Abstract

The purpose of this study was to (1) construct an index to indicate the strength of a tendency to upgrade importance of life domains with lower have–want discrepancy and downgrade importance of life domains with larger have–want discrepancy for an individual (termed shifting tendency) and (2) use this index to test if shifting tendency has a positive correlation with global life satisfaction. The dataset was gain from Wu and Yao, 2006, Social Indicators Research, 79, 485–502), in which 332 undergraduate students at National Taiwan University participated in the survey. The mean age was 19.80 years (SD = 1.98). They completed a quality of life questionnaire, which contains 12 life domains. Satisfaction, importance and perceived have–want discrepancy were measured for 12 different life domains. Global life satisfaction was measured as well. Results showed that shifting tendency had a positive and significant correlation with average domain satisfaction and global life satisfaction. In addition, shifting tendency and have–want discrepancy had unique effects in predicting average domain satisfaction and global life satisfaction, suggesting that shifting tendency itself can contribute to a better QOL. The role of shifting tendency on QOL was discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the quality of life literature, many scholars define QOL as a “have–want discrepancy” of life. Campbell et al. (1976) proposed that QOL is related to the perceived discrepancy between current and wanted life status, that is, the larger discrepancy, the lower QOL. This definition was proposed by other scholars as well, such as Calman (1984), Diener et al. (1985), Locke (1969, 1976), Michalos (1985), and Shin and Johnson (1978), etc. Empirically, many studies have supported the ‘discrepancy’ perspective of QOL, such as Cohen (2000), Schulz (1995), Vermunt et al. (1989), and Welham et al. (2001), revealing that a large discrepancy between have and wanted life status is associated with lower life satisfaction. For example, in Cohen’s (2000) study, the results showed that the have–want discrepancies scores were positively correlated with the satisfaction scores for whole life and for 11 items. The correlations ranged from 0.51 to 0.79. Similar findings were also reported in other studies (e.g., Schulz 1995; Vermunt et al. 1989; Welham et al. 2001; Wu and Yao 2006a). As a result, all these findings indicated that the gap between present condition and want condition affects an individual’s satisfaction and further suggested that promoting the present condition or demoting the want standard could lead to QOL enhancement. This is a straightforward approach to enhance an individual’s QOL.

However, in addition to reducing the gap between present condition and want condition, there is another pathway to enhance an individual’s quality of life. It is to change an individual’s importance perception on life domains. Specifically, one can enhance his or her quality of life by focusing on life domains with better performance and discount life domains in worse condition. This pathway can be derived from the existing literature of Locke’s (1969, 1976) range-of-affect hypothesis, research on response shift in QOL field (e.g., Rapkin and Shwartz 2004; Sprangers and Schwartz 1999) and studies on goal adjustment process in psychology (Wrosch and Scheier 2003).

In the range-of-affect hypothesis, Locke (1969, 1976) proposed that responses of an affective evaluation (e.g., satisfaction) reflect a dual value judgment: (1) the discrepancy between what the individual wants and what he/she perceive himself/herself as getting, and (2) the importance of what is wanted to the individual, and also proposed that the level of satisfaction was influenced by the interaction of have–want discrepancy and importance. Specifically, he claimed that, given the amount of discrepancy, items with high personal importance could produce a wide affective reaction ranging from great satisfaction to great dissatisfaction. In other words, given the amount of discrepancy, range of satisfaction rating of an item is determined by the item importance. The range-of-affect hypothesis has been supported by empirical studies on job satisfaction (McFarlin et al. 1995; McFarlin and Rice 1992; Mobley and Locke 1970; Rice et al. 1991a; Rice et al. 1991b) and life satisfaction as well (Wu and Yao 2006a). In a recent study, Wu and Yao (2007) used experiments with within-subject design to show that the association between have–want discrepancy on a dimension and object satisfaction was stronger when participants viewed the dimension to be more important. In short, when participants regarded one dimension to be more important than the other dimension, they were sensitive to the gap between the have and want circumstances of that dimension and the degree of satisfaction was affected. This finding revealed that altering participants’ importance perceptions can affect satisfaction evaluations.

