Abstract

Despite a growing body of research on parental management of peer relationships, little is known about the relationship between parental management of peers and early adolescents’ social skills or the precursors to parental management of peer relationships. The goals of this short-term longitudinal investigation were to examine the relationship between parental management of peers (consulting and guiding), conflict about peers, and adolescents’ social skills (cooperation, assertion, responsibility, empathy, and self-control) and to examine potential precursors (goals of improving peer relationships and beliefs about authority over peer relationships) to parental management of peer relationships. A predominantly White sample (71%) of 75 seventh-graders (57% female) and their primary caregivers participated in the 9-month investigation. Caregivers completed questionnaires regarding goals of improving their adolescents’ peer relationships, beliefs about parental authority over peer relationships, parental management of peers, and adolescents’ social skills. Adolescents completed questionnaires regarding their social skills. Path analyses suggest that a greater number of caregivers’ goals of improving peer relationships and higher beliefs about parental authority over peers were related to higher levels of consulting, guiding, and conflict about peers. Higher levels of conflict about peers in conjunction with higher levels of consulting were related to lower levels of assertion and responsibility in peer relationships over time. When parents reported having a greater number of goals of improving peer relationships, adolescents reported higher levels of cooperation, assertion, empathy, and self control over time. Findings suggest that caregivers’ goals and beliefs are important in predicting parental management of peer relationships and adolescents’ social skills over time, and that conflict about peers undermines caregivers’ efforts to be positively involved in adolescents’ peer relationships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in parental management of peer relationships during the adolescent period (Mounts 2000, 2001, 2004; Tilton-Weaver and Galambos 2003; Updegraff et al. 2001). Earlier investigations of adolescents focused on the relationship between parental management of peers and academic achievement or problem behavior (Mounts 2001, 2004, 2007). However, there is little research that examines parental management of peer relationships and social skills (Kan and McHale 2007; Ladd and Pettit 2002).

During early adolescence, increasing time is spent with peers and adolescents place increasing importance on peer relationships (Brown and Larson 2009). Moreover, the increasing complexity of peer relationships during the early adolescent period places more demands on social skills in comparison with peer relationships during early or middle childhood (Brown & Larson). Furthermore, during the early adolescent period, more emphasis is placed on intimacy and loyalty within the context of friendships. Intimacy and loyalty require more sophisticated social skills than aspects of friendships, such as participating in enjoyable activities together, which are a feature of younger children’s peer relationships (Rubin et al. 2006). Thus, more research is needed to examine the way that parents facilitate the development of social skills during the early adolescent period. Using a short-term longitudinal design, the current investigation examines the relationship between parental management of peer relationships and adolescents’ social skills in a sample of early adolescents.

Parental Management of Peer Relationships

Ladd and Pettit (2002) describe parental influence on peers as being through indirect influences, such as parenting style or attachment, or through direct influences, such as specific parenting practices aimed at relationships with peers. Parke and Buriel (2006) suggest that parents are directly involved in peer relationships in two ways. First, they are involved in peer relationships through direct instruction such as consulting about peer relationships. Consulting is defined as explicit instruction regarding social relationships or problem-solving regarding peers (Ladd and Pettit 2002; Parke and Buriel 2006; Parke et al. 2003). Consulting can occur in response to specific incidences involving peers or it can occur as parents see a need for preparing children for the possibility of having particular problems with peers (Ladd and LeSieur 1995). In this investigation, the consulting measure used assesses parental peer advice in response to specific incidences involving peers. Second, parents are directly involved in peer relationships through regulating peer interactions (Parke and Buriel 2006). Although this function is likely to change as children age, there is evidence that parents continue to regulate peer relationships during the adolescent period. Previous investigations have used the term “mediating” to describe regulatory functions (Ladd and Pettit 2002; Mounts 2004, 2007; Parke et al. 2003). Because the term “mediating” is used widely in the psychological literature in reference to statistical relationships, the use of “mediating” is likely to cause confusion. Thus, the term “guiding” will be used in this investigation to refer to the regulatory aspects of parental management of peer relationships.

Consulting

There are several investigations that suggest that consulting is related to social skills. In a study with preschool children, Laird et al. (1994) found a positive relationship between mothers’ and preschoolers’ conversations about peers and preschoolers’ social competence. Similarly, in a study of preschool children, Mize and Pettit (1997) examined maternal social coaching. Results suggested that higher levels of social coaching were related to more positive social skills and higher levels of peer acceptance. The abovementioned investigations suggest a positive association between consulting and children’s social skills. However, given the young ages of the children, it is unclear whether this pattern of results would occur for early adolescents as well. This is particularly true because advice by parents during this developmental period might be construed by adolescents as an intrusion on their growing need for autonomy. Nevertheless, in an investigation of early adolescents, Mounts (2004) found that higher levels of consulting were related to more positive friendship quality. This adds support for the notion that consulting during the early adolescent period is related to positive social skills. Thus, in this investigation it was hypothesized that higher levels of consulting would be related to more positive social skills.

