We code loans sought for the purchase of physical assets as 1; otherwise, we code them as 0. In terms of loan source, this describes the relationship between the banks and the firm further. Specifically, firms were asked whether their main bank was the only provider of the loan, one of the providers, or whether the loan was provided by a bank other than the firm’s primary bank. In the last instance, we would anticipate that the “external” bank would have had less information about the quality of the firm and the entrepreneur. In general, we anticipate that working with a new bank or securing a loan from multiple sources may impact the price of loan (Kim et al. 2012; Peterson and Rajan 1994; Vos et al. 2007). In addition, we controlled for the access of the entrepreneur to other sources of external finance. Entrepreneurs may use more than one source of external finance to fund their company, and the various forms available may be more or less sensitive to information asymmetries and require more or less information disclosure or firm monitoring. To this end, the pecking order hypothesis (Myers 1984) posits that firms exhibit a preference hierarchy in seeking sources of finance, starting from internal sources to debt and then equity financing. To the extent that external equity is rare and that other forms of debt instrument (e.g. leases and overdrafts) entail lower agency costs, term loans may be at the bottom of the hierarchy. In this case, firms may view term loans from banks as funding of last resort. Those who approach banks later, having exhausted all other avenues of funding, may be viewed as more risky than those who approach banks early, confident in their ability to repay principal and interest and to satisfy monitoring requirements.Footnote 5 Alternatively, using multiple sources may signal to banks good management and lessen the risk. Regardless, it is clear that the financing decisions of the entrepreneur prior to or at the time of the loan request may affect the perceived riskiness of the business. The issue is one of the sequencings (i.e. when the bank was approached in relation to other sources of finance). Unfortunately, our data do not allow us to directly address this issue. Rather, to reflect the idea that the entrepreneur has exhausted less costly sources of financing, and those which entail a lower agency burden, we build a proxy based upon the number of sources of external finance the firms had used during the 3 years prior to, or were using at the time of, the survey. Ideally, we would like detail on the financing of the firm before the loan request, but the data did not provide any information to shed light on the historical financing activities. The index is a simple count of identified use of loans from the owner, loans from family and friends, leasing and higher purchase agreements, credit cards, and overdraft funding.

Our second set of control variables is intended to capture firm heterogeneity. The first of these variables is a “usual suspect” in empirical studies of small firms—viz. size. Size has been shown to affect both access to and price of credit (Aterido et al. 2011; Beck et al. 2005; Binks and Ennew 1996; Freel 2007; Vos et al. 2007). Even within small firm samples, larger firms are less likely to suffer (or to suffer less) from information opacity and their performance may be more easily evaluated (Berger and Udell 1998). In this study, size is measured by the number of employees and coded into four size-bands: zero employees, 1–9, 10–49, and more than 50 employees. The zero size-band provides our reference category. We also control for broad sectoral variation at the SIC division level. Here, agriculture acts as our reference category. Finally, we also include the age of the business as a control variable. As the firm grow older, one expects that the credit history and reputation of the firm act as risk-mitigating factors. Due to the structure of the questionnaire and number of observations, we defined age of the business as 1 if it is older than 10 years and zero otherwise.

Beyond these structural characteristics, banks also rely on information they have on the quality of the owner of the business (as a borrower) (Berger and Frame 2007). To this end, we were able to incorporate in our models measures of entrepreneurial experience, and owner-manager’s age and gender. However, when these are included with business age in our models, collinearity becomes a concern. In the final analyses, we use age of the entrepreneur in preference to entrepreneurial experience. Importantly, our key findings are robust to this choice. Lastly, we control for gender of the principal owner. This is measured as a simple binary variable taking the value 1 if the principal owner was male, and 0 otherwise.Footnote 6

3.4 Descriptive statistics

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the variables used in our analyses. As the data in panel A illustrate, most of the firms are active in the service sector, have between 10 and 49 employees, and are older firms. For almost two-thirds of firms, their main bank is the only provider of the loan. From the data in panel B, 82 % of firms are principally owned and managed by men; the remaining 18 % of firms are run by women or jointly. Seventy-seven percentage of sample firms had a banking relationship extending more than 3 years, and 76 % of firms were required to collateralise the loan of interest.

