Abstract

Previous literature finds that the quality of judicial enforcement has a positive impact on average firm size, but it has not disentangled its effect on the growth of incumbent firms from that on business demography. This distinction is crucial, as entrants are generally smaller than incumbents, but both high entry rates and high firm growth are associated with better economic performance. This paper fills this gap, finding that judicial efficacy fosters the growth of incumbents and promotes entry in Spain. The paper also shows for the first time that the specific type of judicial procedure that companies face in case of a conflict, rather than the overall functioning of courts, is the relevant matter. Specifically, judicial efficacy at the declaratory stage (when a debt is verified by a judge) has a positive impact on both firm growth and entry, while it has no impact at the execution stage (when the judge requires its payment).

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Spanish firms are small in international terms and they operate in markets with low entry and exit rates. Núñez (2004) found that the average size of firms in Spain was below that of firms in several other European countries and in the USA. López-García and Sánchez (2010) showed that Spanish companies were on average half as large as the companies in other European economies. Núñez (2004) showed that the turnover rate (sum of entry and exit rates) in Spain was 16 % lower than that in other countries analyzed except Germany. Analyzing more recent data, López-García and Puente (2007) reached the same conclusion in the context of OECD countries. García-Posada and Mora-Sanguinetti (2014) also find that both entry and exit rates in Spain are lower than the European average.

The analysis of those facts is relevant as numerous studies have shown that there are positive links among firm size, business demography, innovation and productivity growth (see, inter alia, Brandt 2004; Pilat 2004; Scarpetta et al. 2002; Foster et al. 1998; López-García and Montero 2012; Martin-Marcos and Jaumandreu 2004; Huergo and Jaumandreu 2004; Fariñas and Ruano 2004). Along with this, Spain has been characterized by low productivity growth and low innovation over the most recent years (Dolado et al. 2013; Bentolila et al. 2011; Mora-Sanguinetti and Fuentes 2012a, b).

The literature has suggested several determinants of firm size and growth, such as market size, economic development, access to credit, the stock of physical and human capital and the relevant industry. Business demography may also be affected by labor market regulations, entry regulations and personal bankruptcy laws. In addition to the above factors, an effective judicial system (or, more generally, the quality of the economy’s “enforcement institutions”) seems to have an effect on average firm size. Following Kumar et al. (2001), countries with efficient judicial systems seem to have larger firms. Laeven and Woodruff (2007) and Dougherty (2014) found that firms located in Mexican states with weak legal environments are smaller than those located in states with stronger ones. Giacomelli and Menon (2013) examined evidence for Italy and showed that the average size of manufacturing firms is lower in municipalities where the period of time required to obtain a judgment is longer. Fabbri (2010) found that law enforcement in Spain has a significant impact on business financing and on firm size based on her sample of manufacturing companies.

But all these studies focus on the impact of judicial enforcement on average firm size without differentiating between the two possible channels: the effect on the growth of incumbent firms (intensive margin) and the effect on entry and exit rates (extensive margin).Footnote 1 However, identifying the specific channel is crucial in order to draw the correct policy implications, as entrants are generally much smaller than incumbents, but both high entry rates and high firm growth are associated with higher productivity growth and innovation. To put it differently, higher average firm size is not always desirable, as it could reflect sclerotic markets characterized by low entry and exit rates rather than by high-growth firms. In this paper, we find that judicial efficacy fosters the growth of incumbents and that it also promotes entry, while it has no impact on firms’ exits. Hence, increasing judicial efficacy would be welfare-improving in Spain, regardless on its impact on average firm size.

The paper also shows, for the first time, that the specific type of judicial procedure that companies must face in case of a conflict is the relevant matter and not so much the overall functioning of the judicial system. Consequently, in this paper, we differentiate between the specific impact of the various civil procedures available both at the declaratory stage and at the execution stage. The study of different procedures allows us to determine what stage is more important for business decisions: whether the time at which the existence of a debt is declared and acknowledged by a judge (declaratory stage) or the time at which the judge enforces its payment (executory stage). Specifically, we find that judicial efficacy at the declaratory stage has a positive impact on firm size, firm growth and entry rates, while judicial efficacy at the execution stage has no impact whatsoever. Various reasons may be influencing this fact: penalties for delayed payment, risk aversion (even if the probability of punishment is small, individuals may suffer from a disutility higher than the expected punishment), internalization of social values (the “right” thing to do is to abide by the law, once there is a ruling against the company) and reputation (there is an immediate damage to the reputation of the company when it loses a trial, whether or not it decides to comply with the obligations imposed in the judgment). In any case, our findings warn that the use of “aggregate” measures of civil efficacy, as done in the previous literature, may be incomplete.

Finally, this is first time that the relationship among firm size, firm growth, business demography and judicial efficacy in Spain is analyzed following the entry into force of the new civil procedural rules of 2000, which completely changed the civil justice system in Spain.Footnote 2 We also use data at the provincial level, whereas previous studies on Spain (Fabbri 2010) used data at the aggregate regional level (Comunidades Autónomas) and linked them with data on manufacturing firms, while our data cover all relevant industries.

The importance of studying the effectiveness of the judiciary and its impact on firm size and business demography in Spain is justified by the fact that the Spanish judicial system demonstrates low efficiency compared with that of other countries. Spain holds the position 26 out of a total of 35 legal systems in its ability to resolve disputes before the first instance courts according to the database constructed recently by the OECD (Palumbo et al. 2013). Even less favorable results can be found on the Doing Business (DB) Project of the World Bank in its “enforcing contracts” indicator, published since 2004. Spain ranked 64th among 185 countries covered in the reports of 2012 and 2013. Specifically, Spain was in a worse position than other economies with similar levels of development such as the other big European economies (with the exception of Italy). The conclusions of this paper are thus relevant for this general problem. Thanks to the distinction of the different stages of judicial procedures, this research provides a guide on where to intervene peremptorily in order to optimize the resources invested in the Spanish judicial system: in order to promote entry and firm growth, preference should be given to speeding up declaratory judgments (at the expense of other potential areas).Footnote 3

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents a discussion of the theoretical channels linking judicial efficacy with firm size. Section 3 explains the construction of various measures of judicial efficacy and firm size, as well as the control variables and some sample characteristics. Section 4 presents our estimation strategy, and Section 5 discusses the empirical results. Finally, Section 6 provides some conclusions.

2 Theoretical background: how the functioning of the judicial system affects firm size, firm growth and business demography

The literature suggests several channels according to which we should observe an impact of the judicial system on firm size, firm growth and business demography.

First, judicial efficacy affects firm growth through the investment decisions faced by firms and entrepreneurs. As poor contract enforcement increases projects’ risks and raises their expected costs, this can lead to less investment and reduce growth opportunities. This is corroborated by the empirical evidence of Laeven and Woodruff (2007), who find a positive relationship between judicial efficacy and average firm size. This relationship is stronger for proprietorships than for corporations, as the owners of the latter are more protected against contract enforcement risks thanks to limited liability. Laeven and Woodruff (2007) also argue that an improvement in the functioning of the judicial system will increase average firm size by making the least productive firms exit the market and the most productive ones grow. An improved judicial system implies higher production efficiency, which will increase the demand for production factors (capital and labor) and will in turn raise wages and rental rates. This will induce low-ability entrepreneurs to leave self-employment for salaried work, while only the most talented entrepreneurs will continue to run their own businesses. Therefore, there will be fewer companies and those companies will employ more workers. As a result, average firm size will increase.

Second, since poor contract enforcement increases transaction costs, firms’ optimal response may be vertical integration, implying a negative relationship between judicial efficacy and firm size.

