Abstract

Relations between Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT) efficiency and operational performance, risk, and stock return are examined. REIT-level operational efficiency is measured as the ratio of operational expenses to revenue, where a higher operational efficiency ratio (OER) indicates a less efficient REIT. For a sample of U.S. equity REITs from the modern REIT era, operational performance, measured by return on assets (ROA) as well as return on equity (ROE), is negatively associated with previous-year operational efficiency ratios, which suggests that more efficient REITs generate better operating results. Results further show that more efficient REITs have lower levels of credit risk and total risk. Perhaps most important, empirical evidence shows that the cross-sectional stock return of REITs is partially explained by operational efficiency and that a portfolio consisting of highly efficient REITs earns, on average, a higher cumulative stock return than a portfolio consisting of low efficiency REITs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The literature focused on REITs is extensive. Most studies, however, focus on one of several broad areas including diversification benefits, acquisition strategies, differences in equity and mortgage investments, corporate governance and capital structure.Footnote 1 Few studies investigate relations between revenues from real estate assets and the expenses needed to generate those revenues. Specifically, little work has been applied to: (1) the appropriate classification of REIT revenues and expenses, such as gross rent, net rent, depreciation, amortization and tenant pass-throughs; and (2) exploring the performance and value implications associated with these relations. In the present research, we introduce measures of REIT operational efficiency similar to those found in the banking literature. These measures of efficiency, linking various types of operational expenses to revenues, are defined within a REIT context. The impact of these measures on REIT operational performance, risk and stock return is concurrently explored.

Efficiency in banking and financial institutions has been investigated in detail. The most common efficiency ratio found in the literature, and used by analysts and bank executives, is defined as a bank’s non-interest expenses divided by revenue or net income (Bikker and Haaf 2002; Bonin et al. 2005; Jacewitz and Kupiec 2012). In the Quarterly Banking Profile from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), efficiency is defined as “noninterest expense less amortization of intangible assets as a percent of net interest income plus noninterest income”. The FDIC further explains that “this ratio measures the proportion of net operational revenue that are absorbed by overhead expense, so that a lower value indicates greater efficiency.”Footnote 2 REITs are, in fact, like financial institutions in many ways. The National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts (NAREIT) defines a REIT as “A company that owns or finances income-producing real estate. Modeled after mutual funds, REITs provide investors of all types regular income streams, diversification and long-term capital appreciation. REITs typically pay out all of their taxable income as dividends to shareholders.”Footnote 3 A REIT is an intermediary that holds a portfolio of real estate assets and passes income and cash flows to its shareholders and its value should be related to how efficient it is in providing this service.

While some REIT studies focus on technical efficiency, X-efficiency and economies of scale (Kuhle et al. 1986; Anderson et al. 2000, 2002; Devaney and Weber 2005), this study employs an efficiency ratio that is based on the banking efficiency concept described above. The efficiency ratios used measure the amount of revenue REITs generate relative to operational expenses. Specifically, we create two REIT operational efficiency ratios defined as: a) total expenses less real estate depreciation and amortization expense to total revenue and b) total expenses less real estate depreciation and amortization expense adjusted for property specific expenses to total revenue less expense reimbursements.Footnote 4 In the accounting and financial economics literature, similar ratios of operating expense divided by annual sales are used as an agency cost proxy because they serve as a measure of the effectiveness of management in controlling operations and direct agency costs (Ang et al. 2000).

Using a broad sample of U.S. equity REITs from the modern REIT era, we show that REIT return on assets and REIT return on equity are strongly related to firm operating efficiency. The results suggest that more efficient REITs are associated with better operational performance.Footnote 5 Further results show that REIT total risk and credit risk benefit from greater operational efficiency. We also illustrate that REIT cross-sectional stock returns may be partially explained by operational efficiency. In addition, a portfolio consisting of more efficient REITs earns, on average, higher cumulative stock returns compared with a portfolio consisting of less efficient REITs. Overall, these findings illustrate the importance of REIT operational efficiency on performance, risk and return.Footnote 6

An Overview of Related Literature

There is a rich banking literature on the efficiency of financial institutions. Most of the literature focuses on four types or categories of efficiency. The first type is scale efficiency. The idea is that financial institutions benefit from economies of scale. Hence, larger firms are more likely to have better performance (Berger et al. 1993a, 1993b). The second category is scope efficiency, whereby financial institutions benefit from lowering average costs by producing and selling a wide array of products (Zardkoohi and Kolari 1994). The third efficiency measure is X-efficiency, which illustrates whether financial institutions are operating with an efficient mix of inputs, (Berger et al. 1993b; Allen and Rai 1996). Finally, the fourth and most common efficiency category is related to overall operational efficiency and is often measured with an efficiency ratio defined as non-interest expenses divided by revenues or net income (Bikker and Haaf 2002; Bonin et al. 2005; Jacewitz and Kupiec 2012). This efficiency measure is a straightforward indicator of overhead expenses relative to operational revenues. Financial institutions associated with lower ratios are more efficient.

Anderson et al. (2000) provide a comprehensive review of the efficiency literature for real estate brokerage services and REITs at the advent of the modern REIT era. Allen and Sirmans (1987), Linneman (1997), Bers and Springer (1997) and Vogel (1997) show that REIT mergers and acquisitions are due in part to the existence of economies of scale. Similarly, Anderson et al. (1998), (2002) analyze REIT scale economies and X-efficiencies using data envelopment analysis (DEA). They show that REITs are generally scale inefficient. In their narrow 1992–1996 sample period, REITs’ overall efficiency scores measured between 44.1% and 60.5% (out of 100%). They also show that large REITs are more efficient than small REITs and suggest that expansion may improve performance. Using a stochastic frontier methodology and Bayesian statistics to define REITs’ efficient cost frontiers, Lewis et al. (2003) find that REITs are almost 90% efficient and show that REIT performance and efficiency are positively related.

