Abstract

Universities have long been involved in knowledge transfer activities and are increasing their efforts to collaborate with industry. However, universities vary enormously in the extent to which they promote, and succeed in commercializing, academic research. In this paper, we focus on the concept of cognitive distance, intended as differences in the sets of basic values, norms and mental models in universities and firms. We assess the impact of cognitive distance on university-industry collaborations. Based on original data from interviews with 197 university departments in Italy, our analysis determines whether cognitive distance is perceived as a barrier to university-industry interactions, and estimates its effects on the frequency of their collaborations. Our results confirm that cognitive, albeit not affecting the probability of departments to collaborate with firms, significantly hinders the frequency of interactions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The current phase of development of the university system can be described as one of institutional reconfiguration (Geuna 1999), in which societal demands emanating from deep changes to world economic systems, are contributing to the emergence of new organizational arrangements and practices. The university’s role is changing progressively: universities not only have to cope with research and teaching, but also are having to become poles of potential economic and social development (Geuna and Muscio 2009). A new range of activities, described as technology transfer and research exploitationFootnote 1 is gaining ground and leading to increased interactions with the industrial sector (Cohen et al. 2002; Meyer-Krahmer and Schmoch 1998).

However, the closer involvement of universities with the market is highlighting the need for a restructuring of the internal organization and management of research activities (Gibbons et al. 1994), and this is promoting forms of organizational and cultural resistance to change. Problems related to communication and interaction between universities and industry are based on the different languages spoken by these two spheres, which are resulting in misunderstandings.

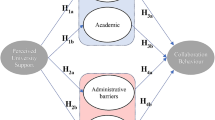

In this paper, we are interested in assessing whether and to what extent the phenomena linked to the social and cultural divide that has been traditional between universities and firms, is presenting a barrier to the development of university-industry interaction and collaboration. We present and discuss the results of a survey of 197 Italian university departments conducted in 2007. We are interested in exploring whether the set of values, norms and incentives that apply to universities, which are different from those prevailing in the industrial sector, are the source of the cultural and cognitive heterogeneity between these two worlds and are affecting the easiness of communication and interaction between them. We investigate whether cognitive distance, broadly defined as the degree of diversity in research methodologies and in the use and interpretation of knowledge, impacts on the capability of departments to interact with industry.

The paper is organised as follows: Sect. 2 sets out the theoretical background and explains why cultural heterogeneity is worth exploring in an analysis of university-industry collaboration. Section 3 discusses the results of a questionnaire survey and presents some descriptive statistics for the frequency and nature of university-industry collaborations, the obstacles to collaboration, and the effect of cognitive distance. We also present the results of a set of negative binomial regression models measuring the impact of cognitive distance on the frequency of collaborations at the aggregate level and in specific areas of interaction. Section 4 discusses the overall results showing that cognitive distance hampers university-industry collaboration. We discuss the implications of these findings for future research.

2 Theoretical background

Scientific and technological knowledge are seen increasingly as important sources of competitiveness. Business success in the market depends crucially on the ability to develop, acquire and recombine knowledge from different sources and use it to develop new products and processes. Firms can no longer rely on their internal knowledge resources, but need to find efficient ways to manage a complex set of knowledge inflows and outflows within the boundaries of their organization (Chesbrough et al. 2006; Amesse and Cohendet 2001). Within this framework, universities represent an invaluable source of qualified knowledge, and commercial exploitation of scientific output increasingly is seen as the driver of competitiveness and growth. However, while firms are seeing interaction with universities as essential for their strategies (Faulkner et al. 1995), the universities are under political and societal pressure, to adopt an explicit ‘entrepreneurial’ stance (Clark 1998). Several countries have introduced progressive cuts in research funding that have encouraged universities to collaborate with industry and develop initiatives in favour of knowledge transfer (Muscio 2010). Universities are now more committed than in the past to embracing their ‘third mission’, and work to become poles of local economic development, which involves expanding the range of their outreach activities and their relationships with the private sector (Gulbrandsen and Slipersæter 2007).Footnote 2

The incorporation of the third mission within the scope of academic activity is not an easy task. Long established universities have developed a complex set of values, beliefs, organizational practices, and implicit and explicit norms of conduct, none of which can be expunged by a simple act of will. Among the many problems is the significant tension between the ideal norms of ‘open science’ and the Mertonian ethos (Merton 1973), which for so long contributed to orienting the structure and conduct of research in academia, and the business-type imperatives that are at the basis of strategies aimed at the commercialization of research based on strong intellectual property rights (IPR) protection, licensing activities and creation of spinoff firms. Universities are being required to learn how to manage the potential conflict between the need to continue to see scientific knowledge as a public good, at least in part, and the management of patenting and commercialization activities in which knowledge is regarded as something for sale to the highest bidder (Slaughter and Rhoades 2004; Powell and Owen-Smith 1998).

