Abstract

Pediatric clinics are uniquely positioned to assess and advocate for the health and safety of Chicago’s children in relation to accidental firearm-related injury and death. The best means of counseling families should be tailored to the individual community and patient population. We aimed to determine rates of firearm ownership and attitudes towards counseling about firearms in a community on the west side of Chicago with high rates of gun violence. An anonymous survey about gun ownership was administered at a federally qualified health center. The survey was completed by 206 adults with children less than 18 living in the home. A minority of participants (8.3%; n = 17) indicated that a gun was kept in or around the home. The majority of firearm owners reported using safe storage practices. However, just over half of the gun owners and non-gun owners had a favorable opinion of counseling about firearm safety in healthcare settings. Other strategies in addition to physician counseling will be required to promote safe firearm storage in this neighborhood with high rates of community violence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gun violence is a major issue facing Chicago, particularly in the city’s Austin neighborhood. In 2017, Austin had a homicide rate of 55.1 per 100,000—more than ten times that of the national rate [1]—and a rate of 47.7 per 100,000 for firearm-related homicides compared to Chicago’s overall rate of 18.9 per 100,000 [2]. Across the United States, firearm-related deaths represent a leading cause of death for children, including homicide, suicide, and accidental injury [3]. Compared to children in other high-income countries, children in the United States ages 5–14 years were ten times more likely to die from unintentional firearm injuries, which may be related to accessibility of firearms [3]. Having a firearm in the home increases the risk of homicide by a factor of three and the risk of accidental death by a factor of four [4, 5]. There is decreased risk of injury and death when guns are stored unloaded and locked with ammunition stored separately from the firearm [6].

The American Association of Pediatrics recommends incorporating firearm screening and safety counseling into routine anticipatory guidance [3]. However, debate exists over the best methods of providing this counseling and whether such counseling is appropriate or ethical [7, 8].

Given the high rate of firearm related injuries and deaths in the Austin neighborhood, we aimed to gather more information about the rates of firearm storage in homes with children and attitudes towards counseling in this population.

Methods

Study Design

We performed a convenience sampling of adults 18 years and older in the waiting area of a federally qualified health center in Austin between June and October 2017. This research study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at Northwestern University. Participants were approached and asked to complete an anonymous survey about gun ownership if they had children less than 18 years old living in the home. Basic demographic information, including age and gender, was collected. The survey also collected information on gun ownership, gun storage practices, and attitudes towards counseling about gun safety.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the overall population and the subset of the population that indicated they had gun(s) in the home. A Likert scale was used to assess each participant’s attitude on health professionals discussing guns with patients.

Results

Two hundred and six participants with at least one child less than 18 years of age living in the home completed the survey. The mean age of participants was 34.8 years; 81.1% of the participants identified as female. The mean number of children per household was 2, with 29.9% of respondents having one or more children 11 years or older (Table 1).

Among participants, 8.3% (n = 17) indicated that a gun was kept in or around the home. In households with at least one firearm, a majority of the children in the home were 4 years or older (74.4%). Nearly three quarters (70%; n = 12) of gun owners reported storing their guns locked with over half (n = 8) reporting storing their guns locked and unloaded. Only one respondent reported not securing gun and keeping it loaded (Table 2).

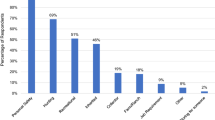

Over half of gun owners (52.9%) and 54.8% of non-gun owners always or usually thought it was appropriate for health care professionals to talk to their patients about gun safety (Fig. 1).

Discussion

In Chicago and throughout the United States, gun violence is a major public health issue [9]. Shootings disproportionately affect racial minority neighborhoods of low socioeconomic status [3, 10], such as the one in which this study was conducted. While multiple studies have shown that the safest environment for a child is a home without a gun [5, 11,12,13], and a majority of Americans feel that more guns make their communities less safe [14], many Americans in urban and rural communities keep guns in the home. Guns in the home increase the risk for homicide, suicide, and accidental injury in children [4, 5].

Given that the presence of firearms in the home is a significant risk factor for firearm-related injury and death in children, it is encouraging that a minority of participants indicated the presence of firearms in the home. It is further encouraging that the majority of gun owners participating endorsed safe storage practices. However, our data likely represents an underestimation given that nearly 40% of US households have at least one firearm [15, 16] and given the burden of gun violence in the Austin community. Moreover, in one nationally-representative online survey of gun owners, only 46% of gun owners reported safe firearm storage [17], which was different from our findings.

In this study, over half of participants with firearms in the home indicated “Personal safety/protection” as a reason for keeping a firearm. National surveys of firearm owners have found that people were more likely to keep their guns loaded if this were the primary reason for gun ownership [18, 19]. While our survey did not reproduce these findings, this represents an important area to address in firearm counseling.