There is, however, conflicting evidence with respect to studies focused on economies of scale in REITs. For example, McIntosh et al. (1991) and (1995) provide evidence against the existence of scale economies. Similarly, Mueller (1998) and Ambrose et al. (2000) show that smaller REITs are more profitable, indicating there may be an optimal REIT size based on their cash flows. More recently, Chung et al. (2012) show that institutional ownership can help reduce REITs’ inefficiency. Other studies of the impact of institutional ownership on performance find few relations (Hartzell et al. 2014; Bianco et al. 2007; Bauer et al. 2010), with Hardin et al. (2017) arguing that only a small set of investors will expend sufficient energy to monitor to improve operating performance. The ambiguity may also be related to sample frame and the maturation of the REIT industry.

Bers and Springer (1998a, b) use the ratio of different REIT costs, such as general and administrative (G&A) expense, management fees, operating expenses, and interest expense, to total liabilities to examine scale economies. This measure, which is conceptually similar to the efficiency measures we use in this paper, allowed them to show a negative cost elasticity associated with interest expense related to total liabilities. In a related paper, Bers and Springer (1997) assess differences in scale economies among a variety of REIT characteristics and find that internal or external management choice, capital structure, and property types are related to their scale economies.

The present investigation builds on this existing, older literature primarily focused on the pre-modern REIT era by introducing efficiency ratios adjusted for industry characteristics as found in the banking literature. The questions of interest are straightforward. Does REIT efficiency impact operational performance measures? And, are REITs rewarded for their efficiency?

Data Sources and Summary Statistics

From SNL Financial, the main data source for this study, we collect firm characteristics for U.S. equity REITs for the modern REIT era (1995–2016) with annual frequency.Footnote 7 Each observation includes, total assets, total debt, total equity, total revenue,Footnote 8 total expenses, expense reimbursements,Footnote 9 real estate depreciation and amortization, rental operational expense, share price, total dividends paid, common shares outstanding, implied market capitalization, earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization, funds from operations (FFO), IPO date, the year the REIT was established, the metropolitan statistical area (MSA) of properties, and real estate property type.Footnote 10 We also obtain stock return data from the Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP) and market factors and risk-free rate data from Kenneth French’s website.Footnote 11

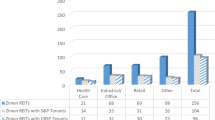

We define the REIT operational efficiency ratio (OER) in general terms as total operational expenses divided by revenue. Hence, the higher (lower) the efficiency ratio the less (more) efficient the REIT. More specifically, we define two variations of the general REIT operational efficiency ratio as: a) the ratio of non-real-estate-depreciation-and-amortization expense, defined as total expenses minus real estate depreciation and amortization, to total revenue, and b) the ratio of non-real-estate-depreciation-and-amortization expense adjusted for property expenses to total revenue less expense reimbursements. These two variations account for real estate depreciation and amortization and for property operational expense reimbursements to better reflect the more controllable cash flow related expenses associated with each REIT.

The cost of holding and maintaining real properties varies across property type as does lease structure. Hence, operational expense ratios likely vary due to the type properties owned. To address this issue, we employ measures that adjust for operational efficiency differences for REITs that are associated with real estate property types. These standardized operational efficiency measures (OER1 and OER2) are defined as the operational efficiency ratio of each REIT divided by the mean of the operational efficiency ratios of all REITs that specialize in the same real estate property type in that year.

To evaluate REIT operational performance, we compute return on assets (ROA), which is defined as funds from operations divided by total assets in the previous period. Similarly, we compute REIT return on equity (ROE), which is defined as funds from operations divided by total equity in the previous period.Footnote 12 REIT total risk is measured by the standard deviation of the annualized stock return and can also be referred to as stock return volatility. REIT credit risk is proxied by the EBITDA-to-Debt ratio. The stock return for a REIT is defined as the sum of share price change and dividends divided by share price in the previous period. Other variables used in this study include firm size, which is defined as the logarithm of implied market capitalization; leverage ratio, which is defined as the ratio of total book assets to total book equity, following Adrian and Shin (2010); firm age, which is defined as logarithm of one plus firms’ years since IPOFootnote 13; geographic diversification, which is defined as the negative of the Herfindahl Index of each REIT, calculated using assets invested in different MSA locations, based on book values, as in Hartzell et al. (2014); property type diversification, which is defined as the negative of the Herfindahl Index of each REIT, calculated using assets invested in different real estate property types, based on book values, as in Hartzell et al. (2014); and firm classification and whether the firm is in the S&P Index, which is a binary variable that takes a value of 1 when a REIT is in S&P index. The variables used in this paper along with their definition are displayed in Table 9 of the Appendix.

Because our regression specification includes lagged variables, we exclude firms with fewer than two consecutive years of stock price and operational efficiency information. Variables have been winsorized at the 1% and 99% tails of the distributions. The final sample used in the analysis consists of 317 REITs.

Table 1 provides summary statistics for the REITs included in the sample including operational performance, risk, stock return and operational efficiency measures. Over the full sample period (1995–2016), average REIT market capitalization has a mean of $2.3 billion and a median of $0.9 billion. Total REIT revenue per year has a mean of $0.4 billion and a median of $0.2 billion. Return on assets (ROA) has an average of 6.04% and a median of 6.05%, while return on equity (ROE) has an average of 16.39% and a median of 14.31%. The mean and median of annual stock return volatility are 0.30 and 0.23, and the mean and median for the EBITDA-to-Debt ratio are 0.19 and 0.16. The average annual stock return during the examined period is 12.99%, with a median of 12.97%. In terms of the operational efficiency ratios, the mean and median of the standardized operational efficiency ratio type one (OER1) are 0.99 and 0.96, and mean and median of the standardized operational efficiency ratio type two (OER2) are 0.99 and 0.91.

