Abstract

Numerous studies have identified a late-onset pattern of offending, yet debate remains over whether this pattern is real or attributable to measurement error. The goal of the present study is to identify whether this late-onset trajectory exists. We used prospective longitudinal data from the Rochester Youth Development Study and group-based trajectory modeling to identify distinct developmental patterns in self-reported incidence of general delinquency from approximately ages 14 to 31. We then examined and compared the means of general, violent, street, and property offending for individuals belonging to late bloomer, chronic, and low-level offending trajectories across three periods: (1) pre-onset (ages 14–17), (2) post-onset (ages 29–31), and (3) for a subset of participants participating in a follow-up study, post-trajectory (ages 32–40). Results confirmed the existence of a distinct late bloomers offending trajectory characterized by low rates of delinquency throughout adolescence and high levels throughout adulthood. Furthermore, late bloomers had similar mean levels of delinquency as low-level offenders and they were considerably lower than chronic offenders in the pre-onset period and similar means of offending as chronic offenders that were considerably higher than low-level offenders in the post-onset and post-trajectory periods. Comparisons of these three groups on adolescent risk and protective factors indicated that late bloomers were more similar to individuals in the low-level trajectory and had fewer risk and more protective factors than individuals following a chronic trajectory. Contrary to prior work which attributes late-onset offending to reliance on official data which fails to detect adolescent offending, late bloomer offending appears to be a genuine phenomenon. These results lend greater support to dynamic theories of crime.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

One of the basic premises of the life-course perspective is that off-time transitions—those that come at an earlier or later age than is the norm—have important implications for development. Off-time transitions have consequences, often creating disorder in the life course. In criminology, most research on off-time transitions has focused on early transitions, such as early-onset offending or precocious transitions to adulthood (Moffitt, 1993; Patterson & Yoerger, 2002). There has been much less research on late transitions, such as late onset of offending.

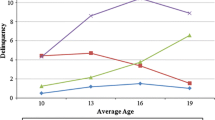

Several studies have identified a pattern of offending in which onset of offending occurs after the typical adolescent onset that occurs around ages 14–15 (Bushway et al., 2003). Although overlooked in conventional studies of criminal careers (Eggleston & Laub, 2002), late- or adult-onset offenders have been identified in numerous prospective, longitudinal samples (Joliffe et al., 2017). Despite this, considerable skepticism remains about the late-onset offender in life-course criminology. Theories that adopt a population heterogeneity perspective which emphasizes the importance of early traits and their relative stability over the life course—such as Gottfredson and Hirschi (1990), Moffitt (1993), and Patterson and colleagues (1989)—posit that late- or adult-onset offending does not constitute a meaningful pattern of offending but instead tends to be rare, trivial, infrequent, and short-lived. In contrast, state dependence theories which emphasize the importance of life events, turning points, and other changes that deflect trajectories over the life course—such as Thornberry and Krohn (2001, 2005) and Sampson and Laub, 1995; (Laub & Sampson, 2003)—suggest that adult-onset or late-onset offending constitutes a real and meaningful pattern that can reflect frequent, serious, and persistent offending.

In the present study, we examine the criminal trajectories of an adult-onset or late-onset offending group—one which we term late bloomers—and compare them in terms of prevalence, frequency, severity/heterogeneity, and persistence of offending, to other more conventional categories such as low-level and chronic groups. Our goal is to determine whether the late bloomer pattern constitutes a real and meaningful pattern of criminal offending.

Defining Late Bloomers

In defining late bloomers, we adopt a life-course perspective. According to the general age-crime curve, the modal age of onset of criminal careers occurs around age 14; research has shown that most individuals who will engage in offending will have done so by age 16 or 17 and will be on a path to desistance after this point.Footnote 1 We use the term late bloomer to refer to individuals whose trajectories of offending emerge and escalate only after the age normative peak, from approximately age 17 onward. This definition is distinct from the related concepts of adult-onset or late-onset offenders as used in taxonomic theories (e.g., Moffitt, 1993; Patterson et al., 1989). In those theories, late-onset offenders, or late starters, often describe individuals whose onset typically occurs during the age normative period of adolescence in order to contrast them with their early-onset counterparts whose offending begins during early or late childhood (e.g., Moffitt’s life-course persisters). Adult-onset offenders are typically defined as those whose first offense occurs after a static cut point, typically defined according to legal standards. This static orientation, which emphasizes changing from one state (non-offending) to another (offending) at a particular point in time, is limited in that the cut points that distinguish adult-onset or late-onset tend to be somewhat arbitrary—for example, previous studies have used cut points ranging from 18 (Eggleston & Laub, 2002) to 25 (Sohoni et al., 2014)—and inconsistent with developmental science, which emphasizes the continuity or progression of human development across the life course. Static definitions may also result in categories that are overly inclusive, leading to heterogeneous classifications (see Bushway et al., 2003; Joliffe et al., 2017).

In contrast, the concept of late bloomers which we embrace emphasizes a developmental process that unfolds continuously over time. Although offending may begin during adolescence, the defining characteristics of late bloomers are threefold (Thornberry & Matsuda, 2011):

-

1.

During early adolescence, their rate of offending is substantively indistinguishable from non-offenders and persistently low-level offenders;

-

2.

Their criminal careers emerge only near the end of adolescence, after the peak of the age-crime curve;

-

3.

Thereafter, their criminal careers reflect persistent, nontrivial involvement in criminal behavior.

Consistent with this approach, Bushway et al. (2003) estimated trajectories of offending from ages 14–22 using participants in the Rochester Youth Development Study (RYDS) and identified a group of late bloomers with these characteristics. Specifically, they found that prior to age 18, individuals in their late starters category were indistinguishable from those in the low-level offending group on an index of general offending but had increased their rate to over 10 offenses every 6 months by age 20. Approximately 10% of the sample were identified as late starters using this developmental/dynamic approach, in contrast to only 6.5% who were identified as late starters using a static definition—that is, no offending before age 18 but at least one offense after age 18 (Bushway et al., 2003).

