Abstract

This study investigated the development of automatic word recognition processes, in particular the development of the morphological level of processing. We examined masked priming of Hebrew irregular forms at two levels of reading experience. Both third- and seventh-grade children showed morphological priming for defective roots when primes and targets conformed to the canonical morphological structure, containing all three letters of the roots, and also when the surface form of the primes and targets contained only two of the root letters. However, priming was not observed when primes and targets did not overlap in the surface form of the roots, i.e. the full three-letter root as prime and only two root letters in the target. These results suggest that both tri- and bi-consonantal representations of defective roots exist in the mental lexicon of young readers. The formation of interconnections between these allomorphic representations, however, requires more extensive reading experience.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Research on the linguistic knowledge of young children has focused on the ability of children to identify and manipulate sub-word morphemic units. This morphological knowledge, demonstrated in both oral and visual tasks, is acquired early and continues to develop throughout the years of elementary school (for a review, see Anglin, 1993). Research conducted in Hebrew also demonstrates that preschool children exhibit the ability to extract the root, the basic morphemic component of Hebrew, from words and use it to make up new words as early as at age two (Berman, 2000; Clark & Berman, 1984; Ravid, 2002). Such findings indicate an early and robust perception of the Semitic root in Hebrew-speaking children (Berman, 2002; Ravid, 2002; Ravid & Schiff, 2006).

Studies of morphological knowledge of children that focus specifically on the perception of written language indicate that children’s performance in these tasks is highly related to their reading ability (e.g., Bradley & Bryant, 1985; Carlisle, 1995; Elbro & Arnbak, 1996; Levin, Ravid, & Rapapport, 2001; Liberman, 1987; Mann, 1991; Singson, Mahony, & Mann, 2000). However, these tasks tap into an aspect of linguistic ability that specifically requires conscious analysis of linguistic forms: For example, to consciously extract a morpheme and construct another morphologically complex word (e.g., Complete the sentence: My uncle is a _____ (farm)) or to judge morphological relationships (e.g., Are the words kind-kindness related?). Unconscious, automatic lexical processing should also be investigated in order to fully understand the linguistic processing of printed words. The present research examines the on-line automatic visual word recognition processes of young readers to learn how the word recognition process and the structure of the mental lexicon develop as children gain increasingly more experience with printed words.

An important experimental paradigm for examining automatic word recognition processes is the priming paradigm. Priming refers to the facilitation in response time and accuracy when the same or a related word has been encountered previously in the experimental session (e.g., Forster & Davis, 1984; Scarborough, Cortese, & Scarborough, 1977). A growing body of psycholinguistic research has demonstrated the importance of using the priming effect as a tool for investigating the organization of the adult mental lexicon.

The priming paradigm has also proved to be a useful tool for investigating word recognition processes in developing readers. Recent studies demonstrated that robust priming effects can be found in children as young as seven years old and that the characteristics of these effects are modulated developmentally (for a review see Castles, Davis, & Forster, 2003). Generally, studies manipulated the relationship between the prime and the target words in order to examine different levels of processing: Phonological and orthographic (e.g., Castles, Davis, & Letcher, 1999; Davis, Castles, & Iakovidis, 1998; Kaminska, 2003), semantic (e.g., Nation & Snowling, 1999; Plaut & Booth, 2000) and syntactic (e.g., Huttenlocher, Vasilyeva, & Shimpi, 2004) levels. Very little developmental research, however, has been devoted to morphological priming effects.

Evidence from a variety of tasks and languages demonstrates that skilled adult readers are sensitive to the morphological structure of the words they read (see Deutsch & Frost, 2003; Feldman, 1994; Henderson, 1985; Stolz & Feldman, 1995; Taft, 1985 for reviews). Priming studies (see Feldman, 1994 for review) show that target identification is enhanced in both response time and accuracy when preceded by a morphologically related word (e.g., scanner-scan). Since morphologically related words are typically related by both form (orthography and phonology) and meaning, it should be stressed that, under the same priming conditions, morphologically unrelated primes that are only orthographically or semantically similar to the target have little or no effect on the identification of the target (Bentin & Feldman, 1990; Drews & Zwitserlood, 1995; Feldman, 2000; Napps, 1989).

This facilitation effect, termed “morphological priming,” suggests that skilled readers decompose words into their constituent morphemes before accessing their meaning (Chialant & Caramazza, 1995; Frost, Forster, & Deutsch, 1997; Rastle, Davis, Marslen-Wilson, & Tyler, 2000; Schreuder & Baayen, 1995; Stanners, Neiser, Hernon, & Hall, 1979). Morphological priming is thought to reflect a transfer effect; i.e. the information related to the shared base morpheme is extracted from the prime and is transferred to the processing of the target.

Morphological priming is thus regarded as evidence that the mental lexicon of skilled readers is organized by morphological principles (Deutsch & Frost, 2003; Schreuder & Baayen, 1995). However, since morphological priming tests have been conducted mostly with adult readers, much less is known about how this morphological organization develops. To the best of our knowledge, only two recent studies have examined morphological priming in elementary school children. Feldman, Rueckl, DiLiberto, Pastizzo and Vellutino (2002) found morphological priming effects in fifth-grade English-speaking children. Using the word fragment completion task, phonologically transparent (e.g., turned) as well as phonologically opaque morphological relatives (e.g., ridden) primed their base morpheme (e.g., turn and ride, respectively). Raveh and Yamin (2005) examined Hebrew-speaking second, third- and fifth-graders using both a word fragment and cross-modal priming tasks. Even second graders showed strong morphological priming when the prime and the target words shared a root, the basic Hebrew morpheme. These results suggest that young readers have knowledge of the morphological structure of words they read. Young readers, similarly to adult readers, parse both regular and irregular word forms into their component morphemes and use these morphemes to access the mental lexicon.

In the present study, we examined further the morphological processing of young readers using morphologically irregular Hebrew forms. The rationale for using these forms was that the challenge posed by these forms to the parsing mechanism may reveal more about the function and development of this mechanism.

In Semitic languages, such as Hebrew and Arabic, words are most commonly formed by a nonlinear combination of two basic morphemes, a root and a word pattern. The root, usually consisting of three consonants (e.g., G-D-L), reflects the core meaning shared by all the words formed from the root. The word pattern, consisting of both vowels and consonants, serves as the phonological word pattern and often carries both semantic and morpho-syntactic information (Berman, 1987; Ravid, 1996; Schwarzwald, 2001). The root and the word pattern are abstract units and only when interdigitated do they form a word. Unlike word components in English, in Hebrew the basic morphemes are not sequentially ordered (non-concatenative). Rather, roots are interdigitated within word patterns: e.g., the root G-D-L conveying the core meaning of “grow” and the word pattern CaCoC combine to yield the adjective GaDoL “big”. (For purposes of exposition, the root is presented in uppercase letters and the word pattern in lowercase letters in both the latter and the following examples, in order to facilitate distinguishing between the two morphemes).

Despite this structural complexity, Hebrew readers automatically extract the root from regular Hebrew words (e.g., Frost et al., 1997; for a review see Deutsch & Frost, 2003). Frost, Deutsch and Forster (2000) have argued that the main clue to the decomposition of the root is its typical tri-consonantal structure, since the same three letters appear consistently in all the words constructed from it. This orthographic consistency may serve as a stable anchor for the parsing mechanism.