Research Methodologies

To begin the analysis, we first evaluate whether a REIT’s operational performance is associated with its operational efficiency ratios. Specifically, we regress REIT return on assets on each of our measures of operational efficiency while controlling for REITs characteristics. We use an ordinary least squares (OLS) model with heteroscedasticity-robust standard errors that are clustered at the firm level and with property type and year fixed effects (or with firm and year fixed effects), as per Eq. (1).

Where ROAi, t is the funds from operations divided by lagged total assets of REIT i at year t, and the other variables included in Eq. (1) are as defined earlier in the text. Additionally, we apply our multivariate regression from Eq. (1) using a non-parametric analysis approach by sorting REITs into quintiles based on their standardized operational efficiency ratios in each year. We also report the spreads of the mean and median of the ROA from the extreme quintiles, along with their associated two-sample t test and Wilcoxon rank-sum test values.

The use of lagged property portfolio characteristics as explanatory variables provides adjustment to reflect the beginning annual portfolios held by a REIT. Performance should be more reflective of the characteristics of the REIT properties at the start of the year than at the end of the year. This can be important in the REIT industry where holding periods are long-term and where the industry has expanded dramatically over the last two decades. Cash flow generation and expenses follow in large measure the properties held at the beginning of each period in combination with changes in the portfolio during the interim period versus the ending period composition of the portfolio. We also adjust other variables for comparability and in order to mitigate potential issues related to endogeneity. The general concept is to create the basic firm and managerial characteristics for the firm prior to the period of assessment.

For a visual illustration, figures that plot the measures of return on assets versus each of the standardized operational efficiency ratios for the previous year are provided. The slope, t-statistics, p-value and adjusted R-squared from the univariate regression associated with each figure are reported on the top of each figure.

Return on equity is another profitability ratio that measures the ability of a firm to generate profits. It can be argued from the shareholder’s perspective that return on equity is the best indicator of firm performance (Elayan et al. 2006) as an investment. Hence, we explore whether REIT return on equity (ROE) is associated with our two measures of operational efficiency.

where ROEi, t is the funds from operations, respectively, divided by lagged total equity of REIT i at year t, and other variables are as defined previously. As with Eq. (1), we apply our multivariate regression from Eq. (2) using a non-parametric analysis approach and create figures in which we plot the measures of return on equity versus each of the standardized operational efficiency ratios for the previous year.

A similar approach is used to examine the relations between REIT total risk, credit risk, and operational efficiency. Total risk is measured as annualized stock return volatility and credit risk is measured as the EBITDA-to-Debt ratio, which is an indicator of a REIT’s ability to satisfy its debt payment obligations. The regression specified in Eq. (3) examines this relation.

Where Riski, t is the annualized stock return volatility and EBITDA divided by total debt, respectively, of REIT i at year t, and the other variables are as previously defined. Once again, we apply our multivariate regression from Eq. (3) using a non-parametric analysis approach and create figures in based on risk measures and standardized operational efficiency univariate regression results.

Finally, we examine whether REIT operational efficiency ratios help explain the cross-sectional stock return of REITs. Specifically, we regress annual excess REIT stock return using the Fama and French (1993) three-factor model, the Carhart (1997) four-factor model and the Fama and French (2015) five-factor model while including the REIT operational efficiency variableFootnote 14:

Where Returni, t is the annual stock return of REIT i minus the risk-free rate at year t; rmrft is the value-weighted market return minus the risk-free rate at year t; smbt (Small minus Big), hmlt (High minus Low), momt (Momentum), rmwt (Profitability) and cmat (Investment) are the year t return to zero investment factor-mimicking portfolios designed to capture size, book-to-market, momentum, profitability and investment effects, respectively. β1 is the coefficient of interest in this regression, as it captures the relations between REIT stock return and the operational efficiency ratios after controlling for market risk.

Alternatively, we also adopt a similar approach to examine the relations between REIT stock return and REIT operational efficiency, as in Eq. (5).

Where Residual Returni, t is residual excess stock return, which is obtained from the Fama and French (2015) five-factor model, of REIT i at year t, and the other variables are as previously defined.

To further evaluate whether REIT operational efficiency ratios have a long-term effect on stock returns, we construct portfolios by sorting the standardized operational efficiency ratios (OER1 and OER2) of each REIT in the previous year. Specifically, we divide REITs based on the median (or 30 and 70 percentiles) of their OER1 and OER2, respectively, and place REITs with above or below median (or 70 or 30 percentiles) OER1 and OER2, in the low or high efficiency portfolios, respectively. These portfolios are rebalanced each year. We then compare the one- to four- year cumulative return of these operational efficiency based portfolios.

Empirical Results

Operational Performance and Operational Efficiency

As described in the methodology section, we first explore relations between the REIT operational efficiency ratios and REIT operational performance measured by return on assets (ROA) and return on equity (ROE). The results from Eq. (1) are reported in Panel A of Table 2. Overall, the results provide evidence that more efficient REITs have, on average, higher returns on assets, even after controlling for size, financing, management structure, diversification and growth strategy.

