Abstract

Gut microflora leads to production of ammonia and endotoxins which play important role in the pathogenesis of hepatic encephalopathy (HE). There is relationship between HE and absorption of nitrogenous substances from the intestines. Probiotics play a role in treatment of HE by causing alterations in gut flora by decreasing the counts of pathogen bacteria, intestinal mucosal acidification, decrease in production and absorption of ammonia, alterations in permeability of gut, decreased endotoxin levels and changes in production of short chain fatty acids. Role of gut microbiota using prebiotics, probiotics and synbiotics have been evaluated in the management of minimal hepatic encephalopathy (MHE), overt HE and prevention of HE. Many studies have shown efficacy of probiotics in reduction of blood ammonia levels, treatment of MHE and prevention of HE. However these trials have problems like inclusion of small number of patients, short treatment durations, variability in HE/MHE related outcomes utilized and high bias risk, errors of systematic and random types. Systematic reviews also have shown different results with one systematic review showing clinical benefits whereas another concluded that probiotics do not have any role in treatment of MHE or HE. Also practical questions on optimal dose, ideal combination of organisms, and duration of treatment and persistence of benefits on long term follow-up are still to be clarified. At present, there are no recommendations for use of probiotics in patients with HE.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) involves impairment of cognitive function and is common in patients with liver cirrhosis or porto-systemic shunts. Spectrum of HE varies widely from minor cognitive dysfunction to lethargy, depressed consciousness and coma. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy (MHE) is characterized by impairment of cognitive functions and affects 60 % to 80 % of patients with cirrhosis and adversely affects daily functioning and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) (Dhiman 2013).

Literature search and study selection

We searched and collected relevant literature between 1985 and 2014 from databases of Pub Med, EMBASE and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. The key words used in search were probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics combined with lactulose, gut microflora, hepatic encephalopathy, minimal hepatic encephalopathy and liver cirrhosis. Studies involving patients with MHE or overt HE were included which compared efficacy of probiotics, prebiotics or synbiotics with no therapy, placebo or other modes of treatment like lactulose, rifaximin and L-ornithine L-aspartate with assessment of clinical outcomes like serum ammonia, reversal of MHE, development of overt HE and mortality.

Gut microbiota in cirrhosis

Pathogenesis of HE has been studied in detail and one of the factor held responsible is increase in production of ammonia, endotoxins and other neurotoxins by gut microflora. Changes in fecal microbiota in patients of cirrhosis is an indirect evidence that there is increase in potential pathogenic bacteria which perpetuate inflammatory pathways and leads to increase in various cytokines which impairs cognitive function in patients of cirrhosis (Chen et al. 2011 and Liu et al. 2004). In patients of liver cirrhosis and HE Bajaj et al. (2012) have demonstrated close relation between gut microbiota, cognitive functions and inflammatory pathways. Although dysbiosis has been proved in patients of cirrhosis (Zhang et al. 2013), patients with MHE were found to have higher number of streptococci which was postulated to be linked to cognitive impairment and higher ammonia levels. Similarly in another study by Bajaj (2014) in patients with overt HE found higher number of Alcaligenaceae and Porphyromonadaceae families in patients with poor cognition. Colonic microbiota composition is different in patients of cirrhosis with poor cognitive functions and may be related to the development of overt HE (Bajaj 2014).

SIBO was found to be significantly higher in patients of cirrhosis with MHE as compared to patients without MHE (38.6 vs. 8.9 %) (Gupta et al. 2010). In another study from India, SIBO was reported in 48 % patients with MHE and 46 % with grade I-II HE compared to 16 % in those without MHE. Orocecal transit time (OCTT) was also reported to be prolonged in patients with MHE and grade I-II HE compared to patients without HE (Lunia et al. 2013).