Third, in the absence of well-functioning courts, parties need to rely on relational contracting, which may lead to high switching costs and barriers to entry: trust in existing suppliers may make firms reluctant to purchase from new suppliers (Johnson et al. 2002). Hence, better contract enforcement may increase entry rates. The development of the judicial system also allows trade of more complex goods, as a third party can verify the terms and conditions of the contract, encouraging firms to undertake specific investments and probably grow more.

Fourth, Chemin (2009) finds several reasons why an improvement in court efficacy dramatically increased entry rates in his study of Pakistan’s judicial reform. The reform improved entrepreneurs’ confidence that their workforce would not be prevented from working due to law and order situations. As unemployed individuals were more confident in their ability to obtain credit, they applied for loans and they also applied or sought land, buildings or machinery to establish their businesses.

Finally, both firm growth and business demography can be indirectly influenced by the quality of the judicial system through the credit channel. Inefficient systems are associated with difficulties in contract enforcement and hence with weaker creditor protection. As a result, weaker investor protection would decrease the availability of credit, hampering firm growth. This conjecture is corroborated by Jappelli et al. (2005), who find that credit is more widely available in the Italian provinces where there is higher judicial efficiency. Fabbri (2010) finds that the cost of financing is higher in regions where court proceedings take longer and this could have an effect on firm size as well. Judicial system improvements seem also to be related to higher access to finance and lower costs of credit in India (Visaria 2009; Chemin 2012). Regarding business demography, greater judicial ineffectiveness, by reducing access to external finance, also reduces entry of new enterprises, which are usually smaller than incumbent firms (Giacomelli and Menon 2013). As a result, the overall impact of reduced funding on average firm size may be ambiguous when measured empirically (Kumar et al. 2001).

In summary, the above channelsFootnote 4 imply an ambiguous impact of judicial efficacy on firm size and growth (“intensive margin”) and a positive one on entry and exit rates (“extensive margin”). Hence, the sign of the former and the magnitude of the latter are empirical matters.

3 Data

3.1 Measuring the efficacy of specific judicial procedures in Spain

This paper constructs a set of efficacy measures by judicial procedure using direct information provided by the courts, specifically by the Spanish General Council of the Judiciary (Consejo General del Poder Judicial, hereinafter CGPJ). The CGPJ has published a database reporting the number of cases filed, resolved and still pending in the Spanish judicial system by region, court, year, subject and procedure. Therefore, this information allows us to differentiate by the specific type of civil procedure used at the declaratory stage [ordinary judgment, verbal judgment, payment (monitory) procedure and bills of exchange and cheques procedure] or at the execution stage. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first paper that differentiates among different civil procedures in contrast with previous literature, which used data on “aggregate” civil proceedings.

The data also provide information on the nature of the conflict (civil, criminal, administrative and labor) and on the specific court in which the procedure takes place. Constructing efficacy measures from the raw CGPJ data is a complex issue, so the following paragraphs attempt to explain it.

As an outline (see Fig. 1),Footnote 5 first we should identify the jurisdiction that deals with the conflicts we consider most relevant to the functioning of a company. Different types of conflicts are dealt with by different jurisdictions inside the Spanish judicial system (civil, social, administrative and criminal), which are served by different groups of judges and courts. Spanish companies may be confronted with very different types of conflicts in their daily functioning. A company may have to deal with conflicts with its employees (for instance, a dismissed worker may sue the company). In this case, conflicts are regulated by labor legislation and will be resolved in accordance with such laws by the employment tribunals (juzgados de lo social). A company may also have to deal with conflicts with public administrations. For example, a company may be discriminated against in a public procedure or the administration may fail to respond correctly to a request from a company. Those conflicts will be subject to administrative law and may have to be resolved through appeals to administrative courts (juzgados de lo contencioso-administrativo). Finally, conflicts may arise with other private firms or other private parties such as suppliers and customers. Examples of such conflicts include a non-payment of a service, disputes concerning the interpretation of a contract for the sale of goods and claims related to the intellectual property of a work or service. Those conflicts will be dealt with by civil courts (juzgados de lo civil). We decided to focus our analysis on civil conflicts because we consider that they are the most relevant to the activity of companies.Footnote 6

Once we have identified the relevant jurisdiction (the civil jurisdiction), we need to find the specific courts where the conflict is going to be resolved. These are the first instance courts (juzgados de primera instancia) and the first instance and instruction courts (juzgados de primera instancia e instrucción). Conflicts must enter the judicial system through these courts.Footnote 7 Finally, the specific procedure that must be used is determined by the Civil Procedural LawFootnote 8 (CPL), which regulates all civil conflicts in Spain.Footnote 9 First, the claimant company will have to obtain a declaratory judgment acknowledging that a debt or other right exists. If that is the case, the judge will declare the obligation of the debtor to pay or to compensate the right infringed. There are different types of declaratory judgments (see Fig. 1). Ordinary judgments (juicios ordinarios) are used if the conflict involves a sum of at least 6,000 Euros or relates to certain matters (such as appeals against decisions of the governing bodies of the company). Verbal judgments (juicios verbales) are given where the disputed amount is less than 6,000 Euros. Simpler exchange (juicios cambiarios) and monitory (juicios monitorios) procedures may be converted into verbal or ordinary judgments if the debtor defends the claim. Thus, we consider ordinary judgments to be the most interesting declaratory judgment to analyze. After the declaratory stage, an execution judgment may take place. This only occurs when the debtor does not pay the debt or fails to comply with the obligations imposed by the judge at the declaratory stage. That is, the claimant will ask the judge to (forcibly) “execute” the decision. The judge may, for instance, seize the amounts of a debt from the accounts of the debtor.

Using the raw data available from the CGPJ database, we have constructed a measure of efficacy for each court (which we have aggregated at the provincial level) and for each procedure (see Padilla et al. 2007; Mora-Sanguinetti 2010, 2012a, b): the congestion rate (see equation below).

The congestion rate is defined as the ratio between the sum of pending cases (measured at the beginning of the period) plus new cases in a specific year and the cases resolved in the same year. A lower congestion rate is related to greater efficacy of the procedures inside the judicial system. An average congestion rate of 2.41 in Madrid over the period 2001–2009 indicates that around two and a half cases (summing up the pending cases and the new cases arriving to the courts of Madrid in a specific year) were awaiting resolution while the courts were able to resolve just one.

The system of procedures explained above was adopted in 2000, replacing the previous system (CPL of 1881), and no business conflict has been initiated using the 1881 CLP since January 1, 2001 (Mora-Sanguinetti 2010). Therefore, although the CGPJ performance data of the civil courts are available since 1995, we only use data from 2001 onward. For the purposes of the analysis herein, we have chosen to aggregate the data at the provincial level,Footnote 10 although more disaggregated data on the judicial system are available. While a province may comprise one or more judicial districts, all of them share the same first instance (and first instance and instruction) courts, implying that the province is the relevant territorial unit for our analyses.

