Abstract

Cutaneous mucormycosis caused by Mucor irregularis (M. irregularis) is a rare condition that typically occurs in immunocompetent patients. Herein, we describe an immunocompromised patient with cutaneous M. irregularis infection who was successfully treated with debridement combined with vacuum assisted closure (VAC) negative pressure technique and split-thickness skin grafting. We present this case owing to its complexity and rarity and the successful treatment with surgical therapy. A 58-year-old man presented to our hospital with a history of skin ulcers and eschar on the right lower leg since two months. He had been receiving methylprednisolone therapy for bullous pemphigoid that occurred five months prior to the present lesions. Histopathological examination of a right leg lesion showed broad, branching hyphae in the dermis. Fungal culture and subsequent molecular cytogenetic analysis identified the pathogen as M. irregularis. After admission, methylprednisolone was gradually tapered and systemic treatment with amphotericin B (total dose 615 mg) initiated along with others supportive therapies. However, the ulcers showed no improvement, and amphotericin B had to be discontinued owing to development of renal dysfunction. After extensive surgical debridement combined with VAC and skin grafting, his skin ulcers were healed; subsequent fungal cultures of the lesions were negative. The patient exhibited no signs of recurrence at 36-month follow-up. Twenty-six cases with M. irregularis-associated cutaneous mucormycosis in literature were reviewed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cutaneous mucormycosis caused by Mucor irregularis (M. irregularis) formerly known as Rhizomucor variabilis [1], is less common in immunocompromised patients and has been rarely reported clinically. The condition has mainly been treated with drugs [2,3,4,5,6], and is inherently resistant to most widely used antifungal medicines [7]. In this study, we report an immunocompromised patient who developed M. irregularis-induced cutaneous mucormycosis. This patient was successfully treated with debridement combined with vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) negative pressure technique and skin grafting. We also review the relevant literature.

Case

A 58-year-old man presented to our hospital with a history of skin ulcers and eschar on his right lower leg since two months. Five months back he was diagnosed with bullous pemphigoid at a local hospital; his symptoms resolved after glucocorticoid therapy. Two months back he developed new haemorrhagic bullae and ulcers with eschar on his lower right leg; histopathological examination of biopsy specimen confirmed the diagnosis of pemphigoid combined with fungal infection. After approximately two weeks of treatment with glucocorticoid in combination with itraconazole (0.2 g twice daily) and terbinafine (0.25 g/day), the rashes showed little improvement. He was subsequently referred to our hospital. This patient had no history of fever; however, he experienced occasional expectoration since the onset of disease. He had a long history of smoking and pulmonary emphysema. There was no relevant family history or history of any specific contact or trauma.

Dermatological examination revealed pitting edema in both legs and multiple creeping ulcers of varying sizes over the lower right anterior leg tibia. The largest ulcer was approximately 5 cm × 10 cm in size; the ulcers extended to deep fascia, muscle, and even shinbone. Some ulcers exhibited surface granulation tissue and a small amount of purulent discharge, while others had black eschar with surrounding inflammatory erythema. The limbs and torso showed scattered pigment macules and petechiae without blisters (Fig. 1a). No other abnormality was noted on general examination. Results of pertinent laboratory investigations were as follows: white blood cell count, 12.81 × 109/L (normal reference range, 4.00–10.00); blood biochemistry results were: serum alanine transaminase, 78 U/L (normal reference range, 1–40); gamma glutamyl transferase, 66 U/L (2–50); albumin, 29 g/L (35–50); blood glucose, 4.9 mmol/L (2.9–6.0); glycosylated hemoglobin, 8.80% (4.4–6.0); T-cell subgroups were: CD4+ 33.2% (32.0–46.0) and CD8+ 21.7% (18.0–32.0); serum cytomegalovirus-IgM 0.86(≤ 0.6) and IgG 250.00 IU/mL (0.00–15.00); cytomegalovirus DNA, 1.7 × 104 copies/mL (≤ 500.00); serum ferritin, 1451.43 µg/L (16.4–323.00).

a Photograph showing ulcerative plaques over right anterior tibia with central necrotizing eschar. b The ulcers enlarged after 3-week treatment with amphotericin B, with persistent development of black eschar. c Photograph of vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) negative pressure technique on the lesion after skin debridement. d Photograph showing formation of fresh granulation tissue after skin debridement and ensuing vacuum-sealed drainage. e Appearance at 3rd week after debridement combined with VAC and skin grafting. f No recurrence of rash is observed on the right anterior tibia at 3-month follow-up

