Abstract

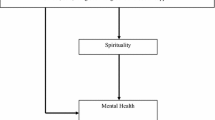

Spiritual health is considered a major asset that is associated with an individual’s perception of their health status. Social health and general health are also two important dimensions of health through which we measure our individual and social performance in the life. The measurement of spiritual and social health in past studies has been done by non-native questionnaires (it means they weren’t developed by Iranian researchers), even though these dimensions are highly dependent on Iranian culture. The purpose of this study was to investigate the ability of spiritual health to predict the general and social health of students from Iran University of Medical Sciences in the 2017–18 academic year, using two native questionnaires plus an existing questionnaire. The statistical population of this cross-sectional method consisted of students from Iran University of Medical Sciences. For this purpose, 233 students were selected using a stratified random sampling method. To collect the data, questionnaires on spiritual health, social health, and general health were employed. Data were analyzed using the Pearson correlation and regression methods. Findings indicated a significant relationship between spiritual health and social health (P < 0.01), spiritual health and general health (p < 0.05), and social health and general health (P < 0.01). In addition, spiritual health was a significant predictor of social health and general health, although the prediction power was low. Investigating the role of health dimensions in students using native questionnaires is an important subject. Spiritual health appears to be associated with general, mental, and social health. This relationship also allows the prediction of other dimensions of health in students based on spiritual health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In Islam, the concept of health is defined to include both physical and spiritual health. The spiritual dimension of health enables humans to perceive life events as normal and as opportunities to promote their overall well-being. This dimension is therefore valuable for humans and has been emphasized in Islam (Sadat Hoseini et al. 2015). According to a study conducted in Iran, spirituality refers to the “supreme dimension of humans’ existence that has been trusted with them to go through perfection, which is proximity to God” (Memaryan et al. 2016). Moreover, spiritual health means establishing relationships with others, having goals and a sense of meaning in life, and believing in and having relationships with a supreme power (Jafari et al. 2010). Spiritual health is considered a major positive asset in life (Michaelson et al. 2016b), which, together with its dimensions, is significantly and consistently associated with individuals’ perception of their health status (Michaelson et al. 2016a).

According to the World Health Organization, mental health is a mode of well-being in which individuals can realize their capabilities and adapt to the stressful situations of daily life and effectively and usefully work and participate in social activities (Noorbala et al. 2004). In contrast to mental health, which is associated with personal dimensions of evaluating people’s performance, social health is mainly associated with the general and social dimensions by which one can assess an individual’s performance in life. According to the World Health Organization definition, social health is a major dimension of health (Abachizadeh et al. 2013; Hashemi et al. 2016) which is defined into two components: (1) the ability to actively and effectively be involved in one’s environment and social situations and (2) the ability to fulfill one’s role in the community without harming others. This active participation in the community refers to activities such as having a job or educating in society, and participating in charity associations and group activities such as marches and elections. High levels of social health are characterized by factors including life expectancy, having a private house, access to social support, stability in the family, and a low incidence of negative human events and tragedies such as suicide and accidents (Nikoogoftar 2014).

In recent years, many studies have suggested significant relationships between spiritual health and mental health, especially in student samples (Jafari et al. 2010; Katerndahl et al. 2015; Khadem et al. 2016; Koenig et al. 2007; Momeni et al. 2013; Picciotto and Fox 2018; Vafaee 2015). In fact, stress, anxiety, and depression decrease in both female and male students with an increase in spiritual health (Khadem et al. 2016). Furthermore, spiritual dimensions affect the physical dimensions of health (Chiu et al. 2004) because individuals with spiritual health enjoy higher levels of physical health compared to those who lack spiritual health (King et al. 2013).

Scientists have studied the association between social relationships and health for many years. The more individuals are secluded and the less they are involved in social interactions, the less they enjoy physical and mental health (House et al. 1988). In addition, social support is often associated with positive health outcomes (Fiori and Denckla 2012; Kamimura et al. 2013). Larson believes that factors such as social criteria influence the quality of life and people’s performance and mental health and that achieving high performance in life does not necessarily mean having psychological and emotional health or fulfilling social obligations. Social health refers to the quality of the relationships established with others, the type of reaction the individuals have to these relationships, and their performance in relation to social organizations (Nikoogoftar 2014).

