Abstract

Positive youth development is thought to be essential to the prevention of adolescent risk behavior and the promotion of thriving. This meta-analysis examined the effects of positive youth development interventions in promoting positive outcomes and reducing risk behavior. Ten databases and grey literature were scanned using a predefined search strategy. We included studies that focused on young people aged 10–19 years, implemented a positive youth development intervention, were outside school hours, and utilized a randomized controlled design. Twenty-four studies, involving 23,258 participants, met the inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis. The impact of the interventions on outcomes including behavioral problems, sexual risk behavior, academic achievement, prosocial behavior and psychological adjustment were assessed. Positive youth development interventions had a small but significant effect on academic achievement and psychological adjustment. No significant effects were found for sexual risk behaviors, problem behavior or positive social behaviors. Intervention effects were independent of program characteristics and participant age. Low-risk young people derived more benefit from positive youth development interventions than high-risk youth. The studies examined had several methodological flaws, which weakened the ability to draw conclusions. Substantial progress has been made in the theoretical understanding of youth development in the past two decades. This progress needs to be matched in the intervention literature, through the use of high-quality evaluation research of positive youth development programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

During adolescence, young people must negotiate complex and inter-related biological, cognitive, emotional and social-cultural changes. Problem behaviors including substance misuse, risky sexual behaviors, school dropout, antisocial attitudes and violence increase during early adolescence (e.g., Dryfoos 1990) and can lead to greater likelihood of negative behaviors into adulthood. Early adolescence is therefore an important time to intervene and influence the trajectory of an individual’s cognitive, social, emotional and cultural development and their risk behavior. Positive youth development interventions encompass these two overarching aims. Such programs need to be sensitively designed to capitalise upon the plasticity that characterizes this developmental period and address the unique challenges inherent in adolescence. As Tolan et al. (1995, p 579) note, “Intervention designs informed by this model emphasise developmentally appropriate components, sensitivity to the impact of timing of intervention, and evaluation of the impact on future development as well as curtailing or preventing the target symptoms”. It is the above features that may contribute to the potential success of positive youth development programs. This paper systematically evaluates the effectiveness of such programs, exploring both their impact upon risk factors (e.g., sexual behaviour, substance use, antisocial behaviour, depression) and positive outcomes (e.g., academic achievement, prosocial behaviour, psychological adjustment) using meta-analyses.

Adolescent Health Risk Behaviors as a Public Health Problem

Adolescence is a critical period during which many health-risk behaviors are initiated, including substance use, sexual risk and antisocial behavior (Degenhardt et al. 2008; World Health Organisation 2014). Despite the recent decline in some risk behaviors (e.g., smoking and unprotected sex), young people are still more likely to engage in risky behaviors than adults over 25 (Eaton et al. 2006). Risky sexual behavior in young people under 25 results in unintended pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections (e.g., Department of Health 2011). In addition, between 6 and 13 % of adolescents smoke regularly, drink alcohol and use illicit drugs (e.g., Connell et al. 2009; Gunning et al. 2010; McVie and Bradshaw 2005). Aggression and antisocial behavior in young people are also problematic, with approximately a quarter of young people found to carry a weapon and 19 % found to have attacked someone with the intent of seriously hurting them (e.g., Beinart et al. 2002). Taken together, these findings highlight the frequency of initiation of health risk behaviors in adolescence.

In addition to their frequent occurrence in adolescence, behaviors such as substance use, risky sexual behavior, smoking and antisocial behavior tend to cluster (Hale and Viner 2012; Jackson et al. 2012a, b; Mistry et al. 2009; Wiefferink et al. 2006). Individuals engaging in one risky behavior are more likely to engage in others (DuRant et al. 1999). Such behaviors are thought to share common biological and environmental determinants (Beyers et al. 2004; O’Connell et al. 2009; Resnick et al. 1997), which likely shape the development of multiple risk-taking. For example, substance use before the age of 16 has been positively associated with early sexual initiation, poor contraceptive use, violence and delinquency (Bellis et al. 2008; Hawkins et al. 1999; Parkes et al. 2007). Adolescent risk-taking often continues into adulthood, with consequent negative outcomes such as poor physical, mental and sexual health; substance abuse and addiction; poor educational and occupational achievement; future morbidity and premature mortality (Biglan 2004; Fergusson et al. 2007; Flory et al. 2004; Mirza and Mirza 2008). Youth risk-taking behavior therefore has substantial personal and economic costs for adolescents, their families, communities and services (Scott et al. 2001; Hoffman and Maynard 2008; Parsonage 2009).

Positive Youth Development

Public health experts believe that reducing the prevalence of modifiable behavior patterns could result in reduced public costs, improved overall well-being and health throughout adolescence and adulthood (e.g., Steinberg 2004). Given the observed clustering of risk behaviors, it has been suggested that interventions should take a broad approach and address multiple problems and their common determinants simultaneously (e.g., Bonell et al. 2007; Hawkins et al. 1999; Kipping et al. 2012). Positive youth development interventions aim to address the common determinants of adolescent multiple health risk behaviors. As the term implies, positive youth development interventions do not focus solely upon a pathology or deficit model. While accepting that a holistic understanding of adolescent development must include adverse aspects, the positive youth development approach takes the perspective that all young people have inherent strengths (e.g., Damon 2004; Roth and Brooks-Gunn 2003a) and that development takes place within relational systems (e.g., Lerner 2006; Overton 2013). The aims of positive youth development interventions are to support adolescents to acquire a sense of competence, self-efficacy, belonging and empowerment (e.g., Bowers et al. 2010), thus promoting positive behavior and reducing the likelihood of risk behavior. Effective positive youth development interventions should optimize the interaction between the unique strengths of the individual and their contextual resources (e.g., healthy relationships with adults, access to community-based activities; Spencer and Spencer 2014). The potential advantages of positive youth development interventions have led to major investment in many countries. For example, in the UK, millions of pounds have been invested in youth development interventions (Scottish Government 2009) as public health officials see these as essential in promoting the health and well-being of young people (e.g., HM Government 2010). Therefore, it is important to understand the impact of these interventions and their mechanisms of action.

Although the philosophy and aims of positive youth development have been well articulated (e.g., Benson et al. 2006; Damon 2004; Larson 2000; Lerner 2006), the core components of an effective positive youth development program remain unclear (Brooks-Gunn and Roth 2014). There is considerable diversity in the operational features and activities that currently characterize positive youth development programs. In the first literature review, Catalano et al. (2002) defined positive youth development as developing cognitive, social, emotional, behavioral and moral bonding competences; self-efficacy; prosocial behavior; a belief in the future; a clear and positive identity; self-determination and spirituality. Roth and Brooks-Gunn (2003b) believed that for a program to be considered positive youth development it must (a) foster program goals, such as confidence, competence, character, connections and caring; (b) provide young people with opportunities and experiences at school, at home and in the community so that they can develop their interests and talents and build new skills and competencies; (c) create a supportive atmosphere in which young people can develop bonds with the adults involved in delivering the program as well as with the other program participants. Positive youth development interventions also need to be stable and long lasting, so that the participants have sufficient time to form and benefit and from positive relationships. The mechanisms by which positive youth development interventions are hypothesized to work are equally diverse. The active ingredients are thought to include (1) engaging young people in structured and productive activities thus diverting them from unhealthy behavior (Roth et al. 1998), (2) providing adolescents with additional resources and time to develop knowledge, skills and social networks (Pettit et al. 1997) and (3) addressing risk factors such as low self-esteem, poor educational attainment and low aspirations for the future by developing protective factors such as social and emotional competencies (Catalano et al. 2002). These examples demonstrate that positive youth development interventions vary considerably in structural and process features.

