Abstract

Mapping the relationship of peer influences and parental/family characteristics on delinquency can help expand the understanding of findings that show an interdependence between peer and family predictors. This study explored the longitudinal relationship between two characteristics of peer relationships (violence and perceived popularity) with subsequent individual delinquency and the moderating role of family characteristics (cohesion and parental monitoring) using data from the Chicago Youth Development Study. Participants were 364 inner-city residing adolescent boys (54 % African American; 40 % Hispanic). After controlling for the effects of age and ethnicity, peer violence is positively related to boys’ delinquency. The effect of popularity depends on parental monitoring, such that the relationship between popularity and delinquency is positive when parental monitoring is low, but there is no relationship when parental monitoring is high. Furthermore, parental monitoring contributes to the relationship between peer violence and delinquency such that there is a stronger relationship when parental monitoring is low. Additionally, there is a stronger relationship between peer violence and delinquency for boys from high cohesive families. Findings point to the value of attention to multiple aspects of peer and family relationships in explaining and intervening in the risk for delinquency. Furthermore, findings indicate the importance of family-focused interventions in preventing delinquency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Among the most studied and reliably implicated environmental risk factors for delinquency are peer and family relationships. There is ample evidence that delinquency level of friends and acquaintances correlates to youth criminal activity, and violence in particular (Elliott et al. 1985; Tremblay et al. 1995). Similarly, there is considerable evidence indicating that the qualities of peer relationships, such as acceptance and popularity, predict delinquency (Agnew 1991; Mayeux and Cillessen 2008). Engaging in aggressive acts can enhance status particularly among peers who also are delinquents (Hawley 2007; Henry et al. 2006). While there has been much interest in the relationship of these various aspects of peer relationships to delinquency, there has been limited consideration of their interrelation in explaining risk. Most studies have tested one dimension of peer relationships at a time, with the majority of the emphasis on peer deviance. This leaves uncertain whether other dimensions of peer relationships are important in understanding risk for delinquency. The present study focuses on the interrelation of two aspects of peer relationships, peer violence and popularity with peers. The study utilizes a sample of boys who reside in communities where delinquency is prevalent and peer relationships may be particularly important influences on development: the inner-city (Tolan et al. 2003).

Like peer influences, family relationships also have been documented to be direct influences on risk for delinquency (Tolan et al. 2003). Parenting practice constructs, such as monitoring and disciplinary practices and qualities of family relationships, such as cohesion and support, have been linked to the risk for delinquency in numerous studies (Patterson et al. 1998). More recently, studies have focused on how family influences might set the stage for peer influences on delinquency. At least two longitudinal tests have identified a confluence process best fitting to the combined impact (Dishion and Piehler 2007; Henry et al. 2001). The confluence is a combination of the direct and independent effects of family and peer relationships in affecting delinquency outcomes (Dishion et al. 1994b). In both cases, it was peer deviance that was emphasized as the peer influence. While important in informing about the type of interrelation of peer and family influences, these findings may be dependent on representation of peer influence as how deviant peers are or by only considering one dimension (e.g., peer deviance is the only peer-related variable included in the model). It may be that there is not a dependency on family characteristic for the influence of other peer relationship characteristics (e.g., popularity) implicated as delinquency predictors. Similarly, it may be that other peer relationship characteristics add to what is explained by peer deviance. The present article tests multiple aspects of each of these major areas of developmental influence to find out if more specific effects can be identified.

Peer Influences on Delinquency

In several longitudinal studies over the past 30 years, peer delinquency has been linked to subsequent individual delinquency of youth (Elliott et al. 1985; Prinstein and Dodge 2008). In fact, involvement with deviant peers often emerges as the strongest and most proximal risk factor for delinquency (Brook et al. 1986; Dishion et al. 1996; Hawkins et al. 1992). More recent studies have established that peer violent delinquency may be particularly influential. For example, Thornberry (1998) found that it was peers committing violent crimes that were a greater effect on individual violence and delinquency than peers committing strictly delinquent acts. Similarly, Henry and colleagues (Henry et al. 2001) found that peers’ violence, but not nonviolent delinquency, was related to subsequent violence and delinquency. These findings suggest that it would be useful to differentiate the extent to which peers engage in delinquency that is violent from those engaging in only other forms of delinquency in evaluating peer deviance influence.

