Abstract

Descriptions of Gettier cases can be interpreted in ways that are incompatible with the standard judgment that they are cases of justified true belief without knowledge. Timothy Williamson claims that this problem cannot be avoided by adding further stipulations to the case descriptions. To the contrary, we argue that there is a fairly simple way to amend the Ford case, a standard description of a Gettier case, in such a manner that all deviant interpretations are ruled out. This removes one major objection to interpreting our judgments about Gettier cases as strict conditionals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 The problem of deviant realizations

Consider the following standard description of a Gettier case:

- (ford):

Smith believes that Jones owns a Ford, on the basis of seeing Jones drive a Ford to work and remembering that Jones always drove a Ford in the past. From this, Smith infers that someone in his office owns a Ford. In fact, someone in Smith’s office does own a Ford—but it is not Jones, it is Brown. (Jones sold his car and now drives a rented Ford.)Footnote 1

When one is given this description and intuitively judges ‘Smith justifiedly and truly believes but does not know that someone in his office owns a Ford’, what is the precise content of the intuitive judgment? This is a key problem in the metaphilosophical debate about the logic and structure of thought experiments (cf. Williamson 2007, Chap. 6; Ichikawa and Jarvis 2009; Malmgren 2011). Following Malmgren (2011), we may call this the ‘content problem’ and our judgment the ‘Gettier judgment’.

At first glance, the content problem may appear to be rather trivial, for isn’t the content of the Gettier judgment simply that Smith justifiedly and truly believes but does not know that someone in his office owns a Ford? Taken at face value, this would be a claim about an actual person, Smith, and what he believes about his colleagues.Footnote 2 But when we perform a Gettier thought experiment we typically neither make, nor intend to make, a judgment about an actual situation. This suggests that the Gettier judgment must have some kind of modal content as well (but see Horvath forthcoming).

Gettier’s own intention was to refute the standard analysis of knowledge as justified true belief by showing that justified true belief (JTB for short) is not sufficient for knowledge (cf. Gettier 1963). It seems natural to understand the JTB-analysis as an account of the nature of knowledge (K for short) and thus to express it with the following metaphysically necessary biconditional (cf. Williamson 2007; Malmgren 2011):

- (JTBA):

□ (Something is K if and only if it is JTB)

Gettier’s thought experiment is widely regarded as successfully establishing that the right-to-left direction of the (JTBA) biconditional fails, i.e., that it is metaphysically possible to have JTB without K:

- (GC):

◊ (Something is JTB but not K)

But (GC) cannot simply be identical with the Gettier judgment, for the latter is much more specific than that (cf. Malmgren 2011, pp. 283–284). Consider an informal expression of the Gettier judgment, such as ‘Smith justifiedly and truly believes but does not know that someone in his office owns a Ford’. This judgment mentions a person, an office, and a car of a certain brand, none of which play any role in (GC). For this reason, we should rather think of the Gettier judgment as one of the premises in our reasoning towards the intended conclusion (GC) of the thought experiment.

In addition, the following premise also seems required, given that the described case should itself be metaphysically possible:

- (PG):

◊ ford

This allows for a more succinct formulation of the content problem: What content must the Gettier judgment (GJ) have in order to make the inference from (PG) to (GC) valid?

- (PG):

◊ ford

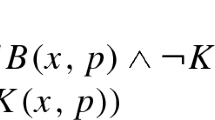

- (GJ):

?

- (GC):

◊ (Something is JTB but not K)

A natural proposal is to interpret (GJ) as a strict conditional that would facilitate the inference from (PG) to (GC) as followsFootnote 3:

- (PG):

◊ ford

- (NGJ):

□ (ford → (Something is JTB but not K))

- (GC):

◊ (Something is JTB but not K)

However, there is a broad consensus that interpreting (GJ) as (NGJ) has a fatal problem that makes this interpretation untenable (cf. Williamson 2007; Malmgren 2011). The problem is that the description (ford) is compatible with countless different ways of “filling out” the case in order to turn it into a complete scenario or possible world,Footnote 4 and while many of these completed scenarios will not make a difference to the truth of (NGJ), some do.

