Abstract

Cryptococcosis by Cryptococcus gattii occurs mainly in immunocompetent hosts, however, during the last decades, a growing number of cases in immunocompromised individuals have been noticed around the world. This report presents epidemiological, clinical and outcome aspects of patients with cryptococcosis caused by this species from a non-endemic area in Brazil. Of 278 Cryptococcus spp. clinical isolates recovered during the same period, 267 (96%) were molecularly identified as Cryptococcus neoformans VNI genotype and 11 (4%) as C. gattii VGII genotype by URA-5 RFLP. Of the 11 C. gattii patients, eight were male, mean age of 47.5 years. Of these, four were HIV-infected, one was kidney transplanted, one presented low CD4+ T cells values of unknown cause, another presented chronic liver disease meanwhile the remaining four were apparently immunocompetent. Disseminated disease and cryptococcal meningitis were present in four patients each. Most patients received amphotericin B plus fluconazole. Seven out of the 11 patients cured and four died before or during the therapy. The increased number of individuals with cryptococcosis by this species during the last decades needs to be carefully evaluated specially those who are HIV-infected. Nevertheless, Cryptococcus species differentiation is currently relevant in order to better know their relation with geographical, clinical host preference and outcome particularities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cryptococcus neoformans is worldwide distributed and causes cryptococcal meningitis in immunocompromised hosts, mostly HIV-infected who present advanced immunodeficiency and severe fungal disease at admission. Consequently, high mortality rates of 60–70% are still reported from limited-resource settings [1, 2]. Furthermore, 17–22% of diagnosed cases have no predisposing factors and develop severe pulmonary or extra-pulmonary cryptococcosis [3]. Otherwise, Cryptococcus gattii formerly restricted to tropical and subtropical regions causes disease predominantly in immunocompetent individuals. During the last decades, several outbreaks of cryptococcosis by this species occurred in temperate regions from North America which involved nearly 40% of immunocompromised individuals [4,5,6,7]. This fact supports the geographical expansion of C. gattii and could suggest changes in its host preference as evidenced by the increased rates of cryptococcosis in HIV-infected patients reported from several regions around the world during the last years [8,9,10].

Several authors have pointed out differences on clinical and outcome features between patients with C. gattii infection and those with C. neoformans infection [11, 12]. Patients with cryptococcosis by C. gattii can evolve with more morbidity and poor outcome and this fact would be associated with more severe pulmonary and cerebral cryptococcomas which even require surgery resection and longer periods of antifungal therapy [11, 13]. Otherwise, different authors have suggested that the host immune status is more pivotal to define the clinical picture and outcome than the cryptococcal species involved [14, 15]. In immunocompetent individuals, C. gattii infection often presents a less subacute picture during several weeks or months and can be mistaken with other infectious or non-infectious diseases especially when lung and brain cryptococcomas are seen on computerized tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance (MRI) images [16, 17].

Usually, cryptococcal meningitis by C. gattii in HIV-infected patients presents more subacute evolution similar to that observed in C. neoformans despite, there are scarce available data and few differences related to clinical picture and in-hospital mortality rates [9, 18]. This study aims to present some epidemiological, clinical and outcome features of patients with cryptococcosis by C. gattii diagnosed at the teaching hospital from a non-endemic area in Brazil focusing on HIV-infected cases.

Population and Methods

In order to identify cryptococcosis cases admitted at the teaching hospital of Triângulo Mineiro Federal University in Uberaba, Minas Gerais, Brazil, from 1998 to 2017, the micological diagnosis records were retrospectively reviewed. Cryptococcosis case definition was based on the clinical picture (pulmonary, meningeal or cutaneous involvement) plus a Cryptococcus sp. positive culture on Sabouraud dextrose Agar, with or without India ink positive stain or a positive Latex-crypto antigen test (IMMY Mycologics Inc, OK, USA). Among the confirmed cases, those who presented C. gattii infection diagnosed by l-Canavanine-glycine-bromothymol blue (CGB) agar and orotidine monophosphate pyrophosphorylase (URA5) gene restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis were selected [19, 20]. Demographic, epidemiologic, clinical and outcome data of these patients were obtained from their medical records, registered and analyzed through descriptive statistics. This study was approved by the institutional ethical board on protocol number 2365.

