Abstract

The purpose of the present study was to explore the relation of work-related risk factors and well-being among healthcare workers and the impact on patient safety, using the Health and Work Survey (INSAT) and Mental Health Continuum - Short Form (MHC-SF). A sample of 361 Portuguese healthcare workers participated in this study. The results indicate some significant work-related risk factors: for emotional well-being, Impossible to express myself (β = −0.977), Not having recognition by superiors (β = −1.028) and Have to simulate good mood and/or empathy (β = −1.007); for social well-being, Exposed to the risk of sexual discrimination (β = −2.088), Career progress is almost impossible (β = −1.518), and Have to hide my emotions (β = −2.307); finally for psychological well-being Exposed to the risk of sexual discrimination (β = −2.153), Career progress is almost impossible (β = −1.377), and Have to simulate good mood and/or empathy (β = −3.201). The results showed high levels of well-being despite the exposure of several risk factors at workplace. Regarding the work-related risk factors, the study showed that most of the participants are exposed to several risk factors at workplace (ranging from environmental risk factors, biological to physical), although psychosocial risk factors (work relations with superiors and colleagues, employment relations, and emotional demands) are the ones that most impact on well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Occupational health and well-being

According to the World Health Organization, health can be defined as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being, and not as merely the absence of disease or infirmity”. Therefore, if this definition is applied to the workplace, it implies that health at work does not only concern the physical and mental integrity of workers but should also aim at promoting well-being at work [1, 2]. In recent years, due to structural changes, the workplace is now regarded as a determinant of the individual’s health and well-being [3]. Among numerous risks found in the workplace, such as environment factors, toxicological factors and physical factors, psychosocial risks emerge as a challenge to occupational health research field [4,5,6]. Within this context, the role of workplace on mental health is gaining attention as work is a significant part of an individual’s life and can affect both mental health and well-being.

During the past few years, mental health was operationalized as global state of well-being, given rise to two traditions of study: the eudaimonic and hedonic. The eudaimonic perspective understands well-being as the result of virtuous activities and the meaning given to life and integrates the Ryff’s theory of psychological well-being [7] and Keyes’ social well-being construct [8]. The psychological well-being proposed by Ryff [7], comprises six dimensions (self-acceptance, personal growth, purpose in life, positive relations with others, autonomy, and environmental mastery) associated with the challenges that individuals encounter as they strive to realize their potential. Keyes [8, 9] proposed a model of social well-being with five dimensions (social integration, social contribution, social coherence, social actualization, and social acceptance) and focuses on the individuals’ evaluations of their public and social lives. From the eudaimonic point of view, well-being means functioning well in life, is related to personal growth and fulfilment at an individual level, is associated with commitment to goals and shared values at a societal level [7, 10,11,12]. The hedonic conceptualization involves the study of subjective/emotional well-being that focuses on positive emotions and life satisfaction [13, 14]. Together, the hedonic and eudaimonic perspectives capture the positive spectrum of mental health.

Mental health problems can be induced from work-related risk factors and adverse psychosocial work factors among health workers. To ensure a good quality of care, healthcare staff should be safe and healthy at work as well as highly motivated. However, several studies have indicated that psychosocial risks factors can arise among all occupational groups in the healthcare sector, including nurses, physicians, diagnostic and therapeutic technicians, operational assistants, cleaning staff and those in the medical-technical service. According to the European Commission [6], some of these psychosocial risks are time pressure; rigid hierarchical structures; lack of gratification and reward; inadequate personnel leadership; lack of relevant information; lack of support from management staff; work-related loads (shift work, night work, irregular working hours); social conflicts, harassment, bullying, violence and discrimination: difficulties in the field of communication and interaction, including the failure to comprehend body language and, work organization which is not ideal (working-time arrangements). In this field, some studies indicated that there are high levels of psychological illness among healthcare workers [15,16,17,18,19]. In accordance, psychosocial and work factors that may contribute to this issue should be analysed in order to better explore healthcare workers well-being [20].

