Abstract

Effects of ethnicity and neighborhood quality often are confounded in research on adolescent delinquent behavior. This study examined the pathways to delinquency among 2,277 African American and 5,973 European American youth residing in high-risk and low-risk neighborhoods. Using data from a national study of youth, a meditational model was tested in which parenting practices (parental control and maternal support) were hypothesized to influence adolescents’ participation in delinquent behavior through their affiliation with deviant peers. The relationships of family and neighborhood risk to parenting practices and deviant peer affiliation were also examined. Results of multi-group structural equation models provided support for the core meditational model in both ethnic groups, as well as evidence of a direct effect of maternal support on delinquency. When a similar model was tested within each ethnic group to compare youths residing in high-risk and low-risk neighborhoods, few neighborhood differences were found. The results indicate that, for both African American and European American youth, low parental control influences delinquency indirectly through its effect on deviant peer affiliation, whereas maternal support has both direct and indirect effects. However, the contextual factors influencing parenting practices and deviant peer affiliation appear to vary somewhat across ethnic groups. Overall the present study highlights the need to look at the joint influence of neighborhood context and ethnicity on adolescent problem behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the United States, juveniles account for a substantial proportion of crimes even though juvenile arrest rates have been declining for the past 10 years. In 2008, juveniles accounted for 15 % of all violent crime arrests (e.g., murder, robbery, assault) and 24 % of all property crime arrests (e.g., larceny, vandalism, and motor-vehicle theft) (OJJDP 2009). Self-report data indicate that actual levels of adolescent delinquent behavior are even higher than the official arrest data. Furthermore, delinquency is an issue in all ethnic groups, although rates of some offenses differ (Piquero and Brame 2008), and prior research indicates that the processes contributing to delinquent behavior may vary between ethnic groups, perhaps owing to differences in neighborhood contexts. Two major influences on adolescent delinquency are parenting behaviors and deviant peer affiliation. Parenting behaviors such as support and behavioral control have been linked repeatedly to adolescents’ involvement in delinquency and other problem behaviors (Hoeve et al. 2009), and affiliation with deviant peers has proven to be one of the strongest predictors of delinquent behavior (Haynie and Osgood 2005). In turn, these peer and family influences may be shaped by cultural and neighborhood forces (Cantillion 2006; Sampson and Groves 1989). In this paper, we take an ecological perspective (e.g., Brofenbrenner 1994) on adolescent delinquency by examining simultaneous effects of parenting, peers and neighborhood contexts. Furthermore, we examine the role of ethnicity as a cultural context (e.g., Hill 2006) that may shape processes and pathways leading to delinquency.

Prior research shows that neighborhood characteristics affect rates of delinquency (Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn 2000) and provides mixed evidence of ethnic differences in delinquency rates (Piquero and Brame 2008). Yet, for the most part, the effects of ethnicity and neighborhood context on delinquency have been examined separately. Studies of neighborhood effects often have focused on poor, high risk and high crime areas without considering cultural differences in parenting (e.g., Chung and Steinberg 2006; Rankin and Quane 2002). Other studies have documented differing effects of parenting practices on delinquency for European and African American adolescents without assessing neighborhood context (e.g., Lansford et al. 2004). Because minority families are disproportionately likely to live in poor or high crime areas (Sampson and Wilson 1995), ethnicity and neighborhood quality are confounded. Thus, ethnic differences could reflect cultural differences in meanings of parenting practices, differences in ecological setting, or both. However, few studies have attempted to examine the joint effects of ethnicity and neighborhood context on the pathways leading to delinquency. To address this gap, the current study examines the relationships of parenting behaviors and deviant peers to delinquency for African American and European American adolescents residing in high-risk and low-risk neighborhoods.

Parenting Practices, Ethnicity, and Delinquent Behavior

Research consistently has demonstrated the role of parenting in negative adolescent outcomes, including delinquent behavior (Patterson et al. 1990). Theories of delinquency (Hirschi 1969; Hagan 1989) have identified parent–child relationship quality and parental control as important processes. Hirschi (see also Gottfredson and Hirschi 1990) argued that children’s attachment to parents deters antisocial behavior, because children who are close to their parents imagine their parents’ reactions to misconduct when temptation arises. Parents also exert direct control through supervising their children, monitoring their behavior, and punishing misconduct. In line with these notions, supportive parenting, characterized by parental warmth, acceptance, and involvement, has been linked to lower levels of adolescent problem behavior in numerous studies (e.g., Gorman-Smith et al. 2000). Moreover, closeness to parents and higher psychological support from parents negatively predict delinquent behavior independent of parental control (de Kemp et al. 2006; Demuth and Brown 2004; Wright and Cullen 2001). Research also has indicated that parental control can influence adolescent problem behavior. Generally, studies find that higher levels of parental control are associated with lower levels of delinquent behavior (Dornbusch et al. 1985; Gray and Steinberg 1999; see Hoeve et al. 2009 for meta analysis).

Ethnicity may influence both parenting practices and the association between particular practices and adolescent behavior, as different cultural values are emphasized within African American and European American families (Hill 2006). Hill posits that African Americans have culturally specific parenting styles owing to their shared cultural values and unique experiences as an ethnic minority group in the United States (see also, Garcia-Coll et al. 1996; Ogbu 1981). Studies indicate that African American parents are more restrictive and authoritarian, on average, than European American parents (Dornbusch et al. 1987; Furstenberg et al. 1999). Moreover, there is evidence of ethnic differences in parenting practice effects, though findings are inconsistent (see Amato and Fowler 2002). Whereas authoritarian practices have been linked to poorer academic, behavioral, and psychological adjustment among European American youth, these effects are weaker or even reversed among African American youth (Dornbusch et al. 1987). Duniform and Kowaleski-Jones (2002) reported that maternal warmth and control (parental rules regarding TV, homework, and knowing children’s whereabouts) were associated negatively with delinquency for African Americans but not European Americans. Lamborn et al. (1996) found that unilateral decision making by parents, while associated with poorer psychological development among European American adolescents, predicted better behavioral adjustment (less misconduct) among African American adolescents. Finally, physical discipline, which is associated with externalizing behavior among European American children, does not consistently predict behavior problems among African American children (Deater-Deckard et al. 1996) and is associated with lower levels of antisocial behavior for African American youth (Lansford et al. 2004). Thus, strict control and other authoritarian parenting practices, while linked to negative outcomes among European American children, appear less detrimental (and even beneficial) for African Americans. Contrary to the differential effects of behavioral control, parental support seems to operate in a similar manner for both European American and African American youth. Warm, highly supportive parenting has been linked to lower delinquency in both ethnic groups (e.g., Walker-Barnes and Mason 2001).

Deviant Peers and Delinquency

Association with deviant peers is one of the most consistent predictors of delinquent behavior (e.g., Haynie and Osgood 2005). If peers are antisocial, they may foster deviant behavior through direct peer pressure or deviancy training, in which peers establish social norms that encourage antisocial behavior towards each other (Patterson et al. 2000). Furthermore, deviant peer affiliation may help explain the effects of parenting on delinquency. Several studies have found that parental control (e.g., punitiveness) appears to affect adolescents’ delinquent behavior indirectly through deviant peer association (Brody et al. 2001; Chung and Steinberg 2006; Dodge et al. 2008; Galambos et al. 2003). Research indicates that the relationship between delinquency and parental support also operates in part through deviant peer association (Scaramella et al. 2002). Essentially, warm, supportive parenting with emphasis on moderate levels of behavioral control helps facilitate strong parent–child bonds that, in turn, curb both selection and influence of antisocial peers (Brown and Bakken 2011; Parker and Benson 2004).