The CPL establishes the rules of territorial competence, that is, the court that will resolve the conflict. As a general rule, claims are entered at the province of the registered office of the defendant.Footnote 11 If the dispute concerns the annual accounts of the company, the court must be that of the province where the company has its registered office and the same rule generally applies to bankruptcy proceedings. If the claim relates to real assets (i.e., buildings), the conflict will be resolved at the province where the real assets are located. Moreover, in the case of small firms (the vast majority of the Spanish businesses), most of their trade and relations with other companies are likely to occur within one province.Footnote 12

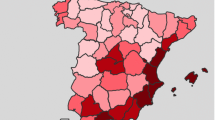

Although the CPL is a national Law, the efficacy of courts may differ among Spanish provinces due to supply and demand factors. On the supply side, the resources invested in the justice administration differ, at least at the regional level.Footnote 13 On the demand side, litigation propensity may differ among provinces. This geographical variation in efficacy is illustrated in Fig. 2, which shows the average congestion rate for ordinary judgments (map on top) and executions (map on the bottom) at the provincial level for the period 2001–2009. There was, on average, a difference of 1.16 congestion points between the most effective (Álava) and the least effective (Alicante) province throughout the period. The difference is 3.87 points in the case of executions, between Álava (the most effective on average) and Castellón. Figure 3 shows the variation through time of the congestion rate (again, for ordinary judgments and for executions) for a group of provinces with low congestion (Álava, Guipuzcoa, Navarra and Zaragoza), with high congestion (Baleares, Málaga, Almería) and for Madrid, Spain’s capital and its largest city. As expected, congestion rates increased during the first years of the current economic crisis (2008 and 2009) in most provinces, as conflicts between contract parties are likely to arise when there are financial difficulties.

Congestion rate: geographical variation. a Ordinary judgements. b Executions. Source: Self-elaboration and Consejo General del Poder Judicial (2012)

Congestion rate: time variation. a Ordinary judgments. b Executions. Source: Self-elaboration and Consejo General del Poder Judicial (2012)

3.2 Measuring firm size and firm growth

We use two different gauges of firm size, total revenue and total employment to check the sensitivity of our results.Footnote 14 Those variables are obtained at the firm level from the SABI database for the period 2001–2009. SABI is a database that contains the annual accounts of Spanish companies,Footnote 15 both private and publicly held, and general information, such as the location of the registered office, the year of incorporation and the main industry of activity. The data on nominal revenue from SABI are deflated using sector-specificFootnote 16 value-added deflators from the OECD’s STAN database.

We do not use an additional measure of firm size and total assets, because assets in SABI are valued at their acquisition (historical) cost and SABI does not provide their purchase date, so they cannot be deflated. Using them at their book value would underestimate the size of old firms and overestimate the size of young firms. Moreover, total assets are comprised of very different items such as land, buildings, machinery, inventories or cash, so we would need a specific deflator for each component. But the fact that real revenue and total assets are highly correlated (0.73) suggests that we are not losing very relevant information.

Regarding the data selection criteria, we eliminate firms that entered or exited the marketFootnote 17 during the period of study, i.e., 2001–2009. There are two reasons to do so. First, we isolate the “intensive margin,” i.e., the impact of judicial efficacy on the size of incumbent firms. Second, we substantially reduce a major cause of non-random attrition in our panel: since the firms that enter or exit the market are, on average, smaller than the incumbents in Spain (López-García and Puente 2007), the probability that some observation is missing may be related to firm size. State-owned companies are also eliminated because, in Spain, they may resolve their conflicts in different courtsFootnote 18 and under different legal procedures than private firmsFootnote 19 and because the factors that determine their size may not be market-driven. We exclude foreign companies, as they may resolve their conflicts in other legal systems by engaging in “forum shopping.” We also eliminate consolidated accounts, i.e., the financial statements that integrate the accounts of the parent company and those of its subsidiaries into a single aggregated accounting figure. The reason is that several subsidiaries may have different registered offices and in turn use the courts of different provinces. Nonprofit organizations and membership organizations are also excluded. Finally, we also eliminate non-yearly financial accounts—since flow variables such as turnover can only be compared for firms with the same time length in their accounts—and observations with data inconsistencies.Footnote 20 Although the available information does not allow us to eliminate multi-plant firms and companies with multiple plants located in different provinces are likely to use the courts of those provinces, this problem is not severe in the case of Spain, since the majority of Spanish firms are mono-plant.Footnote 21 Nevertheless, in a robustness analysis, we have removed the financial services industry, where multi-plant firms are much more common. The results—see online Appendix D—are very similar.

The final sample has around 460,000 firms.Footnote 22 Online Appendix A shows their size distribution by province and by year as the arithmetic averages of employment and real revenue, respectively, suggesting that our sample is representative of the population of Spanish firms.

3.3 Measuring business demography

We compute entry and exit rates using census data from the Spanish National Statistics Institute (INE). The entry (exit) rate is the number of firms that enter (exit) a province in a given year as a percentage of all the active firms in that province at the end of the year (which include the new and continuing firms). Notice that those definitions of entry and exit rates implicitly characterize the relevant market at the territorial level, which is a simplifying assumption: while market definition is often a difficult task, it usually hinges on two dimensions, the spatial one and the industrial one. Unfortunately, we could not compute entry/exit rates at the province-industry level due to data constraints.Footnote 23

Both variables display substantial variation across provinces and years. Figure 4 shows the average (2001–2009) entry and exit rates by province in Spain. Average entry rates for the period 2001–2009 range between the 15 % of CaceresFootnote 24 and the 8.2 % of Soria. Average exit rates for the same period range between the 11.8 % of Gerona and the 7.6 % of Soria. There is little correlation between entry and exit rates (0.01). Entry rates have decreased and exit rates have increased since the onset of the last recession (2007–2009), as shown in Fig. 5.

3.4 Control variables

The literature has suggested several determinants of firm size and growth and/or business demography. Market size, per capita income and economic growth may have a positive impact on firm size (Laeven and Woodruff 2007; Lucas 1978; Tybout 2000; Urata and Kawai 2002). Access to credit is also a determinant of firm growth (Beck et al. 2008), as is the amount of available physical and human capital (Lucas 1978; Rosen 1982; Kremer 1993; Tybout 2000) and the industry in question (Kumar et al. 2001). In addition to those factors, business demography may be affected by labor market regulations (e.g., Botero et al. 2004), entry regulations (e.g., Djankov et al. 2002) and personal bankruptcy laws (e.g., Armour and Cumming 2008).

Most of our controls are province-level variables. We measure market size by the province’s GDP.Footnote 25 Economic development is captured by GDP per capita and the unemployment rate.

To measure access to credit, we include the banking credit to GDP ratio (credit/GDP), the number of bank branches per 1,000 persons (branches), the non-performing loans ratio of credit institutions (Npl ratio) and the ratio of defaulted accounts receivable to GDP (Dar/GDP). Banking credit to GDP ratio and branches per capita are standard measures of financial development (Rajan and Zingales 1995; Giacomelli and Menon 2013). We expect higher ratios to be associated with less financial constraints. The ratio of defaulted accounts receivable to GDP is an alternative proxy of credit constraints that focuses on trade credit instead of banking credit (Padilla et al. 2007). A higher ratio means, ceteris paribus, lower incentives for borrowers to repay—probably because of poor creditor protection or contract enforcement—which causes more credit rationing. The same reasoning applies to the non-performing loans ratio.

It also seems appropriate to control for industrial composition since the type of industry is a determinant of firm size due to factors such as economies of scale and economies of scope. To capture industrial composition, we compute the ratio of the gross value added of the main six industries (primary sector, energy, manufacturing, construction, market services, non-market servicesFootnote 26) over the total gross value added of each province.

We control for other market characteristics. We measure the degree of competition with the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI).Footnote 27 We take into account the average level of vertical integration in the province, since firms may respond to poor contract enforcement by vertically integrating their production process and vertically integrated firms are expected to be larger. Vertical integration is measured by the ratio of value added to sales, where value added has been corrected for extraordinary positions.Footnote 28 This ratio is expected to be higher for vertically integrated firms because of their lower expenses in outside purchases of intermediate inputs. We first compute this ratio at the firm level and then we average it across firms. We also control for differences in capital–labor ratios. We first compute the firm-level capital intensity as the ratio of capital stock (tangible fixed assets plus inventories) to the number of employees and then we average it across firms. Finally, we take into account the proportion of corporations, since limited liability incentivizes investment and growth.