Popularity with peers is another dimension of peer relationships having shown power in explaining delinquency. Initial conception and measurement suggested that less delinquent peers were more popular (Asher and McDonald 2009). However, with more careful developmental designs, a more complex relationship was found pertinent to adolescence. For example, aggressive behavior is linked to peer rejection in elementary school, but there is no relationship or even some positive relationship as adolescence begins (Miller-Johnson et al. 2003). However, results are not consistent (Mayeux and Cillessen 2008). Some studies have found that aggression increases among more popular youth, while no aggression is evidenced among less popular youth (Hawley 2007; Henry et al. 2006). Others have noted that delinquency and popularity may be linked positively when aggression serves to enhance social status in adolescence (Henry et al. 2006; Rose et al. 2004). For example, in unsafe communities where the use of aggression may be seen as required to maintain safety or helpful in accessing resources and status, popularity and delinquency could be related positively (Henry et al. 2006). These findings suggest that popularity may be an important contributor to explaining peer influences on delinquency risk. However, it is unclear to what extent the influence is in combination with peer violence or as a second direct effect. The present study considers these two dimensions and their potential collective influence on risk.

Family Influences on Adolescent Delinquency: Setting the Stage for Peer Influences

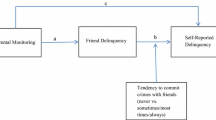

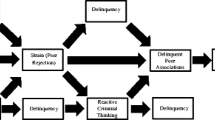

Review and multivariate studies have shown the value of examining peer influences during adolescence through a lens of the family as a continuing important influence, even as peer relationships emerge as a more proximal and more powerful explanatory correlate (Laursen and Collins 2009). The coercion model of development suggests that a coercive pattern of socialization begins within the family and may later generalize to relationships outside of the family (i.e., peer relationships), further supporting an antisocial pattern of socialization (Dishion et al. 1994b; Patterson 1982). The confluence model of peer influence builds upon this research and suggests that conventional peers reject children engaging in coercive socialization, limiting coercive children to socialize with other rejected children, also likely to be coercive and/or antisocial (Dishion et al. 1994a, b). Over time, deviant behavior escalates through peer reinforcement of antisocial values, attitudes, and behavior (e.g., deviancy training; Dishion et al. 1994b). Dishion et al. (1991, 1994a, b) applied the coercion process within families as a risk factor for increasing susceptibility to and engagement with delinquent peers and compared that to a model in which the coercion process had only a direct effect on risk for delinquency. They found that a confluence model that incorporated the “setting the stage” influence through peer influence as well as a continuing direct effect from family relationships and parenting as the best fit to their longitudinal data.

Similarly, Vitaro et al. (2000) differentiated youth by level of attachment to parents and level of parental monitoring. They examined the interaction of the parenting variables and best friend’s deviancy status (yes/no). Their findings indicate that for adolescents with low levels of attachment to parents during preadolescence, best friend’s deviancy was related positively to adolescents’ delinquent behavior at ages 13 and 14. While considering two aspects of the parent–adolescent relationship, Vitaro and colleagues considered a single dichotomously measured peer variable. This study suggests the importance of considering family and peer influences together. However, this study calls into question the importance of monitoring, which was the primary parenting practice influence in the Dishion et al. (1991, 1994b) study. Furthermore, it is unclear if the specific family findings would hold if more differentiation of peer deviance were considered (e.g., using a continuous measure of peer deviance rather than a dichotomous measure).

Focusing on a sample of 246 male adolescents from high-risk inner-city communities, Henry et al. (2001) applied the same type of comparison as Dishion et al. (1994a, b) and Vitaro et al. (2000) but added a distinction of peer deviance that is violent from that which is nonviolent in order to test whether findings might be specific to peer violence or generalized to peer deviance overall. This study reported that families characterized by emotional cohesion and parenting practices of consistent discipline and monitoring were associated with a lower likelihood of interaction with delinquent peers, whereas those with low cohesion and less use of effective parenting practices had more involvement with delinquent peers. Thus, this study seemed to support the importance of both family cohesion, which may overlap with felt attachments (Vitaro et al. 2000), and parenting practices including good monitoring (similar to Dishion et al. 1991, 1994a, b). In addition, Henry et al. (2001) reported that it was peer violence not peer delinquency in general that contributed to youth delinquency in their replication of Dishion et al.’s (1994a, b) confluence model. This difference may reflect the difference in residential location of the samples, as Henry et al. (2001) sampled a group of young boys residing in inner-city communities marked by high rates of violence. However, the findings are consistent with findings that peer violence can be a particularly salient influence on youth violence (Hawkins et al. 1992; Thornberry 1998). Otherwise Henry et al. (2001) reported results consistent with Dishion et al. (1991, 1994a, b), finding that a partially mediated model with both direct effects of family type on delinquency and violence and mediated effects through peer delinquency and violence best fit the data. Henry et al. also found that family characteristics moderated the relationship between peer violence and subsequent individual violence and delinquency but did not examine the relative importance of family characteristics and parenting practices on the peer influence process. This study brings that consideration into the analyses.

