Abstract

In this paper we explore the impact of the banking sector development on the first time export entry of small enterprises (SEs) in the Turkish manufacturing sector. By exploiting variation in the number of branches per capita across NUTS3 regions and variation in financial dependence across sectors, we support a positive and significant role of finance in fostering the access to foreign markets of SEs. This evidence is robust to the use of alternative measures, the control for omitted variables and the correction for endogeneity. We show that the banking sector reduces the incidence of sunk entry costs by providing both credit and destination-specific information. Finally, we provide original evidence on the role of the territorial diffusion of foreign banks’ branches on SEs’ exports. While no direct effect is detected, we disclose a minor and indirect effect of foreign branches working through their influence on the banking sector development at the local level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Firms’ internationalisation is a key process for countries’ growth and development and can importantly contribute to the structural change of their economies. Crossing national borders represents, however, a difficult task characterised by the presence of burdensome entry sunk costs and uncertainty about future profits (Melitz 2003; Roberts and Tybout 1997; Das et al. 2007; Impullitti et al. 2013). Although theory and empirics have shown that firm level productivity differences significantly explain heterogeneous patterns of market entry (Melitz 2003; Bernard et al. 2003), still relevant room exists for further factors affecting firms’ export entry dynamics (Lawless 2009; Armenter and Koren 2015). In this paper we hinge on a network approach to firm internationalisation (Johanson and Mattsson 1988; Axelsson and Johanson 1992) and explore the role of the banking sector development at the local level in favouring firms’ export entry.

There are two main channels for the banking system to favour small enterprises’ (SEs) export activity. On one hand, banks provide financial resources to perform the necessary preparatory activities to access foreign markets, to bear entry costs, to tackle higher demand uncertainty in unknown markets and to face the long time elapsing between an export order and the corresponding payment. On the other hand, banks represent important sources of information and knowledge transfers about foreign countries (Martin 1999). The provision of financial resources and information is essential for SEs that are generally poorly endowed with internal resources (Pollard 2003).

With this paper we contribute to the literature which studies firms’ size as a relevant dimension in the analysis of the consequences of financial markets’ frictions on the export activity of firms (Bartoli et al. 2014; Damijan et al. 2015; Minetti and Zhu 2011). Most works on the topic are mainly focused on the financial channel and neglect the role of the banking sector as a provider of information and advisory services which has been,instead, emphasised by recent contributions (Bartoli et al. 2014; Tomohiko et al. 2014; Paravisini et al. 2015).

We therefore aim at investigating whether the banking system at the local level promotes SEs’ internationalisation tout-court, by jointly capturing the credit and information channels. To identify the impact of the banking sector on SEs’ export entry, we exploit the variation across Turkish NUTS3 provinces in the development of the banking system and the variation across sectors in their financial dependence. Our identification strategy is similar to the one originally implemented by Rajan and Zingales (1998) in the investigation of the linkage between countries’ financial development and sectoral economic growth. We expect that firms operating in more financially dependent sectors benefit more from a well developed banking system in terms of export propensity.

Besides exploring the overall impact of the banking sector development at the local level on the export entry of SEs, we contribute to extant literature in three further respects.

First, we focus our analysis on SEs’ internationalisation in an emerging economy, Turkey. The country experienced a serious political and economic crisis in 2001 with a consequent breakdown of its banking system. The following deep restructuring process allowed the country to rapidly recover from the global 2008 financial turmoil. Furthermore, small firms are the backbone of the economy, they account for nearly 50 per cent of manufacturing employment,Footnote 1 and are prevented from benefiting of the recent roaring performance of the Turkish stock market (Heinemann 2014). Hence, the banking sector becomes crucial in supporting their performance. For these reasons, the Turkish economy represents an interesting and particularly suitable setting to analyse the banking-SEs’ export entry linkage. Concerning the identification of this nexus, we further contribute by neglecting carry-along-trade (CAT) exports and focusing on firms’ regular export activities (Ahn et al. 2011; Bernard et al. 2012, 2015).

Second, we explore the role of internationalised—either domestic or foreign—banks as information providers in fostering the export entry of SEs and we test the relevance of general versus destination-specific market information. Beyond the provision of credit, internationalised banks can transfer information that is essential for crossing national borders. In particular, thanks to their own experience, they are expected to be better equipped with knowledge on foreign markets and can offer effective consulting export services. In this respect, we add to the scant evidence on the topic (Bartoli et al. 2014; Tomohiko et al. 2014; Paravisini et al. 2015).

Third, for the first time to our knowledge we isolate and inspect the effect of foreign banks on the export entry of SEs. Foreign banks are new actors entering the economic system and, beyond providing credit and information, they can increase the extent of competition in the local banking markets where they open branches. This part of the analysis is especially important for the Turkish context where relevant disparities exist across regions and foreign banks have gained an increasing role during the last decades.

Our empirical analysis reveals that a well developed banking system at the local level favours disproportionately more export entry of SEs which operate in more financially dependent sectors. This result is robust to a number of controls and to an instrumental variables (IV) approach accounting for the potential endogeneity of the diffusion of bank branches. The effect of banking development works through the reduction in sunk export entry costs. The credit channel is meaningful and at work. Turning to the information channel, the investigation of the local presence of banks with international branches and/or representative offices reveals that only the transfer of destination market-specific information is relevant. Finally, although foreign banks branches do not directly foster SEs’ internationalisation, they do play a minor indirect role in favouring SEs’ export entry by promoting the expansion of the local banking market they enter.

The paper is organised as follows. The next section presents our conceptual framework and a brief review of the relevant literature. In Sect. 3 we describe the recent evolution of the Turkish banking sector. In Sect. 4 we develop our empirical framework by describing the empirical model, the estimation issues and the data. Section 5 shows the baseline results, explores the relevant mechanisms at work and the role of the diffusion of foreign banks across Turkish regions. Section 6 concludes.

