Abstract

This study aimed to determine the status of quality of life, spiritual well-being, and their relationship among Iranian adolescent girls. This cross-sectional study was conducted on 520 students using the cluster sampling method. The mean score of quality of life was 59.86 (SD: 12.7) from the possible range of 0–100. The mean score of spiritual well-being was 90.22 (SD: 16.25), ranging from 20 to 120. Multivariate linear regression analysis showed a significant relationship between quality of life and the factors including existential well-being, religious well-being, parents’ belief for their children’s participation in religious ceremonies, father’s education and occupation, father’s illness, sufficiency of family income for expenses, and the number of children. Given that spiritual well-being dimensions are among the predictors of quality of life. Thus, it is necessary to find ways to promote spiritual well-being in adolescents and ultimately improve their quality of life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adolescents, whose health plays an important role in society’s health, are among one of the most important age groups in each society (Mirghafourvand et al. 2014). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), adolescence is defined as a stage of human growth and development which is between childhood and adulthood (10–19 years of age) (WHO 2002). Population of adolescents in Iran was estimated as 12 million (about 16 % of the population) according to the Iranian population and housing census (Statistical Center of Iran 2011).

Quality of life is a health indicator (Mirghafourvand et al. 2015). Adolescence is a critical physical and mental stage, a series of significant changes occur during this period that may affect health-related quality of life (Williams et al. 2002). Quality of life during adolescence can affect adults’ health and quality of life (WHO 2014). According to the WHO, quality of life is defined as individuals’ perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live. It is a broad ranging concept affected in a complex way by the people’s physical health, psychological state, level of independence, social relationships, personal beliefs, and their relationship to salient features of their environment (WHO 1997). Since health is a multidimensional concept, health-related quality of life is a multidimensional concept, too. It involves various domains such as physiological, physical, psychological, and social functioning (Anye et al. 2013). Most attention has been given to health-related quality of life among individuals, and very few studies have been conducted among adolescents (Zullig et al. 2006).

The WHO has currently addressed the need for spiritual well-being as the fourth dimension of health, introducing it as an important element (Dhar et al. 2011). Spiritual well-being is determined through features such as stability, peace, balance and harmony, and a close relationship with self, God, and society. It can also coordinate physical, mental, and social dimensions (Cotton et al. 2006a, b). Today, spirituality has turned out to be a favorite topic in health care (Arcury et al. 2000). When individuals’ spiritual well-being is seriously compromised, they may suffer from mental disorders such as feeling of loneliness, depression, and loss of meaning in life (Yonker et al. 2012). Although not everyone cares about spirituality, it is believed to be able to increase life satisfaction and quality of life (Frsch 2006; Krageloh et al. 2015; Sawatzky et al. 2009).

Spirituality may affect health and wellbeing in adolescents (Konopack and McAuley 2012). The results of studies suggest that spirituality in adolescents is associated with health risk behaviors (Luquis and Brelsford 2012; Rew and Wong 2006), physical health (Dyer 2007), depression and psychological adjustment (Cotton et al. 2006a, b; Hodges 2002), and anxiety (Dew et al. 2008). A study in Canada showed that spirituality can affect the overall quality of life, satisfaction with family, friends, living environment, and school (Sawatzky et al. 2009). Moreover, a study by Miller and Gur (2002) showed that spirituality has a greater effect on quality of life and life satisfaction among adolescents than among adults. The wider range of beliefs, spiritual well-being, and a sense of meaning and purpose in life are probably the predictors of quality of life among adolescents and adults (Sawatzky et al. 2009).

Very few studies have been conducted on the relationship between spirituality and quality of life among adolescents (Kattan and Talwar 2013). Understanding the quality of life and it dimensions as well as the effect of spiritual well-being as an important variable on the quality of life are appropriate strategies that can be employed to improve adolescent health. Therefore, since the health of adolescents and improving their quality of life are important, and given the possible role of spirituality in quality of life and lack of studies on the relationship between spiritual well-being and quality of life among adolescents in Iran (according to the search conducted by the researcher), this study aimed to determine the relationship between spiritual well-being and health-related quality of life among adolescent girls.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted on 520 adolescents 15–18 years old studying in the first to fourth grades at public and private high schools in Tabriz, Iran. Inclusion criteria included being Iranian, age of 15–18, resident of Tabriz, willingness to participate in the study, and having physical health. Exclusion criteria included history of depression or current depression in the adolescents.

