Abstract

In the Swedish educational system, teachers have the dual responsibility of assigning final grades and marking their own students’ national tests. The Government has mandated the Swedish Schools Inspectorate to remark samples of the national tests to see if teacher marking can be trusted. Reports from this project have concluded that intermarker consistency is low and that teachers’ markings are generous as compared to those of the external markers. These findings have been heavily publicized, leading to distrust in teachers’ assessments. In the article, we analyze and discuss the remarking studies from methodological as well as substantive angles. We conclude that the design applied in the reanalysis does not allow inferences about bias in marking across schools or teachers. We also conclude that there are several alternative explanations for the observation that teacher marks are higher than the external marks: The external markers did not form a representative sample, they read copies with sometimes marginal legibility, and they used a different scale for marking than the teachers had used. The results are thus not as clearcut as suggested by the reports and media releases, which is because a school inspections logic rather than a research logic was applied in designing, conducting, and reporting the studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Trusting teachers’ assessments of their own students’ performances is a much-debated issue as well as a deep-rooted tradition in many countries (Choi 1999; Harlen 2005; Koretz et al. 1994). The starting point of the present paper is the Swedish educational system, where teachers are responsible for assigning final grades, essential for students’ future choices and opportunities, as well as for marking the national tests that are provided to support their grading decisions. However, this dual responsibility has recently been challenged.

Observations indicating lack of consistency across teachers and schools in the marking of the national tests and grading of students led the Government to mandate the Swedish Schools Inspectorate (SSI) to remark samples of national tests. Reports from this project conclude that interrater consistency is low and, furthermore, that teachers tend to overestimate their own students’ levels of performance. The findings of the SSI have been heavily publicized, leading to distrust in teachers’ assessments at the political level as well as among the general public, and among teachers themselves.

In the current article, we discuss the SSI studies from methodological and substantive angles. One main conclusion is that the results are not as clearcut as reported because of a suboptimal design of the studies and because a school inspection logic rather than a research logic has been applied.

1.1 Background and context

Up to the early 1990s, the Swedish educational system was a highly centralized and regulated system, but after a decentralization process, starting in the late 1980s, it has been described as one of the most decentralized and deregulated educational systems of the world (OECD 1998). In 1990, it was decided that teachers and all other school personnel were to be employed by the municipalities and that the municipalities were to obtain a general sum for funding school activities. In 1991, a system of school vouchers was introduced to increase the possibilities of school choice. It was also decided that not only municipalities would be allowed to run schools but also that independent schools owned by companies and organizations could operate under the same voucher system. Since the introduction of this system, the independent schools have successively increased their share of students to currently around 13 % in compulsory school and around 26 % in upper secondary school, so they now form a significant part of the Swedish educational system. In 1994, curricula and syllabi were deregulated too through the newly adopted curriculum Lpo94. While previous national curricula had provided rather detailed specifications, Lpo94 defined goals to be achieved and goals to be strived for, but avoided specification of content and method. The previous norm-referenced grading system was replaced with a new criterion-referenced grading system, which required local interpretation and implementation. The criterion-referenced grades, awarded from school year 8 and onwards, were meant to be used for purposes of monitoring the quality and equality of educational achievement.

In this highly decentralized system, the government still kept responsibility for the equality and quality of the education offered by the municipalities and other providers of education. During the 2000s, there has been a development, which has been described as a recentralization of the Swedish educational system (Rönnberg 2011), through introduction of new means of control through accountability and output control (cf. Ozga et al. 2011; Segerholm 2010). Thus, several systems and tools for follow-up and evaluation of quality and equality of education have been implemented, such as national tests at more age levels than before, and systems for planning and following up the work of the individual students. Another important accountability system is the Swedish Schools Inspectorate (SSI), which was established as a large-scale operation in 2008, with the main assignment to regularly inspect operations and outcomes of Swedish schools (SOU 2007:101).

As has already been mentioned, teachers in Sweden are mandated to assign students’ grades, which are used for high stakes purposes such as selection of students for higher education and evaluation of schools and municipalities. This is a firmly established tradition that was supported in the early 1950s by the introduction of a norm-referenced grading system, explicitly designed for purposes of rank-ordering, and selection of students (SOU 1942:11). The norm-referenced system assumed a normal distribution of grades at national level, which was unchanged over the years. To support the equivalence of grading of students from one class to another, teachers had access to standardized national tests. These had the main function of determining the level of achievement of the class, while the grading of individual students was primarily based on classroom assessments.

This norm-referenced system was robust, and it “…offered teachers a workable scheme in which their professional judgment could play a major role” (Kilpatrick and Johansson 1994, p. 26). Among the reasons why it was abolished in the mid-1990s was the fact that it did not serve other functions than rank-ordering of students well and that norm-referencing was seen as stimulating competition rather than cooperation.

In the new criterion-referenced grading system, which was introduced in the mid-1990s, teachers assess whether criteria for different levels on the grading scale have been reached or not. National tests were offered to support the comparability of the teacher assigned grades, but there were no regulations or guidance concerning how and to what extent national test results should influence decisions concerning individual students’ grades or the distribution of grades in the class or the school. In most subjects, the national tests were also changed into more performance-based assessments, which required teachers to make assessments of complex oral and written student production or interaction. The national tests were also assigned additional roles and purposes than guiding teachers’ grading of their students’ competences, such as supporting the implementation of the new system of grades and enhancing students’ learning.