Prior Reviews of Interventions to Promote Positive Youth Development

Despite extensive investment, the effectiveness of positive youth development interventions in reducing risky behavior and promoting positive behavior is uncertain. Positive youth development programs have been examined in meta-analyses (e.g., Durlak et al. 2010; Shepherd et al. 2010) and narrative reviews (e.g., Catalano et al. 2002; Clarke et al. 2015; Gavin et al. 2010; Roth and Brooks 2003b). Some of these reviews have shown that positive youth development interventions are effective, with others yielding mixed or inconclusive findings. Investigations focusing on social outcomes have shown positive effects for academic achievement and cognitive variables and social skills (e.g., Catalano et al. 2004; Clarke et al. 2015; Durlak and Weissberg 2007; Durlak et al. 2010). However, Zief et al. (2006) in a review on after-school programs that combined recreation and/or youth development programming with academic support services, found that there was limited impact on academic and behavioral outcomes. Systematic reviews examining health outcomes have focused primarily on sexual health and have also had mixed findings (e.g., Catalano et al. 2004; Gavin et al. 2010; Shepherd et al. 2010). Some positive youth development reviews have also reported reductions in violence and drug use (e.g., Catalano et al. 2002; Durlak et al. 2010; Roth and Brooks 2003b). These findings demonstrate the lack of clarity and consistency in the existing literature on the impact of positive youth development programs.

The observed variance in findings across reviews of positive youth development interventions may be explained both the variety in program components and differences in review methodology. Existing reviews differ in their inclusion criteria, data pooling methods and the outcomes examined. Reviews have generally focused on either health or social/behavioral outcomes and some were non-systematic or were limited to a narrative approach (e.g., Catalano et al. 2002; Gavin et al. 2010; Roth and Brooks 2003b). Other reviews have limited inclusion to programs that have evidence of effectiveness (e.g., Catalano et al. 2002). All previous reviews have included a mix of randomized controlled trials, quasi-experiments and even non-experimental studies. This raises the possibility of systematic bias affecting the reviews, potentially conflating the effectiveness of positive youth development interventions or reducing their ability to detect genuine effects.

Contributions of this Review

The mixed findings of previous reviews, the range of positive youth development interventions and the widespread interest and investment in positive youth development has motivated this review. This review aims to address some limitations of previous reviews by adopting an inclusive approach. It differs from previous reviews in several ways. First, this review included all possible randomized controlled trials, which provide stronger evidence of a program’s impact, since randomized controlled trials have the highest possible internal validity. Second, a systematic strategy was used to identify all possible published and unpublished studies that provided evidence of program impact, regardless of their findings (positive, negative or no effects). We included both published and unpublished documents to avoid review bias, since studies with significant results are published whereas those with non-significant results remain unpublished (i.e., the “file-drawer effect”; Rosenthal 1979). Third, the impact of positive youth development interventions was explored across a range of health, social and behavioral outcomes. Fourth, this review systematically assessed study quality according to established guidelines (i.e., the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool). Finally, the evidence on particular outcomes across the studies was pooled using meta-analytic methods (where appropriate) to maximize power to detect intervention effects.

Purpose of the Current Study

The purpose of this review and meta-analysis was to synthesize evidence on the effectiveness of positive youth development interventions in young people aged 10–19 years. As many outcomes cluster because they shared the similar risk and protective factors, the effects of positive youth development interventions on multiple health, social and behavioral outcomes were explored. These included substance use, sexual risky behavior, psychological adjustment, prosocial behavior and academic performance. We also examined whether the variation in the effects was moderated by study, intervention and participant characteristics.

Method

The PRISMA guidelines for the conduct of systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Moher et al. 2009) were followed for the planning, conduct and reporting.

Study Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were formulated in accordance with the PICOS approach and included the following:

Population

The focus of our intervention was young people. The majority of participants (at least 75 %) at the pre-test were 10–19 years of age. As our interest was in preventive approaches, programs for specific populations such as youth with learning or physical disabilities were excluded. However, studies which targeted young people on the basis of their pre-existing risk behavior or other forms of targeting, such as young people at a high risk of teenage pregnancy, students from poor socioeconomic status families and students with poor grades, were included in this review.

Intervention

Positive youth development programs were defined as those that involved voluntary education to promote positive development (National Youth Agency 2007). Specifically, programs needed to address at least one of the 12 positive youth development goals formulated by Catalano et al. (2002) across social domains, including school, community and family, or more than one goal in a single domain. These goals included bonding, resilience, social, emotional, cognitive, behavioral or moral competence, self-determination, spirituality, self-efficacy, positive identity development, belief in the future, recognition for positive behavior, opportunities for pro-social behavior and prosocial norms.

Outcome

Any health or non-health outcome with at least two measurements points was included. Outcomes were measured in several categories; social and emotional skills, positive social behavior, mental health issues, sexual risk behavior and academic performance. Programs that resulted in both significant and non-significant changes in the outcomes compared to the control conditions were included, and programs that only focused on knowledge and attitude changes were excluded. Self-reports, official records, and third party (i.e., parents, teachers) measures (both validated or not validated) were eligible for inclusion. Table 1 details the outcomes used in this meta-analysis.

Setting

Out-of-school programs were the focus of the intervention. These included all activities targeting young people that were delivered regularly either in a community or a school-based setting outside normal school hours. Interventions that were delivered primarily during school hours were excluded, as these were the focus of a recent review (Durlak et al. 2011). For studies that included more than one intervention, only those interventions that focused on out-of-school programming as the main intervention were included. The following criteria were used to determine the main intervention: (a) if the author identified that out-of-school programming was the main intervention or (b) if the report gave out-of-school interventions a higher importance in relation to other interventions. Our review also excluded interventions that focused on family functions and so were targeted at parents/other family members as well as young people. Programs were only included if they focused primarily on young people and out-of-school programming to minimize the potential moderating effects of other variables (i.e. the effect of the program on parents, effects of in-school components) on intervention impact.

Design

Studies were eligible if they were randomized controlled trials and used a control condition to evaluate positive youth development interventions. Waiting list or no treatment, treatment as usual or alternative treatments were all considered valid control conditions. Other inclusion criteria were sufficient information to calculate effect sizes and publication in English between 1985 and 2015.

Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was performed to identify all published and unpublished studies that met the above inclusion criteria (see Fig. 1). Four main procedures were used to identify eligible studies: (a) An electronic search of 10 databases (Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts, Medline, PsycINFO, Embase, CINAHL Plus, ERIC, Social Services Abstracts, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials in the Cochrane Library, BibioMap and Trials Register of promoting health interventions); (b) a search of relevant registers and youth work-related websites (e.g. National Youth Agency, National Council for Voluntary Youth Services (NCVYS) Publications, 4-H); (c) reference list screening from previous reviews (e.g., Dickson et al. 2013; Harden et al. 2006; Morton and Montgomery 2011) and articles identified through electronic databases; (d) information from researchers on unpublished or ongoing articles or to clarify reports identified through other sources. The electronic searches were initially conducted between September and December 2014 and re-run prior to the analyses in July 2015.

Search terms were developed based on previous reviews and empirical studies (e.g., Dickson et al. 2013; Harden et al. 2006; Morton and Montgomery 2011) to reflect the agreed population criteria (young people), intervention criteria (positive youth development) and research methods. Specifically, keyword searches included variations in “children and young people”, “positive youth development”, “youth work”, “after-school” and (“intervention” OR “outcome” OR “program” OR “treatment”). Terms are available on request from the first author.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

Study selection was first performed in two main stages using a screening instrument. First, the titles and abstracts were scrutinized and excluded as appropriate. Relevant papers were then retrieved in full and assessed against the inclusion criteria. Documents that were potentially eligible were further reviewed to decide upon the final inclusion. Disagreements were resolved through discussion, and where necessary, studies were reviewed again. A data extraction form with five sections was used in the initial review to extract information from all articles that met the inclusion criteria. These were (a) general study characteristics (author, year of publication, country of origin), (b) population characteristics (number of participants, age, gender, grade level and risk level), (c) intervention characteristics (dosage, setting, format, components), (d) methodological characteristics (sample sizes, characteristics of the control group, design, attrition, follow-up period, intention to treat versus treatment on the treated analysis and outcome measures) and (e) statistical data needed for effect size calculations. For multiple publications from the same cohort, only studies with up-to-date or comprehensive data were included. Where data on study methods or results were missing, authors were contacted with a request to supply the information. In studies where the requested information was unavailable due to data loss or non-response, where possible the data was included in the meta-analysis.