A detailed analysis of the process of university-industry collaboration must take into consideration the complex interplay among the variables at different levels: the system level, described in the systems of innovation literature (Edquist 2005); the institutional level, which explains the differences among universities operating within the same system (Di Gregorio and Shane 2003); and the individual level (Bercovitz and Feldman 2008). At the institutional level universities need to find a way to regulate and manage a whole new set of activities, while at the individual level scientists may directly experience the kind of cognitive dissonance that arises when there is a requirement to reconcile conflicting aims and values (Cooper 2007; Festinger 1957). Faced with such pressures, the scientist may decide to adopt a specific line of conduct, depending on his or her personal propensity to embrace the ‘Mertonian’ or the ‘business’ ethos. Etzkowitz (1998, 830) describes how different degrees of involvement with private firms arise, from ‘hands-off’ scientists who leave all such arrangements to the university technology transfer office (TTO), to those preferring a ‘seamless web’ who actively seek to integrate their research with the research programmes of their collaboration partners.

The personal involvement of faculty is considered critical for the process of transferring technology from universities to firms, especially because most university technologies are embryonic and need further development in order to become a real commercial asset (Thursby and Thursby 2003, 2004). Determining whether or not the growing involvement of universities in licensing is detrimental to activities such as research and teaching is a critical issue. General models (Thursby et al. 2007) and empirical work (Thursby and Thursby 2007) investigate how researchers should allocate their time among different activities in the course of their careers, but more work is needed on linking individual behaviours to the structure of incentives at the institutional level.

It seems clear that, in order to gain a deeper understanding of the motivations for faculty to engage in research exploitation activities, we need to consider how individual behaviour interacts with the changes taking place at the institutional level. To address this, in this paper we focus on indicators that characterize the organizational and cultural environment in which academic researchers operate, in order to analyse whether these variables have an influence on the propensity to engage in collaborations with industry. In particular, we consider how cognitive distance, defined broadly as the degree of diversity in research methodologies and in the use and interpretation of knowledge, can influence the process of technology transfer. A certain degree of cognitive heterogeneity between the partners involved in a collaboration generally is considered to represent advantage in favouring knowledge pooling and, thus, the development of new and unexpected ideas (Von Hippel 2005). University-industry collaborations are characterized by complex patterns of bidirectional knowledge exchanges (Meyer-Krahmer and Schmoch 1998), and US surveys show that faculty members consider the possibility of advancing their own research agenda as an important incentive for developing collaborations with firms (Lee 2000). This kind of evidence would suggest that universities and industry collaborate as long as both parties think that the activity will provide insights for the development of innovative ideas and new knowledge. However, if the cognitive distance is too great, this can hamper the process of communication between the parties and render the transfer of knowledge impossible. In this paper we investigate empirically whether cognitive distance represents an opportunity for knowledge exchange or indeed acts as a barrier against collaboration.

In the literature, issues related to cognitive distance in innovation tend to be addressed using the framework developed by Nooteboom et al. (2007), who measure it in terms of the correlation between the technology profiles of firms involved in alliances. To our knowledge, no attempts have been made to analyse the issue of cognitive heterogeneity in the field of university-industry collaboration. In this paper, we consider two specific dimensions: to what extent cognitive distance is perceived to represent a barrier to university-firm linkages; and how cognitive distance influences the propensity for university-firm linkages. We analyse these dimensions by asking university researchers directly for their perceptions, as this provides immediate insight into the ways in which cognitive distance is perceived and experienced by universities.

We distinguish between universities with a history of interaction and relationships with the private sector and those that do not collaborate with firms. We would expect to find some differences between the way cognitive distance is perceived to represent an obstacle to technology transfer, and the way in which it represents a real barrier. It could be argued that university researchers who have never collaborated with the private sector are more likely to adhere to the set of values and norms typical of the Mertonian ethos and to perceive themselves as remote from the business orientation typical of the private sector. It might be expected that the perception of the relevance of cognitive distance as an obstacle to knowledge transfer would be greater among those academic institutions that do not collaborate with the private sector.

On the other hand, repeated interactions with firms provide university researchers with a better understanding of the different norms, values, mental models and frames of reference that apply to the private and academic sectors. The experience of collaboration should lead to greater convergence in attitudes, making it easier to arrive at a common understanding of the different aspects of the collaboration process (Bruneel et al. 2010). In this case, it might be expected that cognitive distance would have a positive influence on the propensity of universities to enter into collaborations with firms because it would increase the probability that each partner could gain useful insights in the process.Footnote 3 In other words, academics and business representatives may have different mindsets, but their differences should not interfere with their capability to interact.

To sum up, we would expect that university researchers who never collaborate with the private sector would be inclined to think that cognitive distance would be a major obstacle to the development of successful relationships with firms and that university researchers with a history of collaboration with the private sector would be more inclined to think that a certain degree of cultural heterogeneity would facilitate university-industry interaction.