Guiding

There are a limited number of investigations on the relationship between guiding and adolescents’ social skills. Youniss et al. (1992) reported that parents exerted a moderate amount of control in a situation where the friends were known to be troublemakers. Similarly, Furstenberg et al. (1999) reported that the majority of parents in their study told their adolescents not to hang around with specific peers as a strategy to prevent their children from being adversely affected by peers. Although these investigations document the existence of guiding, few investigations document the way that guiding is related to adolescents’ social skills. In one investigation of early adolescents, Mounts (2004) found that higher levels of guiding were related to more positive friendship quality; suggesting that management is related to social skills. In another investigation, Simpkins and Parke (2002) examined the relationship between maternal rules regarding peers and 6th-graders’ social adjustment. Results suggested that rules had differential effects on prosocial behavior. That is, when mothers had rules about playing with peers in parent supervised situations, adolescents received more prosocial nominations from their peers. In contrast, when mothers had many rules about managing conflict with peers and engaging in prosocial behavior with peers, adolescents received fewer prosocial nominations from their peers. Given the mixed pattern of results, it is not clear whether guiding is positively or negatively related to adolescents’ social skills. Indeed, it could be that higher levels of guiding are related to negative social outcomes because adolescents need autonomy in interactions with peers (Parke et al. 2003). Alternatively, guiding might provide important structure for adolescents’ peer relationships that supports the development of social skills. Thus, the relationship between guiding and adolescents’ social skills was examined with no hypothesized direction of relationship.

Conflict in Regard to Peer Relationships

A third variable related to parental management of peer relationships, conflict in regard to peer relationships, was also included in the investigation. While not management per se, conflict about peer relationships is likely to co-occur with parental management behaviors. The development of autonomy, especially autonomy from parents, is an issue that becomes increasingly important during adolescence (Steinberg 1990). Growth in adolescent autonomy might affect the extent to which adolescents believe that parental management of their peer relationships is appropriate and, thus, levels of conflict about peers.

There are two ways that conflict about peer relationships could be related to adolescents’ social skills. Conflict about peer relationships could be directly related to adolescents’ social skills. That is, conflicts between parents and adolescents might serve as a model for interactions with peers. Indeed, there is evidence for cross-generational similarity in emotional displays that is believed to emerge through parent–child interactions (Parke and Buriel 2006). Conflict might also function as a moderator of the relationship between parental management of peers and adolescents’ social skills. The self determination theory of Ryan and Deci (2000) suggests that adolescents’ well-being is enhanced when needs for autonomy are met. A number of previous investigations have found support for self determination theory, particularly the role of autonomy support, and school success (e.g. Grolnick et al. 1991; Grolnick et al. 2002). More recently, there has been an interest in applying self determinism to understanding linkages between parenting and peer relationships during adolescence (Soenens and Vansteenkiste 2005). Parental attempts to intervene in adolescents’ peer relationships might inadvertently impinge on adolescents’ growing need for autonomy and, thereby, undermine adolescents’ social skills. Higher levels of conflict about peers in conjunction with consulting and guiding might reflect less autonomy support on the part of parents. As such, higher levels of conflict about peers could moderate the relationship between consulting and guiding and adolescents’ social skills. In this investigation, it was hypothesized that higher levels of conflict about peer relationships would be related to poorer social skills in adolescents. In addition, using self determination theory as a guide, the interaction between conflict about peers and consulting and guiding will be examined. Thus, it is hypothesized that higher levels of conflict about peers in conjunction with consulting and guiding would be related to lower levels of social skills. In contrast, lower levels of conflict about peers in conjunction with consulting and guiding would be related to higher levels of social skills.

Predictors of Parental Management of Peer Relationships

There is limited consideration of the reasons why parents manage peer relationships during this developmental period (Tilton-Weaver and Galambos 2003). Based on previous conceptualizations of parental management of peers during adolescence (Mounts 2008; Tilton-Weaver and Galambos 2003), there are two factors that could predict parental management of peer relationships. The goals that parents have for improving their adolescents’ peer relationships might lead parents to manage of peer relationships. In addition, parental beliefs about their authority over peer relationships might also predict parental management of peers. Thus, this investigation examined parental goals for improving peer relationships and parental beliefs about authority over peer relationships as two factors that could predict parental management of peer relationships.

Parental Goals for Improving Peer Relationships

Parental goals of improving adolescents’ peer relationships are one factor that is hypothesized to contribute to parental management of peers (Mounts 2008). Yet, there is little research that examines whether this is, in fact, the case. Parents might have several goals that focus on improving peer relationships. These might include avoiding getting hurt by other peers or being popular with peers. Some research suggests that when parents reported goals of improving their children’s peer relationships, they were more likely to be engaged in parenting practices that focused on peer relationships (Mounts 2008). In this investigation, it was hypothesized that when parents report a higher number of goals for improvement of peer relationships for their children they will also report higher levels of consulting and guiding in regard to peer relationships.

