Abstract

This study investigated tenth- and twelfth-grade adolescents’ (N ≤ 264) judgments about the acceptability of same-sex peers who varied in terms of their sexual orientation (straight, gay or lesbian) and their conformity to gender conventions or norms in regard appearance and mannerisms or activity. Overall, the results of this study suggest that adolescents’ conceptions of the acceptability of their peers are related not just to sexual orientation but also conformity to gender conventions. Both straight and gay or lesbian individuals who were non-conventional in their appearance and mannerisms were rated as less acceptable than individuals who conformed to gender conventions or those who participated in non-conventional activities. Most surprisingly, for boys, the straight individual who was non-conforming in appearance was rated less acceptable than either the gay individual who conformed to gender norms or was gender non-conforming in choice of activity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recent research on the development of peer harassment and discrimination, indicates that with the onset of puberty, harassment and discrimination that is related to sexuality becomes much more prevalent and is often directed at same-sex peers (AAUW, 2001; Bochenek and Brown, 2001; Craig et al., 2001; Gay et al., 2001). Moreover, individuals tend to be more biased and hold more negative attitudes toward gay or lesbian individuals of their same gender (Herek, 1988). Understanding the basis of this discrimination is of interest to the study of social development, and critical to efforts to ameliorate the incidence of exclusion and harassment in school settings. The purpose of the present research was to address one set of factors within this very complex topic. The study reported here explored the role that non-conformity to gender-based conventions of dress, mannerisms, and activities may play in heterosexual adolescents’ acceptance of same-sex homosexual peers. Prior work has demonstrated that as children move into adolescence gender conventions become much more salient and limiting, and adherence to these norms becomes much more important (Eder, 1985; Eder et al., 1995).

It would seem then, that as individuals are trying to figure out their own sexual and gender identity in adolescence, they are also policing their peers regarding this process. While it may be the case that some students might use outwardly hostile teasing and harassment in sanctioning their same-sex peers, it is not the case that a majority of students engage in these hurtful kinds of behaviors (Horn and Nucci, 2003). Instead, a more prevalent form of social monitoring and social sanction in adolescence comes in the form of social acceptance (Underwood, 2004). That is, it could be the case that adolescents’ perceive exclusion as a legitimate way to socially regulate individuals whose personal attributes or identity expressions fall outside of what is considered acceptable according to social norms regarding gender and sexuality.

A growing body of research on children and adolescents’ social reasoning suggests that individuals draw upon their knowledge about fairness, their understanding of the functions of social conventions, and their sense of autonomy and personal choice when justifying or condemning acts of social exclusion (Horn, 2003; Horn et al., 1999; Killen et al., 2002a, b, 2005). This research implies that acts of social exclusion result from the weighing of multiple factors ranging from judgments about the personal prerogatives of individuals to associate with whomever they please, to moral judgments about the harm caused by systematic social exclusion (see Kille et al., 2005, for a comprehensive review). Middle adolescence is a period when young people first come to understand that social conventions such as dress norms, and social manners serve to coordinate the social behaviors of members of social systems (Turiel, 1983; Nucci et al., 2004). Prior to this period, children tend to view conventions as simply the arbitrary standards of adult society. This insight into the social functions of convention, however, comes with a degree of rigidity regarding the acceptability of conduct that violates group conventions (Turiel, 1983). Thus, one might anticipate that middle adolescents would place considerable weight on adherence to gender-based conventions when applied to a judgment of whether or not to accept or exclude a same-sex peer.

The literature on gender development and peer harassment in adolescence would suggest that social norms regarding gender and sexuality are particularly salient during this age period (AAUW, 2001; Craig et al., 2001; Eder et al., 1995; Shakeshaft et al., 1995). In the majority of high schools in the United States the prevailing norm regarding sexuality is heterosexuality and adolescents are socialized, both informally and formally, toward heterosexual behaviors and relationships (Blumenfield, 1992; Kimmel and Mahler, 2003; Mandel and Shakeshaft, 2000). While some schools have made strides to be more welcoming and accepting of youth who express or exhibit same-sex attractions, heterosexuality is still portrayed as the only legitimate form of sexuality in most schools. The recent legislation promoting abstinence only until marriage sexuality education, that defines sex as intercourse between a man and woman, is one example of the privileging of heterosexuality and the denial or silencing of homosexuality (Fine, 1993; Friend, 1993; Waxman Report, 2003;Weis and Carbonell-Medina, 2000).

