Abstract

Object agreement is the realization of phi features on v, whereas clitic doubling is often analyzed as the movement of a D head in order to attach to a verb. In principle, these two phenomena are distinct, but in practice they can be difficult to distinguish. In this paper, I take up the issue for the Amharic object marker, a morpheme that co-varies with the phi features of an internal argument. Evidence from its distribution and morphological form indicate that it is a doubled clitic, but it also displays a handful of properties characteristic of agreement. Building on some of the most recent clitic doubling research, I develop an Agree-based clitic doubling analysis of the object marker that accounts for both its doubled clitic-like and agreement-like properties. Overall, the paper is a case study in how to distinguish clitic doubling and agreement in a particular language, and an investigation of how to capture the relationship between these two deeply similar phenomena in linguistic theory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

1.1 Overview

Object agreement is conventionally analyzed as the realization of phi features on v (see e.g., Chomsky 2000, 2001). Clitic doubling is often claimed to be the movement of a D head into a verbal inflectional complex (see e.g., Torrego 1998; Uriagereka 1995; Nevins 2011). In principle, these two phenomena are distinct, but in practice they can be difficult to distinguish. In this paper, I take up the issue for the Ethiosemitic language Amharic, investigating the status of a morpheme called the object marker.

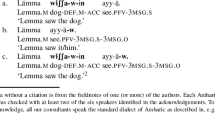

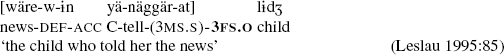

The object marker attaches to verbs and co-varies with the phi features of an internal argument. For example, in (1a), -ɨw is an object marker and refers to the third person masculine singular direct object tämariwɨn ‘the (male) student’.Footnote 1 In (1b), the object marker refers to tämariwan ‘the (female) student’ and accordingly has a different form: -at.

-

(1)

The key question that this paper investigates is whether the object marker is the reflex of object agreement or a doubled clitic.

In the remainder of the introduction, I lay out my assumptions about agreement and clitic doubling (Sect. 1.2) and briefly discuss previous work on the Amharic object marker (Sect. 1.3). Initially, the object marker seems to behave like object agreement (Sect. 2.1), and some recent work (Baker 2012) advocates for an agreement analysis. However, in Sects. 2.2 through 2.4 and Sect. 3, I argue that the object marker is best analyzed as a doubled clitic, drawing on distributional diagnostics and morphological evidence. I develop a clitic doubling analysis of the object marker in Sect. 4, proposing that the object marker undergoes A-movement to Spec,vP after an Agree relationship has been established between v and the doubled DP (cf. Béjar and Rezac 2003; Rezac 2008; Nevins 2011; Harizanov 2014). The object marker then undergoes m-merger with v (Matushansky 2006; Nevins 2011; Harizanov 2014). Section 5 concludes.

Viewed from a broad perspective, the paper is a case study in how to distinguish clitic doubling from agreement using multiple diagnostics. This is a fruitful strain of research both within individual languages (see e.g., Culbertson 2010 for French; den Dikken 2006 and Coppock and Wechsler 2012 for Hungarian; Preminger 2009 for Basque; Harizanov 2014 for Bulgarian) and across languages (see e.g., Nevins 2011; Riedel 2009). Distinguishing the two phenomena is not a simple task, and the more languages that are addressed, the more knowledge will be gained about how to accomplish it (and of course, the more knowledge will be gained about the individual languages).

The paper also has a larger theoretical impact in that it develops a systematic analysis of clitic doubling that synthesizes and confirms the latest results in clitic doubling research. Also, morphemes like the object marker—morphemes that seem to have properties of both agreement and clitic doubling—may at first blush seem difficult to treat since agreement and clitic doubling are separate phenomena in the theory. However, the paper demonstrates how current theories of clitic doubling in fact predict the existence of such morphemes. This not only reinforces these theories, but also, in the minimalist spirit, allows for an analysis of the object marker (and similar morphemes) without recourse to additional theoretical machinery.

1.2 The differences between agreement and clitic doubling

Object agreement is a fairly common phenomenon. Roughly 50 % the 108 languages surveyed in Baker (2008) have object agreement, including Basque, Slave, Fijian, and Ojibwa. A Nahuatl example is in (2).

-

(2)

As for clitic doubling, its distribution cross-linguistically is unclear, but the best-investigated cases are Spanish, Greek, Romanian, and (other) Balkan languages.Footnote 2 (3) contains examples from Greek and Rioplatense Spanish (a dialect of Spanish spoken mainly in the Rio de la Plata region in South America).

-

(3)

From a big picture perspective, there are not many differences between the object agreement marker k- in (2) and the doubled clitics lo/ton in (3)—they are all morphemes that co-vary in phi features with an internal argument of the predicate. In fact, much of the descriptive and typological literature does not make a distinction between agreement and clitic doubling, with agreement often used as a cover term for both phenomena (see e.g., Steele 1978; Corbett 2006; discussion in Woolford 2003).Footnote 3

However, if a more fine-grained perspective is adopted, many empirical differences between agreement and clitic doubling emerge. These differences often concern distribution and morphological properties. For example, in (2), k- is obligatory and a prefix on the verb. However, in (3a), (3b), the clitics are optional and do not attach as closely to the verb (i.e., they are morphophonological clitics).Footnote 4 Although some unusual instances of agreement may be optional and/or cliticize, the clearest examples of agreement are obligatory and attach via affixation. Corbett (2006) carefully catalogues the ‘canonical’ properties of agreement cross-linguistically, and throughout the paper I compare clitic doubling to canonical agreement.

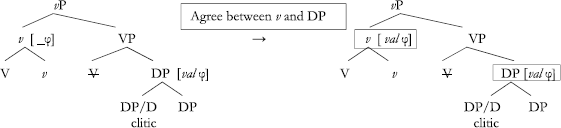

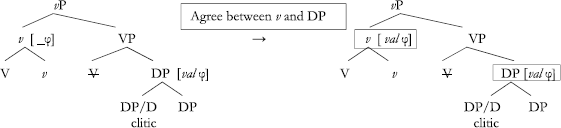

It is necessary to clarify my assumptions about the theories of agreement and clitic doubling. To start with agreement, I adopt a conventional Minimalist formalization in terms of Agree (Chomsky 2000, 2001), where Agree is a relation between a functional head and a DP that is established in the syntax. A functional head with unvalued phi-features (v for object agreement, the probe) searches downwards into its c-command domain for a DP with valued phi-features (the goal). This is shown to the left of the arrow in (4).

-

(4)

When the probe finds a DP with valued phi-features, they enter into the Agree relation and the DP values the phi-features on the probe. This is shown to the right of the arrow in (4), where v finds and Agrees with the DP complement to V. The valued phi-features on the functional head are realized at PF as the agreement marker. Object agreement is thus the phi features on v which have been valued through an Agree relation.Footnote 5

As for clitic doubling, there are two basic types of analyses. One option is to analyze the clitic as an unusual (i.e., non-canonical) agreement marker (see e.g., Borer 1984; Suñer 1988; Sportiche 1996; Anderson 2005), and the other is to analyze it as a morpheme that has moved into the verbal complex from within the DP (see e.g., Torrego 1998; Uriagereka 1995; Anagnostopoulou 2003, 2004; Rezac 2008; Nevins 2011; Roberts 2010).Footnote 6 Additionally, some research combines both analyses, depending on the type of clitic (see e.g., Bleam 1999; Ormazabal and Romero 2010).

Within Minimalism, and in much of the most recent work on clitic doubling, a movement approach has been pursued. This is partially because a movement approach fits better within the framework, and partially because there has been increasing evidence that doubled clitics have the category D (which is easily accounted for under a movement approach). I will also adopt this approach, as it serves to better account for certain properties of the object marker (see Sect. 3).

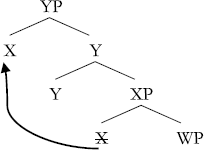

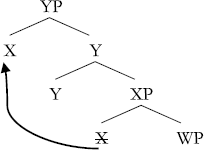

The movement approach claims that doubled clitics are D heads that move from within the DP to a verbal functional head. The identity of the verbal functional head varies depending on the proposal and language under investigation, e.g., T (Anagnostopoulou 2003), v (Nevins 2011), or F (Uriagereka 1995). In (5), this movement is presented schematically with the functional head represented neutrally as Y.

