Abstract

Research has devoted substantial attention to patterns of offending during the transition to early adulthood. While changes in offending rates are extensively researched, considerably less attention is devoted to shifts in the type of offending displayed during the transition to adulthood. Changes in the type of offending behavior suggest a pattern of “displacement” or shifts between various types of crime, rather than desistance from deviant behavior. In this paper, I integrate methods previously developed in stratification research and use longitudinal data from the National Survey of Youth that span the transition to adulthood to examine the extent to which desistance and displacement of deviant behavior are defining attributes of offending during the transition to early adulthood. The findings indicate that while desistance is clearly present, altering patterns of offending, or within-person displacement, rather than termination of illicit activity is most evident in the data.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The transition to adulthood is among the most researched aspects of the life course. Of particular interest are patterns of illicit and normative behavior from adolescence to adulthood. Influenced heavily by the work of Sampson and Laub (1993), scholarship on desistance is increasingly central in both academic and policy debates. This paper adds to recent work on offending behavior over the life course by advancing a conceptual model of offending that emphasizes movement away from some types of crime and movement toward others as youth progress to early adulthood, a process termed within person displacement. Footnote 1 In this paper I examine the extent of both desistance and displacement during the transition to early adulthood. By integrating methods previously used in stratification research, this paper contributes to an understanding of patterns of criminal behavior as individuals move from adolescence to adulthood.

Desistance or Displacement: Offending Patterns During the Transition to Adulthood

Prior empirical and theoretical work suggests the importance of displacement. Gottfredson and Hirschi, for example, contend that cessation from anti-social behavior is unlikely for individuals with low self-control (1990). They argue that as individuals age, their offending manifests into problematic behavior in other areas, such as poor work habits, gambling, and substance use. Others, for instance Moffitt (1993), anticipates desistance among most individuals but persistence in a range of criminal or anti-social behaviors. Again the specific problematic behavior changes with age, which is consistent with notions of displacement. Such theories suggests a process of criminal displacement and establish a foundation for developing models positing that individuals may cease some anti-social behaviors and initiate others as they transition to adulthood.

Empirically, both contemporary and classic work in criminology suggests that criminal displacement is a phenomenon of the transition to adulthood. For example, Steffensmeier et al. (1989) examines aggregate shifts in the age distribution of criminal behavior, finding some crimes characteristic of youth while others are more likely to occur later in life. More specifically crimes such as vandalism are associated with youth, while illicit gambling is more characteristic of adulthood.

Earlier work by Glueck and Glueck (1968) used the term “delayed maturation” to describe an aging process by which some individuals do not entirely desist from crime, but rather move away from more serious crime and initiate or continue lesser offenses such as drunkenness or offenses against the family (1968, p. 151). In other work, Glueck and Glueck (1940) they identify individuals who do not fully move away from crime but rather “....lapsed into those forms of anti-social behavior which require less and less energy, planfulness, and daring, such as drunkenness and vagrancy” (1940, p. 106). Shaw’s classic ethnography The Jack-Roller (1966) also alludes to displacement. As Stanley, the subject of the Jack-Roller, is slowly leaving violent crime, he continued to gamble, drink, and frequent “houses of ill-fame” (Shaw 1966, p. 121). Footnote 2 Recent ethnographic work also supports notions of displacement. For example, Shover’s interviews with thieves reveals a process by which individuals shift from crimes characterized by their highly visible and confrontational nature to less risky behavior (1966, p. 129).

Consistent with ideas of displacement, Cohen (1986) identifies patterns of “switching” or changes in the behaviors of arrested individuals. Other work uses the term “aggravation” to refer to a developmental sequence of diverse types of delinquent acts (Loeber and LeBlanc 1990, p. 382). More recently, work focuses on aggregate changes in typologies of offending at different points in the life course (Francis et al. 2004). Underlying all of these works is the notion that individuals modify both their rate and their type of offending as they age.

Displacement is not the initiation of criminal behavior later in the life course, often called “late onset” (for instance Fergusson et al. 2000), nor the cessation or significant decline in criminal activity characteristic of desistance. Rather, displacement is characterized by changes in criminal behavior over time. As such, displacement also differs from heterotypic continuity in that displacement suggests individuals engage in qualitatively different acts as they age, for instance moving from violence to drug use. In contrast, heterotypic continuity is characterized by the different manifestations of the same behavior, for instance violent behavior manifested as kicking and hitting in early youth, which becomes gang fighting teenage years (Nagin and Trembley 2001). While heterotypic continuity and desistance have been heavily researched, displacement has received far less attention as a potential characteristic of offending during the transition to adulthood.

The idea of criminal displacement suggests that qualitative shifts in offending patterns occur over the life course. For instance, as individuals become adults, do some shift their offending from violent acts toward increased drug use? Or, do they cease violent crime and not initiate any other type of illegal behavior? Movement from violence to substance use suggests a shifting or displacement of behavior, while ceasing violent crime without initiation of other crimes is evidence of desistance. Researching shifts in offending patterns extends recent work on offending trajectories by examining the extent to which movement into and away from different and distinct illicit acts is a feature of the transition to adulthood. Properly examining such behavioral changes necessitates models and measures that capture shifts in and out of different behaviors.

Methodological Considerations in Modeling Displacement

Despite advances in understanding factors that influence desistance (Sampson and Laub 1990; Maruna 2000; Uggen 2000) researchers continually wrestle with appropriate conceptual, operational, and methodological approaches to studying desistance. This results in substantial variation in both the measurement and methods used to research desistance. Brame et al. (2003) summarize work in the area and conclude that approximate desistance models, often referred to as trajectory models, are now the dominant methods used to study desistance (see for instance, Laub et al. 1998). While methodologically sophisticated, these models are based on offense frequencies, predominantly counts of a single measure, such as arrests, or a single summed measured of delinquency. Footnote 3 The model then groups individuals into latent categories based on their offending rate or trajectory. While the propensity to offend is accounted for in the model, generally, individuals will have increased offending trajectories if their number of crimes or arrests increases in a time period; as their number of crimes or police contacts decreases, their trajectory will decline accordingly. While recent work differentiates between violent and non-violent trajectories (Piquero et al. 2002a), in general trajectory approaches have not tested for displacement.

While trajectory models have many strengths, two related points warrant further discussion and investigation. First, as commonly used, trajectory models group individuals into latent offending categories and examine changes over time in the offending trajectory of a specific category of individuals (for example, Laub et al. 1998). Second, these models capture whether individuals do more or less of a specific type of crime or a single summed indicator capturing an index of crimes. As a consequence of these two features, movement in and out of various crimes over time, or shifts to different behaviors captured in a summed indicator is not detectable.

This means important changes in offending behavior may be masked. Consider an individual who is arrested five times for alcohol possession at age 18 and five times for violence at age 25. Because the rate of offending is the same at both times, this shift in the type of criminal act committed is undetected by models emphasizing the trajectory of offending rates. The inability to capture shifts in offending is more pronounced the greater number of crimes summed together. For instance, Bushway et al. (2003) study desistance using a broad crime of index of 31 different offending indicators. With such a comprehensive measure, a declining trajectory indicates movement away from crime, and the model would aptly capture desistance. However, any shifts in criminal behavior, or displacement, are left undetected using such a broad index of crime. Stated differently, when using trajectory models and a broad offending index, gleaning any crime-specific changes, changes alluded to in prior empirical and theoretical work, from the larger trajectory is difficult.

