Abstract

Do the political values of the general public form a coherent system? What might be the source of coherence? We view political values as expressions, in the political domain, of more basic personal values. Basic personal values (e.g., security, achievement, benevolence, hedonism) are organized on a circular continuum that reflects their conflicting and compatible motivations. We theorize that this circular motivational structure also gives coherence to political values. We assess this theorizing with data from 15 countries, using eight core political values (e.g., free enterprise, law and order) and ten basic personal values. We specify the underlying basic values expected to promote or oppose each political value. We offer different hypotheses for the 12 non-communist and three post-communist countries studied, where the political context suggests different meanings of a basic or political value. Correlation and regression analyses support almost all hypotheses. Moreover, basic values account for substantially more variance in political values than age, gender, education, and income. Multidimensional scaling analyses demonstrate graphically how the circular motivational continuum of basic personal values structures relations among core political values. This study strengthens the assumption that individual differences in basic personal values play a critical role in political thought.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Is there a meaningful structure to the political thought of the general public? That is, do the political attitudes and values of the general public form a coherent system? If so, what accounts for this structure and gives political values their coherence? We seek to answer these questions in a cross-national context. We argue that the motivational structure of basic personal values serves as the source of coherence for the core political values of the public. Moreover, this is the case across different countries and political systems, with only minor variations.

Popular views hold that the single left–right or liberal-conservative ideological dimension structures political thought and reduces the complexity of political information (e.g., Conover and Feldman 1981; Jacoby 1995). Another single dimension is materialism-postmaterialism (Inglehart 1997). It is unlikely, however, that a single ideological dimension can organize political attitudes (Benoit and Laver 2006; Kinder 1998). For this purpose, multidimensional conceptions of ideology have been suggested (e.g., Kerlinger 1984) and are needed (Ashton et al. 2005). They are especially necessary for understanding the organization of the variety of political attitudes and values in the discourse of different countries (Gunther et al. 2007).

Many empirical studies have examined the political attitudes of the general public and the way these attitudes relate to one another (e.g., Evans et al. 1996; Feldman 1988; Zaller 1992). There have been few systematic attempts, however, to investigate what underlies the varied political attitudes of the electorate (for exceptions, see Ashton et al. 2005; Peffley and Hurwitz 1985). Feldman (2003: 479) noted that “one potentially valuable approach to the attitude organization problem that has not received sufficient attention … is based on the value construct.” Many have assigned a central role to values as organizers of political attitudes (e.g., Gunther and Kuan 2007; Rokeach 1973). However, empirical studies of the role of values are few in number and these have largely focused on a limited set of values (e.g., Braithwaite 1997; Rokeach 1973). They have failed to consider how political attitudes relate to a comprehensive system of basic values (Feldman 2003).

The validation of a theory that identifies a comprehensive set of basic personal values (Schwartz 1992, 1994) makes it possible to relate political attitudes to the whole system of basic values. Several hundred studies, with both convenience and representative samples from all over the world, support a near universal motivational structure of relations among the basic values (e.g., Fontaine et al. 2008; Schwartz 1994; Bilsky et al. 2011). We apply this near universal structure of basic values to understand the organization of political attitudes and values.

A recent study in Italy (Schwartz et al. 2010) examined the possibility that the motivational structure of the ten basic values in the Schwartz (1992) value theory underlies and gives coherence to core political values. Their findings largely supported this possibility for Italy. But are their findings generalizable beyond Italy to countries with different political histories and systems? The reasoning we will present suggests that the motivational structure of basic values does indeed give coherence to political valuesFootnote 1 across political contexts. Moreover, we argue that particular political values express the same basic values across contexts.

We do expect some variation, however. This should occur if the political history of a country has imbued a particular political value with a meaning different from that in most other countries. For example, the experience of communist rule may have imbued ‘equality’ or ‘free enterprise’ with connotations for citizens in post-communist countries that differ from their connotations in West European countries. The current study examines relations of basic personal values to core political values in 15 countries. Thus, we test a set of theory-based hypotheses about the way that individuals’ basic personal values are expressed in their political values and thereby give coherence to them, and we do so in a variety of political contexts. These hypotheses also specify likely variations due to the political history of post-communist countries. Before generating the set of hypotheses, we first explicate the core political values we studied, the relevant aspects of the theory of basic personal values, and the distinctions between basic personal values and political values.

Core Political Values

Political scientists refer to attitudes in the political domain such as egalitarianism, civil liberties, ethnocentrism, and limited government as ‘core political values’ (e.g., Goren 2005; Hurwitz and Peffley 1987). McCann (1997) defined core political values as overarching normative principles and belief assumptions about government, citizenship, and society. They help people to take positions in an otherwise confusing political environment, binding together more specific attitudes and beliefs (Converse 1964). Core political values underlie specific attitudes, preferences, and evaluations in the sphere of politics (Feldman 1988; Hurwitz and Peffley 1987). Political scientists typically measure core political values by asking people how much they agree or disagree with prescriptions for how government or society should function.

There is neither a clear consensus regarding the number and content of core political values in modern democracies nor a theory to help identify them. Nonetheless, the political values identified by different theorists (e.g., Feldman 1988; McCann 1997; Heath et al. 1985; Goren 2005; Jacoby 2006; Kinder and Sears 1985) overlap to a great extent. Schwartz et al. (2010) selected six constructs that encompass the political values mentioned in the above six sources. We included these six core values in all 15 countries. In countries where our collaborators deemed them relevant, we added two political attitudes (toward military intervention and immigration) that Schwartz et al. (2010) had included because they were prominent in the 2006 Italian election. To simplify, we refer to eight core political values, though the last two are more specific political attitudes. We define these political values below:

-

Traditional morality: society should protect traditional religious, moral, and family values.

-

Blind patriotism: people should support and never criticize their country.

-

Law and order: government should forbid disruptive activities and enforce obedience to law.

-

Free enterprise: government should not be involved in the economy.

-

Equality: society should distribute opportunities and resources equally.

-

Civil liberties: everyone should be free to act and think as they deem most appropriate.

-

Foreign military intervention: nations should use military means to deal with international problems if necessary.

-

Accepting immigrants: foreign immigrants contribute positively to our country.

Basic Personal Values

Basic personal values are cognitive representations of individuals’ broad goals that apply across specific situations (Rokeach 1973; Schwartz 1992). Basic personal values serve as standards for judging all kinds of behavior, events, and people. They vary in terms of their importance as guiding principles in life. The Schwartz (1992) value theory that guides this research identifies ten broad personal values, each defined in terms of the distinct motivational goals it expresses:

-

Power: control or dominance over people and resources.

-

Achievement: personal success through demonstrating competence according to social standards.

-

Hedonism: pleasure and sensuous gratification for oneself.

-

Stimulation: excitement, novelty, and challenge in life.

-

Self-Direction: independent thought and action—choosing, creating, exploring.

-

Universalism: understanding, appreciation, tolerance, and protection for the welfare of all people and for nature.

-

Benevolence: preservation and enhancement of the welfare of people with whom one is in frequent personal contact.

-

Tradition: respect, commitment and acceptance of the customs and ideas that traditional culture or religion provide.