The first cohorts of students to obtain the criterion-referenced grades left compulsory school in 1998 and upper-secondary school in 1997. The new grading system has been afflicted by several problems, such as grade inflation (Cliffordson 2004) and suffering comparability of grades assigned by different teachers and schools (National Agency for Education 2007). Since the results on the national tests in grade 9 were being collected on the population level from 2003 and onwards, considerable deviations have also been observed between national test results and teacher assigned grades. There are striking deviations at student level, and particularly so for mathematics. For example, in 2011, 19 % of the students had a nonpass score on the test, while 5 % were given a nonpass final grade. On the test, 11 % had the highest grade (pass with special distinction), while 15 % got this grade by the teachers. For English, there were fewer and more balanced deviations. It has also been noticed that there are substantial variations in the outcomes from one year to another for some of the national tests, while grades tend to be more stable from one year to another (National Agency for Education 2011).

Substantial differences between national test results and final grades have also been observed at the school level (National Agency for Education 2007). Given the systematic differences in the results on the national tests and the final grades, this is of course to be expected, but the amount of difference also seems to vary across schools. This has caused suspicion that some schools, and independent schools in particular, systematically apply lenient grading in order to become attractive in school choice; This is also the impression that has been established through media. While there is evidence of school differences in leniency of grading, this seems to be because some schools with a high proportion of students with low socio-economic background assign higher grades than is warranted by the national test results (Klapp Lekholm and Cliffordson 2008). There is, however, no empirical evidence that independent schools are more lenient in their grading than municipal schools (National Agency for Education 2011), the observed pattern being that for Swedish, independent schools tend to be slightly more lenient than municipal schools, while for mathematics, municipal schools tend to be slightly more lenient than independent schools.

There is no central marking of the national tests, and, in the large majority of all cases, teachers mark their own students’ tests (with some variation, however, with tests of writing in Swedish and English being more frequently co-rated). There are strong recommendations concerning co-rating among teachers and schools but no binding regulations. However, the national tests comprise extensive guidelines for teachers, touching on issues of purpose, construct, rubric and use. In addition, comments are given on different types of responses and ratings, and a considerable number of benchmarks are presented to strengthen the accuracy and consistency of teachers’ markings.

The national tests are developed by different universities in the country, commissioned by the National Agency for Education. Test development is done in collaboration with a number of stakeholder categories, e.g., teachers, teacher educators, researchers, and students. The opinions of the latter are systematically collected during piloting phases. The national tests are generally well received by teachers and students (OECD 2011). Results are analyzed and published in annual, publically available reports on the National Agency for Education website.

As is clear from this brief description that the criterion-referenced grading system is afflicted by several problems, and the trust in teachers’ grading has been negatively affected by these problems. Among the problems mentioned, the Government has chosen to concentrate on the potential bias caused by the fact that the teachers typically mark their own students’ national tests. Observations indicating lack of consistency across teachers and schools in the grading of students' performances as well as in the marking of the national tests thus led the Government to mandate the SSI to remark samples of national tests and to compare the externally assigned marks with the teacher assigned marks. This paper scrutinizes the methodology, conduct, outcomes, and logic of this operation, the main question being whether the conclusions drawn by the SSI can be trusted.

1.2 Are teachers more lenient when marking their own students’ tests?

There are substantial differences between different cultures and school systems with respect to views on teacher marking of tests. In systems relying on high stake standardized testing for student assessment, there tends to be scepticism to teacher involvement in test marking, and in the USA, this has become even more marked after discovery of cases of teacher cheating to improve student scores (e.g., Jacob and Levitt 2003). Following a recent reduction in emphasis on external standardized testing in England for 12–14 year olds, Gibbons and Marshal (2010) investigated teacher assessments of a writing task, comparing marking of own students’ scripts with marking of anonymous scripts. The results did not reveal any conclusive trend, some teachers being more lenient when marking their own students’ work, while others were harsher.

In Sweden, there has been a long tradition of trust in teachers’ marking, but as has already been noted, the question has been raised if teachers’ marking of their own students is unbiased. The National Agency for Education (2008) reviewed the available Swedish research on reliability issues in the marking of national tests. For mathematics, three studies were discussed, which all found a small tendency for the individual teacher to give a higher mark than was assigned by independent markers. In the field of English, one study was referred to, and here too a small tendency was found for the teachers to be more lenient in their marking than independent markers. This effect was in particular seen for a set of items, which only had general marking instructions. In Swedish, two studies were referred to, one of which showed relatively large differences between marks assigned by teachers and independent raters, the teachers being more lenient. The other study, however, did not demonstrate any such systematic difference, even though it showed that there were quite considerable inconsistencies among the marks assigned to the same test by different raters. Low interrater reliability has also been found in a study of an oral subtest in one of the national tests of mathematics in upper secondary school.

One main conclusion from the National Agency for Education (2008) study was that the results do not indicate that teachers’ marking of national tests is a major source of bias, even though there is a small tendency for teachers to assign higher marks than external markers. Another main conclusion was that there may be threats to the trust in the system of national tests by important stakeholders if the system of teachers’ marking comes to be regarded as unreliable. However, the high level of cost for introducing central marking of all national tests was regarded as prohibitive, and instead, a series of other measures were suggested to improve reliability and credibility of teachers’ markings, such as exchange of tests between teachers, increased collaboration in the marking between teachers and schools, sample based quality control of teachers’ markings, and instructions to the SSI to make inspection of the marking of national tests part of the regular inspection. The National Agency for Education (2008) also suggested that systematic research should be conducted on issues of marking of national tests.

