Abstract

When evaluating political candidates, citizens can draw on partisan stereotypes and use partisan cues to make inferences about the candidates’ issue positions without undertaking a costly information search. As long as candidates adopt policy positions that are congruent with partisan stereotypes, partisan cues can help citizens make an accurate voting decision with limited information. However, if candidates take counter-stereotypical positions, it is incumbent upon citizens to recognize it and adjust their evaluations accordingly. Using the dual-processing framework, I hypothesize about the conditions under which individuals reduce their reliance on partisan cues and scrutinize counter-stereotypical messages, and test these hypotheses with experimental data collected from a nationally representative sample of adults. The findings show that whether individuals punish a candidate from their party for taking a counter-stereotypical position is contingent on the salience of the issue and the political awareness of the message recipient. The article concludes with a discussion of the theoretical and normative implications of these findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Even though Americans often lack a basic understanding of complicated policy debates (Delli Carpini and Keeter 1996), there are a number of cognitive heuristics available that help citizens make political decisions. Party labels are a primary example, as they provide vital cues that help citizens choose policy positions on novel issues (e.g., Druckman 2001c; Zaller 1992) and political candidates (e.g., Campbell et al. 1960; Downs 1957). Because political parties have policy reputations (cf. Snyder and Ting 2002) and the policy preferences of party adherents in the mass electorate tend to line up with partisan stereotypes (Green et al. 2002), citizens are able to make sense of political discourse and, ultimately, evaluate politicians in light of the stereotypes they possess about the major political parties’ stances on issues (Rahn 1993). Accordingly, uninformed citizens can use partisan cues to make the same decisions they would if they were actually informed (Druckman 2001a). Under these conditions, partisan cues enhance democratic accountability and responsiveness.

However, a reliance on partisan cues is only an efficient strategy for making desired choices insofar as partisan elites take positions that coincide with those partisan stereotypes. What happens if a party elite stakes out positions that are inconsistent with partisan stereotypes (henceforth, counter-stereotypical position taking)? Do citizens’ partisan loyalties allow the “messenger [to] overwhelm the message” (Kuklinski and Hurley 1994, 731; see also Rahn 1993; Van Houweling and Sniderman 2007, Unpublished), or can partisans identify counter-stereotypical behavior and punish partisan elites who refuse to toe the party line?

In the remainder of this paper, I build on Rahn’s (1993) seminal study of partisan stereotypes and use the dual-processor model of information processing to hypothesize about the conditions under which citizens hold candidates from their party accountable for taking counter-stereotypical positions. I then test these hypotheses using experimental data gathered from a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults. In contrast to previous research (Hovland et al. 1953; Kuklinski and Hurley 1994; Rahn 1993), I do find instances in which citizens punish their party’s candidate for taking positions that are at odds with their party’s platform. However, the negative effects of counter-stereotypical messages are contingent on the salience of the issue raised by the messenger and the political awareness of the recipient. As political awareness and issue salience decreases, individuals give more latitude to partisan elites by failing to negatively evaluate candidates who espouse counter-stereotypical positions.

The Effects of Counter-Stereotypical Position Taking

Because the cognitive capacity of humans is limited, people are unable to systematically process every piece of information that they encounter. Consequently, individuals often rely on information shortcuts, commonly called heuristics, to arrive at judgments without expending a great deal of cognitive energy in the process (Nisbett and Ross 1980). In political settings, citizens use a number of heuristics to aid their evaluation of candidates (cf. Lau and Redlawsk 2001). Principal among these are partisan cues and stereotypes. When evaluating a candidate, individuals need not invest much energy trying to figure out whether the candidate’s positions on issues align with theirs, if they know the candidate’s party affiliation. All things being equal, Democrats can assume that they will be better represented by Democratic candidates and Republicans can assume the same about Republican candidates (Rahn 1993).

Yet there is no guarantee that political candidates will always adopt policy positions that conform with prevailing partisan stereotypes. Politicians may sometimes find it expedient to advocate political positions that are at odds with their party platform. One need only look to recent history to find examples: President Bill Clinton’s move rightward on the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and welfare reform and President George W. Bush’s move to the left on education reform and the Medicare drug plan. In these instances, what are people to do when confronted with a counter-stereotypical message delivered by a politician affiliated with their political party? If individuals process the message systematically, they can identify the expectancy-incongruent issue position, reject it, and punish the source by downgrading their evaluation of him or her. However, if individuals process the message heuristically, they may use the partisan cue as a positive indicator and discount or ignore the counter-stereotypical message.