-

(5)

The movement approach raises an immediate question: what is the structure of the doubled DP that the clitic moves out of? If a D vacates a DP, under the simplest assumptions there should be no D remaining there; i.e., the DP should not have a determiner. However, doubled DPs cross-linguistically still have determiners, as seen, e.g., in (3b) above (see also Roberts 2010:130 for an example from Rioplatense Spanish).

There are various potential solutions to this problem. Anagnostopoulou (2003) argues that clitic movement is merely feature movement where the formal features of the D move to F. Alternatively, she suggests that the clitic may be a pronominal copy of the whole DP, similar to a resumptive pronoun. The most widespread solution is that the structure of the doubled DP is different than other DPs (the ‘big DP’ hypothesis: Uriagereka 1995; Roberts 2010; Nevins 2011, and many others). There are many proposals about the exact structure of the DP, i.e., how it can include both a clitic and a determiner. To take a specific example, Nevins (2011) proposes that the clitic is a simultaneously minimal and maximal projection (like a pronoun) that may be adjoined to the DP.

-

(6)

Under this analysis, the determiner heading the DP and the clitic adjoined to the DP are distinct, even though they both have the same categorial feature. Overall, in the movement approach, a doubled clitic is a D (or DP/D) that has undergone movement to a verbal functional head.

A summary of the differences seen so far between agreement and clitic doubling is in (7).

-

(7)

Agreement = affix, obligatory, realization of valued phi features on a functional head

Clitic doubling = morphophonological clitic, optional, D that has moved to a verbal functional head

This list suffices in order to begin investigating the Amharic object marker.

1.3 Previous work on the Amharic object marker

Most previous research has referred to the Amharic object marker as object agreement (see e.g., Amberber 1996, 2005; Demeke 2003; Gasser 1983; Yabe 2007; Yimam 2004, 2006). In most cases, though, the term ‘agreement’ is used in its cover term sense, without any particular theoretical commitment.Footnote 7 The clearest precedents for the present work are Mullen (1986) and Yabe (2001), who both suggest that the object marker is a doubled clitic.Footnote 8 I build on their arguments, bring new evidence to bear on the question, and develop a full clitic doubling analysis. As noted in Sect. 1.1, Baker (2012) argues that the Amharic object marker is the reflex of object agreement, and I will address his arguments throughout the paper.

2 The Amharic object marker

In this section, the basic facts of the Amharic object marker are laid out: first, its handful of agreement-like properties, and second, its many distributional similarities to a doubled clitic.

2.1 First impression: agreement

At first glance, the object marker seems to be the realization of object agreement on v. It behaves like object agreement, and not like a doubled clitic, in three main ways. First, since there is only one v per clause, an agreement account predicts only one object marker per clause, even if there are multiple internal arguments. This is borne out in Amharic (Mullen 1986:260; Leslau 1995:417). In (8), there are two internal arguments (female Almaz, masculine mäs’hafun ‘the book’), but having two object markers is ungrammatical.

-

(8)

This contrasts with the best-known cases of clitic doubling, where if there are two internal arguments, both can be doubled simultaneously.Footnote 9 An example from Greek is in (9), where both the accusative Theme to vivlio ‘the book’ and the genitive Goal tu Jani ‘John’ are doubled by clitics.

-

(9)

Baker (2012) argues that the inability to double both arguments in Amharic indicates that the object marker is object agreement.

Another way in which the object marker behaves like agreement is that it can only attach to the verbal stem, as if it were (relatively) low in the clausal spine like v. For example, in (10), the object marker -at attaches to the verbal stem fällɨg ‘look for’ and not the nonpast tense auxiliary allähu.

-

(10)

This is different from a doubled clitic, which normally attaches to the auxiliary. In the Greek example in (11), the clitic to leans on the auxiliary echo ‘have’ and not the verbal stem ghrapsi ‘written.’

-

(11)

Finally, the object marker behaves like an agreement marker in that it cross-references the highest internal argument, e.g., the Goal in a ditransitive clause (Demeke 2003; Baker 2012). Thus, it seems to be subject to locality restrictions on the Agree relation (v must agree with the highest DP in its domain), similar to object agreement in, for example, Nez Perce (Deal 2010). To take an example, in (12), the object marker must refer to the female Goal Almaz and not the masculine Theme mäs’hafun ‘the book’.

-

(12)

This is different than clitic doubling, where either the theme or the goal may be referenced. In the Greek example in (13), either or both of the Theme ta hrimata ‘the money’ and the Goal tis Marias ‘Mary’ may be doubled.Footnote 10

-

(13)

If the Amharic object marker behaved like a doubled clitic, we might expect that, even though only one object marker surfaces, that object marker could cross-reference either the theme or the goal in a ditransitive clause (especially since object markers often refer to themes in monotransitive clauses). Nevertheless, object markers in ditransitives cross-reference only Goals, and thus the object marker always cross-references the highest argument.

It is therefore plausible to analyze the object marker as agreement, but a closer look reveals some deviations from canonical agreement that render the object marker much more similar to a doubled clitic. I discuss these clitic-like properties in the next subsection, and return to the agreement-like properties of the object marker in Sect. 4.

2.2 The distribution of a clitic

Apart from the facts in Sect. 2.1, the distribution of the object marker in Amharic is very similar to the distribution of doubled clitics in other languages (Mullen 1986; Yabe 2001). I will first describe the distribution and then compare it to clitic doubling in Rioplatense Spanish (Jaeggli 1982) and to canonical agreement (Corbett 2006).

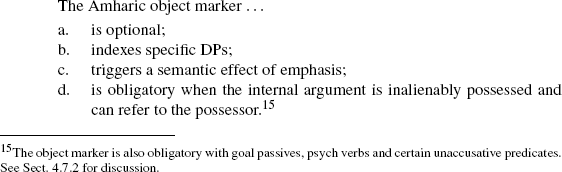

First of all, the object marker is optional. In all of the examples thus far, the object marker need not be present. (14), for example, is grammatical with or without the object marker.

-

(14)

There are also semantic restrictions on the DP that the object marker references, namely, the object marker can only cross-reference specific DPs (Yabe 2001; Haile 1970). For example, the object marker is grammatical when it cross-references a specific definite DP, e.g., doro wät’un ‘the chicken stew’ in (15). However, with a nonspecific indefinite nominal, e.g., doro wät’ ‘chicken stew’ in (16), it is ungrammatical.

-

(15)

-

(16)

Wh-words make it clear that the contrast is in specificity. The object marker may cross-reference a D-linked wh-word as in (17), but not a non-D-linked wh-word as in (18).

-

(17)

-

(18)

This indicates that the object marker may cross-reference indefinite DPs like wh-words, but only if they are specific.

The object marker also triggers a poorly understood semantic effect of some kind of emphasis on the argument which it references (reported in Haile 1970 and Demeke 2003, and confirmed in fieldwork).

-

(19)

In (19), the object marker emphasizes the particular chicken stew that was eaten.

Although the object marker is optional in the majority of contexts, it is obligatory when the internal argument has an inalienable possessor, as in (20).

-

(20)

Note that the object marker here cross-references the possessor itself, -e ‘my’ in (20).

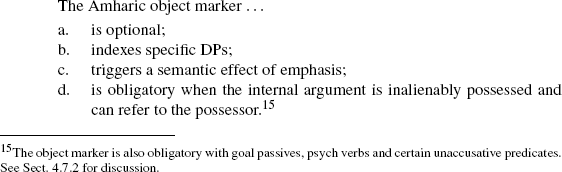

The list of distributional properties of the object marker considered in this section thus far is summarized in (21d).

-

(21)

This pattern of facts is nearly identical to one of the most well known cases of clitic doubling: Rioplatense Spanish (Jaeggli 1982; Suñer 1988; Gutiérrez-Rexach 1999). In Rioplatense Spanish, clitic doubling is optional for full DPs and is conditioned by the specificity of the object. It also triggers an effect of emphasis on the argument it doubles for some speakers (Gutiérrez-Rexach 1999:fn. 6), is obligatory for inalienably possessed objects, and refers to the possessor.Footnote 11 In the interest of analyzing empirically similar phenomena in a similar way, this is strong evidence in favor of the object marker being a doubled clitic.

This pattern is not unique to Rioplatense clitic doubling and the Amharic object marker. For example, there are similar semantic restrictions on doubling in almost all clitic doubling languages. In particular, the contrast between D-linked and non-D-linked wh-words in (17) and (18) is easily reproducible across clitic doubling languages (Kallulli 2008:237).