In the preparatory work for the establishment of the Swedish Schools Inspectorate in 2008 (SOU 2007:101), it was suggested that it could include a function to secure the quality of marking of samples of national tests and to compare this with the grading in the different subjects. The major function would thus be to detect biased markings, which jeopardize the reliability of the system of national tests and particularly so at the school level. It was observed that no evidence is available to show that biased marking of national tests is a major problem (p. 177) but that the increasing competition on the school market may tempt schools to assign too high grades for economic reasons. Along the lines of the instructions from the Government, it was thus suggested that the SSI should include a function for quality assessment of the teachers’ marking of the national tests. A 3-year trial period was suggested, after which the project should be evaluated, and particularly so with respect to effects of the control marking on the quality of marking of tests and grade assignment. The Government followed the proposal and decided that samples of at most 10 % of the national tests should be made each year for 3 years, at a maximum cost of 20 mSEK per year.

1.3 The Government’s assignment to the Swedish schools inspectorate

According to the instruction from the Government, the SSI was to collect a sample of copies of already marked student papers and to remark these. The instruction also implied that the remarking of the student responses is to be a part of the running inspection activities of the SSI and that the results of the remarking can be made a basis for conducting deepened inspection activities within the regular inspections and thematic quality inspections.

According to the instructions, the remarking was to be made in three rounds, to be conducted during three successive years. In the first round, a sample was to be made among the obligatory national tests in compulsory school and in upper secondary school. The sampling was to be done in such a way that the results are representative at national level for each subject and grade and also at school level among the selected schools in Swedish, English, and mathematics in grade 9 and in upper secondary school. The sampling should also cover national tests in new subjects, which are under development.

Furthermore, the SSI was instructed to analyze the outcome of the remarking of a representative sample of student responses with respect to the presence of systematic misjudgement. To the extent that the SSI concludes that there is systematic bias in the marking, the SSI was instructed to conduct a closer analysis of these tests. If the results indicate need for a closer inspection, the SSI is to conduct the inspection on a new sample of schools.

1.4 The implementation and results of the remarkings in 2010

The report concerning the remarking of tests taken in the spring of 2009 was delivered to the Government in April 2010 (Swedish Schools Inspectorate 2010). It was based on remarking of some 29,000 national tests from 633 schools. The national tests were Swedish, mathematics, and English in grades 3 (not English), 5, and 9 and the first obligatory course in the same subjects in upper secondary school. The results were reported in terms of deviations between the original teacher marking and the remarking. The reporting was done at school level, and the number of negative (i.e., original teacher mark higher), positive (i.e., original teacher mark lower), and agreeing marks were tabulated for each school.

For several reasons, the sample of tests was not fully representative of the population. All schools that were asked to send copies of student responses did not comply, and some sent the material too late, or only for subsets of the students. In some cases, the copies were too difficult to read to be included in the study. Statistics Sweden conducted analyses of the representativeness of the obtained sample of test responses, using register data for the population, and on the basis of these analyses, they concluded that the sample was reasonably representative at national level for most subjects.

The major finding was that the remarking resulted in substantial differences between the original teacher mark and the control mark for those subtests where the student is to produce a longer text in Swedish and English in grade 9, and in Swedish, English, and mathematics for upper secondary school. The same tendency, but not equally pronounced, was observed for grades 3 and 5.

The observed differences were both positive (the original teacher mark being lower than the mark assigned by the SSI) and negative (the original teacher mark being higher), but negative differences were much more common, and particularly so for the subtests in grade 9 and upper secondary school. It was also observed that the negative differences were larger in the upper part of the scale of marks, in particular with regard to the highest mark.

The SSI concluded that it is not possible to determine whether it is the original mark or the control mark that is correct, but they nevertheless emphasized that the fact that the outcome very much depends on which teacher does the marking is worrying from a comparability perspective. The SSI also concluded that the results throw doubts on whether the national tests are constructed in such a way that they can fulfill their main aim of supporting grading, which is comparable and fair. They identified three main problems in the construction of the tests that may explain the discrepancies found.

The first problem is that, at the time of the first data collection, the national tests had a wide range of aims: In addition to providing support for teachers in their grading of students, the tests were aimed to increase student learning, concretize goals and grading criteria, and provide a basis for evaluation at individual, school, municipal, and national levels. The SSI emphasized that it may not be possible to reach all these aims with one and the same test.

A second problem emphasized by the SSI was that the tests and the marking instructions leave wide margins for interpretation, which does not support comparable judgements. This applies in particular to tasks in which the students are to provide their responses through writing a longer text.

The third problem identified by the SSI is that the teachers are less objective. The SSI refers to anecdotal evidence from teachers hired as control markers, saying that they interpret the marking instructions more strictly when they are control markers than when marking their own students’ tests because in the former case they do not have a relation to the student.

The SSI also concluded that the differences between the original marks and the control marks vary between schools, there being few differences for some schools and substantial differences for other schools. In the report, this phenomenon is not analyzed further, but it is stated that the SSI will follow up the marking in schools with large differences.

The report ends with a set of recommendations: (1) the primary purpose of the tests should be clarified; (2) the tests should be constructed in such a way that the primary purpose can be reached; and (3) a marking system where the identity of the student whose test is marked is not known should be introduced.

1.5 The implementation and results of the remarkings in 2011

Another conclusion of the 2010 report was that the sampling for the next round of remarking should be conducted in the same way as the first round. The report concerning the remarking of tests taken in the spring of 2010 was delivered to the Government in April 2011 (SSI 2011). It was based on the remarking of some 35,000 national tests from 750 schools, and the procedures followed were the same as those applied the previous year.

The results 2010 and 2011 were more or less identical. The report emphasized that there were substantial differences between the original marking and the remarking for certain subtests, and particularly for those in which the student is to respond in the form of an essay. It was thus observed that there were differences in about 50 % of the tests of Swedish in upper secondary school. In about 20 % of these cases, the marks differed by more than one step on the four-point scale. Furthermore, the differences were in most cases negative, meaning that the SSI assigned a lower mark than did the teacher.

