Abstract

We present experimental evidence on the effectiveness of corporate leniency programs. Different from other leniency experiments, ours allows subjects to have free-form communication. We do not find much of an effect of leniency programs. Leniency does not deter cartels. It only delays them. Free-form communication allows subjects to build trust and resolve conflicts. Reporting and defection rates are low, especially when compared to experiments with restricted communication. Indeed, communication is so effective that, with leniency in place, prices are not affected if cartels are fined and cease to exist.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

One of the main tasks of antitrust authorities is to fight cartels. Leniency programs can help. In such programs, an Antitrust Authority (AA henceforth) offers a fine reduction to firms that report a cartel. Since the introduction of leniency programs, the number of cartels prosecuted has increased in both the United States and European Union (Motta 2004; Spagnolo 2008). Whether this is due to the success of leniency programs or merely reflects an increase in cartel activity is unclear. Since cartels are secretive, it is hard to assess this empirically.Footnote 1 Experimental methods may shed some light.

In most leniency experiments in the literature, subjects can communicate in a restricted manner, essentially by sending signals. Yet, studies without leniency have shown that lessons drawn from cartel experiments with restricted communication may not translate to environments with free-form communication: Where natural conversation is possible. Free-form communication may be important in building trust, resolving conflicts, and coordinating collusive strategies. If free-form communication allows firms to build trust, the question becomes whether leniency programs can break that trust.

We therefore study a leniency experiment that allows for free-form communication. We let subjects play a repeated game and allow them to discuss anything via a computer chat. To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to do so.Footnote 2 However, once subjects decide to communicate, they are technically in a cartel and hence may be prosecuted. One other important innovation is that we allow subjects to report after they have learned that an AA has started an investigation. This also gives subjects the option to discuss their reporting strategy, should there be an investigation. For robustness, we consider two leniency regimes that differ in the probability that the AA starts an investigation, and in the probability that it finds evidence of the existence of a cartel.

We do not explicitly compare free-form communication with restricted communication. Nor do we study the effect of the number of oligopolists. That would exponentially increase our number of treatments. Rather, we compare our results to those in the literature with restricted communication.

Different from experiments with restricted communication, we do not find much of an effect of leniency programs. Leniency does not deter cartels. It only delays them. Free-form communication allows subjects to build trust and resolve conflicts. Subjects achieve remarkable sophistication in the agreements they make. Reporting and defection rates are low, especially when compared to experiments with restricted communication. Indeed, communication is so effective that, with leniency in place, prices are not affected if cartels are fined and cease to exist.

Inevitably, any experiment only partly reflects real-world collusion. We cannot impose reputational consequences of being in, or reporting a cartel. We cannot have criminal penalties as in the United States or the United Kingdom. In our experiment the likelihood of investigation is exogenous, and the extent of penalties does not depend on the amount of communication. There are no additional penalties for recidivism. The AA does not learn, and penalties do not depend on how long a cartel has been active. Still, despite these shortcomings, we believe that our experiment can shed some light on real-world collusion.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: In Sect. 2 we discuss related literature. Section 3 presents our experimental design, while results are reported in Sect. 4. Section 5 concludes.

2 Related Literature

As noted in the Introduction, in a number of leniency experiments—most notably Hinloopen and Soetevent (2008) and Bigoni et al. (2012)—subjects can communicate in a restricted manner, essentially by sending signals. Yet, many studies have shown that in cartel experiments, the results are very different if there is free-form communication rather than restricted communication. In this section, we first discuss the related literature on leniency, then the literature on the effect of communication on collusion.

The experimental literature on leniency is summarized in Table 1. Apesteguia et al. (2007) study a one-shot homogeneous Bertrand triopoly and allow for free-form communication. They find that leniency decreases prices, but does not affect cartel activity. In Hinloopen and Soetevent (2008) (HS henceforth) subjects indicate an acceptable price range, until a unique price is reached or time runs out. The resulting price is the cartel price. Leniency programs are remarkably successful: No cartel survives for more than one period, and 97% of the cartels are reported. Prices are lower with leniency. In Bigoni et al. (2012) (BFLS henceforth) communication is also restricted: Subjects can indicate only their minimal acceptable price. Leniency lowers cartel incidence, but cartels that are formed survive longer. Prices are lower with leniency, compared to an AA without a leniency program.Footnote 3

Hinloopen and Onderstal (2014) study auctions. If bidders collude, one is randomly assigned as the designated winner and does side payments to the others. Leniency then increases the number of cartels and prices. In Clemens and Rau (2019), subjects do not set prices or quantities and decide only whether to form and report a cartel. Leniency then lowers cartel incidence, but increases it if the ringleader cannot apply for leniency.Footnote 4

Now consider the effect of communication, summarized in Table 2. Studies on collusion with restricted communication (but without an AA) typically find that communication has only temporary effects on cartelization. In Holt and Davis (1990) for example, sellers can send a non-binding price announcement before they commit to a price. Initially, such announcements have a large effect on prices, but the effect soon disappears. Other studies find similar results (see Table 2). Studies that allow free-form communication find collusive effects that are larger and persistent. Fonseca and Normann (2012) also find a hysteresis effect: When subjects can no longer chat, prices are significantly higher compared to a case where communication was never possible.