3 Empirical evidence

3.1 Description of the data

The empirical analysis is based on a web survey, carried out between June and September 2007,Footnote 4 which targeted Italian university departments engaged in research in the Engineering and Physical Sciences (EPS). Survey participants were asked to complete a detailed questionnaire on their departments’ knowledge transfer activities and university-industry collaborations during the period 2004–2007. The questionnaires were addressed to the directors of 1,047 EPS departmentsFootnote 5; the response rate was 18.8 % (197 completed questionnaires).Footnote 6 Our choice of department directors to respond to the questionnaire rather than individual faculty members was to keep the focus at the institutional rather than the individual level. We would argue that department directors are best positioned to provide an aggregate level assessment of differences in the decision-making attitudes and organizational cultures of universities and firms. The sample is highly representative. The differences between the weights of department types (e.g. between departments in large universities and in medium-sized universities doing medical research, etc.) and the correspondent total population are generally below 3 %.Footnote 7 To check the representativeness of our sample, we compared the share of departments in the survey with established collaboration agreements with industry, with the share of EPS departments which, according to MIUR official university financial data, had received funding from industry in 2007. Given that the difference was only 1.5 %, we can conclude that the sample is representative and does not suffer from selection bias.Footnote 8

3.2 University-industry collaboration

In 2004–2007, 85.8 % of departments collaborated with industry. In 43.1 % of cases the number of collaborations has increased over time, and in 38.6 % of cases it has been stable. Table 1 describes the typology of collaboration agreements signed during the period 2004–2007. We identified 12 types of collaboration and, following D’Este and Patel (2007), we grouped them into 5 macro-areas: (1) Physical facilities, (2) Consultancy and contract research, (3) Collaborative research agreements, (4) Training, (5) Meetings and conferences. Table 1 shows that, during the period of the analysis, departments signed several types of agreements for cooperation with industry, ranging from creation of physical facilities to consultancies and contract research, collaborative research agreements, training programmes and joint participation in meetings and conferences. The majority of these collaborations was in the areas of research contracts (39.9 %), consultancies (22.2 %) and joint research projects (11.5 %). Most collaborations (62 %) are based on consultancy and contract research agreements, followed by organisation of and/or participation in meetings and conferences (14 %) and collaborative research agreements (11.5 %).

In 47.1 % of cases, collaboration is established directly between departments and companies, without the involvement of a third party (Muscio 2010). If a third party is involved, in 34.9 % this is another university, or a university TTO (19.5 %), or another firm (19.5 %). Collaborations are generally promoted by professors (82.7 %), departments (43.5 %) or company representatives (48.2 %).

3.3 Barriers to interaction with industry

Interviewees were asked to indicate, on a 5-point Likert scale, the main barriers to interaction with industry. Table 2 compares the relevance of these barriers for two groups of departments, those that collaborated with companies in the period 2004–2007 and those that did not. The last two columns in Table 2 report the results of independent sample T tests. Departments interacting with industry indicated that the barriers to interaction are related mainly to finding appropriate business partners, and lack of funding for joint research, but also included the short-term orientation of industry research, different (on both sides) expectations and work priorities, and absence of university procedures to regulate cooperation.

Overall, the barriers are higher for non-collaborating departments although the types are generally similar. The short-term orientation of research seems not to be an issue for non-collaborators, but a lack of fit between the department’s research and commercialization was highlighted. In most cases the obstacles were the same for both groups of departments. In only a few cases are the differences in means significant: departments collaborating with industry face significantly lower barriers related to university procedures governing collaboration and, in most cases, their research is suitable for commercialization. These departments also have more people from industry in their networks and find it easier to make contact with companies.

Cognitive distance was defined in the questionnaire as the degree of diversity in research methodologies and in the use and interpretation of knowledge. Using a 5-point Likert scale, directors were asked to estimate the magnitude of the cognitive distance between them and industry partners, and its impact on collaboration. We identified five possible areas where cognitive distance could have an impact: ‘choice of research thematic areas’ addresses differences in the domain of knowledge; ‘research methodology’ refers to differences in the way in which specific problems are targeted, framed and solved; ‘typology of pursued results’ and ‘criteria for selection of projects to be transferred to market’ indicate differences between ‘open science’ and private sector norms; differences in ‘timing of expected results’ has been shown to be among the most important dimensions of cognitive distance in exploratory research on the differences in cognitive styles between academic and private researchers (cfr. also Bruneel et al. 2010).

The estimated average scores for collaborating and non-collaborating departments are compared in order to determine whether cognitive distance is a more tangible barrier to collaboration for those departments that had not collaborated with industry during the period 2004–2007. Table 3 shows that cognitive distance is ‘moderately relevant’ for both groups. There is no significant difference between the two groups of departments; estimates are fairly similar for all the areas of cognitive distance identified and since the P value is greater than the significance level, we cannot reject the null hypothesis that cognitive distance is the same for both groups (collaborating and not collaborating with industry) on average. This suggests that the perception of cognitive distance as a barrier to knowledge transfer is not linked to the propensity to collaborate with firms.

