Abstract

This study investigates the effect of institutional ownership on improving firm efficiency of equity Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs), using a stochastic frontier approach. Firm inefficiency is estimated by comparing a benchmark Tobin’s Q of a hypothetical value-maximizing firm to the firm’s actual Q. We find that the average inefficiency of equity REITs is around 45.5%, and that institutional ownership can improve the firm’s corporate governance, and hence reduce firm inefficiency. Moreover, we highlight the importance of heterogeneity in institutional investors—certain types of institutional investors such as long-term, active, and top-five institutional investors, and investment advisors are more effective institutional investors in reducing firm inefficiency; whereas hedge funds and pension funds seem to aggravate the problem. In sub-sample analysis, we find that these effective institutional investors can reduce inefficiency more effectively for distressed REITs, and for REITs with high information asymmetry, and with longer term lease contracts. Lastly, we find that the negative impact of institutional ownership (except for long-term institutional investors) on firm inefficiency reduces over time, possibly due to strengthened corporate governance and regulatory environment in the REIT industry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The notion that a firm’s value should be maximized through efficient operation is central for corporate managers. Yet empirical evidence suggests that most firms are operated inefficiently due to a variety of reasons such as agency cost or financial distress. On the other hand, corporate governance theory suggests that institutional investors enhance corporate governance and hence increase firm value (Grossman and Hart 1980; Jensen 1986; Shleifer and Vishny 1986). However, the role of institutional ownership on improving firm efficiency is relatively unexplored. This paper examines this issue for Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs), using a stochastic frontier approach. To further investigate the underlying reason for institutional investors’ corporate governance role, we explore our result sensitivity for sub-samples based on the firm’s financial health, information asymmetry, agency cost, the types of institutional investors, and property types of REITs.

There are numerous reasons why firms are operated inefficiently. Financial distress and agency cost are two explanations. First, finance theory suggests that without successful access to external capital, financially distressed firms likely forgo investments with positive economic values, and thus operate inefficiently. Second, agency costs may be higher for industries or firms with greater information asymmetry. Managers consume perquisites at the expense of less-informed shareholders, and therefore, firm value is not maximized. The REIT industry seems to face more severe inefficiency problems, due to its following unique characteristics. For example, researchers argue that REITs score low in corporate governance and exhibit higher information asymmetry and agency cost [see Ghosh and Sirmans (2003), Han (2006), Bianco et al. (2007), and Francis, Lys, and VincentFootnote 1]. Several recently formed REITs had no outside directors, or were run by insiders with their own separate interests in the same properties held in the REITs.Footnote 2 Also, some REITs emerged from privately owned real estate development companies, and had family members in top management. The family’s interests and that of outside shareholders sometimes diverged.Footnote 3 Second, the high breadth of ownerships in REITs prevents possible hostile takeovers and mergers, which reduces the power of external monitoring [see Campbell et al. (1998), Ghosh and Sirmans (2003) and Eichholtz and Kok (2008)].Footnote 4 In addition, REITs are believed to extensively use excess shareholder provisions [see Chan et al. (2003)]. The provisions suspend voting rights and dividend payments if one single shareholder’s stake exceeds a hurdle rate (usually 10%), which makes managers fully entrenched. Lastly, the unique organizational structure of the majority of REITs, Umbrella Partnership REIT (UPREITs), also makes it more opaque to evaluate managers’ performance. Under the structure of UPREITs, managers are allowed to simultaneously manage several small REITs. Such entangled managerial structure might further aggravate agency problem.

In general, there are different mechanisms to reduce firm inefficiency and hence improve firm value/performance such as external monitoring by institutional investors.Footnote 5 Over the past decades, institutional investors become increasingly important and more visibly active in influencing firms for better performance.Footnote 6 They perform different activities in improving corporate governance practice, ranging from seeking board seats to improving the industry’s capacity and investment competitiveness.Footnote 7 The REIT industry offers a good setting to test the corporate governance role of institutional investors. Institutional ownership of REITs has nearly doubled over the past decades. After the passage of the Omnibus Reconciliation Act of 1993, institutional investors have dramatically increased their investments in REITs. The fraction of market capitalization of REITs held by institutional investors has increased from 28.5% in 1998 to 58.4% in 2005. High and increasing stake of institutional investors on REITs provides us with a good experimental setting to study the relation between institutional ownership and firm efficiency.

Nevertheless, institutional investors are heterogeneous. We expect that certain types of institutional investors are more effective in reducing firm inefficiency, due to their information and skills, their investment horizons, their incentives, etc. For example, long-term investors or investors with higher concentration of ownerships may have stronger incentives to improve corporate governance and firm efficiency. In some cases, these investors are willing to sacrifice their diversification costs to monitor because of greater incentives. As such, they should be able to provide better monitoring mechanism than other types of institutional investors.

Given the above motivations, this study sets out to examine the ability of various types of institutional investors in reducing firm inefficiency in the REIT industry. To measure firm inefficiency, we adopt stochastic frontier analysis—a widely-used technique in production economics.Footnote 8 Although this approach is relatively new in finance and real estate, it has drawn more attention recently. Barr et al. (2002), Habib and Ljungqvist (2005), and Nguyen and Swanson (2009) are three recent finance studies using the methodology to investigate the relation between inefficiency and firm values/performance. In real estate, Anderson et al. (2002), Anderson and Springer (2003), Lewis et al. (2003), Miller et al. (2006) use the technique to examine operating efficiencies and scale economies of REITs. Stochastic-frontier analysis is more advantageous than other efficiency approaches, because it minimizes the bias of outliers in estimating benchmark, and also controls for firm characteristics. Specifically, it hypothesizes a benchmark firm value (measured by Tobin’s Q), which is the optimal value of a firm if manager operates the firm efficiently. Any shortfall between the benchmark and actual firm value is measured as ‘inefficiency’.

Using data of 176 equity REITs from 1998 to 2005, we report that equity REITs in our sample have an average inefficiency of 45.5% based on the stochastic frontier analysis. Our empirical analysis yields the following results. First, we find that institutional ownership reduces firm inefficiency, supporting the theory that institutional investors enhance corporate governance. Moreover, certain types of institutional investors (long-term, active, top-five institutional investors, and investment advisors) exert positive influence in reducing firm inefficiency; whereas hedge funds and pension funds seem to aggravate the problem. Second, we find that certain types of firms are more inclined to operate inefficiently. Specifically, financially-distressed firms, and firms with higher information asymmetry all exhibit greater extents of inefficiency, and those institutional investors reduce inefficiency more effectively for these sub-groups. The result is in line with Habib and Ljungqvist (2005) and Nguyen and Swanson (2009), who report that inefficient firms subsequently outperform efficient firms by taking actions to improve their performance. Our finding implies that institutional ownership may motivate inefficient firms to take adequate actions to improve firm operations, supporting the monitoring theory. It is also consistent with Chung et al. (2002) and Hartzell and Starks (2003), who suggest that large shareholders and institutional investors are becoming increasingly active in corporate governance, especially in underperforming firms. It further supports the recent finding by Feng et al. (2010) that institutional owners do act as monitors in REITs and that governance is necessary for REITs. Third, our evidence suggests that institutional investors (particularly, long-term, active, top-five institutional investors, and investment advisors) are more effective in improving efficiency for REITs with longer lease terms (such as retail, office, and healthcare REITs). In contrast, inefficiency of REITs with short lease terms (such as residential and lodging REITs) is not affected by institutional ownership. This finding suggests that REITs with longer-term leases seem to be most susceptible to the inefficiency problem. Due to their long-term investment horizon and corporate governance skills, institutional investors are more specialized and effective in improving the efficiency of REITs with longer-term leases, which are subject to higher uncertainty and more severe incomplete contracting and moral hazard problems. Finally, we document time-varying effect of institutional ownership on reducing firm inefficiency. Despite of the fast growth of institutional ownership over time, the impacts of total, active, and top-five institutional investors on firm inefficiency in fact lessen during our study period, possibly due to strengthened corporate governance and regulatory environment in the REIT industry in the past decade. On the other hand, long-term institutional investors are effective in improving REIT efficiency in recent years.