-

Conformity: restraint of actions, inclinations, and impulses likely to upset or harm others and violate social expectations or norms.

-

Security: safety, harmony, and stability of society, of relationships, and of self.

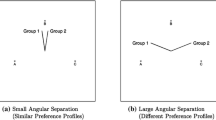

The theory further specifies the circular structure of relations among the values shown in Fig. 1. This structure is a motivational continuum that reflects the compatibility and conflict among different values. The closer any two values on the circle, the more compatible their motivations and therefore the more likely it is that they can be attained through the same action or expressed through the same attitude. The more distant any two values, the more conflicting their motivations, hence the less possible to attain them through the same action or express them in the same attitude. This circular structure of values means that any behavior or attitude that is especially congruent with one basic value (e.g., military intervention with power) should also be congruent with the adjacent values (security and achievement) but conflict with the opposing values (universalism, benevolence, and self-direction). Thus, the whole integrated structure of values relates systematically to other variables.

We note additional sources of the circular structure of basic personal values that aid in developing hypotheses about the ways basic values are expressed in core political values. Values in the bottom half of the circle (Fig. 1) are based in the need to avoid or control anxiety and threat and to protect the self (Schwartz 2006, 2010). Conservation values (bottom left) emphasize avoiding conflict, unpredictability, and change by submission and passive acceptance of the status quo. Self-enhancement values (bottom right) emphasize overcoming possible sources of anxiety by gaining dominance or admiration. In contrast, values in the top half of the circle are relatively anxiety free, expressing growth and self-expansion. Self-transcendence values (top left) emphasize promoting the welfare of others. Openness to change values (top right) emphasize autonomous, self-expressive experience.

Another way to think about the circle of basic personal values is to see them as arrayed on the two dimensions shown in Fig. 1. The poles of one dimension are openness to change versus conservation values. The former encourage independent thought, feeling, and action, and receptiveness to change whereas the latter call for submissive self-restriction, preserving traditional practices, and protecting stability. The poles of a second dimension are self-transcendence versus self-enhancement values. The former emphasize accepting others as equals and concern for their welfare whereas the latter encourage pursuing one’s own success and dominance over others. Hedonism shares elements of both self-enhancement and openness to change values, but it is closer to the latter in most societies (Schwartz 2006). Schwartz (1992) labeled the four poles of the dimensions ‘higher order values’.

Partially overlapping with the oppositions in the Schwartz value circle are the orthogonal dimensions of conservatism and liberalism identified by Kerlinger (1984). His conservatism dimension refers to an emphasis on conservation values and little salience of openness values as referents. His liberal dimension refers to an emphasis on universalism and self-direction values with little salience of conservation.

Distinguishing Between Basic Personal Values and Core Political Values

Basic personal values and core political values are distinct both conceptually and in the ways they are typically measured. Value theorists define personal ‘values’ as the important goals one pursues, the guiding principles in one’s own life (Hitlin and Piliavin 2004; Rohan 2000; Rokeach 1973; Schwartz 1992). In contrast, core political values are better seen as attitudes, beliefs, or preferences about the ways government, citizenship, and society should function. Basic personal values vary and are typically measured as the importance of goals that people pursue for themselves. Core political values vary and are typically measured as the preference for or agreement of people with policies and practices of governments and societies. They do not refer to people’s goals for themselves.

Basic personal values find expression in all domains of daily life. For example, basic personal values have successfully predicted individual differences in behavior and attitudes in such diverse domains as consumer choice (Pepper et al. 2009), creativity (Dollinger et al. 2007), hunting (Daigle et al. 2002), music (Gardikiotis and Baltzis 2012), interpersonal violence (Knafo et al. 2008), medical specialties (Schubot et al. 1995), preferences for relationship partners (Goodwin and Tinker 2002), religiosity (Saroglou et al. 2004), sports (Lee et al. 2008), and vocational interests (Sagiv 2002). Basic personal values underlie and find expression in the attitudes and behaviors specific to each of these and other life domains. Basic personal values are more abstract and context free than the attitudes which express them in the various life domains. Core political values express basic values in the domain of politics. They are more concrete and tied to political contexts.

Hypotheses

Following Schwartz et al. (2010), we postulate that basic personal values underlie and give coherence to core political values. People tend to favor ideologies or policies that can promote their important basic values in any given societal context. They tend to oppose ideologies and policies that threaten or frustrate attainment of their important basic values in that context. People who attribute high priority to security and power values, for example, tend to favor nationalist policies because they seemingly promise greater security and they express power goals. People who attribute high priority to universalism values tend to oppose nationalist policies because nationalism gives less weight to the equality and dignity of those who are not members of the nation.

As noted, the theory of basic values specifies an integrated structure of motivationally compatible and conflicting relations among the ten values (Fig. 1). This structure enables us to hypothesize how the expression of basic personal values in political values leads to an integrated, coherent system of relations among core political values. We propose that the same circular motivational structure that organizes relations among basic personal values also organizes and gives coherence to core political values. Thus, the motivational structure of basic personal values is the source of coherence for core political values. Associations of core political values with one another and with basic values should therefore reflect the motivational oppositions and compatibilities among basic values. This implies that each political value should relate positively to a set of basic values on one side of the motivational circle and negatively to a set of basic values on the opposite side of the circle.

We base the hypotheses that specify the basic personal values that underlie each political value on hypotheses in Schwartz et al. (2010). However, we modify these hypotheses as necessary if the political context in particular countries suggests a variation in the meaning of a basic value or of a political value. We ask whether each political value expresses or promotes attainment of the defining goals of each basic value or whether it conflicts with the expression and preservation of these goals. For the three conservation values (security, conformity, and tradition), all hypotheses are the same. In some cases, however, it is necessary to specify different hypotheses for the component values of the higher order self-enhancement (power and achievement), openness to change (self-direction, stimulation, and hedonism), and self-transcendence (universalism and benevolence) values.

Our conceptual analyses lead to the following hypotheses regarding the motivationally opposed values that correlate positively and negatively with each political value.Footnote 2 Table 1 summarizes the hypotheses.Footnote 3

Traditional morality

Positive correlations with conservation values because preserving traditional norms, beliefs and modes of behavior provides certainty and avoids change; negative correlations with openness to change and universalism values because an emphasis on traditional morality opposes free, individual choice of how to think and behave and is intolerant of what is new and different; negative correlations with self-enhancement values because the rhetoric of traditional morality opposes putting self-interest ahead of the interests of others.

For the post-communist countries, several reasons lead us to hypothesize positive rather than negative correlations with universalism values. The communist regimes sought to suppress religious traditions and to substitute communism as an alternative ideological basis for morality. This may have created a link between support for traditional morality and opposition to communist rule. With the fall of communist regimes, support for traditional morality may have become a way to express the motivational goal of universalism in the form of tolerance for and appreciation of religion and other traditions (Buksinski 2003; Howard 2003). Moreover, ‘traditional’ may be associated with concern for other (community, societal welfare) and compatible with universalism values. In contrast, rejecting tradition in favor of modernizing may be associated with concern for self.

Blind patriotism

Positive correlations with conservation values because uncritical attachment to and identification with one’s country provide both a sense of certainty and of being part of something meaningful and lasting; negative correlations with universalism and openness to change values because blind patriotism is intolerant of out-groups and conflicts with free, individual self-expression.