In columns (1) and (2), the coefficients of the previous year OER1 and OER2 variables are negative with statistical significance at the 1% level (−5.27 and −3.24, respectively) in a property type and year fixed effect model. These results suggest that more efficient REITs (lower efficiency ratio) generate higher ROAs. The results presented with a firm and year fixed effect model as in columns (3) and (4) are very similar to the results presented in columns (1) and (2) and display statistical significance at the 1% level. The estimated coefficients of −2.97 and −1.76 for the previous year OER1 and OER2 variables, respectively, suggest a positive relation between REIT efficiency and ROA.Footnote 15

In addition to the coefficients of interest, we also show that REITs with higher market capitalization, lower leverage and less geographic diversification are associated with higher ROA. This is in line with expectations and is consistent with the literature. Larger REITs usually perform better (Berger et al. 1993a, 1993b; Ambrose et al. 2005) and the negative relationship between firm performance and leverage is widely found in the finance literature (e.g. Titman and Wessels 1988; Rajan and Zingales 1995; Fama and French 2002). It is also well-known that there exists a diversification discount on firm performance or valuation, as in, for example, Lang and Stulz (1994), Capozza and Seguin (1999), Cronqvist et al. (2001), Campa and Kedia (2002), Danielsen and Harrison (2007), Ro and Ziobrowski (2011), Hartzell et al. (2014), and Ling et al. (2016).

It is worth noting that achieving a higher relative level of return on assets is difficult to do in a capital-intensive business such as equity REITs. This further highlights the importance of REITs operational efficiency on operational performance.

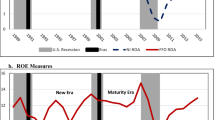

The positive relation between operating efficiency and operating performance also shows in our univariate regression models. Panel A of Fig. 1 plots ROA versus each of the previous year standardized operational efficiency ratios (OER1 and OER2). The negative slope is visually clear in each of the plots.

Operational performance and operational efficiency. This figure plots return on assets (ROA) and return on equity (ROE) on the vertical axis against two lagged standardized operational efficiency ratios (OER1 and OER2, respectively) on the horizontal axis for our sample period (1995–2016). The slope, t-statistics, p-value and adjusted R-squared are reported on the top of each figure. Standard errors are clustered at the firm level and are heteroscedasticity-robust. Significance at the 1%, 5% or 10% levels is shown with 3, 2, or 1 asterisks, respectively. All variables are defined in Appendix A1. Because our regression specification includes lagged variables, we exclude firms with fewer than two consecutive years of stock return and operational efficiency (OER1) information. Variables have been winsorized at the 1% and 99% tails of the distributions to avoid the influence of extreme observations

Panel B of Table 2 presents the results from a quintile analysis approach that compares REIT mean and median ROA sorted by their previous year standardized operational efficiency ratios (OER1 and OER2). The results show that the mean and median ROA of REITs sorted by previous year standardized operational efficiency ratios decrease monotonically from the first quintile (highest operational efficiency) to the fifth quintile (lowest operational efficiency) in both cases. The spreads of the mean (median) of ROA between the two extreme quintiles is 4.74% (4.27%) and 4.29% (3.73%), respectively. Each of these differences is statistically significant at the 1% level using the t-statistic from the two-sample t-test or the z-statistics from the two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum test. The results from the non-parametric analysis support the multivariate regression results and clearly show, not only positive relations between return on assets and operational efficiency, but that the relation is monotonic and continuous.

The results from Eq. (2) are reported in Panel A of Table 3. Overall, the results presented in this panel are very similar to the results reported in Panel A of Table 2, where the relationship between return on assets and operational efficiency is examined. The coefficients of our operating efficiency measures are negative and statistically significant in all four specifications. These results support our results from the previous table and suggest that REIT operating efficiency is positively related to return on equity. All else equal, if a REIT can decrease its OER1 by 1% it would realize an average ROE increase of 11.87 basis points (column (1)). Also, similar to the results from Panel A of Table 2, there is evidence for positive relations between return on equity and leverage. Consistent results can also be found in Panel A of Fig. 2, which plots ROE versus each of the previous year OER1 and OER2 measures. The negative slope (positive relation between operational efficiency and return on equity) is visually clear.

Firm risk and operational efficiency. This figure plots REIT’s total risk, which is measured as its annualized stock return volatility, and Credit Risk, which is measured as EBITDA-to-Debt Ratio, on the vertical axis against two lagged standardized operational efficiency ratios (OER1 and OER2, respectively) on the horizontal axis for our sample period (1995–2016). The slope, t-statistics, p-value and adjusted R-squared are reported on the top of each figure. Standard errors are clustered at the firm level and are heteroscedasticity-robust. Significance at the 1%, 5% or 10% levels is shown with 3, 2, or 1 asterisks, respectively. All variables are defined in Appendix A1. Because our regression specification includes lagged variables, we exclude firms with fewer than two consecutive years of stock return and operational efficiency (OER1) information. Variables have been winsorized at the 1% and 99% tails of the distributions to avoid the influence of extreme observations

Like Panel B of Table 2, Panel B of Table 3 presents the results from a quintile analysis. Again, the results of this panel are like the results presented in Table 2. The spreads of the mean and median of ROE between the first quintile (highest operational efficiency) to the fifth quintile (lowest operational efficiency) of REITs sorted by previous year standardized operational efficiency ratios are statistically significant at the 1% level.

Collectively, the results provide strong evidence that REIT operational performance is positively related to efficient management of the firm measured by the previous year’s operational efficiency. On average, more efficient REITs (lower operational efficiency ratios) generate higher returns on assets and returns on equity.

Firm Risk and Operational Efficiency

The results presented in this subsection shed light on the extent to which a REIT’s risk is associated with its operational efficiency ratios. As mentioned earlier, we measure REIT total risk using annualized stock return volatility and measure REIT credit risk using the EBITDA-to-Debt ratio. Stock return volatility plays an essential role in the finance literature, including asset pricing, cost of capital, risk management, and asset allocation. There is ample evidence that higher volatility is associated with higher expected returns. The EBITDA-to-Debt ratio measures the ability of a firm to withstand a negative shock to its profitability without defaulting on its debt obligations. This measure is especially important for REITs given that the real estate sector is more levered than most other industry sectors (Morri and Beretta 2008). Moreover, unlike other firms, the ability of REITs to fund investments via internally generated cash flows is limited due to their mandatory distribution requirement of at least 90% of earnings to shareholders. As a result, large REIT investments are more likely to be funded by the use of debt, at least in the short run, or an increase in share count.

