Abstract

An enduring and increasingly acute concern—in an age of polarized parties—is that people’s partisan attachments distort preference formation at the expense of relevant information. For example, research suggests that a Democrat may support a policy proposed by Democrats, but oppose the same policy if proposed by Republicans. However, a related body of literature suggests that how people respond to information and form preferences is distorted by their prior issue attitudes. In neither instance is information even-handedly evaluated, rather, it is interpreted in light of partisanship or existing issue opinions. Both effects are well documented in isolation, but in most political scenarios individuals consider both partisanship and prior opinions—yet, these dynamics may or may not pull toward the same preference. Using nationally representative experiments focused on tax and education policies, I introduce and test a theory that isolates when: partisanship dominates preference formation, partisanship and issue opinions reinforce or offset each other, and issue attitudes trump partisanship. The findings make clear that the public does not blindly follow party elites. Depending on elite positions, the level of partisan polarization, and personal importance of issues, the public can be attentive to information and shirk the influence of party elites. The results have broad implications for political parties and citizen competence in contemporary democratic politics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

That the citizenry should engage in deliberative and even-handed evaluations of alternatives has long been espoused as normatively desirable (Berelson 1952; Bohman 1996; Dewey 1927; Habermas 2006; Mill 1859). Yet, people fall short of this standard, failing to objectively consider evidence that challenges their positions (Lord et al. 1979), and relying on party cues at the expense of substantive information (Cohen 2003). Furthermore, there is considerable evidence of partisan motivated reasoning through which people defend their partisan identity by seeking out information that reinforces their party’s positions and counter-arguing that which challenges their party (Bisgaard 2015; Bolsen et al. 2014; Druckman et al. 2013; Petersen et al. 2013). These processes that distort information processing may lead a Democrat to support a policy proposed by Democrats, but oppose the same policy if proposed by Republicans. This has reinvigorated fundamental concerns about the ability of the public to dispassionately process political information and hold representatives accountable (Druckman 2014; Lavine et al. 2012).

While partisan motivated reasoning makes clear that party attachments inhibit objective assessments of information, it fails to account for research which suggests that people engage in issue motivated reasoning whereby information is interpreted in light of prior issue opinions (Lodge and Taber 2013). Here, a staunch supporter of a policy may hear a compelling argument against the policy but dismiss the information in defense of the prior issue attitude. That is, partisan motivations drive people to defend their partisan identity and issue motivations prompt people to defend their prior issue attitudes, and in neither instance is information even-handedly evaluated. However, by examining partisan and issue motivated reasoning separately, existing literature seemingly ignores that, in reality, both processes are often simultaneously at work.

Indeed, on most political issues, people consider their party’s stance and their prior opinions, and both features shape preference formation. This is critical because distortions in information processing from partisan and issue motivations might reinforce one another, but other times they may conflict, and the nature of the relationship between them is consequential for political behavior. Consider a Republican who opposes immigration reform. If that individual learns that Republicans in Congress are fighting against immigration reform, the party endorsement and the individual’s prior opinion pull towards the same preference: oppose reform. In this way, partisan and issue motivations work in tandem. Yet, if that individual learns that Republicans in Congress support immigration reform, the party endorsement and the individual’s prior position pull in opposite directions and partisan and issue motivations are in competition.

Intriguingly, there has been little theorizing and empirical testing about preference formation in these situations and how partisan and issue motivations intersect. This is a notable gap given that it strikes at the heart of opinion formation—to what extent do people rely on partisanship and issue attitudes in decision-making? The answer has important implications for our understanding of elite influence, the scope and source of distortions in preference formation, and is central to contemporary debates about the relative influence of partisanship and issue information in decision-making (Boudreau and MacKenzie 2014; Bullock 2011).

I first discuss contexts that shape the salience of each motivation. Existing literature suggests that elite partisan polarization accentuates partisan motivated reasoning in the public, while contexts that heighten personal issue importance increase issue motivated reasoning. I then develop a theory of intersecting motivations that posits that partisan and issue motivations can, at times, work in tandem. When party elites endorse traditional party positions consistent with policy positions of their party’s supporters, partisan and issue motivated reasoning reinforce each other and prompt partisans to be more supportive of their party’s positions. These effects are heightened when elites are polarized and the issue is personally important.

Yet, the theory suggests that partisan and issue motivations can also work in competition. When party elites endorse positions incongruent with the preferences of their party’s supporters, the elite endorsement and prior issue attitudes are in conflict. Previous research argues that partisanship trumps policy information in these instances (e.g., Cohen 2003). In contrast, my theory suggests that when party elites are out-of-step with the preferences of their supporters, issue importance can not only eliminate the effects of party endorsements, but prompt attention to policy information and shift attitudes in the opposite direction of one’s preferred party’s position. However, when motivations are in competition and issues are not personally important, partisanship is the dominant force in attitude formation. Thus, the nature of the relationship between partisan and issue motivations, and salience of each motivation considerably alters the relative influence of partisanship and policy information in preference formation.

I test the theory with nationally representative survey experiments focused on tax and education policies. In doing so, I isolate specific contexts under which the ostensibly deleterious effects of partisanship are eliminated. In contrast to existing work, the findings make clear that the public does not blindly follow party elites. At times, people can be attentive to information and shirk the influence of partisanship. I conclude with a discussion of implications for citizen competence, political parties, and information.

Partisan Motivated Reasoning and Elite Polarization

People often process information and form attitudes using “directional” motivations that lead to them to arrive at a particular conclusion—a process referred to as motivated reasoning (Kunda 1990).Footnote 1 A prominent directional motivation in political preference formation is partisan motivated reasoning (Gaines et al. 2007; Goren 2002; Groenendyk 2013; Klar 2014; Lavine et al. 2012; Petersen et al. 2013; Slothuus and de Vreese 2010); whereby identification with a party prompts individuals to seek information that buttresses their preferred party’s positions (i.e., confirmation bias) and counter-argue information that casts their party and its positions in an unfavorable light (i.e., disconfirmation bias). These partisan distortions in information processing influence policy preferences (Bolsen et al. 2014; Druckman et al. 2013; Klar 2014), evaluations of political figures (Goren 2002; Lebo and Cassino 2007; Mullinix 2015), and interpretations of events (Gaines et al. 2007). Although tested in different ways, partisan motivated reasoning is often evident in analyses of how people process and respond to information in the presence or absence of party endorsements (Bolsen et al. 2014; Druckman et al. 2013).Footnote 2

While much attention is given to individual-level variables that condition the effects of motivations (Arceneaux and Wielen 2013; Lavine et al. 2012; Taber and Lodge 2006; Taber et al. 2009), research also highlights the moderating role of political contexts. It has been argued that a salient feature of the contemporary American political landscape—elite partisan polarization—alters the influence of partisanship in preference formation in the mass public in at least two ways.Footnote 3 First, when elites are divided along party lines, they provide clearer signals about the parties’ positions on a given issue to the mass public (Levendusky 2010; Zaller 1992). Second, elite polarization that emphasizes conflict between competing sides increases the salience of partisan identities (Dancey and Goren 2010; Druckman et al. 2013; Iyengar et al. 2012; Robison and Mullinix 2015; Slothuus and de Vreese 2010). Dancey and Goren (2010) explain, “When partisan elites debate an issue and the news media cover it, partisan predispositions are activated” (686). Druckman et al. (2013) show that by heightening partisan identities, elite polarization accentuates partisan responses to information. By providing clear party signals and increasing the salience of partisan identities in the citizenry, elite partisan polarization accentuates partisan motivations in preference formation (Druckman et al. 2013).