Results

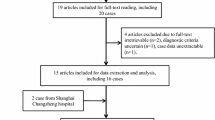

Along the last 20 years, 278 patients with cryptococcosis were admitted at the teaching hospital. Of these, 271 were HIV-infected and presented cryptococcal meningitis. Of 278 clinical isolates recovered from these cases, 267 (96%) were C. neoformans VNI genotype and 11 (4%) were C. gattii VGII genotype (Fig. 1). The 11 C. gattii patients were from the Triângulo Mineiro, Southeast region from Brazil and eight (72.7%) out of the 11 were male, median age of 47.4 years. They had no history of trips to known endemic areas. The average time between the onset of symptoms until the diagnosis was of 37 days, and the median time of hospitalization was 35 days. Fever, headache and weight loss were the predominant claims and most of them presented underlying medical conditions favoring this infection (Table 1). Four out the 11 patients presented cryptococcal meningitis, four disseminated fungal infection, two cutaneous primary cryptococcosis and one pulmonary involvement. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed: mononuclear pleocytosis, low glucose level, and high protein level in most cases. Diagnosis was based on: positive culture in 100% of the cases, India ink stain in 63%, biopsy of skin fragments stained with Grocott and Mucicarmine in 27% and Latex-Cryptococcus antigen test in 45% of cases. Granulomatous inflammatory lesions at CT and MRI images of the lungs and CNS were seen in four (36%) patients, respectively, of whom three were apparently immunocompetent.

Among these patients, four were HIV-infected of whom, three were male, median age of 34.2 years and in two cases, HIV infection and cryptococcosis were concomitantly diagnosed. The median time since the onset of symptoms until diagnosis was 8.5 days, and the median time of hospital staying was 47 days. Despite the antifungal therapy, two patients died and a disseminated fungal infection to five or more organs was evidenced at necropsy. Of the two survivors, one presented pulmonary cryptococcosis and the other cryptococcal meningitis.

The kidney-transplanted patient died before the antifungal therapy, and a disseminated cryptococcosis was seen at necropsy. The patient with low CD4+ T cells count of unknown cause developed cryptococcal meningitis and evolved with good outcome after antifungal therapy. The patient with chronic liver failure had history of thrombosis of the cava vein 11 years before and referred skull traumatism three months before the onset of neurological picture. At admission, he was severely sick, with mental confusion and symptoms of intracranial increased pressure. Brain and pulmonary cryptococcomas were seen at CT and MRI image which were confirmed by histopathology and CSF positive culture. Due to the evidence of severe hydrocephalus, a ventriculo-peritoneal shunt was placed and amphotericin B and fluconazole were administered during 6 months. His clinical picture progressively improved, and currently, he is followed as an outpatient.

The two patients with primary cutaneous cryptococcosis were farmers with history of direct traumatism with Eucalyptus logs. They presented chronic atypical inflammatory lesions in their arms which did not improve despite several antibiotic prescriptions. Underling immunosuppression and asymptomatic pulmonary or meningeal involvement were also discarded. They received fluconazole during 10 weeks, and both had a good outcome. One of these cases had been already reported. Several attempts to isolate C. gattii from different trees and sites on their farms and neighborhood were unsuccessful. In the remaining four patients, apparently immunocompetent and despite an adequate clinical investigation, no underlying medical conditions were found.

Discussion

In accordance with other authors, the burden of human disease due to C. gattii is unrecognized as many laboratories around the world do not undertake detailed species of Cryptococcus clinical isolates [21,22,23]. Previously, C. gattii was considered a primary pathogen restricted to tropical and subtropical areas with remarkable preference by immunocompetent hosts. The growing number of C. gattii cryptococcosis reports in HIV-infected patients from Africa together with data obtained from outbreaks in temperate regions from North America, where 40% of the affected individuals had underlying immunosuppression, called the attention of the scientific community to this fungus species [24,25,26]. Currently, the evidence confirms the C. gattii geographical expansion around the world and could permit to arise the hypothesis that changes in its host preference could be on going. However, this requires additional studies and a critical review of the cases already reported. [8,9,10, 27,28,29].