Patient safety and healthcare worker occupational health

Patient safety became a high priority for healthcare systems since the publication of the Institute of Medicine’s Report To Err is Human: building a safer health system, with some shocking data on harm associated with clinical errors and adverse events arising from related clinical practice in healthcare organizations [21]. After this report a large number of projects were performed to promote patient safety [22] and efforts, all over the world, were developed to identify and understand the underlying causes of errors and adverse events. Several studies showed that common causes of errors leading to adverse events are related with organizational factors such as: lack of communication/ miscommunication, workload, reduced number of staff, procedures inconsistently implemented, inadequate supervision, lack of leadership, temporary staff, lack of support operations, lack of information systems/quality of information systems [23,24,25].

Experts from this area of knowledge are now understanding that many of the risk factors, that affect healthcare worker also contribute, directly and indirectly, to adverse events on patients and some studies pointed, fatigue, stress, burnout, poor psychological health and high levels of sickness absence of healthcare workers, low job satisfaction, poor social support, lack of participation in decision-making, as some important factors on quality of care [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. Although these factors are directly related with healthcare workers’ well-being, they must be considered causes for not being able to provide consistent quality of care, and consequently, considered as an important issue for patient safety.

According to the exposed, this study aims to explore the mental health and well-being, as well as risk factors among healthcare workers; to analyse the work-related risk factors, which seem to have an important role in well-being; and to analyse the impact of healthcare workers well-being on patient safety.

Material and methods

Instruments

Health and Work Survey (INSAT - Inquérito Saúde e Trabalho) is a self-reported questionnaire organized in different axes, that measure working conditions, health and well-being, and the relationship between them [37, 38]. Concerning the main goal of the present study, only the following risk factors were used: (i) workplace environment factors; (ii) toxicological risk factors; (iii) physical risk factors; (iv) psychosocial risk factors; (v) work characteristics. These categories are organized in different items. For each item, participants are asked to identify if a specific situation is present or absent (using a dichotomous scale ‘yes’ or ‘no’). In terms of psychometric properties, INSAT has a good internal consistency, in a Rasch PCM analysis, with a reliability coefficient > 0.8 [39].

Mental Health Continuum – Short Form (MHC-SF) is a self-reported scale that consists of 14 items rated on a 6-point Likert scale, 1 (never) to 6 (every day). This instrument includes three subscales that measure emotional, social, psychological well-being and (3, 5 and 6 items, respectively). The MHC-SF has been translated into Portuguese, and it has been shown to have good internal reliability (Cronbach’s α coefficients for the total scale as well as sub-scales were all above 0.80) [40, 41].

Data collection

Data was collected in several healthcare providers using a self-administered paper and pencil questionnaire, and conducted between November 2017 and April 2018. Participants received all materials consisting of the INSAT, MHC-SF, a covering letter explaining the purpose of the survey, and the guidelines to complete the two questionnaires. All of the participants gave their informed consent to participate, and their confidentiality was guaranteed.

Sample

The study sample included 361 healthcare workers from the north and centre of Portugal (97%) within the following domains: 12.4% diagnostic and therapeutic technicians; 40.7% nurses; 10.2% operational assistants; 17.5% physicians, and 19.1% psychologists. The majority of the participants were female, 75.9%, and 24.1% were male; ranging age from 21 to 69 (M = 37.50; SD = 10.28); and the most representative age range was 30-39 years old (41.5%). The levels of education reported were basic education (2.8%), secondary (5.9%); undergraduate (62.6%); master degree (27.1%), and PhD (1.7%). A considerable range regarding participants years of experience was also noticed, from those who only have one year of practice to others who had been working for more than 38 years (M = 11.01; SD = 9.46). 75% of the participants were employed under permanent contract, in a working time schedule between 7 AM and 10 PM (52.7%) and 37.5% under a rotating shifts.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis applied to this study was divided in two parts: a descriptive analysis, as well a correlational and regression analysis were applied to all risk factors and well-being measures (i) workplace environment factors; (ii) toxicological risk factors; (iii) physical risk factors; (iv) psychosocial risk factors; (v) work characteristics. The significance level adopted was p ≤ 0.05.