From a normative perspective, if partisan cues overwhelm the message and allow partisan elites to violate value consistency, it may require a modification of the sanguine view toward source cue heuristics that permeates much of the public opinion literature. Rather than consistently being “a reasonable way” to surmount lack of knowledge about political issues (Druckman 2001c, 78; see also Druckman 2001b; Lau and Redlawsk 1997; Lupia 1994; Lupia and McCubbins 1998; Mondak 1993, but see Bartels 1996, 2003; Kuklinski and Quirk 2000; Lau and Redlawsk 2001), individuals who rely on heuristic processing risk being lead astray by counter-stereotypical messages. When credible elites take counter-stereotypical positions, it may be more desirable for citizens to engage in systematic processing and actively attempt to understand the message before deciding to accept or reject it.

Extant research on the effects of political rhetoric demonstrates that individuals are capable of deliberately weighing the considerations presented in political messages and forming an opinion that is consistent with their predispositions (Brewer 2001; Haider-Markel and Josly 2001; Nelson et al. 1997a, b). However, studies of counter-stereotypical messages suggest that source cues, particularly partisan cues, can short-circuit systemic processing, causing people to dissociate their predispositions from their subsequent opinions (Hovland et al. 1953, 42; Kuklinski and Hurley 1994; Rahn 1993; Van Houweling and Sniderman 2007, Unpublished). In her path-breaking study, Rahn (1993) presented subjects in an experiment with a video clip of two fictitious candidates, one Republican and the other a Democrat, making policy statements on six issue areas, and she uncovered little evidence of partisans punishing their candidates for making counter-stereotypical statements (see also Van Houweling and Sniderman 2007, Unpublished). In their study, Kuklinski and Hurley (1994) attributed the statement that “African–Americans must stop making excuses and rely much more on themselves to get ahead in society” to one of the following political figures: George H. W. Bush, Ted Kennedy, Jesse Jackson, or Clarence Thomas. They found that black subjects’ interpretation of the message’s meaning depended on the race of the messenger. If the statement was attributed to Bush or Kennedy, black subjects saw it as evidence that “white people are writing us off,” whereas other black subjects who read the same statement attributed to either Jackson or Thomas saw it as an inspirational blandishment for “we black people can do it on our own.” Taken together, these studies suggest that when an easy-to-use heuristic, such as a party label or racial cue, is available, individuals will use it to evaluate the source of a message in lieu of scrutinizing the message itself.

Yet this conclusion may be incomplete if individuals engage in dual processing. Dual-processor models contend that humans are not wedded to one type of information processing strategy, but depending on the circumstances, we are capable of processing information either heuristically or systematically (Chaiken et al. 1989; Petty and Cacioppo 1986).Footnote 1 Because systematic processing is costly, individuals require a reason to engage in it. Thus, in the absence of motivating factors, people generally process messages heuristically. Intriguingly, a counter-stereotypical message delivered by an elite from one’s political party should qualify as a motivating factory and cause individuals to take notice and pay more attention to the message (Maheswaran and Chaiken 1991; Nelson and Garst 2005; Rahn 1993). However, it is likely that both individual-level and contextual factors affect whether individuals process counter-stereotypical messages systematically, and considering how these factors moderate the effects of counter-stereotypical messages on candidate evaluations may contribute to reconciling the apparent disconnect between the theoretical expectation derived from the dual processing framework that counter-stereotypical statements lead to systematic processing and major findings present in the literature to the contrary.

Moderators

The content of the message itself may provide individuals with a motivation to scrutinize counter-stereotypical statements. We know that people tend to give more weight to salient issues in their evaluations of political candidates (e.g., Krosnick 1988), and that personal involvement with an issue increases people’s motivation to systematically process arguments (Petty and Cacioppo 1986). Accordingly, if the expectancy-incongruent statement is about an issue that the message recipient finds of little importance or salience, he or she may be unmotivated to process the message systematically, and instead, rely on partisan cues when evaluating the speaker. In contrast, counter-stereotypical statements about salient issues may induce the message recipient to pay attention and reduce his or her reliance on partisan cues when evaluating the speaker.

Hypothesis 1:

Individuals are more likely to negatively evaluate their party’s candidate when the candidate makes a counter-stereotypical statement on a salient issue than they are when the candidate makes a counter-stereotypical statement on a less salient issue.

Nevertheless, there are a number of reasons why the negative effects of counter-stereotypical statements may be more pronounced among ideologically consistent partisans (i.e., liberal Democrats and conservative Republicans; henceforth ideological partisans). First, the capacity for ideological thought reduces reliance on party cues and increases the likelihood of evaluating candidates via the systematic processing route (Lavine and Gschwend 2007). Second, because party stereotypes are related to the ideological positions occupied by the two major parties (i.e., the Democratic party is to the left of the Republican party), counter-stereotypical statements can also be viewed in ideological terms (cf. Van Houweling and Sniderman 2007, Unpublished). Thus, a Democrat who makes a conservative statement is also likely making a counter-stereotypical statement, and such a statement is more likely to raise the ire of liberal Democrats than it is among conservative Democrats. In the context of the research question posed here, then, one would expect that ideological partisans are especially motivated to process counter-stereotypical messages systematically and punish candidates who make them. Consequently, by studying the effects of counter-stereotypical messages among all partisans, one may underestimate their impact.