Neighborhood Context and Delinquency

Adolescents in low-income or high crime neighborhoods are more likely to engage in delinquent behavior (Kowaleski-Jones and Dunifon 2006; Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn 2000). This effect appears to be indirect and to operate through parenting behaviors, as neighborhood and community characteristics influence the quality of parenting (Simons et al. 2005). Neighborhoods that provide little collective support or stability (for example, poor, urban areas) can lead parents to express less supportiveness and be more punitive (Cantillion 2006; Ceballo and McLoyd 2002; Gutman et al. 2005). Furthermore, the stressors associated with residing in poor neighborhoods may lead to less effective parenting (e.g., poor monitoring strategies, low nurturance), which in turn can facilitate delinquent behavior (e.g., Byrnes et al. 2011; Rankin and Quane 2002). Some scholars suggest that authoritarian practices, including harsh parenting and restrictive control, may be adaptive strategies for parents in poor or unsafe neighborhoods (Kotchick and Forehand 2002). Strict obedience to parental authority may be protective for youth in neighborhoods where the opportunity for antisocial behavior is high (Parke and Buriel 2006). If so, strict parenting should be associated with lower levels of delinquent behavior in such contexts. Consistent with this notion, Beyers et al. (2003) documented that stricter supervision and monitoring of adolescents was particularly effective for curbing adolescent delinquency in risky neighborhoods. Stricter parenting in poorer quality neighborhoods may reduce delinquent behavior in part by reducing deviant peer contacts. Adolescents in low income, socially disorganized, high crime neighborhoods have more opportunity to associate with deviant peers (Brody et al. 2001; Zimmerman and Messner 2011). Gottfredson et al. (1991) found that adolescents who lived in neighborhoods characterized by high social disorganization and disadvantage reported more deviant peer contact than those who lived in more affluent and cohesive neighborhoods. Because adolescents are more likely to associate with deviant peers in disadvantaged neighborhood, strict parenting may be especially useful in these contexts, helping restrict adolescents’ access to deviant peers. Finally, because norms supporting antisocial behavior may facilitate delinquent behavior in disadvantaged neighborhoods (Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn 2000), deviant peer effects on delinquency may be stronger in such neighborhoods.

Because a higher proportion of minority families reside in high risk neighborhoods (e.g., Sampson and Wilson 1995), it is plausible that cross-ethnic differences in parenting practices and their effects could reflect differences in neighborhood conditions. Despite such possibilities, only a few studies have tested the differential effects of parenting practices across neighborhoods that vary in risk levels, and even fewer have addressed possible confounds with ethnicity (e.g., Lamborn et al. 1996). To add to the complexity, the pathways from neighborhood context to delinquency may depend on ethnicity. For example, Elliott et al. (1996) found that neighborhood disadvantage (poverty, mobility, proportion of single parents, and ethnic diversity) had a direct effect on problem behavior in a sample of ethnically heterogeneous Denver youth. However, for a sample of African American Chicago youth, the relationship between neighborhood disadvantage and problem behavior was indirect—fully mediated by informal control (i.e., institutional and social control, mutual respect, and neighborhood bonds; Elliott et al. 1996). In short, it remains unclear whether strict control in African American families stems from (a) cultural approaches to parenting specific to African Americans, (b) parenting practices that are reactive to risky neighborhood settings, or (c) an interaction whereby culturally-specific parenting practices are manifested in high-risk settings. To further clarify neighborhood and ethnicity effects on the relationship between parenting and delinquency, it is important to examine neighborhood differences within ethnic groups.

The Present Study

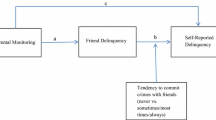

In this study, we draw on the separate literatures on neighborhood context and ethnic differences in parenting processes to test a process model of delinquent behavior in which parenting practices influence delinquency indirectly through deviant peer association. Based on an ecological perspective (Brofenbrenner 1994) and family stress models (e.g., Conger et al. 1992), we situate these processes within a broader ecological framework that includes family background characteristics as predictors of parenting and deviant peer affiliation (see Fig. 1). As shown in Fig. 1, ecological conditions, such as low family income, single-parent households, and features of the surrounding neighborhood, are hypothesized to predict parenting (support and control) by imposing pressures or stressors that undermine parenting. In turn, reduced parental support and control are expected to predict higher levels of delinquent behavior. Poverty and family economic hardship are linked to delinquency (Eamon 2001; Sampson and Laub 1994). Moreover, these factors are stressful and undermine effective parenting, resulting in negative outcomes for adolescents (Brody et al. 2001; Conger et al. 2002). Neighborhood problems are also sources of stress (Gutman et al. 2005) that can impair parenting. Finally, single parents report more parenting stress (Anderson 2008), their children engage in more delinquent behavior (Griffin et al. 2000), and the effect of single parent families on delinquency appears to be mediated by lower levels of parental support, involvement, and control (Demuth and Brown 2004; Wright and Cullen 2001). In contrast to earlier family stress models, we examine whether the effect of parenting on delinquency operates in part by increasing the risk of deviant peer affiliation. Extending the family stress model, we further investigate whether ecological factors predict not only parenting practices but affiliation with deviant peers, and whether these relationships differ by ethnicity and neighborhood context.

Our primary goal is to determine whether our ecological model of adolescent delinquency operates similarly for African Americans and European Americans and across different neighborhood contexts. Within this broader goal, we examine whether parenting practices influence delinquency indirectly through deviant peer affiliation; and we also examine whether the pathways from parenting to deviant peers and from deviant peers to delinquency differ across ethnic groups and neighborhood contexts. Each of these issues is addressed by testing the hypothesized ecological model within and across ethnic groups and neighborhood contexts.

Based on the previous literature on the effects of parenting practices and deviant peers on delinquency, our first hypothesis was that higher levels of parental support and parental control would be associated with lower levels of delinquency via an indirect path through deviant peers. Furthermore, given findings supporting ethnic differences in the effects of parenting practices, we examined ethnic differences in the relationship between parenting practices and delinquency, hypothesizing that parental control would have a stronger effect on delinquent behavior for African American youth. We also examined the potential effects of neighborhood context on both parenting and deviant peer association. We hypothesized that poor quality neighborhood conditions would be associated with higher levels of parental control. We then examined how the relationships between parenting, peers and delinquency differ between neighborhood contexts, hypothesizing that the relationship between deviant peer association and parenting practices would be stronger for youth in high-risk neighborhoods compared to those in low-risk neighborhoods. We examined whether these relationships would be similar for both ethnic groups. Finally, we explored the extent to which ecological factors predicted parenting across different ethnic groups and neighborhood contexts.

Methods

Sample

Data for the present analysis came from Waves 1 and 2 of the in-home sample of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health). No other waves were used in order to focus specifically on adolescence. The Add Health dataset is based on a sample of 80 high schools (and their feeder middle schools) selected with unequal probability, and stratified by enrollment, region, urbanicity, type of school, and racial/ethnic mix to be representative of U.S. schools (Blum et al. 2000). A representative sample of youth in these schools was selected and supplemented with several special subsamples to increase the number of adolescents from particular ethnic groups. Students in grades 7–11 at Wave 1 in the home survey were followed up approximately 1 year later (Wave 2). The present study restricted the sample to students who responded to both waves and who were assigned Wave 2 survey weights (n = 12,765), which was 76 % of the student sample in grades 7–11 at Wave 1. To avoid non-independence of cases, we randomly selected one sibling in each family for inclusion, thereby excluding 1,803 youth. Students who participated in Wave 2 differed significantly from those who dropped out on several variables: those who remained had lower levels neighborhood problems (as reported by parents), more maternal support, and less association with deviant peers (as reported by adolescents). We further restricted the analysis to non-Hispanic youth who self-identified as either African American or European American youth in order to eliminate potential confounds regarding ethnicity. The final analytic sample included 8,250 youth (52 % female). The average age at Wave I was 14.90 years (SD = 1.52), and the ethnic breakdown was European American (n = 5,973; 72 %) and African American (n = 2,277; 28 %).

