Abstract

The ability of a country and its businesses to grow is tightly related to the possibility of exporting and penetrating into foreign markets. The aim of this article is to study whether bank support can help small businesses (SBs) exporting at the extensive as well as the intensive margin. We address this issue by using a large database on small Italian firms. We provide an empirical analysis of the role of bank support in affecting the firms’ export decisions. Our results show that among the exporting SBs those using bank services to support their exports have a higher probability of being better placed in both the intensive and the extensive margin. Moreover, these positive impacts on export are statistically significant only when the main bank of the firm is an internationalized bank. These results have relevant policy implications as well as consequences for the business models of internationalized banks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Penetrating into foreign markets is an important mechanism through which firms grow. In the latest years, against a stagnant domestic economy, the most dynamic European firms have sought compensation by internationalizing their sales. However, the literature underlines that internationalizing entails non-trivial investment, which implies substantial sunk costs. To become an exporter, a company must devote resources to identify its specific export market and undertake the adjustment needed to make its products adequate to that market, tailoring them to local tastes and conforming to the target country’s regulations. These sunk costs include, for example, acquiring information on foreign markets, setting up distribution networks and customizing products to fit local tastes (see, e.g., Baldwin and Krugman 1989; Dixit 1989). Furthermore, because most entry costs must be paid up front, potential exporters must have enough liquidity at hand. Hence, the internationalization is much more common for medium and larger sized enterprises than for smaller sized businesses (SBs). For these reasons, both theoretical and empirical literature have increasingly recognized the role of financial markets in firms’ international orientation and stressed that exports are particularly vulnerable to credit imperfections (see, e.g., Manova 2012; Chaney 2005; Minetti and Zhu 2011). Though this limitation applies to every country, it makes a straitjacket for the economies that have an industrial structure that consists primarily of SBs. In other words, supporting SBs’ internationalization would greatly help the growth of these countries.

The aim of this article is to study whether bank support can help SBs’ internationalization. Building on previous literature pertaining to larger sized enterprises, we take the empirical analysis to a tailor-made database compiled via an extensive survey of over 6,000 Italian SBs belonging to various sectors (manufacturing, services, trade and agriculture) run by UniCredit Banking Group. Our database includes very detailed individual information on firms’ internationalization, which is based directly on firms’ responses to survey questions. Indeed, since these firms were extracted from the loan portfolio of UniCredit, the database includes details on the relationship between the firm and the banking system and on balance sheet variables. The available information allows us to investigate two main issues. First, we study whether a tight credit relationship with the main bank impacts both the probability that a SB exports (the extensive margin) and the extent of firm-level exports of the firm’s sales (the intensive margin). Second, we test whether receiving bank support increases the probability that SBs export to more than one foreign market and export a larger share of their sales. Moreover, using specific questions included in the survey, we examine which features of the firm-bank relationship help SBs’ internationalization.

The results are in line with our expectations. We find that a closer relationship with the main bank increases the probability that firms enter foreign markets, but not the level of foreign sales. In particular, we argue that the role of the main bank in supporting SBs export is not limited to financial support, but includes also a “cultural” support.Footnote 1 The analysis then turns to disentangle the mechanisms through which bank support affects the extensive margin of trade. After accounting for the possible endogeneity of the bank support and controlling for a variety of factors that may also affect exports, we find that bank support seems to be relevant in explaining the actual number of countries in which firms export and the extent of its foreign sales. Moreover, the results show that the most effective bank services to promote SB export activities are traditional banking services (such as loans or credit insurance) and advisor services (such as counter-parties signaling or training services for commercial and administrative staff). Finally, the literature suggests that bank internationalization might have a particular role in fostering export propensity (see, e.g., Portes and Rey 2005). Besides providing a simple financial support, internationalized banks could act as information providers on the target market. In fact, internationalized banks, thanks to their knowledge of foreign markets, can offer precious advisory services on counterparty risk assessment of local importers or on the legal and economic features of the local market. In addition they can provide also in loco support, as for instance leasing services, through foreign branches. Our results support this hypothesis. In particular, our findings reveal that the benefit of bank support is stronger when the main bank of the SB is an internationalized bank.

There is a growing literature on the role of liquidity constraints on firm export. Theoretical works emphasize that exporting is particularly vulnerable to credit imperfections. For example, Manova (2012) and Chaney (2005), incorporating firm heterogeneity, analyze the impact of financial frictions on different trade margins. Their results imply that financial frictions have sizeable real effects on international flows and are important for understanding trade patterns.Footnote 2 However, firm-level empirical analyses reach less conclusive results on causality going from availability of finance to exports. On one hand, few studies reveal a positive nexus. Bellone et al. (2010) find that exporters have ex-ante a financial advantage vis-à-vis non-exporters on micro-data for France; the finding of Manova (2012) is that credit constraints can explain both the zeros in bilateral trade flows and the variation in the number of products exported as well as countries reached. On the other hand, for the UK, Greenaway et al. (2007) find no evidence that new exporters have better financial status than non-exporters. With a specific focus on Italian medium and large firms, Minetti and Zhu (2011) show that credit rationing significantly depresses the probability of exporting both at the extensive and intensive margin. They also find that the duration of the credit relationship with the main bank does not alter the probability of exporting. De Bonis et al. (2010) confirm these findings and display that the length of the firm-main bank relationship affects the firms’ decision to go abroad in the more sophisticated forms of internationalization—FDI and offshoring—but not whether they export.