Thus, from this perspective, the level of satisfaction for an item is determined not only by the have–want discrepancy, but also by the importance of that item. Therefore, another pathway to enhance an individual quality of life is to attune the importance perception of life domains according to the level of have–want discrepancy of each domain, which is termed “value perception” pathway. That is, we can enhance an individual’s QOL by shifting their importance perception on life areas. This approach does not change their original ideal standards of each area, but adjusts the importance hierarchy of life areas.

Changing QOL by shifting importance perception on life domains is not a new idea in QOL research field. In fact, this phenomena has been investigated in QOL filed on the topic of “response shift”, which refers to

“a change in the meaning of one’s self-evaluation of a target construct as a result of: (a) a change in the respondent’s internal standards of measurement (scale recalibration, in psychometric terms); (b) a change in the respondent’s values (i.e. the importance of component domains constituting the target construct); or (c) a redefinition of the target construct (i.e. reconceptualization) (Sprangers and Schwartz 1999 )”.

Several studies have found that people will change the importance of life domains or re-conceptualize the meaning of life according to their health status (e.g., Rapkin 2000; Rapkin and Shwartz 2004; Schwartz et al. 1997; Jansen et al. 2000). This response shift phenomena has been used to explain why people with severe chronic illnesses report QOL equal or superior to less severely ill or healthy people (see Rapkin and Shwartz 2004; Sprangers and Schwartz 1999).

In psychology, similar notion was also discussed in goal adjustment process from the perspective of self-regulation theory. Wrosch and Scheier (2003) pointed that quality of life was related to the process of giving up unattainable goals and finding new and meaningful goals to pursue. Specifically, they argued that people who confront unattainable goals are better able to disengage from those goals and to re-engage in alternative, meaningful activities. Many empirical studies have found that people who can shift their importance perception of different life goals according to their situations have higher life satisfaction (e.g., Moskowitz et al. 1996; Rapkin 2000; Tunali and Power 1993; Wrosch and Heckhausen 1999; Wrosch et al. 2003).

Both response shift and goal adjustment process suggest that people can modify the importance hierarchy of life domains or life goals to maintain a better quality of life. Therefore, according to the range-of-affect hypothesis, response shift and goal adjustment process, it can be inferred that people who have the tendency of upgrading importance of life domains with lower discrepancy and downgrading importance of life domains with larger discrepancy (termed “shifting tendency” in this study) will have higher global life satisfaction. Although previous studies have found that people with shifting tendency had higher quality of life (e.g., Moskowitz et al. 1996; Rapkin 2000; Tunali and Power 1993; Wrosch and Heckhausen 1999; Wrosch et al. 2003), these studies only compare group difference in life satisfaction between people with and without the tendency. Actually, even among people with the tendency to shift domain importance, there are differences in the strength of the shifting tendency, and this individual difference can be meaningful and helpful for interpreting the meaning of quality of life for each person. Thus, it is desirable to find an index to indicate an individual’s shifting tendency. Furthermore, in addition to capturing individual differences, this personalized index can also be used as a research variable for further research.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was (1) construct an index to indicate the strength of shifting tendency for an individual and (2) use this index to test if shifting tendency has a positive correlation with global life satisfaction. Specifically, in order to capture the shifting tendency for an individual, the index was constructed in an intra-individual context. This is because shifting tendency is related to how an individual assigns importance weights to his/her life domains. Thus, only have–want discrepancy and importance values with an intra-individual meaning could serve this purpose, because these two values should be compared to values of other domains for the same individual, rather than other people’s values on that domain. As a result, the personalized index of shifting tendency was constructed by the association between have-discrepancy scores and importance scores across several life domains. That is, a participant had to rate level of have–want discrepancy (higher value means low discrepancy) and importance (higher value means higher importance) on several life domains, and the correlation between the discrepancy and importance rating across life domains were used to indicate the shifting tendency. This index represents the extent to which people regarded a domain with lower discrepancy as more important than other domains. After computing all participants’ value of shifting tendency, this value was correlated with global life satisfaction to see if people with higher shifting tendency would have higher global life satisfaction.