Parental Beliefs About Authority Over Peer Relationships

A second factor that might predict parental management of peers is parents’ beliefs (Tilton-Weaver and Galambos 2003; Way et al. 2007). Although there are several types of beliefs that might be related to parental management of peers, beliefs about authority over peer relationships might be particularly important as children become increasingly autonomous (Mounts 2008). Smetana and Asquith’s (1994) work suggests that adolescents believe that friendship selection is a personal choice over which their parents should have little authority. Parents, on the other hand, often believe that they have legitimate authority over friendships because the effects of adolescents’ friendships may carry over into other domains of the adolescents’ life, such as psychological, conventional, or moral concerns. Thus, it was hypothesized that higher beliefs in caregivers’ authority over peer relationships would be related to higher levels of consulting, guiding, and conflict in regard to peer relationships.

Current Investigation

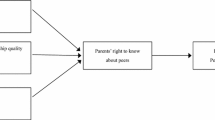

The current investigation examines a path model of the relationship between goals of improving peer relationships, beliefs about authority over peer relationships, parental management of peer relationships, and adolescents’ social skills. Given that discrepancies emerge in parents’ and adolescents’ reports of behavior (Collins 1991; Mounts 2007; Smetana 1988), the analyses include both adolescents’ as well as caregivers’ reports of adolescents’ social skills. First, the investigation examines whether goals of improving peer relationships and beliefs about parent authority over peer relationships predict parental management of peers. As suggested above, it was hypothesized that when caregivers report a greater number of goals for improving their children’s peer relationships they will also report higher levels of consulting and guiding in regard to peer relationships. In addition, it was hypothesized that the higher belief that parents have that they have authority over peer relationships, the more likely they will engage in consulting, guiding, and conflict in regard to peer relationships. Next, the longitudinal relationships between parental management of peers, conflict about peers, and parental reports of adolescents’ social skills were examined. As discussed previously, the relationship between guiding and adolescents’ social skills was examined with no hypothesized direction of relationship. It was hypothesized that higher levels of consulting would be related to more positive social skills. It was further hypothesized that higher levels of conflict about peer relationships would be related to poorer social skills in adolescents and that higher levels of conflict about peers would moderate the relationships between consulting, guiding, and adolescents’ social skills. Finally, the longitudinal relationships between parental management of peers, conflict about peers, and adolescents’ reports of social skills were examined. The hypothesized pattern of relationships for the adolescents’ reports of social skills was expected to be similar to the patterns described for the caregivers’ reports of social skills.

Method

Participants

Seventy-five seventh-graders and their primary caregivers participated in the investigation. The adolescent sample was 57% female and the mean age was 12.6 years. Three percent of the sample was African-American, 5% Asian, 16% Latino, 71% White, and 5% other (e.g. biracial, etc.). Approximately 23% of the caregivers had a high school education or less, 45% had some college or a 2-year degree, 26% had a 4-year degree, and 6% had more than a 4-year degree. Caregivers reported on their goals to improve their adolescents’ peer relationships, their beliefs about their authority over peer relationships and management of their adolescents’ peers at Time 1. Caregivers and adolescents reported on adolescents’ social skills at Time 1 and Time 2 (9 months later).

Procedure

The adolescents and caregivers were recruited from a middle school in a suburban area outside of a large Midwestern city. Letters outlining the study and inviting families to participate were sent home with the children and interested dyads returned the signed consent form to the school. Caregivers and adolescents completed questionnaires, separately, at home and mailed them back to the project office via self-addressed, stamped envelopes.

Measures

Goals of Improving Peer Relationships

Caregivers’ goals of improving peer relationships were assessed with a 9-item scale that asked caregivers to respond to items in which they reported their goals in improving peer relationships. For example, “How often in past three months did you get involved in your child’s peer relationships because you wanted your child to have better relationships with other kids?” Caregivers used a 6-point scale in which 0 = Never, 1 = Once, 2 = Twice, 3 = Three times, 4 = Four times, and 5 = 5 or more times. Cronbach’s alpha for caregivers at Time 1 was .73. Mean scores were calculated on this scale such that a high score on this scale suggested a high number of peer related goals.

Beliefs About Parental Authority Over Friendships

Caregivers’ beliefs about authority over peer relationships were assessed using items adapted and modeled after Tisak and Tisak (1990). Eighteen items were developed that assessed the degree to which parents believed they had a right to make rules regarding various types of friendship situations (Mounts 2008). An example item is, “Do you have a right to make rules regarding friendships because your child’s friends use bad language?” Caregivers used a 3-point scale in which 0 = No, 1 = Maybe, and 2 = Yes. Cronbach’s alpha was .82 in a previous investigation (Mounts 2008). A high score on this scale indicated that the caregiver believed that parents did have the right to make rules about adolescents’ friendships. Cronbach’s alpha for caregivers at Time 1 was .85.