2 Conceptual framework and relevant literature

A strand of literature has depicted firm internationalisation as an incremental process of acquisition of experiential knowledge (Johanson and Vahlne 1977). The network approach complements this view by stressing the relational notion of the firm and highlighting the relevance of a firm’s socio-economic environment in easing its export activity (Johanson and Mattsson 1988; Axelsson and Johanson 1992). A firm’s successful performance depends on its relational capital, that is the width and quality of its relationships with actors in the environment where it operates. The latter, in turn, is importantly affected by local institutions, which, hence, exert a key influence on the comparative advantage of firms and regions (Hall and Soskice 2001). Among institutions, a fundamental role in facilitating a firm’s entry in export markets is played by local financial markets. The vast debate on the relevance of finance for regional economic performanceFootnote 2 has highlighted that regional credit availability can contribute to create and reinforce a cumulative causation circle, thereby fostering path and place dependency for regions and firms within their boundaries. In an era of globalisation and rapid technological advances, the geographical circuit of the financial system is changing and the interplay between the locational structure of financial institutions and their—local and international—regulatory framework may hamper the access to credit opportunities of firms located in peripheral regions (Martin 1999). The evolution of the boundaries of national as well as regional finance brings about the reshaping of all the involved social relations. Indeed, not only money is important in allowing for the postponement of payment over time and space, which is the essence of credit, but it also has the advantage of “allowing propinquity without proximity in conducting transactions over space” (Martin 1999). Money can be viewed as a social relation as it facilitates the storage, coordination and communication of information. As a consequence, information is displaced from the goods being produced and traded to the wider, increasingly global network of monetary relations facilitating exchange (Lee 1999). It follows that the geography of the monetary network bounds the geographical expansion of individuals and firms. In other words, social and cultural geographies are also a reflection of the geographies of money.

This relational view on finance matches the relational view of the firm. The availability of a wide local monetary network allows for the extension of a firm’s relations out of the regional context and indirectly enriches its relational endowment. The relational view of the firm recalls the Varieties of Capitalism approach to political economy (Hall and Soskice 2001), which highlights the fundamental role of informal relations and information for nations falling under the Coordinated Market Economy (CME) stereotype.Footnote 3 Turkey, the country under analysis, can be framed in the class of Mediterranean capitalism where extensive non-market coordination within the sphere of corporate finance co-exists with more liberal arrangements in the sphere of labour relations. Hence, the relational capital of firms and of their network becomes crucial for their access to both finance and information which eases contacts with new domestic and foreign customers. This is especially true for small firms suffering from regional market segmentation, due to their limited internal financial resources (Zazzaro 1997; Pollard 2003) which not only hamper investment possibilities but also export market participation.

Against this background, we propose an empirical test of the impact of local financial development on small firms export activity paying special attention on how the credit and relational roles of finance drive this nexus.

Extant recent empirical work, sofar, has rather overlooked the role of financial frictions for small firms.Footnote 4 Just a few papers analysed this issue. The paper by Manova et al. (2015) shows that larger Chinese firms have an advantage in more financially vulnerable sectors and suggests that well developed financial institutions could benefit especially small firms. This conclusion is at odds with the findings by Minetti and Zhu (2011), who, for a sample of Italian firms, do not find any sensitive difference in the effect of credit rationing on export participation according to firm size. Damijan et al. (2015), for Slovenian manufacturing firms, instead, show that the most beneficial effect of credit access is recorded for small firms.

The importance of credit for SMEs’ exports is confirmed by Gashi et al. (2014) for a sample of transition economies, even if other factors—human capital and technological knowledge—turn to be the main export determinants. Bartoli et al. (2014) for a sample of small Italian firms find that bank support is positively and significantly associated to an improvement in both intensive and extensive margins of exports of small firms. Moreover, they find that this nexus is sensitively more important for foreign banks and for Italian banks with foreign affiliates. In line with the social role of money discussed above, the authors explicitly test the hypothesis that beyond the provision of financial services, banks also transfer knowledge and information. Advisory services, as identified by counter-parties signalling and training services for commercial and administrative staff, turn to be relevant in easing export entry. This finding corroborates evidence by Beretta et al. (2005) on the positive association between banks’ internationalisation—measured by the number of branches that banks located in the province have abroad—and firms’ export status across Italian provinces. Pursuing a similar line of research, Tomohiko et al. (2014) investigate how the knowledge on foreign markets collected by Japanese banks, thanks to both their contacts with other exporting firms and their activities abroad, affects their customers’ export decision. They disclose a positive impact on different firm export margins, export entry, the number of destinations and export survival. Finally, Paravisini et al. (2015) match loan and shipment data for all exporters in Peru and find that firms willing to export to a specific market are more likely to borrow from banks that specialise in that country. More importantly, they show that shocks to the credit supply of banks have a larger effect on exports to the bank’s markets of specialization. Summing up, empirical evidence not only confirms the importance of credit access for SEs’ exports, but also corroborates the relevance of the role of monetary networks in shaping trade relationships across the geographical space.

Within this framework, we contribute to the limited stream of related literature by estimating an empirical model for the impact of financial development on the export entry probability of SEs in the context of the Turkish economy. We explore and assess the credit and social role of money and, for the first time to our knowledge, the importance of foreign banking diffusion across local banking markets.

3 Institutional background: the Turkish banking system

The banking sector is at the centre of the Turkish financial system. Turkish banks operate through a national branch banking system and there are no regional or local banks. Private banks’ headquarters are typically located in Istanbul, while government banks’ headquarters are located in Ankara (Onder and Ozyildirim 2011).