2 Method

2.1 Participants and procedure

The dataset was gain from Wu and Yao (2006a). Three hundred and thirty-two undergraduate students [63.3% female (n = 210) and 35.8% male (n = 119), three participants did not report their gender] at National Taiwan University (NTU) participated in the survey. The mean age was 19.80 years (ranging from 17 to 30, but mainly ranging from 18 to 22, std = 1.98). Students of the current sample were mainly undergraduate students and cross different years in undergraduate program. They were recruited from the pool of students taking a course of general psychology at NTU (7–10 general psychology courses were regularly provided at NTU). Information of this survey was displayed on the bulletin board at department of psychology. Students who were interested in this survey signed their names on papers, which indicated the time and location for this survey. All questionnaires were filled out during approximately 30 min and then handed in to the researchers. After completing the survey, participants were given additional points for their general psychology course.

2.2 Instruments

2.2.1 Quality of life questionnaire

Since there is no QOL instrument designed for measuring items’ satisfaction direct have–want discrepancy, and importance, a quality of life questionnaire was constructed by referencing facets form World Health Organization Quality of Life questionnaire (WHOQOL-100; the WHOQOL Group 1998, the WHOQOL-Taiwan Group 1999). Twelve facets were selected, including (1) energy and fatigue, (2) sleep and rest, (3) work capacity (with learning), (4) social support, (5) physical safety and security, (6) financial resources, (7) health and social care (accessibility and quality), (8) opportunities for acquiring new information and skills, (9) physical environment, (10) home environment, (11) transport, and (12) participation in and opportunities for recreation/leisure. They were chosen because some original items of these facets in the WHOQOL-100 assess satisfaction with those facets. In addition, some original items of these facets are close to the meaning of have–want discrepancy (e.g., “Do you have enough energy for everyday life?” for Energy and fatigue facet) according to Locke and Latham’s (1990) viewpoint on measuring have–want discrepancy. They pointed that this kind of items is conceptually equivalent to direct judgment on have–want discrepancy. Moreover, the WHOQOL-100 also contained a sub-instrument for importance ratings on the facets it contains. Therefore, using these 12 facets to assess satisfaction, have–want discrepancy, and importance would have its basis. In the first section, participants were asked to rate their satisfaction with these 12 items on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 7 (very satisfied). In order to capture enough variance on satisfaction a 7-point Likert-type scale was used. They were also asked to rate the direct have–want discrepancy on the 12 items on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from -4 (large discrepancy from the want status) to 0 (the same with want status). Finally, they were also asked to rate importance of the 12 items on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not at all important) to 5 (very important). The internal consistency (coefficient a) of the satisfaction, have–want discrepancy, importance ratings were 0.83, 0.77 and 0.83.

2.2.2 Satisfaction with life scale

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), developed by Diener et al. (1985), is a widely used measure of subjective well being. Diener et al. (1985) defined life satisfaction as conscious cognitive judgment of life in which individuals compare their life circumstances with a self-imposed standard. The scale contained five items and employed a 7-point Likert scale with higher values corresponding to a higher degree of satisfaction. The total score was calculated to represent the level of satisfaction, ranging from 5 to 35. The SWLS has shown good reliability and validity (see Pavot and Diener 1993). In Taiwan published Chinese translated version, Wu and Yao study (2006b) confirmed the single-factor structure of the SWLS-Taiwan version, and revealed the SWLS-Taiwan version was factor invariant across gender. In this study, the internal consistency (coefficient a) of the scale was 0.89.

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive statistics

Table 1 presented the mean and standard deviation of item satisfaction, discrepancy and item importance. Regarding the SWLS, the mean total score was 20.97, and standard deviation was 6.04.

Across 12 items, item satisfaction had strong correlations with item discrepancy (Pearson correlations ranged from 0.51 to 0.73). Item importance generally had low or non-significant relations with item satisfaction (Pearson correlations ranged from −0.19 to 0.50 with mean of 0.07) and item discrepancy (Pearson correlations ranged from −0.28 to 0.29 with mean of 0.05). Detail results can be seen in Wu and Yao (2006a, Tables II and III).

The SWLS had positive correlations with item satisfaction (Pearson correlations ranged from 0.25 to 0.45 with mean of 0.33) and item discrepancy (Pearson correlations ranged from 0.07 to 0.36 with mean of 0.22) across 12 items. The SWLS generally had non-significant correlations with item importance (Pearson correlations ranged from −0.03 to 0.23 with mean of 0.00) across 12 items.