The description does not rule out, for example, Smith’s possession of additional evidence that would defeat his justification for the belief that someone in his office owns a Ford (cf. Williamson 2007, p. 185). Smith’s belief may also lack justification for a host of other reasons, depending on what specific conception of justification one has in mind. For example, Smith’s faculty of vision, memory, or logical reasoning may be unreliable, or Smith’s belief may not be coherently embedded in his overall belief system. Moreover, the description does not exclude the possibility that Smith has independent justification for his belief that is sufficiently strong for knowledge (cf. Malmgren 2011, p. 275).

As a consequence, the Gettier judgment is simply false when it is interpreted as (NGJ), because ‘deviant realizations’Footnote 5 of this kind are straightforward counterexamples to the claim that there is justified true belief without knowledge in every possible scenario in which (ford) is true.

Here is Williamson’s characteristically forceful presentation of the problem of deviant realizationsFootnote 6:

That (3) [i.e., Williamson’s version of (NGJ)] is the best representation of the verdict on the Gettier case is doubtful. In philosophy, examples can almost never be described in complete detail. An extensive background must be taken for granted; it cannot all be explicitly stipulated. Although many of the missing details are irrelevant to whatever philosophical issues are in play, not all of them are. … Any humanly compiled list of such interfering factors is likely to be incomplete. (Williamson 2007, p. 185; our emphasis)

In the next section, we will challenge Williamson’s claim that the relevant details cannot all be explicitly stipulated. To the contrary, there is a fairly simple way to amend the description (ford) such that all deviant realizations are ruled out. This result opens up a number of ways to resist Williamson’s objection against interpreting (GJ) as (NGJ). In the final section, we will explore some of the implications of our argument.

2 Amending the case description

The key to amending the case description (ford) in such a way that all deviant realizations are ruled out is the recognition that there are only two general kinds of deviant instances of (ford). That there are two kinds of deviance is a consequence of the philosophical purpose of Gettier thought experiments, which is to show that justified true belief is not sufficient for knowledge, so that an instance of (ford) can be deviant either by not being a case of JTB, after all, or by being a case of K.

This enables a systematic strategy for producing a non-deviant version of (ford): first, make sure that Smith really has the relevant justified true belief, and second, make sure that Smith does not know the relevant proposition in some other way. If we carefully carry out these two steps and cannot come up with any further deviant realizations, we will have good reason to believe that we have indeed produced a non-deviant case description.Footnote 7

We first ask: are there possible instances of (Ford) that fail to be cases of JTB? On a natural reading, (ford) already entails the relevant facts about B, i.e., that Smith believes that someone in his office owns a Ford, and T, i.e., that Smith’s belief is true. Nevertheless, we will amend the description by explicitly stipulating all the facts about B and T in order to rule out any potential deviant instances with respect to B and T:

- (ford-i):

Smith believes that Jones owns a Ford, on the basis of seeing Jones drive a Ford to work and remembering that Jones always drove a Ford in the past. From this, Smith infers to the belief that someone in his office owns a Ford. In fact, someone in Smith’s office does own a Ford, so that Smith’s latter belief is true—but it is not Jones, it is Brown, and so Smith’s initial belief was false. (Jones sold his car and now drives a rented Ford.)

With respect to justification, there are several ways in which an instance of (ford) can fail to be a case of (all-things-considered) doxastic justification. Some of these ways are widely acknowledged in epistemology, such as instances of (ford) where Smith possesses a defeater for his belief that someone in his office owns a Ford, e.g., by receiving the credible testimony that Jones sold his Ford. Other ways are more contentious, for example, instances involving the unreliability of some of Smith’s sources of justification, such as his memories of other people. As another example, it will also matter on certain views about epistemic justification whether Smith is in the relevant seeming states (cf. Huemer 2007; Tucker 2010).

One could try to explicitly stipulate all the properties that Smith’s belief would need in order to be justified according to all the standard theories of justification. Since all these properties—e.g., reliability, coherence, or the presence of seemings—seem compossible, this might actually be a feasible strategy. But this would not be the “fairly simple” amendment that we promised above, and moreover, it might be hard to come up with a complete list of every potentially justification-making property.

Fortunately, there is a much simpler way to rule out all deviant instances of (ford) that stem from a lack of justification: we can simply stipulate all the relevant facts about justification directly.Footnote 8 By stipulating that Smith’s relevant beliefs are justified we ensure that these beliefs have all the properties that are necessary for justification, whatever those properties may be.Footnote 9 Hence we arrive at:

- (ford-ii):

Smith justifiedly believes that Jones owns a Ford, on the basis of seeing Jones drive a Ford to work and remembering that Jones always drove a Ford in the past. From this, Smith infers to the justified belief that someone in his office owns a Ford. In fact, someone in Smith’s office does own a Ford, so that Smith’s latter belief is true—but it is not Jones, it is Brown, and so Smith’s initial belief was false. (Jones sold his car and now drives a rented Ford.)