By modeling both displacement and desistance, the methodology in this paper departs from dominant methods of studying offending patterns (see e.g. Laub et al. 1998; McDermott and Nagin 2001). The models used complement trajectory models, as both are latent class models that highlight aspects of offending behavior over time. Substantively, the key departure centers on how behavior is modeled. Trajectory models excel at highlighting the rates of offending over time, and thus changes in those rates. More recent work has begun to develop group based methods to link membership in the trajectories of related behaviors (Nagin and Trembley 2001; Piquero et al. 2002a). Again, however, the emphasis of such methods is to examine changes in the rates of offending.

In contrast, this paper extends methods previously developed to study social mobility and related social processes to patterns of deviant behavior (Clogg and Shihadeh 1994; Eliason 1993; Yamaguchi 1987). These methods allow for an examination of criminal activity over time by focusing on the relationship among different patterns or types of offending behaviors. In doing so, they build upon recent methodological developments by modeling offense-specific movement into and out of multiple behaviors.

More specifically, in both adolescence and adulthood, the models used in this analysis first group individuals into distinct offending categories based on multiple behaviors, and then examine stability or movement across offending categories from adolescence to adulthood. To do so, I use latent class analysis to model behavior as qualitatively unique offending patterns, captured by differing probabilities of participating in any of six measures of crime, in both adolescence and early adulthood. I then use row by column association models estimated from transition tables to examine movement across these distinct offending patterns over time. This allows for conclusions about desistance, displacement, and stability of crime to be based on; (a) aggregate shits over time in the number of individuals displaying a given criminal offending pattern, (b) offense specific behavioral estimates, in both adolescence and adulthood, that represent an individuals probability of being involved in a variety of crimes, (c) and changes in individual offending patterns over time.

Data and Measures

The data used in this research are taken from waves one and seven of the National Youth Survey (NYS). The NYS is a national probability sample of households in the continental United States, based on a multistage, cluster sampling design (Elliott et al. 1985). The NYS is widely used in criminological research (Elliot et al. 1989; Jang and Johnson 2001; Heimer and Matsueda 1994; Matsueda 1992; McDermott and Nagin 2001; Warr 1998). The first wave of the sample is comprised of 1,725 adolescents between the ages of 11 and 17. Respondent attrition across the seven waves is relatively low: 82% of the original sample is retained through 1983, when respondents were between the ages of 21–27 (Elliott et al. 1985). Footnote 4 This analysis uses all individuals who answered the survey in early adulthood, 1,383 respondents. Other research finds that this period in the life course is marked by significant movement away from crime (D’Unger et al. 1998; Hirschi and Gottfredson 1983; McDermott and Nagin 2001; Piquero et al. 2002a; Uggen 2000).

I use measures of crime from adolescence and early adulthood. In adolescence, respondents were asked about their involvement in a range of criminal and antisocial behavior, including theft, violence, vandalism, marijuana use, hard drug use, and general deviance. Involvement was based on prevalence with offenders coded 1. Unlike most trajectory work, the dependent variables are not summed indicators, but rather variety scores capturing offense-specific involvement in any of the measured indicators. Other research takes a similar approach, using multiple dichotomous indicators, also called diversity scores, to examine reported delinquency and violence (e. g. Felson and Haynie 2002, p. 971; Piliavin et al. 1986, p. 105; Moffitt et al. 2000, p. 210; Silver 2000, p. 1055; Wright et al. 1999, p. 181; Wright et al. 2001, p. 330).

Also consistent with other studies (Fergusson et al. 2000), in some instances I collapsed multiple indicators into one binary indicator measuring involvement in a domain of behavior. For example, in adolescence, vandalism at school, home, or in other locations is collapsed into a single indicator of involvement in vandalism. This is done to minimize potential false negatives by capturing the multiple venues in which individuals could commit illegal or antisocial acts. It also incorporates the changing life structure associated with aging. By utilizing multiple indicators, I craft substantively similar, yet age-appropriate offending measures. Thus when creating offending indicators in adulthood, I substitute indicators of workplace vandalism, violence, and theft for adolescent measures of school vandalism, violence, and theft. Capturing a range of behaviors and using age-graded, or age-appropriate offending measures is consistent with research on the reliability of self-report data (Hindelang et al. 1981; Piquero et al. 2002b).

The general deviance indicator is included to examine the theoretical claims of Gottfredson and Hirschi (1990), and the empirical findings of Glueck and Glueck (1968). Both works assert that some individuals will display continued deviance across the life span. More recent work also demonstrates the importance of behaviors analogous to crime (Paternoster and Brame 1998, 2000). The general deviance indictor taps behavior analogous to offending that can be seen as deviant or anti-social, although it may or may not be prohibited by law, such as binge drinking. Despite its theoretical and substantive relevance, desistance researchers have largely neglected forms of anti-social behavior analogous to criminal offending. Accordingly, the indicator is intended to capture problematic behavior that might not attract or warrant an official criminal justice response.

In all, six variables represent individual involvement in vandalism, theft, violence, minor and serious drug use, and general deviance. These measures capture offending behavior during two distinct periods of life, late adolescence and early adulthood, marked by a series of life-course transitions. See Appendix 1 for a more detailed discussion on the measures used in the analysis. Footnote 5

Methods

To empirically examine desistance and displacement during the transition to adulthood, I model multiple types of behaviors simultaneously using latent class analysis, transition tables, and row by column (RC) association models. In both adolescence and adulthood, latent class analysis estimates qualitatively distinct latent offending patterns from the observed measures. These distinct patterns are represented by variation in offense specific estimates that represent the probability of abstention or involvement in each offending behavior. The latent class models also estimate the percentage of the overall population that is likely to be in each offending group. These latent classes and their corresponding offending probabilities serve as the basis for examining offending patterns at different life stages.

The second phase of analysis advances prior work (Francis et al. 2004) by statistically linking offending patterns over time. Transition tables and association models examine stability and change in latent offending patterns from adolescence to adulthood. The transition table captures whether individuals move or remain stable in their latent classification over time. RC association models test whether movement across different offending patterns is statistically significant and depict the relationship between latent classification in adolescence and early adulthood. Relationships are depicted in terms of distances that estimate the degree to which criminal behavior is stable or changes over time. Formal tests assess whether these distances, and the corresponding behavior modification, is statistically significant. In sum, this analytic approach specifically tests for patterns of desistance or displacement.

With both methods, during model construction, no distribution assumptions are imposed on the data. The models are based on the observed distribution of the data. For example, when estimating the latent class models, no assumptions were imposed to determine whether the data best support a model with 1, 2, 3, and so on, classes. When estimating the parameters for the preferred model, however, full information ML estimators (Eliason 1993) are used and the data is assumed to multinomial distributed, which is closely related to the Poisson distribution commonly used in work on offending trajectories.

The Categorical Data Analysis System (CDAS) 4.0 is used to estimate the latent class and RC association models (Eliason 1997). For more information on the algorithms used by CDAS to estimate the association or latent class models, see Clogg (1977), Becker (1990) or Eliason (1995). For more information on how RC association models are applied in the context of stratification research, see Clogg et al. (1990) or Clogg et al. (2002).

Latent Class Analysis

In latent class analysis, a latent variable is defined as an unobserved construct that accounts for the relationship among a set of observed measures (Clogg 1995). In this specific analysis, the observed variables measure involvement in vandalism, hard drug use marijuana use, theft, general deviance, and violence. Latent class analysis uses associations among the offending measures to create a latent variable with T categories, each representing a distinct pattern of offending. Footnote 6 A key assumption of these models, the constitutional independence assumption, states that the observed variables are independent given the latent variable (Clogg 1995). The model estimates the conditional probability that an individual would fall within a latent class, in this case an offending type, given the observed offending characteristics of that individual.