Panel B also records the distribution of firms across our key independent variables, such that 17 % of firms were classed as “supergrowth” firms (i.e. firms experiencing growth more than 30 % in each of the 3 years preceding the survey and intending to growth in the three subsequent years). This figure is largely constrained by the 19 % of sample firms that were recorded as having experienced growth in the previous 3 years. Perhaps unsurprisingly, 71 % of firms reported an intention to pursue growth in the coming years. This large figure may speak to normative biases or over-optimism. However, only around 25 % of firms indicate an intention to “grow substantially”, which is closer to the number of past growers. In terms of growth strategies, 22 % of firms indicated their intention to seek growth through penetrating into new markets, 30 % expect growth through new product or services, 55 % expect to increase the sale of existing product in the same market, and 34 % plan to recruit more employees. As noted, these strategies were not mutually exclusive and firms could select more than one strategy for growth.

4 Methods

To examine the relationship between firm growth and the price of loans, and given the ordered nature of our dependent variable, we estimate a series of ordered probit models (Greene and Hensher 2009). However, only a proportion of the sample report loan rates, since only a proportion of our sample have outstanding loans. Focusing only on these firms may result in sample selection bias. This bias may result from two selection issues: firstly, we only deal with firms that applied for and were offered loans and, secondly, among those firms, we opt to consider only those that received variable rated loans. To control for potential issues of selection bias, we estimate a two-stage model (Heckman 1979). For completeness, we present the results of both the simple ordered probit and the two-stage ordered probit in Tables 3 and 4 (the details of the selection model used in the two-stage Heckman model is detailed in the following section). Ordered probits, along with other forms of regression, are sensitive to collinearity among the independent variables. For this purpose, Table 2 also displays variance inflation factors (VIFs) for all the explanatory variables—calculated in regressions excluding and including the inverse Mills ratio (IMR). In no cases is there evidence of multicollinearity.

5 Results

Table 3 presents the result of the simple ordered probit models. All the models are statistically significant at 99 %. In the first instance, our base model considers the control variables that are intended to proxy firm heterogeneity. Here, we note that firm size associates with loan pricing. That is, as the size of the firm increases, loan price decreases. This is consistent with our expectations. Beyond this, we observe that older firms, the use of funds to purchase assets, and the provision of collateral are significantly negatively related to the probability of paying higher interest rates. To restate, if a firm used the loan to purchase fixed assets and/or provided collateral for the loan, then the probability of paying a higher price for the loan falls. In contrast, there is tentative evidence that the probability of paying a higher loan rate rises with the age of the entrepreneur.

The second model includes all our control variables along with past growth. The significant variables from our base model continue to associate with loan prices, except for the age of the business. However, we also now note a negative relationship between loan syndication and the probability of paying higher interest rates. Importantly, and in line with hypothesis 1, firms that experienced rapid growth in the past have a higher probability of paying more interest.

Model 3 is concerned with growth intentions. In this, our control variables largely act in the same manner. However, we do not find any support for our second hypothesis. There is no evidence that firms declaring an intention to grow in the future pay higher rates of interest. Our initial intuition was that this was likely to relate to the high proportion of firms reporting a growth intention. Over 70 % of firms in the sub-sample declared an intention to grow over the 3 years following the survey. However, recoding the variable to indicate only those firms planning to grow “substantially” does not change this finding. It would seem that banks pay little regard to broad growth intentions in pricing loans. However, it may also reflect the countervailing effects of different intended strategies (see below).

As a supplementary analysis, we introduce an interaction term to model 4. It indicates that, when coupled with past growth, growth intentions do associate with higher loan prices. That is, firms enjoying growth in the past and planning to grow in the future are more likely to have paid higher rates of interest on their loans. The survey team termed such firms “supergrowth”, but one may also think of them as sustainable growers. Regardless, this result provides further evidence in support of the global hypothesis that growing firms are discriminated on price in loan markets. These firms differ from “future growth” firms to the extent that, despite having proven past success, they continue to pay more for loans than their non- and less growing peers.