Canonical agreement does not share this behavior. Agreement is typically obligatory for all DPs, not optional (Corbett 2006:14–15). Moreover, agreement canonically is not conditioned by any feature of the controller of the agreement like definiteness (Corbett 2006:26), and it does not have any semantic effects (Corbett 2006:26–27). The distribution of the Amharic object marker, then, overlaps significantly with that of a doubled clitic and displays many characteristics atypical of agreement markers.

2.3 Lack of a default

Further evidence that the Amharic object marker is a clitic comes from a diagnostic that has been proposed specifically for distinguishing clitic doubling and agreement by Preminger (2009). The diagnostic exploits the fact that agreement involves feature valuation of pre-existing unvalued features on a functional head, whereas clitic doubling involves the generation (or merging) of a new D morpheme. This makes different predictions about what happens when agreement or clitic doubling fails.

The diagnostic begins by setting up a scenario where the agreement or clitic doubling relation is broken. This can occur for the Agree relation if a potential goal that is inactive intervenes between a probe and another (active) goal; this is the phenomenon of defective intervention. Defective intervention scenarios are ungrammatical in some languages (e.g., French) but in others (e.g., Icelandic), they cause the probe to surface with default phi-features. Thus, if the relation is broken and a default morpheme surfaces, then the relevant morphemes (Icelandic subject markers) are agreement morphemes under this diagnostic.

For clitic doubling, Preminger (2009) discusses how the relation can be broken if the locality conditions of clitic doubling are not abided by (roughly, the clause-mate relation). If the result is still grammatical (as Preminger 2009 shows it can be in Basque), the doubled clitic simply does not appear in the structure. There is no default clitic doubling since no phi features remain stranded to be given a default value.

In Amharic, the diagnostic can be applied using the semantic restrictions on clitic doubling, namely, that the object marker must refer to a specific DP. When there is an indefinite argument, any attempted clitic doubling relation is ungrammatical.

-

(22)

The question now becomes: how can (22) be repaired? If a default object marker is grammatical, then object markers are object agreement. If the absence of an object marker is grammatical, then the object marker is a doubled clitic. As shown in (23a), a default object marker (third person masculine singular) turns out to be ungrammatical. Leaving out the object marker entirely, though, is perfectly grammatical, as in (23b).

-

(23)

Thus, the object marker is a doubled clitic by Preminger’s diagnostic, and not the reflex of an Agree relation.

An important detail here is that default agreement is not null in Amharic in any other context. Otherwise it could not be determined whether there was default agreement in (23). For example, clausal subjects control third person masculine singular agreement even though they lack phi features.

-

(24)

Thus, if there really were default agreement in (23), we would expect it to surface overtly as a third person masculine singular object marker.

Baker (2012) proposes that there is a special null default form for the object marker in Amharic, separate from its third person masculine singular allomorph. However, this null default allomorph would be the only null default in the language. All Amharic default agreement is overt third person masculine singular; in addition to the subject agreement in (24), see, for example, Kramer (2009) on masculine singular allomorphs as the default for gender agreement within DPs. In fact, it is unclear whether any language makes use of a default form which is both (a) null and (b) distinct from other agreement morphemes in the language.Footnote 12

2.4 Binding

Finally, and perhaps most definitively, the object marker affects binding relationships. (25) shows that, while a subject can bind a possessive pronoun in the direct object, backward pronominalization between subjects and objects is nearly ungrammatical in Amharic.

-

(25)

Backward pronominalization substantially improves, however, if the object is referred to by an object marker.

-

(26)

Thus, the object marker allows for the object to bind into the subject more easily.

It is well known that clitic doubling affects binding relationships in various ways, sometimes including backwards pronominalization (see e.g. Suñer 1988:420ff. on Rioplatense Spanish; Alexiadou and Anagnostopoulou 1997; Anagnostopoulou 2003 on Greek; Harizanov 2014 on Bulgarian).Footnote 13 This is not surprising: clitic doubling involves moving a pronoun-like element (the clitic) and pronouns are intimately involved in the establishment of binding relations.

In contrast, under a minimalist theory of agreement, agreement should not be capable of affecting binding at all (Rezac 2010). Agreement markers are simply bundles of uninterpretable phi features. They cannot refer, and therefore they are predicted not to change binding relations. So, the fact that the object maker enables backward pronominalization is evidence that the object marker is a doubled clitic.

2.5 Summary

To wrap up the section, Table 1 summarizes the properties of the object marker seen so far and whether they are characteristic of agreement or of clitic doubling.

The facts in the right-hand column render it implausible that the Amharic marker is an agreement marker. Although individual members of this set of facts may be explained away as exceptional, their collective force is telling. They are all predicted if the Amharic object marker is a doubled clitic.Footnote 14 In the next section, I explore the morphological evidence that the object marker is a doubled clitic, further lengthening the right- hand column and bolstering the claim that the facts in the left-hand column are the exceptions.

3 Morphological properties

This section reviews the morphological evidence for a clitic doubling analysis of the Amharic object marker. In Sect. 3.1, I show how the object marker is formally invariant with respect to verbal features. Section 3.2 demonstrates that the object marker has the category D. Finally, in Sect. 3.3, I argue that it is a morphophonological clitic, not an affix.

3.1 Morphological invariance

Recall that an agreement morpheme is the realization of phi-features on a functional head. The realization of those phi-features may vary depending on other features that the functional head itself has e.g., a past tense feature on T or a voice-related feature on v. This is common cross-linguistically; subject agreement in Romance, for example, formally varies depending on tense, aspect and mood (e.g., Spanish cant-o ‘I am singing (present)’, cant-aba ‘I was singing (imperfect)’, and cant-e ‘I sing (subjunctive)’).

Unlike agreement markers, the object marker is invariant across verb forms (Mullen 1986). It varies only according to the phi features of the DP that it refers to, and according to certain phonological factors like whether its host (the verb) ends in a consonant or a vowel. The paradigm of the object marker is in Table 2.Footnote 15

In this section, I will show how the object marker does not formally vary no matter what aspect, tense, voice or mood the verb has.

I begin with aspect. In Amharic, subject agreement varies depending on aspect (perfect or imperfect) as shown in (27), so it is plausible that Asp bears the phi-features involved in subject agreement.

-

(27)

However, the object marker does not vary based on aspect. In (28), the object marker does not change in form depending on whether the verb it is attached to is perfect or imperfect except for the epenthetic vowel preceding the object marker in the imperfect, which is inserted only because the verbal stem ends in a consonant (see Leslau 1995:418).

-

(28)

The object marker also does not vary based on tense. In (29), the verb is past tense (see Demeke 2003 on how perfect verbs have an abstract past tense morpheme; I refrain from glossing it for simplicity), and the object marker surfaces as -t (the third person masculine singular allomorph after -u and -o).

-

(29)

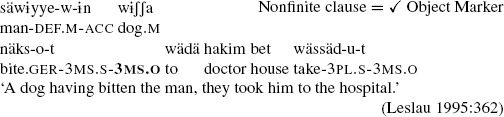

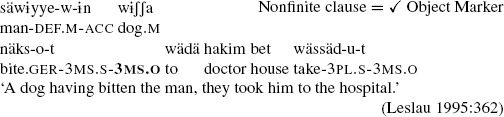

In (30), there is an object marker on a nonfinite form referred to as a gerund (Leslau 1995:355–389), but more similar to an Indo-European participle.Footnote 16 The object marker still surfaces as -t.Footnote 17

-

(30)

This behavior correlates with doubled clitics in that, cross-linguistically, doubled clitics do not vary depending on aspect or tense. Nevins (2011) has even suggested that tense-invariance is a defining property of clitics (see Sect. 3.3).

As for the features of v, agreement markers and doubled clitics again behave differently.Footnote 18 Object agreement is often absent entirely with passive and/or reflexive verbs (e.g., in Chichewa, Mohawk, and Mapudungun, Baker 2012). Doubled clitics, though, are often attested with passive verbs and unaccusative verbs (see Anagnostopoulou 2003 for Greek and Spanish examples). They are also attested with reflexive verbs, although there is often a (partially) separate set of reflexive clitics (as in e.g., Spanish). However, reflexive clitics are not found in all clitic doubling languages (e.g., they are not found in Lebanese Arabic or Hebrew). Given these cross-linguistic patterns, the Amharic object marker again behaves like a doubled clitic. It is attested in passive (31) and reflexive (32) verbs, although it does not have a separate set of reflexive forms (see also (59) for an object marker example with an unaccusative verb).

-

(31)

-

(32)

Finally, for completeness, the object marker does not vary in form on verbs inflected for different moods. For example, it is grammatical on imperatives.

