Abstract

Verbal agreement is normally in person, number and gender, but Hungarian verbs agree with their objects in definiteness instead: a Hungarian verb appears in the objective conjugation when it governs a definite object. The sensitivity of the objective conjugation suffixes to the definiteness of the object has been attributed to the supposition that they function as incorporated object pronouns (Szamosi 1974; den Dikken 2006), but we argue instead that they are agreement markers registering the object’s formal, not semantic, definiteness. Evidence comes from anaphoric binding, null anaphora (pro-drop), extraction islands, and the insensitivity of the objective conjugation to any of the factors known to condition the use of affixal and clitic pronominals. We propose that the objective conjugation is triggered by a formal definiteness feature and offer a grammar that determines, for a given complement of a verb, whether it triggers the objective conjugation on the verb. Although the objective conjugation suffixes are not pronominal, they are thought to derive historically from incorporated pronouns (Hajdú 1972), and we suggest that while referentiality and ϕ-features were largely lost, an association with topicality led to a formal condition of object definiteness. The result is an agreement marker that lacks ϕ-features.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Verbal agreement affixes evolve historically from the morphological incorporation of pronominal arguments into their verbal heads (Bopp 1842; Givón 1976; Bresnan and Mchombo 1987). Although agreement markers retain some qualities of the incorporated pronouns from which they derive, the two are fundamentally quite different. An incorporated pronoun is referential and functions as an argument, while an agreement affix has lost its referential status, and serves instead to register grammatical features of an argument phrase. This distinction therefore has wide-ranging grammatical consequences, interacting with issues such as reference, pronoun binding, argument omission, and extraction.

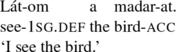

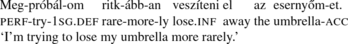

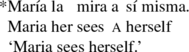

Despite those differences, it is not always obvious whether verb inflections in a given language are properly analyzed as pronominal affixes or agreement markers, and indeed this question has been the topic of spirited scholarly debate for many languages.Footnote 1 This paper addresses this issue for verbs in Hungarian, which are unusual in that they cross-reference a formal definiteness feature of the object, rather than its ϕ-features (person, number, and gender), although ϕ-features also play a role in their distribution. Hungarian verbs have two subject agreement inflectional paradigms, the objective and subjective conjugations, which reflect the presence or absence, roughly speaking, of a definite object.Footnote 2 The objective conjugation is generally used with definite objects as in (1), and the subjective conjugation is used with an indefinite object as in (2), and when there is no object, as in (3).

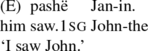

-

(1)

-

(2)

-

(3)

Person is another factor that affects the choice of conjugation. The subjective conjugation is used with first and second person objects, despite their definiteness:

-

(4)

A more complete distribution of the two conjugations is given in Sect. 2.

What is the grammatical role of the objective conjugation? According to the pronoun hypothesis, the objective conjugation verb inflection contains an incorporated object pronoun (Szamosi 1974; Den Dikken 2006). This means that the true objects of objective-conjugation verbs are pronouns, and free accusative-marked nominals are actually adjuncts, coindexed with the pronouns. Den Dikken (2006: 13) connects the pronoun hypothesis with the sensitivity of the objective conjugation to definiteness, noting that “object clitic doubling is generally known to impose definiteness …restrictions”. The set of nominals that can be clitic-doubled in certain dialects of Spanish, for example, is restricted to those with specific reference (Suñer 1988).

However, we argue below that the objective conjugation is sensitive not to the semantic definiteness or specificity of the object, but rather to what may be called its formal definiteness. The presence of the objective conjugation is conditioned by the presence of the formal feature [def +] on the object, where [def +] is determined by the object’s form, rather than its other syntactic, semantic, or pragmatic properties (Sect. 3.5). In this sense, the verb agrees with the object, and so we call this view the agreement marker hypothesis: the objective conjugation affixes are agreement markers, and free accusative nominals are the true objects of the verb (Bartos 2001; É. Kiss 2002).

We explain the sensitivity of the objective conjugation to the object’s formal definiteness in historical terms, based on the supposition that Hungarian objective conjugation affixes derive historically from incorporated object pronouns (Hajdú 1972). Cross-linguistically, the features of verbal agreement tend to be ϕ-features, because those are the features of the pronouns from which the agreement inflections derive historically (Bopp 1842; Givón 1976; Bresnan and Mchombo 1987: 747). The transition from incorporated pronoun to agreement marker has been characterized as a loss of the referentiality of the affix, leaving only the ϕ-features to be expressed (Bresnan and Mchombo 1987). But in addition, agreement affixes sometimes retain semantic attributes of pronouns such as a sensitivity to properties like definiteness and animacy (e.g. Givón 1976; Wald 1979), leading to various “finer transition states” on the path from pronoun to agreement (Bresnan 2001: 146). We suggest in Sect. 5 that in the precursor to the Hungarian objective conjugation, only third person pronouns were incorporated, and those pronouns were unmarked for number or lost their number distinctions, but retained their sensitivity to topicality. The consequent absence of ϕ-distinctions, coupled with the sensitivity to topicality, led the objective conjugation affixes to be reanalyzed as registering the formal definiteness of the object. This theory also explains why, as noted above, the objective conjugation markers are not used with first or second person objects.

After a brief description of the form and distribution of the verb conjugations (Sect. 2), we argue for the agreement marker hypothesis using evidence from null anaphora (Sects. 3.1–3.2), binding (Sect. 3.3), and extraction (Sect. 3.4). In Sect. 3.5, we provide further support for the agreement marker hypothesis by demonstrating that the use of the objective conjugation is insensitive to properties of the object that pronominal clitics and affixes have been shown to require of their associates: specificity (and the related notions of context dependence and principal filterhood), descriptive content, topicality (and the related notion of presuppositionality), anaphoricity, and DP-hood. Instead, the formal properties of the object, as specified in Sect. 4, determine the verb conjugation. The sensitivity to definiteness and person are explained in historical terms in Sect. 5. We conclude that although the Hungarian objective conjugation does not contain an incorporated pronoun, it bears a historical relationship to pronoun incorporation that explains its special distributional properties.

2 The subjective and objective conjugations

The two Hungarian subject agreement paradigms for present tense verbs are given in Table 1. Rows correspond to the grammatical person and number of the subject, columns indicate the conjugation (in for subjective and def for objective; see footnote 1), and the choice of variant within a cell depends on vowel harmony. For example, if the subject is first person singular, the present tense subjective conjugation of the verb is formed by attaching -ok, -ek, or -ök to the verb stem, depending on vowel harmony. In the objective paradigm, the corresponding ending is -om, -em, or -öm.

Generally, the objective conjugation is used with definite nominals in the accusative case,Footnote 3 and the subjective conjugation is used both with indefinite objects and when there is no object, as noted in the introduction. However, there are a few twists. The full list of forms that trigger the objective conjugation is as follows (based partially on Rounds 2001):

-

Proper names

-

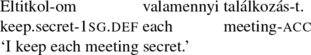

Definite determiners: a/az ‘the’, ez ‘this’, az ‘that’, melyik ‘which’, bármelyik ‘whichever’, hányadik ‘which number’, valamennyi ‘each’

-

Third person pronouns (overt or null); reflexive and reciprocal pronouns

-

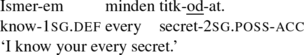

Possessive suffixes: -ad ‘your’, -ja ‘his/her/its’, etc.

-

Direct object clauses

Let us exemplify these in turn, leaving aside proper names.

Definite determiners

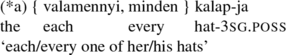

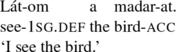

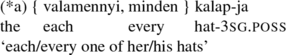

Example (1) showed a use of the objective conjugation where the object has the definite determiner a(z).Footnote 4 Other determiners that trigger the objective conjugation include valamennyi ‘each’Footnote 5 and melyik ‘which’:

-

(5)

-

(6)

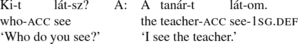

Third person pronouns

The objective conjugation is also used with third person pronoun objects, whether overt or null:

-

(7)

-

(8)

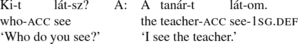

But the subjective conjugation is used with first and second person objects:

-

(9)

An exception is when the subject is first person singular and the object is second person; then a special ending -lak/-lek is used:

-

(10)

Reflexives and reciprocals

Another exception to the generalization that first and second person pronouns trigger the subjective conjugation is that reflexive pronouns trigger the objective conjugation, in all persons:

-

(11)

-

(12)

-

(13)

This is also the case for reciprocal pronouns:

-

(14)

Morphologically, reflexives in all person values can be analyzed as possessed common nouns, hence third person; -am and -ad are possessive suffixes. However, these reflexives cannot be third person forms because they are clearly in the first and second person for purposes of pronoun-antecedent agreement: Reflexives require an antecedent that matches in ϕ-features, and magam ‘myself’, for example, requires a first person antecedent.