No abnormalities were found in any of the following tests: urine and stool routine tests, blood lipids, renal function, HIV antibody screening, serum level of complement, multi-tumor markers, procalcitonin, serum detection for fungal (1,3)-β-D-glucan, antigens of Aspergillus and Cryptococcus, sputum culture or abdominal ultrasonography. Arteriovenous ultrasound in the lower extremity showed multiple segmental occlusions with 100% stenos in the right anterior tibia artery. There were multiple plaques with < 50% stenos in the arteries of both lower extremities; in addition, bilateral deep vein valve insufficiency with grade III venous reflux was observed. Chest computed tomography showed pneumonia in both lungs. Histopathological examination of skin lesions showed focal cutaneous ulceration (Fig. 2a), accompanied by multifocal necrosis and neutrophil infiltration with broad hyphae in the subcutaneous adipose tissues (Fig. 2b). Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) and Grocott methenamine silver staining confirmed the presence of hyaline and septate hyphae with wide-angled branching in the dermis (Fig. 2c, d). On immunofluorescence staining, IgM, and IgA were negative, while C3 and IgG were positive in the dermal–epidermal junction. Direct potassium hydroxide examination of lesion crusts showed broad, aseptate hyphae with right-angle branches (Fig. 3a). Skin tissue specimens cultured on Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) at 28 °C yielded cotton-like, light yellow colonies on day 3; aerial mycelia were observed on the surface of the colonies on day 5 (Fig. 3b). Microscopic examination of slide cultures revealed chlamydospores, sporangiophores with abundant rhizoids and terminal globose sporangium containing round spores without apophyses (Fig. 3c, d). The consensus sequence showed 99% identity (identities of nucleotides 596/597) with M. irregularis strain 4756 (GenBank accession no. HM639969.1). Diagnosis of primary chronic cutaneous mucormycosis caused by M. irregularis was confirmed.

a Histopathological examination of cutaneous ulcers shows dense dermal infiltration of giant cells and multifocal fat necrosis (hematoxylin–eosin [HE], ×4). b Wide and large septate hyphae (arrows) are seen in the dermis and subcutaneous fat tissue (HE, ×40). c, d Broad septate hyphae are seen (c Periodic acid-Schiff, × 20; d Silver stain Grocott methenamine silver stain, ×20)

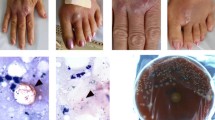

a Direct smear of tissue specimen showing broad and aseptate hyphae with right-angle branches (×40 magnification). b SDA cultured for five days at 28 °C, showing fluffy, light yellow colonies. c Light microscopy of fungal culture showing spherical sporangia and no apophysis (lactophenol cotton blue stain, ×40 magnification). d Light microscopy of fungal culture showing the chlamydospores (×40 magnification)

Antifungal susceptibility test was carried out using Sensititre YeastOne (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Sensititre YeastOne is a colorimetric MIC susceptibility test plate which contains nine antifungal drugs. The 48-h minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of M. irregularis isolated from skin lesions at 28 °C showed low MIC of amphotericin B (0.5 μg/mL), and high MIC of voriconazole (> 8 μg/mL), itraconazole (> 16 μg/mL), posaconazole (> 8 μg/mL), 5-flucytosine (> 64 μg/mL), and micafungin (> 8 μg/mL). Antifungal susceptibility test should be provided with reference to the guidance of Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) and European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) at the request of a specially designed checklist for Mycopathologia case reports [8]. CLSI and EUCAST have no break point documents on drug sensitivity of Mucor irregularis at present. However, the value of MIC can be used as a basis for drug selection.