The present C. gattii case series accounts for 4% of 278 cases of cryptococcosis diagnosed during the last 20 years and resulted from the interest to improve the diagnosis at species and genotype level in a teaching hospital in the Southeast region of Brazil, where most reported cases of cryptococcosis occur in HIV-infected patients and are caused by C. neoformans VNI genotype. As possible, the migratory profile of the 11 C. gattii patients was investigated. They are from different towns of the Triângulo Mineiro, Southeast region, far from the known endemic areas situated in the North and Northeast regions of Brazil, which include the states of Amazonas, Pará, Bahia and Piauí [30, 31]. They denied having visited or travelled to these areas, where cryptococcal meningitis in immunocompetent hosts is often diagnosed and molecular studies of clinical and environmental C. gattii isolates have shown VGII genotype predominance [30,31,32,33,34]. Herein, this fact can be confirmed among the 11 patients whose clinical isolates evaluated by URA5-RFLP shown to be VGII genotype (Fig. 1).

Recent studies have shown that the highly recombining VGII genotype ancestors from the native rainforest of the Northern Brazil expanded its boundaries to North America, where it caused outbreaks in Vancouver Island (Canada), mainland of British Columbia and subsequently in the Pacific Northwest region of the USA [4, 35, 36]. Since then, the incidence of C. gattii infections in this region was estimated to be approximately 27 times higher than endemic areas of Northern Australia in Aboriginals [27]. In Brazil, cryptococcosis caused by VGII lineages is endemic in the North and Northeast regions, where natural infection occurs early in life [30, 34]. In accordance with this hypothesis, the endemicity of this species in Brazil might be also expanding its limits and could explain the occurrence of cases in non-endemic areas.

Through several molecular tools, four C. gattii genotypes: VGI, VGII, VGIII and VGIV were already identified. The VGIIa, b and c subgenotypes were also defined showing the genetic diversity of this species [37, 38]. This fact partially contributes to understand the variability of its geographical distribution, virulence, host preference and somehow the clinical outcome, despite controversial data, which highlight the host immunity instead of the species role as the key factor [11, 14, 34]. The VGII genotype predominated in the Vancouver outbreak and its a subgenotype was considered the most virulent. The VGI predominates in Australia and it has been associated with more central nervous system involvement, whereas VGIII and VGIV are more likely to be found in HIV-infected patients rather than in immunocompetent hosts. [8,9,10, 23, 25].

During the last years, reports from several authors pointed out high prevalence of cryptococcosis by C. gattii in HIV-infected patients, which contrast with the scarce number of cases reported from Brazil [8, 9, 22]. Here, most HIV-infected patients live in the South and Southeast regions, the most populous and considered non-endemic areas for C. gattii, which would explain the small number of cases reported. Four of the 11 cases herein presented were HIV-infected and in accordance with others, no apparent clinical or outcome differences were noticed when compared with those who presented cryptococcal meningitis by C. neoformans [14]. In addition, no granulomatous images at CT and MRI in lungs and CNS of these patients were observed, different from non-immunocompromised patients who are more likely to develop pulmonary or cerebral cryptococcomas as observed in four cases of the present series [13]. A previous Brazilian report described three HIV-infected patients from the South region with severe C. gattii infection and poor outcome [39]. Another Brazilian case series of 14 patients with cryptococcosis by VGII genotype from the North region, only two were HIV-infected [33]. In one report which evaluated 50 clinical isolates from HIV-infected patients from the West Central region from Brazil, only 3 were C. gattii [40]. These data support how C. gattii infection in HIV patients in Brazil seems to be less common than in other places [8,9,10, 25].

The epidemiological and clinical features of patients with cryptococcosis by C. gattii herein described are in line with those reported elsewhere to both immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts and reinforce the severity of clinical pictures with disseminated disease to several organs as evidenced by CT and MRI image or at necropsy [41,42,43]. Currently, in most places where cryptococcosis occurs, the species differentiation is not routinely performed due to logistical and economic limitations which could underestimate and explain the small number of C. gattii cases reported specially in HIV-infected patients.

References

Park BJ, Wannemuehler KA, Marston BJ, Govender N, Pappas PG, Chiller TM. Estimation of the current global burden of cryptococcal meningitis among persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS. 2009;23(4):525–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0b013e328322ffac.

Rajasingham R, Smith RM, Park BJ, et al. Global burden of disease of HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis: an updated analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(8):873–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30243-8.

Kiertiburanakul S, Wirojtananugoon S, Pracharktam R, Sungkanuparph S. Cryptococcosis in human immunodeficiency virus-negative patients. Int J Infect Dis. 2006;10(1):72–8.

Kidd SE, Chow Y, Mak S, et al. Characterization of environmental sources of the human and animal pathogen Cryptococcus gattii in British Columbia, Canada, and the Pacific Northwest of the United States. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(5):1433–43.

