Abstract

A grateful person could be said to have a lower threshold for gratitude and might feel more gratitude than others. However, both the value of gifts and the intention of helpers may be important determinations. This study aimed to examine the roles of perceived value and intention in the relationship between trait and state gratitude. Two hundred and forty-four Taiwanese individuals aged 20 or above completed measures of variables of interest. Structural equation modeling showed that goodness of value and intention naturally group together and form a unique appraisal belief (i.e., perceived goodness). Moreover, path analyses indicated that perceived goodness acted as a full mediator of the association between trait and state gratitude. In other words, people with higher levels of trait gratitude had a propensity to perceive greater value of the gift itself and the helper’s genuine helpful intentions, which may elevate their degree of state gratitude. Furthermore, a multigroup analysis found that the paths did not differ by gender. Implications for future research and limitations of the present findings are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Throughout history and in many cultures, gratitude has been given a central position in philosophical and theological theories in the virtue ethics tradition (Dumas et al. 2002). The experience and expression of gratitude are regarded as enhancing for an individual’s personal and relational well-being and therefore beneficial for both individuals and society (Harpham 2004). Following Rosenberg’s (1998) level of analysis approach to emotion, gratitude should consist of an affective trait as well as an emotional state. Thus, a person who is high on the affective trait of gratitude should experience gratitude easily and often. Using a daily process methodology, McCullough et al. (2004) showed that higher trait levels of gratitude are related to more frequent and intense experiences of state gratitude in daily life.

Although these associations seem reasonable, how trait gratitude is related to state gratitude is still unclear. For example, if two people receive help in an identical situation, it is intuitive that the person higher in trait gratitude would feel more state gratitude. Currently, there is no explanation of why this might occur. In addition, despite growing interest in gratitude, most studies were conducted in the United States. Few studies have investigated gratitude and its association in Asian or African culture. As we know, gratitude is deeply embedded in cultural frameworks (Cohen 2006). In this study, we sought to address this gap between the trait and state gratitude and further explore possible mediators in Chinese culture.

Trait and State Gratitude

In general, gratitude has been conceptualized at both the emotion and trait levels (e.g., Emmons et al. 2003; Watkins et al. 2003). Emotion is a temporal object-specific affective state that gives rise to feelings of pleasure and displeasure that are linked to ongoing automatic evaluations of the world (Clore and Schnall 2005; Weiner et al. 1979). Thus, gratitude, as an emotion, can be understood as a subjective felt sense of wonder, thankfulness and appreciation for benefits received.

On the other hand, an affective trait is an emotional disposition and describes a particular person’s threshold for experiencing a particular emotion. From this point of view, people with higher levels of trait gratitude should have a relatively low threshold for experiencing gratitude; thus, they should feel more gratitude than others (Rosenberg 1998). Therefore, as a trait, gratitude can be understood as a predisposition to experience the state of gratitude. That is, affective traits (i.e., trait gratitude) “exert an organizational influence on affective states (i.e., state gratitude)” (Rosenberg 1998). Prior work has also shown that state gratitude and trait gratitude are positively correlated (McCullough et al. 2004; Wood et al. 2008).

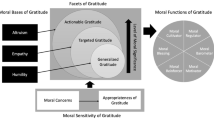

Perceived “Goodness” as a Possible Path from Trait Gratitude to State Gratitude

Based on this schematic hypothesis of gratitude, more grateful people had specific schematic biases toward viewing help as more beneficial, which explained why they felt more gratitude following help (Wood et al. 2010). Some studies have also shown that more grateful people saw the situation as higher in altruism and value, and this different interpretation of the situation may be a mediator between trait gratitude and the amount of gratitude experienced following aid (state gratitude). For example, Wood et al.’s (2008) findings suggest that grateful people have characteristic schemas that influence how they interpret help-giving situations. This is consistent with evidence showing that people have biases toward interpreting other people’s intentions and behaviors as similar to their own (e.g., Markus et al. 1985) and, more generally, evidence of characteristic biases in processing and emotional disorders (e.g., Beck 1976).

