Abstract

Despite much public speculation, there is little scholarly research on whether or how ideology shapes American consumer behavior. Borrowing from previous studies, we theorize that ideology is associated with different forms of taste and conspicuous consumption: liberals are more drawn to indicators of “cultural capital” while conservatives favor more explicit signs of “economic capital”. These ideas are tested using birth certificate, U.S. Census, and voting records from California in 2004. We find strong differences in birth naming practices related to race, economic status, and ideology. Although higher status mothers of all races favor more popular birth names, higher status, white liberal mothers more often choose uncommon, culturally obscure birth names. White liberals also favor birth names with “softer, feminine” sounds while conservatives favor names with “harder, masculine” phonemes. These findings have significant implications for both studies of consumption and debates about ideology and political fragmentation in the United States.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Over the past several years, numerous books and news items have warned of growing social and political fragmentation in the United States. With political elites increasingly divided by ideology and the country ever more stratified by wealth, many journalists and academics worry that ordinary Americans too are becoming irrevocably separated by class and political belief (e.g., Brooks 2004; Cahn and Carbone 2010; Murray 2012). As Bishop and Cushing (2008) contend, “Our country has become so polarized, so ideologically inbred, that people don’t know and can’t understand those who live just a few miles away.” Interestingly, nearly all of these accounts point to differences in consumer behavior as an important barometer of America’s putative fragmentation. Ideological divisions allegedly are evident in the products Americans consume: e.g., liberals like Volvos, Whole Foods, and National Public Radio, while conservatives like Nascar, Walmart, and country music (Nunberg 2006). From this perspective, America’s ideological polarization is as prominent in its citizens’ non-political behavior as it is in their policy opinions and voting patterns.

There are, however, two major problems with these assessments. First, the empirical evidence about American political fragmentation is decidedly mixed. Ideology certainly divides America’s elected officials (Poole and Rosenthal 1997), but the depth and breadth of ideological division in the mass public remains highly contested (e.g., Fiorina et al. 2010; Abramowitz and Saunders 2008). It still remains unclear how many Americans can be called truly ideological (Converse 1964, Wood and Oliver 2012) or how much their ideology is manifest in their extra-political behavior. This is especially the case with a complex phenomenon like consumption. Scholars have long recognized that consumer goods are often purchased for the sake of fashion or their prestige value (e.g., Veblen 1899; Blumer 1969; Bourdieu 1984) but relatively little attention has been given to the impact of ideology on either consumer taste in general or on the social signaling embedded within consumption practices in particular.

Second, most empirical assessments about the relationship between ideology and consumer behavior are bedeviled by problems of endogeneity and unmeasured variables. Social and political behavior does not occur in a vacuum but is influenced by both market and political forces. Because consumption patterns are so highly determined by marketing strategies of economic producers, it is difficult to assess whether ideologically tinged consumer behavior is a result of ideology or external forces (Lieberson 2000). Similarly, consumption practices may coincide with ideology because of region, social class, or other variables. Drivers in New England, for example, may drive more Subarus because Subaru is a “liberal” car or they may drive more Subarus because Subaru markets its products in a region that has more liberals and also snowy, mountainous roads. What may look like “liberal” or “conservative” consumer behavior actually may be more a result of unmeasured factors or marketing strategy rather than ideological conviction.

To evaluate whether consumer differences are indicative of American ideological fragmentation, one needs to first anticipate how ideology shapes consumption and then to test these theories on behaviors that are relatively free from the marketing efforts of producers. This paper seeks to do both. We hypothesize that America’s predominant liberal and conservative ideologies are evident in consumption patterns, largely because of the values associated with these belief systems and the types of adherents they attract. Building on previous theories of Veblen (1899) and Bourdieu (1984), we hypothesize that liberals will utilize signals of “cultural capital” in their consumer choices while conservatives invoke symbols of “economic capital.” Moreover, liberals and conservatives will favor social signals with specific symbolic connotations, i.e., liberals being more apt to employ feminine symbols while conservatives favor masculine ones.

These ideas are tested with a behavior that is highly related to taste and fashion but largely free from market effects: birth names. Using data from the 2004 California Birth Registry, 2000 U.S. Census, and 2004 precinct-level voting returns, we find that ideology has a clear relationship with both the types of birth names and the sounds of birth names. In contrast to their high status and conservative peers, educated, white mothers in liberal neighborhoods are significantly more likely to choose uncommon names and names with more “feminine” phonemes like schwa and L and are less likely to choose names with “masculine” phonemes like K. Although differences in naming practices by education, race, and income are expected, the differences by ideology are remarkable and have implications for scholarly research on status, consumption, and ideological fragmentation in the United States.

Ideology and Conspicuous Consumption

The first challenge to examining the relationship between consumption practices and ideology in the United States is determining what each of these polysemic concepts entail. Social scientists have long recognized that consumer behavior is influenced not just by the immediate concerns of price, convenience, and utility but also by taste, fashion, and prestige (Veblen 1899; Lieberson 2000). People purchase goods and services not simply for their intrinsic value but also for the social signals they convey, what Veblen famously termed “conspicuous consumption.” Historically, these signaling practices were evident in luxury goods used by the upper strata to provoke “invidious comparison” and then appropriated by the lower strata in the service of “pecuniary emulation” (Bagwell and Bernheim 1996). In contemporary consumer culture, however, the dynamics of prestige and social signaling are subject to a kaleidoscope of styles and fads that go beyond a simple “top-down” dynamic, particularly as upper classes appropriate working class or multi-cultural symbols as fashion statements (Corneo and Jeanne 1997; Holt 1998). By substituting blatant signals of wealth for more subtle indicators of “cultural capital” (Bourdieu 1984), the upper classes today invoke a wide range of references, from the high traditional to the exotic, in a continually shifting pattern of taste (Bryson 1996).Footnote 1

Yet, for all the research on consumption and social signaling, there are few accounts about how and why high status individuals choose particular mechanisms of social differentiation or why they diverge in their tastes. The American upper strata may be remarkably “omnivorous” in their consumer behavior (Peterson and Kern 1996), but most scholarly attention has focused on interclass differences and left intra-class variance in consumption largely unexplained. This is precisely where non-economic factors like political ideology may have an effect (Kozinets and Handelman 2004).Footnote 2 Not only do some ideologies contain direct invocations about consumption choices (e.g., “green” products), they often prescribe the social signals such choices are meant to invoke. For example, in the 1950s, Chinese communist leaders mandated the wearing of Zhongshan suits among party officials to signal proletarian unity.