The report also concluded that there were large differences between schools in the amount of deviation between the two markings. Here, too, however, the SSI concluded that the study does not make it possible to determine whether discrepancies observed for single schools are systematic or not.

The three main conclusions from the first report were repeated in the second report.

1.6 Reflections on the design and conclusions of the SSI studies

The main conclusion drawn by the SSI was that the mark assigned to a student’s subtest to a large extent is connected with the individual marker, and the SSI therefore questioned whether the national tests can be claimed to support comparable marking and grading.

There are, however, two problems with this conclusion. The first problem concerns the claim that there are differences between teachers in which marking standards they apply. It is indeed a well-established fact that comes out of almost any study of rater characteristics that some are more lenient (doves) while others are more harsh (hawks), and this holds true not only for educational assessment but for other areas as well (see, e.g., Kane et al. 1995). But if this holds true, in general, it is highly plausible that there is also variation in leniency among the teachers recruited by the SSI to do the remarking.

This raises several questions. The first is if the sample of teachers employed by the SSI is representative of the whole population of teachers. According to the 2010 report, a private company recruited 211 teachers to conduct the remarking (178 teachers in the 2011 report). These teachers were to have a teacher education adequate for the subject and grade, as well as experience in marking tests in the subject and grade that they were to remark. They did the remarking in their homes but were supported by SSI personnel through digital communication. While the two SSI reports present careful analyses of the representativeness of the samples of students and schools, no attention is directed to the characteristics of the sample of teachers for the remarking. Given that this sample is more or less self-selected, it is not likely to be representative of the general population of teachers in the investigated subjects and grades, but it is, of course, impossible to tell in what respects it differs from the population.

Another important question is how the remarking teachers were matched with the marking teachers and the tests. This is not clearly described in the reports, but according to information from the SSI, the remarking teacher remarked all the subtests of a particular national test. Also, a remarking teacher was allowed to remark a maximum of 10 tests from a particular school, in order not to allow too strong an impact of a particular remarking teacher on the results for a certain school. This information indicates that the SSI is aware that the selection of remarking teachers might influence the results. However, in spite of this, they did not systematically design the study to take possible variability among the remarking teachers into account.

From a design perspective, it would have been optimal to use as many remarking teachers as possible for the students from each school. In the first study, for example, there were 34 schools in the sample of English national tests in grade 9, with an average of 70 students in each school (range, 29–128). With the large number of remarking teachers available, this would have made it possible to assign zero, one or two tests from each school to each remarking teacher and also to create overlap such that certain tests were marked by more than one remarking teacher. With such a design, it would have been possible to get estimates both of the variation in leniency among the remarking teachers and of the variation in leniency in the original marking of the tests among the schools (Braun 1988).

It may also be noted that different samples of schools were selected for the different national tests. Such a sampling design has the advantage that the amount of work for each sampled school is smaller than if the school were to copy the results for all the national tests for each student. However, it is not obvious that such a sampling design is optimal, given that the purpose is to study variation among teachers and schools in the marking of national tests. If each school is represented by one subject matter only, there is no basis for investigating whether school differences are consistent over subjects. Furthermore, given that each school is represented by the few teachers who teach a particular subject matter, school differences will, to a large extent, be confounded with teacher differences. Another possibility would have been to include tests from all subjects from each school, but not necessarily include all students within each school. Such a design would allow inferences about between- and within-school differences in the marking of national tests, information that seems essential to be able to interpret the findings.

The second problem with the SSI conclusion that the national tests do not support comparable marking and grading is that this conclusion is based on results from analyses of certain components of the full test only. However, the support for grading is typically assumed to be provided by the results on the full tests, and not by the results on a single component. For example, for English the written composition test is assumed to contribute 25 % of the score points. Given that there are considerable differences in the design of the different national tests, the effects of unreliability of scoring must be evaluated for each national test separately, but this has not been done by the SSI.

The data collected by the SSI should be reanalyzed with a focus on differences between different remarking teachers and on differences in outcomes for different subtests within and between schools. Currently, we do not have access to data, which allow the first type of analyses, but from the information in the published reports, we can take a closer look at the second question.

1.7 A closer look at outcomes for different subtests

We focus on the results for the grade 9 tests in English and Swedish. One reason for this is that in the assignment to the SSI special emphasis was put on the national tests given at the end of comprehensive school, and in particular on the analysis of school differences. Another reason is that, for these two tests, results are presented for two subtests each, which makes it possible to investigate degree of consistency of school differences in amount of deviations between the original marking and the remarking. For the national test in mathematics, only a global result is presented, so data for this test is regrettably not useful for the current purpose.

The national test of English for grade 9 consists of three parts, measuring oral interaction and production (Part A), receptive skills when reading and listening (Part B), and written production (Part C). There is no documentation of student performance on Part A, so it was not included in the remarking, but Parts B and C were. Part B consists of two sections, listening comprehension (in total about 35–40 items) and reading comprehension (about 55–60 items), the number of items per skill varying marginally from 1 year to the other. In this part, the students respond by writing shorter or longer answers or by fixed response options (multiple choice, matching). In Part C, the students write a longer text, choosing from two alternative topics, one allowing some more freedom and one being more structured.

The national test of Swedish consists of three subtests. Subtest A tests reading comprehension of different types of texts, and the student’s ability to express his/her own reflections about texts. The questions asked are almost exclusively open ended. Subtest B is conducted in groups and assesses the ability to communicate orally. This subtest is not included in the remarking. Subtest C is a written essay, which tests the ability to develop and express thoughts and ideas and to produce narrative and descriptive text. The students typically have four alternative topics to choose between. This subtest is included in the remarking, which thus comprises subtests A and C.

