Abstract

Adolescents actively evaluate their identities during adolescence, and one of the most salient and central identities for youth concerns their gender identity. Experiences with peers may inform gender identity. Unfortunately, many youth experience homophobic name calling, a form of peer victimization, and it is unknown whether youth internalize these peer messages and how these messages might influence gender identity. The goal of the present study was to assess the role of homophobic name calling on changes over the course of an academic year in adolescents’ gender identity. Specifically, this study extends the literature using a new conceptualization and measure of gender identity that involves assessing how similar adolescents feel to both their own- and other-gender peers and, by employing longitudinal social network analyses, provides a rigorous analytic assessment of the impact of homophobic name calling on changes in these two dimensions of gender identity. Symbolic interaction perspectives—the “looking glass self”—suggest that peer feedback is incorporated into the self-concept. The current study tests this hypothesis by determining if adolescents respond to homophobic name calling by revising their self-view, specifically, how the self is viewed in relation to both gender groups. Participants were 299 6th grade students (53% female). Participants reported peer relationships, experiences of homophobic name calling, and gender identity (i.e., similarity to own- and other-gender peers). Longitudinal social network analyses revealed that homophobic name calling early in the school year predicted changes in gender identity over time. The results support the “looking glass self” hypothesis: experiencing homophobic name calling predicted identifying significantly less with own-gender peers and marginally more with other-gender peers over the course of an academic year. The effects held after controlling for participant characteristics (e.g., gender), social network features (e.g., norms), and peer experiences (e.g., friend influence, general victimization). Homophobic name calling emerged as a form of peer influence that changed early adolescent gender identity, such that adolescents in this study appear to have internalized the messages they received from peers and incorporated these messages into their personal views of their own gender identity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Identity development is a hallmark of adolescence (Erikson 1968). Adolescents actively evaluate their self-views and, as a result, self-concepts may change or become more complex during the adolescent years (see Marcia 1966). Normative developmental changes in identity are presumed to be driven by increasingly sophisticated cognitive abilities, as well as by the increased complexity of social environments and relationships surrounding adolescents. Nevertheless, while some changes in identity can be considered a healthy developmental outcome, too many shifts, developments followed by regressions, or information that does not conform to an adolescent’s self-views can lead to identity challenges and may lead to confusion (Meeus et al. 1999; Yarhouse and Tan 2005). Identity challenges increase the likelihood that adolescents will experience the types of adverse shifts in identity development that may be associated with mental health concerns (e.g., depressive symptoms) or other forms of developmental maladjustment (e.g., conduct disorders; Adams et al. 2001). Thus, adolescence is an important period for identity development, and identity development is, in turn, is a critical predictor of healthy adolescent adjustment (see Meeus et al. 1999 for review). Nevertheless, few empirical studies have directly investigated the social processes involved in directing, or redirecting, identity development during adolescence. Therefore, in the present study, we focus on peer influence on gender identity using a social psychologically-based definition of gender identity that assesses how adolescents view the self in relation to social groups, particularly the middle school peer group. Understanding gender identity development and the potential for identity challenges, in particular, is critical as it may be associated with adverse developmental and mental health outcomes (Carver et al. 2003; Yunger et al. 2004).

The conceptualization of gender identity we adopt moves beyond the gender binary (“I’m a girl”) and is based on recent research suggesting a “dual identity” approach in which identity is informed by individuals’ beliefs about how the self relates to both gender groups (Martin et al. 2017a). This view draws upon social psychological research on the importance of socially-informed identity (how the self incorporates and relates to relevant groups; Tropp and Wright 2001). This conception of identity is also similar to recent broad definitions of identity proposed by an SRCD Study Group of ethnic-racial identity researchers led by Adriana Umana-Taylor and others in 2014 in which identity is viewed as “a multidimensional, psychological construct that reflects the beliefs and attitudes that individuals have about their ethnic-racial groups memberships, as well as the processes by which these beliefs and attitudes develop over time” (p. 23).

In the dual identity approach, individuals are asked how they relate to (feel similar to) both their own gender and other-gender peers. In the present study, we investigate whether a specific type of negative peer experience, known as homophobic name calling, influences adolescents’ perceptions of their own- and other-gender identity. We do this by employing social network analysis to longitudinally assess the impact of homophobic name calling on change in dual gender identities during adolescence after controlling for competing influences, such as social norms (e.g., tendency to be gender typical) and more general forms of peer victimization that may compete with the impact of homophobic name calling on adolescent adjustment and, consequently, bias results.

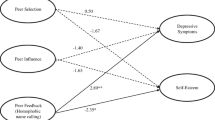

Homophobic Name Calling

Homophobic name calling is a form of peer victimization that involves contemptuous and disdainful language aimed at mocking an individual’s presumed sexual minority status and non-conforming gender expression (Horn 2007; Poteat and Espelage 2007). Like other forms of peer victimization, homophobic name calling is a social phenomenon, emerging during adolescence, and occurring within the peer group (Birkett and Espelage 2015). In general, research supports the idea that homophobic name calling is damaging to adolescent development. For example, research has demonstrated that adolescents who experience homophobic name calling show changes over time in mental health (e.g., increased depression and anxiety), social adjustment (e.g., feelings of belonging), and individual self-esteem; and such effects can be seen throughout the adolescent years (Copeland et al. 2009; DeLay et al. 2016; Lewinsohn et al. 1994; Poteat and Espelage 2007). Each of these findings points to a critical role of homophobic name calling in directing, or perhaps misdirecting, early adolescent developmental outcomes.

Homophobic name calling can be directed at heterosexual as well as at sexual minority youth (Horn 2007). Although homophobic name calling, by its nature, targets the victim’s sexual identity (e.g., gay, lesbian, etc.), for many adolescents, such comments may also be conflated with gender identity and expression. Research has shown that adolescents with non-conforming gender expression are victimized regardless of their sexual orientation (Horn 2007). However, what is unknown is whether adolescents also conflate gender and sexuality as they internalize experiences of homophobic name calling. For example, case studies suggest that some youth may question their gender identity when exploring their sexuality, or vice versa (Ehrensaft 2016), and perhaps homophobic name calling plays a role in this process. Further, the consolidation of gender identity is an important developmental process of the adolescent years, making gender identity quite salient at this time. Moreover, homophobic name calling, unlike other forms of victimization, has the potential to directly target youth’s gender identity during a critical period of development, which may alter significant aspects of adolescents’ social and emotional lives (Collier et al. 2013).