Summing up: In experiments with restricted communication, leniency programs typically decrease prices and reduce cartel activity. Experiments without leniency find a small and temporary effect of restricted communication on collusion. With free-form communication, there is a profound and persistent effect. Indeed, Cooper and Kühn (2014, p. 271) conclude that “[c]ommunication is fundamentally different when subjects participate in a natural conversation rather than using a limited message space.”

3 Experimental Design

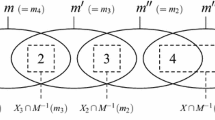

In a nutshell, our experimental design is as follows. Subjects play a repeated homogeneous Bertrand duopoly. In each period, if both subjects decide to communicate, free-form communication takes place.Footnote 5 A cartel is then established. A cartel exists whenever there has been communication that is still undetected by the AA. A cartel is detected and breaks down whenever it is reported to, or discovered by the AA. Second, subjects choose prices. Third, an antitrust investigation may be opened. Fourth, subjects can apply for leniency. If anyone does, the AA finds evidence for sure. Without an application, the AA may still find evidence. If evidence is found, fines are imposed.

We create an environment that is most susceptible to cartels: Leniency programs have the most scope to be effective if there are many cartels to start with. We therefore focus on Bertrand duopolies; this market structure is most prone to collusion in the lab (see, e.g. Haan et al. 2009). Moreover, we allow subjects to apply for leniency after an antitrust investigation has been announced. This broadens the scope for communication, as it also allows subjects to coordinate on the course of action after such an announcement. Indeed, in the real world many leniency applications occur only after an AA has announced an investigation.Footnote 6

We use fixed matchings: Every subject plays with the same competitor in all periods. We refer to each such matching as a market. Subjects play at least 20 periods. After that, there is a probability of 20% in each period that the experiment ends. This is determined by a random computer draw, independently per group. Hence, the number of periods played differs per market.

In more detail, the experiment unfolds as follows: We first discuss the leniency treatments, as these are the most involved. In stage 1, each subject decides whether to communicate by pressing a ‘YES’ or a ‘NO’ button. In stage 2, if both pressed ‘YES’, a computer chat takes place for a limited time.Footnote 7 A subject that chooses not to communicate never learns the communication decision of the other subject. Inevitably, a subject that does choose to communicate will learn the communication decision of the other subject. Subjects know this beforehand. In our experiment, communication always implies that a cartel is formed and hence that the participants can be fined, regardless of the actual content of the communication.Footnote 8 A cartel ends only if it is detected by the AA. Subjects can thus be prosecuted not only for communication in this period, but also for past communication that was not yet detected.

In stage 3, subjects choose prices from \(\{1, 2, \ldots , 10\}\). Costs are zero, and products are homogeneous. Demand is inelastic and normalized to 1. Hence, the lowest-priced subject captures the market and makes profits equal to his price. With equal prices, the market is shared equally. At the end of this stage, subjects learn both prices.

In stage 4, with probability α, the AA opens an investigation, and subjects learn this. Next, subjects choose to REPORT or NOT REPORT. Hence, reports can only be made after prices and possible investigations are observed. They can also be made when there is no investigation, and hence can be used as a punishment device; see Spagnolo (2000) and Ellis and Wilson (2001). Reporting costs 0.5.Footnote 9 Without reports, the AA discovers a cartel with probability p; with reports it does so for sure. Cartel fines are 9. For simplicity, we thus use fixed fines.Footnote 10 If a subject was the only one to report, its fine is reduced to 1 with an investigation, and to 0 without an investigation.Footnote 11 If both report, fines are shared equally. In theory, subjects could go bankrupt; but in the actual experiment that is never an issue.

For robustness, we consider two treatments that include the possibility of leniency: In treatment Profound, α = 0.20 and \(p = 0.75\).Footnote 12 In Superficial α = 0.75 and \(p = 0.20\). Thus, Profound has relatively few profound (thorough) investigations that have a high probability of uncovering the cartel; while Superficial has relatively many superficial investigations that have a much lower probability of uncovering a cartel. In Antitrust, subjects cannot report, and we set \(\alpha =0.15\) and \(p=1\). Hence, in all these treatments, the ex ante probability of cartel discovery is 15% in each period.Footnote 13 Treatment Benchmark has \(\alpha =p=0\).Footnote 14 In online Appendix AFootnote 15 we show that with grim trigger strategies (Friedman 1971), colluding on the maximum possible price is an equilibrium in each treatment. This is still true if we allow for the possibility that subjects continue the cartel tacitly after it has been discovered (but not reported).