Parental Management of Peer Relationships

Consulting and guiding were assessed with subscales from the Parental Management of Peers Inventory (PMPI) (Mounts 2004). For both subscales, caregivers and adolescents used a four point Likert-type scale with responses ranging from a score of 1 = “Strongly disagree” to 4 = “Strongly agree”.

Consulting

Consulting is a 10-item scale that assessed problem solving in regard to peer relationships. A sample item is “When your child is having a problem with a friend, he/she can ask you for help in solving it.” At Time 1, Cronbach’s alpha for Consulting for caregivers was .71. Mean scores were calculated and used in the analyses. A high Consulting score indicated higher levels of consulting.

Guiding

Guiding is an 18-item scale that assessed the extent to which parents use explicit direction about peer relationships. A sample item for this scale is “I talk to my child about the pros and cons of hanging around with certain people”. At Time 1, Cronbach’s alpha for Guiding for caregivers was .73. Mean scores were calculated and used in the analyses such that a higher score reflected a higher level of guiding.

Parent–Child Conflict About Peers

Using a 17-item measure, caregivers were asked to report the number of arguments that they had with their adolescent about peer relationships in the previous month (Mounts 2007). Caregivers used a six point scale such that responses ranged from a score of 0 = “0” to 6 = “5 or more times”. An example of the items was “Circle HOW OFTEN these conflicts occurred between you and your adolescent IN THE PAST MONTH. My adolescent and I had an argument because I did not like my child’s behavior when he/she was with friends”. Cronbach’s alpha for the scale for the caregivers at Time 1 was .77.

Social Skills

The Social Skills Rating Scale (Gresham and Elliott 1990) was used to assess levels of cooperation, assertion, responsibility, empathy, and self-control. The SSRS is a normed and standardized scale that assesses children’s social skills. The 52 item parent form was completed by caregivers. The adolescent form contained 39 items.

Cooperation

The cooperation subscale assessed behaviors such as helping or sharing with others. Cronbach’s alpha was .80 for Time 1 and .73 for Time 2 for the caregivers and Cronbach’s alpha was .72 for Time 1 and .76 for Time 2 for the adolescents.

Assertion

The assertion subscale assessed initiation of interactions such as introducing oneself. Cronbach’s alpha was .73 at Time 1 and .72 at Time 2 for caregivers and Cronbach’s alpha was .63 at Time 1 and .71 at Time 2 for the adolescents.

Responsibility

The responsibility subscale assessed following social rules, such as rules for a game. This subscale was completed by the caregivers only. Cronbach’s alpha was .69 at Time 1 and .65 at Time 2 for the caregivers.

Empathy

The empathy subscale assessed adolescents’ empathy toward peers and was completed only by the adolescents. Cronbach’s alpha was .68 at Time 1 and .86 at Time 2 for the adolescents.

Self-Control

The self-control subscale assessed behavior in situations that involve conflict, such as responding to teasing, and in non-conflict situations, such as taking turns. Cronbach’s alpha was for Time 1 was .79 and .74 for Time 2 for the caregivers and Cronbach’s alpha for Time 1 was .72 and .76 at Time 2 for the adolescents.

Results

Means and standard deviations of the major variables are presented in Table 1. Intercorrelations of the major variables are presented in Table 2. Three sets of hierarchical regression analyses were used to examine the research questions. Gender was dummy coded (0 for boys and 1 for girls) and entered as a predictor in all analyses.

Relationship Between Caregivers’ Goals of Improving Peer Relationships, Caregivers’ Beliefs About Authority Over Peer Relationships, Caregivers’ Reports of Management of Peer Relationships, and Caregivers’ Reports of Conflict About Peers

The first set of regression analyses examined the relationship between caregivers’ Time 1 reports of goals of improving peer relationships, caregivers’ Time 1 beliefs about authority over peer relationships, caregivers’ Time 1 reports of management of peers, and caregivers’ Time 1 reports of conflict about peers. Gender was entered first in the regression analysis, followed by goals of improving peer relationships and beliefs about authority over Peer relationships.

Results for the first set of regression analyses are presented in Table 3. Caregivers who reported a greater number of goals toward improving peer relationships also reported higher levels of consulting. In addition, caregivers who reported a greater number of goals toward improving peer relationships also reported lower levels of conflict about peers (at a trend level). Caregivers who believed that they had more authority over adolescents’ peer relationships reported higher levels of guiding in regard to peer relationships and higher levels of conflict with their adolescents about peer relationships.