Risk Bias Assessment

Two authors independently assessed each study’s methodological quality using the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool (Higgins et al. 2011). A third author assessed more than half the papers. All disagreements were discussed until a consensus was reached. Seven domains were scored with high, low or unclear risk of bias: Sequence generation, allocation concealment, participant blinding and personnel, outcome assessment blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other issues (i.e., baseline differences among groups). Each domain was scored as −1 for high risk, 0 for unclear risk and 1 for low risk. These scores were then summed to provide an overall quality score, which ranged from −6 to 6. Higher values signified a lower bias risk.

Statistical Analyses

Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Program (version 3) was used to carry out the meta-analyses. Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS 21.0) was used to analyze the descriptive data.

Effect Size Calculations

For continuous outcomes, we calculated the standardized mean differences, or the difference between two means divided by their pooled standard deviations. To avoid effect size underestimation (Field 2001) we applied Hedge’s g correction, which is usually recommended for a sample size lower than 20 (Borenstein et al. 2009). For dichotomous outcomes, we calculated an odds ratio and then transformed these (using meta-analysis software) to g statistics to allow for across study comparisons (Borenstein et al. 2009). When the studies failed to report means, standard deviations or proportions, effect sizes were calculated using a t test, F-statistic or p value and sample size (Borenstein et al. 2009). All effect sizes were coded in which positive values indicated favorable intervention effects such as lower pregnancy rates or less substance use, with values of 0.20 considered small, 0.50 as medium and 0.80 as large (Cohen 1988). When a study had multiple measures for the same outcome, an overall effect size was calculated by averaging the individual effect sizes. Therefore, a single mean effect size per study was calculated for each outcome category, which ensured statistical independence (Lipsey and Wilson 2001). For each outcome, a separate analysis was performed to examine the intervention effect at both post-intervention and follow-up. Post-intervention effect sizes were calculated for the assessment nearest in time to the completion of the program. When a study reported multiple follow-up assessments for a particular outcome, the longest follow-up period was selected to examine the robustness of the intervention.

For clustered randomized trials in which the study had adjusted for a clustering effect, the analysis results were imputed to calculate the effect sizes. Conversely, for studies that did not correct for potential clustering prior to effect size calculation, we corrected for design effect using the guidelines of Higgins and Green (2009). A random-effects model was used in our statistical analyses due to the heterogeneity between studies in target population, interventions employed and outcomes assessed (Hedges and Vevea 1998). All effect sizes were weighted prior to any analysis by multiplying the values with the inverse of their error variance (Lipsey and Wilson 2001). This method ensured that larger studies contributed more to the effect sizes and were given more weight in the analyses.

Statistical Heterogeneity

Statistical heterogeneity between the studies was assessed using the Q statistic and the I 2 statistic. A significant Q rejects the homogeneity null hypothesis and indicates whether the effect sizes varied more across the studies than that expected from the sampling error alone (Borenstein et al. 2009). I 2 (Higgins and Thompson 2002) shows the heterogeneity percentage across the studies (0 % = none, 25 % = low, 50 % = moderate, 75 % = high; Higgins and Thompson 2002).

Publication Bias

Finally, the presence of publication bias was assessed using funnel plots (Sterne and Egger 2001) and Begg and Egger tests (Begg and Mazumdar 1994). Funnel plots measure effect size against study size, and when there is no evidence of publication bias these plots display studies symmetrically around the pooled effect size. The Begg and Egger tests measure the extent of the funnel plots asymmetry (with p < 0.05 indicating the presence of statistically significant publication bias).

Results

Figure 1 summarizes the search and selection process. The literature search identified 15,452 citations from the electronic bibliographic database searches and a further 2789 citations through website searches and searching lists of previous reviews and studies. After the removal of duplicates, 669 abstracts were screened for relevance. In total, the full text of 352 studies were obtained and screened for eligibility. Of these, 328 did not meet the inclusion criteria and were excluded. Twenty-four studies were included in the final meta-analysis. Nine trials were reported in multiple companion publications (See Table 2 for details).

Characteristics of Included Studies and Programs

Design

Twenty programs were conducted in the USA and the remaining four were conducted in Croatia, Ireland, UK and New Zealand. Fourteen were published in peer-reviewed journals, eight were technical reports and two were dissertation projects. Publication dates ranged from 1992 to 2014, with most studies being published after 2000 (75 %). All 24 studies employed randomized controlled designs. Fifteen used students as the randomization unit; seven used schools, classes or communities and the remaining two used a combination. Seven studies compared the treatment group with usual care groups such as regular sex education (e.g., O’Donnell et al. 2002) or standard alcohol and drug education programs (e.g., Komro et al. 2008; Perry et al. 1996), seven used an alternative treatment and the remaining nine used no treatment or wait lists as comparisons. Twelve studies reported high attrition rates. The sample sizes ranged from 30 to approximately 5812. In most studies, data were gathered through self-reports. Five studies had data from school records, parents or teachers. A summary of studies included in the meta-analyses can be found in Table 2.

Participants

The total participant number randomized across the 24 studies was 23,258. The mean age at baseline ranged from 10 to 16. Young people included in the programs attended elementary schools (12 %), middle schools (37.5 %), high schools (25 %) or a mixture of grade levels (25 %). The predominant race studied was African American (58.3 %), followed by Caucasian (37.5 %) and Native American (4 %). Most studies included mixed-sex samples, with three studies focusing exclusively on females. Fifteen studies focused on at-risk students, six focused low-risk students and three included both. The identifiers for at-risk populations included students from low-income backgrounds (n = 12 studies), students of racial or ethnic minority background (n = 5 studies), and students with low academic achievements (n = 6 studies).

Interventions

Programs were conducted in a range of settings. Specifically, five studies were conducted in the community, four were conducted on school grounds and one program was conducted in a combined school/family domain. The majority (n = 15) were delivered in mixed settings, with five being delivered in a combined school, community and family settings. Fourteen interventions were conducted in one geographical locality, with the remaining ten conducted nationally. Interventions varied in duration and number of sessions. The mean intervention duration was 80 weeks, with studies ranging from 3 to 240 weeks. Seventeen interventions involved at least 20 sessions and 12 had two or three follow-ups. The length of the first follow-up ranged from immediately after the intervention to 5 years after the intervention. The first follow-up was conducted immediately or within 3 months of the intervention in five studies. Eleven studies had the first follow-up after 5–18 months, seven studies involved a second follow-up after 6–20 months and five studies reported a third follow-up from 12 to 32 months.

The most common outcome measures examined were behavioral including problem behaviors (66 %), academic improvement and school adjustment (45 %) and sexual risk behaviors/pregnancy (45 %). A smaller number of studies examined the effectiveness of these interventions on positive social behaviors (29 %) and psychological adjustment (33 %). Five interventions were delivered in a group, two were delivered individually, and the remaining seventeen combined individual and group interventions. Twenty-one programs were multi-modal and involved primary and secondary interventions. Three single-modal programs provided mentoring, skills training or academic components. Of the 21 multi-modal programs, primary after-school activities covered academic and homework help (n = 8), mentoring (n = 7), community service projects (n = 9), social or cognitive/emotional skill development (n = 16), recreational activities (n = 6) and job clubs (n = 2). The most common positive youth development goals reported by approximately half the programs were pro-social bonding, social competence, cognitive competence, emotional competence, self-efficacy, self-determination and a belief in the future.

Bias Risk

The bias risk in the studies is summarized in Fig. 2. Overall, the studies did not provide sufficient information to judge the randomization procedure quality, with 16 studies having an unclear rating. Only seven studies described the randomization sequence and only two indicated how the allocation concealment was conducted. As seen in Fig. 2, participants and personnel blinding rates were found to be at a high risk across all studies. Nevertheless, given the nature of the interventions, the blinding of participants or personnel was often not possible. Only three studies reported a blinding of the outcome assessors.

Attrition bias was high in 13 of the included studies, uncertain in two and low risk in nine. The findings in these studies may be biased and may not reflect the true effects of the intervention as the results may have been influenced by the characteristics of the participants who dropped out of the studies. Reporting bias was assessed as low risk in 18 studies, as these papers appeared to have provided results on the expected outcomes. Three studies were assessed as high risk, as they had incomplete information on the expected outcomes.