More formally, let A represent vandalism, B hard drug use, C marijuana use, D theft, E general deviance, F violence, and X a categorical variable capturing latent offending classification. Using common notation (Clogg 1995; Goodman 1987; McCutcheon 1987), these models take the following form:

where π {AB\ldots FX ij... nt is the joint probability that an individual will fall in cell i, j, ... n t. In this analysis, cells i, j, ... n represent different patterns of involvement in the six observed offending measures and t represents the latent offending class or type. Working through the right side of the equation and applying the notation to the specific analysis in this paper: \(\pi_{it}^{\rm {\overline{A}X}}\) is the conditional probability of being involved in vandalism, given latent offending class t of latent variable X; \(\pi_{it}^{\rm {\overline{B}X}}\) is the conditional probability of being involved in hard drug use, given latent offending class t. In this analysis, there are six observed variables, accordingly the notation is extended to included the four remaining observed behaviors: marijuana use, theft, general deviance, and violence. The notation π X t represents the probability that any one individual can be found in latent offending class t, and can further be interpreted as the proportion of latent offending class t individuals in the population.

Latent class models test for qualitatively distinct offending patterns in adolescence and early adulthood. Because these patterns are based on the type of crime committed, movement across latent classes over time can represent either desistance or displacement, depending on the behavioral characteristics associated with each latent offending group. This is fundamental step toward examining whether individuals shift or displace their behavior as opposed to simply engaging in more or less of the same behaviors. After discussing the results of the latent class models, I consider movement over time with transition tables and RC association models.

Results

Latent Class Models: Behavioral Probabilities

In both adolescence and adulthood, fit statistics indicate that the data best support a model with four unique offending patterns. Footnote 7 As shown in Table 1, in adolescence the largest latent class has sporadic deviance that could largely be considered normative. This group comprises approximately 55% of the overall population and is characterized by a low to moderate probability of involvement in violence and general deviance (approximately 0.25). Individuals in this group have approximately a 0.12 probability of involvement in vandalism, and are unlikely to be involved in theft or any drug use. The behavioral probabilities of the normative class suggest that abstaining from some types of crime is a common phenomenon for many adolescents. Footnote 8

The second class characterizes approximately 27% of the population. Here delinquency is more comprehensive, yet but the defining feature of the second latent class is the predatory nature of their illicit acts. Relative to individuals in the normative class, individuals in this “predatory class” are approximately six times more likely to be involved in vandalism, 11 times more likely to be involved in theft, and almost three times more likely to commit acts of violence. For all three crimes, the increased probabilities are statistically significant. Footnote 9

Comprising 11% of the population, latent class three shows significant illicit drug use. Individuals in this “drug class” have a 0.20 chance of being involved in hard drug use and a 0.83 probability of marijuana use. These individuals are also differentiated by the illicit acts they are unlikely to commit. Relative to respondents captured in the predatory class, individuals in the drug class are approximately two to six times less likely to participate in vandalism, theft, and violence than their peers in the predatory class. These differences are again statistically significant.

The fourth and smallest class, termed the “pervasive class,” demonstrates a high probability of involvement in all types of illegal behavior. For example, individuals in the pervasive class are twice as likely as those in the drug class to be involved in hard drug use. Their probability of being involved in violence is 0.84, and above 0.9 for all other acts. Approximately 7% of the overall population is likely to exhibit the behavioral pattern characteristic of the pervasive class.

Having presented behavioral patterns in adolescence, Table 2 shows the conditional probability of offending in early adulthood. Again there is evidence of a “normative group” comprising slightly less than half of the overall population. In adulthood this group shows very low probability of involvement in illicit activities. While individuals in the normative group are moderately (0.2) likely to be involved in general deviance, they demonstrate almost no involvement in any other type of crime.

As with adolescence, a predatory category emerges comprising almost 25% of the population. Again, the predatory class demonstrates a significantly greater likelihood of involvement in violence (0.17), theft (0.25), and vandalism (0.09) than individuals captured in the normative class. Footnote 10 Consistent with analysis of youth, individuals in the predatory class are unlikely to be involved in substance use (hard drug 0.09, marijuana use 0.22) and are likely to be involved in general deviance (0.79).

In early adulthood, the drug class comprises approximately 22% of the overall population. Individuals captured in this latent category have a 0.98 probability of marijuana use and a 0.53 probability of hard drug use. Similar to the latent structure of adolescent offending, individuals in the drug class are significantly less likely to be involved in theft, violence, and vandalism than their peers in the predatory class. The drug class also has a high probability of involvement in general deviance (0.81).

As with adolescence, the final latent class in adulthood is the “pervasive class” which again shows substantial involvement across all indicators. Capturing approximately 6% of the overall population, individuals in the pervasive group have a high probability of involvement across all indicators. While tests for statistical significance (see footnote 7) revealed no differences in marijuana use between the drug and pervasive group in early adulthood, pervasive offenders are significantly more likely to engage in all other crimes relative to all other offending groups.

In sum, the results from the latent class analysis in early adulthood are generally consistent with those for the adolescent period. Four offending patterns emerge and the anti-social behavior of individuals in these classes can be described as normative, predatory, pervasive, or focused on substance use.

Before moving to an analysis of changes in offending patterns as individuals transition to adulthood, some general descriptive points on the latent class analysis and the overall distribution of delinquency warrant discussion. A pattern of population level desistance from crime is evident in the latent class analysis. At both time points the normative class is the least delinquent. In adolescence, the group is approximately 55% of the population, and in early adulthood, the normative group is approximately 48% of the population. However in adolescence, the normative group is characterized by moderate probabilistic involvement (ranging from 0.12 to 0.29) in vandalism, theft, and general deviance. In adulthood, individuals in the normative group show moderate involvement in only general deviance. Consistent with the general trend away from antisocial behavior characteristic of the transition to adulthood, as captured by the behavioral probabilities of the latent class models, the normative group in adulthood demonstrates less probabilistic involvement in illicit acts than the normative group in adolescence. Stated differently, “normative” behavior in adulthood is less deviant than “normative” behavior in adolescence.

The pattern of desistance is best illustrated by three crimes, violence, theft, and vandalism. While these crimes are widespread in youth, they are a small part of the behavioral repertoire of early adulthood. In adulthood, these acts are not prevalent among either the normative or the drug classes. Even among the predatory group, the probability of involvement in violence, theft, and vandalism decreases dramatically from adolescent levels. While the delinquent profile of this group is still defined by its predatory nature, individuals are two times less likely to be involved in theft, four times less likely to be involved in violence, and seven times less likely to be involved in vandalism than in youth, in all cases this represents a statistically significant decrease in behavior. Footnote 11 Thus, a shift away from predatory crimes occurs as youth transition to adulthood. Such movement is part of the overall trend toward desistance evident in some respondents.

Secondly, even in the presence of offense-specific desistance, drug use increases as youth transition to early adulthood. In fact, for all groups the probability of drug use increases. Furthermore, for individuals in the drug class, the probability of use is significantly higher in early adulthood then in adolescence. Additionally, the size of the drug class has doubled from adolescence to early adulthood. Thus, as youth transition into early adulthood, there is evidence of movement into substance use. Although substance-specific variation exists, this finding is generally consistent with other studies that find rates of substance use peak in the early to mid-twenties (Bachman et al. 1997, p. 80, 113, 136). This peak is evident for both men and women, and is attributed to the new freedoms accompanying the first years of adulthood (Bachman et al. 1997). Footnote 12

Finally, the inclusion of a general deviance indicator captures meaningful antisocial behavior in both adolescence and early adulthood. In both adolescence and early adulthood, even the most normative behavioral patterns demonstrate a moderately high probability of being involved in general deviance relative to other measured behaviors. This suggests that while most people are unlikely to participate in acts such as violence, theft, and vandalism, even the most conforming class of individuals still demonstrates a modest probability (0.20) of behavioral problems. Among other groups, at both time points, the probability of participation in general deviance is high, both in absolute terms and relative to other illegal acts.

