Abstract

Firms and economic policy makers need an enhanced understanding of universities, in terms of what academics value and how they interact, if they are to enhance collaboration around the generation and transfer of knowledge and technology between universities and industry. The literature increasingly focuses on identifying incentives and barriers within universities, but is largely limited to contexts in Europe and the USA, and favours individual over institutional determinants. The paper contributes by situating university–industry linkages within the total pattern of academic interaction with external actors, in diverse types of institutions. Empirically, it extends the literature to investigate trends in an immature national system of innovation in a late developing economy context, South Africa. The analysis maps the heterogeneity of academic engagement, focusing on firms, through principal component analysis of an original dataset derived from a survey of individual academics. It concludes that the incentives that drive academics and that block university–industry interaction in contexts like South Africa, are strongly related to universities’ differentiated nature as reputationally controlled work organisations, and to the ways in which they balance and prioritise their roles in national development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Firms and economic policy makers need an enhanced understanding of universities, in terms of what they value and how they interact, if they are to enhance collaboration around the generation and transfer of knowledge and technology between universities and industry. The literature increasingly focuses on identifying incentives and barriers related to academics and universities that facilitate or constrain interaction with firms in Europe and the USA. However, conditions vary across countries with different economic development trajectories, and there is a need for more studies in a wider range of contexts. Hence, this paper examines interactive practices of universities in South Africa. In immature national systems of innovation in late developing countries such as South Africa, India or Brazil, there are high degrees of social and income inequality, key institutions and linkages may not exist, and technological achievement may be uneven (Bernardes and Albuquerque 2003; Albuquerque 2003). In such contexts, universities and public research institutes (PRIs) face the dual challenge of linking to global science, and of addressing local economic and social problems (Suzigan and Albuquerque 2011; Albuquerque et al. 2015). These problems relate to local resource conditions, but equally, to the legacy of colonisation, racial and ethnic segregation, and resultant high levels of poverty, inequality and diversity. As economies and systems grow, the demands, and hence the multiple roles universities are expected to play, become more complex. Distinct types of university may combine and balance these multiple roles in diverse ways, shaped by their own historical trajectories. Hence, academics and scientists may be driven to interact with farmers, informal sector producers, marginalised communities and local agencies, and not only formal sector firms (Johnson and Hirt 2010; Kruss et al. 2012a, b). They may prioritise research that aims to solve problems that will improve the quality of life of citizens, for example, partnering with government or development agencies to use nanotechnology to design new low-cost means of water purification. They may be required to address citizen’s health problems across a heterogenous range of diseases, from those typical of highly developed countries, to diseases of poverty. They may of course, prioritise basic research that will enable them to build scientific reputations on the global stage, above research in collaboration with firms at national level.

Situating university–industry linkages within the total pattern of interaction with external actors in diverse types of university across a national system of innovation can thus provide critical insights in late developing economy contexts—the aim of the paper. The empirical analysis identifies and maps patterns of interaction, using an original dataset derived from a survey of individual academics in four historically distinct types of university in South Africa. The value of such research is that it can provide insight into the incentives that are more likely to drive, or the barriers that can block, university–firm interaction, in immature systems of innovation.

The paper begins by considering the emerging literature on incentives and barriers to interaction, drawing on Perkmann et al. (2013) to argue for the need to understand diverse university perspectives in a wider range of contexts than high income countries. It outlines the concepts adopted to distinguish universities and analyse patterns of interaction. Section 3 describes historical contextual features in South Africa, reflecting a highly segmented and hierarchical higher education system with strong reputational competition between four types of university. Section 4 describes the survey methodology, and the principal component analysis method used to analyse the survey data. Section 5 situates the pattern of interaction with firms against the total patterns of interaction, comparing how these reflect what individual academics value in diverse types of university with distinct balances of roles and imperatives. Section 6 argues that barriers and incentives to firm linkages thus differ, shaped by a university’s reputational position and role in this unequal, segmented national system. A range of interventions are required, in contexts where there are complex heterogeneous incentives driving academics. Section 7 draws out policy implications.

2 Literature review

2.1 A growing empirical focus on academic incentives and barriers

A vast literature on university–industry interaction has emerged, most of which has a narrow, highly focused scope on a single issue or specific form of university–industry interaction, investigated from the empirical perspective of firms. For example, a common theme is proximity as a determinant of university–industry linkages (Carboni 2013; Lindelof and Lofsten 2004; De Fuentes and Dutrenit 2014; Hewitt-Dundas 2013). Research conducted from the university perspective has tended to focus on determinants of entrepreneurial forms of interaction, linked to commercialisation of university knowledge and revenue generating activities, such as the optimal conditions for promoting academic spin-off firms (Niosi 2006; Pries and Guild 2007; Mustar et al. 2006); how research centres promote commercially relevant knowledge production (Ponomariov 2013); or the effective use of technology transfer offices (Muscio 2010). There is considerable effort debating the relationship between entrepreneurial and academic roles, rewards and performance (Van Looy et al. 2004; Tjissen 2004; Tanga et al. 2003; Gulbrandsen and Smeby 2005).

However, the research literature increasingly recognises that policy makers and firms need to understand the conditions inside universities and the incentives that drive academics to collaborate. Mowery and Sampat (2005) emphasise that it is difficult to conceptualise universities in the same way as economic institutions, because of their distinct forms of governance and because of the very real tension among the different roles universities are expected to play within a knowledge-based economy. A set of studies focus attention on the barriers to interaction that arise from the differences and similarities between the values, motivations and orientations of universities and firms (Audretsch and Lehmann 2005; Bruneel et al. 2010; Muscio and Pozzali 2013).

Significantly for our purposes, there is growing recognition that entrepreneurial forms of action are not necessarily those most prized by universities, and that a broader understanding of forms of ‘academic engagement’ in response to economic and social challenges, is required. Ramos-Vielba and Fernandez-Esquinas (2011) for example, demonstrate the wide variety of channels of knowledge transfer in Andalusian universities, proposing that policy makers should move beyond a narrow focus on patents and spin-offs. Abreu and Grinevich (2013) broaden the scope of ‘academic entrepreneurship’ to include any activity that occurs beyond traditional academic roles of teaching and research, and that lead to financial reward for the academic or institution. Cesaroni and Piccaluga (2015) extend this further, questioning whether and how broader models of social engagement are replacing narrow knowledge transfer models focused on commercialisation in Italian universities. Based on a study of the specific constraints to diverse forms of interaction experienced in mid-range universities, rather than the world class universities that are the focus of much research, Wright et al. (2008) call for a more differentiated mandate for university diffusion of knowledge and technology.