Moreover, scholars have suggested that people are grateful (i.e., high in trait gratitude) because they feel that life has been overly abundant for them (e.g., Watkins et al. 2003). Grateful people do not feel that life has been unfair, that they have not received their “just desserts”, or that they are entitled to more benefits than those that they have received in life. Rather, grateful individuals have a sense of grace and that life has provided them with much more than what they are entitled to. In other words, grateful people live life with a particular interpretive lens, seeing help as more altruistic and valuable. Equally, ungrateful people will view the help they see as lower on these dimensions. Trait gratitude may thus trigger the more perceived aids as “goodness”, such as altruistic intention and beneficial outcome.

Regarding the association between perceived “goodness” and state gratitude. According to Emmons and Crumpler (2000), individuals experience the emotion of gratitude when they affirm that “something good” has happened to them and they recognize that someone else is largely responsible for this benefit. McCullough (2002) further specified that this emotion is a cognitive-affective response to the recognition that one has been the beneficiary of someone else’s “good will”. Some scholars have also suggested that the beneficiaries will experience gratitude in response to benefits that (a) they perceive as valuable to them and (b) were provided intentionally and altruistically (rather than for ulterior motives) (Tesser et al. 1968; Wood et al. 2008).

Recently, Watkins (2014) further indicated that there were two determinants of reactions to aid. One was the goodness of the gift, which lies in the value of the gift. Tesser et al. (1968) first found that the more a subject said they valued the benefit, the more intense was the rating of state gratitude. The importance of perceived value to gratitude was also clearly demonstrated in a recent study by Algoe et al. (2008). That is, the more an individual values a benefit, the more gratitude is experienced. The other determinant was the goodness of the helper, which lies in the intentions of the giver. Gratitude appears to be experienced only when the beneficiary perceives that the gift was given for their benefit (e.g., Tesser et al. 1968; Wood et al. 2008). For example, Graham (1988) found that the perceived intentions or motivations of a helper are crucial to one’s experience of gratitude. Several studies have also demonstrated the importance of benevolent intentions on the part of the helper (e.g., Bar-Tal et al. 1977; Lane and Anderson 1976). That is, the more receivers attribute good intentions to a helper, the more likely they will be to experience gratitude.

Furthermore, complex interactions were observed between the two determinations. For example, Tesser et al. (1968) found that manipulating value additionally led to higher perceptions of genuine helpful intention and that manipulating genuine helpful intention additionally led to higher perceptions of value. This implied that manipulating one appraisal affected perceptions of other appraisals. This result suggests that these appraisals are not independent but associated with each other. The study from Lane and Anderson (1976) also demonstrated similar findings through a similar methodology by manipulating value and the benefactor’s good intentions. From these observations, a grateful person may simultaneously evaluate the two determinations (i.e., value and intention) when receiving an aid and in turn lead to more or less feelings of gratitude. In addition, previous studies have reported that females had higher scores than males on tests of gratitude (e.g., Froh et al. 2009; Kashdan et al. 2009). To satisfy our curiosity, we assessed whether appraisal mechanisms or perceived processes are different between females and males.

Aim of the Present Study

A grateful person could be said to have a lower threshold for gratitude and might feel more gratitude than others, but if two people receive help in an identical situation, does the person higher in trait gratitude feel more state gratitude? If yes, why does this happen? Research has demonstrated that grateful individuals are more likely to experience gratitude when they receive a favor that is perceived to be (1) valued by the recipient and (2) given by a benefactor with benevolent intentions (e.g., Bar-Tal et al. 1977; Graham 1988; Lane and Anderson 1976; Tesser et al. 1968). Furthermore, the two appraisal elements may interact with each other to unify a single evaluative system. In other words, both the value of gifts and the intention of helpers may be important determinations that explain why individuals with higher levels of gratitude could experience more grateful feelings.