Measures

Adolescent and parent reports of all key indicators came from the Wave 1 him home survey, with the exception of the dependent variable (delinquency), which was measured at Wave 2. Wave 2 delinquency was chosen to allow temporal separation in mediation models. All variables were adolescent-report except for public assistance and neighborhood problems, which were reported by primary caregivers, typically mothers (87 % for European Americans, 86 % for African Americans).

Ethnicity, Family Structure, Gender, and Age

To determine race, adolescents were asked: “What is your race? You may give more than one answer.” Youth reporting more than one racial group were asked: “Which one category best describes your racial background?” Youth who selected either African American (coded as 2) or European American (coded as 1) as their only or primary race were retained. Respondents were also asked: “Are you of Hispanic or Latino origin?” Adolescents who responded “yes” to this item were excluded from analysis. To measure family structure, families with two biological or adoptive parents (1) were contrasted with all other family structures (0). Gender (boys = 1; girls = 2) and age in years were used as predictors of delinquent behavior and parenting practices.

Financial Hardship

Parents responded to three questions about their family’s economic circumstances: “Last month, did you or any member of your household receive: Aid to Families with Dependent Children? Food stamps? A housing subsidy or public housing?” Each item was coded as 0 (no) or 1 (yes), and the three items were summed to yield a total score ranging from 0 to 3.

Neighborhood Context

There were two measures of neighborhood context: neighborhood problems and social cohesion. Parents were asked five questions about neighborhood problems. Two items assessed perceived neighborhood problems: “In this neighborhood, how big a problem are drug dealers and drug users?” and “In this neighborhood, how big a problem is litter or trash on the streets and sidewalks?” These items were coded as 0 (no problem at all), 1 (a small problem) or 2 (a big problem). Two dichotomous items assessed a lack of neighborhood problems: “You live here because there is less crime in this neighborhood than there is in other neighborhoods” and “You live here because there is less drug use and other illegal activity by adolescents in this neighborhood,” coded as 1 (no) and 0 (yes). A final item was “How much would you like to move away from this neighborhood?” coded as 0 (not at all) or 1 (some) or 2 (very much). Scores on all items were recoded to reflect the presence/absence of problems and then summed to form a neighborhood problems index ranging from 0 to 5, with higher scores indicating more neighborhood problems as perceived by parents (α = .63 for European Americans,; α = .72 for African Americans). (See Byrnes et al. 2011; Ingoldsby et al. 2006 for similar approaches.) We also created a dichotomous neighborhood risk variable (0 = low risk; 1 = high risk): Parents reporting three or more neighborhood problems were coded as living in a high-risk neighborhood. This cut-off was used in order to ensure adequate sample sizes for all within-race groups (see Table 1 for sample sizes).

Adolescents were asked four questions about neighborhood social cohesion, including social interactions between neighbors, a key aspect of neighborhood cohesion (Sampson et al. 2002). Three items were coded as 1 (true) or 0 (false): “You know most of the people in your neighborhood”; “In the past month you have stopped on the street to talk with someone who lives in your neighborhood”; “People in this neighborhood look out for each other.” A fourth item: “Do you usually feel safe in your neighborhood” was coded as 0 (no) and 1 (yes). The four items were summed to measure neighborhood cohesion, with possible scores ranging from 0 to 4 (α = .53 for European Americans, α = .47 for African Americans). Parents’ reports of neighborhood problems and adolescents’ reports of neighborhood cohesion were not highly correlated (see Table 1), and were included as separate indicators of neighborhood quality.

Maternal Support

Adolescents responded to five items regarding their relationship with their mother. Responses ranged from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much) (“How close do you feel to your mother? How much do you think she cares for you?”) for two questions and from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree) for three questions (Most of the time, your mom is warm and loving towards you; You are satisfied with the way your mom and you communicate with each other; Overall, you are satisfied with your relationship with your mom). Scores were averaged, resulting in a perceived maternal support scale (α = .84 for European Americans, α = .83 for African Americans) with higher average scores indicating more supportive parenting. This scale has been used in numerous studies with Add Health data (e.g., Wolff and Crockett 2011; Trejos-Castillo and Vazsonyi 2009).

Parental Control

Adolescents were asked whether or not they were allowed to make seven every day decisions on their own (“Do your parents let you make your own decisions about: the time you must be home on weekend nights; the people you hang around with; what you wear; how much television you watch; what television programs you watch; what time you go to bed on week nights; what you eat?”). Answers were scored either no (0) or yes (1). Scores were averaged (with final variable range from 0 to 1), and higher scores indicated greater parental control (α = .59 for European Americans, α = .62 for African Americans). Versions of this scale have been used in diverse studies with Add Health data (e.g., Bynum and Kotchick 2006; Wolff and Crockett 2011).

Deviant Peer Affiliation

Adolescents reported how many of their three best friends smoked cigarettes daily, drank alcohol, and used marijuana in the last month. Scores on each item could range from 0 to 3. The three items were averaged such that higher scores indicated more deviant friends (α = .77 for European Americans; α = .74 for African Americans). Other studies have used similar measures to estimate deviant peer association (Brody et al. 2001; Weaver and Prelow 2005).

Delinquency

The data set included 15 items in which adolescents reported how often in the past 12 months they had engaged in specific delinquent behaviors (e.g., “In the past 12 months, how often did you deliberately damage property that didn’t belong to you?”). Responses ranged from 0 (never) to 3 (5 or more times). Four items, regarding gang affiliation, robbery, using a weapon, and larceny of items worth more than $50, were not included in the delinquency latent variable, as the scores for these variables were highly skewed, and removing them significantly improved the overall model fit of the latent variable measurement model. The final measure contained 11 items (α = .83). The delinquency measure is similar to other adolescent report measures of risky behaviors (e.g., the Monitoring the Future Study; Johnston et al. 2010 and the Youth Risk Behavior Survey, Center for Disease Control and Prevention 2010).

Data Analytic Plan

The primary analyses entailed testing a series of structural equation models (SEMs) based on the ecological model in Fig. 1. First, we examined the model separately for African Americans and European Americans in order to test the proposed indirect paths from parenting to delinquency in each group. Second, we conducted two-group SEMs to compare the model structure for African Americans and European Americans (MacCallum and Austin 2000). A two-group model with no equality constraints on the structural paths was estimated and compared to a second model in which all structural paths were constrained to be equal for African Americans and European Americans; a χ2 difference test was used to test for significant ethnic differences in structure. Follow-up SEMs were then conducted to identify which paths differed significantly. Third, two-group models for high-risk and low-risk neighborhoods were estimated for each ethnic group to examine neighborhood effects. Significant neighborhood differences were tested using a χ2 difference test comparing constrained and unconstrained models, and follow-up SEMs were conducted to identify the source of any differences. For all models, the outcome variable (delinquency) was modeled as a latent variable; all other variables were modeled as observed variables.