The Current Study

The current study builds from the above set of prior reports examining the confluence model by examining more than one aspect of both parenting and peer relationships in order to determine if more specific effects of developmental influence are identified. In addition, these analyses can help with the understanding of previous findings that seem to support mediation of family influence by peer relationship features as well as moderation of peer influences by family functioning (Henry et al. 2001). This evaluation of these two important influences can help clarify the interdependence of effects, offering valuable information in how peer and family relationships might be targeted in intervention efforts.

In this study we are interested in the following research questions: Are there significant direct predictive relationships between family cohesion, parental monitoring, peer violence and perceived popularity with peers measured in early adolescence and subsequent delinquency after controlling for age and ethnicity? Is there an interaction between perceived popularity and peer violence in predicting subsequent delinquency? What is the nature of any moderating role of family cohesion and parental monitoring on the relationship between peer violence and perceived popularity with peers and subsequent individual delinquency?

Method

Participants

Participants were 364 adolescent boys from the Chicago Youth Development Study (CYDS), a longitudinal study targeting high risk, adolescent males from inner city Chicago (see Henry et al. 2001 for a detailed review of data collection procedures). Data collection for CYDS began in 1991 and participants were assessed for five waves over a period of 7 years. Over 90 % of Wave 1 (W1) participants were retained for the consecutive waves of data collection. Participants’ ages ranged from 10 to 15 years in the first wave (W1) of data collections (M = 12.40; SD = 1.22) and between 13 and 19 years of age during the fourth wave (W4; M = 15.81; SD = 1.25). Participants were predominantly African American (54 %) and Hispanic (40 %). At W1, 62 % of the sample lived in single-parent households and the majority of participants were from low-income families; 47.6 % had a household income below $10,000 per year and 73.5 % had a household income below $20,000 per year.

An initial 1,105 fifth- and seventh-grade boys from 17 public schools in the Chicago area were screened for potential participation in the CYDS. This pool of potential subjects was screened and then selected so that 50 % of the sample had an elevated level of aggressive behavior (T > 63, 90th percentile) as indicated by the Teacher Report Form of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach 1991). This was approximately 33 % of the screened sample for recruitment with a similar number randomly selected from the remaining portion of the population. This yielded 364 participants who took part in some portion of the study. Each boy and his primary caretaker were interviewed, and most of the interviews took place at the participants’ home.

Measures

Delinquency

Individual delinquency was measured at W2, W3, and W4 (middle adolescence) using the Self-Report Delinquency measure (SRD; Elliott et al. 1985). This 30 item self-report scale (see “Appendix” for items) evaluated the frequency and severity of antisocial, delinquent, and violent behaviors committed over the past year. As suggested by Elliott et al. (1985), we created composite scores for the SRD measure, which ranged from 0 to 4 and were designed to differentiate responses by the relative seriousness and frequency of the committed violent and nonviolent offenses. Values of 0 represent non-offenders who reported little or no aggression, whereas values of 4 represent serious-chronic-violent offenders who reported high levels of antisocial behavior. Previous studies have established good reliability and validity of the SRD for our sample (for details see Henry et al. 2001). For our dependent measure, we averaged the Elliott scores across all available waves (W2, W3, and W4; r = .33–.53, all p’s < .001).

Family Cohesion

The Family Relationship Measure, a 35-item rating scale assessing 6 domains of family functioning (Gorman-Smith et al. 1996) was used to measure family cohesion at W1 (early adolescence) using parent-report. The scale was found to have good test–retest reliability and all scales have acceptable alpha levels. These scales have been used in numerous developmental risk studies over the past 15 years. The 6 domains assessed are: (a) Beliefs about the Family, (b) Emotional Cohesion, (c) Support, (d) Communication, (e) Shared Deviant Beliefs, and (f) Organization. LISREL analyses revealed that the 6 domains were represented well by two dimensions of family relationship characteristics: (a) Beliefs about Family and (b) Cohesion. The Cohesion construct incorporates the scales of Organization, Communication, Support, and Emotional Cohesion. This construct has been used extensively in prior research and has emerged as among the most consistently related to delinquency and aggression in this sample (see Gorman-Smith et al. 1996).