Additionally, beginning in early adolescence throughout young adulthood, gender norms and conventions regarding behavior, interests, and appearance are quite strong (Eder, 1985; Alfieri et al., 1996). In a series of studies on early adolescents’ judgments of others based on gender conformity, Lobel and colleagues (Lobel, 1994; Lobel et al., 1993; Lobel et al., 1999) found that cross-gender behavior in individuals was judged harshly by adolescents, particularly for boys. Further, there is some evidence to suggest that in adolescence cross-gender behavior is seen as maladaptive and that individuals who exhibit “non-normative” behavior regarding gender appearance, activities, or preferences are often sanctioned by both peers and adults (Carr, 1998; Carter and Patterson, 1982; Martin, 1990; Plummer, 2001; Stoddart and Turiel, 1985).

Further, individuals who fall outside the range of what is considered acceptable for their gender in terms of mannerisms, appearance, or activities are often the targets of much ridicule, teasing, and harassment from their peers (Eder et al., 1995; Kimmel and Mahler, 2003; Lobel, 1994; Lobel et al., 1993; Lobel et al., 1999). Additionally, research with adolescents on homophobia and anti-gay prejudice suggest that anti-gay attitudes are in place by early adolescence (Baker and Fishbein, 1998; Mandel and Shakeshaft, 2000) and that individuals who hold conventional beliefs about gender roles are more likely to be prejudiced and less likely to befriend a gay or lesbian person (Marsiglio, 1993). Moreover, a growing body of literature on sexual minority youth and risk speculates that much of the stigma and victimization faced by sexual minority youth is related to gender-atypicality (Russell, 2003; Savin-Williams and Ream, 2003).

While all of this previous work indicates that conformity to gender-based conventions has an impact on attitudes toward same-sex peers, no research to date has investigated the interaction of sexual orientation and gender non-conformity on adolescents’ acceptance of their peers. Thus, it is unclear from this prior work to what extent the acceptance of same-sex gay or lesbian peers is a function of their being homosexual, as opposed to their conformity or lack of conformity to gender-based conventions of appearance, mannerisms, or choice of activities. The present study addressed this gap in the research literature by exploring the impact of gender non-conformity on the acceptability of heterosexual as well as gay or lesbian same-sex peers.

Current study and hypotheses

Heterosexual male and female tenth- and twelfth-grade adolescents were asked to evaluate the acceptability of same-sex heterosexual or homosexual peers varying in terms of their conformity to social norms regarding gender expression (gender conforming or gender non-conforming in forms of mannerisms and appearance or activity). Because research on sexual prejudice (Herek, 1988) suggests that sexual prejudice is more frequently direct toward same-sex individuals we chose to investigate judgments of acceptability toward same-sex peers only. Further, research on sexual harassment in adolescence also suggests that sexual harassment directed toward same-sex peers is quite strong in adolescence (Craig et al., 2001).

Based on prior research on social exclusion, it was anticipated that the majority of adolescents would maintain modulated positions with respect to the notion of social acceptance based on sexual identity or gender expression (Horn, 2003; Killen et al., 2002a). Within that framework of relative tolerance, however, it was expected that heterosexual adolescents would be more likely to evaluate a gay or lesbian same-sex peer who violated norms for gender expression as less acceptable than such a peer who adhered to these gender conventions. For example, it was expected that heterosexual males would be more likely to evaluate a gay peer who wore makeup and fingernail polish as less acceptable than a gay peer who dressed in a manner consistent with the conventions of male attire. It was also anticipated, however, that the same pattern would apply to evaluations of same-sex heterosexual peers. What was unclear, however, was whether gender expression would outweigh sexual identity in acceptability scores accorded to heterosexual, and gay or lesbian same-sex target figures. No hypotheses were made, for example regarding whether male adolescents would rate a gender convention conforming gay peer more acceptable than a gender convention non-conforming straight peer.