The SEMs were conducted using Mplus 5.1 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2010) to account for clustering and weighting of the Add Health data (Chantala and Tabor 1999). Full information maximum likelihood was used to reduce bias associated with missing data. In FIML, substantive model parameter estimates are computed from incomplete data under the assumption that data are missing at random. This approach is considered to produce less bias than listwise deletion (Hoefer and Hoffman 2007). To assess model fit, we used χ2 tests based on the MLR estimator, which produces maximum likelihood estimates of standard errors and χ2 tests that are robust to non-normality and non-independence of the data (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2010). In addition to the χ2 test, which is sensitive to sample size (Kline 1998), we used the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA), and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) to assess model fit. Good fit was indicated by a CFI greater than .95, RMSEA less than .06 and SRMR less than .08 (Hu and Bentler 1999). For adequate fit, a CFI greater than .89 but less than .95, and values for RMSEA and SRMR below .1 may be acceptable (Barrett 2006). χ2 difference tests were calculated as recommended by Muthén and Muthén (1998–2010). All indirect effects were calculated using Mplus, which uses the product of coefficients method for testing mediation analyses (MacKinnon et al. 2002).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Univariate statistics and mean differences between groups for all variables are displayed in Table 1, while bivariate statistics for all variables are displayed in Table 2. The average of the 11 delinquency items was used to analyze univariate and bivariate statistics. Table 1 shows that European Americans reported more two-parent families, higher levels of autonomy granting (lower control), more deviant friends, and more delinquency than African Americans, whereas African Americans reported more economic hardship (receipt of public assistance) and neighborhood problems. Comparisons between high-risk and low-risk neighborhoods indicated that in both ethnic groups economic hardship, neighborhood problems, deviant peer affiliation, and delinquency were higher in high-risk neighborhoods. In addition, for European Americans only, adolescents in high-risk neighborhoods reported lower levels of maternal support. Table 2 shows that the core associations among parenting, deviant peers, and delinquency were supported in both ethnic groups at the bivariate level: parental support and control were inversely associated with having deviant friends, which in turn was positively associated with delinquency.

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted on the delinquency items to determine the appropriate factor structure for the latent variable. The one-factor model had acceptable model fit for European Americans and African Americans, χ2(41) = 294.525, CFI = .96, RMSEA = .03, SRMR = .03; χ2(41) = 105.15, CFI = .94, RMSEA = .03, SRMR = .04, respectively. We tested for measurement equivalence of the delinquency measure across ethnic groups and neighborhood risk (Byrne et al. 1989). There was partial metric invariance for the ethnic group comparison, χ2(91) = 319.27, CFI = .96, RMSEA = .03, SRMR = .04, with the “gang fight” item being the only item that had to be freed across ethnic groups. For both ethnic groups, the indicators of delinquency all loaded significantly onto the latent variable There was full metric invariance between high and low risk neighborhoods for European American adolescents, χ2(92) = 243.06, CFI = .95, RMSEA = .03, SRMR = .04 and scalar invariance for African Americans, χ2(102) = 183.72, CFI = .92, RMSEA = .03, SRMR = .06.

Indirect Pathways from Parenting to Delinquency

To determine whether the hypothesized ecological model fit the data in each ethnic group, we conducted single group SEMs. The models showed acceptable model fit for African Americans and European Americans, respectively, after adding specific correlated error terms that were suggested by model modification indices and were appropriate based on theory (see Table 3). Next, we tested the baseline (unconstrained) two-group model to examine the hypothesized indirect paths from parenting to delinquency via deviant peers in both ethnic groups., This model also showed acceptable model fit (Table 3). Figure 2 shows the standardized path coefficients for the key variables in the model for European Americans (outside parentheses) and African Americans (inside parentheses). For simplicity, the paths from gender and age are not depicted; these coefficients are available upon request.

Main model statistics for unconstrained paths comparing European American and African American youth. Note: All estimates are standardized, African American estimates are in parentheses. Solid lines indicate paths that are significantly different between groups. For simplicity, paths for age and gender are not displayed. Results for these paths are available upon request. * < .05, ** < .01

As seen in Fig. 2, for adolescents in both ethnic groups, the relationships among parenting, deviant peers, and delinquency were similar in nature: that is, lower levels of maternal support and higher levels of parental control were associated with higher affiliation with deviant peers, which in turn was associated with higher levels of delinquent behavior. In addition, higher maternal support predicted lower levels of delinquency directly. The two mediation analyses were significant. For both groups, there was an indirect effect of parental control on delinquency, whereby higher levels of parental control predicted lower levels of delinquency through deviant friends (European American Sobel Z = 4.13; African American Sobel Z = 5.25). For maternal support, the indirect effect through deviant peers was significant for both groups (European American Sobel Z = 2.42; African American Sobel Z = 2.36). In addition, in both ethnic groups there was a direct effect of maternal support on delinquency, suggesting partial mediation. Other paths were also significant (see Fig. 2). In both groups, age was positively associated with parental control and negatively associated with maternal support and boys reported higher levels of maternal support than girls (not shown).

Cross-Ethnic Comparisons

When the structural paths were constrained to be equal across the two ethnic groups, the model fit, although still acceptable, was significantly worse than the unconstrained model, ∆χ²(21) = 83.65, p < .01, indicating that the structural model differed for African Americans and European Americans. To determine which paths differed significantly across ethnic groups we systematically freed individual paths in the constrained model and tested for significant improvements in model fit. Paths that differed significantly remained freed; all other paths were constrained to be equal in the final model. The final model fit indices are displayed in Table 3.

χ2 difference tests (shown in Table 4) revealed ethnic differences in the paths linking parenting, deviant peers, and delinquency. The path between maternal support and deviant peer affiliation differed across groups such that maternal support was more protective against deviant peers for European American youth. The positive relationships between deviant peer affiliation and delinquent behavior also differed across groups, being stronger for European American than African American youth. To examine the hypothesis that parental control had a stronger effect on delinquency for African American youth, we constrained the paths among parental control deviant peers and delinquent behavior to be equal across ethnic groups and used a Wald test of parameter constraints to test for a significant ethnic difference in the indirect paths. Results indicated that the indirect path was significantly stronger for African American than for European American youth (Wald Test = 4.34, p < .05).Footnote 1

The paths from ecological variables to parenting and deviant peers also differed by ethnicity. For European Americans, more neighborhood problems were associated with higher parental control. In contrast, the negative relationship between adolescent’s perception of neighborhood cohesion and parental control was stronger for African Americans. Finally, the role of other ecological variables differed by ethnicity. Specifically, public assistance was associated with higher parental control for European American but not African American adolescents. Residing with two biological/adoptive parents had stronger negative associations with deviant peer affiliation for European American adolescents than for African American adolescents.

Neighborhood Comparisons Within Ethnic Group

To disentangle the effects of neighborhood context from those of ethnicity, we estimated two-group SEMs comparing low-risk and high-risk neighborhoods within each ethnic group. For European American adolescents, the unconstrained neighborhood model had acceptable fit (see Table 3). The indirect pathway from parental control to delinquency through deviant peer affiliation was significant for both low-risk and high-risk neighborhood types (low-risk Sobel Z = 2.92; high-risk Sobel Z = 3.17). Similarly, the indirect pathway from maternal support and delinquency through deviant peer association was significant for both low-risk and high-risk neighborhood groups (low-risk Sobel Z = 4.65; high-risk Sobel Z = 3.47). The unconstrained model standardized estimates for key variables can be seen in Fig. 3. The model fit was significantly worse for the constrained model, ∆χ² (21) = 96.11, p < .01, suggesting differences between adolescents living in high-risk versus low-risk neighborhoods. Follow-up analyses showed that the path between parental control and deviant peer affiliation differed significantly across the two neighborhood types, ∆χ (1) = 28.84, p < .01. The negative relationship between parental control and deviant peer affiliation was stronger in high-risk (β = -.11, p < .05) than in low-risk (β = −.06, p < .05) neighborhoods. Thus, having less parental control was more strongly associated with having deviant peers for European Americans in high-risk neighborhoods. In addition, the path between family structure and maternal support differed across groups, ∆χ (1) = 6.24, p < .05. Living with two biological parents was more strongly related to maternal support for youth in high-risk (β = .10, p < .05) than low-risk (β = .02, p > .05) neighborhoods. Fit indices for the final, partially constrained model are shown in Table 3.