A second strand of research significant to our task focuses on individual academic incentives and diverse university systems (Schartinger et al. 2001; Gurnasekara 2006; Wright 2014; Shah and Pahnke 2014; Bozeman et al. 2013; Aschhoff and Grimpe 2014). This research investigates the role, organisation and attitudes of different types of university and different types of unit (faculty, department or research centre) in driving interaction with firms (Kenney and Goe 2004; Secondo and Ugo 2014; Martinelli et al. 2007). DÉste and Patel (2007)Footnote 1 for example, conclude that the nature of individual researchers, rather than organisational units or universities, influence the forms and frequency of interaction (see also DÉste and Perkmann 2011). However, they acknowledge that the influence of individual factors is likely to be mediated by the specific nature of a university and department. In this light, Rizzo (2015) showed that young Italian scientists are more likely to establish academic spin-offs as a mechanism for advancement, in the context of an academic system with few opportunities and many bottlenecks. The complexity of the intersection between individual factors and organisational conditions is thus increasingly acknowledged: Goel et al. (2015) examine the entrepreneurship propensity of individual academics, highlighting gender differences connected with university seniority and leadership; and Tartari and Salter (2015) similarly find that female academics engage with industry on a much smaller scale than males, but that university-level formal commitment and support lessens the differences.

In this regard, Perkmann et al. (2013) conduct a systematic review of the literature that is useful to situate our research. They question whether and how ‘academic engagement’ is distinct from commercialisation, in terms of its drivers and benefits. ‘Academic engagement’ is defined as any form of ‘knowledge-related collaboration by academic researchers with non-academic organisations’; but commercialisation activities refer specifically to academic entrepreneurship and the generation of intellectual property through patenting and licensing (Perkmann et al. 2013). They too focus on the critical role of individual academics, arguing that universities are “‘professional bureaucracies’ … that rely on the independent initiative of autonomous, highly skilled professionals to reach their organisational goals” (Perkmann et al. 2013: 426). Their review summarises a predominant interpretation in the literature: that although both forms tend to be driven by individual imperatives, organisation-level support is more significant for commercialisation activities, while academic engagement is more typically driven by individuals and their units.

The paper contributes to this emerging literature, by engaging with three elements of the research agenda Perkmann et al. (2013) propose. The first relates to the rationale for the paper: the systematic review highlights the significance of research to inform firms’ understanding of what motivates academics to engage, particularly the importance of academic benefits. The second relates to the empirical focus and methodology of the paper: the review emphasises the need to extend empirical coverage beyond the US and Europe, to investigate countries at different stages of development, with different innovation and higher education systems, using survey tools at the micro-level. The third element relates to the main contribution of the paper: the claim that much of the literature underestimates the diversity of universities and higher education institutional systems in different country contexts, leading to the proposal that it is important to investigate “diverse patterns of university–society interactions in various settings’’ (Perkmann et al. 2013: 450). That is, one question that has not been well considered in the literature is whether and how the frequency and forms of interaction differ for individual academics in universities of distinct types across a national higher education system. This is a particularly pertinent question in the context of immature systems of innovation, where universities are expected to balance complex multiple roles that may be the preserve of other actors or organisations in more mature systems, and where the differences between universities may be shaped by complex forms of social inequality. Therefore, the paper will analyse the heterogeneity of academic engagement in different types of university in South Africa, to inform debate on the incentives and barriers to university–firm interaction from the perspective of universities.

2.2 Country level research across national systems of innovation

Until recently, there were not many systematic studies of the scale, nature and conditions for university–industry interaction across immature national systems of innovation in middle and low income country contexts. A small body of research was conducted in 12 countries in Africa, Latin America and Asia (Albuquerque et al. 2015), exploring how and why relationships between universities and firms differ across countries and regions at different stages of development. The South African research on which the paper draws was designed within the ambit of this global comparative research. It extended the seminal work of Cohen, Nelson and Walsh (2002) in the US, which surveyed patterns of interaction, focusing on the types of relationships, channels of interaction, benefits and constraints from the perspective of firms, by adding an additional element—to map patterns of interaction from the perspective of universities and PRIs.

In the South African context, since the advent of a democratic government in 1994, national science and technology policy incentivised interaction with firms through a variety of instruments, such as funding programmes for collaborative research, the establishment of university technology transfer offices, a legal framework governing intellectual property rights from publicly funded research, and funding for regional innovation hubs and clusters in priority sectors. At the same time, national higher education policy encouraged universities to promote community engagement and social responsiveness, evident in new forms of engagement through teaching, research and outreach with marginalised communities, particularly those who are poor, women, black, in rural areas or informal settlements (Kruss 2012; CHE 2010a). These contextual conditions informed the addition of new items to the survey instrument: to determine the presence of interaction in general; to reflect teaching and outreach roles in addition to research and innovation; and with the full range of partners alongside firms: government, informal sector firms, civil society or community actors, and including marginalised communities (see Kruss et al. 2012a, b).

2.3 Drivers, forms and benefits of interaction

Many studies investigate the benefits of entrepreneurialism and academic engagement for universities (Prigge 2005; Harman 2001; Kruss 2006). The framework for research in immature systems of innovation distinguishes intersecting drivers of interaction for firms and universities that shape specific forms of interaction, each associated with benefits and risks for firm and university actors (Kruss 2005; Arza 2010; Dutrenit and Arza 2010). Key analytical concepts are elaborated in this section.

University drivers of interaction with firms are interpreted in terms of intellectual and/or financial imperatives, to take the distinctive nature of universities into account. Similar to the idea of professional bureaucracies proposed by Perkmann et al. (2013), we adopt Whitley’s (2000, 2003) definition of universities as ‘reputationally controlled work organisations’. As organisations, they structure the production of knowledge around the competitive pursuit of individual scientific reputations, as judged and measured by publication of codified knowledge, most typically in peer-reviewed journals. Individual academics are driven by their ‘intellectual imperatives’ to pursue forms of interaction that will enhance scientific reputations, but this may be in combination, balance or tension with ‘financial imperatives’ to raise third-stream and research income.

Firm strategies are either passive or proactive, driven more strongly by firm’s financial or intellectual imperatives. The interaction between the imperatives of firms and universities shapes distinct types of relationship with different benefits for universities, firms and the national system of innovation. Forms of interaction were classified into four broad types (Arza 2010). Interaction motivated by the financial strategies of universities and passive strategies of firms is more likely to take ‘service’ forms, with knowledge flows mainly from the university to the firm, such as consultancy, contracts or testing. Such interaction is primarily to the benefit of the firm, with a risk to the knowledge project of the university when restrictions are placed on proprietary knowledge. In contrast, interactions motivated by the intellectual strategies of the university and proactive strategies of firms are more likely to take ‘bi-directional’ forms, where knowledge flows are two-way and there is a high potential for joint learning, such as joint research and development (R&D) projects or networks, to mutual benefit. ‘Traditional’ forms of interaction are driven by the intellectual imperatives of the university and the passive strategies of firms, with indirect knowledge flows to firms, but defined strongly by academic functions, such as hiring graduates, conferences and publications, or financial flows from firms to support academic functions (bursaries, endowments, donations). These are to the direct benefit of reputational concerns, but may not impact directly on firm technological capability building. Finally, ‘commercialisation’ forms of interaction are driven by the financial/entrepreneurial strategies of universities and the proactive strategies of firms, taking the form of spin-off companies or incubators that require direct personal interaction at critical stages. These tend to be of financial benefit to the university, but may pose risks to the core roles of teaching and research.