3.4 Econometric analysis

3.4.1 Description of the variables

We conducted an econometric analysis on the determinants of university-industry collaboration to examine more deeply the influence of cognitive distance on the propensity for universities to engage in collaborations with the private sector. We focused particularly on the effects of cognitive distance indicators on departments’ capabilities to cooperate with companies. The dependent variable, COLLAB, accounts for the frequency of collaborations, measured by the number of collaborations signed by the department during the period 2004–2007. Since COLLAB is based on count data and the distribution of collaborations is skewed, we use a negative binomial regression model. Statistical tests for overdispersion showed that the negative binomial estimation provides a significantly better fit for the data than the more restrictive Poisson model. We also run a zero-inflated-negative-binomial-regression and a Vuong test. The test results indicate that the negative binomial regression is the most appropriate estimation method.

We also tested and corrected sample selection bias using the Heckit method (Heckman 1979; Hill et al. 2011). This was necessary because, in principle, the magnitude of cognitive distance can affect with different intensity the probability to engage or not into a collaboration agreement and the frequency of agreements. The rationale for this consists in assuming that when cognitive distance is perceived as being too great, there would be no possibility of interaction, as no common grounds can be found between the partners. However, once interactions are established, specific differences in cognitive styles, norms and values, can make it harder for partners to interact efficiently, and this can lower the frequencies of collaborations, even in cases where there is some potential for the development of collaborations.

The independent variables control for four types of determinants: departmental characteristics, research indicators, geographical indicators and collaboration indicators. COGN_DIST controls for the opinions of department directors of the relevance of cognitive distance between professors and industrialists (1 = low to 5 = high). Table 4 presents information on the variables used in the regressions; Table 5 reports some descriptive statistics. The use of a subjective indicator of cognitive distance raises the issue of endogeneity (frequency of collaborations driving cognitive distance). Although the descriptive analysis (presented in Table 3) shows that collaborating and non-collaborating departments are similar in terms of relevance of cognitive distance, there is the possibility that those departments that scored it higher are those with more experience of interacting with industry (i.e. high frequency of collaboration) and, therefore, a better understanding of the differences in the mindsets of academics and industrialists. In order to address endogenous cognitive distance we identify some instruments for the creation of an instrumental variable (IV). Given that the indicator COGN_DIST is an ordered variable ranging from 1 to 5, we created an IV with the expected values of an ordered probit regression using as regressors the determinants of cognitive distance identified as type of university research (basic, applied, experimental) and the presence at the university of a TTO. We believe these variables are good instruments because they represent valid drivers of cognitive distance. For the presence of a TTO, we followed Clark’s (1998, 2004) model, which treats the development of an outreach structure linking the academic core with the outside world, as important for the development of an entrepreneurial university. According to Clark (1998, 6), universities that want to create and maintain linkages with the external world need to establish a complex infrastructure of ‘professionalized outreach offices that work on knowledge transfer, industrial contact, intellectual property development, continuing education, fundraising, and even alumini affairs’. Many university TTOs in Italy were established to reduce cognitive distance by providing a bridge between academic research and industry needs and to broker university-industry interactions (IPI 2005; Muscio 2010).Footnote 9 The findings of the Netval survey (Piccaluga and Balderi 2006) show that the primary objectives of TTOs in Italy are to diffuse an entrepreneurial culture of research, support university spin-offs and promote economic exploitation of research output and academic competencies. We also consider type of research to be an indicator of the general attitude to industry application and capitalization of knowledge. Etzkowitz (1998, 825) argues that the development of an entrepreneurial science is mainly driven by two dynamics: ‘one is an extension of university research into development, the other is an insertion into the university of industrial research goals, work practices and development models’. Greater involvement of faculty in applied research and development, and detachment from the traditional model that equates science with basic and theoretical research, are considered factors that can lead to the development of new ways of thinking and new norms that are sympathetic to the creation of new institutional arrangements in an entrepreneurial university model. We assume that universities that do not have a TTO and are focused on basic research rather than on applied or experimental research, present a greater cognitive distance from industry.

3.4.2 Estimation of the determinants of university-industry collaboration

Table 6 reports the estimated parameters and marginal/impact effects. To determine whether selection is a problem, we first estimate the probability of collaborating with industry with a probit model.Footnote 10 We then calculate the inverse mills ratio (LAMBDA) for those departments collaborating with industry and include this ratio as an additional regressor in our negative binomial regression model.

The results of the probit model and the corresponding marginal effects are reported in columns 1 and 2 of Table 6. The results of the negative binomial regression are reported in columns 3 and 4. Two results are of note. First, the estimated coefficient of LAMBDA is significant and negatively signed—which suggests that there is a selection bias and that the error terms in the selection and primary equations (where LAMBDA is not included) are negatively correlated. So (unobserved) factors that make collaboration more likely tend to be associated with lower collaboration frequency.Footnote 11 Second, cognitive distance (COGN_DIST) has no significant effect on the probability of establishing collaborations, whilst it has a highly significant negative effect on the intensity of interaction, with a very high estimated marginal effect (for a 1-step decrease in cognitive distance the frequency of collaborations increases by 13.2 %). These results confirm that the cognitive distance between universities and firms does not affect the establishment of a linkage with industry but hampers greatly the frequency of interactions. These findings corroborate the fact that the magnitude of cognitive distance between universities and industry is not so great as to impede that these two worlds can, in principle, interact. However, the specific dimensions of cognitive distance that can manifest in the course of the interaction can substantially hamper the process of cooperation.