Importance of Late Bloomers

The study of late bloomers has important implications for developmental, life-course theories of criminal behavior. The existence of late bloomers is a clear point of distinction between theories emphasizing population heterogeneity and those emphasizing state dependence (Nagin & Paternoster, 2000). Static theories, which emphasize population heterogeneity and the persistent influence of early established traits, challenge the notion of late bloomers. For example, Moffitt’s original developmental taxonomy argues that antisocial behavior contains only two categories of offenders: life-course persistent and adolescence-limited. According to Moffitt, “adult-onset crime is not only very unusual, but it tends to be low rate, nonviolent, and generally not accompanied by the many complications that attend a persistent and pervasive antisocial lifestyle” (1993: 12). Similarly, Gottfredson and Hirschi (1990) claim that the “empirical fact of a decline in the crime rate with age is beyond dispute” (1990: 131). These theories tend to emphasize the importance of traits established during early development as causes of criminal behavior, stability of these traits over the life course (in Gottfredson and Hirschi’s case, relative stability), and continuity in trajectories of criminal behavior that is attributable to the persistent influence of these traits established during early development.

Conversely, dynamic theories emphasizing state dependence argue that late bloomers are one of many patterns of offending that may emerge depending upon the interplay of risk and protective factors over the life course. State dependence theories do not dismiss the importance of early development or deny the existence of stability in offending but rather emphasize the importance of proximal factors, life events, turning points, and other time-varying factors that may influence trajectories. Further, these theories recognize that cumulative disadvantage and other reciprocal and interactional processes underpin continuity in criminal trajectories (Sampson and Laub, 1995; Laub & Sampson, 2003; Thornberry & Krohn, 2005). Although these are general explanations (i.e., they have been proposed to explain all patterns of offending), the study of time-varying factors associated with change in criminal trajectories has been primarily restricted to the study of desistance from crime during adulthood and relatively little attention has been paid to the question of late-onset offending.

Given that the presence of late bloomers represents a challenge to the logical integrity of population heterogeneity theories, one important priority is to establish whether late bloomers exist as a meaningful subgroup of criminal offenders. If late bloomers are absent or constitute a relatively small proportion of the offending population and their careers are trivial, infrequent, and short-lived, they may not be a major challenge to static theories or population heterogeneity arguments. On the other hand, if they are prevalent and their offending is frequent, serious, and persistent, then they present a challenge to such approaches and instead support dynamic theories and state dependence arguments. More importantly, research showing that late bloomers constitute a meaningful subgroup of offenders also necessitates both future theoretical and empirical work to explain this pattern of offending.

Prior Literature

Increasingly, empirical evidence has shown that there does exist a late bloomer pattern of offending. In an early review of research on late-onset offenders, Eggleston and Laub (2002) showed that, across 18 longitudinal studies, the average percentage of nondelinquents with an adult offense was 17.9% and that these late-onset offenders accounted for (on average) about half the adult offender population. In a recent systematic review, Joliffe et al. (2017) identified 14 prospective, longitudinal studies that contained information about adolescence limited, life-course persistent, and late-onset offender types. They found that the prevalence of late-onset offenders ranged from 2% in the Kauai Longitudinal Study to 45% in the Cambridge-Somerville Study.Footnote 2 In secondary analysis of several of these samples, the authors found that late-onset offenders—defined as a first offense after age 20—constituted anywhere from 10.3 to 41.7% of male offenders and 4.2 to 20.8% of female offenders and typically made up the largest category of offenders (not including non-offenders). In addition, they more often had a lower frequency of offending over their criminal careers than adolescence-limited and life-course persistent groups (although equal to or greater than adolescence-limited in some samples)Footnote 3 and sometimes shorter criminal career durations, the latter likely due to their relatively later age of onset (ranging from age 24.7 to 36.6) compared to other offenders (ranging from age 12.9 to 17.6). The authors note that estimates of frequency and prevalence tended to converge when similar criminal career durations were used, highlighting the importance of considering longer follow-up periods and accounting for criminal career duration in definitions of different offending subtypes.

As Joliffe and colleagues (2017) observe, these estimates of criminal career dimensions (and potentially, etiological explanations, as well) are highly sensitive to the source of measurement and data regarding criminal behavior, as well as follow-up length, sample composition, definitions, and other conceptual and methodological differences across studies. For example, 43.5% of the National Youth Survey sample was classified as a late-onset offender when using official records, but 0% was classified when using self-report measures (Joliffe et al., 2017). Indeed, one of the major sources of skepticism regarding late- or adult-onset offending is that their very existence is an artifact of measurement error due to reliance on official or administrative data. According to this criticism, late-onset offenders are simply offenders who were not officially sanctioned (via arrest, conviction) prior to adulthood. Relatedly, official classifications that rely on a single arrest or conviction (e.g., for a DUI or possession of controlled substance) may not be indicative of a meaningful “criminal career.” Consistent with this perspective, several studies have attempted to address whether late-onset or adult-onset offenders exist or whether this particular offender is an artifact of official measurement.

McGee and Farrington (2010) used the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development (CSDD) to examine adult-onset offenders—defined as those whose first record of offending occurred at age 21 or later. They show that almost one quarter of all offenders are considered adult-onset according to this definition, and that, on average, adult-onset offenders had lower rates of offending than youthful-onset offenders. Further, they found that adult-onset offenders tended to engage in crimes associated with adult status, such as sex crimes, theft from work, and fraud, or crimes with lower detection rate, such as assault, drug use, and vandalism. Furthermore, a significant proportion (about 30%) of adult-onset offenders had high rates of self-reported offending during adolescence but was able to avoid conviction until adulthood, suggesting that they are not true adult-onset offenders but rather simply not caught until adulthood. They also find evidence that the remaining 70% comprises a real adult-onset group which has low levels of self-reported offending during childhood and adolescence but increases their rate of offending during adulthood (and is eventually convicted).

Wiecko (2014) used the National Youth Survey to retrospectively examine self-reported offending of individuals classified as late-onset according to timing of officially recorded offenses. Of individuals who self-reported an offense during wave 6 (spanning approximately ages 17–22), only two late-onset offenders could be identified who did not self-report an offense during waves 1 through 5, and none could be identified who did not self-report an “arrestable offense.” Thus, the author concluded that late-onset could largely be explained by reliance on official records, which fail to capture much juvenile offending.