MacDougall L, Kidd SE, Galanis E, et al. Spread of Cryptococcus gattii in British Columbia, Canada, and detection in the Pacific Northwest, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13(1):42–50.

MacDougall L, Fyfe M, Romney M, Starr M, Galanis E. Risk factors for Cryptococcus gattii infection, British Columbia, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17(2):193–9. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1702.101020.

Bartlett KH, Cheng PY, Duncan C, et al. A decade of experience: Cryptococcus gattii in British Columbia. Mycopathologia. 2012;173(5–6):311–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11046-011-9475-x.

Litvintseva AP, Thakur R, Reller LB, Mitchell TG. Prevalence of clinical isolates of Cryptococcus gattii serotype C among patients with AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa. J Infect Dis. 2005;192(5):888–92.

Steele KT, Thakur R, Nthobatsang R, Steenhoff AP, Bisson GP. In-hospital mortality of HIV-infected cryptococcal meningitis patients with C. gattii and C. neoformans infection in Gaborone, Botswana. Med Mycol. 2010;48(8):1112–5. https://doi.org/10.3109/13693781003774689.

Galanis E, Macdougall L, Kidd S, Morshed M, British Columbia Cryptococcus gattii Working Group. Epidemiology of Cryptococcus gattii, British Columbia, Canada, 1999–2007. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16(2):251–7. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1602.090900.

Mitchell DH, Sorrell TC, Allworth AM, et al. Cryptococcal disease of the CNS in immunocompetent hosts: influence of cryptococcal variety on clinical manifestations and outcome. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20(3):611–6.

Speed B, Dunt D. Clinical and host differences between infections with the two varieties of Cryptococcus neoformans. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21(1):28–34.

Pappas PG. Cryptococcal infections in non-HIV-infected patients. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2013;124:61–79.

Chen S, Sorrell T, Nimmo G, et al. Epidemiology and host- and variety-dependent characteristics of infection due to Cryptococcus neoformans in Australia and New Zealand. Australasian Cryptococcal Study Group. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31(2):499–508.

Chau TT, Mai NH, Phu NH, et al. A prospective descriptive study of cryptococcal meningitis in HIV uninfected patients in Vietnam: high prevalence of Cryptococcus neoformans var grubii in the absence of underlying disease. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:199. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-10-199.

Nakao M, Muramatsu H, Takahashi T, et al. Cryptococcus gattii genotype VGIIa infection in an immunocompetent Japanese patient: a case report and mini-review. Intern Med. 2016;55(20):3021–4.

Byrnes EJ III, Li W, Lewit YP, et al. First reported case of Cryptococcus gattii in the Southeastern USA: implications for travel-associated acquisition of an emerging pathogen. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(6):e5851.

Morgan J, McCarthy KM, Gould S, et al. Cryptococcus gattii infection: characteristics and epidemiology of cases identified in a South African province with high HIV seroprevalence, 2002–2004. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(8):1077–80.

Kwon-Chung KJ, Polacheck I, Bennett JE. Improved diagnostic medium for separation of Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans (serotypes A and D) and Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii (serotypes B and C). J Clin Microbiol. 1982;15(3):535–7.

Meyer W, Castañeda A, Jackson S, Huynh M, Castañeda E. Molecular typing of IberoAmerican Cryptococcus neoformans isolates. IberoAmerican Cryptococcal Study Group. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9(2):189–95.

Galanis E, Hoang L, Kibsey P, et al. Clinical presentation, diagnosis and management of Cryptococcus gattii cases: lessons learned from British Columbia. Can J Dis Med Microbiol. 2009;20:23–8.

Byrnes EJ 3rd, Marr KA. The outbreak of Cryptococcus gattii in Western North America: epidemiology and clinical issues. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2011;13(3):256–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11908-011-0181-0.

Harris JR, Lockhart SR, Debess E, et al. Cryptococcus gattii in the United States: clinical aspects of infection with an emerging pathogen. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;53(12):1188–95.

Byrnes EJ 3rd, Bartlett KH, Perfect JR, Heitman J. Cryptococcus gattii: an emerging fungal pathogen infecting humans and animals. Microbes Infect. 2011;13(11):895–907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micinf.2011.05.009.

Chaturvedi V, Chaturvedi S. Cryptococcus gattii: a resurgent fungal pathogen. Trends Microbiol. 2011;19(11):564–71.