2.4 Universities as reputationally controlled work organisations in competitive higher education systems

Public university systems in different countries can be distinguished along two main dimensions: the intensity of competition around scientific reputations in the local, national and international arenas; and the level of intellectual pluralism and flexibility encouraged in terms of changing research goals across a university or the system (Whitley 2000, 2003). In a highly differentiated and segmented higher education system with strong reputational competition between research universities and applied research or technology transfer institutions, hierarchies of institutions typically limit and restrict what is possible in setting new research agendas, novelty is restricted, and flows of knowledge are limited. As Whitley (2003) claims, in such cases, it is extremely difficult for universities on the margins to improve their reputational standing, as they cannot attract leading scientists nor win research resources competitively.

Academics in universities with stronger or weaker reputations are thus likely to experience the intellectual and financial imperatives driving interaction in different ways. The strength of the individual pursuit of reputations, and the nature of differentiation and segmentation within a national higher education system, are significant for understanding the frequency and forms of interaction in general, and with firms specifically, across a higher education system. What is the nature of reputational standing and competition between different types of university in South Africa?

3 Methodology

It is thus significant to understand the intellectual and financial imperatives driving a university, reflected in its distinct pattern of forms of interaction. We use these conceptual distinctions to analyse the frequency and forms of academic engagement in different types of university, in terms of the nature of all partners, and the types of relationship and benefits, with all partners and firms specifically.

3.1 Study design

The research design was a mixed-methods comparative case study approach. Interviews with institutional university leaders and managers, national datasets and analysis of strategic documents were used to analyse each university’s history, mandate and institutional culture shaping its position in the national system. This qualitative data was used to analyse universities’ reputational standing. A survey of a large, generalisable sample of academics based at five universities spread across South Africa was conducted in 2010. The qualitative data was used to interpret data trends.

The official higher education typology was the basis for selection of cases: research universities (ResU), comprehensive universities (CompU) and universities of technology (UoT) (CHE 2004: 49). A fourth type was added to include a set of rurally located, under-resourced universities attempting to develop a common strategy to reposition themselves (RuralU). Two research universities were included to reflect their relative influence in the system, as well as historical differences that shaped their roles (ResU1 and ResU2).

The aim of the survey instrument was to measure the ways in which academics ‘extend their scholarship to the benefit of external partners’, in terms of the nature of partners (29 items), the types of relationships (18 items), the outputs (11 items) and outcomes (19 items), and perceived constraints (13 items) (Albuquerque et al. 2015). The items within each dimension were constructed in the form of a Likert scale. Respondents were asked to indicate the frequency of their practice for each item, by providing a number between 1 (not at all) and 4 (on a wide scale). Academics could indicate that they had not engaged with external partners at all, and a set of items probed their reasons.

3.2 The survey of academics

Contact details of a total population of 3477 academics were acquired from the universities, and a total of 2159 academics responded to the survey, yielding a sample with an overall valid response rate of 62% (Table 1).

The population and sample distributions displayed similar gender, racial and academic rank trends within each university, but with distinct differences between types. ResU1/2 and CompU were more than three quarters white (and hence, historically privileged), while just less than half (47%) of the samples in UoT and almost a third (32%) of those in RuralU was white. All had a gender distribution of 60% male and 40% female.

3.3 Data analysis

The aim was to map patterns of academic practices across each university, and comparing across the system. Data analysis proceeded first by calculating a Weighted Average Index (WAI) to rank each item in a dimension in terms of both the scale and the frequency with which it was reported, for each university and the total population. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of four dimensions—partners, type of relationship, outputs and outcomes—was then conducted in order to reduce complexity, and reveal patterns of interaction. The PCA extraction method made use of Varimax rotation method with Kaiser Normalization. Values for the latent variables inferred by the components produced by the PCA were populated with means of each set of variables within a component. For the population of all universities this procedure produced six types of partners; four types of relationships; two types of outputs; three types of outcomes and benefits; and two types of reasons for not engaging at all with external partners. Table 2 summarizes statistics on the variables derived from PCA. It is evident from the third column that the internal consistency and reliability (Cronbach’s Alpha) of the components are acceptable.

4 Types of university in a strongly segmented and hierarchical higher education system

As in other contexts (Suzigan and Albuquerque 2011; Wright et al. 2008; Boardman and Ponomariov 2009), public universities in South Africa were established in distinct periods to meet specific economic and political purposes and these origins shape their ‘path-dependent’ nature (Krücken 2003). A strongly politicized and racialised society negatively influenced the degree of flexibility and pluralism possible. Highly polarized intellectual traditions were promoted in different types of university that served specific racial and ethnic groups of students, defined by legislation and unequally resourced. The current higher education system remains strongly differentiated, segmented and hierarchical, in contrast to many others in developed economy contexts. Table 3 summarises the reputational standing of the five universities in the study, reflecting their relative emphasis on teaching (enrolment indicator) and research (publication indicator).

In a segmented differentiated national system, RuralU falls near the bottom, with severe constraints on its ability to build reputation. Located in an impoverished rural region, RuralU is typical of ethnically defined universities established as part of the apartheid political strategy, facing extensive reputational challenges as primarily teaching universities, poorly funded, poorly managed and financially under-resourced over decades, with weak research cultures. These universities display very low degrees of reputational competition, oriented to local audiences and local goals. However, with a long identity of political resistance, their reputations are not solely determined by academic disciplinary peers, but also by social and political commitment to transformation and responsiveness (Nkomo and Swartz 2006). RuralU relies primarily on government subsidy and struggles with high levels of student debt. Financial imperatives relate to accessing funds for basic operations and organisational survival, while intellectual imperatives relate to developing research capabilities, or addressing local developmental problems.

In contrast, there is intense reputational competition between the research universities at the national level. They are strongly segmented from the other universities, which aspire to their higher levels of achievement and reputations for scientific excellence achieved globally, in niche fields (Cloete et al. 2006; Pouris 2007; CHE 2015). The English speaking universities (ResU2) with a strong commitment to the principles of academic autonomy, tended to develop stronger flexibility and pluralism in research agendas than the Afrikaans speaking universities (ResU1), which were more isolated and strongly tied to an authoritarian, ethnic and cultural nationalist tradition associated with the apartheid state. Over many decades, ResU2 built a global research reputation in key disciplinary fields that is integral to its vision, strategy and functioning, with many long serving, highly qualified and well published academics. This is balanced with a liberal institutional ethos, commitment to a social justice agenda and a strong defense of academic freedom. For a period after 1994, ResU1 adopted a deliberate entrepreneurial strategy, reflected through the promotion of innovation, income-generating research and industry partnerships, supported by a range of entrepreneurial structures (Kruss 2005). At the time of research, new leadership was shifting to a strategy of academic excellence and global reputation building. Both universities are well resourced, with private sources of income exceeding government subsidy, and student fees growing.

ResU2 is at the top of the hierarchy in terms of its reputational status and financial stability, so that intellectual imperatives could drive interaction more strongly, and financial imperatives could be experienced as the need to supplement and add value to core activities. ResU1 follows in terms of reputational standing, with financial imperatives driven by entrepreneurial motivations to supplement university income, and intellectual imperatives to enhance reputation to match or exceed the top national universities, and build global reputation.

The comprehensive universities were established through a government-driven process of higher education restructuring from 2004 (DoE 2002), to provide a stronger teaching orientation alongside locally relevant research and technology development. The challenges of a complex institutional merger; and conceptualizing a new identity and reputation, operating across multiple campuses, are immense for CompU. However, the merged universities brought long established traditions and practices of industry and community engagement, and the balance of private funding increased over a short period, suggesting an aspiration and growing capacity, to grow reputation.