Law and order

Positive correlations with conservation values because law and order protect against threatening, anxiety-arousing disruption of the social order; negative correlations with openness to change and universalism values because emphasizing law and order restricts individuals’ freedom to pursue unique or unusual and potentially disruptive interests, adventures and pleasures, and it discourages tolerance of different ways of living. Evidence that universalism values have a more conservative meaning in post-communist countries (Bardi and Schwartz 1996; Cieciuch and Schwartz 2012) suggests that law and order may not correlate negatively with universalism values in these countries.

Foreign military intervention

Positive correlations with conservation and power values because such military action protects against external sources of danger and change and does so through dominating power; negative correlations with self-transcendence values because they favor finding non-aggressive ways to handle problems and oppose actions that may harm others, and with self-direction because it emphasizes the importance of independence, hence of non-interference in the affairs of others. In the post-communist countries, however, we expect no associations of conservation values with support for intervening militarily in foreign countries. We reason that the relatively recent military intervention by the former Soviet Union in these countries will have undermined the usual link between these values and viewing military action as a source of protection.

Free enterprise

Positive correlations with self-enhancement values because economic individualism allows unfettered pursuit of own success and wealth; negative correlations with self-transcendence values because free enterprise allows exploitation of others and removes governmental regulation that can protect the weak. We also expect positive correlations of free enterprise with conservation values in the non-communist countries. There, conservative political rhetoric favors free enterprise and defines government involvement in business and public welfare as interference in the lives of citizens (e.g., Benoit and Laver 2006; Hughes 2008).

In contrast, we expect negative correlations with conservation values in post-communist countries, because those who value security and preserving the status quo are likely to be more disillusioned with the insecurity and constant change that growth of entrepreneurial capitalism has brought about (Poznanski 2001). A finding in a study by McFarland et al. (1992) supports this expectation. They found that authoritarianism predicted support for laissez-faire individualism (similar to our free enterprise) in an American sample but opposition to it in a Russian sample. As several studies have shown, authoritarianism is closely related to conservation values (e.g., Altemeyer 1998; Cohrs et al. 2005).

Equality

Positive correlations with self-transcendence values because equality expresses concern for others’ welfare; negative correlations with self-enhancement values because equality conflicts with enabling individuals to pursue their own interests even at the expense of others. In post-communist countries, we also expect a positive correlation of equality with conservation values. Under communist rule, providing economic and social security through equality served as a key justification for the regime. Those who cherish conservation values are more likely to accept prevailing regimes and their justification (Roccas et al. 2010). The rapid expansion of free enterprise and capitalism in the post-communist countries has reduced socio-economic equality (Mitra and Ruslan 2007). Therefore, those high in conservation values, who link equality more to communism, may evaluate the core political value of equality more positively than others do.

Civil liberties

Positive correlations with self-direction and self-transcendence values because favoring individuals’ freedom of thought and action requires high tolerance and low anxiety regarding all ideas and concern for others; negative correlations with power and conservation values because freedom for everyone to act and think as they deem appropriate risks unexpected threatening ideas and behavior that violate norms and traditions. We make no prediction for conservation values in post-communist countries. The welcome, sharp rise in the level of personal freedom in these countries is probably still too recent even for people who emphasize these values to disapprove of civil liberties (Rose 1997).

Accepting immigrants

Positive correlations with self-transcendence, self-direction, and stimulation values because accepting immigrants expresses concern for their welfare and may expose people to new and exciting ideas and behavior; negative correlations with conservation values because new immigrants may be perceived as dangerous to personal security and as challenging traditional ideas, norms, practices.Footnote 4

The correlations that we hypothesize between the basic personal values and core political values all reflect the circular motivational structure of compatible and conflicting basic values. Hence, confirming these hypotheses would support the claim that the coherent motivational structure that organizes basic values also organizes relations among core political values. If a set of core political values shares similar patterns of correlation with basic values, they should show substantial positive relations among themselves. Thus, the shared grounding of law and order, blind patriotism, and traditional morality in the three conservation values versus the three openness to change values and universalism (without universalism in the post-communist countries) should link them together. The hypothesized patterns of correlation also imply a negative link of these three core political values with accepting immigrants, which is grounded in the opposite set of basic values.

The hypothesized patterns of correlation further suggest that the opposition between universalism and power values, in particular, underlies and unites the core political values of equality and civil liberties and links them negatively with free enterprise. This implies that the primary motivational conflict that guides these political values is concern for others’ interests versus self-interest.

The positive grounding of the attitude toward foreign military intervention in conservation values gives rise to positive links with law and order, blind patriotism, and traditional morality that share this grounding and a negative link with accepting immigrants that is grounded negatively in conservation values. The grounding of foreign military intervention in power versus self-transcendence values should link it to free enterprise. We expect no positive correlations of foreign military intervention with the conservation values in the post-communist countries. Its links with law and order, blind patriotism, and traditional morality should therefore be somewhat different in those countries. Its relations with the other core political values should be largely determined by its grounding in power versus universalism.

Method

Samples and Procedures

We recruited adults who were eligible to vote in 15 countries: Australia, Brazil, Chile, Germany, Greece, Finland, Israel, Italy, Poland, Slovakia, Spain, Turkey, Ukraine, United Kingdom, and United States. Except in Australia, the United Kingdom, Germany, and Turkey, respondents were recruited personally by university students and completed a self-report questionnaire individually. Responses were in writing in 11 countries, online in Australia, Finland, and the United Kingdom, and by telephone interview in Germany. The Australian sample came from a database of community participants administered through a university. Convenience samples were obtained in all countries but Germany (representative national sample) and Turkey (representative sample of the Istanbul province). Following rigorous translation and back-translation of all instruments, we gathered data in the local language of each country. Table 2 describes the sample characteristics.

Measures

Basic Personal Values

The Portrait Values Questionnaire (PVQ: Schwartz 2003, 2006; Schwartz et al. 2001) measured basic values. The PVQ includes 40 short verbal portraits of different people matched to the respondents’ gender, each describing a person’s goals, aspirations, or wishes that point implicitly to the importance of a value. For example, “It is important to him to listen to people who are different from him. Even when he disagrees with them, he still wants to understand them” describes a person who endorses universalism values. Three to six items measure each value. For each portrait, respondents indicate how similar the person is to themselves on a scale ranging from “not like me at all”—1 to “very much like me”—6. Respondents’ own values are inferred from the implicit values of the people they describe as similar to themselves. Appendix A presents the instructions and one exemplary item per value.

Multimethod–multitrait analyses of the ten values measured with the PVQ and with the Schwartz Value Survey (Schwartz 1992) confirm the convergent and discriminant validity of the PVQ indexes (Schwartz 2006). The mean alpha reliability coefficients across the 15 countries in this study ranged from 0.57 (tradition) to 0.80 (achievement), with an overall mean of 0.69 (SD = 0.07). This is the typical range in many studies, reflecting the small number of items that measure each value and which are intended to cover the conceptual breadth of the value rather than a core idea (e.g., power includes both dominance and wealth). Schwartz (2006) reports test–retest correlations for these indexes ranging from 0.65 to 0.75 in several samples and summarizes substantial evidence for the predictive validity of the indexes across numerous studies.

