Abstract

Canadian population-based surveys report comparable access to health care services between immigrant and non-immigrant populations, yet other research reports immigrant-specific access barriers. A scoping review was conducted to explore research regarding Canadian immigrants’ unique experiences in accessing health care, and was guided by the research question: “What is currently known about the barriers that adult immigrants face when accessing Canadian health care services?” The findings of this study suggest that there are unmet health care access needs specific to immigrants to Canada. In reviewing research of immigrants’ health care experiences, the most common access barriers were found to be language barriers, barriers to information, and cultural differences. These findings, in addition to low cultural competency reported by interviewed health care workers in the reviewed articles, indicate inequities in access to Canadian health care services for immigrant populations. Suggestions for future research and programming are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Immigrants in Canada comprise an important facet of Canada’s cultural landscape. According to Statistics Canada, in 2011 legal immigrants comprised over 20 % of the Canadian population, and nearly 50 % of the population in the City of Toronto [1]. Presently, longitudinal surveys such as the Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada (LSIC) and the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) report comparable access to health care services between immigrants and non-immigrants [2, 3]. However, multiple studies and reviews highlight that in Canada, immigrant contact with health care is punctuated by barriers associated with the immigration experience, including cultural beliefs, literacy discrepancies, and discrimination [4–6]. These may be compounded by factors affecting Canadians generally, such as long wait times, inconvenient hours of service, and financial concerns [2]. This means that for immigrants experiencing barriers, ill health due to limited access is complex, and may not be adequately understood by addressing only barriers pertaining to the general population.

The Charter of Rights and Freedoms states that all Canadians should have “reasonable access to health care services” [7, p. 5]. This statement is contestable and at this time, health care access barriers specific to immigrants are not considered the responsibility of the health care system; rather, they are viewed as transient and associated with adjusting to a new country [8]. This is not always the case. For example, among women immigrants who reported access barriers, poor health self-reports rose by 13 % over 4 years compared to only 6 % for women who reported no access barriers [9]. Consequently, policy and attitudes based on general health access statistics may not be recognizing the impact these barriers have on the immigrant population. This scoping review seeks to find what is known about health care access barriers for immigrants to Canada by exploring research on immigrant experience and health care provider response. Through this analysis, knowledge gaps will be identified and suggestions for further research direction will be made.

Methods

This review was undertaken with the approach outlined by Arksey and O’Malley [10]. The search strategy employed an iterative process, and was guided by the primary question: “What is currently known about the barriers that adult immigrants face when accessing Canadian health care services?” For the purpose of this study, immigrants encompassed persons with Permanent Residency status and those who have gained full citizenship. Search terms included: “Canadian healthcare”, “immigrants”, “barriers to access”, “access barriers”, “Canadian immigrants”, and “accessing health care”. These specific phrases were searched independently and in combination with one another using various connecting words.

MEDLINE, CINAHL, Google Scholar, and Summon (Queen’s University Libraries) were searched. MADGIC was also searched for government literature. Abstracts of articles were reviewed based on inclusion criteria: specific focus on adult status immigrant experience of health care access in Canada. Relevant studies were imported to a reference manager (RefWorks) and duplicates were excluded. Studies were then examined further for both inclusion and exclusion criteria. Information on design, population, and purpose, and findings were then tabulated for relevant articles.

Studies were excluded if immigrant sample populations included refugees and undocumented persons, except in cases where data or results from immigrant populations could be easily separated from other groups (including refugees, undocumented persons, and non-immigrants). This measure was taken because undocumented persons and refugees may not have universal access to health care in Canada. Studies with sample populations that included children (<18 years old) were not used because children are not generally responsible for making their own decisions about health care. No studies published previous to the year 2000 were included in order to best reflect current health care access trends in Canada. Studies were considered up to June 2014, which was the time the review was conducted. Studies that focused on health care access barriers to pregnant immigrant women were also excluded. This was done for two reasons: first, because these studies were sufficient in number to warrant independent review and second, because maternal care was viewed as a unique category of health services.

Results

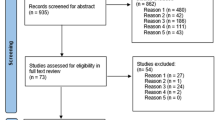

A total of 167 articles were imported into RefWorks, with 68 articles being tabulated (excluding grey literature) as potentially useful. Grey literature and review articles were examined separately and were used for informing scope and direction of research. The articles were categorized based on study design and by type of barrier mentioned.