Gender Identity

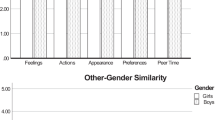

Gender identity development is a particularly important developmental outcome of the adolescent years (Egan and Perry 2001; Martin et al. 2017a). The idea that gender identity involves an evaluation of how the self relates to both gender groups is central to the dual identity perspective we adopt here (Martin et al. 2017a). The dual identity perspective builds on earlier research in which a key component of gender identity—gender typicality—involved comparisons only with one’s own gender (see Egan and Perry 2001). The dual identity view broadened this perspective by including comparisons with both gender groups. This is done by asking individuals to consider how similar they are to girls and to boys on several characteristics (also see Pauletti et al. 2017 for a similar approach).

The dual identity method of assessing how the self is seen in relation to both genders allows the possibility of finding individuals who vary across a broad spectrum of gender identities including those in which individuals claim similarities to one gender or to both genders (akin to androgyny; Martin et al. 2017b; Pauletti et al. 2017), as well as other identities in which individuals feel little or no similarity with either gender (see Martin et al. 2017a). Furthermore, we adopt the dual identity perspective because assessing how the self relates to both genders has been found to be more informative for social adjustment outcomes than assessing only similarity to one’s own gender (Martin et al. 2017a). In addition, the dual identity approach suggests that it is informative to measure both similarity to one’s own gender and to other gender peers because there may be differing pathways whereby own- and other-gender similarities begin to develop over time. Furthermore, these two components relate to binary gender labels: girls report higher similarity to girls than boys and boys show the reverse pattern; yet, they also provide a more nuanced view of identity than do binary labels (Martin et al. 2017a, b). In sum, the idea that these two components of gender identity are contributing to one’s sense of overall gender identity has been supported by findings that these two distinctive dimensions are only weakly negatively correlated, they have different developmental trajectories, and that they differentially predict outcomes (e.g., same- and other-gender friendships) (Martin et al. 2017a). Thus, to allow for a broader understanding of change in gender identity, we adopted a dual identity approach.

The Looking Glass Self: A Process by which Homophobic Name Calling May Influence Gender Identity

Little is known about whether or how homophobic name calling may influence gender identity. Thus, we propose to examine whether peer experiences, like homophobic name calling, may be incorporated into self-views so that an individual’s gender identity begins to reflect the peer feedback received. The view we have adopted is implied in a statement by Yunger et al. (2004, p. 573), “…peer interactions present children with ample opportunity to question their typicality on gender-prototypical dimensions.” Specifically, experiences of homophobic name calling may be internalized, and in doing so, adolescents may more closely align their gender identity with the names they are called (i.e., peer-perceptions become self-perceptions). Furthermore, this hypothesis builds from symbolic interaction ideas that there exists the “looking glass self” in which the self-concept comes to reflect how individuals think others perceive them (Cooley 1902; Yeung and Martin 2003). Adolescents may be particularly susceptible to this type of internalization of peer feedback, given the importance of peer relations and identity development during adolescence (Rubin et al. 2011).

To expand upon the role of the “looking glass self” in adolescent gender identity development, one can consider the following examples. Given peers’ tendency to conflate gender and sexuality, in both cases, adolescents may wonder if their gender identity and its expression provides cues that suggest a certain sexual identity or whether sexual identity may undermine their gender similarity. First, what might happen to an adolescent male who is called “gay” when he has not adopted that identity label? Even for a male adolescent sexually attracted to girls, the challenge of hearing a label that does not match his self-concept may lead to him wonder why peers think he is gay. He may begin to question his sexual identity and how his gender expression is reflective of his gender identity (in this case, the degree to which he feels similar to own-gender peers and the degree to which he feels dissimilar to other-gender peers). Second, what might happen to an adolescent lesbian who is called a homophobic name? For her and for other adolescents who label themselves as sexual minorities, the sexual label given to them by peers may match their self-label, but it may still lead to questioning how their sexual identity is signaled to their peers through their gender expression. At minimum, in both cases, the adolescent’s sense of self is challenged by peers, and that may lead to identity confusion and potentially to changes. Thus, experiences of homophobic name calling during adolescence may serve to create the kind of social context that fosters changes to one’s gender identity. If we found this pattern, it would be significant because it would suggest that peer-provided information about sexual status (through homophobic name calling) is also interpreted by adolescents as being informative about gender identity, even though the two dimensions are not identical (e.g., one can be gender non-conforming and heterosexual or gender conforming and identify as a sexual minority).

Investigating a Dynamic Peer Process Using a Longitudinal Social Network Perspective

We used longitudinal social network analysis (Ripley et al. 2016) in the current study to control for competing, and potentially confounding, social forces. These potential confounds include, but are not limited to, social network controls for social status structures (e.g., network hierarchy), selection into particular friendships and friendship groups (e.g., friendship formation), and competing peer influence processes (e.g., the influence of friends as compared to bullies). Furthermore, many of these peer network features have not previously been accounted for in empirical research on the effects of homophobic name calling in the peer group, with one exception (DeLay et al. 2016). Thus, longitudinal social network analysis was the analytic approach chosen in the current study because these social forces can only be considered simultaneously and dynamically within the context of a longitudinal social network analysis model.