Relationship Between Caregivers’ Reports of Management of Peer Relationships, Caregivers’ Reports of Conflict About Peers, and Caregivers’ Reports of Social Skills

The second set of regression analyses in the path model examined the relationship between caregivers’ Time 1 reports of management of peers, caregivers’ Time 1 reports of conflict about peers, and caregivers’ Time 2 reports of adolescents’ social skills, controlling for caregivers’ Time 1 reports of adolescents’ social skills. Prior to the analyses, the consulting, guiding, and conflict variables were centered and two interaction terms were created. The Time 1 outcome was entered in the first step of the regression analyses along with gender. Goals of improving peer relationships and beliefs about authority over peer relationships were entered next. Consulting, guiding, and conflict about peers were entered in the third step of the analyses. The two interactions terms were entered in the final step.

Results of these analyses are presented in Table 4. Analyses suggested that higher levels of guiding in regard to peer relationships at Time 1 were related to lower levels of cooperation with peers at Time 2. There was a significant interaction between consulting and conflict about peers for assertion and responsibility. Simple slope analyses using techniques described in Aiken and West (1991) suggested that for assertion lower levels of conflict about peers in combination with higher levels of consulting were related to higher levels of assertion over time (Beta = .30, p < .05). In contrast, higher levels of conflict about peers in combination with higher levels of consulting were related to lower levels of assertion over time (Beta = −.45. p < .05). For responsibility, consulting was not related to responsibility when conflict about peers was low (Beta = .19, ns). However, similar to assertion, higher levels of conflict about peers in combination with higher levels of consulting were related to lower levels of responsibility over time (Beta = −.40, p < .05).

Relationship Between Caregivers’ Reports of Management of Peer Relationships, Caregivers’ Reports of Conflict About Peers, and Adolescents’ Reports of Social Skills

The third set of regression analyses in the path model examined the relationship between caregivers’ Time 1 reports of management of peers, caregivers’ Time 1 reports of conflict about peers, and adolescents’ Time 2 reports of their own social skills, controlling for adolescents’ Time 1 reports of their own social skills. Similar to the analyses described above, the Time 1 outcome was entered in the first step of the regression analyses along with gender. Goals of improving peer relationships and beliefs about authority over peer relationships were entered next. Consulting, guiding, and conflict about peers were entered in the third step of the analyses, followed by the interaction terms.

Results of these analyses are presented in Table 5. Analyses suggested that a greater number of goals of improving peer relationships at Time 1 as reported by caregivers were related to higher levels of Time 2 cooperation, assertion, empathy, and self-control as reported by adolescents. This relationship was maintained for cooperation, empathy, and self-control even with the addition of the parental management, conflict about peers, and interaction terms in the regression equation. In addition, higher levels of consulting at Time 1 as reported by caregivers were related to lower levels of cooperation at Time 2 as reported by adolescents. Similarly, higher levels of guiding at Time 1 as reported by caregivers were related to higher levels of assertion with peers at Time 2 as reported by adolescents (trend). Higher levels of conflict about peers with the caregiver at Time 1 were related to lower levels of empathy with peers at Time 2. Similar to the results when caregivers reported on social skills, there was a significant interaction between consulting and conflict about peers, at the trend level, for assertion and empathy. There was also a significant interaction between guiding and conflict about peers for assertion and self control, at the trend level.

Simple slope analyses using techniques described in Aiken and West (1991) suggested that for assertion, consulting was not related to assertion when conflict about peers was low (Beta = .19, ns). In contrast, similar to the results for caregivers’ reports of assertion, higher levels of conflict about peers in combination with higher levels of consulting were related to lower levels of assertion over time (Beta = −.38, p < .10). Consulting was not related to empathy when conflict about peers was low (Beta = .25, ns). However, similar to assertion, higher levels of conflict about peers in combination with higher levels of consulting were related to lower levels of empathy over time (Beta = −.40, p < .05). Guiding was not related to assertion when conflict about peers was low (Beta = .01, ns). In contrast, when conflict about peers was high, higher levels of guiding were related to higher levels of assertion over time (Beta = .62, p < .05). Finally, when conflict about peers was low higher levels of guiding were related to lower self control with peers (Beta = −.28, p < .10). However, guiding was not related to self control when conflict about peers was high (Beta = .26, ns).

Discussion

This investigation extends previous research on parental management of peer relationships to include a consideration of its association with adolescents’ social skills during a developmental period with increasing emphasis on peer relationships (Brown and Larson 2009; Rubin et al. 2006). Previous investigations examined the relationship between parental management of peer relationships and adolescents’ academic achievement and delinquent behavior (Mounts 2001, 2004, 2007). Yet, less is known about the relationship between parental management of peer relationships and adolescents’ social skills. Existing empirical and theoretical literature, primarily with younger children, suggests that parental management of peer relationships could support or undermine the development of children’s social skills (Mounts 2004; Parke et al. 2003; Simpkins and Parke 2002). Thus, this investigation examined the relationship between two aspects of parental management of peer relationships (guiding and consulting) and early adolescents’ social skills over a 9 month period. In addition, the role of conflict in parental management of peer relationships was examined. Given that conflict might emerge because parents and adolescents have different beliefs about who has authority over friendships (Smetana and Asquith 1994), this investigation considers the role of conflict about peer relationships in predicting adolescents’ social skills. Finally, this investigation expands earlier work on potential precursors of parental management of adolescents’ peer relationships (Mounts 2008; Tilton-Weaver and Galambos 2003). Results suggest that goals and beliefs play an important role in predicting parental management of peer relationships and parental management of peers is related to adolescents’ social skills over time.