The experiment took place at the Groningen Experimental Economics Laboratory (GrEELab) of the University of Groningen. Participants were students at the Faculty of Economics and Business. Sessions took between 45 and 75 minutes. Subjects signed up for sessions, and treatments were randomly assigned to sessions: 36 subjects participated in Benchmark; 34 in Antitrust; 36 in Profound; and 34 in Superficial.

Printed instructions were provided and read aloud. On their computer, subjects first had to answer a number of questions correctly to ensure understanding of the experiment. Participants received an initial endowment of 70 points and were paid at a rate of €0.10 per point. The initial endowment is large enough to avoid that they are ending up with negative earnings from the experiment. Average earnings were €15.44 and ranged from €8.00 to €21.80. The experiment was programmed in z-Tree (Fischbacher 2007).

4 Results

We are interested in the effect of introducing an AA (comparing Antitrust and Benchmark), and in the additional effect of introducing a leniency program (comparing leniency treatments and Antitrust). Unless stated otherwise, we use the Mann–Whitney U Test (MWU) for the relevant no-treatment effect versus the two-sided alternative. For our analysisFootnote 16, we take only the first 20 periods into account.

4.1 Cartels

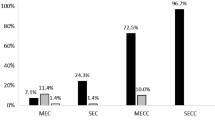

We first study cartel incidence. A cartel exists if there has been communication that is still undetected. Cartel incidence is the percentage of markets that form a cartel. If there is no cartel, we describe a market as being competitive. Only cartels can be prosecuted. Figure 1 shows how cartel incidence develops over time. Note that it is often lower in Profound and Superficial than in Antitrust—but not in the final periods. Cartel incidence seems to decrease over time in Antitrust and to a lesser extent in Profound. In Benchmark we almost converge to full cartelization.Footnote 17

Table 3 gives the overall cartel incidence for all treatments. Entries in the right-hand panel indicate whether cartel incidence in the row treatment is significantly lower (<) or higher (>) than in the column treatment, or whether the difference is not significant (\(\approx \)) at 10%. We use this convention throughout the paper. The entry Leniency gives both leniency treatments (Profound and Superficial) combined. Our unit of observation is the average cartel incidence per experimental market, which leaves us with 17-18 observations per treatment. From the table, cartel incidence in Benchmark is higher than in the other treatments, at 1% in each case. We find:

Result 1

(Cartel incidence) Introducing an AA substantially decreases cartel incidence. We find no evidence that a leniency program further decreases the number of cartels.

This result runs counter to both HS and BFLS, who find that a leniency program significantly decreases cartel incidence. A possible explanation is that subjects use free-form communication to discuss reporting strategies and build trust, hence mitigating the negative effect on cartelization that is found in studies with restricted communication. If so, then almost all subjects would discuss their reporting decision. We show later that this is indeed the case. Hence, we tentatively conclude that due to free-form communication, leniency programs have no effect on cartelization in our experiment, whereas they lead to fewer cartels in HS and BFLS.

4.2 Prices

Figure 2 shows average market prices over time.Footnote 18 Initially, Benchmark and Antitrust prices appear higher than those in the Leniency treatments, but they seem to converge in the last 5 periods. Average prices appear to increase over time, especially in the Leniency treatments. This differs remarkably from HS, who find that prices decrease over time.Footnote 19 Tentatively, our free-form communication allows subjects to build trust over time, while the restricted communication in HS does not. Indeed, results in HS are in line with the literature that finds that restricted communication only raises prices temporarily.

From Table 4, prices in Antitrust are significantly higher than in Leniency, but only at 10%. From Table 5, in the first five periods prices in Leniency are indeed lower than in Antitrust, but this difference disappears in the last five periods. Hence:

Result 2

(Market prices) Introducing an AA does not affect prices. There is weak evidence that introducing leniency decreases prices. This is driven by early periods: In later periods there is no effect. Prices with a leniency program are not significantly different from those without an AA.

HS also find no effect of an AA, but a much stronger effect of leniency. In Cooper and Kühn (2014), free-form communication helps in building trust and resolving conflicts. That may also explain why leniency has a much smaller effect here.

BFLS find that introducing an AA leads to significantly higher prices. The authors argue this is caused by an enforcement effect: Subjects are more reluctant to deviate from high cartel prices as their competitor may punish by reporting the cartel. However, contrary to BFLS, our Antitrust does not allow for reporting, so this is not an issue. BFLS also find that with leniency prices fall back to their level without an AA.