Motivation to collaborate with firms in order to access industry knowledge (D_KNOWLEDGE) decreases the probability to engage in collaborations but does not affect their frequency. Conversely the possibility of industry funding for university research (D_FUNDING) does not drive probability of interaction but increases marginally their intensity. Therefore, although knowledge exchange is a barrier to the establishment of what might become fruitful relationships, departments’ search for funding seem to have an impact on frequency of interactions, which is not surprising given the substantial reduction in government funding for research in Italy since 2005.

Previous involvement in regular collaboration (COLLAB04) influences a department’s capability to collaborate frequently with industry. Our results confirm the findings of Arvanitis et al. (2008) who prove that institutes that have already collaborated with industry—reflected by a high share of external funding in the institutional budget—are more likely to be involved in knowledge transfer activities generally.

Department director’s experience (EXP_DIR_DEPT) does not have a significant effect either on the probability of interaction or on their intensity. Therefore directors with longer experience are no more likely to sign agreements than younger ones. This might be due to the fact that collaborations are primarily promoted by professors and not by departments.

Size of departments, of universities or location in a university specialized in EPS do not have a significant impact on probability or frequency of collaborations. Academic institutions located in southern Italy are not disadvantaged with respect to institutions located in central and northern Italy in terms of establishing collaborations with firms (SOUTH). Similarly, the proximity of the university to science-based firms does not seem to affect the intensity of university-industry collaboration (SB_IND_PRO). Apparently, university collaborations are not confined to local industry, as many departments look beyond their own regions to find potential business partners.

Applicability of research to industry has been found to have a positive effect on the frequency of university-industry collaborations (Mansfield 1998). Our findings confirm this, at least for what concerns the development of interactions, if not their frequency: RES_APPLIC has a positive impact on the probability of collaborations (for a 1-step increase in research applicability the frequency of collaborations increases by 0.1 %).

As far as research quality is concerned, the empirical literature is less clear, with some studies showing that it has a significant influence on the frequency of university-industry collaborations (Mansfield 1995) and others finding the impact limited to joint research, but not to other types of interaction (Schartinger et al. 2001). In our case, research performance (RES_RATING) has no significant impact either on the probability or on the frequency of interaction. What really matters to increase the probability of interaction is the applicability of research to the industry context, not its quality, judged by traditional academic standards. It can be assumed that less prestigious departments might achieve comparative advantage from addressing real firm needs; in most cases, firms want immediate and efficient solution to very specific and focused problems, not leading edge research (D’Este and Patel 2007). Supporting this, we can refer to qualitative evidence provided by a series of focus groups involving university and industry researchers that were held in Milan between November 2006 and September 2007 (Fondazione Rosselli 2009).Footnote 12

The focus groups involved three sectors (biotechnology, production systems, and domotics) which, according to previous research on the priorities of industry reserarch in Italy (Fondazione Rosselli 2005), were particularly relevant in economic terms, and were characterized by significant flows of knowledge between universities and firms. For each sector, four university delegates (professors involved in business consultancy and technology transfer) and four representatives of private firms (R&D managers and industry researchers) were chosen, with a total of 24 people involved. Focus group participants were asked to discuss how and to what extent cognitive distance between universities and firms hampered the process of technology transfer, and also the most significant ways in which cognitive distance was manifested. One of the most consistent finding (Fondazione Rosselli 2009) was industry researchers finding academic research ‘too advanced’ for their needs; they would prefer universities to develop some sort of ‘catalogue’ of less up-to-date knowledge, which may be of less scientific interest, but could be of more practical value for industry.

We understand that grouping different types of collaborations when exploring issues such as cognitive distance could be problematic. In fact it could be possible that certain types of collaboration are more affected than others by cognitive distance. In order to address this issue, we extended our analysis by running the same econometric model for each of the five macro-areas of collaboration identified in Table 1, and defined by D’Este and Patel (2007): (1) Physical facilities, (2) Consultancy and contract research, (3) Collaborative research agreements, (4) Training, (5) Meetings and conferences. Overall, we can see that university-industry collaborations are diverse and that certain types of collaboration are more affected by cognitive distance. The degree of involvement of partners, the overall complexity of the collaboration process, and the dynamics of knowledge exchange flows vary for different forms of collaborations; therefore, we explore whether cognitive distance affects some channels of interaction more than others. The results are presented in Table 7. As in the previous regression, we test and correct for selection bias. The results of the probit model and the corresponding marginal effects are reported in the first two columns of each of the five sets of regressions.