We capture the availability of human capital with the share of PhD graduates on population. We include the share of foreigners on population as well, since cultural factors may influence entrepreneurship and foreigners may have a different propensity to litigate. To keep into account the negative impact of criminality on economic activity and businesses, we compute crime rates as the number of convictions over population.Footnote 29 Finally, following the findings of Carmignani and Giacomelli (2010), we use the number of lawyers per 10,000 people (Lawyers) as a proxy of litigation intensity, since cheaper access to legal services may help firms grow but it may also congest the courts.

Finally, for the analysis of firm size and growth, we also use two firm-level variables: the company’s age and the ratio of tangible fixed assets to total assets (tangibility). According to Berger and Udell (1995) and Petersen and Rajan (1994), age captures the public reputation of the firm. We test for the presence of nonlinear effects by including the square of age. As tangible assets have more collateral value than intangible assets, firms with high values of Tangibility may have a lower cost of credit (Rajan and Zingales 1995; Fabbri 2010).

Other factors such as the bankruptcy code, the labor law, the level of protection of patent rights and accounting standards have no relevance to this study as they are set at the national level in Spain, so they exhibit no geographical variation, while any nationwide change in these regulations will be captured by the time dummies.

Table 1 provides a description of the variables used in our analyses, distinguishing between firm-level variables and province-level variables. Table 2 contains some descriptive statistics on those variables and other sample characteristics, while Table 3 shows the sample’s industry distribution. We can see that the median firm has five employees and it generates revenue of 400,000 Euros, i.e., it is a very small firm. However, the large standard deviations of those variables and the right skewness of their distributions require that those variables are analyzed in logarithm form in our regression analyses. The median firm is also 11 years old. Most firms in the sample are limited liability unlisted companies. The sample covers all relevant industries, with 28 % belonging to wholesale and retail trade, 19 % to real estate, renting and business activities, 18 % to manufacturing and 15 % to construction.

4 Estimation strategy

4.1 Identification strategies

As it was discussed in the introduction, the main caveat of previous studies is that they focus on the impact of judicial enforcement on average firm size without differentiating between the two possible channels: the effect on the size and growth of incumbent firms (intensive margin) and the effect on entry and exit rates (extensive margin). We will also differentiate between the efficacy of civil procedures at the declaratory stage (i.e., when a debt is declared and recognized by a judge) from those at the execution stage (i.e., when the judge requires its payment), as the assessment of the overall functioning of the judicial system—as done by the previous literature—may be misleading if only some procedures influence firm’s behavior.

4.2 Analysis of the intensive margin: firm size and firm growth

The analysis of the intensive margin is carried out by regressing firm-level measures of firm size and growth on province-level congestion ratios, a wide set of controls, firm fixed effects and time dummies. Formally, it can be expressed as follows:

where \(Y_{ijt}\) is either firm size or firm’s growth (measured in terms of employment or real revenue), α i is firm fixed effects, Congestion rate jt is the measure of judicial (in)efficacy (for the specific judicial procedure considered in each case), \({\text{Control}}_{it}^{k}\) is a set of K control variables, d t are time dummies and the indices i, j, t refer to the firm, province and time period, respectively.Footnote 30

Our key regressor, the congestion rate, could be interpreted as the “price” of the market for judicial services, i.e., the observed court congestion in a province in a certain year is the result of the supply of judicial services being equal to its demand. Hence, congestion rate is a function of supply and demand factors. The key-identifying assumption is that, in the case of Spain, the supply of judicial services is exogenous to firms’ size and to firms’ decisions to grow and enter/exit markets. If the supply of legal services was determined by the companies’ and individuals’ demand for justice in each province, we should observe no or little variation in courts’ congestion across the 50 provinces, but Fig. 2a, b shows considerable variation across them. More remarkably, the most industrialized Spanish provinces, which are those with larger firms and arguably more litigation, exhibit very different levels of congestion. While the Basque country provinces and Navarra have low congestion rates, Barcelona has intermediate levels and Madrid relatively high ones. A potential explanation of those facts is that resources are allocated according to the population size of each province, a criterion that fails to take into account the differences in the intensity of corporate litigation and in the complexity of trials (Fabbri 2010; Mora-Sanguinetti 2012a, b). Moreover, the courts considered in this study (“juzgados de primera instancia” and “juzgados de primera instancia e instrucción”) are not specialized in corporate matters, as they also resolve a wide range of conflicts that are totally unrelated to corporate decisions (e.g., evictions, inheritance conflicts). Thus, the distribution of those courts is not likely to be influenced by the distribution of conflicts relevant to firms’ decisions. Judges in Spain are also obliged to process and resolve cases in chronological order of entry, and therefore cannot give preference to corporate conflicts over those between individuals.

By contrast, the demand of judicial services may be endogenous to firms’ size as larger firms may have a higher propensity to litigate because of the fixed cost component of judicial services,Footnote 31 hence increasing courts’ congestion. To overcome that identification challenge, we undertake three different strategies. First, size—either measured in terms of employment or revenue—is set at the firm level in our regressions, while the congestion rate and the controls are set at the province level. Since the decision of a single firm to litigate is likely to have a negligible impact on the congestion of the courts of a whole province, that design should alleviate endogeneity concerns.Footnote 32 However, if there is a common shock that makes many (large) firms in the same province to litigate at the same time, then that identification strategy would not solve the problem. Hence, the second strategy is to use, for robustness, an alternative dependent variable, firm’s growth, whose correlation with firm size is quite modest (0.22 and 0.16 in terms of revenue and employment, respectively). The use of that variable also has the advantage of allowing for a direct test of the effect of judicial efficacy on firm’s growth. The third strategy, following Giacomelli and Menon (2013),Footnote 33 consists of controlling for differences in litigation intensity across provinces by adding the variable Lawyers in some specifications. Finally, in the event that those strategies did not totally remove the reverse-causality bias, we know the sign of such a bias: we would find a positive correlation between firm size/growth and court congestion. By contrast, since our estimates show a negative relation between firm size/growth and court congestion (see Sect. 5), either that bias does not exist or it is not large enough to offset the causal effect of judicial enforcement on firm size/growth. In other words, our estimates provide the lower bound of the true causal effect.

Another identification challenge is that firms’ locations are endogenous and may depend on factors such as the efficacy of judicial procedures. In such a case, if firms prefer regions with more effective courts and larger firms benefit more from such courts because of their higher demand for judicial services (or their lower costs of changing their location), then part of the relationship between firm size and judicial efficacy could be due to an “attraction effect” rather than a “growth-enhancing effect.” However, our identification strategy rules out this potential source of bias by eliminating firms that entered or exited the market during the period of study.