The sample size was calculated based on both parameters (health-related quality of life and spiritual well-being), a sample size of 260 was calculated based on the maximum standard deviation of health-related quality of life sub-domains (financial resources) and considering a 5 % error, 0.05 accuracy around the mean (m = 72.38) and SD = 20.93. Also, it was calculated again as 68 individuals based on spiritual well-being by considering error = 5 %, β = 0.1, precision = 0.05 around the mean (m = 93.01) and SD = 13.78. Since the sample size estimated based on the quality of life parameter was higher, it was considered 260 individuals. Since cluster sampling was carried out, final sample size was calculated as 520 taking into account a design effect of 2.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (Ethics Number: 5/41/10632).

Data Collection

The cluster sampling method was used in this study. The complete list of 110 all-girl schools in the urban areas in five districts of Tabriz was obtained from the Tabriz Department of Education. A total of 27 schools (approximately one-fourth of all the schools) were selected using the proportionally random sampling method. The list of students studying in the selected schools was obtained, and 520 students were selected through proportionally random sampling. The study aims were explained to the students, and written consents were completed by students. The parents’ consents were also obtained via telephone. Finally, the self-administered questioners were completed by the students.

Measures

The questionnaires used in this study included the questionnaires of socio-demographic characteristics, health-related quality of life, and spiritual well-being scale (SWBS).

The socio-demographic characteristics questionnaire included items on age, field of education, father’s and mother’s education, father’s and mother’s occupation, father’s and mother’s illness, number of children, sufficiency of family income for expenses, type of residence, parents’ belief for their children’s participation in religious ceremonies and places, and parents belonging to a religious family.

Health-related Quality of Life Questionnaire in Adolescents (KIDSCREEN questionnaire) was developed based on the European project “screening and promotion of health-related quality of life in children and adolescents” which includes 22,296 children from 13 European countries. This self-report tool is applicable for 8–18-years-old healthy adolescents and children and those with chronic diseases. The 27-item version of the questionnaire includes five dimensions including: 1. Physical well-being (5 questions) that measures physical activity levels and energy. 2. Psychological well-being (7 questions) that measures positive emotions, life satisfaction, and feelings that are emotionally balanced. 3. Communication with parents and autonomy (7 questions) that examines communication with parents, home atmosphere, having enough autonomy associated with age and the degree of satisfaction of financial resources. 4. Social support and peers (4 questions) that examines the nature of responder’s communications with peers. 5. School environment (4 questions) that examines the children and adolescents’ perception of cognitive capacity, learning, concentration and feelings about school. The scores are then linearly converted to a 0–100 range, where the score of 100 and 0 indicate the highest and lowest quality of life, respectively (Ravens-Sieberer et al. 2007). Reliability and validity of the tool were studied and confirmed through a research on 551 Iranian students. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for all dimensions, except for school environment dimension, were above 0.70 and test–retest reliability coefficients for all dimensions were strong. Construct validity has been confirmed by exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and RMSEA and CFI indices was equal to 0.053 and 0.97 that demonstrated appropriate fit. So KIDSCREEN questionnaire has an appropriate validity and reliability in Iranian population (Nik-azin et al. 2012).

The Spiritual Well-Being Scale (SWBS) that was developed by Paloutzian and Ellison in 1982 includes 20 questions of which ten questions assess religious well-being and ten questions assess existential well-being. The sum of the scores of the two subscales constitutes the spiritual well-being score, which ranges from 20 to 120. The answers are classified based on the 6-point Likert scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree. Finally, individuals’ spiritual well-being is classified into three categories, including low (20–40), medium (41–99), and high (100–120). Vahedi et al. (2011) in a study on 292 undergraduate students in Tabriz-Iran evaluated the validity and reliability of the Spiritual Well-Being Scale, and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was obtained 0.81 for both existential and religious well-being. In addition to mentioned study, the content validity and reliability of the Persian version of questionnaire had been examined in various studies (Abbasi et al. 2006; Mahboobi et al. 2012; Hojjati et al. 2009, 2010). Also, the construct validity of this scale has been confirmed in a study by Musa (2014) on Jordanian Arab and Malaysian Muslim University Students in Jordan.