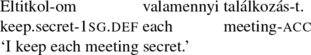

Possessive markers

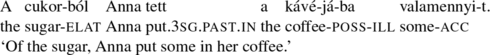

Possessed noun phrases are, in general, definite:

-

(15)

Even with minden ‘every’, a determiner that normally does not trigger the objective conjugation (cf. (16)), possessed nominals trigger the objective conjugation (cf. (17)) (Bartos 1997):

-

(16)

-

(17)

There are, however, nominals headed by possessed nouns that trigger the subjective conjugation, and this will be described more in Sect. 4.

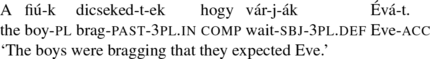

Direct object clauses

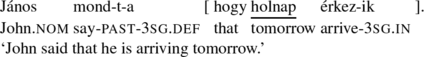

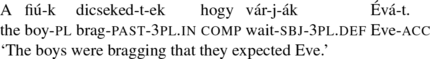

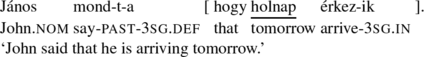

Finite complement clauses also trigger the objective conjugation (É. Kiss 2002):

-

(18)

-

(19)

These clauses are not overtly marked for case, so they are counterexamples to the generalization that accusative-marked elements trigger the objective conjugation. However, the clauses that trigger the objective conjugation alternate with accusative case-marked objects. The verbs mond ‘say’ and szeret ‘like’ assign accusative case to their object, as evidenced by the fact that DP objects overtly display accusative case.

-

(20)

-

(21)

In contrast, a verb like dicsekedik ‘brag’ assigns delative case, and does not appear in the objective conjugation with its clausal complementFootnote 6:

-

(22)

-

(23)

We refer to the clauses associated with accusative case as “direct object clauses”.

3 In favor of the agreement analysis

In this section, we compare the agreement marker analysis, given in (24), with the pronoun analysis, given in (25).

-

(24)

-

(25)

This section demonstrates that the pronoun hypothesis has quite a few problems that the agreement marker hypothesis does not suffer from. The problems lie in three areas: null anaphora, extraction islands, and the insensitivity of the use of the objective conjugation to any of the properties that govern the use of pronominal clitics. We conclude that the objective conjugation suffixes are agreement markers.

We use the term “agreement” in the sense of Steele (1978): “systematic covariance between a semantic or formal property of one element and a formal property of another” (Steele 1978: 610). In Hungarian, a formal property ([def +]) of the object covaries with a formal property (conjugation) of the verb.Footnote 7 We also mean “agreement” in contrast to “incorporated pronoun”. Thus, accusative-marked nominals are true objects, and the affix does not have the ability to refer. In Lexical Functional Grammar (LFG) terms, our thesis is that the objective conjugation affixes do not carry a pred feature.

Moreover, we find that Hungarian objective conjugation suffixes lack even those ‘quasi-pronominal’ properties of certain elements in other languages that may be seen as intermediate between incorporated pronouns and grammatical agreement markers. For example, in many languages a verbal inflection functions as an agreement marker when associated with a nominal argument, but as an incorporated pronoun in the absence of a nominal argument. Bresnan and Mchombo (1987) analyze the subject markers on Chicheŵa verbs in that way, and model them in the LFG framework as bearing an optional pred feature. Another instance of quasi-pronominals is found in the phenomenon of clitic doubling, where a clitic co-occurs with an argumental DP that agrees with it in ϕ-features and instantiates the same grammatical role (Jaeggli 1982; Borer 1984; Suñer 1988; Bresnan 2001; Torrego 1995b; Sportiche 1996; Uriagereka 1988, 1995; Anagnostopoulou 2003; Roberts 2010). Evidence for the argumental status of the doubled DP comes from prosody as well as the fact that it can occur where an adjunct cannot, for example as the subject of an embedded infinitive (Sportiche 1996). Analyses of clitic doubling vary, but it is generally agreed that clitics do not function as pronouns in such constructions, yet nonetheless retain some pronominal properties. First, they function as pronouns in the absence of a doubling nominal, like the Chicheŵa subject markers. Also, unlike agreement markers, they are distinguished by binding features, taking a reflexive form when doubling a reflexive analytic nominal. As we show below, Hungarian objective conjugation suffixes lack both of those ‘quasi-pronominal’ properties.

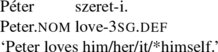

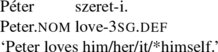

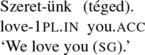

Finally, such clitics tend to be tense-invariant like pronouns, while true agreement affixes can vary in form across tenses (Nevins 2008). Nevins points out that agreement markers such as Dutch second person -t, Latin first person -am, Russian first person -u, and English third person -s have different allomorphs in different tenses and can be synthetic with the tense marker. In contrast, clitic pronouns like Romance le, Greek mu, Kashmiri s, Basque g, and Georgian v are tense-invariant, taking the same form across different tenses. Unlike clitics, the objective conjugation morpheme varies across tenses and moods. For example, the third person singular objective form of szeret ‘love’ is szeret- i ‘love-3sg.def’ in present tense, but szeret-t- e ‘love-past-3sg.def’ in past tense. The first person plural form is szeret jük in present tense, while the corresponding conditional form is szeretn énk. This variation across tenses is expected if objective conjugation suffixes are agreement markers.Footnote 8

In what follows, we provide further evidence for the agreement marker hypothesis based on the syntactic and semantic properties of the objective conjugation.

3.1 Null anaphora is independent of verb conjugation

Under the pronoun hypothesis, the true object of a verb in the objective conjugation is always an incorporated pronoun, so it is that incorporated pronoun that serves as the object in sentences like (26), in which the object is omitted.

-

(26)

At first blush, the pronoun hypothesis seems to explain why objects can be omitted: The incorporated pronoun is the actual object. However, null anaphora is not restricted to objects of objective conjugation verbs.Footnote 9 Recall that first and second person (non-reflexive) object pronouns do not trigger the objective conjugation. Such pronouns can be dropped:

-

(27)

-

(28)

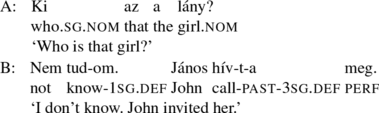

This suggests that null anaphora is not tied to verb morphology but is generally available in Hungarian. As such it is expected to be possible also for dative objects, which fail to trigger the objective conjugation. For example the verb tetszik ‘please’ selects a theme in nominative case and an experiencer in dative case. In the following example the experiencer argument of this verb has been dropped and receives a definite interpretation due to the context:

-

(29)

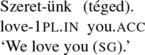

Note that the verb in (29) appears in the subjective conjugation, since it does not select an accusative object. The fact that datives can be dropped and receive a definite interpretation is also shown in (30). The verb in (30) appears in the objective conjugation because it selects an accusative object, in addition to the dative argument. Both objects are dropped in B’s reply:

-

(30)

Thus first person, second person, and dative objects, none of which trigger the objective conjugation on the verb, can be omitted with a definite interpretation. This shows that null anaphora is generally available in Hungarian, as in Japanese (Kameyama 1985) and Jiwarli (Austin and Bresnan 1996), even with arguments that are not marked on the verb at all.

3.2 Null anaphora and number

While the facts presented so far indicate that Hungarian has a general process of null anaphora, they are consistent with the language having, in addition, incorporated object pronouns just for the objective conjugation verbs. On that view, the grammar would provide two different ways to derive sentences like (26). But evidence from number casts serious doubt on that possibility. Regardless of whether the verb appears in the objective conjugation, as in (26), or the subjective conjugation, as in (27), (28), and (29), null anaphora is restricted to singulars. In null anaphora with third person objects, the implied object must have a singular antecedent:

-

(31)

The implied object cannot have a plural antecedent:

-

(32)

The restriction to singular objects applies to first and second person objects as well (adapted from Siewierska 1999: ex. (40)); plural first and second person objects cannot be dropped, even in contexts where the referent is easily recoverable:

-

(33)

-

(34)

Crucially, (overt) plural objects can trigger the objective conjugation:

-

(35)

Thus, on the pronoun hypothesis, the putative pronoun incorporated into the objective conjugation is unspecified for number. Therefore null anaphora with plurals should be possible. But as we saw in (32), it is not. This means that the pronominal object cannot be part of the objective conjugation, counter to the pronoun hypothesis.Footnote 10

On the agreement marker hypothesis, null anaphora is not licensed by the objective conjugation. We assume that it is introduced instead through an independent null anaphora rule that allows singular pronouns to be omitted in Hungarian.