This study aimed to examine the roles of perceived value and intention in the relationship between trait and state gratitude and to further explore the difference between females and males. Thus, we propose that the two determinations of goodness (i.e., the gift and the helper) will form a unique appraisal belief (i.e., perceived goodness) and in turn mediate the relationship between trait and state levels of gratitude. In a word, the main hypothesis of the current study is that perceived goodness consisted of benevolent intention and positive value mediated the association between trait and state gratitude.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The study opportunistically recruited 244 persons via SurveyMonkey, an online survey tool. All included participants were aged 20 years or older (M = 31.72, SD = 8.70). In total, 86 participants were male (35.2%), and 158 participants were female (64.8%). With regard to the age groups, 54.1% of participants were between 20 and 29 years old, 29.5% were between 30 and 39 years old, 11.9% were between 40 and 49 years old, and 4.5% were older than 50 years of age.

Participants were recruited online via a variety of social networking websites, accruing responses via a variety of initiating Facebook pages, university bulletin boards, and questionnaire survey pages. Participants were informed of the nature of the study, and those who wished to take part consented online.

Each participant completed the same questionnaire comprised of the evaluative vignettes, the Gratitude Questionnaire (GQ), and basic information via an online platform named SurveyMonkey. Participants first completed a brief series of questions describing their gender, age, education, job, religious affiliation, and residential area. Second, they were asked to finish the GQ and then perform the evaluative vignettes and imagine themselves as the main character in the stories. Upon completion, they submitted their answers online.

Materials

Evaluative Vignettes

There were four vignettes, each of which was followed by three questions. Each of the vignettes detailed a situation in which the participant had been helped by another person and was based on prior studies (e.g., Wood et al. 2008). The topics of the vignettes were being assisted to pay for books, having a friend offer to cheer you up when you have conflicts with the family, having someone let you borrow his/her car, and receiving care when sick (see a sample vignette as listed below). The situations described were designed to be ambiguous and not to suggest any particular attribution.

It’s the beginning of the semester, and you’re standing in line at the bookstore to buy all the books for your classes. You are waiting in line with a friend, and the both of you joke about how long the line is taking. After a long wait, the cashier rings you up, and you find out that the total cost for your books is NT1500, which is much more expensive than what you expected. You only have NT1000 in your checking account. As you are standing there wondering what to do, your friend offers to pay the extra NT500 for you: “Don’t worry about it. I’ve been in that situation before and it’s a real bummer! Let me pay for it and you won’t have to stress about getting your books in time for the first exam or anything.” You accept the friend’s offer and successfully buy all the books you need.

After each story, participants were asked to respond to three questions: (1) To what degree do you think the helper has a sincere desire to help you? (2) How valuable do you think this person’s help was to you? (3) To what degree do you feel grateful toward this person? These questions were measured on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 6 (extremely). Q1 assessed the perceived intention of the benefactor. Q2 assessed the perceived value of the help. Q3 assessed the level of state gratitude.

To examine the construct validity of the three study variables, we separately tested the variables to assess the extent to which each of the latent variables was represented by its indicators. For example, perceived intention was the latent variable, and all Q1 items across the four vignettes were indicators that reflect that construct. That is, all three study variables (i.e., perceived intention, perceived value, and state gratitude) were composed of four indicators.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to examine the construct validity of these measures. Regarding perceived intention, CFA yielded good model fits (χ2 (2) = 8.82, p = .012; SRMR = .025; GFI = .98; CFI = .98). More importantly, factor loadings were large and significant (standardized factor loadings ranged between .69 and .82, ps < .001). Regarding perceived value, CFA also yielded good model fits (χ2 (2) = 7.44, p = .024; SRMR = .027; GFI = .99; CFI = .98), and standardized factor loadings ranged between .68 and .80 (ps < .001). For state gratitude, CFA yielded good model fits again (χ2 (2) = 1.76, p = .415; SRMR = .012; GFI = .99; CFI = 1), and standardized factor loadings ranged between .60 and .89 (ps < .001).

Gratitude Questionnaire (GQ)

The GQ was employed to measure the trait gratitude (McCullough et al. 2002). Chen et al. (2009) translated and validated the GQ in Chinese and reported that a five-item model was a better fit than the original six-item model. Scale responses range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). A sample item is “I have so much in life to be thankful for.” Previous research indicated good internal consistency, with an α of .80 (Chen et al. 2009). The present study shows good internal consistency, with Cronbach’s α = .92.