After final examination, 10 quantitative articles, 15 qualitative articles, and 1 mixed methods article were included for a total of 26 articles. Article attrition was attributable to duplication and to disqualification based on failure to meet inclusion criteria. The final selection of studies included those that took place in Canada and focused specifically on barriers to accessing health care.

Trends in Quantitative and Qualitative Studies

There were 10 studies that employed quantitative methodology to research health service access barriers experienced by immigrants to Canada (Table 1). Of these, six studies analyzed secondary data and four analyzed primary data. Most studies that analyzed secondary data sought to determine whether or not immigrants and non-immigrants experienced different rates of access to health care [11–14]. With the exception of access to cervical cancer screening [15], secondary data analyses revealed no difference in health care access between immigrants and non-immigrants. This result contradicts studies that used primary data to analyze immigrant versus non-immigrant rates of access to health care services, which reported reduced access among immigrants compared to Canadian born persons in terms of diabetes care [16] and access to General Practitioners [17].

The most reported barriers in quantitative studies were linguistic barriers [14, 16, 17, 19, 20], lack of information about how to access or navigate services [14, 16, 18–20], and long wait times/lists [16, 18–20]. Among qualitative studies (n = 15), the most reported barriers were found to be linguistic barriers, cultural differences, and lack of information about how to access or navigate services. Quantitative and qualitative studies thus coincided in two of three most reported barriers: linguistic barriers and lack of information about how to access or navigate services.

Both quantitative and qualitative studies focused on perceived health care needs among the immigrant population. Studies focused on individuals accessing mental health services, breast and cervical cancer screening, seniors, and people with specific conditions (e.g. hepatitis C virus, type 2 diabetes, and asthma), as well as general health care access. Qualitative studies included research specific to health care access experiences of immigrant parents or caregivers, while quantitative studies did not.

Studies of Specific Cultural and Linguistic Groups

Chinese and South Asian immigrant groups were the subjects of 7 out of 14 studies that focused on specific cultural or linguistic backgrounds (Table 1), which is unsurprising given the distribution of Canada’s immigrant population. [21]. Other specific groups studied were Iranian [22], Vietnamese [23], Portuguese-speaking [24], Francophone [25], and Asian [26].

Among studies of Chinese and South Asian immigrant populations, four research topics emerged: South Asian women’s access to cervical cancer screening and mammography [27, 28], health care access barriers for Chinese and South Asian seniors [19, 20, 29], health care access experiences of Chinese and South Asian parents of children with cancer [30, 31], and barriers to accessing family physicians experienced by Chinese immigrants [17].

Among studies that focused on Chinese populations, language was cited as the most important barrier to accessing health care services in Canada [17, 19, 29, 31]. Additionally, research noted that Chinese populations were more likely to experience reduced access to health care services due to reliance on traditional beliefs and medicines [17, 19, 31]. Conversely, studies of South Asian immigrant populations revealed no clear trends. One study [20] cited cultural differences as the most important barrier to accessing health care services among South Asian immigrants, while other studies listed lack of health literacy/limited awareness of disorder [27, 28], and language barriers [30, 31] as most significant.

With two exceptions [20, 29], inclusion criteria among studies of Asian (including South Asian) immigrants contained an ability to speak at least one of several pre-determined languages. Among these studies, language fluency inclusion criteria were limited to Urdu, Hindi, Punjabi, Tamil, Cantonese, Mandarin, Filipino, Vietnamese, Farsi, or English [17, 23, 26, 27, 29–31]. Thus, Asian ethnic minority groups may have been excluded from these studies.

Three studies noted a relationship between immigration class and experience of health care access. In Canada, immigrants are designated as economic immigrants (which encompasses several subcategories), family class immigrants, or refugees. Each category is regulated differently, and is therefore associated with different experiences. Though not specifically designed to explore the effects of immigration class on health care access, Donnelly et al. [23], Sadavoy et al. [29], and Stewart et al. [32] each noted individual barriers to accessing health care that directly related to the immigration category of participants.

Only two studies of specific cultural and linguistic populations took time since immigration into account when analyzing data. Gupta et al. [28] found level of acculturation among South Asian women to be more important than time since immigration in overcoming cervical cancer screening access barriers; participants in a study by Ahmad et al. [27] rated mammography access barriers to be the most concerning 2–5 years post-immigration among South Asian women.