4.3 Prices: Digging Deeper

Above, we found weak evidence that the introduction of leniency reduces average prices. We now analyze what drives that difference. From Table 6, surprisingly, whereas leniency does not affect prices within a cartel, we find weak evidence that it decreases prices outside a cartel. Also, cartel and competition prices in Benchmark are lower than those with an AA.Footnote 20 BFLS also find significantly lower competition prices in Benchmark. Their cartel prices are higher with Leniency compared to both other treatments. HS find the opposite: Cartel prices with leniency are lower than in Antitrust and Benchmark.

From Fig. 3, competition prices seem to increase sharply over time in treatments with an AA.Footnote 21 Note that Fonseca and Normann (2012, 2014) find a hysteresis effect of communication: When subjects no longer chat, prices are higher compared to a case where communication never occurred. Such an effect may also be present here. Essentially, we have two types of markets with competition: Those that were a cartel in the past (and where hysteresis may be an issue); and those that were not. The fact that competition prices increase over time may be driven by this difference. With hysteresis, “post-cartel competition prices” (those in markets with a cartel in their past) would be higher than “pre-cartel competition prices” (those in markets with no cartel history).

From Table 7, there is indeed a huge difference between pre- and post-cartel competition prices in each relevant treatment. Moreover, there is no difference in pre- or post-cartel competition prices between treatments. Comparing average prices in the bottom panel of Table 7 to those in the top panel of Table 6, the difference between cartel and post-cartel competition prices is not significant for Leniency, and only significant at 10% for Antitrust.

Hence, hysteresis is indeed an important issue. After a conviction subjects start with a clean slate. Yet they often continue to set a high price without the need for further communication, and hence without forming a new cartel. Sometimes subjects even explicitly agreed to refrain from further communication but to continue to set monopoly prices after a detection. This hysteresis effect is especially strong with a leniency program in place. Over time the number of competitive markets that has been a cartel in the past will increase. Hysteresis thus explains the increase in average competition prices in Fig. 3.

From Table 5, we also have that average prices are initially lower with leniency. As leniency does not affect either cartel or post-cartel competition prices (from Tables 6 and 7), the only possible explanation is that cartels form later under a leniency program. From Table 8, that is indeed the case. Introducing an AA does not have such an effect.

In general, subjects are only willing to engage in a cartel if they feel their competitor can be trusted. With a leniency program in place, the competitor not only has to be trusted to stick to the price agreement, but also to not to report the cartel. Hence, the amount of trust required is now arguably higher. Subjects may then be more reluctant to engage in a cartel, and more inclined to wait and see whether high prices can be achieved without communication. Hence, cartels form later. This may also explain the stronger hysteresis we find with a leniency program in place. Cartels that form under leniency have a higher level of trust and hence, when detected, may also be better able to sustain high prices without the need for further communication.

The most important observations from this subsection are:

Result 3

(Cartel and competition prices) Introducing an AA increases cartel and competition prices. Adding leniency decreases competition prices, but still leaves them higher than without an AA. There is strong hysteresis: After a cartel terminates, prices remain at a higher level than before the cartel was in place. With leniency, post-cartel competition prices do not differ significantly from cartel prices, and cartels form much later.

Once an AA is in place, talk is no longer cheap—at least in the sense that it now has real consequences that may be costly. Hence, it may very well be the case that engaging in chat now has more of a commitment effect, and hence is more instrumental in building trust and increasing cartel prices. The fact that competition prices are also higher is driven by hysteresis. After a cartel breaks down, we are back to competition, but subjects often honor the agreements they made before the breakdown.

4.4 Defecting and Reporting

When studying the effect of a leniency program, it is interesting to learn its effect on defections and reporting. Table 9 gives the number of possible defections;Footnote 22 the number of actual defections; and the average defection rate over relevant groups.

The number of defections is remarkably low. This differs sharply from HS, who find defection rates of 97% under leniency. BFLS report rates that range from 37 to 56%. Apparently, subjects are less inclined to cheat after an explicit agreement, rather than when one is implied by restricted communication. Introducing a leniency program seems to increase the defection rate; but the difference with Antitrust is not significant.

Table 10 studies the reporting decision. The top panel considers all cartels; the bottom panel those with a defection; the middle panel those without. ‘Obs’ reflects the number of cartel periods (hence the number of periods with the possibility of reporting); ‘rate’ is the average incidence over all groups with reports. Reporting rates are modest. HS report rates of 80% after a defection; rates in BFLS amount to 51%. In Profound, we find more reporting than in Superficial, also with no defection. Remarkably, there are many reports without an investigation, especially in Profound. In most cases, this is not due to a defection.

Summing up: We established:

Result 4

(Defecting and reporting) Defection and reporting rates are much lower than in experiments with restricted communication. Introducing an AA decreases defection rates. The reporting rate is higher with a few profound rather than many superficial investigations.