These considerations raise a difficult question: which elements within the predominant American political ideologies of “liberalism” and “conservatism” either explicitly proscribe or demand certain types of consumption practices, standards of taste, or acceptable forms of social signaling?Footnote 3 In reviewing historical studies of American ideology, we find few explicit mandates within either liberalism or conservatism on consumer behavior (Hartz 1995; Hamby 2006). Although consumer movements occasionally appear (e.g., “fair trade” or “Boycott France!”), neither belief system has specific rules about consumption or social signaling that are evident in ideologies like communism, environmentalism, or many types of religious fundamentalism (Gurova 2006). This commonality between U.S. liberalism and conservatism may reflect a consensual emphasis in the American creed toward “liberty, individualism, and laissez-faire economics” that is generally embraced by both ideological traditions (Lipset 1997).

But while liberalism and conservatism have few explicit mandates on consumption, there are numerous social, ideational and psychological elements associated with these ideologies that may shape consumer behavior. In this paper, we will consider three. First, ideology may relate to consumption via religious affiliations. Many Americans identify themselves as conservative less from a commitment to limited government and more from a traditional religious attachment (Ellis and Stimson 2012). Many religions have specific proscriptions about consumer behavior (e.g., kosher laws) which, in turn, may be then picked up by their ideological adherents. In particular, we might expect more conservatives to follow traditional markers of taste or status or to invoke Biblical references in their consumption patterns.

Second, ideologues may seek to advertise their ideological identities in their consumption patterns. Many ideological identities arise from symbolic association with particular social groups or certain core values: conservatives are more likely to identify with free market values, cultural traditionalism, and nationalism; liberals are more likely to identify with groups seeking civil rights and with economic egalitarianism (Conover and Feldman 1981; Feldman 1988). Consumer choices may act as a way of publicizing their affiliation with these groups or values. Such signals may be as explicit as a political bumper sticker or as subtle as a Peruvian hand-woven bag that is meant to understatedly signal a concern with international social justice.

Third, ideologies may shape the way elites signal their elevated status. We suspect this is the most likely hypothesis because ideology, as measured by contemporary surveys, is most prevalent among Americans at the high ends of the economic and educational stratum (Wood and Oliver 2012). Ideology, in turn, may influence how these higher echelons choose to set themselves apart. Among conservatives, with their higher tolerance of economic inequality (Gross et al. 2011), their greater preference for familiarity and closure (Jost et al. 2009), and their higher income-to-education ratios (Brint 1985), should be more likely to signal economic capital in their consumer choices. This could entail both a clear repertoire of established, luxury goods and a tendency to avoid trends and other vicissitudes of fashion.

American liberalism, by contrast, historically has emphasized greater economic equality, social justice, innovation, and mutli-culturalism (Hamby 2006). On personality tests, liberals are more open to novel experience and tolerant of ambiguity (Jost et al. 2009). In addition, educated liberal are more likely to come from lower paying, professional occupations (Brint 1985). With typically less disposable income yet higher education levels, high status liberals should be less likely to signal economic capital and, instead, choose markers of cultural prestige. Liberals should also be more likely to be sensitive to new trends and quicker to adopt new fashions. In short, liberals should rely on displays of cultural capital in their consumer choices.

The immediate difficulty with testing these assertions is that producers make deliberate efforts to market their goods and services to particular populations; consequently, any observed differences in consumer patterns across the ideological divide must be understood as endogenous to the production and advertising process. There is, however, one type of common social marker that is free of any entity that profits by its usage: birth names. Although subject to influences like religion, language, culture, and ethnicity, birth names are also an important expression of taste, social position, and status aspiration (Lieberson 2000). Over the past several decades, birth names have become increasingly based on emotional or aesthetic considerations and less dependent on familial obligation and historical convention, at least in the industrialized world (Edwards and Caballero 2008). This makes birth names a good metric for examining social signaling, especially since they impose no financial costs to the parent.

But as indicators of taste, status signaling, and ideology, birth names also present some theoretical and methodological challenges. The greatest is how a concept like “economic capital” can be manifest in a symbol that is financially costless. One strategy is to focus on social convention. Historically, in the United States, traditional Anglo-Saxon names have been associated with social preeminence: immigrants have long adopted anglicized birth names as a mechanism for promoting upward mobility and names associated with ethnic minorities often carry negative economic repercussions (Bertrand and Mulainathan 2004; Figlio 2005). Thus, absent any other cues, one would expect that conventional birth names like John, Thomas, Elizabeth, and Catherine should signal higher economic capital in the United States. Tradition alone, however, is no longer a status signifier as birth names are increasingly subject to fashion and trend (Lieberson 2000), much of which appears to be related to economic signaling. For instance, numerous popular names, like Amber, Heather, and Stephanie, were first chosen by upper classes and later embraced by the lower strata in a form of pecuniary emulation (Levitt and Dubner 2005).

It is likely that ideology is involved in this tension between tradition and innovation in high status names. Elites who adopt innovative names are usually invoking more esoteric, cultural references. The name Brittany, for example, was not a widely accessible cultural symbol in the 1970s when the name first became popular and initially had a cultural cache as a reference to a remote French province (Lieberson 2000). If innovative birth names first appear as expressions of cultural capital, then liberal elites are most likely to popularize them, especially given that liberals are typically more comfortable embracing novelty and differentiation. As innovative birth names become popular among elites, they will shift in connotation and become more of a signal of economic prestige. Some time afterwards, the name will diminish as a prestige symbol as lower classes begin adopting more of these names themselves (e.g., the changing status of names like Dylan, Amber, and Kayla) thus sending liberal elites in search of ever new and obscure markers (Yoganarasimhan 2012).

A further distinction in liberal naming practices should be in the choice of names. Whereas many low status mothers may choose uncommon names as a way of expression individuality or ethnic heritage (Lieberson and Mikelson 1995), many of these are entirely fabricated (“Inti,” “Areea”), have unconventional spellings (“Madysyn,” “Andruw”), or are variations on common names (“Lakeitha,” “De-John”). Elite liberals, when they choose uncommon names, should be less likely to make up a name rather than choose a pre-existing word that is culturally esoteric (e.g., “Namaste,” “Finnegan,” “Archimedes”) because fabricating a name would diminish its cultural cache. After all, the value of cultural capital comes, not from its uniqueness, but from its very obscurity.