Content and face validity were used to determine the validity of the socio-demographic questionnaire. This questionnaire was provided to ten faculty members. The questionnaire was then modified based on the received feedbacks. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha values for health-related quality of life questionnaire and the spiritual well-Being questionnaire were calculated as 0.87 and 0.90, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS 18 was used for data analysis. Descriptive statistics including frequency and percentage as well as central tendency and dispersion such as mean and standard deviation were used to describe the socio-demographic characteristics, and the status of spiritual well-being and quality of life. Bivariate statistical tests such as independent t, Pearson and one way ANOVA tests were used to analyze the relationship between health-related quality of life, spiritual wellbeing and socio-demographic characteristics. To control for confounding variables and to estimate the effect of each independent variables (spiritual well-being and socio-demographic characteristics) on the dependent variable (health-related quality of life), those independent variables with p value <0.2 in the bivariate analysis were entered in the multivariate linear regression model through the backward strategy. Before multivariate analysis, the regression assumptions such as normality of residuals, collinearity, outliers, and independence of residuals were examined.

The mean (SD = Standard Deviation) age of the students was [16.3 (0.8)] years. Forty-three percent of the students were 16 years old, and 39 % were in the second grade of high school. The majority (81 %) of the students were studying in public schools. Three also worked. The majority (93.3 %) of the students lived with their parents (Table 1).

The mean score (SD) total score of quality of life was [59.9 (12.7)] out of the achievable score range of 0–100. The highest score [74.3 (14.5)] was observed in the sub-domain of communication with parents and autonomy, whereas the lowest score [63.9 (13.2)] was observed in the psychological sub-domain. The mean score (SD) of spiritual well-being was [90.2 (16.2)], ranging from 20 to 120. The highest mean among adolescents belonged to existential well-being [49.5 (7.9)] and the lowest mean belonged to religious well-being (40.6) (Table 2).

In this study, there was a significant positive correlation between health-related quality of life among adolescent girls and total spiritual well-being score and its dimensions based on the Pearson’s correlation coefficient (p < 0.005). Only no significant relationship was observed between religious well-being and the sub-domain of social support and peers (p > 0.05) (Table 3).

The results of the bivariate tests such as one-way ANOVA and independent t test revealed a significant relationship between health-related quality of life and parent’s education, type of residence, and type of school, sufficiency of family income for expenses, father’s illness, father’s occupation and number of children in the family (p < 0.05). No significant relationship was observed between health-related quality of life and level of education, academic disciplines, working along with studying, mothers’ occupation, mothers’ illness, parents’ belief for their children’s participation in religious ceremonies, belonging of parents to a religious family (p > 0.05). Multivariate linear regression showed that the variables of existential well-being, religious well-being, parents’ belief for their children’s participation in religious ceremonies, father’s education and occupation, father’s illness, sufficiency of family income for expenses, and the number of children were predictors of health-related quality of life in adolescents (Table 4).

Discussion

The results of data analysis showed that health-related quality of life among adolescent girls was a little more than moderate. Moreover, the mean score of spiritual well-being among adolescent girls was relatively high. Health-related quality of life among adolescent girls had a statistically significant relationship with total spiritual well-being score and its two dimensions (existential and religious well-being).

In this study, health-related quality of life score in the female adolescents were higher than average of the highest potential score of the questionnaire; therefore, our results were consistent with those reported by Nik-Azin et al. (2013) conducted on 551 male and female students where 275 of them were female. Our results were also consistent with those obtained by Mazloomy et al. (2011) in a study on the relationship between chronic stress and quality of life of high school female students in Yazd—Iran. Kvarme et al. (2009) reported a higher-than-average score for quality of life in adolescents. In that study, the highest score was obtained in the psychological aspect, while the lowest score was obtained in the school aspect. In our study, however, the highest score was observed in the dimension of communication with parents and autonomy, and the lowest score was observed in the psychological dimension. The high score of communication with parents may be attributed to the culture of the Iranian community regarding the strong connection with children and the preference of parents to have a single child or less children which results in more opportunities to communicate with children. The low score in the psychological dimension can be due to physical changes that begin or occur in girls such as menstruation and hormonal imbalance. These changes in girls’ nervous and hormonal system are the foundation of changes in adolescents’ emotional well-being. Huebner et al. (2000) reported similar results.