For treatment, methylprednisolone was tapered, and his concurrent type 2 diabetes was controlled with insulin. We also administered supplemental albumin, hepatoprotective therapy including magnesium isoglycyrrhizinate injection and domestic glutathione tablets, intravenous immunoglobulin, and other symptomatic supportive treatment. Daily debridement of necrotic eschar was performed. Cefoperazone sodium and sulbactam sodium in combination with amphotericin B were administered intravenously. Amphotericin B was initiated at a dose of 5 mg/d and increased by 5 mg per day; the maximum dose administered was 40 mg/d. After one week of treatment, his expectoration was relieved. The dose was reduced to 25 mg/d after 9 days due to renal dysfunction and extreme intolerance. After 3-week treatment, the ulcers exhibited continuous enlargement with black eschar (Fig. 1b); at this time, the dose of methylprednisolone had been tapered to 6 mg/d, and the cumulative administered dose of amphotericin B was 615 mg. Due to his poor appetite and rise of serum creatinine level from 56 to 141 μmol/L, amphotericin B was withdrawn and the patient was transferred to the department of Burns at our hospital to receive three rounds of extensive surgical debridement combined with split-thickness skin grafting and VAC drainage on the right lower leg (Fig. 1c, d). The wound gradually healed with grafts take at two weeks (Fig. 1e) and 3-month follow-ups (Fig. 1f). No signs of recurrence were observed at 36-month follow-up.

Discussion

M. irregularis belongs to the phylum Mucormycota and order Mucorales. It is an opportunistic fungal pathogen that is mainly found in soil and decaying fruits and vegetables [9]. This pathogen has a world-wide distribution while mainly found in China [9]. Twenty-six cases with M. irregularis-associated cutaneous mucormycosis were reviewed along with the present case (Table 1). Eight cases were excluded because they do not have English abstracts.

Eighteen cases were from China [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26], the others were from Japan (3 cases) [3, 6, 27], India (3 cases) [28,29,30], America (2 case) [2, 4], and France (1 case) [5] as well. It implies that M. irregularis-associated cutaneous mucomycosis is an endemic disease mainly occurred in China.

In these cases, the locations of cutaneous lesions included face (11 cases), upper limbs (10 cases), and lower limbs (6 cases). The most commonly affected sites involving exposed areas such as the face and the extremities indicates that this type of infection is acquired from the environment and it is more likely to occur via direct inoculation of fungal spores from M. irregularis into the skin.

Of these 27 cases, plaque/papule (18 cases), nodule (6 cases), ulcer (17 cases) and crust/eschar (12 cases) were the common types of skin lesions. Unlike other mucormycosis, M. irregularis infection usually occurs in immunocompetent hosts (16 cases without comorbidities), exhibits a more indolent and chronic course (mean 42.67 months, ranging from 1 week to 18 years) due to its weak temperature tolerance and lack of propensity for angioinvasion [8, 19]. Aspergillosis and fusariosis should be considered in differential diagnosis clinically and entomophthoramycosis including basidiobolomycosis and conidiobolomycosis should be differentiated histopathologically as in our case. Most cases were cured (21 cases) or improved (5 cases) except one ineffective (this case was treated with itraconazole, fluconazole, and ketoconazole). These results mean that prognosis of cases caused by M. irregularis-associated cutaneous mucomycosis is excellent. However, treatment delay or inappropriate treatment may result in considerable disfiguration, especially on face.

The main treatment strategies for cutaneous mucormycosis include systemic antifungal drugs alone or combined with surgical therapy. Antifungal drugs for mucormycosis including amphotericin B and new azoles, such as posaconazole and isavuconazole are recommended [31]. There were 20 cases treated with intravenous amphotericin B/liposomal amphotericin (mean dose 1.93 g, range from 0.61 to 7.07 g) alone or combined with posaconazole/itraconazole/terbinafine/ketoconazole. Azoles are commonly used in case of failure or intolerance to amphotericin B [7]. Among other treatments without amphotericin B, itraconazole were used alone or combined with terbinafine/potassium iodide in 5 cases. Fluconazole were used in 2 cases alone with two improved at the end of treatment and one cured combined with debridement. Surgery like debridement/excision/skin graft were used alone (only 1 case) or combined with systemic antifungal agents in 7 cases with all cured. Treatment duration in combined group with antifungal agents and surgery (mean time 10.17 weeks, range from 2 to 24 weeks) was shorter than that in group of systemic antifungal agents alone (mean time 15.17 weeks, range from 2 to 32 weeks). Treatment outcomes in group of surgery were all cured while in group of systemic antifungal agents alone were cured in 14 cases, improved in 5 cases, failed in 1 case. It was impressive that one case was cured by excision alone within 2 weeks [24]. Our case confirmed that surgery is good way to be combined with Amb. Our patient had arteries stenosis of lower extremities and was diabetic, which might contribute to the slower response to amphotericin therapy.