By developing models that account for behavior across different youth and adult domains, and by modeling multiple acts simultaneously, the latent class analysis offers two basic insights. First, its shows evidence of a shift away from predatory crimes into crimes of substance use. Second, the latent class analysis shows how general deviance, co-varies with other illicit behavior, and is present among even the most conforming group of individuals. In sum, this portion of the analysis shows aggregate shifts away from some crimes, and movement toward others as youth transition to adulthood.

Changes Over Time

I next consider the question of displacement or desistance as youth transition to early adulthood. To test for desistance and displacement, it is necessary to statistically connect the latent class analysis to behavior over time. This is done with transition tables and RC association models. Table 3 shows the cross-classification of the adolescent and adult latent offending patterns and serves as the basis for subsequent analysis using RC association models. Footnote 13 The observed associations in Table 3 can be seen as arising from the latent transition structure linking adolescent and adult offending typologies. From that, the likelihood that a specific individual will make a specific transition from one offending pattern in adolescence to another offending pattern in adulthood may be viewed as in part governed by this latent transition structure. I first present the transition table for these data, followed by results from the RC association model. I then discuss the substantive implications from this analysis.

Transition Table

Because the behavioral probabilities associated with latent classification in adolescence and adulthood differ, stable latent assignment, captured by the diagonal axis in the transition table, does not indicate absolute behavioral stability. However, the diagonal axis suggests stability relative to others in the sample. Additionally, because the offending indicators are adjusted for the differing life stages that accompany ageing, the diagonal axis also captures stability in age specific offending. Accordingly, the 437 (row 1, column 1) individuals captured in the normative class (and the 100 in the latent predatory class, row 2 column 2, and so on) demonstrate relative behavioral stability. At both points in time, these individuals are least likely to be involved in crime. This pattern of relative behavioral stability is evident in over 43% of the population, making it largest group in the sample. Footnote 14 The stability of behavior is one of the most consistent findings in criminological and life course research (see for instance Gottfredson and Hirschi 1990), and the present research is consistent with past work showing general behavioral continuity over time.

In this paper desistance or movement away from crime is defined by two behavioral patterns: (1) individuals who are in the normative class in adulthood and were in some other class during adolescence; or (2) individuals who were in the pervasive class in adolescence and any other class in adulthood. These two patterns of movement clearly indicate a lower probability of criminal involvement in early adulthood than in adolescence, both in absolute probabilities and relative to other respondents in the sample. Representing approximately 22% of the sample, 307 individuals had offending patterns that fit either criterion. The majority of these individuals (155, row 2 column 1) were classified as predatory in adolescence and normative in early adulthood. For these individuals, their youth is characterized by vandalism, theft, and violence, behaviors unlikely to extend to adulthood. The second largest group of movers are individuals (62, row 3 column 1) who in adolescence were characterized by a relatively high probability of drug use, but their behavior in early adulthood is normative. Consistent with other work, movement away from crime is evident (Sampson and Laub 1993).

In addition to both stability and movement away from crime, there is also some evidence of criminal escalation in the data. Escalation is defined as: (1) individuals who were in the normative class in adolescence and in any other latent category in adulthood; or, (2) individuals who were in the pervasive class in early adulthood and in any other latent category in adolescence. The movement occurs along three tracks. One track involves the 177 youth (row 1 column 2) who move from the normative class to the predatory class. The second track involves the 120 people (row 1 column 3) who moved into the drug class from the normative class. These individuals show a significant increase in the probability of substance use. Lastly, the 64 individuals who moved into the pervasive class in adulthood from some other latent class in adolescence demonstrate significant escalation of multiple types of deviance. The transition table suggests that some people move into crime during early adulthood, and drug use is a defining feature of their illicit behavior.

While the transition table shows patterns of escalation and desistance during the transition to adulthood, there is strong support for the notion of criminal displacement. Evidence of displacement is found in close to 40% of the overall sample. Considering first individuals who move away from crime, 70 (row 4, column 2 and 3) move from the pervasive group in adolescence to either the predatory or the drug group in adulthood. Thus, while they clearly moved away from crime, they did not cease criminal activity. Rather their offending patterns were characterized by shifting of behavior, most likely into some type of substance use.

Evidence of displacement is also prominent in other cells in the transition table. For example, 85 individuals (row 2 column 3) have patterns of criminal behavior that shifted from predatory to drug offending. Even among those who escalate criminal behavior, displacement is evident. For the 120 individuals (row 1 column 3) moving from the normative class in adolescence to the drug class in early adulthood, their adolescent involvement in vandalism and theft is displaced by involvement with drugs. Similar patterns of displacement occur for the 177 (row 1 column 2) individuals whose moderate probability of violence is displaced by a moderate probability of marijuana use.

There are cases where patterns of displacement and desistance are consistent with each other. For instance, individuals who move from a normative classification in youth to a predatory pattern in adulthood shift both their offending type and moderate their probability of vandalism. Such findings again underscore the general movement away from crime for many individuals as they transition to adulthood. As a further example, the behavioral probabilities associated with stable assignment in both the predatory and normative latent classes suggest less probabilistic criminal behavior. Consistent with other work, desistance is evident, even as individuals shift in and out of various types of crime.

While desistance, escalation, and stability are all evident, displacement of offending appears to be an important, yet understudied, feature of the transition to early adulthood. Once involved in crime, most individuals do not move completely away from crime, rather they tend to shift their offending toward qualitatively different, but still problematic behavioral. To better understand these patterns, this analysis employs RC association models.

Row by Column (RC) Association Models

In this analysis RC association models provide a method to test the associations evident in the transition table (Goodman 1987). As used here, RC association models have two important features. First, they examine the relative distance between patterns of offending, for instance drug classification in adolescence and predatory classification in adulthood, as measured by the behavioral probabilities associated with various latent classes. The cumulative effect of this process is to assess the overall relationship between offending in youth and early adulthood. Second, RC association models allow for a formal test of which patterns of behavior in adulthood are most associated with patterns of criminal and anti-social behavior in adolescence, as well as assess whether moving from one offending pattern in adolescence to another in adulthood represents a significant change in behavior.

RC association models, therefore offer a method to examine the association between the latent adolescent typology of offending, the rows of Table 3, and the latent typology of offending in early adulthood, the columns of Table 3. RC association models are particularly useful when there is partial, although not necessarily explicit, ordering to a variable (for other empirical examples see, Clogg et al. 1990; Eliason 1995; Goodman 1987. For a general presentation of RC models, see Clogg and Shihadeh 1994). Footnote 15 Goodness-of-fit tests determine the proper model specification for the relationship between adolescent and adult offending. When properly specified, the model parameters represent the relationship among patterns of offending in youth and early adulthood.

RC association models take the following form (Clogg et al. 1990):

where F ij represents the expected frequency in cell (i, j) of a two way cross-classification table, in this case the cross-classification of latent offending in adolescence with latent offending in adulthood. Again, rows refer to adolescent offending patterns, and columns refer to adult offending patterns. The η,α i , β j parameters are necessary to fit the overall sample size, the row marginal distribution, and the column marginal distribution, respectively, and are not related to the substantive questions addressed in this paper. The μ parameters represent the scale scores for adolescent offending patterns, and the ν parameters represent the scale scores for the adult offending patterns. Thus, ν mj is the scale value on the mth dimension for column category j and the μmi is the scale value the mth dimension for row category i. ϕ m is the intrinsic association between the row and columns on the mth dimension.