A review of the literature performed on the study variables and their relationships showed that the questionnaires used for measuring spiritual and social health in the Iranian population have been developed by researchers from cultures different from Iran’s and have been used for many years in various studies. Using native questionnaires to measure these variables was therefore a necessity in the present research. These three dimensions of health (spiritual, social, and general) were also found to be rarely addressed in the literature. The present study therefore used a scientific method to investigate the potential role of spiritual health in predicting general and social health and to determine whether general and social health could be improved by promoting spiritual health in university students, which is a key class in society.

Method

The present cross-sectional descriptive and analytical research was approved by the research council of the Student Research Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences (contract no. 96–01–193–30,564). The study population comprised all 8844 students at Iran University of Medical Sciences in the 2017–18 academic year. Stratified random sampling was used to select 233 students of the study population based on the sample size determination formula for finite populations (Haghdoost et al. 2011). The students were classified by gender, and simple random sampling was used to select a number of them in each category based on the population of that category. Three questionnaires were distributed among the selected students, namely, a spiritual health questionnaire (Amiri et al. 2015), a social health questionnaire (Abachizadeh et al. 2014), and the General Health Questionnaire (Goldberg and Hillier 1979). Seventeen questionnaires were incomplete and thus were eliminated from the study. The principles of consent and anonymity were respected.

Measures

Spiritual health questionnaire

Amiri et al. (2015) developed the spiritual health questionnaire. In this study, 93 initial items were extracted on the three dimensions of intuition, attitude, and behavior from reliable Islamic resources approved by the Department of Spiritual Health in the Academy of Medical Sciences of Iran. Experts found that 48 items in the results of this study are essential. Experts approved the content validity of this test. The results of the exploratory factor analysis suggested a nine-factor model in the structure of the developed items, and the optimal model was finally proposed based on the cognitive/emotional component and the behavioral component. Confirmatory factor analysis also confirmed the fit of the extracted model, and Cronbach’s alpha was reported as 0.87. The results obtained from the test-retest of all the constructs and subconstructs confirmed the questionnaire’s reliability. This questionnaire contains two sections. The first section is comprised of 28 items that are rated on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (completely agree) to 5 (completely disagree). The second section is comprised of 20 items that are scored on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (always) to 5 (never) (Amiri et al. 2015).

Social health questionnaire

The social health scale was developed in a study conducted by Abachizadeh et al. under the supervision of the Social Health Department of the Ministry of Health and Medical Education of Iran in 2013. This questionnaire contains 33 items that are scored on a 6-point Likert scale (very much, much, moderate, low, very low, and no comment). The internal consistency of the items was confirmed by calculating a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.86, and the reliability coefficient of the samples was 0.91. Factor analysis identified three factors in this scale: family, society, and friends and relatives. Internal consistency was confirmed by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91 for society, 0.77 for friends and relatives, and 0.78 for family. The internal correlation coefficient was also calculated as 0.69 for society, 0.80 for friends and relatives, and 0.67 for family (Abachizadeh et al. 2014).

General Health Questionnaire

The General Health Questionnaire is one of the most well-known screening questionnaires in the field of psychology and psychiatry. The present study used the 28-item form. This questionnaire measures four scales, which are somatic symptoms, anxiety and insomnia, social dysfunction, and depression. Each scale is comprised of seven items that are scored on a 4-point Likert scale: never, as usual, more than usual, and very much more than usual. The reliability of this questionnaire was calculated as 84–91% in different studies in Iran, which is acceptable. Palahang et al. (1996) also reported a validity coefficient of 91% for this questionnaire and Yaghubi et al. (1995) 88%. Moreover, a Cronbach’s alpha of 84% was calculated for somatic symptoms, 85% for anxiety, 79% for social functioning, 81% for depression, and 90% for the general health status, suggesting an acceptable internal consistency for this questionnaire (Hosseini et al. 2011).