The results from Eq. (3) when stock return volatility is the dependent variable are reported in Panel A of Table 4. The positive coefficients, 0.078 and 0.045, respectively, of previous year OER1 and OER2 in columns (1) and (2), with statistical significance at 1%, indicate that REITs with higher efficiency ratios (lower operating efficiency) have, on average, higher stock return volatility. The results presented with a firm and year fixed effect model as in columns (3) and (4) are very similar to the results presented in columns (1) and (2). The results imply that more efficient REITs (lower efficiency ratio) are exposed to less total return risk.

Regarding the other factors impacting firm level risk, the results are generally in line with the existing REIT literature (e.g. Tom and Austin 1996; Allen et al. 2000; Tien and Sze 2003). REITs with higher market capitalization are associated with lower total risk. Consistent with the REIT literature and what has been shown in banking (e.g. Demsetz and Strahan 1997), size-related diversification leads to reductions in firm-specific risk (e.g. Norman et al. 1995; Gyourko and Nelling 1998; Tom and Austin 1996). Younger REITs appear to be less risky, which warrants additional research and may be related to the newness of the REIT industry and conversions of private portfolios to publicly traded vehicles. Variables addressing more geographic diversification and inclusion in S&P indices, on average, have higher total risk in the property type and year fixed effect model as in columns (1) and (2). However, those variables are not statistically significant in the firm and year fixed effect model as in columns (3) and (4).

Like Fig. 1, Panel A of Fig. 2 plots the univariate results of stock return volatility versus previous year OER1 and OER2. The slope, t-statistics, p-value and adjusted R-squared are reported on the top of each figure. The results are consistent with the findings reported using multivariate regression.

Panel B of Table 4 presents the quintile analysis results. These results support the results presented in the previous panel. The means and medians of stock return volatility are monotonically increasing from the first quintile (highest operational efficiency) to the fifth quintile (lowest operational efficiency) of REITs sorted by previous year OER1 and OER2. The mean (median) difference between these extreme quintiles are 0.09 (0.05) and 0.08 (0.04) for OER1 and OER2, respectively, and associated with highly statistical significance.

When the EBITDA-to-Debt ratio is the dependent variable in Eq. (3), the results are reported in Panel A of Table 5. The estimated coefficients of OER1 and OER2 in columns (1) to (2) for EBITDA-to-Debt ratio are both negative (−0.13, and −0.09, respectively) and statistically significant at the 1% level. Quantitively similar results with a firm and year fixed effect model can be found in columns (3) and (4). Together, the results imply that more efficient REITs (lower efficiency ratio) are associated with lower debt levels relative to their cash flow. Aside from the coefficients of interest, we also show that REITs with lower debt are associated with less credit risk, as expected.

Panel B of Table 5 presents the quintile analysis results. The means and medians of EBITDA-to-Debt ratio are monotonically decreasing from the first to the fifth quintile. The spreads of the mean (median) between the two extreme quintiles are 0.11 (0.07) and 0.10 (0.06) for OER1 and OER2, respectively, and are significant at 1% level in both the two-sample t-test and Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Stock Return and Operational Efficiency

As a final step, after examining the relation between operational efficiency and operational performance and risk, we investigate whether REITs’ operational efficiency is related to their stock return.

Table 6 presents the OLS regression coefficient estimates of the Fama and French (1993) three-factor model, the Carhart (1997) four-factor model and the Fama and French (2015) five-factor model along with a REIT operational efficiency variable, as in Eq. (4). REIT stock return net of the risk-free rate is the dependent variable in these regressions. In each of the four specifications, the operational efficiency ratio used is found to be negative and statistically significant at the 1% level. More specifically, the estimated coefficients associated with OER1 in columns (1) to (3) are −9.74, −9.67 and −9.62, respectively, while those with OER2 in columns (4) to (6) are −6.33, −6.30 and −6.23, respectively.

The regression analysis indicates that a portion of REIT expected returns that cannot be explained by the common market factors is associated with REIT operational efficiency. As the efficiency ratios proposed in this paper measure the amount of revenue REITs generate relative to their operational expenses, such information should be unique for each REIT and not related to market-wide shocks from either real estate or capital markets.

In addition, we obtain the residual excess stock return from the Fama and French (2015) five-factor model and then explore relations between REIT stock return and REIT operational efficiency ratios. The results from Eq. (5) are reported in Table 7. The results provide evidence that more efficient REITs have, on average, higher stock returns which could not be explained by the common market factors, even after controlling for size, financing, management, diversification and growth strategy.Footnote 16 More specifically, the estimated coefficients associated with OER1 in columns (1) and (3) are −10.63 and −7.11, respectively, while those with OER2 in columns (2) and (4) are −6.45 and −3.57, respectively. The result suggests that REITs that exhibit higher operational efficiency are associated with higher risk-adjusted stock returns, as expected. REITs with operational effectiveness and efficiency generate better results for given portfolios of real estate, which is reflected in stock performance. REIT operational efficiency captures the relative ability to generate cash flows, which is concomitantly related to management of the firm and assets related to managerial structure, employee retention, and human capital.

Finally, to determine whether cumulative stock returns are different between high and low efficiency REITs, we construct portfolios by sorting REITs based on their previous year standardized operational efficiency ratio (OER1 and OER2) and then examine the cumulative return differentials for periods of one to four years after portfolio formation. The results of this analysis are illustrated in Fig. 3.