Second, we ask: how can we rule out deviant instances of (ford) that are instances of knowledge? Doing so requires two sub-steps. First, we must rule out the possibility of there being unmentioned but epistemically relevant aspects of the way Smith acquired the belief that someone in his office owns a Ford that might make his belief count as knowledge. Here we explicitly state that Smith’s inference is based only on his belief that Jones owns a Ford, and that this logical inference provides Smith’s only justification for believing that someone in his office owns a Ford (to make things fully precise, we also add a time index). Second, we must also rule out the possibility that Smith knows in some other way than the one described that someone in his office owns a Ford. The best way to do this is by adding the conditional requirement that if Smith knows that someone in his office owns a Ford, then he knows this only in virtue of the facts that are explicitly mentioned in the case description. Putting the two sub-steps together produces the final “deviance-proof” description:

- (ford-iii):

Smith justifiedly believes that Jones owns a Ford, on the basis of seeing Jones drive a Ford to work and remembering that Jones always drove a Ford in the past. From this belief alone, Smith logically infers, at time t, to the justified belief that someone in his office owns a Ford, which provides his only justification for that belief at t. In fact, someone in Smith’s office does own a Ford, so that Smith’s latter belief is true—but it is not Jones, it is Brown, and so Smith’s initial belief was false. (Jones sold his car and now drives a rented Ford.) Also, if Smith knows at t that someone in his office owns a Ford, then he knows this at t only in virtue of the facts described. Footnote 10

That’s all, and it’s still fairly simple. The resulting description (ford-iii) excludes all “interfering factors” that might make it the case that Smith fails to have the relevant justified true belief, or that his belief is in fact knowledge, or both (if possible).

One might object that it is illegitimate to just go about stipulating all the facts about JTB in the case description, for what is at stake in a Gettier thought experiment is precisely how JTB and K are modally related (cf. Malmgren 2011, pp. 274–275). However, even though this objection has some initial plausibility, it is nevertheless misguided. What is at issue in the thought experiment is whether JTB is sufficient for knowledge. So the only thing that one definitely should not stipulate is whether Smith knows that someone in his office owns a Ford, for this would make the thought experiment useless as a test case for the JTB-account of knowledge. But as long as the resulting description does not explicitly state, or logically entail, whether Smith has knowledge—which (ford-iii) clearly does not do—there is no good reason not to stipulate that Smith’s belief that someone in his office owns a Ford is justified and true. Therefore, unless the resulting case description begs the question against the JTB-account of knowledge, it is legitimate to stipulate all the facts about J, T, and B.

But what about the final conditional clause, ‘if Smith knows at t that someone in his office owns a Ford, then he knows this at t only in virtue of the facts described’? Is it illegitimate to stipulate facts about knowledge in this way, since (NGJ) might then become trivially true?Footnote 11 No, it is not. First, the conditional in question neither states nor logically entails the only fact about knowledge that ultimately matters for the thought experiment, namely, whether Smith knows that someone in his office owns a Ford; the conditional only says that if Smith has that knowledge, then he has it only in virtue of the facts described. Second, it cannot be illegitimate to use the word ‘knows’ (or close cognates) in the case description, for the Gettier thought experiment presupposes competence with that word anyway.

Finally, one might also worry whether our basic idea, that there is a fairly simple way to amend (ford) in a manner that rules out all deviant interpretations, generalizes to other philosophical thought experiments. This is indeed a legitimate concern, for it cannot be assumed that all philosophical thought experiments are equal. Still, it seems very likely that many other philosophical thought experiments, e.g., trolley cases in ethics (cf. Thomson 1976), Nozick’s experience machine (cf. Nozick 1974), or fake barn cases (cf. Goldman 1976), are equally susceptible to deviant instances. We have not explored this issue here, nor whether there is a fairly simple way to make these other thought experiments “deviance-proof” as well. We therefore do not want to commit ourselves to any particular claim about how widely applicable our strategy is. However, the major philosophical importance of Gettier cases suffices to make our strategy philosophically significant, even if it only works for them.