The final model in Table 3 is concerned with the relationship between different growth strategies and loan prices. Here, the results are broadly in line with H3. Of our four growth modes, growth through new product introduction is positively associated with loan rates, whilst growth through sales of existing products is negatively associated with growth rates. In other words, firms pursuing a “more of the same” strategy appear to pay less for loans than those pursuing more aggressive, innovative strategies. In our analysis, penetrating into new market and hiring more employees are not significant explanatory variables in predicting the probability of higher or lower interest rates. These results support our speculations about the associations between modes of growth and loan pricing, whereby riskier strategies are associated with more expensive bank financing. Conversely, firms intending to sell more of “tested-and-tried” products are associated with lower cost of financing. The countervailing effects of aggressive and conservative intended strategies may also help explain the lack of a significant finding in support of H2.

As noted earlier in the paper, the foregoing analyses may be susceptible to selection biases arising from our focus only on those firms who held variable rate loans. To control for the potential sample selection bias, the Heckman (1979) two-stage model has been used. In the first stage, we estimate a probit model of the probability of accessing loans for all the observations in the sample. To calculate the probability of having loans in firms, we introduce the following selection equation:

In our selection equation, we try to consider not only the variables that ease access to loans (e.g. firm size, asset base, and legal status) (Beck and Demirguc-Kunt 2006; Berger and Udell 1998, 2006; Freel 2007), but also variables that may affect the demand for loans (e.g. export activity, innovation, and recent capital expenditure). In this way, we see loan utilisation as a function of both firms’ demand and banks’ willingness to supply. Exporting, innovation, and capital expenditure are reported by the owners or managers. From this equation, we calculate the inverse Mills ratio (IMR) which is subsequently used as an additional explanatory variable in the second-stage model. As Table 4 records, the coefficient of the IMR is statistically significant in four models out of five.Footnote 7 This suggests the presence of selection bias (Jones 2007, 36–37), although our data do not support the existence of selection bias in one of the models.Footnote 8

Turning to our two-stage ordered probit, with Heckman correction; Table 4 takes a similar approach to Table 3, but all models include the IMR calculated from the probit selection equation. Although the thrust of these results is broadly in line with regard to our independent variables, there is one intriguing difference with respect to our control variables. Firm size, measured by the number of employees, was a negative and significant explanatory factor in the probability of paying higher loan prices in the absence of our control for potential selection bias. However, when selection is controlled for, size is no longer significant. It would seem that, whilst size may associate with holding a loan, it has no robust influence on loan pricing. However, syndication, collateralisation, and loan use continue to be significantly negatively associated with the probability of paying higher interest rates.

In all but our ancillary “supergrowth” model, the existence of sample selection bias is indicated. However, where this is controlled for, we continue to find evidence to support hypotheses 1 and 3—though not hypothesis 2. In other words, firms which have recorded past growth or who intend to grow through innovation are likely to have paid higher rates of interest on their loans. Our sustainable, or “supergrowers”, are also likely to have paid a higher price for credit. These firms, whilst not denied credit, are discriminated on the basis of price. In the next section, we turn to the implications of these findings.

6 Discussion and concluding remarks

Based on UK survey of SME Finance (2007), we find that growth firms pay higher interest rates on bank loans. This result holds after controlling for the effects of size, owner’s experience, industry sector, loan purpose, collateral, and relationship banking. In simple terms, firms that have successfully grown their businesses in the recent past paid higher interest rates. Even where these firms anticipated sustaining their growth, they exhibited a higher probability of paying more. That is, despite evidence of success and ambition, interest rates are higher.

Moreover, although intention to grow does not, on its own, show any association with higher price, we note that intended growth strategy associates with loan price. Specifically, more risky strategies, involving the introduction of new products and services, associated with higher interest rate; whilst, more conservative strategies, associated with increased sales of the same products in existing markets, associate with lower loan prices.

Crucially, none of the foregoing need imply a criticism of banks. Growth and innovation are likely to entail additional risks to small businesses. Although banks are the primary sources of financing when entrepreneurs decide to seek external financing (Robb and Robinson 2014), banks are not risk funders. Rather, in assessing loan applications, banks are interested in the “serviceability” of the firms not the value of the business: the ability to generate enough cash flow to pay the debt (Cowling et al. 2012; Lee et al. 2014). In this sense, growing small firms may be perceived as less attractive to risk-averse banks. Other sources of external financing such as venture capital funds are presumed to be better suited to the financing of viable high-risk projects. However, for reasons of both supply and demand, venture capital is used by only a small proportion of firms. In our sample, only four out of 2500 firms sought venture capital financing in the 3 years prior to 2007 and only 11 % reported that they may consider equity financing in future. If the risk of a project is too high that banks cannot offer any interest rate to hedge the risk, the project may be declined or the loan downsized. More often, however, the interest rate rises (Parker 2002) and valuable capital is diverted to the loan provider in the form of a risk premium. This might open a door for interventions designed to ameliorate the apparent risk of growth firms.