Parental Monitoring

The Parenting Practices scale was used to measure parental monitoring at W1 (early adolescence). The scale was developed from prior versions used in multiple studies including the Pittsburgh Youth Study (Thornberry et al. 1995). Reliable and valid scales were included to tap the following domains: (a) Positive Parenting, (b) Discipline Effectiveness, (c) Avoidance of Discipline, (d) Extent of Monitoring and Involvement in the Child’s life. Alphas for the scales range from .68 to .81. Confirmatory factor analyses using LISREL revealed two latent constructs: (a) Discipline and (b) Monitoring (see Gorman-Smith et al. 1996 for details on scale development and psychometric validation). The monitoring construct was found in prior analyses to best represent parental influence on risk in this sample and is used for these analyses.

Perceived Popularity with Peers

Two items on the Social Network Questionnaire (SNQ; Nair and Jason 1985) were used to measure perceived popularity with peers at W1 (early adolescence). The two items evaluated the popularity of participants in comparison to their friends and similar-aged youth in their neighborhood. Ratings of popularity were measured on a 5-point Likert scale with responses ranging from self being (least popular) to (most popular). A variable indicating average popularity with friends and similar-aged youth in the neighborhood was created (r of two items = .54, p < .001).

Peer Violence

A portion of the SNQ (Nair and Jason 1985) assessed the extent to which members of the participant’s peer group engaged in violent antisocial and delinquent behavior at W1 (early adolescence). This construct included 13 criminal offenses in which participants were asked to indicate (with “yes” or “no”) whether each member of their peer group had participated in any of these behaviors within the past year. Values for this construct were assigned based on the number of peers within the participant’s network who had committed violent offenses, according to the youth’s self-report. Scores were positively skewed and were log transformed prior to analysis.

Analytic Procedures

Forty-nine percent of boys (n = 177) had missing data on at least one of the variables included in this study. African American boys were less likely to have missing data than boys of other ethnicities (χ 2 = 21.31, p < .01). Missingness was not related to level of delinquency, family cohesion, parental monitoring, peer violence, or perceived popularity with peers. Missing data were handled using full information maximum likelihood (FIML) in Mplus 6.0.

A series of linear regression analysis in Mplus 6.0 were used to test our research questions. Two covariates were included in our models. Age (described in detail above) was entered as a continuous variable. Ethnicity was dummy coded such that African American boys (54 %) were compared to boys of all other ethnicities (40 % Hispanic, 6 % other). Family cohesion and parental monitoring were added in the next regression. Peer violence and popularity with peers and the interaction between the two were added in the next regression. The interaction terms between family variables and peer variables were added in the final regression model.

Results

Means, distribution characteristics and correlations among the predictors and outcomes are provided in Table 1. Results of the linear regression analyses are summarized in Table 2. After controlling for age and ethnicity, family cohesion and parental monitoring were not related significantly to delinquency. When the peer variables and their interaction were entered, peer violence, but not popularity, was positively related to delinquency. The interaction between popularity and peer violence was not significant. When we entered interactions for family functioning and the two peer variables, the interaction between family cohesion and peer violence significantly predicted delinquency (p < .05). Additionally, two interactions were significant at the trend level (p < .10): the interaction between peer violence and parental monitoring and the interaction between popularity and parental monitoring. As the sample size constrained the sensitivity to detect interaction at conventional significance levels, we considered this trend as indicating a notable relationship. The direct effect of peer violence remained even with the additions of the interaction terms.

To help with interpretation, we plotted each interaction effect. First, we split family cohesion at the mean and plotted the relationship between peer violence and delinquency for boys from high cohesive family and for boys from low cohesive families (Fig. 1). The relationship between peer violence and delinquency was stronger for boys from high cohesive families. Second, we split parental monitoring at the mean and plotted the relationship between peer violence and delinquency for boys from high monitoring families and for boys from low monitoring families (Fig. 2). The relationship between peer violence and delinquency was stronger for boys from low monitoring families. Third, we plotted the relationship between popularity with peers and delinquency for boys from high monitoring families and for boys from low monitoring families (Fig. 3). The relationship between popularity and delinquency was stronger for boys from low monitoring families.