Main model statistics for unconstrained paths comparing European Americans in low and high-risk neighborhoods. Note: All estimates are standardized, high-risk group estimates are in parentheses. Solid lines indicate paths that are significantly different between groups. For simplicity, paths for age and gender are not displayed. Results for these paths are available upon request. * < .05, ** < .01

For African Americans, the unconstrained neighborhood model had adequate fit. Model estimates for the key variables can be seen in Fig. 4. Surprisingly, the indirect pathways from maternal support and parental control to delinquency via deviant peer association were not significant for youth in either low- or high-risk neighborhoods. The fit of the fully constrained model was significantly worse, ∆χ²(18) = 39.56, p < .01, indicating differences in the model for African Americans from low-risk versus high-risk neighborhoods. However, only the path between family structure and deviant peer affiliation differed significantly between youth in high (β = −.10, p < .05) and low-risk (β = .01, p > .05) neighborhoods, ∆χ (1) = 4.55, p < .05. Living with both parents was significantly negatively associated with deviant peer affiliation in high-risk but not low-risk neighborhoods. The fit statistics for the final constrained model is displayed in Table 3.

Main model statistics for unconstrained paths comparing African Americans in low and high-risk neighborhoods. Note: All estimates are standardized, High-risk group estimates are in parentheses. Solid lines indicate paths that are significantly different between groups. For simplicity, paths for age and gender are not displayed. Results for these paths are available upon request. *<.05, ** <.01

Discussion

This study was designed to examine ethnic and neighborhood differences in the relationships between parenting practices, deviant peers, and delinquency. Findings indicated substantial similarities in pathways to delinquency for European American and African American adolescents. In both groups, there was a significant direct effect of maternal support on delinquency, as well as significant indirect effects of parental control and maternal support that operated through adolescents’ association with deviant peers. Additionally, paths from maternal support to deviant peers and from deviant peers to delinquency differed between ethnic groups, being stronger for European American than African American youth. Furthermore, the relationships of family and neighborhood characteristics to parenting and deviant peers differed between ethnic groups. In contrast, comparisons within ethnic group indicated few differences in the pathways to delinquency for youth living in high-risk versus low-risk neighborhoods; however, the differences that emerged varied by ethnic group. These findings illuminate the unique contributions of ethnicity and neighborhood context, as well as the complex interactions between them that need to be considered to illuminate variations in pathways to delinquency.

Indirect Pathways Among Parenting Practice, Deviant Peers, and Delinquency

As hypothesized, the relationships between parenting practices and delinquent behavior were mediated by deviant peers. Deviant peer affiliation fully mediated the relationship between parental control and delinquent behavior in both ethnic groups. African American and European American adolescents who were given more freedom to make their own decisions about everyday concerns (e.g., how to dress, choice of friends, television viewing) reported having more deviant friends, which in turn predicted higher levels of delinquency the following year. Other research has documented indirect effects of parent control on adolescent delinquent behavior though affiliation with deviant peers in both European American and African American adolescents (Chung and Steinberg 2006; Galambos et al. 2003). In adolescence, direct adult supervision decreases and adolescents have an increased opportunity to choose their own peers. Thus peers become an important influence on delinquent behavior and parenting effects become indirect. The relationship between maternal support and delinquency was partially mediated by deviant peer affiliation in both ethnic groups. Thus, higher maternal support was related to less association with deviant peers for African American and European American youth, which in turn predicted lower involvement in delinquent behaviors. This direct effect may occur as warm, effective parenting fosters self-control, reducing adolescent delinquent behavior directly (Hay 2001). Furthermore, maternal support indirectly reduces delinquency through reducing the likelihood that adolescents will associate with unconventional peers (Oxford et al. 2000). Taken together, the results from this study and previous research provide strong evidence for the proposed indirect path from parenting practices to delinquency.Footnote 2

Ethnic Group Differences

We also examined ethnic group differences in the relationships between parenting practices and delinquent behavior. As hypothesized, the effect of parental control on delinquency, which operated through deviant peers, was stronger for African American than European American youth. This suggests that stricter parental control is more beneficial for African American youth, consistent with several previous reports (Deater-Deckard et al. 1996; Lansford et al. 2004). The present findings show that the enhanced benefits of parental control for African American youth operate by reducing deviant peer affiliation. We also found that the association between maternal support and deviant peers was significantly stronger among European Americans, suggesting that maternal support is especially protective for that group. A potential explanation for this difference is the greater importance of extended family members among African Americans. These kin provide an additional source of support and socialization for African American youth, perhaps compensating for and reducing the impact of maternal support (Jarrett et al. 2010; Parke and Buriel 2006). Furthermore, previous research has indicated that paternal support is instrumental in reducing delinquent behavior in African American samples (Bean et al. 2006). Although maternal support was important for reducing deviant peer association among African American youth in the present study, the support provided by other family members could have weakened these effects.

Another interesting finding was that the positive relationship between deviant peer affiliation and delinquency was stronger among European Americans, suggesting that deviant peers have a greater impact on delinquent behavior for them. Caution is warranted as this result may be an artifact of the deviant peer measure we used, which focused on substance use among friends. Given the lower levels of alcohol and tobacco use among African American youth compared to European American youth (Center for Disease Control and Prevention 2010), use of these substances may be more closely linked to delinquency for European Americans, resulting in stronger associations between deviant peers and delinquency for that group. Despite this minor difference in strength, the impact of deviant peers on delinquency was significant and positive in both groups, showing ethnic similarities in basic processes.

Neighborhood Differences in Pathways: Parent and Peer Effects

We also explored the ways that that the neighborhood context might influence pathways to delinquency for both African American and European American youth. We hypothesized that youth residing in higher risk neighborhoods would report more parental control as parents seek to protect adolescents. This was supported in both ethnic groups by significant relationships between neighborhood quality variables (parental reports of neighborhood quality, economic hardship, and adolescent reports of neighborhood cohesion) and parental control. Among European Americans, parents’ report of neighborhood problems and economic hardship (indexed by receiving public assistance) were positively associated with parental control, consistent with prior findings that more authoritarian parenting styles are found in riskier neighborhoods (Cantillion 2006). However, these paths were not significant for African American adolescents, indicating a lesser role of these variables for them. This was the case even though African American parents perceived more neighborhood problems than European American Parents. African American families in poverty typically live in poorer quality neighborhoods than European American families of similar socioeconomic status (Sampson and Wilson 1995), which may increase the amount of stress on African American parents, making them less able to adjust their levels of behavioral control as neighborhood problems increase. The same process may explain the finding that economic hardship was associated positively with parental control only for European Americans. In contrast, a higher quality neighborhood, as indicated by adolescent reports of neighborhood cohesion, had a negative relationship with parental control for African American but not European American youth. Therefore, African American adolescents who resided in areas that had higher levels of neighborhood cohesion also reported that they were controlled less by parents. Again, a high emphasis on interdependence and collective goal sharing for African American parents (Hill 2006), as well as emphasis on expanded kin networks within highly cohesive neighborhoods (Jarrett et al. 2010), may facilitate higher levels of collective efficacy and social monitoring for African American youth. Taken together, these results indicate that, as neighborhood quality increases, parental control decreases. Different aspects of neighborhood quality affect behavioral control for African American and European American youth.