Data Analysis

The two-step procedure recommended by Anderson and Gerbing (1988) was adopted to analyze the mediation effects. The measurement model was first tested to assess the extent to which each of the latent variables was represented by its indicators. If the measurement model was accepted, then the structural model was tested via the maximum likelihood estimation in the AMOS 19.0 program. Additionally, perceived intention and perceived value have been found to be associated with each other (e.g., Tesser et al. 1968; Lane and Anderson 1976). They were also highly correlated (r = .75, p < .001) in this study. Therefore, the two constructs were unified into a latent variable named “perceived goodness” in this study.

The following five indices were used to evaluate the goodness of fit of the model (Hu and Bentler 1999): chi-square statistics, standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR) less than .08, root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) less than .10, goodness of fit index (GFI) above .90, and comparative fit index (CFI) above .95. To compare two or more models, we examined the Akaike information criterion (AIC), with smaller values representing a better fit of the hypothesized model, and the expected cross-validation index (ECVI), with the smallest values exhibiting the greatest potential for replication.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The means, standard deviations, and correlations for the study variables are presented in Table 1. All the latent constructs were significantly correlated in conceptually expected ways (ps < .001). In other words, trait gratitude was not only positively associated with perceived goodness but also positively associated with state gratitude. Moreover, perceived goodness was also positively associated with state gratitude.

Measurement Model

The measurement model consisted of three latent factors (trait gratitude, perceived goodness, and state gratitude) and 11 observed variables. An initial test of the measurement model revealed a satisfactory fit to the data: χ2 (41, N = 244) = 111.81, p < .05; RMSEA = .084; SRMR = .043; GFI = .92; CFI = .96. All the factor loadings for the indicators on the latent variables were significant (ps < .001), indicating that all the latent factors were well represented by their respective indicators.

Structural Model

First, the direct path coefficient from the predictor (trait gratitude) to the criterion (state gratitude, β = .51, p < .001) in the absence of mediators was significant. Second, a partially mediated model (Model 1) with the mediator (perceived goodness) and a direct path from trait gratitude to state gratitude revealed a good fit to the data (Table 2). However, the standardized path coefficient from trait gratitude to state gratitude was nonsignificant (β = .02, p > .05). Thus, a fully mediated model (Model 2) without the direct path between trait gratitude and state gratitude (this path was constrained to zero) was subsequently tested and revealed a good fit to the data (Table 2). The results of the chi-square difference test showed the absence of a significant difference between Model 1 and Model 2 (△χ2 (1, N = 244) = .15, p > .05), but Model 2 showed better results in terms of relevant indices and a smaller AIC and EVCI than Model 1. Moreover, all the standardized path coefficients were significant. Taken together, Model 2 was selected as the best model (Fig. 1).

The bootstrap estimation procedure was used to test the significance of the mediation effects of perceived goodness on the association between trait and state gratitude. MacKinnon et al. (2004) claimed that the method can generate the most accurate confidence intervals for indirect effects. We generated 2000 bootstrapping samples from the original data set (N = 244) by random sampling. The examination of the indirect effect revealed that perceived goodness reached statistical significance as a unique mediator of the trait gratitude–state gratitude relationship (estimated indirect effect = .51, 95% CI = [.39~.61]).

Gender Differences

We found statistically significant gender differences in trait gratitude, perceived goodness and state gratitude (t = −3.07, p < .01; t = −4.29, p < .001; t = −4.74, p < .001, respectively). Moreover, females scored higher than males on these study variables.

Furthermore, we used multigroup analysis to identify whether the path coefficients differ significantly by gender. We compared the first model, which allowed the structural paths to vary across sexes, with the second model, which constrained the structural paths across sexes to be equal to examine the gender differences. All the other paths (i.e., factor loadings, error variances and structure covariances) were constrained to be equal. The nonsignificant chi-square differences between the two models, △χ2 (2, N = 244) = .25, p > .05, indicated that the final model did not differ by gender. We also calculated the critical ratios of differences (CRD) by dividing the difference between two estimates by an estimate of the standard error of the difference (Arbuckle 2003). None of the paths differed by gender.