Names are also complicated as social signals because they have meaning in both their terms and in their sounds. Birth names like Destiny, Infinity, Hennessey, and Pepsi are not simply monikers but references to specific ideas, products, or cultural precepts; Sasha, Malia, Bristol, Track, and Trigg have distinctive phonetic tones that possibly carry emotive and symbolic connotations (Whissell 2001). With tens of thousands of different names given to children every year, this presents an immediate challenge in categorizing these cultural and phonetic signals, particularly in reference to ideological imperatives.Footnote 4

Although there are innumerable ways to group names by both meaning and sound, one criterion is particularly compelling: gender. Ideological discourse is highly embedded with gendered metaphor-liberals employ nurturing-feminine metaphors while conservatives are drawn to more domineering-paternalistic metaphors (Lakoff 2002). If such metaphorical tendencies encapsulate ideological thinking, then it should be evident in an overtly symbolic choice like a birth name. Liberals should be drawn to more “feminine” phonetic structures, i.e., names that are multi-syllabic, with “softer” phonemes like L, and names that begin or end in vowels, particularly a schwa sound (Cassidy et al. 1999). Conversely, conservatives should be drawn to more “masculine” phonemes like K, B, and D. These phonemes are not only more common in boys’ names (Cutler et al. 1990) but also have emotional connotations of aggression and strength (Whissell 2001). Gendered patterns in phonetic structure may also reflect gendered patterns of status and economic prestige. Since, men have more dominant social and economic positions in American society, masculine sounding names may also signal higher economic capital. If this assertion is true, then a tendency toward favoring masculine sounding names should be more common not only among conservatives, but also among higher status parents as well.

Data and Measures

To test these hypotheses, data are used from the 2004 Birth Statistical Master File maintained by the Office of Vital Records in the California Department of Health Services. They comprise information from birth certificates for all children born in California in 2004, which provides 545,018 initial cases for the file. With the approval of the California Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects, the data were drawn including the first names of all children, mothers, and fathers (where available), and the mother’s education, race, ethnicity, and addresses. By cross-referencing the listed address with Google maps, the longitude and latitude of for each respondent with an identifiable address record was calculated.Footnote 5 With arcGIS, this geographic information was used to identify the census tract of each birth mother, which was then matched with demographic data from 2000 U.S. Census. In addition, the geocodes were used to identify the voting precinct of each mother and, using precinct shape files, the voting records from the general election of 2004, which are stored in the Statewide Database for the State of California archived at the University of California.Footnote 6 Together, these files provide a profile of both the individual characteristics of each mother and the demographic and political characteristics of their neighborhoods.

The primary variables of interest are the first names given to each child and several variables were constructed from the available list. The first set of variables is based on the relative frequencies of the names in file. For the 545,018 recorded births in the state of California in 2004, there were 52,589 differently spelled names. Although these names can be categorized in many ways, for this paper, three types were chosen: Unique name, a dichotomous measure indicating the name is unique (by spelling) to the database; Uncommon name, a dichotomous measure indicating the name was one of fewer than 20 names spelled the same way for children born in California in 2004 (the category also includes all Unique names); and, Popular name, a dichotomous measure indicating the name was of the 100 most popular names for boys or girls in California in 2004.Footnote 7 In addition, a dichotomous variable called Parent’s name also was created that indicates whether the birth name was identical to the name of record for either the mother or father for girls and boys respectively.

In addition to the frequency of the name, variables were also constructed relative to the phonemes within the name. To extract this information, the phonetic structure of the names was derived by cross-referencing each name with the Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) Pronouncing Dictionary. This online data source lists 133,746 entries translated into phonetic structures in North American usage. It uses an Arpabet transcription code for phonemes which we use here. These entries are the most commonly recognized and used words in American English. Of the 52,589 different birth names given in California in 2004, 5,160 were in the CMU pronouncing dictionary; although these represented only 9.8 % of the total number of different names in the file, they accounted for 76 % of all children born in California in 2004, largely because so many children have conventional or popular birth names. For expedience, henceforth all birth names that are not in the CMU pronouncing dictionary will be labeled as “unrecognized.”

Once the phonemes were identified we examined the proportion of names by gender that contained each of the phonemes. Partial results are listed in Table 5 in the Appendix. As with prior research (Cassidy et al. 1999; Cutler et al. 1990), the California data show that a higher proportion of boys are given names with “hard” consonant sounds, especially among the more common phonemes of K, B, D, and T. The only common vowel phonemes that are significantly more common among boys are O (as in Joe) and ER (as in the second vowel sound of Robert).Footnote 8 A higher proportion of girls have names with the “softer” L phoneme or the common vowel phonemes of schwa (as in the last syllable of Ella) or IY (as in the last syllable of Emily).

For explanatory variables, the California birth records file provides data on the mother’s education level and the mother’s recorded race and ethnicity. Education level is coded as number of years of school completed. Mother’s race is coded as either white, black, American Indian, one of 21 different Asian or Pacific Island nationalities, or is listed as missing data. Ethnicity is recorded in a variety of forms with up to two overlapping terms like “American,” “Caucasian,” “Mexican,” “Hispanic,” “Armenian,” “Brazilian,” etc. From both the race and ethnicity items, birthmothers were then categorized as either “white,” “black,” “Latina,” or “Asian/Pacific Islander”.Footnote 9

From the census data, various measures about the birth mother’s social context were extracted at the tract level. These include median household income, percent of residents over age 25 with a college degree, the percent of residents by race (non-Latino white, black, and Latino), the percent of residents over 18 born outside of the United States, and the percent of residents over 18 who speak only English at home. To measure ideology, precinct-level voting records were taken from the general election of 2004. These were comprised of the average voting percentages in each precinct for five ballot items: the percent voting for Democrat John Kerry for President, the percent voting for Democrat Barbara Boxer for Senate, and the percent voting for three ballot measures, propositions 61, 63, and 71.Footnote 10 The voting percentages (scored high for more liberal) of these six items were averaged (with a mean score for the sample of .53 and a standard deviation of .13).Footnote 11 A further description of this item is in “Appendix 3” section.

Ideology and Categories of Names

If birth names signal status concerns or social aspirations, then these signals vary considerably by sex, race, education, income, and ideology. Consider some simple statistics comparing the percent of children given unique, uncommon, popular, or parents’ names by the mother’s race or ethnicity and education level, as listed in Table 1. The greatest differences in naming patterns occur by virtue of the child’s sex. Across all categories, girls are much more likely to be given unique or uncommon names while boys are far more likely to be given popular or patrilineal names. For example, among all California births in 2004, 5.6 % of boys were given unique names compared to 8.4 % of girls; meanwhile 41 % of boys were given popular names compared to 30 % of girls. Most strikingly, 11.4 % of boys were named after their father of record while only 1 % of girls were named after their mother.