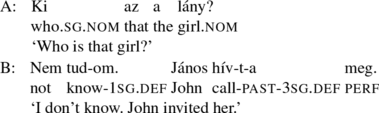

3.3 Pronoun binding

In null anaphora sentences like (36) (= (26) above), the object is disjoint in reference with the subject; (36) cannot mean Peter loves himself. But an overt reflexive object can co-occur with the objective conjugation, as in (37), and here, the object is of course interpreted as coreferential with the subject.

-

(36)

-

(37)

On the agreement marker hypothesis, the disjoint reference in (36) arises because the object is a pronoun that is subject to Condition B of the binding theory (cf. Chomsky 1986): The pronoun must be free in its domain. The relevant domain includes the subject in this sentence. Conversely, the coreference in (37) arises because the object is a reflexive anaphor subject to Condition A: The anaphor must be bound in its domain, which again includes the subject.

But on the pronoun hypothesis, the contrast between (36) and (37) is mysterious. In both sentences, the verb would contain a pronoun that is subject to Condition B, but (37) also contains a reflexive anaphor, which would be subject to Condition A. It is difficult to know what exactly the theory predicts in the face of such a conflict. Baker (1996) reasons that reflexive pronouns should not exist in a pronominal argument language, that is, a language where all true arguments are incorporated pronominals (Jelinek 1984). In fact, he uses the absence of reflexive anaphors in Mohawk to argue in favor of Jelinek’s pronominal argument hypothesis for that language. Briefly, Baker explains the absence of reflexive pronouns in Mohawk as follows: Assume Mohawk is a pronominal argument language. If, contrary to fact, Mohawk had a reflexive pronoun, then it would be an adjunct coindexed with its associated incorporated object pronoun (actually a null pro in an argument position, on his theory). The reflexive and the incorporated pronoun would be coindexed with each other, placing contradictory demands on the index assignment: The object pronoun would be subject to Condition B while the reflexive would be subject to Condition A, and the two conditions cannot be simultaneously satisfied in this configuration. Therefore Mohawk must lack reflexive pronouns.

Applying this logic to Hungarian under the pronoun hypothesis, reflexives would be incompatible with the presence of the incorporated pronoun, so they should trigger the subjective conjugation. But the facts are just the opposite. The objective conjugation is used not only with third person reflexives, as in (37), but also with first and second person reflexives, as we saw in (12) and (13) above, which is striking given that ordinary (non-reflexive) first and second person pronouns appear with the subjective conjugation.

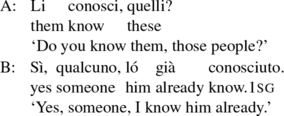

There is a possible answer to this argument, though. Legate (2002: 53) challenges Baker’s reasoning on the basis of connectivity effects with clitic left dislocation: “These effects include the dislocated element behaving for the purposes of Condition A and Condition B as though it occupies the associated argument position. Thus, a dislocated reflexive associated with the object may be bound by the subject, and a dislocated pronoun associated with the object may not be bound by the subject”. This is exemplified with the following Italian sentences, from Baker (1996: 105):

-

(38)

The claim here is that the clitic inherits the binding properties of its associate, so the Condition B requirement of a clitic pronoun would be voided in the presence of a reflexive associate.

But does example (38) really establish this claim? It is possible that the pronoun does not actually refer to Maria, but rather to her well-being, as a consideration. Consider the following contrast in English:

-

(39)

Although (39a) is not perfect, it is clearly much better than (39b). The demonstrative pronoun that does not refer to Maria, since it is inanimate. Because it is not coreferential with the subject, its presence does not violate Condition B. The example with the pronoun her is ungrammatical, presumably because it is still subject to Condition B, despite the presence of an associated reflexive phrase. Example (38) can be analyzed analogously. Indeed, Kayne (2008) argues for an analysis along these lines, according to which elements like ci contain demonstratives and behave deictically even in their non-locative use.

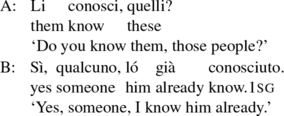

Ruwet (1990) shows that the analogous elements in French, en ‘of/about that’ and y ‘there’, can have reflexive interpretations even when the antecedent lies in a previous utterance (Ruwet’s ex. (91)):

-

(40)

The corresponding example in Italian is also grammatical:

-

(41)

According to Ruwet, a reflexive interpretation of en or y becomes possible when the context provides an antecedent, and the antecedent is presented “comme contenu de conscience vu de l’extérieur” (76), that is, when it can be construed as distinct from the agent whose point of view is being taken. This analysis is consistent with the view that they contain a distal demonstrative element, and, applied to Italian, would explain why (41) is grammatical. The theory that the reflexive interpretation of ci in (38) is due to a connectivity effect would not. So we are left without evidence that clitics inherit the binding properties of their associates. We conclude that example (37) really is problematic for the pronoun hypothesis.

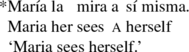

Example (37) also argues against a treatment of the objective conjugation as the kind of clitic doubling found in Spanish, where the clitic is not a pronoun when it doubles an object. In Spanish, a reflexive anaphor must be doubled by a reflexive clitic (Torrego 1995a: ex. (3)):

-

(42)

The non-reflexive clitic exemplified in (43) is not a possible substitute for the reflexive one:

-

(43)

-

(44)

Thus, even though la does not always function as a pronoun, it still retains certain binding features, preventing them from doubling anaphors (cf. Bresnan 2001: 146–147 on the retention of binding properties). The Hungarian objective conjugation, on the other hand, has no such restrictions, and is in this respect unlike the clitics that appear in clitic doubling constructions.

Note that the pronoun hypothesis cannot be saved by assuming that the objective conjugation suffixes are pronominals that are syncretic between reflexive and non-reflexive functions, like Western Romance first and second person clitics me and te, which double both reflexive and non-reflexive objects (as suggested by an anonymous reviewer). If that were the case, then we would expect a reflexive reading in the absence of a DP object, which, as shown in (26), is impossible. We are led to conclude that the objective conjugation affixes cannot be treated as pronouns, not even the kind of quasi-pronominal that appears in clitic doubling.

Summary of Sects. 3.1–3.3

Under the pronoun hypothesis, the object pronoun that occurs in sentences like (26) is present in the objective conjugation even when the sentence contains a free accusative nominal. This assumption cannot be maintained in light of the fact that the objective conjugation co-occurs with reflexive and plural objects; furthermore, null anaphora is generally available in Hungarian and not tied to the presence of inflection at all, let alone the objective conjugation.

3.4 Extraction

Further support for the agreement marker hypothesis comes from island effects. In the focus raising construction, a subconstituent of an embedded complement such as holnap ‘tomorrow’ in (45a) raises (potentially over multiple finite clause boundaries) to the matrix focus position, immediately preceding the verb, as in (45b) (É. Kiss 1990: exx. (6) and (7)).

-

(45)

Finite clauses can be doubled by an accusative object pronoun, azt, as in (46a). But when this pronoun is present, it is no longer possible to focus-raise holnap ‘tomorrow’ from the embedded clause, as in (46b) (É. Kiss 1990).Footnote 11

-

(46)

Under the agreement marker hypothesis, this contrast follows naturally from a difference in status of the embedded clause depending on whether or not azt is present. When azt is present, the embedded clause is an adjunct, coindexed with the pronoun, and when azt is absent, the clause is a direct object clause (as defined in Sect. 2). All the agreement marker hypothesis needs in order to account for this contrast is the assumption that this kind of extraction is better out of complement clauses than out of adjuncts, a generalization that is well established generally (cf. the Condition on Extraction Domains; Huang 1982) and well-documented in Hungarian (É. Kiss 2002). Extraction out of a direct object clause such as the complement of a bridge verb like mond ‘say’ is possible:

-

(47)

As shown in (48), extraction from a subordinate clause that is not a direct object clause, such as the complement to the non-bridge verb dicsekedik ‘brag’ (É. Kiss 2002), is ungrammatical.Footnote 12

-

(48)

On the pronoun hypothesis, the embedded clause is an adjunct, regardless of whether the object pronoun is absent as in (45) or present as in (46). (We suppose that on the pronoun hypothesis both azt and the embedded clause are adjuncts of some sort in sentences like (46a); this is perhaps another strange consequence of that hypothesis.) Thus, extraction should not be possible in either case. Alternatively, if it were hypothesized that extraction from adjuncts is allowed, then extraction should be possible in both cases. Under either assumption, the pronoun hypothesis fails to predict a contrast between (45b) and (46b).