Intervention Effects

Table 3 shows the mean effect sizes, the 95 % confidence intervals and the corresponding statistics for each outcome category. Forest plots were created for each of the five outcome categories. Effect sizes ranged from 0.04 to 0.22, and despite all being positive (i.e., favoring the intervention condition), only three were significantly different from zero. Specifically, the analyses indicated significant effects in two areas; academic/school outcomes and psychological adjustment. The largest positive effect size was found in academic achievement (g = 0.22), with the lowest effect size found in positive social behaviors (g = 0.04). Intervention effects were based only on post-intervention data. Follow-up data were only combined for two outcome categories—psychological adjustment and academic achievement—when the category included at least two studies. For the remaining outcomes, the follow-up effects were reported for each study.

Heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was found in studies that reported the following outcomes; self-perception, academic achievement and sexual risk behaviors—which indicated the likelihood of moderating variables. However, there was no evidence of heterogeneity in studies that reported on problem behavior, academic adjustment or sexual health outcomes.

Behavioral Adjustments

Problem Behavior

Sixteen studies, which included 52 effect sizes, were averaged to show the intervention effects on problem behavior. To increase the statistical power and because moderator analyses showed no significant differences in intervention effects between conduct problems and substance use (t = 0.87; ns), we decided to pool all conduct problems and substance use measures into the same analysis. Eight studies investigated the impact of interventions on substance use, two measured conduct problems and six measured both conduct and substance use problems.

The results of the meta-analysis indicated no statistically significant differences between groups (g = 0.04; 95 % CI = −0.01, 0.10; ns; see Fig. 3). The statistical heterogeneity across the studies was neither important nor significant (Qtotal = 20.75; I 2 = 27.73 %; ns). Only one study (Dolan et al. 2011) measured the problem behavior after 21 months but showed no significant effects (g = 0.04; 95 % CI = −0.30, 0.39; ns).

Positive Social Behavior

This category was reported in seven studies and included outcomes such as getting along with others, social competence and prosocial behavior. Measures included teachers, parents and self-reports, the latter being the most frequently used. The results showed no significant statistical differences between groups at post-treatment (g = 0.04; 95 % CI = −0.11, 0.21; ns; see Fig. 4) and the effects’ heterogeneity was moderate but significant (Qtotal = 11.84; I2 = 49.34 %; p < 0.05). One study (Karcher et al. 2002) had an impact on heterogeneity and overall effect size, so after excluding this study, heterogeneity was lower (Qtotal = 7.86; I2 = 36.40 %; ns), but the effect size was smaller (g = 0.01; ns). Only one study (Dolan et al. 2011) measured positive social behaviors after 21 months and showed a positive significant effect (g = 0.27; 95 % CI = 0.00, 0.55; p < 0.05).

Psychological Adjustment/Internalizing Behavior

Eight studies, including 17 effect sizes, were averaged to show the intervention effects on psychological adjustment. The meta-analysis indicated a small but significant treatment effect (g = 0.17; 95 %CI = 0.04, 0.31; p < 0.05; see Fig. 5). The homogeneity analysis indicated a moderate degree of statistical heterogeneity (Qtotal = 27.16; I2 = 67.15 %; p < 0.01). The results suggested that exposure to positive youth development interventions improved psychological adjustment compared to the control condition, which was equivalent to a 0.17 standard deviation in magnitude. Three studies examined long-term intervention effects on self-perception and found that this did not change over time (g = 0.23; 95 % CI = 0.05, 0.42; p < 0.01). Feinberg et al. (2013) conducted a follow-up at 10 months post-intervention and reported no lasting significant effects on depression levels (g = −0.04; 95 % CI = −0.38, 0.30; ns).

Academic/School Outcomes

Academic/school outcomes were reported in 11 studies and included measures in relation to academic achievement and academic adjustment. Academic achievement outcomes were measured in 10 studies using school records, teacher, parent and self-report. Academic adjustment was reported in five studies based on self-report. A significant difference in academic achievement outcomes was found between the groups after the intervention (g = 0.22; 95 % CI = 0.07, 0.38; p < 0.05; see Fig. 6). Low but significant heterogeneity was found across the studies (Qtotal = 28.30; I2 = 68.20 %; p < 0.01). On average, the positive youth development interventions had a 0.22 standard deviation improvement in scholastic performance relative to the control groups. Generally, however, the analysis found no significant overall intervention effect on academic adjustment (g = 0.09; 95 % CI = −0.02, 0.20; ns) and the effect heterogeneity was low and non-significant (Qtotal = 4.15; I2 = 3.75 %; ns). Three studies measured academic/school outcomes that also indicated no lasting significant effects (g = 0.07; 95 % CI = −0.05, 0.20; ns).

Sexual Health Outcomes

As the moderator analyses showed no significant differences in the intervention effects between sexual risk behaviors and pregnancies (t = 0.32, ns), all measures were pooled. A meta-analysis of the 11 studies on sexual health outcomes showed no statistically significant differences between the positive youth development intervention and the control group (g = 0.05; 95 % CI = −0.00, 0.12; ns), with non-significant heterogeneity found across the studies (Qtotal = 8.41; I2 = 0 %; ns). All but two studies (Bonell et al. 2013; Trenholm et al. 2007) showed a positive effect size though none were statistically significant. Only one study measured effect over a longer follow-up (Bonell et al. 2013) and a small, non-significant effect was reported (g = 0.03; 95 % CI = −0.39, 0.45; ns) (Fig. 7).

Subgroup Analyses

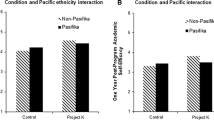

Homogeneity analyses were performed for each set of effect sizes (see Table 4). Significant heterogeneity was present in three of the outcome variables (positive social behaviors, psychological adjustment and academic achievement) so potential moderators of these effects were examined. Effects for problem behavior and sexual health outcomes were not heterogeneous, so moderators were not examined. Twenty-one analyses were performed with seven potential moderators across the three outcome variables. These moderators had three intervention characteristics (setting, duration and type), two sample characteristics (youth risk level and age) and one study characteristic (publication). Emotional distress and self-perceptions were pooled into psychological adjustments because the groups were too small for separate analyses.

Table 4 shows that the only moderation effect found was for the youth risk level moderator in relation to positive social behavior. Interventions delivered to low or mixed risk youth (k = 4; g = 0.23; p < 0.05) were more likely to produce a significant positive effect than interventions applied to high-risk young people. One study (Karcher et al. 2002) significantly contributed to this result (g = 0.79; p < 0.05). No other significant moderation effects were found. However, several trends emerged. Intervention characteristics that showed small significant trends were delivered in community-based settings (k = 3; g = 0.30; p < 0.05, psychological adjustment outcome), were in mixed settings (k = 6; g = 0.29; p < 0.05; academic achievement outcome), or lasted for more than 1 year (k = 4; g = 0.20; p < 0.05; psychological adjustment; and k = 4; g = 0.25; p < 0.05; academic achievement outcomes). Sample characteristics with significant trends included interventions designed for middle-school youth (k = 4; g = 0.16; p < 0.05, psychological adjustment outcome) and high-school youth ((k = 3; g = 0.36; p < 0.05; academic achievement outcome).

The 24 studies were grouped by one of the five primary intervention types; academic and skills training (n = 6), recreation (n = 2), community service projects (n = 2) and mixed (i.e. life skills/recreation, life skills/community or education/work experience) (n = 4). The effect sizes did not differ significantly between the groups, suggesting that the primary intervention type did not have a strong influence on the overall positive youth development intervention effect on any outcome. However, mentoring interventions showed a significant impact in relation to psychological adjustment outcome (k = 5; g = 0.21; p < 0.01).