Perspectives of Service Providers and Policy Makers

Seven articles featured perspectives of health care workers, with five of them gaining the perspectives of both immigrants and health and policy workers. All seven articles discussed family structure and responsibility as being major factors that help or hinder immigrants’ access to health care services. In a study by Donnelly et al. [23], some nurses and physicians perceived family obligation as the most important among barriers, linking it to long working hours, childcare needs, and a general dearth of time; other nurses and physicians interviewed, however, did not see family obligation as a barrier since many of their immigrant patients had no excess duties outside of the home. In the same study, immigrants who were interviewed cited family obligations related to financial concerns and time constraints as most important among barriers. Health care providers claimed that this resonates especially with immigrants who have arrived in Canada with family sponsorship, an arrangement in which they feel their presence is contingent on their usefulness [32].

In every study of health care professionals’ and policy makers’ opinions on health care barriers for immigrants, participants recognized language barriers as a factor for discouraging access. They discussed how self-advocacy is a necessary skill for navigating the Canadian health care system, and recognized it as a challenge for immigrants who do not necessarily have the English language ability or confidence to express their needs, opinions and complaints [23, 24, 33, 34]. Health care workers also expressed marked dissatisfaction with translation and interpreter services, and reported that formal interpreters tended to interfere with rapport-building and rush appointments [33]. Service providers also encountered social barriers resulting in a reluctance to share information when having a family member interpret [29, 33, 34]. However, interviews of immigrant women caregivers, service providers and policy makers in Stewart et al. [32] advocated for including interpreter services where they did not exist.

Health care and policy workers tended to feel immigrant patients did not always heed their advice, and that greater health education should be employed to combat this [33]. A service provider interviewed by Donnelly et al. [23] claimed Vietnamese immigrants tended to listen to rumours. Service providers believed patients should have greater literacy regarding health care services in Canada [33, 34].

Cultural competence has been identified as a key component in adequately serving immigrants in the health care sector. Vietnamese-speaking doctors and nurses interviewed by Donnelly et al. [23] claimed that they had cultural knowledge about their Vietnamese clients’ needs and behaviours that other service providers may not. Similarly, service providers and users in a study by Guruge et al. [29] discussed the benefits of culturally targeted care for overcoming knowledge and geographic health access barriers. These service providers felt that all professionals working with immigrant populations required more cultural training. More training was requested by health professionals interviewed in other studies [33, 34].

Among all articles, health and policy workers recognized the presence of structural barriers and the necessity for service integration to enhance immigrants’ access to health services. Transportation, childcare, eldercare support, and general service orientation were seen as services that would enable immigrants and provide incentive to access health care services [32]. In Sadavoy et al.’s [29] study regarding mental health services for ethnic seniors, both immigrants and health care workers demonstrated limited knowledge of local formal health services. In this case, immigrants were somewhat connected to community-driven supports but health care workers had low knowledge of these services. Furthermore, accessing programs for specific conditions such as post-partum depression requires ample motivation on the part of the patient, who is likely not in an optimal state of health [34]. This, compounded with the lack of common understanding of access among practitioners, equates to a very difficult situation. Overall, there is a critical disconnect within the health care structure, which is identifiable by those working within it. Looking towards solutions, Stewart et al. [32] recommends that culturally relevant, community support services should be implemented to combat the gaps that the system cannot fill, as suggested by both health care providers and immigrant participants.

Women-Focused Studies

Just under half (n = 10) of the included articles focused specifically on women, with a number of others having significantly more female participants compared to male. The reason for this gender distribution is not entirely clear, but may be due to perceived research priorities, available funding, participant priorities, available samples, and greater female contact with the health care system due to reproductive health practices.

Articles with a focus on preventative screening behaviours made up the most plentiful category regarding immigrant women: one article on mammography [27], two articles regarding Papanicolaou (Pap) testing [15, 28] and one that studied attitudes towards both of these practices combined [23]. In the case of mammography, immigrant women were shown to have a low uptake, and this is likened mostly to lack of knowledge on the topic, and burdening participants’ family for secondary needs associated with attending appointments, such as transportation, hours of service operation, and stigma regarding personal health needs [23, 27]. This knowledge barrier was related to fear and mistrust in Canadian health care, and also to unawareness of the procedure’s purpose or belief in its relevance in their lives [27].