Academic commentary has recently argued that interventions in the process of establishment or growth of SMEs are justified if targeted to growing and innovative firms (Shane 2009; Mason and Brown 2011; Nightingale and Coad 2014). If programmes do not recognise the differences among the firms, their implementation will favour lower-quality firms at the expenses of higher-quality ones (Nightingale and Coad 2014). Supporting lower-quality firms would decrease the investment rate of return and consequently would increase the price of capital for all type of firms (Nightingale and Coad 2014). Alas, it seems easier to call for support targeted to high growth firms than to provide practical guidance on how this may be achieved. In large part, this is because “[high growth firms] are found across all sectors of the economy, a heterogeneity that is also reflected in their age, size, origin, and ownership” (Mason and Brown 2011, p. 222).

We believe that focusing on the riskiness of growth firms may be a useful starting point for practical intervention. This rests on an appreciation of growth risk as both objective and perceived. To the extent that growth firms are objectively riskier, there is little policy that can do other than offering to bear risk. This is what loan guarantee schemes (LGS) currently do. Whilst belief in the existence of credit rationing is the fundamental rationale for loan guarantee schemes (Cowling 2010), in practice they encourage incrementality or additionality in lending (Riding et al. 2007). That is, they encourage lending to firms that would have received turndowns otherwise due to their higher risk of default (Zecchini and Ventura 2009). Crucially, guarantors typically apply a fee to cover defaults and protect the integrity of the scheme, thus raising loan price. Regardless, our concern is not with firms that would otherwise be turned down for a loan. Rather, ours is with those [growth] firms who pay a higher price for loans. To this end, whilst Riding and Haines (2001) observes that the objective of LGS is to assist small firms, not to subsidize risky ones, one might wonder if there was a role for a targeted schemes whose objective was to subsidise risk. Of course, the broader provision of grants to growing firms would be a more direct form of subsidy—providing some funds and signalling firm quality in the event of a loan application.

Regardless, in the absence of further evidence, we are agnostic on the desirability of interventions aimed at addressing the objective riskiness of growth firms—at least, beyond that which already exists. However, we are more convinced of the merits of potential interventions aimed at reducing perceived riskiness. Much of the banks assessment of small firm risk is likely to result from the greater information opacity attendant upon small firms generally and growing small firms specifically. Past evidence has suggested that, for SMEs, relationship banking may provide access to finance at lower costs (Binks and Ennew 1996). Relationships reduce information asymmetry. However, there may be other, more timely, ways of reducing information asymmetries. In this, an analogy may be drawn with the growing number of Investment Readiness Programmes across Europe (Mason and Kwok 2010). Mason and Kwok (2010) note that the primary reason that businesses are not “investment ready” is one of the information failures. In large part, this involves presentational shortcomings: “Even if the underlying proposition is sound a business may still fail to raise finance if the business plan is poorly constructed and presented” (Mason and Kwok 2010, p. 272). The parallels to “debt readiness” are clear. Given the relative use of debt and equity even among growing small firms, interventions designed to improve the “debt readiness” of growing firms may be well suited. In line with “investment readiness” (Mason and Harrison 2001), the main goal of such assistant to growth firms should be increasing the quality of loan application and also providing information on the different banking product and services, and their associate costs, potentially available for those firms.