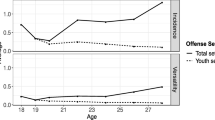

In this analysis the intrinsic association tests the relationship between latent classification in youth and latent classification in adulthood. A non-significant intrinsic association indicates no association between offending in adolescence and adulthood. In RC association models, the dimension refers to scaling of the joint distribution of the variable. In situations where a one dimensional representation of the joint distribution is supported by the data, treating the categories as ordered is appropriate (see Goodman 1987). Footnote 16 Thus, in this analysis the RC models serve as a statistical tool to assess general stability and change in behavior over time, as well as assess the relationship between specific offending types over time. I use the RC analysis to empirically represent the relationship between adolescent offending and early adult offending and to test whether movement between latent classes during the transition to adulthood represents a statistically significant change in behavior. The preferred model fit statistics and parameter estimates with standard errors are presented in Table 4. The fit statistics show a significant association between latent class membership in adolescence and latent class membership in adulthood that is best represented as a one dimensional solution, shown in Fig. 1. Footnote 17

Closer grouping of the estimates from the RC association model indicates a stronger association of behavioral patterns in adolescence and adulthood. As shown in Fig. 1, membership in the normative class in adulthood is most closely related to membership in the normative class in adolescence and membership in the pervasive class in adulthood is most strongly associated with membership in the pervasive class in adolescence.

Additionally, Fig. 1 is scaled such that higher scores indicate more normative behavior. Thus, with the exception of the drug class, the movement away from crime, or aggregate level desistance, is evident. Compared to the adolescent normative group, individuals classified as normative in adulthood exhibit less anti-social behavior, and in adulthood the predatory group exhibits less probabilistic involvement in crime than the predatory group in adolescence.

Contrary to pure desistance explanations however, the RC association model supports the notion of within-person displacement rather than strict behavioral desistance. The RC association models would be more suggestive of desistance if individuals in the normative class in adulthood were drawn from the adolescent predatory, drug, or pervasive class. Normative individuals in adulthood were, however, overwhelmingly likely to have been normative in adolescence.

Movement or lack of movement across different latent classes over time resonates with classic criminological debates on stability or change in criminal behavior. In RC association models, the phi parameter gives the intrinsic association between the rows and columns on a given dimension. In the present analysis, this parameter can be transformed into Yule’s Q. This transformation allows for a relatively straightforward assessment of the stability of latent class assignment, and by extension behavioral patterns over time. The formula for the transformation is:

where ϕ is the intrinsic association and Q is Yule’s Q, which is 0.58. While somewhat arbitrary, a Yule’s Q of 0.58 has been interpreted as evidence suggesting a moderate relationship (Bohrnstedt and Knoke 1994, p. 167) between origins (adolescent offending classification) and destinations (adult offending classifications).

As a further assessment of stability or change in the RC association model, the estimates of the variance-covariance matrix allow for specific tests of significance to be crafted between any two latent categories. Footnote 18 These tests of significant pairwise distances indicate that movement into the normative class in emerging adulthood is a significant move, meaning it is unlikely to occur relative to other transitions or stable classification, for individuals from the predatory, drug, and pervasive classes in youth. As with the transition table, there is little evidence suggestive of large scale desistance.

Taken in conjunction with offending measures that includes workplace deviance and illicit drug use, the RC association models are more suggestive of displacement and shifting of anti-social behavior. The results here support the notion of behavioral change, but not large scale desistance. Once a greater variety of anti-social activities and age-appropriate offending measures are considered and models are used to estimate crime specific involvement as part of a general pattern of behavior, displacement aptly characterizes offending patterns during the transition from adolescence to early adulthood.

Discussion

This work merges insights from classic research with more recent theoretical work on patterns of offending (Glueck and Gleuck 1940, 1968; Gottfredson and Hirschi 1990; Shaw 1966) to test whether criminal displacement is an aspect of the transition to adulthood. Using different methods, such work describes a process by which individuals move away from some crimes and initiate others as they age, a process I term criminal displacement. While rooted in enduring criminological work, research has not fully assessed whether offending displacement is a facet of the transition to early adulthood. Using longitudinal data on offending, I find strong evidence of criminal displacement.

A great deal of the research on offending patterns is based on the rate at which behavior occurs over time. While recognizing the utility of such an approach, the results here demonstrate the importance of simultaneously examining and estimating parameters for a multitude of behaviors to better understand changing offending patterns during the transition to adulthood. The application of latent class analysis and RC association models allow for both a general assessment of offending types and offense specific behavior when examining the transition to adulthood. While utilized in other substantive contexts this method has not been used in the study of criminal offending.

This analytic approach produces results consistent with existing research on desistance in many ways. For instance, I find that individuals move away from some behaviors as they transition from youth to adulthood (Piquero et al. 2002a; Shover 1993). This process, illustrated through a comparison of the behavioral probabilities of both the normative and predatory groups, shows clear decline across vandalism, violence, and theft.

The movement away from specific crimes is part of an overall pattern of desistance for some individuals. In general individuals in both the normative group and predatory in adulthood are less likely to be involved in crime than individuals classified as normative and predatory in adolescence. Additionally, almost 25% of the sample “moved down” in their latent classification over time, indicating less serious involvement in crime over time. Thus, some movement away from crime is evident in the latent class models and transition table.

Nevertheless, this analysis yields other conclusions that depart from prior work. At the most basic level, when considering a variety of behaviors, I find less movement away from crime than other work suggests (Laub et al. 1998; D’Under et al. 1998). Measures such as hard drug use, marijuana use, and general deviance reveal continued problematic behavior in adulthood. For instance, analyzing men and using the same data utilized in this analysis (NYS), but using a summary index of offending that does not include substance use or behaviors analogous to crime, McDermott and Nagin (2001, p. 295) find only one offending trajectory, consisting of 38 young men, that demonstrates substantial involvement in crime at age 23. When models take into account the initiation of these behaviors, movement away from crime is less pronounced, as some of what has previously been defined as desistance appears to be displacement. In finding significant evidence of displacement, this paper presents patterns of behavior that have received far less attention in the criminological literature on the transition to early adulthood.

More generally this finding demonstrates the need to craft offending measures that account for the changing opportunity structure of offending as individuals transition into different phases of the life course. Along similar lines, this analysis, particularly the latent class analysis, suggests that desistance researchers would be well served to generate simultaneous estimates for a variety of criminal acts, as the shift in and out of certain crimes is likely masked by broad summed outcome measures.

Part of that shift in and out of different types of crime is undoubtedly driven by opportunity. However, the analysis strongly suggests that research that does not account for drug use may exaggerate the prevalence of desistance. In doing so, this work builds upon prior research in the “trajectory” tradition, which also finds continued drug and substance use among some types of offenders (Nagin et al. 1995). The analysis presented here underscores the importance of separately measuring and generating estimates for substance use and general deviance, as well as crafting age-specific offending measures when attempting to reach general conclusions about desistance.

By creating models that produce estimates for each offending behavior over time, this work moves toward a more complete picture of behavior over the life course. The patterns of desistance and displacement found in this analysis highlight the importance of producing item specific estimates for a greater range of theoretically and substantively important behaviors. While not necessarily preferable to rate or frequency methods, the models proposed here aptly characterize the multitude of criminal behaviors characteristic of the transition to adulthood.