4.3 Analysis of the extensive margin: entry and exit rates

In order to study the potential impact of the different judicial procedures on the decisions of firms to enter or exit a market, we regress entry and exit rates on (the log of) congestion rate of each procedure, a set of province-level controls, time dummies and province fixed effects. The controls are the same as in the previous analyses, with the exception of incorporation ratio, which is excluded because it would be an endogenous regressor by construction. Entry and exit rates are expressed in logs to correct for right skewness. Formally, the analysis can be expressed as follows:

where W jt is either the entry rate or the exit rate, α j is province fixed effects, Congestion rate jt is the measure of judicial inefficacy (for the specific type of judicial procedure considered in each case), \({\text{Control}}_{it}^{k}\) is a set of K control variables, d t are time dummies and the indices i, j, t refer to the firm, province and time period, respectively.Footnote 34

The identification strategy relies on the time dummies and the province fixed effects to ensure unbiased estimates. First, the entry and exit rates, the procedural congestion rate, measures of macroeconomic performance (GDP, unemployment) and proxies of credit conditions (e.g., credit to GDP, non-performing loans ratio) are expected to be correlated along the business cycle. By including time dummies, we control for this common factor. Second, entry rates and economic development are jointly determined by institutional factors and, more specifically, by regulations on entry (Djankov et al. 2002; Klapper et al. 2004). In Spain, an important part of the regulations governing entry (e.g., company’s registration, licenses) lies within the competence of the regions (Comunidades Autónomas) (Mora-Sanguinetti and Fuentes 2012a, b). A region may comprise one or more provinces. Since entry regulations and, in general, institutions, change slowly over time, the province fixed effects may capture them quite accurately in a short time period like the one used in our sample (2001–2009). Finally, since the main regulations governing exit, the labor law and the bankruptcy code, are set at the national level, we do not expect institutional factors to determine the geographical variation of entry rates, while any nationwide change in these laws would be captured by the time dummies.

Moreover, we are not concerned about reverse-causality problems because the supply of judicial services is exogenous (see discussion in previous section), and we do not expect the demand for the specific judicial procedures analyzed in this paper to be influenced by entry and exit rates, as conflicts related with companies’ entries or exits are generally solved in courts different from the general civil courts from which our data are drawn (juzgados de primera instancia, juzgados de primera instancia e instrucción). In the case of the (rare) conflicts regarding entry, those will be solved in the administrative courts, as it is the public administrations’ role to check that a firm meets all the requirements to begin its business activities. In the case of conflicts regarding exit, those concerning layoffs are resolved by the employment tribunals (juzgados de lo social) while bankruptcy procedures are tried in specialized mercantile courts (juzgados de lo mercantil) since 2004.Footnote 35 In any case, if exit rates had some impact on court congestion, we again know the sign of reverse-causality bias: we should expect a positive correlation between the two variables. By contrast, our estimates show a nonsignificant (negative) relationship between the two (see Sect. 5).

5 Results

We have carried out empirical analyses for each type of procedure (ordinary, verbal, monitory, exchange and executions). For brevity of exposition, we only display in the following sections the results for the representative declaratory judgment (ordinary judgment) and the executory judgment. The results corresponding to verbal judgments (see online Appendix B) and monitory and exchange—available upon are request—are similar to those for ordinary judgments.

We expect the different types of declaratory judgments (ordinary, verbal, monitory and exchange) to have a very similar impact on firm size. Executory judgments, however, as explained in Sect. 3.1, have a different nature and take place later than declaratory judgments. The correlations of our key variable congestion rate among those procedures corroborate this argument. As we can observe in Table 4, executions are lowly correlated with the rest of procedures, while all types of declaratory judgments are highly correlated among each other, with correlations ranging between 0.7 and 0.8 in most cases.

5.1 Analysis of the intensive margin

5.1.1 Ordinary judgments

We commence the analysis with ordinary judgments because, as discussed in Sect. 3.1, they are considered the most relevant civil procedures for companies. We run several regressions where the dependent variable is either firm size or firm growth. We measure firm size by total employment or real revenue (both of them in logs) and firm growth by the annual growth rate of those variables. Our key regressor is the (log) congestion rate of ordinary judgments (congestion ordinary). Some of the controls are also in logs to correct for right skewness. We show four different specifications for each dependent variable. Specification (1) only includes congestion ordinary, firm fixed effects and time dummies. Specification (2) adds to (1) some firm-level controls. Specification (3) adds to (2) a large set of province-level controls. Specification (4) also includes the variable Lawyers.Footnote 36

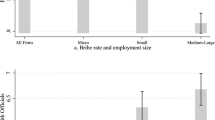

The results are displayed in Tables 5 and 6. Congestion ordinary always has a highly significant and negative coefficient, suggesting that judicial (in)efficacy has a negative impact on firm size and hampers firm growth.Footnote 37 The estimated elasticities and semi-elasticities are larger—in absolute terms—when size is measured in terms of revenue, suggesting that the inefficacy of the judicial system may deter more sales than hiring staff. The controls’ coefficients, when significant, usually have the expected sign.Footnote 38

We can evaluate the economic significance of the effect by means of a simple hypothetical experiment. Attributing to the province with the worst judicial efficacy the best law enforcement in our sample,Footnote 39 the relative increaseFootnote 40 in firm size would range between a 0.6 and a 2.8 %, while annual firm growth would rise between 1.1 and 2.8 % points.Footnote 41 Hence, the effect on size is quite modest, while the effect on growth is quite remarkable, especially considering that the average growth rate for the period 2002–2009 was −3.1 and 0.1 % in terms of revenue and employment, respectively.Footnote 42

The main result of the analysis of verbal judgments (displayed in online Appendix B) is the same as in the case of ordinary judgments: judicial inefficacy has a negative impact on firm size and growth, which is robust to all specifications.Footnote 43

5.1.2 Executory judgements

The results for the analysis of the executory judgments are displayed in Tables 7 and 8. In the case of firm size, the coefficient on congestion executions is always negative and statistically significant. However, it is very small in comparison with the analogous coefficient in the regressions for ordinary judgments. In the case of firm growth, the coefficient is never significant. These results indicate that judicial efficacy in executory judgments is not a robust determinant of firm size and firm growth.

A possible interpretation of these findings is that firms make their business decisions solely based on their expectations about the quality of legal enforcement in the first—and usually the only—stage of the process (the declaratory judgment) (see Fig. 1), which mainly corresponds to ordinary (or verbal, exchange, monitory) judgments. In other words, the enterprise does not take into account the efficacy of resolution of executory judgments, because the ruling of the judge in that first step is generally sufficient to make the contracting parties abide by their obligations. There may be several explanations for this: penalties for delayed payment, risk aversion (even if the probability of punishment is small, individuals may suffer from a disutility higher than the expected punishment), internalization of social values (the “right” thing to do is to abide by the law, once there is a ruling against the company) and reputation (there is an immediate damage to the reputation of the company when it loses a trial, whether or not it decides to comply with the obligations imposed in the judgment). Regarding the first argument (penalties for delayed payment), the Spanish procedural law establishes that, immediately after a judgment that compels the debtor to pay off a sum of money, the debt will accrue interest.Footnote 44 Therefore, this rule discourages the debtor to delay the payment and to cause the need of an executory judgment.

Regardless of the underlying factors, these results highlight the importance of taking into account the type of procedure when studying the link between firm size and growth and judicial efficacy. The difference between the procedures is important not only for businesses but also for the public administration, as it has to optimize its investments in the judicial system.

5.2 Analysis of the extensive margin

5.2.1 Ordinary judgments

The impact of judicial (in)efficacy on entry and exit rates, in the case of the ordinary judgments, is displayed in Table 9. The coefficient on congestion ordinary is negative and statistically significant in all the regressions where the dependent variable is the (log) entry rate, while it is never statistically different from zero when the dependent variable is the (log) exit rate.Footnote 45 The controls’ coefficients, when significant, usually have the expected sign, although most of them are insignificant, probably because their impact is picked up by the province fixed effects.