Cultural group was found to be an influential factor in determining preventative health behaviours among immigrant women. In a study of Vietnamese immigrant women [23], several participants reported feeling like a burden to their families, particularly when family members were primarily concerned with making ends meet financially and had little time or money to devote to a low priority issue. McDonald and Kennedy [36] found that if a woman’s geographical ethnic community was large and did not support cervical cancer screening, there is less chance that woman will get a Pap test. This resonated with Gupta et al. [28], who surveyed 124 South Asian immigrants to Canada, and found that less knowledge and uptake of Pap tests was correlated with low general education, education outside Canada, and low acculturation, with acculturation having a greater impact on uptake compared to length of residency. Ahmad et al. [27] included participants who described encouraging peers to get mammograms through word of mouth in order to dispel fears associated with the procedure. Shyness and modesty was found to be a barrier for South Asian women receiving mammograms [27], but not for South Asian women regarding Pap tests [28]. Contrary to Vietnamese and South Asian sentiments, Portuguese-speaking immigrants attending a mobile health clinic spoke adamantly about the importance of preventative health practices [24].

Women’s mental health was exclusively studied only in the context of postpartum health [14, 18, 34]. Immigrant women were found to be more likely than Canadian-born women to rate their postpartum health as poor, and rated their number one barrier to accessing services as an inability to find appropriate care [18]. This was confirmed by health care providers interviewed by Teng et al. [34]. Translation services do not blend well with mental health visits, and mental illness is often stigmatized among family and community supports, creating further access barriers to appropriate treatment [34]. Like screening practices, many immigrant cultures housed a knowledge barrier regarding mental health and postpartum services [14, 18, 26, 34].

When questioned broadly about barriers to health care, several women-focused studies noted some reference to either family or community ties as taking precedence over personal health. Dependence on family was found to be heightened soon after immigrating and family-centred education was suggested as a way to improve access capabilities [27]. Furthermore, Vietnamese Canadian women rated stable household finances and caring for family members as being of higher priority than personal health care needs [23]. Finally, one study found noted that immigrants tend to have a more holistic perspective of health, with greater emphasis on social health and family values than may be offered by current Canadian health care priorities [35].

Discussion

This study included 27 articles with both qualitative and quantitative approaches and identified several barriers to immigrant health care access. The three most cited barriers to accessing health care in Canada among all studies (linguistic barriers, lack of information about how to access or navigate services, and cultural differences) represent experiences that may be specific to immigrant life. In other words, learning how to navigate a complex system in a new country where service providers and patients do not share fluency in the same language or cultural customs likely makes it hard for patients to access that system. Other often-cited barriers include financial barriers, transportation barriers, and long wait times/lists (Table 2), but these may be seen as ubiquitous experiences for many Canadians, immigrants and non-immigrants alike [12]. It is worth noting that the three most cited barriers among all studies were culturally related and potentially specific to immigrant experience; this further supports evidence that immigrants face different, additional barriers compared to non-immigrants, which likely leads to reduced access to health care.

It was surprising to note different results between quantitative studies that used primary data and quantitative studies that used secondary data. Studies that used primary data found reduced access among immigrants (vs. non-immigrants) while studies employing secondary data revealed no difference in health care access between the two groups. These discrepancies are noteworthy, and may indicate that non-purposive data collection is inadequate or inappropriate for use in determining whether immigrants experience reduced health care access in Canada. Survey questions that are not purpose-written to capture immigrant experience with regard to health care appear to amass summative data that may fail to accurately represent immigrant populations.

Using secondary data for the purpose of exploring barriers to access for immigrants may have led to ignoring some health factors. For example, in a quantitative study of health care services access specific to hepatitis C virus treatment, Giordano et al. [11] employed secondary data and found no difference between immigrants and non-immigrants. However, rate of access was determined by comparing hepatitis C treatment initiation rates for immigrants versus non-immigrants. Typically, individuals seeking treatment for hepatitis C must attend multiple appointments with health care providers and meet specific health criteria prior to initiating treatment. Events critical to understanding barriers to accessing care for hepatitis C are thus excluded from the study; once an individual is at the point of initiating treatment he/she has already navigated many barriers to access. As in many studies that employ secondary data to answer the one-dimensional question of whether immigrants have equal access to health care compared to non-immigrants, the results are overly simplistic, and may not adequately represent individual realities.

Among the studies reviewed, few took immigration categories into account when considering access barriers. Instead, research tends to lump all categories of immigrants together without distinguishing between economic immigrants, family class immigrants, and refugees. Failure to distinguish among immigration category is not surprising given that this distinction is rarely collected in data files. However, because different categories have different stipulations associated with them, individual experiences related to health care access barriers may vary depending on the immigration category one belongs to. For example, under the family class immigration program, it is the sponsor’s responsibility to support his/her spouse, dependents, or other eligible family member or members when they set foot on Canadian soil. This can create pressure for both sponsors and sponsored family members. Donnelly et al. [23] noted that family class immigrants who sponsored family members to come to Canada faced pressure to work and earn money instead of continuing education or furthering English language skills. Furthermore, in two other studies [29, 32], sponsored family class immigrants experienced decreased health care access because they did not want to burden their sponsors with additional personal needs.