-

(33)

Clitics also do not vary with mood, and are attested on, e.g., imperatives cross-linguistically.

To conclude, the object marker does not vary according to tense, aspect, mood or the features of v. This is characteristic of doubled clitics but unexpected for an agreement marker.

3.2 Object markers as Ds

Since the object marker is invariant with respect to all verbal features, but varies with respect to phi features, it seems more akin morphologically to pronominals or definite determiners rather than agreement markers. This is predicted by a clitic doubling analysis where the clitic is a D. Besides morphological invariance, there is substantial additional evidence that the Amharic object marker has the category D. I review the evidence in this section.

3.2.1 Formal similarities to possessive pronouns

The object marker shares parts of its paradigm with the paradigm for pronominal possessors (my, her, our, etc., Yabe 2001). Some basic examples with pronominal possessors are in (34).

-

(34)

The paradigm for the pronominal possessors is in Table 3.

The object marker and the pronominal possessor share more than half of their respective paradigms, with shared forms indicated by graying out in Table 3.Footnote 19 Moreover, the third person masculine singular forms, while not identical, are strikingly similar (-u for the pronominal possessor and -w in most contexts for the object marker).

The syncretism could be explained under an agreement approach to object markers if the pronominal possessors are possessor agreement. Object agreement and possessor agreement would then be syncretic. However, it is doubtful that the pronominal possessors are possessor agreement since they cannot co-occur with overt possessors, unlike possessor agreement in Hungarian (Szabolcsi 1994), Chamorro (Chung 1998), and Tzotzil (Aissen 1996), among other languages.

-

(35)

On the other hand, if pronominal possessors are analyzed as determiners/D heads (Lyons 1986; Giorgi and Longobardi 1991), then the syncretism here is easily explained. Both pronominal possessors and object markers would be the realization of a D with phi-features.

3.2.2 Formal similarities to definite determiners

Within the clitic doubling literature, it has been widely argued that formal similarities between doubled clitics and definite determiners indicate that doubled clitics are Ds (see e.g., Uriagereka 1995; Bleam 1999 for Romance; Anagnostopoulou 2003:212 for Greek; see also Preminger 2011 on the similarities between absolutive clitics and pronouns in Kaqchikel). In Amharic, feminine and plural definite markers (-wa and -u respectively) are formally distinct from third person feminine and plural object markers (-at and -atʃtʃäw, respectively). However, the masculine singular definite determiner is formally similar to the third person masculine singular object marker, as shown in (36) (C = consonant, V = vowel).

-

(36)

The object marker and the definite determiner have identical allomorphs when preceded by a vowel (-w). When preceded by a consonant, they are realized by phonologically extremely similar forms (-äw for the object marker, -u for the definite marker).

The object marker has two allomorphs, though, that the definite determiner lacks: (i) -t after [u] or [o], and (ii) -ɨw after [ʃ] and [ʃ]. In contrast, the definite determiner is (i) -w after [u] or [o] and (ii) -u after [ʃ] and [tʃ]. This is shown in (37).

-

(37)

Therefore, the morphological overlap between definite determiners and clitics initially seems rather limited.

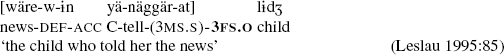

However, a closer look at the distribution of the definite determiner reveals deeper similarities. When there is a relative clause, the definite determiner attaches to the right of the verb within the relative clause (Leslau 1995:83ff.; Kramer 2010). In (38), for example, the definite determiner for the whole DP has attached to the relative clause verb yäsärräk’ä ‘stole’.

-

(38)

If the relative clause verb ends in a consonant, however, the definite determiner is realized as -äw. (Leslau 1995:84). Moreover, if the relative clause verb ends in [u] or [o], the definite determiner is realized as -t, as shown in (39).

-

(39)

In (39), the definite marker attaches to the relative clause verb yäamiwädk’u ‘fail’, giving the whole DP a definite interpretation. However, it surfaces as -t instead of its usual -w (compare (37)). Similarly, if a relative clause verb ends in [ʃ] or [tʃ], the definite marker surfaces as -ɨw, identical to the object marker.

In general, it can be concluded, then, that the allomorphs -äw, -t, and -ɨw are triggered by a D element being adjacent to a verb. Therefore, the ‘extra allomorphs’ that seemed initially specific to the object marker are in fact syncretic with the definite marker once they are put in the same morphosyntactic context.Footnote 20 I conclude that there are significant syncretisms between the definite determiner and the third person singular object marker, as predicted under a clitic doubling account.

3.2.3 The definite marker and relative clauses

The distribution of the definite determiner presents a curious puzzle: when a determiner and an object marker attach to the same host underlyingly, only the object marker surfaces. Recall that when a DP is definite and contains a relative clause, the definite determiner attaches to the verb within the relative clause—see (38). However, if the verb within the relative clause has an object marker, there is no determiner.

-

(40)

In (40), the DP is interpreted as definite but without any visible determiner.

If the object marker has the category D, this puzzle is easily solved by appealing to haplology (see e.g., Stemberger 1981; de Lacy 2000; Kramer 2009 for Amharic). I assume that the determiner attaches to the relative clause verb late in the derivation—post-syntactically (Kramer 2010). Therefore, PF need only have a rule which states: in a sequence of two D morphemes attached to a stem, the outermost D is deleted. This rule is formalized below where a dash symbolizes morphological attachment.

-

(41)

If the object marker were an agreement marker (= valued phi features on v), then the relevant rule would have to be something like, “Delete a definite marker to the right of valued phi features on v.” However, this not only loses the connection to haplology (a robust cross-linguistic phenomenon), but it also would require the definite marker to be deleted in an environment very similar to its typical context—to the right of valued phi features (on a noun; see e.g., wäre-w-ɨn ‘the news.acc’ in (40)).Footnote 21

To sum up, there is substantial evidence that the object marker has the category D like a doubled clitic: its invariance with respect to verbal features, its formal similarities to the definite marker and to possessive pronouns, and its ability to trigger haplology with the definite marker.Footnote 22 Under an agreement analysis, the object marker is a bundle of phi features, and is not predicted to have any of these properties.

3.3 Morphophonological clitic vs. affix

As noted in Sect. 1.2, agreement markers are generally affixes whereas doubled clitics are (as the name suggests) morphophonological clitics. Thus, morphophonological status (affix or clitic) is often correlated with syntactic status (valued phi features or D head). The correlation need not hold in all cases, though. For example, there are agreement markers that are morphophonological clitics (Corbett 2006:75–76) and it has been argued that there are doubled clitics which are affixes (see e.g., Monachesi 2000 on Romanian). This is similar to some of the previously investigated characteristics, like optionality. Most agreement is obligatory, and most clitic doubling is optional, but there are exceptions both ways. This type of evidence is not robust considered on its own, but its power lies in numbers. The more of the ‘typical doubled clitic’ characteristics that the object marker has, the more likely it is to be a doubled clitic (and the more difficult it is to analyze as agreement). In this section, then, I add another ‘typical doubled clitic’ characteristic to the pile: the Amharic object marker is a morphophonological clitic

The most well known criteria for distinguishing morphophonological clitics and affixes are in Zwicky and Pullum (1983). Some of the relevant criteria involving idiosyncrasy are listed in (42).

-

(42)

Criterion B: Arbitrary gaps are more common for affixes than for clitics.

Criterion C: Morphophonological idiosyncrasies are more common for affixes than for clitics.

To the best of my knowledge, the Amharic object marker behaves like a morphophonological clitic according to these criteria. It has no arbitrary gaps—the object marker is not barred with any particular verbs like stride, which lacks a past participle in English. There are also no morphophonological idiosyncrasies of the combined host and clitic form—e.g., thought for ‘think + -ed’ in English.Footnote 23

Another morphophonological criterion in Zwicky and Pullum (1983) involves attachment.

-

(43)

Criterion F: Clitics can attach to material already containing clitics, but affixes cannot.

Criterion F causes affixes to be closer to the host than morphophonological clitics—once a morphophonological clitic is added, the host effectively becomes ‘closed for business’ to affixation. This diagnostic confirms the morphophonological clitic-hood of the Amharic object marker. In Sect. 2.1, I observed that the object marker always attaches to the verbal stem, which might indicate that it is attached to v. However, it is always outside of subject agreement, contrary to Mirror Principle expectations (Baker 2012; Halefom 1994; Yimam 2004).Footnote 24

-

(44)

This contrasts strongly with object agreement, which is closer to the stem than subject agreement, as expected if it is the realization of phi features on v (see (2)). If the Amharic object marker is a morphophonological clitic and subject agreement is an affix, though, the ordering is in accord with Criterion F. See discussion in Sect. 4.6 for how the ordering is achieved under a clitic doubling analysis.