The sector has experienced important changes in the last decades especially after the 2001 financial crisis which represented an opportunity to undertake a deep modernisation and restructuring process aimed at increasing competition and efficiency and filling the regulatory deficiencies of the system. The crisis meant a structural break for the Turkish banking sector which eventually moved towards greater stability, profitability, and towards stricter and sound regulations. In particular, there was a relevant downsizing of the government-owned banks and the number of bank branches declined by 15 % between 2000 and 2006 (Onder and Ozyildirim 2011). The Banking Law 5411 issued in 2005 and its subsequent amendments introduced further relevant changes to the banking system, creating a favourable environment for the establishment of new branches by domestic and foreign firms. The latter, which are increasingly present in Turkey, still represent a small portion of the Turkish banking sector.

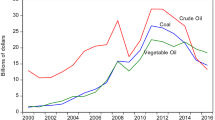

The territorial distribution of bank branches is depicted in panel (a) of Fig. 1 for year 2005 and reflects the uneven economic development of Turkish regions. Panel (b), instead, shows that the presence of branches slightly increased in more peripheral Eastern regions only during the period of our analysis. This persistent localised structure together with the centralised nature of the Turkish banking institutional and organisational structure, engender worries about the ability of regional banking conditions to meet the needs of local firms. Low expectations about regional economic prospects could, indeed, distract funds from local branches on behalf of headquarters which are located in the central regions (Dow and Rodriguez-Fuentes 1997; Martin 1999). Furthermore, in a national bank branching system, information services, which are crucial in supporting local firms’ export activities, could be centralised. Hence, the traditional Turkish territorial divide could be exacerbated and the ability to access credit and information in order to cross the borders and start exporting could be hampered for SEs located in peripheral areas. This further motivates our empirical analysis on the nexus between the diffusion of bank branches and export entry of SEs in Turkey.

Bank branches diffusion, 2005/2009. a Number of bank branches in 2005. b Bank branches growth (%)—2005/2009. Quintiles of the distributions of bank branches and total branches growth are represented by means of different grey tonalities, with the darker ones identifying upper quintiles. The top panel displays the NUTS3 spatial distribution of Turkish bank branches in 2005. The lower panel displays the NUTS3 spatial distribution of the 2005–2009 average growth of the total number of branches. Source: TurkStat SBS and AIPS. Own calculations

4 Empirical strategy

4.1 Empirical model

In our empirical analysis, we explore the impact of the development of the banking sector on the first time export market entry of SEs for a sample of Turkish manufacturing firms with less than 50 employees (European Commission 2003).Footnote 5

We estimate the following linear probability model (LPM):

\(entry^{exp}_{ijrt}\) is a dummy variable equal to one if firm i, located in NUTS3 region r and operating in 2digit NACE sector j, is an export starter and equal to zero otherwise. More specifically, we identify export starters as those firms which export own produced goods at time t, and did not export in the previous two years (i.e. \(t-1\) and \(t-2\)). The latter will be then compared to firms never exporting in the \(t-t\)-2 time span. We, therefore, exclude from our analysis both firms continuously exporting and firms which switch export status in the three-year time span.

Our main right hand side variable is \(Fdep_{j}*Branch^{pc}_{rt-1}\). To single out the role of the banking system for SEs’ export decision, we exploit and combine the regional variation in the banking development, \(Branch^{pc}_{rt-1}\), with the variation of financial dependence across manufacturing sectors, \(Fdep_{j}\). From the Banks Association of Turkey, we use information on the total number of bank branches for each of the 81 NUTS3 Turkish regions.Footnote 6 We measure financial dependence, \(Fdep_{j}\), at 2digit NACE sector level from the 2002 Turkish input–output tables as the share of purchases from the financial intermediation sector in the total sector output.Footnote 7 Table 4 shows this time-invariant measure which is constant across firms belonging to the same 2digit NACE level sector of activity.

In model 1 we control for a vector of firm level characteristics in \(t-1\), \(X_{it-1}\), which can affect a firm’s propensity to export: size in terms of number of employees, Size, labour productivity, \(Labour\ Productivity\), import status, \(Import\ Status\), average wage, Wage and the foreign ownership status of the firm, \(Foreign\ owned\). Variables labels and definitions are reported in Table 5 in “Appendix”, while corresponding summary statistics for all the variables included in the baseline analysis are presented in Table 6 in “Appendix”. Finally, we include region-year, \(\lambda _{rt}\), and sector-year, \(\eta _{jt}\), fixed effects to capture any time-varying shocks at either sector or region level which could affect the SEs’ probability of entering foreign markets. Region-year fixed effects are meant to control for differences in trade propensity across Turkish regions which originate from differences in infrastructure, geography, local economic system and cultural heritage. They also account for the direct effect of the banking system at the local level on firms’ trade, thus controlling for a different propensity to trade of firms in the region induced by finance. Sector-year fixed effects, instead, are expected to capture the evolution of comparative advantages, and any possible sector specific time-varying shock, in particular the different export propensity of firms operating in different sectors driven by their dependence on finance. Hence, the coefficient of our interest, \(\beta\), captures the relative effect of the development of the banking system at the local level on the export propensity of small firms operating in more financially dependent sectors with respect to less financially dependent ones. A similar strategy has been adopted by Rajan and Zingales (1998) in order to detect the impact of the financial sector development on industrial growth and by Manova (2013) in the analysis of the effect of financial systems on countries’ patterns of comparative advantage.

As previously mentioned, we estimate a LPM. Despite its pitfalls, estimating the LPM does not need any distributional assumption to model unobserved heterogeneity—in particular region and sector time-variant and invariant characteristics that may drive a firm’s export choice—and, in general, delivers good estimates of the partial effects on the response probability near the centre of the distribution of the regressor (Wooldridge 2002).

Finally, standard errors are clustered at the variation level of our variable of interest, that is the region-sector level, in order to correct for the within-group correlation (Moulton 1990). This also allows to account for the fact that the LPM is affected by heteroskedasticity.