Time since immigration is an important factor when considering immigrant experience [15, 37]. Typically, immigrants to Canada must meet specific health criteria in order to be eligible to enter the country, which results in what is known as the healthy immigrant effect: a population of newcomers that is generally healthier than their Canadian cohort. The healthy immigrant effect refers to a reduced need among immigrants to access health-related services during initial residency [36]. Ahmad et al. [27] captures this trend in investigating mammography access barriers to immigrant women by noting an overall lower barrier importance rating among participants who have recently immigrated to Canada. As time progresses, immigrant health typically worsens until it matches that of Canadian-born citizens. Studies that investigate immigrant access to health care should therefore consider residency time of participants, as barriers may not be as apparent among new immigrants who seek health care access less frequently than their longer-residing counterparts. Additionally, the longer individuals remain in their new country, the more likely they are to become aware of services and how to access them. One study [14] noted that initially, immigrants may be more isolated due to lack of adult relatives. With continued residency, however, individuals typically make community connections, widen their support networks, and often gain access to information through informal social processes [27, 37]. Because time since migration was rarely examined, no significant link was determined between the healthy immigrant effect and lack of differences in health access.

Another noted limitation of studies of specific cultural and linguistic groups concerns the lack of linguistic diversity among participants. Though language groups represented among individuals studied appear to be a reflection of the major origin groups of immigrants to Canada [21], minority language speakers within these groups were often excluded. Within Chinese and South Asian populations—the most studied groups—the majority of studies used fluency in a specific language as inclusion criteria for participants. This trend is potentially more impactful in studies of South Asian immigrants, as South Asia is a geographical area that encompasses several countries with varying ethno-linguistic profiles. For example, Ahmad et al. [27] required participants to speak one of Hindi, Urdu, Punjabi or English. These are among the dominant languages in South Asian countries; immigrants who speak only minority languages are thus excluded from the study. As in the above example, studies with language fluency inclusion criteria may fail to capture experiences of under-represented language and cultural groups. This is of particular interest because individuals who speak minority languages are less likely to have access to information regarding health issues or services, or to translation services thereby compounding overall service access barriers, and rendering their health care access experiences of unique value.

Immigrants claim that knowledge is best translated either among themselves through word of mouth, or by community organizations in which language is naturally present and trusting bonds exist [27]. However, while immigrant groups were very connected to their communities and aware of community services available to them [27], health professionals had low knowledge of both formal and community services that patients can utilize [37]. It would appear a communication barrier exists not just between immigrants and their health care providers, but also between health care providers and the service agencies that support immigrant health. There is no lack of communication reported among immigrant groups within their communities, and though outreach to these groups by health care workers may be optimal, it is not typically among current health care practices.

In Canada, though services for transportation, translation, cultural education and health all exist, they are largely ignorant of each other, and often do not support health access as a priority [32]. This lack of integration and continuity can make health care navigation tedious and confusing, and require high motivation and persistence on the part of the patient. McDonald and Kennedy [15] found that people who arrived in Canada as children were much more likely to receive Pap smears, and believes they may have been more exposed to Canadian values and language skills compared to recent immigrants. Canadian-born citizens and immigrants who have been in Canada since they were young may be able to self-advocate and have different expectations regarding the health care system due to increased levels of acculturation. One may argue that the expectation for new immigrants to self-advocate reflects a failure of our national health care system.

Future research priorities may consider health care providers’ knowledge of immigrant community activity pertaining to health care access and service utilization. Studying the practice and opinions of professionals such as social workers, occupational therapists and community health nurses who are most likely to have contact with community groups may be useful in providing insight as to how health care intersects with immigrant communities. Only one study [33] surveyed rehabilitation professionals. Those who tended to be involved with and had ties to community resources were often working long-term with their patients. Future studies should consider this group of professionals as key informants for providing insight into health behaviours and barriers to healthcare access among immigrant populations.

Views of health care workers and policy makers appeared to reflect the sentiments of the immigrants involved when both groups were included in the same study [23, 29, 32]. However, no studies compared and contrasted viewpoints of service providers and immigrants using an obvious systematic approach. Future research may consider studying immigrant and health care worker priorities in terms of access barriers in an explicit way. Health and cultural knowledge translation is recommended for both parties; understanding their respective priorities can create targeted education strategies.