Probiotics in patients with cirrhosis – rationale for use

Prebiotics, probiotics and synbiotics produce beneficial alterations in gastrointestinal microflora and play important role in maintaining normal healthy state (Amodio et al. 2013). Prebiotics are selectively fermented substances that cause specific alterations in both the composition and/or activity of gut microbiota. Probiotics are live microorganisms that, when ingested in adequate amounts, modify gut flora. Synbiotics are supplements that combine prebiotics and probiotics. Prebiotics, probiotics and synbiotics may be helpful in the management of HE by modulating the gut microbiota. They improve gut dysbiosis by decreasing the number of pathogenic bacteria and thereby help in improving endotoxemia, HE and liver functions (Liu et al. 2004). The proposed mechanisms of action include (a) Gut microbiota modulation may lower blood ammonia levels in portal blood by suppressing bacterial urease activity, decreasing ammonia absorption by lowering pH, decreasing intestinal permeability and by boosting nutritional status of gut epithelium (b) decrease endotoxemia and proinflammatory milieu resulting in improvement in inflammation, oxidative stress and liver disease severity (c) decrease in uptake of other toxins such as indoles, oxindoles, phenols and mercaptans (Solga 2003; Dhiman 2013). Probiotics also reduce bacterial translocation from the gut and may be a useful weapon for preventing bacterial infections (Bauer et al. 2001; Bauer et al. 2002; Chiva et al. 2002; Wiest et al. 2003). This positively affects patients with HE and MHE, where active inflammatory cascade plays a pivotal role. This concept is supported by an experimental model of MHE induced by intraperitoneal injection of thioacetamide in rats, wherein probiotics were more effective than placebo in lowering serum ammonia and endotoxin levels by normalizing the latency of brainstem auditory evoked potentials and decreasing the occurrence of MHE without differences between the patients receiving probiotics or lactulose (Jia and Zhang 2005).

Probiotics are live microorganisms that, when ingested in adequate amounts, modify gut flora. Prebiotics are selectively fermented substances that cause specific alterations in both the composition and/or activity of gut microbiota. Synbiotics are supplements that combine prebiotics and probiotics. Prebiotics, probiotics and synbiotics may be helpful in the management of HE by modulating the gut microbiota. They improve gut dysbiosis by decreasing the number of pathogenic bacteria and thereby help in improving endotoxemia, HE and liver functions (Liu et al. 2004). Prebiotics, probiotics and synbiotics maintain normal healthy state by altering gastrointestinal microflora (Amodio et al. 2013). The proposed mechanisms of action include (a) Gut microbiota modulation may lower blood ammonia levels in portal blood by suppressing bacterial urease activity, decreasing ammonia absorption by lowering pH, decreasing intestinal permeability and by boosting nutritional status of gut epithelium (b) decrease in uptake of other toxins such as indoles, oxindoles, phenols and mercaptans (c) decrease endotoxemia and proinflammatory milieu resulting in improvement in inflammation, oxidative stress and liver disease severity (Solga 2003; Dhiman 2013). Probiotics also prevent bacterial infections by reducing bacterial translocation from the gut (Bauer et al. 2001; Bauer et al. 2002; Chiva et al. 2002; Wiest et al. 2003). This positively affects patients with HE and MHE, where active inflammatory cascade plays a pivotal role. This concept has been proved by an experimental model of MHE induced by intraperitoneal injection of thioacetamide in rats, wherein probiotics were more effective than placebo in lowering serum ammonia and endotoxin levels and decreasing the occurrence of MHE (Jia and Zhang 2005).

Probiotics in the management of minimal hepatic encephalopathy and overt hepatic encephalopathy

Several studies have evaluated the role of probiotics in the management of MHE and overt HE (Table 1). Liu et al. (2004) randomized patients with MHE to receive synbiotic (probiotic and fermentable fiber), fermentable fiber alone or placebo for 30 days. Patients with MHE had significant fecal overgrowth of potential pathogenic Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus species. Treatment with synbiotic or fermentable fiber alone significantly increased the fecal content of non–urease producing Lactobacillus species, decline in blood ammonia levels and reversal of MHE in 50 % of subjects as compared to reversal rate of only 13 % in placebo group.