Issue Motivations and Issue Importance

Just as people buttress partisan predispositions, they also bolster prior issue attitudes through issue motivated reasoning (Kunda 1990; Lodge and Taber 2013). By confirming arguments that support prior issue positions and counter-arguing information that challenges positions, people filter information in a manner that reinforces existing issue attitudes (Lodge and Taber 2013). A key moderator of issue motivated reasoning and the degree to which people defend their existing attitudes is personal issue importance (Leeper 2014; Visser et al. 2004). Research analyzes the effects of issue importance for information seeking (Iyengar et al. 2008; Kim 2009) and reveals, “issue importance is a primary motivation in political information consumption” (Kim 2007, p. 187; see also Jerit 2007). Krosnick et al. (1994) suggest that when people consider an issue personally important, they “expend the energy required by elaborative processing…[which] involves evaluating and relating new information to the information already stored in a person’s memory” (401–402). Thus, when people perceive an issue as personally important, they are more likely to think about it (Krosnick 1990), seek information about the topic (Kim 2007), and engage in more elaborative information processing (Krosnick et al. 1994).

However, even though issue importance catalyzes effortful information processing, such processing is not objective and is quite distinct from accuracy motivations (Druckman 2012). Visser et al. (2006) note that “perceiving an attitude to be personally important leads people to protect it against attack…. attitude importance seems to be primarily a motivator of attitude protection” (12). When an issue is thought to be important, people incorporate substantive information but connect it to issue preferences and engage in “attitude protection.” Similarly, Lecheler et al. (2009) theorize that issue importance “causes individuals to engage in more active processing of information, accumulate more relevant knowledge about an issue, and—finally—to act on their conviction” (404). Buttressing these points, Visser et al. (2004) find that issue importance motivates people to defend attitudes and neglect information that challenges prior attitudes (see also Holbrook et al. 2005). People who view an issue as personally important are motivated to engage in elaborative information processing, but seek out and filter information in a manner that protects prior issue attitudes—in this way, personal issue importance increases the salience of issue motivations (Leeper 2014).

A Theory of Intersecting Motivations

Importantly, partisan and issue motivations do not function in isolation. Instead, people often identify with parties and possess issue attitudes, and both of which are likely activated as people are exposed to political communication. For example, news stories frequently discuss a particular issue (for which people have a preference) in conjunction with partisan information (i.e., positions of party elites). People’s existing issue preferences may or may not be consistent with the position of their preferred party’s elites. In these situations, both partisan and issue motivations are at work, but little is known about how the relationship between them impacts preference formation.Footnote 4 I theorize that partisan and issue motivations can, at times, pull in the same direction, but they can also compete, and the nature of this relationship shapes attitudes. I argue that preferences are contingent upon party endorsements and the salience of motivations.

When Motivations Pull in the Same Direction

At the individual-level, when a person’s existing policy position is consistent with their preferred party’s position, partisan and issue motivations pull in the same direction. Consider a Republican who opposes a particular immigration reform and reads an article about Republicans in Congress fighting against that immigration reform. Here, the party endorsement activates partisan motivated reasoning while, simultaneously, the issue stimulates issue motivations; further, both processes pull towards the same preference: oppose immigration reform. This may also occur in the aggregate. When elites endorse “traditional” party positions on an issue, they take a position consistent with the preferences of many, but not necessarily all, people in their party. Even when ideology is conceptualized as two-dimensional and all policy preferences do not coincide with a single side of the political spectrum (Carmines et al. 2012; Treier and Hillygus 2009), there are still large portions of partisan groups for whom a stereotypical and “traditional” party endorsement is consistent with their preferences. As such, traditional elite party endorsements are likely to reinforce most partisans’ preferred position on an issue.

At the most basic level, exposure to party endorsements triggers partisan motivations. Goren et al. (2009) write: “When someone hears a recognizable partisan source advocating some position, her partisan leanings are activated, which in turn lead her to evaluate the message through a partisan lens” (806). Yet the salience of motivations impacts the degree to which people support their party’s position. If elites are polarized on the issue—increasing the salience of partisan motivations—people are more likely to prefer their party’s position (Druckman et al. 2013); and if people view the issue as personally important issue motivated reasoning may be accentuated (Leeper 2014). Uniting these expectations, party position-taking (i.e., supporting the position endorsed by one’s preferred party) should be greatest when partisan and issue motivations are salient. Thus, when partisan and issue motivations move in the same direction (e.g. partisans receive traditional elite party policy endorsements):

H1a

partisans will be more supportive of their preferred party’s position than when no party endorsements are present.

H1b

partisans will be more supportive of their preferred party’s position when there are high levels of partisan and issue motivated reasoning than when there are low levels of partisan and issue motivated reasoning.

When Motivations Compete

Partisan and issue motivations may also work in competition, pulling in opposite directions. For example, a Republican who opposes a particular immigration reform might hear that Republicans in Congress support that immigration reform. In this context, the party endorsement pulls the individual towards one position (support reform), but his or her issue preference pulls in the opposite direction (oppose reform). I theorize that when motivations compete, preferences are contingent on the relative salience of each motivation.Footnote 5

When issue motivations are low (i.e., low issue importance), partisan motivations should exert greater influence. Consider again the situation in which a Republican who opposes immigration reform is informed of Republicans in Congress supporting said reform, but here, the individual does not think the issue is personally important. Partisan motivations should trump issue motivations, and the individual will likely follow the position of partisan elites—even though party elites endorse a non-traditional position inconsistent with the partisan’s preferred position. This is consistent with research on reversed party cues (Cohen 2003; Lau and Redlawsk 2001; Rahn 1993). Again, the effects of partisanship should be accentuated under high levels of elite polarization when partisan motivations are salient (Druckman et al. 2013).

When partisan and issue motivations pull in opposite directions (Ex. partisans receive reversed party policy endorsements) and issue motivations are LOW:

H2a

partisans will be more likely to engage in partisan motivated reasoning and be more supportive of their preferred party’s position (reversed party endorsement) than when no party endorsements are present.

H2b

partisans are more supportive of the reversed party endorsement when partisan motivations are high than when they are low.

There are distinct predictions if issue motivations are high (i.e., high personal issue importance). Consider a Republican who opposes immigration reform and believes the issue to be personally important, learns that Republicans in Congress support said reform. Because the issue is personally important, the individual should engage in effortful information processing (Krosnick et al. 1994), but, again, this is not an objective form of information processing or accuracy motivated reasoning (Leeper 2014). Rather, the information is filtered in service to “attitude protection” (Visser et al. 2006). If issue motivations are high (i.e., issue is personally important) and partisan motivations are low (i.e., elites are not polarized), issue motivations should exert greater influence on preference formation; whereby partisan endorsements are abandoned and people support what is actually their preferred position (the individual does not follow the Republican endorsement, and instead opposes the immigration reform).

What happens when issue and partisan motivations are in competition and both are made salient (i.e., issue is personally important and elites are polarized)? Here, the motivations should offset each other, leading people to form preferences similar to those in which partisan motivations are not activated (no party endorsements) and issue motivations are not stimulated. High party motivations pull the Republican towards supporting immigration reform and high issue importance pulls the individual towards opposing reform, and in turn, each motivation negates the effects of the other. If partisan and issue motivations pull in opposite directions (e.g. a partisan receives reversed party policy endorsements) and issue motivations are HIGH:

H2c

and partisan motivations are low, people will be more likely to engage in issue motivated reasoning and be more supportive of their preferred party’s position in reality (take the opposing party’s position in the context of the stimuli) than when no party endorsements are present and issue importance is low.

H2d

and partisan motivations are high, issue and partisan motivated reasoning will offset each other. Preferences will be no different than a control in which no party endorsements are given and issue importance is low.