3.2 Correlations among shifting tendency, average discrepancy, average satisfaction and global life satisfaction

The “shifting tendency” index was computed by correlating discrepancy scores with importance scores across all items for each individual. Then, Pearson correlation coefficients were transformed into Fisher’s Z values. Higher values indicated a stronger tendency of stressing life domains with lower discrepancy and discounting life domains with larger discrepancy. Because 22 participants rated the same importance value across 12 items, the correlation between discrepancy scores and importance scores cannot be computed, so only 309 cases had values on shifting tendency. Further, the index for average satisfaction and average discrepancy was also computed by averaging scores of satisfaction and have–want discrepancy across 12 items.

Among the correlations, first, the Pearson correlation between shifting tendency and average satisfaction was 0.23 (P < 0.01), and the Pearson correlation between shifting tendency the SWLS was 0.25 (P < 0.01). These significant and positive correlations revealed that people with stronger tendency of stressing life domains with lower discrepancy and discounting life domains with larger discrepancy have higher life satisfaction. In addition, the Pearson correlation between average discrepancy and average satisfaction was 0.56 (P < 0.01) and the Pearson correlation between average discrepancy the SWLS was 0.41 (P < 0.01), which is consistent with previous studies on discrepancy-defined QOL. Finally, shifting tendency did not have significant relation with the average discrepancy (Pearson r = 0.11, P > 0.05).

3.3 Regression analysis of average satisfaction and global life satisfaction on shifting tendency and discrepancy

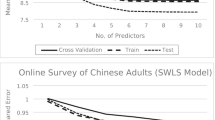

In this section, hierarchical regression analysis was conducted to investigate if the effect of shifting tendency was independent from the effect of have–want discrepancy in predicting average satisfaction and global life satisfaction. First, gender and age were first entered the model to control the effect of demographic background (Model 1), because gender (m = 1, f = 2) and age had negative relations with average discrepancy (Pearson r = −0.11, P < 0.05 and Pearson r = −0.18, P < 0.01). Then, average discrepancy was added into the model (Model 2). Finally, shifting tendency was added into the model (Model 3). It was expected that after controlling the effect of demographic background, average discrepancy would have a significant effect in predicting average satisfaction and global life satisfaction. More important, it was expected that, after controlling the effect of demographic background and average discrepancy, shifting tendency would have a unique effect in predicting average satisfaction and global life satisfaction. Because of missing value on gender and age, only 304 cases were used in the following analysis.

Table 2 presented the results of hierarchical regression analysis. In predicting average satisfaction, both gender and age did not have significant effects in Model 1. The R 2 was 0.008. Further, in Model 2, only average discrepancy (b (303) = 0.85, β = 0.64, P < 0.01) had a positive and significant effect. The R 2 was 0.394. The ΔR 2 between Model 1 and 2 was 0.386 (P < 0.01). Finally, in Model 3, both shifting tendency (b (303) = 0.31, β = 0.16, P < 0.01) and average discrepancy (b (303) = 0.83, β = 0.62, P < 0.01) had positive and significant effects. The R 2 was 0.419. The ΔR 2 between Model 2 and 3 was 0.025 (P < 0.01), indicating that shifting tendency had unique effect in predicting average satisfaction.

Similarly, in predicting global life satisfaction, both gender and age did not have significant effects in Model 1. The R 2 was 0.009. Further, in Model 2, only average discrepancy (b (303) = 4.67, β = 0.44, P < 0.01) had a positive and significant effect. The R 2 was 0.193. The ΔR 2 between Model 1 and 2 was 0.184 (P < 0.01). Finally, in Model 3, both shifting tendency (b (303) = 3.11, β = 0.20, P < 0.01) and average discrepancy (b (303) = 4.43, β = 0.42, P < 0.01) had positive and significant effects. The R 2 was 0.233. The ΔR 2 between Model 2 and 3 was 0.041 (P < 0.01), indicating that shifting tendency had unique effect in predicting global life satisfaction.