Cumulative return of stock portfolios sorted by standardized operational efficiency ratios. This figure illustrates the one- to four- year cumulative return of stock portfolios sorted by standardized operational efficiency ratios (OER1 and OER2). We construct portfolios by sorting REITs based on their previous year OER1 and OER2. Each year, we divide REITs based on the median (or 30 and 70 percentiles) of OER1 and OER2, and place REITs with above the median (or 70 percentiles) in the low operational efficiency portfolio and those below the median (or 30 percentiles) in the high operational efficiency portfolio. These portfolios are rebalanced each year. Then we investigate their one- to four- year cumulative return within each portfolio. All variables are defined in Appendix A1. Because our regression specification includes lagged variables, we exclude firms with fewer than two consecutive years of stock return and operational efficiency (OER1) information. Variables have been winsorized at the 1% and 99% tails of the distributions to avoid the influence of extreme observations

A glance at Fig. 3 reveals that, in the medium term, portfolios that consist of low efficiency REITs materially underperform portfolios that consist of high efficiency REITs. Specifically, the four-year cumulative return differential between the portfolio consisting of the bottom 30% of OER1 and the portfolio consisting of the top 30% of OER1 is about 8%, as showed in Panel A. Similarly, the four-year cumulative return differential between the portfolio consisting of the bottom 30% of OER2 and the portfolio consisting of the top 30% of OER2 is also as large as 8%, as showed in Panel B. These results are consistent with the findings we present in Table 5. Portfolios taken from the more efficient REITs outperform portfolios derived from the less efficient REITs.

Robustness Checks

Since we use lagged variables in explaining the relationship between REIT operational performance and operational efficiency in the prior analysis, a correlation table with current period and previous period variables is provided. The correlation table indicates whether our variables of interest persistent. Panel A of Table 8 shows the results on the pair-wise correlation of the regression variables. The operational performance of REITs is strongly correlated with their previous-year operational performance. The correlation of ROA at year t and year t-1 is 0.68, while the correlation of ROE at year t and year t-1 is 0.53. There exists high persistence in the operational efficiency measures. The correlation of current- and previous-year OER1 and OER2 is 0.63 and 0.64, respectively. More importantly, the correlation of ROA and ROE with current year OER1 (OER2) is −0.66 (−0.61) and −0.25 (−0.25), respectively, and previous year OER1 (OER2) is −0.43 (−0.40) and −0.09 (−0.10), respectively. As a higher operational efficiency ratio (OER) indicates a less efficient REIT, this result further suggests the existence of a positive relationship between REIT operational efficiency and operational performance.

Besides the possibility that lagged dependent variables may cause the coefficients for explanatory variables to be biased downward, if residual autocorrelation exists, the correlation results on current period and previous period variables also motivate us to further examine other relationships. Specifically, the relationship in cross-section by regressing REIT performance (ROA and ROE) on their current year standardized operational efficiency ratios (OER1 and OER2, respectively), while controlling for current year firm size, financing, management, diversification and growth strategy, as in eq. (1). The results of this analysis are reported in Panel B of Table 8. The estimated parameters for OER1 and OER2 are quantitatively and qualitatively greater than those reported in Tables 2 and 3, where the lagged variables are used. In a property type and year fixed effect model, the estimated coefficients of current year OER1 are −7.75 when the dependent variable is ROA and −18.61 when the dependent variable is ROE. The estimated coefficients of current year OER2 are −5.03 when the dependent variable is ROA and −12.66 when the dependent variable is ROE, with statistical significance at the 1% level, as in Columns (1), (2), (5) and (6). The estimated coefficients of current year operational efficiency measures are quantitatively and qualitatively similar in a firm and year fixed effect models as in Columns (3), (4), (7) and (8). These consistent results provide a further evaluation of the sensitivity of the estimated parameters and further confirming a positive relation between REIT efficiency and performance.

Conclusions

We define REIT operational efficiency and examine the extent to which REIT operational efficiency is related to operational performance, total risk, credit risk and stock return. Using a sample of U.S. equity REITs during the modern REIT era (1995–2016), results show that more efficient REITs are associated with higher operational performance measured by return on assets and return on equity. Similarly, the results of our analysis show that more efficient REITs post lower stock return volatility and are associated with lower credit risk, measured by their EBITDA-to-Debt ratio. Furthermore, we provide evidence that higher efficiency REITs outperform, on average, lower efficiency REITs in terms of risk-adjusted cross-sectional stock return as well as in terms of cumulative stock return in the medium term.

Collectively, our findings illustrate the importance of correctly measuring and accounting for REIT operational efficiency. This work has potential implications for REIT management, shareholder relations, REIT valuation, and portfolio allocation decisions. Moreover, a trading strategy that uses operational efficiency may yield higher returns. The research opens the door for more research on REIT operational efficiency to include institutional ownership and governance factors that might impact operational efficiency. Further research that examines in detail the importance of the components of REIT revenue and expenses concurrent with management and ownership structure will likely yield considerable insights.

Notes

The measure is adjusted to reflect those costs that are directly associated with asset operations and management. The adjustment is made for expenses that are passed through to tenants. Not all property expenses are reimbursed so we also control for property type, which is the primary determinant of reimbursements.

We recognize there still exists a potential endogeneity issue between operational efficiency and firm performance and there may be possible unobserved heterogeneity that determines the observed relation between operational efficiency and firm performance. As this is one of the first papers on the topic, it is likely that more research needs to be done to refine all potential conclusions.

Theoretically, a reverse causality issue for REIT risk, especially stock return volatility, stock return and REIT operational efficiency should not exist. The empirical results that REIT operational efficiency has a negative (positive) relation with one period ahead firm risk (stock return) can provide reliable casual inference. It is not likely that the lower risk and/or higher return causes higher operational efficiency.