Since Iranian society is a religious society inclined toward spiritual values, obtaining a relatively higher score for spiritual well-being was expected. This result is consistent with the results of the studies by Safaee-Rad et al. (2011), Allahbakhshian et al. (2012) and Rubin et al. (2009), in which the spiritual well-being score was medium. In the present study, adolescent girls obtained the highest and lowest scores in existential well-being and religious well-being respectively, which is consistent with the results of a study by Rahimi et al. (2013) on nursing and midwifery students. However, unlike the results of the studies by Rubin and Safaee Rad in which the highest score belonged to religious well-being, the highest score in the present study belonged to existential well-being.

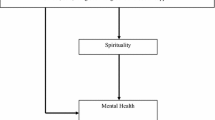

This study showed that there is a statistically strong positive relationship between spiritual well-being and health-related quality of life. The results are similar to the reported results of a meta-analysis by Sawatzky et al. (2005), which was carried out by reviewing 51 articles and revealed several findings that support the conceptualization of spirituality as a distinct concept that relates to quality of life. Moreover, in another study by the same researcher, structural equation modeling was used to test the relationship between spirituality and quality of life and results showed that the spirituality was significantly correlated with QOL. This association was predominantly mediated by adolescents’ satisfaction with their family, their perceived self, and their perceived mental health status (Sawatzky et al. 2009). In his study, Konopack and McAuley (2012) concluded that spirituality, like physical activity, probably can have a positive effect on mental health and consequently affect and improve individuals’ quality of life. The findings of a study by O’Connell and Skevington (2005) in Britain were also consistent with the findings of the present and previously mentioned studies.

Despite the growing evidence supporting an association between spirituality and QOL in adolescents, the underlying mechanisms by which spirituality may contribute to QOL in adolescents are relatively unknown (Sawatzky et al. 2009; Douglas and Barbara 2013). Psychological and physiologic pathways have been reported. For example, spirituality is likely to affect health through psychological pathway, such as altering cognitive appraisals of events, decreasing a need for control, or enhancing a sense of control or coherence that may decrease stress, and thus improve health outcomes (Yanez et al. 2009). In addition, some have reported a direct physiologic pathway for spirituality including the potential to deactivate the sympathetic nervous system, enhance parasympathetic activation and reduce inflammatory cytokines and circulating cortisol levels, and may thereby contribute to reduced risks for a range of health outcomes (Chida et al. 2009). Findings of a study by Greeson et al. (2011), according to exploratory mediation model have been suggested a novel mechanism by which increased spirituality following Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction accounted for improved mental health-related quality of life both directly and indirectly, as a function of increased mindfulness.

Spirituality promotes optimism, which increase resilience when coping with stressful situations (Pargamen et al. 1998). According to a study, spirituality is one of the health promotion strategies (Baheiraei et al. 2013). Spirituality can act like a shield against problems and discomforts, promote health and life satisfaction, and consequently improve individuals’ quality of life (Baheiraei et al. 2012). The beliefs of spirituality had positive effects on their quality of life by providing of hope and optimism, as well as a sense of awe and appreciation for things in nature and their surroundings (Krageloh et al. 2015).

The degree to which the spirituality items provide reliable and valid measures of spirituality in adolescents is unknown (Sawatzky et al. 2009). One of the item in SWBS, such as “I don’t enjoy much about life”, is probably confounded with a item in QOL scale such as “thinking about last week, has your life been enjoyable?”. Although the Persian version of SWBS has been used in several studies in Iran but further research contributing to the development of reliable and valid measures of adolescent spirituality is recommended in this context.