Sohoni et al. (2014) used two prospective longitudinal studies: the CSDD and the first twelve waves of the RYDS, to examine the existence of adult-onset offenders. They used a developmental cut point of age 25 to define adult-onset offenders and retrospectively examined the prevalence of self-reported offending of subjects with no convictions or arrests, first conviction or arrest prior to age 18, first conviction or arrest between ages 18 and 25, and first conviction or arrest after age 25 (adult-onset offenders). They found that by age 18, 83% of adult-onset offenders in the CSDD and 90% of adult-onset offenders in the RYDS had self-reported an offense. In addition, they calculated a variety of scores that summed the number of different types of offenses committed at each time period to estimate trajectories for general, violent, property, and serious offending (contrasting with Bushway et al.’s (2003) use of a count measure of the frequency of general offending) and found no evidence of an adult-onset or late-onset offender group.

In contrast, several other studies have identified a group of offenders who fit the late bloomer pattern of offending. For example, Simpson and colleagues (2016) found that 40% of the incarcerated women in their sample were classified as adult-onset (age 18 or older) based on use of a life history event calendar to assess the age of onset of criminal involvement. A number of studies using group-based trajectory modeling have also identified a late-onset trajectory of offending across a variety of data sources. For example, Mata and van Dulmen (2012) identified adult-onset trajectories of both aggressive and non-aggressive antisocial behaviors in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Chung and colleagues (2002) also identified a “late onsetter” group that constituted over 14% of the Seattle Social Development Project sample. In addition, a late-onset chronic offender group was identified in the 1942 Racine birth cohort and constituted about 5% of the cohort (D’Unger et al., 1998). Van Koppen and colleagues (2014) also identified two late bloomer trajectories in their 1984 Dutch birth cohort, and they constituted 18% of these males. In addition, a number of studies have attempted to identify specific risk factors for late-onset patterns of offending (for example, see Farrington et al., 2009; Gomez-Smith & Piquero, 2005; Kratzer & Hodgins, 1999; van der Geest et al., 2009; Zara & Farrington, 2009).

To summarize, numerous prospective, longitudinal studies have identified a late- or adult-onset offender group; however, the vast majority of these studies have relied on official data sources to determine age of onset. Those that compare both official data sources with self-reports of offending often do not find evidence of a true late- or adult-onset offender. Although these latter studies appear to cast doubt on the existence of late bloomers, they suffer from several limitations which make this conclusion premature. Specifically, they have primarily relied on a retrospective approach in which they identify adult-onset or late-onset offenders according to the timing of the first officially recorded offense (e.g., police contact, arrest, court conviction, or registration for a crime) and then examined whether these individuals self-reported any prior offending previously. However, as McGee and Farrington (2010: 540) note, “the prevalence of offending in self-report data is very high…therefore, a measure based on whether an individual has ‘ever’ offended is not useful.” For example, Sohoni and colleagues (2014) showed that most adult-onset offenders had self-reported offending by age 18; yet, about three quarters of non-offenders self-reported general offending, half self-reported violence, and a non-trivial proportion (39–45%) also self-reported property and serious crime, leaving questions about the utility of these comparisons. With the exception of McGee and Farrington (2010), who compared the frequency of offending of youthful to adult-onset offenders, few studies have examined the frequency or severity of such offending.

Our study seeks to address these gaps and differs from these previous studies in three ways. First, we eschew the retrospective and static orientation of prior research and adopt a developmental approach (Bushway et al., 2003) to examine late bloomers. Specifically, we use group-based trajectory modeling (Nagin, 2005) rather than static age cut points (e.g., non-offending prior to, but offending after, age 18) to identify a late bloomer pattern of offending, if it exists. Second, we utilize self-reported offending data to identify late bloomers. In their review of eighteen longitudinal studies reporting on adult-onset, Eggleston and Laub (2002) identified only one that relied on self-report data for criminal history. Similarly, in their review of prospective longitudinal studies on prevalence and other criminal career dimensions of various offending patterns, Joliffe et al. (2017) only identified four out of fourteen studies that relied on self-report (in combination with official record) data as opposed to official record data only. Third, we extend the follow-up period beyond the typical period of emerging adulthood by estimating trajectories through approximately age 31 and, for a subset of the sample, examining post-trajectory criminal behavior through approximately age 40. One criticism of prior research is that there is much less evidence about the long-term criminal careers of late bloomers, as few studies have examined self-reported offending beyond emerging adulthood (around age 25, if not earlier) (Joliffe et al., 2017). Thus, we attempt to address whether adult-onset offending is sustained throughout adulthood or whether this pattern is merely temporary. Of the studies reviewed above that utilized group-based trajectory modeling, only three utilized self-report data on criminal history (Chung et al., 2002; Mata & van Dulmen, 2012; Sohoni et al., 2014); of these, the latest age at follow-up was approximately age 25. For example, Chung et al. (2002) estimated trajectories through age 21 in the Seattle Social Development Project, Sohoni et al. (2014) estimated trajectories through age 23 in the Rochester Youth Development Project, and Mata and van Dulmen (2012) estimated trajectories through wave 3 of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, when participants were between the ages of 18–25.

The Present Study

The present paper uses longitudinal data that extends from adolescence (age 14) to early adulthood (age 31) and, for a subset of participants, to age 40, to determine if late bloomers are a discernible subgroup of offenders. In addressing this issue, we adopt a developmental, life-course perspective on the topic of late bloomers, especially as presented in the interactional theory of Thornberry and Krohn (2017). According to this perspective, if late bloomers exist, their involvement in offending should be substantively indistinguishable from that of non-offenders and persistently low-level offenders during early to mid-adolescence, their criminal careers should emerge only towards the end of adolescence after the peak of the age-crime curve, and, after that point, their criminal careers should reflect persistent involvement in nontrivial types of offending. In addition, late bloomers will have a combination of individual risk factors but are buffered by family protective factors throughout early childhood and adolescence, which leads them to have relatively low rates of offending throughout these early developmental stages. During emerging adulthood, however, the protective influences of parental bonds diminish and their individual deficits reduce the likelihood of successful transitions to adult roles and responsibilities. Consistent with this perspective, prior research shows that late bloomers report greater parental attachment and supervision and higher parental expectations for education (and fewer peer risks) than high-rate offenders, yet lower engagement in school and greater stressors and internalizing problems than non-offenders during the adolescent years (Thornberry & Matsuda, 2011; see also Krohn et al., 2013). Based on this model, we hypothesize the following:

-

1.