Historically, the role of technikons, the predecessors to universities of technology, was to teach applied technology fields, a traditional ‘binary divide’ that shapes their trajectory into the present. UoTs face multiple challenges of redefining their identity and roles, and establishing scientific reputations in a hierarchical system dominated by research universities (Winberg 2005; Thatiah and Schauffer 2007; CHE 2010b). Research culture is weak, and academic capacity-building to grow the research base is a major strategic focus (Dyason et al. 2010). The intensity of reputational competition is relatively low, although some, like UoT, are rapidly developing national and local reputations in selected technology fields. Further challenges arise from a strong reliance on government subsidy and tuition fees, drawing from an impoverished student base. Intellectual imperatives at CompU and UoT were likely to be linked to establishing scientific reputations in niche fields, while financial imperatives could be related to either basic operations or value-addition for research and innovation.

Therefore, in comparison with the US or Europe, the South African system of innovation is characterised by a stark degree of reputational competition and inequality between different types of university. We move in the next section to consider the ways in which this shapes how their academics are motivated to interact with external partners, and firms specifically.

5 Patterns of interaction in the five universities

The balance of roles, the financial and intellectual imperatives driving academics to interact with firms, and the forms of interaction and benefits they pursue, are thus likely to differ significantly between universities in South Africa. This section analyses and compares the frequency and forms of interaction, in terms of the nature of partners, the types of relationship and the outcomes and benefits, to determine whether and how they differ.

5.1 Scale and frequency of interaction

Descriptive analysis of the frequency of interaction and the number of partners as reported in Table 4 suggests that the high 81% engagement reflects a generalized awareness of the need to be responsive to social and economic problems, rather than strong or frequent interactive activity. A range from 43% of academics at UoT to 59% at CompU did not engage at all, or did so on an isolated scale only. Between a fifth and a third of academics engaged on a moderate to wide scale, but with a single partner, suggesting dyadic forms of interaction typical of service and traditional forms of interaction. A smaller group, ranging between 14% and 37% of academics, engaged actively in networks, that is, on a moderate to wide scale with more than two partners.

There is a marked difference in the relative size of these groups in each university, and this is statistically significant. ResU2 had the lowest reports of no engagement, but equally, lower proportions of frequent and networked interaction. In contrast, a quarter of academics at UoT were clear that they did not interact at all, while almost 60% were interacting frequently, and almost 40% of these with multiple partners. Interaction on an isolated scale only was most likely at the research, rural and comprehensive universities, in comparison with the UoT; and the two research universities were more likely to interact frequently with only a single partner.

These trends indicate a relatively low scale of active academic engagement in aggregate, across the four types, but there are core groups of frequently and actively engaged academics in each type of university.

5.2 Barriers relate to academic identity

The main reason 19% of academics did not interact at all was related to academic identity (engagement is not central to my academic role; or not appropriate to my academic field), but also, lack of institutional support: lack of clear structures, policy, recognition as scholarship, administration systems, different priorities of universities and partners, financial resources or conceptual clarity. Figure 1 reflects the relative importance of these two components at each university. ResU2, with the highest reputational standing, had the largest difference between the two sets of reasons, suggesting that academics do not engage because it is not appropriate to their academic identity, while institutional support is less important. In contrast, at UoT, aspiring to establish scientific reputation, and with the largest group of academics who do not engage (26%), academic identity was less significant as a barrier, and almost as important as institutional support.

Academics in universities with stronger reputations evidently viewed academic identity as a significant barrier to interaction.

5.3 Academic partners are most common

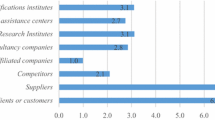

We argue that in order to understand what universities value, interaction with firms needs to be understood relative to the total pattern of academic engagement. Figure 2 compares the frequency of interaction on any scale with six types of partner identified through PCA, per university.

Academic partners were more frequently engaged (international universities, funding agencies, science councils and SA universities), especially at the two research universities, followed by community partners (individuals and households, and a specific local community). Academic partners were as significant as community partners at the UoT, RuralU and CompU, hinting at their orientation to address primarily local-level problems, rather than global reputations. Government (provincial, local and national departments), welfare (NGOs, welfare agencies, community organisations, development agencies and social movements), firm (large SA, multi-national companies, small, medium and micro enterprises, and sectoral associations) and civil society (trade unions, political organisations, and civic associations) partners were then ranked closely to each other, in different ways in each type of university. Chi square tests on interaction revealed that the differences were statistically significant: for firm partners, χ 2(12, N = 1739) = 42.51, p = .000; academic partners, χ 2(12, N = 1739) = 72.10, p = .000); community partners, χ 2(12, N = 1743) = 54.19, p = .000); and civil society partners, χ 2(12, N = 1742) = 43.15, p = .000. Associations with welfare partners, χ 2(12, N = 1742) = 18.01, p = .12) and government partners, χ 2(12, N = 1744) = 18.89, p = .091) were not statistically significant.

On average, firm partners were only the fourth or fifth most frequent, for all types of university, an indicator of relatively lower academic value.

5.4 Universities differ in their interaction with firm partners

Such aggregation however, masks significant pockets of activity and differences. UoT had the highest frequency of firm partners, followed by ResU1 (reflecting its institutional entrepreneurial strategy) and CompU. Engaged academics at ResU2 (highest reputation) and RuralU (lowest reputation) did not frequently interact with firm partners. Qualitative data suggests that ResU2 does not value firm linkages—indeed, some academics viewed UILs as a threat to the academic project; but RuralU in contrast, does not have the research capacity to attract firm partners on a large scale.

Table 5 drills down further to focus on those who do interact with firms on a moderate to wide scale. It reflects the types of firms with which this group of academics interact, relative to the total sample of academics, and to the set of engaged academics in each university (the latter is reflected in Fig. 3 for ease of comparison). Interaction was most frequent with large national firms (LNF), particularly at UoT and ResU1, where a larger proportion of the engaged academics interacted with firms [statistically significant χ 2(12, N = 1737) = 41.98, p = .000]. Where a small group of academics at ResU2 interacted frequently with firms, it was more likely to be LNFs. Of note, ResU1, CompU (which incorporated a UoT with a strong technical reputation) and even UoT were more likely to interact with multinational companies (MNCs) than ResU2, likely relying on global reputations built in niche SET fields. (Statistically significant χ 2(12, N = 1737) = 28.67, p = .004). UoT and CompU were more likely to interact with small, medium and micro-enterprises (SMMEs), supported and incentivised by a national funding programme to build regional technology platforms within these institutions. [statistically significant χ 2(12, N = 1738) = 86.45, p = .000]. Academics at RuralU were least likely to interact with firms, but more likely with SMMEs than other types of firm, which reflects their strong local orientation, and suggests that the isolated location and weak reputation were barriers to interaction with LNFs and MNCs.

The frequency of individual academics’ interaction with national and global firms was thus aligned with a university’s strategic orientation and reputational standing in the hierarchical and unequal national system.