In another study patients with MHE were randomized to receive probiotic yogurt or no treatment for 60 days (Bajaj et al. 2008). Reversal rate of MHE was significantly higher in the probiotic group (70 % vs. 0 %). Frequency of overt HE on follow up was also significantly lower in the probiotic group than in no treatment group (0 % vs. 25 %). Ziada et al. (2013) assessed the effects of probiotics on MHE and neurometabolites using magnetic resonance spectroscopy of the brain. They randomized 90 patients to lactulose, probiotics and control groups for 4 weeks. Rate of reversal of MHE in the lactulose, probiotics and control group was 54.2 %, 53.8 % and 12 % respectively. The relative risk reduction of developing overt HE in lactulose and probiotics group was 60 % and 80 % respectively. In a study from India, 105 patients with MHE were randomized to receive lactulose, probiotics or combination of lactulose plus probiotics for 1 month (Sharma et al. 2008). Psychometric tests, P300 auditory event related potentials and venous ammonia levels improved significantly in patients treated with lactulose, probiotics and combination of lactulose plus probiotics groups after treatment. Patients treated with lactulose, probiotics and lactulose plus probiotics showed normalization of abnormal psychometry and p300 auditory event related potentials in 54.8 %, 51.6 % and 56.6 % respectively.

Another RCT from India compared lactulose, probiotics and L-ornithine L-asparatate in 160 patients with MHE for 3 months showed significant reversal of MHE in 47.5 %, 35 % and 35 % in lactulose, probiotics and L-ornithine L-asparatate groups, respectively compared to 10 % in no treatment group. In addition there was significant improvement in sickness impact profile questionnaire score and reduction in ammonia levels in all treatment groups versus no treatment group (Mittal et al. 2011).

Malaguarnera et al. (2010) reported that in patients with cirrhosis treatment with bifidobacterium combined with fructo-oligosaccharide for 60 days is as effective as lactulose for improvement in blood ammonia levels and psychometric tests.

However Saji et al. (2011) in a RCT of 43 patients found no significant changes in the parameters like arterial ammonia, evoked responses and number connection tests before and after treatment with probiotics when compared to placebo.

In a non-inferiority RCT comparing efficacy of probiotics with lactulose, Mouli et al. (2014) found MHE improvement rates and reduction in serum ammonia to be similar after 2 months of treatment in the two groups.

Probiotics in the management of minimal hepatic Encephalopathy and overt hepatic encephalopathy

Several studies have evaluated the role of probiotics in the management of MHE and overt HE (Table 1). In a randomized controlled trial Liu et al. (2004) have shown that synbiotic (probiotic and fermentable fiber), significantly increased the fecal content of non–urease producing Lactobacillus species, decline in blood ammonia levels and reversal of MHE in 50 % of subjects as compared to reversal rate of only 13 % in placebo group in 30 days. In another study by Bajaj et al. (2008) in patients with MHE, reversal rate of MHE was significantly higher in the probiotic group (70 % vs. 0 %) and frequency of overt HE on follow up was also significantly lower in the probiotic group than in no treatment group (0 % vs. 25 %). Ziada et al. (2013) assessed the effects of probiotics on MHE and neurometabolites using magnetic resonance spectroscopy of the brain. They randomized 90 patients to lactulose, probiotics and control groups for 4 weeks. Rate of reversal of MHE in the lactulose, probiotics and control group was 54.2 %, 53.8 % and 12 % respectively. In a study from India, 105 patients with MHE were randomized to receive lactulose, probiotics or combination of lactulose plus probiotics for 1 month (Sharma et al. 2008). Psychometric tests, P300 auditory event related potentials and venous ammonia levels improved significantly in patients treated with lactulose, probiotics and combination of lactulose plus probiotics groups after treatment. Another RCT from India compared lactulose, probiotics and L-ornithine L-asparatate in 160 patients with MHE for 3 months showed significant reversal of MHE in 47.5 %, 35 % and 35 % in lactulose, probiotics and L-ornithine L-asparatate groups, respectively compared to 10 % in no treatment group (Mittal et al. 2011). Malaguarnera et al. (2010) reported that in patients with cirrhosis treatment with bifidobacterium combined with fructo-oligosaccharide for 60 days is as effective as lactulose for improvement in blood ammonia levels and psychometric tests. However Saji et al. (2011) in a RCT of 43 patients found no significant changes in the parameters like arterial ammonia, evoked responses and number connection tests before and after treatment with probiotics when compared to placebo. In a non-inferiority RCT comparing efficacy of probiotics with lactulose, Mouli et al. (2014) found MHE improvement rates and reduction in serum ammonia to be similar after 2 months of treatment in the two groups.