Precursors to Parental Management of Peer Relationships

As hypothesized, the results suggest that caregivers who had a greater number of goals in regard to improving peer relationships were more likely to engage in consulting in regard to peer relationships. Having a greater number of goals of improving peer relationships was also related to having lower levels of conflict about peers. Additionally, higher beliefs about authority over peer relationships were related to higher levels of guiding in regard to peer relationships and higher levels of conflict about peers. Results of the current investigation add to existing research, such as the work of Way et al. (2007) who found evidence of variation in beliefs about peer relationships across different ethnic groups. The results also provide empirical support for several models that suggested that parental goals of improving peer relationships and beliefs about peer relationships are related to management of peers (Tilton-Weaver and Galambos 2003; Mounts 2008).

Results about the beliefs about authority over peer relationships are consistent with the work of Mounts and Kim (2009) who found evidence that parental beliefs about romantic relationships partners were related to parental management of romantic relationships. Smetana and Asquith’s (1994) work suggests differences in beliefs about parental authority based on different domains. Given the constraints of the small sample size, this investigation grouped all of the parents’ responses to beliefs about authority over peers into a single measure. Yet, some of the items that comprised the measure could be grouped into domains that more closely resemble Smetana and Asquith’s (1994) domains. For example, some of the items dealt with peers who engaged in behaviors with potential health risks, such as smoking. Future investigations might examine the way in which the separate domains might be related to consulting, guiding, and conflict about peers.

Parental Management of Peers and Adolescents’ Social Skills

Taken together, the results present modest evidence to suggest that the two aspects of parental management of peers are differentially related to early adolescents’ social skills over time and that those relationships are moderated, in part, by conflict about peer relationships. The results suggest that higher levels of guiding are associated with the development of social skills that allow adolescents to develop skills related to assertion within the relationships. In contrast, guiding appeared to have a negative effect on cooperation, which is needed to maintain relationships over time. Higher levels of guiding were related to higher adolescents’ reports of assertion over time. The interaction analyses suggested that higher levels of guiding were related to higher levels of assertion in peer relationships over time, but only when parents reported higher levels of conflict about peers. It could be that during the conflict process guiding behavior could be used as a model for assertiveness skills in relationships (Parke & Buriel, 2006), which adolescents then use in their own relationships with peers. Future investigations might examine parental management of adolescents’ peer relationships in conjunction with conflicts about peers using observational techniques to more closely examine these processes. Researchers might also look for parallels in interaction patterns between adolescents and their caregivers and adolescents and their friends.

Contrary to the hypotheses, higher levels of consulting were related to lower levels of cooperation over time as reported by adolescents. There is some suggestion in the literature that some aspects of parental management of peer relationships might be related to poorer social relationships (Parke et al. 2003; McDowell and Parke 2009). It could be that when parents engage in excessive amounts of management they are undermining the adolescents’ development of important skills that are needed for successful social interaction. Alternatively, Parke et al. (2003) also suggest that parental management could be associated with negative social outcomes because adolescents need autonomy in interactions with peers. Further support for this notion is seen in the results of the interaction analyses. For the most part, when consulting occurred in conjunction with higher levels of conflict about peers social skills deteriorated over time. However, when consulting occurred in conjunction with lower levels of conflict about peers social skills improved over time (or remained the same). The interaction results suggest that consulting, alone, does not necessarily have an adverse effect on social skills.

The results suggest that self determination theory might be useful in understanding the contradictory results often reported in the literature regarding parental management of peer relationships (Ryan and Deci 2000). As suggested earlier, the lower conflict situation might be indicative of parents’ facilitation of autonomy for adolescents. Thus, it is likely that when parental management of peer relationships occurs in conjunction with meeting the adolescents’ needs for self determination via autonomy support (the lower conflict situation) the relationship to social skills should be positive. In contrast, when parental management of peer relationships occurs in situations where parents are not meeting the adolescents’ needs for self determination (the higher conflict situation) the relationship should be negative. Indeed, that higher beliefs about parental authority over peer relationships was related to higher reports about conflicts regarding peers in this investigation is at least suggestive that parental support for autonomy may play a role in whether parental management of peer relationships is related positively or negatively to adolescents’ social skills. Although the measure of conflict about peers is likely related to caregivers’ levels of autonomy support, it is not a direct assessment of the autonomy support construct. Thus, future investigations should further consider the degree to which parents support adolescents’ needs for autonomy in conjunction with their management of peer relationships.