Hypothesis 2:

The negative effects of counter-stereotypical statements should be stronger among ideological partisans relative to all partisans.

Yet, even on salient issues, citizens cannot punish a candidate for failing to toe the party line if the partisan stereotype for the issue is not readily accessible in their memory. Individuals who routinely pay attention to politics possess a larger store of knowledge about politics as well as the contextual information required to recognize expectancy-incongruent messages (Zaller 1992). As political awareness increases, individuals are more likely to process political messages systematically and less likely to rely on heuristics, such as partisan cues (Cobb and Kuklinski 1997; Kam 2005). Furthermore, partisan cue heuristics are more likely to lead the politically unaware astray and causing them to vote “incorrectly” by choosing a candidate they would not have chosen under full information (Lau and Redlawsk 2001).

Hypothesis 3:

Individuals are more likely to punish partisan elites for making counter-stereotypical statements as their level of political awareness increases.

Of course, it is also possible that even politically aware individuals find partisan stereotypes for low-salience issues unaccessible, and even if they are accessible, these individuals may be unmotivated to process counter-stereotypical messages about low-salience issues systematically. As Chaiken et al. (1989, 220) argue, “people are economy-minded souls” who must have a compelling reason to engage in effortful thought (see also Petty and Cacioppo 1986, 146).

Hypothesis 4:

Politically aware individuals are no more likely than politically unaware individuals to hold their partisan elites accountable for counter-stereotypical statements on low-salience issues.

Experimental Design

Like most studies that investigate the effects of political messages on attitude formation, I use experimental data to test the hypotheses outlined above. Unlike the majority of this work, which relies on a college student subject pool, I sampled subjects from a nationally representative panel of adults constructed by Knowledge Networks (KN). KN Web TV panelists, who were selected via a random digit dialing sample, are given a free Internet connection and Microsoft WebTV as long as they remain in the panel (cf. Clinton and Lapinski 2004, 75). These data are more representative than the subject pool in the typical laboratory experiment, and KN data, in general, have been shown to be more reliable than telephone survey data (Krosnick and Chang 2001, Unpublished).

For the purpose of this study 1,126 adult subjects were assigned to one of eight treatment conditions (see Table 1 for a the assignment breakdown by treatment conditions).Footnote 2 Subjects in the treatment groups were asked to read a mock newspaper article attributed to the New York Times Online Edition about a campaign speech delivered by a fictional congressional candidate named Kirk Watson and answer a few survey questions. All participants completed tasks via the Internet on the WebTV provided by KN. In order to minimize demand effects, subjects were told that the purpose of the study was “to see how effectively the Internet provides information on current issues” rather than the real aim of the study.Footnote 3

The 2 × 2 × 2 design tests the hypotheses by manipulating information in the news story about the partisan affiliation of the candidate (Democrat or Republican) and his position (stereotypical or counter-stereotypical) on either abortion (high-salience issue) or the assignment of responsibility for environmental regulation within the federal system (low-salience issue).Footnote 4 Abortion is an easy choice as a high-salience issue, because it is a long-standing conflict in American politics that has been overlaid onto the party system (Adams 1997), and recent research shows that opinions on abortion figure prominently in candidate evaluations (Abramowitz 1995). Conversely, the question over which level of government should regulate the environment is a quintessential low-salience issue. Although it does tap into disagreements over the scope of government power, which is a long-standing conflict in American politics (Aldrich 1995), it is a technical issue that addresses policy means, rather than policy ends. Except in those situations where the policy process raises fundamental issues of fairness (Smith et al. 2007), individuals are typically uninterested in policy means (Carmines and Stimson 1980).

Table 2 displays the wording of the mock newspaper article. Subjects read the same introductory and concluding paragraphs. The candidate’s issue position and partisanship is manipulated in the middle paragraph. Note that the structure of the article, in terms of length, quote placement, and wording, is very similar across manipulations in order to reduce confounding effects.

After reading the news article, subjects answered a brief questionnaire, providing the measures for the study. Subjects were asked two questions that tap their evaluation of the candidate. The first asked, “How much would you like to see Kirk Watson win the congressional race?” and the second asked, “How well do you think Kirk Watson would represent you?” Subjects placed their answers on a 5-point Likert scale.Footnote 5 In addition, subjects were asked the standard party identification item and a battery of factual questions to measure their level of political awareness. The political awareness scale was created by combining subjects’ answers to factual items in the post-treatment survey with a measure of their educational attainment (see Price and Zaller 1993).Footnote 6 (The post-treatment questionnaire is reported in the appendix.) Finally, KN possessed a measure of subjects’ political ideology prior to the study, eliminating the need to measure it with the post-treatment instrument and allowing me to identify ideological partisans (i.e., liberal Democrats and conservative Republicans).