Using the theoretical definition of late bloomers provided above, there is evidence that late bloomers can be identified in a group-based trajectory modelFootnote 4 even when the observation period is extended to age 31.

-

2.

(a) Prior to their increase in offending during later adolescence, the offending of late bloomers is similar to that of low-level or abstainer groups and significantly less than that of chronic offenders. (b) Conversely, after onset, late bloomer offending is similar to that of chronic offenders and significantly greater than that of low-level offenders.

-

3.

The criminal careers of late bloomers persist into the adult years and are characterized by serious and frequent offending—that is, their careers are not short-lived or characterized by infrequent and trivial offending.

-

4.

During adolescence and prior to onset of offending, late bloomers will look more similar to individuals in the low-level offending group with respect to risk and protective factors. In particular, they will possess fewer risk factors and more protective factors than individuals following the chronic offending trajectory.

Methods

To address our first question—how large a share of the offending population does the late bloomer group constitute?—we extend the trajectory models estimated by Bushway et al. (2003), which ended around age 22, to end at approximately age 31. Specifically, we estimated trajectories of self-reported incidence of general delinquency across 14 assessments, spanning approximately ages 14–31. Like Bushway et al. (2003), we relied on the general index of offending to estimate our trajectories because we sought to initially examine the broadest type of offending, and examined specific subsets of offending in subsequent analyses. To allow for model convergence, it was necessary to eliminate extreme outliers. To do so, we recoded the top 10th percentile of subjects with the value of the frequency reported at the 90th percentile of the frequency distribution.Footnote 5

To address our second question—how extensive and serious is late bloomer’s involvement in criminal behavior?—we examine the incidence of general, violent, street, and property offending of late bloomers as compared to other types of offenders identified in the trajectory modeling, such as low-level and chronic groups. Specifically, we conducted one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with contrasts to examine differences between means of late bloomers and low-level offending groups and between late bloomers and chronic groups at three separate developmental periods: pre-onset (ages 14–18), post-onset (ages 29–31), and post-trajectory (ages 34–40).Footnote 6 In accord with our hypotheses, we expect that late bloomers will be statistically indistinguishable from low-level offenders and have significantly lower means of offending than chronic groups in the period prior to onset, and that late bloomers will have significantly more frequent offending than the low-level offenders but be statistically indistinguishable from the chronic offenders during the post-onset and post-trajectory periods.

Data

We use data on self-reported offending patterns from two companion prospective longitudinal studies. The RYDS selected 1000 7th and 8th grade students in the Rochester Public School system in the 1987–1988 academic year to examine developmental patterns of delinquency and drug use, oversampling males and individuals who reside in Census tracts with high arrest rates to ensure adequate representation of involvement in delinquency and drug use (which have a low base rate in the population). The sample is 73% male, 68% African American, and 17% Hispanic and is representative of the population (with appropriate weighting techniques). Data collection occurred across 14 waves spanning roughly ages 14 to 31, with the first nine waves conducted at 6-month intervals (ages 14–18), the next three waves (10–12) at annual intervals (ages 20–22), and the two final waves (13–14) at approximately ages 29 and 31. At each wave, participants were surveyed regarding a variety of delinquent behaviors, as well as risk and protective factors for delinquency across numerous developmental domains (e.g., family, peers, and schools). Official records from schools, social services, and police are also available for participants who consented to record checks.

The Rochester Intergenerational Study (RIGS) was initiated in 1999 to examine intergenerational continuities and discontinuities in delinquency and drug use. Original RYDS participants who remained in the study at wave 12 were eligible for the RIGS once they had a biological child who turned 2 years of age. The RYDS participants were interviewed annually until their child turned 18, and we continued to ask them about their self-reported delinquency and involvement with the criminal justice system. Attrition analyses showed few statistically significant differences between original sample members and those who were ineligible for the intergenerational study (for reasons other than parenthood status) or dropped out, indicating that the RIGS sample is largely representative of the original RYDS sample members who became parents (Thornberry et al., 2018). Together, the RYDS and RIGS provide self-reported longitudinal data on criminal offending through ages 31 for the original sample and through age 40 for the subset of the original sample enrolled in the RIGS (n = 468).

Measures

Our measures are primarily based on self-report data collected from waves 1–14 of the original RYDS and years 9–20 of the RIGS. Because our goal is to assess a wide range of offending behaviors and compare individuals in late bloomer to low and chronic offending groups, we focus on four indexes of delinquent or criminal offending behavior: general offending, violence, street offending, and property offending. Each of these indices is based on a set of dozens of items related to criminal behavior asked at each interview wave. For each item, participants were asked to report whether they engaged in the behavior and, if so, how many times (responses were open-ended). The reference period for each item depended on the wave. For wave 1, the reference period was ever (to assess whether the subject had engaged in the behavior) or since school started in September (to assess the frequency of the behavior). For waves 2 through 9 and waves 11 and 12, the reference period was since the date of their last interview, which was typically 6 months (for waves 1 through 9, covering adolescence) to 1 year earlier (waves 11–12, covering emerging adulthood). For waves 10, 13, and 14, the reference period was 1 year.

Incidence of General Offending

This index reflects a broad array of criminal behaviors ranging in severity, including violence, property crime, and drug sales. At each wave, participants were asked to report their frequency of engaging in each of these criminal behaviors during the reference period. To reflect the age-graded nature of offending, different items were included at each wave. For example, status offenses such as running away and truancy were included through wave 7 only (when the average age of participants = 17), whereas DWI and paying for sex are only available after wave 8.

Incidence of Violence

To examine the severity of involvement in criminal behavior, we examined the incidence of violent delinquency. At each wave, participants were asked to report the frequency of engaging in up to six violent behaviors, ranging from simple assault to attacking with a weapon and robbery.

Incidence of Street Offending

To further examine offending mix, we include street offending, a measure that captures a mix of violent, property, and general offending behaviors. The offenses in this index are typically committed in public places and are often the types of offenses that are of greatest concern to both the public and criminal justice officials. At each wave, participants were asked to report the frequency of engaging in up to 12 behaviors since their prior interview such as weapon carrying, marijuana and hard drug sale, gang fights, and breaking and entering.