Role of probiotics in prevention of hepatic encephalopathy

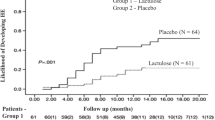

Probiotics have been evaluated for prevention of first episode of HE (primary prophylaxis) and recurrence of HE (secondary prophylaxis) (Table 2). In a randomized controlled trial of probiotics vs. no treatment in 160 patients of cirrhosis and without prior history of HE, 3 months of probiotics administration resulted in significant improvement in levels of arterial ammonia, SIBO, OCTT, psychometric hepatic encephalopathy scores and critical flicker frequency thresholds compared with baseline. 8.8 % of patients in probiotics group and 20.3 % in no treatment group developed overt HE. In patients with MHE, the absolute risk reduction was 23.8 % and number needed to treat was 4.2. To study the effects of probiotics on prevention of recurrence of HE, Agrawal et al. (2012) randomized 235 patients to lactulose, probiotics or no treatment for one year. On follow up, 26.5 % of patients in lactulose group, 34.4 % in probiotics group and 56.9 % in no treatment group developed recurrence of HE. Probiotics were better than no treatment but as effective as lactulose in preventing recurrence of HE (Dhiman et al. 2014.

Systemic reviews and meta-analyses of studies on probiotics in treatment of minimal hepatic encephalopathy and overt hepatic encephalopathy

Critical analysis of collective data from different studies may give better evidence on the status of probiotics in management of HE and MHE (Dhiman 2013). Five meta-analyses have been published so far to evaluate the effects of prebiotics, probiotics and synbiotics on outcomes in patients with HE and MHE.

In a meta-analysis by Shukla et al. (2011) on the efficacy of prebiotics, probiotics and synbiotics in the management of MHE, nine studies were included with treatment duration varying from 2 to 14 weeks. Pooled relative risk (RR) of no improvement of MHE was significantly lower with use of prebiotics, probiotics and synbiotics (RR 0.40; P < 0.001). In this meta-analysis, five studies with lactulose showed significant reduction of risk of no improvement of MHE and four trials with use of probiotics and synbiotics were associated with significant reduction of risk of no improvement of MHE. Lactulose was better than probiotics and synbiotics in efficacy but was not well tolerated compared to probiotics and synbiotics, however no serious side effects were noted.

Another meta-analysis evaluated the beneficial and harmful effects of any probiotic in any dose compared with lactulose, L-ornithine-L-aspartate, placebo or no treatment in patients of HE (McGee et al. 2011). In this meta-analysis of seven trials involving 550 subjects, randomization was done to probiotic, placebo or no treatment in four trials including 245 patients, probiotic or lactulose in one trial including 40 participants, and probiotic with both placebo and lactulose in the remaining two trials including 265 participants. When probiotics were compared with no treatment, no significant differences were found in mortality (RR 0.72), lack of recovery (RR 0.72), quality of life, adverse events (RR 0.34), or change of/or withdrawal from treatment. Significantly lower plasma ammonia concentration was found in patients treated with probiotic at one month but not at two months. Most significant decrease in plasma ammonia was noted in the participants treated with probiotic at three months. In this meta-analysis lack of recovery, adverse events, change of/or withdrawal from treatment at one month, plasma ammonia concentration, or change in plasma ammonia concentration were similar.

Another meta-analysis assessed the role of probiotics and synbiotics in HE (Holte et al. 2012). This analysis comprising seven trials with 393 patients. Treatment with probiotics or synbiotics significantly improved hepatic encephalopathy as compared to placebo or lactulose. There was no significant difference in results of psychometry tests and side effects on treatment with probiotics or synbiotics versus placebo. This meta-analysis suggested that probiotics may be an effective treatment of hepatic encephalopathy.

In another meta-analysis (Xu et al. 2014) on effects of probiotic therapy on HE in patients with cirrhosis six RCT involving 496 patients were included. Treatment with probiotics was shown to significantly reduce the development of overt hepatic encephalopathy (OR 0.42, P = 0.0007). However, probiotics therapy did not affect mortality, levels of serum ammonia and constipation.

In a meta-analysis Ding et al. (2014) compared probiotics with lactulose in MHE and showed that rate of improvement of MHE was similar between probiotics and lactulose. As per this meta-analysis probiotics and lactulose were equally effective in the improvement of MHE but probiotics were relatively more safer to use.