Overall, we contribute to the existing real estate literature by providing evidence that institutional ownership improves REIT value and efficiency, and show that certain types of institutional investors can enhance firm performance: independent, long-term, active institutional investors (such as investment advisors) can effectively reduce firm inefficiency. In addition, we are among the first to show that the governance role of institutional investors varies with firm-types and property-types of REITs. We find that institutional investors can reduce inefficiency more effectively for distressed REITs, and for REITs with high information asymmetry, and with longer term lease contracts (with higher uncertainty and more severe incomplete contracting and moral hazard problems). Lastly, we add further insights and evidence on the time-varying monitoring and governance role of institutional investors, an important direction that is under-studied by existing literature.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section “Literature Review” provides literature review. Section “Methodologies and Hypotheses” describes methodologies and hypotheses. Section “Data and Summary Statistics” discusses the data and summary statistics. Empirical results are presented and discussed in Section “Results”. Finally, Section “Conclusion” concludes the paper.

Literature Review

Our paper investigates if institutional ownership can improve firm’s efficiency, what types of institutional investors are most effective, and for what firms are the institutional investors’ corporate governance role most important. Hence, this paper is related to and sheds new light to the following strands of literature.

Institutional Ownership and Firm Performance

Jensen and Meckling (1976) show that agency costs can be mitigated by giving shareholders enough equity stakes as incentives to perform monitoring and governance. Existing literature (Grossman and Hart 1980; Jensen 1986; Shleifer and Vishny 1986) suggests that institutional investors can provide monitoring function that reduces agency problems, and hence improve firm value. Informed institutional investors with sufficient ownership can exert external governance, replace the incumbent management and initiate takeover if necessary (Jensen and Meckling 1976; Shleifer and Vishny 1986; Admati et al. 1994).Footnote 9

Nonetheless, existing studies on the effect of institutional ownership on firm value are far from conclusive. Shleifer and Vishny (1986) find that large institutional investors have enough incentives to monitor the management, initiate takeover if necessary and thereby improve firm value. McConnell and Servaes (1990), Nesbitt (1994), Smith (1996), and Del Guercio and Hawkins (1999) find a positive relation between institutional ownership and firm performance. Gompers and Metrick (2001) support the impacts of institutional ownership on stock returns. Recent studies, including Chung et al. (2002), Hartzell and Starks (2003), Cornett et al. (2007), and Chen et al. (2007) support the corporate governance and monitoring roles of institutional investors in enhancing firm performance.

In contrast, Agrawal and Knoeber (1996), Karpoff et al. (1996), Duggal and Miller (1999), and Faccio and Lasfer (2000) do not find the positive relation between institutional ownership and firm performance. Wahal (1996), Gillan and Starks (2000), and Davis and Kim (2007) suggest that institutional investors are unable to improve firm long-term performance, due to their short-term focus, insufficient managerial skill, and own interests. Kahn and Winton (1998) and Noe (2002) suggest that instead of exerting external governance, institutional investors may choose to benefit from the information asymmetry from outsiders and avoid the cost of activism. In short, researchers have not yet reached an agreement on the impact of institutional investors on firm value.

Heterogeneity of Institutional Investors

Current literature provides evidence that institutional investors are heterogeneous economic agents in performing governance and influencing firm value. Some empirical findings suggest that certain types of institutional ownerships provide better monitoring mechanism than the others. In particular, independent institutional investors, such as investment advisors, mutual funds, or foreign institutional investors, provide better monitoring mechanism, while “grey investors” such as banks, insurance companies, or trusts with tighter business relationships with companies invested provide weaker monitoring mechanism. However, there is no conclusive agreement on what type(s)/characteristic(s) of institutional investors can improve firm performances.

As suggested by Almazan et al. (2005) and Chen et al. (2007), independent institutional investors, such as investment advisors and mutual funds, are in a better position, in terms of tools and motivations, to exert corporate governance. Ferreira and Matos (2008) report that independent institutions, with potentially fewer business ties to firms, provide better monitoring to firms. Brickley et al. (1988) find that banks and insurance companies are more supportive of management actions than other types of institutional investors in antitakeover amendment proposals due to their closer ties to firms’ managements.

Hedge funds can act as active shareholders in affecting corporate management decisions and hence improve firm performance. Bratton (2007), Briggs (2007), Hu and Black (2007), Brav et al. (2008), Clifford (2008), and Klein and Zur (2009) find that activist hedge funds are better informed and increasingly engage in monitoring than other types of institutional investors. Chung, et al. (2007) find that hedge funds are more informed investors, which have superior forecasting abilities of real estate stock returns relative to other institutional investors.

Institutional investors can also be categorized based on their objective horizons. With regards to the impact of short-versus long-term investors on firm value, Yan and Zhang (2009) find that short-term investors are better informed about a firm’s near-term future perspective, and thus short-term institutional investors have better predictability on stock performance than long-term institutional investors. Polk and Sapienza (2009) argue that managers cater to short-term investors, and only select investments that boost short-run stock prices. Chen et al. (2007) show that independent institutions with long-term investments will specialize in monitoring during takeover.

Corporate Governance in REITs

REITs have high breadth of ownership. REITs need to have at least 100 shareholders, and no more than 50% of a REIT’s share can be owned by five or fewer shareholders (the “five or fewer” rule). The lack of blockholders reduces possibility of hostile takeovers, which might reduce the power of external monitoring [see Ghosh and Sirmans (2003) and Eichholtz and Kok (2008)]. Thus, it implies that institutional investors play a more important role in external corporate governance monitoring. The legislation change in 1993 might mitigate the problem of lacking possible hostile takeovers. After the passage of the Omnibus Reconciliation Act of 1993, institutional investors are not considered as a single stockholder. Instead, their ownerships are passed through to their beneficiaries. As a result of the legislation change, both the number and influence of institutional investors increased dramatically in REITs. An increase in institutional ownership is believed to provide external monitoring power, reduce agency problem, and enhance firm performance.

Hartzell et al. (2006) examine the relation between REIT investments and property-type Q, and find that the investment choices of REITs are more closely tied to Tobin’s Q if they have higher institutional ownership or if they have lower director stock ownership. Other studies investigate institutional investors’ holdings in REITs, and conclude that the presence and holdings of institutional investors and large shareholders in REITs have increased drastically in the post-1990 period (Ling and Ryngaert 1997; Ghosh et al. 1997; Chan et al. 1998, among others). Devos et al. (2007) study Tobin's Q and analyst coverage in different types of REITs. The authors find that analyst coverage increases Tobin's Q, and that mortgage REITs are the most transparent. More recently, Feng et al. (2010) provide evidence on the influence of institutional investors on governance through CEO compensation. They find that greater institutional ownership is associated with greater emphasis on incentive-based compensation, and higher cash compensation to induce CEOs to take greater risk. In short, the channel of institutional ownership in affecting REITs corporate governance and performance is still a new and important terrain for research.