Publication Bias

Publication bias was not detected, as the funnel plot shapes were symmetrical for all analyses (data not shown). The results of the Egger and Begg tests were non-significant for asymmetries on all outcomes (psychological adjustment: Egger p = 0.36, Begg p = 1.00; school outcomes: Egger p = 0.22, Begg p = 0.18; positive social behaviors: Egger p = 0.11, Begg p = 0.13; Problem behavior: Egger p = 0.12, Begg p = 0.26; sexual health outcomes: Egger p = 0.19, Begg p = 0.21).

Discussion

High-risk behaviors occur frequently in adolescence and tend to cluster together. They are associated with a range of adverse physical, psychological and occupational outcomes, which can persist into adulthood and carry significant personal, societal and economic costs. Adolescence is a developmentally sensitive period that presents a window of opportunity in which to potentially alter the course of high-risk behavior. Positive youth development interventions aim to prevent the escalation of risk behavior and enhance personal growth by drawing upon the strengths of young people and their contextual assets. Such programs have received significant investment in the past decade. The impact of these programs, as assessed by a number of previous reviews, is unclear. This lack of clarity may be accounted for variance in program components, methodological shortcomings in trial evaluations (e.g., measurement of relevant constructs) and differences in review methodology. Consequently, there is a lack of specificity in the outcomes that positive youth development interventions impact upon and their effective components. The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to examine the effectiveness of positive youth development interventions on a wide range of outcomes and to offer an updated review of the evidence base. To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to examine both published and unpublished randomized controlled trials and to report on the effects of such interventions on multiple outcomes. Twenty-four studies were included in the meta-analysis, nine of which have not been included in prior reviews.

Many of the included studies were affected by systematic bias and attrition rates were high. Positive youth development interventions did not lead to a significant reduction in antisocial/violent behavior, substance abuse or risky sexual behaviors or improve positive social behaviors in comparison to control interventions. However, significant effects for two outcome variables—psychological adjustment and academic achievement—were found. Positive youth development interventions were associated with modest but significant improvements in three areas; self-perception, emotional distress and academic achievement. In particular, significant improvements in self-perception were found to reduce emotional distress and improve academic achievement. These effects were small, with many individual studies failing to detect significant effects. This provides partial support for the notion that enhancing the assets of adolescents can support them to thrive academically and manage emotional difficulties. Given that poor academic achievement and low self-perception are associated with lower earnings, poor health (Bonell et al. 2005; Wellings et al. 2001; Emler 2001; Hallfors et al. 2006; Wheeler 2010) and delinquency (Maguin and Loeber 1996; Donnellan et al. 2005), improving youth academic achievement and self-perception could result in improved economic well-being and possibly positive health outcomes (Maynard 1996).

In addition to exploring which behaviors are modifiable through positive youth development intervention, it is important to gain an understanding for whom they work and how programs may be tailored to particular individual and contextual characteristics. This review addresses this question in a limited way through the examination of program and individual moderators. In this review, program characteristics were not associated with the strength of program outcomes, suggesting that positive youth development intervention effects were independent of setting. Program effects were similar regardless of age. However, young people deemed low-risk were more likely to benefit from positive youth development interventions than high-risk youth. It will be important for future research to examine both individual and contextual moderators of program effectiveness. Factors such as socioeconomic status, ethnicity, access to and engagement with ecological assets (e.g., community resources) are likely to be important. Such research would highlight the characteristics of individuals most likely to benefit from existing positive youth development interventions and which modifications will be required to extend the reach of programs to marginalized or high-risk groups. Cohort studies (e.g., the 4-H Study of Positive Youth Development; Lerner 2006) have already begun to measure these constructs and the relationships between them. Incorporation of such measures into randomized control methodology would provide a robust test of relational development systems theories upon which many positive youth development programs are based.

The findings of this review are consistent with prior quantitative (Durlak et al. 2010) and narrative reviews (Roth and Brooks 2003b; Catalano et al. 2004; Gavin et al. 2010) for some outcomes but not others. For example, the behavioral adjustment evidence contradicts the positive effects found in Durlak et al. (2010) in relation to problem behavior and positive social behaviors. However, they are consistent with Zief et al.’s (2006) and Durlak et al.’s (2010) findings regarding the non-significant effects on drug use. The academic adjustment results were in agreement with the findings from prior reviews, in that these interventions did not report any beneficial effects (Zief et al. 2006; Durlak et al. 2010). With regard to sexual health outcomes, the present results contradict the conclusions offered by prior reviews, which reported significant effects on sexual risk behavior and pregnancy rates (Shepherd et al. 2010; Gavin et al. 2010; Catalano et al. 2002). The conflicting findings between this review and previous reviews may be accounted for by a number of factors. These include differing inclusion criteria, study design and sample size. A conservative approach was adopted through selection of randomized controlled designs, utilization of an inclusive approach to study inclusion (e.g., published and unpublished data) to maximize the statistical power and a robust measure of quality assessment. The focus upon both positive and negative behavioral outcomes reflects an increasing consensus over the last two decades to the benefits for research, policy and practice of integrating promotion and prevention approaches to youth development (e.g., Brooks-Gunn and Roth 2014).

Whilst there has been considerable progress in research on positive youth development, this review highlights the limited extent to which conclusions can be drawn about positive youth development intervention effects on adolescent health and well-being. These limitations include the lack of high-quality studies and studies delivered outside the US. Nevertheless, this lack of high-quality evidence is not evidence of a lack of effectiveness. Future investment and research is therefore required to replicate USA-based programs on adolescent populations in different countries/communities, and the quality of the evaluation studies needs to be improved through more rigorous designs and minimization of potential biases. Evaluation of positive youth development programs needs to go beyond measuring the effects on behavior alone to encompass measures of individual positive youth development (e.g., the “5Cs”, hope, future expectations; Bowers et al. 2010) and contextual resources (e.g., parents and other adults, community activities and institutions). Measuring these constructs is complex and consensus is yet to be reached (Roth and Brooks-Gunn 2016; Tolan 2016). Future studies should also include adequate sample sizes and repeated follow-ups, on the basis that positive youth development is likely a dynamic process rather than an endpoint (Scales et al. 2016). There is a need for clearer descriptions of the program goals, components that contribute to program outcomes and their implementation features. When more programs have been rigorously evaluated and adequately reported, it may be possible to pool the evidence to determine program effectiveness. Further research is needed to understand the critical intervention components that contribute to the prevention of risk-taking behaviors and to robustly test novel interventions.

The findings of this review and the conclusions drawn about the positive youth development intervention effects need to be interpreted in the context of their limitations and the current state of evaluation research in this field. A paucity of rigorous research evidence exists on the impact of positive youth development interventions in adolescents; hence, this meta-analysis had only a few studies, some of which had small sample sizes and validity problems. Although we identified a sample of 24 studies, the number of studies included in any single analysis was much lower, particularly in the analyses that examined the impact of these interventions on certain outcomes. As a result, our power to detect significant differences was reduced. All the included studies suffered from some internal validity problems due to methodological flaws. Most studies had high performance bias, selection bias and detection bias risk, and therefore, may have overestimated the positive youth development intervention effect. However, evidence suggests that although adequate procedures to ensure random sequence allocation and allocation concealment are often followed, these are frequently underreported (Hill et al. 2002). In addition, participant blinding is often impossible in these types of interventions. There was a significant study heterogeneity associated with several outcomes, and moderator analyses were unable to explain this variability. Subgroup analyses only included a small number of studies, which led to a low statistical power, so the results may have failed to detect some important subgroup differences. The non-significant p value might have been due to low power and not necessarily related to effect size consistency (Borenstein et al. 2009). As with any systematic review, we cannot be sure that our search identified all possible studies, especially all unpublished studies, which have a tendency to report more null effects. Other limitations include an overreliance on studies conducted in the US, the use of self-report measures and the inclusion of urban, high-risk youth, predominantly African American samples. Therefore, these results cannot be generalized to all adolescents or to all programs outside the US. Given these limitations, it is not currently possible to give strong recommendations for the use of positive youth development programs. In summary, the findings of this review are encouraging but further research using robust methodology is required.