3.5 Insensitivity to constraints on associates of pronominal clitics

Our final argument for the agreement marker hypothesis and against the pronoun hypothesis comprises several parts and may be summed up as follows: The Hungarian objective conjugation is not sensitive to any of the factors that have been argued to play a role in clitic pronoun constructions (both clitic left/right dislocation in Cinque’s 1990 sense and clitic doubling), namely specificity, descriptive content, topicality, and DP-hood. We argue furthermore that rather than being sensitive to semantics, the use of the objective conjugation is conditioned solely by the formal properties of the object. While agreement can in principle have interpretive correlates—as reflexes of movement triggered by the presence of agreement, for example—it need not do so. Clitic and affixal pronominals, on the other hand, always induce interpretive effects on their associates. Thus the lack of an interpretive effect proves a fortiori that the phenomenon in question is agreement.

3.5.1 Specificity

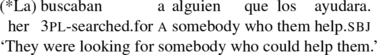

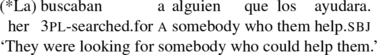

In clitic doubling constructions, the clitic generally requires its nominal associate to be specific. For example, a clitic in Porteño Spanish cannot double a non-specific direct object like alguien ‘somebody’ (example (6b) from Suñer 1988):

-

(49)

However, a formally indefinite NP associate like una mujer ‘a woman’ can be doubled, where the clitic induces a specific interpretation (example (7b) from Suñer 1988):

-

(50)

In Porteño Spanish, the possibility of clitic doubling is not predictable based on the form of the doubled object, but rather is based on the semantic property of specificity. Similar constraints have been observed for clitic doubling in Romanian (Dobrovie-Sorin 1990) and Greek (Anagnostopoulou 1994).Footnote 13

Suñer argues that Porteño Spanish clitics in doubling constructions lack the referentiality of pronouns, so they function essentially as agreement markers; Romanian and Greek are similar in that respect. Italian, on the other hand, is a language with clitics that always function as pronouns. Like the languages above, it also allows clitic doubles to be formally indefinite, as long as they are semantically specific. This is shown in the following example (adapted from Cinque 1990: 75):

-

(51)

In general, clitics impose semantic requirements on their associates, rather than formal ones.

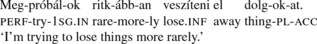

In Hungarian, formally indefinite noun phrases always trigger the subjective conjugation, regardless of whether or not they designate a specific individual. Here is an example in which the object is a specific indefinite:

-

(52)

The indefinite object egy görög énekest ‘a Greek singer’ must be specific, because the subsequent discourse identifies the singer by name.

But to establish with certainty that semantic specificity does not condition the choice of verb conjugation in Hungarian, we must indicate what exactly is meant by specificity. As Farkas (2002: 213) quips, “the notion of specificity in linguistics is notoriously non-specific”. Enç (1991) defines specificity as a kind of partitivity, or context-dependence. In Turkish, use of morphological accusative case marking is conditioned by specificity, and can disambiguate between a partitive and a non-partitive interpretation of NPs with cardinal determiners. In a context in which “Several children entered my room” has just been uttered, the accusative object in (53a) refers to two girls who are among the children mentioned, while the unmarked object in (53b) refers to two new girls:

-

(53)

On Enç’s analysis, a specific indefinite must establish a new discourse referent (in accordance with Heim’s (1982) non-familiarity condition on indefinites), but it is related to previously established referents. “In contrast, the discourse referent of a nonspecific indefinite is further required to be unrelated to previously established referents” (Enç 1991: 8). Gutiérrez-Rexach (2000) argues for a similar idea, namely that context dependence is a property that plays a role in the possibility of clitic doubling/left-dislocation. The idea, exemplified with Spanish, is that while todo hombre ‘every man’ is not context-dependent, todos los hombres ‘all the men’ is, because it requires a contextually given set of men. Likewise, algunos, which can be glossed partitively as ‘some of the’, is context dependent, while unos ‘some’ is context-independent. The context-dependent expressions can be clitic-doubled, but the context-independent ones cannot be.

Universal quantifiers are specific according to Enç (1991), because their meaning depends on a contextually given domain of quantification. Diesing (1992) develops this idea in terms of the existence presuppositions of ‘strong’ determiners in Milsark’s (1977) sense. As evidenced by (54), Hungarian minden ‘every’ is a strong determiner (Szabolcsi 1994, ex. (100)):

-

(54)

Since minden is a strong determiner, it counts as specific; indeed, Szabolcsi (1994) analyzes it as such. As noted above, minden phrases generally trigger the subjective conjugation:

-

(55)

Since the object in (55) introduces a universal quantifier, it is specific, yet the verb is in the subjective conjugation. Thus specificity does not make the right cut for Hungarian.Footnote 14

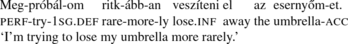

For another example, consider the following minimal pair from Bartos (2001), where the first example is in objective and the second in subjective conjugation (Bartos’s ex. (6)):

-

(56)

Based on the notions of specificity described above, the object in both examples in (56) should qualify as specific. This is corroborated by the intuitions of native Hungarian speaking linguists. According to Bartos (2001: 314), “there is absolutely no definiteness or specificity difference” between these two cases. Szabolcsi (1994: 210) agrees; regarding these examples she writes, “whereas the presence of the article is required in one of the examples and prohibited in the other, this makes no difference for interpretation”. The verb in the former example, but not the latter one, appears in the objective conjugation because its object is introduced by the definite article a(z). But the article does not affect the semantic interpretation in this example.

According to Enç’s (1991) understanding of specificity, partitives also count as specific. In Hungarian, there are phrases that are partitive, hence specific and context-dependent, which trigger the subjective conjugation (Chisarik 2002: 100, exx. (15), (16)):

-

(57)

-

(58)

Partitive constructions like this are also possible without an overt partitive phrase:

-

(59)

Just like its English gloss, this sentence requires a contextually salient set. The object is thus context-dependent in Gutiérrez-Rexach’s (2000) sense and specific in Enç’s (1991) sense, yet the verb is in the subjective conjugation. We conclude that specificity is not the determining factor for the objective conjugation in Hungarian.

3.5.2 Descriptive content

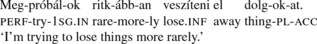

As just mentioned, (some) quantified noun phrases trigger the subjective conjugation in Hungarian. This was illustrated in example (55); another example is given in (60).

-

(60)

On the surface, this fact appears to support the pronoun hypothesis, because quantifiers like every, each, most, and no tend not to be doubled by clitics. This generalization is summarized by Rizzi (1986) as follows:

-

(61)

Rizzi’s condition is related to the unacceptability of Italian examples like the following, where a clitic doubles a quantified noun phrase in topic position:

-

(62)

-

(63)

On the pronoun hypothesis, objects of objective-conjugation verbs are in an A-bar position, binding an incorporated pronoun, so Rizzi’s condition correctly predicts the objective conjugation to be unacceptable with quantificational objects. This type of argument is used in support of the pronominal argument hypothesis for Mohawk by Baker (1996), who argues that Mohawk lacks truly quantificational NPs on exactly these grounds. (See also the discussion in Austin and Bresnan 1996: 237–238.)

If this is the right explanation for the use of the subjective conjugation with quantificational objects in Hungarian, then exceptions to Rizzi’s condition should also carry over to Hungarian. It has been observed, both by Rizzi himself and by Austin and Bresnan (1996), that pronouns locally A-bar bound by quantifiers improve when the quantifier in question is richer in descriptive content. Austin and Bresnan (1996: 238) give an example from English: Although (64a) is awkward, in accordance with Rizzi’s condition, (64b) is quite natural.