Irregular forms in Hebrew, called weak roots, do not conform to this conventional tri-consonantal structure norm. Approximately 10% of all Hebrew words are derivations from weak roots and many are high frequency words (Frost et al., 2000). Typically, one of the three root consonants may disappear in some or in all of their derivations in both the spoken and the written form of weak roots. In one class of weak roots, the defective roots, the irregular root consonant is the initial radical n. When this radical has a zero vowel (quiescent schwa), it disappears and fully assimilates into the next consonant (Berman, 1987; Schwarzwald, 2001). Hebrew contains about 70 such defective roots that combine with both verbal and nominal word patterns to form common and frequently used words. In the verbal system, this phenomenon occurs in four of the seven Hebrew verbal word patterns. (In the other three patterns, the initial consonant does not disappear because it has a vowel in all of the inflections.) In the nominal system, this phenomenon occurs in several commonly used word patterns. For example, the defective root N-G-V conveys the core meaning of “wiping” and forms several semantically related words. In some derivations, all three root letters appear; NiGuV “wiping,” leNaGeV “to wipe,” lehitNaGeV “to wipe oneself;” in other derivations, only two root letters (G and V) appear; maGeVet “towel” and maGaV “wiper”.

The absence of the first root consonant creates inconsistency in the morphological system, for example, the verb in its typically appears with the full root (e.g., /NaFaL/ “he fell”), whereas the future tense lacks the initial consonant (e.g., /yPoL/ “he will fall”, where the initial root letter N is missing). There are several defective roots that generally appear in forms that do not contain the initial consonant. However, for the current study, we used only defective roots that appear in their full form in some words and in their missing form in other words. It is important to note that due to the inherent characteristics of the Hebrew morphological system, the frequency of the words with the full form of the root is approximately equal to the frequency of the words with the missing form.

The inconsistency with which one root consonant appears in the surface form makes decomposing the word more complex. As characterized by Frost et al. (2000), if the morphological parser, which needs to separate the two morphemes (root and word pattern), makes a default assignment of three letters to the root based on the structural norm in Hebrew morphology, there would be one letter missing for the word pattern. If all the correct consonants are assigned to the word pattern morpheme, there would be only two consonants left for the root. Thus, the examination of the morphological priming of these forms may show how factors like orthographic consistency affect morphological processing.

In this context, several questions are raised regarding the morphological processing of the class of defective roots. The basic question is whether despite their inconsistency, the irregular forms derived from defective roots undergo morphological decomposition during their recognition process. More specific questions relate to the nature of their morphemic representations: Are defective roots represented as the canonical tri-consonant units, as bi-consonant units, or both?

Using the masked priming paradigm to investigate the morphemic representations of defective roots, Velan, Frost, Deutsch and Plaut (2005) addressed these questions in adults. The two root letters of the defective roots primed target words derived from these roots (e.g., GV primed maGeVet “towel”), suggesting that these two letters do gain a morphemic status, perhaps because they consistently appear in the surface form of many words. In addition, the full three letters of the defective root primed target words derived from these roots, even when the first root letter was missing in the surface form of the target (e.g., NGV primed maGeVet “towel”). Based on their results with adults, Velan et al. suggest that defective roots have allomorphic bi-consonantal and tri-consonantal representations in the mental lexicon, and both mediate the recognition of words derived from defective roots.

Similar findings were also found with adult Arabic speakers. Boudelaa and Marslen-Wilson (2004) demonstrated morphological priming for word pairs that shared a root morpheme, both when the root surfaced fully in these words and when the prime and target words contained different surface variants of the root.

Given the orthographic inconsistency of the class of defective roots, the current study examines the processing of these irregular forms in young readers. Does the mental lexicon of children with relatively little exposure to the written language contain morphemic representations for defective roots? If it does, what is the nature of these representations and how do they change as the linguistic knowledge of the children develops? The importance of these questions extends beyond the processing of this class of irregular words. Examining how children process these morphologically irregular Hebrew forms may provide insight into principles governing the development of the word recognition system, and in particular the generation of morphemic representations and organization.

We compare morphological priming effects for defective roots in third-grade children who have just mastered the grapho-phonemic code and seventh-grade children who have accumulated experience with written language. Any differential effects of morphological priming of children at two different grade levels (early and late elementary school), or between the children’s performance and that of adults, may reflect the cumulative effects of schooling and print exposure on the development of automatic word recognition procedures and organization of the mental lexicon.

Experiment 1

Experiment 1 examined whether children show morphological priming for words derived from irregular Hebrew roots that belong to the class of defective roots. Morphological priming effects were assessed using the masked priming paradigm (Forster & Davis, 1984) that has been used extensively in morphological priming studies (e.g., Boudelaa & Marslen-Wilson, 2004; Frost et al., 1997; Grainger, Cole, & Segui, 1991). The advantage of using this paradigm is that the primes are presented only briefly (50–60 ms) so that the participants are not aware of prime presentation. This eliminates any influence from post-perceptual processes, such as conscious consideration of the prime-target relationship (Forster, Mohan, & Hector, 2003).

Another important advantage is that while the masked priming paradigm has been shown to be highly sensitive to overlap in form between the prime and target words (e.g., Forster, Davis, Shoknecht, & Carter, 1987; Forster & Taft, 1994), it is relatively insensitive to semantic overlap (e.g., Frost et al., 1997; Frost et al., 2000). This semantic insensitivity is critical when measuring morphological priming effects. Given that morphologically related words are typically highly related in meaning, this feature of the task ensures that the priming measured is due to the morphological relationship between the primes and targets rather than to a simple semantic relationship.

Given that morphologically related words are also highly related in form, i.e. share many letters, it is important to control for this form overlap between the prime and target words. Because the masked priming paradigm is sensitive to orthographic overlap (see Forster, 1987, for a review), the priming between morphologically related words may reflect the joint effects of both orthographic and morphological similarity. In the present research, as in many other studies using the masked priming paradigm in a variety of languages (e.g., Arabic: Boudelaa & Marslen-Wilson, 2004; Hebrew: Frost et al., 1997; French: Grainger, Cole, & Segui, 1991; English: Rastle et al., 2000), morphological priming is measured by comparing response latencies in the morphologically related condition with an orthographic baseline condition having the same of orthographic overlap as targets. Any effect found in the morphological condition can thus be regarded as indicating the additional and unique contribution of morphological factors over and above simple orthographic effects.

The target words used in Experiment 1 were the most transparent cases within the class of defective roots, conforming to the canonical structure of Hebrew words containing all three letters of the root and similar to words derived from regular roots. These target words were preceded by morphologically related primes consisting of the three root letters. Morphological priming was defined as the facilitation of target naming following the three root letters relative to an orthographic baseline condition in which the target words were preceded by an orthographically related prime consisting of three letters that were not all root letters. An identity priming condition was also included, where the primes are identical to the targets, as a baseline measure of the maximal possible priming possible. Finally, in contrast to Velan et al. (2005), our measure of priming was based on naming latencies, since this is a more natural task for young readers.

Method

Participants

Sixty children participated in this experiment, 30 third-graders and 30 seventh-graders. All were native Hebrew speakers with no reported signs of sensory, neurological or attention deficits. These children were defined as good readers based on their performance in de-contextualized word and non-word reading tests (Deutsch & Bentin, 1996). The tests consisted of 24 meaningful words and 24 non-words. Both words and non-words were short, 2 syllable sequences, 3–4 letters long. All the Hebrew consonants and vowels were represented in these lists. The word patterns used are frequent forms in Hebrew. The non-word list consisted of the same word patterns as the word list but with non-existent roots. The meaningful words had a relatively simple morphological structure and were relatively frequent in the language of young children.