The current research on women is mostly limited to the study of screening practices. Though this gives valuable insight into preventative health behaviours, it may be prudent to develop the existing knowledge base by examining women’s access experiences as a whole. Women participants in qualitative studies discussed their daily roles as sources of barriers to accessing health care in that individuals’ needs clashed with health system structure and expectations. Role expectations of matriarchs and caregivers were the most commonly cited as having disparate priorities compared to health care systems, such as in Guruge et al. [24]. Furthermore, there was a dearth of studies concerning the experience of male immigrants. It would be useful for further research to consider a family perspective as suggested by Ahmad et al. [37], and include experiential perspectives of men as well as women in qualitative research.

A comprehensive comparison of Canada to other countries is beyond the scope of this paper. However, research concerned with immigrant access barriers to health care in other countries indicate some similarities and differences worth discussing. For example, in the United States, immigrant health care experiences and barriers differ from Canada due to contrasts in health care structure. US-based studies are more likely to consider insurance access as a barrier, as well as racial or cultural discrimination [40–42]. A study of health care utilization by immigrants in Italy reveals reduced access to specialist services and increased usage of emergency room (ER) services compared to non-immigrants [43]. Similar to findings among Canadian studies, variations in Italian health care access are attributed to barriers in language, culture, and health care information dissemination. However, increased ER visits among immigrants also relates to the preponderance of immigrants in physically high-risk jobs in Italy, which is not necessarily the case in Canada. Similarly, a study of mental health care access among migrants in Europe indicates that access is influenced primarily by the interaction between the legal frame of the host country and individual patterns of help-seeking among migrants [44]. Comparison of studies of immigrant health care access indicates that differing political, social, and health structures and perspectives between countries effects immigrant experiences. In general, barriers to immigrant access are similar among countries—articles cite language, cultural, and informational barriers among primary concerns—but the unique systemic and social structures within countries offer differences in reasons why barriers exist.

Recommendations

Based on findings of this review, and the resultant discussion, recommendations for research are as follows:

-

Further investigation of one or more of the most cited barriers (linguistic barriers, lack of information about how to access or navigate services, and cultural differences) should be conducted with the aim of expanding information related to each barrier and determining possible solutions.

-

Solution-focused research should explore overcoming barriers through examining best practices and new policies and programming.

-

More purpose-written quantitative studies with primary data collection and analyses should be conducted to determine differences in health care access rates between immigrants and non-immigrants.

-

Further research that captures experiences of minority language speakers among dominant ethno-linguistic groups should be undertaken.

-

More research focused on time since immigration as a determining factor in experiencing access barriers to health care in Canada should be conducted.

-

Research focused on immigrants to Canada from cultural minorities beyond Chinese and South Asian groups should increase. Alongside these groups, immigrants from Haiti, Iran, Philippines, and Korea number among the top 10 permanent residents admitted to Canada from non-Western countries in 2012 [21], but few studies specific to access barriers were found for these groups.

-

Studies of immigrants are needed that explicitly and systematically differentiate between economic immigrants, family class immigrants, and refugees.

-

Studies that interview health care workers and immigrant participants regarding the same topic, and compare and contrast their responses systematically to discern perspectives on priorities would be useful.

-

Allied health professionals—particularly those who work closely with the immigrant community—possess a wealth of knowledge concerning structural barriers for immigrants, but their expertise and opinions are rarely documented in formal research. Future research should focus on allied health professionals to better understand the many points of access to health care, and discern barriers within them.

-

Conduct more research on immigrant women’s health care access experiences beyond mammography and cervical cancer screening practices and behaviours.

-

Future studies should consider the experiences of male immigrants compared to women, with an emphasis on family roles.

Limitations

As per inclusion criteria, several studies that employed census or survey data were discarded because they included children among participants. The data from children and adults were pooled and therefore not possible to extract for the purposes of this study. This limited the scope of the review by removing several secondary analyses of large data sets regarding immigrant health care access experiences.

Not including refugees and undocumented persons may have confounded results that document immigrant experiences of accessing health services. These exclusion criteria removed several relevant studies from our review in cases where removal may not have been otherwise necessary. For example, many refugees to Canada have landed status and are permitted universal health care access (equivalent to status immigrants). However, studies that included refugees were not always explicit in naming refugee status of participants, and were thus universally discarded.

References

Statistics Canada: City of Toronto Health Unit (Health Region) Health Profile, December 2013. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 82-228-XWE. Ottawa: Government of Canada; 2013. Retrieved 20 July 2014 from http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/health-sante/82-228/index.cfm?Lang=E.