Many of these differences are highly contingent on the race, ethnicity, and education of the mother. Whites and Latinas, the two groups that comprise the overwhelming majority of birth mothers in California, are much less likely to give their children unique or uncommon names compared to blacks or Asian/Pacific Islanders. For instance, fewer than 6 % of whites and Latinas gave their girls unique names compared to 26 % of blacks, and 18 % of Asian mothers. But white and Latina mothers are not identical in their naming practices—Latina mothers are at least twice as likely to give patrilineal names than white mothers and are more likely to give boys common or popular names. Mothers in the Asian/Pacific Islander category display an interesting pattern of giving a high percentage of unique or uncommon names, a large percentage of popular names, and a very low percentage of parental names, patterns that reflect the tremendous ethnic and linguistic diversity within this group and diverse cultural practices in naming. Because of this and other issues, the naming behaviors of Asian/Pacific Islanders will not be examined any further.Footnote 12

Racial and ethnic differences in naming patterns are also highly contingent upon the mother’s education. Among whites, the percent of children given popular or patrilineal names varies considerably by education. Only 24 % of girls born to white mothers with less than a high school diploma were given a popular name compared to 38 % of white mothers with a college degree. White mothers with less education are also much more likely to pass on patrilineal names; 15 % of less-educated white mothers used the fathers’ names for their boys compared to only 3 % of those with a college degree. Less educated white mothers were also more likely to choose unique or uncommon names than those with a college degree, although these differences are not nearly as great in magnitude.

Educational differences in naming patterns are also evident among blacks and Latinos. The percentage of unique names among black children, for example, is highly contingent upon their mothers’ education. Whereas 36 % of girls born to a black mother with less than a high school education have unique names, only 17 % of girls born to black mothers with a college degree are uniquely named. Latina mothers with more education are also more likely to give their girls popular names and slightly less likely to give patrilineal names, although these differences are not as great in magnitude as for whites and blacks.

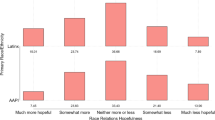

The importance of class status is also evident in looking at naming patterns in relationship to neighborhood social and political status. Table 2 lists the percent of children given popular names by quintiles of median household income and education and the neighborhood ideology score.Footnote 13 As with a mother’s own education, the income and education of her neighborhood also corresponds with her naming practices; specifically, the percent of mothers choosing popular names for their children rises with the income and education of their neighbors regardless of her race or ethnicity. Although not depicted in Table 2, the inverse also holds for unique and uncommon names, which are less common in higher status neighborhoods. The only exception to this trend is for Latino boys, whose names seem largely insensitive to socio-economic differences in their mother’s neighborhood. Neighborhood ideology also corresponds with different naming patterns. Irrespective of race, the percent of mothers choosing popular names generally decreases as the mother’s neighborhood becomes more liberal, especially among residents of the most liberal neighborhoods. For instance, popular names are chosen for boys among 42 % of mothers in conservative neighborhoods but among only 35 % of mothers in the most liberal neighborhoods.

To further differentiate social status, ideology, and other influences on name choices, multivariate equations were utilized. The nature of the variables raises a host of complicated methodological questions concerning the spatial autocorrelation of the data and the treatment of the dependent variable as discrete choice sets.Footnote 14 Table 3 lists the results of the model specification that is the most reliable: multinomial logistic regression coefficients from equations estimating the relationship between two of the naming categories (popular and uncommon) and several explanatory variables including mother’s education, neighborhood status (measured by the percent in the census tract with a college degree and the natural log of median household income), neighborhood racial composition, and neighborhood ideology (measured by the voting score described above).Footnote 15 Since the effects of ideology vary considerably by education, interaction terms between education and ideology were also included. As with the tables above, the equations were estimated separately by the mother’s race/ethnicity and the child’s sex.Footnote 16

The results from the multinomial logistic regressions provide a somewhat more complex picture about the relationship between social status and naming practices. As in the cross-tabulations, the regressions show that women of higher education generally seek more popular names for their children and are less likely to choose uncommon names. Similarly, the income level of the mother’s neighborhood also corresponds to naming practices in pattern similar to education: white, Latina, and black mothers are all less likely to choose uncommon names as their neighborhood incomes rise; and, with the exception of black mothers, they are also more likely to choose popular names with greater neighborhood income. These patterns deviate, however, when status is measured by virtue of neighborhood education: white mothers in better educated neighborhoods are more likely, ceteris paribus, to choose uncommon names for boys and less likely to choose popular names for boys or girls; Latina mothers in better-educated neighborhoods are more likely to choose both popular and uncommon names for boys and are more likely to choose popular names for girls. These education effects are not evident for black mothers who are no more or less likely to choose popular or uncommon girl names as the percent of college educated adults in their neighborhood increases.Footnote 17

The mothers’ neighborhood racial composition also relates to their naming choices.Footnote 18 Whites are more likely to give uncommon names to girls and boys and less likely to give popular names as the percentage of whites in their neighborhood increases. For Latina mothers, the opposite relationship occurs—as the percent of Latinos in their neighborhood increases, they are less likely to give boys uncommon names and more likely to give them popular names, although this trend is less consistent for girls. Black mothers are more likely to give both boys and girls uncommon names and less likely to give boys popular names as the black percentage in their neighborhood increases, although these effects taper off after the neighborhood is over 50 % black. These findings reflect more complex and ethnically driven patterns of social distinction that are beyond this paper’s scope to examine in further detail.

Finally, the ideology of white mothers’ neighborhoods also relates to their naming behaviors, although this varies in proportion to their education level. To better illustrate these effects, Fig. 1 depicts the predicted probability, derived from the binomial general additive models (GAM) with the same predictors as in Table 3, that the daughter or son of a white mother will have either an uncommon or a popular birth name relative to the ideological liberalness of the mother’s neighborhood differentiated by the mothers’ education.Footnote 19 The GAM regression models demonstrate that the ideological effects on naming behavior are largely found among college-educated white mothers. Ceteris paribus, a college-educated white mother is twice as likely to give her child an uncommon name if she lives in one of the most liberal neighborhoods versus one of the most conservative ones. For this same group, the predicted probability that a boy will be given a popular name drops from 46 % in the most conservative neighborhoods to 37 % in the most liberal ones; for a girl, a similar predicted probability of a popular name drops from 38 to 30 %.Footnote 20

The effects of ideology on these naming patterns attenuate as the mother’s education declines. Among white mothers with only some college education, the likelihood of choosing an uncommon name increases by about 5 % points as their neighborhood ideology moves from the conservative to liberal extremes and the likelihood they choose a popular name drops by 6 % age points. Among white mothers with less than 13 years of education, the effects of neighborhood ideology almost disappear entirely. For this group, there are no statistically significant differences in the likelihood of choosing an uncommon name by neighborhood ideology and relatively small differences in the diminished likelihood of choosing a popular name as the neighborhood grows more liberal.