This article makes two novel contributions. First, we focus on SBs (with turnover up to 5 million euros). Studying whether bank support can help smaller sized firms to export is relevant because the bulk of industry is frequently—and certainly in Italy—made of small firms and banks represent their main source of external finance. Moreover, the drivers motivating small firms to export may in part differ from what found for larger companies (see, e.g., Pope 2002). Second, thanks to the unusually detailed information, we are able to study the role of the different bank services (e.g., traditional banking services, advisory services, in loco support, etc.) on firm’s propensity to export.

The remainder of the article is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we describe the institutional background. Section 3 is devoted to the data description. Section 4 shows the main empirical evidence. In Sect. 5, we disentangle the mechanisms through which banks affect export decisions. Section 6 concludes.

2 The institutional background

Italy provides an ideal testing ground for studying the link between bank support and SBs’ export activities. First, the Italian industrial structure is characterized by a large number of small firms, which strongly depend on loans from local banks to finance their investments and business activity. In 2010, the ratio between the stock market capitalization and the gross domestic product was 15.4 %, compared with 117.5 % in the US (The World Bank 2012). Moreover, another relevant feature of the Italian banking system is its delimitation within local areas. In practice, according to the Bank of Italy data, more than 90 % of credit granted involves banks and firms located in the same province (Presbitero and Zazzaro 2011).Footnote 3 The central role of the local credit market in the financing of investment and export, in conjunction with the strict banking regulation introduced in the late 1930s, allows us to identify exogenous restrictions on the local supply of banking services, which can be used as instruments. In fact, as explained in Guiso et al. (2004), until the late 1980s the Italian banking regulation imposed strict limits on the banks’ ability to grow and lend.

About export activities, in recent years, the Italian economy displayed a strong increase in export. In particular, the total export in goods was equal to 20.0 billion dollars in 2000 and to 37.2 billion dollars in 2010. Among European Union countries, only Germany (104.81 billions) and France (43.58 billions) show a higher value of exported goods. In 2008, 4.2 % of Italian firms reported some export activity. The share of exporting firms varies with firm size. In particular, considering small and medium-sized firms, the percentage of exporters was equal to 2.7 for firms with <10 employees, to 23.5 for firms with 10–19 employees and to 38.9 for firms with 20–49 employees.

3 Data and empirical methodology

3.1 The empirical strategy

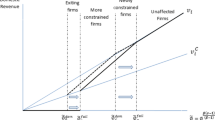

To verify the role of banks in supporting firms’ export activities, we focus on both the extensive and the intensive margin. The probability that firm i exports to a foreign market can be modeled as:

where BS i is a measure of bank support (e.g., a continuous measure of the tightness of the firm-bank relationship or a binary variable equal to one if the firm’s main bank provides support to firm’s export activity), X i is a vector of control variables, \(\varepsilon_{i}\) is a normally distributed random error with zero mean and unit variance, and \(\Upphi (.)\) represents the standard normal cumulative distribution function.

Bank support to export activities can be potentially endogenous, leading to inconsistent estimates. In fact, export and bank support decisions can be jointly determined. The literature offers predictions on these possible common determinants. These include firm characteristics and local market conditions. A characteristic of a firm that may affect both export and bank support is production efficiency. On the one hand, higher efficiency implies a higher probability of exporting (Melitz 2003). On the other hand, higher efficiency increases the likelihood to receive bank support. In turn, local market conditions may also make a common determinant of exporting and receiving bank support. For example, tax policy can determine export decisions (Grubert and Mutti 1991), but also affects firms’ corporate financing choices (MacKie-Mason 1990). We test the exogeneity of our regressor (and eventually correct it to obtain consistent estimates) by relying on instrumental variable (IV) techniques. That is, the probability of using the bank to receive support in exporting is likely to be determined by the characteristics of the local banking system. We model this probability using the following linear model:

where I p is the vector of IV and μ i is a normally distributed error terms with zero mean and unit variance. To ensure the validity of the chosen instruments, we have to perform diagnostic checks. We report an F test of linear restrictions. Under the null hypothesis that instruments are jointly equal to zero, the test statistic is distributed as a χ2 with three degrees of freedom. Finally, the endogeneity of the instrumented regressor is verified through a Wald test on the probability that the correlation coefficient \(\hbox{corr}[\varepsilon_{i},\mu_{i}]\) is equal to zero. The effect of bank support on the probability of export can be identified under the assumption that the set of instruments I p is excluded from Eq. (1).

3.2 Data description

The main data source of this article is the VII UniCredit Survey on SBs, a survey carried out by the Italian banking group UniCredit in 2010. Every year this survey gathers data on a sample of Italian firms that are customers of the bank, having turnover up to 5 million euros. The 2010 wave consists of 6,157 enterprises; interviews were carried out between June and September 2010. The sample is representative of the referred bank’s portfolio, whose composition is well diversified by sector, given the large dimension of the bank in terms of loans, deposits and branches. The sample was designed according to a stratified selection procedure, so that findings are representative at company size level, individual sector level (where the sectors considered are agriculture, manufacturing, services, trade and construction) as well as at the territorial level (province).Footnote 4

The main strength of this database is its very detailed information on individual firms. In particular, the 2010 wave features information on the firm’s: (1) ownership/organizational structure and number of employees, (2) propensity to innovate, (3) extent of productive internationalization and exports, (4) partnership with other firms and whether it is part of a district or a global value chain and (5) financial structure and relationships with the banking system. The definitions of the variables are reported in Table 1.