-

(64)

The same contrast holds in Italian:

-

(65)

If Rizzi’s condition were at work in Hungarian, one would expect the objective conjugation to improve when the quantificational object is richer in descriptive content. But in fact, there is no improvement. Regardless of the richness of descriptive content, it is necessary to use the subjective conjugation with this type of object:

-

(66)

This is what we would expect under the agreement marker hypothesis, under which the choice between subjective and objective conjugation is determined solely based on the form of the object.

3.5.3 Topicality

Kallulli (2000) argues that in Albanian and Greek, clitic doubling is sensitive to topicality, rather than specificity or definiteness. To illustrate, in example (67) from Albanian, the object must be interpreted as a discourse topic when the clitic is present, but when it is absent, the sentence can be uttered out of the blue.

-

(67)

Hungarian is discourse-configurational; the focus appears immediately preceding the verb and topics occur before the focus (É. Kiss 2002). This can be schematized in pseudo-regular expression notation as follows:

-

(68)

Furthermore, when an element occupies the focus position, the verbal prefix moves to the right of the verb. This makes it easy to test whether the Hungarian objective conjugation is sensitive to topicality, and it clearly is not. In (69), the verbal prefix meg is to the right of the verb, which shows that Jánost is in focus in (69).

-

(69)

Here, the verb is in the objective conjugation; hence, the verb can be in the objective conjugation even if the object is a focus rather than a topic. The objective conjugation can also be triggered by a noun phrase that is neither a focus nor a topic (É. Kiss 2002: 70):

-

(70)

Conversely, the verb can be in the subjective conjugation even if the object is a topic (É. Kiss 2002: 22):

-

(71)

The Hungarian objective conjugation is therefore not sensitive to topicality.

Example (69) also speaks against the idea that the objective conjugation is related to backgrounded/presupposed status. Gutiérrez-Rexach (2000) argues that in some Spanish clitic doubling constructions a Presuppositionality Constraint is operative, which requires that the doublee in a clitic doubling construction is presuppositional. As Gutiérrez-Rexach (2000: 330) says, “from the Presuppositionality Constraint it follows that focused noun phrases cannot be doubled”, with the assumption that presupposed elements belong to the background, “assuming the standard focus/background informational partition”. As we have shown above with example (69), focused noun phrases in Hungarian can co-occur with the objective conjugation. Thus presuppositionality is not the determining factor for Hungarian either.Footnote 15

3.5.4 DP-hood

So far we have established that the use of the objective conjugation is not conditioned by specificity, richness of descriptive content, or topicality. Another property that has been argued to be relevant to clitic doubling in various languages is DP-hood; Kallulli (2000) argues that this is a requirement for clitic doubling in Albanian and Greek. As it turns out, a predominant view in Hungarian linguistics on what determines whether or not an object triggers the objective conjugation, given by Bartos (2001), and further developed by É. Kiss (2000) and É. Kiss (2002: 49, 151–157), is that DP-hood is the crucial property. We will refer to this as the DP-hood hypothesis:

-

(72)

As Den Dikken (2006) points out, the DP-hood hypothesis and Kallulli’s analysis of clitic doubling in Albanian and Greek fit nicely together with his theory that the objective conjugation is a clitic. However, in this section we show that the DP-hood hypothesis is problematic, and argue that what determines the objective conjugation is not the phrasal category of the object.

Before making our arguments, let us describe the DP-hood hypothesis in more detail. On the DP-hood hypothesis, only DPs trigger the objective conjugation. Thus a definite noun phrase like a madár ‘the bird’ is a DP, whereas egy madár ‘a bird’ is a smaller phrase, which É. Kiss (2000, 2002) labels NumP:

-

(73)

É. Kiss (2002) proposes the following structure for the Hungarian noun phrase:

-

(74)

The various determiners are generated at different levels of this structure. The definite determiner a(z) ‘the’ is the only lexically specified member of the D category, hence it heads the outermost DP shell. The demonstratives e/eme/ezen ‘this’ and ama/azon ‘that’ are analyzed as ‘Dem’, heading DemP; the quantifiers like melyik ‘which’, valamennyi ‘each’, and bármelyik ‘any’ are ‘Q’; and members of the category Num include numerals like egy ‘one’ as well as minden ‘every’. This structure is motivated by the co-occurrence of determiners, most notably the co-occurrence of a(z) ‘the’ with determiners like valamennyi ‘each’, as in the following example:

-

(75)

According to the DP-hood hypothesis, nominals of category DP trigger the objective conjugation, while all smaller projections, whether DemP, QP, NumP, or NP, do not.

A prima facie problem for the DP-hood hypothesis is that many nominals lacking a(z) ‘the’ nonetheless trigger the objective conjugation. For example, valamennyi levél ‘each letter’ triggers the objective conjugation, even though valamennyi is not a D, since it can co-occur with one, as shown in (75). However, proponents of the DP-hood hypothesis have claimed that such phrases are DPs. The motivation for that claim is as follows.

Although a(z) ‘the’ may co-occur with other determiners, it cannot be adjacent to them. It is not possible to remove tőled kapott ‘from-you received’ from (76) to produce (77a); a(z) must be absent, as in (77b).

-

(76)

-

(77)

Loosely following Szabolcsi (1994: 210), we refer to this generalization as the Adjacent Determiner Constraint (where Det is a cover term for all non-D determiners):

-

(78)

To explain the absence of az in cases like (77b), Szabolcsi posits a rule of haplologyFootnote 16:

-

(79)

Through haplology, valamennyi levél ‘each letter’ is generated with the following structure, as a DP with a(z) deleted at PF:

-

(80)

Under these assumptions, this phrase is really a DP, despite containing only a lower-level determiner.Footnote 17

In an alternative to the haplology analysis, É. Kiss (2002) proposes that Dems and Qs project a DP, and move to Spec,DP, “presumably to check the [+definite] feature of the D head” (É. Kiss 2002: 154)—unless this movement is blocked by intervening material (such as tőled kapott ‘from-you received’ in (76)), in which case D is spelled out as az. Nums, such as két ‘two’, are compatible with az (cf. a két fiú ‘the two boys’), but do not move, presumably, according to É. Kiss, because they lack the ability to check the [+definite] feature. Thus nominals headed by Ds, Dems and Qs, which trigger the objective conjugation, all belong to the category DP. Nominals headed by Nums, which do not trigger the objective conjugation, are not DPs.

To summarize, the DP-hood hypothesis says that a verb has the objective conjugation if and only if it has a DP as its object (Bartos 2001: 320). The only lexical D is a(z) ‘the’, which heads a DP shell. Indefinites like két levél ‘two letters’ and egy madar ‘a bird’ lack a DP shell. Nominals like valamennyi levél ‘each letter’ are DPs: on one analysis they are headed by a silent a(z) ‘the’, deleted by a haplology rule (Szabolcsi 1994; Bartos 2001); on another analysis the determiner has moved to D (É. Kiss 2000, 2002). We argue against this hypothesis in the remainder of this section, and propose an alternative in Sect. 4.

Problem with DP-hood 1: First and second person objects

One minor problem with the DP-hood hypothesis comes from the fact that first and second person (non-reflexive) pronouns do not trigger the objective conjugation (the ‘person restriction’). Hence É. Kiss (2002: 171) proposes that first and second person pronouns are NumPs while third person pronouns are DPs, but offers no independent evidence that they belong to different categories. Bartos recognizes this problem and suggests an independent reason for the person restriction; in Sect. 5.2, we present our own view on this issue.

Problem with DP-hood 2: Indefinite determiners

A more serious problem with the DP-hood hypothesis is that it fails to capture contrasts among non-D determiners as to whether or not they trigger the objective conjugation. Some Dets trigger the objective conjugation, such as valamennyi, melyik, and bármelyik:

-

(81)

-

(82)

-

(83)

But others, such as minden ‘every’, trigger the subjective conjugation (Szabolcsi 1994: ex. (106)):

-

(84)

Let us focus on valamennyi ‘each’ and minden ‘every’. Both co-occur with a(z), as in (85), and cannot immediately follow it, as in (86):

-

(85)

-

(86)

Since minden is compatible with a(z), the phrase it introduces should be a DP. Under the haplology account, it would be possible to generate the string minden kalap through haplology:

-

(87)

This predicts that phrases like minden kalap should trigger the objective conjugation. On Bartos’s theory, a DP is projected whenever a(z) is present in the structure, silently or overtly. But as shown in (84), minden kalap triggers the subjective conjugation instead.