Discussion

Research on the risk factors for delinquency indicates that both family and peer influences are important (e.g., Dishion et al. 1991, 1994a, b; Henry et al. 2001). However, few studies have examined the interdependence of family and peer risk factors, and those that do focus on single aspects of either family or peer risk. In this article, we extend prior examination of the interdependence of family and peer influences on delinquency (e.g., Dishion et al. 1994a, b; Henry et al. 2001) to examine multiple aspects of both family functioning and peer relationships. We find a complex set of relationships, including both direct and interactive effects. First, we find a negative relationship between peer violence and delinquency that is consistent with findings from other samples (Elliott et al. 1985; Tremblay et al. 1995). In addition, we find that popularity does not interact with peer violence, but has additional influence on delinquency risk, depending on level of parental monitoring. When parental monitoring is low popularity is linked to higher levels of delinquency. Parental monitoring is also important in the relationship between peer violence and delinquency; when parental monitoring is low peer violence is linked to higher levels of delinquency. This indirect effect of parental monitoring is consistent with those found with other populations (see Dishion and McMahon 1998 for summary of such findings). Surprisingly, there was a stronger relationship between peer violence and delinquency for boys from high cohesive families when compared to boys from low cohesive families. These findings unpack and extend Henry et al.s’ (2001) prior examination of the confluence model using data from the CYDS. Henry and colleagues used family typologies, and thus, could not test whether there are different aspects of family relationships that are important in the confluence model of parent and peer risk factors. Our results suggest that both family cohesion and parental monitoring are critical.

It was surprising that there was a stronger relationship between peer violence and delinquency for boys from high cohesive families, as we expected family cohesion to play a protective role as reported by Vitaro et al. (2000). Henry et al. (2001) report that within the CYDS sample, boys from families characterized by high cohesion are less likely to interact with delinquent peers. Our findings may indicate that, although less likely to interact with delinquent peers, high-risk boys from cohesive families may be particularly vulnerable to influence when they do interact with violent peers. During adolescence, peer relationships become increasingly important; however, family relationships also remain important (Laursen and Collins 2009). Within high-risk neighborhoods, some parents report the need to protect children from peer influences (e.g., Anderson 1989; Furstenberg 1993). One way of protecting children may be through family cohesiveness. Consequently, it may be that the protection intended by parents may leave these particular boys unprepared to resist influence in the presence of violent peers.

Our findings of the moderating role of parental monitoring are consistent with those of Dishion et al. (1994a, b). However, in that study, other aspects of family influence were not considered. Furthermore, only peer delinquency was considered. Our results bolster the specificity of the finding that parental monitoring sets the stage for peer influence and moderates the relationship between both peer violence and delinquency and popularity and delinquency. Our results are inconsistent with those of Vitaro et al. (2000), who found no moderation effects for parental monitoring on the relationship between peer deviance and delinquency. Vitaro et al. measured peer deviance using a dichotomous measure (yes/no), whereas we used a continuous measure of peer violence. Consequently, it may be that the greater specificity of measurement used in this study allowed for the detection of moderation findings. Additionally, the sample in the Vitaro et al. study consisted of all Caucasian Canadian non inner-city youth, whereas our sample was entirely U.S. inner-city African American and Hispanic. It is possible that parental monitoring is more important for inner-city high-risk youth. Further testing of how sample and setting characteristics might affect interactions is needed.

The finding of a positive relationship between popularity and delinquency when parental monitoring is low raises some intriguing considerations for understanding how peer relationships and delinquency are related in high-crime high poverty communities (Hawley 2007; Henry et al. 2006). Previous research has found that when measures of perceived popularity are used, popularity is associated positively with aggression over time. However, it is important to note that this sample is drawn from high-crime, high-poverty communities in which other roles may be limited and the use of violence may be more acceptable and functional then elsewhere (Attar et al. 1994). It may be that in these communities where some delinquency is more common than none (see Henry et al. 2001) there is peer esteem gained from delinquency involvement, particularly if parental monitoring is low and not providing needed care and attention for a more prosocial basis for esteem (Parkhurst and Hopmeyer 1998; Rose et al. 2004). It also may be that when parental monitoring is low, time with and engagement with peers, particularly those who are more deviant, may increase, with more delinquency valued among that group. Without monitoring within the family, children in large groups may be misguided and turn toward delinquent behavior (e.g., Dishion and McMahon 1998). It also may be that parents engaged with their children through monitoring are more likely to be sought for advice or have opportunities to help steer popular youth away from delinquency. If so, preventive and treatment interventions that emphasize increased parental monitoring and communication skills may be most important (Stattin and Kerr 2000). Improved communication and connection with parents may lessen the influence of and attachment to deviant peers.