Only children who scored at least 84% in these tests were included in this study. The rationale for this selection was based on studies indicating that morphological processing and decoding ability are interrelated (Carlisle, 1995; Elbro & Arnbak, 1996; Schiff, 2003; Shimorn & Vaknin, 2005; Singson, Mahony, & Mann, 2000). Thus, we used a simple decoding test to select only children that had acquired the basic decoding skills expected by third-grade (actually, they are expected already at the end of first grade in Hebrew readers). Such a basic selection criterion minimizes possible confounding between morphological processing and reading ability. We ensured that when morphological priming was not found, this failure could not be attributed to decoding difficulty but rather that it is specific to processing at the morphological level. Children with an error rate exceeding 16% in each of the word and non-word lists (i.e., 4 or more errors in each list) were considered “good” readers who have mastered basic decoding skills, a criterion generally accepted in studies conducted in Hebrew in which no reading norms are yet available (e.g., Deutsch & Bentin, 1996). It is important to stress that the reading test was not directed to targeting an exceptionally good reading skill, but rather a good basic decoding skill.

Design and materials

Priming condition (identity, morphological, orthographic) was manipulated as a within-subjects variable and grade (third, seventh) as a between-subjects variable. Naming response time and accuracy was the dependent variable.

The stimuli of this and the following experiments were based on Velan et al. (2005). They consisted of 36 target words, four to six letters long, two or three syllables and five to eight phonemes. They had a mean of 4.6 letters and a mean of 5.9 phonemes. The mean frequency of the target words was 4.10, based on frequency ratings (on a scale from 1—infrequent word in young children’s language to 5—very frequent) gathered from a group of 30 teachers with an academic background in language development and education. The target words were derived from defective roots, but contained all three letters of the root. To create the three priming conditions, the target words were paired with 36 sets of three primes each: a word identical to the target for the identity priming condition, the three root letters of the target for the morphological priming condition and a string of three letters contained in the target which were not the three letters of the root (two root letters and a third non-root letter) for the orthographic baseline condition. Thus, the morphologically related and the orthographic baseline primes shared the same number of letters with the target. Furthermore, whenever possible we equated the similarity of the first phoneme of the two primes to the target. In some pairs of primes, on the list, morphological but not orthographic primes shared the initial phoneme with the target, whereas in others the orthographic but not the morphological primes shared initial phoneme with the target. In the remaining pairs, the morphological and baseline primes shared an initial phoneme or both did not share an initial phoneme with the target.

All stimuli in this and the following experiments appeared in the unvowelized Hebrew script. Both third- and seventh-grade students, like adult readers, are used to reading unvowelized Hebrew texts. Vowelized script is mostly used in biblical texts and poetry. The stimuli were counterbalanced across participants such that participants did not see any prime or target more than once. An example of a set of stimuli is presented in Table 1.

Procedure

Participants were tested individually in a quiet room sitting 60 cm from the screen of a laptop computer. Each trial consisted of the following sequence of events presented in the center of the screen: a mask consisting of eight hash marks (########) was presented for 500 ms, the prime for 50 ms, and the target word was presented until the voice key was activated by the participants’ naming response. Presentation and response recording were controlled through DMDX software (Forster & Forster, 2003) run on an IBM laptop. The participants were instructed to read the words they saw as quickly and as accurately as possible into the microphone. The experiment started with four practice trials followed by 36 experimental trials. Naming response times were measured from target onset to voice key activation. Accuracy was scored by two judges based on the recordings of the participants’ oral responses.

Results and discussion

Incorrect responses and responses that were more than two standard deviations from the mean were excluded from the response time analysis of this and the following experiments. The overall mean accuracy rate was 0.79 in the third-grade and 0.88 in the seventh-grade. The data from six participants (four third- and two seventh-graders) were excluded from the analyses because of accuracy rates lower than 65%.

Response times

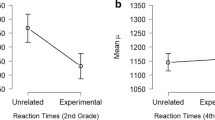

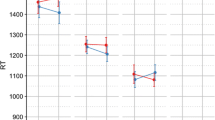

The mean response times for the different priming conditions are presented in Table 2. Response times varied as a function of the priming condition and were fastest in the identity priming condition, followed by the morphological priming condition, and then the orthographic baseline condition. The response times of the third-graders were consistently longer than those of the seventh-graders.

An ANOVA with priming condition (identity, morphological, orthographic) as a within-subjects and grade (third, seventh) as a between-subjects variable revealed an effect of priming condition both by subjects, F1(2,104) = 27.20, MSE = 4319, p < .001, and by items, F2(2,140) = 17.83, MSE = 8482, p < .001. The effect of grade approached significance by subjects, F1(1,52) = 3.17, MSE = 84754, p = .081, and was significant by items, F2(1,70) = 33.55, MSE = 8795, p < .001. The interaction between priming condition and grade was not significant. In planned comparisons (Bonferroni), both the identity condition and the morphological priming condition were significantly different from the orthographic baseline condition in both subjects and items analyses (p < .05). Thus, both the identity and morphological priming effects were significant.

To further examine whether the magnitude of the priming effects differed between grades, we first compared the response times in the orthographic baseline conditions of the two grades. Planned comparison (Bonferroni) revealed that this baseline condition was faster in the seventh-grade in both the subjects and the items analyses (p < .05). Given that the stimuli were written words, these baseline differences are not surprising, since seventh graders are expected to demonstrate faster and more automatic decoding skills. It is well known that baseline performance differences can pose problems when comparing subject groups (Cermak, Talbot, Chandler, & Wolbarst, 1985; Cermak, Verfaellie, Milberg, & Letourneau, 1991; Chapman, Chapman, Curran, & Miller, 1994; Ellis & Young, 1988, p. 284; Loftus, 1985; Snodgrass, 1989). If one group initially performs slower than the other, it may be easier for the slower group to improve (i.e., exhibit a greater priming effect) than the group that initially performs faster. This effect artificially inflates the priming effects. In order to test the effect of grade specifically on morphological processing, we must therefore first control for this difference in decoding latencies.

Given the differences in baseline naming response times in this experiment, we re-analyzed our data by entering a relative measure of the magnitude of the priming effects as the dependent variables in the ANOVA. The relative measure is the proportion of the facilitation in response latency from the baseline response latency, and is computed by taking the difference in response time between the priming condition (identity or morphological) and the orthographic baseline condition and then dividing by the orthographic baseline response time. This measure reflects the magnitude of the priming effects relative to the baseline latency of word identification in each grade. A repeated measures ANOVA of the relative priming effects with priming condition (identity, morphological) as a within-subjects and grade (third, seventh) as a between-subjects variables revealed that the identity priming effect was stronger than the morphological priming effect, F1(1,52) = 19.41, MSE = 36.98, p < .001; F2(1,70) = 11.92, MSE = 92.16, p < .001. There was no difference in the magnitude of the priming effects between the two grades and no interaction between priming condition and grade. Thus, the relative measure shows that identity priming was stronger than morphological priming for both grades. Importantly, when baseline differences between the two grades were neutralized, the magnitude of the priming effects was comparable in the third and seventh grade.