In conclusion, based on the 2007 UK survey of SME Financing and information on the variable rate loans, we find that growing firms hold more expensive loans. Similarly, those whose future growth plans revolve around innovation are also more likely to hold higher priced loans. We interpret these findings to indicate a relationship between firm risk (both objective and perceived) and loan pricing. However, there are inevitably limitations to our research. In the first instance, higher loan rates may simply reflect the willingness of growth firms to accept poorer contract terms. Busy entrepreneurs must allocate precious time and resources to apply for a loan. In consequence, they are more willing to meet the higher loan price because of the higher opportunity/transaction costs they incur—relative to non-growth firms.Footnote 9 Secondly, for the firms that had grown in the three previous years, our data do not provide any information on whether the premium rate was contracted before, after or coincidental to growth. Still, the significant partial relationship between the modes of future growth and interest rate suggests that even if the loan is granted before initiating growth process, it captures the higher risk profile. Moreover, the modal number of years firms had held loans in the sample was between 1 and 3 years. Thirdly, from all the bank facilities available to SMEs, our study was only concerned with term loans and only variable rate term loans. Overdrafts or lines of credit, which are likely to be important sources of working capital, are only a minor component in our financial “bundling” explanatory variable. Future research might investigate the relationship among different risk profiles, the propensity to use broader bank facilities, and the price those facilities obtain. Although we loosely proxy the capital structure of the firm in terms of number of sources an entrepreneur uses, this sheds limited light on the perceived riskiness of the business prior to contracting loan terms and conditions. Further research, where data are available, may consider the riskiness of the business due to its proximate financing decisions.

Fourthly, we concentrated on variable rate loans and the premium above base rates. Our expectation was that base rates control for macro-fluctuations. Nonetheless, our results may be context specific. The UK banking system is relatively concentrated on supply side (Competition Commission Report 2002). As reported by Competition Commission (2002), SME owners mainly work with one bank for all their required services and rarely change their banks for better prices. Owners of course have the option to seek quotes from different banks, but the associate costs and the perceived importance of banking relationship to the owners make bargaining difficult (Competition Commission Report 2002). Moreover, the scope for “shopping around” is more limited than would be the case in a more fragmented banking market. In the UK SME loan market, lending relationship becomes important for banks and SMEs: banks try to lock in their customers, as SMEs are less likely to switch to new banks, and SMEs use relationship banking to access finance more easily or on better terms (Berger and Udell 2006). Concentration in banking markets has been shown to associate with the extent of relational lending (Ashton and Keasey 2005). Moreover, establishing a long-term relationship would aid banks to assess SMEs activities with lower degree of information opacity (Ashton and Keasey 2005). In such a market, growing and innovative firms may be more likely to accept higher fees in order to keep their relationship with their banks and ensure their access to finance at the time of cash flow difficulties. However, increasing competition among banks may increase customers’ bargaining power and lower the price of loans (Rice and Strahan 2010).

The final consideration is the pertinence of our findings given the current situation in the UK loan market following the financial crisis. Small firms’ access to bank facilities experienced a sharp decline from 2008. Whilst SMEs decreased their demand for finance, the supply side was marked by a “U-shaped pattern”, with an initial decline and subsequent recovery to the levels experienced before December 2009 (Cowling et al. 2012). Small businesses, in the early part of this period, experienced higher rejection rates comparing to previous years. But the situation eased considerably after 2009 (Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs 2014: An OECD Scoreboard 2014). These patterns held for all types of SMEs. Intriguingly, in the case of growing and innovative firms, firms intending to grow reduced their demands, but firms who had achieved growth before the crisis maintained the same level of debt demand (Cowling et al. 2012). Nonetheless, Lee et al. (2014) show that access to bank finance for innovative firms became more difficult after the financial crisis (based on 2007–2012 loan applications) and that these firms were more likely to be unable to secure debt financing from any bank. Yet, the average credit scoring of innovative and non-innovative firms did not differ significantly during this period, suggesting that assessments of objective risk remained at the same level (Lee et al. 2014). One possible explanation of higher rates of loan refusal for innovative firm might be banks’ increased perceived risk about their activities. In the recessionary period, the most significant factor affecting the loan appraisal decision was the size of businesses, with growth orientation apparently ignored in the process of decision-making (Cowling et al. 2012). Regardless, given the recovery of loan approval rates to before-crisis levels, we anticipate that banks are likely to rely upon the same criteria to appraise loan applications as prevailed in the pre-recession period. In short, bank assessment of risk and subsequent pricing are likely to follow similar logics today as when our data were collected.Footnote 10

Notes

In the UK, this is typically the Bank of England base rate plus some premium determined by individual banks.

To confirm our intuition, we performed a similar suite of analyses on fixed rate loans. As expected, these models were poor predictors of loan rate, with few significant variables. The results are available on request.