The sample period starts in 1995 because the property level data are used to calculate geographic diversification and property type diversification are only available from 1995. For robustness, we extend the sample to a longer period and find quantitatively similar empirical results, while not controlling for diversification. We also only address publicly traded REITs as Seguin (2016), Soyeh and Wiley (2018) and others argue that these firms are sufficiently different to warrant segmentation.

All revenue including nonrecurring. Revenue is net of interest expenses for banks, thrifts, lenders, FHLBs, investment companies, asset managers and broker-dealers, as defined by SNL.

Expenses reimbursed from tenants for common area maintenance and improvements, including operating expenses such as real estate taxes, insurance, and utilities, as defined by SNL.

When REIT accounting information is not available in one period, but is available for the pervious and subsequent periods, it is replaced by the estimation calculated from the characteristics in previous and subsequent periods using the formula: \( {Value}_{i,t}^x=\left({Value}_{i,t+1}^x+{Value}_{i,t-1}^x\right)/2 \). Where \( {Value}_{i,t}^x \) is the value of x (TA, TE, etc.) of REIT i in year t.

Kenneth R. French’s Data Library: http://mba.tuck.dartmouth.edu/pages/faculty/ken.french/data_library.html.

These are common performance metrics for REITs.

When the IPO date is not available, we use the year a REIT status is established instead.

We recognize that REIT operational efficiency may also be an endogenous outcome of managerial decisions and other factors. For instance, ownership structure, corporate governance, investments in a growing market just by chance.

References

Adrian, T., & Shin, H. S. (2010). Liquidity and leverage. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 19(3), 418–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2008.12.002

Allen, L., & Rai, A. (1996). Operational efficiency in banking: An international comparison. Journal of Banking and Finance, 20(4), 655–672. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-4266(95)00026-7

Allen, P. R., & Sirmans, C. F. (1987). An analysis of gains to acquiring firm's shareholders: The special case of REITs. Journal of Financial Economics, 18(1), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(87)90067-5

Allen, M. T., Madura, J., & Springer, T. M. (2000). REIT characteristics and the sensitivity of REIT returns. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 21(2), 141–152. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007839809578

Ambrose, B. W., Ehrlich, S. R., Hughes, W. T., & Wachter, S. M. (2000). REIT economies of scale: Fact or fiction? Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 20(2), 211–224. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007881422383

Ambrose, B. W., Highfield, M. J., & Linneman, P. D. (2005). Real estate and economies of scale: The case of REITs. Real Estate Economics, 33(2), 323–350.

Anderson, R., Fok, R., Zumpano, L., & Elder, H. (1998). Measuring the efficiency of residential real estate brokerage firms. Journal of Real Estate Research, 16(2), 139–158.

Anderson, R., Lewis, D., & Springer, T. (2000). Operating efficiencies in real estate: A critical review of the literature. Journal of Real Estate Literature, 8(1), 1–18.

Anderson, R. I., Fok, R., Springer, T., & Webb, J. (2002). Technical efficiency and economies of scale: A non-parametric analysis of REIT operating efficiency. European Journal of Operational Research, 139(3), 598–612. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0377-2217(01)00183-7

Ang, J. S., Cole, R. A., & Lin, J. W. (2000). Agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Finance, 55(1), 81–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00201

Baker, H. K., & Chinloy, P. (Eds.). (2014). Public real estate markets and investments. USA: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199993277.001.0001

Baker, M., & Wurgler, J. (2006). Investor sentiment and the cross-section of stock return. Journal of Finance, 61(4), 1645–1680. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2006.00885.x

Bauer, R., Eichholtz, P., & Kok, N. (2010). Corporate governance and performance: The REIT effect. Real Estate Economics, 38(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6229.2009.00252.x

Berger, A. N., Hancock, D., & Humphrey, D. B. (1993a). Bank efficiency derived from the profit function. Journal of Banking and Finance, 17(2), 317–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-4266(93)90035-C

Berger, A. N., Hunter, W. C., & Timme, S. G. (1993b). The efficiency of financial institutions: A review and preview of research past, present and future. Journal of Banking and Finance, 17(2), 221–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-4266(93)90030-H

Bers, M., & Springer, T. (1997). Economies-of-scale for real estate investment trusts. Journal of Real Estate Research, 14(3), 275–290.

Bers, M., & Springer, T. M. (1998a). Sources of scale economies for REITs. Real Estate Finance, 14(4), 47–56.

Bers, M., & Springer, T. M. (1998b). Differences in scale economies among real estate investment trusts: More evidence. Real Estate Finance, 15(1), 37–44.

Bianco, C., Ghosh, C., & Sirmans, C. F. (2007). Corporate governance and firm performance - evidence from REITs. Journal of Portfolio Management, 33(5), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3905/jpm.2007.699613

Bikker, J. A., & Haaf, K. (2002). Competition, concentration and their relationship: An empirical analysis of the banking industry. Journal of Banking and Finance, 26(11), 2191–2214. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-4266(02)00205-4

Bonin, J. P., Hasan, I., & Wachtel, P. (2005). Bank performance, efficiency and ownership in transition countries. Journal of Banking and Finance, 29(1), 31–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2004.06.015

Brounen, D., & de Koning, S. (2013). 50 years of real estate investment trusts: An international examination of the rise and performance of REITs. Journal of Real Estate Literature, 20(2), 197–223.

Campa, J. M., & Kedia, S. (2002). Explaining the diversification discount. Journal of Finance, 57(4), 1731–1762. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6261.00476

Capozza, D. R., & Seguin, P. J. (1999). Focus, transparency and value: The REIT evidence. Real Estate Economics, 27(4), 587–619. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6229.00785

Carhart, M. M. (1997). On persistence in mutual fund performance. Journal of Finance, 52(1), 57–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1997.tb03808.x

Chung, R., Fung, S., & Hung, S. Y. K. (2012). Institutional investors and firm efficiency of real estate investment trusts. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 45(1), 171–211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-010-9253-4

Cronqvist, H., Högfeldt, P., & Nilsson, M. (2001). Why agency costs explain diversification discounts. Real Estate Economics, 29(1), 85–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/1080-8620.00004

Danielsen, B., & Harrison, D. (2007). The impact of property type diversification on REIT liquidity. Journal of Real Estate Portfolio Management, 13(4), 329–344.