4.2 Firm level data sources and sample

Our sample stems from the merging of three different databases for Turkish manufacturing in the 2005–2009 period: the Turkish Structural Business Statistics (SBS) including a large number of firm level characteristics, such as labour productivity, wage, foreign ownership, the NUTS3 region of location and size (i.e. the number of employees) for all firms with more than 20 persons employed and a rotating sample of smaller firms; the Turkish Foreign Trade Statistics (FTS) including exports and imports for the universe of Turkish importers and exporters; the Annual Industrial Product Statistics (AIPS) including production flows at the product level for all firms with more than 20 employees.

The Literature has highlighted that manufacturing firms often act as intermediaries in trade, by trading some goods produced by other indirect exporters (Ahn et al. 2011; Bernard et al. 2012, 2015). By merging FTS and AIPS, we are able to identify a firm’s exports of own produced goods. We discard export flows which are not directly related to a firm’s production activity and, as a consequence, are not associated to the burdensome export entry costs typically required by the sale of own production abroad.Footnote 8

The data availability and our definition of export starters, allow us to exploit a sample composed of 14,622 observations on three different waves—2007, 2008 and 2009—including export entrants and never exporters. Table 7 in “Appendix” shows that SEs’ export propensity is especially high in comparative advantage sectors (e.g. Wearing apparel and Machinery) nonetheless it is also remarkable in manufacturing of chemicals and of medical and precision instruments. Although export entry by region reveals that exports are biased towards Western Regions—e.g. Istanbul, Bursa and Adana—a sensitive increase in the firms’ average export entry probability has occurred in the Eastern regions of Gaziantep and Sanliurfa over the period under scrutiny.

5 Results

5.1 Baseline

According to the above conceptual framework and extant empirical evidence, the banking sector plays a prominent role in allowing SEs to overcome burdensome export entry sunk costs. The two main mechanisms envisaged by the literature are credit and information provision. In the following we will shed light on these mechanisms.

We first test the overall importance of banking development for the export entry of SEs in Columns [1]–[3] of Table 1. Estimates support the positive role of the banking system at the local level in favouring export entry of small firms that operate in more financial dependent sectors.Footnote 9 This effect is highly significant and is robust to the inclusion of firm level characteristics and to a number of checks that we present in Table 9 in the “Appendix”. Namely, our baseline result is corroborated when: (1) we estimate a probit model rather than a LPM; (2) we include further firm level controls; (3) we include province-sector-year varying variables.Footnote 10

We then corroborate our baseline hypothesis on the importance of financial development in spurring SEs’ export entry. The estimated effect from the wider specification of Column [3] is also economically meaningful. It predicts that firms operating in the Antalya region should be more likely to enter foreign markets by 6.44 percentage points than the ones located in Kahramanmaras if they were to operate in manufacture of rubber and plastic products as compared to manufacture of furniture. Being the first time export probability roughly equal to 7 % in our sample, a differential of 6.44 percentage point represents a doubling of firms’ export probability observed in our sample.Footnote 11

As far as other firm level characteristics are concerned, we largely corroborate the existing empirical findings concerning more productive and larger firms being more likely to enter foreign markets (Melitz 2003; Bernard and Jensen 2004) and on importers having a higher export propensity (Muûls and Pisu 2009; Lo Turco and Maggioni 2013; Aristei et al. 2013). We, instead, do not find any significant effect associated to a firm’s foreign ownership status. Finally, firms paying higher wages are less likely to start exporting, possibly due to their cost disadvantage.

In Table 10 in “Appendix” we consider further outcome variables for our sample of export starters. We find no effect of the banking sector at the local level on the number of export products and destinations as well as on the initial export share and value. Also, when we study the export status of SEs, financial development turns to be insignificant in affecting firms’ export propensity, beyond first time export entry. This points at the relevance of finance for overcoming burdensome entry costs in accessing new markets rather than reducing initial demand uncertainty (Rauch and Watson 2003; Iacovone and Javorcik 2010).

An IV approach

In our empirical exercise endogenous sorting could be at work. Banks could choose their location according to local firms’ export propensity, because of the existence of favourable conditions for internationalisation processes or because they anticipate positive shocks in the region-sector favouring local firms’ export performance. If this is the case, an upward bias should affect our OLS baseline estimates. Nonetheless, banks, especially the foreign ones, could prefer those locations where export ties are weak in order to reap a large number of new customers willing to enter the export market for the first time. If this is the case, our OLS estimates could be downward biased. In order to solve these potential endogeneity concerns, we implement an instrumental variable strategy. We alternatively consider two indicators based on the territorial diffusion of the banking sector in the Ottoman Empire aimed at capturing the roots of supply driven determinants of the development of the Turkish banking sector. More specifically, we consider the opening of branches by the Ottoman Imperial Bank (\(Banque\,Impriale\,Ottomane,\, BIO\)), the state bank of the Ottoman Empire, between 1863 and 1914 (Clay 1994). The BIO was the first Ottoman bank founded in 1863 by a group of British and French financiers and acted as a state bank providing services related to the collection, transmission and disbursement of revenues to the Ottoman Empire. Despite sustained growth in several provinces of the empire and the high demand for a modern banking system, the BIO considered to open new branches outside the capital city, Istanbul, only under request of the government and under the payment of the subsidy. At the onset of World War I, the BIO had a relevant number of branches outside the capital whose openings were mainly driven by the political aims of the government. BIO bank branches across Turkish provinces can be considered the first form of modern banking in Turkey. Therefore, for each Turkish province, we alternatively use the log number of BIO bank branches, BIO branches \(^{1861-1914\ pc}\), and the timing of opening, BIO branch opening \(^{1861-1914\ pc}\), measured as the log of the difference between the year of BIO branch opening in the province and the first year of opening of a branch in Turkey (1863 in Istanbul) while attributing the maximum number of years (1914–1863) plus one to provinces where a BIO branch was not opened. The lack of a relationship between the BIO branch openings and the economic development or trade involvement of the province makes us confident about their exogeneity. This is proved in Table 11 in the “Appendix”, where we show results for the regression of the log number of BIO branches and their opening sequence on per capita income in 1894 retrieved from Karpat (1978).Footnote 12 Across provinces the log of per capita income does not significantly explain our instruments. Also their territorial distribution rests on an institutional and economic setting which is radically different from nowadays. Therefore, we are convinced about the validity of our instruments.