Table 2 reports the summary statistics for the variables included in our regressions. The geographic distribution of the firms reveals a prominence of the North of Italy (54 % of the total), while other firms are based in the Center (16 %), South and Islands (30 %). By construction of the sample, the average dimension of the firms, measured by its number of the employees, is very small: it is 4.45 at the mean, while the median is just 2 employees. Only 17 % of the firms in the sample are corporation. The sector composition is affected by the nature of the sample. In fact, small firms are usually overrepresented in sectors such as Commerce (31 % of total firms in the sample) and Services (24 %) compared to medium or large firms. Finally, agriculture manufacturing and construction have almost the same representation in the sample (about 15 % for each sector). In general, however, the composition is representative for both sample size and shares of the underlying population, so that sector peculiarities should not affect our analyses. Table 3 reports the correlation matrix.

3.3 Export

Our aim is to empirically verify the role of the banking system in supporting firms’ export activities. The survey provides us with information on whether the firm operated in foreign markets in 2010, and, if yes, on the destination of its exports and the extent of its foreign sales. The questionnaire asks: “Did the firm export at least part of its products in the year 2010?” Nearly 17 % of the firms in the sample exported in 2010. In particular, this percentage is equal to 9 % for firms with <10 employees as against 33 % for the other firms.Footnote 5 Across sectors, the propensity to export is highest in manufacturing (31 % of the manufacturing firms sell in foreign markets) and minimum in the construction sector (9 %).

In the second part of the article, we consider the geographical dimension of exports (Table 4). In particular, the table reports information on firms’ export destinations grouped by geographical area and the amount of foreign sales. The most popular destination is Western Europe (e.g., Germany, France, UK, etc.) followed at a long distance by Eastern European Countries (77.0 and 34.9 % of exporters, respectively). If we control for multiple responses, we have that 36.7 % of exporters skip the main European countries and sell only to other and more distant foreign markets. Moreover, most firms focus on one (43.9 %) or two (23.2 %) geographical areas. Average foreign sales accounted for 26.7 % of exporting firms’ total turnover. Using this information, we construct two variables. The first is Geo, an indicator constructed to take into account the actual number of foreign markets in which each firm sells.Footnote 6 Then, we focus on the intensive margin of exports. In this case the dependent variable is Foreign Sales, the share of export sales over total turnover, taken in logarithm to account for non-linear effects.

3.4 Bank support

In the first part of our analysis, the key explanatory variable is the tightness of the credit relationship between the firm and its main bank, measured by the duration of the relationship. The survey asks each firm, “For how many years has this been the main bank with which the firm operates?”Footnote 7 Thus, our measure of duration is the length in years of continuous relationship between the firm and its main bank. The mean (median) duration is 14 (11) years; the lowest quartile has a credit relationship shorter than 6 years, and the top quartile has a relationship longer than 21 years. The literature regards the length of the credit relationship as a good proxy of its strength (Degryse and Ongena 2005; Herrera and Minetti 2007; Gambini and Zazzaro 2011). In fact, a bank can accumulate information over time by observing the behavior of the firm, such as its compliance to contractual obligations (Petersen and Rajan 1994).

In the second part of the article, we study the channels whereby bank support affects export.Footnote 8 Table 5 reports the main institutions that provide support to firms’ export activities. Responding to the question “Which of these institutions provide support to your export activity?”, 13.5 % of entrepreneurs indicated the banking system, followed by 11 % pointing to associations and 8.4 % indicating consultancy firms. Only a marginal role is played by finance public holding companies for export promotion such as simest, finest, sace, etc. (2.8 %), chambers of commerce (2.8 %), the Foreign Trade Institute (1.8 %) and the embassies (1.2 %). So, banks—and especially the internationalized ones—seem to hold a primary position in export enhancing. However, much can still be done: 44.4 % of exporting firms declare they operate autonomously, which may depend on an inbreed tendency of “doing on her own” as well as on the lack of information about ad hoc products and services. About the characteristics of bank services to support small business exports, Table 6 shows the firms’ evaluations of these services. Beyond ordinary services such as online payments (62.7 %, net percentage),Footnote 9 credit insurance (46.0 %) and international guarantees (31.9 %), the data show that there is a substantial request for advisory services, in the form of counter-parties signaling (30.4 %), legal and financial advisory (26.7 %), in loco support during fairs (15.6 %), investment opportunities abroad (13.1 %) and training services for commercial and administrative personnel (8.8 %). Possibly, such support can be provided at best only by internationalized banks.

Considering these data, we construct a dummy variable that takes the value of one if the firm avails itself of banks in its export activity, zero otherwise. As discussed above, banks may enhance SB export activity by diminishing the entry costs to foreign markets through ad hoc products and services tailored to the needs of this specific segment of firms. Beyond ordinary services, advisory and in loco support are of particular relevance. Since these latter kinds of support are likely to be provided only by a bank having an international network and a specific knowledge of foreign markets, we test the robustness of this hypothesis by controlling for the type of firms’ main bank, distinguishing between internationalized banks and domestic banks.Footnote 10

3.5 Control variables

Our set of control variables includes several firm characteristics that are likely to affect exporting behavior. A very important factor that we should consider is firm size. Bernand and Jensen (1999) underline that exporters are larger. For this reason, we control for firm size, defined as the logarithm of the firm’s employees as of the end December 2009. Moreover, we include dummy variables, indicating whether a firm is a corporation, or whether it belongs to a partnership, to a global value chain, to an industrial district or to an international franchising network. The small size of Italian firms reduces their ability to participate in the global markets. Traditionally, to fill this gap, Italian small firms tended to aggregate in networks, such as strategic partnership, consortia or industrial districts (Baffigi et al. 1999). Footnote 11 These forms of cooperation may allow SBs to share the distribution network with other firms and thus lower the cost for entering foreign markets. We add also a dummy variable taking value one if the firm is family owned. There is a growing literature on the internationalization process by family businesses, on its characteristics and outcomes. The final effect of family ownership on the probability of exporting is still not clear (see, e.g., Zahra 2003; Minetti et al. 2013).