Analysis

The effects of the treatment condition were estimated by regressing candidate evaluations on an indicator for the candidate’s issue position (1 = conservative [pro-life or pro-devolution], 0 = liberal), an indicator for the candidate’s party affiliation (1 = Republican, 0 = Democrat), an indicator for the salience of the issue (1 = high salience, 0 = low salience), indicators for subjects’ party identification, and all the possible interactions among these variables. These results are reported in the appendix (see Table A2).

In order to gauge the extent to which individuals downgrade a candidate from their political party for making a counter-stereotypical statement, I compare partisans who received a counter-stereotypical statement to partisans who received a stereotypical statement. Democrats who read an article in which the Democratic candidate took a conservative position (i.e., a counter-stereotypical position) are compared to Democrats who read an article in which the Democratic candidate took a liberal position (i.e., a stereotypical position). Likewise, Republicans who read an article in which the Republican candidate took a liberal position are compared to Republicans who read an article in which the Republican candidate took a conservative position. Because subjects in the stereotypical treatment condition evaluated a candidate of their party who espoused positions that are consonant with the party platform, they provide an appropriate baseline. Subjects were randomly assigned to the treatment groups, so there is no reason to suspect that subjects in different groups perceive the policy platform of their party differently. If counter-stereotypical statements draw a rebuke from rank-in-file partisans, the candidate in the counter-stereotypical treatment condition should be rated lower than the candidate in the stereotypical treatment condition.

Given the complexity of the interactive models presented in Table A2, it is necessary to combine multiple coefficients and estimate the appropriate standard errors for these combined effects in order to estimate the effects of counter-stereotypical messages (see Brambor et al. 2006). Specifically, I calculate the first difference between the combined effect for each counter-stereotypical condition (e.g., the pro-choice Republican) and the combined effect for each corresponding stereotypical condition (e.g., the pro-life Republican), and I do so for both high and low salience issue conditions.Footnote 7 For example, the counter-stereotypical effect for the Republican candidate in the high-salience condition is estimated as follows,

where Y = candidate evaluation, RC = Republican candidate indicator, CP = conservative position indicator, R = Republican subject indicator, and HS = high-salience issue indicator. In one set of models, party identification is measured with an indicator for Democrats and an indicator for Republicans (columns 1 and 3 in Table A2), and to facilitate testing hypothesis 2, the measure is restricted to ideological partisans in another set of models with an indicator for liberal Democrats and an indicator for conservative Republicans (columns 2 and 4 in Table A2). The first differences, displayed in Table 3, are grouped by partisanship and the salience of the issue addressed by the candidate.

In the high-salience condition, Republicans and, to a lesser extent, Democrats evaluated their party’s candidate more negatively if he took a counter-stereotypical position on abortion. Republicans rated the pro-choice Republican candidate over one point lower than the pro-life Republican, whereas Democrats only rated the pro-life Democratic candidate about a third of a point lower than the pro-choice candidate. In contrast, counter-stereotypical position taking had a strong negative effect on candidate evaluations among ideological partisans of both parties. Conservative Republicans rated the pro-choice Republican candidate nearly two points lower than the pro-life Republican candidate, and liberal Democrats rated the pro-life Democratic candidate over one point lower than the pro-choice Democratic candidate. These are meaningful shifts as they lower the average support for the candidate and evaluations of his representational quality to approximately 2 on the evaluation scale—a negative rating below the scale mid-point. Note that less than 10% of liberal Democrats and conservative Republicans who saw their party’s candidate take a stereotypical position on abortion rated the candidate at a 2 or lower on these measures.

Conversely, subjects did not register significantly less support for their party’s candidate if he took a counter-stereotypical stance on the low-salience issue, and while they were less likely to view the counter-stereotypical candidate as a good representative, these effects are not of much substantive significance. Moreover, as the last two columns of Table 3 show, the effect sizes for the counter-stereotypical message in the high-salience issue condition are significantly more negative than the effect sizes in the low-salience issue condition among Republicans, conservative Republicans, and liberal Democrats. Taken together, these findings provide support for hypothesis 1. Counter-stereotypical position taking receives a stronger rebuke from the partisan rank-in-file on high salience issues than it does on low salience issues.

There is also partial support for hypothesis 2. In the high-salience condition, liberal Democrats rated the counter-stereotypical Democratic candidate more negatively than all Democrats did as a group (p = 0.014 for candidate support; p = 0.004 for candidate representativeness), and there is a more pronounced difference in counter-stereotypical position-taking effects between the high- and low-salience issue conditions among liberal Democrats than there is among all Democratic party adherents (p = 0.097 for candidate support; p = 0.032 for candidate representativeness).Footnote 8 Conversely, conservative Republicans’ assessment of the pro-choice Republican candidate were not significantly more negative than the assessment of Republicans as a group. Thus it appears, at least among subjects in this sample, that abortion is more of a hot-button issue for Republicans as a whole than it is for Democrats as a whole.