5.5 Teaching-related types of relationships predominate

Are these interactions likely to be traditional, service, commercialisation or network types of relationship? Education of socially responsive students,Footnote 2 a tacit and indirect, but the most frequently reported type of relationship, loaded onto a factor that was named engaged teaching and outreach to encompass the range of teaching, professional development, research and service activities included: service learning, student voluntary outreach, community-based research (closely connected with student learning), clinical services, and work integrated learning. This was in distinction to alternative teaching, which included continuing education, customized training (two typical types of relationship with firms), collaborative curriculum design and alternative modes of delivery. These can be classified as traditional and service forms of interaction. Engaged research included both applied and strategic research, in dyadic and networked forms: collaborative R&D, consultancy, contracts, participatory research, and policy research. Finally, the component consisting of design of new technologies, technology transfer, design of new interventions and joint commercialization was named technology transfer, and can be classified as commercialisation forms of interaction.

These factors are not totally aligned with the four ideal types of interaction described above. Collaborative R&D and consultancy are classified as bi-directional and service forms of interaction respectively (Arza 2010), but here, both loaded to engaged research. The analysis thus identifies underlying associations when all kinds of external partners, and not only firms, are taken into account. It suggests that teaching-related rather than research-related types of relationship predominate, across the board.

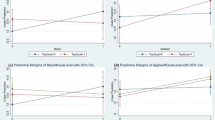

However, as with the pattern of partners, the observed differences between the universities are all statistically significant (Fig. 4: engaged research, χ 2(12, N = 1739) = 28.30, p = .005; engaged teaching and outreach, χ 2(12, N = 1739) = 100.63, p = .000; alternative teaching, χ 2(12, N = 1738) = 99.91, p = .000; and technology transfer, χ 2(12, N = 1739) = 45.80, p = .000). Significantly, the commercialization and entrepreneurial activities captured by the component of technology transfer was least frequent at all types of university. It was more likely at UoT, given its historical mandate, and less likely at ResU2, given its strategic mandate and reputation. Alternative teaching was the most frequent type of relationship at all universities, particularly at UoT and CompU, those most frequently interacting with firms, suggesting that training and short courses are important channels of interaction. The difference between the research universities, in terms of reputational competition, was evident in that engaged research was more frequent at ResU2 than at ResU1.

5.6 Types of relationship with firms

Academic engagement is thus more prevalent than entrepreneurial types of relationship, across the system. To explore existing entrepreneurial-related activity in greater detail, we calculated the percentage of academics that reported each type of relationship on a moderate to wide scale, in their frequent interaction with firms (Figs. 5, 6, 7). The results revealed some unexpected trends that point to barriers and incentives.

For this most entrepreneurially engaged group of academics, technology transfer types of relationship were least likely at CompU. This is a surprising trend and gap, given the relative importance of firm partners at this university, with its institutional emphasis on technology transfer and regional economic development. Technology transfer types of relationship were most frequent for the group of entrepreneurially engaged academics at UoT, in line with their core roles, and aspiration to build science, engineering and technology reputations. There is another exception and surprising trend—the very small group at RuralU was more likely to interact through technology transfer types of relationship with MNCs (48%) than the academics at any of the other universities. This highlights an emergent niche of activity, although these MNCs may be partners in rural development and aid networks that transfer technology to small-scale farmers. The small entrepreneurially engaged group at ResU2 was also more likely to interact through technology transfer with MNCs than with LNFs or SMMEs, but this trend is more likely to highlight significant niche SET expertise, based on academics’ global reputations. Such trends highlight a potential gap in interaction with large firms to promote capability building and competitiveness nationally.

Analysis of the engaged research type of relationship confirms that ResU1 academics interacted more strongly with firms than ResU2, particularly with MNCs, despite the fact that academics at ResU2 in general were more likely to interact through engaged research. Engaged research was equally as frequent for UoT as technology transfer, for all types of firms. Such trends likewise identify areas of university–industry linkages that offer potential spaces for intervention, to deepen and grow in future.

This type of analysis contributes by pointing to areas where further qualitative in-depth investigation is required, to explain the gaps, blockages or emergent trends highlighted in a university. Such analysis of interactive patterns informs our understanding of academic incentives and barriers, and thus, can serve to identify appropriate spaces for intervention by firms, universities or policymakers, suited to each institutional context.

5.7 Academic outputs and outcomes are the main benefit

A final set of analyses was conducted to explore how the main benefits of interaction reflect the imperatives driving academics. A distinction was drawn between outputs—results of interaction that are measurable—and outcomes—impact that is less easily measurable in the short term. Our framework and instrument go beyond the traditional measures of patents or academic publications, to include a wide range of tacit and codified outputs and outcomes. The analysis revealed that the universities valued these in different ways,

Traditional academic outputs (M = 2.61, SD = 0.70) was the most important, with the highest frequency across all types of university: academic publications, dissertations, academic collaboration, reports, policy documents, popular publications, scientific discoveries and graduates with relevant skills and values. The second factor, economic and social outputs (M = 1.56, SD = 0.57), included new or improved products and processes, community infrastructure and facilities, spin-off companies and cultural artefacts. Analysis of variance revealed that significant differences, with academics at the two research universities reporting traditional academic outputs to a larger extent than the other three, in line with our argument that they are more strongly driven by reputational competition and intellectual imperatives.

The main type of outcomes reinforced this pattern.

-

1.

Community and social development (M = 2.13, SD = 0.70) benefits included: community empowerment, community-based campaigns, public awareness and advocacy, improved quality of life for individuals and communities, incorporation of indigenous knowledge, regional development, intervention plans and guidelines and policy interventions.

-

2.

Academic benefits (M = 2.92, SD = 0.67), consisted of: theoretical and methodological development in an academic field, academic and institutional reputation, relevant research focus and new research projects, participatory curriculum development, new academic programmes and materials, training and skills development and improved teaching and learning.

-

3.

Productivity and employment generation (M = 1.78, SD = 0.76) included entrepreneurial benefits: firm productivity and competitiveness, firm employment generation, novel uses of technology and community employment generation.

Academic benefits were reported most frequently at all universities, with high means, but of note, universities with lower reputational value, UoT (M = 3.03, SD = 0.67), RuralU (M = 2.92, SD = 0.72), and ResU1 (M = 2.91, SD = 0.66) reported the highest frequency of academic outcomes from interaction with all partners. CompU (M = 2.88, SD = 0.66) and ResU2 (M = 2.86, SD = 0.68) reported the lowest frequencies, suggesting that in general, the academic benefits from interaction were less highly valued at these universities. RuralU reported the highest frequency for community and social development related benefits, while academics at UoT reported the highest productivity and employment generation benefits, patterns that are aligned with their mandates and positions in the national system. In all types of university, the set of academics that interacted frequently with firms also most frequently reported academic benefits from their interaction with all types of firm (Table 6). However, ResU2 and ResU1 valued academic outcomes from firm interaction more strongly, in contrast to the trend at RuralU, CompU and UoT.

In the South African context, a high value is thus placed on academic benefits that can build scientific reputations (Whitley 2003) or enable these professional bureaucracies to attain their organisational goals (Perkmann et al. 2013).