Data analysis

The data obtained were analyzed in SPSS-21 using statistical tests such as the Pearson correlation and stepwise multiple regression after examining the hypotheses for performing these tests.

Results

The study participants consisted of 233 students, 99 men and 134 women, with a mean age of 24 ± 3.7.

According to Table 1 and the results of the Pearson correlation, significantly positive relationships were observed between spiritual health and general health, with a confidence interval of 95% (P < 0.05). Significantly positive relationships were observed between spiritual health and social health, with a 99% confidence interval (P < 0.01). Significantly positive relationships were also observed between general health and social health, with a confidence interval of 99% (P < 0.01).

To investigate whether spiritual health is a predictor of general health and social health, first the regression hypotheses were examined and then a stepwise multiple regression was performed.

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test used for examining the data normality resulted in 0.98 for spiritual health (P = 0.28), 1.38 for general health (P = 0.44), and 1.02 for social health (P = 0.24). The statistic of all the variables is therefore insignificant, which confirms the hypothesis of the normality of the variables.

The multiple correlation coefficient between the independent variable (spiritual health) and the dependent variable (general health) was found to be 0.13. The value of the determination coefficient (R squared) was also equal to 0.01, which shows the degree of variance and variations in general health that is explained by spiritual health. The Durbin–Watson statistic was used to investigate the independence of residuals. According to the results, this statistic equals 2.04, which confirms the hypothesis of the independence of residuals given that its value lies between 1.5 and 2.5. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to investigate the proposed regression model and found an F value of 4.17, which is significant at a significance level of 0.05 and suggests the appropriateness of the regression model.

According to Table 2, only spiritual health can predict general health. Given that the tolerance statistic is above the cutoff of 0.1 and that the variance inflation factor (VIF) is less than the cutoff of 10, the collinearity assumption is satisfied. The value of the standardized regression coefficient (Beta) for spiritual health is equal to 0.13 in the final model. Given that the t statistics obtained are significant at an alpha level of 0.05, the results indicate that spiritual health significantly predicts general health, although this prediction is about 1% because the determination coefficient is only 1%.

The multiple correlation coefficient between spiritual health (independent variable) and social health (dependent variable) is 0.21. The determination coefficient (R squared) is 0.04, which shows the degree of variance and variations in social health that is explained by spiritual health. The Durbin-Watson statistic was used to investigate the independence of residuals. According to the results, this statistic equals 1.93, which confirms the hypothesis of the independence of residuals since its value lies between 1.5 and 2.5. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to investigate the proposed regression model and found an F value of 9.70, which is significant at a significance level of 0.01 and suggests the appropriateness of the regression model.

According to Table 3, only spiritual health can predict social health. Given that the tolerance statistic is above the cutoff of 0.1 and the VIF is less than the cutoff of 10, the collinearity assumption is satisfied. The value of the standardized regression coefficient (Beta) for spiritual health is equal to 0.20 in the final model. Given that the t statistics obtained are significant at an alpha level of 0.01, spiritual health is concluded to significantly predict social health, although this prediction is about 4% because the determination coefficient is only 4%.

Discussion

The present study explored the potential role of spiritual health in predicting general health and social health in students of Iran University of Medical Sciences, and it suggested significantly positive relationships between spiritual health and general health, which is consistent with the findings obtained by Moradi-Joo et al. (2017), Seraji et al. (2016), and Semyari et al. (2015). This finding suggests that general health increases or decreases with an increase or decrease in spiritual health, respectively; in other words, spiritual behavior positively affects general health. A study conducted by Mahbobi et al. (2012) on the relationship between spiritual health and social anxiety in veterans with chemical war injuries found negative relationships between spiritual health and social anxiety in the veterans, meaning that veterans with high levels of spiritual health experience low levels of social anxiety and high levels of general health and vice versa. In contrast, a study conducted by Varee et al. (2017) entitled “Comparing Spiritual Well-being, Happiness, and General Health among University and Seminary Students” showed that the relationship of general health with spiritual well-being, existential well-being, and religious well-being is significant and negative.