The SSI reports present tables in which the results for each school and subtest included in the remarking are reported: the number of negative differences (original mark higher), positive differences (original mark lower), and the number of marks in agreement. The information in these tables has been the starting point for computing the difference between the percentage of positive differences and the percentage of negative differences. These net differences thus express the balance between the number of original marks lower than external marks and the number of original marks higher than external marks, negative numbers expressing lower marks in the remarking, and positive numbers expressing higher marks in the remarking.

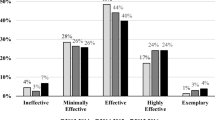

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for these percentage differences for English B and C and for Swedish A and C for the two rounds of remarking. The mean values are all negative, indicating that the marks assigned by the teachers tend to be higher than the marks assigned by the SSI. There are, however, substantial differences between the different tests and subtests in the magnitude of differences. For English Part B, the means are close to zero, while for English Part C, they are around −13 %, indicating a tendency for higher teacher than SSI marks. For both the Swedish subtests the means are around −20 % in the first round and −24 % in the second round, indicating that marks assigned by the teacher are higher than marks assigned by the SSI.

The standard deviations express the variation in degree of imbalance at school level, as do the minimum and maximum values. The standard deviations are substantial, indicating that the original marking in some schools is much more lenient than the SSI marking, while in other schools the original marking is less lenient than the SSI marking. The minimum and maximum values provide the same impression in a more concrete manner. It is interesting to note that the standard deviations are quite similar for most subtests with values around 17. The English B subtest forms an exception, though, with standard deviations around 6.

Table 1 also presents correlations between subtests within each national test. If schools have balances of mark differences in the same direction for the subtests, correlations will be high, but if the balances do not go in the same direction for the schools the correlations will tend towards zero. For English, the correlations are low (around .25) and nonsignificant. For Swedish, the correlations are somewhat higher and particularly so for the second round (.37 and .58 for the two rounds, respectively), and both are statistically significant. However, even the highest correlation implies that only around 34 % of the variance in the two subtests is common.

In summary, these results show that particularly when students produce longer texts, the teacher-assigned marks tend to be higher than those assigned in the SSI remarking. However, with the exception of the second remarking of Swedish, the school-level differences were not consistent over subtests.

Both in 2010 and 2011, a second remarking was made in those cases when there were large differences between the teacher and the SSI marks. A large difference was defined as being present when one of the markers gave a “fail” mark and the other not, or if one of the markers gave a “pass” mark and the other a “pass with special distinction” mark. All the subtests of a test went through the second remarking if one of the subtests satisfied the criteria for a large difference. This procedure was adopted to prevent the second remarker from knowing that a remarking was done, which could affect the marking. Table 2 presents information about the outcomes of the second remarking.

The SSI reporting differs between the two rounds of remarking. For 2010, the number of subtests involved in the second remarking is the same for each test (i.e., 270 for English and 735 for Swedish). However, this is not the case for the 2011 remarking where the number of subtests in the second remarking varies (e.g., 78 for English B and 317 for English C). For 2011, there is, furthermore, no reporting of what percentage of subtests all three markers agreed.

There can be two explanations for the differences between the two rounds. One is that the SSI for the 2011 reporting chose to include the results only for those subtests, which satisfied the criterion of a large difference, and excluded the results for those subtests that were included in the second remarking only because another subtest in the test had shown a large difference in the remarking. The other explanation is that the SSI, in spite of what is stated in the report, in 2011 only did the second remarking for those subtests in which a large difference was found. However, the SSI project leader for the remarking has in personal communication confirmed that exactly the same procedures were followed in the two rounds, so this explanation must be rejected.

The results show that, for English B, the third marker clearly supported the SSI more often than the original teacher marking. For English C, the third marker supported the SSI remarking, and the original teacher marks equally often. For both Swedish subtests, the third markers also split their votes equally between the SSI remarking and the original marking in 2010, but not in 2011. For the second round the third marker more often agreed with the remarking than with the original marking.

The findings for English B may, perhaps, be accounted for by a hypothesis that the two remarkers were more careful in the marking than the teachers were and that they both therefore detected the minor, more or less random, mistakes in marking that the teachers had made. Another explanation may be related to the interpretation of personal handwriting, where the original teacher is more accustomed to understanding their own students’ answers.

The differences in the pattern of outcomes for Swedish in the two rounds are more difficult to explain if indeed exactly the same procedures were followed in the two rounds. One tentative explanation may be that the teachers who acted as third markers, on the basis of experiences made in the first round of remarking and contextual information, could infer when an ordinary remarking was done, and when a remarking of a large discrepancy was made. If that is the case, it may be suspected that this caused bias in the second remarking.

2 Discussion and conclusions

Below, we discuss the results and interpretations of the empirical results, we comment on the way the SSI study has been conceived and conducted, and we reflect on the issue of trust.

2.1 Reliability and bias in marking of tests

The results presented above are in agreement with the results presented by the SSI in showing that subtests involving production of longer texts are assigned lower marks by the external markers than by the students’ teachers. However, our results, somewhat unexpectedly, show that there is little consistency in school differences between external and internal marking for different subtests. This is clearly the case for English while for Swedish there is low positive correlation in the first round of remarking, and a higher correlation at the second round.