Conclusions

Role of prebiotics, probiotics and synbiotics have been studied in various trials but results are inconclusive. In most of these trials number of patients is small, treatment is of short duration, there is variability in the HE/MHE related outcomes, differences in diet in different countries and variability in the type/strains/dose of probiotics used. The clinical implications of the findings should be strengthened and better characterized using meticulous methodological accuracy. Systemic reviews on use of probiotics in treatment of HE conclude that there is no definite evidence that probiotics have a significant effect on improvement in HE and mortality. Therapeutic efficacy of probiotics is still uncertain and hence cannot be recommended. There is a definite need to evaluate the therapeutic effects and safety of probiotics in randomized trials with low risk of systematic and random errors. Also comparative efficacy of various probiotics and optimal doses and duration of treatment needs to be evaluated.

References

Agrawal A, Sharma BC, Sharma P, Sarin SK (2012) Secondary prophylaxis of hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhosis: an open-label randomized controlled trial of lactulose, probiotics and no therapy. Am J Gastroenterol 107:1043–1050

Amodio P, Bemeur C, Butterworth R, Cordoba J, Kato A, Montagnese S, Uribe M, Vilstrup H, Morgan MY (2013) The nutritional management of hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis: International Society for Hepatic Encephalopathy and Nitrogen Metabolism Consensus. Heoatology 58:325–336

Bajaj JS (2014) The role of microbiota in hepatic encephalopathy. Gut Microbes 5:1–7

Bajaj JS, Saeian K, Christensen KM, Hafeezullah M, Varma RR, Franco J, Pleuss JA, Krakower G, Hoffmann RG, Binion DG (2008) Probiotic yogurt for the treatment of minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol 103:1707–1715

Bajaj JS, Ridlon JM, Hylemon PB, Thacker LR, Heuman DM, Smith S, Sikaroodi M, Gillevet PM (2012) Linkage of gut microbiome with cognition in hepatic encephalopathy. Am J PhysiolGastrointest Liver Physiol 302:G168–G175

Bauer TM, Schwacha H, Steinbrückner B, Brinkmann FE, Ditzen AK, Aponte JJ, Pelz K, Berger D, Kist M, Blum HE (2001) Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in human cirrhosis is associated with systemic endotoxemia. Am J Gastroenterol 96:2962–2967

Bauer TM, Schwacha H, Steinbrückner B, Brinkmann FE, Ditzen AK, Aponte JJ, Pelz K, Berger D, Kist M, Blum HE (2002) Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in human cirrhosis is associated with systemic endotoxemia. Am J Gastroenterol 97:2364–2370

Chen Y, Yang F, Lu H, Wang B, Chen Y, Lei D, Wang Y, Zhu B, Li L (2011) Characterization of fecal microbial communities in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatology 54:562–572

Chiva M, Soriano G, Rochat I, Peralta C, Rochat F, Llovet T, Mirelis B, Schiffrin EJ, Guarner C, Balanzó J (2002) Effect of lactobacillus johnsonii La1 and antioxidants on intestinal flora and bacterial translocation in rats with experimental cirrhosis. J Hepatol 37:456–462

Dhiman RK (2013) Gut microbiota and hepatic encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis 28:321–326

Dhiman RK, Rana B, Agrawal S, Garg A, Chopra M, Thumburu KK, Khattri A, Malhotra S, Duseja A, Chawla YK (2014) Probiotics VSL #3 reduces liver disease severity and hospitalization in patients with cirrhosis: a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology 147:1327–1337

Ding X, Zhang F, Wang Y (2014) Probiotics vs. lactulose for minimal hepatic encephalopathy therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 39:1000–1001

Gupta A, Dhiman RK, Kumari S, Rana S, Agarwal R, Duseja A, Chawla Y (2010) Role of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and delayed gastrointestinal transit time in cirrhotic patients with minimal hepatic encephalopathy. J Hepatol 53:849–855

Holte K, Krag A, Gluud LL (2012) Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials on probiotics for hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatol Res 42:1008–1015

Jia L, Zhang MH (2005) Comparison of probiotics and lactulose in the treatment of minimal hepatic encephalopathy in rats. World J Gastroenterol 11:908–911