Another important aspect to consider in exporting decisions is the firms’ financial health (Greenaway et al. 2007). In particular, we use a proxy of firm’s financial tension, a dummy variable equal to one if the main bank reduced the granted credit line to the firm during 2010 (Bartoli et al. 2013). We also include the number of banks with which the firm relates. To check for other differences among firms, we include four sector dummies (Manufacturing, Construction, Services and Agriculture) and the natural logarithm of age, where the age of the firm is measured as the number of years since inception (Doblas-Madrid and Minetti 2013).

Finally, to better control for local economic and banking development, we include the provincial value added and the Herfindhal–Hirschman index on bank loans in the province during the 1985–1998 period. Last, some factors, including the quality of infrastructure, could differ across the three macro areas of Italy (North, Center and South). Thus, we control for geographical heterogeneity using area dummies indicating whether a firm is headquartered in the Northwest, Center or South of Italy.

3.6 Instrumental variables

In order to tackle endogeneity issues, we need an appropriate set of instruments. Our strategy relies on identifying shocks to the local supply of banking services. In fact, we suppose that these shocks directly influence local banking development.Footnote 12 We have in mind two possible channels through which local credit market development can affect bank support to export. First, the density of the local banking system directly influences firms’ decisions to continue with their main banks and, hence, the duration of credit relationships (see, e.g., Herrera and Minetti 2007; Presbitero and Zazzaro 2011). For example, suppose that a bank opens new branches in the local market. A firm could select that bank as its new main lender to reap the benefits of proximity or the hours of operation of its new branches. Second, local banking development affects firms’ ability to obtain banks’ advisory services specific for export promotion (see, e.g., Beretta et al. 2005; Grisorio and Lozzi 2012). By contrast, we do not expect these restrictions to affect directly firms’ exports.

In particular, the set of instruments we use in the present empirical analysis are taken from Herrera and Minetti (2007). In practice, we use the annual number of branches created by incumbent banks net of branches closed and the annual number of branches created by entrant banks in the province where the firm is headquartered (per 1,000 inhabitants), taking the average in 1991–2004. Since the number of provinces rose from 95 to 107 over 1991–2006, we impute data on firms headquartered in new provinces referring to their original province. To justify these instruments, we have to discuss the Italian regulation. In 1936 the government enacted a strict entry regulation: the objective of this banking regulation was to enhance bank stability through severe restrictions on bank competition. Until the liberalization process in the 1980s, the regulation directly constrained the opening of new branches in the local market, with variable tightness across provinces.Footnote 13 By contrast, between the end of the 1980s and the late 1990s, that is, after the deregulation, the total number of branches grew by about 80 %. The number of branches created in the deregulation period plausibly reflects the local tightness of regulation, as well as the banking concentration process. Interestingly, the density variable displays a large interprovincial dispersion. Moreover, this dispersion has been increasing with time. In particular, during the 1991–2004 period, the variation among provinces was more important than the overtime variation (Benfratello et al. 2008).

Finally, to better measure local banking development, we also consider judicial efficiency. In particular, we proxy court efficiency by the number of civil suits pending in each of the 27 judicial districts of Italy per 1,000 inhabitants. A high number of pending suits could reflect an inefficient enforcement system (Bianco et al. 2005). This variable is imputed to the firms according to the judicial district where they are headquartered. The rationale for using this instrument is that efficiency of the courts, affecting the verifiability of the entrepreneur’s actions and output, reduces the banks’ exposure to moral hazard problems in providing credit to firms.

4 Empirical findings

4.1 The duration of the credit relationship and export

In Table 7, we examine the effect on exports of the tightness of the credit relationship with the main bank. In particular, we regress the length of the relationship on the extensive margin of export (columns 1–3) and the intensive margin (column 4). Column 1 of Table 7 displays the estimates in which the measure of the tightness of the credit relationship is treated as exogenous. The list of controls is described in Sect. 3.5. We find that the relationship length has a positive and statistically significant effect on the probability of exporting. The positive impact on export is significant (z statistic = 2.46), and the coefficient is equal to 0.005. The estimated effect of the relationship length on firms’ export propensity is in line with the predictions of the theoretical literature, suggesting that due to fixed costs of entering foreign markets, credit constrained firms are less likely to export. Furthermore, the opaqueness of international investments can induce a financier to be less inclined to put its own money at risk, trusting a firm that wants to enter a foreign market (Manova 2012; Chaney 2005). Thus, the bank’s information can be essential in raising firms’ ability to borrow to finance export costs. Although the theoretical literature predicts a positive effect of the length of the bank-firm relationship on exports, the empirical literature fails to find supporting evidence on this. A possible explanation for the difference between our results and the literature is the nature of our data set. In fact, the positive effect of a tighter credit relationship could be stronger for SBs, because small firms are more sensitive to credit rationing (see, e.g., Levenson and Willard 2000).