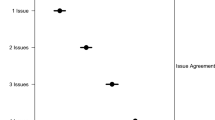

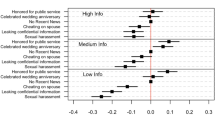

Next, I test the moderating effect of political awareness by re-estimating the models presented in Table A2 with all the relevant interactions between the variables in that model and the political awareness scale. These results are displayed in the appendix (see Table A3). To aid the interpretation of the interaction terms, I calculate the substantive effect of counter-stereotypical position taking across levels of political awareness. The results for the high-salience condition are displayed in Fig. 1 and the results for the low-salience condition are shown in Fig. 2.Footnote 9 The sloped line denotes the effect of the counter-stereotypical message across levels of political awareness, the flat line references zero, and the shaded area depicts the 95% confidence interval. When the 95% confidence interval crosses the reference line, it indicates that the subjects did not rate the counter-stereotypical candidate differently than the stereotypical candidate at that level of political awareness.

The data offer partial support for hypothesis 3. Figure 1 shows that as political awareness increases, Democrats were more likely to rate negatively the Democratic candidate if he took a counter-stereotypical position on abortion. Indeed, at the lower end of the political awareness scale, Democrats did not rate the counter-stereotypical Democrat more negatively than the stereotypical Democrat at all. In contrast, all Republicans in the high-salience issue condition, except for those at the very bottom of the political awareness scale, rated the counter-stereotypical Republican more negatively than the stereotypical Republican (see upper half of Fig. 1). The same picture emerges if we restrict our focus to the effects of counter-stereotypical position taking among ideological partisans (see bottom half of Fig. 1). These findings echo those encountered in Table 3: Abortion appears to be of more fundamental importance to Republicans as a group than Democrats. The abortion issue only becomes a decisive factor in the candidate evaluations of moderately and highly aware Democrats.

Hypothesis 4 is also supported by the data. Across levels of political awareness, subjects did not appear to punish the candidate from their party for taking a counter-stereotypical position on the low-salience issue. As Fig. 2 shows, even politically aware partisans were not moved by the counter-stereotypical message about environmental policy regulation. With the possible exception of highly aware conservative Republicans, subjects were not less likely to support the candidate of their party if he took a counter-stereotypical position on the low-salience issue, nor does it appear that counter-stereotypical position did much to substantively shake subjects’ impression that the candidate would represent them just as well as the stereotypical candidate from their party.

Discussion

In sum, the evidence suggests that under particular conditions, counter-stereotypical position taking can lead individuals to process political messages systematically when evaluating candidates rather than merely relying on partisan cues. As the political awareness of the message recipient and the salience of the issue position increases, individuals are more likely to evaluate negatively candidates affiliated with their political party who depart from the party line. If the issue is particularly salient, as abortion appears to be among Republicans, it may be possible for even politically unaware individuals to judge the messenger by scrutinizing his or her position on the issue rather than simply relying on the partisan heuristic.

In turn, counter-stereotypical statements on an issue of low-salience do not appear to motivate individuals—even politically aware ones—to punish their party’s candidate. These findings are consistent with the social psychological model of partisanship (Campbell et al. 1960; Green et al. 2002). For many individuals the affective attachment to a political party is acquired before issue preferences. Furthermore, people’s political decisions center less on particular policy alternatives—what Stokes (1963, 373) called “position issues”—and more on “valence issues” that involve the achievement of a general policy goal over which there is little disagreement (e.g., low crime, good economy, freedom, moms, and apple pie). Consequently, party elites have some room to maneuver, at least among their rank-in-file, when it comes to adopting issue positions. If the findings from Rahn’s (1993) seminal study and Van Houweling and Sniderman’s (2007, Unpublished) recent study are instructive, there may be a wide range of political issues on which citizens will indulge their party’s elites. If so, perhaps, party elites are constrained only on a subset of highly salient issues.

Of course, given the limitations of the present study and previous ones, some caveats are in order. As for the present study, subjects were asked to evaluate an unknown entity, which if anything, should have increased subjects’ willingness to punish counter-stereotypical statements. While this approach lends some credence to the findings with respect to the low-salience issue, it raises the question about the freedom with which known partisan elites can adopt counter-stereotypical positions on salient issues. On the one hand, popular partisan elites have more credibility and trust among party adherents than unknown party elites, which may increase the level of confidence that party adherents achieve when heuristically evaluating the statements delivered by popular partisan elites vis-a-vis those delivered by unknown partisan elites. So, perhaps with less motivation to scrutinize the statements made by popular party figures, the party rank-and-file may allow them to stake out counter-stereotypical positions on even highly salient issues. On the other hand, people may also possess stronger expectations that popular political elites toe the party line, which would increase their motivation to scrutinize the positions espoused by visible political figures on these issues. Accordingly, known politicians may risk impugning their credibility by taking counter-stereotypical positions on such issues.