Discussion

The present study aimed to test the important role of perceived intention and perceived value in the association between trait and state gratitude among Taiwanese adults. As expected, the recognition of value and genuine helpful intention were shown to form a robust latent variable (i.e., perceived goodness) in this study, implying that the two variables appear to co-occur in a constellation. This is in line with previous findings. For example, Tesser et al. (1968) showed that manipulating one of the appraisals (i.e., value) led to changes in the other appraisal (i.e., genuine helpful intention) and vice versa. That is, the two variables are not independent but are associated with each other (Lane and Anderson 1976). The result indicated that both the value of the benefit itself and the perceived agency of the benefactor would simultaneously influence the appraisals made in helping situations (Tesser et al. 1968; Weiner et al. 1979).

Likewise, in line with our expectations, the specific indirect effect of trait gratitude on state gratitude via perceived goodness was significant. That is, people with higher levels of trait gratitude had a propensity to perceive greater value of gift itself and the helper’s genuine helpful intentions, which may have elevated their level of state gratitude. McCullough et al. (2002) regarded the trait gratitude as a generalized tendency to recognize and respond with grateful emotion to the roles of other people’s benevolence (i.e., intention) and positive outcomes that one obtains (i.e., value). Furthermore, cognitive theories of emotion claim that cognitive appraisal is necessary for an emotion to occur (e.g., Lazarus 1968; Schachter and Singer 1962; Scherer 1997), and perceived intention and perceived value are the two determinations of grateful emotion that occur (Watkins 2014). Previous studies have also shown that perceived intention and value of benefits are key elements for gratitude (e.g., Bono and McCullough 2006; Toepfer et al. 2012; Tsang et al. 2008; MacKenzie et al. 2014; Weinstein et al. 2010; Wood et al. 2008; Tesser et al. 1968). Therefore, when faced with identical hypothetical situations, people higher in trait gratitude made more positive appraisals of the value of the gift and the helpers’ intentions and believed the goodness they perceived, which, in turn, led to feeling more state gratitude. Our findings lend credibility to the notion. Perceived goodness fully mediated the relationship between trait and state levels of gratitude. This suggests that perceived goodness is the generative mechanism that explains why grateful people feel more gratitude after they receive aid.

We also found that females were more grateful than males. This is in accordance with previous studies that reported that females had higher scores than males on tests of gratitude (Froh et al. 2009; Kashdan et al. 2009). This is probably because males consider the experience and expression of gratitude as evidence of vulnerability and weakness, which may threaten their masculinity and social status (Levant and Kopecky 1995). Similarly, it was reported that females were prone to have more positive appraisals of the gift and helper than their male counterparts. The gender differences identified herein seem to be consistent with the socialization hypothesis. It is suggested that the traditional female gender role prescribes affiliation and emotional expressiveness (Ptacek et al. 1992; Rosario et al. 1988). Conversely, the traditional male role prescribes attributes such as autonomy, self-confidence, and assertiveness. Such attributes make it difficult for men to recognize the goodness of gifts or benefactors. In addition, the final model did not differ by gender, indicating that males and females have the same mechanism underlying the relationship between trait and state gratitude.

Some limitations of the present study must be mentioned. First, the study’s correlational cross-sectional structure prevents drawing any causal relationships among the variables. Future longitudinal or experimental studies should address this issue and facilitate evaluation of the causal mechanisms. Second, the data in this study were gathered only through self-reported scales. The use of multiple methods (e.g., peer reports) may reduce limitations imposed by the subjectivity of self-reporting. Finally, scholars have suggested that gratitude may be associated with positive affect (e.g., Watson and Naragon-Gainey 2010). Thus, affective state should be measured and controlled to exclude its possible associations with gratitude in future research.