The results for the control variables are generally consistent with the findings of the extant empirical literature. As for firm characteristics, the estimates suggest that larger firms are more likely to export. In fact, consistent with other firm-level studies (e.g., Bernard and Jensen 1999), we find that firms with more employees are significantly more likely to export. Moreover, aggregating in networks, such as in a strategic partnership or global value chain, increases the probability of exporting (Altomonte et al. 2012). Looking at the variables proxying for external finance, we consider the number of banking relationships and obtain that the likelihood of exporting is increasing in the number of relationships, which is consistent with the view that multiple banks reduce the incidence of lenders’ moral hazard (hold-up) (Rajan 1992; Petersen and Rajan 1994). Perhaps surprisingly, the estimated coefficient for our measure of financial tension is positive. Regarding the variables controlling for the characteristics of the environment in which firms operate, we find that bank branch density in the province has a negative effect on the probability of exporting. The coefficient on the growth rate of the value added of the province is not significant, such as the dummies for Northwest, Center and South.

The reader may wonder whether the probit estimates are biased because of the omission of variables that could be correlated with both exports and the length of the credit relationship. The instrumental variable estimation allows us to address this issue. As we explain above, we choose our instruments considering a set of variables reflecting the local banking development in Italy. Columns 2a and 2b report the results for the two-stage conditional maximum likelihood model in Eqs. (1) and (2). In particular, column 2a displays the first-stage coefficients on the excluded instruments and on the other variables. The duration of the relationship is increasing in the number of branches created by incumbent banks and decreasing in the number of branches created by entrant banks and in the level of pending suits in the judicial district. The instruments are jointly highly significant (p value = 0.0020), with a first-stage F statistic = 5.37. Unlike the probit model where endogeneity issues are ignored, the estimates from the 2SCML model, reported in column 2b, show no evidence that the relationship length has a statistically significant effect on exports. However, the diagnostic tests do not establish the need for an IV approach. In fact, the Wald test of endogeneity for the instrumented regressor cannot be rejected.Footnote 14 In column 3, as a robustness check, we regress the model for the subsample of manufacturing firms only, where the propensity to export is higher compared to other sectors. The results confirm that the probability of exporting increases in the duration of the relationship with the main bank. Moreover, the estimated coefficient is larger (coefficient = 0.008) and statistically significant (z = 1.64).

In column 4, we investigate the impact of the tightness of credit relationship on the intensive rather than on the extensive margin of export. We regress the effect of the length of credit relationship on foreign sales, defined as the ratio of exports over turnover, taken in logarithm to account for non linear effects. In practice, we replace Eq. (1) with the following equation:

where y i is the logarithm of exports’ turnover over total turnover, BS i is the duration of the firm-bank relationship, X i is the vector of control variables in Eq. (1) and ν i is a normally distributed random error with zero mean and unit variance. We estimate this equation with an OLS model.Footnote 15 There is no evidence that the length of a credit relationship has a statistically significant effect on foreign sales. By contrast, similar to the result for the export participation decision, firms belonging to a global value chain sell more abroad. The difference in the results for an extensive and intensive margin of exports is in line with the theoretical prediction. In fact, while the literature shares the same view about the credit constraints and the role of banks on the extensive margin of export, the impact of credit constraints on the volume of exports is ambiguous: some theoretical models predict that credit-constrained firms export less (see, e.g., Manova 2012); others imply that liquidity constraints are neutral for the volume of foreign sales (see, e.g., Chaney 2005). In particular, Chaney (2005) underlines that conditional on exporting, only the productivity of a firm impacts the volume of foreign sales. In fact, once a firm has gathered enough liquidity to pay the fixed cost of exporting, it will be able to cover the variable costs of expanding the scale of production with its own funds. We add an additional reason to explain our different results for an extensive versus intensive margin. As explained above, the main bank can also have a cultural role in enhancing SBs’ internationalization. These results seem to suggest that a tighter relationship with the main bank impacts largely whether but not how much selling abroad.

4.2 Bank support

As we show in the data description, despite the difficulties associated with firm’s size, a non-trivial part of SBs in our sample engages in export activity. However, exporting is generally confined to one single type of market, which mostly corresponds to the main European countries. Given these barriers in terms of sunk costs, it seems interesting to examine what role can be played by banks, especially the internationalized ones, in promoting SBs’ exports to multiple markets. Table 8 reports the regression results addressing this issue. As said, in this part of the article, we study the role of the banking system introducing a dummy variable that takes the value of one if the firm avails itself of the banks in its export activity. This dummy is introduced as a regressor while the dependent variable is Geo, capturing the extent of multimarket exporting. Since the dependent variable is bounded by construction, we estimate a Tobit model. Column 1 displays the estimation of the equation in which the measure of bank support is treated as exogenous. The coefficient of “bank support” is positive, but not significant. In the Tobit estimation, the coefficient of our measure of bank support is 0.007; the t statistic is 0.30. As the Tobit estimation is likely to be biased because of the omission of variables, we check for the endogeniety of bank support. The test suggests that error terms are significantly correlated, which confirms that there are missing latent factors affecting both export participation decisions and requests of bank support, hence justifying the IV estimation. Columns 2a and 2b of Table 8 report the results for the 2SCML Tobit model. After controlling for endogeneity, our indicator of bank support is positive and statistically significant at the 10 % level, with an estimated coefficient of 0.634. This result confirms the hypothesis that bank support increases the probability of firms’ exporting to multiple markets. There may be various reasons behind this positive effect. For example, the bank support could facilitate the firm’s access to more sources of financing that are essential to its export activity. Moreover, bank support to export can increase the incentive of the financiers to monitor the firm, increasing firm productivity.