Prior work (Killen et al., 2002a) has indicated that there is an age-related tendency to employ conventional reasoning (social harmony, group norms) to justify social exclusion, and that the use of such justifications tends to peak in middle adolescence (Horn, 2003), and to decline thereafter. Further, research on the development of conventional knowledge (Turiel, 1983), as well as research on peer conformity in adolescence, provides evidence that peer conformity peaks during this age period. Middle adolescents (ages 14–16 years) are more likely to affirm and adhere to group conventions unilaterally than older adolescents, who are more likely to see these conventions and norms as more flexible and less rigid. As a result, older adolescents are more able to integrate their conventional knowledge with their understanding of fairness, harm, and personal prerogative or individual rights (Nucci, 2001). Based on this research, it was expected that tenth-graders would be more likely than twelfth-graders to focus upon conventions and social expectations in considering the acceptability of gay or lesbian, gender non-conforming peers.

Finally, based on prior work by Lobel and colleagues (Lobel, 1994; Lobel et al., 1995), it was anticipated that males would be less accepting overall of same-sex gay peers than females would be of lesbian peers. Females were also expected to provide higher acceptability ratings than males for same-sex peers who violated gender conventions regardless of sexual orientation.

Summary of hypotheses

-

heterosexual adolescents would be more likely to evaluate a gay or lesbian, as well as straight same-sex peer who violated norms for gender expression as less acceptable than such a peer who adhered to these gender conventions.

-

heterosexual adolescents would be more likely to evaluate gay or lesbian peers as less acceptable than straight peers.

-

tenth-graders would be more likely than twelfth-graders to focus upon conventions and social expectations in considering the acceptability of gay or lesbian, gender non-conforming peers.

-

males would be less accepting overall of same-sex gay peers than females would be of lesbian peers. Females were also expected to provide higher acceptability ratings than males for same-sex peers who violated gender conventions regardless of sexual orientation.

Method

Participants

Participants were 109 male and 155 female tenth- and twelfth-grade students attending a public high school located in a suburb contiguous with a large Midwestern city (tenth: 44 male, 75 female [M age = 15.6]; twelfth: 65 male, 80 female [M age=17.6]. Five of the boys (4.6%) and ten of the girls (6.5%) self-identified as gay/lesbian or bisexual. Sexual identity was determined by students’ responses to the following question, “Which of the following do you consider yourself to be?” Students could choose “Bisexual,” “Gay male,” “Lesbian,” or “Straight.” The percentage of students in our sample who identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual was similar to those found in others studies which indicate that three to five percent of high school students report either same-sex attractions or self-identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual (for a review of this literature, see Cianciotto and Cahill, 2003). Because the study focused upon the perceptions of heterosexual adolescents, data from gay, lesbian, and bisexual students were not included in the analyses. Additionally, three students did not complete the acceptability measure, thus, the sample for the statistical analyses was comprised of 246 students (Males, N=103; Female, N=143).

The school from which the sample was drawn was economically and ethnically diverse. Median family income was $56, 338 with 31.3% of students from low-income families as determined by the 2004 Illinois state school report card. Participants in the study were African American (23%); Asian American (4%); Bicultural (6%); European American (55%); Latino/a (5%) and other (7%). The demographic distribution of the sample paralleled that of the school. The data were collected during the 2001–2002 academic year in the spring semester. Participants were recruited from the required tenth-grade health or twelfth-grade social studies classes (psychology, sociology, philosophy). Twelfth-grade students were from 13 different sections of the classes taught by a number of different teachers. Tenth-grade students were from ten sections of health taught by two of the three health teachers. Only those students receiving parental permission (58%) were surveyed. Those students who did not return the parental permission form (41%)Footnote 1 or were not given permission to participate (1%) completed an alternate questionnaire comprised of educational games during administration to protect the anonymity of those students participating in the study.

Procedure

Participants completed the questionnaire in their required classes. Prior to being given the questionnaire, participants were told that their responses to the questionnaire were confidential and anonymous, that their participation was voluntary, and that they could decide to choose to stop at any time. Additionally, the research assistant asked that they fill out the questionnaire as completely as possible and students were told that there were no right or wrong answers to the questions; that we were simply interested in what they thought about these issues. The questionnaire administration took approximately 45 min. Once all students had completed the questionnaire, the researcher answered any questions they had regarding the study.