To be more specific, there are three major reasons we adopted a longitudinal social network analysis framework. First, many social interactions occur around peer victimization. For example, peer victimization requires at least two members of the peer network (i.e., aggressor and victim); however, even more peers may be enmeshed in the behavior (e.g., reinforcers, bystanders) (Salmivalli et al. 1996). In this way, homophobic name calling may impact a wide range of adolescents beyond the target child. Second, longitudinal social network analysis allows for the simultaneous and dynamic consideration of multiple sources of peer influence—both positive and negative peer influence (e.g., friendships, victimization). This is an important contribution in that, for victims, having positive peer relationships (e.g., friendships) may buffer some of the risks associated with homophobic name calling from peer bullies compared to those who do not have positive friendships (Pellegrini et al. 1999). Finally, a longitudinal social network analysis approach was used because it is a dynamic modeling framework that moves beyond linear constraints of change (e.g., OLS regression; Ahn and Rodkin 2014) to allow dynamic social processes to be modeled as they unfold over time. Thus, by using longitudinal social network analysis we can assess the influence of homophobic name calling on gender identity free from the bias of false linearity that artificially constrains dynamic social processes, and we are able to assess influence as the prediction from one variable and time 1 (e.g., homophobic name calling) toward the prediction of change in another variable from time 1 to time 2 (e.g., gender identity) (Veenstra et al. 2013).

Current Study

The goal of the present study was to test the role of homophobic name calling on changes (or influence) over the course of an academic year in adolescents’ gender identity. This study extends the literature in several ways. First, we use a conceptualization of gender identity that involves assessing how similar adolescents feel to both their own- and other-gender peers. Second, we employ longitudinal social network analyses to provide a rigorous analytic assessment to examine the predictive role of homophobic name calling on changes in these two dimensions of gender identity as the process dynamically unfolds over time. To be more precise, longitudinal social network analysis using RSiena (Ripley et al. 2016) is able to account for the simultaneous impact of normative developmental change processes, selection, influence (including influence of friends and general forms of peer victimization), as well as the broader peer relationship context (e.g., hierarchies, norms) that could be confounded with influence from HNC toward change in gender identity over time. Finally, it is particularly important to note that longitudinal social network analysis also allows us to simultaneously explore both positive (e.g., friend) and negative (e.g., homophobic name calling) peer influences.

In sum, using the current analytic framework we are able to dynamically and longitudinally test the hypothesis that homophobic name calling may motivate adolescents to incorporate what they hear from their peers into their self-concepts in ways that change (or influence) their gender identity over time, while controlling for competing forms of social influence. If this hypothesis is supported, we would expect experiences of homophobic name calling to be associated with decreased own-gender similarity and increased other-gender similarity over time, suggesting movements toward incorporating messages of homophobic name calling into the self-concept. Specifically, when homophobic name calling is directed toward youth, their feelings of own-gender similarity may decrease as adolescents question whether they are targeted as being dissimilar to own-gender peers because of the way they express themselves as a function of how they act, look, or talk (e.g., for a girl, not talking like a girl), or whether homophobic names reflect more subtle cues about their gender and/or their sexuality. Also, when targeted with homophobic name calling, feelings of other-gender similarity may increase as adolescents consider whether they may share more in common with other gender peers in terms of expression (how they act, talk, or look) (e.g., for a girl, acting like a boy) or whether they have more subtle or essential commonalities with the other gender that peers are able to detect.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 299 6th grade students (53% female; M age = 11.13 years, SD age = 0.48) recruited from a middle school in the Southwestern U.S. These students represented a variety of ethnic backgrounds (37% Hispanic, 17% European American, 14% multi-ethnic, 8% Native American, 6% African American, 1% Asian American; 17% missing ethnicity data). In addition, most students qualified for free (71%) or reduced price (6%) school meals.

At Time 1, 90% of 6th grade students at the school participated in the study. Eighteen students left the school and 21 students joined the school between fall (Time 1) and spring (Time 2) data collections; this information is represented in the network composition change files used by RSiena. Chi-square and independent-samples t tests indicated no significant differences between students who remained in the network (n = 212; participated at both time points) or attrited (n = 39; participated at Time 1 but not Time 2) on any demographic (age, gender, ethnicity, SES) or study (homophobic name calling, own-gender similarity, other-gender similarity, victimization, friendship nominations made and received) variables. Sample size requirements met those necessary for longitudinal social network analysis (Ripley et al. 2016).

Procedure

After receiving IRB approval from [institution blinded for review], as well as school principal and district approval, packets with study information and consent forms were sent home with students 2 weeks prior to data collection to allow parents time to ask questions about the study and/or to opt out of the study. If parents did not consent, students were not tested. Furthermore, students with parental permission were asked to provide assent and only those who did were included in the study. Paper surveys were administered to students during the fall of their 6th grade year (Time 1), soon after their transition from elementary to middle school. Students then completed Time 2 surveys in the spring of their 6th grade year.

During each assessment, researchers administered surveys to participating 6th grade students during a 45-minute class period. Non-participating students were given an alternative task to complete by the classroom teacher. These surveys included measures of participants’ gender identity and peer relationships. A research assistant read aloud all items and response options to aid with reading difficulties and to help ensure the survey was completed on time. Each class consisted of approximately 30 students, and three to four research assistants were available to aid participants during the assessment. All students in the classroom were given a small gift upon completion of the survey.

Measures

Demographics

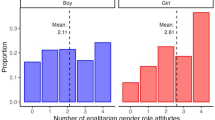

Students reported their gender by responding to the question “are you a girl, boy, or other?” (recoded into 1 = girl and 0 = boy) and ethnicity (recoded into 0 = non-Latino and 1 = Latino). We obtained paid lunch status from the school (1 = free or reduced and 2 = paid), which was used as a proxy for SES.

Peer network nominations

To capture the complete 6th grade peer affiliation network, students completed nominations of the 6th grade students they would “most like to spend time with.” To aid in name recollection and to help ensure that students only nominated peers within the selected network, participants were given a list of all 6th grade students at their school from which to select these peers.

Gender identity (similarity to own- and other-gender peers)

Students reported their own- and other-gender identity using a scale created by Martin et al. (2017a). This is a 10-item scale that is intended to tap into feelings of similarity to gender groups by including the items “How similar do you feel to [boys/girls]?” and “How much do you act like [boys/girls]?” Responses were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 = not at all to 5 = a lot. Students responded to all items about boys and about girls, means were calculated, and responses were recoded into own- and other-gender identity responses (5 items for each). Observed reliabilities were α = .77 at Time 1 and .81 at Time 2 for own-gender similarity, and α = .70 and .78 for other-gender similarity at Time 1 and Time 2.