The Role of Neighborhood Context

Finally, we examined the ways that the relationships between parenting, peers, and delinquency might operate differently for youth residing in high-risk and low risk neighborhoods, and whether these relationships were similar for African American and European American youth. We hypothesized that the relationship between deviant peer association and parenting practices would be stronger for youth in high-risk compared to low-risk neighborhoods. This hypothesis was supported for European American youth, for whom parental control had a stronger negative relationship to deviant peer affiliation in high-risk neighborhoods compared to low-risk neighborhoods. Thus, for European Americans, behavioral control appears to be especially protective against deviant peer association in higher risk neighborhoods. For African Americans, the relationship between behavioral control and deviant peer association was significant for both neighborhood types, but was not significantly different between groups. This suggests that there are may be sufficient opportunities for deviant peer contacts in both high risk and low-risk neighborhoods where African Americans reside, so that parental control is helpful in deterring misconduct. Furthermore, in particularly high risk neighborhoods, African American parents may rely more on extended kin for extra support in child care (e.g., Brewster and Padavic 2002; Johnson 2000), which would counteract the effect of the greater number of deviant peers.Footnote 3

Our findings have important implications for theory. First, the indirect effects of parenting on delinquency underscore the importance of considering of multiple social contexts as playing a role in adolescent behavior, consistent with ecological and contextual perspectives on development (Brofenbrenner 1994; see also Lerner 1991). The effects of parenting operated in part through affiliation with deviant peers, suggesting an important connection between peer and family contexts. Furthermore, the findings indicate that the neighborhood is an additional social context influencing delinquency. As proposed by social disorganization theory, neighborhood context is a distal factor that influences more proximal contexts of adolescent development including family and peers (Sampson and Groves 1989). The ethnic differences in the relationships among neighborhood context, parenting, and peers support Hill’s (2006) contention that ethnicity is a unique context separate from neighborhood which has both direct effects on how parents influence adolescents as well effects on how the neighborhood shapes the relationships between family and peer contexts.

Limitations and Future Directions

The current study draws on a national dataset that allowed an examination of youth from two ethnic groups who lived in diverse neighborhoods; the large sample ensured sufficient power to examine complex relationships. However, the study also has limitations. The measures for most variables were based on adolescents’ reports, which may have inflated some of the observed associations. Further, measures of neighborhood context and adolescent parental control had low internal consistency, and future research would benefit from more comprehensive measures of parental control as well as objective measures of neighborhood context. The deviant peer measure was also a limitation of this study. Asking adolescents about their peers’ participation in wider range of delinquent activities would be able to account for potential cultural sensitivity of specific deviant peer activities. Finally, we used a dichotomous measure of neighborhood type to examine the moderating effects of neighborhood context; additional insights might be gained by employing a more differentiated measure.

Future studies should extend the present model to other ethnic groups such as Latino or Asian Americans, for whom pathways to delinquency may differ. Extension to these ethnic groups may also allow researchers to include acculturation processes for immigrant youth, as the relationships between individual, family, and community factors and delinquency may be distinct for these youth. Of further interest may be the role of fathers and other kin. Family structure appears to have an important effect on deviant peer association and parenting in both ethnic groups, so including information on fathers (e.g., paternal support) may improve the predictive model. It also may be useful to examine additional parenting practices (e.g., psychological control).

Conclusion

Although previous research has shown that predictors of delinquent behavior may differ by ethnic or neighborhood contexts, few studies have examined both contexts simultaneously. Our findings indicate that, for African American and European American adolescents, the pathways from parenting to delinquency are similar and operate primarily through affiliation with deviant peers. However, ethnic differences were found in the strength of these relationships and in the effects of contextual predictors on both parenting and deviant peers. The few differences based on neighborhood context varied by ethnicity. Consistent with contextualist theories (Hill 2006), this suggests that ethnicity and neighborhood ecology are distinct and both need to be to be examined in studies of adolescent behavior. The findings indicate that intervention efforts to curb delinquency should focus on strengthening effective parenting and minimizing deviant peer affiliation opportunities, regardless of context. However, such interventions may need to emphasize distinct factors that are specific to ethnic groups and for youth in high- versus low-risk neighborhoods.

Notes

A Wald test was necessary to test this hypothesis due to the full mediation of the relationship between parental control and delinquency via deviant peers.

In the initial analyses which were done separately for each ethnic group, indirect effects of parenting practices on delinquency were found for both groups. Thus, it is puzzling that these effects were no longer significant when the African American youth divided based on residence in high-risk versus low-risk neighborhoods. One possible explanation is the reduced statistical power in the neighborhood models.

One other neighborhood difference emerged for African American youth only. For African American youth, living in a two-parent home deters affiliation with deviant peers in high-risk, but not low-risk neighborhoods. A two-parent family, especially in high-risk neighborhoods, may provide greater monitoring and parental support, reducing opportunities and motivations to affiliate with deviant peers. African American single-mother households receive less extended kin support compared to married couple households (Miller-Cribbs and Farber, 2008), which may reduce the family’s ability to shield adolescents from contact with deviant peers. Furthermore, father figures are particularly important for curbing delinquent behavior in African American youth (Bean et al. 2006), indicating that father figures may be important for reducing deviant peer association.

References

Amato, P., & Fowler, F. (2002). Parenting practices, child adjustment, and family diversity. Journal of Marriage & Family, 64, 703–716. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00703.x.

Anderson, L. S. (2008). Predictors of parenting stress in a diverse sample of parents of early adolescents in high-risk communities. Nursing Research, 57, 340–350. doi:10.1097/01.NNR.000021502922227.87.

Barrett, P. (2006). Structural equation modeling: Adjudging model fit. Personality and Individual Differences, 42, 815–824. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.018.

Bean, R. A., Barber, B. K., & Crane, D. R. (2006). Parental support, behavioral control and psychological control among African American youth. Journal of Family Issues, 27, 1335–1355. doi:10.1177/0192513X06289649.

Beyers, J. M., Bates, J. E., Pettit, G. S., & Dodge, K. A. (2003). Neighborhood structure, parenting processes, and the development of youths’ externalizing behaviors: A multilevel analysis. American Journal of Community Psychology, 31, 35–53. doi:10.1023/A:1023018502759.

Blum, R., Beuhring, T., Shew, M., Bearinger, L., Sieving, R., & Resnick, M. (2000). The effects of race/ethnicity, income, and family structure on adolescent risk behaviors. American Journal of Public Health, 90, 1879–1884. doi:10.2105/AJPH.90.12.1879.

Brewster, K. L., & Padavic, I. (2002). No more kin care? Change in black mothers’ reliance on relatives for child care, 1977–94. Gender and Society, 16, 546–563. doi:10.1177/0891243202016004008.

Brody, G. H., Ge, X., Conger, R. D., Gibbons, F. X., Murry, V. M., Gerrard, M., et al. (2001). The influence of neighborhood disadvantage, collective socialization, and parenting on African American children’s affiliation with deviant peers. Child Development, 72, 1231–1246. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00344.