Thus, when motivations are in competition, the dominant reasoning process employed is contingent on motivation salience. When neither partisan nor issue motivations are salient, there should be evidence of partisan motivated reasoning through simple party endorsement effects relative to a control that receives no party endorsement (H2a). When issue motivations are weak and partisan motivations are salient, partisan motivated reasoning should be the dominant force (H2b). Conversely, when issue motivations are salient and partisan motivations are not, issue motivated reasoning should prevail (H2c). Finally, when both motivations are salient and are in competition, they should offset the effects of each other (H2d).

Design

To test hypotheses, I employ survey experiments that vary the salience of partisan and issue motivations and whether motivations pull in the same or opposing direction. The level of elite partisan polarization on an issue is manipulated (low or high) to vary the salience of partisan motivations (Druckman et al. 2013), and the personal importance of the issue was varied (low or high) to impact the salience of issue motivations (Leeper 2014). Finally, the nature of the relationship between partisan and issue motivations (working together or in competition) was manipulated by presenting people with either traditional or reversed party endorsements. In receiving a traditional party endorsement, partisans are likely receiving an endorsement consistent with their preferred position on the issue. In receiving a reversed party endorsement, partisans are likely receiving an endorsement that is out-of-step with their traditional party positions.Footnote 6 These manipulations provide a 2 (high or low polarization) × 2 (high or low issue importance) × 2 (traditional or reversed party endorsements), 8-condition design. To gauge preferences in the absence of party endorsements, two baseline groups were included: a condition with low polarization, low importance, and no party endorsements, and a second condition with no polarization cues, no importance cues, and no party endorsements. Although not part of a full-factorial design, these two groups allow for direct tests of party endorsements relative to specific conditions in the full design. These ten conditions are shown in Table 1.

Sample and Stimuli

To test whether people respond to information as hypothesized, survey experiments were implemented, concerning two issues, with a general population sample in February 2014 with Research Now. The sample is designed to be representative of the US adult population.Footnote 7 As with related work (Bullock 2011; Druckman et al. 2013; Levendusky 2010) pure independents are excluded and analyses are restricted to 2090 partisans including partisan “leaners” who are known to be similar to partisans in vote choice and policy preferences (Lascher and Korey 2011; Magleby et al. 2011).Footnote 8 Experimental stimuli, randomized by condition, were in the form of news articles (news source not revealed). People were randomized to 1 of 10 conditions and received an article (that matched their condition), answered questions about the issue, received a second article (that matched their condition), and again answered a series of questions. Consistent with similar work, condition number was held constant between the two articles (Bolsen et al. 2014).Footnote 9

The two articles focus separately on: a Republican proposal to simultaneously cut income taxes and increase sales taxes, and the Republican proposed “Student Success Act” to increase local control and reduce the federal government’s role in education policy. Both articles were based on Republican proposals discussed in the New York Times (see Rich 2013; Stevenson 2013 as examples). The issues were selected to test the theory with respect to two important but distinct policy domains: taxes and education. Pre-tests reveal that people are largely able to correctly identify where Republicans and Democrats stood on the tax issue and typical partisan arguments were used for each issue (see Supporting Information). Proponents of decreasing income taxes and increasing sales taxes (Republicans in reality) argued that the measure would “attract professionals with high incomes” while opponents (Democrats) suggested that the benefits are “not uniform because cuts to the income tax will benefit some more than others.” Proponents of the Student Success Act (Republicans) stated “it shifts authority away from the federal government by leaving decisions…to states and local districts,” while opponents (Democrats) “worry that localizing education standards and reducing the role of government will provide some students with an inferior education.” Thus, the issues are based on real proposals and ideological arguments and pre-tests highlight the ability of people to identify party positions.

Three features of the articles were manipulated to test predictions concerning the salience of motivations and the nature of the relationship between them. The first was whether or not people received traditional or reversed party endorsements. This involved a simple switch of which party proposed and opposed the legislation. The second feature manipulated was the level of elite partisan polarization. Individuals in high polarization conditions were told that “virtually all Republicans/Democrats support” and “virtually all Democrats/Republicans oppose” the policy and that it is an “incredibly competitive partisan atmosphere” that is “highly polarized.” Individuals in low polarization conditions are told which party proposed the legislation but are informed that “support is mixed within parties” and that the issue “has not been intensely competitive or highly polarized.” Similar, but slightly altered language was used for the second issue (see Supporting Information). These stimuli are consistent with existing manipulations of elite polarization to accentuate partisan motivations (Bolsen et al. 2014; Druckman et al. 2013). Pre-tests reveal the high polarization cue significantly increases perceptions of elite partisan divisions on each issue (p < 0.001) and low polarization significantly reduces perceptions of elite divisions (p < 0.001) relative to a control that received no polarization cue.

In an effort to increase the salience of issue motivations, the third dimension surrounds the personal importance of each issue. While personal issue importance varies by individual by issue, only using natural variation can impede causal inferences. Instead, I manipulate personal importance of the issues. A key source of issue importance is self-interest and whether people think an issue directly impacts their lives (Anand and Krosnick 2003; Boninger et al. 1995; Krosnick et al. 1994). Self-interest develops when people “expect [an object or issue] to have significant consequences for their own lives” (Apsler and Sears 1968, p. 162), and when an individual thinks that an issue has a clear and direct impact on his or her rights, privileges, or lifestyle (Bolsen and Leeper 2013; Krosnick 1990). Thus, I aim to convince people that how the issue is handled will have (or not have) direct effects on their daily lives. To do so, I created two artificial expert sources (one for each issue, Ex. Douglas Stevenson, a Harvard economist) that were pre-tested and found to be neutral and highly credible (see Supporting Information). For high importance conditions in the tax issue, the source informed people that “how this issue is handled will have direct consequences for the daily lives of nearly all Americans…this will have an impact virtually every time citizens get a paycheck and every time they make a purchase.” In contrast, the low importance condition was told “how this issue is handled will not really have consequences for most Americans.” Similar but distinct language was used for the second issue and attributed to a different expert (See Supporting Information). This type of manipulation of issue importance so as to trigger issue motivated reasoning is consistent with prior research (Leeper 2014). Pre-tests reveal that the high importance cue significantly increased perceptions of personal issue importance (p < 0.05) and the low importance cue significantly reduced personal issue importance (p < 0.001) relative to a control that received no importance cue for both issues.Footnote 10

Measures

There are two primary dependent variables. Each question was asked immediately after the participant read the article and was designed to assess respondents’ policy preference. For the tax proposal participants were asked, “Given this information, to what extent do you support increasing sales taxes relative to income taxes (increasing sales taxes and decreasing income taxes)?” This wording was selected because this single proposal was comprised of both cutting income taxes and raising sales taxes. For the Student Success Act participants were asked, “Given this information, to what extent do you support the proposed “Student Success Act?” For each issue, they responded from 0 (Strongly oppose) to 10 (Strongly support).

In an effort to determine if people engaged in motivated reasoning and if there was evidence of counter arguing, participants rated the effectiveness of arguments (See Taber et al. 2009). Participants were asked “How effective or ineffective did you find the main argument in favor of…(and the argument opposed to…)” from (1 very ineffective) to 7 (very effective). As will be discussed below, if motivated reasoning is occurring, there should be evidence of distortions—consistent with disconfirmation bias—in how people evaluate the arguments.

To test hypotheses, I present mean responses (with confidence intervals) by condition by party. As noted above, because the relationship between respondent partisanship and elite party positions are central to predictions, breaking the results down by partisanship is necessary to test hypotheses (Bolsen et al. 2014; Druckman et al. 2013). T-tests are employed to test for difference-in-means between the relevant experimental conditions for each hypothesis.Footnote 11

Results: When Motivations Pull in the Same Direction

Party endorsements should prompt partisan motivated reasoning and a discussion of an issue should stir issue motivations, and when elites endorse traditional party positions one might expect both motivations to pull in the same direction. In this section, I focus on conditions in which party elites endorse traditional positions and motivations are expected to work in tandem.