As a side note, Nevins (2011) rejects morphophonological criteria for distinguishing clitics and affixes and instead proposes a diagnostic for syntactic clitic-hood: morphological invariance with respect to tense. In Sect. 3.1, I showed that the Amharic object marker meets this criterion, so it is also classified as a clitic syntactically according to Nevins.Footnote 25

To wrap up this section, then, the Amharic object marker behaves like a morphophonological clitic (and a syntactic clitic according to Nevins 2011). This is as expected if it is a doubled clitic, but unusual at best if it is an agreement marker.

3.4 Interim summary

In Sects. 2 and 3, I have shown that the object marker is like a doubled clitic in its basic distribution, its lack of a default, its invariance with respect to verbal categories (tense, aspect, etc.), its formal similarity to D and its status as a morphophonological clitic. Some of these individual traits can be explained away while maintaining an agreement proposal, as in Baker (2012). For example, as discussed in Sect. 2.3, Baker (2012) argues that the apparent lack of a default is because there is a null default for object agreement in Amharic. Baker also argues that the object marker is one of the exceptional types of agreement markers that is a morphophonological clitic, and that it is invariant because it is the realization of a functional head that has no other purpose but to agree.

However, if these arguments are on the right track the object marker is highly exceptional. It is exceptional within Amharic since it has a null default. It is exceptional typologically as an agreement marker since it is a morphophonological clitic. It is exceptional morphologically because it is totally invariant. Viewed as a whole, the facts presented in this section form a clearer, less exceptional picture: that the object marker is simply a doubled clitic. In the next section, I propose a clitic doubling analysis of the object marker and address its handful of remaining agreement-like properties.

4 A clitic doubling analysis

This section develops an analysis of the object marker that builds on many recent proposals on clitic doubling in order to account for the Amharic data. That said, the main tenets of the analysis are not Amharic-specific. It is intended to serve as an all-purpose analysis of clitic doubling that can be adopted and adapted for multiple languages.

In Sect. 3, it was shown that the object marker has the category D. To be more precise, since the object marker itself does not project arguments and is not modified by adjuncts, it is either a D head (like a determiner) or a simultaneously maximal/minimal DP/D projection (like a pronoun, as per Bare Phrase Structure definitions of projection; Chomsky 1995:241ff.). Recall from Sect. 2 that the object marker can allow for new binding relationships. (It allows backward pronominalization; see (26)); this indicates that it can refer and therefore is a DP/D pronoun. Now, it is clear that the object marker ends up part of a complex head that also includes the verbal stem. If the object marker has the category DP/D, then it must have undergone movement from some position where the DP/D is licensed into a verbal projection.Footnote 26

Three questions then become crucial: where does the clitic start from? Where does the clitic move to? What are the properties of that movement (how is it licensed and what kind of movement is it)? In the following sections, I go through each of these answers in turn. In Sect. 4.1, I suggest that the object marker is adjoined to the DP, following Nevins (2011). In Sects. 4.2 and 4.3, I argue that the clitic moves to Spec,vP and undergoes m-merger with v (Matushansky 2006), and that the movement of the clitic to Spec,vP is A-movement licensed by an Agree relation. In Sect. 4.4, I explore the limits of Nevins (2011), and suggest a more radical alternative for the origin of the clitic following Harizanov (2014). Section 4.5 has an interim summary, and shows how a clitic doubling analysis accounts for the specific properties of the object marker. Section 4.6 addresses the ditransitive data and ‘one object marker’ restriction from Sect. 2.1. Finally, Sect. 4.7 briefly addresses some additional contexts where the object marker can be found.

4.1 The origin of the clitic: adjunct analysis

Much of the clitic doubling literature is concerned with the original location of the clitic in the derivation. A variety of ‘big DPs’ have been proposed that accommodate both the doubled DP and the clitic under the same DP node (see discussion in Sect. 1.2; Torrego 1998; Uriagereka 1995; Rezac 2008; Nevins 2011; Roberts 2010; Anagnostopoulou 2003 (in part) and many others). Here, I adopt the adjunct analysis (Nevins 2011), where a doubled clitic is merged as a DP/D adjoined to the doubled DP, similar to a floated quantifier (Haegeman 2006).

-

(45)

Also like a floated quantifier, it can be detached from the DP during the derivation. Nevins (2011) does not discuss how the clitic and the adjoined DP are required to have the same phi features, but it is presumably the same mechanism that forces a floated quantifier and a DP to have the same phi features in languages like Spanish, French, Arabic, etc. (see Bobaljik 2003 for an overview of some specific proposals).

If (45) is the same structure used for floated quantifiers, then the structure is in fact generally available in the language and quantifiers can surface in the DP-adjoined position (as in, e.g., todas las personas ‘all the people’ in Spanish with the quantifier adjoined on the left, or säw-otʃtʃ-u hullu people-pl-def all ‘all the people’ in Amharic, with the quantifier adjoined on the right). The structure in (45) is also reminiscent of the appositional adjunction of pronouns to a DP (e.g., nosotros las estudiantes ‘we the students’ in Spanish, or ɨñña tämar-otʃtʃ-u we student-pl-def ‘we the students’ in Amharic). So, initially, this kind of ‘big DP’ seems plausible for Amharic and other languages.

The question is now: how does the object marker end up part of a complex verbal head? Following Nevins (2011) and Harizanov (2014), I will argue that the object marker undergoes A-movement to Spec,vP, and then undergoes m-merger (Matushansky 2006) with v. The A-movement of the object marker is discussed in Sect. 4.2, and m-merger is discussed in Sect. 4.3.

4.2 The mechanics of A-movement

Clitic doubling shows evidence of A-movement across languages (see Alexiadou and Anagnostopoulou 1997, 2000; Anagnostopoulou 2003 for Greek; Harizanov 2014 for Bulgarian, among others), and Amharic is no exception. The object marker allows for new binding relationships (see (26)), indicating that there is an A-chain between the object marker and the doubled DP.Footnote 27

I propose that the object marker (and doubled clitics in general) move to the specifier of vP. This is a common component of recent analyses on clitic doubling (Nevins 2011; Harizanov 2014), but it also has support within Amharic. The object marker needs to be somewhere that it can combine morphologically with the lexical verb, but still be in a relatively low projection since the object marker does not attach to auxiliaries; v fits the bill on both counts. Also, I follow Chomsky (2001) in assuming that all clauses contain a v, and it is preferable for economy purposes to have the landing site of the clitic be a projection that is independently necessary in the derivation.Footnote 28

So far, then, the analysis is that the clitic is merged adjoined to DP and it undergoes A-movement to the specifier of vP. Standard minimalism assumes that the operation Move is a combination of the two operations Agree and Merge (Chomsky 2000, 2001). Therefore, v must enter into an Agree relation with a DP before that DP moves to Spec,vP. In other words, object agreement between v and a DP that it c-commands is a precondition for any movement of (a component of) that DP to Spec,vP.

This correlates with recent clitic doubling literature where the movement of the clitic is licensed by an Agree relation between a functional head and a DP (Béjar and Rezac 2003; Rezac 2004, 2008; Roberts 2010; Nevins 2011; Preminger 2011). This may seem unexpected since I have assumed throughout this paper that clitic doubling and agreement are distinct phenomena. Clitic doubling, though, remains distinct from the valuation of phi features on the functional head in all respects: it involves movement of a DP/D to Spec,vP, m-merger with v, and ultimately realization of some D as the clitic itself. The clitic is not the realization of phi features on a verbal functional head, and it undergoes movement, unlike an agreement marker.

One of the recent accounts that clearly differentiates clitic doubling and agreement is Rezac (2008), where clitic doubling is the result of the movement of a D to a functional head after an Agree relationship has been established between a functional head and the containing DP. The result is that there are valued phi features and the doubled clitic on the functional head, and a full DP in argument position. All of the components can be spelled out separately, as in West Flemish complementizer agreement in (46). This makes it clear that the agreement marker and the doubled clitic can be distinct morphologically.

-

(46)

However, as Rezac notes, not all of the components are required to be realized, e.g., one or more may be null or some may be realized together as one morpheme (see also Béjar and Rezac 2003; Preminger 2011 for detailed discussion of clitic doubling as distinct from, but licensed by, agreement).