The disaggregated analysis largely confirms the results of the grouped model and our research hypotheses. Cognitive distance still does not affect probability of interaction, whilst it negatively affects collaboration in the first three areas: (1) Physical facilities, (2) Consultancy and contract research, (3) Collaborative research agreements. These collaborations alone represent nearly 75 % of total collaboration agreements signed in the period considered. We can also note that these are the types of interactions in which processes of mutual exchange of knowledge should likely be more intense (e.g. in running lab tests and discussing the results with industry clients or in interacting to reach shared research goals). Cognitive distance is more detrimental in the process of carrying out these interactions than in areas such as the joint attendance to meetings and conferences or the training of company employees.

4 Conclusions

In this paper, we analysed how cognitive distance between universities and firms, considered as basic differences in values, norms and mindsets, is perceived and how much it represents a barrier to knowledge transfer. In the course of a survey of 197 directors of Italian university departments we enquired about the magnitude and effects of cognitive distance on collaboration with firms. The empirical evidence seems unambiguously to show that cognitive distance between universities and firms does not prevent the possibility of establishing fruitful collaborations, but it significantly hampers the frequency of collaborations. In other words, there might be a certain potential for the establishment of long-term and continuous university-industry collaborations, that is not fully exploited because of the presence of cognitive distance.

In relation to university departments’ perceptions of cognitive distance as a barrier to technology transfer, our analysis shows that there are no significant differences between universities that do and do not collaborate with firms. This finding is rather surprising since we might expect greater familiarity with industry would lead university researchers to modify their evaluation of cognitive distance. More specifically, our results would seem to rule out the possibility that more interactions leads to learning effects that enable universities and firms to develop a sort of common ground that promotes more collaboration. If we compare our results with Bruneel et al. (2010), we see that what they label ‘orientation-related barriers’, that is, barriers’ related to differences in the orientation of industry and universities’ is similar to our concept of cognitive distance. However, their empirical analysis results suggest that ‘routines learnt through conducting joint research with universities, lower the barriers related to the basic and long-term nature of university research, helping to overcome attitudinal differences between the partners on research methods and targets’ (Bruneel et al. 2010, 864). We could speculate that this difference might be explained by the different context (Italy vs UK), or by the fact that Bruneel et al. were considering firms’ perspectives, and our study focuses on universities. Concerning this last point, the qualitative focus group evidence we gathered suggests that firms perceive cognitive distance as a real barrier to the development of useful interactions with universities. Some dimensions of cognitive distance, linked specifically to the selection of research areas and the long-term orientation of university research, were seen as representing obstacles strongly limiting firms’ relation to the academic world. This find was the more significant as the industry researchers participating in focus groups had histories of collaboration with universities.

The econometric analysis provided further evidence that cognitive distance has a strong negative influence on the frequency of interactions between universities and firms: this holds for collaborations generally and also for specific types of university-industry interactions. We might expect that since the degree of involvement among partners, overall complexity of the collaboration process, and the dynamics of knowledge exchange vary for different forms of collaborations, cognitive distance might have different impacts on different types of collaboration. The fact that cognitive distance has a negative impact on many different kinds of collaboration, despite specific differences among them, supports the hypothesis that it is a significant barrier to technology transfer.

The study in this paper has some limitations. First, our estimates are based on a cross-section of university departments, which reduces the ability to check the robustness of results under alternative procedures to address endogeneity and department heterogeneity. Second, we consider only universities’ conceptions. We tried to integrate our results with qualitative evidence that takes account of firm views and overall find that the results are consistent, but more detailed exploration of how cognitive distance is perceived by firms would highlight whether important aspects of this concept have been missed by the current study. In particular, it would be interesting to investigate whether the intrinsic multidimensionality of the concept of cognitive distance is adequately accounted for by the indicators we consider, or if other aspects are worth exploring. It is likely also that some dimensions of cognitive distance might be more or less important than others, depending also on context: this should be addressed by future research.

Although speculative, the indicators of cognitive distance applied in this study provide useful information on how cognitive distance is perceived by university researchers. This is important from a cultural perspective, since it allows inferences about the ways in and extent to which cognitive distance can influence university attitudes and behaviours. In contexts, such as the Italian one, which historically are not characterized by high levels of university-industry interactions, our results suggest the need to find ways to reduce the cognitive distance between the two worlds. From this perspective, the development of a broader and more efficient infrastructure of outreach organizations, such as TTOs, that are able to link the core of academia with the external world, might be a very important step towards reducing the gap between universities and firms.

Notes

Following Chiesa and Piccaluga (2000, 339), we use the term ‘research exploitation’ to refer ‘to all the ways in which universities obtain revenues from their scientific research activities’. Research exploitation, in this sense, includes traditional or ‘user-directed commercialization’ activities, such as contract research and collaboration, consultancy and expert advice, together with ‘science-directed commercialization activities’, such as patenting, licensing and spinoff venturing (Gulbrandsen and Slipersæter 2007, 117). Although there is not a clear cut distinction between these categories, it should be remembered that user-directed activities were traditionally carried out by universities, while science-directed commercialization activities are more recent developments. ‘Another important dividing line between the two types of commercialization is that user-directed activities seem to thrive within traditional academic departments, laboratories and units, while science-directed activities may require a broader support structure in the form of TTOs, seed funding and so on’ (Gulbrandsen and Slipersæter 2007, 117).