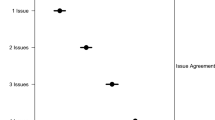

Focusing exclusively on the no party and traditional party endorsement conditions, respondents’ support for the tax and education proposals is shown in Figs. 1 and 2 (Republicans and Democrats respectively). Each bar represents the mean support for the policy proposal by experimental condition. I first examine whether elite party positions influence policy preferences when partisan and issue motivations pull in the same direction (H1a). Do the traditional party endorsements prompt partisan position-taking? For both issues, the traditional position (i.e., position in the original article and in reality) is that Republican elites proposed the legislation and Democrats are opposed. A comparison of conditions (1) [Low Polarization, Low Importance] and (3) [Low Polarization, Low Importance, Traditional Endorsement] provides a test of the traditional party position-taking when there is low polarization and low issue importance since the only difference between these groups is the presence/absence of the traditional party endorsement. Consistent with H1a, Republicans (Fig. 1) are more supportive of the proposals when elite party positions are provided than when they are not (Tax: p < 0.001; Education: p < 0.001). Similarly, Democrats (Fig. 2) are significantly less supportive of the proposals when made aware of their party’s position (Tax: p < 0.001; Education: p < 0.001). Consistent with the extant literature, these results provide strong evidence of partisans taking the position endorsed by their preferred party’s elites.

Are these effects accentuated by issue importance and elite polarization? Elite polarization should heighten partisan motivated reasoning while high issue importance should heighten issue motivated reasoning, and when partisans receive traditional party endorsements, I expect these forces to pull people in the same direction—towards the party’s position (H1b). Figures 1 and 2 provide strong evidence of polarization accentuating party position taking. For Republicans, a comparison of (3) [Low Polarization, Low Importance, Traditional Endorsement] and (5) [High Polarization, Low Importance, Traditional Endorsement] reveals that the high polarization prompt significantly increases Republican support under low issue importance (Tax: p < 0.005; Education: p < 0.002). Similar effects for polarization are documented for Republicans under high issue importance in a comparison of (4) [Low Polarization, High Importance, Traditional Endorsement] and (6) [High Polarization, High Importance, Traditional Endorsement] (Tax: p < 0.001; Education: p < 0.032). Comparisons of the same conditions show that polarization prompts Democrats to become significantly less supportive of the proposals under both low issue importance (Tax: p < 0.001; Education: p < 0.001) and high issue importance (Tax: p < 0.001; Education: p < 0.001). These tests consistently reveal that when party and issue motivations pull in the same direction, polarization prompts greater party position-taking (H1b).

H1b also predicts issue importance will prompt greater party position-taking in these contexts. Consistent with expectations, a comparison of (5) [High Polarization, Low Importance, Traditional Endorsement] and (6) [High Polarization, High Importance, Traditional Endorsement] shows that high issue importance, under high polarization, prompts Republicans to be more supportive of the proposals than when there is low issue importance, but this effect is only evident for the sales tax issue (Tax: p < 0.06; Education: p < 0.391). Comparing these same groups (5 vs. 6) for Democrats reveals that, as predicted, Democrats become less supportive of the proposals when the issue is made important (Tax: p < 0.001; Education: p < 0.001). However, the effects of issue importance are less consistent with hypotheses under conditions of low polarization. Comparing Republicans in (3) [Low Polarization, Low Importance, Traditional Endorsement] and (4) [Low Polarization, High Importance, Traditional Endorsement] reveals that Republicans become only slightly more supportive of the education proposal when the issue is made important, but there is no effect for the tax issue (Tax: p < 0.823; Education: p < 0.075). In contrast to expectations, high issue importance prompts Democrats in these low polarization conditions to become more supportive of the proposals (Tax: p < 0.01; Education: p < 0.005). Thus, the expectation that issue importance prompts greater party position-taking when party and issue motivations are working in tandem is only evident under conditions of high polarization.

In sum, partisan and issue motivations can, at times, work together to pull people in the same direction. There is consistent evidence—for both issues and for both Democrats and Republicans—that when people are made aware of elite partisan polarization, they are more likely to engage in party position-taking. High issue importance seems to reinforce issue motivated reasoning and party position-taking, but primarily in contexts of high polarization.Footnote 12

Results: When Motivations Compete

When elites endorse non-traditional (i.e., reversed) party positions they may be out-of-step with the positions of their partisan supporters. The party endorsement pulls partisans in one direction, but partisan supporters’ preferred policy position pulls in the opposite direction. In this way, we might think that partisan and issue motivations are in competition. Figures 3 and 4 present the results from conditions in which people receive reversed party endorsements in comparison to no party endorsement conditions. H2a suggests that when issue motivations are low, partisan motivations are the dominant force in preference formation. If individuals do not think the issue is important, partisans will be more likely to engage in partisan motivated reasoning and adopt their party’s reversed position than when no party endorsements are present. Comparing (1) [Low Polarization, Low Importance] and (7) [Low Polarization, Low Importance, Reversed Endorsement] confirms that Republicans are indeed less supportive of the proposals when they are told that Republican elites oppose the legislation (Tax: p < 0.001; Education: p < 0.001). Conversely, Democrats become more supportive of the tax proposal, but there is no reversed party endorsement effect for Democrats with respect to the education issue (Tax: p < 0.001; Education: p < 0.446).Footnote 13 Thus, in three of the four tests, we find evidence that when issue motivations are low, people engage in partisan motivated reasoning—even following a reversed elite party endorsement.

It is also hypothesized that partisan motivated reasoning—in the context of competing motivations—is heightened by elite polarization (H2b). This hypothesis receives mixed support. As expected, Republicans are less supportive of the proposals under high polarization in comparisons of (7) [Low Polarization, Low Importance, Reversed Endorsement] and (9) [High Polarization, Low Importance, Reversed Endorsement] (Tax: p < 0.012; Education: p < 0.001). In contrast to predictions, comparisons of the same conditions show polarization made Democrats less supportive of the tax proposal (p < 0.026). Although Democrats did not reveal a significant reversed party endorsement effect for the education issue, the high polarization prompt (7 vs. 9) makes them more supportive of the proposal as hypothesized (p < 0.063). It appears that when issue motivations are low, partisan motivations are quite powerful; and, further, in three of the four tests partisans were more supportive of their party’s reversed position when elite polarization was salient.

Heretofore, I have not discussed contexts in which motivations are in competition and issue motivations are salient. When issue importance is high and partisan motivations are low, people should engage in issue motivated reasoning—incorporating substantive information for attitude protection and abandoning the reversed party endorsement (H2c). The results conform to this expectation. Although not a direct test, when polarization is low and issue importance is high (8.) [Low Polarization, High Importance, Reversed Endorsement], Republicans are significantly more supportive of the policies than in a baseline with no party endorsements and low importance (1.) [Low Polarization, Low Importance] (Tax: p < 0.001; Education: p < 0.001). That is, individuals in the high importance condition seem to pull towards the opposing party’s position in the stimuli—which in reality, is their preferred party’s position. Democrats demonstrate a similar pattern in a comparison of the same groups (1 vs. 8); they are less supportive of the proposals under high issue importance and shift towards the opposing party’s position (Tax: p < 0.001; Education: p < 0.006). A direct test of the effects of issue importance under contexts of low polarization can be made by comparing (7) [Low Polarization, Low Importance, Reversed Endorsement] and (8) [Low Polarization, High Importance, Reversed Endorsement], and indeed, Republicans are more supportive of the opposing party’s proposal (in the stimuli) when the issue is made important (Tax: p < 0.001; Education: p < 0.001). In these instances, there is over a two-point difference in the mean preferences of high and low issue importance. As expected, the same direct test (7 vs. 8) for Democrats shows they are significantly less supportive of the policies under high issue importance (Tax: p < 0.001; Education: p < 0.005). When partisan motivations are low and issue motivations are high—and motivations are in competition—people engage in issue motivated reasoning. Not only are the effects of the reversed party endorsements eliminated, but partisans shift in the opposite direction of their preferred party’s stated position. They no longer blindly follow the reversed party endorsements, but rather, appear to connect substantive information to their preferred policy position; and in this context, are even willing to move towards the opposing party’s stated position.