Liu Q, Duan ZP, Ha DK, Bengmark S, Kurtovic J, Riordan SM (2004) Synbiotic modulation of gut flora: effect on minimal hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 39:1441–1449

Loguercio C, Del Vecchio BC, Coltorti M (1987) Enterococcus lactic acid bacteria strain SF68 and lactulose in hepatic encephalopathy: a controlled study. J Int Med Res 15:335–343

Loguercio C, Abbiati R, Rinaldi M, Romano A, Del Vecchio BC, Coltorti M (1995) Long-term effects of enterococcus faecium SF68 versus lactulose in the treatment of patients with cirrhosis and grade 1-2 hepatic encephalopathy. J Hepatol 23:39–46

Lunia MK, Sharma BC, Sachdeva S (2013) Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and delayed orocecal transit time in patients with cirrhosis and low-grade hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatol Int 7:268–273

Lunia MK, Sharma BC, Sharma P, Sachdeva S, Srivastava S (2014) Probiotics prevent hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 12:1003–1008

Malaguarnera M, Greco F, Barone G, Gargante MP, Toscano MA (2007) Bifidobacte-riumlongumwithfructo-oligosaccharide (FOS) treatment in minimal hepatic encephalopathy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Dig Dis Sci 52:3259–3265

Malaguarnera M, Gargante MP, Malaguarnera G, Salmeri M, Mastrojeni S, Rampello L, Pennisi G, Li Volti G, Galvano F (2010) Bifidobacterium combined with fructo-oligosaccharide versus lactulose in the treatment of patients with hepatic encephalopathy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 22:199–206

McGee RG, Bakens A, Wiley K, Riordan SM, Webster AC (2011) Probiotics for patients with hepatic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 9(11):CD008716

Mittal VV, Sharma BC, Sharma P, Sarin SK (2011) A randomized controlled trial comparing lactulose, probiotics, and L-ornithine L-aspartate in treatment of minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 23:725–732

Mouli VP, Benjamin J, Singh MB, Mani K, Garg SK, Saraya A (2014) Effects of probiotic VSL#3 in the treatment of minimal hepatic encephalopathy: A non-inferiority randomized controlled trial. Hepatol Res. doi:10.11111/hepr12429

Pereg D, Kotliroff A, Gadoth N, Hadary R, Lishner M, Kitay-Cohen Y (2011) Probiotics for patients with compensated liver cirrhosis: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Nutrition 27:177–181

Saji S, Kumar S, Thomas V (2011) A randomized double blind placebo controlled trial of probiotics in minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Trop Gastroenterol 32:128–132

Sharma P, Sharma BC, Puri V, Sarin SK (2008) An open-label randomized controlled trial of lactulose and probiotics in the treatment of minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 20:506–511

Shukla S, Shukla A, Mehboob S, Guha S (2011) Meta-analysis: the effects of gut flora modulation using prebiotics, probiotics and synbiotics on minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Aliment PharmacolTher 33:662–671

Solga SF (2003) Probiotics can treat hepatic encephalopathy. Med Hypotheses 61:307–313

Wiest R, Chen F, Cadelina G, Groszmann RJ, Garcia-Tsao G (2003) Effect of lactobacillus-fermented diets on bacterial translocation and intestinal flora in experimental prehepatic portal hypertension. Dig Dis Sci 48:1136–1141

Xu J, Ma R, Chen LF, ZhaoLJ CK, Zhang RB (2014) Effects of probiotic therapy on hepatic encephalopathy in patients with liver cirrhosis: an updated meta-analysis of six randomized controlled trials. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 13:354–360

Zhang Z, Zhai H, Geng J, Yu R, Ren H, Fan H, Shi P (2013) Large-scale survey of gut microbiota associated with MHE via 16S rRNA-based pyrosequencing. Am J Gastroenterol 108:1601–1611

Ziada DH, Soliman HH, El Yamani SA, Hamisa MF, Hasan AM (2013) Can lactobacillus acidophilus improve minimal hepatic encephalopathy? A neurometabolite study using magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Arab Journal of Gastroenterology 14:116–122

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sharma, B.C., Singh, J. Probiotics in management of hepatic encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis 31, 1295–1301 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11011-016-9826-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11011-016-9826-x