Incidence of Property Offending

Finally, we examined property offending. At each wave, participants were asked to report the frequency of engaging in up to 14 behaviors since their prior interview ranging from theft of various amounts to forgery to car stealing.

During the pre-onset period, participants were asked to report the frequency of involvement in 38 delinquent behaviors ranging from minor status offenses, such as truancy, to more serious offenses, such as assault with a weapon. During the post-onset period, many items, such as status offenses, were dropped from the interview schedule. Finally, because data for the post-trajectory period is from the RIGS in which the focus of the intergenerational study is on the third-generation participants, the parent interview contains an abbreviated set of delinquency items. Thus, due to differences in measurement frequency and the number of items available at different waves or years of each study, the incidence of offending is not directly comparable across these three periods of time. Furthermore, because the data contain many individuals who report no involvement in delinquency, distributions for all these measures are highly skewed. All items included in each scale are displayed in Table 5 in the Appendix, and descriptive statistics are reported in Table 6 in the Appendix.

Risk and Protective Factors

To assess substantive differences across groups, we also examined a set of adolescent risk and protective factors across several important life domains, including area characteristics, family sociodemographic characteristics, parent–child relationship, school factors, peer factors, and individual characteristics. These measures were primarily taken from parent and youth reports during waves 2 and 3 of the original RYDS, when participants were in early adolescence (and prior to late bloomer’s onset of offending). Details on these variables can be found in Table 7 in the Appendix, as well as previous publications (Thornberry et al., 2003).

Results

Do Late Bloomers Exist?

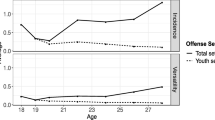

Figure 1 displays the results of the optimal group-based trajectory model. Drawing on prior work using group-based trajectory modeling with RYDS data which estimated trajectories through approximately age 22 (Bushway et al., 2003), we estimated a series of group-based trajectory models extended to age 31. We fit 6-, 7-, and 8-group solutions and used BIC, AIC, and likelihood ratio scores to identify the optimal solution. The optimal model was a 6-group model with quadratic terms to allow for common offending trajectories. Maximum likelihood estimates are reported in Table 8 in the Appendix. We used the maximum-probability assignment rule—which assigns individuals to the group with the highest probability—to classify individuals into groups (Roeder et al., 1999) . Posterior probabilities of group membership for each group exceeded 0.95, indicating the model corresponded well to the data (Nagin, 2005). The graph depicts two low-level offending groups whose rates of involvement in general delinquency were consistently low throughout the measurement period (low 1 = 31.8% and low 2 = 15.3%), two chronic offending groups whose involvement in general delinquency was high and prolonged across adolescence and early adulthood (late = 15.4% and early = 12.9%), a desisting group whose involvement in general delinquency was concentrated in adolescence only (11.9%), and a late bloomerFootnote 7 group (12.7%) whose involvement in general delinquency was low throughout adolescence but began to rise in adulthood.

Table 1 displays our model adequacy checks according to several criteria described by Nagin (2005). The first criterion, average posterior probability of group membership, can range from 0 to 1, with values equal to 1 indicating perfect accuracy. As stated previously, values across all groups ranged from 0.949 to 0.984, thereby indicating a low likelihood of classification error. The second criterion—odds of correct classification—also indicates high levels of classification accuracy. Values on this criterion are very high for all groups, far exceeding Nagin’s (2005) standard of 5. The third criterion, the correspondence between the maximum likelihood estimate of the average probability of group membership (\(\widehat{\pi }\)) and the proportion of the sample assigned to each group (\(\widehat{P}\)), indicates greater classification accuracy when values are in close proximity and greater classification error when values are divergent; across all groups, the differences between \(\widehat{\pi }\) and \(\widehat{P}\) are no greater than 3/1000 of one another, again indicating a high degree of classification accuracy. The fourth and final criterion, 95% confidence intervals for group membership probabilities, indicates greater accuracy when lower and higher bounds are narrow and lesser accuracy when these intervals are wide. Here, the confidence intervals for all groups are relatively narrow, with differences between upper and lower bounds ranging from 0.04 to 0.06. Thus, judging by these several diagnostic criteria, we can have strong confidence in this model.

These results supported our first hypothesis: there is evidence of a late bloomer offending trajectory as a subgroup of offending trajectories. The late bloomer group constituted almost 13% of the sample, which is somewhat larger than the 9.7% identified in Bushway et al. (2003) and comparable in size to prior research on late bloomers (Joliffe et al., 2017). This trajectory displayed relatively low rates of involvement in general delinquency throughout adolescence, lower than all but one group (the non-offending group). Around age 17, however, the late bloomers began to increase their frequency of offending and their trajectories intersected with the declining low group. By age 22, their trajectories of offending had intersected with and surpassed the desisting group, and by age 29, their trajectories of offending had intersected with and surpassed one of the two chronic groups. By age 31, their rates of offending were higher than all other trajectory groups.

Late Bloomer Offending Comparisons Pre-onset, Post-onset, and Post-trajectory

We next compared the means of offending across developmental periods between the different groups. For ease of comparison, we combined the two low-level offending groups into a single “low” group (n = 473) and the two chronicFootnote 8 groups into a single “chronic” group (n = 281). Because our focus in this paper is on late bloomers, we excluded the desisting group from our comparisons and instead focused on comparisons between the late bloomer group and the low and chronic groups. Results of these comparisons are presented in Table 2. Each table displays means of offending indices for general, violent, street, and property offending for each group at pre-onset, post-onset, and post-trajectory, along with results of ANOVA tests with contrasts examining whether differences in means were statistically significant from the late bloomer are displayed in the low and chronic columns. To test our hypotheses that differences in means between the late bloomer and low groups were less than the differences in means between the chronic and late bloomer groups during the pre-onset period, and whether differences between the late bloomer and low groups were greater than the differences between the means of the chronic and late bloomer group in the post-onset and post-trajectory periods, we display 95% confidence intervals for mean differences in the two right-hand columns. Narrower and non-overlapping confidence intervals suggest greater confidence in differences whereas wider and overlapping confidence intervals suggest less certainty in differences.Footnote 9

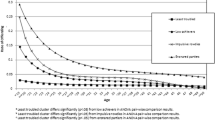

The top panel of Table 2 displays our results for the pre-onset period. During this period, late bloomers had a mean incidence of general, violent, street, and property offending that was statistically indistinguishable from individuals in the low-level group and significantly less than individuals in the chronic group. Furthermore, confidence intervals for differences in means between the late bloomer and low and late bloomer and chronic groups did not overlap.