Conclusion

Positive youth development interventions are the focus of significant investment, especially in the US and UK. This review found that the effects of positive youth development on various outcomes were either non-significant or modest in magnitude. Additionally, the evidence base for their effectiveness was dominated by a high number of USA-based studies, many of which were poor quality. Nevertheless, the results of this review support the effectiveness of positive youth development interventions on academic achievement and psychological adjustment. Low-risk young people appear to benefit particularly from these programs. Substantial progress has been made in theoretical development of positive youth development. Improvements are now needed in the way studies are designed, evaluated and reported so that we can draw more concrete conclusions as to their real potential in reducing risk behavior and encouraging adolescents to thrive.

References

References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the meta-analysis.

*Allen, J. P., Philliber, S., Herrling, S., & Kuperminc, G. P. (1997). Preventing teen pregnancy and academic failure: Experimental evaluation of a developmentally based approach. Child Development, 68(4), 729–742. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb04233.x.

Begg, C. B., & Mazumdar, M. (1994). Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics, 50(4), 1088–1101.

Beinart, S., Anderson, B., Lee, S., & Utting, D. (2002). Youth at risk? A national survey of risk factors, protective factors and problem behaviour among young people in England, Scotland and Wales. London: Communities that Care.

Bellis, M. A., Hughes, K., Calafat, A., Juan, M., Ramon, A., Rodriguez, J. A., et al. (2008). Sexual uses of alcohol and drugs and the associated health risks: A cross sectional study of young people in nine European cities. BMC Public Health, 8, 155. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-8-155.

Benson, P. L., Scales, P. C., Hamilton, S. F., & Semsa, A, Jr. (2006). Positive youth development: Theory, research, and applications. In W. Damon, R. M. Lerner, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology, Vol. 1: Theoretical models of human development (6th ed., pp. 894–941). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Beyers, J. M., Toumbourou, J. W., Catalano, R. F., Arthur, M. W., & Hawkins, J. D. (2004). A cross-national comparison of risk and protective factors for adolescent substance use: The United States and Australia. Journal of Adolescent Health, 35(1), 3–16. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.08.015.

Biglan, A. (Ed.). (2004). Helping adolescents at risk: Prevention of multiple problem behaviors. New York: Guilford Press.

*Bird, J. M. (2014). Evaluating the effects of a strengths-based, professional development intervention on adolescents’ academic, social, and emotional outcomes. (Unpublished doctoral thesis), University, of South Caroline, United States. Retrieved from University of South Caroline website http://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/2790/?utm_source=scholarcommons.sc.edu%2Fetd%2F2790&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages.

Bonell, C., Allen, E., Strange, V., Copas, A., Oakley, A., Stephenson, J., et al. (2005). The effect of dislike of school on risk of teenage pregnancy: Testing of hypotheses using longitudinal data from a randomised trial of sex education. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 59(3), 223–230. doi:10.1136/jech.2004.023374.

Bonell, C., Fletcher, A., & McCambridge, J. (2007). Improving school ethos may reduce substance misuse and teenage pregnancy. BMJ, 334(7594), 614–616. doi:10.1136/bmj.39139.414005.AD.

*Bonell, C., Maisey, R., Speight, S., Purdon, S., Keogh, P., Wollny, I., et al. (2013). Randomized controlled trial of “teens and toddlers”: A teenage pregnancy prevention intervention combining youth development and voluntary service in a nursery. Journal of Adolescence, 36(5), 859–870. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.07.005.

Borenstein, M., Hedges, V., Higgins, J. P., & Rothstein, H. R. (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Bowers, E. P., Li, Y., Kiely, M. K., Brittian, A., Lerner, J. V., & Lerner, R. M. (2010). The five Cs model of positive youth development: A longitudinal analysis of confirmatory factor structure and measurement invariance. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(7), 720–735. doi:10.1007/s10964-010-9530-9.

Brooks-Gunn, J., & Roth, J. (2014). Promotion and prevention in youth development: Two sides of the same coin? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(6), 1004–1007. doi:10.1007/s10964-014-0122-y.

*Carter, S., Straits, K. J., & Hall, M. (2007). Project venture: Evaluation of an experiential, culturally based approach to substance abuse prevention with American Indian youth. The Journal of Experiential Education, 29(3), 397–400.

Catalano, R. F., Berglund, M. L., Ryan, J. A., Lonczak, H. S., & Hawkins, J. D. (2002). Positive youth development in the United States: Research findings on evaluations of positive youth development programs. Prevention and Treatment, 5(1), 15. doi:10.1037/1522-3736.5.1.515a.

Catalano, R. F., Berglund, M. L., Ryan, J. A., Lonczak, H. S., & Hawkins, J. D. (2004). Positive youth development in the United States: Research findings on evaluations of positive youth development programs. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 591(1), 98–124. doi:10.1177/0002716203260102.

Clarke, A. M., Hussein, Y., Morreale, S., Field, C. A., & Barry, M. M. (2015). What works in enhancing social and emotional skills development during childhood and adolescence? A review of the evidence on the effectiveness of school-based and out-of-school programmes in the UK. Retrieved from National University of Ireland Galway. https://aran.library.nuigalway.ie/handle/10379/4981.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences. Hillside. NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates.

Connell, C. M., Gilreath, T. D., & Hansen, N. B. (2009). A multiprocess latent class analysis of the co-occurrence of substance use and sexual risk behavior among adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 70(6), 943–951. doi:10.15288/jsad.2009.70.943.

Cross, A. B., Gottfredson, D. C., Wilson, D. M., Rorie, M., & Connell, N. (2009). The impact of after-school programs on the routine activities of middle-school students: Results from a randomized, controlled trial. Criminology & Public Policy, 8(2), 391–412. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9133.2009.00555.x.

Damon, W. (2004). What is positive youth development? The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 591(1), 13–24. doi:10.1177/0002716203260042.

*Deane, K. L. (2012). Project K in black & white: A theory-driven & randomised controlled trial evaluation of a youth development programme (Unpublished doctoral thesis) University of Auckland, New Zealand. Retrieved from University of Auckland website https://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/handle/2292/19753.

Degenhardt, L., Chiu, W. T., Sampson, N., Kessler, R. C., Anthony, J. C., Angermeyer, M., et al. (2008). Toward a global view of alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, and cocaine use: Findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS Med, 5(7), e141. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050141.

Department of Health (2011). Abortion statistics, England and Wales: 2010. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/abortion-statistics-england-and-wales-2010.

Dickson, K., Vigurs, C. A., & Newman, M. (2013). Youth work: A systematic map of the research literature. Dublin, Department of Children and Youth Affairs. Retrieved from http://www.drugs.ie/resourcesfiles/ResearchDocs/Ireland/2013/SystematicMapping.pdf.

*Dolan, P., Brady, B., O’Regan, C., Russell, D., Canavan, J., & Forkan, C. (2011). Big brothers big sisters of Ireland: Evaluation study: Report one: Randomised controlled trial and implementation report. Child and Family Research Centre, University of Galway, Foroige. Retrieved from http://www.foroige.ie/sites/default/files/big_brother_big_sister_report_3.pdf.

Donnellan, M. B., Trzesniewski, K. H., Robins, R. W., Moffitt, T. E., & Caspi, A. (2005). Low self-esteem is related to aggression, antisocial behavior, and delinquency. Psychological Science, 16(4), 328–335. doi:10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.01535.x.

Dryfoos, J. (1990). Adolescents at risk: Prevalence and prevention. New York: Oxford University Press.

DuRant, R. H., Smith, J. A., Kreiter, S. R., & Krowchuk, D. P. (1999). The relationship between early age of onset of initial substance use and engaging in multiple health risk behaviors among young adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 153(3), 286–291. doi:10.1001/archpedi.153.3.286.

Durlak, J. A., & Weissberg, R. P. (2007). The impact of after-school programs that promote personal and social skills. Chicago, Illinois: Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. Retrieved from http://www.uwex.edu/ces/4h/afterschool/partnerships/documents/ASP-Full.pdf.

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x.

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., & Pachan, M. (2010). A meta-analysis of after-school programs that seek to promote personal and social skills in children and adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 45(3–4), 294–309. doi:10.1007/s10464-010-9300-6.