In addition to the surgical debridement of necrotic tissue, VAC removes the necrotic tissues, fungi and secretions from the wounds and helps maintain cleanliness and appropriate humidity at the wound surface. Moreover, it promotes local blood circulation, favors tissue granulation and angiogenesis, facilitates permeation of antifungal drugs in the involved tissue [32], improves the inflammatory response and thus ensures elimination of any residual infectious elements [33]. Furthermore, it facilitates cell proliferation and repair, which accelerates the healing of wounds. Therefore, VAC drainage exhibits a synergistic effect in combination with debridement for cure of cutaneous infection [34].

In conclusion, surgical debridement with VAC drainage therapy is a good option to treat patients with M. irregularis-associated cutaneous mucormycosis who are not controlled by systemic antifungal agents.

References

Alvarez E, Cano J, Stchigel AM, et al. Two new species of Mucor from clinical samples. Med Mycol. 2011;49:62–72.

Abuali MM, Posada R, Del TG, et al. Rhizomucor variabilis var. regularior and Hormographiella aspergillata infections in a leukemic bone marrow transplant recipient with refractory neutropenia. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:4176–9.

Tomita H, Muroi E, Takenaka M, et al. Rhizomucor variabilis infection in human cutaneous mucormycosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:312–4.

Schell WA, O’Donnell K, Alspaugh JA. Heterothallic mating in Mucor irregularis and first isolate of the species outside of Asia. Med Mycol. 2011;49:714–23.

Rammaert B, Angebault C, Scemla A, et al. Mucor irregularis-associated cutaneous mucormycosis: case report and review. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2014;6:62–5.

Yamaguchi S, Okubo Y, Katano A, Sano A, Uezato H, Takahashi K. Primary cutaneous mucormycosis caused by Mucor irregularis in an elderly person. J Dermatol. 2015;42:210–4.

Riley TT, Muzny CA, Swiatlo E, Legendre DP. Breaking the mold: a review of mucormycosis and current pharmacological treatment options. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50:747–57.

Bouchara J, Chaturvedi V. The curious case of “case report” of infections caused by human and animal fungal pathogens: an educational tool, an online archive, or a format in need of retooling. Mycopathologia. 2018;183:879–91.

Lu XL, Najafzadeh MJ, Dolatabadi S, et al. Taxonomy and epidemiology of Mucor irregularis, agent of chronic cutaneous mucormycosis. Persoonia. 2013;30:48–56.

Li CY, Li Y, Hu ZM. A case report of primary cutaneous mucormycosis caused by Rhizomucor variabilis. J Clin Dermatol. 2004;33:158–9 (in Chinese).

Fu MH, Chen H, Song LY, et al. Facial mucormycosis due to Rhizomucor variabilis: a case report. Int J Dermatol Venereol. 2006;32:67–9 (in Chinese).

Mh FU, Liu ZH, Chen W, et al. Five cases of cutaneous zygomycosis. Chin J Dermatol. 2009;42:545–7 (in Chinese).

Lu XL, Liu ZH, Shen YN, et al. Primary cutaneous zygomycosis caused by rhizomucor variabilis: a new endemic zygomycosis? A case report and review of 6 cases reported from China. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:e39-43 (in Chinese).

Zhao Y, Zhang Q, Li L, Zhu J, Kang K, Chen L. Primary cutaneous mucormycosis caused by Rhizomucor variabilis in an immunocompetent patient. Mycopathologia. 2009;168:243–7.

Zhou JC, Wang L, Xu Y, et al. A case of primary cutaneous mucormycosis caused by Rhizomucor variabilis. Chin J Mycol. 2011;6:361–2 (in Chinese).

Li DM, Lun LD. Mucor irregularis infection and lethal midline granuloma: a case report and review of published literature. Mycopathologia. 2012;174:429–39.

Qi B, Chen X, Ren FL, et al. Primary cutaneous zygomycosis caused by Rhizomucor variabilis: a case report and literature review. J Clin Dermatol. 2012;41:329–33.

Kang D, Jiang X, Wan H, Ran Y, Hao D, Zhang C. Mucor irregularis infection around the inner canthus cured by amphotericin B: a case report and review of published literatures. Mycopathologia. 2014;178:129–33 (in Chinese).