4 Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate if people who have the tendency of upgrading importance of life domains with lower discrepancy and downgrading importance of life domains with larger discrepancy would have higher life satisfaction. This hypothesis was derived from Locke’s (1969, 1976) range-of-affect hypothesis, in which a satisfaction evaluation was proposed to be influenced by have–want discrepancy and the level of importance. Accordingly, either reducing have–want discrepancy or shifting importance perception can enhance an individual’s satisfaction. This notion was supported in the current study. First, shifting tendency and have–want discrepancy had positive and significant correlations with average satisfaction and global life satisfaction. Second, regression analysis found that shifting tendency and have–want discrepancy had unique effects in predicting average satisfaction and global life satisfaction. This finding supported that reducing have–want discrepancy and shifting tendency are two independent pathways in enhancing an individual’s quality of life, suggesting that shifting tendency itself can contribute to a better QOL.

Although all findings supported the notion that shifting tendency is a positive contribution to global life satisfaction, the associations between shifting tendency and average satisfaction (r = 0.23, P < 0.01) and the SWLS (r = 0.25, P < 0.01) were not strong. This may result from the restriction of life domains chosen in the questionnaire. Originally, the survey data was used to examine the Locke’s range-of-affect hypothesis (Wu and Yao 2006a). Hence, the comprehensiveness of life domains was not the primary concern of the design of questionnaire. This restriction of life domains may result in the restriction of variance of have–want discrepancy and importance ratings across domains, and limit us to capturing the shift tendency for an individual. In addition, homogeneous sample may also be another factor for the low correlation. This is because life experiences of students will be more similar than other populations and the similarity of experience will not provide enough variance to detect the relationship between shift tendency and global life satisfaction. Moreover, this is the first study to construct the index of “shift tendency” and the sample used in the current study is only restricted on NTU students, these results need to be viewed as tentative. Therefore, in future studies, it is desirable to examine the same effect on a heterogeneous population (such as the sample of a national survey) who complete a questionnaire with comprehensive life domains, such as the Comprehensive Quality Of Life Scale Adult-Fifth Edition (ComQol-A5; Cummins 1997), the Quality of Life Inventory (Frisch 1992), or the Quality of life index (Ferrans and Powers 1985), etc., to see if the same results can be replicated.

However, why do people hold the shifting tendency? What is the role of shifting tendency on QOL? The positive effect of shifting tendency on QOL may reflect the process of positive cognitive bias, which refers to a generally positive outlook on life (Cummins and Nistico 2002). Cummins and Nistico (2002) proposed that this positive cognitive bias was rooted in the positive cognitive biases pertaining to the self. Specifically, people have a motivation to fulfill the need of self-esteem, and in order to gain success and avoid failure in domains of contingency, people regulate their goals and actions according to contingencies of self-worth (Crocker et al. 2006). Hence, in self-concept research, it has been found that people tend to stress their self-concept with better performance (e.g., Crocker et al. 2003; Hardy and Moriarty 2006), and people with strong tendency to discount the level of importance of a domain with worse self-concept had higher self-esteem (Pelham and Swann 1989). Since self-esteem was the factor that most strongly associated with life satisfaction, Cummins and Nistico (2002) argued that life satisfaction would also share the same mechanism as self-esteem on three related beliefs of self-enhancing, perceived control and optimism, which play important role to maintain a sense of positive well-being. Therefore, positive effect of shifting tendency on QOL can be realized from the motivation to achieve self-enhancement and the shifting tendency can be regarded as a characteristic of self-regulation. That is, people with higher shifting tendency would be more flexible in changing their life goals according to the external feedback for maintaining or enhancing their QOL.

For example, in a study examining the relationship between personal goals and response shifts in a longitudinal study of people with AIDS, Rapkin (2000) found that people’s reaction to life events and disease progression depended upon whether and how their goals changed. His findings revealed that there are four kinds of response shifts on QOL related to changes in personal goals and concerns. That is, patients tended to (1) have more positive reactions to events that made obtaining goals more likely, (2) have more negative reactions to events that directly interfered with obtaining goals, (3 ) have attenuated reactions to positive and negative events that were less directly relevant to goal attainment and (4) have different reactions to emergent versus entrenched health problems, depending on the implications of health problems for goal attainment (Rapkin 2000, p. 69). In Wrosch et al.’s (2003) research, they used the two strategies of “goal disengagement” and “goal reengagement” to provide direct evidence to show that people who can give up unattainable goals and find new and meaningful goals to pursue have better QOL. It is because through these two strategies, a person can (1) avoid accumulate failure experience, (2) redefine the goal as not necessary for satisfaction in life, (3) accommodate the inability of reaching the goal, and (4) reallocate resources that can be used to promote beneficial effect in other areas of life when he or she decides to disengage an unattainable goal, and also sustain the meaning of life when he or she have an alternative goal for pursuit (Wrosch et al. 2003). In brief, these findings revealed that people’s QOL are germane to the content of personal goals. And the shifting tendency would play an importance role in maintaining and enhancing QOL.