Conducting longitudinal social network analysis in RSiena requires the use of categorical dependent variables; because own- and other-gender similarity were the dependent variables for this study, scores on these variables were transformed from continuous scores to categorical variables. We examined the distribution for each variable and determined cutoff scores for each category based on the shape of the distributions; eight categories for each variable were identified such that the analysis would identify incremental but meaningful change in own- or other-gender similarity.

Homophobic name calling

Students reported the degree to which they had experienced homophobic name calling using an item adapted from the Homophobic Content Agent Target Scale (HCAT; Poteat and Espelage 2005; see Collier et al. 2013). This item was “Some kids call each other names such as gay, homo, or lesbian. How many times in the last month did anyone call you these names?” Students responded on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never or almost never, 2 = 1 or 2 times, 3 = 3 or 4 times, 4 = 5 or 6 times, 5 = 7 or more times). However, because the distribution of this variable was highly positively skewed, we recoded their responses into two categories (1 = never or almost never and 2 = 1 or more times).

General peer victimization

To assess the degree to which students were victimized by their peers, we administered a modified version of the Early Adolescent Role Strain Inventory (Fenzel 1989). This is a 4-item scale including the items “How often do other students exclude you from activities,” “How often are other students mean to you,” “How often do other students push or hit you,” and “How often do other students make fun of you.” Students responded on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 = never or almost never to 5 = always or almost always. Reliability for this measure was α = .77 at Time 1 and α = .83 at Time 2.

Analytic Plan

The purpose of this study was to determine whether students’ experience of homophobic name calling contributed to a change in their own- or other-gender identity over the 6th grade year. To do this, we used longitudinal social network analysis to isolate the effect of homophobic name calling on gender identity from the effects and processes associated with the peer network. Specifically, we estimated the effect of homophobic name calling on own- and other-gender identity after controlling for network, behavioral, and model fit parameters; selection and influence effects on own- and other-gender identity; and students’ level of other types of peer victimization.

To analyze the peer network within RSiena, we created a matrix of peer nomination data that included all possible members of the specified network. Values indicated whether an affiliative nomination was made or not made for each pair of students. We also created a composition change file that included information about students who left or joined the network between Time 1 and Time 2. Last, we created covariate and dependent variable files that included the data for students’ gender, ethnicity, SES, victimization, homophobic name calling, own-gender similarity, and other-gender similarity.

Network controls

We included three network control parameters in the model to account for basic characteristics of the peer affiliation network: outdegree, reciprocity, and transitive triplets. Outdegree accounts for selectivity in peer nominations made. Reciprocity accounts for the tendency for peer nominations to be mutual, or reciprocal. Transitive triplets accounts for, as an example, the tendency of friends of friends to also be friends, a kind of transitive closure effect. In addition, we controlled for similarity, ego, and alter effects for each covariate (e.g., gender). Gender similarity represents a tendency to nominate own-gender peers; gender ego indicates that gender influences the number of peer nominations made by an individual; and gender alter indicates whether an individual’s gender influences the number of peer nominations they received. We also controlled for similarity, ego, and alter effects for homophobic name calling and gender similarity.

Behavioral controls

Two control parameters were included to account for the characteristics of the distributions of the dependent variables (own- and other-gender similarity). Linear tendency indicates a tendency toward individuals reporting mostly high or mostly low values on the dependent variables. Quadratic shape accounts for the tendency for overdispersion or regression toward the mean on the dependent variables. We also controlled for the effects of model covariates (gender, ethnicity, SES, and victimization) on the dependent variables.

Goodness of fit controls

In addition to the network and behavioral control effects used in most longitudinal social network analysis models (Veenstra et al. 2013), we conducted goodness of fit tests, which are designed to reliably match the model specification to the particular social network under investigation (Ripley et al. 2016). This is done to help ensure accuracy in model estimation, as well as to provide additional information regarding the social dynamics embedded within a particular network of interest. This procedure, therefore, improves model accuracy and minimizes estimation bias.

Goodness of fit tests indicated that the following control parameters should be included in our model to account for characteristics of our 6th grade peer affiliation network: transitive reciprocated triplets type 2, transitive ties, number of actors at distance 2, dense triads, geometrically weighted edgelist shared partners, indegree-related popularity, and reciprocal degree-related activity. These control parameters were each included in our final model.

Selection effects

To help ensure that the observed change in the dependent variables was due to the effect of homophobic name calling, we also controlled for selection effects for similarity to peers on own- and other-gender similarity. These effects represent the tendency for individuals to select peers who are similar to themselves in their levels of own- or other-gender similarity.

Influence effects

Similar to including selection effects on the dependent variables, we controlled for influence effects for own- and other-gender similarity. Specifically, we included average similarity influence effects for own- and other-gender similarity to indicate the degree to which individuals become more similar to their connected peers on levels of own- and other-gender similarity. We also controlled for the influence of general peer victimization on changes in levels of own- and other-gender similarity.

Homophobic name calling effects

The goal of the present study was to examine the effect of homophobic name calling on changes in individuals’ own- and other-gender similarity during the 6th grade year. To do this, we evaluated this effect after controlling for structural characteristics and social processes of their peer network. Specifically, we included the effect of homophobic name calling on both own-gender similarity and other-gender similarity. These indicate the degree to which initial levels of homophobic name calling led to a change in own- or other-gender similarity over the 6th grade year.

Tests of moderation

We also sought to determine whether gender moderated the effect of homophobic name calling on changes in own- and other-gender similarity. To examine this, we included interaction effects of gender on the homophobic name calling own- and other-gender similarity influence effects. Other exploratory interaction effects included gender × selection, gender × influence, homophobic name calling × selection, and homophobic name calling × influence, indicating the degree to which the effect of selection and influence varied by gender and level of homophobic name calling.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics of peer network and study variables are presented in Table 1. Students nominated an average of 7 peers at Time 1 and 9 peers at Time 2 as those they most like to spend time with. The total number of network ties increased from fall to spring, indicating that students had formed more relationships (on average) over the academic year. The Jaccard index indicated that the stability of ties in this network over time was .25, which is within the acceptable range for estimating social network models (Snijders et al. 2010). Eighteen students left the network and 21 joined the network between Time 1 and Time 2. These individuals were included in the analyses, and their missing data were accounted for in the model. The longitudinal dependent variables were also somewhat stable over time, (own-gender similarity r = .63, other-gender similarity r = .67, see Table 1, which are within the acceptable range for analysis).