The middle panel of Table 2 displays our results for the post-onset period. During this period, the pattern displayed in the pre-onset period is reversed such that mean offending for late bloomers was similar to that of individuals belonging to the chronic group and significantly greater than individuals belonging to the low-level group for general, violent, and street offending; property offending was not significantly different between late bloomer and low and late bloomer and chronic groups (although means differed significantly between individuals in the chronic and low groups). With the exception of property offenses, the confidence intervals for mean differences between individuals in the late bloomer and low and late bloomer and chronic groups did not overlap.

Finally, the middle panel of Table 3 displays our results for the post-trajectory period. During this period, the late bloomers had significantly greater general, street, and property offending during the post-trajectory period. In contrast, means of violent offending did not differ between individuals in the late bloomer and low group, or those in the late bloomer and chronic group (although, again, the low and chronic groups were significantly different). Reflecting the greater uncertainty of these estimates, the confidence intervals for late bloomer and low and late bloomer and chronic overlapped for all four outcomes.

To summarize, late bloomers displayed means of general, violent, street, and property offending that were statistically indistinguishable from the means of the low-level group and significantly less than the means of the chronic group in the pre-onset period. In the post-onset and post-trajectory periods, this pattern largely reversed itself such that the means of the late bloomers were greater than the means of the low group (although not always significantly so) and statistically indistinguishable from the chronic group. A summary of these results is presented in Table 3, showing support consistent with our hypotheses for seven of the relationships we examined, with partial support for the remaining five.

Late Bloomer Risk and Protective Factors During Adolescence

In Table 4, we present means and percentages of risk and protective factors across six domains measured during early adolescence. We estimated contrasts for one-way analysis of variance or chi-square tests for comparisons between late bloomer, non-offender, and chronic groups. We expected that the late bloomers would have fewer risk factors and more protective factors than the chronic offenders and that they would be similar to the low-level offenders. Significance stars in the columns displaying means and percentages for the low and chronic groups indicate differences relative to the late bloomer group, with other differences noted in the text.

Results indicated that there were no differences across the three groups on any area or family sociodemographic characteristics. For nine factors, late bloomers were significantly different from individuals following the chronic trajectory at the value of p < 0.10 or less. Specifically, late bloomers (and low-level offenders) had significantly greater attachment to parents, parental supervision, and parental college expectations than individuals following the chronic trajectory. In addition, late bloomers (and low-level offenders) had significantly lower delinquent peers, early dating, unsupervised time with friends, negative life events, depression, and delinquent beliefs than those in the chronic group. For three factors, low-level offenders were significantly different from both late bloomers and chronics. Specifically, low-level offenders reported significantly higher commitment to school and attachment to teacher than late bloomers and chronics. The low-level group had a significantly lower proportion of males than either the late bloomer or chronic groups. For the remaining seven factors, differences were reported between low-level offenders and chronics on six factors (attachment to child, positive parenting, family hostility, college aspirations, college expectations, and internalizing problems); for self-esteem, late bloomers reported significantly higher rates than chronics.

To summarize, late bloomers largely resembled low-level offenders by reporting fewer risk factors and more protective factors than chronics. Of the several factors we examined, late bloomers only reported two indicators of disadvantage similar to chronics: lower commitment to school and lower attachment to teacher. This suggests that late bloomers are largely protected from delinquency in early adolescence but show some early signs of potential deficits in human capital that could disrupt the successful transition to adulthood.

Discussion

In general, our results confirmed our hypotheses regarding late bloomers. Using group-based trajectory modeling, we identified a group of individuals who followed a late bloomer trajectory of offending. They were comparable in general offending frequency to both of the low offending groups throughout adolescence but increased in frequency steadily throughout adulthood and even intersected with and surpassed both chronic group trajectories by their late twenties and early thirties. The prevalence of late bloomer offending—at about 13% of the overall sample—was roughly comparable in size to prior research on late starters (Bushway et al., 2003; Joliffe et al., 2017), as well as adolescence-limited, or desisting groups. In addition, the results of one-way ANOVAs comparing the differences in means of the late bloomer and low groups and late bloomer and chronic groups generally fit the pattern we expected. Results showed that late bloomers were not distinguishable from the low group and significantly less delinquent than chronics during the pre-onset period; however, during the post-onset period, they were not distinguishable from the chronic group and engaged in significantly more offending than the low group. Furthermore, patterns in the post-onset period were consistent during the post-trajectory period for the subset of participants in the intergenerational study, suggesting that late bloomer offending continues to persist throughout the thirties.

We also found that late bloomers largely resembled individuals in the low-level offending group on an array of early adolescent risk and protective factors. Late bloomers reported greater parental supervision and college expectations and fewer delinquent peers, delinquent beliefs, unsupervised time with friends, early dating, negative life events, and depression than individuals who ultimately followed a chronic offending trajectory. They only differed from individuals in the low-level offending group in three ways. First, they were more likely to be male. Second, they reported lower commitment to school and attachment to teacher, at levels similar to the chronic group. This suggests they may have early deficits in academic or social skills, which could have persistent or cumulative consequences, ultimately interrupting the successful transition to adulthood.

There were some exceptions to our findings. First, in the post-onset period, we failed to uncover any statistically significant differences between means of late bloomers and the low group for property offending. Second, in the post-trajectory period, we failed to uncover any statistically significant differences between the means for violent offending of the late bloomer and low groups. In both instances, the means of the late bloomers were greater than the means of the low group (and in the case of property offending, even chronic group). Finally, for all offending types, in the post-trajectory period, 95% confidence intervals for upper and lower bounds of differences in means between the late bloomer and low and late bloomer and chronic groups were wide enough to at least partially overlap. Thus, differences during this period do not rise to conventional standards for statistical significance. This may be because we have fewer observations in the post-trajectory period (see Table 6 in the Appendix); therefore, there is less statistical power to identify any potentially significant differences in means.