In order to test whether results in Column [3] reflect a causal impact we show results from IV estimates in Columns [4] and [5]. The F-test and the partial \(R^{2}\) at the bottom of the table prove the goodness of our first stage regressions and reveal the strength of our instruments. We first exploit the instrument based on the geographical distribution of the number of BIO branches (Column [4]) and then their timing of opening (Column [5]). IV coefficients are substantially in line with the OLS ones and just a small downward bias characterises our baseline estimates. This could reflect that banking sorting favours locations traditionally less export oriented. Also, the downward bias could be related to measurement errors.

5.2 Assessing within-sector heterogeneity in market access and credit dependence

In order to shed light on the mechanisms behind the nexus between financial development and export entry of SEs, we test the existence of heterogeneous effects according to the level of sunk costs in a firm’s sector. In Column [6] we test the interaction between our variable of interest and an indicator of the exporters’ churning in foreign markets at 4digit NACE sector level, \(Churn^{Exp}_{4d}\), computed as the ratio between the sum of exiting and entering exporters over the total population of exporters (see Table 5 for details and data sources). We expect a higher churning to reveal the existence of lower entry barriers, hence higher competition in the export market for the sector’s products (Freund and Pierola 2010). We find that well developed banking systems at the local level favour disproportionately more the internationalisation process of SEs operating in more financially dependent sectors, and this beneficial effect is larger when export entry barriers and, hence, sunk costs are higher. This evidence suggests that financial development acts by reducing the incidence of sunk costs on small firms willing to go abroad.

We now try to go more in depth and explore the role of credit provision as a relevant driver of the overall effect of the banking development at the local level. We do so by testing the hypothesis that, a sector financial vulnerability being equal, credit conditions are more stringent for those particular activities which are characterised by higher investments in capital goods. In Column [7] we test the interaction between our variable of interest and a capital intensity—ratio of capital assets over employees—indicator at 4digit NACE sector level, \(Kint_{4d}\), that we retrieve from Italian firm level data (see Table 5 for the calculation details and data sources).Footnote 13 Our hypothesis is corroborated, as we find that the beneficial effect of a well developed banking system at the local level in financial dependent sectors is larger when the industrial activity requires larger investments in capital stock. The credit channel, which is magnified by the need of tangibles’ investments, is then at work.

5.3 Assessing the information channel through the role of internationalised banks

Once tested the overall relevance of regional finance for the reduction in export entry sunk costs of SEs and shown the importance of the credit channel, we proceed by exploring the banking sector composition in terms of presence of internationalised banks for the diffusion of knowledge on foreign markets to local small firms. In other words, we test whether, in addition to provide credit and alleviate the financial needs of SEs as revealed by the previous evidence, the banking system at the local level plays a role by providing valuable information. We also investigate whether the nature of this information matters for SEs’ entry in foreign markets.

In Column [1] of Table 2 we explore the role of internationalised banks. The latter are defined as either domestic or foreign banks founded in Turkey which have branches and/or representative offices abroad (Beretta et al. 2005). Hence, we add to our baseline specification the log of the weighted average number of branches abroad, with each bank’s weight equal to its share in the total provincial branches. We fail to find a significant impact from the existence of internationalised banks branches. We proceed by investigating whether this lack of significance could be interpreted in terms of the low relevance of general information on export markets in favour of the higher importance of destination market-specific knowledge. To dig further into the information channel, we proceed by inspecting whether the actual geographical extension of the bank network abroad is relevant in transferring destination-specific knowledge. To this purpose, we move to a firm–country specification of our model—whose baseline results, shown in Column [2], confirm the positive role of financial development—and test for the number of branches by country in Column [3] and for the share of provincial domestic branches belonging to banks with international offices/branches in the country in Column [4].Footnote 14 The sample of firms is the same as in the analysis of Table 1, and the dependent variable is the firm i’s probability of entering country c.Footnote 15 In both cases, we corroborate the view that the geography of the banking system shapes the geography of SEs’ exports. This suggests that, beyond the credit provision, the monetary network importantly shapes the socio-economic ones by transferring destination-specific information.

5.4 Assessing the role of Foreign banks in SEs’ internationalisation

A final empirical exercise concerns the analysis, for the first time to our knowledge, of the role played by foreign banks for SEs’ export entry. In order to test the importance of the banking sector composition, we add an interaction between our financial dependence indicator and the share of foreign branches on the total number of branches at the NUTS3 region level, \(Fdep_{j}*Branch^{ForSh}\), in \(t-1\) to the baseline specification. Table 3 displays the corresponding results. From Column [1], we find that the presence of foreign banks is not significantly related to firms’ export entry. Foreign banks branches do not sensitively differ from the domestically owned ones in supporting SEs willing to serve foreign markets. Nonetheless, we extend our research and look for the possible existence of an important underlying linkage between the spreading of foreign presence in local banking markets and their overall development. Beyond the role of information providers that foreign banks share with domestic internationalised firms, the entry of foreign firms in a country’s banking system could spur its development by promoting competition and efficiency. The latter, in turn, would favour firms’ export entry. Hence, we inspect whether results in Column [1] hide the existence of a significant indirect effect. We follow the principles of the mediation analysis (Sobel 1982, 1986) which helps shed light on the underlying—indirect—determinants of the observed direct relationship among economic phenomena (Heckman et al. 2013; Heckman and Pinto 2015). To this purpose, we estimate a system with two equations where, together with the model in Column [1], we estimate an equation for the impact of foreign presence on the local financial depth (columns [2]–[3]). We find that foreign branches positively and significantly affect our proxy of local financial development (Column [2]). Therefore, in spite of the lack of a direct effect, foreign banks indirectly promote firms’ penetration of foreign markets in a significant way as witnessed by the estimate of the mediated effect, \(\beta _{Mediated}^{Fdep_{j}*Branch^{ForSh}_{rt-1}}=\beta ^{Fdep_{j}*Branch^{ForSh}_{rt-1}}*\beta ^{Fdep_{j}*Branch^{pc}_{rt-1}}\) in the lower part of Column [3]. However, foreign banking seems to explain only about 5 % of the total effect of the development of the whole sector.Footnote 16

Similar results are gathered when we use the second lag of the share of foreign banks to further attenuate reverse causality issues in columns [4]–[5] of the table.