Longitudinal Social Network Analysis

Parameter estimates for basic network and behavioral control effects, as well as influence effects of homophobic name calling, peer influence effects, and general victimization effects are found in Table 2. All estimates presented in Table 2 were obtained after first controlling for Goodness of Fit estimates. The specific goodness of fit parameters that were added to the model as control variables are found in Table 3.

Network controls

The outdegree parameter was negative and significant, indicating that students were selective in their peer nominations (Snijders et al. 2010). The reciprocity parameter indicated that students were more likely to make mutual, or reciprocal, nominations than one-sided nominations. The transitivity parameter indicated that students were more likely to nominate friends of their friends. Individuals also nominated more own-gender than other-gender peers.

Behavioral controls

The linear tendency effect for own-gender similarity was positive and significant, indicating that individuals were more likely to report high levels of own-gender similarity. In addition, boys reported higher levels of own-gender similarity and lower levels of other-gender similarity than did girls.

Goodness of fit controls

All goodness of fit parameters (transitive reciprocated triplets type 2, transitive ties, number of actors at distance 2, dense triads, geometrically weighted edgelist shared partners, indegree-related popularity, and reciprocal degree-related activity) added to improve model fit were significant (see Table 3 for details). The final estimates of primary interest (see Table 2) are presented with the adjustments that were made to the model after the inclusion of goodness of fit parameters (see Table 3).

Selection effects

The selection effects for similarity on own- and other-gender similarity were not significant, meaning that there was no evidence that students selected peers that were similar to themselves in levels of own- or other-gender similarity.

Peer influence and general victimization effects

There were no significant peer influence effects for own- or other-gender similarity. This indicates that students did not become more similar to the peers they nominated in levels of own- or other-gender similarity between Time 1 and Time 2. There was no significant general peer victimization influence effect for own- or other-gender similarity. This indicates that general peer victimization did not predict change in levels of own- or other-gender similarity between Time 1 and Time 2.

Homophobic name calling effects

Homophobic name calling contributed to changes in both own- and (marginally) other-gender identity over the 6th grade year. After the inclusion of Model Fit (goodness of fit control parameters), the effect of homophobic name calling on own-gender identity continued to be significant, moving from p = .01, OR = 1.036 before goodness of fit control parameters to p = .02, OR = 1.037 after goodness of fit control parameters; and the effect of homophobic name calling on other-gender identity dropped from significant (p = .04, OR = 1.027) before goodness of fit control parameters to a trend level estimate (p = .07, OR = 1.026) after goodness of fit control parameters (because of a slight increase in the standard error from .09 to .10). The criteria were met for good model fit for longitudinal social network analysis in RSiena in the final model presented (Ripley et al. 2016). In sum, the results supported the hypothesis, with students who had experienced higher levels of homophobic name calling reporting feeling significantly less similar to their own-gender and marginally more similar to the other-gender over time.

None of the gender or homophobic name calling interaction effects were significant. Thus, it can be determined that gender did not moderate the relation between homophobic name calling and own- and other-gender identity. Furthermore, neither gender nor homophobic name calling appear to have an impact on basic friend selection and friend influence processes. Nonsignificant effects, including nonsignificant interaction effects, were omitted from Table 2 only to add clarity in the presentation of results.

Discussion

As children transition from childhood to adolescence, consolidation of identity is an important developmental process that will inform trajectories for personal growth and longer-term adjustment. Therefore, an understanding is needed of how the social context of the adolescent years, particularly positive and negative peer experiences, contribute to the development of identity. In this study, we focused on a particular peer process—homophobic name calling—that may be associated with changing a particular form of early adolescent identity—gender identity. The results yield insights into how the social context of middle school influences the development, and potential developmental shifts, of early adolescent gender identity.

The results illustrate that—even after controlling for structural features of the adolescent peer network (e.g. social hierarchies, social norms), positive peer relationships (e.g., liked peers, mutual friends), and general forms of peer victimization (e.g., being bullied by any peer for any reason)—homophobic name calling at the onset of middle school emerged as a form of peer influence that predicted change in early adolescent gender identity from the fall to the spring of the 6th grade academic year. Specifically, support was found for the symbolic interaction hypothesis, such that adolescents appear to have reflected (i.e., the “looking glass self” hypothesis) upon how others perceived them and to shift their identities accordingly (Cooley 1902; Yeung and Martin 2003). That is, adolescents in this study appear to have internalized the messages they received from peers and incorporated these messages into their personal views of their own gender identity.

In contrast to internalizing of peer messages, an alternative view is that negative reactions from peers could elicit greater conformity to norms (Ewing Lee and Troop-Gordon 2011a, b); in this case, experiences of homophobic name calling might re-shape an adolescent’s gender identity by minimizing non-conforming (relative to the peer group) feelings or expressions of gender identity. In this view, when behaviors are punished, or responded to negatively, these reactions should effectively decrease the behaviors. However, if adolescents were so influenced in the present study, we would have observed a shift toward less non-conforming identities, and more conforming identities; but this is not the pattern illustrated in the present results. Nevertheless, we did not specifically test adolescents’ behaviors, so it may still be the case that homophobic name calling changes an adolescent’s identity as we found, but that the adolescent would also externally behave in a more conforming way in the presence of peers. Further testing is needed to explore this interesting idea. Although movement toward conformity does not apply to gender identity under the influence of homophobic name calling, this view may have merit in other circumstances (e.g., peer pressures to conform to normative adolescent health risk behaviors). Interestingly, the present results suggest that, in the case of homophobic name calling and gender identity, adolescents use peers as a source of insight about how they might understand their identity rather than as a source of information about how to change externally malleable behaviors toward peer normative levels.