When issue and partisan motivations pull in opposite directions and both are salient, I hypothesize that they will offset each other and people will respond similar to when no party endorsements are present and issue motivations are low (H2d). That is, we should no longer see evidence of partisan motivated reasoning pulling towards the preferred party’s position (reversed endorsement), nor should there be evidence of issue motivated reasoning and pulling towards the opposing party’s position. As expected, an indirect test reveals no significant difference between the high polarization high issue importance condition (10) [High Polarization, High Importance, Reversed Endorsement] and the baseline condition (1) Low Polarization, Low Importance] in the preferences of Republicans (Tax: p < 0.56; Education: p < 0.837) or Democrats (Tax: p < 0.165; Education: p < 0.998).Footnote 14 When both motivations are salient and in competition, people reveal preferences no different from baseline conditions. Are these preferences distinct from conditions where we find partisan motivated reasoning? A direct comparison of (9) [High Polarization, Low Importance, Reversed Endorsement] (i.e., partisan motivated reasoning dominant) and (10) [High Polarization, High Importance, Reversed Endorsement] (i.e., both motivations salient) reveals that Republicans in the high importance condition are more supportive of the policies than the low importance conditions—eliminating the effect of the reversed party endorsement (Tax: p < 0.001; Education: p < 0.001). A similar comparison for Democrats (9 vs. 10) in the high issue importance conditions shows that they are less supportive of the education issue than in low importance conditions (Tax: p < 0.461; Education: p < 0.049); there is a null effect for the tax issue, but this is to be expected since there was not a significant reversed party endorsement effect for Democrats under polarization on this issue. We might then ask, when both motivations are salient, are preferences distinct from the conditions where we expect issue motivated reasoning? Comparing (10) [High Polarization, High Importance, Reversed Endorsement] and (8) [Low Polarization, High Importance, Reversed Endorsement] (i.e., issue motivated reasoning) reveals a significant shift in preferences in the anticipated direction for Republicans (Tax: p < 0.001; Education: p < 0.001) and Democrats (Tax: p < 0.001; Education: p < 0.007). Thus, when both motivations are made salient and are in competition, the effects of both partisan and issue motivated reasoning are completely eliminated.

When partisan and issue motivations are in competition, the effects are contingent on the salience of each motivation.Footnote 15 There is strong evidence that when issue importance is low people engage in partisan motivated reasoning (following reversed party endorsement), and these effects are often heightened by polarization. However, when issues are thought to be important and parties are not polarized, people appear to focus on the information and engage in issue motivated reasoning—shifting towards the opposing party’s position (as conveyed in the stimuli). When both motivations are salient, there is no longer any evidence of partisan or issue motivated reasoning. This is not to suggest that when both motivations are salient and in competition that people are without bias, rather, the dueling motivations appear to negate the effects of each other and preferences are akin to baseline conditions.

Additional Analyses

To assess whether people engage in motivated reasoning and reveal evidence of counter-arguing and disconfirmation bias, respondents rated the effectiveness of arguments in favor and opposed to each proposal (see Taber et al. 2009). When motivations pull in the same direction (traditional endorsements), people should rate their party’s argument as more effective than baseline conditions, and this should be accentuated by high polarization and issue importance. When motivations compete, the effects hinge on motivation salience. Here, if partisanship is made salient via polarization and issue importance is low, people should more favorably evaluate their party’s argument (for the reversed position) than baseline conditions. However, if partisanship is not made salient and issue importance is high—and motivations are in competition—people should be less inclined to view their party’s argument as effective. If motivations are in competition and both are salient, they should offset each other, and produce argument evaluations akin to baseline groups.

Figure 5 in the Appendix shows the results for the evaluations of the argument opposed to the tax proposal (Supporting Information provides results for “pro” argument and education argument evaluations). The results largely conform to expectations. As anticipated, Republican respondents find the argument opposed to the tax proposal least effective when provided with traditional party endorsements (Republican elites arguing in favor of the proposal) and there is high polarization and high issue importance (6) [High Polarization, High Importance, Traditional Endorsement]; when partisan and issue motivations are salient and pulling in the same direction. Republicans find the opposing argument most effective when provided with reversed endorsements, high polarization cues, but there is low issue importance (9) [High Polarization, Low Importance, Reversed Endorsement]; when motivations are in competition and partisan motivated reasoning should be dominant. Further, Republicans find their party’s argument less effective than baseline conditions when motivations compete, there is low polarization, but high issue importance (8) [Low Polarization, High Importance, Reversed Endorsement]; when people are expected to shirk their party’s endorsement and arguments and engage in issue motivated reasoning. When motivations pull in opposite directions and both are made salient, the evaluations of arguments are no different than baseline no party endorsement conditions. All of which is consistent with the theory of intersecting motivations. The findings for argument evaluations for Democrats largely mirror the same pattern. Taken together, these findings provide evidence that people are actually engaging in motivated reasoning in the hypothesized manner.Footnote 16

Existing literature suggests that the degree to which people engage in partisan motivated reasoning is often contingent on the strength of partisan attachments (Lavine et al. 2012). Although not presented in text, breaking the analyses of policy preferences down by partisan strength reveals two general patterns (see Supporting Information). First, as one might expect, strong partisans are, at times, more responsive to the party endorsements and polarization prompts. Second, and perhaps more importantly, the overall patterns documented above with respect to the intersection of motivations are upheld for both strong and weak partisans. When issue motivations are made salient and are in competition with partisan motivations, even strong partisans shirk the party endorsement. I also break results down by political knowledge (see Supporting Information). There is some evidence that high knowledge respondents are slightly more responsive to the issue importance prompts, but the general pattern of results emerges across all levels of political knowledge. That is, for both high and low knowledge recipients, there is evidence that when motivations compete (i.e., people receive reversed party cues) they follow party endorsements when issue importance is low, but abandon party endorsements and engage in issue motivated reasoning when the issue is made personally important.

Addressing Limitations

A limitation of this experiment is that it exclusively relies on post-stimulus analyses of preferences. As such, it does not allow for an assessment of pre-stimuli preferences. Further, it relies on altering party endorsements to manipulate whether partisan and issue motivations are working in tandem or in competition for partisans. It may be reasonable to ask whether or not increasing the personal issue importance is, in fact, accentuating issue motivated reasoning. To address these concerns, I implemented a follow-up experiment with a convenience sample that assessed both pre and post stimulus preferences (see Supporting Information for study details and results).Footnote 17 By gauging people’s initial preferences and then introducing the experimental stimuli I can directly focus on situations in which partisan and issue motivations are pulling in the same or opposite directions.

There are two important findings from this follow-up experiment. First, accentuating personal issue importance reinforces Democrats’ initial opposition to the tax proposal. When Democrats who initially oppose the proposal are led to believe that the issue is personally important, they respond to the additional information by buttressing their existing attitude—a process consistent with issue motivated reasoning. Second, consistent with expectations, when issue and partisan are in competition (e.g. Democrats who initially oppose the proposal are provided with reversed party endorsements—told that Democratic elites support the proposal) and issue motivations are low, partisan motivated reasoning dominates, and people follow the reversed party endorsement. However, when motivations are in competition and the issue is made personally important, partisans no longer follow the party endorsement. These results bolster the previous analyses by showing that personal issue importance leads people to reinforce their prior attitudes in a manner consistent with issue motivated reasoning, and further highlight how issue importance can undercut the influence of party elites.