Accordingly, the role of shifting tendency on QOL can be extended and examined in future studies. For example, in investigating homeostatic phenomena on well-being, we can first use longitudinal design to investigate if shifting tendency was a stable individual characteristic. If so, then we can further to examine if people have propensity in shifting tendency would have more stable report on their QOL. Further, we also can test if this effect was related to beliefs of self-enhancing, perceived control and optimism. These examinations can empirically test the hypothesis on homeostatic well-being proposed by Cummins and Nistico (2002). Moreover, not only for homeostatic well-being in a long-term period, but we also can use the index of shifting tendency to investigate the change of well-being in a short-term period for “response shift” research. For example, we also can use the index of shifting tendency to see if the strength of tendency can be used as a predictor to estimate the amount of response shift on QOL relating to the changes in domain importance, which can facilitate the interpretation of the change score of QOL.

In summary, this study (1) provided an index for indicating the tendency for an individual to upgrade importance of life domains with lower have–want discrepancy and downgrade importance of life domains with larger have–want discrepancy for an individual and (2) showed that this shifting tendency had a positive relation with life satisfaction. In the future, the role of shifting tendency on QOL can be further extend for deeper understanding of changes in personal goals or importance perception of life domains and their relationship to QOL.

References

Calman, K. C. (1984). Quality of life of cancer patients – A hypothesis. Journal of Medical Ethics, 10, 124–127.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., & Rogers, W. L. (1976). The quality of American life: Perceptions, evaluations, and satisfaction. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Cohen, E. H. (2000). A facet theory approach to examining overall and life facetsatisfaction relationships. Social Indicators Research, 51, 223–237.

Crocker, J., Brook, A. T., Niiya, Y., & Villacorta, M. (2006). The pursuit of self-esteem: Contingencies of self-worth and self-regulation. Journal of Personality, 74, 1749–1772.

Crocker, J., Karpinski, A., Quinn, D. M., & Chase, S. (2003). When grades determine self-worth: Consequences of contingent self-worth for male and female engineering and psychology majors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 507–516.

Cummins, R. A. (1997). Comprehensive quality of life scale – Adult: Manual. Australia: Deakin University.

Cummins, R. A., & Nistico, H. (2002) Maintaining life satisfaction: The role of positive cognitive bias. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3, 37–69.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75.

Ferrans, C., & Powers, M. (1985). Quality of life index: Development and psychometric properties. Advances in Nursing Science, 8, 15–24.

Frisch, M. B. (1992). Use of the quality of life inventory in problem assessment, treatment planning for cognitive therapy of depression. In A. Freeman & F. M. Dattlio (Eds.), Comprehensive casebook of cognitive therapy (pp. 27–52). New York: Plenum Press.

Hardy, L., & Moriarty, T. (2006). Shaping self-concept: The elusive importance effect. Journal of Personality, 74, 377–402.

Jansen, S. J., Stiggelbout, A. M., Nooij, M. A., Noordijk, E. M., & Kievit, J. (2000). Response shift in quality of life measurement in early-stage breast cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. Quality of Life Research, 9, 603–615.

Locke, E. A. (1969). What is job satisfaction? Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 4, 309–336.

Locke, E. A. (1976). The nature and causes of job satisfaction. In M. D. Dunnette (Ed.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 1297–1343). Chicago: Rand McNally.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1990). A theory of goal setting and task performance. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

McFarlin, D. B., Coster, E. A., Rice, R. W., & Coopper-Alison, T. (1995). Facet importance and job satisfaction: Another look at the range of affect hypothesis. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 16, 489–502.

McFarlin, D. B., & Rice, R. W. (1992). The role of facet importance as a moderator in job satisfaction processes. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13, 41–54.