Similarly, under É. Kiss’s (2002) movement account, minden ‘every’ must project a DP since it co-occurs with a(z), and it should move to Spec,DP if no projection intervenes, so minden kalap should be a DP. However, since these nominals fail to trigger the objective conjugation, É. Kiss (2002: 156) analyzes minden as a Num. As such it is unable to check the [+definite] feature of the D head so it does not move. But as shown in (94) below, minden co-occurs with numerals, suggesting it is a Q, not a Num. Thus the quantifiers valamennyi and minden differ crucially in their definiteness specifications, but there is no evidence that any other phrase structural or syntactic distinction between them plays a role in the verb conjugation that they trigger.

In short, the presence of [def +] depends on which determiner appears, and cannot be reduced to the appearance of a(z), even under the assumption of an a(z) silenced by the haplology rule, or movement of the determiner when the D position is vacant. We conclude that the objective conjugation depends not on the phrasal category of the nominal but on whether the determiner bears the formal feature [def +]: valamennyi ‘each’ does, while minden ‘every’ does not. We spell out our analysis in more detail in Sect. 4.Footnote 18

Problem with DP-hood 3: Complement clauses

Finally, direct object clauses trigger the objective conjugation:

-

(88)

Such cases are prima facie counterexamples to the claim that only DPs trigger the objective conjugation, since these clauses are CPs rather than DPs.

To accommodate this data, Bartos (2001: 320) invokes Kenesei’s (1994) analysis of complement hogy clauses as adjuncts associated with an expletive DP pronoun. According to Kenesei’s analysis, (88) underlyingly contains an expletive pronoun azt, which is overt in (89).

-

(89)

According to Kenesei, azt is an expletive that forms a chain with the clause, and contributes case to the chain, while the clause, which cannot be assigned case, is assigned a θ-role. Equipped with both, the chain satisfies the Visibility Condition (Chomsky 1981), which requires that every chain have both case and a θ-role. As Bartos points out, Kenesei’s analysis is felicitous for the DP-hood hypothesis, because it removes a counterexample: the verbs are agreeing with an expletive pronoun, a DP, rather than a CP in sentences like (88).

But that analysis runs into trouble when it comes to extraction. Recall that when the object pronoun is (visibly) present, the finite clause becomes an island ((45b) and (46b), repeated here):

-

(90)

This contrast is puzzling if a pronoun, whether overt or null, always accompanies the clausal complement. To explain this, Kenesei (1994: 315) suggests that the extracted elements “are raised into the position of the expletive in the focus slot of the matrix clause”. When that landing site is filled by azt, extraction is blocked. This proposal sheds some light on the exceptional accusative case assigned to focus-raised nominals. As shown with example (91), the subject of an embedded clause is marked with accusative case when it is focus-raised into the matrix clause:

-

(91)

The focus-raised subject receives accusative case and transmits it to the clause so that the clause may be visible for θ-marking.

However, as Kenesei (1994: 318) himself points out, his analysis “has no natural explanation to offer for the properties of conjugation in case oblique arguments or adjuncts are moved… If an oblique noun phrase or an adjunct is raised, the matrix verb has objective conjugation, whether the phrase is definite or indefinite”. One example in this category is (90a) above: under Kenesei’s analysis, holnap has raised into the expletive position and receives accusative case, but it is not clear how an adverb could receive case.

Moreover, when a focus-raised adjunct is indefinite, the matrix verb remains in the objective conjugation:

-

(92)

Kenesei’s analysis requires that the instrumental case-marked, focussed oblique noun phrase must invisibly receive accusative case from the matrix verb. But then the verb should be in the subjective conjugation, reflecting the indefiniteness of the raised item; instead in appears in the objective. We suggest instead that the verb agrees with the clause in (92), and bears the objective conjugation because hogy-marked CPs are formally definite. This is not compatible with the DP-hood hypothesis.Footnote 19

To summarize Sect. 3.5.4, there are two major problems with the DP-hood hypothesis: (i) it cannot account for differences among determiners as to whether they trigger the objective conjugation; (ii) clausal complements trigger the objective conjugation, yet are CPs rather than DPs.

Conclusion

We conclude Sect. 3 in favor of the agreement marker hypothesis: the Hungarian objective conjugation affixes are agreement markers. The pronoun hypothesis is untenable in light of the following facts:

-

The objective conjugation co-occurs with object reflexive pronouns and plural objects.

-

The presence of a correlative object pronoun creates an island for extraction.

-

The objective conjugation is not sensitive to properties clitics require of their associates: specificity, descriptive content, topicality, and DP-hood.

The notion that Hungarian verb-object agreement is a kind of clitic doubling, where the clitic agrees with its associated nominal but is not referential, is not tenable either, since reflexive pronouns may co-occur with the objective conjugation. The fact that the objective conjugation is not sensitive to the properties that are relevant for clitic doubling also speaks against a clitic doubling analysis. The conditions on object agreement are not semantic or pragmatic, but merely formal, contrary to what one would expect on the pronoun analysis. (Whether the agreement marker analysis is more appropriate than the clitic analysis for the -l of the first person singular subject/second person object ending -lak/-lek remains an open question.)

We propose to analyze the objective conjugation according to the agreement marker analysis given in (24), repeated as (93):

-

(93)

We turn next to a more thorough analysis.

4 The grammar of def

In this section, we specify a grammar that determines, for a given accusative complement of a Hungarian verb, whether it triggers the objective conjugation on that verb. We employ a boolean feature def: Lexical items may be specified [def +] or [def −]; or they can be unmarked for def. If a verb takes an accusative complement phrase bearing the [def +] specification, then that verb appears in the objective conjugation; otherwise it appears in the subjective conjugation. So the main question we address here is how the def feature of a phrase is determined as a function of its constituents.

The objective conjugation triggers listed in Sect. 2 include proper names, definite determiners (a/az ‘the’, ez ‘this’, az ‘that’, melyik ‘which’, bármelyik ‘whichever’, hányadik ‘which number’, valamennyi ‘each’, etc.), third person ordinary pronouns, reflexive and reciprocal pronouns of all persons, possessive suffixes (-ad ‘your’, -ja ‘his/her/its’, etc.), and the complementizer hogy ‘that’. All such lexical items are specified [def +].

Now we specify how the def feature is passed up from the lexical items to the nodes that dominate them. Recall that valamennyi ‘each’ triggers the objective conjugation but minden ‘every’ does not. In Sect. 3.5.4 we concluded that the quantifiers minden ‘every’ and valamennyi ‘each’ belong to the same part-of-speech category; in particular, we claim that minden, like valamennyi, is of category Q. Independent support for this claim comes from the fact that minden can co-occur with numerals, which are of category Num:

-

(94)

The reason that valamennyi triggers the objective conjugation but minden does not is that valamennyi is lexically specified as [def +], whereas minden is not:

-

(95)

The [def +] specification on valamennyi is passed up to the QP node from its head Q, and when this QP is the accusative complement of a verb it triggers the objective conjugation on that verb.

The subjective conjugation is used whenever the accusative complement lacks a [def +] specification, hence minden, which is unmarked for def, appears with a subjective conjugation verb as shown in (96).

-

(96)

As noted already, the subjective conjugation verb requires the absence of a [def +] accusative object, an assumption that is independently motivated by the fact that intransitive verbs appear in the subjective conjugation.

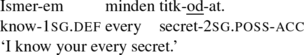

So far we have seen the def feature passed up from its head daughter. But if the head daughter is unspecified for def while the complement daughter is so specified, then the def feature is passed up from the complement daughter to its extended projection instead. Possessive suffixes provide one example of this.

Possessed nominals in Hungarian are generally definite, with some interesting exceptions to be noted. When a noun is possessed, it bears a suffix indicating the presence of a possessor, and the possessor can either be null, non-case-marked, or marked with dative case.Footnote 20 Even in the absence of an overt possessor, a nominal with a possessive suffix, such as titk- od -at ‘secret-2sg.poss-acc’ (‘your secret’), is definite, so we assign the feature [def +] to suffixes like the second person singular suffix -od. When such a nominal is introduced by minden it still triggers the objective conjugation:

-

(97)

As a rule, if the head is unspecified for def, then the phrase inherits its def feature from the complement instead. In this case, the Q minden is unspecified for def while the possessive-marked noun is [def +], so the phrase as a whole is [def +]. (We analyze such quantified nominals as QPs, but it would not affect our analysis if a DP were projected above the QP. With regard to quantifiers such as minden and valamennyi, the only claim we are committed to is that the contrast in definiteness between them stems from the lexical specification on the determiner, rather than a difference in syntactic category.)