Measures

The questionnaire had two parts.Footnote 2 The questions on Part I of the questionnaire referred to demographic information about the participants (gender, grade, ethnicity, age). Part II of the questionnaire assessed participants’ evaluations of the acceptability of heterosexual and homosexual same-sex peers who varied in terms of gender expression. Target figures included an individual who was gender conforming as well as figures who violated gender conventions in terms of appearance/mannerisms or choice of activity.

Participants were presented with a series of descriptions of individuals who were either gay or straight, and gender conforming or non-conforming in appearance/mannerisms, and/or choice of extracurricular activity. Table 1 presents a complete set of the scenarios used. The scenarios were developed based on extensive pilot interviews with college students that included measures of sensitivity and reasoning regarding each of the targets. Based on these interviews, the configuration of scenarios for the current study was chosen because they evoked clean and discrete responses from participants. In the current study male participants were presented with scenarios depicting male target figures, and females were presented scenarios depicting females. Participants were asked to rate each target individual on a scale from 1 to 5 in terms of “your view of their acceptability” (1 = not acceptable at all; 3 = neither acceptable nor unacceptable; 5 = totally acceptable).

Results

Each participant rated the acceptability of three straight and three gay/lesbian target peers (conforming, appearance/mannerisms non-conforming, activity non-conforming). Adolescents’ ratings of the different targets were analyzed using a 2 (Grade: tenth, twelfth) X 2 (Gender: male, female) X 6 (Target: straight, gender conforming; gay, gender conforming; straight, gender appearance non-conforming; gay, gender appearance non-conforming; straight, gender activity non-conforming; gay, gender activity non-conforming) repeated measures analysis of variance test (ANOVA). The main effect for grade approached significance, F (1, 242)=3.09, p < .08. Twelfth grade participants tended to give higher acceptability ratings than tenth graders (12th grade: M = 4.51, S.D.=.06; 10th grade: M = 4.34, S.D.=.07). However, there were no significant interactions between grade and either gender or peer target. Thus, the grade effect appears to be due to a general increase in acceptance of others, rather than to specific shifts in attitudes toward peers based on either sexual orientation, or gender expression.

The analysis also revealed a significant main effect for gender, F (1, 242) = 5.09; p < .05. Overall, males provided lower acceptance ratings of same-sex peers than did females (Males: M=4.31, S.D. .07; Females: M=4.52, S.D. .06). There was also a main effect for target, F (1, 242)=49.07, p < .0001, and a target X gender interaction, F (1, 242)=4.73, p < .01. There were no other significant interactions.

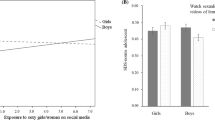

Table 2 presents heterosexual male and female participants mean acceptability ratings for each peer target. These data are also depicted graphically for males in Fig. 1, and for females in Fig. 2. The effects for peer target and the gender X target interaction were explored through post-hoc pair-wise t-tests with a Bonferroni adjustment to account for family-wise error. This set the critical p < .001. As can be seen in Fig. 1, these analyses indicated that as expected heterosexual males rated the straight peer who conformed to gender conventions as more acceptable than a peer who violated activity norms (participated in ballet). The straight male peer who violated activity norms was in turn rated as more acceptable than a straight male peer who violated norms of dress and mannerisms (e.g., wore lipstick and fingernail polish). Males also rated the gender conforming gay male peer higher than a gay male peer who violated gender-based norms of appearance and mannerisms. There was no significant difference, however, in ratings given to the gender conforming gay male peer and the gay male peer in violation of gender-typed activity conventions (participated in ballet). The acceptability ratings of the gay male peer participating in ballet, were, however, significantly higher than ratings of the gay male peer who violated norms of appearance and mannerisms.