Frequency and percentages on demographic characteristics of participants (nominal variables from the INSAT questionnaire - risks factors) and central tendency parameters (mean and standard deviation on scale variables from Short Form - MHC-SF) were obtained. Point-Biserial Correlations were calculated to determine the association between well-being measures (scale variables from MHC-SF) and work risks factors (nominal variables from INSAT with only two possible values: 0-no; 1-yes). For those variables with significant associations, multiple regression was performed to explain the relationship between the dependent variables (well-being) and the independent variables (risk factors). A multiple linear regression, using Backward method, was applied to identify the significant independent variables (work risk factors) that better adjust the predicting model for well-being (emotional, social and psychological dimensions). All the statistical assumptions were verified and the regression analysis results can be considered reliable.

Results

Descriptive analysis

The descriptive analysis from MHC-SF presents higher well-being scores in terms of emotional well-being, psychological well-being, and social well-being (Table 1).

Descriptive analysis from INSAT, presented in Table 2.

Tables 3 and 4, shows the frequency distribution of the “yes” answers to risk factors that have a significant impact on the work of healthcare workers.

Relationships between risk factors and well-being

To analyse the relationships between risk factors and well-being it was performed a correlation analysis between work risk factors and well-being, as shown in Table 5.

As presented in Table 5 significant inverse associations between work-related risk factors (workplace environment, physical, psychosocial risks) and well-being dimensions (emotional, social, and psychological) were found.

Predicting well-being

Following the identification of significant associations between well-being measures and work risks factors, the relationship between the dependent variables (well-being) and the independent variables (work risk factors) was considered. A multiple linear regression (Backward method) was performed with well-being dimensions and work risk factors with significant correlations found previously (Tables 6, 7 and 8).

Table 6 show that the adjusted model explains 10.5% of the variance in emotional well-being and the independent variables Impossible to express myself, Not having recognition by superiors, and Have to simulate good mood and/or empathy are significant predictors for emotional well-being score.

Statistical data from Table 7 show that the adjusted model explains 10.3% of the variance in social well-being and the independent variables Exposed to the risk of sexual discrimination, Career progress is almost impossible, and Have to hide my emotions are significant predictors for social well-being score.

Table 8 show that the adjusted model explains 12.7% of the variance in psychological well-being and the independent variables Exposed to the risk of sexual discrimination, Career progress is almost impossible, and Have to simulate good mood and/or empathy are significant predictors for psychological well-being score.

Discussion

This study explores the influence of work-related risk factors on well-being dimensions among Portuguese healthcare workers. The results showed high levels of well-being despite the exposure of several risk factors at workplace. These findings suggest that Portuguese healthcare workers can positively cope with the strains of professional life, and work productively and usefully [9]. Feeling good all the time will not be conductive to well-being, since negative and painful emotions play an important part in daily life when experienced in the appropriate context, such as feeling anger following injustice [42].

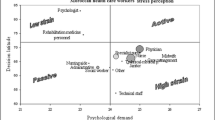

Regarding the work-related risk factors, this study showed that most of the participants are exposed to several risk factors at workplace (ranging from environmental risk factors, biological to physical), although the psychosocial risk factors (work relations with superiors and colleagues, employment relations, and emotional demands) are the ones that most impact on well-being. Indeed, the results are in accordance with recent literature about healthcare workers, about occupational risk perception that indicated the impact of psychosocial risk factors on health and well-being [1, 4, 6, 16, 18, 19].

Among the psychosocial work factors that are associated with well-being, this study found that work relationships are a relevant factor that can explain the well-being levels, which are divided into four keys concepts: no possibility to progress in work and career; not treat fairly and with respect by superiors; impossible to express itself and sexual discrimination. On the other hand, emotional demands, such as, hide emotions and simulate good mood and/or empathy, are also linked to well-being. These results are in accordance with other studies on the impact of work relations and emotional demands, and underlines the role and contribution of social support, social relationships in occupational health and well-being [43,44,45].

In the domain of work relationships, the study found that no possibility to progress in work and career and sexual discrimination have a negative impact on psychological and social well-being. The impossibility to express itself and not be treated fairly and with respect by superiors is also negatively associated with emotional well-being. According to the literature some organizational factors of workplace may have a negative impact on workers’ health: all work should provide workers the possibility of having an active role in their conduction, reflecting the ability of acting by themselves and on their work [46,47,48].