The survey question specified the 30 % threshold.

As a robustness check, we coded only those firms declaring an intention to grow substantially as 1, otherwise 0. The results were unchanged.

We are grateful to an anonymous reviewer for raising this possibility.

This would include cases where the principal ownership was female or shared.

The results of first-stage probit regression are available on demand.

Another model considering the use of variable rate loans as the dependent variable of the probit (selection) model was also estimated. The results were broadly in line with the reported approach.

We are grateful to anonymous reviewer for raising this possibility.

Informal conversations with British banking professionals suggest that this is a reasonable supposition. The things that “mattered” stayed the same. Rather, it is the threshold at which they matter that changed during the crisis.

References

Ashton, J., & Keasey, K. (2005). Competition and the provision of banking services to SMEs in the UK. Small Business Economics, 24(5), 477–485. doi:10.1007/s11187-005-6447-x.

Aterido, R., Hallward-Driemeier, M., & Pagés, C. (2011). Big constraints to small firms’ growth? Business environment and employment growth across firms. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 59(3), 609–647.

Barkham, R., Gudgin, G., & Hart, M. (2012). The Determinants of Small Firm Growth: An Inter-Regional Study in the United Kingdom 1986–1990. Routledge. http://books.google.ca/books?hl=en&lr=&id=7IU95d1d_4wC&oi=fnd&pg=PT7&dq=determinants+of+growth+firms&ots=4WDZfVxwgM&sig=nEC_5zB3Ld6aikpyuEf2HYjopNw.

Barringer, B. R., Jones, F. F., & Neubaum, D. O. (2005). A quantitative content analysis of the characteristics of rapid-growth firms and their founders. Journal of Business Venturing, 20(5), 663–687. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2004.03.004.

Baum, J. R., Locke, E. A., & Smith, K. G. (2001). A multidimensional model of venture growth. Academy of Management Journal, 44(2), 292–303. doi:10.2307/3069456.

Becchetti, L., & Trovato, G. (2002). The determinants of growth for small and medium sized firms. The role of the availability of external finance. Small Business Economics, 19(4), 291–306.

Beck, T., & Demirguc-Kunt, A. (2006). Small and medium-size enterprises: Access to finance as a growth constraint. Journal of Banking & Finance, 30(11), 2931–2943. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2006.05.009.

Beck, T., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Maksimovic, V. (2005). Financial and legal constraints to growth: Does firm size matter? The Journal of Finance, 60(1), 137–177. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.2005.00727.x.

Berger, A. N., & Frame, W. S. (2007). Small business credit scoring and credit availability*. Journal of Small Business Management, 45(1), 5–22.

Berger, A. N., Frame, W. S., & Miller, N. H. (2005). Credit scoring and the availability, price, and risk of small business credit. Journal of Money Credit and Banking, 37(2), 191–222.

Berger, A. N., & Udell, G. F. (1998). The economics of small business finance: The roles of private equity and debt markets in the financial growth cycle. Journal of Banking & Finance, 22, 613–673.

Berger, A. N., & Udell, G. F. (2003). Small business and debt finance. In Z. J. Acs & D. B. Audretsch (Eds.), Handbook of Entrepreneurship Research (pp. 299–328). Great Britain: Kluwer Academic Publisher.

Berger, A. N., & Udell, G. F. (2006). A more complete conceptual framework for SME finance. Journal of Banking & Finance, 30(11), 2945–2966. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2006.05.008.

Binks, M. R., & Ennew, C. T. (1996). Growing firms and credit constraint. Small Business Economics, 8, 17–25.

Birch, D. L. (1990). Sources of job growth—and some implications. In J. D. Kasarda (Ed.), Jobs, earnings, and employment growth policies in the United States (pp. 71–76). Netherlands: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-2201-3_4.

Brush, C. G., Ceru, D. J., & Blackburn, R. (2009). Pathways to entrepreneurial growth: The influence of management, marketing, and money. Business Horizons, 52(5), 481–491. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2009.05.003.

Coad, A., & Rao, R. (2008). Innovation and firm growth in high-tech sectors: A quantile regression approach. Research Policy, 37(4), 633–648. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2008.01.003.