Comparisons between ratings given by male participants to gay and straight peers indicated that the gender convention conforming straight male peer was rated higher in acceptability than all of the gay male peer targets, including the gender convention conforming gay male peer. The gender convention conforming gay male peer was, however, rated equally as acceptable as the activity non-conforming straight male peer, and more acceptable than the appearance and mannerisms non-conforming straight male peer. Indeed, the least acceptable targets were the straight and gay male peers described as non-conforming in mannerisms and dress. There was no significant difference in the ratings accorded these non-conforming peers as a function of sexual orientation.

As illustrated in Fig. 2, female participants rated the straight female peer who conformed to gender conventions as more acceptable than a female peer who violated gender-based activity norms (e.g., participated in football). As was the case with males, the straight female peer who violated activity norms was in turn rated as more acceptable than a straight female peer who violated norms of dress and mannerisms (e.g., has a crew cut, never wears dresses). Also, like the males, the female participants rated the gender conforming lesbian peer higher than the lesbian peer who violated norms of appearance and mannerisms. There was no significant difference in ratings given to the conforming lesbian peer and the lesbian peer who violated activity norms. Again, as was the case for males, the females rated the lesbian peer who violated activity norms higher in acceptability than the lesbian peer who violated conventions for appearance and mannerisms.

Comparisons between ratings given by female participants to lesbian and straight peers indicated that the gender convention conforming straight female peer was rated higher in acceptability than all of the lesbian peer targets, including the gender convention conforming lesbian peer. Female participants rated the gender convention conforming lesbian peer as acceptable as the activity non-conforming straight peer, and the appearance and mannerisms non-conforming straight peer. Unlike the case with males, however, the gender convention conforming lesbian peer was not rated higher than any of the non-conforming straight female peers.

Discussion

The results of this study provide evidence that heterosexual adolescents employ concepts about social convention related to gender conformity as well as sexual orientation in evaluating the acceptability of same-sex gay and lesbian peers. Thus, the study adds to the growing literature indicating that adolescent attitudes toward gender-based conventions play a significant role in judgments of the acceptability of peers (Eder, 1985; Eder et al., 1995; Stoddart and Turiel, 1985), as well as literature which suggests that gender non-conformity is a risk factor in the victimization of GLB youth (Diamond and Savin-Williams, 2003; Russell, 2003; Savin-Williams and Mahler, 2003). For both males and females, as predicted non-compliance with gender-based conventions was associated with lower levels of acceptability. Importantly, this held for judgments directed at heterosexual as well as gay and lesbian same-sex peers. Although heterosexual peers generally received higher acceptability ratings than their gay or lesbian counterparts, this trend did not always hold for comparisons between gay or lesbian peers described as conforming to gender conventions, and straight peers described as violating such gender conventions. This indicates that attitudes toward gay and lesbian same-sex peers, involve an integration of concepts about sexual orientation, and gender convention rather than being based upon a one-dimensional attitude toward sexual orientation.

The importance of attending to the independent contribution of adolescent attitudes about sexual orientation, and their concepts of gender convention was highlighted by the finding that gay male targets who were gender-conforming were rated as more acceptable than straight male targets who violated gender norms regarding appearance and mannerisms. This finding is consistent with previous reports indicating that males in particular place importance upon compliance with gender norms (Kimmel, 1994; Kimmel and Mahler, 2003; Lobel, 1994; Lobel et al., 1995). These results also suggest that norms regarding the expression of gender may be more salient than sexual orientation per se in individuals’ perceptions of and attitudes toward their peers, and provides additional empirical support for the idea that homophobia and heterosexism also include elements of sexism and are harmful to all students regardless of their sexual orientation (Kimmel and Maher, 2003; Pharr, 1992; Russell, 2003; Stein, 1995).

Interestingly, targets who violated gender norms in regard to physical appearance were evaluated as less acceptable than targets who violated gender norms in regard to activity suggesting that gender norms regarding physical attributes and appearance may be more rigid in adolescence than gender norms regarding the types of activities in which girls and boys can participate. This held for straight as well as gay or lesbian targets. One explanation of this is that adolescents may see physical attributes as more salient to gender identity than participation in certain activities. This explanation would be supported by Stoddart and Turiel’s study (1985) in which they found that adolescents judged gender norm violations as wrong because of the perception that this indicated a deviant gender identity and was maladaptive.