Efficiency Studies in REITs

Existing real estate literature applies stochastic frontier analysis to study operating efficiencies. There are four papers that estimate REIT operating efficiency using stochastic frontier analysis. Anderson et al. (2002) apply frontier technique to calculate inefficiency and economies of scales for REITs, with 1992–1996 data. Anderson and Springer (2003) calculate inefficiency for REITs from 1995 to 1999. Both studies report large scales of cost inefficiency for REITs, ranging from 45 to 60%. On the other hand, Lewis et al. (2003) and Miller et al. (2006) report a smaller scale of cost inefficiency for REITs. The disparity in findings is due to different frontier methodologies adopted in these two sets of studies. Nonetheless, existing literature on REITs has not examined whether institutional investors can reduce firm inefficiency.

The main difference between the existing stochastic frontier studies in real estate and in finance is the dependent variable adopted in the analysis. Finance studies apply the stochastic frontier analysis to examine firm value (proxy with Tobin’s Q), whereas real estate studies primarily investigate operating cost. Therefore, we are motivated to apply this relatively new technique to explore firm value of REITs, and also examine the impact of institutional investors on firm value. To the best of our knowledge, our study is among the first to investigate firm value and efficiency of REITs with stochastic frontier analysis.

Methodologies and Hypotheses

Methodologies

Stochastic Frontier Analysis

We follow Habib and Ljungqvist (2005) and Nguyen and Swanson (2009), and estimate firm inefficiency with stochastic frontier analysis. Stochastic frontier analysis assumes that a firm’s theoretical maximum value can be estimated by an optimal Tobin’s Q*. This optimal Q* is estimated with efficient frontier analysis, so that firms’ growth opportunities and characteristics attribute to the optimal value. The firm’s actual Q may be equal to, or smaller than the benchmark Q*. If a firm’s actual Q equals to its optimal Q*, its value has been maximized. In contrast, if a firm’s actual Q is smaller than its benchmark Q*, the shortfall (Q*-Q) suggests inefficiency caused by firm manager’s decisions and is a measure of agency cost [Habib and Ljungqvist (2005)]. Theoretically, managers should act in the best interests of shareholders to maximize firms’ value. However, agency problems or financial distress may prevent managers from maximizing firm values.

Stochastic frontier analysis has several advantages over traditional efficient frontier analysis [see Habib and Ljungqvist (2005)]. First, it controls for firm characteristics and growth opportunities, so that a firm’s hypothetical maximum value is estimated from its own characteristics. Second, shortfall of firm value might be caused by white noise or inefficiency. To single out inefficiency from white noise, the analysis assumes an error model which consists of two error terms: one is a two-sided random error to capture white noises, and the other is a one-sided error term to capture true inefficiency. Third, the one-sided error term in the ordinary least-squares methods (OLS) also reflects the fact that firms will never lie above the efficient frontier. Finally, the analysis is stochastic so that outliers do not cause bias in estimating the optimal benchmark Q*.

Note that the stochastic frontier analysis implicitly assumes that Tobin’s Q is adapted as the measure for firm performance. Although our research does not adopt other performance measures such as cash flows or growth opportunities, we implicitly incorporate these alternative measures in Tobin’s Q. Tobin's Q is presumably a market valuation of expected future cash flows of a firm discounted by its growth opportunities. That is, in the traditional dividend-growth model, value of stock = future cash flows / (r–g), where r is the risk-adjusted discount rate of the firm and g accounts for growth opportunities. Therefore, Q implicitly measures firm value including assets-in-place and future growth options.

Equation 1 below specifies the frontier. To estimate the optimal benchmark Q* of a comparable but value-maximizing firm, we estimate the frontier using stochastic frontier analysis. We follow similar procedure used by Habib and Ljungqvist (2005). We select the variable set to construct the optimal benchmark Q* based on economic theory, in particular the economic variables that can determine firm efficiency, and control for differences in firms’ characteristics and opportunity sets. We base our empirical specification on results established in prior literature such as Habib and Ljungqvist (2005). Equation 2 presents the shortfall (inefficiency) where a departure from the frontier is suggestive of inefficiency and is a measure of agency cost.

The meaning of each variable is described as follows:

-

Q it is Tobin’s Q (market to book equity ratio), the dependent variable.

-

∆asset it is change of total asset, a proxy for investments.

-

lev it is leverage, measured as long-term debt over total assets.

-

ln(ocf it ) measures log of operating cash flow. It serves as a proxy for profitability.

-

beta it is estimated from the market model on monthly returns over the preceding 5-year period.

-

ln(sales it ) measures log of total sales, a proxy for firm size.

-

ln(sales it 2 ) captures the non-linear relationship between Tobin’s Q and firm size.

-

v it is the two-sided error term in the conventional ordinary least-squares (OLS) method, and has a normal distribution with zero-mean, and symmetric, independent, and identically (i.i.d.) distributed error.

-

u it is the one-sided error, and is greater than or equals to zero. For firms that lie on the efficient frontier, u it = 0. In contrast, u it > 0 for inefficient firms which lie below the frontier. We also assume cov(v it , u it ) = 0 to assure that two error terms are independent and uncorrelated.

To compute firm inefficiency using stochastic frontier analysis, we follow similar procedure used by Habib and Ljungqvist (2005). Once the parameters of independent variables have been estimated, a predicted value of u it is obtained for each firm and for each year as the shortfall (inefficiency). The shortfall (inefficiency), a departure from the frontier is suggestive of inefficiency, is then normalized to assure that it is between 0 and 1. That is, we take the ratio of a firm’s shortfall (inefficiency) to the corresponding optimal benchmark Q*. Similar to Habib and Ljungqvist (2005), the shortfall (inefficiency) will also be [1—predicted efficiency] where predicted efficiency is the ratio of a firm’s actual Q to the corresponding optimal benchmark Q* of a comparable but value-maximizing firm.

Equation 3 below specifies the normalization procedure.

Different Types of Institutional Investors

To identify the type(s) of institutional investors that can reduce firm inefficiency, we stratify institutional investors based on multiple attributes and economic theories, including institutional investors’ incentives (using concentration of equity ownership), investment horizons, investment styles, information acquisition skills, and independence. Using different stratifications, we define different types of institutional investors as follows:

-

Institutional ownership (io) is the percentage of shares held by institutional investors.

-

Top-five institutional ownership (iofiv) is the percentage of shares held by the top five institutional investors. It is a measure of concentration of institutional ownerships [see Gompers and Metrick (2001)].

-

Active institutional ownership (ioactive) is the percentage of shares held by active institutional investors, based on the investment style reported in Thomson Ownership Database. Active institutional investors have more aggressive investment strategies. Active strategies include picking attractive stocks, timing the market, and using leverages. These strategies allow active institutional investors to exploit industry-or firm-specific information.

-

Short-term institutional ownership (iost) is the percentage of shares held by short-term institutional investors, while the long-term institutional ownership (iolt) is the percentage of shares held by long-term institutional investors. The short-term and long-term institutional investors are classified based on the methodology developed in Yan and Zhang (2009).

Following Yan and Zhang (2009), we use the formulae below to compute the churn rate. Index firms in which investors can hold long positions by j = 1,...,J. Let P jq be the price per share for firm j, and let S ijq be the number of shares of firm j that are held by institution i, both measured at the beginning of quarter q. The net non-zero activity by investor i in firm j across quarter q-1 is then:

Then, we compute the average churn rate (av_churn) over the past 4 quarters for each institution, and rank institutions based on this average churn rate. Those institutions ranked in the top tertile for the average churn rates (with the highest av_churniq ) are classified as short-term institutional investors, and those ranked in the bottom tertile are classified as long-term institutional investors. Then, for each stock, we define the short-term (long-term) institutional ownership as the ratio between the number of shares held by short-term (long-term) institutional investors, and the total number of shares outstanding.

Hypotheses

Institutional Investors and Firm Inefficiency

Our primary hypothesis is that institutional ownership mitigates firm inefficiency by improving corporate governance. There should be a negative relationship between firm inefficiency and institutional ownership.