This holds especially for European universities. In the US, community outreach and development has a long history and was a key driver of the establishment of land-grant universities. However, as Clark (2004, 133) underlines, the US system of higher education presents some specific characteristics (large size, decentralized control, institutional diversity, strong competition between institutions, high level of autonomy), which contribute to making it significantly different from any other system. In most European countries third mission activities, even if not completely new, expanded significantly after the early 1980s. Even in the US, some specific activities, such as patenting, licensing and spinning off new ventures, increased dramatically following the Bayh-Dole Act and related policy measures adopted in the early 1980s (Thursby and Thursby 2003, 2004, 2007).

Again, this holds only if the cognitive distance is not so great as to completely impede the process of communication between the two parts.

The survey was carried out as part of the research project ‘The Governance of Technology Transfer in Italy’, funded by the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MIUR), FIRB project: ‘A Multidimensional Approach to Technology Transfer’.

The list of departments is available at: www.cineca.it. Contact details were available for 1,047 out of 1,116 directors.

Population weights were applied to the econometric analysis. However, the estimations were remarkably similar to those estimated without weights.

The exceptions are the scientific area “Medicine”, which is slightly underrepresented for departments in both large and very large universities (respectively—9.3 and −7.1 %) and “Agriculture and Veterinary” (+4.3). When population weights are applied the estimated results are remarkably similar to those estimated without weights.

We estimated that the share of departments in EPS that received funding from industry in 2007 was 84.28 % (1,013 out of 1,202 departments) whilst the share of departments that collaborated with industry is 85.8 % in our survey.

IPI, a former consulting body within the Ministry for Economic Development, conducted a survey of TTO in Italy (IPI 2005) investigating their activities and how well their services match industry demand for services.

The probit model is based on the same regressors of the negative binomial model with the exception of COLLAB04 and the dummies for scientific areas, which predict success perfectly (all zeros correspond to zeros of the dependent variables). This is because 100 % of departments in some scientific areas (e.g. engineering) collaborate with industry.

For example, this could be the case of departments composed of younger researchers, that despite their high productivity levels (which can have a positive impact on the frequency of collaborations) do not have the necessary connections with industry of their senior counterparts. Therefore, these departments could have fewer opportunities to engage in research contracts and consultancies than departments with older staff.

The focus groups were carried out over the same time period of the questionnaire survey and as part of the same research project on technology transfer processes (cfr endnote n. 4).

References

Amesse, F., & Cohendet, P. (2001). Technology transfer revisited from the perspective of the knowledge-based economy. Research Policy, 30, 1459–1478.

Arvanitis, S., Kubli, U., & Woerter, M. (2008). University-industry knowledge and technology transfer in Switzerland: What university scientists think about co-operation with private enterprises. Research Policy, 37, 1865–1883.

Bercovitz, J., & Feldman, M. (2008). Academic entrepreneurs: Organizational change at the individual level. Organization Science, 19, 69–89.

Bruneel, J., D’Este, P., & Salter, A. (2010). Investigating the factors that diminish the barriers to university–industry collaboration. Research Policy, 39, 858–868.

Chesbrough, H., Vanhaverbeke, W., & West, J. (Eds.). (2006). Open innovation: Researching a new paradigm. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chiesa, V., & Piccaluga, A. (2000). Exploitation and diffusion of public research: The case of academic spin-off companies in Italy. R&D Management, 30, 329–339.

Clark, B. R. (1998). Creating entrepreneurial universities: Organizational pathways of transformation. Oxford: Pergamon-Elsevier Science.

Clark, B. R. (2004). Sustaining change in universities. Continuities in case studies and concepts. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Cohen, W. M., Nelson, R. R., & Walsh, J. P. (2002). Links and impacts: The influence of public research on industrial R&D. Management Science, 48, 1–23.

Cooper, J. (2007). Cognitive dissonance: 50 years of a classic theory. London: Sage.

D’Este, P., Nesta, L., & Patel, P. (2005). Analysis of university–industry research collaborations in the UK: Preliminary results of a survey of university researchers, SPRU Report for a project funded by EPSRC/ESRC.

D’Este, P., & Patel, P. (2007). University–industry linkages in the UK: What are the factors underlying the variety of interactions with industry? Research Policy, 36, 1295–1313.

Di Gregorio, D., & Shane, S. (2003). Why do some universities generate more start-ups than others? Research Policy, 32, 209–227.

Edquist, C. (2005). Systems of innovation. Perspectives and challenges. In J. Fagerberg, D. C. Mowery, & R. R. Nelson (Eds.), The oxford handbook of innovation (pp. 181–208). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Etzkowitz, H. (1998). The norms of entrepreneurial science: Cognitive effects of the new university–industry linkages. Research Policy, 27, 823–833.