Interestingly, homophobic name calling influenced both own-gender similarity and other-gender similarity. However, own-gender similarity was more strongly influenced in that it remained significantly impacted by homophobic name calling even after all controls were included in the longitudinal social network analysis model. Nevertheless, adolescents who experienced homophobic name calling reported both reduced feelings of being similar to their own gender and marginally increased feelings of being similar to other-gender peers. The differential influence on these two types of gender identity in the present study, although modest in impact, supports the dual identity perspective (Martin et al. 2017a).

Theoretical and Empirical Contributions

Peer influence, through rewarding normative behaviors (gender typical behaviors) and punishing non-conforming behaviors (gender non-conforming behaviors), has been previously documented in gender development studies with young children (e.g., Fagot 1977; Langlois and Downs 1980). However, it is intriguing that, in a study of adolescents, this same type of influence does not appear to be effective in bringing about conformity to peers on gender identity. Instead, adolescents moving into middle school appear to consider homophobic name calling to be informative about their identities, using this information to readjust their self-views in accordance with the peer feedback received. More specifically, support for the symbolic interaction hypothesis may have been primarily found because the current investigation involved an internal feeling of identity rather than an overtly expressed behavior (e.g., alcohol use). Thus, it seems reasonable that the mechanisms behind peer influence over more internal processes, like gender identity, may operate differently than peer influence over more overt behaviors like, for example, adolescent alcohol use. To bring clarity to this distinction between influence over internal identity vs. overt behavioral profiles, we consider the following examples.

First, consider an adolescent who wears gender non-conforming clothing (an overt expression). In this case, if peers call the adolescent homophobic names, it may be clear to the adolescent why he/she is being victimized (e.g., peers do not like individuals wearing gender non-conforming clothing). However, in other instances, homophobic name calling may or may not relate to any particular characteristic or feature of the adolescent at all (Poteat and Espelage 2007). In this case, questions may arise in the mind of the adolescent concerning what specific behaviors brought about the homophobic name calling. It follows that, if victims of homophobic name calling cannot identify an overt behavior that they believe was the cause of the victimization (e.g., a style of walking, hairstyle, etc.), they may instead question whether there is something about their gender identity (an internal process) that peers can “sense” or “perceive” even though they themselves cannot. In this way, for an adolescent target of homophobic name calling, the peer-perception of an adolescent being gender non-conforming could become incorporated as a self-perception. It is in this way that homophobic name calling may heighten mental health risks by challenging the self-concept. Furthermore, even in an example where an adolescent targeted for homophobic name calling is quite confident in knowing why they were targeted for homophobic name calling, the features that are targeted for homophobic name calling may themselves be unchangeable (e.g., sexual orientation), or the adolescent may not wish to change (e.g., haircut, clothing). In these instances, it again seems reasonable that the response to homophobic name calling may be a confirmation, or a strengthening of, feelings of gender non-conformity, rather than acceptance of peer pressure toward gender conformity. Thus, the looking-glass self-view of identity development through internalization of social feedback can be seen as a more likely outcome of homophobic name calling than changes brought about through pressures to conform to peer norms.

The present findings supporting the looking glass self suggest the need for a deeper exploration of how homophobic name calling can cause problems. Is homophobic name calling a problem because it is targeted name calling, or is it the match or mismatch between homophobic name calling and an adolescent’s identity? If homophobic name calling is a problem because it is a form of victimization, then we would expect it to be no more influential than other forms of victimization. However, we found that homophobic name calling was more influential than general peer victimization, at least as it relates to influence over gender identity. This suggests that homophobic name calling carries more or at least a different influential force when compared to general peer victimization. Nevertheless, further research is needed to more precisely test these ideas. Another possibility is homophobic name calling becomes problematic when there is a mismatch between homophobic name calling and identity. For adolescents who are cisgender heterosexual youth or for sexual minority youth who have yet to realize or label themselves as such, being targeted with homophobic name calling might be particularly confusing. However, contrast that with an adolescent who is assured of his or her sexual minority identity; for that adolescent, hearing homophobic name calling may be hurtful but would not disconfirm or challenge their self-identity. Identity confusion and negative outcomes would seem more likely for the former groups than for the latter one.

Questions also arise about broader developmental issues. During these early adolescent years, youth are refining their sense of who they are on many dimensions, including gender identity, and they may shift depending on the kinds of peer feedback they receive. Do the shifts that we detected in gender identity due to negative peer treatment happen for other identities that adolescents are refining, such as ethnic identity? Broader questions about how these shifts occur and for whom, are intriguing. For example, we do not yet know if all adolescents respond to peers in the ways we found in the current study. Further, we do not know how extensively adolescents may modify their self-views based on particular forms of peer feedback, such as homophobic name calling. The factors that may contribute to individual differences in these changes, such as self-assurance, conformity, and clarity of self-identity, are fascinating and important questions for future research.

Finally, it is important to note that we may have detected a significant impact of homophobic name calling on gender identity particularly because of the developmental period of focus in the current study and this may not be the case for younger or older youth. Early adolescence, the focus of the current study, may be a particularly sensitive period for gender identity influence and consequent developmental shifts for a variety of reasons. For example, during early adolescence, youth begin to redefine themselves in the peer group and, at the same time, peer perceptions and peer relationships become increasingly important and impactful (Vitaro et al. 2009). Forming positive and supportive peer relationships is critical to adolescent well-being and overall happiness (van Workum et al. 2013). Adolescents constantly evaluate where they fit in the peer group and why they fit. In this way, adolescents continually engage in an active process of self- and other-evaluation. The goal of this evaluation process is to ultimately obtain friendships, or supportive peer relationships, with similar others in the peer group (Weisz and Wood 2005). Because a clear understanding of identity and self-concept can support friendship formation, targeted victimization that shifts and confuses one’s self-views (e.g., gender identity) can inhibit the development of these positive and supportive peer relationships.

Analytic Contributions

These findings also provide important analytic contributions. For example, this is the first study we know of to examine the impact of homophobic name calling on gender identity using longitudinal social network analysis to simultaneously control for several individual difference factors, peer influence process, and additional social dynamics, including peer norms and general forms of peer victimization that could bias study results. Thus, we found that homophobic name calling affected adolescents’ gender identity even after controlling for influence by friends, social status structures in the peer group, social norms and trends, and other types of victimization. The ability for longitudinal social network analysis to capture the complex individual and social features of adolescent peer networks during periods of developmental change and transition is a major benefit of adopting this analytic approach and makes longitudinal social network analysis useful in understanding how social processes impact child and adolescent development. Therefore, although the effects may have been somewhat small in magnitude, these effects were obtained from very rigorous statistical models in which numerous competing influences and developmental processes were simultaneously accounted for and controlled.