Different Types of Institutional Investors

We hypothesize that institutional investors are heterogeneous—certain types of institutional investors improve corporate governance and thus reduce inefficiency more effectively than other institutions. To add insights into what types of institutional investors can ultimately improve firm efficiency and governance, we stratify different types of institutional investors based on their incentives (using concentration of equity ownership), investment horizons, investment styles, information acquisition skills, and independence. Using different stratification schemes, we study the impacts of the following different types of institutional investors on firm inefficiency.

-

(a)

All versus top-five institutional equity holdings. With higher equity stake in the firm, we hypothesize that top-five institutional investors with concentrated ownership should have more significant impact on reducing inefficiency than the rest of the sample. This hypothesis implies that institutional investors with higher stakes explicitly improve corporate governance by direct monitoring. These investors have higher incentives to monitor due to their concentrated ownerships.

-

(b)

Short-term versus long-term equity holdings. Prior studies have found that short-term and long-term institutional investors are heterogeneous in firm valuation. We hypothesize that long-term institutional investors should have more significant impact on firm inefficiency due to their longer investment horizon.

-

(c)

Active versus passive institutional investors. If passive institutions (such as index funds) buy shares to mimic the positions of stock index compositions, we do not expect any monitoring effect for these institutions. On the other hand, active institutional investors are often more aggressive in developing investment strategies by exploiting firm-specific information. As such, they are likely to be more informed and more motivated to perform monitoring activities and acquisition of firm information. Hence, we hypothesize that active institutional investors should improve firm inefficiency better than passive investors.

-

(d)

Independent versus grey institutions. Examples of independent institutional investors include investment advisors, research firms, and mutual funds. These institutions are less regulated and usually are considered more independent and objective in collecting firm’s information than other institutional investors. They probably have the least potential business ties with the firms they invest in. We expect this group to be more effective in providing corporate governance.

For example, investment advisors are better equipped and more active and independent in providing effective monitoring functions than other institutional investors, and hence they can be more prominent in influencing the quality of corporate investments. In the United States, investment advisors are subject to a complex registration process by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and owe their clients an ongoing fiduciary duty to provide full and complete disclosure and to invest with their clients' best interests. As suggested by Almazan et al. (2005) and Chen et al. (2007), investment advisors are independent institutional investors, which are in a better position, in terms of tools and motivations, to exert positive impacts on corporate investment decisions. Bushee and Goodman (2007) find that informed trading is most evident for new firms in which investment advisors and large institutions invest.

In contrast, examples of grey institutions include pension funds, banks, and insurance companies. These institutions are more tied to firms they invested in, and thus more subjective in terms of monitoring corporate governance. As such, we expect these grey institutions to show a less significant effect or even a negative effect on inefficiency. For example, banks and insurance companies, through their trust departments, often have existing or potential business associations with the firms in which they invest. They are less willing to challenge management decisions to protect their relationships with firm management. As such, they are often considered as “grey investors” that are less likely to provide independent monitoring, important influence on corporate investments and effective corporate governance. Pension funds are more divergent, and they may not have much of a significant impact on firm performance through influencing corporate investments. Literature such as Del Guercio and Hawkins (1999) suggests that whilst some pension funds act as independent investors, others exhibit the features of grey investors.

Furthermore, hedge funds are considered as a unique class of institutional investors. On the one hand, hedge funds are not associated with the companies that they invest in. As such, they are considered independent institutions. On the other hand, compared to investment advisors, hedge funds are less regulated and allowed to use high leverages. Therefore, they usually undertake a wider range of investment and trading activities that are more aggressive in generating higher total returns, potentially to get bigger bonuses for fund managers. Hence, hedge funds may have a shorter investment horizon. If improving the firm’s efficiency requires long-term commitment, then hedge funds may not be able to improve the corporate governance and hence the firm’s efficiency. As a result, we do not have a pre-determined sign for the impact of hedge funds on improving inefficiency.

After we estimate Eq. 1, we assume that efficiency shortfall u was caused by the conflict of interests between managers and shareholders, and can be mitigated by the governance variables in the following regression

where inefficiency as defined in Eq. 3 is the shortfall in efficiency relative to the optimal Q*, and the meaning of the io_type variable is described as follows:

-

io is the total equity institutional ownership, defined as percentage of shares owned by institutional investors.

-

iofiv is the percentage shares held by the largest five institutional investors.

-

iost is the percentage shares held by short-term institutional investors, and iolt is the percentage shares held by long-term institutional investors. Short-term and long-term institutional investors are classified based on the methodology outlined in Yan and Zhang (2009).

-

ioactive is the percentage shares held by active institutional investors, based on the investment style reported in Thomson Ownership Database.

-

iobank, iohedge, ioadvsr, ioinsur, iopnsn, ioadvhg, and iorsrch are the percentage shares held by banks, hedge funds, investment advisors, insurance companies, pension funds, investment advisor/hedge funds, and research companies, respectively, as reported in Thomson Ownership Database.

Financial Distress, Information Asymmetry, and Agency Cost

Financially distressed firms are more apt to suffer from inefficiency. Without access to external capital, firms may be forced to forgo investments with good growth opportunities, and thus firm value is not maximized. We hypothesize that institutional ownership decreases inefficiency especially for distressed firms. We measure financial distress with three variables: residual standard deviation, book-to-price ratio, and market capitalization. The first variable, residual standard deviation, is a proxy for firm-specific risk. Firms with high financial distresses tend to have higher firm-specific risks. The second proxy, book-to-price ratio, is expected to be higher for distressed firms, since stock price tends to be depressed when a firm faces financial difficulties. Lastly, we expect companies with lower stock prices and hence smaller market capitalization are more inclined to become financially distressed.

Firms with higher degrees of information asymmetry are more likely to incur greater agency costs, which leads to higher inefficiency. Managers act in their own best interests at the expense of less informed minority shareholders. As such, firm value is not maximized due to agency problem. We expect inefficiency to be higher for firms with greater information asymmetry, and that institutional monitoring should mitigate inefficiency for firms with higher information asymmetry. We proxy information asymmetry with two measures: shares turnover, and whether the firm is followed by financial analysts. Firms with higher shares turnover (market liquidity) are less subject to information asymmetry problem because they are more likely to subject to market monitoring due to active trading activities.Footnote 10 On the other hand, firms followed by financial analysts should exhibit a lower degree of information asymmetry.

We also study the effect of agency cost on inefficiency using dividend-to-book ratio as proxy. Free cash flow theory suggests that a high dividend payout reduces cash in hand for managers.Footnote 11 As such, managers are less likely to indulge themselves with perquisites. Thus, we expect that firms with higher dividend payout ratios to have lower agency cost, and thus, those firms are more prone to operate efficiently. Furthermore, the positive impact of institutional investors on reducing inefficiency should be more significant for firms with lower dividend payout ratios.