Those results suggest that judicial efficacy in ordinary judgments promotes entry and has no effect on exit. We can estimate the size of the effect using the same experiment as in the cases of firm size and growth. Attributing to the province with the worst judicial efficacy the best law enforcement in our sample, the relative increase in its entry rate would range between an 8.8 and a 9.5 %. Hence, the effect is not only statistically significant but also economically relevant.Footnote 46

Therefore, it seems that judicial efficacy in ordinary judgments influences average firm size through two different channels. On the one hand, it fosters the growth of incumbents, which increases average firm size. On the other hand, it also promotes entry and, since entrants are generally smaller, it decreases average firm size. The overall effect, as found in previous literature, seems to be positive. More important, while those channels have opposite effects on average firm size, both have a positive impact on the economy, since both larger firms and higher entry rates are associated with more innovation and higher productivity growth.

5.2.2 Executory judgments

The impact of judicial (in)efficacy on entry and exit rates in the case of the executory judgments is displayed in Table 10. The coefficient on congestion executions is never statistically different from zero.Footnote 47 Hence, judicial efficacy in executions has no effect on either entry or exit.

6 Conclusions

Previous literature has found that the quality of the legal system and, specifically, the aggregate effectiveness of courts have a positive effect on average firm size within a country. This paper goes a step further in two different (but complementary) directions.

First, it disentangles the impact of the different judicial procedures on average firm size between two possible channels: the effect on the growth of incumbent firms (intensive margin) and the effect on entry and exit rates (extensive margin). The identification of the specific channel is crucial in order to draw the correct policy implications, as entrants are generally much smaller than incumbents, but both high entry rates and high firm growth are associated with higher productivity growth and innovation. To put it differently, higher average firm size is not always desirable, as it could reflect sclerotic markets characterized by low entry and exit rates rather than by high-growth firms. In this paper, we find that judicial efficacy fosters the size and growth of incumbents and that it also promotes entry, while it has no impact on firms’ exits. Hence, increasing judicial efficacy would be welfare-improving, regardless on its impact on average firm size. This is particularly important in the case of Spain because Spanish firms are small in international terms, entry rates are relatively low and the Spanish economy is characterized by low TFP growth.

Second, this paper finds that the impact of the judicial system critically depends on the type of procedure used. Specifically, we find that judicial efficacy at the declaratory stage (i.e., when a debt is declared and recognized by a judge) has a positive impact on firm size, firm growth and entry rates, while judicial efficacy at the execution stage (i.e., when the judge requires its payment) has no significant impact whatsoever. Various reasons may be influencing this fact: penalties for delayed payment (the interest rate paid as a punishment is usually quite high), risk aversion (even if the probability of punishment is small, individuals may suffer from a disutility higher than the expected punishment), internalization of social values (the “right” thing to do is to abide by the law, once there is a ruling against the company) and reputation (there is an immediate damage to the reputation of the company when it loses a trial, whether or not it decides to comply with the obligations imposed in the judgment). While the Spanish judicial system suffers from higher general inefficacy than that of neighboring countries (Palumbo et al. 2013), this paper proposes a guide on where to concentrate efforts to optimize the resources invested in the Spanish judicial system: preference should be given to speeding up declaratory judgments. In any case, at the research level, our findings warn that the use of “aggregate” measures of civil efficacy, as done in the previous literature, may provide an incomplete view of the problem.

Finally, another contribution of the paper is to use more consistent measures of judicial efficacy in Spain than previous literature. We constructed measures of judicial efficacy with real performance data extracted from the courts and not survey data or statistical estimations. Moreover, this is first time that the relationship between firm size and judicial efficacy is analyzed in the case of Spain following the introduction of the new Civil Procedural Law in 2000.

Notes

The data used by Fabbri (2010) represent judicial performance from the old civil judicial system of Spain, which was abrogated in 2000.

As the Spanish government is drafting a bill (new Ley Orgánica del Poder Judicial, LOPJ) in order to reorganize some general aspects of the judicial system, this paper results may contribute to the current debate on the topic.

We do not explain an additional channel, the enforcement of employment protection legislations, as our database allows us to differentiate between different types of conflicts, and thus, we have focused the empirical analysis solely on civil cases. See Giacomelli and Menon (2013) for a discussion on the topic.

The basic organization of the Spanish judicial system is regulated by the above mentioned LOPJ. Following the National reform programme (2014), the government will present a draft bill to reform that Law.

A company may have also violated the public interest and therefore be criminally liable. However, such cases are quite rare under Spanish law.

In this study, we do not work with the second instance (i.e., appeals against the courts of first instance). The reason is that only 7.45 % of first instance cases are appealed to the second instance. Moreover, the problems of inefficacy of the Spanish judicial system (compared to other countries) seem to be concentrated in the first instance and not in the second, according to the results of the OECD (Palumbo et al. 2013).This does not rule out a possible future extension providing some analysis of the second instance.

Law 1/2000, of January 7th (Civil Procedural Law).

Two clarifications must be added. First, there are changes in this reasoning if the company has a conflict with a private subject which is foreign, but even in this case, the CPL may be used (depending on the case). Second, it must be noted that some extrajudicial solutions may be found by the parties, such as sending the case to arbitration. However, even in that case, only a judge can enforce an arbitral decision, always using the CPL and the judicial system.

Excluding Ceuta and Melilla (no information is available for those provinces).

Articles 50 and 51 of the CPL.

The competence at a more disaggregated level (i.e., the allocation of civil affairs within the same province) should not be a concern for the analysis. The allocation of cases among the courts of first instance of a particular province is made by the dean’s office on the basis of predetermined rules, which include, among others, random mechanisms (with several corrections). That is, firms cannot choose to litigate before a particular judge they may prefer.

The Spanish regions (Comunidades Autónomas) have some powers related to the administration of justice in Spain. Even though the judicial power is not properly transferred to the regions, management of judicial resources is influenced by the policies developed by the regions. For instance, they decide how much money is invested in new courts each year in their territories, even though the new courts are integrated into a system that is centrally governed.

The Pearson’s linear correlation coefficient between the two variables is 0.77.

The source of these data is generally the office of the Registrar of Companies.

Industries are defined at the two-digit level following the ISIC Rev.3 in STAN and the NACE Rev. 1.1. in SABI. There is a perfect matching between the two classifications.

We identify as an entrant a firm whose incorporation was in 2001 or later. To identify the firms that exited the market, we use SABI’s classification of companies into two main categories: “active” firms (i.e., currently operating in the market) and “inactive”.

Administrative courts (tribunales de lo contencioso-administrativo) instead of civil courts.

Specifically, they are often subject to Administrative Law, rather than Civil Law.

For instance, negative values in stock variables or observations that violate basic accounting norms.

According to the Spanish National Statistics Institute (INE), the average number of firms in the period 2001–2009 was 3,051,634 while the average number of plants in that period was 3,389,330, which implies that each firm had, on average, 1.1 plants.

Despite removing the firms that entered or exited the market, we have an unbalanced panel due to the uneven coverage across years. For instance, the last year of the period, 2009, has the lowest number of firms because the usual time lag in the submission of financial statements by firms is 2 years (Ribeiro et al. 2010) and the data from SABI were extracted at the end of 2010.

We could only construct entry rates (but no exit rates) at the province-industry level for limited liability firms with more than 50 employees. We then ran entry rates on congestion rates, our set of province-level controls, time dummies and province-industry fixed effects, i.e., a dummy for every province-industry combination. The results—see online Appendix E—are qualitatively the same as the ones displayed in this paper.

This figure seems to be partially driven by the high entry rate of firms in Cáceres in 2001. We have contacted the data provider, the Spanish National Statistics Institute, to check whether it was a mistake in the original source. As a robustness check, we have done all the econometric analyses substituting that figure by the province-mean in the period 2002–2009. The results have not qualitatively changed.