In this study, greater number of children, father’s unemployment, father’s low level of education, father’s illness, and family’s unfavorable economic situation and lack of parents’ belief for their children’s participation in religious ceremonies decreased health-related quality of life among adolescents. Unlike the present study, in a study by Mohammadian et al. (2013), only the variable of economic situation was reported to be associated with the quality of life. Moreover, a study by Naghibi et al. (2013) showed that there is a statistically significant relationship between father’s occupation and health-related quality of life, which is consistent with the present study. Father’s occupation and education level, father’s illness, and number of children can affect the quality of life of family members by affecting economic situation. This is due to the fact that family’s economic situation is effective in families’, especially children’s access to health care facilities and amenities, and it can improve their quality of life.

A limitation of this study was that since it was a cross-sectional study, the relationship between spiritual well-being, socio-demographic characteristics and health-related quality of life does not necessarily indicate a cause-effect relationship. Thus, conducting of longitudinal research is recommended to explore the contribution of spirituality to QOL enhancement over time. Qualitative and quantitative research on the barriers and facilitators of spiritual well-being in adolescents are recommended in this regard. The results of such studies can help provide effective strategies for promoting of adolescents’ health. Another issue to consider is that the study population had Azeri language and culture. Cross-cultural research on spiritual well-being and its impact on health-related quality of life in adolescents are also recommended in this field.

Conclusion

The results of the present study show a significant relationship between spiritual well-being and health-related quality of life in female adolescents. Future investigation is needed to identify other important variables and mediators in the relationships among spirituality and health-related quality of life in adolescents. Due to the fact that adolescence is one of the most important periods of human evolution, and since adolescents are encountered with many problems including identity crisis in this period, spiritual well-being can act as a powerful facilitator for improving the quality of life in adolescents during passage from this particular period.

References

Abbasi, M., Farahaninia, M., Mehrdad, N., Givari, A., & Haghani, H. (2006). Nursing students’ spiritual well-being and their perspectives towards spirituality and spiritual care perspectives. Iran Journal of Nursing, 18(44), 242–247.

Allahbakhshian, M., Jaffarpour, M., Parvizy, S., & Haghani, H. (2012). A survey on relationship between spiritual wellbeing and quality of life in multiple sclerosis patients. Zahedan Journal of Research in Medical Sciences, 12(3), 29–33.

Anye, E. T., Gallien, T. L., Bian, H., & Moulton, M. (2013). The relationship between spiritual well-being and health-related quality of life in college students. Journal of American College Health, 61(7), 414–421.

Arcury, T. A., Stafford, J. M., Bell, R. A., Golden, S. L., Snively, B. M., & Quandt, S. A. (2000). Attitudes of occupational therapists toward spirituality in practice. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 54, 421–426.

Baheiraei, A., Mirghafourvand, M., Mohammadi, E., & Charandabi, S. M. (2012). The experiences of women of reproductive age regarding health-promotion behaviours: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 12, 573.

Baheiraei, A., Mirghafourvand, M., Mohammodi, E., Mohammad-Alizadeh, C., & Nedjat, S. (2013). Determining appropriate strategies for improving women’s health promoting behaviours: using the nominal group technique. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 19(5), 409–416.

Chida, Y., Steptoe, A., & Powell, L. H. (2009). Religiosity/spirituality and mortality. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 78, 81–90.

Cotton, S., Zebracki, K., Rosenthal, S. L., Tsevat, J., & Drotar, D. (2006a). Religion/spirituality and adolescent health outcomes: A review. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 38(4), 472–480.

Cotton, S., Zebracki, K., Rosenthal, S., Tsevat, J., & Drotar, D. (2006b). Religion/spirituality and adolescent health outcomes: A review. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 38, 472–480.

Dew, R., Daniel, S., & Armstrong, T. (2008). Religion/spirituality and adolescent psychiatric symptoms: A review. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 39, 381–398.

Dhar, N., Chaturvedi, S., & Nandan, D. (2011). Spiritual health scale 2011: Defining and measuring 4 dimension of health. Indian Journal of Community Medicine, 36(4), 275–282.

Douglas, S. L., & Daly, B. J. (2013). The impact of patient quality of life and spirituality upon caregiver depression for those with advanced cancer. Palliative and Supportive Care, 11(5), 389–396.