The studies cited found positive and significant relationships between spiritual health and general health in patients with physical or Psychological disorders, in contrast to the findings in healthy populations such as students. The present study used a new spiritual health questionnaire developed by Iranian researchers instead of older ones developed by non-Iranians to investigate this relationship in students at Iran University of Medical Sciences.

The present study also investigated the power of spiritual health to predict general health. According to the results of the present research and those obtained by Allahbakhshian et al. (2010), Baljani et al. (2011), Zafarian et al. (2016), Ghahremani and Nadi (2012), and Hatamipour et al. (2016), spiritual health significantly predicts general health. The prediction power of spiritual health obtained in the present study is, however, unfavorable, about 1%. This low level of prediction compared to previous studies can be associated with the difference between the spiritual health questionnaire used in the present study and that used in the cited studies. The Spiritual Well-Being Scale (SWBS) developed by Ellison and Paloutzian (Ellison 1983) in 1982 is a 20-item instrument with two subscales, with even items evaluating existential health and odd items assessing religious health. This scale has been used in the majority of the studies measuring spiritual health. An advantage of the present research is the use of the spiritual health questionnaire developed by the Academy of Medical Sciences of Iran (Amiri et al. 2015). This questionnaire addresses the three constructs of intuition, attitude, and spiritual behavior and investigates dimensions such as connection with God, with the self, and with nature (Abachizadeh et al. 2014). The items of this questionnaire well reflect the religious/spiritual beliefs and the cultural texture of Iranian society (Fisher et al. 2002).

Shahbazirad et al. (2015) conducted a study on the role of spiritual health in predicting quality of life and found significantly positive relationships between spiritual health and quality of life in students and concluded that spiritual health was a predictor of the students’ quality of life. The contribution of the present article is to consider quality of life as an outcome of three variables in the sample group, namely, mental health, physical health, and social health, which confirms the overall results.

The present study found significantly positive relationships between spiritual health and social health, which is consistent with those obtained by Mohammadi et al. (2017) and Chavoshian et al. (2015), who examined and confirmed this relationship. The study conducted by Chavoshian on the role of spiritual health and social support in predicting quality of life suggested that the correlation of spiritual health with the physical, mental, environmental, and social dimensions of quality of life is positive and significant in nurses. This finding can be explained by the fact that subjects who receive high scores on the dimension of relationships with the environment (others and nature) in the spiritual health questionnaire, which comprise three dimensions of intuition, attitude, and behavior, feel responsible towards others, highly value humanity, help others, and respect the rights of others. These individuals therefore received high social health scores.

The present study suggests the ability of spiritual health to predict social health, even though its Beta was little, which is consistent with the findings of Zeighami Mohammadi and Tajvidi (2011), who showed that adolescents with thalassemia and high levels of spiritual health enjoyed high levels of social skills. Prince-Paul (2008) also found significant and positive relationships between social health and spiritual health. That study was conducted on cancer patients and showed that social functioning in the patients is associated with and can be predicted by their spiritual health.

Bodaghi et al. (2017) found that the relationship of anxiety, depression, and stress with social support and spirituality is negative. They also showed that predictor variables, including family support, spirituality, and support from friends, predict 55% of the variance of anxiety and that predictor variables, including family support and spirituality, predict 44% of the variance of depression, whereas family support predicts 18% of the variance of stress in pregnant women. Given these findings, spiritual health appears to be able to predict social health, whereas it has negative correlations with social health-associated disorders and cannot predict them. The present study also found that spiritual health predicted social health, although the prediction power was low. A review of the literature associated with social health showed that the majority of these studies are focused on patients and clinical populations rather than healthy populations, especially students.