Goals of Improving Peer Relationships and Adolescents’ Social Skills

An unexpected finding emerged in the analyses that underscored the need for more in-depth investigations of parental management of peers during adolescence. As part of the path model, the caregivers’ goals related to improving peer relationships and caregivers’ beliefs about parental authority over peers were entered into the regression analyses when examining the relationship between parental management of peers, conflict about peers, and social skills. For the analyses involving the caregivers’ reports of management, caregivers’ reports of conflict about peers, and the adolescents’ reports of social skills, there was a significant relationship between having a greater number of goals of improving peer relationships and positive social skills. This relationship was not mediated by the parental management variables for cooperation, empathy, and self-control. It was, however, mediated by guiding for assertion. Taken together, these cross-informant results suggest that there are some key features of parental management of peer relationships that are not being assessed with the measures employed in this investigation. Future investigations should focus on identifying other ways in which caregivers are communicating their goals about improving peer relationships to early adolescents that are not being captured with current measures of parental management of peer relationships. Such investigations are likely to require assessments of adolescents’ behavior, parental goals of improving peer relationships, and parental management of peers more intensively, over shorter periods of time, in order to understand the ordering of the events.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although this investigation provides some evidence for a relationship between parental management of peers and adolescents’ social skills, one major limitation of the investigation is that it does not examine mechanisms that explain associations between guiding, consulting, conflict about peers, and adolescents’ social skills. Future investigations call for a more nuanced consideration of parental management of peers and potential statistical mediators between management and early adolescents’ social skills. Following Parke and Buriel (2006), consideration of whether children’s understanding of others’ emotions statistically mediates the relationship between consulting and social skills is needed. For instance, through consulting, parents might help early adolescents think about their emotions and peers’ emotions. Furthermore, they might help them identify strategies for dealing with emotions in peer situations and learn rules about emotional display with peers. Indeed, there is evidence for cross-generational similarity in emotional displays (Parke and Buriel 2006) that supports the notion of emotional learning as a possible statistical mediator between parental management of peers and children’s social competence.

Another way in which guiding and consulting might play a role in the development of adolescents’ social skills might be through the development of cognitive models of social relationships. Again, there is evidence that parental models of social relationships are similar to children’s models (Parke and Buriel 2006). It could be that the interactions that parents have with early adolescents regarding peer relationships facilitate the development of models of social relationships that early adolescents then use with peers. Future investigations might explore whether early adolescents’ cognitive models of peer relationships statistically mediate the relationship between parental management of peers and social skills.

Finally, in addition to the limitations addressed above, the investigation is limited by the small sample size and the method used for assessing social skills. The results were based on a small sample with some of the effects only significant at a trend level. However, this limitation is offset somewhat by the conservative longitudinal, cross-informant test of the relationships. Clearly, longitudinal investigations are needed that employ larger sample sizes. The adolescents’ social skills were assessed via caregivers’ and adolescents’ reports. Although the cross-informant analyses lend additional credibility to the results, future investigation should include assessments of social skills by an independent observer.

Conclusion

This study documents the importance of caregivers’ management of peer relationships and its association with early adolescents’ social skills over time. The study highlights the potential moderating role that conflict between caregivers and adolescents about peers has on parental management of peer relationships. In particular, conflict about peers in conjunction with higher levels of parental management of peers had an undermining effect on adolescents’ social skills over time. The investigation also provides further evidence for caregivers’ goals of improving peer relationships and caregivers’ beliefs about parental authority as important in determining caregivers’ management of early adolescents’ peer relationships. These findings are likely to be important in practice with early adolescents and their caregivers.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Brown, B. B., & Larson, J. (2009). Peer relationships in adolescence. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (3rd edition ed., pp. 74–103). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Collins, W. A. (1991). Shared views and parent-adolescent relationships. New Directions for Child Development, 51, 103–110.

Furstenberg, F. F., Cook, T. D., Eccles, J., Elder, G. H., & Sameroff, A. (1999). Managing to make it: Urban families and adolescent success. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gresham, F., & Elliott, S. (1990). Social skills rating system. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

Grolnick, W. S., Gurland, S. T., DeCourcey, W., & Jacob, K. (2002). Antecedents and consequences of mothers’ autonomy support. Developmental Psychology, 38, 143–155.

Grolnick, W. S., Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (1991). Inner resources for school achievement: Motivational mediators of children’s perceptions of their parents. Journal of Educational Psychology, 83, 508–517.

Kan, M., & McHale, S. (2007). Clusters and correlates of experiences with parents and peers in early adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 17, 565–586.