In Table 9, we investigate the role of bank support on the intensive margin of exports by looking at the effect of bank support on foreign sales. We also control for the endogeneity of bank support. The results confirm the role of bank services also for the intensive margin of exports: bank support has a positive and significant impact on foreign sales. In particular, in the IV estimation, the coefficient of bank support is equal to 1.514 and significant at the 10 % confidence level. Regarding the control variables, we find that firms belonging to a global value chain, firms in industrial districts and firms structured as corporations sell more abroad.

5 Disentangling the channels

In this section, we try to better grasp the mechanisms through which bank support affects export decisions. First, we disentangle bank support considering separately the bank services, since these could have a different impact on the firm’s propensity to export. Second, we investigate the role of internationalized banks. In Tables 8, 9 and 10, we study the contribution of these mechanisms.

5.1 Bank services

As pointed out above, advisory services for export promotion and in loco support are of particular relevance for SBs. For this reason, supporting the internationalization of small firms is an objective of many public policy initiatives in most countries. In particular, many public programs aim to foster either the growth of export sales at firms exporting only occasionally or the start of exporting to new markets at firms that previously sold to one foreign market only. Although specifically targeted to SBs, these programs are often little used by SB owners and have slight impact on the trading behavior of firms that use the programs (Fischer and Reuber 2003). The main problem is that SBs are less adept than large firms in accessing government assistance (OECD 1997). Here, the role of the banking system could be very different. In fact, SBs are used to entertain relationships and receive multiple services (not only financial services) from the banks.

In this section, we explore the role of each bank service in explaining the export decisions. In particular, we use the question in Table 6 (How much useful do you judge the following bank services to support small business export activities?) and construct four variables. In answering the question, the firm was required to give a weight (going, in descending order, from 1, very much, to 4, not at all) to 16 characteristics. We classify the services in four categories: on line services (services 1–3), in loco services (services 4, 5 and 10), traditional banking services (services 6–9) and advisory services (services 11–16). In practice, we construct 16 dummy variables that take the value of one if the firm answered “very much” to the respective characteristic, zero otherwise. Next, we calculate four indicators, as the average for each category. In Table 10, we regress the indicators for the four banking services on the actual number of markets in which each firm operates.Footnote 16 All the four indicators have a positive and significant impact on the number of markets. The coefficient of traditional banking services is the largest and is equal to 0.096; next comes the coefficient of advisory services, which is equal to 0.089.Footnote 17 These results show that banks seem to boost firms’ exports in two main ways. First, banks have an operational role, they may facilitate the transaction between the exporting firm and its foreign customers and provide financial support to export and payment services. The second channel is of “informational” nature, where the positive role is played by the bank’s knowledge of the foreign market. In fact, the bank can advise the internationalizing firm on investment opportunities abroad or could also contribute to the screening and the monitoring of the foreign partners.

5.2 The role of internationalized banks

In the previous section, we find that the banking system can provide advisory services for export promotion and in loco support that prove essential for firms to export to new markets. This could be particularly true for internationalized banks. In fact, thanks to their knowledge of foreign markets, internationalized banks could advise their customers on business opportunities abroad as well as consult them on foreign regulations. Moreover, banks that are active in the foreign country are likely to provide better and more complete “traditional” banking services (Beretta et al. 2005). Hence, the support of banks with structures in foreign countries could boost firms’ exports in a very effective way. To examine this issue, we split the sample into two sub-samples with respect to the type of firm’s main bank, distinguishing between internationalized and domestic banks. Having verified the endogeneity of bank support with respect to export diversification, we then re-estimate the equations in Tables 8 and 9 for each sub-sample. The results in columns 3 and 4 of Table 8 confirm our view: the role of the bank in enhancing export activity is positive and significant (at <1 % confidence level) only in the case of an internationalized bank, which is the only one that can provide services such as advisory or in loco support, which seem crucial to enter distant markets.Footnote 18 The empirical analysis confirms the theoretical prediction of a positive relationship between bank internationalization and the number of markets to which the firm exports. We obtain similar results for the intensive margin of exports. In fact, if we focus on the internationalized bank subsample, bank support turns out to be significant at <5 % confidence level (columns 3 and 4 of Table 9). Thus, the services provided by internationalized banks not only appear more effective than those provided by locally based banks in enhancing the probability of entry into multiple markets, but are also conducive to a higher intensity of exports.

6 Conclusions

To overcome the slack dynamics of domestic demand, firms can try to empower their exports. However, exporting entails sunk costs—investments to tailor products and distribution chains to the specificity of each foreign market—and special financial needs—shifting (often intangible) assets abroad aggravates the asymmetry of information vis-à-vis lenders—that may pose the gravest problems to small-sized businesses. This article contributes to the wide literature on the effects of finance for international trade. Although the theoretical literature underlines that exporting is particularly vulnerable to credit imperfections, there is scarce evidence on the role of a tighter credit relationship with the main bank in the internationalization process. Using a unique database on a sample of small firms, we investigate whether bank support does help firms exporting. Specifically, we study two main points. First, we test for the impact on export of the information held by the main bank, as proxied by the duration of the credit relationship. We find that firms with longer credit relationships have a higher probability of exporting. Second, we investigate whether bank support to exports affects the probability that a firm sells abroad in more than one geographical areas, thus denoting a more sophisticated exporting stance with respect to firms exporting to fewer foreign markets. We also study whether bank support impacts firms’ exports at the intensive margin. We find that bank services significantly promote SBs’ exporting at both the extensive and the intensive margin. In particular, the results show that traditional banking services and advisory services are the most effective for firms’ exporting decisions. Furthermore, and not surprisingly, in all the cases considered the results are stronger when the firm’s main bank is itself internationalized.