Unfortunately, the province-level GDP is only available in nominal terms, while it would be preferred to use it in real terms. But the fact that the GDP is strongly correlated (0.98) with an alternative real measure of market size, population, suggests that this problem is minor in our case.

By non-market services, we mean public administration and defense, compulsory social security, education, health and social services.

We have computed the HHI with all the available firms in our sample (890,000), i.e., we have included firms that entered or exited the market during the period of study, in order to increase the representativeness of the variable. We have computed two versions of the HHI, one at the province-industry level—where industry is defined at two digits using the NACE Rev. 1.1 classification—for the analysis of firm size and growth and one at the province level for the analysis of business demography.

Extraordinary positions are revenues or expenses that do not arise from the regular activities of a firm, such as insurance claims.

Notice that, as it was explained in Sect. 3.3, criminal cases are tried in separate courts than the civil cases that are analyzed in this paper, so we do not expect congestion rates to be influenced by the province’s degree of criminality.

The above regressions are estimated via the within-group estimator with clustered standard errors robust to heteroskedasticity and serial correlation. The fixed effects have been found jointly significant via cross-section poolability tests, while serial correlation has been found using the test of Wooldridge (2002). Results of both tests are available upon request.

For instance, most large corporations have their legal departments, while small businesses may choose to keep a lawyer or a staff of lawyers on retainer or hire them when their services are required.

In general, decisions at the firm level are not likely to affect judicial efficacy, macroeconomic performance or the provision of credit.

Although Giacomelli and Menon (2013) use a different variable, a litigation index, their aim is the same: to account for potential reverse-causality issues between size and judicial efficacy.

The above regressions are estimated via the within-group estimator with clustered standard errors robust to heteroskedasticity and serial correlation. The fixed effects have been found jointly significant via cross-section poolability tests, while cross-section correlation has been rejected using Pesaran’s CD test (2004). While the Wooldridge’s test (2002) has not been able to reject the null hypothesis of no serial correlation, note that the power of this test may be low when N is small, as it is in this case (N = 50). Drukker (2003) finds high power for samples between N = 500 and N = 1,000 and between T = 5 and T = 10.

The current bankruptcy law (Ley Concursal), which entered into force in September 2004, stipulated the creation of new courts (mercantile courts) that would be specialized in bankruptcy procedures. The procedures prior to that law were solved in the general civil courts.

Correlations among the regressors (see online Appendix C) suggest that there are no multicollinearity problems except for the case of Lawyers, which is highly correlated with GDP (0.81). In a number of experiments, we have tried other specifications, such as dropping some proxies for credit constraints and replacing GDP by GDP per capita. The size and significance of the coefficient on congestion rate was very similar. Results available upon request.

All the regressions in this section have a very low R 2, between 1 and 4 %. This is because most regressors, with the exception of age and tangibility, are province-level variables that attempt to explain the variation of a firm-level-dependent variable. We are not worried about this result because our main goal is to assess the effect of judicial efficacy via consistent estimates. Moreover, the use of the within-group estimator, rather than the least squares dummy variable estimator, to control for firm-level fixed effects, yields identical estimations of the coefficients but a much lower R 2. We have chosen the former because it is much less computationally expensive.

Two apparently striking results are, however, the negative coefficient on Foreigners and the positive one on crime rate, which contradict the findings of Giacomelli and Menon (2013). The reason is that the effect of those variables is very sensitive to the specific controls that are included in the regressions. In robustness checks—see online Appendix G—we have run the same regressions but substituting log (GDP per capita) for log (GDP). Then, the coefficient on Foreigners becomes positive and that on crime rate is insignificant or negative in most specifications.

The province with the best law enforcement (i.e., lowest value of congestion ratio) is Alava, with an average value of 1.65 for the period 2001–2009, while the province with the worst law enforcement (i.e., highest value of congestion ratio) is Alicante, with an average value of 2.80 for the same period. Therefore, the simulated change amounts to (1.65 − 2.80) × 100/2.80 = −41.2 %.

By relative change, we mean 100 × [X(1) − X(0)]/X(0), where X(0) and X(1) are the initial and final values, respectively.

Here, we mean a change in the level of the growth rate, a variable expressed in percentage, i.e., X(1) − X(0), where X(0) and X(1) are the initial and final values, respectively.

As we control for credit availability in our regressions, we expect those figures to be the lower bound of the total impact of judicial efficacy on firm size and growth, since previous literature has found a positive impact of judicial efficacy on credit availability (see Sect. 2).

The analyses of monitory and exchange—available upon request—also yield the same conclusion.

The interest rate applicable as punishment payment depends on the type of debt but it is, in any case, quite high. For example, the general punitive/judicial interest rate imposed as a result of court proceedings condemning payment of cash amounts is the legal interest rate (4 % in 2014) plus two percentage points, i.e., 6 %. Article 576 of the Civil Procedural Law.

The results are robust to specifying the dependent variables without the logarithmic transformation. Results available upon request.

As we control for credit availability in our regressions, we expect those figures to be the lower bound of the total impact of judicial efficacy on entry rates, since previous literature has found a positive impact of judicial efficacy on credit availability (see Sect. 2).

The results are robust to specifying the dependent variables without the logarithmic transformation. Results available upon request.

References

Armour, J., & Cumming, D. (2008). Bankruptcy law and entrepreneurship. American Law and Economics Review, 10(2), 303–350. doi:10.1093/aler/ahn008.

Beck, T., Demirguc-Kunt, A., Laeven, L., & Levine, R. (2008). Finance, firm size, and growth. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 40(7), 1379–1405. doi:10.1111/j.1538-4616.2008.00164.x.

Bentolila, S., Dolado, J., & Jimeno, J. (2011). Reforming an insider-outsider labor market: The Spanish experience. IZA discussion paper series, no. 6168. doi:10.1186/2193-9012-1-4.

Berger, A., & Udell, G. (1995). Relationship lending and lines of credit in small firm finance. Journal of Business, 68, 351–381.

Botero, J. C., Djankov, S., La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (2004). The regulation of labor. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(4), 1339–1382. doi:10.1162/003355304247621.

Brandt, N. (2004). Business dynamics in Europe. OECD Science, Technology and Industry. Working papers, 2004/1, OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/250652270238.

Carmignani, A., & Giacomelli, S. (2010). Too many lawyers? Litigation in Italian civil courts. Temi di discussione (working papers), no. 745, Banca d’Italia.

Chemin, M. (2009). The impact of the judiciary on entrepreneurship: Evaluation of Pakistan’s access to justice programme. Journal of Public Economics, 93(1–2), 114–125.

Chemin, M. (2012). Does court speed shape economic activity? Evidence from a court reform in India. Journal of Law Economics and Organization, 28(3), 460–485. doi:10.1093/jleo/ewq014.

Consejo General del Poder Judicial. (2012). La Justicia Dato a Dato Año 2011. Madrid: Consejo General del Poder Judicial.

Djankov, S., La Porta, R., López de Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (2002). The regulation of entry. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117, 1–35. doi:10.1162/003355302753399436.

Dolado, J., Ortigueira, S., & Stucchi, R. (2013). Does dual employment protection affect TFP? Mimeo: Evidence from Spanish manufacturing firms.

Dougherty, S. M. (2014). Legal reform, contract enforcement and firm size in Mexico. Review of International Economics, 22(4), 825–844. doi:10.1111/roie.12136.

Drukker, D. M. (2003). Testing for serial correlation in linear panel-data models. The Stata Journal, 2(3), 1–10.