The result that marking of longer essays tends to be less reliable is a well-established fact, many studies indicating that interrater reliabilities do not exceed .50 (Braun 1988; Meadows and Billington 2005). A recent study conducted in collaboration between the Swedish National Agency for Education and the university departments responsible for the development of the national tests investigated interrater consistency in different national tests and provides interesting results for comparison (The National Agency for Education 2009). The study included, among others, English, mathematics, and Swedish in grade 9. One hundred randomly selected, teacher-marked tests were analyzed and rated by two or three independent raters. The results (National Agency for Education 2009; Erickson 2009) showed high interrater consistency for English and mathematics, whereas the interrater reliabilities were distinctly lower for Swedish. As for subtests focusing on the production of a longer essay, interrater reliabilities varied between .86 and .93 for English and between .36 and .46 for Swedish.

While reliabilities around .50 is lower than is normally required in high-stakes measurement situations, it does seem to be a reflection of the inherent difficulty of the task to assign a complex and multifaceted piece of work into a small set of categories representing different marks. In this context, it should also be observed that the remarking conducted by the SSI was done on a scale with four categories (i.e., the four marks Fail, Pass, Pass with Distinction, and Pass with Special Distinction), while the teachers’ original marking of the national tests was done on a well-established ten-point scale used since the introduction of the test in 1998. In this scale, a distinction is made between two levels (weaker and stronger) for the Fail and Pass with special distinction levels and three for the Pass and Pass with distinction levels. Given that classification into fewer categories, contrary to intuitive believes, always yields a lower inter-marker reliability than classification into a larger number of categories, this provides another explanation for the low observed reliability in the SSI study. As an example, it could be mentioned that using a four-point scale in the study of the national test of English referred to above would decrease the correlations for Part C/Writing/by about .10, from .86–.93 to .78–.82.)

Let us also add that even though reliabilities around .50 are typically considered to be unacceptably low in a high-stakes situation, there are other high-stakes situations where reliabilities are even lower. For example, Jayasinghe et al. (2001) have shown that the interrater reliability of peerreviews of proposals for research funding is around .20. Such low reliabilities necessitate use of multiple raters, and in well-designed systems for evaluation of research proposals, a sufficient number of reviewers is used to achieve satisfactory reliability. While only a single marker (i.e., the teacher) is used in the Swedish grading system, the final grade not only depends on the results obtained on the national test but also on the results obtained on other written composition tasks conducted over several years, and also, of course, on assessment of other competences than written composition. Thus, even though the results show that the reliability of marking a single essay may be low, the fact that the grade is based on assessment of performance on multiple tasks indicates a higher reliability in the teacher assigned grade.

However, the result most heavily emphasized by the SSI is not the low intermarker reliability but the finding that the marks assigned by the external markers tend to be lower than those assigned by the teachers. While the published reports do not make strong claims that the teachers are too lenient in their marking, this is nevertheless the message that has been conveyed by the SSI to media.

As mentioned earlier, several small-scale studies on interrater consistency have been conducted by the national testing teams at different universities in Sweden as part of the regular validation successively undertaken. Results have shown a weak tendency of teacher leniency in marking their own students’ tests. The same tendency has been demonstrated in other contexts and countries, as reported for example by McKinstry et al. (2004) and Harlen (2005). In the study by the National Agency for Education (2009), teachers’ ratings were found to be somewhat higher than those by external raters and particularly so in Swedish.

There are several different interpretations of the difference in leniency between internal and external marking. One is, of course, the one that, at least implicitly, seems to be favored by the SSI, namely, that teachers are positively biased in the assessments of their own students. Another possible interpretation is that the external markers are negatively biased in their assessments because they have interpreted their remarking assignment in such a way that they become harsher in their assessments. The anecdotal evidence reported by the SSI provides some support for this interpretation. Another interpretation along a similar line is that the self-selected sample of external markers is harsher than the general population of Swedish teachers.

Other interpretations are also possible. The fact that the external markers used a four-point scale while the original teacher ratings were done on a ten-point scale causes underestimation of intermarker reliability, and it may also have affected leniency. The re-marking was done on the basis of copies of the hand-written student papers, some of which were more or less illegible. This may have affected the possibilities to interpret the text as intended, thereby lowering the mark (Meadows and Billington 2005). Along a similar line of reasoning, it may be hypothesized that familiarity with a student’s handwriting and modes of expression makes it easier to interpret the intended meaning, leading to a more positive evaluation.

Should it be that the amount of difference between external and internal marking is constant for all students and schools, this does not influence the rank ordering among students and schools, and in such a case, it does not matter whether external or internal marking is used. However, if the amount of difference in the marking of the national tests varies over schools, such that teachers at certain schools are more lenient, and others are less lenient, this may have consequences both for schools and for students, given that the final grades are regarded as important sources of information about the quality both of schools and students.

The results show that there is considerable variation among schools in leniency of marking of longer written texts. However, the results also indicate that these differences tend to be inconsistent across different subtests within each national test. We could note a higher level of consistency across subtests for Swedish than for English and particularly so for the 2011 round. However, the higher degree of agreement between the third marker and the SSI marking for the second round may be an explanation for this, and if that is the case, it indicates bias in the remarkings rather than in the original markings.

If the differences are inconsistent across subtests this lessens their influence on the mark for the full national test because unrelated differences will tend to cancel. Furthermore, if the differences are inconsistent across the three national tests set in grade 9, there will be less of a systematic effect of leniency than if the differences at school level go in the same direction. Regrettably, however, the SSI has chosen to design the study in such a way that we only know little about degree of consistency over subtests at school level, and nothing at all about degree of consistency across the different national tests.

To the extent that teachers differ in degree of leniency in their marking, this will cause some students to earn higher marks on the national test than other students with the same level of knowledge and skill. This is a source of unreliability that may be regarded as a problem of fairness in comparisons among individual students. Because there typically are few teachers within each school who mark tests within each subject, teacher differences also influence school differences. Again, however, we have to regret that the design used by the SSI is uninformative with respect to differences in leniency both among the teachers who did the original marking of tests, and the teachers who did the remarking.