4.5 The Inner Workings of a Cartel

Analyzing chats from our experiment provides a unique opportunity to study how subjects manage to create and maintain a cartel – at least in the lab. Table 11 provides examples of the sophistication that subjects manage to reach in their agreements.Footnote 23

The first panel gives the conversation of group 14 in Profound in period 1. These subjects have a particularly effective conversation, agreeing to full collusion, no future communication, and even formulating a penalty should anyone not adhere to the agreement. The second panel, from Superficial, has the same gist. The right-hand panel, from Profound, shows how subjects use the chat to resolve their conflict. Apparently, subject 2 defected by setting price 9 and now proposes that subject 1 can set 9 in this period to make up for the loss, and that they will both set 10 in all future periods.

Table 12 provides summary statistics for the chats. An overwhelming majority of groups established a cartel at some point, although the percentage is lower in Profound. Groups that chat do so roughly twice on average, but almost six times in Benchmark. Chats in Superficial are somewhat longer than those in other treatments.Footnote 24

We use content analysis to quantify statements made in the chats.Footnote 25 Two assistants—who were unaware of our research questions–independently classified all statements (1647 lines in 186 conversations) with the use of a classification scheme.Footnote 26 Individual lines could be assigned to multiple categories. Cohen’s (1960) kappa is used as a measure of agreement between coders.Footnote 27 In Table 13, we consolidate the 61 original categories into 12 broader ones. We report the percentage of groups with communication where the relevant issue is discussed at least once.Footnote 28 From the table, all cartels discuss prices at some point. With leniency, almost all discuss the reporting decision; 38-50% discuss future communication; and some 20% use threats – much more than in Antitrust and Benchmark. Trust issues are raised more often in Superficial than in Profound. Some groups engage in general chitchat, but not all do.

Suppose leniency makes it harder to coordinate, and hence makes conflict resolution more important, as Cooper and Kühn (2014) suggest. Subjects would then more often discuss outcomes of previous periods. This is exactly what we find. In Antitrust, only 13% of groups discuss previous periods. In the leniency treatments, this is 43% on average. This suggests that free-form communication is especially important in Leniency, and also may help explain why we do not find an effect of leniency in our experiment. The fact that almost all subjects discuss their reporting strategy further supports that view.

Coders also classified for each conversation whether an agreement was made and, if so, what kind of agreement.Footnote 29 Table 14 gives an overview. Virtually every cartel makes agreements at some point. Many do so on prices. Agreements concerning future reporting or communication are also made remarkably often. With leniency, 73% agree not to report when an investigation is announced.Footnote 30

Summing up: We have:

Result 5

(Inner workings of a cartel) Subjects reach a high level of sophistication in their communication. In almost all groups, agreements are made concerning price. In treatments with an AA, 35-43% of cartels make agreements concerning future communication. With leniency, 73% agree not to report when an investigation is announced.

4.6 Regressions

To help understand how past behavior and chats affect market outcomes, Table 15 reports regressions for the initiation of a cartel and for market prices.Footnote 31 All treatments with an AA are included. In column (1) we do a Cox regression to study the emergence of cartels. Technically we do a survival analysis, where we study the survival of competition and the ‘death’ of such a competition spell represents the formation of a cartel. For technical reasons, as our left-hand variable we take the number of periods with competition plus 1.Footnote 32 From column (1), a cartel is formed significantly later with a leniency program in place, in the sense that competition is more likely to survive.Footnote 33 In other words, cartels take longer to form in that case. This confirms the last part of Result 3. Past discoveries also have a negative effect, but that is primarily driven by the Antitrust treatment. We do not find an effect of past reports.

In column (2) in Table 15, we study market prices in each period. Using a random-effects linear regression, we explain the price in each period from the period, the treatment, whether trust issues have been raised (trust), whether threats have been made (threats),Footnote 34 whether participants engaged in chitchat (chitchat), and whether a price agreement has been reached that is (still) valid in this period (priceagree).Footnote 35

From column (2), prices are higher with a price agreement, though not significantly so in Antitrust. Also, they are higher in later periods. Intriguingly, raising the issue of trust has a negative effect on prices in Profound, but a positive effect in Superficial. It is hard to see why the effect would be so different in the two treatments. Therefore, we take this to be a statistical fluke. Threats have a negative effect on prices. It seems that general chitchat serves as a mechanism to build trust and familiarity; prices are higher if participants have engaged in such chitchat, though not significantly so in Superficial.

Arguably, we may have an endogeneity problem in (2), as the treatment may influence the extent of cartelization, and the extent of cartelization affects prices. To avoid this, column (3) includes only prices that were set in a cartel period. This regression also allows us to study the effect of past discoveries and past reports on current cartel prices. We now see that raising trust issues has a positive effect on cartel prices, although this is significant only in Superficial. With leniency, cartels that have been discovered in the past charge higher prices on average. Apparently, a past discovery focuses minds and makes collusion more successful. Past reports do not have a significant effect; neither does chitchat.