Finally, one possible concern is that the results may be affected by the frequency of the items. We therefore excluded 3 target words that received low ratings (below 3.5) based on the frequency ratings of the target words. These items were also those that demonstrated the lowest accuracy rates in the naming task. The re-analysis of the priming data without those items did not differ from the original results. An ANOVA with priming condition (identity, morphological, orthographic) as a within-subjects and grade (third, seventh) as a between-subjects variable revealed an effect of priming condition, F2(2,128) = 16.97, MSE = 7983, p < .001, and an effect of grade F2(1,64) = 48.99, MSE = 7569, p < .001. The interaction between priming condition and grade was not significant. In planned comparisons (Bonferroni), both the identity condition and the morphological priming condition were significantly different from the orthographic baseline condition (p < .05). Thus, both the identity and morphological priming effects were significant.

Accuracy rates

The accuracy rates in each priming condition are presented in Table 2. The analysis of the accuracy rates did not reveal any priming effect. An ANOVA with priming condition (identity, morphological, orthographic) as a within-subjects and grade (third, seventh) as a between-subjects variable revealed only a significant effect of grade and only by subjects, F1(1,52) = 16.68, MSE = 0.021, p < .001, indicating that third-graders made more errors than seventh-graders. Due to the absence of priming effects, we did not analyze the accuracy rate further.

The response-time results of Experiment 1 clearly show that children demonstrate morphological priming for words belonging to the irregular class of defective roots as early as the third-grade: The three root letters primed their derivations. After neutralizing baseline differences in response times between the grades, we saw that identity priming was stronger than morphological priming in both grades. Furthermore, the magnitude of priming was comparable in the two grades. The morphological priming effect replicates the priming found for defective roots in adults (Velan et al., 2005) and is comparable to the priming obtained in children for morphologically regular words in Hebrew (Raveh & Yamin, 2005). The priming effect suggests that a tri-consonantal root representation has been established in the mental lexicon of young readers despite the inconsistent orthographic appearance of the root, i.e. the three root letters appearing in some derivations but not in others.

Experiment 2

The morphological priming found in Experiment 1 may have resulted from the target words conforming to the regular tri-consonantal structure of Hebrew words, although derived from defective roots. Hence, the children could treat these words like regular words. We tested this possibility using target words derived from defective roots that violate the regular tri-consonantal structure; targets in which the initial radical n (“nun”) of the root was omitted, leaving only two root letters. Morphological priming was measured using the full form of the root as primes, i.e. the three root letters. The primes in this experiment were thus identical to the primes used in Experiment 1.

Method

Participants

A different group of sixty children participated in this experiment, 30 third-graders and 30 seventh-graders. They were selected according to the criteria specified in Experiment 1.

Design and materials

The stimuli consisted of 36 target words, three to six letters long, with two or three syllables and five to seven phonemes. They had a mean of 4.1 letters and a mean of 5.5 phonemes. The mean frequency ratings of the target words in Experiment 1 and 2 were compared and found to be statistically equivalent (4.10, 4.08, respectively, p > .05).

The target words were derived from defective roots. However, in contrast to Experiment 1, they were defective forms of these roots, i.e. with the first letter of the root missing. Each target word therefore contained only two letters of the root. Similarly to Experiment 1, these target words were paired with 36 sets of three primes each in order to create the three priming conditions: a word identical to the target for the identity priming condition, the tri-consonantal root of the target for the morphological priming condition, and a string of three letters contained in the target which were not the three letters of the root (two root letters and a third non-root letter) for the orthographic baseline condition. The morphological and orthographic baseline primes were identical to those used in Experiment 1. (See Table 1 for an example of a Hebrew set) The design and procedure of this experiment were identical to those of Experiment 1.

Results and discussion

The overall mean accuracy rate was 0.78 in the third-grade and 0.89 in the seventh-grade. The data from three third-grade participants were excluded from the analyses because of an accuracy rate lower than 0.65.

Response times

The mean response times for the different priming conditions are presented in Table 3. Response times varied as a function of the priming condition and were fastest in the identity priming condition, followed by the morphological priming condition, and then the orthographic baseline condition. The response times of the third-graders were consistently longer than those of the seventh-graders.

An ANOVA with priming condition (identity, morphological, orthographic) as a within-subjects and grade (third, seventh) as a between-subjects variables revealed an effect of priming condition both by subjects, F1(2,110) = 37.01, MSE = 3496, p < .001, and by items, F2(2,140) = 19.86, MSE = 8023, p < .001. The effect of grade was significant by subjects, F1(1,55) = 61.93, MSE = 52485, p < .001, and significant by items, F2(1,70) = 343.76, MSE = 10288, p < .001, indicating that seventh-graders were consistently faster than the third-graders. The interaction between priming condition and grade was not significant. In planned comparisons (Bonferroni), the identity condition was significantly different from the orthographic baseline condition in both subjects and items analyses (p < .05). In contrast, the morphological priming condition did not differ from the orthographic baseline condition. Thus, the identity priming effect was significant but, in contrast to Experiment 1, no morphological priming was observed in this experiment.

As in Experiment 1, because there were significant baseline differences in response times between the two grades (Bonferroni, p < .05), we re-analyzed the data using priming effects in proportional terms. A repeated measures ANOVA of the relative priming effects with priming condition (identity, morphological) as a within-subjects and grade (third, seventh) as a between-subjects variables revealed that the identity priming effect was stronger than the morphological priming effect, F1(1,55) = 58.64, MSE = 34.94, p < .001; F2(1,70) = 30.30, MSE = 101.57, p < .001. There was no difference in the magnitude of the priming effects between the two grades and no interaction between priming condition and grade. Thus, the analysis of the relative priming effects demonstrates that identity priming was stronger than morphological priming. Importantly, when the baseline differences between the two grades were neutralized, the magnitude of the priming effects was comparable in the third and seventh grade.

Finally, as in Experiment 1, we re-analyzed the data excluding 4 items that were rated as relatively infrequent in children’s language and demonstrated low accuracy rates in the naming task. The results were similar to the original results. An ANOVA with priming condition (identity, morphological, orthographic) as a within-subjects and grade (third, seventh) as a between-subjects variable revealed an effect of priming condition, F2(2,124) = 15.88, MSE = 7779, p < .001, and an effect of grade F2(1,62) = 464.66, MSE = 6847, p < .001. The interaction between priming condition and grade was not significant. As in the original results, only the identity condition was significantly different from the orthographic baseline condition (Bonferroni, p < .05).

Accuracy rates

The accuracy rates in each priming condition are presented in Table 3. An ANOVA on the accuracy rates with priming condition (identity, morphological, orthographic) as a within-subjects and grade (third, seventh) as a between-subjects variables revealed a significant effect of priming condition, but only in the analysis by subjects, F1(2,110) = 4.62, MSE = 0.0005, p < .05. There was a significant effect of grade by both subjects and items, F1(1,55) = 11.39, MSE = 0.043, p < .001; F2(1,70) = 21.98, MSE = 0.006, p < .001, indicating that third-graders made more errors than seventh-grade children, and an interaction between prime and grade by subjects, F1(2,110) = 4.62, MSE = 0.00005, p < .05. The third-graders, but not the seventh-graders, made fewer errors in the identity condition relative to the orthographic baseline condition (Bonferroni, p < .05), indicating an effect of identity priming in this grade only.

The pattern of results was similar for third- and seventh-graders. In both, as in Experiment 1, the response-time data show, that identity priming was stronger than morphological priming. However, in contrast to Experiment 1, no morphological priming was found for both third- and seventh-grade children. When the targets did not conform to the regular tri-consonantal structure of Hebrew words, no priming was obtained from the three root letters. These results contrast with the findings from adults, where three root letters of defective roots facilitated the recognition of targets derived from them, even though one letter was missing in the targets (Velan et al., 2005, Experiment 5). These contrasts will be discussed below.