6 Discussion: the value of analyzing the frequency and forms of interaction in diverse types of university across a national system

6.1 Intellectual imperatives a key driver

The research extends empirical coverage beyond advanced economies in Europe and the US (Wright 2014; Perkmann et al. 2013; Gurnasekara 2006), to the South African context, characterised by a hierarchical, reputationally segmented higher education system that restricts knowledge flows and mobility. Most striking was academics’ strong awareness of the importance of interaction for national development; but the scale of active and networked interaction was relatively low, particularly with firms.

In aggregate, the patterns reflect that traditional forms of interaction tend to prevail. Academic partners, teaching oriented types of relationship and academic benefits were most frequently reported. This suggests that in the pursuit of global and national reputations, intellectual imperatives drive individual academics strongly, and that academic benefits are an important motivation for interaction with all types of firms, across all types of university. The trend echoes Perkmann et al. (2013)’s conclusion that in Europe and the US, there is a positive correlation between academic engagement and scientific productivity (see also Rivera-Huerta et al. 2011, on the Mexican case). In the South African context, however, the stronger the reputation and scientific productivity of a university, the less its academics are motivated by financial imperatives, and the less they value productivity and employment generation benefits.

6.2 Frequency and forms of interaction with firms differ between distinct types of university

The main contribution of the research is thus to demonstrate that in the context of unequal, highly segmented systems, the frequency and forms of interaction with firms differ for academics in universities of distinct types. Econometric research in advanced economies tends to favour individual over university determinants of interaction (Perkmann et al. 2013). Bekkers and Freitas (2008) for example, found in the Dutch context that rather than industrial sector or university differences, the frequency and importance of channels of interaction were more strongly influenced by factors related to knowledge fields, individual and institutional characteristics.Footnote 3 Our research shows that in the context of an immature system of innovation, university differences, in terms of reputational competition and balance of financial and intellectual imperatives, are significant in shaping the frequency of diverse forms of interaction with firms and other actors.

The combination of analysis of qualitative institutional data and patterns of micro-level survey data highlights the complexity of the intersection between individual and institutional determinants, in contexts where universities have distinctive historical trajectories. Individual academics at ResU2, with the strongest global and national reputation, and strong liberal defense of academic freedom, were less likely to interact with firms, to actively pursue entrepreneurial technology transfer oriented types of relationship, and least likely to value the benefits of interaction. Academic reputation was a barrier to pursue interaction. In contrast, academics at a university of a similar type (ResU1) displayed a very different pattern and balance of financial and intellectual imperatives: they were most likely to interact with firms through service and commercialisation forms of interaction, and more likely to value academic benefits. Here, reputational concerns were less of a barrier, mediated by institutional entrepreneurial imperatives, and influenced by a strong authoritarian tradition and less flexibility and pluralism in setting research agendas.

Academics at UoT, which historically prioritised entrepreneurial and technology development roles, but was challenged to build reputation in niche technology areas, were most likely to engage with large national firms and SMMEs through technology transfer types of relationship and to report productivity benefits, which is consistent with trends in the literature (Perkman and Walsh 2008). CompU emphasised professional and occupational education and training, and technological research oriented to address local problems, and interaction with firms was primarily driven by intellectual imperatives, taking traditional, teaching-oriented forms, with a low frequency of commercialisation forms. Here, the institution grappled with a particular barrier—the challenge of establishing reputation as a new institutional type. The pattern at RuralU points to even greater complexity. Academics were most likely to pursue engaged teaching types of relationship with firms, and technology transfer relationships with MNCs, but with community and social development benefits most frequent, rather than firm productivity or academic benefits. Here, weak reputational status and research capabilities were barriers to interaction, but the institutional priorities of a university oriented to development of the marginalised and vulnerable communities in its immediate environment, also shaped individuals’ patterns of interaction in specific ways.

6.3 Situating firm interaction within the total pattern of interactive activity

The empirical research thus highlights a dimension that stands out more starkly in a context with high degrees of social and income inequality—that community development imperatives may drive academics and institutions, in ways that directly compete with industry demand. Across the board, community partners, engaged teaching and community and social development benefits were reported more widely than industry oriented patterns (Kruss 2012). Academic engagement oriented to community and social development appears more significant than entrepreneurial forms of interaction with firms, in most types of South African university (see Cesaroni and Piccaluga 2015 for comparison with the Italian case). The promotion of university–industry interaction in a late developing context like South Africa should take as its starting point, and be located within an appreciation of, such a holistic and comprehensive analysis of the total pattern of academics’ interactive activity, across the national system of innovation. In short, we aimed to show that academics’ pattern of interaction provides clues as to what they value most, which is shaped by institutional (and national) goals and capabilities—and what they value most influences whether and how they interact with firms.

7 Conclusion: heterogenous and complex incentives and barriers to interaction with firms

Such insights are important for countries with similar development challenges, like Brazil, India or Mexico, to inform firms’ and policy makers’ understanding of the complexity of academics’ motivations to engage, in a nuanced manner, across a differentiated higher education system.

We conclude that the incentives that drive South African academics and that block university–industry interaction are strongly related to their historically differentiated nature as reputationally controlled work organisations, grappling to balance and prioritise multiple roles in national development, and at the same time, contribute at the global science and technology frontier. However, we also show that, through disaggregation and investigation of heterogeneity and diversity, analysis of micro-level data can reveal important evidence of emergent activity and ‘spots of interaction’ (Rapini et al. 2009) with national and global firms. These spots of interaction represent partial connections between science and technology systems in immature systems of innovation, which can be nurtured to contribute to technological capability building and national development (Albuquerque et al. 2015; Bodas Freitas et al. 2013). Perkman and Welsh (2008) for example, propose a dual incentive strategy, whereby certain forms of consultancy could be promoted in less research intensive universities, while research universities continue with basic research productivity. As DÉste and Patel (2007) point out, if policy makers understand the wider range of forms of academic engagement in addition to the main entrepreneurial forms, initiatives can be created to build university and academic capabilities to link to knowledge users in firms more effectively, and on a wider scale.

What then are the policy implications, for addressing incentives and barriers to interaction with firms in the South African higher education system?

First, policy interventions are required to break down segmentation and hierarchies, and enhance knowledge flows, flexibility and mobility across the higher education system, and within the national system of innovation (Wright et al. 2008). Mechanisms to promote the mobility of academics, the circulation of ideas and theories, and the academic value of intellectual collaboration, can address major barriers to the promotion of all forms of interaction.

Second, firms and policy makers need to foreground ways to engage that address intellectual imperatives, lead to academic benefits and promote the reputational nature of universities, at the same time as addressing firms’ knowledge and technology needs. As Perkmann et al. (2013:442) point out, this too is a widespread problem in US and European contexts: “Particularly when collaborating with the best academic researchers, firms need to take into account that these academics will under most circumstances only work with them if there is also some academic benefit to be derived” (see also Muscio and Pozzali 2013; Bruneel et al. 2010; Bozeman et al. 2013). Thus, to promote industry interaction, particularly at research universities, will require a strategy that can convince academics of the potential knowledge value and academic benefits, alongside financial incentives. Support to grow networked forms of interaction, shaped by both firms and universities intellectual imperatives, is one potential mechanism (Arza 2010; Kruss 2005).