Competition Commission Report. (2002). The supply of banking services by clearing banks to small and medium-sized enterprises: A report on the supply of banking services by clearing banks to small and medium-sized enterprises within the UK. I. UK: Competition Commission. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/http://www.competition-commission.org.uk/rep_pub/reports/2002/462banks.htm#summary.

Cosh, A., Hughes, A., Bullock, A., & Milner, I. (2008). Financing UK small and medium-sized enterprises: The 2007 survey. http://publications.eng.cam.ac.uk/361860/.

Cowling, M. (2010). The role of loan guarantee schemes in alleviating credit rationing in the UK. Journal of Financial Stability, 6(1), 36–44. doi:10.1016/j.jfs.2009.05.007.

Cowling, M., Liu, W., & Ledger, A. (2012). Small business financing in the UK before and during the current financial crisis. International Small Business Journal, 30(7), 778–800. doi:10.1177/0266242611435516.

Davidsson, P., & Henrekson, M. (2002). Determinants of the prevalance of start-ups and high-growth firms. Small Business Economics, 19(2), 81–104.

De Meza, D. (2002). Overlending? The Economic Journal, 112(477), F17–F31. doi:10.1111/1468-0297.00681.

Delmar, F., Davidsson, P., & Gartner, W. B. (2003). Arriving at the high-growth firm. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(2), 189–216.

Dobbs, M., & Hamilton, R. T. (2007). Small business growth: Recent evidence and new directions. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 13(5), 296–322. doi:10.1108/13552550710780885.

Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs 2014: An OECD Scoreboard. (2014). OECD: Center of Entrepreneurship, SMEs, and Local Development. http://www.oecd.org/cfe/smes/financing-smes-scoreboard-2014.htm.

Freel, M. S. (2007). Are small innovators credit rationed? Small Business Economics, 28(1), 23–35. doi:10.1007/s11187-005-6058-6.

Freel, M., Carter, S., Tagg, S., & Mason, C. (2010). The latent demand for bank debt: Characterizing ‘discouraged Borrowers’. Small Business Economics, 38(4), 399–418. doi:10.1007/s11187-010-9283-6.

Garnsey, E., Stam, E., & Heffernan, P. (2006). New firm growth: Exploring processes and paths. Industry & Innovation, 13(1), 1–20. doi:10.1080/13662710500513367.

Greene, W. H., & Hensher, D. A. (2009). Modeling ordered choice. C.T Bauer College of Busniess. http://www.bauer.uh.edu/rsusmel/phd/OrderedChoiceSurvey.pdf.

Heckman, J. J. (1979). Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica, 47(1), 153. doi:10.2307/1912352.

Henrekson, M., & Johansson, D. (2010). Gazelles as job creators: A survey and interpretation of the evidence. Small Business Economics, 35(2), 227–244. doi:10.1007/s11187-009-9172-z.

Hoffman, A. N. (2007). A rough guide to entrepreneurship policy.In A. R. Thurik, D. B. Audretsch, I. Grilo (Eds.), Handbook of entrepreneurship policy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Ioannidou, V., & Ongena, S. (2010). ‘Time for a Change’: Loan conditions and bank behavior when firms switch banks. The Journal of Finance, 65(5), 1847–1877.

Jones, A. M. (2007). Applied econometrics for health economists: A practical guide. Abingdon: Radcliffe.

Kim, M., Kristiansen, E. G., & Vale, B. (2012). Life-cycle patterns of interest-rate mark-ups in small-firm finance*. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 114(2), 629–657. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9442.2011.01688.x.

Lee, N. (2013). What holds back high-growth firms? Evidence from UK SMEs. Small Business Economics, 43(1), 1–13.

Lee, N., Sameen, H., & Cowling, M. (2014). Access to finance for innovative SMEs since the financial crisis. Copenhagen: In CBS.

Levenson, A., & Willard, K. (2000). Do firms get the financing they want? Measuring credit rationing experienced by small businesses in the US. Small Business Economics, 14(2), 83–94.

Mason, C., & Brown, R. (2011). Creating good public policy to support high-growth firms. Small Business Economics, 40(2), 211–225. doi:10.1007/s11187-011-9369-9.

Mason, C. M., & Harrison, R. T. (2001). ‘Investment Readiness’: A critique of government proposals to increase the demand for venture capital. Regional Studies, 35(7), 663–668. doi:10.1080/00343400120075939.