A schematic derivation illustrating the analysis so far is in (47). (I assume the verb has already moved to v; see Roberts 2010:55ff. for technical discussion of the timing.) The Agree relationship is created between v and a DP in its c-command domain and the phi features on v are valued.

-

(47)

After v agrees with the DP, the clitic moves to Spec,vP (see Sect. 4.4 for discussion of why the clitic and not the full DP is moved).

Under this kind of Agree-based analysis of clitic doubling, Amharic has object agreement, i.e., an Agree relationship must be established between v and a DP and it results in valued phi features on v. However, this object agreement is always phonologically null, just like object agreement in other clitic doubling languages under Nevins’s account. Why should this be? Preminger (2011:69) proposes that there may be a general preference for pronominal material (= the clitic) to be expressed over functional material (= agreement). Alternatively, Rezac (2008) suggests that the lack of realization of agreement may be due to morphological economy (building on Kinyalolo 1991). Since the clitic moves to be local to the valued phi features (and expresses the same phi features), there is little motivation to have object agreement also be morphologically expressed.Footnote 29 , Footnote 30

4.3 M-Merger

I have covered where the object marker starts and what kind of movement it undergoes. However, it remains to be seen how the DP/D in Spec,vP ends up as part of a complex verbal head including v. I will follow Nevins (2011) and Harizanov (2014) who propose that the clitic undergoes m-merger (Matushansky 2006) with v. To explain m-merger, however, one must first explain Matushansky’s redefinition of head movement.

Traditionally, head movement occurs when one head moves to adjoin to another head, but this has caused problems with the elegance of the theory of movement from the beginning (e.g., it violates the Extension Condition). To remedy this, Matushansky proposes that head movement is exactly like phrasal movement except that it is driven by c(ategorial)-selection and not Agree. If a head Y c-selects for XP, then X can undergo movement to the specifier of YP. The result is a head in specifier position, as in (48).

-

(48)

The question is then, what happens next? This is where m-merger enters the picture. Matushansky proposes that m-merger changes a structure like (48), where a given head (X) is a specifier (of YP), to structures like (49), where the head (X) adjoins to the head (Y) of the projection of which it was the specifier (YP).

-

(49)

Crucially, there are two heads in (48) but only one (complex) head in (49).

Matushansky (2006) argues that m-merger can also occur without head movement. She points to Romance cliticization, where a DP/D clitic moves to a specifier of XP and then m-merges with the head of XP; it can undergo m-merger since it is a head (as well as being a maximal projection).

A similar approach can capture the Amharic facts. The adjoined DP/D undergoes phrasal movement to Spec,vP and then undergoes m-merger with v. This is shown schematically in (50) (again with the verb having already undergone head movement (and m-merger in Matushansky’s system) with v).Footnote 31

-

(50)

(50) provides a way to analyze the Amharic object marker as a pronoun that moves like a phrase but ends up part of a complex head with a low verbal projection (v).

4.4 An alternative to the adjunct analysis

The adjunct analysis is a lucid and well-supported example of the traditional ‘big DP’ analysis of clitic doubling, but it faces a few problems. First, it is left open why the adjoined DP/D clitic is chosen to move to Spec,vP, and not the larger DP which it is adjoined to. Additionally, it is unclear whether the clitic and the doubled DP form a chain. Instead, it seems that the clitic forms a chain with itself, i.e., with the copy of itself in the adjoined position where it is originally merged. If the clitic does not form a chain with the doubled DP, then it is not as obvious how it can extend the binding possibilities of that DP. Finally, it is difficult under the adjunct analysis to force clitic doubling when a clitic is merged; object markers never surface adjoined to DPs, but there is no mechanism in the adjunct analysis that will cause them to move obligatorily after being (externally) merged.

I briefly explore an alternative to the adjunct analysis that may address these problems but is significantly more radical. I will call this analysis the copy analysis (suggested in Harizanov 2014), and it is nearly identical to the adjunct analysis since it assumes that there is movement to Spec,vP and then m-merger with v. However, the difference is in the origin of the clitic. The doubled DP itself moves to Spec,vP and then both copies of the doubled DP are pronounced. The topmost copy surfaces as a clitic/object marker via the following modification of m-merger (Matushansky 2006).

Harizanov proposes that m-merger can apply to structures that have a branching projection as a specifier. When a branching projection undergoes m-merger with a head, a ‘reduced’ version of the branching projection is adjoined to the head. Specifically, I propose that m-merger reduces the branching node to its head. The relevant operations are shown schematically for a doubled clitic in (51).

-

(51)

The DP direct object moves to Spec,vP to the left of the arrow in (51a), and then undergoes m-merger with v. Under the copy analysis, it is ‘reduced’ to just its head–D. This head naturally has a D categorial feature, and it also has phi features since determiners vary with gender and number in Amharic (Kramer 2009); therefore, it has all the features necessary to be morphophonologically realized as the object marker. The copy analysis, in a sense, cashes out Anagnostopoulou’s (2003) suggestion that the clitic is a pronominal copy of the doubled DP, like a resumptive pronoun.

A crucial part of the copy analysis is that both ‘copies’ of the DP are pronounced—the full DP which is sister to V and the ‘reduced’ D which is adjoined to v. This is expected since, at PF, the two copies will be distinct, as defined in Kandybowicz (2007) and earlier work on the copy theory of movement (cf. Nunes 2004; Landau 2006; Bošković and Nunes 2007).Footnote 32

Under the copy analysis, all the problems detailed above are avoided. The doubled DP itself moves to Spec,vP (not an adjoined clitic), and this naturally affects that DP’s binding relations. Also, there is no separate clitic adjoined to the DP that must somehow be forced to move. However, the copy analysis is not perfect. The revision of the m-merger operation (so that it can apply to branching projections) needs to be further justified by independent examples of branching projections m-merging with heads across languages. Moreover, from the vantage point of the theory of movement, it is an important question whether other putative cases of head movement are in fact phrasal movement followed by m-merger.Footnote 33 However, the copy analysis addresses the clitic doubling data well, and I tentatively adopt it henceforth.

In the copy analysis, a DP enters into the Agree relation with v and then moves to Spec,vP. This movement is optional, and must somehow be restricted to only specific DPs (since only specific DPs can be referenced by the object marker). In the establishment of an Agree relation, movement to Spec,vP, optionality, and sensitivity to specificity, clitic doubling is identical to object shift (see Holmberg 1986 and Diesing 1992, an overview by Thráinsson 2001, and a minimalist approach in Chomsky 2000, 2001). It has even been argued that clitic doubling is in fact reducible to object shift (Nevins 2011; Suñer 2000).

However, there are some reasons not to consider these two phenomena identical. First of all, clitic doubling is also available for subjects, although less commonly (Arregi and Nevins 2008; Preminger 2009). Also, in Basque (Arregi and Nevins 2008; Preminger 2009) and certain Mayan languages (e.g., Kaqchikel; Preminger 2011), there are verbal markers that are rather clearly doubled clitics but they are obligatory (modulo certain structural restrictions) and not subject to specificity restrictions. Therefore, clitic doubling is at best a less unitary phenomenon than object shift in terms of optionality and specificity restrictions.

A plausible approach to these facts comes from extending part of Baker’s (2012) analysis of the Amharic object marker. I assume that in languages with optional clitic doubling subject to specificity restrictions (e.g., Amharic, Spanish, Greek), specific objects optionally undergo object shift to a projection between v and V. Following Thráinsson (2001), I also assume that shifted objects can only be interpreted specifically. That is, the landing site of a shifted object is only compatible with a specific interpretation—similar to Diesing’s (1992) classic Mapping Hypothesis (see also Chomsky 2001:35(61b)).

Following Baker (2012), I propose that if (and only if) a DP undergoes object shift, then it is capable of being referred to with an object marker. In other words, optional object shift feeds clitic doubling, causing a doubled DP to be close enough to v for v to Agree with it. Since only specific DPs undergo object shift, then only specific DPs are clitic doubled (and clitic doubling seems to have specificity restrictions). I assume that clitic doubling itself is an “obligatory operation” as defined in Preminger (2011), such that clitic doubling always happens if it can, but there is no crash if it cannot.Footnote 34

In contrast, in languages like Basque and Kaqchikel, there is no object shift and no projection between v and V. Hence, v can always access the relevant DP and clitic doubling is obligatory and with no specificity restrictions. This is barely a sketch of an analysis and it leaves certain crucial questions open like whether there is evidence for an (albeit small) movement of the clitic doubled DP in languages like Amharic, Spanish and Greek (see Baker 2012 for some thoughts on Amharic). However, it is a start on an explanation for why the object marker in Amharic is optional and subject to specificity restrictions, without reducing clitic doubling to object shift.Footnote 35

4.5 Interim summary and data review

I have argued that the object marker is a ‘reduced’ version of the full DP itself, specifically, the head of the DP after the DP has A-moved to Spec,vP and undergone m-merger with v. With this much analysis in place, I now briefly review the characteristics of the object marker and how the analysis explains them.