Our results suggest that the internationalization of SBs is favored by the existence of strong bank-firm relationships, in particular when the bank is itself internationalized. Thus, the intensity of the bank-firm relationship and the nature of the main bank seem to be strategic features for SBs. Moreover, our results bring some hope to the debate about economic stagnation. In fact, as the largest European banks invested extensively in retail networks abroad, those foreign networks could enable them to contribute boosting the export ability of SBs, thus improving the growth potential of the national economies. In that sense, FDI by national banks could turn out even more advantageous than other FDI types.

The analysis represents a first step in a potentially fruitful line of research. While there is a large amount of evidence on the role of liquidity constraints on firm exports, we still know little on the channels through which this influence unfolds. For example, one could investigate how the bank services have a different impact on the firm’s propensity to export and not only on the intensive margin of export. In turn, the benefits offered by internationalized banks in terms of kindling new cross-border opportunities for SBs could themselves come at a cost. This could materialize if acquiring the international dimension were to imply for the national bank also becoming much bigger and generating more systemic risk. This potential tradeoff might be worth studying. We leave these intuitions and other important issues to future research.

Notes

Often the main obstacle to SBs’ internationalization is the entrepreneur’s grasp of global opportunities. Mostly in SBs, we can argue, the founder/current owner deeply impacts firm strategy (Fischer and Reuber 2003). In turn, a tight relationship with the main bank, affecting the owner’s propensity to export, can increase the probability of SB internationalization.

In a different context, Minetti (2007) suggests that a contraction in bank loans might induce some firms to shift from high-quality projects (such as export activities) to low-quality projects.

Provinces are local entities defined by Italian law and are similar in size to US counties.

The data set is obtained by treating a wider record file: we have filtered outliers and misreported cases.

To check the representativeness of this figure for the universe of Italian firms, we combined these data with data from the Italian National Statistics Office (ISTAT). We find that in our data set the percentage of exporters is in the range of what is found at national level for firms with more than ten employees (30.4 % in 2008). Instead, the internationalized micro-firms (firms with <10 employees) are over-represented (9 vs. 3 % at national level). For this reason, we reestimated the regressions excluding the firms with <10 employees. Results, available upon request, are qualitatively similar.

Geo is based on answers to the question, “Which are the geographical areas of export?”, whose results are reported in Table 4. For each item, we constructed a dummy variable that takes the value of one if the firm exports to the area, zero otherwise. Then, we take the average of the ten resulting dummy variables.

The survey suggests identifying the bank with the largest share of debt in 2010 as the “main bank” of the firm.

Even if it can be reasonably argued that the presence of ad hoc banking services affects also the extensive margin of export, source data do not allow us to analyze it, since only internationalized firms were asked about bank’s services evaluations. Then, in the second part of the article, we focus on exporting firms.

Net percentage calculated as the difference between entrepreneurs who responded “very much” and “enough” and the one who responded “little” and “not al all.”

We consider internationalized a bank with structures in foreign countries, such as foreign branches or representative offices abroad. In particular, the survey informs us on the type of main bank entrusted by the firm, distinguishing among Italian banks with branches in foreign markets, foreign banks, national level banks and local banks. We code internationalized banks the first two types of this list and code domestic banks the other two types.

Industrial districts are communities of small firms acting in spatially concentrated areas and specialized in a specific sector.

Relating to the exogeneity of our instruments, the 1936 banking regulation was not designed having in mind the needs of the various provinces, as it was determined by historical accidents, such as the varying bank connections to the Fascist regime.

Under the null hypothesis that the specified endogenous regressor can actually be treated as exogenous, the test statistic is distributed as a χ2 with three degree of freedom.

Also for this equation we control for the endogeneity of the duration of the credit relationship. The endogeneity test did not suggest the need for an IV approach; thus, we did not report the 2SLS estimations. Results, available upon request, are qualitatively similar.

Having verified the exogeneity of each bank service with respect to export diversification, we use Tobit model for these regressions.

We run similar regression for foreign sales. The results, available upon request, show that none of bank services impacts foreign sales.

The estimate for the sub-sample of domestic banks may however be affected by small sample bias.

References

Altomonte, C., Di Mauro, F., Ottaviano, G., Rungi, A., & Vicard, V. (2012). Global value chains during the great trade collapse: A bullwhip effect? Working Paper Series, 1412, ECB.

Baffigi, A., Pagnini, M., & Quintiliani, F. (1999). Industrial districts and local banks: Do the twins ever meet? Working paper, 347, Bank of Italy.

Baldwin, R., & Krugman, P. R. (1989). Persistent trade effects of large exchange rate shocks. Quarterly Journal of Economics 104(4), 635–654.

Bartoli, F., Ferri, G., Murro, P., & Rotondi, Z. (2013). Bank-firm relations and the role of mutual guarantee institutions at the peak of the crisis. Journal of Financial Stability, 9(1), 90–104.

Bellone, F., Musso, P., Nesta, L., & Schiavo, S. (2010). Financial constraints and firm export behaviour. World Economy, 33(3), 347–373.