Regarding emotional demands this study found that simulate good mood and/or empathy is negatively associated with emotional and psychological well-being and have to hide emotions with social well-being. These results are in accordance with the literature that emphasizes that in certain occupations emotional demands may be a critical phenomenon for workers’ health [49], particularly in health care sector, where meeting emotional job demands is crucial to organizational outcomes but may negatively affect workers’ well-being [50].

Regarding the impact of healthcare workers’ well-being on patient safety, the results of this study are similar with other studies. Organizational factors, such as workload, high job demands, combined with social factors, such as low social support and teamwork, weak safety culture contribute to patient falls [36]; workers’ non-satisfaction, workload, work safety, and job well done sensation have been identified as principal causes of stress among pharmaceutics with direct impact on dispensing errors [26, 27]. Physicians’ well-being, in general, is positively related with patient satisfaction, patient adherence to treatment, interpersonal aspects of patient care, and the quality of overall care processes [51]; workplace incivility, intimidation, disruptive behaviours, and worker engagement are considered important risk factors for healthcare workers well-being with impact on patient safety [35].

As observed in this study, and in other studies related with these issues, healthcare workers’ wellbeing and patient safety are connected and, most of the risk factors that affect the healthcare worker also, directly or indirectly, affects the patient. Since some areas of concern for worker well-being, directly or indirectly, overlap with patient safety, healthcare leaders can no longer analyse these two issues, based on the traditional silo approach and considering different levels of importance: both are related (cause-effect), both are equal important and must be managed together. Process approach is fundamental to ensure an organizational culture and safety climate in healthcare organizations [36, 52].

Conclusions

Workplace-related health impairments, injuries and illnesses cause great human suffering and incur high costs, both for those affected and for society as a whole. Occupational health and safety measures and health promotion in workplaces aim to prevent this.

This study focused on issues related with the healthcare system and how to improve workers’ health. Findings suggest that if the social support of different types (emotional, functional and structural) and from different interested parts (supervisors, co-workers and the organization) is provided, healthy working conditions can be achieved more efficiently. Since patient care is recognized as a priority, the emotional demands on healthcare workers are generally taken for granted or underestimated. Patient’s well-being is considered an essential aspect of healthcare providers, but if emotional needs of the healthcare workers are attended, patient safety will be promoted.

Since healthcare sector is a high-risk, high demand, high stress industry for both workers and patients, a new management approach, where worker well-being issues and patient safety issues are analysed as “cause-effect” relations and not as completely isolated issues, must be considered to build an organizational culture and safety climate for worker and for patient.

Further research with a larger sample would bring additional information on psychosocial risks factors and would assisted designing better occupational safety and health policies, aimed to enhancing well-being at work.

References

Roland-Lévy, C., Lemoine, J., and Jeoffrion, C., Health and well-being at work: The hospital context. Revue Européenne de Psychologie Appliquée/European Review of Applied Psychology 64(2):53–62, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erap.2014.01.002.

Stansfeld, S. A., and Candy, B., Psychosocial work environment and mental health—a meta-analytic review. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health 6:443–462, 2006. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.1050.

WHO, Health Impact of Psychosocial Hazards at Work, An Overview. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2010.

Giurgiu, D. I., Jeoffrion, C. et al., Psychosocial and occupational risk perception among health care workers: a Moroccan multicenter study. BMC Research Notes 8(1):408, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1326-2.

Giurgiu, D. I., Jeoffrion, C. et al., Wellbeing and occupational risk perception among health care workers: a multicenter study in Morocco and France. Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology 11(1):20, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12995-016-0110-0.

Commission, E., Occupational health and safety risks in healthcare sector - Guide to prevention and good practice S.A.a.I. Directorate-General dor Employment, Editor, Publications Office of the European Union: Luxemburg, 275. 2011, https://doi.org/10.2767/27263.

Ryff, C. D., Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 57(6):1069–1081, 1989. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069.