These behaviors patterns also reveal both consistencies and inconsistencies with notions of heterotypic continuity (Caspi 1998; Nagin and Tremblay 2001). To the extent that all criminal and antisocial behavior can be seen as a manifestation of the same general trait, the likelihood of some individuals to continue antisocial and criminal acts into early adulthood represents a continuity of behavior.

There are however, significant departures from the behavior expected under a heterotypic continuity explanation. Using the example of an individual who bites during childhood, is involved in gang fights during adolescence, and abuses a spouse during adulthood, Nagin and Tremblay note “the form and target of the aggression is different but the constant is the physical violence” (2001, p. 18). Consistent with these ideas, this analysis modified indicators of violence, theft, and vandalism, to allow the form and target of such crimes to vary while incorporating the different life circumstances that accompany aging. Yet, the likelihood of these crimes occurring still decreases precipitously. This suggests that individuals are much more likely to shift their behavior towards different types of criminal acts rather than to display different manifestations of the same general acts. Thus, while the most serious (and conforming) offenders in youth are the most serious (and conforming) offenders in adulthood, their behavior changes in significant ways. In particular, they move away from such acts as violence and vandalism, and display more drug use during the transition to early adulthood.

By modeling offending behavior using latent class models, transition tables, and RC association models, the results of all three methods strongly support the notion of a shifting of behaviors rather than a pure desistance pattern. This is not to suggest that desistance does not occur. However, the analysis fails to reveal the aggregate movement into the normative class that much research suggests should occur during this period. To be sure, over time, almost all individuals eventually desist from crime (Laub and Sampson 2003), but the analysis presented here indicates that the displacement of criminal activity is an important aspect of offending during the transition to early adulthood.

Conclusion

The core findings in this paper can be summarized in two points. First, I find four qualitatively distinct patterns of offending in both adolescence and adulthood. These distinct patterns are represented by unique parameter estimates representing the probability of involvement in any of the different measures of criminal offending. Second by capturing movement in and out of six different types of illicit and anti-social behavior over time, I find most individuals move away from violent crime, but do not completely desist. Rather they initiate or continue various forms of substance use. Accordingly, displacement of offending, rather than desistance best characterizes the observed patterns.

Before concluding, it is important to address potential weaknesses of this paper and areas for future research. The standard criticisms of self-report data apply to this work (Lauristen 1998). Furthermore, this research employs data at two time points; further development of the methods and empirical results presented in this paper using multiple data points may provide additional insight into patterns of criminal behavior over the life course. Along similar lines this analysis explores aggregate trends in criminal behavior. Future work could consider age or gender specific-shifts in behavior. Additionally, research could explore factors that help understand initial placement in different adolescent offending classes. Finally, it is unclear how sample attrition may impact the inferences drawn from criminological research (Brame and Paternoster 2003; Brame and Piquero 2003). If individuals with certain behavioral preferences are more likely to drop out of the sample, what appears to be offense or group specific desistance may in fact be sample attrition. Research has only recently begun to address this issue.

This work is a step towards developing models that treat offending and desistance as a process, as advocated in recent work (Bushway et al. 2001). This paper models change and stability in both the likelihood of offense-specific criminal involvement, as well as change or stability in different types of offending patterns over time. By applying models that estimate multiple behaviors simultaneously and map out associations between behavioral types at multiple points in the life course, this paper draws attention to displacement as an important aspect of the transition to adulthood. Additionally, the analysis demonstrates the benefits of considering a range of anti-social and illicit behaviors. Future work should therefore continue to develop and apply models of behavior and desistance that capture the full range of anti-social acts evident during the transition to adulthood.

Notes

To avoid redundancy, within person displacement is simply referred to as displacement for the remainder of the paper. I draw attention to the within-person, or individual nature of the behavior stressed in this paper as opposed to the developed research tradition on spatial displacement of crime, or the shifting of crime from one community location to another (Bursik and Grasmick 1993; Griffiths and Chavez 2004; Wilson 1987).

I draw particular attention to the slow process of Stanley moving away from violence, as he went back to “Jack-Rolling” after prison, and often used violence to settle social disputes, such as work problems (Shaw 1966, p. 180). Stanley’s slow and uneven movement away from violence is suggestive of displacement as well as desistance.

While an explicit discussion appears later in the paper, the empirical methods used in this analysis are also based on counts. However, the methods used in this paper analyze the association patterns as given by the cell frequencies in a cross classification of a variety of different offenses as well as the cross classification of latent offending classes.

I conducted multiple tests of robustness to examine age variation in the results. The results reported here appear robust under multiple specifications. See Appendix 2 for a more complete discussion.

Lauritsen concludes the NYS may suffer from testing effects (1998, p. 150). However, the main analysis in that paper is based on ordinal responses and further sub-analysis is based on frequencies and does not extend to the measures used in this analysis. However, in light of Lauritsen’s critique, and other work that advocates dichotomous measures (Piliavin et al. 1986, p. 105), prevalence indicators rather than rate measures are used in this analysis.

The final number of categories in a latent variable is determined by specifying multiple models, each with a different number of latent categories, and then assessing the model fit of each specification. See Appendix 2 for a detailed discussion of model selection.

Model fit is assessed through multiple indictors, including a BIC statistic, an index of dissimilarity, and chi-square tests (McCutcheon 1987). Model robustness is assessed in multiple ways. I used a different national sample of youthful offending, the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY), I conducted sub-analysis within the National Youth Survey based on the age of respondents, and I made minor modifications to the offending measures used for analysis. In all cases, the results were substantively similar, both in terms of the number of latent classes and the characteristics of the offending classes. See Appendix 2 for a more detailed discussion.

I conducted a formal test for an abstainer group, and there is not model support for this specification. This is consistent with other research using similar methods (see for instance, Laub et al. 1998; D’Unger et al. 1998). One implication of most latent class analysis is that individuals who commit very few crimes and individuals who commit no crime can be grouped in the same class. I thank a reviewer for pointing to this substantive implication of this aspect of the latent class methodology.

Statistical significance is tested by fixing parameters and examining model fit statistics relative to an unrestricted model. In a series of model estimations, I set the vandalism, theft, and violence parameters in the predatory class to be equal to the estimated parameters in the normative class, and the results suggest a significantly poorer model fit. This indicates that the difference between the prevalence of these crimes in the adolescent predatory class and the adolescent normative class is statistically significant. This procedure was repeated multiple times to test for difference in behavior, for instance, whether the drug use class had elevated rates of substance use relative to the predatory group. Model fit is assessed through a df chi-square comparison of the restricted and unrestricted model. See McCuthchen (1987) and Clogg (1977) for more information.

While the defining feature of this group is the predatory nature of their criminal involvement, the likelihood of involvement in violence, theft, and vandalism is much lower than the predatory group in adolescence, an issue I address in more detail below.

Testing for differences over time is methodologically identical to the process outlined in footnote 7. Substantively the difference involves restricting, for instance, adolescent violent behavior in any given latent class to be identical to adult violent behavior in a given class, and then assessing model fit.

The transition table is a product of assigning individuals to latent classes in adolescence and young adulthood. This is generally done in one of two ways. One method, modal probability, assigns individuals to latent groups which they have the highest probability of being involved (for instance, Laub et al. 1998). The method used in this paper takes into account the uncertainty of latent class membership. The sample is assigned a latent class membership based on the exact probability of membership in each latent class. This is a two-stage process; first using the CDAS program (Eliason 1997), I calculated the exact probabilities of all 1,383 individual cases in the sample falling in each of the four latent classes. Then using random count techniques in SAS, each case is randomly assigned to one of the four latent classes based on the exact probabilities of falling in a latent class. Taken in sum, this reduces the uncertainty associated with latent class membership (see discussions by Laub et al. 1998; Roeder et al. 1999).