Mason, C., & Kwok, J. (2010). Investment readiness programmes and access to finance: A critical review of design issues. Local Economy, 25(4), 269–292.

Myers, S. C. (1984). The capital structure puzzle. The Journal of Finance, 39(3), 574–592. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.1984.tb03646.x.

Nightingale, P., & Coad, A. (2014). Muppets and gazelles: Political and methodological biases in entrepreneurship research. Industrial and Corporate Change, 23(1), 113–143. doi:10.1093/icc/dtt057.

Nitani, M., & Riding, A. (2013). Growth, R&D intensity and commercial lender relationships. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 26(2), 109–124. doi:10.1080/08276331.2013.771852.

OECD. (2013). Entrepreneurship at a Glance 2013. Paris: OECD Publishing. http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/industry-and-services/entrepreneurship-at-a-glance-2013_entrepreneur_aag-2013-en.

Parker, S. C. (2002). Do banks ration credit to new enterprises? And should government intervene? Scottish Journal of Political Economics, 49(2), 162–194.

Peterson, M., & Rajan, R. (1994). The benefits of lending relationships: evidence from small business data. The Journal of Finance, XLIX(1), 3–37.

Rahaman, M. M. (2011). Access to financing and firm growth. Journal of Banking & Finance, 35(3), 709–723. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2010.09.005.

Rice, T., & Strahan, P. E. (2010). Does credit competition affect small-firm finance? The Journal of Finance, 65(3), 861–889. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.2010.01555.x.

Riding, A. L., & Haines, G. (2001). Loan guarantees: Costs of default and benefits to small firms. Journal of Business Venturing, 16 (6), 595–612. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(00)00050-1.

Riding, A., Madill, J., & Haines, G. (2007). Incrementality of SME loan guarantees. Small Business Economics, 29(1–2), 47–61. doi:10.1007/s11187-005-4411-4.

Riding, A., Orser, B. J., Spence, M., & Belanger, B. (2012). Financing new venture exporters. Small Business Economics, 38(2), 147–163. doi:10.1007/s11187-009-9259-6.

Robb, A. M., & Robinson, D. T. (2014). The capital structure decisions of new firms. Review of Financial Studies, 27(1), 153–179.

Shane, S. (2009). Why encouraging more people to become entrepreneurs is bad public policy. Small Business Economics, 33(2), 141–149. doi:10.1007/s11187-009-9215-5.

Sharpe, S. A. (1990). Asymmetric information, bank lending, and implicit contracts: A stylized model of customer relationships. The Journal of Finance, 45(4), 1069–1087.

Smallbone, D., Leig, R., & North, D. (1995). The characteristics and strategies of high growth SMEs. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 1(3), 44–62.

Stam, E., Suddle, K., Hessels, J., & Van Stel, A. J. (2007). High growth entrepreneurs, public policies and economic growth. In Jena economic research papers. http://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/25593.

Stiglitz, J., & Weiss, A. (1981). Credit rationing in markets with imperfect information. The American Economic Review, 71(3), 393–410.

Storey, D. J. (1998). The ten percenters: Fourth report: Fast growing SMEs in Great Britain. London: Deloitte & Touche International.

Strahan, P. E. (1999). Borrower risk and the price and nonprice terms of bank loans. FRB of New York Staff, no. 30 (October). doi:10.2139/ssrn.192769.

Vickery, J. (2008). How and why do small firms manage interest rate risk? Journal of Financial Economics, 87(2), 446–470.

Vos, E., Yeh, A. J., Carter, S., & Tagg, S. (2007). The happy story of small business financing. Journal of Banking & Finance, 31(9), 2648–2672. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2006.09.011.

Wiklund, J., & Shepherd, D. (2005). Entrepreneurial orientation and small business performance: A configurational approach. Journal of Business Venturing, 20(1), 71–91. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2004.01.001.

Zecchini, S., & Ventura, M. (2009). The impact of public guarantees on credit to SMEs. Small Business Economics, 32(2), 191–206.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rostamkalaei, A., Freel, M. The cost of growth: small firms and the pricing of bank loans. Small Bus Econ 46, 255–272 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-015-9681-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-015-9681-x