Fabbri, D. (2010). Law enforcement and firm financing: Theory and evidence. Journal of the European Economic Association, 8(4), 776–816. doi:10.1111/j.1542-4774.2010.tb00540.x.

Fariñas, J. C., & Ruano, S. (2004). The dynamics of productivity: A decomposition approach using distribution functions. Small Business Economics, 22, 237–251. doi:10.1023/B:SBEJ.0000022231.00027.53.

Foster, L., Haltiwanger, J., & Krizan, C. J. (1998). Aggregate productivity growth: Lessons from microeconomic evidence. NBER WP 6803.

García-Posada, M., & Mora-Sanguinetti, J. S. (2014). Entrepreneurship and enforcement institutions: Disaggregated evidence for Spain. Banco de España working paper 1405. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2413422.

Giacomelli, S., & Menon, C. (2013). Firm size and judicial efficiency in Italy: Evidence from the neighbour’s tribunal. Banca d’Italia working paper 898.

Huergo, E., & Jaumandreu, J. (2004). How does probability of process innovation change with firm age? Small Business Economics, 22, 193–207. doi:10.1023/B:SBEJ.0000022220.07366.b5.

Jappelli, T., Pagano, M., & Bianco, M. (2005). Courts and banks: Effects of judicial enforcement on credit markets. Journal of Money Credit and Banking, 37, 224–244.

Johnson, S., McMillan, J., & Woodruff, C. (2002). Courts and relational contracts. Journal of Law Economics and Organization, 18(1), 221–277. doi:10.1093/jleo/18.1.221.

Klapper, L., Laeven, L., & Rajan, R. (2004). Business environment and firm entry: Evidence from international data. World Bank Policy Research working paper 3232.

Kremer, M. (1993). The O-ring theory of economic development. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108(3), 551–575. doi:10.2307/2118400.

Kumar, K., Rajan, R., & Zingales, L. (2001). What determines firm size? Chicago booth working paper. doi:10.2139/ssrn.170349.

Laeven, L., & Woodruff, C. (2007). The quality of the legal system, firm ownership, and firm size. Review of Economics and Statistics, 89(4), 601–614. doi:10.1162/rest.89.4.601.

Lichand, G., & Soares, R. (2014). Access to justice and entrepreneurship: Evidence from Brazil’s special civil tribunals. Journal of Law and Economics, 57(2), 459–499. doi:10.1086/675087.

López-García, P., & Montero, J. M. (2012). Spillovers and absorptive capacity in the decision to innovate of Spanish firms: The role of human capital. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 21(7), 589–612. doi:10.1080/10438599.2011.606170.

López-García, P., & Puente, S. (2007). A comparison of the determinants of survival of spanish firms across economic sectors. In J. M. Arauzo-Carod & M. C. Manjon-Antolin (Eds.), Entrepreneurship, industrial location and economic growth (pp. 161–183). Cheltenham: Edwar Elgar.

López-García, P., & Sánchez, P., (2010). El tejido empresarial español en perspectiva. Nota interna. Departamento de Coyuntura y Previsión Económica. Banco de España.

Lucas, R. E. (1978). On the size distribution of business firms. The Bell Journal of Economics, 9, 508–523. doi:10.2307/3003596.

Martin-Marcos, A., & Jaumandreu, J. (2004). Entry, exit and productivity growth in Spanish manufacturing during the eighties. Spanish Economic Review, 6(3), 211–226. doi:10.1007/s10108-004-0079-1.

Mora-Sanguinetti, J. S. (2010). A characterization of the judicial system in Spain: Analysis with formalism indices. Economic Analysis of Law Review, 1(2), 210–240.

Mora-Sanguinetti, J. S. (2012). Is judicial inefficacy increasing the weight of the house property market in Spain? Evidence at the local level. SERIEs, Journal of the Spanish Economic Association, 3(3), 339–365. doi:10.1007/s13209-011-0063-6.

Mora-Sanguinetti, J. S., & Fuentes, A. (2012). An analysis of productivity performance in Spain before and during the crisis: Exploring the role of institutions. OECD economics department working papers, no. 973. OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/5k9777lqshs5-en.

Núñez, S. (2004). Salida, entrada y tamaño de las empresas españolas. Boletín Económico. March. Banco de España.

Padilla, J., V. Llorens, S. Pereiras and N. Watson (2007). Eficiencia judicial y eficiencia económica: el mercado crediticio español. In La Administración Pública que España necesita. Libro Marrón. Círculo de Empresarios, Madrid.

Palumbo, G., Giupponi, G., Nunziata, L., & Mora-Sanguinetti, J. S. (2013). The economics of civil justice: New cross-country data and empirics. OECD Economics department working papers no. 1060. doi:10.1787/5k41w04ds6kf-en.

Pesaran, M. H. (2004). General diagnostic tests for cross section dependence in panels. University of Cambridge, Faculty of Economics, Cambridge working papers in economics no. 0435.

Petersen, M., & Rajan, R. (1994). The benefits of lending relationships: Evidence from small business data. The Journal of Finance, 49(1), 3–37.

Pilat, D. (2004). The ICT productivity paradox: Insights from micro data. OECD economic studies no. 38.

Rajan, R. G., & Zingales, L. (1995). What do we know about capital structure? Some evidence from international data. The Journal of Finance, 50(5), 1421–1460. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.1995.tb05184.x.

Ribeiro, S. P., Menghinello, S., & De Backer, K. (2010). The OECD ORBIS database: Responding to the need for firm-level micro-data in the OECD. OECD working paper no. 30-2010/1. doi:10.1787/5kmhds8mzj8w-en.

Rosen, S. (1982). Authority, control, and the distribution of earnings. The Bell Journal of Economics, 13(2), 311–323. doi:10.2307/3003456.

Scarpetta, S., Hemmings, P., Tressel, T., & Woo, J. (2002). The role of policy and institutions for productivity and firm dynamics: Evidence from micro and industry data. Economic department working papers, no. 329, OCDE.

Tybout, J. R. (2000). Manufacturing firms in developing countries: How well do they do, and why? Journal of Economic Literature, 38(1), 11–44. doi:10.1257/jel.38.1.11.

Urata, S., & Kawai, H. (2002). Technological progress by small and medium enterprises in Japan. Small Business Economics, 18(1), 53–67. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-0963-9_4.

Visaria, S. (2009). Legal reform and loan repayment: The microeconomic impact of debt recovery tribunals in India. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 1(3), 59–81. doi:10.1257/app.1.3.59.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2002). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Patricia Festa, Ildefonso Villán Criado, Fernando Gómez, María Gutiérrez, Juan Francisco Jimeno, Enrique Moral, Carlos Thomas and especially the editor and two anonymous referees for their useful comments and suggestions. We especially appreciate the work of Claire McHugh, who reviewed the manuscript in depth. We also wish to thank seminar participants, referees and discussants at two seminars of the Banco de España-Eurosystem, the III Annual Conference of the Spanish Association of Law and Economics (AEDE), the 2012 Annual Conference of the European Association of Law and Economics (EALE) and the 8th Annual Conference of the Italian Society of Law and Economics (SIDE-ISLE). We are also indebted to Marcos Marchetti, Paula Sánchez Pastor and Ángel Luis Gómez Jiménez for their assistance in the preparation of some of the variables and figures. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Banco de España.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

García-Posada, M., Mora-Sanguinetti, J.S. Does (average) size matter? Court enforcement, business demography and firm growth. Small Bus Econ 44, 639–669 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-014-9615-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-014-9615-z