When using age adjusted measures there is some conceptual overlap between stability and displacement of behavior. For example some individuals who were stealing from school in youth are stealing from work in adulthood, which may suggest some displacement of behavior. However, this pattern of behavior is most consistent with notions heterotypic continuity, thus it is treated as stability of behavior.

In this case, the ordering of the latent variable is not explicit. Clearly, the normative class is the least serious, and pervasive class is the most serious. However, whether the drug class or the violent class is more serious, and the scaling or the distance between latent classes is unclear.

I test for zero, one, two and three dimensional solution, and the data support a one dimensional solution, which is presented in Fig. 1.

The dimensional axis is bound between −1 and 1. Fig. 1 presents the adjusted or standardized scores.

The formula for the pairwise test of significance is: \(z=(\hat{\nu}a-\hat{\nu}b)/\sqrt{V(\hat{\nu}_a)+V(\hat{\nu}_b)- 2\hbox{cov}(\hat{\nu}_a\hat{\nu}_b)}\) where \(\hat{\nu}_a\) and \(\hat{\nu}_b\) are the estimated RC association model scores for latent classes a and b respectively, \(V(\hat{\nu}_a)\) and \(V(\hat{\nu}_b)\) give the estimated variances of \(\hat{\nu}_a\) and \(\hat{\nu}_b\), and \(\hbox{cov}(\hat{\nu}_a\hat{\nu}_b)\) gives the covariance. The null hypothesis is that the true distance between the two latent classes is zero. In the present analysis a significant pairwise association indicates that moving from one latent class to another represents a significant change in behavior.

References

Bachman JG, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Johnston LD, Bryant AL, Merline AC (2002) The decline of substance use in young adulthood: changes in social activities, roles, and beliefs. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ

Bachman JG, Wadsworth KN, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE (1997) Smoking, drinking, and drug use in young adulthood: the impacts of new freedoms and new responsibilities. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ

Becker MP (1990) Algorithm AS 253: maximum likelihood estimation of the RC(M) association model. Appl Stat 39:152–167

Bohrnstedt G, Knoke D (1994) Statistics for social data analysis, 3rd edn. E. Peacock Publishers, Itasca, IL

Brame R, Paternoster R (2003) Missing data problems in criminological research: two case studies. J Quant Criminol 19:55–78

Brame R, Piquero A (2003) Selective attrition and the age-crime relationship. J Quant Criminol 19:107–128

Brame R, Bushway SD, Paternoster R (2003) Examining the prevalence of criminal desistance. Criminology 41:423–448

Bursik R Jr, Gramick HG (1993) Neighborhoods and crime: the dimensions of effective community control. Lexington Books, California

Bushway SD, Thornberry TP, Krohn MD (2003) Desistance as a developmental process: a comparison of static and dynamic approaches. J Quant Criminol 19:129–153

Bushway S, Piquero A, Broidy L, Cauffman E, Mazerolle P (2001) An empirical framework for studying desistance as a process. Criminology 39:491–516

Caspi A (1998) Personality development across the life course. In: Eisenberg N (eds) Handbook of child psychology, vol. 3: social, emotional, and personality development. Wiley, New York

Clogg CC (1977) Unrestricted and restricted maximum likelihood latent structure analysis: a manual for users. Working paper no. 1977–09. Pennsylvania State University, Population Issues Research Center, University Park, PA

Clogg CC (1995) Latent class models. In: Arminger G, Clogg C, Sobel ME (eds) Handbook of statistical modeling for the social and behavioral sciences. Plenum Press, New York

Clogg CC, Eliason SR, Wahl RJ (1990) Labor-market experiences and labor-force outcomes. Am J Sociol 95:1536–1576

Clogg CC, Eliason SR, Leicht K (2002) Analyzing the labor force: concepts, measures, and trends. Plenum Press, New York

Clogg CC, Shihadeh ES (1994) Statistical models for ordinal variables. Sage Publication, Beverly Hills

Cohen J (1986). Research on criminal careers: individual frequency rates and offense seriousness. In: Blumstein A, Cohen J, Roth J, Visher C (eds) Criminal careers and “career criminals.” Report to the National Academy of Sciences Panel on Research on Criminal Careers. National Academy Press, Washington, DC

D’Unger AV, Land KC, McCall PL, Nagin DS (1998) How many latent classes of delinquent/criminal careers? Results from mixed Poisson regression Analyses. Am J Sociol 103:1593–1630

Eliason SR (1993) Maximum likelihood estimation: logic and practice. Sage Publication, Beverly Hills

Eliason SR (1995). Modeling manifest and latent dimensions of association in two-way cross-classifications. Sociol Methods Res 24:30–67

Eliason SR (1997) The categorical data analysis system user’s manual. Version 4.0

Elliott D, Huizinga D, Ageton S (1985) Explaining delinquency and drug use. Sage Publications, Beverly Hills

Elliott D, Huizinga D, Menard S (1989) Multiple problem youth: delinquency, substance abuse, and mental health problems. Springer-Verlag, New York

Farrington D, Hawkins D (1991). Predicting participation, early onset, and later persistence in officially recorded delinquency. Crim Behav Ment Health 1:1–33

Felson RB, Haynie DL (2002) Pubertal development, social factors, and delinquency among adolescent boys. Criminology 40:967–988

Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Nagin DS (2000) Offending trajectories in a New Zealand birth cohort. Criminology 38:525–551

Francis B, Soothill K, Fligelstone R (2004) Identifying patterns and pathways of offending behaviour: a new approach to typologies of crime. Eur J Criminol 1:48–87

Glueck S, Glueck E (1940) Juvenile delinquents grown up. Oxford University Press, New York

Glueck S, Glueck E (1968) Delinquents and nondelinquents in perspective. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Goodman LA (1987) New methods for analyzing the intrinsic character of qualitative variables using cross-classified data. Am J Sociol 93:529–583

Gottfredson M, Hirschi T (1990) A general theory of crime. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA

Griffiths E, Chavez JM (2004) Communities, street guns and homicide trajectories in Chicago, 1980–1995: merging methods for examining homicide trends across space and time. Criminology 42:941–978

Heimer K, Matsueda RL (1994) Role taking, role commitment, and delinquency: a theory of differential social control. Am Sociol Rev 59:365–390

Hindelang M, Hirschi T, Weis JG (1981) Measuring delinquency. Sage Publication, Beverly Hills

Hirschi T, Gottfredson M (1983) Age and the explanation of crime. Am J Sociol 89:552–584

Jang SJ, Johnson BR (2001) Neighborhood disorder, religiosity, and adolescent use of illicit drugs: a test of multilevel hypotheses. Criminology 39:109–144

Laub JH, Nagan D, Sampson RJ (1998) Trajectories of change in criminal offending: good marriages and the desistance process. Am Sociol Rev 63:225–239

Laub JH, Sampson RJ (2003) Shared beginnings, divergent lives: delinquent boys to age 70. Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA

Lauristen J (1998) The age-crime debate: assessing the limits of longitudinal self-report data. Soc Forces 77:127–155

Loeber R, Le Blanc M (1990) Toward a developmental criminology. In: Tonry M, Morris N (eds) Crime and justice. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Van Kammen W, Farrington D (1991) Initiation, escalation, and desistance in juvenile offending and their correlates. J Crim Law Criminol 82:36–82

Maruna S (2000) Making good: how ex-convicts reform and rebuild their lives. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC

Matsueda R (1992) Reflected appraisals, parental labeling, and delinquency: specifying a symbolic interactionist theory. Am J Sociol 97:1577–1611

McCutcheon A (1987) Latent class analysis. Sage Publications, New York

McDermott S, Nagin DS (2001) Same or different? Comparing offender groups and covariates over time. Sociol Methods Res 29:282–319

Moffitt T (1993) Life-course-persistent and adolescence limited antisocial behavior: a developmental taxonomy. Psychol Rev 100:674–701.