Experiment 3

In Experiment 2 there was no priming from the three root letters when the targets contained only two of the root letters. Now we tested whether a target in defective form can benefit from the prior presentation of a prime consisting of the two root letters which are repeated in all the root derivations. Such a priming effect was found by Velan et al. (2005) with adult skilled readers, suggesting that the two root letters acquire a special morphological status perhaps due to their consistent appearance in the surface orthography. The question addressed in Experiment 3 was whether the two root letters of defective roots similarly have a morphological status in the mental lexicon of young readers.

Method

Participants

A different group of sixty children participated in this experiment, 30 third-graders and 30 seventh-graders. They were selected according to the criteria specified in Experiment 1.

Design and materials

The target words were identical to those used in Experiment 2. The target words were defective forms of roots with the first letter of the root missing. These target words were paired with 36 sets of three primes each in order to create the three priming conditions: a word identical to the target for the identity priming condition, the two root letters contained in the target and repeated in all words derived from that root for the morphological priming condition and a string of two letters contained in the target that were not the root of the target for the orthographic baseline condition. An example of a Hebrew set is presented in Table 1. The design and procedure of this experiment were identical to those of the previous experiments.

Results and discussion

The overall mean accuracy rate was 0.77 in the third-grade and 0.87 in the seventh-grade. The data from five participants (four third-graders and one seventh-grader) were excluded from the analyses because of accuracy rates lower than 0.65.

Response times

The mean response times for the different priming conditions are presented in Table 4. Response times varied as a function of the priming condition and were fastest in the identity priming condition, followed by the morphological priming condition and then the orthographic baseline condition. Response times of the third-graders were consistently longer than those of the seventh-graders.

An ANOVA with priming condition (identity, morphological, orthographic) as a within-subjects and grade (third, seventh) as a between-subjects variable revealed an effect of priming condition both by subjects, F1(2,106) = 22.63, MSE = 4590, p < .001, and by items, F2(2,140) = 12.42, MSE = 13569, p < .001. The effect of grade was significant by subjects, F1(1,53) = 8.65, MSE = 96763, p < .01, and by items F2(1,70) = 104.15, MSE = 11067, p < .001. The interaction between priming condition and grade was significant only by subjects, F1(2,106) = 5.70, MSE = 4590, p < .01. Planned comparisons (Bonferroni) revealed that all priming effects were significant (p < .05) for both grades. However, the interaction stems from the fact that the identity priming condition was faster than the morphological priming condition, but only in the third-grade. In the seventh-grade, the two priming conditions did not differ from each other.

As in the previous experiments, because there were significant baseline differences in response times between the two grades (Bonferroni, p < .05), we re-analyzed the data using priming effects in proportional terms. A repeated measures ANOVA of the relative priming effects with priming condition (identity, morphological) as a within-subjects and grade (third, seventh) as a between-subjects variables revealed that the identity priming effect was stronger than the morphological priming effect, F1(1,53) = 10.92, MSE = 59.19, p < .01; F2(1,70) = 4.93, MSE = 159.9, p < .05. There was no difference in the magnitude of the priming effects between the two grades. There was an interaction between priming and grade reflecting that the difference between identity and morphological priming was greater in the third-grade than in the seventh-grade, but only in the analysis by subjects, F1(1,53) = 4.99, MSE = 59.19, p < .05. Thus, identity priming was stronger than morphological priming (more so in the third-grade). Furthermore, when the baseline differences between the two grades were neutralized, the magnitude of the priming effects was comparable in the third and seventh grade.

Finally, as in the previous experiment, we re-analyzed the data excluding 4 items that were rated as relatively infrequent in children’s language and demonstrated low accuracy rates in the naming task. The results were similar to the original results. An ANOVA with priming condition (identity, morphological, orthographic) as a within-subjects and grade (third, seventh) as a between-subjects variable revealed an effect of priming condition, F2(2,124) = 12.63, MSE = 11932, p < .001, and an effect of grade F2(1,62) = 100.66, MSE = 10602, p < .001. The interaction between priming condition and grade was not significant. As in the original results, planned comparisons (Bonferroni) revealed that all priming effects were significant (p < .05) for both grades.

Accuracy rates

The accuracy rates in each priming condition are presented in Table 4. An ANOVA on the accuracy rates with priming condition (identity, morphological, orthographic) as a within-subjects and grade (third, seventh) as a between-subjects variable revealed a significant effect of prime, but only in the analysis by items, F2(2,140) = 3.42, MSE = 0.013 , p < .05. The third-graders made fewer errors in the morphological priming condition relative to the orthographic baseline condition (Bonferroni, p < .05), indicating that there was an effect of morphological priming across grades. Third-graders made more errors than the seventh-graders and this grade effect was significant by both subjects and items, F1(1,53) = 15.95, MSE = 0.024, p < .001; F2(1,70) = 7.69, MSE = 0.068, p < .01. There was no interaction between prime condition and grade.

The results of Experiment 3 replicated those of Experiment 1. After neutralizing baseline differences, identity priming was stronger than morphological priming, and the magnitude of the priming effects were comparable in the two grades. Importantly, the results of Experiment 3 clearly show that the two root letters of defective roots facilitate the recognition of targets derived from these roots. This finding replicates similar results for in adults (Velan et al., 2005). This priming effect suggests that the consistency with which the two root letters appear in their derivations support the establishment of morphemic unit representation consisting of these two letters. Experiment 3 showed that the two root letters serve as a morphemic unit very early in a child’s exposure to the written language, since it is already evident in the mental lexicon of third-grade children.

General discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effect of reading experience on the development of automatic word recognition processes, in particular on the development of the morphological level of processing. We tested the priming effects of irregular forms in Hebrew at two different stages of reading experience: in third- and seventh-grade children. We examined the morphological priming of the irregular class of defective roots, in whose derivations the canonical Hebrew three-letter root structure is not consistently preserved. These forms have been examined previously only in adult readers (Frost et al., 2000; Velan et al., 2005).

We found morphological priming when the primes were the full three-letter form of defective roots and the targets were words derived from these roots and contained all three root letters, conforming to the canonical morphological structure of Hebrew words. Both third- and seventh-graders exhibited comparable morphological priming of this type (Experiment 1). Moreover, the morphologically irregular form of defective roots, i.e. that consisting of only two root letters, primed derived words that violate the regular morphological structure—containing only those two root letters. Again, both third- and seventh-graders showed comparable morphological priming of this type (Experiment 3). These morphological priming effects are similar to those found for adult readers (Velan et al., 2005).

Interestingly, there was no priming in either the third- or the seventh-grades when the prime consisted of the full three-letter form of defective roots and the target words were derivations violating the regular morphological structure and contained only two root letters (Experiment 2). This finding contrasts with the priming found for adults under similar conditions (Velan et al., 2005). The difference between this and the other two experiments can shed light on how morphemic representations of irregular forms develop as a function of reading experience.