Results Summary

These findings suggest that opinion formation, at times, can be driven by both partisan and issue motivations pulling in the same direction (Ex. when party elites endorse traditional party positions). In these situations, across all tests, partisans are more likely to adopt their preferred party’s position when positions of party elites are revealed than when they are not (H1a). Additionally, there is strong evidence across all tests that the effects of party position-taking are accentuated by elite partisan polarization (H1b). Issue importance heightens party position-taking (H1b), but evidence was limited to conditions where elites were polarized.

Partisan and issue motivations may also pull in opposite directions and compete (Ex. when party elites take non-traditional party positions). In three of the four tests, when people are led to think that an issue is not personally important and issue motivations are not salient, they engage in partisan motivated reasoning—following a reversed elite party endorsement (H2a). Further, three of the four tests reveal that partisans were more likely to take their party’s non-traditional position when polarization cues were provided to amplify partisan motivations (H2b).

However, when motivations pull in opposite directions and an issue is made personally important and elites are not polarized, there is consistent evidence that people engage in issue motivated reasoning whereby the effects of partisan motivated reasoning are eliminated and partisans shirk the non-traditional elite endorsements—and actually shift towards the opposing party’s position (their preferred party’s position in reality) (H2c). Yet, when both partisan and issue motivations are made salient and are in competition, they negate the effects of each other. There is no longer distinct evidence of partisan or issue motivated reasoning (H2d).

These results generally conform to the hypotheses outlined in the theory of intersecting motivations. The reasoning process employed in opinion formation—and expressed policy preferences—are a function of the salience of motivations and the nature of the relationship between them (working in conjunction or in competition). The results highlight specific circumstances in which both partisan and issue motivations work in tandem, when partisanship is preeminent force in preference formation, when issue motivations trump the influence of partisanship, and when motivations negate each other.

Conclusions

It may be normatively desirable for the citizenry in a democratic polity to engage in even-handed and deliberative evaluations of arguments and information (Berelson 1952; Bohman 1996; Dewey 1927; Habermas 2006; Mill 1859), but we know that this often does not occur. Prior issue attitudes distort responses to information through issue motivated reasoning (Kunda 1990; Lodge and Taber 2013), and partisan identifications shape evaluations via partisan motivated reasoning (Bolsen et al. 2014; Lavine et al. 2012; Slothuus and de Vreese 2010). Yet, it has been ignored that, in reality, both processes are often simultaneously at work. This paper presents a theory of intersecting motivations bolstered by analyses that highlight how the dueling nature of the relationship between partisan and issue motivations and the salience of motivations shapes not only the opinion formation process, but expressed policy preferences. The theory illuminates the particular sources of distortions in opinion formation and has broad implications for partisanship and public opinion.

That partisanship exerts a powerful influence on preference formation is well documented (Bartels 2002; Cambell et al. 1960; Goren 2002; Jerit and Barabas 2012), and with few exceptions (Boudreau and MacKenzie 2014; Bullock 2011), research suggests that the citizenry follow elite party endorsements even at the expense of relevant information (Cohen 2003; Lau and Redlawsk 2001; Rahn 1993). This paper shows that the influence of partisanship in opinion formation is not unbounded. It is worth noting that by analyzing policies that are not highly salient partisan issues, I am highlighting the limitations of partisanship in a context in which the effects of party endorsements may, if anything, be exaggerated (see Arceneaux 2008; Ciuk and Yost 2015). When people view an issue as personally important and the party is out-of-step with traditional positions, partisans focus on substantive information, abandon party endorsements, and at times, shift towards the opposing party’s position in the stimuli—taking their party’s position in reality. The results are consistent with recent work suggesting that partisan divergence may often reflect partisan “cheerleading” rather than sincere differences in beliefs (Bullock et al. 2013). That is, when people believe an issue is relevant to their lives, their policy preference is guided by their prior attitude and partisan “cheerleading” is attenuated. Further, the effects of partisanship were diminished by a simple statement from an expert who told people that the issue would have consequences for their daily lives. We might reasonably expect personal issue importance to have even greater effects outside of the experimental setting when people have direct a stake in a policy and their self-interest is clear (Chong et al. 2001).

This is not to say that people engage in objective and unbiased information search or accuracy motivated reasoning, but rather, when the issue is made important, they demonstrate more elaborative information processing in service to attitude protection (Krosnick et al. 1994; Leeper 2014; Visser et al. 2006). I also recognize that partisanship often shapes issue attitudes (Jacoby 1988) and this may have happened prior to the experiment (see Druckman and Leeper 2012 on pretreatment effects). Thus, even when issue attitudes trump party endorsement effects, partisanship may still matter. However, research also suggests that issues attitudes can, at times, shape partisanship and the causal direction is context-dependent (Highton and Kam 2011). And while it may not be possible to completely divorce the two concepts empirically, I manipulate the salience of each motivation separately in a manner consistent with existing literature (Bolsen et al. 2014; Leeper 2014) and suggest that there is value in theorizing about the relationship between these separate, but related, processes.

Although this paper demonstrates that elite polarization amplifies partisan motivated reasoning, party competition need not be cast in a normatively unfavorable light. Disch (2010) states “individuals form coherent and relatively stable preferences not in spite of but by means of messages that political elites deploy in pursuit of unavowed competitive goals” (101). Much has been written about the benefits of strong parties in democratic politics (APSA 1950; Schattschneider 1942), and elite competition, through partisan motivated reasoning as shown here, as well as through partisan sorting (Levendusky 2010), helps people form stronger and more ideologically coherent political attitudes. However, strong attitudes often result in amplified distortions in information processing (Taber et al. 2009), and “the ability to accurately perceive changes in the political world is a common benchmark for gauging the quality of citizen decision making” (Jerit and Barabas 2012, p. 672). This situation prompts Lavine et al. (2012) to refer to strong attitudes as a “double-edged sword.” Thus, elite polarization accentuates partisan motivated reasoning, yet the normative assessments of the consequences for citizen competence remain unclear.

While there remains considerable debate about the extent to which the mass public is polarized (Abramowitz 2010; Fiorina and Abrams 2008), it appears that the public has increasingly sorted itself along party lines in response to elite party divisions (Levendusky 2009, 2010). That is, partisans have increasingly adopted policy preferences consistent with their preferred party’s ideological outlook. Yet, existing research provides little insight as to which issues the mass public has sorted on and why. The framework outlined here potentially provides theoretical expectations for future testing about when partisan sorting should occur. Most notably, it would seem that party elites exert considerable influence on preference formation in the mass public, and hence we should see more evidence of sorting, on issues for which elites divisions are salient and people consider of low personal importance. Conversely, one could also extrapolate the expectation that elites should be most responsive to public opinion on issues considered be personally important by partisans since these attitudes appear to be less susceptible to elite manipulation—an expectation somewhat consistent with literature highlighting the role of issue salience for elite responsiveness (Shapiro 2011).

Although I manipulated elite party endorsements to pit issue and partisan motivations against each other, it should not be lost that there are real-world contexts that may induce competition between motivations. Anytime a partisan is aware of her party’s stance on an issue, and that position conflicts with the partisan’s prior attitude, there is potential for competing motivations. Situations in which one’s preferred party takes a new policy approach or tackles a previously ignored issue for which the individual has a conflicting opinion may also catalyze conflicting motives.

Opinion formation is a function of an amalgamation of motivations. People are pulled in particular directions by partisan attachments, prior issue attitudes, and social identifications—even beyond those analyzed here. It is only by accounting for diverse motivations, the contexts that shape their salience, and how they intersect that we can grasp the complexity of how people make political decisions in contemporary democratic politics.

Notes

People also possess “accuracy” motivations—a drive to make the “correct” decision (Kunda 1990).