Eaton, D., Kann, L., Kinchen, S., Ross, J., Hawkins, J., Harris, W.A., Lowry, R., McManus, T., Chyen, D., Shanklin, S., Lim, C., Grunbaum, J.A., & Weschler, H. (2006). Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States 2005. Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report 55(SS05), 1–108. Retrieved from Centers for Disease Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ss5505a1.htm.

Emler, N. (2001). Self esteem: The costs and causes of low self worth. York, York Publishing Services. Retrieved from https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/self-esteem-costs-and-causes-low-self-worth.

*Feinberg, M. E., Solmeyer, A. R., Hostetler, M. L., Sakuma, K. L., Jones, D., & McHale, S. M. (2013). Siblings are special: Initial test of a new approach for preventing youth behavior problems. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(2), 166–173. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.10.004.

Fergusson, D. M., Horwood, L. J., & Ridder, E. M. (2007). Conduct and attentional problems in childhood and adolescence and later substance use, abuse and dependence: Results of a 25-year longitudinal study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 88, S14–S26. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.011.

Field, A. P. (2001). Meta-analysis of correlation coefficients: A Monte Carlo comparison of fixed-and random-effects methods. Psychological Methods, 6(2), 161–180. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.6.2.161.

Flory, K., Lynam, D., Milich, R., Leukefeld, C., & Clayton, R. (2004). Early adolescent through young adult alcohol and marijuana use trajectories: Early predictors, young adult outcomes, and predictive utility. Development and Psychopathology, 16(01), 193–213. doi:10.1017/S0954579404044475.

Gavin, L. E., Catalano, R. F., David-Ferdon, C., Gloppen, K. M., & Markham, C. M. (2010). A review of positive youth development programs that promote adolescent sexual and reproductive health. Journal of Adolescent Health, 46(3), S75–S91. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.215.

*Gottfredson, D. C., Cross, A., Wilson, D., Rorie, M., & Connell, N. (2010). An experimental evaluation of the All Stars prevention curriculum in a community after school setting. Prevention Science, 11(2), 142–154. doi:10.1007/s11121-009-0156-7.

*Grossman, J. B., & Sipe, C. L. (1992). Summer Training and Education Program (STEP): Report on long-term impacts. Retrieved from http://ppv.issuelab.org/resource/report_on_long_term_impacts_step_program.

*Grossman, J. B., & Tierney, J. P. (1998). Does mentoring work? An impact study of the Big Brothers Big Sisters program. Evaluation Review, 22(3), 403–426. doi:10.1177/0193841X9802200304.

Gunning, N., Jotangia, D., Nicholson, S., Ogunbadejo, T., Reilly, N., Simmonds, N., et al. (2010). Smoking, drinking and drug use among young people in England in 2009. London: Information Centre for Health and Social Care.

*Hahn, A., Leavitt T., & Aaron P. (1994). Evaluation of the Quantum Opportunities Program (QOP). Did the program work? A report on the post secondary outcomes and cost-effectiveness of the QOP program (1989–1993). Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED385621.pdf.

Hale, D. R., & Viner, R. M. (2012). Policy responses to multiple risk behaviours in adolescents. Journal of Public Health, 34(suppl 1), i11–i19. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdr112.

Hallfors, D., Cho, H., Brodish, P. H., Flewelling, R., & Khatapoush, S. (2006). Identifying high school students “at risk” for substance use and other behavioral problems: Implications for prevention. Substance Use and Misuse, 41(1), 1–15. doi:10.1080/10826080500318509.

Harden, A., Brunton, G., Fletcher, A., Oakley, A., Burchett, H., & Backhans, M. (2006). Young people, pregnancy and social exclusion: A systematic synthesis of research evidence to identify effective, appropriate and promising approaches for prevention and support. London: Institute of Education.

Hawkins, J. D., Catalano, R. F., Kosterman, R., Abbott, R., & Hill, K. G. (1999). Preventing adolescent health-risk behaviors by strengthening protection during childhood. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 153(3), 226–234. doi:10.1001/archpedi.153.3.226.

Hedges, L. V., & Vevea, J. L. (1998). Fixed-and random-effects models in meta-analysis. Psychological methods, 3(4), 486–504. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.486.

Higgins, J. P., Altman, D. G., Gøtzsche, P. C., Jüni, P., Moher, D., Oxman, A. D., et al. (2011). The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ, 343, d5928. doi:10.1136/bmj.d5928.

Higgins, J. P., & Green, S. (Eds.). (2009). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (Vol. 5.0.2). Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Higgins, J., & Thompson, S. G. (2002). Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine, 21(11), 1539–1558. doi:10.1002/sim.1186.

Hill, C. L., LaValley, M. P., & Felson, D. T. (2002). Discrepancy between published report and actual conduct of randomized clinical trials. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 55(8), 783–786. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(02)00440-7.

HM Government (2010). Positive for youth: A new approach to cross-government policy for young people aged 13–19. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/175496/DFE-00133-2011.pdf.

Hoffman, S. D., & Maynard, R. A. (2008). Kids having kids: Economic costs and social consequences of teen pregnancy. Washington DC: The Urban Institute.

Jackson, C., Geddes, R., Haw, S., & Frank, J. (2012a). Interventions to prevent substance use and risky sexual behaviour in young people: A systematic review. Addiction, 107(4), 733–747. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03751.x.

Jackson, C., Sweeting, H., & Haw, S. (2012b). Clustering of substance use and sexual risk behaviour in adolescence: Analysis of two cohort studies. BMJ Open, 2(1), e000661. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000661.

*Karcher, M. J. (2005). The effects of developmental mentoring and high school mentors’ attendance on their younger mentees’ self-esteem, social skills, and connectedness. Psychology in the Schools, 42(1), 65–77. doi:10.1002/pits.20025.

*Karcher, M. J., Davis, C, I. I. I., & Powell, B. (2002). The effects of developmental mentoring on connectedness and academic achievement. School Community Journal, 12(2), 35–50.

Kipping, R. R., Campbell, R. M., MacArthur, G. J., Gunnell, D. J., & Hickman, M. (2012). Multiple risk behaviour in adolescence. Journal of Public Health, 34(suppl 1), i1–i2. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdr122.

*Komro, K. A., Perry, C. L., Veblen-Mortenson, S., Farbakhsh, K., Toomey, T. L., Stigler, M. H., et al. (2008). Outcomes from a randomized controlled trial of a multi-component alcohol use preventive intervention for urban youth: Project Northland Chicago. Addiction, 103(4), 606–618. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02110.x.

Komro, K. A., Perry, C. L., Williams, C. L., Stigler, M. H., Farbakhsh, K., & Veblen-Mortenson, S. (2001). How did Project Northland reduce alcohol use among young adolescents? Analysis of mediating variables. Health Education Research, 16(1), 59–70. doi:10.1093/her/16.1.59.

Larson, R. W. (2000). Towards a psychology of positive youth development. American Psychologist, 55, 170–183.

*LeCroy, C. W. (2004). Experimental evaluation of “Go Grrrl” preventive intervention for early adolescent girls. Journal of Primary Prevention, 25(4), 457–473. doi:10.1023/B:JOPP.0000048112.10700.89.

Lerner, R. M. (2006). Developmental science, developmental systems, and contemporary theories. In W. Damon, R. M. Lerner, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology, Vol. 1: Theoretical models of human development (6th ed., pp. 1–17). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Lipsey, m W, & Wilson, D. B. (2001). Practical meta-analysis (Vol. 49). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage publications.

*LoSciuto, L., Rajala, A. K., Townsend, T. N., & Taylor, A. S. (1996). An outcome evaluation of across ages: An intergenerational mentoring approach to drug prevention. Journal of Adolescent Research, 11(1), 116–129. doi:10.1177/0743554896111007.

Maguin, E., & Loeber, R. (1996). Academic performance and delinquency. Crime and Justice, 20, 145–264.

*Maxfield, M., Castner, L., Maralani, V., & Vencill, M. (2003). The Quantum Opportunity Program Demonstration: Implementation findings. Washington, DC: Mathematica Policy Research Inc.

Maynard, R. A. (1996). Kids having kids: A special report on the cost of adolescent childbearing. New York: Robin Wood Foundation.