Third, differentiated strategies and a range of interventions are required where there are complex heterogenous incentives driving individual academics. Where there are existing or potential ‘spots of interaction’ with firms, policy interventions are required that can support a larger scale of activity, particularly ‘engaged research’ and network forms. Here, policy makers can draw on evidence from the vast US and European literature (for example, Niosi, 2006; Muscio 2010; Mustar et al. 2006). A different strategy is needed to build capabilities and scientific reputations at other universities, to extend, deepen and nurture nascent and niche ‘spots of interaction’. Such a problem does not have wide coverage in the literature, and requires new research to inform practice in late developing economies.

Fourth, new alternative kinds of intervention are also required that address socio-economic and community development needs at the same time. For example, initiatives to link farmers and informal sector actors into formal value chains and networks of interaction with MNCs and large firms, to create new ways of addressing poverty, inequality and social development priorities. This requires consideration of the emerging literature on innovation for inclusive development (Cozzens and Sutz 2014; Santiago 2014).

In conclusion, if linkages with firms are to be strengthened across a system of innovation to promote national development, it is critical to take into account a historically contextualised view from inside the higher education system, and unpack the complex intersection of individual and institutional incentives and barriers. Strategies for intervention need to be informed by the heterogeneity of intellectual, financial and development imperatives shaping patterns of academic engagement in diverse types of university.

Notes

However, we question the limited definition of university influence, which was measured in terms of whether a university was formerly a polytechnic, and the proportion of the research budget allocated to technology transfer activities.

This item was included in the survey instrument, based on evidence from a pilot study.

However, we find that the individual and the institutional characteristics—such as academic seniority, publication records or research environment—are strongly related to what we define as reputational standing and competition.

References

Abreu, M., & Grinevich, V. (2013). The nature of academic entrepreneurship in the UK: Widening the focus on entrepreneurial activities. Research Policy, 42, 408–422.

Albuquerque, E. (2003). Immature systems of innovation: Introductory notes about a comparison between South Africa, India, Mexico and Brazil based on science and technology statistics. Ficha catalográfica, A345i, 338, 45–62.

Albuquerque, E., Suzigan, W., Kruss, G., & Lee, K. (2015). Changing dominant patterns of interactions: Lessons from an investigation on universities and firms in Africa, Asia and Latin America. London: Edward Elgar.

Arza, V. (2010). Channels, benefits and risks of public-private interactions for knowledge transfer: Conceptual framework inspired by Latin America. Science and Public Policy, 37(7), 473–484.

Aschhoff, B., & Grimpe, C. (2014). Contemporaneous peer effects, career age and the industry involvement of academics in biotechnology. Research Policy, 43, 367–381.

Audretsch, D., & Lehmann, E. (2005). Do university policies make a difference? Research Policy, 34(3), 343–347.

Bekkers, R., & Freitas, I. M. B. (2008). Analysing knowledge transfer channels between universities and industry: To what degree do sectors also matter? Research Policy, 37, 1837–1853.

Bernardes, A., & Albuquerque, E. (2003). Cross-over, thresholds and the interactions between science and technology: Lessons for less-developed counties. Research Policy, 32(5), 867–887.

Boardman, P. C., & Ponomariov, B. L. (2009). University researchers working with private companies. Technovation, 29(2), 142–153.

Bozeman, B., Fay, D., & Slade, C. (2013). Research collaboration in universities and academic entrepreneurship: The-state-of-the-art. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 38(1), 1–67.

Bruneel, J., D’Este, P., & Salter, A. (2010). Investigating the factors that diminish the barriers to university–industry collaboration. Research Policy, 39(7), 858–868.

Carboni, O. (2013). Spatial and industry proximity in collaborative research: Evidence from Italian manufacturing firms. Journal of Technology Transfer, 38(6), 896–910.

Cesaroni, F., & Piccaluga, A. (2015). The activities of university knowledge transfer offices: Towards the third mission in Italy. The Journal of Technology Transfer. doi:10.1007/s10961-015-9401-3.

Cloete, N., Fehnel, R., Gibbon, T., Maassen, P., Moja, T., & Perold, H. (2006). Transformation in higher education: Global pressures and local realities. Dordrecht: Springer.

Cohen, W. M., Nelson, R. R., & Walsh, J. P. (2002). Links and impacts: The influence of public research on industrial R&D. Management Science, 48(1), 1–23.

Council on Higher Education (CHE). (2004). South African Higher Education in the first decade of democracy. Pretoria: CHE.

Council on Higher Education (CHE). (2010a). Community engagement in South African higher education. Kagisano no. 6. January.

Council on Higher Education (CHE). (2010b). Universities of technology—Deepening the debate. Kagisano 7. Pretoria: CHE.

Council on Higher Education (CHE). (2015). VitalStats: Public higher education, 2013. Pretoria: CHE.

Cozzens, S., & Sutz, J. (2014). Innovation in informal settings: Reflections and proposals for a research agenda. Innovation and Development, 4(1), 5–31.

De Fuentes, C., & Dutrenit, G. (2014). Geographic proximity and university–industry interaction: The case of Mexico. The Journal of Technology Transfer. doi:10.1007/s10961-014-9364-9.

Department of Education, South Africa (DoE). (2002). Transformation and restructuring: A new institutional landscape for higher education. Government Gazette no. 23549. Pretoria: Government Printers.

Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET). (2013). Statistics on post school education and training in South Africa: 2010. Pretoria: DHET.

DÉste, P., & Patel, P. (2007). University–industry linkages in the UK: What are the factors underlying the variety of interactions with industry? Research Policy, 36(9), 1295–1313.

DÉste, P., & Perkmann, M. (2011). Why do academics engage with industry? The entrepreneurial university and individual motivations. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 36(3), 316–339.

Dutrenit, G., & Arza, V. (2010). Channels and benefits of interactions between public research organisations and industry: Comparing four Latin American countries. Science and Public Policy, 37(7), 541–553.

Dyason, K., Lategan, L., & Mpako-Ntusi, T. (2010). Case studies in research capacity building. In CHE. Universities of technology: Deepening the debate. Kagisano 7. Pretoria: CHE.

Freitas, I. M. B., Marques, R. A., Paula, De, & e Silva, E. M. (2013). University–industry collaboration and innovation in emergent and mature industries in new industrialized countries. Research Policy, 42, 443–453.

Goel, R. K., Göktepe-Hultén, D., & Ram, R. (2015). Academics’ entrepreneurship propensities and gender differences. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 40(1), 161–177.

Gulbrandsen, M., & Smeby, J. (2005). Industry funding and university professors’ research performance. Research Policy, 34(6), 932–950.

Gurnasekara, C. (2006). Reframing the role of universities in the development of regional innovation systems. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 31, 101–113.

Harman, G. (2001). University–industry research partnerships in Australia: Extent, benefits and risks. Higher Education Research and Development, 20(3), 245–264.

Hewitt-Dundas, N. (2013). The role of proximity in university–business cooperation for innovation. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 38(2), 93–115.

Johnson, A., & Hirt, B. (2010). Reshaping academic capitalism to meet development priorities: The case of public universities in Kenya. Higher Education. doi:10.1007/s10734-010-9342-6.