The findings of this study should be interpreted in light of the following limitations. First, we were interested specifically in relationships for inner-city high-risk boys. It is unknown whether relationships are specific to this setting where crime rates are elevated above those found elsewhere in the United States. It also may be that these findings are specific to the sampling that was designed to over-represent high-risk youth within this high-risk setting. Second, although family functioning was measured using parent-reports, the peer variables and individual delinquency were both assessed by self-reports. It is possible that youth who are on an antisocial trajectory are more likely to report popularity with peers and more likely to report peers as violent. It is also important to note that self-reported popularity, as examined in this study, likely has different relationships with study variables than peer-rated popularity. A third limitation is that this study did not consider additional aspects of peer relationships that might have importance, such as attachment to peers or quality of friendships. Future research should include information from youth in both high- and low-risk settings and should include information from multiple reporters. Furthermore, additional aspects of peer relationships should be included in order to determine the specificity of findings related to peer violence and perceived popularity.

These findings may have useful implications for prevention. They seem to underline the value of parent/family focused intervention in enabling protective effects for youth, particularly when the focus of intervention is parental monitoring (Dishion and McMahon 1998). These results may suggest more direct focus in such interventions on peer relationships through the lens of parental monitoring and youth communication to parents (Stattin and Kerr 2000). This approach could help to shift from emphasizing parental monitoring to mitigate negative peer influence to encouraging more engagement to affect peer involvement or peer choice (Dishion and McMahon 1998).

Conclusion

Both family and peer influences, and their interdependence, are important in explaining high-risk urban boys’ delinquency (Dishion et al. 1994a, b; Henry et al. 2001; Vitaro et al. 2000). This study adds support for this claim and indicates the overall value of more complex assessments of peer and family relationships in understanding effects on delinquency. We considered two aspects of peer relationships—peer violence and perceived popularity—and found that, while not interdependent, each added to the explanation of delinquency in adolescence. We also found that both aspects of family relationships—family cohesion and parental monitoring—were important in the explanation of how peer influences relate to delinquency in adolescence, suggesting the importance of tracking ongoing family predictors when evaluating peer influences. Consequently, prevention and intervention efforts should focus on both parent and peer influences and how the two can be targeted in combination to prevent delinquency (Dishion and McMahon 1998).

References

Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Integrative guide for the 1991 CBCL/4-18, YSR, and TRF profiles. Burlington: Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont.

Agnew, R. (1991). Interactive effects of peer variables on delinquency. Criminology, 29(1), 47–72. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.1991.tb01058.x.

Anderson, E. (1989). Sex codes and family life among inner-city youths. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Studies, 501, 59–78. doi:10.1177/0002716289501001004.

Asher, S. R., & McDonald, K. L. (2009). The behavioral basis of acceptance, rejection, and perceived popularity. In K. H. Rubin, W. M. Bukowski, & B. Laursen (Eds.), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups. New York: Guilford Press.

Attar, B. K., Guerra, N. G., & Tolan, P. H. (1994). Neighborhood disadvantage, stressful life events, and adjustment in urban elementary-school children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 23(4), 391–400. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp2304_5.

Brook, J. S., Whiteman, M., Gordon, A. S., & Cohen, P. (1986). Dynamics of childhood and adolescent personality traits and adolescent drug use. Developmental Psychology, 22, 403–414. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.22.3.403.

Dishion, T. J., Duncan, T. E., Eddy, J., Fagot, B. I., et al. (1994a). The world of parents and peers: Coercive exchanges and children’s social adaptation. Social Development, 3(3), 255–268. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.1994.tb00044.x.

Dishion, T. J., McCord, J., & Poulin, F. (1999). When interventions harm: Peer groups and problem behavior. American Psychologist, 54, 755–764. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.54.9.755.

Dishion, T. J., & McMahon, R. J. (1998). Parental monitoring and the prevention of child and adolescent problem behavior: A conceptual and empirical formulation. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 1(1), 61–75. doi:10.1023/A:1021800432380.