Although these competing expectations can be addressed in a straightforward manner in future experiments that vary the popularity of the politicians who are attributed counter-stereotypical statements, scholars should also consider ways to address a general limitation inherent in many experimental studies of communication. Just because subjects allow a known political elite to take a particular counter-stereotypical position in a laboratory setting, does not mean that it would actually be possible for political elites to behave in such a fashion without facing negative consequences in real settings. For instance, politicians are not merely constrained by the reactions of their party’s rank-in-file members. They must also please the party activists and fundraisers who provide the necessary resources that allow them to be viable political candidates, and to complicate matters further, these opinion leaders may also affect the candidate evaluations of rank-in-file members. Intriguingly, because two of the major candidates for the Republican presidential nomination—Rudy Giuliani and Mitt Romney—have previously taken pro-choice positions, the 2008 Republican presidential primary may offer some instructive real-world evidence on this score.

Moreover, scholars should continue investigating how and why particular issues become salient. Research on the evolution of political issues undermines the notion that party elites are simply responding to the demands of the party’s rank-and-file (Adams 1997; Carmines and Stimson 1989), but a purely elite-driven model of issue salience provides an incomplete account of why some issues captivate the attention of the party base, while others do not. Abortion offers a case in point. Both pro-life and pro-choice interest groups play an equally active role in the American party system, and as a consequence, Democratic and Republican Party elites are highly polarized on abortion policy (Sanbonmatsu 2002). Nevertheless, the data here strongly suggest that rank-in-file Republicans, irrespective of the attention they pay to politics, weight abortion position-taking heavily in their candidate evaluations, while only politically aware rank-in-file Democrats treat the issue with such importance. Why did the pro-life agenda become so central to the mass-level politics of the Republican Party but less so in the Democratic Party? One possibility may involve the extent to which religious beliefs guide abortion preferences among the Republican base, but surely other possibilities exist.

Despite its limitations, the present study does contribute to the study of counter-stereotypical position taking by sketching out the conditions under which politicians are either punished for or given a free pass on taking counter-stereotypical issue positions, as well as pointing to fruitful avenues of future research. Ultimately, additional research is necessary if we wish to understand fully the situations under which people systematically evaluate political messages or merely rely on heuristic cues that are peripheral to the message.

Notes

Petty and Cacioppo (1986) call systematic processing, central processing and heuristic processing, peripheral processing. The elaboration likelihood model that they develop is similar to Chaiken, Liberman, and Eagly’s framework, but differs in several key respects. Nevertheless, both theories generate the same observable implications about the effects of counter-stereotypical messages in this research setting. For the sake of expositional clarity, I use the heuristic-systematic terminology found in Chaiken et al. (1989).

An additional 142 subjects were assigned to a control group. These individuals were asked to state their preferences on the issues raised in the treatment conditions, but because they did not read any articles about the candidates, they were not asked to evaluate them. The treatments did not affect the subjects’ issue attitudes, and thus, are not discussed in this study. These results are available from the author upon request. The experiment was conducted between January 6 and 12, 2005; the completion rate was 72.4% and the AAPOR-standard response rate 3 was 41.4%. Because it was drawn from a nationally representative panel, the sample is quite diverse. (See Table A1 in the appendix for a summary of demographic characteristics.)

At the end of the study, subjects were informed that the news story was not real.

As a randomization check, a joint-test of statistical significance shows that treatment assignment does not systematically covary with subjects’ demographic and attitudinal characteristics (age, gender, education, income, ethnicity, martial status, urbanity, region, home ownership, party identification, ideology, and knowledge about politics) (χ2[189] = 184.22, p = 0.585).

Subjects who responded “don’t know” to these items were placed at the center of the scale. The results generated by this approach do not differ substantively from the alternative strategy in which these subjects are excluded from the analysis.

KN measured subjects’ educational attainment prior to the study, and so it was unnecessary to include it in the post-treatment survey. The results are not affected substantively by excluding education from the scale or randomly assigning don’t know responses to correct and incorrect responses to address the possibility that particular individuals are more likely to answer “don’t know” on knowledge questions even when they know the correct answer (cf. Mondak 2000).

I calculated the first differences and their standard errors with Monte Carlo simulations using the Clarify program for Stata (Tomz et al. 2003).

These p-values were calculated by subtracting the counter-stereotypical effect for all Democrats from the counter-stereotypical effect for liberal Democrats, estimating the standard error of the difference, and calculating the resulting t-statistic. All p-values are one-tailed.