Statistics Canada: Longitudinal survey of immigrants to Canada: Process, progress and prospects No. 89-611-XIE. Ottawa: Government of Canada; 2003.

Statistics Canada: Canadian Community Health Survey—Annual Component (CCHS); 2012. Retrieved 20 July 2014 from http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&SDDS=3226&lang=en&db=imdb&adm=8&dis=2.

Gushulak BD, Pottie K, Hatcher Roberts J, Torres S, DesMeules M. Canadian collaboration for immigrant and refugee health :migration and health in Canada: health in the global village. CMAJ. 2011;183(12):E952–8. doi:10.1503/cmaj.090287.

Zanchetta MS, Poureslami IM. Health literacy within the reality of immigrants’ culture and language. Can J Public Health. 2006;97:S26–30.

Koehn S, Neysmith S, Kobayashi K, Khamisa H. Revealing the shape of knowledge using an intersectionality lens: results of a scoping review on the health and health care of ethnocultural minority older adults. Ageing Soc. 2013;33(03):437–64.

Canada Health Act. Revised statutes of Canada; 1984. c. 6, s. 1. Retrieved 3 Aug 2014 from http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/PDF/C-6.pdf.

Schellenberg G, Maheux H. Immigrants’ perspectives on their first four years in Canada: highlights from three waves of the longitudinal survey of immigrants to Canada. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2008.

Ng E, Pottie K, Spitzer D. Official language proficiency and self-reported health among immigrants to Canada. Statistics Canada. Catalogue no. 82-003-XPE. Health Reports 2011; 22(4):1–8. Retrieved 5 Apr 2015 from http://scholar.google.ca/scholar?q=Official+language+proficiency+and+self-reported+health+among+immigrants+to+Canada&btnG=&hl=en&as_sdt=2005&sciodt=0%2C5&cites=7951494501265002208&scipsc=.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Giordano C, Druyts EF, Garber G, Cooper C. Evaluation of immigration status, race and language barriers on chronic hepatitis C virus infection management and treatment outcomes. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21(9):963–8.

Newbold KB. Health care use and the Canadian immigrant population. Int J Health Serv. 2009;39(3):545–65. doi:10.2190/HS.39.3.g.

Setia MS, Quesnel-Vallee A, Abrahamowicz M, Tousignant P, Lynch J. Access to health-care in Canadian immigrants: a longitudinal study of the national population health survey. Health Soc Care Community. 2011;19(1):70–9.

Sword W, Watt S, Krueger P. Postpartum health, service needs, and access to care experiences of immigrant and Canadian-born women. JOGNN. 2006;35(6):717–27. doi:10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00092.x.

McDonald JT, Kennedy S. Cervical cancer screening by immigrant and minority women in Canada. J Immigr Minor Health. 2007;9(4):323–34. doi:10.1007/s10903-007-9046-x.

Hyman I, Patychuk D, Zaidi Q, Kljujic D, Shakya Y, Rummens J, Creatore M, Vissandjee B. Self-management, health service use and information seeking for diabetes care among recent immigrants in Toronto. Chronic Dis Inj Can. 2012;33(1):12–8.

Wang L, Rosenberg M, Lo L. Ethnicity and utilization of family physicians: a case study of Mainland Chinese immigrants in Toronto, Canada. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(9):1410–22. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.06.012.

Ganann R, Sword W, Black M, Carpio B. Influence of maternal birthplace on postpartum health and health services use. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(2):223–9. doi:10.1007/s10903-011-9477-2.

Lai DW, Chau SB. Predictors of health service barriers for older Chinese immigrants in Canada. Health Soc Work. 2007;32(1):57–65.

Lai DW, Surood S. Effect of service barriers on health status of aging South Asian immigrants in Calgary, Canada. Health Soc Work. 2013;38(1):41–50.

Citizenship and Immigration Canada. Managing permanent immigration and temporary migration; 2013. Retrieved 3 Aug 2014 from http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/publications/annual-report-2013/section2.asp.

Dastjerdi M, Olson K, Ogilvie L. A study of Iranian immigrants’ experiences of accessing Canadian health care services: a grounded theory. Int J Equity Health. 2012;11:55.

Donnelly T, McKellin W, Hislop G, Long B. Socioeconomic influences on Vietnamese-Canadian women’s breast and cervical cancer prevention practices: a social determinant’s perspective. Soc Work Public Health. 2009;24(5):454–76.