This finding could also be due, however, to the increased number of adolescents participating in activities typically dominated by opposite-gender peers that has resulted, in part, from Title IX and the equal access act. For example, as more and more girls participate in sports of all kinds and as women’s athletics gain in popularity, the norms regarding participation in predominantly male-dominated sports (such as football) become less rigid and engaging in these activities becomes more acceptable. While these norms may be less rigid, however, they are not completely gone, as evidenced by the finding that adolescents in the present study evaluated same-sex peers who participated in non-conventional activities as less acceptable than adolescents participating in gender-normative activities.

One of the study hypotheses was that older participants would hold less rigid positions with respect to gender conventions. Thus, it was hypothesized that twelfth-graders would provide higher ratings than tenth-grade participants for non-conforming peers relative to conforming peers. This was based on the assumption that the younger tenth-grade participants were at an age in which adolescents typically maintain a relatively rigid conception of the importance of adherence to conventional norms (Turiel, 1983). However, what was observed was that older participants in the present study provided higher ratings across the board. Thus, it wasn’t possible to disaggregate what may have been a function of developmental changes in concepts about convention, from a more general tendency toward acceptance of peers with age.

The findings of this study have provocative implications for further research on peer exclusion, and peer harassment based upon sexual orientation. The results indicate that attitudes toward gay and lesbian peers may not be based solely on sexual orientation, but rather from judgments about perceived tendencies to engage in forms of expression that run counter to gender conventions. This will be important not only to the design of basic research on social prejudice and exclusion, but will also have implications for educational approaches to reduce prejudice and harassment of gay and lesbian students. Recent work (Horn, 2003) on adolescents’ reasoning about social exclusion based on adolescent peer group membership has found that age-related differences in adolescents’ judgments were related to the development of social conventional reasoning rather than to developmental differences in perceptions of fairness or an ethic of tolerance. Thus, in designing programs to reduce prejudice directed at gay and lesbian students, attention should be paid not only to variations in sexuality, but also to issues related to social customs and conventions associated with gender expression.

Recent reports of the school climate for gay and lesbian youth report that between 60–95% of such youth have experienced some kind of harassment or violence in school and that there are few interventions by teachers, school staff, or other students in these situations (GLSEN, 1999, 2001; Bochenek and Brown, 2001; Russell et al., 2001). Additionally, reports suggest that the average student hears anti-gay slurs about 16 times a day, or once every half hour (GLSEN, 2001). Surely this is an area of adolescent life experience that warrants attention from educators and the research community. The results of this study make a contribution toward filling a considerable gap in our knowledge about the ways in which adolescents evaluate and reason about such issues based on gender expression and sexual orientation. Further, the results provide some interesting evidence to suggest that peer evaluations based on conformity to gender conventions may not only be harmful to sexual minority students but also potentially harmful to students who fall outside the traditional boundaries of what is considered normative gender behavior.

Notes

Because we were not allowed to obtain any demographic information on the students who did not return permission forms we were unable to compare this group to the participants in the study. Additionally, we don’t know if the students not returning their forms simply forgot about it or selected themselves out of the study for some other reason. In classes in which teachers required that students return the form as part of their course participation the response rate was close to 100%. In classes where this was not the case the response rate was typically lower than 30%. While this may suggest that a majority of students simply neglected to return their form, it is possible that some students selected themselves out for other reasons, thus, our sample may be biased toward individual students and families who are more accepting of same-sex sexualities.

This study is part of a larger study investigating adolescents’ beliefs about homosexuality, their attitudes toward gay and lesbian peers, and their evaluations of the treatment of others based on gender expression and sexual orientation. For additional reports from this study (see Horn and Nucci 2003; Horn, 2004). For a copy of the complete questionnaire, contact the author.