Core Political Values

We adopted or modified items that Schwartz et al. (2010) used, many of which they took from Feldman (1988), McCann (1997), Jacoby (2006), Gunther and Kuan (2007), and Schatz et al. (1999), to measure the eight core political values. Our Israeli collaborator did not include accepting immigrants or military intervention. Immigration items have a different meaning in Israel than elsewhere, given an official policy and public discourse that encourages Jewish immigration from around the world. Moreover, the constant state of military threat in Israel and the frequent engagement in wars give a different meaning to the military intervention items. In order to prevent an acquiescence response bias, we formulated two or three positively worded and two negatively worded items for each core political value. Responses were: completely disagree—1, agree a little—2, agree somewhat—3, agree a great deal—4, completely agree—5.

To assess whether the items in the scale yielded distinct factors for each political value, we performed a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in each country, using maximum-likelihood estimation in the MPLUS program (Muthén and Muthén 1998). A model with oblique factors for each political value yielded an unsatisfactory fit in all countries. The poor fit was largely due to the use of reverse-worded items; many of the negatively worded items showed particularly problematic psychometric properties.Footnote 5 This problem is common with self-report scales that include reverse-worded items (e.g., Barnette 2000; Spector et al. 1997), especially in cross-cultural research (Wong et al. 2003).We tried adding different methods factors and correlated errors in the CFA models to deal with the presence of items worded in positive and negative directions. However, none of these models yielded an acceptable fit in any country. We therefore dropped all negatively worded items and ran a model with only the positively worded items.

Table 3 presents the fit indexes for the model with positively worded items. The RMSEA and SRMR indexes show an adequate fit in all countries. The CFI is acceptable in 11 countries but only >0.8 in Poland, Slovakia, Ukraine, and the United States. Given the adequate RMSEA and SRMR indexes in the latter countries, the loss of information if we dropped them, and the sensitivity of CFI to large numbers of variables,Footnote 6 we retained all of the countries in the study. Across countries, only 7 % of item loadings were <0.4 and 3 % were <0.3, with the latter not concentrated in any one country. Because dropping any of these items in a country would result in dropping the whole factor, we did not do so.Footnote 7 Appendix B lists the 18 items retained for use in this study and notes the core political value that each one measures.

Results

Associations Between Core Political Values and Basic Personal Values

Our general hypothesis proposed that the circular motivational structure that organizes basic personal values also organizes and gives coherence to core political values. The hypothesis for each political value specified one set of basic values expected to relate positively to the political value and another, motivationally opposed set, expected to relate negatively. We hypothesized that basic personal values relate to political values in the same way across the 15 countries in most instances, despite the different political contexts. We also specified likely variations due to the political history of post-communist countries that may have affected the meaning of some basic or core political values. Confirmation of the specific hypotheses (summarized in Table 1) would support the view that the motivational circle that organizes basic values also organizes relations among core political values.

Table 4 reports Pearson correlations between the core political and basic personal values across countries, weighting each sample equally. To correct for individual differences in scale use, we centered each person’s basic values on his or her own mean value rating (cf. Schwartz et al. 2001). We report correlations separately for the 12 non-communist (N = 5566–6692) and three post-communist countries (N = 1919). Given the large sample sizes, we set significance levels of 0.01 (post-communist) and 0.001 (non-communist). Table 4 also lists the proportion of countries with hypothesized correlations in the expected direction. For associations that were not hypothesized, it lists the proportion of countries with correlations in the same direction in parentheses.Footnote 8

All 55 hypothesized associations for the 12 non-communist countries were significant (p < 0.001, two-tailed). Of these associations, 50 were in the hypothesized direction in at least ten countries and 49 were r > /0.10/. Of the 25 associations that were not hypothesized, six were significant, in the same direction in at least ten countries, and correlated r > /0.10/.

For the three post-communist countries, 43 of the 44 hypothesized associationsFootnote 9 were significant (p < 0.01, two-tailed). Of these associations, 37 were in the hypothesized direction in all three post-communist countries and 36 correlated r > /0.10/ and were in the hypothesized direction in at least two countries. Seven of the 26 associations that we did not hypothesize were significant, in the same direction in at least two countries, and correlated r > /0.10/.

Of special interest are the cases with different hypotheses for the post-communist and the other countries. All but three of these hypotheses were confirmed. Universalism values correlated positively with traditional morality in the post-communist countries but negatively in the non-communist countries. Universalism values correlated negatively with law and order in the non-communist countries but were not correlated in the post-communist countries. The three conservation values correlated positively with military intervention in the post-communist countries but did not correlate in the non-communist countries. The three conservation values correlated negatively with free enterprise in the post-communist countries but positively in the non-communist countries. Finally, the three conservation values correlated positively with equality in the post-communist countries but, contrary to our expectation of no association, they correlated negatively with equality in the non-communist countries.

To provide a sense of the importance of basic values relative to other predictors, we compared the variance that they explained in each core political value with the variance explained by four socio-demographic variables: age, education, gender, and income. The second from last row of Table 4 gives the mean variance in each core political value that the ten basic values explained, calculated by averaging across regressions in each sample. The explained variance ranged from 17 % (military intervention) to 39 % (traditional morality) in the non-communist countries and from 6 % (free enterprise) to 30 % (traditional morality) in the post-communist countries. The last row gives the average variance explained by the socio-demographic variables alone. The last row, in parentheses, gives the incremental R 2 when adding the socio-demographic variables to the regressions after the basic values. Basic values accounted for substantially more variance than the socio-demographic variables did in every core political value. Once the basic values entered the regressions, the remaining direct effects of the background variables were quite weak.

The Shared Motivational Structure of Basic Personal Values and Core Political Values

We based all of the hypotheses on the compatibilities and conflicts among basic values expressed in the circular motivational continuum. Thus, the full set of correlation findings offers substantial support for the claim that the motivational structure that organizes basic values also organizes relations among core political values. To capture the comprehensive structure of relations among the core political and basic personal values, however, one must consider all of them together. We did this with multidimensional scaling analyses (MDS) that generated two-dimensional projections of the relations among the values of two types. If the basic and core political values share the same motivational structure, we expect the following: The ten basic values will be arrayed in the space in the order postulated by the basic values theory (Fig. 1), and the eight core political values will be arrayed in the same space in an order that reflects their hypothesized relations with the basic values.

As input to the MDS analyses, we generated matrixes of Pearson correlations among the ten basic personal values and the eight core political values. We generated one matrix for each country and pooled matrixes for the 12 non-communist and for three post-communist countries, weighting each country equally. The PROXSCAL program in SPSS 18.0 then performed ordinal MDS analyses on the matrixes, using Euclidean distances. We treated the projection for the 12 non-communist countries as the target for Procrustes rotations of each single country projection. This enabled us to assess the extent to which the associations in each country differ from those in the overall non-communist pattern and to identify specific deviations. For the post-communist countries, we examined whether the variations in associations that we hypothesized appeared in their two dimensional MDS projections.