Dishion, T. J., Patterson, G. R., & Griesler, P. C. (1994b). Peer adaptations in the development of antisocial behavior: A confluence model. In L. R. Huesmann (Ed.), Aggressive behavior: Current perspectives (pp. 61–95). New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Dishion, T. J., Patterson, G. R., Stoolmiller, M., & Skinner, M. L. (1991). Family, school, and behavioral antecedents to early adolescent involvement with antisocial peers. Developmental Psychology, 27, 172–180. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.27.1.172.

Dishion, T. J., & Piehler, T. F. (2007). Peer dynamics in the development and change of adolescent problem behavior. In A. Masten (Ed.), The Minnesota symposium on child psychology: Vol. 33. Multi-level dynamics in developmental psychopathology: Pathways to the future. Hillside, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates.

Dishion, T. J., Spracklen, K. M., Andrews, D. W., & Patterson, G. R. (1996). Deviancy training in male adolescents friendships. Behavior Therapy, 27(3), 373–390. doi:10.1016/S0005-7894(96)80023-2.

Elliott, D., Huizinga, D., & Ageton, S. (1985). Explaining delinquency and drug use. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Furstenberg, F. F., Jr. (1993). How families manage risk and opportunity in dangerous neighborhoods. In W. J. Wilson (Ed.), Sociology and the public agenda (pp. 231–258). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Gorman-Smith, D., Tolan, P. H., Zelli, A., & Huesmann, L. R. (1996). The relation of family functioning to violence among inner-city minority youths. Journal of Family Psychology, 10, 115–129. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.10.2.115.

Hawkins, J. D., Catalano, R. F., & Miller, J. Y. (1992). Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 64–105. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64.

Hawley, P. H. (2007). Social dominance in childhood and adolescence: Why social competence and aggression may go hand in hand. In P. H. Hawley, T. D. Little, & P. C. Rodkin (Eds.), Aggression and adaptation: The bright side to bad behavior (pp. 1–30). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Henry, D. B., Miller-Johnson, S., Simon, T. R., Schoeny, M. E., & The Multi-site Violent Prevention. (2006). Validity of teacher ratings in selecting influential and aggressive adolescents for a targeted preventive intervention. Prevention Science, 7(1), 31–41. doi:10.1007/s11121-005-0004-3.

Henry, D. B., Tolan, P. H., & Gorman-Smith, D. (2001). Longitudinal family and peer group effects on violence and nonviolent delinquency. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 30(1), 172–186.

Laursen, B., & Collins, W. A. (2009). Parent-child relationships during adolescence. Handbook of adolescent psychology, Vol. 2: Contextual influences on adolescent development (3rd ed., pp. 3–42). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Mayeux, L., & Cillessen, A. H. (2008). It’s not just being popular, it’s knowing it too: The role of self-perceptions of status in the associations between peer status and aggression. Social Development, 17(4), 871–888. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00474.x.

Miller-Johnson, S., Costanzo, P. R., Coie, J. D., Rose, M. R., Browne, D. C., & Johnson, C. (2003). Peer social structure and risk-taking behaviors among African American early adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 32(5), 375–384. doi:10.1023/A:1024926132419.

Nair, D., & Jason, L. A. (1985). An investigation and analysis of social networks among children. Special Services in the Schools, 1, 43–52. doi:10.1300/J008v01n04_04.

Parkhurst, J. T., & Hopmeyer, A. (1998). Sociometric popularity and peer-perceived popularity: Two distinct dimensions of peer status. Journal of Early Adolescence, 18, 125–144. doi:10.1177/0272431698018002001.

Patterson, G. R. (1982). Coercive family process. Eugene, OR: Castalia.

Patterson, G. R., Reid, J. B., & Dishion, T. J. (1998). Antisocial boys. In J. Jenkins, K. Oatley & N. Stein (Eds.), Human emotions: A reader (pp. 330–336). Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

Prinstein, M. J., & Dodge, K. A. (2008). Current issues in peer influence research. In Understanding peer influence in children and adolescents (pp. 3–13) New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Rose, A. J., Swenson, L. P., & Waller, E. M. (2004). Overt and relational aggression and perceived popularity: Developmental differences in concurrent and prospective relations. Developmental Psychology, 40, 378–387. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.40.3.378.

Stattin, H., & Kerr, M. (2000). Parental monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child Development, 71(4), 1072–1085. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00210.