Applications of longitudinal social network analysis, like the one presented here, also open the door to understanding how and why homophobic name calling develops in the social context of the early adolescent peer group. Questions of who is most vulnerable to this type of victimization, as well as who is most likely to use homophobic name calling as a tool to victimize others represent worthy candidates for future research in a longitudinal social network analysis framework. Such network models can be used to differentiate between the most likely victims and the most likely perpetrators of homophobic name calling. Information on who bullies whom may then be able to be used in the planning for intervention and prevention efforts. Such efforts stand to not only support victimized youth but may also provide useful information on ways to change the social milieu of the stressful period of youths’ early middle school years. The advantages of this approach are clear: changing a peer network has potential to create large scale change, rather than only targeted change among the most “at-risk” individuals.

Future Directions and Study Limitations

This investigation has several limitations. First, additional attention is needed on the measurement of homophobic name calling. For instance, the current study adopts a single-item scale and, although this scale has been demonstrated to be valid through its use in previous research on homophobic name calling (e.g., Collier et al. 2013; Poteat and Espelage 2005), it would be useful to assess the reliability of these assessments using a multi-item report. Furthermore, future research could explore whether the type of name(s) that adolescents are called matter; that is, whether some names are more destructive than others. Second, because of the age of the youth we did not assess their sexual attraction. However, to better understand how homophobic name calling may lead to confusion and possibly shifts in identity, it would be useful to know about other identities beyond gender, such as sexual orientation, and to monitor both of these to assess any potential changes over time. Third, the current study was not able to test complex questions of moderation at the network level due to limitations in statistical power. For example, we do not know if homophobic name calling effects will hold across more or less diverse middle school samples, across variable cultural and national contexts, or across various peer group structures (e.g., dominant social hierarchies vs. egalitarian networks). Therefore, future research might collect similar data among larger samples of networks (e.g., more schools and more diverse schools) to investigate such questions of moderation. School policy is another important moderator to consider. School policies (if executed effectively) can serve to set a level of expectation for peer interactions and perhaps even provide information on levels of tolerance that may either expand or constrain positive and negative social dynamics in the peer network. Each of these potential moderators are important to consider, and offer innovative directions for future research. Finally, longer term measurement of social networks and important developmental outcomes could offer new insights into the cause and consequence of homophobic name calling during early adolescence. Given the present study design, we can only speculate about what leads youth to call their peers homophobic names. Not all youth who experienced homophobic name calling have an overt non-conforming gender identity expression and not all youth who experience homophobic name calling are sexual minority youth (Horn 2007); this suggests that homophobic name calling is a pervasive social phenomenon during early adolescence that should be better understood. Given its impact, homophobic name calling requires serious consideration and study to better address the healthy development of gender majority and gender minority youth.

Conclusions

Although a number of studies have examined homophobic name calling in adolescents (Horn 2007; Poteat and Espelage 2007), the current study focused on how this form of negative peer experience influence changes in adolescents’ gender identity using longitudinal social network analyses because this method allowed for rigorous controls. The results demonstrated that, even after controlling for participant characteristics (e.g., sex), social network features (e.g., norms), and peer experiences (e.g., friend influence, general victimization), homophobic name calling emerged as a significant form of peer influence on young adolescents. In particular, adolescents appear to have internalized the messages they received from peers and incorporated these messages into their personal views of their own gender identity. Specifically, youth who experienced homophobic name calling early in the school year were more likely by the end of the year to report feeling less like their own gender and marginally more like the other gender. Thus, the current findings are supportive of symbolic interaction perspectives—the “looking glass self”—that suggests that peer feedback is incorporated into the self-concept (Cooley 1902). Although it has long been known that peer relationship experiences are important for healthy adolescent development, the current study further documents that peer experiences also have a critical role in predicting gender identity shifts. Understanding the role of homophobic name calling on influencing shifts in gender identity provides insights into the developmental and social factors that contribute to identity formation for important and salient social categories.

References

Adams, G. R., Munro, B., Doherty-Poirer, M., Munro, G., Petersen, A. M. R., & Edwards, J. (2001). Diffuse-avoidance, normative, and informational identity styles: Using identity theory to predict maladjustment. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 1, 307–320. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532706xid0104_01.

Ahn, H. J., & Rodkin, P. C. (2014). Classroom-level predictors of the social status of aggression: Friendship centralization, friendship density, teacher-student attunement, and gender. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106, 1144–1155. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036091.

Birkett, M., & Espelage, D. L. (2015). Homophobic name calling, peer-groups, and masculinity: The socialization of homophobic behavior in adolescents. Social Development, 24, 184–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12085.

Carver, P. R., Yunger, J. L., & Perry, D. G. (2003). Gender identity and adjustment in middle childhood. Sex Roles, 49, 95–109. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024423012063.

Collier, K. L., Bos, H. M. W., & Sandfort, T. G. M. (2013). Homophobic name calling among secondary school students and its implications for mental health. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42, 363–375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9823-2.

Cooley, C. H. (1902). Human nature and the social order. New York: Scribner’s.

Copeland, W. E., Shanahan, L., Costello, E. J., & Angold, A. (2009). Childhood and adolescent psychiatric disorders as predictors of young adult disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66, 764–772. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.85.

DeLay, D., Hanish, L. D., Zhang, L., & Martin. C. L. (2016). Assessing the impact of homophobic name calling on early adolescent mental health: A longitudinal social network analysis of competing peer influence effects. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45, doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0598-8

Egan, S. K., & Perry, D. G. (2001). Gender identity: A multidimensional analysis with implications for psychosocial adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 37, 451–463. https://doi.org/10.1037//0012-1649.37.4.451.