3 Some implications

We have argued that there is a fairly simple way to amend (ford), a standard description of a Gettier case, in such a manner that all deviant interpretations are ruled out. Thus, Williamson is clearly wrong when he claims that “it cannot all be explicitly stipulated” (see quote above). What are the philosophical implications of this result?

First, when one actually uses an improved case description like (ford-iii), the problem of deviant realizations simply cannot arise, and so there is no decisive objection to interpreting the corresponding Gettier judgment in terms of (NGJ).

Second, improved case descriptions turn out to be not only possible but also relatively simple. For this reason, something along the lines of (ford-iii) seems like a good reconstruction of how the relevant experts implicitly interpret the original case description (ford) when they perform the thought experiment. Arguably, no professional epistemologist would be seriously tempted to interpret (ford) in any of the deviant ways that are left open by this description. Moreover, the way in which we amended the initial description (ford) should be readily available and transparent to every professional epistemologist. It therefore seems quite plausible that professional epistemologists tacitly interpret (ford) in a way that roughly corresponds to our improved description (ford-iii).

Third, although philosophical experts are unlikely to interpret descriptions like (Ford) in deviant ways, improved case descriptions might nevertheless help prevent philosophical laypersons from misinterpreting the relevant descriptions. In this way, an improved case description like (ford-iii) might help to avoid potential confounds in experimental studies that test the Gettier judgments of philosophical laypersons (see, e.g., Weinberg et al. 2001).

Finally, since the problem of deviant instances can be avoided in this way, there are also some positive reasons in favour of reconstructing the Gettier judgment in terms of (NGJ). First, in contrast to Williamson’s counterfactual approach, (NGJ) makes the truth of the Gettier judgment independent of contingent facts about the actual world. This seems to be more faithful to the philosophical practice of thought experimentation, where we treat contingent features of the actual world as completely irrelevant to the outcome of the experiment (cf. Ichikawa and Jarvis 2009; Malmgren 2011). Second, reconstructing the Gettier judgment in terms of (NGJ) seems psychologically more adequate than Malmgren’s possibility approach, for it does not collapse our seemingly more complex reasoning leading to the conclusion (GC) into the single step from ‘◊ (ford ∧ (Something is JTB but not K))’ to ‘◊ (Something is JTB but not K)’.Footnote 12 For these reasons, improved case descriptions might also help to restore (NGJ) as a serious contender in the debate about the rational reconstruction of Gettier thought experiments.

Notes

This description is taken from Malmgren (2011, p. 272), following Lehrer (1965, pp. 169–170). We have slightly modified Malmgren’s description, in which the last sentence reads “Jones’s Ford was stolen and Jones now drives a rented Ford”, in order to accommodate the fact that one does not cease to own a car just because it was stolen. Thanks to Peter Klein for this point.

There is also an issue about the meaning of proper names that figure in descriptions of thought experiment cases, such as ‘Smith’ or ‘Jones’ (cf. Williamson 2007, p. 184). Since this issue is tangential to the present paper, we will simply ignore it in the following.

A specific version of this proposal is endorsed by Ichikawa and Jarvis (2009). The two main alternatives to (NGJ) are to understand (GJ) either as a counterfactual conditional (roughly: ford □→ (Something is JTB but not K); cf. Williamson 2007) or as a claim of metaphysical possibility (roughly: ◊ (ford ∧ (Something is JTB but not K)); cf. Malmgren 2011).

See Malmgren (2011) and Horvath (forthcoming) for a more systematic discussion of this point.

See Malmgren (2011, pp. 275–276) for this terminology.

Other authors agree (see, e.g., Ichikawa and Jarvis 2009; Malmgren 2011). Ichikawa and Jarvis add the qualification that “[i]f one is clever and careful enough, one might be able to generate texts that are not susceptible to bad satisfaction” (2009, p. 224). Since they do not in any way explore this possibility, it seems fair to interpret them as at least skeptical about the feasibility of case descriptions without deviant realizations.

Thanks to Timothy Williamson for prompting us to make our overall strategy more explicit.

One might worry that this strategy is not in line with the original intention behind the Gettier thought experiments, for it may seem that Gettier wanted to simultaneously probe our intuitions about both knowledge and justification. However, Gettier explicitly introduced two non-trivial principles about justification, namely fallibilism and closure, in order to strongly incline us to attribute justified beliefs to Smith. This indicates that Gettier did not treat the question of whether Smith’s beliefs are justified as an open question. Thanks to Peter Klein for discussion on this point.