References

American Association of University Women (2001) Hostile hallways: Bullying, teasing, and sexual harassment in school. American Association of University Women Educational Foundation, Washington, D.C

Alfieri T, Ruble D, Higgins T (1996) Gender stereotypes during adolescence: Developmental changes and the transition to junior high school. Dev Psychol 32:1129–1137

Baker J, Fishbein H (1998) The development of prejudice towards gays and lesbians by adolescents. J Homosex 36:89–100

Blumenfield WJ (1992) Squeezed into gender envelopes. In: Blumenfeld WJ (ed) Homophobia: How we all pay the price. Beacon, Boston, MA, pp. 23–38

Bochenek M, Brown A (2001) Hatred in the hallways: Violence and discrimination against lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender students in U.S. schools. Human Rights Watch, New York

Carr CL (1998) Tomboy resistance and conformity: Agency in social psychological gender theory. Gender Soc 12:528–553

Carter DB, McCloskey LA (1983–1984) Peers and the maintenance of sex-typed behaviors: The development of children’s conceptions of cross gender behavior in their pees. Soc Cognit 2:294–314

Carter DB, Patterson C (1982) Sex-roles as social conventions: The development of children’s conceptions of sex-role stereotypes. Dev Psychol 18:812–824

Cianciotto J, Cahill S (2003) Education policy: Issues affecting lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute, New York

Craig WM, Peplar D, Connolly J, Henderson K (2001) Developmental context of peer harassment in early adolescence: The role of puberty and the peer group. In: Juvonen J, Graham S (eds) Peer harassment in school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized. Guilford Press, New York, pp. 242–262

Eder D (1985) The cycle of popularity: Interpersonal relations among female adolescents. Sociol Educ 58:154–165

Eder D, Evans C, Parker S (1995) School talk: Gender and adolescent’s culture. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, NJ

Fine M (1993) Sexuality, schooling, and adolescent females: The missing discourse of desire. In: Weis L, Fine M (eds) Beyond silenced voices: Class, race and gender in United States schools. State University of New York Press, Albany, pp. 75–100

Friend RA (1993) Choices, not closets: Heterosexism and homophobia in schools. In: Weis L, Fine M (eds) Beyond silenced voices: Class, race and gender in United States schools. State University of New York Press, Albany, pp. 209–235

Gay, Lesbian, Straight Education Network (1999) National school climate survey. Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network, New York

Gay, Lesbian, Straight Education Network (2001) National school climate survey. Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network, New York

Herek G (1988) Heterosexuals’ attitudes toward lesbians and gay men: Correlates and gender differences. J Sex Res 25:451–477

Horn SS (2003) Adolescents’ reasoning about exclusion from social groups. Dev Psychol 39:71–84

Horn SS (2004) Adolescents’ peer interactions: Conflict and coordination among personal expression, social norms, and moral reasoning. In: Nucci L (ed) Conflict, contradiction, and contrarian elements in moral development and education. Erlbaum, Mahwah, New Jersey

Horn SS, Killen M, Stangor CS (1999) The influence of group stereotypes on adolescents’ moral reasoning. J Early Adolesc 19:98–113

Horn SS, Nucci LP (2003) The multidimensionality of adolescents’ beliefs about and attitudes toward gay and lesbian peers in school. Equity Excell Educ 36:1–12

Killen M, Lee-Kim J, McGlothlin H, Stangor C (2002a) How children and adolescents evaluate gender and racial exclusion. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev 67 (4, Serial No. 271)

Killen M, Margie NG, Sinno S (2006) Morality in the context of intergroup relationships. In: Killen M, Smetana J (eds) Handbook for moral development. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc, Hillsdale, New Jersey, pp. 155–183

Killen M, McGlothlin H, Lee-Kim J (2002b) Between individuals and culture: Individuals’ evaluations of exclusion from social groups. In: Keller H, Poortinga Y, Schoelmerich A (eds) Between biology and culture: Perspectives on ontogenetic development. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England

Kimmel MS (1994) Masculinity as homophobia: Fear, shame, and silence in the construction of gender identity. In: Brod H, Kauffman M (eds) Theorizing masculinities. Sage series on men and masculinities, vol 5. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Kimmel MS, Mahler M (2003) Adolescent masculinity, homophobia, and violence: Random school shootings, 1982–2001. Am Behav Sci 46:1439–1458

Lobel T (1994) Gender typing and the social perception of gender stereotypic and nonstereotypic behavior: The uniqueness of feminine males. J Pers Soc Psychol 66:379–385