Springer DJ, Billmyre RB, Filler EE, et al. Cryptococcus gattii VGIII isolates causing infections in HIV/AIDS patients in Southern California: identification of the local environmental source as arboreal. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10(8):e1004285. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004285.

Datta K, Bartlett KH, Baer R, et al. Spread of Cryptococcus gattii into Pacific Northwest region of the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(8):1185–91.

Chowdhary A, Randhawa HS, Boekhout T, et al. Temperate climate niche for Cryptococcus gattii in Northern Europe. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18(1):172–4. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1801.111190.

Kidd SE, Hagen F, Tscharke RL, et al. A rare genotype of Cryptococcus gattii caused the cryptococcosis outbreak on Vancouver Island (British Columbia, Canada). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(49):17258–63.

Trilles L, Lazéra Mdos S, Wanke B, et al. Regional pattern of the molecular types of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii in Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2008;103(5):455–62.

Brito-Santos F, Barbosa GG, Trilles L, et al. Environmental isolation of Cryptococcus gattii VGII from indoor dust from typical wooden houses in the deep Amazonas of the Rio Negro basin. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(2):e0115866. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0115866.

Freire AK, dos Santos Bentes A, de Lima Sampaio I, et al. Molecular characterization of the causative agents of Cryptococcosis in patients of a tertiary healthcare facility in the state of Amazonas-Brazil. Mycoses. 2012;55(3):e145–50.

Santos WR, Meyer W, Wanke B, et al. Primary endemic Cryptococcosis gattii by molecular type VGII in the state of Pará, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2008;103(8):813–8.

Martins LM, Wanke B, Lazéra Mdos S, et al. Genotypes of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii as agents of endemic cryptococcosis in Teresina, Piauí (northeastern Brazil). Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2011;106(6):725–30.

Hagen F, Ceresini PC, Polacheck I, et al. Ancient dispersal of the human fungal pathogen Cryptococcus gattii from the Amazon rainforest. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(8):e71148. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0071148.

Souto AC, Bonfietti LX, Ferreira-Paim K, et al. Population genetic analysis reveals a high genetic diversity in the Brazilian Cryptococcus gattii VGII population and shifts the global origin from the Amazon rainforest to the semi-arid desert in the Northeast of Brazil. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(8):e0004885. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0004885.

Ngamskulrungroj P, Gilgado F, Faganello J, et al. Genetic diversity of the Cryptococcus species complex suggests that Cryptococcus gattii deserves to have varieties. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(6):e5862. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0005862.

Meyer W, Aanensen DM, Boekhout T, et al. Consensus multi-locus sequence typing scheme for Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii. Med Mycol. 2009;47(6):561–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/13693780902953886.

Severo LC, de Mattos Oliveira F, Londero AT. Cryptococcosis due to Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii in Brazilian patients with AIDS. Report of three cases. Rev Iberoam Micol. 1999;16(3):152–4.

Fernandes Ode F, Costa TR, Costa MR, Soares AJ, Pereira AJ, Silva Mdo R. Cryptococcus neoformans isolated from patients with AIDS. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2000;33(1):75–8.

Chayakulkeeree M, Wangchinda P. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with cryptococcal meningoencephalitis in a resource-limited setting. J Med Assoc Thai. 2014;97(Suppl 3):S26–34.

Chen SC, Slavin MA, Heath CH, et al. Clinical manifestations of Cryptococcus gattii infection: determinants of neurological sequelae and death. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(6):789–98.

Ecevit IZ, Clancy CJ, Schmalfuss IM, Nguyen MH. The poor prognosis of central nervous system cryptococcosis among nonimmunosuppressed patients: a call for better disease recognition and evaluation of adjuncts to antifungal therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(10):1443–7.

Leão CA, Ferreira-Paim K, Andrade-Silva L, et al. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis caused by Cryptococcus gattii in an immunocompetent host. Med Mycol. 2011;49(4):352–5. https://doi.org/10.3109/13693786.2010.530697.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and the writing of the paper.

Additional information

Handling Editor: Marcia de Souza Carvalho Melhem.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Damasceno-Escoura, A., de Souza, M.L., de Oliveira Nunes, F. et al. Epidemiological, Clinical and Outcome Aspects of Patients with Cryptococcosis Caused by Cryptococcus gattii from a Non-endemic Area of Brazil. Mycopathologia 184, 65–71 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11046-018-0304-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11046-018-0304-3