Different Types of REITs

According to National Association of Real Estate Investment Trust (NAREIT), equity REITs can be categorized into several groups: office, retail, residential, healthcare, and lodging/resorts. Each category has distinct characteristics. Office REITs are deeply cyclical due to their long lead time to complete constructions. They tend to overbuild during economic booms. In addition, their long lease terms (averaging 7–10 years, or longer) put them in a disadvantage position when the economy is in a downturn. Retail REITs own and operate retail properties such as shopping malls. They earn revenue by leasing those properties to retail tenants. Retail REITs are also sensitive to economic cycles. Like office REITs, retail REITs tend to have relatively long lease terms, averaging from 8 to15 years. In contrast, residential REITs own and manage rental apartments, and have relatively short lease terms because rental agreements are renewed annually. Residential REITs have higher leverage (financial risk) than average REITs, and carry higher local market risk than the average because of their locations and demography.Footnote 12 Lodging/Resort REITs are also highly cyclical because consumers’ entertainment need is sensitive to economic downturns. They have the shortest lease terms (daily lodging rates) compared to other property types of REITs. Healthcare REITs own and sometimes operate health care properties such as nursing homes, medical clinics, and hospitals. They are more recession resistant due to economy’s steady demand for health care facilities. Some tenants of healthcare REITs receive reimbursements from the government. Lease terms for healthcare REITs vary widely, depending on tenants. Small tenants tend to sign shorter leases, usually less than 5 years; whereas large tenants are more likely to sign long-term leases, ranging from 12 to 15 years.Footnote 13

We expect the corporate governance role of institutional investors depends on the underlying lease terms for the REITs, due to moral hazard problem. Moral hazard problem arises when one party (managers) has more information than the others (less informed minority shareholders) and does have to pay for the full consequence. Thus, it behaves in its best own interests, leaving another party to pay for the consequences. Theory suggests that the moral hazard problem is more severe with longer-term contracts due to higher uncertainty and monitoring costs, and subsequently reduces manager’s potential to operate the firm inefficiently. We argue that REITs with longer-term leases are more susceptive to the moral hazard problem. Once the lease contract is signed between the customers and the management, the management has strong incentive to pursue self-serving behavior (for example, perquisite consumption) rather than maximizing firm-value. The longer lease terms imply higher uncertainty and monitoring costs, and hence, more severe incomplete contracting problem. Hence, we expect monitoring activities of longer term leases to become specialized and more effective for those institutional investors who have comparative advantages due to efficiency, information, and incentives. In other words, we expect active institutional investors with high equity stakes and long-term orientations to be able to reduce the moral hazard problem and hence the inefficiency.

To examine the difference of long-and short-term institutional investors at improving efficiency of REITs, we classify REITs into three groups based on their lease terms. Long-term REITs include office and retail REITs. Short-term REITs include residential and lodging/resort REITs. Due to the wide variation of lease terms in healthcare REITs, we categorize healthcare REITs as medium term.

Data and Summary Statistics

This study analyzes a sample of 176 equity REITs from NYSE, AMEX, and NASDAQ over the 1998 to 2005 period, with 1,075 firm-year observations. Annual financial data are obtained from the CRSP/Compustat database, and the percentage equity stake data, as of June-end of every year of different institutional investors, comes from the Thomson Ownership Data. Thomson reports the security holdings of institutional investors with greater than $100 million of securities under discretionary management.Footnote 14 Institutional ownership data are then matched to the following fiscal year financial statement data from Compustat.

Exhibit 1 provides summary statistics of equity REITs in our sample, for low and high inefficiency subsamples. The average inefficiency for the entire sample is 45.5% (with median of 45.8% and standard deviation of 5%). Compared to 16% of inefficiency for industrial firms reported by Habib and Ljungqvist (2005) and 30% of inefficiency reported by Nguyen and Swanson (2009), equity REITs are much more inefficient. However, our findings are in line with those of Anderson et al. (2002) and Anderson and Springer (2003), who report a 45% to 60%of operating inefficiency for REITs.

Several possible explanations may attribute to the significant inefficiency of REITs in our findings. First, equity REITs own real estate properties that are sometimes difficult for shareholders to value. Managers might possess private information about the true value of the properties, therefore, making REITs more subject to asymmetric information problem and thus incur more inefficiency than industrial firms. Second, it is well documented that most REITs nowadays are actively managed after a structural change in 1993, compared to passive management style in the pre-1993 period.Footnote 15 As such, REITs are more susceptible to the asymmetric information and agency problems than other types of firms due to active management [see Ling and Ryngaert (1997), Friday et al. (2000)]. Third, a large percentage of REITs are formed as Umbrella Partnership REITs (UPREITs). This unique organizational structure allows a managing partner to manage properties under several smaller REITs, which makes it more opaque to evaluate manager’s performance and value of REITs, and more likely to create larger inefficiency and hence agency problems. Furthermore, because of the requirement of dispersion of ownerships in REITs (the “five or fewer rule”), there are very few hostile takeovers or mergers in the sector, which in turn potentially causes agency problem [see Ghosh and Sirmans (2003) and Eichholtz and Kok (2008)].

All the possible causes of high inefficiency of REITs discussed above can attribute to agency problem. Managers of REITs are believed to have insider information about the underlying assets in place than outsiders. In addition, the complex organizational structure of UPREITs makes valuation of real estate properties or evaluation of managers’ performance more difficult. All these factors aggregate agency problem. Thus, agency problems in REITs are believed to be more severe than those in industrial firms.

On average, institutional investors accounts for 37% of ownership for equity REITs. Sub-sample analysis further reveals that more inefficient firms have lower percentage owned by institutional investors, and the difference is economically and statistically substantial. This phenomenon persists across different types of institutional investors such as active, top-five, long-term, and short-term institutional investors. Furthermore, highly inefficient firms tend to have higher systematic risks (measured as beta), higher non-systematic risks (measured as residual standard deviation), lower liquidity (measured as shares turnover), higher book-to-price ratio, and lower market capitalization. They are also less likely to be followed by analysts and have lower dividend payout ratio. The differences of these firm characteristics between two sub-groups are all economically and statistically significant. The findings are consistent with our hypotheses—firms with higher financial distress risks or agency costs are more likely to operate inefficiently.Footnote 16 Lastly, the average market capitalization of REITs is $1 billion in the sample. The average size in the low-inefficiency group is higher ($1.4 billion); whereas the average size in the high-inefficiency group is substantially lower ($0.7 billion).

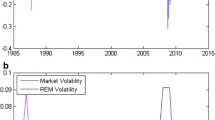

Exhibits 2, 3 and 4 shows average inefficiency across different years and various types of REITs. We first estimate the frontier and firm inefficiency for the full sample of REITs, and then examine any systematic patterns in inefficiency in time-series and cross-sectional variations.Footnote 17

Exhibit 2 indicates that inefficiency of all equity REITs in our sample (including those with and without institutional ownership) seems to reach a peak in 2000, and then decreases over time. Note that time variation in inefficiency can be due to several possible explanations. First, during the bubble period, managers may overinvest in pet projects and hence worsen the inefficiency problem. Second, Standard and Poor’s started to include REITs in its S&P500 index since 2001.Footnote 18 Exposure of REITs in this popular index may prompt greater degrees of public interests on REITs, and also subject these securities to higher external monitoring, which in turn reduces operation inefficiency. Third, after the introduction of Sarbane-Oxeley Act (SOX) in July 2002, firm’s transparency, corporate governance and probably firm inefficiency improves due to compliance to the Act. Therefore, we recognize that other external factors may cause time-series variation in firm inefficiency, but we expect that monitoring from institutional investors should enhance a firm’s efficiency, especially in a cross-sectional setting.

To further examine whether institutional investors continually acquire equity stake for control and monitoring, Exhibit 2 provides the examination of the institutional ownership by different types of institutional investors over time. Total institutional ownerships and ownerships by active institutional investors, and long-term institutional investors increase monotonically—the increases are more than doubled. Further examination (results not reported here) reveals that the most significant increases are investment advisors: 18% to 40.5%. Grey investors (banks and insurance companies) also experience increases but less relative to investment advisors. These findings suggest that institutional investor types that are potentially more effective in monitoring and governance (e.g. long-term, active, and top-five institutional investors, and investment advisors) experience large increases in equity ownerships over time. The increases in equity holdings by effective institutional investors can reflect their continuing monitoring efforts.