These findings indicate that, among more educated white women, ideology clearly relates to their choice of birth names. As indicated above, we have three hypotheses for why this may be so. The first is that ideology is picking up religious differences; in particular, conservatives may be more likely to be invoking Biblical names which tend to be more common. However, when we construct a variable measuring Biblical names, we find no relationship with ideology.Footnote 21 White mothers in liberal neighborhoods are just as likely to give their children Biblical names like Jacob, Daniel, Hannah, or Sarah as mothers in conservative neighborhoods.

The second hypothesis is that people who identify as liberal or conservative may hold other core values or social identities that get expressed in their name choices. Given the limited number of variables available and the wide array of values and social identities associated with liberalism and conservatism, this hypothesis is difficult to adequately test with these data. There is, however, one likely dimension that can be examined: do conservatives choose more traditional names because they have stronger family ties and are more likely to be married? Here the answer is no. The California Birth Records allows for a father to not be indicated and, for white mothers, there were 16,315 records with no father indicated. However this is unrelated to ideology—mothers in liberal neighborhoods were no more likely to have fatherless birth records than mothers in conservative ones. We find no systematic difference in family structure by ideology.

This leaves our third hypothesis—that liberals and conservatives employ different baby names as different types of status signals. Here we find several indicators of support. First, for white and Latina mothers, neighborhood income positively corresponds with choosing more conventional birth names, a pattern that would indicate conventional names are associated with greater economic capital. Meanwhile, neighborhood education negatively corresponds with choosing a conventional name. Despite their greater economic status, mothers in better educated neighborhoods are more likely to choose uncommon names. This suggests that traditional names are less useful for signaling the cultural capital that is presumably valued in a higher educated milieu.

To further test this hypothesis about economic and cultural capital, we examine differences among uncommon names. We compare unique and uncommon birth names to a list of names in the Carnegie Mellon University Pronouncing Dictionary (CMUPD). Table 4 lists the percent of names “unrecognized” in the CMUPD by the mothers’ race/ethnicity, education, and ideology (for educated white mothers).Footnote 22 This variable roughly differentiates names that are conventional yet uncommon from those that either have unconventional spellings or are entirely fabricated. Although this variable will not differentiate more obscure names (e.g., “Beckett” or “Sojourner”) from common-use words appropriated as names (e.g., “Pepsi” or “Heaven”), it will differentiate them from conventional names with odd spellings (e.g., “Jazzmyne”) or names that are entirely novel (e.g., “Berjo”).

Liberal, educated whites are more likely to choose uncommon names than their conservative counterparts, but also they are more likely to choose different types of uncommon names than less educated women of all races. Among women with less education and among black and Latina mothers, a very high percent choose “unrecognized” names when they give their child a unique or uncommon name. For example, among black mothers, 90 % of uncommon names are “unrecognized” and, for Latina mothers, 85 % of uncommon names are “unrecognized.” For both groups, over 99 % of unique names are “unrecognized.” But among white mothers, only 52 % of uncommon names are unrecognized and 78 % of unique names are unrecognized. Although more educated black and Latina mothers are slightly less likely to choose “unrecognized” names, there are much larger differences by education among white mothers. Among the least educated white mothers, 59 % of uncommon names and 81 of unique names are “unrecognized” while amongst those with a college degree only 46 of uncommon names and 75 of unique names are.Footnote 23

For the most educated white mothers, an ideological difference is also evident: only 70 % of unique names chosen by highly educated white mothers living in the most liberal neighborhoods are “unrecognized” compared to 77 % for those in the most conservative neighborhoods. These differences highlight the importance of cultural obscure references as the source of birth names for liberal elites. For whites in general and for liberal, educated whites in particular, the mechanism of social distinction in picking an unusual or unique name is often from its cultural obscurity rather than its uniqueness.

Ideology is also related to the phonetic structure of birth names. For each name, we constructed a Male Gender Score, a metric of how predominant each phoneme within the name is among all boys’ and girls’ names.Footnote 24 As noted above, phonemes (using the Arpanet transcription codes) that are more common in boys’ names include ER (Burt), O (Joe), K (Kurt), G (Gary), and B (Bill); phonemes more common in girls names include AH (Ella), IY (Ellie), and L (Lola). Based on this we can assign Male Gender Scores. Names like Kurt, Dirk, Rocco, Beau, and Gunner have high Male Gender Scores, while names like Liam, Leila, Ely, and Janelle have low Male Gender Scores. We then used the Male Gender Score as a dependent variable in linear mixed model featuring the same covariates used above and random intercepts for voting district. Figure 2 lists the predicted Male Gender Score for both boys and girls by neighborhood ideology. The models’ coefficients are listed in the Appendix.

The equations reveal that college-educated white mothers choose names with more feminine phonemes as their neighborhood becomes more liberal. These ideological differences occur for both boys’ and girls’ names. For example, the equations predict that, on average, boys’ names in the most conservative neighborhoods will have a Male Gendered Score of .48 compared to .44 for boys from the most liberal neighborhoods; for girls’ names, these same scores drop from approximately .38–.35 by neighborhood ideology. The only exception to this trend is among less-educated white mothers, whose name choices for boys become slightly more masculine, even as their neighborhood ideology becomes more liberal. Nevertheless, for the remaining groups, we find that the relationship between birth names and ideology works similarly to patterns listed above: mothers from more liberal neighborhoods tend to distinctive types of names, in this case based on their phonetic structure.

To further illustrate these phonetic trends, we examine differences relative to four of the most popular, highly gendered phonemes: K, L, IY, and AH.Footnote 25 Figure 3 depicts predicted probabilities from a generalized additive logistic model of a name having one of these phonemes by the ideology of the mother’s neighborhood, differentiated by sex, and whether the name was popular, with controls for neighborhood income, education, and racial composition. For illustrative purposes, we also limit our analysis here to mothers with some college education, where the effects of ideology are greatest.Footnote 26

Among the four most popular, gendered phonemes, the results generally echo the trends found above: the baby names chosen by educated, white mothers tend to have more feminine phonemes and fewer masculine phonemes as their neighborhoods become more liberal. For example, the equations predict that a mother in a conservative neighborhood, if she chooses a non-popular name, has an 18 % probability of picking a name that starts with a “hard C” (K) sound, but this drops to just over 12 % in the most liberal neighborhood, a difference that is nearly identical for girls. Girls from the most liberal neighborhoods have nearly a 10 % point greater likelihood of receiving a name ending in a schwa phoneme compared to their conservative counterparts. Boys from liberal neighborhoods are about 5 % points more likely to have names that contain an L phoneme and are slightly more likely to have their names end with an “ee” (IY) sound. Indeed, the only phoneme that runs contrary to this pattern is the IY phoneme among girls: those from liberal neighborhoods are slightly less likely to have names ending with this phoneme. Nevertheless, for most of these popular phonemes, feminine sounds are more likely to be evident in the birth names chosen by mothers in liberal neighborhoods, regardless of their child’s sex.