The values reported in Figs. 1 and 2 are first differences calculated in the same fashion as the ones in Table 3, except the political awareness of the subject is taken into account. For instance, the expected counter-stereotypical effect for a Democrat in the high-salience issue condition is estimated as follows:

$$ {\rm E}(Y|RC = 0,CP = 1,D = 1,HS = 1,PA = x) - {\rm E}(Y|RC = 0,CP = 0,D = 1,HS = 1,PA = x), $$where Y = candidate evaluation, RC = Republican candidate, CP = conservative position, D = Democratic subject, HS = high-salience issue, PA = political awareness, and x = an arbitrary value on the PA scale. These quantities and their 95% confidence intervals were estimated with the Clarify program (Tomz et al. 2003).

References

Abramowitz, A. I. (1995). It’s abortion, stupid: Policy voting in the 1992 presidential election. Journal of Politics, 57(1), 176–186.

Adams, G. D. (1997). Abortion: Evidence of an issue evolution. American Journal of Political Science, 41(3), 718–737.

Aldrich, J. H. (1995). Why parties? The origin and transformation of political parties in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bartels, L. M. (1996). Uninformed voters: Information effects in presidential elections. American Journal of Political Science, 40(1), 194–230.

Bartels, L. M. (2003). Democracy with attitudes. In M. B. MacKuen & G. Rabinowitz (Eds.), Electoral democracy. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Brambor, T., Clark, W. R., & Golder, M. (2006). Understanding interaction models: Improving empirical analyses. Political Analysis, 14, 63–82.

Brewer, P. R. (2001). Value words and lizard brains: Do citizens deliberate about appeals to their core values? Political Psychology, 22(1), 45–64.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W. E., & Stokes, D. E. (1960). The American voter. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Carmines, E. G., & Stimson, J. A. (1980). The two faces of issue voting. American Political Science Review, 74(1), 78–91.

Carmines, E. G., & Stimson, J. A. (1989). Issue evolution: Race and the transformation of American politics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Chaiken, S., Liberman, A., & Eagly, A. H. (1989). Heuristic and systematic information processing within and beyond the persuasion context. In J. S. Uleman & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), Unintended thought. New York: Guilford Press.

Clinton, J. D., & Lapinski, J. S. (2004). “Targeted” advertising and voter turnout: An experimental study of the 2000 presidential election. Journal of Politics, 66(1), 69–96.

Cobb, M. D., & Kuklinski, J. H. (1997). Changing minds: Political arguments and political persuasion. American Journal of Political Science, 41(1), 88–121.

Delli Carpini, M. X., & Keeter, S. (1996). What Americans know about politics and why it matters. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of democracy. Boston: Addison Wesley.

Druckman, J. N. (2001a). The implications of framing effects for citizen competence. Political Behavior, 23(3), 225–256.

Druckman, J. N. (2001b). On the limits of framing effects: Who can frame? Journal of Politics, 63(4), 1041–1066.

Druckman, J. N. (2001c). Using credible advice to overcome framing effects. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 17, 62–82.

Green, D., Palmquist, B., & Schickler, E. (2002). Partisan hearts and minds: Political parties and the social identities of voters. New Haven: Yale University.

Haider-Markel, D. P., & Josly, M. R. (2001). Gun policy, opinion, tragedy, and blame attribution: The conditional influence of issue frames. Journal of Politics, 63(2), 520–543.

Hovland, C. I., Janis, I. L., & Kelley, H. H. (1953). Communication and persuasion. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Kam, C. D. (2005). Who toes the party line? Cues, values, and individual differences. Political Behavior, 27(2), 163–182.

Krosnick, J. A. (1988). The role of attitude importance in social evaluation: A study of policy preferences, presidential candidate evaluations, and voting behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55(2), 196–210.

Kuklinski, J. H., & Hurley, N. L. (1994). On hearing and interpreting political messages: A cautionary tale of citizen cue-taking. Journal of Politics, 56(3), 729–751.

Kuklinski, J. H., & Quirk, P. J. (2000). Reconsidering the rational public: Cognition, heuristics, and mass opinion. In A. Lupia, M. D. McCubbins, & S. L. Popkin (Eds.), Elements of reason: Cognition, choice, and the bounds of rationality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lau, R. R., & Redlawsk, D. P. (1997). Voting correctly. American Political Science Review, 91(3), 585–598.

Lau, R. R., & Redlawsk, D. P. (2001). Advantages and disadvantages of cognitive heuristics in political decision making. American Journal of Political Science, 45(4), 951–971.

Lavine, H., & Gschwend, T. (2007). Issues, party, and character: The moderating role of ideological thinking on candidate evaluation. British Journal of Political Science, 37(1), 139–163.

Lupia, A. (1994). Shortcuts versus encyclopedias: Information and voting behavior in California insurance reform elections. American Political Science Review, 88(1), 63–76.