Dyer, J. (2007). How does spirituality affect physical health? A conceptual review. Holist Nursing Practice, 21(6), 324–328.

Frsch, M. B. (2006). Quality of life therapy: Applying a life: Satisfaction approach to positive psychology and cognitive therapy. Tehran: Arjmand.

Greeson, J. M., Webber, D. M., Smoski, M. J., Brantley, J. G., Ekblad, A. G., Suarez, E. C., et al. (2011). Changes in spirituality partly explain health-related quality of life outcomes after mindfulness-based stress reduction. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 34(6), 508–518.

Hodges, S. (2002). Mental health, depression, and dimensions of spirituality and religion. Journal of Adult Development, 9(2), 109–115.

Hojjati, H., Motlagh, M., Nuri, F., Sharifnia, H., Mohammadnejad, E., & Heydari, B. (2009). Relationship between different dimensions of prayer and spiritual health of patients treated with hemodialysis. Irainian journal of critical care nursing, 2(4), 149–152.

Hojjati, H., Qorbani, M., Nazari, R., Sharifnia, H., & Akhundzadeh, G. (2010). On the relationship between prayer frequency and spiritual health in patients under hemodialysis-therapy. Journal of Fundamentals of Mental Health, 12(2), 514–521.

Huebner, E. S., Drane, W., & Valois, R. F. (2000). Levels and demographic correlates of adolescent’s life satisfaction reports. School Psychology International, 21(3), 281–291.

Kattan, W., & Talwar, V. (2013). Psychiatry residents’ attitudes toward spirituality in psychiatry. Academic Psychiatry, 37(5), 360–362.

Konopack, J. F., & McAuley, E. (2012). Efficacy-mediated effects of spirituality and physical activity on quality of life: A path analysis. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 10, 57.

Krageloh, C. U., Henning, M. A., Billington, R., & Hawken, S. J. (2015). The relationship between quality of life and spirituality, religiousness, and personal beliefs of medical students. Academic Psychiatry, 39(1), 85–89.

Kvarme, L. G., Haraldstad, K., Helseth, S., Sorum, R., & Natvig, G. K. (2009). Associations between general self-efficacy and health-related quality of life among 12–13 year-old school children: a cross-sectional survey. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 7(85), 1–8.

Luquis, R., & Brelsford, G. (2012). Religiosity, spirituality, sexual attitudes, and sexual behaviors among college students. Journal of Religion and Health, 51, 601–614.

Mahboobi, M., Etemadi, M., Khorasani, E., Qiyasi, M., & Afkar, A. (2012). The relationship between spiritual health and social anxiety in chemical veterans. Iranian Journal of Military Medicine, 14(9), 186–191.

Mazloomy, M. S., Zolghadr, R., Mirzaie, A. M., & Hasanbaigi, A. (2011). Relationship between chronic stress and quality of life in female students in Yazd city in 2011. The Journal of Toloo-e-behdasht, 10(2), 1–10.

Miller, L., & Gur, M. (2002). Religiosity, depression and physical maturation in adolescent girls. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41, 206–214.

Mirghafourvand, M., Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi, S., Jafarabadi, A. M., Tavananezhad, N., & Karkhane, M. (2015). Predictors of health-related quality of life in iranian women of reproductive age. Applied Research in Quality of Life. doi:10.1007/s11482-015-9392-0.

Mirghafourvand, M., Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi, S., Tavananezhad, N., & Karkhaneh, M. (2014). Health-promoting lifestyle and its predictors among Iranian adolescent girls, 2013. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 26(4), 495–502.

Mohamadian, H., Mousavi, G. A., & Eftekhar, H. (2013). Gender variations in health-related quality of life among elementary school children. The Journal of School of Public Health and Institute of Public Health Research, 11(4), 113–127.

Musa, A. S. (2014). Factor structure of the spiritual well-being scale: Cross-cultural comparisons between Jordanian Arab and Malaysian Muslim University students in Jordan. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. doi:10.1177/1043659614537305.

Naghibi, F., Golmakani, F., Esmaily, H., & Moharari, F. (2013). The relationship between life style and the health related quality of life among the girl students of high schools in Mashhad, 2012–2013. The Iranian Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Infertility, 16(61), 9–19.

