Abstract

The American Academy of Pediatrics is unequivocal in its recommendations regarding firearms and children: “The safest home for children and teens is one without guns” [1]. However, pediatric clinicians recognize that one-third of the children in the United States live in homes with guns, and in some states, over two-thirds of households own guns [2, 3]. Therefore, clinicians need to connect with families within the context of their beliefs around gun ownership. This will facilitate providing effective guidance that maximizes the safety of all children within their homes, whether the children are their own or visitors.

References for Abstract

-

1.

Healthychildren.org, American Academy Pediatrics; Gun safety and children [Internet]. Chicago; 2019. Available from: https://www.aap.org/en-us/ImagesGen/Gun Safety 7 x 12 half English_FINAL.jpg

-

2.

Azrael D, Cohen J, Salhi C, Miller M. Firearm storage in gun-owning households with children: results of a 2015 national survey. J Urban Health. 2018;95(3):295–304.

-

3.

Schuster MA, Franke TM, Bastian AM, Sor S, Halfon N. Firearm storage patterns in US homes with children. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(4):588–94.

Community leaders implore parents to ask: Are there guns in the house?

By Rachel Dissell

Updated January 12, 2019; Posted August 23, 2012. The Plain Dealer

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Personal Vignette

I widened my stance, braced the shotgun against my shoulder, aimed down the barrel, and pulled the trigger….

I was 17 years old, at a classmate’s house to discuss starting an asphalt driveway resurfacing business. Before we began, he invited me outdoors to do something I had never done before: fire a shotgun. At an old microwave. In the middle of the afternoon with no one else home. The noise and kickback were incredible, and my shot wildly veered into the woods. He laughed and proceeded to shoot the microwave multiple times….

All children in the United States (US), from toddlers through adolescents, have the potential for exposure to firearms. Since the 9/11 attack, which claimed 2977 victims, there have been a staggering 49,568 children, 0–19 years old, killed and another 264,423 injured by firearms in the US [1]. These firearm deaths and injuries occurred just between 2002 and 2018. On the current trajectory of pediatric firearm deaths, over 3500 children will be killed by firearms each year—this is equivalent to an entire school bus of children dying every 9 days throughout the year.

In the US, there are an estimated 350–400 million firearms, more than one for every person in the country. And these are only estimates for no one really knows how many guns there are in the US. No national data are collected about firearm sales and few states require registration of firearms. Though the distribution of firearms throughout the US varies, even the states with lowest firearm ownership (e.g., Hawaii and Massachusetts) still have children who needlessly die by guns every year. For this reason, it is imperative that pediatric clinicians make screening and recommendations for safe firearm storage a part of their daily practice.

2 Which Families Are Most Likely to Own Guns?

National and state-wide data on firearm ownership are limited by the fact that the majority of states do not require firearm registration. This limits research investigating the demographics of those who own guns. In fact, the most recent large-scale national data on gun ownership, with more than 200,000 surveyed, were collected via the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) in 2004. Back then, the District of Columbia and state-level firearm ownership ranged from 5.2% in the District of Columbia to 62.8% in Wyoming [2]. Using a well-described methodology for proxy estimation of household firearm ownership rates [3], 1980 and 2016 data estimates suggest that ownership rates have decreased moderately over time. In 2016, the lowest firearm ownership rate of 9% was in Hawaii, New Jersey, and Massachusetts and the highest rate of 65% was in Montana (Fig. 7.1 and Chap. 1, Table 1.1).

Data from state-level estimates of household firearm ownership, RAND 2020 [6]

Ownership rates significantly vary across the US by region and urbanicity, as well as by the individual characteristics of the owner. From a 2014 national survey of 1711 people, in urban areas, 14.8% of individuals had a gun in the household, while in rural areas, 55.9% had guns. Overall, 35.1% of males owned guns while only 11.7% of females owned guns. By age, only 14.0% of adults less than 35 years old owned guns versus 30.4% over the age of 65 years. White ownership was 39.0%, Black ownership was 18.1%, and Hispanic ownership was 15.2%. Among the low-income households (<$25000/year), 18.0% owned a gun, whereas in high-income households (>$90000/year), 44.0% owned a gun [4]. By political affiliation, 41% of Republicans, 36% of independents, and 16% of Democrats owned a gun [5]. Data from PEW and Gallup in 2019 support these general numbers.

Though the breakdown of firearm ownership has been relatively stable for many years, gun sales dramatically increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, ownership among different groups may have begun to shift. In March 2020 alone, over 2.5 million guns, including 1.5 million handguns, were sold, an all-time high [6, 7]. By November 2020, an estimated 20 million firearms were sold in the US, beating a former high of 16.6 million guns sold in 2016. Reports from gun store owners suggest that many of these guns were purchased by first-time owners.