Kenney, M., & Goe, R. (2004). The role of social embeddedness in professorial entrepreneurship: A comparison of electrical engineering and computer science and UC Berkley and Stanford. Research Policy, 33, 691–707.

Krücken, G. (2003). Learning the ‘New, New Thing’: On the role of path dependency in university structures. Higher Education, 46(315–339), 2003.

Kruss, G. (2005). Harnessing innovation potential? Institutional approaches to industry-higher education partnerships in South Africa. Industry and Higher Education, 19(2), 131–142.

Kruss, G. (2006). Working partnerships: The challenge of creating mutual benefit for academics and industry. Perspectives in Education, 24(3), 1–13.

Kruss, G. (2012). Reconceptualising engagement. A conceptual framework for analysing university interaction with social partners. South African Review of Sociology, 43(2), 5–26.

Kruss, G., Adeoti, J., & Nabudere, D. (2012a). Universities and knowledge-based development in sub-saharan Africa: Comparing university–firm interaction in Nigeria, Uganda and South Africa. The Journal of Development Studies, 48(4), 516–530.

Kruss, G., Visser, M., Aphane, M., & Haupt, G. (2012b). Academic interaction with social partners. Investigating the contribution of universities to economic and social development. Cape Town: HSRC Press.

Lindelof, P., & Lofsten, H. (2004). Proximity as a resource base for competitive advantage: University–industry links for technology transfer. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 29(3), 311–326.

Martinelli, A., Meyer, M., & von Tunzelmann, N. (2007). Becoming an entrepreneurial university? A case study of knowledge exchange relationships and faculty attitudes in a medium-sized, research-oriented university. Journal of Technology Transfer. doi:10.1007/s10961-007-9031-5.

Mowery, D., & Sampat, B. (2005). Universities in national innovation systems. In J. Fagerberg, D. C. Mowery, & R. R. Nelson (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of innovation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Muscio, A. (2010). What drives the university use of technology transfer offices? Evidence from Italy. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 35(2), 181–202.

Muscio, A., & Pozzali, A. (2013). The effects of cognitive distance in university–industry collaborations: Some evidence from Italian universities. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 38(4), 486–508.

Mustar, P., Renault, M., Colombo, M., Piva, E., Fontes, M., Lockett, A., et al. (2006). Conceptualising the heterogeneity of research-based spin-offs: A multi-dimensional taxonomy. Research Policy, 35, 289–308.

Niosi, J. (2006). Success factors in Canadian academic spin-offs. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 31(4), 451–457.

Nkomo, M., & Swartz, D. (2006). Within the realm of possibility: From disadvantage to development at the University of Fort Hare and the University of the North. Cape Town: HSRC Press.

Perkmann, M., Tartari, V., McKelvey, M., Autio, E., Brostrom, A., D’Este, P., et al. (2013). Academic engagement and commercialisation: A review of the literature on university–industry relations. Research Policy, 42(2), 423–442.

Perkman, M., & Walsh, K. (2008). Engaging the scholar: Three types of academic consulting and their impact on universities and industry. Research Policy, 37, 1884–1891.

Ponomariov, B. (2013). Government-sponsored university–industry collaboration and the production of nanotechnology patents in US universities. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 38(6), 749–767.

Pouris, A. (2007). The international performance of the South African academic institutions: A citation assessment. Higher Education, 54(4), 501–509.

Pries, F., & Guild, P. (2007). Commercial exploitation of new technologies arising from university research: Start-ups and markets for technology. R&D Management, 37(4), 319–328.

Prigge, G. (2005). University–industry partnerships: What do they mean to universities? A review of the literature. Industry and Higher Education, 19, 221–229.

Ramos-Vielba, I., & Fernandez-Esquinas, M. (2011). Beneath the tip of the iceberg: Exploring the multiple forms of university–industry linkages. Higher Education. doi:10.1007/s10734-011-9491-2.

Rapini, M., Albuquerque, E., Chave, C., Silva, L., de Souza, S., Righi, H., & da Cruz, W. (2009). University industry interactions in an immature system of innovation: Evidence from Minas Gerais, Brazil. Science & Public Policy, 36(5): 373–386.

Rivera-Huerta, R., Dutrénit, G., Ekboir, J. M., Sampedro, J. L., & Vera-Cruz, A. O. (2011). Do linkages between farmers and academic researchers influence researcher productivity? The Mexican case. Research Policy, 40, 932–942.

Rizzo, U. (2015). Why do scientists create academic spin-offs? The influence of the context. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 40(2), 198–226.

Santiago, F. (2014). Innovation for inclusive development. Innovation and Development, 4(1), 1–4.

Schartinger, D., Schibany, A., & Gassler, H. (2001). Interactive relations between universities and firms: Empirical evidence from Austria. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 26(3), 255–268.

Secondo, R., & Ugo, F. (2014). University Third mission in Italy: Organization, faculty attitude and academic specialization. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 39(3), 472–486.

Shah, S., & Pahnke, E. (2014). Parting the ivory curtain: Understanding how universities support a diverse set of startups. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 39(5), 780–792.

Suzigan, W., & Albuquerque, E. (2011). The underestimated role of universities for the Brazilian system of innovation. Brazilian Journal of Political Economy, 31(1), 3–30.

Tanga, L., Debackere, K., & von Tunzelmann, N. (2003). Entrepreneurial universities and the dynamics of academic knowledge production: A case study of basic vs applied research in Belgium. Scientometrics, 58(2), 301–320.

Tartari, V., & Salter, A. (2015). The engagement gap: Exploring gender differences in university–industry collaboration activities. Research Policy, 44, 1176–1191.

Thatiah, K., & Schauffer, D. (2007). How now ‘cloned’ cow? Challenging conceptualisations of South African universities of technology. South African Journal of Higher Education, 21(1), 181–191.

Tjissen, R. (2004). Is the commercialisation of scientific research affecting the production of public knowledge? Global trends in the output of corporate research articles. Research Policy, 33, 709–733.

Van Looy, B., Ranga, M., Callaert, J., Debackere, K., & Zimmerman, E. (2004). Combining entrepreneurial and scientific performance in academia: Towards a compound and a residual Matthew-effect? Research Policy, 33(3), 425–441.

Whitley, R. (2000). The intellectual and social organization of the sciences. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Whitley, R. (2003). Competition and pluralism in the public sciences: The impact of institutional frameworks on the organization of academic science. Research Policy, 32, 1015–1029.

Winberg, C. (2005). Continuities and discontinuities in the journey from technikon to universities of technology. South African Journal of Higher Education, 19(2), 189–200.

Wright, M. (2014). Academic entrepreneurship, technology transfer and society: Where next? The Journal of Technology Transfer, 39(3), 322–334.

Wright, M., Clarysse, B., Lockett, A., & Knockaert, M. (2008). Mid-range universities’ linkages with industry: Knowledge types and the role of intermediaries. Research Policy, 37, 1205–1223.

Acknowledgements

The research was funded by a Grant from the National Research Foundation (NRF), South Africa.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kruss, G., Visser, M. Putting university–industry interaction into perspective: a differentiated view from inside South African universities. J Technol Transf 42, 884–908 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-016-9548-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-016-9548-6