Conclusions and Suggestions

Despite these limitations, there are a few important contributions from this study. The current study substantially extended our insight into a complicated interplay among trait gratitude, perceived intention, perceived value, and state gratitude among Taiwanese people. The findings provide external validity for the perceived intention- and perceived value-mediated model in Taiwan, underscoring the key role of perceived intention and perceived value. In other words, this study is an expansion of gratitude theory and research to another cultural setting (i.e., Taiwan). Moreover, the significant path from trait gratitude through perceived intention and perceived value to state gratitude sheds light on the underlying mechanisms between trait and state gratitude. Although vignette studies such as the current study have fallen out of favor in recent years because of questions about subjects’ ability to make judgments in imagined scenarios, it is believed that this methodology still has a role to play in gratitude research. Because appraisals can be carefully controlled in vignette studies in ways that cannot be controlled in studies that use actual benefits, this methodology will still prove to be useful (Wood et al. 2008).

Of note, value and genuine helpful intention have been found to naturally group together and may in turn be part of a gratitude schema. It is not, however, clear whether the constellation of variables meets a definition of a schema, which would exist in only some people. Such a question has applied significance for the increasingly prevalent clinical interventions to increase gratitude (e.g., Seligman et al. 2005). The existence and malleability of a grateful schema would be an important consideration in therapeutically increasing gratitude. Potentially, such research could lead to a new schema-focused therapy for increasing gratitude, with associated well-being benefits.

As the epigraph by Chesterton emphasizes, gratitude is a cognitively imbued emotion, and according to Chesterton, grateful appraisals represent some of humankind’s most noble thinking (Watkins 2014). When experiencing a benefit, certain appraisals seem to be critical for gratitude to occur. Recognizing the goodness of the gift and recognizing the goodness of the helper characterize grateful thinking. With this in mind, appreciating the cognitive conditions of gratitude is important for developing treatments to enhance gratitude and further promoting individuals’ well-being and protecting individuals from maladjustment.

References

Algoe, S. B., Haidt, J., & Gable, S. L. (2008). Beyond reciprocity: Gratitude and relationships in everyday life. Emotion, 8, 425–429.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 411–423.

Arbuckle, J. L. (2003). AMOS 5.0 update to the AMOS user’s guide. Chicago: Smallwaters.

Bar-Tal, D., Bar-Zohar, Y., Greenberg, M. S., & Hermon, M. (1977). Reciprocity behavior in the elationship between donor and recipient and between harm-doer and victim. Sociometry, 40, 293–298.

Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. Oxford: International Universities Press.

Bono, G., & McCullough, M. E. (2006). Positive responses to benefit and harm: Bringing forgiveness and gratitude into cognitive psychotherapy. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 20, 147–158.

Chen, L. H., Chen, M.-Y., Kee, Y. H., & Tsai, Y.-M. (2009). Validation of the gratitude questionnaire (GQ) in Taiwanese undergraduate students. Journal of Happiness Study, 10, 655–664.

Clore, G. L., & Schnall, S. (2005). The influence of affect on attitude. In D. Albarracin, B. T. Johnson, & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), The handbook of attitudes (pp. 436–439). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cohen, A. B. (2006). On gratitude. Social Justice Research, 19, 254–276.

Dumas, J. E., Johnson, M., & Lynch, A. M. (2002). Likableness, familiarity, and frequency of 844 person-descriptive words. Personality and Individual Differences, 32, 523–531.

Emmons, R. A., & Crumpler, C. A. (2000). Gratitude as human strength: Appraising the evidence. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 19, 56–69.

Emmons, R. A., McCullough, M. E., & Tsang, J. (2003). The assessment of gratitude. In S. J. Lopez & C. R. Snyder (Eds.), Positive psychological assessment: A handbook of models of measures (pp. 327–341). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Froh, J. J., Yurkewicz, C., & Kashdan, T. B. (2009). Gratitude and subjective well-being in early adolescence: Examining gender differences. Journal of Adolescence, 32, 633–650.

Graham, S. (1988). Children's developing understanding of the motivational role of affect: An attributional analysis. Cognitive Development, 3, 71–88.

Harpham, E. J. (2004). Gratitude in the history of ideas. In R. A. Emmons & M. E. McCullough (Eds.), The psychology of gratitude (pp. 19–36). New York: Oxford University Press.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.