Finally, we also look at prices in the first cartel episode of a market, in column (4). This regression thus studies the effects of communication on the very first cartel, so any effect of past defections, reports, etc., are ruled out. Also, threats and discussions on trust that are a result of past cartel behavior are filtered out, which eliminates another possible source of heterogeneity. Raising trust issues now also has a significantly positive effect in Antitrust, whereas chitchat affects prices negatively in Superficial. Both trust*sup and threats*prof are still significant.

Summing up: We have:

Result 6

(Past behavior and chats) When we examine all prices we find a positive effect of general chitchat, but that effect disappears or is even reversed if we examine cartel prices. Similarly, threats leads to lower prices overall, but to higher cartel prices in Profound. Past discoveries do lead to higher cartel prices in both leniency treatments. Most importantly however, regardless of how we slice the data, we never find a significant direct effect of either leniency treatment on prices. Hence, we find no evidence whatsoever that leniency has any direct effect on prices.

5 Conclusion

This paper presents experimental evidence on the effectiveness of corporate leniency programs. We allow for free-form communication, and subjects can apply for leniency after an antitrust investigation has been announced.

We find the following: Introducing an AA substantially decreases cartel incidence, which is consistent with experiments with restricted communication. Yet, such experiments also find that leniency decreases cartel incidence. We do not find such an effect. Arguably, this is due to the free-form communication in our experiment. Almost all cartels discuss their reporting decision. This helps in building trust and mitigates the effect of a leniency program—leaving it almost toothless.

We do find weak evidence that adding leniency leads to lower prices on average. But this is driven entirely by early periods: With leniency, cartels take longer to form. Indeed, controlling for this in a regression leaves no significant effect of leniency on prices. We also find strong hysteresis, especially with leniency programs. After a cartel terminates, prices remain at a much higher level than before it was in place. With leniency, such post-cartel competition prices are not significantly different from prices during a cartel.

Also, defection and reporting rates are much lower than in experiments with restricted communication. Subjects reach a remarkable level of sophistication in their communication. Almost all groups make agreements concerning price. In treatments with an AA, 35–43% of cartels make agreements with respect to future communication. With leniency, 73% agree not to report the cartel when an investigation has started.

Summing up: Different from experiments with restricted communication, with free-form communication we do not find much of an effect of leniency programs. Leniency does not deter cartels. It only delays them. Free-form communication allows subjects to build trust and resolve conflicts. Defection rates are remarkably low—much lower than in experiments with restricted communication. Indeed, communication is so effective that, with leniency in place, prices are not affected if cartels are fined and cease to exist.

As noted, in our experiment, free-form communication allows subjects to build trust. Indeed, we find evidence that such trust is stronger (in the sense that cartels are more effective) if subjects engage in general chitchat rather than just focus on making price agreements. That trust is strong enough to withstand the effect of a leniency program.

Notes

Apesteguia et al. (2007) also allow for free-form communication in a leniency experiment. However, they look at a one-shot game. Also, Clemens and Rau (2019) look at free-form communication, but do not allow subjects to choose prices or quantities. Hence, they are not able to study how free-form communication affects the effectiveness of collusion.

Bigoni et al. (2015) extend the study and also find a beneficial effect of leniency programs. They study how a change in the fine, and the probability of obtaining that fine, affects deterrence.

Hamaguchi et al. (2009) take a similar approach and find that larger cartels break down sooner; the extent of leniency has no effect.

Communication is only allowed to be in English. We do not believe that this is a problem, as the Faculty of Economics and Business at the University of Groningen, where the experiment was conducted, has an international student body and almost all degree programs are taught in English.

Chats were capped at 90 seconds when a cartel was first formed; at 45 seconds with a cartel in place, and at 60 seconds when a cartel is re-established. A countdown timer always appeared on the chat screen.

Admittedly, that makes our experimental AA more strict than most real-world AAs. We believe that this is immaterial as the subjects are fully aware of this rule. The only alternative would be to have someone evaluate during the experiment whether the participants had made price agreements, which leads to obvious complications. Moreover, every cartel that was formed in our experiment did make price agreements; see below.

We include these to make subjects aware of their reporting decision.

This is different from practice and some other experiments where fines are a percentage of revenues. However, Bigoni et al. (2012, p. 371) argue for fixed fines to simplify the subjects’ decision problem and to have full control of subjects’ perceived expected fines.

This is in line with e.g. US and EU cartel enforcement, where reporting may lead to full leniency if the AA has not yet started an investigation.

Instructions for this treatment can be found in online Appendix B at http://marcohaan.nl/leniencyexperiment/. These are couched in neutral terms to avoid normative connotations that may be implied by terms like cartel or Antitrust Authority. Instructions for other treatments are similar and available upon request.

Our treatment Benchmark is comparable to treatment Communication in HS, and with Laissez-Faire in BFLS. Also, our treatment Antitrust is comparable to Fine in BFLS and Antitrust in HS.