Keyes, C. L. M., Social Well-Being. Social Psychology Quarterly 61(2):121–140, 1998. https://doi.org/10.2307/2787065.

Keyes, C. L. M., The Mental Health Continuum: From Languishing to Flourishing in Life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 43(2):207–222, 2002. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090197.

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M., Hedonia, eudaimonia, and well-being: an introduction. Journal of Happiness Studies 9(1):1–11, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9018-1.

Juarez, F., El concepto de salud: Una explicación sobre su unicidad, multiplicidad y los modelos de salud. International Journal of Psychological Research 4(1):70–79, 2011.

Massimini, F., and Delle Fave, A., Individual development in a bio-cultural perspective. American Psychologist 55(1):24–33, 2000. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.24.

Diener, E., Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist 55(1):34–43, 2000. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.34.

Pavot, W., and Diener, E., The Satisfaction With Life Scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology 3(2):137–152, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760701756946.

Van Laar, D., Edwards Julian, A., and Easton, S., The Work-Related Quality of Life scale for healthcare workers. Journal of Advanced Nursing 60(3):325–333, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04409.x.

Marôco, J., Marôco, A. L. et al., Burnout em Profissionais da Saúde Portugueses: Uma Análise a Nível Nacional. Acta Med Port 29(1):24–30, 2016.

Taghinejad, H., Suhrabi, Z. et al., Occupational Mental Health: A Study of Work-Related Mental Health among Clinical Nurses. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research: JCDR 8(9):WC01–WC03, 2014. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2014/8247.4835.

Goetz, K., Berger, S. et al., How psychosocial factors affect well-being of practice assistants at work in general medical care? – a questionnaire survey. BMC Family Practice 16(1):166, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-015-0366-y.

Dhaini, S. R., Zúñiga, F. et al., Care workers health in Swiss nursing homes and its association with psychosocial work environment: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Nursing Studies 53:105–115, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.08.011.

Hsu, M.-Y., and Kernohan, G., Dimensions of hospital nurses’ quality of working life. Journal of Advanced Nursing 54(1):120–131, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03788.x.

Kohn, L., J. Corrigan, and M. Donaldson, To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, editor: Institute of Medicine. National Academy of Sciences. 2000.

Baylina, P., and Moreira, P., Challenging healthcare-associated infections: a review of healthcare quality management issues. Journal of Management & Marketing in Healthcare 4(4):254–264, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1179/175330311X13016677137770.

Baylina, P., and Moreira, P., Healthcare-associated infections – on developing effective control systems under a renewed healthcare management debate. International Journal of Healthcare Management 5(2):74–84, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1179/2047970012Z.00000000018.

Johnson, K., Keeping patients safe: an analysis of organizational culture and caregiver training. Journal of Healthcare Management / American College of Healthcare Executives 49(3):171–178; discussion 178-9, 2004.

Chen, I. C., Ng, H.-F., and Li, H.-H., A multilevel model of patient safety culture: cross-level relationship between organizational culture and patient safety behavior in Taiwan's hospitals. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management 27(1):e65–e82, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.1095.

Johnson, S. J., O'Connor, E. M. et al., The relationships among work stress, strain and self-reported errors in UK community pharmacy. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy 10(6):885–895, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2013.12.003.

James, K. L., Barlow, D. et al., Incidence, type and causes of dispensing errors: A review of the literature. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 17(1):9–30, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1211/ijpp.17.1.0004.

Holden, R. J., Patel, N. R. et al., Effects of mental demands during dispensing on perceived medication safety and employee well-being: A study of workload in pediatric hospital pharmacies. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy 6(4):293–306, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2009.10.001.

Feuerberg, M., Appropriateness of Minimum Nurse Staffing Ratios in Nursing Homes. Report to Congress. Baltimore: Health Care Financing Administration, 2000.

Rogers, A. E., Hwang, W.-T. et al., The Working Hours Of Hospital Staff Nurses And Patient Safety. Health Affairs 23(4):202–212, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.23.4.202.

Shanafelt, T. D., Balch, C. M. et al., Burnout and Medical Errors Among American Surgeons. Annals of Surgery 251(6), 2010.