Benfratello, L., Schiantarelli, F., & Sembenelli, A. (2008). Banks and innovation: Microeconometric evidence on Italian firms. Journal of Financial Economics, 90, 197–217.

Beretta, E., Del Prete, S., & Federico, S. (2005). Bank internationalization and export propensity: An analysis on Italian provinces. In L. F. Signorini (Ed.), Local economies and internationalization in Italy. Rome: Bank of Italy.

Bernard, A. B., & Jensen, B. J. (1999). Exceptional exporter performance: Cause, effect, or both? Journal of International Economics, 47, 1–25.

Bianco, M., Jappelli, T., & Pagano, M. (2005). Courts and banks: Effect of judicial costs on credit market performance. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 37(2), 223–244.

Chaney, T. (2005). Liquidity constrained exporters. Mimeo: University of Chicago.

De Bonis, R., Ferri, G., & Rotondi, Z. (2010). Do bank-firm relationships influence firm internationalization? MOFIR Working Paper 37.

Degryse, H., & Ongena, S. (2005). Distance, lending relationships, and competition. Journal of Finance, 60, 231–266.

Dixit, A. (1989). Entry and exit decisions under uncertainty. Journal of Political Economy, 97(3), 620–638.

Doblas-Madrid, A., & Minetti, R. (2013). Sharing information in the credit market: Contract-level evidence from US firms. Journal of Financial Economics. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2013.02.007.

Fischer, E., & Reuber, A. R. (2003). Targeting export support to SMEs: Owners’ international experience as a segmentation basis. Small Business Economics, 20, 69–82.

Gambini, A., & Zazzaro, A. (2011). Long-lasting bank relationships and growth of firms. Small Business Economics. doi:10.1007/s11187-011-9406-8.

Greenaway, D., Guariglia, A., & Kneller, R. (2007). Financial factors and exporting decisions. Journal of International Economics, 73(2), 377–395.

Grisorio, M. J., & Lozzi, M. (2012). Propensity to export of Italian firms: Does local financial development matter? Rivista Italiana degli Economisti, 2, 299–330.

Grubert, H., & Mutti J. (1991). Taxes, tariffs and transfer pricing in multinational corporate decision making. Review of Economics and Statistics, 73, 285–293.

Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2004). Does local financial development matter? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119, 929–969.

Herrera, A. M., & Minetti, R. (2007). Informed finance and technological change: Evidence from credit relationship. Journal of Financial Economics, 83, 223–269.

Levenson, A. R., & Willard, K. L. (2000). Do firms get the financing they want? Measuring credit rationing experienced by small businesses in the US. Small Business Economics, 14, 83–94.

MacKie-Mason, J. K. (1990). Do taxes affect corporate financing decisions? Journal of Finance, 45, 1471–1493.

Manova, K. (2012). Credit constraints, heterogeneous firms and international trade. Mimeo: Stanford University.

Melitz, M. (2003). The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica, 71(6), 1695–1725.

Minetti, R. (2007). Bank capital, firm liquidity, and project quality. Journal of Monetary Economics, 54(8), 2584–2594.

Minetti, R., Murro, P., & Paiella, M. (2012). Ownership structure, governance, and innovation: Evidence from Italy. MEF Working Papers, No. 10/2012.

Minetti, R., Murro, P., & Zhu, S. C. (2013). Family firms, corporate governance, and export. CASMEF Working Papers, No. 2/2013.

Minetti, R., & Zhu, S. C. (2011). Credit constraints and firm export: Microeconomic evidence from Italy. Journal of International Economics, 83, 109–125.

OECD. (1997). Globalisation and small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Volume 1: Synthesis report and volume 2: Country studies. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Petersen, M., & Rajan, R. (1994). The benefits of firm–creditor relationships: Evidence from small business data. Journal of Finance, 49(1), 3–37.

Pope, R. A. (2002). Why small firms export: Another look. Journal of Small Business Management, 40(1), 17–26.

Portes, R., & Rey, H. (2005). The determinants of cross-border equity flows. Journal of International Economics, 65, 269–296.

Presbitero, A., & Zazzaro, A. (2011). Competition and relationship lending: Friends or foes? Journal of Financial Intermediation, 20, 387–413.

Rajan, R. (1992). Insiders and outsiders: The choice between informed and arm’s length debt. Journal of Finance, 47(4), 1367–1400.

The World Bank. (2012). Market capitalization of listed companies (% of GDP). http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/CM.MKT.LCAP.GD.ZS.

Zahra, S. A. (2003). International expansion of US manufacturing family businesses: The effect of ownership and involvement. Journal of Business Venturing, 18, 495–512.

Acknowledgments

We are particularly indebted to the editor and the two anonymous referees for providing us important insight. We wish to thank conference participants at the 4th International IFABS Conference held in Valencia in June 2012 and the Workshop on Economics of global interactions: New Perspectives on Trade and Development held in Bari in September 2012. Without naming them individually, we thank several experts within UniCredit Group for crucial assistance in constructing the questionnaire as well as for key insights in setting up our analysis. In spite of this, the usual disclaimer applies. Namely, the views put forward in the article belong exclusively to the authors and do not involve in any way the institutions of affiliation. Pierluigi Murro gratefully acknowledges financial support from UniCredit and University of Bologna, Grant on Retail Banking and Finance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bartoli, F., Ferri, G., Murro, P. et al. Bank support and export: evidence from small Italian firms. Small Bus Econ 42, 245–264 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-013-9486-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-013-9486-8