Kashdan, T. B., Mishra, A., Breen, W. E., & Froh, J. J. (2009). Gender differences in gratitude: Examining appraisals, narratives, the willingness to express emotions, and changes in psychological needs. Journal of Personality, 77, 691–730.

Lane, J., & Anderson, N. H. (1976). Integration of intention and outcome in moral judgment. Memory and Cognition, 4, 1–5.

Lazarus, R. S. (1968). Emotions and adaptation: Conceptual and empirical relations. In W. J. Arnold. In Nebraska symposium on motivation (Vol. 16, pp. 175–270). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Levant, R. F., & Kopecky, G. (1995). Masculinity, reconstructed. New York: Dutton.

MacKenzie, M. J., Vohs, K. D., & Baumeister, R. F. (2014). You didn’t have to do that: Belief in free will promotes gratitude. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40, 1423–1434.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39, 99–128.

Markus, H., Smith, J., & Moreland, R. L. (1985). Role of the self-concept in the perception of others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49, 1494–1512.

McCullough, M. E. (2002). Savoring life, past and present: Explaining what hope and gratitude share in common. Psychological Inquiry, 13, 302–304.

McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A., & Tsang, J. A. (2002). The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 112–127.

McCullough, M. E., Tsang, J.-A., & Emmons, R. A. (2004). Gratitude in intermediate affective terrain: Links of grateful moods to individual differences and daily emotional experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 295–309.

Ptacek, J. T., Smith, R. E., & Zanas, J. (1992). Gender, appraisal, and coping: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Personality, 60, 747–770.

Rosario, M., Shinn, M., Morch, H., & Huckabee, C. B. (1988). Gender differences in coping and social supports: Testing socialization and role constraint theories. Journal of Community Psychology, 16, 55–69.

Rosenberg, E. L. (1998). Levels of analysis and the organization of affect. Review of General Psychology, 2, 247–270.

Schachter, S., & Singer, J. E. (1962). Cognitive, social, and physiological determinants of emotional state. Psychological Review, 69, 379–399.

Scherer, K. R. (1997). Profiles of emotion-antecedent appraisal: Testing theoretical predictions across cultures. Cognition and Emotion, 11, 113–150.

Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist, 60, 410–421.

Tesser, A., Gatewood, R., & Driver, M. (1968). Some determinants of gratitude. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9, 233–236.

Toepfer, S. M., Cichy, K., & Peters, P. (2012). Letters of gratitude: Further evidence for author benefits. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13, 187–201.

Tsang, J.-A., Rowatt, W. C., & Buechsel, R. K. (2008). Exercising gratitude. In S. J. Lopez (Ed.), Positive psychology: Exploring the best in people (Vol. 2, pp. 37–53). Westport: Greenwood Publishing Company.

Watkins, P. C. (2014). Gratitude and the good life: Toward a psychology of appreciation. Dordrecht: Springer.

Watkins, P. C., Woodward, K., Stone, Y., & Kolts, R. L. (2003). Gratitude and happiness: Development of a measure of gratitude, and relationships with subjective well-being. Social Behavior and Personality, 31, 431–452.

Watson, D., & Naragon-Gainey, K. (2010). On the specificity of positive emotional dysfunction in psychopathology: Evidence from the mood and anxiety disorders and schizophrenia/Schizotypy. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 839–848.

Weiner, B., Russell, D., & Lerman, D. (1979). The cognition–emotion process in achievementrelated contexts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 1211–1220.

Weinstein, N., Dehaan, C. R., & Ryan, R. M. (2010). Attributing autonomous versus introjected motivation to helpers and the recipient experience: Effects on gratitude, attitudes, and well-being. Motivation and Emotion, 34, 418–431.

Wood, A. M., Maltby, J., Stewart, N., Linley, P. A., & Joseph, S. (2008). A social-cognitive model of trait and state levels of gratitude. Emotion, 8, 281–290.

Wood, A. M., Froh, J. J., & Geraghty, A. W. (2010). Gratitude and well-being: A review and theoretical integration. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 890-905.

Funding

This study was funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology of the Republic of China in Taiwan (Contract MOST 104–2410-H-027-020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that he/she has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.