Lupia, A., & McCubbins, M. D. (1998). The democratic dilemma: Can citizens learn what they need to know? New York: Cambridge University Press.

Maheswaran, D., & Chaiken, S. (1991). Promoting systematic processing in low-motivation settings: Effect of incongruent information on processing and judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(1), 13–25.

Mondak, J. (1993). Source cues and policy approval: The cognitive dynamics of public support for the Regan agenda. American Journal of Political Science, 37(1), 186–212.

Mondak, J. (2000). Reconsidering the measurement of political knowledge. Political Analysis, 8(1), 57–82.

Nelson, T. E., & Garst, J. (2005). Values-based political messages and persuasion: Relationships among speaker, recipient, and evoked values. Political Psychology, 26(4), 489–515.

Nelson, T. E., Clawson, R. A., & Oxley, Z. M. (1997a). Media framing of a civil liberties conflict and its effect on tolerance. American Political Science Review, 91(3), 567–584.

Nelson, T. E., Oxley, Z. M., & Clawson, R. A. (1997b). Toward a psychology of framing effects. Political Behavior, 19(3), 221–246.

Nisbett, R., & Ross, L. (1980). Human inference: Strategies and shortcomings of social judgment. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 19, 124–205.

Price, V., & Zaller, J. (1993). Who gets the news? Alternative measures of news reception and their implications for research. Public Opinion Quarterly, 57(2), 133–164.

Rahn, W. M. (1993). The role of partisan stereotypes in information processing about political candidates. American Journal of Political Science, 37(2), 472–496.

Sanbonmatsu, K. (2002). Democrats, republicans, and the politics of women’s place. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Smith, K. B., Larimer, C. W., Littvay, L., & Hibbing, J. R. (2007). Evolutionary theory and political leadership: Why certain people do not trust decision makers. Journal of Politics, 69(2), 285–299.

Snyder, J. M. Jr., & Ting, M. (2002). An informational rationale for political parties. American Journal of Political Science, 46(1), 90–110.

Stokes, D. E. (1963). Spatial models of party competition. American Political Science Review, 57(2), 368–377.

Tomz, M., Wittenberg, J., & King, G. (2003). CLARIFY: software for interpreting and presenting statistical results. Version 2.1. Stanford University, University of Wisconsin, and Harvard University. January 5. Available at http://www.gking.harvard.edu/

Zaller, J. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible with the help of the Time-sharing Experiments for the Social Sciences project, which is funded by National Science Foundation Grant 0094964, Diana C. Mutz and Arthur Lupia, Principal Investigators. I am also deeply indebted to Jamie Druckman, Don Green, Martin Johnson, Megan Mullin, seminar participants at the University of California-Riverside, and the anonymous referees for their thoughtful comments at various phases in the project. As always, though, any errors remain my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Survey Question Wording

Appendix: Survey Question Wording

-

Q1A. [Subjects in abortion condition and control group] What statement best describes your opinion on abortion?

I strongly believe that abortion should rarely be legal

1

2

3

4

5

I strongly believe that abortion should be legal most of the time

-

Q1B. [Subjects in federalism condition and control group] Which level of government should have the most responsibility when it comes to protecting the environment?

I strongly believe that the federal government should have the most responsibility

1

2

3

4

5

I strongly believe that the state and local government should have the most responsibility

-

Q2. Based on what you know now, how much would you like to see Kirk Watson win the congressional race?

I would very much like to see Kirk Watson win

1

2

3

4

5

I would not like to see Kirk Watson win at all

-

Q3. Based on what you know now, how well do you think Kirk Watson would represent you?

I strongly believe Kirk Watson WOULD represent me well

1

2

3

4

5

I strongly believe Kirk Watson would NOT represent me well

-

Q4. Generally speaking, when it comes to politics would you consider yourself...

-

(1) A Democrat, (2) A Republican, (3) An Independent, (4) Or something else? (8) Don’t Know

-

-

Q5. Who is Bill Frist?

-

(1) Secretary of the Treasury, (2) U.S. Senate Majority Leader, (3) Prime Minister of Canada, (8) Don’t Know

-

-

Q6. Whose responsibility is it to determine if a law is constitutional or not?

-

(1) President, (2) Congress, (3) Supreme Court, (8) Don’t Know

-

-

Q7. How much of a majority is required for the U.S. Senate and House to override a presidential veto?

-

(1) Unanimous, (2) Two-thirds, (3) One-fifth, (4) Simple majority, (8) Don’t Know

-

Model Estimates

Below are the model estimates that generated the substantive effects reported in the analysis section of the article. The effects reported in Table 3 are derived from the models reported in Table A2, and the effects reported in Figs. 1 and 2 are derived from the models displayed in Table A3.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Arceneaux, K. Can Partisan Cues Diminish Democratic Accountability?. Polit Behav 30, 139–160 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-007-9044-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-007-9044-7