Figure 2 presents the overall MDS projection for the 12 non-communist countries. Note first that the ten basic personal values retain their theorized motivational order going clockwise around the circle from self-direction to universalism. Inclusion of the core political values in the analysis did not change the motivational structure of basic personal values. This suggests that relations of core political values to one another and to basic personal values are compatible with the motivational structure that organizes basic values.

Multidimensional analysis of eight core political values and 10 basic personal values for 12 Non-communist Countries (Stress 1 = 0.062; Dispersion Accounted for = 0.996; Tucker’s Coefficient of Congruence 0.998). Note Basic Values, ACHIE achievement, HEDON hedonism, STIM stimulation, SDIR self-direction, UNIV universalism, BENE benevolence, TRAD tradition, CONF conformity, SECU security; Core Political Values: TradMor traditional morality, LwOrdr law & order, BlndPat blind patriotism, MltInt military intervention, FreEnt free enterprise, CvlLib civil liberties, AcptIm accepting immigrants, Equal equality

We then compared the separate, Procrustes rotated projection for each of the 12 countries with the overall projection. Tucker’s phi coefficient, which correlates the coordinates of the values in each country sample with the overall sample coordinates, measured similarity. A phi coefficient of 0.95 is commonly taken as indicating virtually complete identity (van de Vijver and Leung 1997). Table 5 shows that Tucker’s phi was at least 0.95 on both dimensions for all but the Turkish sample. Hence, we can take the overall projection as a good indicator of the findings in the various samples. Examination of the coordinates for Turkey revealed that the coordinates of accepting immigrants were the main source of deviation from the overall pattern.Footnote 10

We next consider what the locations in the overall MDS projection and the correlations tell us about the structure of the eight core political values. The locations of the political values in the space reveal their relations both to one another and to the basic values. Traditional morality, blind patriotism, and law and order cluster together at the bottom of Fig. 2. Much the same basic values predicted them all (Table 4). Their spatial location and their correlations with basic values suggest that the motivations underlying the three conservation values that predict these three core political values positively and the three openness to change values that predict them negatively structure these political values. Their shared negative association with universalism values also points to a common underlying motivation.

The locations of accepting immigration and civil liberties in Fig. 2 (top left) reveal that their motivational underpinnings oppose those of traditional morality, blind patriotism, and law and order. They correlate most negatively with the three conservation values and most positively with universalism, self-direction, and benevolence. Civil liberties expresses more of an openness motivation whereas accepting immigration expresses more concern for the welfare of others.

The locations of the core political values of equality (top left) and free enterprise (bottom right) in Fig. 2 indicate that concern for all others is the main motivational basis of the former and self-interest the main motivational basis of the latter. Individuals’ stands on these two core political values express the relative importance they ascribe to power versus universalism values. In addition, free enterprise expresses the motivational opposition between conservation and self-direction values.

Lastly, the location of foreign military intervention in Fig. 2 (bottom right) suggests that it is linked to free enterprise by their shared motivation to control and dominate versus to promote others’ welfare. This location reflects their positive correlations with power and negative correlations with universalism. Like law and order, blind patriotism, and traditional morality, foreign military intervention is grounded in the three self-protective, conservation values. Like them, and in contrast to accepting immigrants and civil liberties, it conflicts with universalism and self-direction values that foster tolerance for others who are different.

Figure 3 presents the overall MDS projection for the three post-communist countries. It includes the ten basic values and seven political values that were meaningful in all three countries (excluding accepting immigrants). Here too, the ten basic personal values retain their theorized motivational order going clockwise around the circle from self-direction to universalism.

Multidimensional analysis of seven core political values and 10 basic personal values for three post-communist countries (Stress 1 = 0.118; Dispersion Accounted for = 0.986; Tucker’s Coefficient of Congruence 0.993). Note Basic Values, ACHIE achievement, HEDON hedonism, STIM stimulation, SDIR self-direction, UNIV universalism, BENE benevolence, TRAD tradition, CONF conformity, SECU security; Core Political Values: TradMor traditional morality, LwOrdr law & order, BlndPat blind patriotism, MltInt military intervention, FreEnt free enterprise, CvlLib civil liberties, Equal equality

Comparing the array of values in Fig. 3 with Fig. 2, we see evidence for each of the hypothesized differences between post-communist and non-communist countries. The distances between the core political values and the basic values reflect the different relations. For every hypothesized difference, the political value is closer to the basic values in the set of countries for which the predicted association was more positive. Thus, free enterprise is substantially closer to the three conservation values in the non-communist countries (Fig. 2), where we predicted a positive association, than in the post-communist countries (Fig. 3), where we predicted a negative association. And traditional morality is closer to universalism in the post-communist countries (Fig. 3), where we predicted a positive association than in the non-communist countries (Fig. 2), where we predicted a negative association. For law and order, military intervention, equality, and civil liberties, the expected differences in distances are also present.

Comparing the Procrustes rotated projection for each post-communist country with the overall projection for the 12 non-communist countries identified the specific deviations in each country. Tucker’s phi coefficients less than 0.95 indicated the values whose locations deviated from the overall projection. All were values for which we had hypothesized differences. In Slovakia, there was substantial deviation for equality and lesser deviations for universalism, civil liberties, and traditional morality. In Ukraine, there were substantial deviations for traditional morality and civil liberties and lesser deviations for equality, universalism, and law and order. In Poland, there were substantial deviations for free enterprise, universalism, equality, and traditional morality.

Discussion

Associations Between Core Political Values and Basic Personal Values

Drawing on the assumption that political values express basic values in the political domain and on the meanings of each political and basic value, we proposed a set of associations between them. These associations also implied how the political values cluster together. We predicted somewhat different associations for non-communist and post-communist countries because of postulated differences between the meanings of some values in these political contexts. For the non-communist countries, all 55 hypothesized associations were significant. For the post-communist countries, 43 of the 44 hypothesized associations were significant and one was zero.

The MDS graphic projections of relations among basic values and core political values (Figs. 2, 3) and the pattern of correlations between them (Table 4) revealed their shared motivational structure. The findings suggest that the coherent structure of motivations that organizes basic values also structures core political values. The motivational opposition of conservation values to openness to change values underlies the political values of law and order, blind patriotism, and traditional morality, producing coherence among them. In the non-communist countries, an absence of motivation for universalism values also underlies these political values and leads to their mutually positive associations. Accepting immigrants expresses the opposite set of basic value priorities. It is grounded in motivations opposite to law and order, blind patriotism, and traditional morality and correlates strongly negatively with them.

The correlations of law and order, blind patriotism, and traditional morality with the conservation versus openness values imply that the motivations that underlie them are anxiety, fear of uncertainty, and change, protecting the self, and preventing loss (Schwartz 2006, 2010). The negative correlation of these political values with universalism values implies lack of concern for the welfare of those outside the ingroup. The contents of these political values express just such motivations. They refer to protecting oneself and one’s extended ingroup from disorder and danger due to crime, disruptive and unconventional minorities, and new life styles and beliefs, and to believing one’s country protects against threats and can do no wrong.

The motivational underpinnings of accepting immigrants are the reverse of the three political values with which it correlates negatively. Accepting immigrants expresses low fear of uncertainty and a view of change and diversity as potential sources of gain, growth, and self-expansion. It is also grounded in concern for the welfare of all others. The items that measure accepting immigrants clearly express its value-based motivations. They assert that immigrants (implicitly, people whose different life styles and unpredictable behavior may introduce change) are a source of benefit rather than threat to society.