McVie, S., & Bradshaw, P. (2005). Adolescent smoking, drinking and drug use. Centre for Law and Society: University of Edinburgh.

Mirza, K. A. H., & Mirza, S. (2008). Adolescent substance misuse. Psychiatry, 7(8), 357–362. doi:10.1016/j.mppsy.2008.05.011.

Mistry, R., McCarthy, W. J., Yancey, A. K., Lu, Y., & Patel, M. (2009). Resilience and patterns of health risk behaviors in California adolescents. Preventive Medicine, 48(3), 291–297. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.12.013.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264–269. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135.

*Monahan, D., Greene, V. L., Ditmar, M., & Roloson, T. (2011). Effectiveness of an abstinence-only intervention sited in a neighborhood community center. Journal of Children and Poverty,. doi:10.1080/10796126.2011.532481.

Morton, M., & Montgomery, P. (2011). Youth empowerment programs for improving self-efficacy and self-esteem of adolescents. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 7, 5.

National Youth Agency (2007). The NYA Guide to Youth Work in England. Leicester: National Youth Agency. Retrieved from http://www.nya.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/The_NYA_Guide_to_Youth_Work_and_Youth_Services.pdf.

O’Donnell, L., San Doval, A., Duran, R., Haber, D., Atnafou, R., Piessens, P., et al. (2003). Reach for health: A school sponsored community youth service intervention for middle school students. Los Altos, CA: Sociometrics.

*O’Donnell, L., Stueve, A., O’Donnell, C., Duran, R., San Doval, A., Wilson, R., et al. (2002). Long-term reductions in sexual initiation and sexual activity among urban middle schoolers in the Reach for Health service learning program. Journal of Adolescent Health, 31(1), 93–100. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00389-5.

O’Connell, M. E., Boat, T., & Warner, K. E. (Eds.). (2009). Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: Progress and possibilities. Washington: National Academies Press.

O’Donnell, L., Stueve, A., San Doval, A., Duran, R., Haber, D., Atnafou, R., et al. (1999). The effectiveness of the Reach for Health Community Youth Service learning program in reducing early and unprotected sex among urban middle school students. American Journal of Public Health, 89(2), 176–181. doi:10.2105/AJPH.89.2.176.

Overton, W. F. (2013). A new paradigm for developmental science: Relationism and relational-developmental systems. Applied Developmental Science, 17(2), 94–107.

Parkes, A., Wight, D., Henderson, M., & Hart, G. (2007). Explaining associations between adolescent substance use and condom use. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40(2), 180-e1. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.09.012.

Parsonage, M. (2009). Diversion: A better way for criminal justice and mental health. London: Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health.

Perry, C. L., Lee, S., Stigler, M. H., Farbakhsh, K., Komro, K. A., Gewirtz, A. H., et al. (2007). The impact of Project Northland on selected MMPI-A problem behavior scales. Journal of Primary Prevention, 28(5), 449–465.

Perry, C. L., Williams, C. L., Komro, K. A., Veblen-Mortenson, S., Forster, J. L., Bernstein-Lachter, R., et al. (2000). Project Northland high school interventions: Community action to reduce adolescent alcohol use. Health Education & Behavior, 27(1), 29–49. doi:10.1177/109019810002700105.

Perry, C. L., Williams, C. L., Komro, K. A., Veblen-Mortenson, S., Stigler, M. H., Munson, K. A., et al. (2002). Project Northland: Long-term outcomes of community action to reduce adolescent alcohol use. Health Education Research, 17(1), 117–132. doi:10.1093/her/17.1.117.

*Perry, C. L., Williams, C. L., Veblen-Mortenson, S., Toomey, T. L., Komro, K. A., Anstine, P. S., et al. (1996). Project Northland: Outcomes of a communitywide alcohol use prevention program during early adolescence. American Journal of Public Health, 86(7), 956–965. doi:10.2105/AJPH.86.7.956.

Pettit, G. S., Laird, R. D., Bates, J. E., & Dodge, K. A. (1997). Patterns of after-school care in middle childhood: Risk factors and developmental outcomes. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 1982, 515–538.

*Philliber, S., Kaye, J., & Herrling, S. (2001). The national evaluation of the Children’s Aid Society Carrera-Model Program to prevent teen pregnancy. Accord, NY: Philliber Research Associates.

Philliber, S., Kaye, J. W., Herrling, S., & West, E. (2002). Preventing pregnancy and improving health care access among teenagers: An evaluation of the Children’s Aid Society-Carrera Program. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 34(5), 244–251. doi:10.2307/3097823.

Qiao, C., & McNaught, H. (2007). Evaluation of project K. Retrieved from Ministry of Social Development website http://thehub.superu.govt.nz/sites/default/files/40181_project_k_0.pdf.

Resnick, M. D., Bearman, P. S., Blum, R. W., Bauman, K. E., Harris, K. M., Jones, J., et al. (1997). Protecting adolescents from harm: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA, 278(10), 823–832. doi:10.1001/jama.1997.03550100049038.

*Reyna, V. F., & Mills, B. A. (2014). Theoretically motivated interventions for reducing sexual risk taking in adolescence: A randomized controlled experiment applying fuzzy-trace theory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143(4), 1627–1648. doi:10.1037/a0036717.

Rhodes, J. E., Reddy, R., & Grossman, J. B. (2005). The protective influence of mentoring on adolescents’ substance use: Direct and indirect pathways. Applied Developmental Science, 9(1), 31–47. doi:10.1207/s1532480xads0901_4.

Rhodes, J. E., Reddy, R., Grossman, J. B., & Maxine Lee, J. (2002). Volunteer mentoring relationships with minority youth: An analysis of same-versus cross-race matches. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(10), 2114–2133. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb02066.x.

Rodríguez-Planas, N. (2010). Longer-term impacts of mentoring, educational services, and incentives to learn: Evidence from a randomized trial in the United States. Bonn, Institute for the Stud of Labor. Retrieved from ftp.iza.org/dp4754.pdf.

Rosenthal, R. (1979). The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychological Bulletin, 86(3), 638–641. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.86.3.638.

Roth, J. L., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2003a). What exactly is a youth development program? Answers from research and practice. Applied Developmental Science, 7, 94–111.

Roth, J. L., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2003b). Youth development programs: Risk, prevention and policy. Journal of Adolescent Health, 32(3), 170–182.

Roth, J. L., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2016). Evaluating youth development programs: Progress and promise. Applied Developmental Science, 20(3), 188–202. doi:10.1080/10888691.2015.1113879.

Roth, J., Brooks-Gunn, J., Murray, L., & Foster, W. (1998). Promoting healthy adolescents: Synthesis of youth development program evaluations. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 8(4), 423–459. doi:10.1207/s15327795jra0804_2.

Scales, P. C., Benson, P. L., Oesterle, S., Hill, K. G., Hawkins, J. D., & Pashak, T. J. (2016). The dimensions of successful young adult development: A conceptual and measurement framework. Applied Developmental Science, 20(3), 150–174.

Schirm, A., & Rodriguez-Planas, N. (2004). The Quantum Opportunity Program demonstration: Initial post-intervention impacts. Washington, DC: Mathematica Policy Research Inc.

Schirm, A., Rodriguez-Planas, N., Maxfield, M., & Tuttle, C. (2003). The Quantum Opportunity Program demonstration: Short-term impacts. Washington, DC: Mathematica Policy Research Inc.

Scott, S., Knapp, M., Henderson, J., & Maughan, B. (2001). Financial cost of social exclusion: Follow up study of antisocial children into adulthood. BMJ, 323(7306), 191. doi:10.1136/bmj.323.7306.191.

Scottish Government. (2009). Valuing Young people: Principles and connections to support young people achieve their potential. Edinburgh: Scottish Government.

Shepherd, J., Kavanagh, J., Picot, J., Cooper, K., Harden, A., Barnett-Page, E., et al. (2010). The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of behavioural interventions for the prevention of sexually transmitted infections in young people aged 13–19: A systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technology Assessment, 14(7), 1–230. doi:10.3310/hta14070.