Demsetz, R. S., & Strahan, P. E. (1997). Diversification, size, and risk at bank holding companies. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 29(3), 300–313. https://doi.org/10.2307/2953695

Devaney, M., & Weber, W. L. (2005). Efficiency, scale economies, and the risk/return performance of real estate investment trusts. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 31(3), 301–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-005-2791-5

Elayan, F., Meyer, T., & Li, J. (2006). Evidence from tax-exempt firms on motives for participating in sale-leaseback agreements. Journal of Real Estate Research, 28(4), 381–410.

Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (1993). Common risk factors in the returns on stocks and bonds. Journal of Financial Economics, 33(1), 3–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(93)90023-5

Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (2002). Testing trade-off and pecking order predictions about dividends and debt. Review of Financial Studies, 15(1), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/15.1.1

Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (2015). A five-factor asset pricing model. Journal of Financial Economics, 116(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2014.10.010

Giacomini, E., Ling, D. C., & Naranjo, A. (2017). REIT leverage and return performance: Keep your eye on the target. Real Estate Economics, 45(4), 930–978. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6229.12179

Gyourko, J., & Nelling, E. (1998). The predictability of equity REIT returns. Journal of Real Estate Research, 16(3), 251–269.

Hardin III, W. G., Nagel, G., Roskelley, K. D., & Seagraves, P. A. (2017). Motivated institutional monitoring and firm performance. Journal of Real Estate Research, 39(3), 401–439.

Hartzell, J. C., Sun, L., & Titman, S. (2014). Institutional investors as monitors of corporate diversification decisions: Evidence from real estate investment trusts. Journal of Corporate Finance, 25, 61–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2013.10.006

Jacewitz, S., & Kupiec, P. (2012). Community bank efficiency and economies of scale. FDIC Special Study.

Kuhle, J., Walther, C., & Wurtzebach, C. (1986). The financial performance of real estate investment trusts. Journal of Real Estate Research, 1(1), 67–75.

Lang, L. H., & Stulz, R. M. (1994). Tobin's q, corporate diversification, and firm performance. Journal of Political Economy, 102(6), 1248–1280.

Lewis, D., Springer, T. M., & Anderson, R. I. (2003). The cost efficiency of real estate investment trusts: An analysis with a Bayesian stochastic frontier model. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 26(1), 65–80. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021522231824

Ling, D. C., Ooi, J. T., & Xu, R. (2016). Asset growth and stock performance: Evidence from REITs. Real Estate Economics. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6229.12186

Linneman, P. (1997). Forces changing the real estate industry forever. Wharton Real Estate Review, 1(1), 1–12.

McIntosh, W., Liang, Y., & Tompkins, D. (1991). An examination of the small-firm effect within the REIT industry. Journal of Real Estate Research, 6(1), 9–17.

McIntosh, W., Ott, S. H., & Liang, Y. (1995). The wealth effects of real estate transactions: The case of REITs. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 10(3), 299–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01096944

Morri, G., & Beretta, C. (2008). The capital structure determinants of REITs. Is it a peculiar industry? Journal of European Real Estate Research, 1(1), 6–57. https://doi.org/10.1108/17539260810891488

Mueller, G. (1998). REIT size and earnings growth: Is bigger better, or a new challenge? Journal of Real Estate Portfolio Management, 4(2), 149–157.

Norman, E., Sirmans, S., & Benjamin, J. (1995). The historical environment of real estate returns. Journal of Real Estate Portfolio Management, 1(1), 1–24.

Rajan, R. G., & Zingales, L. (1995). What do we know about capital structure? Some evidence from international data. Journal of Finance, 50(5), 1421–1460. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1995.tb05184.x

Ro, S., & Ziobrowski, A. J. (2011). Does focus really matter? Specialized vs. diversified REITs. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 42(1), 68–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-009-9189-8

Seguin, P. J. (2016). The relative value of public non-listed REITs. Journal of Real Estate Research, 38(1), 59–91.

Soyeh, K., & Wiley, J. (2018). Liquidity management at REITs: Listed & public non-traded. Journal of Real Estate Research, forthcoming.

Tien, S., & Sze, L. (2003). The role of Singapore REITs in a downside risk asset allocation framework. Journal of Real Estate Portfolio Management, 9(3), 219–235.

Titman, S., & Wessels, R. (1988). The determinants of capital structure choice. The Journal of Finance, 43(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1988.tb02585.x

Tom, G., & Austin, J. (1996). Risk and real estate investment: An international perspective. Journal of Real Estate Research, 11(2), 117–130.

Vogel, J. H. (1997). Why the new conventional wisdom about REITs is wrong. Real Estate Finance, 14, 7–12.

Zardkoohi, A., & Kolari, J. (1994). Branch office economies of scale and scope: Evidence from savings banks in Finland. Journal of Banking and Finance, 18(3), 421–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-4266(94)90001-9

Acknowledgements

We thank an anonymous referee and C. F. Sirmans (Editor). Their insightful comments contributed to a much-improved paper. We are also grateful for helpful comments from seminar participants at the 2017 ARES annual meeting in San Diego and 2017 ERES annual conference in Delft. All errors remain those of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

This table presents the definition of variables used in the paper.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Beracha, E., Feng, Z. & Hardin, W.G. REIT Operational Efficiency: Performance, Risk, and Return. J Real Estate Finan Econ 58, 408–437 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-018-9655-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-018-9655-2