Li LN, Zhang SM, Ran YP, et al. A case of primary cutaneous mucormycosis caused by Mucor irregularis in Henan province. Chin J Dermatol. 2014;47:81–4 (in Chinese).

Xia XJ, Shen H, Liu ZH. Primary cutaneous mucormycosis caused by Mucor irregularis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:875–8.

Huang YT, Liao CH, Hsueh PR. Image gallery: cutaneous infections caused by Alternaria alternata and Mucor irregularis 1 year apart in a patient with iatrogenic Cushing syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:e82.

Zhang S, Li ZL, Li JG, et al. Cutaneous mucormycosis caused by Mucor irregularis: a case report. Chin J Dermatol. 2018;51:142–4 (in Chinese).

Gong J, Qi DW, Lv J, et al. A case of primary cutaneous mucormycosis with acute onset. Chin J Derm Venereol. 2018;32:311–3 (in Chinese).

Liang GZ, Xu WQ, Zheng XL, et al. Successful treatment by surgery of a primary cutaneous mucormycosis caused by Mucor irregularis. Mycopathologia. 2018;183:445–9.

Wang X, Wang A, Wang X, Li R, Yu J. Cutaneous mucormycosis caused by Mucor irregularis in a patient with CARD9 deficiency. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:213–4.

Wei LW, Wang H, Song YG, et al. Disfiguring Mucor irregularis infection cured by amphotericin B and itraconazole: a case report and treatment experience. Mycopathologia. 2019;184(5):677–82.

Matsudate Y, Murao K, Urano Y, et al. Primary cutaneous mucormycosis caused by Mucor irregularis in an immunocompetent patient. J Dermatol. 2015;42:267–8.

Hemashettar BM, Patil RN, O’Donnell K, Chaturvedi V, Ren P, Padhye AA. Chronic rhinofacial mucormycosis caused by Mucor irregularis (Rhizomucor variabilis) in India. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:2372–5.

Patil AB, Chandramohan K, Shivaprakash MR, Nadgir SD, Lakshminarayana SA. Rhizomucor variabilis: a rare causative agent of primary cutaneous zygomycosis. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2013;31:302–5.

Chander J, Kaur M, Bhalla M, et al. Changing epidemiology of mucoralean fungi: chronic cutaneous infection caused by Mucor irregularis. Mycopathologia. 2015;180:181–6.

Castrejon-Perez AD, Welsh EC, Miranda I, Ocampo-Candiani J, Welsh O. Cutaneous mucormycosis. Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:304–11.

Caniano DA, Ruth B, Teich S. Wound management with vacuum-assisted closure: experience in 51 pediatric patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:128–32.

Estrada-Chavez GE, Vega-Memije ME, Arenas R, et al. Eumycotic mycetoma caused by Madurella mycetomatis successfully treated with antifungals, surgery, and topical negative pressure therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:401–3.

Blazquez D, Ruiz-Contreras J, Fernandez-Cooke E, et al. Lichtheimia corymbifera subcutaneous infection successfully treated with amphotericin B, early debridement, and vacuum-assisted closure. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:e13–5.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the mycological laboratory staff of department of Dermatology & Venereology, Research Center for Medical Mycology, Peking University First Hospital, including Prof. Ruoyu Li; Zhe Wan, PhD, without whose invaluable assistance, antifungal drug sensitivity test in vitro in this study could not have been performed. We also appreciate greatly the valuable comments on the diagnosis of this case from Prof. Liyan Xi, Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HZ and YX were the guarantors for the entire manuscript; HZ and PG participated in conception and design of the work; HZ, PG, XT, HW, JX, JH and YX contributed to data collection of patient; XT and PG wrote the paper; HZ, PG, XT, HW, JX, JH and YX participated in analyzing data and revising the manuscript for significant intellectual content; all authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Handling Editor: Cunwei Cao.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, X., Guo, P., Wong, H. et al. Vacuum-Assisted Closure and Skin Grafting Combined with Amphotericin B for Successful Treatment of an Immunocompromised Patient with Cutaneous Mucormycosis Caused by Mucor irregularis: A Case Report and Literature Review. Mycopathologia 186, 449–459 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11046-021-00551-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11046-021-00551-3