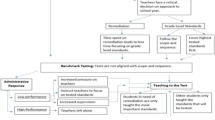

2.2 The logic of the SSI study

The SSI was given the assignment to investigate if there is bias when teachers mark their own students’ tests. However, it is not a trivial task to design a study, which unequivocally answers questions about bias in teachers’ markings. One major difficulty is that no objectively correct mark is available to which the teachers’ marks can be compared. Another major difficulty is that any observed difference between marks assigned by internal and external markers can be given multiple interpretations, for example, in terms of bias, marking skills, teachers’ previous experience of the students, and representativeness of the samples of markers. As has already been observed, it is possible to master such difficulties through adoption of designs developed in research on educational measurement in which certain scripts are marked by more than one external and more than one internal marker.

However, the SSI did not adopt methods and theories from the field of educational measurement to investigate the issue of bias. Instead, the SSI adopted theories and methods from the field of school inspections when trying to answer the question. Given that the SSI have failed to produce any useful answer to the question, at the same time as the reported findings have had an immense impact on the trust of the general public in teachers’ ability to assign unbiased marks, it is of interest to discuss the underlying logic of the SSI study.

In the field of school inspections a set of beliefs and theories have been developed about how inspection activities improve practices of schools, and methods and procedures have been developed in order to collect relevant information. These beliefs, theories, and methods differ in fundamental ways from the beliefs, theories, and methods used in research.

A first difference is that, while in research the participants are typically anonymous, this is not the case in school inspections. Thus, while researchers usually report aggregated statistical results in tables and graphs, the tables and graphs in the SSI reports present identifiable schools. This is likely to be due to the fact that school inspections typically use a “naming and shaming” approach to correct deviations from rules and regulations, both for the individual school and for the general impact on other schools. Such an approach is based on the assumption that knowledge is available about the correct way to do things, and the task of school inspection is to identify schools that do things in incorrect ways. Thus, it is not an aim of school inspection to search for new knowledge but to identify violations of rules and regulations, and to correct these. For the remarking project, the SSI adopted a typical inspection design, which may be useful for purposes of school inspection, but which is useless for purposes of developing knowledge about bias in the marking of tests.

A second difference is that, while in research much attention is focused on characteristics of the instruments used for data collection, such as reliability and validity, in school inspections, it is taken for granted that inspectors have the capacity to make the correct observations and interpretations. One reason for this is that research is an open activity in which the research community has the task to carefully scrutinize procedures, findings, and inferences in all kinds of research. School inspections are typically not challenged and scrutinized by fellow inspectors, and even though it has occasionally been observed that there is a need to attend to issues of validity and reliability (e.g., SOU 2007:101), this is rarely done. This may explain why the SSI in their reports focus all their attention on characteristics of the schools, the samples of tests and the teachers who contributed the original marks, but do not provide any information whatsoever about the teachers who did the remarking because as representatives of the SSI their marks must be both valid and reliable.

A third difference is that, while reports of research typically go through a long process of review before publication, the reports from the SSI go directly to media, where they often result in front-page headlines. This causes the reports to have high impact, and there are many indications that the reports on bias in teachers’ marking of national tests have caused loss of trust in teachers and in the national tests. Furthermore, while reports of research are often discussed at length in groups of specialists, there is little opportunity to discuss inspection reports, neither among specialists, nor among the general public.

In conclusion, the logic of designing, conducting and reporting school inspections is quite different from the logic of designing, conducting, and reporting of research. When the school inspection logic is applied to answer research questions, this leads to failure.

2.3 To trust or not to trust?

Assessment is an intrinsic part of the pedagogical process of learning and teaching, with two essential, complementary functions, namely, to enhance and support learning, and to measure, as fairly as possible, the outcomes of learning. Although the two functions differ in certain respects, it needs to be emphasized that they rest on the same basic principles of validity, reliability, transparency, and respect. Marking tests, i.e., evaluating and assigning points or grades to different qualitative levels of performance, is a crucial aspect of this, requiring a high degree of assessment literacy and credibility, or trustworthiness, among those who do the job.

The aim of the current paper is to investigate whether the methods and procedures used by the SSI to investigate the trustworthiness of teachers’ markings of national tests can be trusted. Our conclusion is that, because the SSI has relied on the logic of school inspections rather than on the logic of research to investigate trustworthiness of teachers, the results are both uninformative and untrustworthy. Furthermore, given that the results are interpreted within the logic of school inspections as showing the existence of severe deviations from the rules and regulations by certain schools, this creates distrust, without identifying ways to remedy shortcomings. This in turn carries the risk that solutions which are simplistic, unfounded, and not based on empirical evidence are resorted to. Furthermore, public naming and shaming of schools, and thereby of teachers’ competence to mark their students’ performances in a professional way, does not seem to be an ethical way of handling the complex situation of assessment and grading. As has been demonstrated by Elstad (2009), naming, blaming, and shaming of schools in media generates complex emotional processes based on shame, which may start improvement processes, but which may also bring about negative developments.

The observation that there are discrepancies between the national test results and the teachers’ grades seems to have been the reason for the Government to assign the task to SSI to launch the project of remarking national tests. However, when this decision was made there was no evidence to suggest that bias in teachers’ markings of their own students’ tests would affect their grading of their own students, and there still is no such evidence. There was, however, considerable evidence of fundamental problems in the system of national tests and the criterion-referenced grading system, and the most fundamental problem seems to be that in most subject-matter areas the national tests do not provide enough support for the teachers’ grading. These problems still remain to be solved, and we hope that the distrust in teachers and schools, and other negative consequences caused by the remarking initiative, will not prevent development of adequate solutions to the fundamental problems of assessment and grading in Swedish schools.