Our results can be explained within two alternative theoretical frameworks of word recognition and morphological processing, the localist dual-route model and the distributed connectionist approach. Dual-route models of morphological processing assume that discrete morphemic units are explicitly represented in the mental lexicon and that two mechanisms are available for the recognition of morphologically complex words: complex words are recognized either by applying rule-governed computations that parse the word into their constituent morphemes or by retrieving the representation of the whole word from memory (e.g., Burani & Laudanna, 1992; Frost et al., 1997; Schreuder & Baayen, 1995; Taft, 1994). Morphological priming results when the prime and the target share a morphemic unit, and it is the activation of this shared unit that causes the facilitation effect between the morphologically related words (e.g., Forster, 1999; Stanners et al., 1979). Thus, morphological priming effects are believed to reflect a process of morphological decomposition of morphologically complex words. The localist dual-route model suggested for morphological processing in Hebrew (Deutsch, Frost, & Forster, 1998; Frost et al., 1997) similarly postulates that the representations of all words derived from a shared root morpheme are interconnected in the mental lexicon. The root morpheme can be activated either by the extraction of the root from the whole word or via the interconnections between the lexical representations of the whole words and their root morpheme.

According to Velan et al. (2005), the priming found with adult readers by both the three-letter and two-letter forms of defective roots as primes suggests the existence of allomorphic representations for defective roots, i.e. both tri-consonantal and bi-consonantal representations. Although it is not clear from their account whether these root representations are activated following their extraction from the whole-word targets or via their morphological interconnections, it is clear from the pattern of priming that the mental lexicon of skilled readers contains such morphemic representations for irregular words.

Based on the morphological priming found with Arabic weak roots, Boudelaa and Marslen-Wilson (2004) provide an alternative interpretation. They found that words derived from weak roots primed each others, even when they were not related in meaning, therefore, they suggested that the surface morphological variants of weak roots map onto shared internal morphemic representations that abstract away from surface form variation.

How can we characterize the morphemic representation level of young readers within the localist theoretical framework? Our finding that children, like adults, show facilitation from the full three-letter defective roots (Experiment 1) indicates that the mental lexicon of these developing readers contains a representation of the full tri-consonantal root despite its irregularity. Such tri-consonantal root representation may be formed as children are exposed to the three letters of the root repeated in some of the root’s derivations. Surprisingly, it seems that the formation of this representation does not suffer from the orthographic inconsistency exhibited by defective roots. Moreover, since children as young as third-graders show this morphological priming effect, we may conclude that relatively little exposure to the written language appears sufficient for forming a canonical tri-consonantal structure of morphemic representations for this irregular class.

Like adults, both third- and seventh-grade children showed facilitation from two root letters of defective roots, when the target words contained only these two letters (Experiment 3). This indicates that their mental lexicon contains representations of bi-consonantal units with morphemic status comparable to that of the tri-consonantal root. The establishment of such bi-consonantal root representations may be supported by the consistent presence of the two root letters in the surface form of all words derived from defective roots. Again, relatively little exposure to written language seems sufficient for forming these morphemic representations.

The young children’s pattern of priming differed from that of adults since they showed no morphological priming when the prime consisted of the full three-letter root, but the target word contained only two root letters (Experiment 2). We interpret this priming failure in the context of the results of Experiments 1 and 3. With primes identical to those in Experiment 2, we saw that the three-letter form of defective roots can activate tri-consonantal root representations (Experiment 1). With targets identical to those in Experiment 2, we saw that targets containing only two root letters can activate bi-consonantal root representations (Experiment 3). Experiment 2 thus creates a situation where the tri-consonantal root representation is activated by the prime and the bi-consonantal root representation is activated by the target word. However, no facilitation was observed even though the two types of morphemic units are activated. This leads to the conclusion that there was no transfer of activation from one morphemic representation to the other, suggesting that these allomorphic representations are not connected within the mental lexicon of young readers. These allomorphic representations are assumed to be connected in the mental lexicon of adult readers (Velan et al., 2005, Experiment 5), but apparently the formation of such interconnections requires extensive experience with written language. Further research, however, is needed to elucidate the developmental processes involved in the formation of interconnections between allomorphic representations.

An alternative approach to morphological processing is based on the parallel distributed processing (PDP) or connectionist model of visual word recognition (Plaut, McClelland, Seidenberg, & Patterson, 1996; Seidenberg & McClelland, 1989; for a discussion of morphological processing, see Plaut & Gonnerman, 2000; Rueckl, 2003; Rueckl, Mikolinski, Raveh, Miner, & Mars, 1997; Rueckl & Raveh, 1999; Seidenberg & Gonnerman, 2000). In contrast to dual-route models, the connectionist approach assumes distributed representations and only one underlying mechanism for the processing of all words, including morphologically complex words. In this approach, word recognition involves the establishment of stable activation states (attractors) over sets of many processing units that represent the orthographic (spelling), phonological, and semantic properties of a word. The dynamics of this process are controlled by the weights of the connections among these units. Although morphological regularities are not explicitly represented, they constitute the major source of structure in the mapping between form and semantic units and thus play an important role in the activation dynamics that lead to the identification of a word.

Since morphologically related words are similar in both form and meaning, the changes made to the network’s weights upon encountering one word also strengthen the weights that are relevant for morphologically related words. Thus, a connectionist network detects the statistical regularities among morphologically related words in the input language through the process of learning the form-to-meaning mapping. Moreover, if a particular surface sub-pattern, such as a stem or a root, occurs in many words and consistently maps to similar meanings, the internal representations will come to reflect this structure and treat the sub-pattern componentially; i.e. the consistent sub-pattern will be represented and processed relatively independently of the other parts of the word (Plaut et al., 1996). This regularity will be reflected in the internal representations of the network. All the words that contain the repeated sub-pattern will tend to have overlapping representations. These properties affect the behavior of the network and will, for example, result in priming between morphologically complex words that share a morpheme.

Our results can be accounted for within the connectionist framework by considering the partial regularities within the class of irregular derivations of defective roots. As described above, the full three-letter pattern of the defective roots repeats in the surface form of several derivations of these roots, and the two-letter pattern repeats in all words derived from these roots. These repetitions are picked up by the network, which then becomes sensitive to these two- and three-letter units as sub-word patterns relevant in the mapping between form and meaning. Furthermore, this sensitivity will be reflected in the structure of the internal representations of the network such that all the words that share a certain three-letter pattern will have overlapping representations. Similarly, all the words that share the two-letter pattern of this root will have overlapping representations. This account therefore predicts that both the two-letter and the three-letter patterns will be potent primes for defective root derivations, as seen in the results of Experiments 1 and 3.

However, the lack of priming between the three-letter pattern and the irregular derivations (Experiment 2) suggests that there is no overlap between the internal representations of words with the three-letter and two-letter variants of the root. More extensive learning and tuning of the network’s weights, together with more encounters with examples of the defective roots and the associations between these words, may support the emergence of a generalization over the different families and result in priming between these two forms, as seen in adults.

Thus, both the classical dual-route and the connectionist models attribute the lack of priming in Experiment 2 to the lack of generalization at a more abstract level, i.e. a level that abstracts away from differences in surface form. It is possible that the inconsistency of surface form together with a small vocabulary (relative to that of skilled adult readers) delays the formation of this type of generalization.

A diachronic perspective on the acquisition of morphemic representations provided by Schreuder and Baayen (1995) similarly suggests that the semantic and phonological transparency of a morphological category play an important role in determining its acquisition rate. A derivational suffix that has several surface allomorphs, such as the Dutch diminutive suffix which has five different allomorphs, may take longer to discover than a more phonologically transparent suffix. The creation of a shared representation (a concept node in their model) that will connect the different allomorphs to a shared morph-semantic category requires relatively more extensive exposure to these forms and their meanings.