Lobel T, Bempechat J, Gewirtz J, Shoken-Topaz T, Bach E (1993) The role of gender-related information and self-endorsement of traits in preadolescents inferences and judgments. Child Dev 64:1285–1294

Lobel T, Gewirtz J, Pras R, Shoeshine-Rokach M, Ginton R (1999) Preadolescents’ social judgments: The relationship between self-endorsement of traits and gender-related judgments of female peers. Sex Roles 40:483-498

Mandel L, Shakeshaft C (2000) Heterosexism in middle schools. In: Lesko N (ed) Masculinities at school. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA

Marsiglio W (1993) Attitudes toward homosexual activity and gays as friends: A national survey of heterosexual 15- to 19-year-old males. J Sex Res 30:12–17

Martin CL (1990) Attitudes and expectations about children with traditional and non-traditional gender roles. Sex Roles 22:151–165

Nucci L (1996) Morality and the personal sphere of actions. In: Reed E, Turiel E, Brown T (eds) Values and knowledge. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc, Hillsdale, NJ, pp. 41–60

Nucci L (2001) Education in the moral domain. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

Nucci L, Becker K, Horn S (2004, June) Assessing the development of adolescent concepts of social convention. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Jean Piaget Society, Toronto, CA

Pharr S (1992) Homophobia as a weapon of sexism. In: Rothenberg PS (ed) Race, class, and gender in the US: An integrated study. St. Martin’s, New York, pp. 431–440

Plummer D (2001) The quest for modern manhood: Masculine stereotypes, peer culture and the social significance of homophobia. J Adolesc 24:15–23

Russell ST (2003) Sexual minority youth and suicide risk. Am Behav Sci 46:1241–1257

Russell S, Franz B, Driscoll A (2001) Same-sex romantic attraction and experiences of violence in adolescence. Am J Public Health 91:903–906

Shakeshaft C, Barber E, Hergenrother MA, Johnson Y, Mandel L, Sawyer J (1995) Peer harassment in schools. In: Curcio JL, First FF (eds) Journal for a just and caring education. Corwin Press, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 30–44

Stein N (1995) Sexual harassment in school: The public performance of gendered violence. Harv Educ Rev 65:145–162

Stoddart T, Turiel E (1985) Children’s concepts of cross-gender activities. Child Dev 56:1241–1252

Underwood M (2004) Social aggression among girls. Guilford Press, New York

Waxman Report (2004) The content of federally funded abstinence -only education programs. Retrieved, April 21, 2005 from http://www.democrats.reform.house.gov/Documents/20041201102153-50247.pdf

Weis L, Carbonell-Medina D (2000) Learning to speak out in an abstinence-based sex education group: Gender and race work in an urban magnet school. In: Weis L, Fine M (eds) Construction sites: Excavating race, class, and gender among urban youth. The teaching for social justice series. Teachers College Press, New York, pp. 26–49

Acknowledgments

The research reported in this article was supported, in part, by grants from the Wayne F. Placek Fund of the American Psychological Foundation and a University of Illinois at Chicago Campus Research Board awarded to the author and Larry Nucci.

I would like to thank Larry Nucci for his help and feedback on the manuscript. Additionally, I thank Jessica Rosenwein, Anna Kurtz, and Mary Kachiroubas for assistance with data collection and data entry.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Associate professor of Educational Psychology and Human Development in the College of Education at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Her research interests are peer exclusion and harassment in adolescence and the ways in which adolescents apply their social and moral knowledge to understanding these issues. Additionally, Dr. Horn is interested in school climate issues for gay, lesbian, and gender non-conforming youth and is currently conducting an evaluation of a school based program aimed at reducing anti-gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender violence. She is particularly committed to bringing research-based evidence to bear on issues related to creating safe schools for gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender youth. Her research has been published in journals such as Developmental Psychology and the Journal of Early Adolescence.

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10964-007-9176-4.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Horn, S.S. Adolescents’ Acceptance of Same-Sex Peers Based on Sexual Orientation and Gender Expression. J Youth Adolescence 36, 363–371 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-006-9111-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-006-9111-0