Supporting materials for this paper can be found at http://marcohaan.nl/leniencyexperiment/.

Note that by construction, cartel incidence in Benchmark cannot decrease over time: A cartel can only be dissolved if it is detected by the AA. In Benchmark there is no AA.

The market price is the lowest price quoted in a market. Figures for each separate market can be found in online Appendix C at http://marcohaan.nl/leniencyexperiment/.

BFLS do not report how prices develop over time in their experiment.

Note however that in Benchmark a cartel cannot break down, so even if cartelists fall out with each other and start charging lower prices, they are still in a cartel.

Comparing prices in the first and last five periods, competition prices significantly (at 1%) increase in Profound and in the combined leniency treatments . For cartel prices, those in Benchmark significantly increase over time (at 10%; from 8.15 to 8.65). In all other cases, there is no significant trend.

A defection is defined here as any instance where subjects have an explicit agreement on price, but at least one subject sets a different price.

It is interesting to compare our chats with those of the infamous lysine cartel, for which a full transcript of all conversations is also available. All these conversations also contain explicit price agreements. See Hammond (2005).

Apart from Benchmark, there are only few instances of chats among subjects already in a cartel. Out of a total of 20 cartels in each of these treatments, in Antitrust there are 4 periods in which subjects communicate while already in a cartel, in Profound there are only 3 and in Superficial 11.

Instructions to coders and the full classification scheme are available upon request.

This measure is 0 when the amount of agreement is what random chance would imply, and 1 when the coders perfectly agree. Kappa values between 0.41 and 0.60 are considered as “moderate” agreement; those above 0.60 as “substantial” agreement (Landis and Koch 1977).

Instances in which coders did not agree are classified as one-half observation.

We define a conversation as the chat that takes place in a given market in a given period.

Unfortunately, the number of observations is too low to do detailed quantitative analyses of chat behavior to trace out possible differences between treatments.

In a companion note we study numerous other regression specifications, available online at http://marcohaan.nl/leniencyexperiment/.

Suppose that in a market, a cartel is already formed in the very first period. In that case, there has never been any competition in the first place, so we cannot include that observation in our analysis of the survival of competition. But that seems odd; our purpose is to study how quickly a cartel is formed; and if we do not include observations where cartels are formed immediately, we are surely missing something. We therefore effectively start our analysis in period 0, when arguably competition is in effect by construction. Thus, if subjects decide to form a cartel immediately, we interpret this as the formation of a cartel after 1 period of competition. If they decide to form a cartel in period 2, we interpret this as the formation of a cartel after two periods of competition, etc.

The interaction discovered*sup is not included as this yields too few events to allow for a robust estimate.

The interaction threats*anti is not included, as that yields too few observations.

We chose not to include past discoveries or past reports in this regression. Doing so yields insignificant coefficients. Details are available upon request.

References

Apesteguia, J., Dufwenberg, M., & Selten, R. (2007). Blowing the whistle. Economic Theory, 31(1), 143–166.

Bigoni, M., Fridolfsson, S. O., Le Coq, C., & Spagnolo, G. (2012). Fines, leniency and rewards in antitrust. RAND Journal of Economics, 43(2), 368–390.

Bigoni, M., Fridolfsson, S. O., Le Coq, C., & Spagnolo, G. (2015). Trust, leniency, and deterrence. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 31(4), 663–689.

Brenner, S. (2009). An empirical study of the European corporate leniency program. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 27(6), 639–645.

Brown-Kruse, J., Cronshaw, M. B., & Schenk, D. J. (1993). Theory and experiments on spatial competition. Economic Inquiry, 26(1), 139–165.

Bryant, P. G., & Eckard, E. W. (1991). Price fixing: The probability of getting caught. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 73(3), 531–536.

Cason, T. N. (1995). Cheap talk price signaling in laboratory markets. Information Economics and Policy, 7(2), 183–204.

Cason, T. N., & Mui, V. L. (2015). Rich communication and coordinated resistance against divide-and-conquer: A laboratory investigation. European Journal of Political Economy, 37, 146–159.

Clemens, G., & Rau, H. A. (2019). Do discriminatory leniency policies fight hard-core cartels? Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 28(2), 336–354.

Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20(1), 37–46.

Combe, E., Monnier, C., & Legal, R. (2008). Cartels: The probability of getting caught in the European Union. http://ssrn.com/abstract=1015061, Cahiers de Recherche PRISM-Sorbonne.

Cooper, D. J., & Kühn, K. U. (2014). Communication, renegotiation, and the scope for collusion. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 6(2), 247–278.

Davis, D. D., & Holt, C. A. (1998). Conspiracies and secret price discounts in laboratory markets. Economic Journal, 108(448), 736–756.