Is firm inefficiency related to institutional monitoring? Exhibit 2 suggests that the observed time-variation in firm inefficiency of all REITs may be driven by other factors despite the secular uptrend in institutional ownerships in REITs over time. As such, we shall focus on cross-sectional relationship between inefficiency and institutional ownership, by performing a sub-sample analysis and stratifying the sample into two groups—REITs with high and low institutional ownerships, then compute the significance of the difference in inefficiency over time. If institutional investors provide monitoring role and reduce inefficiency, we expect the inefficiency in REITs with high institutional ownerships to be lower than those with low institutional ownerships. Exhibit 3 presents a clear comparison of the cross-sectional difference in inefficiency for REITs with high vis-à-vis low institutional ownerships over time. REITs with high total institutional ownerships have lower average inefficiency than those with low total institutional ownerships for most years in our sample period between 1997 and 2005 (except for 2003 and 2005). This finding is consistent with the presence of monitoring and governance roles of institution investors. Interestingly, REITs with high long-term institutional ownerships have lower inefficiency than low long-term institutional ownerships for all years from 1998 to 2005. Moreover, the negative difference of average inefficiency between REITs with high institutional ownerships and REITs with low institutional ownerships is larger and statistical significant in years 1997, 1998, 1999, and 2001, the period before the introduction of Sarbane-Oxeley Act in July 2002.

Overall, the results in Exhibits 2 and 3 indicate that institutional investors increase their ownerships over time, yet the lower firm inefficiency associated with high institutional ownerships is more significant in the earlier years of our sample (e.g. from 1997 to 2001). After the introduction of Sarbane-Oxeley Act (SOX) in July 2002, firm’s transparency, corporate governance and probably firm inefficiency improved. As such, the monitoring and governance roles of institutional investors may be subdued due to strengthened firms’ internal control and disclosure requirement [see, e.g. Li et al. (2008), Zhu et al. (2010)].

Exhibit 4 suggests that different types of REITs exhibit similar levels of inefficiency, except for lodging/resort REITs, which has the highest inefficiency of 49.3%. It also suggests that the REITs in the sample are more concentrated in retail (29% of our sample) and industrial/office properties (26% of our sample).

Exhibit 5 provides an in-depth analysis of the five least and most inefficient REITs in our sample. We find that the five least inefficient (or most efficient) REITs from 1997 to 2005 are: VENTAS INC, SAUL CENTERS INC, WASHINGTON REAL ESTATE INVS TR, ALEXANDERS INC, and COUSINS PROPERTIES INC. In contrast, the five most inefficient REITs from 1997 to 2005 are: INCOME OPPORTUNITY REALTY TRUST, KONOVER PROPERTY TRUST INC, ELDERTRUST, AEGIS REALTY INC, and AMREIT INC. These most inefficient REITs all have small market capitalizations. It suggests that small REITs are more exposed to the inefficiency and agency problems. Most prominently, Exhibit 5 shows that institutional ownership is higher for the least inefficient (most efficient) REITs than for the most inefficient REITs. Most strikingly, the five most inefficient REITs all have zero or extremely low institutional equity ownerships during our study period. In contrast, the least inefficient (most efficient) REITs have significant institutional equity ownerships. Hence, this suggests that institutional investors may be able to improve the firm’s efficiency.

Results

In this section, we discuss our empirical results as follows. First, we present results of our main hypothesis and show impacts of different institutional investors on reducing firm inefficiency. Next, we show that institutional investors are able to mitigate inefficiency especially for REITs in financial distress, and for those with higher information asymmetry. Finally, we ask whether inefficiency of certain property types of REITs is more sensitive to institutional ownership.

Do Institutional Investors Mitigate Inefficiency?

Our inefficiency regression result is shown in Exhibits 6 and 7. Panel A investigates if different types of institutional investors can reduce firm inefficiency, while Panel B gives the robustness tests based on the institutional investor types, as reported in Thomson Ownership Database. In Exhibit 6, model 1 tests whether total institutional ownership (io) reduces inefficiency of REITs. We find a significantly negative relation between institutional ownership and inefficiency, confirming our main hypothesis that institutional ownership reduces firm inefficiency. The coefficient of total institutional ownership (io) is −0.034. In terms of economic magnitude of the impact of institutional ownership, one standard deviation in institutional ownership is 33%, and is associated with a decrease of 1.12% (= −0.034*33%) in inefficiency, which in turn can be translated into an increase in market value of 45 million dollars.Footnote 19

Our next task is to examine the effect from different types of institutional investors and investigate whether institutional investors are heterogeneous. Models 2 to 4 suggest that top-five, active and long -term institutional investors are able to mitigate firm inefficiency, whereas short-term investors do not influence firms’ inefficiency. It is consistent with our hypothesis that monitoring incentives determine the effectiveness of monitoring. That is, the effect of monitoring is more pronounced for those institutional investors who have higher incentives to monitor because of their high concentration of ownerships or long length of time invested. In particular, model 2 reveals that top-five institutional investors significantly reduce inefficiency. It implies that due to their concentrated ownerships, these institutional investors are more incentivized to provide direct monitoring, and therefore, enhance firm efficiency. Model 3 indicates that active investors significantly improve inefficiency, consistent with our hypothesis that active investors are more likely to exploit firm-specific or industry-specific information and actively manage their portfolios to pursue positive alphas. Model 4 finds that long-term institutional investors decrease inefficiency, whereas short-term institutional investors do not affect inefficiency. The finding implies that long-term institutional investors may implicitly improve firm efficiency, because managers are more apt to operate more efficiently due to the presence of long-term institutional investors. In contrast, short-term institutional investors have lower incentives to monitor due to short periods of time invested in these assets.

As further exploration and robustness, we test the impacts of heterogeneous institutional investors based on the categorization used by Thomson Ownership Database: i.e. institutional investors are separated into banks, hedge funds, investment advisors, insurance companies, pension funds, investment advisors/hedge funds, and research companies. In Exhibit 7 models 1 to 7, we are interested in the marginal impact of different types of institutions (banks, hedge funds, investment advisors, insurance companies, pension funds, investment advisors/hedge funds, and research companies) on inefficiency, after controlling for the total institutional ownership. The coefficient of each type of institutional investors in models 1 to 7 captures any additional contribution from a particular type of institutional investors in reducing firm inefficiency, and a negative coefficient confirms whether a particular type of investors can reduce inefficiency further (in the presence of total institutional ownerships). Model 3 indicates that investment advisors have a significantly negative coefficient, supporting our hypothesis that independent institutional investors can further reduce inefficiency. In contrast, hedge funds and pension funds both increase inefficiency, as the coefficients between these institutional investors and inefficiency are significantly positive in models 2 and 5. However, we do not find statistically significant impact from banks, insurances, investment advisors/hedge funds, or research companies. Specifically, our results for hedge funds reveal that although conventionally viewed as active institutional investors, hedge funds increase firm inefficiency. The findings for pension funds are consistent with our hypothesis, that pension funds are grey institutions and thus do not provide effective corporate governance effect. Finally, model 8 reveals which type of institutional investors have most significant impact by controlling for all types of institutional investors (including banks, hedge funds, investment advisors, insurance companies, pension funds, investment advisors/hedge funds, and research companies) in the regressions. The result here is consistent with those presented in models 1 to 7, that investment advisors’ equity ownership has the strongest impact in reducing firm inefficiency.