This process is related to but distinct from heuristic cue-taking (Petersen et al. 2013).

This is distinct from dual-process models of reasoning (Petty and Cacioppo 1986; Petty and Wegener 1999). Dual-process models such as the ELM suggest that attitude change occurs through “central” and “peripheral” routes. Central-route attitude change are based on “effortful information processing aimed at scrutinizing and uncovering the central merits of the issue,” while the peripheral route relies on less cognitive processes such as heuristics (Petty and Wegener 1999). The theory of intersecting motivations outlined here differs in at least a couple ways. Issue-motivated reasoning often leads people to engage in effortful information processing, but this is done so as to defend one’s prior attitudes, not to uncover the merits of the issue as in central processing. Further, partisan motivated reasoning need not be seen as heuristic processing (Petersen et al. 2013), since party cues activate motivational processes that require effortful strategies such as counter arguing incongruent messages.

Leeper and Slothuus (2014) posit, “motivated reasoning will look differently for individuals depending on what issues are at stake and how intensely they need to defend their prior attitudes or identities” (28). Carsey and Layman (2006) also suggest that the relationship between issue positions and partisanship is moderated by issue importance. That the outcome of conflicting motivations is contingent on the salience of motivations is akin to Converse’s (1964) discussion of “centrality.” That is, if the policy attitude is in conflict with the party position but the attitude is less central, the policy attitude will be updated to reflect the party position.

As discussed below, I avoid these assumptions with an alternative experimental design that measures people’s priors in a follow-up study.

Research Now implemented the survey via the Internet with a representative sample of the U.S. adult population. Percent Democrat (36.88), percent Republican (31.51), percent liberal (33.98), percent conservative (36.66), median age category (35–50), percent female (56.06), percent white (84.54), and median income category ($30,000–69,999). The sample employs an opt-in panel that acquires potential respondents from various partners (e.g., commercial sponsors). They invite individuals to join the survey panel and financially compensate them for participation. For each survey, ResearchNow (2015, p. 2) employs “a proprietary method of exclusively inviting pre-validated individuals, or individuals who share known characteristics…” That is, they employ an algorithm based on response rates to ensure a sample that is representative of the U.S. population, based on U.S. census figures. The company also implements a wide range of data quality validation checks, including checking for logical answers, consistent reporting, minimal non-response, realistic response times, etc. (for general discussion of these types of samples, see, e.g., Callegaro et al. 2014).

See Supporting Information for power analyses.

This ensures the first issue is uncontaminated. Randomizing issue order allows for spillover effects.

Certainly, participants come into the experiment with pre-existing levels of personal issue importance. Yet, due to random assignment, similar proportions of high/low issue importance individuals should be found in each experimental condition. However, I am primarily concerned with average treatment effects, and, as such, I simply need the manipulation to alter personal issue importance on average for most participants—which was confirmed by pre-tests. An alternative approach would be to explore whether preference formation is moderated by people’s existing personal issue importance (i.e., observational survey data analysis), but here I opt to experimentally manipulate issue importance in an effort to wield greater causal leverage.

Data and code for replication are available on the Political Behavior Dataverse webpage. Because hypotheses are directional in nature, one-tailed p values and 90 % confidence intervals are reported except when otherwise noted. As evident by p values, most results remain significant if two-tailed tests are employed. I also reference results from ANOVA tests with Bonferroni corrections to account for multiple group comparisons.

ANOVA results for multiple group comparison of when motivations pull in same directions: Democrats tax issue F(4, 542) = 168.09, p < 0.001. Bonferroni multiple comparison test reveals significant differences (p < 0.001) between all groups except conditions 3 and 4. Democrats education issue F(4, 528) = 98.20, (p < 0.001). Bonferroni test reveals significant differences (p < 0.01) between all groups except conditions 3 and 4. Republicans tax issue F(4, 439) = 58.28, (p < 0.001). Bonferroni test reveals significant differences (p < 0.02) between all group except 3 and 4, 3 and 5, and 5 and 6. Republicans education issue F(4, 426) = 27.59, (p < 0.001). Bonferroni test reveals significant differences (p < 0.02) between all groups except 3 and 4, 3 and 5 (p < 0.065), 4 and 6, and 5 and 6.

When analyses of both issues are broken down by political knowledge (see Supporting Information), there are few differences between low, moderate, and high knowledge respondents. The one exception is high knowledge Democrats in the education issue. These individuals reveal little movement across conditions on the education issue, and may, in part, be driving the null effect of the reversed party endorsement.

Because hypothesis is not directional, two-tailed tests of significance are employed here.

ANOVA results for multiple group comparison of when motivations compete: Republicans tax issue F(4, 463) = 78.11, p < 0.001. Bonferroni multiple comparison test reveals significant differences (p < 0.001) between all groups except conditions 7 and 9, and 1 and 10 (expected). Republicans education issue F(4, 445) = 47.95, p < 0.001. Bonferroni test reveals significant differences (p < 0.01) between all groups except conditions 1 and 10 (expected). Democrats tax issue F(4, 497) = 14.71, p < 0.001. Bonferroni test reveals significant differences (p < 0.01) between all groups except 1 and 10 (expected), 1 and 9, 7 and 9, 7 and 10, and 9 and 10. Democrats education issue F(4, 483) = 4.27, p < 0.003. Bonferroni test reveals significant differences only between groups 8 and 9 (p < 0.001).

People were also asked, post-stimuli, about the importance of their partisan identification to determine if the polarization and issue importance prompts shape the salience of partisanship as intended. The results are shown in the Supporting Information and reveal two patterns consistent with expectations. First, the high polarization prompts increase the importance of party identification. Second, the high issue importance cues which seems to encourage respondents to focus on substantive information, and in doing so, reduces the importance of partisanship.

Due to the small sample size and the preponderance of Democratic respondents, Republicans do not afford sufficient statistical power for analysis. Focusing only on Democrats who initially oppose the proposal (i.e. take the traditional party position) I mitigate assumptions in the previous experimental design about people’s prior attitudes.

References

Abramowitz, A. I. (2010). The disappearing center: engaged citizens, polarization, and American democracy. New Haven: Yale University Press.

American Political Science Association. (1950). Toward a more responsible two-party system: A report of the committee on political parties. American Political Science Review, 44, 1–96.

Anand, S., & Krosnick, J. A. (2003). The impact of attitudes toward foreign policy goals on public preferences among presidential candidates: A study of issue publics and the attentive public in the 2000 U.S. Presidential Election. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 33, 31–71.

Apsler, R., & Sears, D. O. (1968). Warning, personal involvement, and attitude change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9(2), 162–166.

Arceneaux, K. (2008). Can partisan cues diminish democratic accountability? Political Behavior, 30(2), 139–160.

Arceneaux, K., & Vander Wielen, R. J. (2013). The effects of need for cognition and need for affect on partisan evaluations. Political Psychology, 34(1), 23–42.

Bartels, L. M. (2002). Beyond the running tally: Partisan bias in political perceptions. Political Behavior, 24(2), 117–150.

Berelson, B. (1952). Democratic theory and public opinion. Public Opinion Quarterly, 16(3), 313–330.

Bisgaard, M. (2015). Bias will find a way: Economic perceptions, attributions of blame, and partisan motivated reasoning during a crisis. The Journal of Politics, 77(3), 849–860.

Bohman, J. (1996). Public deliberation. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute for Technology Press.

Bolsen, T., Druckman, J. N., & Cook, F. L. (2014). The influence of partisan motivated reasoning on public opinion. Political Behavior, 36, 235–252.

Bolsen, T., & Leeper, T. J. (2013). Self-interest and attention to news among issue publics. Political Communication, 30(3), 329–348.

Boninger, D. S., Krosnick, J. A., & Berent, M. K. (1995). Origins of attitude importance: Self-interest, social identification, and value relevance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(1), 61–80.