Dechenaux, E., & Mago, S. D. (2019). Communication and side payments in a duopoly with private costs: An experiment. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 165, 157–184.

Ellis, C. J., & Wilson, W. W. (2001). What doesn’t kill us makes us stronger: An analysis of corporate leniency policy. Tech. rep.: University of Oregon.

Fischbacher, U. (2007). z-tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Experimental Economics, 10(21), 171–178.

Fonseca, M. A., & Normann, H. T. (2012). Explicit versus tacit collusion: The impact of communication in oligopoly experiments. European Economic Review, 56(8), 1759–1772.

Fonseca, M. A., & Normann, H. T. (2014). Endogenous cartel formation: Experimental evidence. Economics Letters, 125(2), 223–225.

Friedman, J. W. (1971). A non-cooperative equilibrium for supergames. Review of Economic Studies, 38(1), 1–12.

Gomez-Martinez, F., Onderstal, S., & Sonnemans, J. (2016). Firm-specific information and explicit collusion in experimental oligopolies. European Economic Review, 82, 132–141.

Haan, M. A., Schoonbeek, L., & Winkel, B. M. (2009). Experimental results on collusion. In H. T. Normann (Ed.), Hinloopen J (pp. 9–33). Cambridge University Press: Experiments and Competition Policy.

Hamaguchi, Y., Kawagoe, T., & Shibata, A. (2009). Group size effects on cartel formation and the enforcement power of leniency programs. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 27(2), 145–165.

Hammond, S. D. (2001). When calculating the costs and benefits of applying for corporate amnesty, how do you put a price tag on an individual’s freedom? Presented at the 15th National Institute on White Collar Crime, 8 March. San Francisco CA.

Hammond, S.D. (2005). Caught in the act: Inside an international cartel. Presented at OECD, Paris, France, https://www.justice.gov/atr/speech/caught-act-inside-international-cartel.

Harrington, J. E., Hernan Gonzalez, R., & Kujal, P. (2016). The relative efficacy of price announcements and express communication for collusion: Experimental findings. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 128, 251–264.

Hinloopen, J., & Onderstal, S. (2014). Going once, going twice, reported! cartel activity and the effectiveness of leniency programs in experimental auctions. European Economic Review, 70, 317–336.

Hinloopen, J., & Soetevent, A. R. (2008). Laboratory evidence on the effectiveness of corporate leniency programs. RAND Journal of Economics, 39(2), 607–616.

Holt, C. A., & Davis, D. D. (1990). The effects of non-binding price announcements on posted-offer markets. Economics Letters, 34(4), 307–310.

Isaac, R. M., & Plott, C. R. (1981). The opportunity for conspiracy in restraint of trade. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 2(1), 1–30.

Isaac, R. M., & Walker, J. M. (1985). Information and conspiracy in sealed bid auctions. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 6(2), 139–159.

Isaac, R. M., Ramey, V., & Williams, A. W. (1984). The effects of market organization on conspiracies in restraint of trade. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 5(2), 191–222.

Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). An application of hierarchical kappa-type statistics in the assessment of majority agreement among multiple observers. Biometrics, 33(2), 363–374.

Miller, N. H. (2009). Strategic leniency and cartel enforcement. American Economic Review, 99(3), 750–768.

Motta, M. (2004). Competition policy: Theory and practice. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Motta, M., & Polo, M. (2003). Leniency programs and cartel prosecution. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 21(3), 347–379.

Normann, H. T., Rösch, J., & Schultz, L. M. (2015). Do buyer groups facilitate collusion? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 109, 72–84.

Spagnolo, G. (2000). Self-defeating antitrust laws: How leniency programs solve Bertrand’s paradox and enforce collusion in auctions. FEEM Working Paper No. 52.2000, Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.236400.

Spagnolo, G. (2008). Leniency and whistleblowers in antitrust. In: Buccirossi P (Ed.) Handbook of Antitrust Economics, M.I.T. Press, pp 259–304.

Waichman, I., Requate, T., & Siang, C. K. (2014). Communication in Cournot competition: An experimental study. Journal of Economic Psychology, 42, 1–16.

Acknowledgements

We thank two anonymous referees and the Editor, Lawrence J. White, for helpful comments, as well as Rob Alessie, Gerhard Dijkstra, Pim Heijnen, Jeroen Hinloopen, Praveen Kujal, Sander Onderstal, Amrita Ray Chaudhuri, Adriaan Soetevent, Laura Spierdijk, Nick Vikander, and Tom Wansbeek. Financial support of the University of Groningen (RUG) is gratefully acknowledged. The views expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the ACM: the authors are fully responsible for the contents of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dijkstra, P.T., Haan, M.A. & Schoonbeek, L. Leniency Programs and the Design of Antitrust: Experimental Evidence with Free-Form Communication. Rev Ind Organ 59, 13–36 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-020-09789-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-020-09789-5