A limitation of previously conducted studies, especially in Iran, is the use of non-native questionnaires such as the 20-item Keez social health questionnaire that assesses social health on five dimensions (Huber et al. 2011). There has recently been more attention paid to the social dimension of health. This variable is affected by the situation and by conditions dominating the society such as economic status and cultural conditions (Hosseini et al. 2011). This denotes the necessity of using native questionnaires for a specific population. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no studies have yet been conducted on the evaluation of this variable in the Iranian population using a native scale. Given that two of the questionnaires used in the present study are newly developed native questionnaires, similar studies are recommended to be carried out using these questionnaires to more accurately investigate the results in groups of students from other universities and cities in Iran. In addition, one of the limitations of this study is its reliance on self-reporting; the information was obtained from questionnaires provided to the students. Since responses are often overestimated or underestimated in self-report studies, to remove this effect and further examine the results, other types of studies such as case-control studies should be conducted.

Conclusion

The dimensions of health are interwoven. Addressing these dimensions, especially the spiritual dimension, and their interactions is a new subject that is well researched in many communities. Investigating the role of this variable in young people, especially students, is an important subject that is addressed in the present article. Also, another consideration of this research was the measurement of spiritual and social health of Iranian people by questionnaires which were appropriate to the Iranian context. Given the present findings, spiritual health appears to be associated with general health, mental health, and social health. This relationship also allows for the relative prediction of other dimensions of health in students based on spiritual health. Promoting the spiritual dimension of health is associated with improvement in physical illnesses and psychological problems and disorders. Moreover, increasing spiritual well-being can promote individuals’ social functioning in relation to family, friends, relatives, and the surrounding community.

References

Abachizadeh, K., Omidnia, S., Memaryan, N., Nasehi, A., Rasouli, M., Tayefi, B., & Nikfarjam, A. (2013). Determining dimensions of Iranians’ individual social health: A qualitative approach. Iranian Journal of Public Health, 42(Supple1), 88–92.

Abachizadeh, K., Tayefi, B., Nasehi, A. A., Memaryan, N., Rassouli, M., Omidnia, S., & Bagherzadeh, L. (2014). Development of a scale for measuring social health of Iranians living in three big cities. Medical Journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 28, 2.

Allahbakhshian, M., Jaffarpour, M., Parvizy, S., & Haghani, H. (2010). A survey on relationship between spiritual wellbeing and quality of life in multiple sclerosis patients. Zahedan Journal of Research in Medical Sciences, 12(3), 29–33.

Amiri, P., Abbasi, M., Gharibzadeh, S., Zarghani, N. H., & Azizi, F. (2015). Designation and psychometric assessment of a comprehensive spiritual health questionnaire for Iranian populations. Medical Ethics Journal, 9(30), 25–56.

Baljani, E., Khashabi, J., Amanpour, E., & Azimi, N. (2011). Relationship between spiritual well-being, religion, and hope among patients with cancer. Journal of Hayat, 17(3), 27–37.

Bodaghi, E., Alipour, F., Bodaghi, M., Nori, R., Peiman, N., & Saeidpour, S. (2017). The role of spirituality and social support in pregnant women’s anxiety, depression and stress symptoms. Community Health Journal, 10(2), 72–82.

Chavoshian, S. A., Moeini, B., Bashirian, S., & Feradmal, J. (2015). The role of spiritual health and social support in predicting nurses’ quality of life. Journal of Education and Community Health, 2(1), 19–28.

Chiu, L., Emblen, J. D., Van Hofwegen, L., Sawatzky, R., & Meyerhoff, H. (2004). An integrative review of the concept of spirituality in the health sciences. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 26(4), 405–428.

Ellison, C. W. (1983). Spiritual well-being: Conceptualization and measurement. Journal of psychology and theology, 11(4), 330–338.

Fiori, K. L., & Denckla, C. A. (2012). Social support and mental health in middle-aged men and women: A multidimensional approach. Journal of Aging and Health, 24(3), 407–438.

Fisher, J. W., Francis, L. J., & Johnson, P. (2002). The personal and social correlates of spiritual well-being among primary school teachers. Pastoral Psychology, 51(1), 3–11.