Guruge S, Hunter J, Barker K, McNally MJ, Magalhães L. Immigrant women’s experiences of receiving care in a mobile health clinic. J Adv Nurs. 2012;66(2):350–9.

Ngwakongnwi E, Hemmelgarn BR, Musto R, Quan H, King-Shier KM. Experiences of French speaking immigrants and non-immigrants accessing health care services in a large Canadian city. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9(10):3755–68.

Li HZ, Browne AJ. Defining mental illness and accessing mental health services: perspectives of Asian Canadians. Can J Community Ment Health. 2000;19(1):143–60.

Ahmad F, Mahmood S, Pietkiewicz I, McDonald L, Ginsburg O. Concept mapping with South Asian immigrant women: barriers to mammography and solutions. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(2):242–50. doi:10.1007/s10903-011-9472-7.

Gupta A, Kumar A, Stewart DE. Cervical cancer screening among South Asian women in Canada: the role of education and acculturation. Health Care Women Int. 2002;23(2):123–34.

Sadavoy J, Meier R, Ong AYM. Barriers to access to mental health services for ethnic seniors: the Toronto study. Can J Psychiatry. 2004;49(3):192–9.

Gulati S, Watt L, Shaw N, Sung L, Poureslami IM, Klaassen R, Dix D, Klassen AF. Communication and language challenges experienced by Chinese and South Asian immigrant parents of children with cancer in Canada: implications for health services delivery. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58(4):572.

Klassen AF, Gulati S, Watt L, Banerjee AT, Sung L, Klaassen RJ, Dix D, Poureslami I, Shaw N. Immigrant to Canada, newcomer to childhood cancer: a qualitative study of challenges faced by immigrant parents. Psycho Oncol. 2012;21(5):558–62. doi:10.1002/pon.1963.

Stewart MJ, Neufeld A, Harrison M, Spitzer D, Hughes K, Makwarimba E. Immigrant women family caregivers in Canada: implications for policies and programmes in health and social sectors. Health Soc Care Community. 2006;14(4):329–40.

Lindsay S, King G, Klassen AF, Esses V, Stachel M. Working with immigrant families raising a child with a disability: challenges and recommendations for healthcare and community service providers. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(23):2007–17.

Teng L, Blackmore ER, Stewart DE. Healthcare worker’s perceptions of barriers to care by immigrant women with postpartum depression: An exploratory qualitative study. Arch Women Ment Health. 2007;10(3):93–101. doi:10.1007/s00737-007-0176-x.

Weerasinghe S, Mitchell T. Connection between the meaning of health and interaction with health professionals: caring for immigrant women. Health Care Women Int. 2007; 28(4):309–328. Retrieved 21 July 2014 from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cin20&AN=2009560193&site=ehost-live.

McDonald JT, Kennedy S. Insights into the ‘healthy immigrant effect’: health status and health service use of immigrants to Canada. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(8):1613–27.

Ahmad F, Jandu B, Albagli A, Angus JE, Ginsburg O. Exploring ways to overcome barriers to mammography uptake and retention among South Asian immigrant women. Health Soc Care Community. 2013;21(1):88–97.

Poureslami I, Rootman I, Doyle-Waters M, Nimmon L, FitzGerald J. Health literacy, language, and ethnicity-related factors in newcomer asthma patients to Canada: a qualitative study. J Immigr Minor Health. 2011;13(2):315–22. doi:10.1007/s10903-010-9405-x.

Reitmanova S, Gustafson DL. Primary mental health care information and services for St. John’s visible minority immigrants: gaps and opportunities. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2009;30(10):615–23.

Clough J, Lee S, Chae DH. Barriers to health care among Asian immigrants in the United States: a traditional review. J Health Care Poor Underserv. 2013;24(1):384–403.

Ku L, Matani S. Left out: immigrants’ access to health care and insurance. Health Aff. 2001;20(1):247–56.

Derose KP, Bahney BW, Lurie N, Escarce JJ. Review: immigrants and health care access, quality, and cost. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66(4):355–408.

De Luca G, Ponzo M, Andrés AR. Health care utilization by immigrants in Italy. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2013;13(1):1–31.

Lindert J, Schouler-Ocak M, Heinz A, Priebe S. Mental health, health care utilisation of migrants in Europe. Eur Psychiatry. 2008;23:14–20.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kalich, A., Heinemann, L. & Ghahari, S. A Scoping Review of Immigrant Experience of Health Care Access Barriers in Canada. J Immigrant Minority Health 18, 697–709 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-015-0237-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-015-0237-6