Results from these analyses have several implications. First, our findings suggest that the late-onset pattern of offending is not merely an artifact of reliance on official data. We were able to identify a substantively meaningful trajectory pattern that followed a late bloomer course of offending using self-report data on the incidence of offending from age 14 to 31. Not only did this late bloomer pattern persist beyond the criminal career durations typically examined in previous studies (through the early to mid-twenties), but data from a subset of participants who were followed through age 40 in a separate companion study confirmed that higher levels of offending persisted in the post-trajectory period for a variety of offending types. Furthermore, in contrast to an earlier study using the same data but a shorter follow-up period (Bushway et al., 2003), we found that a greater proportion of individuals fell into the late bloomer trajectory, which suggests that some individuals following this pattern of offending may take longer to emerge. This underscores the necessity of utilizing both a developmental approach as well as follow-up periods of sufficient length to identify the late bloomer pattern of offending.

These results have broader implications for research on criminal offending trajectories. They lend greater support to dynamic perspectives, such as the life course theories of Thornberry and Krohn (2005) and Laub and Sampson (2003), which posit that transitions and turning points can offer opportunities for changes in criminal trajectories. Given that prior research on turning points has largely focused on desistance from, rather than late-onset of, adult offending, future research would benefit from an examination of the turning points that lead to escalation in offending behaviors during the transition to adulthood. At the same time, our results cast doubt on static perspectives, such as that of Gottfredson and Hirschi (1990), which argues that individual differences, determined early in the life course, can sufficiently explain longer-term patterns of criminal offending.

Finally, our results have several practical implications. To start, prevention programs and interventions that target early-onset delinquency will fail to reach a sizable portion of individuals who will go on to offend in adulthood. Furthermore, research shows differing risk profiles of early- and late-onset offending (Zara & Farrington, 2009, 2010). To develop effective prevention tools, including more accurate risk assessments, as well as early interventions, more research is needed to identify the unique risk and protective factors of late bloomer offending at various stages of the life course.

Although we have tried to employ the most rigorous methodology to identify late bloomers and the extensiveness of offending among individuals who follow this trajectory, our study has limitations. Results are only generalizable to a 2-year public-school cohort from one urban area. Future research should attempt to replicate our findings with samples from other areas at other time periods. Further, our research is subject to other commonly identified limitations of longitudinal self-report data, such as panel fatigue. Unfortunately, the Rochester study does not have a consistent set of official records, such as arrest and conviction, capturing involvement in criminal offending over each of our three periods (pre-onset, post-onset, and post-trajectory). Thus, we were unable to conduct parallel analysis based on official data. Finally, like all prospective longitudinal studies, our offending trajectories are limited by the length of the follow-up period, for which criminal history data are available for the full sample only through about age 31. To the extent that some individuals who follow the late bloomer trajectory may have an onset after age 31 (Joliffe et al., 2017), some late bloomers may be misclassified. Although our reliance on self-report (rather than official) data minimizes this as a major possibility, we note it as a potential limitation to our study.

These limitations aside, this is the first study to have used a prospective approach that relies on self-reported offending over a 15-year period to identify the late bloomer trajectory of offending and to compare various forms of offending to other common trajectories of criminal offending at multiple phases of the life course. Our results suggest that the late-onset offender should not be dismissed as merely an artifact of official data, but rather that late bloomers constitute a meaningful pattern of offending that requires further investigation.

Notes

But, see Steffensmeier et al. (2017) who showed that the age-crime curve may differ in societies with more collectivist/less individualistic cultures.

Among males, they ranged from 9.2 to 44.2%; among females, they ranged from 3.1 to 4.9%.

Joliffe et al. (2017) reported that late-onset offenders had lower rates of offending than adolescence-limited or life-course persistent offenders throughout their criminal careers in seven samples reviewed in their study and rates of offending equal to or greater than adolescence-limited (although still less than life-course persistent) in four samples.

The group-based trajectory model has been widely used in studies of late-onset offending and criminal career trajectory patterns (Piquero, 2008).

At wave 1, for example, participants who scored in the top 10% of the frequency distribution (n = 94) reported an incidence of general delinquency ranging from 20 (90th percentile) to 250 (100th percentile). These participants had their scores recoded so that they were equal to 20. This was done for all fourteen waves. Although we experimented with other recoding strategies (e.g., recoding at the 95th percentile), we had issues with model convergence when such extreme outliers were included.

Although general delinquency measured from pre-onset to post-onset is used to identify our trajectory groups as well as examine offending mix, we include it for two reasons. First, we examine this measure at separate developmental periods captured during (pre-onset, post-onset) and after (post-trajectory) the trajectory is estimated. Second, general offending is included as a baseline to compare various subtypes of offending (i.e., violent, street, property). We note, however, that including this measure as an outcome (during the pre-onset and post-onset periods) may be somewhat tautological.

We also observed a late bloomer group in both the 7-group and 8-group models. In the 7-group model, the mixture probability for the late bloomer group was virtually identical to that of the 6-group model (n = 12.3%). In the 8-group model, the mixture probability for the late bloomer group was 8.6%.

Although both “chronic” groups appear to have desisted from offending between early and later adulthood, we use the term “chronic” to refer to this group because they have engaged in the most frequent offending over the life course, particularly when compared to other groups.

We also estimated a series of nonparametric rank-sum tests which tested the null hypothesis that the distribution of delinquency is the same between groups. In general, results were substantively similar.

References

Bushway, S. D., Thornberry, T. P., & Krohn, M. D. (2003). Desistance as a developmental process: A comparison of static and dynamic approaches. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 19(2), 129–153.

Chung, I. J., Hawkins, J. D., Gilchrist, L. D., Hill, K. G., & Nagin, D. S. (2002). Identifying and predicting offending trajectories among poor children. Social Service Review, 76(4), 663–685.

D’Unger, A. V., Land, K. C., McCall, P. L., & Nagin, D. S. (1998). How many latent classes of delinquent/criminal careers? Results from mixed Poisson regression analyses. American Journal of Sociology, 103(6), 1593–1630.

Eggleston, E. P., & Laub, J. H. (2002). The onset of adult offending: A neglected dimension of the criminal career. Journal of Criminal Justice, 30(6), 603–622.

Farrington, D. P., Ttofi, M. M., & Coid, J. W. (2009). Development of adolescence-limited, late-onset, and persistent offenders from age 8 to age 48. Aggressive Behavior, 35(2), 150–163.