Nik-Azin, A., Naeinian, M., & Shairi, M. (2012). Validity and reliability of health related quality of life questionnaire “KIDSCREEN-27” in a sample of iranian students. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 18(4), 310–321.

Nik-Azin, A., Shairi, M., & Nainian, M. (2013). Health related quality of life in adolescents: Mental health, socio-economic status, gender, and age differences. Developmental Pscychology, 9(35), 271–281.

O’Connell, K. A., & Skevington, S. M. (2005). The relevance of spirituality, religion and personal beliefs to health-related quality of life: Themes from focus groups in Britain. British Journalof Health Psychology, 10(3), 379–398.

Pargamen, K. I., Zinnbauer, B., Scott, A. B., Butter, E. M., Zerowin, J., & Stanik, P. (1998). Red flags and religious coping: identifying some religious warning signs among people in crisis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 54(1), 77–89.

Rahimi, N., Nouhi, E., & Nakhaee, N. (2013). Spiritual health among nursing and midwifery students at kerman university of medical sciences. Hayat Journal, 19(4), 74–81.

Ravens-Sieberer, U. R., Auquier, P., Erhart, M., Gosch, A., Rajmil, L., Bruil, J., et al. (2007). The KIDSCREEN-27 quality of life measure for children and adolescents: Psychometric results from a cross-cultural survey in 13 european countries. Quality of Life Research, 16, 1347–1356.

Rew, L., & Wong, Y. J. (2006). A systematic review of associations among religiosity/spirituality and adolescent health attitudes and behaviors. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 38(4), 433–442.

Rubin, D., Dodd, M., Desai, N., Pollock, B., & Graham-Pole, J. (2009). Spirituality in well and ill adolescents and their parents: The use of two assessment scales. Pediatric Nursing, 35(1), 37–42.

Safee-Rad, I., Karimi, L., Shomoossi, N., & Ahmadi-Tahor, M. (2011). The relationship between spiritual well-being and mental health of university students. Journal of Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, 17(4), 274–280.

Sawatzky, R., Gadermann, A., & Pesut, B. (2009). An investigation of the relationships between spirituality, health status and quality of life in adolescents. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 4, 5–22.

Sawatzky, R., Pamela, A., & Lyren, C. (2005). A meta-analysis of the relationship between spirituality and quality of life. Social Indicator Research, 72, 153–188.

Statistical Center of Iran (2011). National census of population and housing of Iran. Retrieved 11/26/2014, from http://www.amar.org.ir/.

Vahedi, S., & Nazari, M. (2011). The relationship between self-alienation, spiritual well-being, economic situation and satisfaction of life: A structural equation modeling approach. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 5(1), 64–73.

Williams, P. G., Holmbeck, G. N., & Greenley, R. N. (2002). Adolescent health psychology. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(3), 828–842.

World Health Organization (1997). WHOQOL. Retrieved 7/7/2014, from http://www.who.int/mental_health/media/68.pdf.

World Health Organization (2002). Adolescent friendly health services. Retrieved 7/7/2014, from http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2003/WHO_FCH_CAH_02.14.pdf.

World Health Organization (2014). In International Conference on Population and Development. From http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/PopAspectsMDG/24_WHO.pdf.

Yanez, B., Edmondson, D., Stanton, A. L., Park, C. L., Kwan, L., Ganz, P. A., et al. (2009). Facets of spirituality as predictors of adjustment to cancer: Relative contributions of having faith and finding meaning. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(4), 730–741.

Yonker, J., Schnabelrauch, C., & Dehaan, L. (2012). The relationship between spirituality and religiosity on psychological outcomes in adolescents and emerging adults: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Adolescence, 35(2), 299–314.

Zullig, K. J., Ward, R. M., & Horn, T. (2006). The association between perceived spirituality, religiosity, and life satisfaction: The mediating role of self-rated health. Social Indicators Research, 79, 255–274.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No authors had conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mirghafourvand, M., Charandabi, S.MA., Sharajabad, F.A. et al. Spiritual Well-Being and Health-Related Quality of Life in Iranian Adolescent Girls. Community Ment Health J 52, 484–492 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-016-9988-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-016-9988-3