Nearly one half of participants in our survey had negative opinions towards firearm counseling in pediatric clinics, which may represent a barrier to effective counseling. It is important for providers to address concerns regarding firearm counseling and acknowledge the social and cultural attitudes towards firearms that may be different from other areas of pediatric anticipatory guidance.

Given these attitudes, additional strategies to prevent firearm injuries beyond counseling in the healthcare setting warrant further investigation. This includes community-based interventions, firearm buyback programs, and firearm safety technology, such as trigger locks. In a meta-analysis of primary prevention strategies aimed at preventing injury and death among children and adolescents, Ngo et al. found that robust data on the efficacy of primary prevention programs is lacking [20]. Further research is needed to assess the efficacy of such interventions.

This study was limited by a small sample size and small number of participants indicating the presence of firearms in the home. A majority of participants were female, which may not be representative of the population. The use of convenience sampling is a further limitation. While this study aimed to assess the rate of firearm storage in a child’s primary residence, it did not assess rates in other locations where children may be exposed to firearms, such as in schools, friends’ homes, or homes of non-primary caregivers.

Parents and guardians can take simple steps to ensure their children do not gain access to any firearms stored in the home. Firearms should be kept unloaded with the firearm locked up separately from the ammunition. Pediatricians play an important role in disseminating this information to families; however, special attention must be paid to reasons for gun ownership and attitudes towards counseling.

References

FBI: Uniform Crime Reporting. (2017). Retrieved from https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2017/crime-in-the-u.s.-2017/topic-pages/murder.

Chicago Health Atlas. (2017). Retrieved from https://www.chicagohealthatlas.org/indicators.

Dowd, M. D., & Sege, R. D. (2012). Firearm-related injuries affecting the pediatric population. Pediatrics,130(5), e1416–1423.

Kellermann, A. L., Somes, G., Rivara, F. P., Lee, R. K., & Banton, J. G. (1998). Injuries and deaths due to firearms in the home. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery,45(2), 263–267.

Wiebe, D. J. (2003). Firearms in US homes as a risk factor for unintentional gunshot fatality. Accident Analysis and Prevention,35(5), 711–716.

Grossman, D. C., Mueller, B. A., Riedy, C., et al. (2005). Gun storage practices and risk of youth suicide and unintentional firearm injuries. JAMA,293(6), 707–714.

Parent, B. (2016). Physicians asking patients about guns: Promoting patient safety, respecting patient rights. Journal of General Internal Medicine,31(10), 1242–1245.

Betz, M. E., Azrael, D., Barber, C., & Miller, M. (2016). Public opinion regarding whether speaking with patients about firearms is appropriate: Results of a national survey. Annals of Internal Medicine,165(8), 543–550.

Bryan, M. (2016). Gun deaths in Chicago reach startling number as year closes, NPR. Retrieved from http://www.npr.org/2016/12/28/506505382/gun-deaths-in-chicago-reach-startling-number-as-year-closes.

Tribune, C. (2018). Chicago shooting victims. Retrieved from http://crime.chicagotribune.com/chicago/shootings/.

Patterson, P. J., & Smith, L. R. (1987). Firearms in the home and child safety. American Journal of Diseases of Children,141(2), 221–223.

Anglemyer, A., Horvath, T., & Rutherford, G. (2014). The accessibility of firearms and risk for suicide and homicide victimization among household members: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine,160(2), 101–110.

Miller, M., Warren, M., Hemenway, D., & Azrael, D. (2015). Firearms and suicide in US cities. Injury Prevention,21(e1), e116–119.

Miller, M., Azrael, D., & Hemenway, D. (2000). Community firearms, community fear. Epidemiology,11(6), 709–714.

Hepburn, L., Miller, M., Azrael, D., & Hemenway, D. (2007). The US gun stock: Results from the 2004 national firearms survey. Injury Prevention,13(1), 15–19.

Smith, T., & Son, J. (2015). Trends in gun ownership in the United States, 1972–2014. General social survey final report. NORC, Chicago, IL.

Crifasi, C. K., Doucette, M. L., McGinty, E. E., Webster, D. W., & Barry, C. L. (2018). Storage practices of US gun owners in 2016. American Journal of Public Health,108(4), 532–537.

Weil, D. S., & Hemenway, D. (1992). Loaded guns in the home. Analysis of a national random survey of gun owners. JAMA,267(22), 3033–3037.

Hemenway, D., Solnick, S. J., & Azrael, D. R. (1995). Firearm training and storage. JAMA,273(1), 46–50.

Ngo, Q. M., Sigel, E., Moon, A., et al. (2019). State of the science: A scoping review of primary prevention of firearm injuries among children and adolescents. Journal of Behavioral Medicine,42(4), 811–829.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This project did not receive any external funding.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Haser, G., Yousuf, S., Turnock, B. et al. Promoting Safe Firearm Storage in an Urban Neighborhood: The Views of Parents Concerning the Role of Health Care Providers. J Community Health 45, 338–341 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-019-00748-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-019-00748-0