Nouns with possessive suffixes do not always trigger the objective conjugation. With the indefinite determiner néhány ‘some’, either objective or subjective conjugation is possible:

-

(98)

-

(99)

Apparently, the inherent indefiniteness of determiners like néhány ‘some’ can take precedence over the inherent definiteness of possession. This can be modelled under the assumption that néhány is optionally [def −]. Since it appears on the head daughter, this feature, when specified, takes priority over the [def +] feature contributed by the possessive suffix, as depicted on the left in (100). More generally, any feature clashes between daughters are resolved in favor of the head daughter.

-

(100)

When néhány lacks any def feature specification, the [def +] specification on the possessed nominal survives, as depicted on the right in (100). This accounts for the two options in (98).Footnote 21

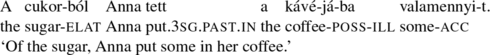

Next consider phrasal possessors, beginning with dative possessors. Nominals introduced by dative possessors are [def +]: They are always definite. This is the case even when the possessor and the possessum are both indefinite, as illustrated by the following example (É. Kiss 2002: 173, ex. (50)):

-

(101)

The NumP két dolgozat-át ‘two papers’ is indefinite, as is the dative possessor egy diáknak ‘one student’. Yet the noun phrase as a whole is definite, as shown by the fact that it triggers the objective conjugation on the verb. Under the present proposal, it is the possessive construction itself that is responsible for the definiteness of the phrase. In particular, a specifier position is earmarked for dative possessors, and the projection and filling of that position renders the possessed nominal as whole definite.

Support for the view that dative possessors have a dedicated position, rather than being adjoined, for example, comes from the fact that the pre-article position is not available to other case-marked arguments of the noun. This is illustrated in the following exampleFootnote 22:

-

(102)

If adjunction were available for this position, it would be available for other arguments, but it is not. Also, unlike other arguments, dative possessors cannot appear to the right of the noun, not even in titles, where other case-marked arguments can generally appearFootnote 23:

-

(103)

-

(104)

Furthermore, they cannot appear between the definite article a(z) and the noun, unlike other arguments of nouns:

-

(105)

-

(106)

These differences between dative possessors and other case-marked arguments of nouns support the assumption that there is a dedicated prenominal position for the dative possessor.Footnote 24

Where exactly is this dedicated possessor position? According to Szabolcsi’s (1994) theory, the dative possessor is in Spec,DP, but É. Kiss (2000) points out that this does not make room for a demonstrative intervening between the dative possessor and a definite article as in (107):

-

(107)

One solution that does not rely on adjunction is to posit that the possessor is the specifier of a functional projection above DP; call it PossP.Footnote 25

-

(108)

The head Poss is inherently specified [def +], and this feature is passed up to its maximal projection PossP, even if the complement is [def −]. Example (101) would thus be analyzed as in (109).

-

(109)

Even though both the specifier and the complement of PossP are indefinite in this example, the PossP is definite because it inherits [def +] from its head Poss. (This PossP shell must be projected in order to provide a specifier position for the dative possessor, and it cannot be projected unless that position is filled, for reasons of projectional economy (cf. Grimshaw 1991).)

Hungarian also allows possessors in nominative case. Like the nominals with dative possessors, nominals with nominative possessors are definite, and there appears to be a dedicated possessor position for them as well. The possessive construction itself could be the reason for the definiteness of these nominals, as with the dative possessors. Alternatively, the definiteness of nominals with nominative possessors could be coming from the determiner a(z). Although not all nominative possessors co-occur with a(z) (cf. (110a)), pronominal nominative possessors do, as in (110b), and personal names have this option, as in (110c) (É. Kiss 2002 ex. (14)):

-

(110)

Based on this data, it seems possible that a(z) ‘the’ is occasionally deleted before a nominative possessor, and that the article, whether overt or null, is the cause of the definiteness in such cases. We leave it open whether the definiteness of such nominals results from this null a(z) ‘the’, or the nominative possessor construction. (However, for reasons already given in Sect. 3.5.4 above, it is implausible that a silent a(z) is also responsible for the definiteness of nominals like valamennyi titok ‘each secret’. This we attribute instead to the [def +] feature on valamennyi; cf. (95).)

To recapitulate the details of our analysis, the formal definiteness of a nominal or complement clause is determined primarily by lexical feature specifications contributed by morphemes such as definite determiners, third person pronouns, reflexive and reciprocal pronouns of all person values, proper names, finite complementizers, and possessive suffixes. These features are passed up the tree from heads to their phrasal projections, and from complements to their extended projections, with heads taking precedence over complements whenever the feature values would otherwise clash. The phrasal category of the nominal does not determine the verb conjugation. These assumptions account for a number of facts: that determiners with the same syntactic distribution can differ in definiteness, that possessed nominals generally behave as definite, even with some determiners that otherwise do not trigger the objective conjugation, that possessed nominals are optionally definite with some determiners, and that the presence of an overt dative or nominative possessor makes a noun phrase behave as definite.Footnote 26

Our more general theoretical claim regarding the circumstances under which a nominal counts as definite may be summarized as follows. The forms triggering the objective conjugation may in principle belong to a diverse range of syntactic categories. With respect to the synchronic grammar of Hungarian, what these elements have in common is simply the formal feature [def +]. (Their diachronic commonalities are treated in the next section.) These various definiteness-inducing elements appear at different positions within the structure of the nominal, from items high in the nominal’s phrase structure such as the definite determiner a(z), to items low in the structure such as possessive suffixes on nouns.

Stepping back to review our other conclusions regarding the synchronic syntax of Hungarian, we showed that the objective conjugation is a grammatical agreement affix triggered by a [def +] object in its accusative case domain. It is not an incorporated pronoun. The definiteness feature of an object that triggers the objective conjugation on a verb is a formal feature, not a semantic one. However, we do not consider it an accident that the distribution of this feature across the lexicon of Hungarian can be predicted fairly well based on semantic definiteness. In the following section, we will argue that the close relationship of the objective conjugation to both semantic definiteness and grammatical person is a relic of an earlier grammatical system with object pronoun incorporation.

5 Pronominal origins of the objective conjugation

A question that remains is why formal definiteness is the property of the object that is relevant for the use of the objective conjugation. Agreement is normally in ϕ-features, not definiteness. Another remaining mystery is why first and second person pronouns fail to trigger the objective conjugation, given that first and second person are just as definite as third person. In this section, we show that these two birds can be killed with one stone: by placing the Hungarian objective conjugation in a historical perspective. While the origin of the two subject-verb agreement paradigms in Hungarian is a vexing question for which a great number of hypotheses have been put forth, it is generally agreed that the objective conjugation suffixes descend from pronominal object incorporation. We suggest that the properties of the definite conjugation may derive from restrictions on the incorporation of pronouns at that earlier stage.

At the broadest level, theories of the origin of the objective conjugation can be grouped into those that posit a three-morpheme origin for the objective conjugation, of the form V-OM-SM (Hunfalvy 1862; Budenz 1890; Honti 1996, 1998; Rédei 1989), and those that posit a two-morpheme origin of the form V-SM, where SM is distinct from the subject marker found in the subjective conjugation (Abaffy 1991; Thomsen 1912; Rédei 1989, 1962; Melich 1913; Lommel 1998; Havas 2004). Despite disagreement on that point, there is a consensus that the -ja found in the third person singular of the objective conjugation can be traced back to a third person object pronoun, which Hajdú (1972) reconstructs as *se. This glide appears in most of the objective conjugation endings, as shown in Table 2, where it is highlighted. In the following sections, we will use this assumption to explain the sensitivity of the objective conjugation to definiteness and person.

5.1 Definiteness

The transition from pronoun to agreement marker is often characterized as a loss of the referential property of the affix, leaving only the ϕ-features to be expressed (Bopp 1842; Givón 1976; Bresnan and Mchombo 1987). After the referential property is lost, other pronoun properties can be retained, leading to various “finer transition states” on the path from pronoun to agreement (Bresnan 2001: 146). For example, Bresnan (2001: 146–147) suggests that anaphoric binding features (e.g., being subject to Condition B) are retained by agreement markers in Kichaga (Bresnan and Moshi 1990: 151–152), and certain dialects of Spanish (Andrews 1990: 539–542). Suñer (1988) argues that the clitics in Porteño Spanish are non-pronominal affixes, but retain the sensitivity to specificity that pronouns have. Similarly, the presence of agreement markers is conditioned by specificity or animacy in some Bantu languages (Givón 1976; Wald 1979). In these languages, ϕ-features are retained along with their sensitivity to specificity or animacy. In Hungarian, we suggest that feature loss occurred in the opposite order: ϕ-features were lost, but sensitivity to specificity, definiteness, or topicality was retained, and this property was reanalyzed as formal definiteness.