Two important methodological considerations regarding these findings merit further discussion. The first concerns the accuracy of the summary index of voting patterns as a measure of ideology. Ideology is a complex phenomenon and any measure, whether it is self-reported ideology or indices of policy preference, has its own inadequacies (Wood and Oliver 2012). That caveat noted, there are reasons to believe the voting index is still a good indicator of neighborhood ideology—it has a high level of inter-item reliability (Chronbach’s alpha = .903) and a normal distribution across the scale (See “Appendix 4” section). Given our interest in ideology and social signaling, a person’s ideological context may itself be relevant.

In fact, an alternative hypothesis may be that we are measuring fewer effects of individual ideology and larger effects of social contagion. Perhaps mothers are not drawing from their own ideologies but are simply being sensitive to cues from their social environments. In this case, liberal social environments may trigger incentives for different names than conservative ones. Although such network effects are highly likely, there are three reasons why we believe the voting index is also a reliable, if imprecise, measure of individual ideology. First, Americans are highly segregated by race, social class, and partisanship, particularly at the level of a voting precinct (Huckfeldt and Sprague 1987), thus there is a high probability that the mother’s ideology is consistent with the voting patterns of her precinct, particularly at the ends of the ideological spectrum. Second, because the effects of ideology are most evident amongst the educated, it is also likely that the neighborhood measures of ideology are capturing individual-level differences (Wood and Oliver 2012). If social contagion effects were more prominent, we would expect the effects of neighborhood ideology to be less sensitive to the mother’s educational level. Finally, the equations also control for neighborhood income and education, which presumably also capture many network effects. We don’t mean to imply that our results are completely immune to contagion effects, but simply that the results are more consistent with an individual-level interpretation.

Second, these results, if anything, probably understate the relationship between ideology and birth names. Birth names are subject to a large number of strong, external influences, ranging from ethnic traditions to religion to familial obligations. Yet, despite the power of these forces for constraining name choices, large and predictable differences in birth names still exist across the mothers’ political environments, especially for educated whites. For white mothers, the differences in choosing an uncommon name across the ideological measure are as great as the differences by individual level education and are larger than differences in neighborhood income or education. If more precise measures of a mother’s ideology were available, we suspect that even larger differences in name choices would be apparent.

Conclusion

Birth names reveal many patterns regarding class, social status, and ideology in the American public. Although previous studies have found differences in birth names by race and class (Lieberson 2000; Levitt and Dubner 2005), this is the first research to our knowledge that shows how these factors interact. Mothers who are better educated and live in wealthier neighborhoods tend to favor more popular names for their children, while less educated, poorer mothers are more likely to choose unconventional names or fabricate names. These trends are more pronounced among African Americans but still evident across all racial and ethnic groups. This is also the first research that shows how ideology relates to naming practices. Among America’s white elites, liberals are more likely to choose uncommon, culturally obscure names while conservatives favor more popular names. The sounds of names chosen also relates strongly to the ideology of educated whites. Liberals favor more feminine sounding birth names, particularly the “L” sound in boys’ names, an “A” ending for girls’ names; conservatives are far more likely to choose names, for both boys and girls, that begin with a “hard C” sound.

Although birth names may seem like a rather esoteric subject of inquiry, these findings offer contributions to two questions within the social sciences. The first is a long-standing debate about the determinants of consumer taste and the mechanisms of social differentiation in contemporary America. Social theorists have long debated how society’s upper strata distinguish themselves from those below, particularly about the specific mechanisms of differentiation. The results here suggest that much of these signaling practices depend on the availability of such resources: individuals with more economic capital than cultural capital will rely mostly on explicit displays of luxury and wealth to highlight their social position; individuals with both high economic and cultural capital will utilize more traditional and refined mechanisms of social distinction; and where cultural capital is high and economic capital low, individuals will invoke more esoteric or international cultural references in their consumer choices. Not surprisingly, these differences are also related to ideology. Liberals tend to favor status signals that are high in cultural capital and low in economic capital, a factor related to their relative economic position and concordant with many tendencies within the American liberal tradition. Conservatives are more likely to utilize signs of economic capital in their consumer behavior, a factor of their higher income-to-education ratio and the traditionalism and tolerance of economic inequality pervasive in conservative thought.

This paper’s second contribution is toward the enormous public discourse about ideological fragmentation in America. Over the past decade, there has been much speculation about whether the ideological fragmentation of elected representatives is also evident in the mass public. These results provide fodder for both sides. If one considers the choice of a child’s name one of the most significant markers of identity (which we do), then these findings suggest that ideology is a power influence on a wide range of ostensibly non-political behaviors. Yet, at the same time, the effects of ideology are mostly confined to the better educated echelons of white, American society. As with other forms of public opinion, the effects of ideology on baby names are far less strong among less educated and minority populations. So, yes Americans are divided by ideology, but it is an ideological division that is most evident among its educated, white population.

Together, both debates suggest that popular generalizations about “Red versus Blue” states need reconsideration. Tropes like “liberals drive Volvos and conservatives drive pickup trucks” are inaccurate, not because ideology is irrelevant to consumer behavior, but because such statements conflate ideology and social class. It is more likely that “liberals drive Volvos and conservatives drive Mercedes Benzes” with the poor and working classes, who are generally less ideological, driving pickup trucks or compact cars. Yet, characterizations of liberals as a “cultural elite” or conservatives as an “economic elite” are not entirely off-base either. As we see in patterns of baby names, liberal elites use esoteric cultural references to demonstrate their elevated social position just as conservatives invoke traditional signals of wealth and affluence. Instead of divides between “Red and Blue states,” it is more accurate to say that America is divided not just by “Red and Blue elites,” but also in the ways these elites seek to differentiate themselves from the largely “purple” masses.

Notes

The term “cultural capital” has a wide range of usages and meanings. We use it as defined by Lamont and Lareau (1988) as “widely shared, high status cultural signals (attitudes, preferences, formal knowledge, behaviors, goods and credentials) used for social and cultural exclusion.” (p.156).

The term ideology has a host of connotations from loose systems of belief to myth to even “consumerism” itself. For the purposes of this paper, ideology is conceptualized as set of logically coherent ideas about the proper ordering of collective activity that constrain opinion and dictate specific courses of action (Mullins 1972).