Further empirical analyses and computational simulations are needed to test the validity of our conceptual analysis and to examine how the internal representations change as a function of vocabulary growth. We are currently investigating when, after the seventh grade, the generalization over the two allomorphic forms of defective roots is acquired and whether this development depends on the direct and explicit instruction of the morphological system in Hebrew given in secondary school grades.

Further explication of a developmental model of morphological processing must wait for the elaboration of existing models of skilled morphological processing. One important question that remains to be addressed is whether root identification in Hebrew relies on graded or all-or-none processes. Frost and his colleagues (e.g., Frost et al. 2000; Velan et al., 2005) point to the structural unity of the three consonants of the root, since they show that two of the root letters of regular roots do not prime words derived from these roots, e.g., XR does not prime maXBeRet (Velan et al., 2005, Experiments 6a and 6b). The latter finding challenges the distributional and graded processing of the PDP approach. It is possible that morphological processing in Hebrew relies on the default tri-consonantal root structure. Once a tri-consonantal root is identified, it activates the morphemic representation of this root and mediates the identification of the whole word. Only in cases where such a tri-consonantal root could not be extracted from the surface orthographic form, is a bi-consonantal root representation activated and participates in the word identification process. However, given that the two root letters of defective roots are also shared by other regular roots, further research is needed to investigate whether the priming by two letters of defective roots, found for both adults (Velan et al. 2005) and young readers (Experiment 3 of the current study), is special and restricted only to irregular words or whether these two letters may also prime regular words that contain these two root letters (GV as prime and GeVeR as target).

Finally, it should be noted that Velan et al. (2005) employed the lexical decision task, we chose the naming task because children are used to name written words aloud and it thus seems a more natural task for young children. Previous research found that morphological priming effects tend to be smaller in the naming task relative to effects found in the lexical decision task (Drews & Zwitscrlood, 1995; Feldman & Prostko, 2002). However, this comparison was made with adult readers whose naming responses are very fast. Children seem to show strong morphological priming in the naming task (Raveh & Yamin, 2005). Further research should also explore whether the difference between the pattern of morphological-priming observed in children and that observed in adult readers may results from task differences.

Our study illustrates that the priming paradigm used with irregular morphological forms provides important and specific insights into the development of the mental lexicon in general, and the implicit morphological knowledge in particular. Priming effects can serve as a diagnostic tool to distinguish between knowledge structures requiring relatively less experience with printed words for their acquisition and other structures depending critically on extensive experience.

References

Anglin, J. M. (1993). Vocabulary Development: A Morphological Analysis. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 58(10), Serial #238.

Bentin, S., & Feldman, L. B. (1990). The contribution of morphological and semantic relatedness to repetition priming at short and long lags: Evidence from Hebrew. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 42A, 693–711.

Berman, R. A. (1987). Productivity in the lexicon: New-word formation in Modern Hebrew. Folia Linguistica, 20, 641–669.

Berman, R. A. (2000). Children’s innovative verbs vs. nouns: Structured elicitations and spontaneous coinages. In L. Menn, & N. Bernstein-Ratner (Eds.), Methods for studying language production (pp. 69–93). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Berman, R. A. (2002). Children’s lexical innovations: Developmental perspectives on Hebrew verb structure. In J. Shimron (Ed.), Language processing and acquisition in languages of Semitic, root-based morphology (pp. 243–291). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Boudelaa, S., & Marslen-Wilson, W. (2004). Allomorphic variation in Arabic: Implications for lexical processing and representation. Brain & Language, 90, 106–116.

Bradley, L., & Byrant, P. (1985). Rhyme and reason in reading and spelling. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Burani, C., & Laudanna, A. (1992). Units of representation for derived words in the lexicon. In R. Frost, & L. Katz (Eds.), Advances in psychology: Orthography, phonology, morphology and meaning (pp. 27–44). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Carlisle, J. (1995). Morphological awareness and early reading achievement. In L. B. Feldman (Ed.), Morphological aspects of language processing (pp. 189–209). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Castles, A., Davis, C., & Forster, K. I. (2003). Word recognition development in children. In S. Kinoshita, & S. J. Lupker (Eds.), Masked priming: The state of the art (pp. 345–360). New York: Psychology Press.

Castles, A., Davis, C., & Letcher, T. (1999). Neighbourhood effects on masked form-priming in developing readers. Language and Cognitive Processes, 14, 201–224.

Cermak, L. S., Talbot, N., Chandler, K., & Wolbarst, L. R. (1985). The perceptual priming phenomenon in amnesia. Neuropsychologia, 23, 615–622.

Cermak, L., Verfaellie, M., Milberg, W., & Letourneau, L. (1991). A further analysis of perceptual identification priming in alcoholic Korsakoff patients. Neuropsychologia, 29, 725–736.

Chapman, L. J., Chapman, J. P., Curran, T. E., & Miller, M. G. (1994). Do children and the elderly show heightened semantic priming? How to answer the question. Developmental Review, 14, 159–185.

Chialant, D., & Caramazza, A. (1995). Where is morphology and how is it processed? The case of written word recognition. In L. B. Feldman (Ed.), Morphological aspects of language processing (pp. 55–76). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Clark, E. V., & Berman, R. A. (1984). Structure and use in acquisition of word-formation. Language, 60, 542–590.

Davis, C., Castles, A., & Iakovidis, E. (1998). Masked homophone and pseudohomophone priming in children and adults. Language and Cognitive Processes, 13, 625–651.

Deutsch, A., & Bentin, S. (1996). Attention factors mediating syntactic deficiency in reading-disabled children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 63, 386–415.

Deutsch, A., & Frost, R. (2003). Lexical organization and lexical access in a non-concatenated morphology. In J. Shimron (Ed.), Language processing and acquisition in languages of Semitic, root-based morphology (pp. 165–186). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Deutsch, A., Frost, R., & Forster, K. I. (1998). Verbs and nouns are organized and accessed differently in the mental lexicon: Evidence from Hebrew. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition, 24, 1238–1255.

Drews, E., & Zwitserlood, P. (1995). Morphological and orthographic similarity in visual word recognition. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception & Performance, 21, 1098–1116.

Elbro, C., & Arnbak, E. (1996). The role of morpheme recognition and morphological awareness in dyslexia. Annals of Dyslexia, 46, 209–240.

Ellis, A. W., & Young, A. W. (1988). Human cognitive neuropsychology. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Feldman, L. B. (1994). Beyond orthography and phonology: Differences between inflections and derivations. Journal of Memory and Language, 33, 442–470.

Feldman, L. B. (2000). Are morphological effects distinguishable from the effects of shared meaning and shared form? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 26, 1431–1444.

Feldman, L. B. & Prostko, B. (2002). Graded aspects of morphological processing: Task and processing time. Brain and Language, 81, 12–27.

Feldman, L. B., Rueckl, J. G., DiLiberto, K., Pastizzo, M., & Vellutino, F. R. (2002). Morphological analysis by child readers as revealed by the fragment completion task. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 9, 529–535.

Forster, K. I. (1987). Form-priming with masked primes: The best match hypothesis. In M. Coltheart (Ed.), Attention & performance XII (pp. 127–146). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Forster, K. I. (1999). The microgenesis of priming effects in lexical access. Brain and Language, 68, 5–15.

Forster, K. I., & Davis, C. (1984). Repetition priming and frequency attenuation in lexical access. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 10, 680–698.

Forster, K. I., Davis, C., Shoknecht, C., & Carter, A. (1987). Masked priming with graphically related forms: Repetition or partial activation? Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 30, 1–25.