6 Conclusion

In this paper we have investigated whether the banking system promotes the export entry of SEs in the Turkish manufacturing sector. We have found that the banking development at the local level favours disproportionately more the internationalisation process of SEs which operate in more financially dependent sectors. We have shown that local financial depth matters for reducing export entry sunk costs, while it does not help firms reduce initial demand uncertainty.

Extant literature on regional finance, though, has emphasized that, beyond credit creation, the banking sector at the local level has the fundamental role of conveying information among all the social actors involved in its global network. Hence, we have provided evidence both on the importance of access to credit to overcome burdensome export entry sunk costs and on the relevance of the banking sector’s internationalisation. More specifically, we have inspected the role of internationalised banks and we have exploited variation across destination markets in order to test the nature of the knowledge flows conveyed by the banking system. We found that SEs benefit from the banks’ destination-specific knowledge rather than from general information on exporting. Finally, we have shown original evidence on the indirect impact—through the banking development at the local level—of the entry of foreign bank branches on SEs’ export entry.

The interplay between the global and local geographies of money which has characterised the recent evolution of the domestic Turkish banking sector has depicted the geography of Turkish SEs’ export expansion. Although the ongoing globalisation process and rapid technological advances cast doubts on the actual relevance of regional financial systems in spurring local development, our study points at the importance of global-local ties within the financial network in determining the activity of firms in a country’s regions. Our insights then corroborate the view on the importance of the banking sector for the real economy and, more specifically, on the geography of money increasingly driving the geography of contemporary socio-economic systems.

Notes

In 2012 small firms—firms with less than 50 persons employed—active in Turkish manufacturing accounted for about 22 % of turnover and about 44.7 % of persons employed. From Eurostat, the corresponding shares in the same year for the EU28 are 16 and 34 %, respectively. Considering the manufacturing sectors of two EU members at a comparable development stage, small firms represent 11 % of turnover and 30 % of persons employed for Hungary and 15 % of turnover and 27 % of persons employed for Romania.

Despite the importance of money for regional economic performance, its role has been highly debated. According to the neoclassical view, financial institutions would be optimally located across space and capital movements through the system would attenuate the tendencies towards an uneven economic development. Instead, real-world financial systems are characterised by asymmetric and imperfect information and low capital mobility which reproduce, and may even reinforce, uneven regional development (Martin and Minns 1995; Dow and Rodriguez-Fuentes 1997). Also, if regional financial markets are spatially segmented on the basis of differences in liquidity preferences, expectations about the regional economy can determine the flow of credit to a region, which, in turn, can affect regional development (Dow 1987, 1992). This view reverses the neoclassical supply-side driven perspective and implies the tendency for regions attracting low degrees of confidence to experience liquidity shortage, which will be greater the more integrated the national banking system. Hence, credit still remains a relevant variable for regional analysis. Depending on the development stage of the banking sector (Chick 1992), local financial conditions strictly determine regional development prospects, either because regional credit expansion closely follows the availability of deposits in banking sectors at an early stage of development or because, in more developed banking systems, credit availability crucially depends on expectations about future local economic prospects (Chick 1992; Dow and Rodriguez-Fuentes 1997; Dow 1999).

The Varieties of Capitalism approach has been proposed by Hall and Soskice (2001). The firm is at the centre of the approach, as the main actor of capitalist economies, and plays a key role in adjustment to globalisation and technical change. As a relational subject, the firm may encounter coordination problems in five spheres especially: industrial relations, vocational training, corporate governance (access to finance), inter-firm relations (clients and suppliers) and relations with employees. National political economies can be compared on the basis of how firms resolve the coordination problems in these spheres. In Liberal Market Economies (LME), firms coordinate their activities primarily via hierarchies and competitive market arrangements, while in Coordinated Market Economies (CME) firms depend more heavily on non-market relationships to coordinate their endeavours with other actors and to construct their core competencies. Consequently, CME then involve more extensive relational contracting and network as well as more reliance on collaborative rather than competitive relationships.

Several studies have in general confirmed that credit constraints represent a significant element which drives firms to self-select in export markets (see Wagner 2014 for a thorough review of recent papers). While most evidence refers to economies with a rather advanced banking sector, a few papers have also concerned middle and low income economies (Du and Girma 2007; Berman and Hericourt 2010; Fauceglia 2015). For Turkey, Akarim (2013) focuses on a sample of large firms traded at the Istanbul Stock Exchange and finds that liquidity and leverage ratios are not significantly related to firms’ export propensity.

In one of the robustness checks, we also change this threshold, by focusing on all the firms below the median size—around 40 employees—in the starting sample. Indeed, firm size is a key determinant of export entry in our data, as the export entry probability is equal to 7 % for small firms and 9.4 % for the larger ones and the difference is statistically significant.

Previous studies have already focused on aggregate measures of credit supply, exploiting variation across countries’ financial markets or regional credit markets. In particular, Manova (2013) and Fan et al. (2015) measure credit access with indicators reflecting the banking activity at the country and region level, respectively. Measures of credit supply at the local level have also been used by a number of papers to instrument the firm level proxy for credit constraints (Guiso et al. 2003; Herrera and Minetti 2007; Minetti and Zhu 2011).