References

Braun, H. (1988). Understanding score reliability: Experiments in calibrating essay readers. Journal of Educational Statistics, 13(1), 1–18.

Choi, C. C. (1999). Public examinations in Hong Kong. Assessment in Education, 6(3), 405–418.

Cliffordson, C. (2004). Betygsinflation i de målrelaterade gymnasiebetygen [Grade inflation in the criterion-referenced grades in upper secondary school]. Pedagogisk Forskning i Sverige, 9(1), 1–14.

Elstad, E. (2009). Schools which are named, shamed and blamed by the media: school accountability in Norway. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 21(2), 173–189.

Erickson, G. (2009). Nationella prov i engelska—en studie av bedömarsamstämmighet. [National tests of English—a study of inter-rater consistency]. Retrieved 26 September 2011 from http://www.nafs.gu.se/publikationer

Gibbons, S., & Marshal, B. (2010). Assessing English: A trial collaborative standardised marking project. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 9(3), 26–39.

Harlen, W. (2005). Trusting teachers’ judgement: Research evidence of the reliability and validity of teachers’ assessment used for summative purposes. Research Papers in Education, 20(3), 245–270.

Jacob, B. A., & Levitt, S. D. (2003). Rotten apples: An investigation of the prevalence and predictors of teacher cheating. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(3), 843–877.

Jayasinghe, U. W., Marsh, H. W., & Bond, N. (2001). Peer review in the funding of research in higher education: The Australian experience. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 23(4), 343–364.

Kane, J. S., Bernardin, H. J., Villanova, P., & Peyrefitte, J. (1995). The stability of rater leniency: Three studies. Academy of Management Journal, 38(4), 1036–1051.

Kilpatrick, J., & Johansson, B. (1994). Standardized mathematics testing in Sweden: The legacy of Frits Wigforss. Nordic Studies in Mathematics Education, 2(1), 6–30.

Klapp Lekholm, A., & Cliffordson, C. (2008). Discrepancies between school grades and test scores at individual and school level: Effects of gender and family background. Educational Research and Evaluation, 14(2), 181–199.

Koretz, D., Stecher, B. M., Klein, S. P., & McCaffrey, D. (1994). The Vermont Portfolio Assessment Program: Findings and implications. Educational Measurement: Issues & Practice, 13, 5–16.

McKinstry, B. H., Cameron, H. S., Elton, R.A. & Riley, S. C. (2004). Leniency and halo effects in marking undergraduate short research projects. BMS Medical Education 4, 28.

Meadows, M. & Billington, L. (2005). A review of the literature on marking reliability. Report commissioned by the National Assessment Agency, UK

National Agency for Education (2007). Provbetyg – Slutbetyg- Likvärdig bedömning? En statistisk analys av sambandet mellan nationella prov och slutbetyg i grundskolans årskurs 9, 1998–2006.[Grades on national tests – Final grades - Equivalent assessment, A statistical analysis of the relationship between national tests and final grades in compulsory school Grade 9, 1998–2006 Rapport 300, Stockholm: National Agency for Education.

National Agency for Education. (2008). Central rättning av nationella prov. [Central marking of national tests]. Stockholm: National Agency for Education.

National Agency for Education. (2009). Bedömaröverensstämmelse vid bedömning av nationella prov [Inter-rater consistency in marking national tests]. Stockholm: National Agency for Education.

National Agency for Education. (2011). Skillnaden mellan betygsresultat på nationella prov och ämnesbetyg i årskurs 9, läsåret 2010/11 [The difference between results on national tests and subject grades in Grade 9, 2010/11. Stockholm: National Agency for Education.

OECD. (1998). Education at a glance. OECD indicators 1998. Paris: Centre for Educational Research and Innovation, OECD.

OECD. (2011). OECD reviews of evaluation and assessment in education—Sweden. Paris: OECD.

Ozga, J., Dahler-Larsen, P., Segerholm, C., & Simola, H. (Eds.). (2011). Fabricating quality in education. Data and governance in Europe. London: Sage.

Rönnberg, L. (2011). Exploring the intersection of marketisation and central state control through Swedish national school inspection. Education Inquiry, 2(4), 689–707.

Segerholm, C. (2010). Examining outcomes-based educational evaluation through a critical theory lens. In: Freeman, M. (Ed.) Critical social theory and evaluation practice. New Directions for Evaluation, 127, 59–69.

SOU (1942:11). Betygsättningen i folkskolan. Betänkande av 1939 års betygssakkunniga. [Grading in elementary school. Report from the 1939 commission on grading] Stockholm: Statens Offentliga Utredningar.

SOU (2007:101). Tydlig och öppen. Förslag till stärkt skolinspektion. [Transparent and open. Reinforcing school inspection, commission report]. Stockholm: Utbildningsdepartementet.

Swedish Schools Inspectorate (2010). Kontrollrättning av nationella prov i grundskolan och gymnasieskolan. [Control marking of national tests for comprehensive school and upper secondary education]. Retrieved 26 September 2011 from http://www.skolinspektionen.se > Publikationer.

Swedish Schools Inspectorate (2011). Lika eller olika? Omrättning av nationella prov i grundskolan och gymnasieskolan. [Remarking of national tests for comprehensive school and upper secondary education]. Retrieved 26 September 2011 from http://www.skolinspektionen.se > Publikationer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gustafsson, JE., Erickson, G. To trust or not to trust?—teacher marking versus external marking of national tests. Educ Asse Eval Acc 25, 69–87 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-013-9158-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-013-9158-x