Gomez-Smith, Z., & Piquero, A. R. (2005). An examination of adult onset offending. Journal of Criminal Justice, 33(6), 515–525.

Gottfredson, M. R., & Hirschi, T. (1990). A general theory of crime. Stanford University Press.

Joliffe, D., Farrington, D. P., Piquero, A. R., MacLeod, J. F., & van de Weijer, S. (2017). Prevalence of life-course-persistent, adolescence-limited, and late-onset offenders: A systematic review of prospective longitudinal studies. Journal of Aggression and Violent Behavior, 33, 4–14.

Kratzer, L., & Hodgins, S. (1999). A typology of offenders: A test of Moffitt’s theory among males and females from childhood to age 30. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 9(1), 57–73.

Krohn, M. D., Gibson, C. L., & Thornberry, T. P. (2013). Under the protective bud the bloom awaits: A review of theory and research on adult-onset and late-blooming offenders. In C. L. Gibson & M. D. Krohn (Eds.), Handbook of life-course criminology: Emerging trends and directions for future research (pp. 183–200). Springer.

Laub, J. H., & Sampson, R. J. (2003). Shared beginnings, divergent lives: Delinquent boys to age 70. Harvard University Press.

Mata, A. D., & van Dulmen, M. H. (2012). Adult-onset antisocial behavior trajectories: Associations with adolescent family processes and emerging adulthood functioning. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(1), 177–193.

McGee, T. R., & Farrington, D. P. (2010). Are there any true adult-onset offenders? The British Journal of Criminology, 50(3), 530–549.

Moffitt, T. E. (1993). Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100(4), 674–701.

Nagin, D. S. (2005). Group-based modeling of development. Harvard University Press.

Nagin, D. S., & Paternoster, R. (2000). Population heterogeneity and state dependence: State of the evidence and directions for future research. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 16(2), 117–144.

Patterson, G. R., & Yoerger, K. (2002). A developmental model for early-and late-onset delinquency. In J. B. Reid, G. R. Patterson, & J. Snyder (Eds.), Antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: A developmental analysis and model for intervention (pp. 147–172). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10468-007

Patterson, G. R., DeBaryshe, B. D., & Ramsey, E. (1989). A developmental perspective on antisocial behavior. American Psychologist, 44(2), 329–335.

Piquero, A. R. (2008). Taking stock of developmental trajectories of criminal activity over the life course. In The long view of crime: A synthesis of longitudinal research (pp. 23–78). Springer.

Roeder, K., Lynch, K. G., & Nagin, D. S. (1999). Modeling latent class membership: A case study in criminology. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 94(447), 766–776.

Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (1995). Crime in the making: Pathways and turning points through life. Harvard University Press.

Simpson, S. S., Alper, M., Dugan, L., Horney, J., Kruttschnitt, C., & Gartner, R. (2016). Age-graded pathways into crime: Evidence from a multi-site retrospective study of incarcerated women. Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology, 2(3), 296–320.

Sohoni, T., Paternoster, R., McGloin, J. M., & Bachman, R. (2014). ‘Hen’s teeth and horse’s toes’: The adult onset offender in criminology. Journal of Crime and Justice, 37(2), 155–172.

Steffensmeier, D., Zhong, H., & Lu, Y. (2017). Age and its relation to crime in Taiwan and the United States: Invariant, or does cultural context matter? Criminology, 55(2), 377–404.

Thornberry, T. P., & Krohn, M. D. (2001). The development of delinquency: An interactional perspective. In S. O. White (Ed.), Handbook of youth and justice (pp. 289–305). Plenum.

Thornberry, T. P., & Krohn, M. D. (2005). Applying interactional theory to the explanation of continuity and change in antisocial behavior. In D. P. Farrington (Ed.), Integrated developmental and life-course theories of offending (pp. 183–209). Transaction Publishers.

Thornberry, T. P., & Krohn, M. D. (2017). Interactional theory: An overview. In D. P. Farrington, L. Kazemian, & A. R. Piquero (Eds.), The Oxford handbook on developmental and life-course criminology. Oxford University Press.

Thornberry, T. P., Henry, K. L., Krohn, M. D., Lizotte, A. J., & Nadel, E. L. (2018). Key findings from the Rochester Intergenerational Study. In V. Eichelsheim & S. van de Weijer (Eds.), Intergenerational continuity of criminal and antisocial behavior: An international overview of current studies (pp. 214–234). Routledge.

Thornberry, T. P., Krohn, M. D., Lizotte, A. J., Smith, C. A., & Tobin, K. (2003). Gangs and delinquency in developmental perspective. Cambridge University Press.

Thornberry, T. P., & Matsuda, M. (2011, May). Why do late bloomers wait? An examination of factors that delay the onset of offending. Presented at the Stockholm Criminology Symposium. Stockholm.

Van Der Geest, V., Blokland, A., & Bijleveld, C. (2009). Delinquent development in a sample of high-risk youth: Shape, content, and predictors of delinquent trajectories from age 12 to 32. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 46(2), 111–143.

Van Koppen, M. V., Blokland, A., Van Der Geest, V., Bijleveld, C., & van de Weijer, S. (2014). Late-blooming offending. Oxford handbook online. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhndb/9780199935383.013.56

Wiecko, F. M. (2014). Late-onset offending: Fact or fiction. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 58(1), 107–129.

Zara, G., & Farrington, D. P. (2009). Childhood and adolescent predictors of late onset criminal careers. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(3), 287–300.

Zara, G., & Farrington, D. P. (2010). A longitudinal analysis of early risk factors for adult-onset offending: What predicts a delayed criminal career? Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 20(4), 257–273.

Acknowledgements

Support for the Rochester Youth Development Study has been provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA020195, R01DA005512), the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (86-JN-CX-0007, 96-MU-FX-0014, 2004-MU-FX-0062), the National Science Foundation (SBR-9123299), and the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH56486). Technical assistance for this project was also provided by an NICHD grant (R24HD044943) to the Center for Social and Demographic Analysis at the University at Albany. Points of view or opinions in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the funding agencies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Matsuda, M., Thornberry, T.P., Loughran, T.A. et al. Are Late Bloomers Real? Identification and Comparison of Late-Onset Offending Patterns from Ages 14–40. J Dev Life Course Criminology 8, 124–150 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-022-00189-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-022-00189-9