Boudreau, C., & MacKenzie, S. A. (2014). Informing the electorate? How party cues and policy information affect public opinion about initiatives. American Journal of Political Science, 58(1), 48–62.

Bullock, J. G. (2011). Elite influence on public opinion in an informed electorate. American Political Science Review, 105(3), 496–515.

Bullock, J. G., Gerber, A. S., Hill, S. J., & Huber, G. A. (2013). Partisan bias in factual beliefs about politics. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series.

Callegaro, M., Baker, R., Bethlehem, J., Göritz, A. S., Krosnick, J. A., & Lavrakas, P. J. (2014). Online panel research: History, concepts, applications, and a look at the future. In M. Callegaro, R. Baker, J. Bethlehem, A. S. Göritz, J. A. Krosnick, & P. J. Lavrakas (Eds.), Online panel research: A data quality perspetive. West Sussex: Wiley.

Cambell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W. E., & Stokes, Donald E. (1960). The American voter. New York: Wiley.

Carmines, E. G., Ensley, M. J., & Wagner, M. W. (2012). Political ideology in American politics: One, two, or none? The Forum, 10(4), 1–18.

Carsey, T. M., & Layman, G. C. (2006). Changing sides or changing minds? Party identification and policy preferences in the american electorate. American Journal of Political Science, 50(2), 464–477.

Chong, D., Citrin, J., & Conley, P. (2001). When self-interest matters. Political Psychology, 22(3), 541–570.

Ciuk, D. J., & Yost, B. (2015). The effects of issue salience, elite influence, and policy on public opinion. Political Communication.

Cohen, G. L. (2003). Party over policy: The dominating impact of group influence on political beliefs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(5), 808–822.

Converse, P. E. (1964). 2006 The nature of belief systems in mass publics. Critical Review: A Journal of Politics and Society, 18, 1–74.

Dancey, L., & Goren, P. (2010). Party identification, issue attitudes, and the dynamics of political debate. American Journal of Political Science, 54(July), 686–699.

Dewey, J. (1927). The public and its problems. New York: Holt.

Disch, L. (2010). Toward a mobilization conception of democratic representation. American Political Science Review, 105(1), 100–114.

Druckman, J. N. (2012). The politics of motivation. Critical Review, 24, 199–216.

Druckman, J. N. (2014). Pathologies of studying public opinion, political communication, and democratic responsiveness. Political Communication, 31, 467–492.

Druckman, J. N., & Leeper, T. J. (2012). Learning more from political communication experiments. American Journal of Political Science, 56(4), 875–896.

Druckman, J. N., Peterson, E., & Slothuus, R. (2013). How elite partisan polarization affects public opinion formation. American Political Science Review, 107, 57–79.

Fiorina, M. P., & Abrams, S. J. (2008). Political polarization in the American public. Annual Review of Political Science, 11, 563–588.

Gaines, B. J., Kuklinski, J. H., Quirk, P. J., Peyton, B., & Verkuilen, J. (2007). Same facts, different interpretations: Partisan motivation and opinion on Iraq. The Journal of Politics, 69(4), 957–974.

Goren, P. (2002). Character weakness, partisan bias, and presidential evaluation. American Journal of Political Science, 46(3), 627–641.

Goren, P., Federico, C. M., & Kittilson, M. C. (2009). Source cues, partisan identities, and political value expression. American Journal of Political Science, 53(4), 805–820.

Groenendyk, E. W. (2013). Competing motives in the partisan mind. New York: Oxford University Press.

Habermas, J. (2006). Political communication in media society: Does democracy still enjoy an epistemic dimension? The impact of normative theory on empirical research. Communication Theory, 16(4), 411–426.

Highton, B., & Kam, C. D. (2011). The long-term dynamics of partisanship and issue orientations. Journal of Politics, 73(1), 202–215.

Holbrook, A. L., Berent, M. K., Krosnick, J. K., Visser, P. S., & Boninger, D. S. (2005). Attitude importance and the accumulation of attitude-relevant knowledge in memory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(5), 749–769.

Huddy, L., Feldman, S., Taber, C., & Lahav, G. (2005). Threat, anxiety, and support for antiterrorism policies. American Journal of Political Science, 49(3), 593–608.

Iyengar, S., Hahn, K. S., Krosnick, J. A., & Walker, John. (2008). Selective exposure to campaign communication: The role of anticipated agreement and issue public membership. The Journal of Politics, 70(1), 186–200.

Iyengar, S., Sood, G., & Lelkes, Y. (2012). Affect, not ideology: A social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly, 76(3), 405–431.

Jacoby, W. G. (1988). The impact of party identification on issue attitudes. American Journal of Political Science, 32(3), 643–661.

Jerit, J. (2007). Issue publics, news interest, and the information environment. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, Chicago, IL.

Jerit, J., & Barabas, J. (2012). Partisan perceptual bias and the information environment. The Journal of Politics, 74(3), 672–684.

Kim, Y. M. (2007). How intrinsic and extrinsic motivations interact in selectivity: Investigating the moderating effects of situational information processing goals in issue publics’ web behavior. Communication Research, 34(2), 185–211.

Kim, Y. M. (2009). Issue publics in the new information environment: Selectivity, domain specificity, and extremity. Communication Research, 36(2), 254–284.

Klar, S. (2014). Partisanship in a social setting. American Journal of Political Science, 58(3), 687–704.

Krosnick, J. A. (1990). Government policy and citizen passion: A study of issue publics in contemporary America. Political Behavior, 12, 59–92.

Krosnick, J. A., Berent, M., & Boninger, D. (1994). Pockets of responsibility in the American electorate: findings of a research program on attitude importance. Political Communication, 11, 391–411.

Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 108(3), 480–498.

Lascher, E. L., & Korey, J. L. (2011). The myth of the independent voter, california style. California Journal of Politics and Policy, 3, 1–19.

Lau, R. R., & Redlawsk, D. P. (2001). Advantages and Disadvantages of Cognitive Heuristics in Political Decision Making. American Journal of Political Science, 45(4), 951–971.

Lavine, H., Johnston, C., & Steenbergen, M. (2012). The ambivalent partisan: How critical loyalty promotes democracy. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lebo, M. J., & Cassino, D. (2007). The aggregated consequences of motivated reasoning and the dynamics of partisan approval. Political Psychology, 28(6), 719–746.

Lecheler, S., de Vreese, C., & Slothuus, R. (2009). Issue importance as a moderator of framing effects. Communication Research, 36(3), 400–425.

Leeper, T. J. (2014). the informational basis for mass polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly, 78(1), 27–46.

Leeper, T. J., & Slothuus, R. (2014). Political parties, motivated reasoning, and public opinion formation. Advances in Political Psychology, 35(Supplement 1), 129–156.

Levendusky, M. S. (2009). The partisan sort: How liberal became democrats and conservatives became republicans. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Levendusky, M. S. (2010). Clearer cues, more consistent voters: A benefit of elite polarization. Political Behavior, 32, 111–131.

Lodge, M., & Taber, C. S. (2013). The rationalizing voter. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lord, C. G., Ross, L., & Lepper, M. R. (1979). Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: The effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(11), 2098–2109.

Magleby, D. B., Nelson, C. J., & Westlye, M. C. (2011). The myth of the independent voter revisited. In P. M. Sniderman & B. Highton (Eds.), Facing the challenge of democracy: Explorations in the analysis of public opinion and political participation (pp. 238–263). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Matthews, J. S. (2013). The electoral basis of partisan motivated reasoning. In Paper presented at the Midwest Political Science Association Annual Conference, Chicago, IL.

Mill, J. S. (1859). On Liberty. In John Gray (Ed.), John Stuart Mill on liberty and other essays, 1998 (pp. 1–128). Oxford: Oxford University Press.