Moffitt TE, Krueger RF, Caspi A, Wright R (2000) Partner abuse and general crime: how are they the same? How are they different? Criminology 38:199–232

Nagin D, Farrington D, Moffitt T (1995) Life-course trajectories of different types of offenders. Criminology 33:111–140

Nagin D, Tremblay RE (2001) Analyzing developmental trajectories of distinct but related behaviors: a group based method. Psychol Methods 6:18–34

Paternoster R, Brame R (1998) The structural similarity of processes generating criminal and analogous behaviors. Criminology 36:633–670

Paternoster R, Brame R (2000) On the association between self-control, crime, and analogous behaviors. Criminology 38:971–982

Piliavin I, Gartner R, Thornton C, Matsueda R (1986) Crime, deterrence, and rational choice. Am Soc Rev 51:101–119

Piquero AR, Brame R, Mazerolle P, Haapanen R (2002a) Crime in emerging adulthood. Criminology 40:137–170

Piquero A, MacIntosh R, Hickman M (2002b) The validity of a self-reported delinquency scale: comparisons across gender, age, race, and place of residence. Sociol Methods Res 30:492–529

Roeder K, Lynch K, Nagin D (1999) Modeling uncertainty in latent class membership: a case study in criminology. J Am Stat Assoc 94:766–776

Sampson RJ, Laub JH (1990) Crime and deviance over the life course: the salience of adult social bonds. Am Sociol Rev 55:609–627

Sampson R, Laub J (1993) Crime in the making: pathways and turning points through life. Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA

Shaw C (1966) The Jack-Roller, 5th edn. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Shover N (1993) Great pretenders: pursuits and careers of persistent thieves. Westview Press, Boulder

Silver E (2000) Extending social disorganization theory: a multilevel approach to the study of violence among persons with mental illnesses. Criminology 38:1043–1074

Steffensmeier D, Allan E, Harer M, Streifel D (1989) Age and the distribution of crime. Am J Sociol 94: 803–831

Uggen C (2000) Work as a turning point in the life course of criminals: a duration model of age, employment, and recidivism. Am Sociol Rev 65:529–549

Warr M (1998) Life-course transitions and desistance from crime. Criminology 36:183–215

Wilson W (1987) The truly disadvantaged. The inner city, the underclass and public policy. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Wright BR, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Silva PA (1999) Low self-control, social bonds, and crime: social causation, social selection, or both? Criminology 37:479–514

Wright BR, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Silva PA (2001) The effects of social ties on crime vary by criminal propensity: a life course model of Interdependence. Criminology 39:321–351

Yamaguchi K (1987) Event-History analysis: its contributions to modeling and causal inference. Sociol Theor Method 2:61–82

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health [#MH19893]. I am especially indebted to Christopher Uggen, Scott Eliason, and Ryan King for their constructive advice. I also thank Shawn Bushway, Valerie Clark, Jennifer Lee, Ross Macmillan, Jeylan Mortimer, Raymond Paternoster, Alex Piquero, Eric Silver, Jeremy Staff, Sara Wakefield, David McDowall and three anonymous reviewers for their comments on an earlier version of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the annual meetings of the American Sociological Association, San Francisco, August 2004.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Measurement of Offending

Prior research on desistance uses dichotomous measures, particularly research in the behavioral desistance tradition (see, for instance, Farrington and Hawkins 1991; Loeber et al. 1991; Warr 1998). Aside from the general utility of dichotomous measures, the use of such indicators to test ideas of displacement or desistance warrants discussion. I independently model involvement in six distinct types of criminal behavior. In doing so, I capture a greater range of offending behavior than much prior work and leverage the unique information from multiple types of illicit and anti-social behavior, rather than masking variation in a single summed indicator. The strength of the method is the range of behaviors captured, while a possible weakness is the lost information on the frequency of certain behaviors.

However, there is some debate as to the overall utility of frequency measures. Some research questions the accuracy of asking the “number” of times an offense happens, arguing that indicators of whether an event “ever” happened are more reliable (Piliavin et al. 1986; Hindelang et al. 1981). In this study, the vandalism measure included damaging family property, school property, and other property. These three response categories were collapsed into one dichotomous variable representing overall involvement in vandalism. Thus, consistent with prior work (Fergusson et al. 2000) in the analysis, people who reported involvement in any of the three crimes are coded “1” for involvement in vandalism and “0’ for no involvement in vandalism.

There are also weaknesses inherent to using dichotomous indicators, for instance an individual who commit a crime multiple times in adolescence and only once in adulthood would be coded the same at both time points. Moreover, someone who commits multiple crimes is treated the same as someone who commits a single act, hypothetically making individuals who are heavily involved in crimes, for instance frequent cocaine use, look similar to those whose cocaine use is infrequent. However, the coding scheme used in the latent class analysis cross classifies six types of crime to create 64 different offending patterns. Under such a scheme, for frequent and isolated cocaine use to look identical, someone heavily involved in cocaine use would have to display no antisocial behavior in other areas of the life course, for example binge drinking or workplace problems, as individual assignment into latent classes is based on the co-occurrence of the range of behaviors measured. While any measurement decisions have potential drawbacks, the research design used allows for a precise examination of movement in out of various crimes that adds to the exiting body of research that has used summary frequency scales.

To capture theft, a dichotomous measure asks respondents if they have stolen money, stolen from family, or stolen things at school. A dichotomous measure of involvement in violence is created by collapsing respondents’ frequency of hitting parents, hitting students, and hitting others. Similarly, marijuana use is coded into a single dichotomous variable. Involvement in other drug use (hallucinogen, amphetamines, and cocaine) is collapsed into a dichotomous variable, called hard drug use. In adolescence, the general deviance indicator includes whether respondents have been drunk, publicly disorderly and/or skipped class. In adulthood the measure captured whether respondents had been drunk/bought alcohol for minors, been publicly disorderly, and whether they had been fired for cause, measured by asking if respondents had lost their job for violation of work rules such racial or sexual discrimination or drug use at work. The measures used for the general deviance indicator were driven by theory (Gottfedson and Hischi 1990) and past empirical work (Glueck and Glueck 1968). The descriptive statistics are reported for each of the 6 offending measures in Appendix 1, Table 5.

Appendix 2. Model fit, Selection, and Robustness

The latent class analysis indicates that four distinct offending patterns best represent criminal behavior in youth. I test for model specifications using two, three, four, and five offending patterns. Multiple indicators are used to assess model fit. As shown in Appendix 2, Table 6, in all cases, the fit statistics best support a four class model. When assessing fit under different offending specifications, a low BIC statistic, low index of dissimilarity, and non-significant p-values generally indicate a proper model specification.

In adolescence, models with two or three offending patterns are not well supported by the data. That is, neither the likelihood ratio chi-square statistic, the index of dissimilarity, nor the BIC statistic suggests the two or three class models adequately represent the data. When examining the five pattern specification, again, there is no support over the specification with four offending patterns. In contrast, all indicators of fit suggest a model with four offending patterns.