Michalos, A. C. (1985). Multiple discrepancy theory (MDT). Social Indicators Research, 16, 347–413.

Mobley, W. H., & Locke, E. A. (1970). The relationship of value importance to satisfaction. Organisational Behavior and Human Performance, 5, 463–483.

Moskowitz, J. T., Folkman, S., Collette, L., & Vittinghoff, E. (1996). Coping and mood during AIDS-related caregiving and bereavement. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 18, 49–57.

Pelham, B. W., & Swann, W. B. (1989). From self-conceptions to self-worth: On the sources and. structure of global self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 672–680.

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (1993). Review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychological Assessment, 5, 164–172.

Rapkin, B. D., & Shwartz C. E. (2004). Toward a theoretical model of quality of life appraisal: Implications of findings from studies of response shift. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 2, 14.

Rapkin, B. D. (2000). Personal goals and response shifts: Understanding the impact of illness and events on the quality of life of people living with AIDS. In C.E. Schwartz, & M. A. G. Sprangers (Eds.), Adaptation to changing health: Response shift in quality of life research. Washington D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Rice, R. W., Gentile, D. A., & McFarlin, D. B. (1991a). Facet importance and job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 31–39.

Rice, R. W., Markus, K., Moyer, R. P., & McFarlin, D. B. (1991b). Facet importance and job satisfaction: Two experimental tests of Locke's range of affect hypothesis. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 21, 1977-1987.

Schulz, W. (1995). Multiple-discrepancies theory versus resource theory. Social Indicators Research, 34, 153–169.

Schwartz, C. E., Coulthard-Morris, L., Cole, B., & Vollmer, T. (1997). The quality-of-life effects of Interferon-Beta-1b in multiple sclerosis: An Extended Q-TWiST analysis. Archives of Neurology, 54, 1475–1480.

Shin, D. C., & Johnson, D. M. (1978). Avowed happiness as an overall assessment of the quality of life. Social Indicators Research, 5, 475–492.

Sprangers, M. A. G., & Schwartz, C. E. (1999). Integrating response shift into health-related quality of life research: A theoretical model. Social Science and Medicine, 48, 1507–1515.

The WHOQOL Group (1998). The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): Development and general psychometric properties. Social Science and Medicine, 46, 1569–1585.

The WHOQOL-Taiwan Group (1999). The User’s manual of the development of the WHOQOL-100 Taiwan version (1st ed.) Taipei: National Taiwan University.

Tunali, B., & Power, T. G. (1993). Creating satisfaction: A psychological perspective on stress and coping in families of handicapped children. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 34, 945–957.

Vermunt, R., Spaans, E., & Zorge, F. (1989). Satisfaction, happiness and well-being of Dutch students. Social Indicators Research, 21, 1–33.

Welham, J., Haire, M., Mercer, D., & Stedman T. (2001). A gap approach to exploring quality of life in mental health. Quality of Life Research, 10, 421–429.

Wrosch, C., & Heckhausen, J. (1999). Control processes before and after passing a developmental deadline: Activation and deactivation of intimate relationship goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 415–427.

Wrosch, C., & Scheier, M. F. (2003). Personality and quality of life: The importance of optimism and goal adjustment. Quality of Life Research, 12, 59–72.

Wrosch, C., Scheier, M. F., Miller, G. E., Schulz, R., & Carver, C. S. (2003). Adaptive self-regulation of unattainable goals: Goal disengagement, goal re-engagement, and subjective well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 1494–1508.

Wu, C. H., & Yao, G. (2006a). Do we need to weight item satisfaction by item importance? A perspective from Locke’s range-of-affect hypothesis. Social Indicators Research, 79, 485–502.

Wu, C. H., & Yao, G. (2006b). Analysis of factorial invariance across gender in the Taiwan version of the Satisfaction with Life Scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 40, 1259–1268.

Wu, C. H., & Yao, G. (2007). Importance has been considered in satisfaction evaluation: An experimental examination of Locke’s range-of-affect hypothesis. Social Indicators Research, 81, 521–541.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, CH. Enhancing quality of life by shifting importance perception among life domains. J Happiness Stud 10, 37–47 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-007-9060-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-007-9060-7