Governance Effect for Firms with Different Characteristics

Is the corporate governance provided by institutional investors more pronounced for firms that are subject to higher inefficiency? Theoretically, firms with higher financial distress, higher information asymmetry, or larger agency cost are more prone to operate inefficiently. We expect institutional monitoring to reduce inefficiency for these firms more significantly. Exhibits 8, 9 and 10 present our findings for sub-samples separated based on three different firm characteristics—financial distress, information asymmetry, and agency cost, respectively. First, we estimate firm inefficiency using the stochastic frontier for full sample of REITs.Footnote 20 Then, in order to examine the intricate relationships between different types of institutional investors and different types of REIT characteristics, we examine the impacts of different types of institutional investors (using total institutional ownership (io), top-five institutional ownership (iofiv), active institutional ownership (ioactive), short-term institutional ownership (iost) and long-term institutional ownership (iolt)) on firm inefficiency based on the sub-samples of these firm characteristics.Footnote 21 We find prevailing evidence that institutional ownership effectively reduces inefficiency particularly for firms that are more prone to suffer from inefficiency.

Exhibit 8 adopts three proxies for financial distress—namely, residual standard deviation, book-to-market ratio, and market capitalization. We use the medians of the proxies to partition the full sample into high- and low- sub-samples. Panel A suggests that firms with higher firm-specific risks (measured by residual standard deviations) are more sensitive to institutional monitoring. In other words, the magnitude of reduction of inefficiency from institutional ownership is larger for firms with higher firm-specific risks. For example, the coefficient of variable io is −0.021 in model 1 for firms with low residual standard deviations, which is significantly lower than the coefficient of −0.042 in model 5 for firms with high residual standard deviations. The same effect is found for top-five and active investors. Consistent with previous finding in Exhibits 6 and 7, short-term institutional investors do not reduce firm inefficiency. Panel B presents results for firms with high versus low book-to-price ratios. Firms with high book-to-price ratios are more subject to financial distress, and we expect institutional ownership to impose a more significant impact on reducing inefficiency for these firms. Results from Panel B confirm our hypothesis. Models 1 and 5 suggest that institutional investors’ equity ownership has no effect on inefficiency for firms with low book-to-price ratios, but it effectively reduces inefficiency for those with high book-to-price ratios. We also show similar effects for active institutional investors’ equity ownership in models 3 and 7. However, contrary to our prediction, long-term institution investors’ equity ownership has no impact for firms with high book-to-price ratios, but has a significant impact for firms with low book-to-price ratio. Finally, model 1 and 5 in Panel C indicates that inefficiency of smaller firms can be successfully reduced by institutional ownership, consistent with our hypothesis. The result holds for active institutional investors, as shown in model 3 and 7. In addition, model 8 suggests that short-term investors further aggravate inefficiency for large REITs.

We further study the impact of institutional ownership on firms with different levels of agency costs. Agency cost prevents firms from operating efficiently and from maximizing their values. Information asymmetry is one source of agency costs. Managers in firms with higher information asymmetry are more inclined to use resources of the firm non-economically due to their advantages on private information. We use shares turnover and whether the firm is followed by financial analysts to proxy for information asymmetry. Lower shares turnover or no analyst coverage implies higher degree of information asymmetry. We expect institutional investors to reduce inefficiency particularly for firms with higher levels of information asymmetry. Exhibit 9 presents our findings. Panel A suggests that the magnitude of reduction in inefficiency is more significant for firms with lower share turnovers. The finding holds for all institutional investors and for active institutional investors. Panel B uses whether the firm is followed by financial analysts as a proxy for information asymmetry, and presents consistent results. Models 1 to 4 reveal that institutional investors improve inefficiency for the sub-sample of REITs that have no analyst coverage. Again, the effect is prevailing for all different types of institutional investors. In contrast, models 5 to 7 suggest that institutional ownership has no influence on inefficiency for REITs that are followed by analysts. It implies that the monitoring role of institutional investors diminishes as firms’ information transparency improves. The finding also suggests that analyst coverage and institutional investors are two important (and possibly substitute) external monitoring agents on improving corporate governance and firm performance.

We also use dividend-to-book ratio to proxy for agency costs. A lower dividend payout ratio potentially creates opportunities for managers to indulge themselves with free cash flows in hands. From Exhibit 1 above, we find that firms with lower payout ratio indeed exhibit higher degrees of inefficiency. Exhibit 10 further reveals that institutional investors are able to reduce inefficiency for both high and low dividend sub-groups. However, the differences in coefficients are not statistically significant. The lack of significant result may be attributable to the regulation that REITs have to pay out at least 90% of their earnings as dividend to shareholders. Hence, dividend payout may not be a perfect proxy for agency cost.

Do institutional investors pay special attention to certain types of real estate properties? We examine this issue from the angle of lease terms of REITs. REITs are composed of real properties with unique characteristics. Some property types have relatively long lease terms (for instance, 7–15 years for some office and retail REITs), whereas the others have very short lease terms (one day for hotels and one year for apartments). We expect institutional investors have higher incentives to monitor REITs with long lease terms, which are more susceptive to high uncertainty and moral hazard problem. We expect active institutional investors with high equity stakes and a long-term orientations to be able to more effectively reduce the moral hazard problem and hence the inefficiency. Exhibit 11 presents evidence supporting our hypothesis. We define residential and lodging/resorts REITs as short-lease-term REITs. We find that short-term REITs are not affected by institutional monitoring, whereas both medium-term and long-term REITs show improved inefficiency from institutional ownership. In addition, short-term institutional investors have no impact on firm efficiency on all sub-samples. It implies that short-term institutional investors are more myopic, and may have no incentive to monitor due to the short investment horizon in the properties. When we test for differences in coefficients across short-term versus long-term leases, we find that the impact for all institutional investors, active and long-term institutional investors are all significantly stronger for long-term vis-à-vis short-term lease sub-samples, and for medium-term vis-à-vis short-term lease sub-samples. Hence, REITs with longer-term leases seem to be most susceptible to the inefficiency problem, and the institutional investors’ corporate governance role seems to be most effective among these REITs.

To sum up, our evidence suggests that institutional investors (particularly, long-term, active, top-five institutional investors, and investment advisors) are more successful in improving efficiency for REITs with long lease terms (such as retail and office REITs), and medium lease terms (such as healthcare REITs). In contrast, inefficiency of REITs with short lease terms such as residential and lodging REITs is not affected by institutional ownership.

Time-Vary Monitoring and Governance Role of Institutional Investors

As noted in Exhibits 2, 3 and 4 institutional ownerships in REITs grow rapidly over time, and there possibly exists time-variations in the monitoring and governance roles of institutional investors. In Exhibit 12, we follow the (Fama and MacBeth 1973) approach, and provide a detailed analysis of the impacts of institutional ownerships on inefficiency for each year in our sample. We estimate a regression for each year in our sample to see whether the impact of institutional ownerships on inefficiency is robust over time, to gain further insights into the time-varying effect (if any) of institutional investor monitoring, and also control for the increasing trend in institutional ownerships over time.Footnote 22

In Exhibit 12, we reported the year-by-year estimated coefficients and t-statistics of different types of institutional ownerships.Footnote 23 Model 1 shows that the regression coefficients of institutional ownerships reduce substantially from −0.014 to −0.002 from 2003 to 2005. Hence, it indicates the governance effect of institutional investors has diminished in and after 2002, when SOX was in place. Our results complements those in Feng et al (2010), where they show that the institutional equity ownership and the top five equity ownership by institutions have significant positive impact on CEO option grant Pay-performance sensitivity for 1998–2002, but not for 2003–2007. This is very similar to the diminished monitoring role of institutional investors reported in Exhibit 12. Feng et al (2010) argue that REIT sector posted double digit growth in market capitalization, many institutional investors were attracted by the superior performance in this market with little interest in monitoring managers.