The findings suggest that the political values of equality, civil liberties and—in reverse direction—free enterprise express the motivational opposition of self-transcendence versus self-enhancement values. The main motivational focus of these political values is concern for others’ versus own interests. The notably stronger associations with universalism than with benevolence signify concern for others outside one’s ingroup. The associations with power indicate that these political values contrast readiness to exploit others for one’s own benefit with sacrifice of own interests to benefit others. Expressing their underlying motivations, the equality items refer to giving benefits to ‘everyone’, ‘rich and poor’, and ‘all citizens’, although this may reduce own benefits. The free enterprise items express an opposing goal: reducing restraints on individuals’ pursuit of self-interest even if some suffer. The civil liberties items express not only concern for others but the opposition between self-direction and tradition values. They emphasize respecting and protecting the uniqueness of people, implicitly including those whose beliefs and life-styles violate norms or traditions.

The analyses indicate that foreign military intervention expresses a combination of the motivations of conservation and power values versus universalism values. This suggests that support for foreign military intervention is anxiety-based and focused on self-protection and prevention of loss. It further suggests that the pursuit of self-interest serves to justify undertaking military action even if it may disregard or harm others’ well-being.

Differences Between Non-Communist and Post-Communist Countries

In generating the hypotheses, we identified aspects of the political context in the post-communist countries that suggest variations in the meaning of some basic or political values that may thereby affect associations between them. A boomerang against communist regimes’ attempts to substitute communism as the basis for morality, instead of religion or ethnic traditions, may explain why universalism values correlated positively with traditional morality only in the post-communist countries. After the communist regimes fell, endorsing traditional morality may have been a way to affirm appreciation of and tolerance for religion and ethnicity, thereby expressing the motivation of universalism (Buksinski 2003; Howard 2003). That universalism values did not correlate negatively with law and order values in the post-communist countries supports the assumption that universalism values have a more conservative meaning in those countries (Bardi and Schwartz 1996; Cieciuch and Schwartz 2012).

In the non-communist countries, military intervention correlated positively with conservation values, presumably because people believe it provides security. We reasoned that the relatively recent military intervention by the former Soviet Union in the post-communist countries attenuated this belief. Correlations near zero in the post-communist countries support this idea. In the non-communist countries, free enterprise correlated positively with conservation values, presumably reflecting the conservative rhetoric about limiting government. However, we predicted and found a negative correlation in the post-communist countries. This supports the reasoning that those who cherish conservation values experience the insecurity caused by the rampant free enterprise in those countries as especially threatening and upsetting. It also partly replicates the McFarland et al. (1992) finding in the Soviet Union that authoritarianism, which is closely related to conservation values, predicted rejection of laissez-faire individualism (similar to free enterprise here).

W expected and found that, only in the post-communist countries, did conservation correlate positively with equality. We suggested that, especially among those who cherish conservation values and identify more with prevailing regimes, equality had become linked to security because communist regimes justified themselves as providing economic and social security through equality. Faced with increased insecurity and socio-economic inequality, following the fall of communism, those high in conservation values endorsed equality more as a way to restore security. Conservation and civil liberties values were not correlated in the post-communist, in contrast to the non-communist, countries. This may reflect an interesting trade-off. Those who cherish conservation values may have felt threatened by the counter-normative, novel ideas and behavior that accompanied the increase in civil liberties, but even they may have welcomed the sharp initial increase in personal freedoms (Rose 1997).

Unexpected Findings

There were 11 significant non-predicted correlations />0.10/. However, none contradicted the hypotheses because they were similar to the correlations predicted for values adjacent in the motivational circle. For example, the three non-predicted correlations for benevolence values corresponded to the predicted correlations for universalism and the three for hedonism corresponded to those predicted for achievement. All non-predicted correlations were compatible with the reasoning underlying the hypotheses because adjacent values share motivational orientations.

The patterns of correlation were almost identical among all the non-communist countries except Turkey, according to the phi coefficients. Close examination revealed that the main source of deviation was the correlations between accepting immigrants and basic values. This may reflect the distinctive situation of immigration in Turkey in recent decades compared with the other non-communist countries. Once a country of emigration, Turkey has become a magnet for illegal immigrants, asylum seekers, irregular migrants from former Soviet Bloc countries, and a transit country to the European Union for irregular migrants from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Iraq, Iran, Pakistan, and Syria (Kirisci 2003). A shifting government immigration policy combined with the complexities of diverse, illegal, and irregular immigration may make it difficult for Turks to form consistent, value-based attitudes toward immigration.

Limitations and Future Directions

The scales that initially operationalized the political values in this study-included reverse scored items. It was necessary to drop all of these items in order to attain acceptable indexes, leaving only two or three items per political value. Although the RMSEA and SRMR indexes were adequate, the CFI was problematic in three countries. Future research should include a larger number of items to measure each core political value, probably with no reverse items.

Ideally, one would address the issues of this study with representative national samples. In all countries but Germany, however, our samples were more educated and urban than the general population. To obtain a sense of how much this may have affected the patterns of association we found, we provide more detail on the findings in Germany, the one representative national sample. In Germany, 49 hypotheses were tested because, as noted (footnote 7), civil liberties was not included. Correlations were in the hypothesized direction for 46 of these and significant for 41. For the remaining three hypotheses, correlations were zero. Four of the non-significant correlations related to military intervention, still a complex issue in Germany after WW II (No shooting please 2012). The German findings suggest that the patterns we observed were not due to the special characteristics of the other samples.

Studying possible moderators of the relations between basic personal values and core political values is worthwhile, though beyond the scope of the current article. There is initial evidence that education enhances these associations (Schwartz et al. 2010) and that political expertise promotes reliance on core values and beliefs to derive issue preferences, at least under some conditions (Goren 2000). Extending this study to countries with different political systems (e.g., Singapore, China, and Morocco) is another future direction. The meaning of some core political values may vary in ways that suggest different hypothesized relations with basic values.

The political values we studied were among the most prominent core values in the political science literature. Future research should study how the motivational structure of basic personal values underlies and gives coherence to other political values such as positions on the environment, welfare, and defense. Available studies have shown that basic personal values underlie such politically relevant personality constructs as right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation (Altemeyer 1998; Cohrs et al. 2005). Research should also study political attitudes uniquely relevant to the discourse in different countries. Linking such attitudes to basic personal values will help to clarify their motivational significance and their relations to core political values.

Conclusion

The current study demonstrated that theoretically grounded associations among basic personal values and core political values generalized across 12 non-communist countries. It also revealed that many of these associations held in three post-communist countries but that some did not. The variations in the post-communist countries were largely predicted based on the specific meanings that life under communist regimes may have given to universalism, free enterprise, civil liberties, and equality values.