Several of the key clitic-like properties of the Amharic object marker have already been discussed above. All the properties related to having the category D as well as invariance are captured by having the object marker be the realization of a D head (the reduced version of a DP) adjoined to v. The object marker allows for new binding relations since it undergoes A-movement, and it seems optional in that it is fed by optional object shift and the derivation does not crash if clitic doubling does not occur (Preminger 2011). Moreover, since object shift feeds clitic doubling, the Amharic object marker can only reference specific DPs.

Recall from Sect. 3.3 that the object marker surfaces outside of subject agreement in the verbal complex head (and thus it is a morphophonological clitic). This is derivable under the current analysis in the following way. When a head X m-merges with another head Y, X is adjoined to the left of Y. This follows the conventions of head movement. Therefore, the reduced DP in (51) adjoins as a D to the left of the [V-v] complex. Recall that subject agreement is on Asp in Amharic (Sect. 3.1). I propose that, in Amharic, the complex [D-V-v] head undergoes head movement to Spec,AspP, and then m-merges with Asp.Footnote 36 This yields the following complex head; Asp is shown with phi features to represent subject agreement.

-

(52)

As Nevins (2011) notes, complex head structures like (52) encode hierarchical relations but not linear relations. When this structure reaches PF, the information that the object marker is an enclitic is accessed, and the object marker is linearized at the right edge of the complex head.Footnote 37 Therefore, the object marker surfaces to the right of Asp, i.e., to the right of subject agreement as attested.

The analysis also explains why the object marker does not attach to auxiliaries, as shown in (53).

-

(53)

All that needs to be said is that Asp does not undergo head movement when there is an auxiliary in T. This means that the clitic, attached to v, remains in the same complex head as the verb (and subject agreement, realized as a prefix in imperfective aspect), and does not surface on the auxiliary.Footnote 38

As observed in Sect. 2.2, when a DP is referenced by the object marker in Amharic, native speakers report a meaning of “emphasis” on the doubled DP. This semantic effect will require careful fieldwork to clarify. However, object shift is often associated with topicality, so it may be that the intuitive emphasis corresponds to topic-hood if all doubled DPs undergo object shift. Therefore, a clitic doubling analysis of the object marker gives it the potential to have a semantic effect.

The lack of a default object marker is also predicted by the current analysis. The key case is when there is a non-specific direct object; instead of a default object marker being generated in such cases, there is simply no object marker whatsoever. Recall that object shift feeds clitic doubling, and that clitic doubling is obligatory when possible but does not cause a crash if it does not occur. If the object is non-specific, the object will not shift to a location where it can be accessed by v; clitic doubling will not be possible since there is no accessible argument, but the derivation continues without crashing.Footnote 39 Therefore, the analysis predicts that, rather than there being a default object marker when there is a non-specific direct object, there is simply no object marker whatsoever in the resulting grammatical string.

The final property to be accounted for is the obligatoriness of clitic doubling with inalienable possessors, and here is where the limits of the present analysis are reached. There are at least three analyses on the market for Spanish and they are rather divergent (Jaeggli 1982 based on theta roles; Bleam 1999 based on the movement of the inalienable possessor out of the DP; Roberts 2010 based on the externalization of the possessor within the DP). To the extent that this effect is common across clitic doubling languages (on e.g., Bulgarian, see Franks and King 2000:276; Harizanov 2014), it seems best to assume that some component of clitic doubling will ultimately explain it, thus lending further support to analyzing the Amharic object marker as a doubled clitic.Footnote 40

4.6 Ditransitive clauses

The focus thus far has been on doubled clitics appearing with monotransitive verbs. The object marker can also appear with ditransitive verbs, and it references the highest internal argument of a ditransitive verb. In (54), it references the female Goal Almaz and cannot reference the masculine Theme mäs’haf-u ‘the book’.Footnote 41

-

(54)

Baker (2012) takes this as evidence for an agreement analysis of the object marker. However, an Agree-based analysis of clitic doubling also predicts this fact. The v will enter into an Agree relation with the highest DP in its c-command domain—the Goal.

I conclude that the evidence in (54) is neutral between an agreement and a clitic doubling analysis. However, I submit that a clitic doubling analysis is the preferred analysis, since it captures not only (54) but also the D-like morphology, binding effects, etc. of the object marker. An Agree-based analysis of the object marker thus provides a way to reconcile the Agree-like locality of the object marker with its otherwise clitic-like behavior.

An Agree-based analysis of clitic doubling, though, predicts that the highest argument will always be the one that is doubled, whereas doubled clitics across languages can refer to both arguments with two clitics surfacing. There are at least two ways to accomplish this. Nevins (2011) proposes that when two clitics surface, there has been an application of Multiple Agree (Hiraiwa 2004; Nevins 2007). Then, all that needs to be said is that Amharic does not have Multiple Agree.Footnote 42 Alternatively, languages that have two clitics surface could have two probes that trigger clitic doubling (with the doubled clitics ending up as part of the same complex head). Amharic would then have only one probe that triggers clitic doubling (v, in the present analysis). Either analysis in fact predicts the existence of morphemes like the Amharic object marker; if clitics can be generated via Multiple Agree or multiple probes, then it would seem highly suspicious if they could not be generated in some language via (single) Agree or a single probe.

However, this raises the question of why all clitic doubling languages seem to have either Multiple Agree or multiple probes triggering clitic doubling. This may be because the ability to have multiple clitics present has been taken as a hallmark of clitic doubling itself, as assumed here and in Baker (2012). If a language can only have one morpheme that refers to an internal argument, it is often assumed to be object agreement without much investigation. Hopefully future work will keep clitic doubling in mind as a possibility, especially given the morphological and distributional tests above. In the meantime, there are several, less well-known languages that have (been argued to have) clitic doubling, but just one clitic surfaces: Hungarian (den Dikken 2006), Arabic (Shlonsky 1997:192), Kaqchikel (Preminger 2011), and Chaha (Ethiosemitic: Banksira 2000:256). This may be because these languages, like Amharic, only have Agree or only have a single probe that triggers clitic doubling (note that two of them are Semitic).

Overall, the Agree-based analysis of clitic doubling predicts the ditransitive data while also capturing the clitic properties of the object marker, and shows some promise in accounting for clitic doubling in ditransitives across languages.Footnote 43

4.7 Coda: additional data

In this section, I examine two additional sets of data with respect to the clitic/affix status of the object marker: prepositional object markers, and a set of contexts where the object marker is obligatory.

4.7.1 Prepositional object markers

Previously, we have seen that the object marker can refer to Themes and to Goals. It can also, however, refer to malefactive arguments and benefactive arguments. In these cases, there is an additional element within the verbal complex which looks like a reduced version of either the preposition/case marker bä- ‘in, at, by’ or the preposition/case marker lä- ‘to, for’. Some basic examples are in (55) and (56).

-

(55)

-

(56)

In (55), the object marker is third person feminine singular referring to Aster, the malefactive argument, and it is preceded by the element -bb-. In (56), Aster is the benefactive argument referred to by the object marker, and it is preceded by -ll-. Because of the resemblance between -ll-/-bb- and the prepositions/case markers, object markers in this context are often called ‘prepositional object markers’ and I will refer to them as such here as well. The use of -ll- is fairly limited to benefactives (and I thus gloss it as ben), but -bb- can be used for instruments and locatives as well (and it is thus glossed as instr in an example below; see Leslau 1995:428–429).Footnote 44 Note that -ll- and -bb- never occur without a following object marker, and that the sequences -bbat and -llat are optional in the examples above.

These constructions (often referred to as applicatives) have been the subject of much research within the Amharic literature (Hetzron 1970; Mullen 1986; Amberber 1996, 2002; Demeke 2003; Yabe 2007). However, there is little consensus about their proper analysis, with the categorial status of -ll-/-bb- particularly in dispute. There are at least three different hypotheses: that these markers form part of a multi-morphemic agreement marker/clitic along with the object marker (Amberber 1996; Mullen 1986), that they are inflectional applicative heads (Demeke 2003), and that they are incorporated prepositions (Yabe 2007).