Interestingly, model 4 of Exhibit 12 shows that long-term institutional investors have significant negative impact (coefficient) on inefficiency in recent years (2004 and 2005). Hence, long-term institutional investors emerge as effective monitors in improving the efficiency of REITs after the SOX of 2002. This result is consistent with Chen et al. (2007) that long-term institutions specialize in monitoring.

Overall, these findings suggest that although institutional investors increase their ownerships during the study period, they might have lost their effectiveness in providing governance, possibly due to reduction in economies of scale, strengthened corporate governance and regulatory environment in the REIT industry in the last decade [Zhu et al. (2010)], and emergence of substitute governance mechanism such as the introduction of SOX since July 2002 that strengthen firms’ internal control and disclosure requirement [see, e.g. Li et al. (2008), Zhu et al. (2010)].Footnote 24 Nevertheless, long-term institutional investors emerge as effective monitor in improving the efficiency of REITs in recent years.

Links and Contributions to Literature

First, our results contribute to existing literature that provides inconclusive evidence on the effect of institutional ownership on target firm value. McConnell and Servaes (1990), Nesbitt (1994), Smith (1996), and Del Guercio and Hawkins (1999), and Gompers and Metrick (2001) find a positive relation between institutional ownership and firm performance. In contrast, Agrawal and Knoeber (1996), Karpoff et al. (1996), Kahn and Winton (1998), (Duggal and Miller 1999), Faccio and Lasfer (2000), and Noe (2002) find no such significant relation. Using REITs as unique natural experiment where information asymmetry and agency cost are higher than those of industry firms, we find strong positive evidence that institutional ownership can enhance REIT values by reducing firm inefficiency and mitigating the moral hazard problem, confirming the monitoring role of institutional investors on improving firm value of REITs.

Second, our results contribute to existing studies in identifying which type(s) of institutional investors are more effective monitors and have better ability to improve firm performances. Institutional investors play different roles in monitoring and governance due to various incentives structures, information, strategies, capabilities, extent of involvements, and control (Brickley et al. 1988; Almazan et al. 2005; Hsu and Koh 2005; Chen et al. 2007). Our results support existing findings that independent institutional investors such as investment advisors (Almazan et al. 2005; Chen et al. 2007; Ferreira and Matos 2008), are in a better position, in terms of tools and motivations, to provide monitoring and exert corporate governance. Our results are also consistent with Chen et al. (2007) that independent institutions with long-term investments will specialize in monitoring. Although Yan and Zhang (2009) find that short-term investors are better informed about a firm’s near-term future perspective and thus short-term institutional investors have better predictability on stock performance than long-term institutional investors, we do find that long-term investor can improve firm performance and efficiency. On the other hand, our results suggest that long-term investors may help firms improve efficiency, while Polk and Sapienza (2009) find that managers cater to short-term investors and only select investments that boost short-run stock prices. Further, our results are consistent with previous studies on shareholder activism by pension funds, mutual funds, and shareholder groups [see Karpoff et al. (1996), Smith (1996), Wahal (1996), Del Guercio and Hawkins (1999), and Parrino et al. (2003)].

Third, while other studies conclude that the presence and holdings of institutional investors and large shareholders in REITs have increased drastically in the post-1990 period (Ling and Ryngaert 1997; Chan et al. 1998), we show the value implications of institutional investors on REITs. While existing literature examines the relation between REIT performance and different governance mechanisms,Footnote 25 we are among the first to document the varying governance roles of different types of institutional investors in REITs. Unlike Hartzell et al. (2006) that does not differentiate among different types of institutional investors, we find that the channel of institutional ownership in affecting REITs corporate governance and performance depends upon the intricate relationship between specific types of institutional investors (such as long-term, independent and active investors) and specific firm-level characteristics and imperfections (such as financial distress, information asymmetry, and lease terms). Our findings complement the recent findings by Feng et al. (2010) that institutional owners do act as monitors in REITs and that governance is necessary for REITs.

Finally, our findings provide further insights and evidence on the time-variation in monitoring role of institutional investors, an important direction that is under-studied by existing literature. We find that the impacts of institutional investors on firm inefficiency lessen over time possibly due to strengthened corporate governance and regulatory environment in the REIT industry over time [Zhu et al (2010)], and emergence of substitute governance mechanism such as the introduction of SOX since July 2002 that strengthens firms’ internal control and disclosure requirement [Li et al. (2008), Zhu et al. (2010)]. Nevertheless, long-term institutional investors emerge as an effective monitor in improving the efficiency of REITs in recent years.

Conclusion

We have recently gone through a series of crises (including the dot.com bubble, the collapse of Enron, and the ongoing 2007–2009 subprime mortgage and global financial crises). Many companies were in financial trouble, and institutional investors became more active in influencing firms for better performance and restoring proper governance. What remains unclear is whether institutional investors and which type(s) of institutional investors can actually help improve governance and create firm value. Given that REITs are subject to corporate governance problem and that institutional investors have dramatically increased their investments in REITs, our study investigates these important issues in the context of REITs.

Prior research on REIT efficiency has focused solely on cost inefficiency. Using a stochastic frontier approach, this study examines governance role of institutional investors in improving firm inefficiency. Overall, our findings convey a clear message—institutional ownership can reduce firm inefficiency, and the effect is stronger for active, top-five, and long-term institutional investors. These institutional investors have strong incentives to improve corporate governance due to their higher equity stakes or their longer investment horizon. Meanwhile, short-term institutional investors have no impact on firm inefficiency, implying that short-term investors are myopic and probably have no incentive to monitor firm governance. In addition, we observe that investment advisors can reduce the inefficiency problem, whereas hedge funds and pension funds worsen the problem. Investment advisors are conventionally considered as independent institutions, so it is not surprising to find that they provide better governance effect than other investors. In contrast, pensions funds are conventionally considered as ‘grey institutions’, because they are more likely to have business ties with the invested companies. We provide evidence that pension funds indeed aggravate the inefficiency problem.

Second, robustness check also reveals that the governance effect from institutional investors is stronger for firms that are more subject to inefficiency problem. Specifically, we report that institutional investors can improve inefficiency more effectively for the sub-samples of distressed REITs, and of REITs with higher degree of information asymmetry.

Third, we study the institution investors’ governance effect on different property types in terms of their lease terms. Our evidence indicates that institutional investors can mitigate the inefficiency problem for REITs with relatively longer lease terms (such as retail, office, and healthcare REITs), but not for short-term REITs (such as residential and lodging REITs). We attribute this finding to the ability of institutional investors in mitigating the moral hazard problem. Due to their long-term horizons and corporate governance skills, institutional investors are more specialized and effective in improving the efficiency of REITs with longer-term leases, which are more susceptive to high uncertainty and the moral hazard problem.

Lastly, we provide evidence on the time-variation in monitoring role of institutional investors. We find that despite of the fast growth of the institutional ownership over time, the impacts of total, active, and top-five institutional investors on firm inefficiency lessen over time, possibly due to strengthened corporate governance and regulatory environment in the REIT industry in later years. Nevertheless, long-term institutional investors emerge as effective monitor in improving the efficiency of REITs in recent years.

Notes

Francis, J, T. Lys, and L. Vincent. Valuation Effects of Debt and Equity Offerings by Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs). Working Paper, Duke University.

See New York Times, “New Stocks, Same Old Problems” by Gretchen Moregenson, Jan 23, 2005.

See New York Times, “Commercial Property; Reckson Is Narrowing Its Focus to Office Buildings” by John Holusha, Dec 7, 2003.

The “five or fewer” rule requires REITs to have at least 100 shareholders, and no more than 50% of a REIT’s share can be owned by five or fewer shareholders.

See, for examples, the Wall Street Journal articles by Brian Kalish, Dec 31, 2008 and Robin Sidel, Apr 13, 2001.