Thornberry, T. P. (1998). Membership in youth gangs and involve- ment in serious and violent offending. In R. Loeber & D. Farrington (Eds.), Serious and violent juvenile offenders: Risk factors and successful interventions. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Thornberry, T. P., Huizinga, D., & Loeber, R. (1995). The prevention of serious delinquency and violence: Implications from the program of research on the causes and correlates of delinquency. In J. C. Howell, B. Krisberg, J. D. Hawkins, & J. J. Wilson (Eds.), Sourcebook on serious, violent, and chronic juvenile offenders (pp. 213–237). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Tolan, P. H., Gorman-Smith, D., & Henry, D. B. (2003). The developmental ecology of urban males’ youth violence. Developmental Psychology, 39(2), 274–291. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.39.2.274.

Tremblay, R. E., Masse, L. C., Vitaro, F., & Dobkin, P. L. (1995). The impact of friends’ deviant behavior on early onset of delinquency: Longitudinal data from 6 to 13 years of age. Development and Psychopathology, 7, 649–667. doi:10.1017/S0954579400006763.

Vitaro, F., Brendgen, M., & Tremblay, R. E. (2000). Influence of deviant friends on delinquency: Searching for moderator variables. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology: An Official Publication of the International Society for Research in Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 28(4), 313–325. doi:10.1023/A:1005188108461.

Acknowledgments

AKH conceived of the study, performed statistical analyses, and drafted the manuscript. MID, NT, and AA participated in the design and interpretation of the analyses; PHT conceived of the study, participated in the interpretation of the analyses and helped to draft and edit the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Items on the Self-Report Delinquency Scale

Appendix: Items on the Self-Report Delinquency Scale

During the last year, have you ever:

-

1.

…lied about your age to get into someplace or to buy something, for example, lying about your age to get into a bar or to buy alcohol?

-

2.

…carried a hidden weapon?

-

3.

…been loud, rowdy, or unruly in a public place so that people complained about it or you got in trouble?

-

4.

…made obscene telephone calls, such as calling someone and saying dirty things?

-

5.

…been drunk in a public place?

-

6.

…purposely damaged or destroyed property that did not belong to you (for example, breaking, cutting or marking up something)?

-

7.

…purposely set fire to a house, building, car or other property or tried to do so?

-

8.

…broken city curfew laws (that is, been in a public place including out in the street without a parent or adult after curfew)?

-

9.

…avoided paying for things such as movies, bus or subway rides, food, or computer services?

-

10.

…gone into or tried to go into a building to steal something?

-

11.

…stolen or tried to steal money or things worth $5 or less?

-

12.

…stolen or tried to steal money or things worth between $5 and $100?

-

13.

…stolen or tried to steal money or something worth $100 or more?

-

14.

…taken something from a store without paying for it (including events you have already told me about)?

-

15.

…snatched someone’s purse or wallet or picked someone’s pocket?

-

16.

…knowingly bought, sold, or held stolen goods or tried to do any of these things?

-

17.

…stolen or tried to steal a motor vehicle such as a car or motorcyle?

-

18.

…used checks illegally or used a slug or fake money to pay for something?

-

19.

…attacked someone with a weapon or with the idea of seriously hurting or killing them?

-

20.

…hit someone with the idea of hurting them (other than the events you just mentioned)?

-

21.

…used a weapon, force, or strongarm methods to get money or things from people?

-

22.

…thrown objects such as rocks or bottles at people (other than events you have already mentioned)?

-

23.

…forged or copied someone else’s signature on a check or legal document without their permission?

-

24.

…embezzled money, that is used money or funds entrusted to your care for some purpose other than that intended?

-

25.

…made fraudulent insurance claims, that is falsified or inflated medical bills and property or automobile repair or replacement costs?

-

26.

…intentionally underreported money earned or received, overestimated expenses or losses, or otherwise cheated on your state or federal income taxes?

-

27.

…stolen money, goods, or property from the place where you work?

-

28.

…been paid for having sexual relations with someone?

-

29.

…physically hurt or threatened to hurt someone to get them to have sex with you?

-

30.

…had or tried to have sexual relations with someone against their will (other than those events you just mentioned)?

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Henneberger, A.K., Durkee, M.I., Truong, N. et al. The Longitudinal Relationship Between Peer Violence and Popularity and Delinquency in Adolescent Boys: Examining Effects by Family Functioning. J Youth Adolescence 42, 1651–1660 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9859-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9859-3