Brofenbrenner, U. (1994). Ecological models of human development. In T. Husten & T. N. Poslethewaite (Eds.), International encyclopedia of education (2nd ed., Vol. 3, pp. 1643–1647). New York: Elsevier Science.

Brown, B. B., & Bakken, J. (2011). Parenting and peer relationships: Reinvigorating research on family-peer linkages in adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 153–165. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00720.x.

Bynum, M. S., & Kotchick, B. A. (2006). Mother-adolescent relationship quality and autonomy as predictors of psychosocial adjustment among African American adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 15, 529–542. doi:10.1007/s10826-006-9035-z.

Byrne, B. M., Shavelson, R. J., & Muthén, B. (1989). Testing for the equivalence of factor covariance and mean structures: The issue of partial measurement invariance. Psychological Bulletin, 105, 456–466. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.105.3.456.

Byrnes, H. F., Miller, B. A., Chen, M., & Grube, J. W. (2011). The roles of mothers’ neighborhood perceptions and specific monitoring strategies in youths’ problem behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 347–360. doi:10.1007/s10964-010-9538-1.

Cantillion, D. (2006). Community social organization, parents and peers as mediators of perceived neighborhood block characteristics on delinquent and prosocial activities. American Journal of Community Psychology, 37, 111–127. doi:10.1007/s10464-005-9000-9.

Ceballo, R., & McLoyd, V. C. (2002). Social support and parenting in poor, dangerous neighborhoods. Child Development, 73, 1310–1321. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00473.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2010). Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2009. MMWR, 59 [No SS-5] Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Chantala, K., & Tabor, J. (1999). Strategies to perform a design-based analysis using the Add Health data. Chapel Hill: Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Chung, H. L., & Steinberg, L. (2006). Relations between neighborhood factors, parenting behaviors, peer deviance and delinquency among serious juvenile offenders. Developmental Psychology, 42, 319–331. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.319.

Conger, R. D., Conger, K. J., Elder, G. H., Lorenz, F. O., Simons, R. L., & Whitbeck, L. B. (1992). A family process model of economic hardship and adjustment of early adolescent boys. Child Development, 63, 526–541. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01644.x.

Conger, R. D., Wallace, L. E., Sun, Y., Simons, R. L., McLoyd, V. C., & Brody, G. H. (2002). Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology, 38, 179–193. doi:10.1037//0012-1649.38.2.179.

de Kemp, R. A. T., Scholte, R. H. J., Overbeek, G., & Engls, R. C. M. E. (2006). Early delinquency: The role of home and best friends. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 33, 488–510. doi:10.1177/0093854806286208.

Deater-Deckard, K., Dodge, K. A., Bates, J. E., & Pettit, G. S. (1996). Physical discipline among African American and European American mothers: Links to children’s externalizing behaviors. Developmental Psychology, 32, 1065–1072. doi:10.1037//0012-1649.32.6.1065.

Demuth, S., & Brown, S. L. (2004). Family structure, family processes, and adolescent delinquency: The significance of parental absence versus parental gender. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 41, 58–81. doi:0.1177/0022427803256236.

Dodge, K. A., Greenberg, M. T., Malone, P. S., & Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. (2008). Testing an idealized dynamic cascade model of the development of serious violence in adolescence. Child Development, 79, 1907–1927. doi:10.111/j.1467-8624.2008.01233.x.

Dornbusch, S., Carlsmith, J., Bushwall, S., Ritter, P., Lederman, H., Hasorf, A., et al. (1985). Single parents, extended households, and the control of adolescents. Child Development, 56, 326–341. doi:10.2307//1129723.

Dornbusch, S., Ritter, P., Leiderman, P., Roberts, D., & Fraleigh, M. (1987). The relation of parenting style to adolescent school performance. Child Development, 58, 1244–1257. doi:10.2307//1130618.

Duniform, R., & Kowaleski-Jones, L. (2002). Who’s in the house? Race differences in cohabitation, single parenthood, and child development. Child Development, 73, 1249–1264. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00470.

Eamon, M. K. (2001). Poverty, parenting, peer and neighborhood influences on young adolescent antisocial behavior. Journal of Social Service Research, 28, 1–23. doi:10.1300/J079v28n01_01.

Elliott, D. S., Wilson, W. J., Huzinga, D., Sampson, R. J., Elliott, A., & Rankin, B. (1996). The effects of neighborhood disadvantage on adolescent development. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 33, 389–426. doi:10.1177/0022427896033004002.

Furstenberg, F. F., Cook, T. D., Eccles, J., Elder, G. H., & Sameroff, A. (Eds.). (1999). Managing to make it: Urban families and adolescent success. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Galambos, N. L., Barker, E. T., & Almedia, D. M. (2003). Parents do matter: Trajectories of change in externalizing and internalizing problems in early adolescence. Child Development, 74, 578–594. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.7402017.

Garcia-Coll, C., Lamberty, G., Jenkins, R., McAdoo, H. P., Crnic, K., Wasik, B. H., et al. (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development, 67, 1891–1914.

Goldstein, S. E., Davis-Kean, P. E., & Eccles, J. S. (2005). Parents, peers and problem behavior: A longitudinal investigation of the impact of relationship perceptions and characteristics on the development of adolescent problem behavior. Developmental Psychology, 41, 401–413. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.41.2.401.

Gorman-Smith, D., Tolan, P. H., & Henry, D. B. (2000). A developmental-ecological model of the relation of family functioning to patterns of delinquency. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 16, 169–198. doi:10.1023/A:1007564505850.

Gottfredson, M. R., & Hirschi, T. (1990). A general theory of crime. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Gottfredson, D. C., McNeil, R. J., III, & Gottfredson, G. D. (1991). Social area influences on delinquency: A multilevel analysis. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 28, 197–226. doi:10.1177/0022427891028002005.

Gray, M., & Steinberg, L. (1999). Unpacking authoritative parenting: Reassessing a multidimensional construct. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61, 599–610. doi:10.2307/353561.

Griffin, K. W., Botvin, G. J., Scheier, L. M., Diaz, T., & Miller, N. L. (2000). Parenting practices as predictors of substance use, delinquency and aggression among urban minority youth: Moderating effects of family structure and gender. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 14, 174–184. doi:10.1037//0893-164X.14.2.174.

Gutman, L. M., McLoyd, V. C., & Tokoyawa, T. (2005). Financial strain, neighborhood stress, parenting behaviors and adolescent adjustment in urban African American families. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 15, 425–499. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2005.00106.x.

Hagan, J. (1989). Structural criminology. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Hay, C. (2001). Parenting, self-control and delinquency: A test of self-control theory. Criminology, 39, 707–736.

Haynie, D. L., & Osgood, D. W. (2005). Reconsidering peers and delinquency: How do peers matter? Social Forces, 84, 1109–1130. doi:10.1353/sof.2006.0018.

Hill, N. (2006). Disentangling ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and parenting: Interactions, influence and meaning. Vulnerable Child and Youth Studies, 1, 114–124. doi:10.1080/17450120600659069.

Hirschi, T. (1969). Causes of delinquency. Berkley, CA: University of California Press.

Hoefer, S. M., & Hoffman, L. (2007). Statistical analysis with incomplete data: A developmental perspective. In T. D. Little, J. A. Boivard, & N. A. Card (Eds.), Modeling ecological and contextual effects in longitudinal studies of human development (pp. 13–32). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hoeve, M., Dubas, J. S., Eischelsheim, V. I., van der Laan, P. H., Smeenk, W., & Gerris, J. R. M. (2009). The relationship between parenting and delinquency: A meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Behavior, 37, 749–775. doi:10.1007/s10802-009-9310-8.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118.