The current study helps to clarify the nature of political choice. Core political values are expressions of basic personal values. Moreover, an Italian study showed that political values mediated relations between basic values and subsequent voting behavior (Schwartz et al. 2010). Here, basic values predicted political values over and above the effects of four socio-demographic variables that reflect people’s social locations. This strengthens the assumption that individual differences in values play a critical role in political choice. Investigating basic personal values can provide another benefit to students of politics. Individuals’ basic value priorities exhibit greater stability than their political attitudes, values, and opinions, and they are less sensitive to ongoing social, political, and economic developments. As a result, by assessing changes in basic values, one can better determine which changes in the political atmosphere are fundamental and longer-term.

An important contribution of this research is the insight it provides into the organization of political thought. A coherent, overarching structure of conflicting and compatible motivations apparently organizes diverse political values. The circular motivational continuum that organizes relations among basic personal values also structures relations among core political values. The motivational underpinnings of core political values explain how they are interrelated.

The current findings might give politicians hints about how to frame political issues to shape public opinion on political issues. Politicians might communicate more effectively with the public and with their own constituents by grounding their messages about specific core political values in the motivational bases we identified as supporting or conflicting with them. Although people rarely recognize how their basic personal values affect their political views, our findings reinforce the claim that individuals’ political ideologies are firmly rooted in their basic values (Feldman 2003; Schwartz 1994).

Notes

We refer to ‘political values’ because that term is common in the political science literature. They might also be called ‘political attitudes’ because they are generally conceptualized and measured as evaluations of politically relevant objects.

We provide relatively brief rationales for each hypothesis. By considering the congruence of the core political values with the definitions of the basic personal values and with their dynamic underpinnings described above, one can elaborate these rationales more fully.

Hypotheses that differ for the post-communist countries appear in parentheses.

We excluded the three countries that had negative net migration during the years preceding the study (Brazil, Poland, and Ukraine) from consideration because the questions about accepting immigrants may not have been meaningful there. We also excluded Israel, for reasons noted below.

Across countries, the majority of high modification indexes referred to cross-loadings of negatively worded items or to correlated uniqueness among items worded in the same direction. Numerous negatively worded items had standardized loadings <0.3 on their presumed factor and/or reduced the internal reliability of the summed scale of their political value.

Kenny and McCoach (2003) note that even in correctly specified models CFI tends to worsen as the number of variables in a model grows large.

One of the two positively worded civil liberties items was inadvertently left out in the German study. Hence, we could not include civil liberties in the German analyses.

The correlations for each country are available from the first author.

We do not include hypotheses for accepting immigrants in this count because we did not test them in Poland and Ukraine (see footnote 3). In Slovakia, all seven hypotheses for accepting immigrants were supported.

The coordinates for the overall MDS and for each country are available from the first author.

References

Altemeyer, B. (1998). The other “authoritarian personality”. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 30, pp. 47–92). San Diego: Academic Press.

Ashton, M. C., Danso, H. A., Maio, G. R., Esses, V. M., Bond, M. H., & Keung, D. K. Y. (2005). Two dimensions of political attitudes and their individual difference correlates: A cross-cultural perspective. In R. M. Sorrentino, D. Cohen, J. M. Olson, & M. Zanna (Eds.), Culture social behavior: The Ontario symposium (Vol. 10, pp. 1–29). London: Erlbaum.

Bardi, A., & Schwartz, S. H. (1996). Relations among socio-political values in Eastern Europe: Effects of the communist experience? Political Psychology, 17, 525–549.

Barnette, J. J. (2000). Effects of stem and Likert response option reversals on survey internal consistency: If you feel the need, there is a better alternative to using those negatively worded stems. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 60, 361–370.

Benoit, K., & Laver, M. (2006). Party policy in modern democracies. New York: Routledge.

Bilsky, W., Janik, M., & Schwartz, S. H. (2011). The structural organization of human values—Evidence from three rounds of the European Social Survey (ESS). Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 42, 759–776.

Braithwaite, V. (1997). Harmony and security value orientations in political evaluation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 401–414.

Buksinski, T. (2003). Liberalisation and transformation of morality in post-Communist countries: Polish philosophical studies, IV. Washington: The Council for Research in Values & Philosophy.

Cieciuch, J., & Schwartz, S. H. (2012). The number of distinct basic values and their structure assessed by PVQ-40. Journal of Personality Assessment, 94, 321–328.

Cohrs, J. C., Moschner, B., Maes, J., & Kielmann, S. (2005). The motivational bases of right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation: Relations to values and attitudes in the aftermath of September 11, 2001. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 1–10.

Conover, P. J., & Feldman, S. (1981). Origins and meaning of liberal/conservative self-identifications. American Journal of Political Science, 25, 617–645.

Converse, P. E. (1964). The nature of belief systems in mass publics. In D. E. Apter (Ed.), Ideology and discontent (pp. 206–261). New York: Free Press.

Daigle, J., Hrubes, D., & Ajzen, I. (2002). A comparative study of beliefs, attitudes, and values among hunters, wildlife viewers, and other outdoor recreationists. Human Dimensions of Wildlife: An International Journal, 7, 1–19.

Dollinger, S. J., Burke, P., & Gump, N. W. (2007). Creativity and values. Creativity Research Journal, 19, 91–103.

Evans, G., Heath, A., & Lalljee, M. (1996). Measuring left-right and libertarian-authoritarian values in the British electorate. The British Journal of Sociology, 47, 93–112.

Feldman, S. (1988). Structure and consistency in public opinion: The role of core beliefs and values. American Journal of Political Science, 32, 416–440.

Feldman, S. (2003). Values, ideology, and structure of political attitudes. In D. O. Sears, L. Huddy, & R. Jervis (Eds.), Oxford handbook of political psychology (pp. 477–508). New York: Oxford University Press.

Fontaine, J. R., Poortinga, Y. H., Delbeke, L., & Schwartz, S. H. (2008). Structural equivalence of the values domain across cultures: Distinguishing sampling fluctuations from meaningful variation. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 39, 345–365.

Gardikiotis, A., & Baltzis, A. (2012). ‘Rock music for myself and justice to the world!’: Musical identity, values, and music preferences. Psychology of Music, 40, 143–163.

Goodwin, R., & Tinker, M. (2002). Value priorities and preferences for a relationship partner. Personality and Individual Differences, 32, 1339–1349.

Goren, P. (2000). Political expertise and principled political thought. Political Research Quarterly, 53, 117–136.

Goren, P. (2005). Party identification and core political values. American Journal of Political Science, 49, 881–896.

Gunther, R., & Kuan, H. C. (2007). Value cleavages and partisan conflict. In R. Gunther, J. R. Montero, & H. J. Puhle (Eds.), Electoral intermediation, values, and political support in old and new democracies: Europe, East Asia, and the Americas in comparative perspective (pp. 255–320). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gunther, R., Montero, J. R., & Puhle, H. J. (2007). Op. cit.

Heath, A., Jowell, R., & Curtice, J. (1985). How Britain votes. Oxford: Pergamum.

Hitlin, S., & Piliavin, J. A. (2004). Values: Reviving a dormant concept. Annual Review of Sociology, 30, 359–393.

Howard, M. M. (2003). The weakness of civil society in post-communist Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hughes, C. (2008). Civil liberties in Australia: A review article. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 27, 72–76.

Hurwitz, J., & Peffley, M. (1987). How are foreign policy attitudes structured? A hierarchal model. American Political Science Review, 81, 1099–1120.