One might worry that on accounts of justification that rule out the possibility of justified false beliefs (cf. Sutton 2007; Littlejohn 2012), the amended version of (ford) simply becomes incoherent, because it implies that Smith has the justified false belief that Jones owns a Ford. Notice, however, that the strict conditional (NGJ) would still be true in that case, and so this would not give rise to another deviant instance of (ford). Rather, it would falsify the possibility premise (PG) of the Gettier reasoning.

This final version of (ford-iii) owes a lot to the penetrating comments of Jens Kipper and Timothy Williamson. In addition, Ernest Sosa helped us to see more clearly that what is relevant here is the metaphysical rather than the causal basis of knowledge (see also Sosa ms).

For this worry about trivialization, compare Malmgren (2011, pp. 288–289).

Malmgren (2011, p. 291) argues persuasively that another psychological aspect of the Gettier judgment (GJ), namely its implicit generality, is not sufficient evidence for the superiority of the (NGJ) proposal—for the same phenomenon also arises with respect to Gettier cases that are known to be actual, e.g., real-life instances of the Ford case. Since we have no tendency to reconstruct our judgments about actual cases as necessity judgments, the best explanation of their implicit generality cannot lie in the content of these judgments, as the (NGJ) proposal would suggest, but rather in our grounds for these judgments.

References

Gettier, E. (1963). Is justified true belief knowledge? Analysis, 23, 121–123.

Goldman, A. (1976). Discrimination and perceptual knowledge. The Journal of Philosophy, 73, 771–791.

Horvath, J. (forthcoming). Thought experiments and experimental philosophy. In C. Daly (Ed.), The Palgrave handbook of philosophical methods. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Huemer, M. (2007). Compassionate phenomenal conservatism. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 74, 30–55.

Ichikawa, J., & Jarvis, B. (2009). Thought-experiment intuitions and truth in fiction. Philosophical Studies, 142, 221–246.

Lehrer, K. (1965). Knowledge, truth and evidence. Analysis, 25, 168–175.

Littlejohn, C. (2012). Justification and the truth-connection. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Malmgren, A.-S. (2011). Rationalism and the content of intuitive judgements. Mind, 120, 263–327.

Nozick, R. (1974). Anarchy, state, and utopia. New York: Basic Books.

Sosa, E. (ms). The metaphysical Gettier problem and the X-phi critique.

Sutton, J. (2007). Without justification. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Thomson, J. J. (1976). Killing, letting die, and the trolley problem. The Monist, 59, 204–217.

Tucker, C. (2010). Why open-minded people should endorse dogmatism. Philosophical Perspectives, 24, 529–545.

Weinberg, J., Nichols, S., & Stich, S. (2001). Normativity and epistemic intuitions. Philosophical Topics, 29, 429–460.

Williamson, T. (2007). The philosophy of philosophy. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Acknowledgments

This paper originated from a fully collaborative talk entitled “On the Logic and Structure of Thought Experiments” that Grundmann and Horvath presented at the workshop Thought Experiments and the Apriori at the University of Fortaleza in August 2009 and at the workshop Knowledge and Metaphilosophy—Workshop with Timothy Williamson at the University of Cologne in January 2010. In addition, Grundmann presented (part) of this material at the workshop Intuitionen in Wissenschaft und Alltag (Intuitions in Science and Everyday Life) at the University of Luxembourg in April 2011 and at Rutgers University in February 2013. Horvath wrote a first draft in the summer of 2012 that concentrates on the key idea from the earlier talk. Very helpful comments from and extensive discussions with the following colleagues enabled us to work out the significantly revised final version during Fall 2012–Summer 2013: Merrie Bergmann, Sandy Goldberg, Jonathan Jenkins Ichikawa, Jens Kipper, Peter Klein, Anna-Sara Malmgren, Ernest Sosa, Timothy Williamson, and an anonymous editor of Philosophical Studies. Finally, we would like to thank the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation) for supporting our research on the topics of this paper as part of the project Eine Verteidigung der Begriffsanalyse gegen die Herausforderungen des Naturalismus (A defense of conceptual analysis against the challenges from naturalism).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grundmann, T., Horvath, J. Thought experiments and the problem of deviant realizations. Philos Stud 170, 525–533 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-013-0226-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-013-0226-3