The financial sector is sector 65 from the NACE rev1.1. classification.

Running the analysis on mixed exporters corroborates this statement as we find a weakly significant impact of financial development on the export entry of SEs. Results are available upon request.

In the “Appendix” (Table 8) we show results from the estimation of the baseline model 1, respectively, for the full sample and for the group of medium and large firms with 50 or more employees. Here, while the full sample bears a positive and significant coefficient for our main right and side variable, no significant impact of banking diffusion on firms’ export probability is found for the sample of large firms. Hence, we conclude that the full sample results are driven by small firms and that an important divide between small and large firms concerns the bank-export nexus.

We ran further controls which are not shown for brevity and are available upon request: (1) we consider as small all those firms whose size is below the median size—40 employees—recorded in the SBS sample of firms for which our variables of interest are defined; (2) we use (a) a time-varying financial dependence indicator retrieved from the WIOD tables (Timmer et al. 2015) for 2006 at the NACE section level, (b) the time-invariant sector level indicator by Rajan and Zingales (1998), updated by Krozner et al. (2007: 3) we denote as entrants those firms which export in t and did not export in \(t-1\), regardless of their behaviour in \(t-2\); (4) we alternatively measure banking development at the local level as the log of the total amount of loans per capita in the NUTS3 region or as the Herfindahl–Hirschman index calculated on the number of branches in the province. In all cases our baseline evidence is corroborated.

In this example, we compute the differential first time export probability of firms located in provinces at the 10th and 90th percentile of the number of branches per capita (Kahramanmaras and Antalya, respectively) and operating in sectors at the 10th and 90th percentile of financial dependence (manufacture of furniture and manufacture of rubber and plastic products, respectively).

Unfortunately, we were not able to retrieve information on provincial exports, but we are confident that their geographical distribution mimics the one of per capita income.

Unfortunately, Turkish data sources do not contain any information on stocks of tangible assets. So we decided to exploit information from Italian firms to build a proxy of sectoral capital intensity, under the hypothesis that the technology content of sectors and their ranking in terms of capital intensity do not sensitively differ between the two countries.

A possible extension would be to single out the importance of foreign banks branches in promoting access to their country of origin. This analysis is, however, prevented due to the small variation in nationalities of foreign banks.

In this analysis, we lose some observations due to missing information on destination country level variables.

We take as reference coefficient estimates of columns [2]–[3] and, as before, we compute the differential first time export probability of firms located in Kahramanmaras and Antalya provinces in the manufacture of furniture and manufacture of rubber and plastic products, respectively.

References

Ahn, J., Khandelwal, A. K., & Wei, S. J. (2011). The role of intermediaries in facilitating trade. Journal of International Economics, 84, 73–85.

Akarim, Y. D. (2013). The impact of financial factors on export decisions: The evidence from Turkey. Economic Modelling, 35, 305–308.

Aristei, D., Castellani, D., & Franco, C. (2013). Firms’ exporting and importing activities: Is there a two-way relationship? Review of World Economics (Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv), 149, 55–84.

Armenter, R., & Koren, M. (2015). Economies of scale and the size of exporters. Journal of the European Economic Association, 13(3), 482–511.

Axelsson, B., & Johanson, J. (1992). Foreign market entry. The textbook vs. the network view. London: Routledge.

Bartoli, F., Ferri, G., Murro, P., & Rotondi, Z. (2014). Bank support and export: Evidence from small Italian firms. Small Business Economics, 42, 245–264.

Beretta, E., Prete, D., & Federico, S. (2005). Bank internationalization and export propensity: An analysis on Italian provinces. Bank of Italy.

Berman, N., & Hericourt, J. (2010). Financial factors and the margins of trade: Evidence from cross-country firm-level data. Journal of Development Economics, 93, 206–217.

Bernard, A., Grazzi, M., & Tomasi, C. (2015). Intermediaries in international trade: products and destinations. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 97(4), 916–920.

Bernard, A., & Jensen, J. (2004). Why some firms export. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 86(2), 561–569.

Bernard, A. B., Blanchard, E. J., Beveren, I. V., & Vandenbussche, H. Y. (2012). Carry-along trade. NBER Working Papers 18246. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Bernard, A. B., Eaton, J., Jensen, J. B., & Kortum, S. (2003). Plants and productivity in international trade. American Economic Review, 93, 1268–1290.

Chick, V. (1992). The evolution of the banking system and the theory of saving, investment and interest. New York: Macmillan.

Clay, C. (1994). The origins of modern banking in the levant: The branch network of the imperial ottoman bank, 1890–1914. International Journal of Middle East Studies, 26, 589–614.

Damijan, J., Kostevc, C., & Polanec, S. (2015). Access to finance, exporting and a non-monotonic firm expansion. Empirica, 42, 131–155.

Das, S., Roberts, M., & Tybout, J. (2007). Market entry costs, producer heterogeneity, and export dynamics. Econometrica, 75, 837–873.

Dow, S. C. (1987). The treatment of money in regional economics. Journal of Regional Science, 27, 13–24.

Dow, S. C. (1992). The regional financial sector: A scottish case study. Regional Studies, 26, 619–631.

Dow, S. C. (1999). The stages of banking development and the spatial evolution of financial systems. New York: Wiley.

Dow, S. C., & Rodriguez-Fuentes, C. J. (1997). Regional finance: A survey. Regional Studies, 31, 903–920.

Du, J., & Girma, S. (2007). Finance and firm export in China. Kyklos, 60, 37–54.

European Commission, E., (2003). Commission recommendation 2003/361/EC of 6 May 2003 concerning the definition of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises. Official Journal of the European Union May (pp. 36–41).

Fan, H., Lai, E. L. C., & Li, Y. A. (2015). Credit constraints, quality, and export prices: Theory and evidence from China. Journal of Comparative Economics, 43, 390–416.