For purposes of expedience, this paper will examine only ideology as it expressed in a liberal-conservative continuum where attitudes are organized primarily by concerns with the scope of government in the distribution of resources and the advancement of traditional and moralistic concerns (Kinder 1983, Gerring 1997). Many smaller ideologies, such as environmentalism, socialism, or certain religiously inspired ideologies have explicit conceptions of appropriate consumption practices.

One can, for instance, categorize names relative to Biblical or nature references, emotions or specific values, ethno-nationalist sentiments, culture (both highbrow and low), historical figures, etc.

Because of inconsistencies and inaccuracies in the birth record data, particularly in the annotation of the addresses, we were only able to identify locations for 478,355 of the 545,018 recorded births. However, there are no significant differences in the distribution of variables between these two samples. Thus we have no reason to think that these errors are systematically distributed or that these missing cases are distorting our findings.

For a full description of the database, see http://swdb.berkeley.edu/index.html.

Because of variations in spellings in common sounding names (e.g., Madison, Madyson, Madisun, Madysyn, etc.) these variables somewhat overstate the phonetic variations in names.

There are other vowel sounds that are more predominant in Boys’ names, like UH and AW, but these have a very low frequency in names.

White includes mothers whose race was coded as white but whose ethnicity was listed as “American,” “Caucasian,” or “White” but not any other nationality. Latina includes those mothers whose race is coded as white and who identify a Hispanic ethnicity (e.g., Mexican, Puerto Rican, Chicano, etc.). Excluded from this list are 11,199 mothers who are identified as white but provide some other ethnicity (e.g., Armenian, Russian, Swedish). This measure was meant to exclude of European extraction who may be immigrants or come from non-English languages and thus have culturally idiosyncratic naming practices. This “ethnic white” category included 7894 birth mothers or roughly 1.4 percent of the sample. Excluded from the sample are also 2972 birth mothers whose race was identified as American Indian. There were 18,485 records for which there was either no recorded race/ethnicity or that did not fit within these four categories and 15,152 cases with no education level recorded. Because the overwhelming majority of cases missing data on education were also missing data on race, this left only 19,161 cases with no data. In total, there are 26,780 cases excluded because of missing data or because of ethnicity or race that does not fit easily within the above four categories.

Proposition 61 was a statewide $750 million bond measure to provide funding for children’s hospitals that passed with 58 percent of the vote; Proposition 63 increased the tax rate on residents making over $1 million a year by 1 percent in order to fund county mental health services and it passed with 53 percent of the vote; Proposition 71 made stem cell research a constitutional right and authorized the sale of $3 billion worth of general obligation bonds to subsidize stem cell research and passed with 59 percent of the vote.

Precincts with ideology scores above .8 or below .25 typically have less than 30 voters.

The data provided by the state mistakenly identified mothers with Chinese names as Vietnamese and grouped these two nationalities together. In addition, the tremendous differences between Korean, Japanese, Filipino, and other nationalities cast doubt on whether Asian is a meaningful unifying category. Because the relative proportions of each of these nationalities is so much smaller than other groups and because each is subject to distinct cultural and linguistic idiosyncrasies in naming practices, they are excluded from further analysis.

The dividing points for median household income, percent with a college degree, and ideology scales conform largely to the quintile and sextile distributions in the entire sample. This leaves a few skewed distributions, i.e., there are a very small number of blacks in the most conservative voting precincts.

A Moran’s I test for spatial autocorrelation for the models for each racial group and child gender failed to yield a single significant coefficient. The results from the Moran’s I test are listed in the Appendix.

The dependent variable is comprised of three categories: popular name, uncommon name, and all other names. The excluded category in the regression tables are other names.

A reviewer cautioned that our socioeconomics controls might be capturing the separate effects of single mothers, who are likely subject to differing naming imperatives given the absence of a father in the naming process. Accordingly, this might induce new partial correlations between ideology and baby names. To test this possibility, we modeled the probability that a child’s birth record would omit a father’s name (an indicator for single mothers) as a function socioeconomics and ideology. As expected, there were very large socioeconomic effects, but no ideological differences.

These results are largely a function of the relatively low number of popular names chosen by black mothers for their girls.

Because of differences in distributions of populations among whites, Latinos, and blacks, different model specifications were used to measure racial and ethnic composition in the logistic equations. For Latinos, a measure of English speaking among households in the census tract was included to differentiate between ethnic and linguistic effects that might be compounded in the measure of percent Latino. Because of their relatively lower population sizes and high levels of segregation, the racial composition of the percent black in the neighborhood was measured with a quadratic term.

Because there are so few observations from the small number of precincts with ideology scores below .3 or above .7, the confidence intervals at these poles from the GAM models become so large and the results are uninterpretable. Consequently, we have truncated the illustration to the parts of the ideological scale where the GAM model can derive meaningful statistics.

Given available data, we are only able to measure mothers’ socioeconomics and ideology at the district level. This obviously induces challenges of dependence between units within common districts. To address this, the GAM reported in the paper cluster standard errors at the electoral district level. We have separately estimated a redundant set of hierarchical GAM with random effects at the district level; however, the negligible differences between the estimated coefficients suggested we should retain the GAM with clustered errors, given their ease of interpretation.

We created a variable for the top twenty Biblical names for both boys and girls and used this as a dependent variable with the same model specifications used in Table 3. In no instance did we find a statistically significant relationship between ideology and the use of a Biblical name. To be more exhaustive, we then constructed a variable which includes all biblical names recorded in Wikipedia (which includes almost 2600 unique names). This test also showed no ideological relationship. Similarly, a reviewer suggested that a relationship between ideology and baby naming patterns among Hispanic mothers might reflect their desire to use an Aztec/Mayan name. After exploiting publicly available names of Aztec names, we separately modeled the choice of these names as a function of ideology, without finding any relationship.

At a reviewer’s suggestions, we tested the possibility that the effect of ideology would interact with mothers’ reported ethnicity. These interactions were consistently insignificant, and trivially small, indicating that a single ideological coefficient is an adequate representation of the population relationship.

Some of these educational differences may also be the consequence of higher illiteracy thus generating names that are spelled phonetically relative to variations in speech patterns (e.g., “Keef,” “Jazzmin” etc.).

To calculate the Male Gender score, we first estimated a proportion score: the number of times that name was given to a boy born in California during 2004, divided by the total number of times a name was awarded. Names like Isabella and Natalie, for instance, were chosen more than 2000 times each in 2004, but never awarded to boys, so their proportion is equal to 0. A popular androgynous name is Alexis, which was awarded 2751 times, with 1248 recipients being boys—giving this name a ratio of .453. Next, the regularity of the phonemes in each name is calculated to provide a gender-phoneme ratio score for that phoneme. This is similar (although oppositely scored) to the gender ratio of phonemes illustrated in Table 5 in the Appendix. For instance, AH0 (the middle phoneme in “hut”) is predominant in girls’ names and has a gender-phoneme ratio score of .28; AW0 (the middle phoneme in “cow”), a very uncommon phoneme, appears almost exclusively in boys’ names, and accordingly has a ratio score of .99. For each name, we then take the mean of all the gender-phoneme ratio scores in each name, and rescale it from 0 to 1 for a final Male Gender Score for each name.