Forster, K. I., & Forster, J. C. (2003). DMDX: A Windows display program with millisecond accuracy. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 35, 116–124.

Forster, K. I., Mohan, K., & Hector, J. (2003). The mechanics of masked priming. In S. Kinoshita, & S. J. Lupker (Eds.), Masked priming: The state of the art (pp. 345–360). New York: Psychology Press.

Forster, K. I., & Taft, M. (1994). Bodies, antibodies, and neighborhood-density effects in masked form priming. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, & Cognition, 20, 844–863.

Frost, R., Deutsch, A., & Forster, K. I. (2000). Decomposing morphologically complex words in nonlinear morphology. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 26, 751–765.

Frost, R., Forster, K., & Deutsch, A. (1997). What we can learn from the morphology of Hebrew? A masked-priming investigation of morphological representation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 23, 829–856.

Grainger, J., Cole, P., & Segui, J. (1991). Masked morphological priming in visual word recognition. Journal of Memory and Language, 30, 370–384.

Henderson, L. (1985). Towards a psychology of morphemes. In A. W. Ellis (Ed.), Progress in psychology of language (pp. 15–72). London: Erlbaum.

Huttenlocher, J., Vasilyeva, M., & Shimpi, P. (2004). Syntactic priming in young children. Journal of Memory & Language, 50, 182–195.

Kaminska, Z., (2003). Little frog and toad: Interaction of orthography and phonology in Polish spelling. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 16, 61–80.

Levin, I., Ravid, D., & Rapapport, S. (2001). Morphology and spelling among Hebrew-speaking children: From kindergarten to first grade. Journal of Child Language, 28, 741–772.

Liberman, I. Y. (1987). Language and literacy: The obligatory of the school of education. In W. Ellis (Ed.), Intimacy with language: A forgotten basic in teacher education (pp. 1–9). Baltimore, MD: The Orton Dyslexia Society.

Loftus, G. R. (1985). Evaluating forgetting curves. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition, 6, 1068–1076.

Mann, V. A. (1991). Are we taking too narrow a view of the conditions necessary for the development of phonological awareness? In S. Brady, & D. Shankweiler (Eds.), Phonological processes in literacy: A tribute to Isabelle Y. Liberman (pp. 37–45). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Napps, S. E. (1989). Morphemic relationships in the lexicon: Are they distinct from semantic and formal relationships? Memory and Cognition, 17, 729–739.

Nation, K., & Snowling, M. J. (1999). Developmental differences in sensitivity to semantic relations among good and poor comprehenders: Evidence from semantic priming. Cognition, 70, B1-B13.

Plaut, D. C., & Booth, J. R. (2000). Individual and developmental differences in semantic priming: Empirical and computational support for a single-mechanism account of lexical processing. Psychological Review, 107, 786–823.

Plaut, D. C., & Gonnerman, L. M. (2000). Are non-semantic morphological effects incompatible with a distributed connectionist approach to lexical processing? Language and Cognitive Processes, 15, 445–485.

Plaut, D. C., McClelland, J. L., Seidenberg, M. S., & Patterson, K. (1996). Understanding normal and impaired word reading: Computational principles in quasi-regular domains. Psychological Review, 103, 56–115.

Rastle, K., Davis, M. H., Marslen-Wilson, W. D., & Tyler, L. K. (2000). Morphological and semantic effects in visual word recognition: A time-course study. Language and Cognitive Processes, 15, 507–537.

Raveh, M., & Yamin, R. (2005). Morphological awareness, morphological priming and reading: A dissociation between explicit and implicit morphological knowledge. Presented at the Annual Conference of the Israel Society for Cognitive Psychology, Ramat-Gan, Israel.

Ravid, D. (1996). Accessing the mental lexicon: Evidence from incompatibility between representation of spoken and written morphology. Linguistics, 34, 1219–1246.

Ravid, D. (2002). A developmental perspective on root perception in Hebrew and Palestinian Arabic. In J. Shimron (Ed.), Language processing and acquisition in languages of Semitic, root-based morphology (pp. 293–319). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Ravid, D., & Schiff, R. (2006). Roots and patterns in Hebrew language development: Evidence from written morphological analogies. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 19, 789–818.

Rueckl, J. G. (2003). A connectionist perspective on repetition priming. In J. S. Bowers, & C. J. Marsolek (Eds.), Rethinking implicit memory (pp. 67–104). New York: Oxford University Press.

Rueckl, J. G., Mikolinski, M., Raveh, M., Miner, C. S., & Mars, F. (1997). Morphological priming, connectionist networks, and masked fragment completion. Journal of Memory & Language, 36, 382–405.

Rueckl, J. G., & Raveh, M. (1999). The influence of morphological regularities on the dynamics of a connectionist network. Brain and Language, 68, 110–117.

Scarborough, D. L., Cortese, C., & Scarborough, H. (1977). Frequency and repetition effects in lexical memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 3, 1–17.

Schiff. R. (2003). The effects of morphology and word on the reading of Hebrew nominals. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 16, 263–287.

Schreuder, R., & Baayen, R. H. (1995). Modeling morphological processing. In L. B. Feldman (Ed.), Morphological aspects of language processing (pp. 131–154). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Schwarzwald, O. R. (2001). Modern Hebrew. Munich: Lincom Europa.

Seidenberg, M. S., & Gonnerman, L. N. (2000). Explaining derivational morphology as convergence of codes. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9, 353–361.

Seidenberg, M. S., & McClelland, J. L. (1989). A distributed, developmental model of visual word recognition. Psychological Review, 96, 523–568.

Shimron, J., & Vaknin, V. (2005). The psychological cost of vowel alter-nation: Evidence from nominal inflection in Hebrew. Paper presented at the 5th meeting of the morphological workshop, Cambridge, England.

Singson, M., Mahony, D., & Mann, V. (2000). The relation between reading ability and morphological skills. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 12, 219–252.

Snodgrass, J. G. (1989). Sources of learning in picture fragment completion task. In S. Lewandowsky, J. C. Dunn, & K. Kirsner (Eds.), Implicit memory theoretical issues (pp. 259–282). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Stanners, R. F., Neiser, J. J., Hernon, W. P., & Hall, R. (1979). Memory representation for morphologically related words. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behaviour, 18, 399–412.

Stolz, J. A., & Feldman, L. B. (1995). The role of orthographic and semantic transparency of the base morpheme in morphological processing. In L. B. Feldman (Ed.), Morphological aspects of language processing (pp. 109–129). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Taft, M. (1985). The decoding of words in lexical access: A review of the morphographic approach. In D. Besner, T. G. Waller, & G. E. MacKinnon (Eds.), Reading research: Advances in theory and practice (pp. 197–217). New York: Academic Press.

Taft, M. (1994). Interactive-activation as a framework for understanding morphological processing. Language and Cognitive Processes, 9, 271–294.

Velan, H., Frost, R., Deutsch, A., & Plaut, D. C. (2005). The processing of root morphemes in Hebrew: Contrasting localist and distributed accounts. Language and Cognitive Processes, 20, 169–206.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Haddad Center for Research in Dyslexia, School of Education, Bar-Ilan University. We thank Prof. Ram Frost and Hadas Velan of the Hebrew University for their contribution to the design of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schiff, R., Raveh, M. & Kahta, S. The developing mental lexicon: evidence from morphological priming of irregular Hebrew forms. Read Writ 21, 719–743 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-007-9088-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-007-9088-4