Evidence for the idea that definiteness-sensitivity in Hungarian is grammaticalized topicality-sensitivity comes from Northern Ostyak (Uralic). As in Hungarian, an objective conjugation is used for certain types of objects in Northern Ostyak, and a subjective conjugation is used elsewhere. The use of the objective conjugation in this language is conditioned by a certain form of topicality (Nikolaeva 1999, 2001). Nikolaeva (1999) shows that a nominal triggers the objective conjugation only when it is outside the VP, in which case it functions as a ‘secondary topic’ (a topic that is not the most prominent one).

Despite being outside the VP, the objects that trigger the objective conjugation in Northern Ostyak are still genuine arguments of the verb, as Nikolaeva (1999) shows. Therefore, the objective conjugation does not contain an incorporated pronoun, but rather an object agreement marker that is restricted to objects that are (secondary) topics. However, Northern Ostyak’s system can be understood as deriving from a system where free object nominals are topics anaphorically linked to the bound pronominal argument when it appears on the verb. On this view, Northern Ostyak object marking retains a topicality restriction from a stage at which the object marker was an incorporated pronoun.

This supports the view, also put forth by Marcantonio (1985) on the basis of data from Old Hungarian, that the objective conjugation’s sensitivity to definiteness in Hungarian emerged through grammaticalization of this topicality condition, which itself is retained from an earlier stage at which object pronouns were incorporated into the verb. This kind of grammaticalization is quite easy to imagine given the strong correlation between topicality and definiteness (Givón 1976).

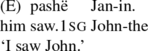

5.2 Person

Recall that although third person pronouns trigger the objective conjugation, as in (111), first and second person pronouns trigger the subjective conjugation, as in (112):

-

(111)

-

(112)

This is somewhat mysterious under the view that verbs agree with their objects in definiteness, because first and second person would be expected to count as definite.

Explanations for the person restriction in Hungarian have been given by Bartos (2001: 322), É. Kiss (2005), Comrie (1977: 10), Dalrymple and Nikolaeva (2011), Den Dikken (2006), and Coppock and Wechsler (2010). Here, following Coppock and Wechsler (2010), we speculate that only third person pronouns were incorporated into the verb, and the restriction of the objective conjugation to third person is a historical relic of the third person feature on the pronoun from which it derives.

This idea explains why third person restrictions with respect to object agreement would be found not only with object definiteness/topicality agreement, but also with object ϕ-feature agreement. In Ob-Ugrian languages (Honti 1984; Kálman 1965) and Samoyedic languages (Hajdú 1968), object number but not person is distinguished on the verb. The conjugations for Ostyak (also called ‘Khanty’; Ob-Ugrian) are given in Table 3 (Honti 1984: 107, taken from Kortvély 2005). In Northern Ostyak (also called Western Ostyak), number is marked for objects of all persons, but in Eastern Ostyak, as well as in Samoyedic languages (Enets, Nenets, etc.), only third person objects trigger an objective conjugation. According to Gulya’s (1966: 115) grammar of Eastern Ostyak, “The definite [i.e. objective] conjugation … expresses not only a definite object of the third person, but its number as well” (emphasis added). Similarly, in the Samoyedic languages (Nenets, Enet, Selkup, and Nganasan) verbs agree with the object in number when they agree, but first and second person pronouns never trigger agreement, just as in Hungarian (Irina Nikolaeva, p.c.; Honti 1984; Kálman 1965, cited in Nikolaeva 1999; Kortvély 2005).

We suggest that Hungarian derives from a language in which object marking is limited to third person but object number is expressed by the object marker, as in Eastern Ostyak or Samoyedic. On this view, Hungarian simplified the object agreement system by eliminating number distinctions in third person. In other words, the Hungarian system arose through a conflation of the number distinctions, leaving only one ϕ-feature to be expressed by object agreement, namely (third) person. (The Northern Ostyak system, in which number marking applies to objects of all persons, would also derive from the Eastern Ostyak/Samoyedic-like system, simplifying it in a different way: by eliminating the restriction to third person on each of the object markers, retaining the number specification. This simplification amounts to a spread from third person to all persons. See Coppock and Wechsler 2010.)

Hungarian is quite distantly related to Samoyedic; the Samoyedic family is not Finno-Ugric, but part of a separate branch of the Uralic languages. Yet the notion that Hungarian’s objective conjugation is closely related to Samoyedic’s gains support from historical studies of the Uralic languages. Helimski (1982) reconstructs the Hungarian and Samoyedic objective paradigms to a shared areal feature, pointing to such facts as the -k ending in the first person singular present tense subjective paradigm, which is present in both Hungarian and in Samoyedic languages such as Selkup.

Although we see the person restriction as the historical relic of a third person incorporated pronoun, we do not want to go so far as to analyze the modern-day objective conjugation as person agreement. The objective conjugation is not completely restricted to third person in modern Hungarian. First and second person reflexive pronouns trigger the subjective conjugation, as shown above in (12) and (13). Therefore it cannot be maintained that the objective conjugation verb requires a third person object. As mentioned in Sect. 2, first and second person reflexive pronouns can be analyzed as third person morphologically, but they do not function as third person pronouns for the purposes of pronoun agreement; they require an antecedent that matches their first or second person feature. Thus, it must be assumed that all reflexive pronouns count as [def +], along with third person and possessed forms. We suggest that a reanalysis along these lines took place, so that ϕ-features were completely lost from the original pronoun, leaving an unusual kind of ‘formal definiteness’ in their place. Although this complicates the distribution of [def +], it simplifies the grammar in another respect, by making the verb sensitive to only one factor (the def feature) rather than two (def and person).Footnote 27

We suggest an analogous explanation for the special -lak/-lek form that is used with second person objects and first person singular subjects. As scholars including É. Kiss (2005) and Den Dikken (2006) have discussed, it appears to have the form of a second person marker -l (which shows up as a second person singular subject ending on some verbs), followed by the first person singular subject ending -ok/-ek/-ök. This lends credence to the idea that at some stage in the development of Hungarian, there was a productive V+OM+SM template, where OM could be instantiated not only by third person object markers, but also second person ones. Just as the -j of the objective conjugation derives historically from a third person incorporated pronoun, we find it plausible that the -l of -lak/-lek, has its historical origin in a second person incorporated pronoun—and perhaps remains a second person pronoun to this day.Footnote 28

6 Conclusion

We have argued that the Hungarian objective conjugation should be analyzed as agreement conditioned by the presence of the formal feature [def +], and that free accusative nominals that co-occur with the objective conjugation are arguments, not adjuncts. Evidence for this hypothesis comes from the objective conjugation’s co-occurrence with reflexive pronouns and plural objects, extraction across objective-conjugation verbs, and the fact that it is not sensitive to any of the properties that pronominal or quasi-pronominal clitics have been observed to require of their associates: specificity, descriptive content, topicality, anaphoricity and DP-hood.

We have also argued that whether or not an element bears [def +] depends primarily on lexical specifications, and is only partly syntactically determined; the dative possessor construction is associated with a [def +] head, and heads take precedence over their complements within the same extended functional projection for the passing up of definiteness features. The set of items that bear [def +] consists mostly of semantically definite DPs like proper names and definite descriptions, but it also contains non-referential quantificational expressions that are possessed, and CPs. Notably absent from this set are first and second person non-reflexive pronouns. Nevertheless, it is not an accident that whether or not a form triggers the objective conjugation can be predicted fairly well based on semantic definiteness and grammatical person. These are sensitivities that Hungarian has inherited from a system with object pronoun incorporation.

The objective conjugation is an unusual example of pronoun detritus, because nothing remains of the earlier pronoun except a sensitivity to definiteness. It does not express any ϕ-features—not even third person, since first and second person reflexives trigger the objective conjugation. The provenance of this phenomenon may bespeak a richer array of historical possibilities for the feature loss that leads from pronoun to agreement: when ϕ-features on a pronoun-derived agreement marker are lost, sensitivities to factors such as definiteness and animacy can survive. This can result in a pronoun-derived agreement marker that signals definiteness, rather than ϕ-features.

Notes