Ghahremani, N., & Nadi, M. (2012). Relationship between religious/spiritual components, mental health and hope for the future in hospital staff of shiraz public hospitals. Iran Journal of Nursing, 25(79), 1–11.

Goldberg, D. P., & Hillier, V. F. (1979). A scaled version of the general health questionnaire. Psychological Medicine, 9(1), 139–145.

Haghdoost, A., Baneshi, M., & Marzban, M. (2011). How to estimate the sample size in special conditions? (part two). Iranian Journal of Epidemiology, 7(2), 67–74.

Hashemi, F. M., Pourmalek, F., Tehrani, A., Abachizadeh, K., Memaryan, N., Hazar, N., … Lakeh, M. M. (2016). Monitoring social well-being in Iran. Social Indicators Research, 129(1), 1–12.

Hatamipour, K., Rahimaghaee, F., & Delfan, V. (2016). The relationship between spiritual health and anxiety in nursing student in training at the time of entry into the school. Iranian Journal of Nursing Research, 11(2), 68–77.

Hosseini, H., Sadeghi, A., Rajabzadeh, R., Reza, Z. J., Nabavi, S., Ranaei, M., & ALmasi, A. (2011). Mental health and related factor in students of North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences. Journal of North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences, 3(28), 23–28.

House, J. S., Landis, K. R., & Umberson, D. (1988). Social relationships and health. Science, 241(4865), 540–545.

Huber, M., Knottnerus, J. A., Green, L., van der Horst, H., Jadad, A. R., Kromhout, D., … van der Meer, J. W. (2011). How should we define health? BMJ: British Medical Journal (Online) , 343, d4163.

Jafari, E., Dehshiri, G. R., Eskandari, H., Najafi, M., Heshmati, R., & Hoseinifar, J. (2010). Spiritual well-being and mental health in university students. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 5, 1477–1481.

Kamimura, A., Christensen, N., Tabler, J., Ashby, J., & Olson, L. M. (2013). Patients utilizing a free clinic: Physical and mental health, health literacy, and social support. Journal of Community Health, 38(4), 716–723.

Katerndahl, D., Burge, S., Ferrer, R., Becho, J., & Wood, R. (2015). Effects of religious and spiritual variables on outcomes in violent relationships. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 49(4), 249–263.

Khadem, H., Mozafari, M., Yousefi, A., & Hashemabad, B. G. (2016). The relationship between spiritual health and mental health in students of Ferdowsi University of Mashhad. History of Medicine Journal (Quarterly), 7(25), 33–50.

King, M., Marston, L., McManus, S., Brugha, T., Meltzer, H., & Bebbington, P. (2013). Religion, spirituality and mental health: Results from a national study of English households. British Journal of Psychiatry, 202(1), 68–73.

Koenig, L. B., McGue, M., Krueger, R. F., & Bouchard, T. J. (2007). Religiousness, antisocial behavior, and altruism: Genetic and environmental mediation. Journal of Personality, 75(2), 265–290.

Mahbobi, M., Etemadi, M., Khorasani, E., & Ghiasi, M. (2012). The relationship between spiritual health and social anxiety in chemical veterans. Journal of Military Medicine, 14(3), 186–191.

Memaryan, N., Rassouli, M., & Mehrabi, M. (2016). Spirituality concept by health professionals in Iran: A qualitative study. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine.

Michaelson, V., Brooks, F., Jirásek, I., Inchley, J., Whitehead, R., King, N., … Pickett, W. (2016a). Developmental patterns of adolescent spiritual health in six countries. SSM-Population Health, 2, 294–303.

Michaelson, V., Freeman, J., King, N., Ascough, H., Davison, C., Trothen, T., … Pickett, W. (2016b). Inequalities in the spiritual health of young Canadians: A national, cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 1200.

Mohammadi, M., Alavi, M., Bahrami, M., & Zandieh, Z. (2017). Assessment of the relationship between spiritual and social health and the self-care ability of elderly people referred to community health centers. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research, 22(6), 471–475.