Ingoldsby, E. M., Shaw, D. S., Winslow, E., Schonberg, M., Gilliom, M., & Criss, M. M. (2006). Neighborhood disadvantage, parent-child conflict, neighborhood peer relationships, and early antisocial behavior problem trajectories. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34, 303–319. doi:10.1007/s10802-006-9026-y.

Jarrett, R. L., Jefferson, S. R., & Kelley, J. N. (2010). Finding community in family: Neighborhood effects and African American kin networks. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 41, 299–328.

Johnson, C. L. (2000). Perspectives on American kinship in the later 1990s. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62, 623–639. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00623.x.

Johnston, L. D., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2010). HIV/AIDS: Risk & protective behaviors among American young adults, 2004–2008 (NIH Publication No. 10-7586). Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Kline, R. B. (1998). Principles and practices of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford.

Kotchick, B. A., & Forehand, R. (2002). Putting parenting in perspective: A discussion of contextual factors that shape parenting practices. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 11, 255–269. doi:10.1023/A:1016863921662.

Kowaleski-Jones, L., & Dunifon, R. (2006). Family structure and community context: Evaluating influences on adolescent outcomes. Youth & Society, 38, 110–130. doi:10.1177/0044118X05278966.

Lamborn, S. D., Dornbusch, S. M., & Steinberg, L. (1996). Ethnicity and community context as moderators of the relations between family decision making and adolescent adjustment. Child Development, 67, 283–301. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.ep9605280309.

Lansford, J. E., Deater-Deckard, K., Dodge, K. A., Bates, J. E., & Pettit, G. S. (2004). Ethnic differences in the link between physical discipline and later adolescent externalizing behaviors. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45, 801–812. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00273.x.

Lerner, R. M. (1991). Changing organism-context relations as the basic process of development: A developmental contextual perspective. Developmental Psychology, 27, 27–32. doi:10.1037//0012-1649.27.1.27.

Leventhal, T., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2000). The neighborhoods they live in: The effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 309–337. doi:10.1037//0033-2909.126.2.309.

MacCallum, R. C., & Austin, J. T. (2000). Applications of structural equation modeling in psychological research. Annual Review of Psychology, 51, 201–226. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.201.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., Hoffman, J. M., West, S. G., & Sheets, V. (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7, 83–104. doi:10.1037//1082-989X.7.1.83.

Miller-Cribbs, J. E., & Farber, N. B. (2008). Kin networks and poverty among African Americans: Past and present. Social Work, 53, 43–51. doi:10.1093/sw/53.1.43.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2010). Mplus user’s guide (6th Ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. (2009). Juvenile Arrests, 2008. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Ogbu, J. U. (1981). Origins of human competence: A cultural-ecological perspective. Child Development, 52, 413–429. doi:10.2307/1129158.

Oxford, M. L., Harachi, T. W., Catalano, R. F., & Abbott, R. D. (2000). Preadolescent predictors of substance initiation: A test of both the direct and mediated effect of family social control factors on deviant peer associations and substance initiation. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 27, 599–616.

Parke, R., & Buriel, R. (2006). Socialization in the family: Ethnic and ecological perspectives. In N. Eisenberg (Ed.), The handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., Vol. 3, pp. 429–504). New York: Wiley.

Parker, J. S., & Benson, M. J. (2004). Parent-adolescent relations and adolescent functioning: Self-esteem, substance abuse, and delinquency. Adolescence, 39, 519–530.

Patterson, G. R., DeBaryshe, B., & Ramsey, E. (1990). A developmental perspective on antisocial behavior. American Psychologist, 44, 329–335. doi:10.1037//0003-066X.44.2.329.

Patterson, G. R., Dishion, T. J., & Yoerger, K. (2000). Adolescent growth in new forms of problem behavior: Macro- and micro-peer dynamics. Prevention Science, 1, 3–13. doi:10.1023/A:1010019915400.

Piquero, A. R., & Brame, R. (2008). Assessing the race-/ethnicity-crime relationship in a sample of serious adolescent delinquents. Crime & Delinquency, 54, 390–422. doi:10.1177/0011128707307219.

Rankin, B. H., & Quane, J. M. (2002). Social contexts and urban adolescent outcomes: The interrelated effects of neighborhoods, families, and peers on African American youth. Social Problems, 49, 79–100. doi:10.1525/sp.2002.49.1.79.

Sampson, R. J., & Groves, W. B. (1989). Community structure and crime: Testing social-disorganization theory. American Journal of Sociology, 94, 774–802. doi:10.1086/22906.

Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (1994). Urban poverty and the family context of delinquency: A new look at structure and process in a classic study. Child Development, 65, 523–540. doi:10.2307/1131400.

Sampson, R. J., Morenoff, J. D., & Gannon-Rowley, T. (2002). Assessing “neighborhood effects”: Social processes and new directions in research. Annual Review of Sociology, 28, 443–478. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.28.110601.141114.

Sampson, R. J., & Wilson, W. J. (1995). Toward a theory of race, crime, and urban inequality. In J. Hagan & R. D. Peterson (Eds.), Crime and inequality (pp. 37–54). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Scaramella, L. V., Conger, R. D., Spoth, R., & Simons, R. L. (2002). Evaluation of a social contextual model of delinquency: A cross-study replication. Child Development, 73, 175–195. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00399.

Simons, R. L., Simons, L. G., Burt, C. H., Brody, G. H., & Cutrona, C. (2005). Collective efficacy, authoritative parenting and delinquency: A longitudinal test of a model integrating community and family-level processes. Criminology, 43, 989–1029. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2005.00031.x.

Trejos-Castillo, E., & Vazsonyi, A. T. (2009). Risky sexual behaviors in first and second generation immigrant youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 719–731. doi:10.1007/s10964-008-9369-5.

Walker-Barnes, C. J., & Mason, C. A. (2001). Ethnic differences in the effect of gang involvement and gang delinquency: A longitudinal, hierarchical, linear modeling perspective. Child Development, 72, 1814–1831. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00380.

Weaver, S. R., & Prelow, H. M. (2005). A mediated-moderation model of maternal parenting style, association with deviant peers, and problem behaviors in urban African American and European American adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 14, 343–356. doi:10.1007/s10826-005-6847-1.

Wolff, J. M., & Crockett, L. J. (2011). The role of deliberative decision making, parenting and friends in adolescent risk behaviors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 1607–1622. doi:10.1007/s10964-011-9644-8.

Wright, J. P., & Cullen, F. T. (2001). Parental efficacy and delinquent behavior: Do control and support matter? Criminology, 39, 677–706. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2001.tb00937.x.

Zimmerman, G. M., & Messner, S. F. (2011). Neighborhood context and nonlinear peer effects on violent crime. Criminology, 49, 873–903. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2011.00237.x.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by grant # HD R01 039438 from NICHD to L. Crockett and S. Russell. This research uses data from Add Health, a program project designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris, and funded by a grant P01-HD31921 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 17 other agencies. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth). Address correspondence to A. Deutsch, arielle.deutsch@gmail.com. Portions of this paper were presented at the 2010 meeting of the Society for Research on Adolescence, Philadelphia, PA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Deutsch, A.R., Crockett, L.J., Wolff, J.M. et al. Parent and Peer Pathways to Adolescent Delinquency: Variations by Ethnicity and Neighborhood Context. J Youth Adolescence 41, 1078–1094 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9754-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9754-y