When looking at specific phonemes, we also considered their specific position in the name.

The effects of neighborhood ideology on phoneme choice among less educated mothers are usually insignificant, as we would predict.

References

Abramowitz, A., & Saunders, K. (2008). Is polarization a myth? The Journal of Politics, 70, 542–555.

Bagwell, L., & Bernheim, B. (1996). Veblen effects in a theory of conspicuous consumption. The American Economic Review, 86, 349–373.

Bertrand, M., & Mulainathan, S. (2004). Are Emily and Greg more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination. American Economic Review, 94, 991.

Bishop, B., & Cushing, R. (2008). The big sort: Why the clustering of like minded America is tearing us apart. New York: Houghton Mifflin Co.

Blumer, H. (1969). Fashion: From class differentiation to social selection. The Sociological Quarterly, 10, 275–291.

Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgment of taste. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Brint, S. (1985). The political attitudes of professionals. Annual Review of Sociology, 11, 389–414.

Brooks, D. (2004). On paradise drive: How we live now and always have. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Bryson, B. (1996). Anything but heavy metal: Symbolic exclusion and musical dislikes. American Sociological Review, 61, 884–899.

Cahn, N., & Carbone, J. (2010). Red families versus blue families: Legal polarization and the creation of culture. New York: Oxford University Press.

Cassidy, K., Kelly, M., & Sharoni, L. (1999). Inferring gender from name phonology. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 123, 362–381.

Conover, P. J., & Feldman, S. (1981). The origins and meaning of liberal/conservative self-identifications. American Journal of Political Science, 25(4), 617–645.

Converse, P. (1964). The nature of belief systems in mass publics. New York: Free Press.

Corneo, G., & Jeanne, O. (1997). On relative wealth and the optimality of growth. Economics Letters, 54, 87–92.

Cutler, A., McQueen, J., & Robinson, K. (1990). Elizabeth and John: Sound patterns of men’s and women’s names. Journal of Linguistics, 26, 471–482.

Edwards, R., & Caballero, C. (2008). What’s in a Name? An exploration of the significance of personal naming of ‘mixed’ children for parents from different racial, ethnic, and faith backgrounds. The Sociological Review., 56, 39–60.

Ellis, C., & Stimson, J. (2012). Ideology in America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Feldman, S. (1988). Structure and consistency in public opinion: The role of core beliefs and values. American Journal of Political Science, 32(2), 416–440.

Figlio, D. (2005). Names, expectations and the black-white test score gap. NBER Working Paper No. 11195.

Fiorina, M., Abrams, S., & Pope, J. (2010). Culture war? The myth of a polarized America. (3rd Edition). Longman.

Gerring, J. (1997). Ideology: A definitional analysis. Political Research Quarterly, 957–994.

Gross, N., Medvetz, T., & Russell, R. (2011). The contemporary American conservative movement. Annual Review of Sociology, 37, 325–354.

Gurova, O. (2006). Ideology and consumption in the Soviet Union: From asceticism to the legitimating of consumer goods. Anthropology of East Europe Review, 24, 91–99.

Hamby, A. (2006). Liberalism and its challengers: From FDR to bush. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hartz, L. (1995). The liberal tradition in America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt: The liberal tradition in America.

Holt, D. (1998). Does cultural capital structure american consumption? Journal of Consumer Research, 25, 1–25.

Huckfeldt, R., & Sprague, J. (1987). Networks in context: The social flow of political information. American Political Science Review, 81, 1197–1216.

Jost, J., Federico, C., & Napier, J. (2009). Political ideology: Its structure, functions, and elective affinities. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 307–333.

Kinder, D. R. (1983). Diversity and complexity in American public opinion. Political science: The state of the discipline, 389–425.

Kozinets, R., & Handelman, J. (2004). Adversaries of Consumption: consumer movements, activism, and ideology. Journal of Consumer Research, 31, 691–711.

Lakoff, G. (2002). Moral politics: How liberals and conservatives think. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lamont, M., & Lareau, A. (1988). Cultural capital: Allusions, gaps, and glissandos in recent theoretical development. Sociological Theory, 6, 153–168.

Levitt, S., & Dubner, S. (2005). Freakonomics: A rogue economist explores the hidden side of everything. London: Harper Collins.

Lieberson, S. (2000). A matter of taste: How names, fashions, and culture change. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Lieberson, S., & Mikelson, K. (1995). Distinctive African American names: An experimental, historical, and linguistic analysis of innovation. American Sociological Review, 60, 928–946.

Lipset, S. (1997). American exceptionalism: A double edged sword. W. W: Norton.

Mullins, W. A. (1972). On the concept of ideology in political science. American Political Science Review, 66(02), 498–510.

Murray, C. (2012). Coming apart: The state of White America. New York: Crown Forum.

Nunberg, G. (2006). Talking right. New York: Public Affairs.

Peterson, R., & Kern, R. (1996). Changing highbrow taste: From snob to omnivore. American Sociological Review, 61, 900–907.

Poole, K., & Rosenthal, H. (1997). Congress: A political economic history of roll call voting. New York: Oxford University Press.

Veblen, T. (1899). The theory of the leisure class—an economic study of institutions. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

Whissell, C. (2001). Cues to referent gender in randomly constructed names. Perpetual and Motor Skill, 93, 856–858.

Wood, T., & Oliver, J. (2012). Towards a more reliable implementation of ideology in Public Opinion Research. Oxford: Public Opinion Quarterly.

Yoganarasimhan, H. (2012). Identifying the presence and cause of fashion cycles in the choice of given names. Working Paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

See Table 5.

Appendix 2

See Table 6.

Appendix 3: Formula for computation of name gender scores

First we define Θ j for all j unique names awarded in California during 2004.

For each phoneme p i,k (where i indexes the number of unique phonemes in the ARPAbet), the mean Θ j for each phoneme is given by and k indexes the location of a phoneme in a particular name, and for each name n j , we compute a name gender score (Gj) as follows.

Appendix 4

See Fig. 4.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Oliver, J.E., Wood, T. & Bass, A. Liberellas Versus Konservatives: Social Status, Ideology, and Birth Names in the United States. Polit Behav 38, 55–81 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-015-9306-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-015-9306-8