Inglehart, R. (1997). Modernization and postmodernization. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Jacoby, W. G. (1995). The structure of ideological thinking in the American public. American Journal of Political Science, 39, 314–335.

Jacoby, W. G. (2006). Value choices and American public opinion. American Journal of Political Science, 50, 706–723.

Kenny, D. A., & McCoach, D. B. (2003). Effect of the number of variables on measures of fit in structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 10, 333–351.

Kerlinger, F. N. (1984). Liberalism and conservatism: The nature and structure of social attitudes. Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Kinder, D. R. (1998). Opinion and action in the realm of politics. In D. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (pp. 778–867). New York: Oxford University Press.

Kinder, D. R., & Sears, D. O. (1985). Public opinion and political action. In G. Lindzey & E. Aronson (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology, Vol. II (3rd ed., pp. 659–741). NY: Random House.

Kirisci, K. (2003). Turkey: A transformation from emigration to immigration. Washington: Migration Policy Institute.

Knafo, A., Daniel, E., & Khoury-Kassabri, M. (2008). Values as protective factors against violent behavior in Jewish and Arab high schools in Israel. Child Development, 79, 652–667.

Lee, M., Whitehead, J., Ntoumanis, N., & Hatzigeorgiadis, A. (2008). Relationships among values, achievement orientations and attitudes in youth sport. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 30, 588–610.

McCann, J. A. (1997). Electoral choices and core value change: The 1992 presidential campaign. American Journal of Political Science, 41, 564–583.

McFarland, S. G., Ageyev, V. S., & Abalakina-Paap, M. A. (1992). Authoritarianism in the former Soviet Union. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 1004–1010.

Mitra, P., & Ruslan, Y. (2007). Increasing inequality in transition economies: Is there more to come? In F. Bourguignon & B. Pleskovic (Eds.), Annual world bank conference on development economics, regional: beyond transition (pp. 59–102). Washington: The International bank for reconstruction and development/the world bank.

Muthén, L., & Muthén, B. (1998). Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

No shooting please, we’re German. (2012). The Economist. Retrieved July, 27, 2013 from http://www.economist.com/node/21564617.

Peffley, M. A., & Hurwitz, J. (1985). A hierarchical model of attitude constraint. American Journal of Political Science, 29, 871–890.

Pepper, M., Jackson, T., & Uzzell, D. (2009). An examination of the values that motivate socially conscious and frugal consumer behaviors. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 33, 126–136.

Poznanski, K. Z. (2001). Building capitalism with communist tools: Eastern Europe’s defective transition. East European Politics and Societies, 15, 320.

Roccas, S., Schwartz, S. H., & Amit, A. (2010). Personal value priorities and national identification. Political Psychology, 31, 393–419.

Rohan, M. J. (2000). A rose by any name? The values construct. Personality & Social Psychology Review, 4, 255–277.

Rokeach, M. (1973). The nature of human values. New York: Free Press.

Rose, R. (1997). How patient are people in post-communist societies? World Affairs, 159, 130–144.

Sagiv, L. (2002). Vocational interests and basic values. Journal of Career Assessment, 10, 233–257.

Saroglou, V., Delpierre, V., & Dernelle, D. (2004). Values and religiosity: a meta-analysis of studies using Schwartz’s model. Personality and Individual Differences, 37, 721–734.

Schatz, R. T., Staub, E., & Lavine, H. (1999). On the varieties of national attachment: Blind versus constructive patriotism. Political Psychology, 20, 151–174.

Schubot, D. B., Eliason, B. C., & Cayley, W, Jr. (1995). Personal values and primary care specialty aspirations. Academic Medicine, 70, 952–953.

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 25, pp. 1–65). New York: Academic Press.

Schwartz, S. H. (1994). Are there universal aspects in the content and structure of values? Journal of Social Issues, 50, 19–45.

Schwartz, S. H. (2003). Value orientations. European Social Survey Core Questionnaire Development, Chapter 07. Retrieved from http://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/index.php?option=com_docman&task=cat_view&gid=83&Itemid=80..

Schwartz, S. H. (2006). Les valeurs de base de la personne: Théorie, mesures et applications [Basic human values: Theory, measurement, and applications]. Revue Française de Sociologie, 47, 249–288.

Schwartz, S. H. (2010). Basic values: How they motivate and inhibit prosocial behavior. In M. Mikulincer & P. Shaver (Eds.), Prosocial motives, emotions, and behavior: The better angels of our nature (pp. 221–241). Washington: American Psychological Association Press.

Schwartz, S. H., Caprara, G. V., & Vecchione, M. (2010). Basic personal values, core political values, and voting: A longitudinal study. Political Psychology, 31, 421–452.

Schwartz, S. H., Melech, G., Lehmann, A., Burgess, S. A. M., & Harris, M. (2001). Extending the cross-cultural validity of the theory of basic human values with a different method of measurement. Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology, 32, 519–542.

Spector, P. E., Van Katwyk, P. T., Brannick, M. T., & Chen, P. Y. (1997). When two factors don’t reflect two constructs: How item characteristics can produce artifactual factors. Journal of Management, 23, 659–677.

van de Vijver, F. J. R., & Leung, K. (1997). Methods and data analysis for cross-cultural research. Newbury Park: Sage.

Wong, N., Rindfleisch, A., & Borroughs, J. E. (2003). Do reverse-worded items confound measures in cross-cultural consumer research? The case of the material values scale. Journal of Consumer Research, 30, 72–91.

Zaller, J. R. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Acknowledgments

This paper was partly supported by the HSE Basic Research Program (International Laboratory of Socio-cultural Research).

Ethics

This research complies with the laws of the countries in which it was conducted.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A: Exemplary PVQ Items, Organized by Higher Order Values, Male & Female Examples

Here we briefly describe some people. Please read each description and think about how much each person is or is not like you. Put an X in the box to the right that shows how much the person in the description is like you.

Self Enhancement

-

[Power] It is important to him to be in charge and tell others what to do. He wants people to do what he says.

-

[Achievement] Being very successful is important to her. She likes to impress other people.

Openness to Change

-

[Hedonism] Enjoying life’s pleasures is important to him. He likes to ‘spoil’ himself.

-

[Stimulation] She likes surprises. It is important to her to have an exciting life.

-

[Self-Direction] It is important to him to be independent. He likes to rely on himself.

Self-Transcendence

-

[Universalism] She wants everyone to be treated justly, even people she doesn’t know. It is important to her to protect the weak in society.

-

[Benevolence] It’s very important to him to help the people around him. He wants to care for their well-being.

Conservation

-

[Tradition] She thinks it is best to do things in traditional ways. It is important to her to keep up the customs she has learned.

-

[Conformity] It is important to him always to behave properly. He wants to avoid doing anything people would say is wrong.

-

[Security] It is important to her to live in secure surroundings. She avoids anything that might endanger her safety.

Appendix B: Items used to measure seven core political values used in the study

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schwartz, S.H., Caprara, G.V., Vecchione, M. et al. Basic Personal Values Underlie and Give Coherence to Political Values: A Cross National Study in 15 Countries. Polit Behav 36, 899–930 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-013-9255-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-013-9255-z