Regardless of -ll-/-bb-, though, prepositional object markers behave like ‘normal’ (non-prepositional) object markers. First of all, there can only be one prepositional object marker per clause and it must refer to the highest argument. For example, (57a) contains both a benefactive and an instrumental argument, but only a single benefactive prepositional object marker can surface (compare (57b) and (57c); see McGinnis 2008 on how benefactives are higher than instrumentals).Footnote 45

-

(57)

Additionally, prepositional object markers do not attach to auxiliaries (Leslau 1995:426), and attach to the verb outside of subject agreement (see 57a). They are also subject to the same specificity restrictions as normal object markers (Haile 1970; Amberber 1996; Demeke 2003), and trigger a similar semantic effect of emphasis (Haile 1970). They are optional as noted above, and do not trigger a default.Footnote 46

Moreover, they trigger haplology when attached to a verb that ends in a D. For example, in (58) the definite marker cannot surface on the verb in the relative clause, despite the whole DP being interpreted as definite. I submit that this would violate the haplology rule for determiners proposed in (41).

-

(58)

The prepositional object marker thus behaves like a doubled clitic in the same ways as a ‘normal’ object marker and supports the analysis of all object markers as clitics in Amharic.Footnote 47

However, we can also ask which type of marker is more likely to mark malefactives/benefactives: agreement markers or doubled clitics? That is, does the sheer existence of an object marker referencing malefactives/benefactives have a bearing on the main question of the paper: whether they are agreement markers or clitics? The answer to this question is not entirely clear. From a cross-linguistic perspective, it has not been directly investigated whether agreement or clitic doubling is more likely when benefactive/malefactives are referenced on the verb. However, doubled clitics are compatible with benefactive/malefactive interpretations of the doubled DP in several of the well-known clitic doubling languages, including Spanish (see e.g., Belloro 2007) and many Balkan languages (Rivero 2004).

Overall, then, the prepositional object marker does not offer any additional evidence for object markers being clitics, but is perfectly compatible with a clitic analysis.Footnote 48

4.7.2 Obligatory contexts

Baker (2012) observes that the object marker is obligatory in a certain set of contexts. These contexts are: (i) the Goal when certain ditransitive verbs are passivized (A book was given to Almaz), (ii) the Possessor in an existential have-predication (Women have grace), (iii) the Experiencer in certain non-agentive/psychological verbs (Almaz is sick; called impersonal verbs in Leslau 1995; see also Amberber 2005), and (iv) the affected argument in a dyadic unaccusative verb. An example of (iv) is in (59).

-

(59)

To be clear, the object marker in these contexts is obligatory in that it must be present regardless of the specificity of the doubled DP. For example, the object marker may refer to a non D-linked wh-word Experiencer of a psych predicate (= (iii) above).

-

(60)

Baker observes that the object marker here is behaving exactly like subject agreement (obligatory with all DPs) and he concludes that the object marker is in fact agreement. He claims that object agreement is obligatory because Experiencers are merged high enough to be in the domain of the head that carries object agreement, whereas Themes must undergo optional object shift to enter this domain (see Sect. 4.5).

However, an agreement analysis misses a strong cross-linguistic generalization. This pattern of facts (obligatoriness of some marker that references the Experiencer in the above contexts) is robustly found in languages that uncontroversially have clitic doubling. The doubled clitic is obligatory at least for Experiencers in psychological predicates in every clitic doubling language for which significant data is available including Spanish (Torrego 1998), Greek (Anagnostopoulou 2003), Romanian (Dobrovie-Sorin 1994), Albanian (Kallulli 2000), Bulgarian (Krapova and Cinque 2008), and Macedonian (Krapova and Cinque 2008). In many of these languages, clitic doubling has been reported to be obligatory in some or all of the other contexts mentioned above including goal passives (Greek and Spanish, Anagnostopoulou 2003), dyadic unaccusatives (Greek, Anagnostopoulou 2003; Albanian, Kallulli 2000), and existentials (Bulgarian; Krapova and Cinque 2008). In Bulgarian (Krapova and Cinque 2008) and Romanian (Dobrovie-Sorin 1994), the clitic is even obligatory in these contexts regardless of specificity, identically to the Amharic object marker.

Therefore, the fact that the Amharic object marker is obligatory in these contexts does not mean that it must be an agreement marker. This distribution is strongly associated with clitic doubling languages, and the fact that Amharic also displays it is in fact evidence for the object marker being a doubled clitic. The fact that this distribution is so widely attested of course cries out for an explanation. Baker’s (2012) explanation is compatible with the approach taken here where clitic doubling is licensed by an Agree relation; it is possible that Experiencers trigger obligatory clitic doubling because they are automatically in the agreement domain of v. In contrast, Anagnostopoulou (2003) has argued extensively that clitic doubling of the higher argument in Greek is obligatory whenever a lower argument is A-moved across a higher argument. It remains to be seen how broadly either analysis will be able to apply, across Amharic and other languages.Footnote 49

Overall, I have argued that prepositional object markers are clitics and thus support a clitic analysis of object markers, and that the obligatory uses of the object marker are in fact characteristic of clitic doubling.

5 Conclusion

I conclude that the Amharic object marker is a doubled clitic. If it were an agreement marker, it would be unusual in that it would: lack a default, have the category D, not display any allomorphy based on verbal categories, be a morphophonological clitic, affect binding relationships and, finally, be generally optional but obligatory only with inalienable possessors and the arguments discussed in Sect. 4.7. In contrast, all of these properties are characteristic of clitic doubling across languages. Synthesizing and building on recent work in clitic doubling, I developed an Agree-based analysis of the object marker explains nearly the whole list of empirical characteristics.

The Amharic object marker was never an open-and-shut case of clitic doubling, though. It displays a handful of properties that seem characteristic of agreement: a low position on the verb, referring to the highest argument in a ditransitive, and having only one object marker per clause. However, these properties hold because Amharic is an atypical clitic doubling language—it does not use Multiple Agree (or it only has a single probe for clitic doubling) and it targets v for cliticization. I hope that the research here will thus allow for new questions to be asked about languages with purported object agreement. Do the purported object agreement morphemes have the morphology of Ds? Can they affect binding relations? Are there any semantic restrictions on their distribution? If so, they could be doubled clitics.

In general, the literature on clitic doubling is vast, complex, and bursting with data, but it has focused largely on clear-cut cases of clitic doubling in Greek, Spanish, etc. The present paper’s contribution is in mapping out the largely uncharted territory at the boundary between agreement and clitic doubling.

Notes

Note that Amharic is head-final, unlike the Central Semitic languages.

On Spanish (standard and dialects), see e.g., Jaeggli (1982); Bleam (1999); Suñer (1988); Uriagereka (1995); Ormazabal and Romero (2010). On Greek, see e.g., Anagnostopoulou (2003, 2004) and Philippaki-Warburton et al. (2004). On Romanian, see e.g., Dobrovie-Sorin (1990, 1994). On Balkan languages, see Kallulli and Tasmowski (2008) (and particularly on Bulgarian, see Harizanov 2014). See also Borer (1984) on Hebrew; Aoun (1999) on Lebanese Arabic; Shlonsky (1997) on both Hebrew and Arabic; Arregi and Nevins (2008) on Basque, and Banksira (2000) on Chaha (an Ethiosemitic language).

A terminological clarification: I will use the terms ‘affix’ and ‘morphophonological clitic’ for, respectively, ‘a bound morpheme that is tightly attached to its host’ and ‘a bound morpheme that is more loosely attached to its host’. The term ‘clitic’ will refer only to syntactic clitic-hood henceforth.

Conventionally, the probe also values the Case feature on the DP. When v agrees with a DP, it assigns the DP accusative Case. However, Baker (2012) argues that accusative case in Amharic is not assigned via Agree. Instead, it is assigned hierarchically such that when there is a c-command relationship between two DPs in a clause, the lower DP receives accusative (cf. Marantz 1991). I will follow Baker in this respect, and therefore the theory of agreement does not make any predictions about Case/case in Amharic. See fn. 47 for further discussion of Baker’s analysis of Amharic case in the light of a clitic doubling analysis of the object marker.

See the detailed literature review in Anagnostopoulou (2006). An additional analysis is that the doubled DP is a (right-dislocated) adjunct, the clitic is merged in complement position, and the clitic moves to adjoin to a verbal head (see e.g., Aoun 1981; Philippaki-Warburton et al. 2004). This theory has not been widely adopted, so I set it aside here; see arguments against it in Jaeggli (1986), Harizanov (2014), and Anagnostopoulou (2006).