Ehrensaft, D. (2016). The gender creative child: Pathways for nurturing and supporting children who live outside gender boxes. New York: The Experiment.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis (No. 7). New York: WW Norton & Company.

Ewing Lee, E. A., & Troop-Gordon, W. (2011a). Peer processes and gender role development: Change s in gender atypicality related to negative peer treatment and children’s friendships. Sex Roles, 64, 90–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9883-2.

Ewing Lee, E. A., & Troop-Gordon, W. (2011b). Peer socialization of masculinity and femininity: Differential effects of overt and relational forms of peer victimization. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 29, 197–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-835X.2010.02022.x.

Fagot, B. I. (1977). Consequences of moderate cross-gender behavior in preschool children. Child Development, 48, 902–907. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1977.tb01246.x.

Fenzel, L. M. (1989). Role strain in early adolescence: A model for investigating school transition stress. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 9, 13–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431689091003.

Horn, S. S. (2007). Adolescents’ acceptance of same-sex peers based on sexual orientation and gender expression. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36, 363–371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-006-9111-0.

Langlois, J. H., & Downs, A. C. (1980). Mothers, fathers, and peers as socialization agents of sex-typed play behaviors in young children. Child Development, 51, 1237–1247.

Lewinsohn, P. M., Clarke, G. N., Seeley, J. R., & Rohde, P. (1994). Major depression in community adolescents: Age at onset, episode duration, and time to recurrence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 33, 714–722. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199407000-00006.

Marcia, J. E. (1966). Development and validation of ego-identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3, 551–558. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0023281.

Martin, C. L., Andrews, N. C. Z., England, D. E., Zosuls, K., & Ruble, D. N. (2017a). A dual identity approach for conceptualizing and measuring children’s gender identity. Child Development, doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12568

Martin, C. L., Cook, R., & Andrews, N. C. Z. (2017b). Reviving androgyny: A modern day perspective on flexibility of gender identity and behavior. Sex Roles, 76, 592–603. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0602-5.

Meeus, W., Iedema, J., Helsen, M., & Vollebergh, W. (1999). Patterns of adolescent identity development: Review of literature and longitudinal analysis. Developmental Review, 19, 419–461. https://doi.org/10.1006/drev.1999.0483.

Pauletti, R. E., Menon, M., Cooper, P. J., & Perry, D. G. (2017). Psychological androgyny and children’s mental health: A new look with new measures. Sex Roles, 76, 705–718. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0627-9.

Pellegrini, A. D., Bartini, M., & Brooks, F. (1999). School bullies, victims, and aggressive victims: Factors relating to group affiliation and victimization in early adolescence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91, 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-0663.91.2.216.

Poteat, V. P., & Espelage, D. L. (2005). Exploring the relation between bullying and homophobic verbal content: The homophobic content agent target (HCAT) scale. Violence and Victims, 20, 513–528. https://doi.org/10.1891/088667005780927485.

Poteat, V. P., & Espelage, D. L. (2007). Predicting psychosocial consequences of homophobic victimization in middle school students. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 27, 175–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431606294839.

Ripley, R., Snijders, T. A. B., Boda, Z., Voros, A., & Preciado, P. (2016). Manual for RSiena (version Nov 30, 2016). Oxford: University of Oxford, Department of Statistics, Nuffield College. http://www.stats.ox.ac.uk/siena/.

Rubin, K. H., Bukowski, W. M., & Laursen, B. (Eds.) (2011). Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups. New York: Guilford Press.

Salmivalli, C., Lagerspetz, K., Björkqvist, K., Österman, K., & Kaukiainen, A. (1996). Bullying as a group process: Participant roles and their relations to social status within the group. Aggressive Behavior, 22, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1098-2337(1996)22:1<1::aid-ab1>3.0.co;2-t.

Snijders, T. A. B., van de Bunt, G. G., & Steglich, C. E. G. (2010). Introduction to stochastic actor-based models for network dynamics. Social Networks, 32, 44–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2009.02.004.

Tropp, L. R., & Wright, S. C. (2001). Ingroup identification as the inclusion of ingroup in the self. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 585–600.

van Workum, N., Scholte, R. H. J., Cillessen, A. H. N., Lodder, G. M. A., & Giletta, M. (2013). Selection, deselection, and socialization processes of happiness in adolescent friendship networks. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 23, 563–573. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12035.

Veenstra, R., Dijkstra, J. K., Steglich, C., & van Zalk, M. H. W. (2013). Network-behavior dynamics. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 23, 399–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12070.

Vitaro, F., Boivin, M., & Bukowski, W. M. (2009). The role of friendship in child and adolescent psychosocial development. In K. H. Rubin, W. M. Bukowski & B. Laursen (Eds.), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups (pp. 568–585). New York: Guilford.

Weisz, C., & Wood, L. F. (2005). Social identity support and friendship outcomes: A longitudinal study predicting who will be friends and best friends 4 years later. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 22, 416–432. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407505052444.

Yarhouse, M. A., & Tan, E. S. (2005). Addressing religious conflicts in adolescents who experience sexual identity confusion. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 36, 530–536. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.36.5.530.

Yeung, K. T., & Martin, J. L. (2003). The looking glass self: An empirical test and elaboration. Social Forces, 81, 843–879. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2003.0048.

Yunger, J. L., Carver, P. R., & Perry, D. G. (2004). Does gender identity influence children’s psychological well-being? Developmental Psychology, 40, 572–582. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.40.4.572.

Funding

This research was supported by funding from the T. Denny Sanford School of Social and Family Dynamics.

Authors' Contributions

D.D. conceived of the study, performed the statistical analyses and interpretation of the results, and led the writing of the manuscript. C.M. contributed to the conceptualization and writing of the study. R.C. assisted in data analysis, writing of the manuscript, and reviewed drafts. L.H. assisted in the conceptualization of the study and reviewed drafts. D.D., L.H., and C.M. oversaw implementation and administration of the larger study from which the data are drawn. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

DeLay, D., Lynn Martin, C., Cook, R.E. et al. The Influence of Peers During Adolescence: Does Homophobic Name Calling by Peers Change Gender Identity?. J Youth Adolescence 47, 636–649 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0749-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0749-6