Momeni, K., Karami, J., & Rad, A. S. (2013). The relationship between spirituality, resiliency and coping strategies with students’ psychological well-being in Razi University of Kermanshah. Journal of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, 16(8), 626–634.

Moradi-Joo, M., Babazadeh, T., Honarvar, Z., Mohabat-Bahar, S., Rahmati-Najarkolaei, F., & Haghighi, M. (2017). The relationship between spiritual health and public health aspects among patients with breast cancer. Journal of Research on Religion & Health, 3(3), 80–91.

Nikoogoftar, M. (2014). Interdisciplinary approach to social health: The predictive role of the individualism-collectivism. Interdisciplinary Studies in the Humanities (Iranian Journal of Cultural Research), 6(2), 57–70.

Noorbala, A., Yazdi, S. B., Yasamy, M., & Mohammad, K. (2004). Mental health survey of the adult population in Iran. British Journal of Psychiatry, 184(1), 70–73.

Palahang, H., Nasr, M., Brahani, M. N., & Shahmohammadi, D. (1996). Epidemiology of mental illnesses in Kashan City. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 2(4), 19–27.

Picciotto, G., & Fox, J. (2018). Exploring experts’ perspectives on spiritual bypass: A conventional content analysis. Pastoral Psychology, 67(1), 1–20.

Prince-Paul, M. (2008). Relationships among communicative acts, social well-being, and spiritual well-being on the quality of life at the end of life in patients with cancer enrolled in hospice. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 11(1), 20–25.

Sadat Hoseini, A. S., Panah, A. K., & Alhani, F. (2015). The concept analysis of health based on Islamic sources: Intellectual health. International Journal of Nursing Knowledge, 26(3), 113–120.

Semyari, H., Nasiri, M., & Arabi, F. (2015). The relationship of dentistry students’ spiritual intelligence to general health. Iranian Journal of Psychiatric Nursing, 3(1), 47–58.

Seraji, M., Shojaezade, D., & Rakhshani, F. (2016). The relationship between spiritual well-being and quality of life among the elderly people residing in Zahedan City (south-east of Iran). Elderly Health Journal, 2(2), 84–88.

Shahbazirad, A., Momeni, K., & Mirderikvand, F. (2015). The role of spiritual health in prediction of the quality of life of students in Razi University of Kermanshah during academic year of 2014–2015. Islam and Health Journal, 2(1), 40–50.

Vafaee, R. (2015). Association of between mental health and spiritual health among students in Shiraz University. Advances in Nursing & Midwifery, 24(84), 53–59.

Varee, H., Askarizadeh, G., & Bagheri, M. (2017). Comparing spiritual well-being, happiness, and general health among university and seminary students. Journal of Research on Religion & Health, 3(3), 55–67.

Yaghubi, N., Nasr, M., & Shahmohammadi, D. (1995). Epidemiology of mental disorders in Urabn and rural areas of Sowmaesara-Gillan. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 1(4), 55–60.

Zafarian, M. E., Behnam, V. H., Reyhani, T., & Namazi, Z. S. (2016). The effect of spiritual education on depression, anxiety and stress of caregivers of children with leukemia. Journal of Torbat Heydariyeh University of Medical Sciences, 4(1), 1–7.

Zeighami Mohammadi, S., & Tajvidi, M. (2011). Relationship between spiritual well-being with hopelessness and social skills in beta-thalassemia major adolescents (2010). Modern Care Journal, 8(3), 116–124.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank all the participants in this research and the members of Spiritual Health Research Center of Iran University of Medical Sciences for their valuable contributions. We also appreciate the Student Research Committee at Iran University of Medical Sciences for funding this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

We have no conflict of interest to declare in our manuscript.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Ethical standards

In addition, all procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Farshadnia, E., Koochakzaei, M., Borji, M. et al. Spiritual Health as a Predictor of Social and General Health in University Students? A Study in Iran. Pastoral Psychol 67, 493–504 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-018-0828-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-018-0828-y