Fauceglia, D. (2015). Credit constraints, firm exports and financial development: Evidence from developing countries. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 55, 53–66.

Fernandes, A., Freund, C., & Pierola, M. (2016). Exporter behavior, country size and stage of development: Evidence from the exporter dynamics database. Journal of Development Economics, 119, 121–137.

Fisman, R., & Love, I. (2003). Trade credit, financial intermediary development, and industry growth. Journal of Finance, 58, 353–374.

Freund, C., & Pierola, M. D. (2010). Export entrepreneurs: Evidence from Peru. Policy Research Working Paper Series 5407. The World Bank.

Gashi, P., Hashi, I., & Pugh, G. (2014). Export behaviour of SMEs in transition countries. Small Business Economics, 42, 407–435.

Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2003). People’s opium? Religion and economic attitudes. Journal of Monetary Economics, 50, 225–282.

Hall, P., & Soskice, D. (2001). An Introduction to varieties of capitalism (pp. 1–68). Oxford: OUP.

Heckman, J., Pinto, R., & Savelyev, P. (2013). Understanding the mechanisms through which an influential early childhood program boosted adult outcomes. American Economic Review, 103, 2052–86.

Heckman, J. J., & Pinto, R. (2015). Econometric mediation analyses: Identifying the sources of treatment effects from experimentally estimated production technologies with unmeasured and mismeasured inputs. Econometric Reviews, 34, 6–31.

Heinemann, T. (2014). Relational geographies of emerging market finance: The rise of turkey and the global financial crisis 2007. European Urban and Regional Studies.

Herrera, A. M., & Minetti, R. (2007). Informed finance and technological change: Evidence from credit relationships. Journal of Financial Economics, 83, 223–269.

Iacovone, L., & Javorcik, B. S. (2010). Multi-product exporters: Product churning, uncertainty and export discoveries. The Economic Journal, 120, 481–499.

Impullitti, G., Irarrazabal, A. A., & Opromolla, L. D. (2013). A theory of entry into and exit from export markets. Journal of International Economics, 90, 75–90.

Johanson, J., & Mattsson, L. (1988). Internationalisation in industrial systems: A network approach. London: Croom Helm.

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J.-E. (1977). The internationalisation process of the firm. A model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitment. Journal of International Business Studies, 8(1), 23–32.

Karpat, H. (1978). Ottoman population records and th census of 1881/82 and 1893. International Journal of Middle East Studies, 9, 237–274.

Krozner, R., Laeven, L., & Klingebiel, D. (2007). Banking crises, financial dependence, and growth. Journal of Financial Economics, 84, 187–228.

Lawless, M. (2009). Firm export dynamics and the geography of trade. Journal of International Economics, 77, 245–254.

Lee, R. (1999). Local money: Geographies of autonomy and resistance?. New York: Wiley.

Lo Turco, A., & Maggioni, D. (2013). On the role of imports in enhancing manufacturing exports. The World Economy, 36, 93–120.

Manova, K. (2013). Credit constraints, heterogeneous firms, and international trade. Review of Economic Studies, 80, 711–744.

Manova, K., Wei, S. J., & Zhang, Z. (2015). Firm exports and multinational activity under credit constraints. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 97(3), 574–588.

Martin, R. (1999). The new economic geography of money. New York: Wiley.

Martin, R., & Minns, R. (1995). The spatial structure and implications of the UK pension fund system. Regional Studies, 29, 125–144.

Melitz, M. J. (2003). The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica, 71, 1695–1725.

Minetti, R., & Zhu, S. C. (2011). Credit constraints and firm export: Microeconomic evidence from Italy. Journal of International Economics, 83, 109–125.

Moulton, B. R. (1990). An illustration of a pitfall in estimating the effects of aggregate variables on micro unit. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 72, 334–38.

Muûls, M., & Pisu, M. (2009). Imports and exports at the level of the firm: Evidence from belgium. The World Economy, 32, 692–734.

Onder, Z., & Ozyildirim, S. (2011). Political connection, bank credits and growth: Evidence from turkey. The World Economy, 34, 1042–1065.

Paravisini, D., Rappoport, V., & Schnabl, P. (2015). Specialization in bank lending: Evidence from exporting firms. Working Paper 21800. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Pollard, J. (2003). Small firm finance and economic geography. Journal of Economic Geography, 3, 429–452.

Rajan, R. G., & Zingales, L. (1998). Financial dependence and growth. American Economic Review, 88, 559–86.

Rauch, J. E., & Watson, J. (2003). Starting small in an unfamiliar environment. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 21, 1021–1042.

Roberts, M. J., & Tybout, J. R. (1997). The decision to export in colombia: An empirical model of entry with sunk costs. American Economic Review, 87, 545–564.

Sobel, M. (1982). Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology, 13, 290–312.

Sobel, M. (1986). Some new results on indirect effects and their standard errors in covariance structure models. Sociological Methodology, 16, 159–186.

Timmer, M. P., Dietzenbacher, E., Los, B., Stehrer, R., & de Vries, G. J. (2015). An illustrated user guide to the world input-output database: The case of global automotive production. Review of International Economics, 23(3), 575–605.

Tomohiko, I., Keiko, I., & Daisuke, M. (2014). Lender banks’ provision of overseas market information: Evidence from Japanese small and medium-sized enterprises’ export dynamics. Discussion papers 14064. Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI).

Wagner, J. (2014). Credit constraints and exports: A survey of empirical studies using firm-level data. Industrial and Corporate Change, 23, 1477–1492.

Wooldridge, J. (2002). Econometric analysis of cross-section and panel data. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Zazzaro, A. (1997). Regional banking systems, credit allocation and regional economic development. Economie Appliquée, 1, 51–74.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

See Tables 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lo Turco, A., Maggioni, D. “Glocal” ties: banking development and SEs’ export entry. Small Bus Econ 48, 999–1020 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9809-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9809-7