Faulkner, W., Senker, J., & Velho, L. (1995). Knowledge frontiers. Public sector research and industrial innovation in biotechnology, engineering ceramics and parallel computing. Oxford: Clarendon.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Rosselli, Fondazione. (2005). Le priorità nazionali della ricerca industriale. Secondo rapporto. Milano: Guerini e Associati.

Fondazione Rosselli. (2009). Modelli socio-cognitivi nel sistema della ricerca pubblica e nel mondo delle imprese, FIRB research report.

Geuna, A. (1999). The economics of knowledge production. Funding and the structure of university research. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Geuna, A., & Muscio, A. (2009). The governance of university knowledge transfer: A critical review of the literature. Minerva, 47, 93–114.

Gibbons, M., Limoges, C., Nowotny, H., Schwartzman, S., Scott, P., & Trow, M. (1994). The new production of knowledge: The dynamics of science and research in contemporary societies. London: Sage Publications.

Gulbrandsen, M., & Slipersæter, S. (2007). The third mission and the entrepreneurial university model. In A. Bonaccorsi & C. Daraio (Ed.), Universities and strategic knowledge creation. Specialization and performance in Europe (pp. 112–43). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Heckman, J. (1979). Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica, 47(1), 153–161.

Hill, R. C., Griffiths, W. E., & Lim, G. C. (2011). Principles of econometrics. USA: Wiley.

IPI—Istituto per la Promozione Industriale. (2005). Indagine sui centri per l’innovazione e il trasferimento tecnologico in Italia, a cura del Dipartimento Centri e Reti Italia, Direzione Trasferimento di Conoscenza e Innovazione, Novembre, Roma.

Lee, Y. S. (2000). The sustainability of university-industry research collaboration: An empirical assessment. Journal of Technology Transfer, 25, 111–133.

Mansfield, E. (1995). Academic research underlying industrial innovation: Sources, characteristics, and financing. Review of Economics and Statistics, 77, 55–65.

Mansfield, E. (1998). Academic research and industrial innovation: An update of empirical findings. Research Policy, 26, 773–776.

Marsili, O., & Verspagen, B. (2002). Technology and the dynamics of industrial structure: An Empirical mapping of Dutch manufacturing. Industrial and Corporate Change, 11, 791–815.

Merton, R. (1973). The sociology of science. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Meyer-Krahmer, F., & Schmoch, U. (1998). Science-based technologies: University–industry interactions in four fields. Research Policy, 27, 835–851.

MIUR—Ministero dell’Università e della Ricerca. (2007). CIVR, Comitato per la Valutazione della Ricerca, VTR 2001–2003 Relazione Finale, Roma.

Muscio, A. (2010). What drives the university access to technology transfer offices? Evidence from Italy. Journal of Technology Transfer, 35, 181–202.

Nooteboom, B., Van Haverbeke, W., Duysters, G., Gilsing, V., & van den Oord, A. (2007). Optimal cognitive distance and absorptive capacity. Research Policy, 36, 1016–1034.

Piccaluga, A., & Balderi, C. (2006). La Valorizzazione della Ricerca nelle Universita` Italiane. NetVal, CRUI, ProTon Europe: Quarto Rapporto Annuale.

Powell, W. W., & Owen-Smith, J. (1998). Universities and the market for intellectual property in the life sciences. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 17, 253–277.

Schartinger, D., Schibany, A., & Gassler, H. (2001). Interactive relations between universities and firms: Empirical evidence for Austria. Journal of Technology Transfer, 26, 255–268.

Slaughter, S., & Rhoades, G. (2004). Academic capitalism and the new economy. Markets, state, and higher education. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Thursby, J. G., & Thursby, M. C. (2003). Industry/university licensing: Characteristics, concerns and issues from the perspective of the buyer. Journal of Technology Transfer, 28, 207–213.

Thursby, J. G., & Thursby, M. C. (2004). Are faculty critical? Their role in university-industry licensing. Contemporary Economic Policy, 22, 162–178.

Thursby, J. G., & Thursby, M. C. (2007). Patterns of research and licensing activity of science and engineering faculty. In P. E. Stephan & R. G. Ehrenberg (Eds.), Science and the university (pp. 77–93). Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Thursby, M. C., Thursby, J. G., & Gupta-Mukherjee, S. (2007). Are there real effects of licensing on academic research? A life cycle view. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 63, 577–598.

Von Hippel, E. (2005). Democratizing innovation. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Acknowledgments

This work benefited from valuable comments from Alan Hughes, Georg Licht, Francesco Lissoni, Gianluca Nardone, Markus Perkmann, Antonio Stasi, Giovanna Vallanti and two anonymous referees. The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support of the Italian Ministry of University and Research (FIRB Project 2003—Prot. RBNE033K2R: ‘A multidimensional approach to technology transfer for more efficient organizational models’).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Muscio, A., Pozzali, A. The effects of cognitive distance in university-industry collaborations: some evidence from Italian universities. J Technol Transf 38, 486–508 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-012-9262-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-012-9262-y