Ladd, G. W., & LeSieur, K. D. (1995). Parents and children’s peer relationships. In M. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting, Volume4: Applied and practical parenting (pp. 377–409). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Ladd, G. W., & Pettit, G. S. (2002). Parenting and the development of children’s peer relationships. In M. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting, Volume 5: Practical issues in parenting (pp. 269–309). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Laird, R. D., Pettit, G., Mize, J., Brown, E. G., & Lindsey, E. (1994). Mother-child conversations about peers: Contributions to competence. Family Relations, 43, 425–432.

McDowell, D. J., & Parke, R. D. (2009). Parental correlates of children’s peer relations: An empirical test of a tripartite model. Developmental Psychology, 45, 224–235.

Mize, J., & Pettit, G. (1997). Mothers’ social coaching, mother-child relationship style, and children’s peer competence: Is the medium the message? Child Development, 68, 312–332.

Mounts, N. S. (2000). Parental management of adolescent peer relationships: What are its effects on friend selection? In K. A. Kerns, J. M. Contreras, & A. M. Neal-Barnett (Eds.), Family and peers: Linking two social worlds. Westport, CT: Greenwood/Praeger.

Mounts, N. S. (2001). Young adolescents’ perceptions of parental management of peer relationships. Journal of Early Adolescence, 21, 92–122.

Mounts, N. S. (2004). Adolescents’ perceptions of parental management of peer relationships in an ethnically diverse sample. Journal of Adolescent Research, 19, 446–467.

Mounts, N. S. (2007). Adolescents’ and their mothers’ perceptions of parental management of peer relationships. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 17, 169–178.

Mounts, N. S. (2008). Linkages between parenting and peer relationships: A model for parental management of adolescents’ peer relationships. In M. Kerr, H. Stattin, & R. Engels (Eds.), What can parents do: New insights into the role of parents in adolescent problem behaviour (pp. 163–189). West Sussex, UK: Wiley.

Mounts, N. S., & Kim, H. S. (2009). Parental management of early adolescents’ dating in an ethnically diverse sample. Journal of Adolescent Research, 24, 531–560.

Parke, R. D., & Buriel, R. (2006). Socialization in the family: Ethnic and ecological perspectives. In N. Eisenberg (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development (Vol. 3) (pp. 429–504). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Parke, R. D., Killian, C. M., Dennis, J., Flyr, M. L., McDowell, D. J., Simpkins, S., et al. (2003). Managing the external environment: The parent and child as active agents in the system. In L. Kuczynski (Ed.), Handbooks of dynamics in parent-child relations (pp. 247–270). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Rubin, K. H., Bukowski, W., & Parker, J. (2006). Peer interactions, relationships, and groups. In In N. Eisenberg (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development (Vol. 3) (pp. 571–645). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68–78.

Simpkins, S. D., & Parke, R. D. (2002). Maternal monitoring and rules as correlates of children’s social adjustment. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 48, 360–377.

Smetana, J. (1988). Adolescents’ and parents’ conceptions of parental authority. Child Development, 59, 321–335.

Smetana, J. G., & Asquith, P. (1994). Adolescents’ and parents’ conceptions of parental authority and personal autonomy. Child Development, 65, 1147–1162.

Soenens, B., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2005). Antecedents and outcomes of self-determination in 3 life domains: The role of parents’ and teachers’ autonomy support. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34, 589–604.

Steinberg, L. (1990). Autonomy, conflict, and harmony in the family relationship. In S. S. Feldman & G. R. Elliott (Eds.), At the threshold: The developing adolescent (pp. 255–276). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Tilton-Weaver, L. C., & Galambos, N. (2003). Adolescents’ characteristics and parents’ beliefs as predictors of parents’ peer management behaviors. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 13, 269–300.

Tisak, M., & Tisak, J. (1990). Children’s conceptions of parental authority, friendship, and sibling relations. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 36, 347–367.

Updegraff, K. A., McHale, S. M., Crouter, A. C., & Kupanoff, K. (2001). Parents’ involvement in adolescents’ peer relationships: A comparison of mothers’ and fathers’ roles. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 63, 655–668.

Way, N., Greene, M. L., & Mukherjee, P. P. (2007). Exploring adolescents’ perceptions of parental beliefs and practices related to friendships in diverse ethnic communities. In B. B. Brown & N. S. Mounts (Eds.), Linking parents, family to adolescent peer relations: Ethnic, cultural considerations. New Directions in Child, Adolescent Development, No. 116 (pp. 35–50). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Youniss, J., DeSantis, J., & Henderson, S. (1992). Parents’ approaches to adolescents in alcohol, friendship, and school situations. In I. Sigel, A. V. McGillicuddy-Delisi, & J. J. Goodnow (Eds.), Parental belief systems: The psychological consequences for children (pp. 199–216). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 0131664. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mounts, N.S. Parental Management of Peer Relationships and Early Adolescents’ Social Skills. J Youth Adolescence 40, 416–427 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9547-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9547-0