Landrigan, C. P., Rothschild, J. M. et al., Effect of Reducing Interns' Work Hours on Serious Medical Errors in Intensive Care Units. New England Journal of Medicine 351(18):1838–1848, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa041406.

Poghosyan, L., Clarke, S. P. et al., Nurse Burnout and Quality of Care: Cross-National Investigation in Six Countries. Research in Nursing & Health 33(4):288–298, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20383.

Michie, S., and Williams, S., Reducing work related psychological ill health and sickness absence: a systematic literature review. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 60(1):3–9, 2003. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.60.1.3.

Loeppke, R., Boldrighini, J. et al., Interaction of Health Care Worker Health and Safety and Patient Health and Safety in the US Health Care System: Recommendations From the 2016 Summit. JOEM 59(8):803–813, 2017.

Yassi, A., and Hancock, T., Patient Safety - Worker Safety: Building a Culture of Safety to Improve Healthcare Worker and Patient Well-Being. Healthcare Quarterly 8(Sp):32–38, 2005.

Barros, C., Carnide, F. et al., Will I be able to do my work at 60? An analysis of working conditions that hinder active ageing. WORK: A Journal of Prevention, Assessment & Rehabilitation 51:579–590, 2015. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-152011.

Silva, C., Barros, C. et al., Prevalence of back pain problems in relation to occupational group. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics 52:52–58, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ergon.2015.08.005.

Barros, C., Cunha, L. et al., Development and Validation of a Health and Work Survey Based on the Rasch Model among Portuguese Workers. Journal of Medical Systems 41(5):79, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-017-0727-2.

Monte, K., Fonte C., and S. Alves, Saúde mental numa população não clínica de jovens adultos: Da psicopatologia ao bem-estar Revista Portuguesa de Enfermagem de Saúde Mental. 2. 2015.

Fonte, C., C. Ferreira, and S. Alves, Estudo da saúde mental em jovens adultos. Relações entre psicopatologia e bem-estar. Psique, 57-74. 2017.

Huppert Felicia, A., The State of Wellbeing Science. Wellbeing, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118539415.wbwell036.

Yepes-Baldó, M., Romeo, M., and Berger, R., Relationship of health workers with their organization and work: a cross-cultural study. Rev Saude Publica 5(18), 2016. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1518-8787.2016050006285.

Bagdasarov, Z., and Connelly, S., Emotional labor among healthcare professionals: the effects are undeniable. Narrat Inq Bioeth 3(2):125–129, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1353/nib.2013.0040.

Hämmig, O., Health and well-being at work: The key role of supervisor support. SSM - Population Health 3:393–402, 2017.

Letellier, M.-C., Duchaine, C. S. et al., Evaluation of the Quebec Healthy Enterprise Standard: Effect on Adverse Psychosocial Work Factors and Psychological Distress. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15(3):426, 2018. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15030426.

Clot, Y., Travail et pouvoir d’agir. Paris: PUF, 2008.

Work, E. A.f. S.a. H.a., Well-being at work: creating a positive work environment - Literature Review. Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg., 2013. https://doi.org/10.2802/52064.

Balducci, C., Avanzi, L., and Fraccaroli, F., Emotional demands as a risk factor for mental distress among nurses. Med Lav. 105(2):100–108, 2014.

Scheibe, S., Stamov-Roßnagel, C., and Zacher, H., Links Between Emotional Job Demands and Occupational Well-being: Age Differences Depend on Type of Demand. Work, Aging and Retirement 1(3):254–265, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/wav007.

Scheepers, R. A., Boerebach, B. C. M. et al., A Systematic Review of the Impact of Physicians’ Occupational Well-Being on the Quality of Patient Care. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 22(6):683–698, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-015-9473-3.

Rocha, A., and Freixo, J., Information Architecture for Quality Management Support in Hospitals. J Med Syst 39(125), 2015. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-015-0326-z.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors declares that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Education & Training

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Baylina, P., Barros, C., Fonte, C. et al. Healthcare Workers: Occupational Health Promotion and Patient Safety. J Med Syst 42, 159 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-018-1013-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-018-1013-7