Among the 37.4 million households with children in the US, it is estimated that 34% (12.7 million households) have one or more firearms. Among these households, 21% store at least one firearm in the least safe manner, namely loaded and unlocked, and another 50% store a firearm either loaded and locked, or unloaded and unlocked [8]. These unsafe storage practices place 4.5 million and 11.4 million children, respectively, at higher risk of access to and use of a gun, compared to children living in homes either without guns or guns stored in the safest manner. The safest manner of storage, as endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), is “If you own a firearm, it should be stored unloaded, locked up (lock box, cable lock, or firearm safe), with the ammunition stored separately [and locked]” [9].

Variation also exists in rates of how guns are stored in the home. Thirty percent of firearm owners in the South store firearms loaded and unlocked versus 14–18% in other regions of the US. Urban and rural owners do not differ in rates of unsafe firearm storage. Female owners unsafely store firearms at nearly twice the rate of males (31% vs. 17%). There are no significant variations in unsafe firearm storage by age, race/ethnicity, education, income, or political affiliation. However, the odds of handgun owners storing them unsafely are fourfold higher than those who only own long guns (e.g., rifles) (27% vs. 5%), and the odds of those owning a gun for protection storing them unsafely are sevenfold higher (79% vs. 25%) than other types of gun owners (e.g., hunters) [8].

3 How Dangerous Is It Really to Have a Gun in the Home?

Unequivocally, having a gun in the home increases the likelihood that a child will be injured or killed by a gun. Household firearms are a known and modifiable risk factor for death by suicide. People who purchase handguns have a 22-fold higher rate of gun suicide within the first year compared to those who did not purchase a handgun [10]. Among males, for every 10% increase in household firearm ownership rates at the state level, there is an increase of firearm suicides of 3.1 per 100,000. In comparison, among females there is an increase of firearm suicides of 0.4 per 100,000 [11]. While these relative increases may seem small, to illustrate the magnitude of this difference, one needs to only look at the ownership rates and firearm fatality rates in Massachusetts vs. Wyoming [1, 3] (Fig. 7.2).

For over 30 years, studies have shown that access to a gun in the home is associated with increased rates of adolescent suicide [12]. Overall, the risk of suicide for any member of the household where firearms are kept is 2–10 times that of homes without firearms [13, 14]. When a firearm is used in a pediatric suicide, 75% of the time the firearm is owned by the parent or the child themselves [15]. Likewise, in unintentional firearm deaths, the gun used in the shooting originated from the parent 56% of the time with young children and 17% of the time in older teenagers. Among older teenagers, in 43% of the unintentional deaths, the gun was owned by the shooter themselves [15]. These data speak not only to the importance of protecting children from firearms within their own homes , but also of encouraging parents to talk about firearm storage with the owners of the homes their children visit, whether it is a relative, friend, or neighbor.

4 Does Storage Matter?

Firearm storage matters – each element of safe storage, namely (1) storing a gun locked, (2) unloaded, (3) storing the ammunition locked, and (4) storing the ammunition separate from the gun, is associated with lower rates of both adolescent suicide and unintentional injuries and fatalities [16]. A simulation model of safe storage suggests that annually up to 135 pediatric lives could be saved and 323 pediatric firearm injuries prevented if even just 20% of parents who currently store their guns unlocked shifted and stored them safely [17].

It is important to realize, and a point to discuss with patients and families, that many gun owners do not store the ammunition locked up; and therefore, a child or young adult with suicidal intent can readily access and load the gun themselves. An analysis of data from the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) looking at the relationship between gun storage and homicides, suicides, and unintentional deaths shows not only the dangers of storing guns loaded and unlocked, but in the case of suicide, unloaded and unlocked as well. The gun was stored loaded and unlocked in unintentional deaths of children aged 10–14 years and 15–19 years 75% and 66% of the time , respectively. For suicides among children of 10–14 years and 15–19 years, the gun was stored loaded and unlocked (42% and 35%, respectively) or unloaded and unlocked (38% and 39%, respectively) [15]. Added together for pediatric suicides, this data translates to ready access to the gun and ammunition occurred 80% of the time for 10–14 years old and 74% of the time for 15–19 years old.

5 What Do Clinicians Believe and Do?

Pediatric primary care clinicians are the number one source of medical contact with children and adolescents and their caregivers. Multiple physician groups, including the AAP [18], the National Academy of Medicine [19], and others recommend that clinicians screen patients for access to firearms and provide concrete recommendations for safe storage if there is a firearm in the home. The AAP’s Bright Futures guidelines specifically mention firearm screening and counseling starting at the newborn visit and moving every year through adolescence. What adjusts overtime are the details regarding the content of this counseling. This is because the type and intent of firearm injury change based on the developmental stage of the child or adolescent. For families of younger children, counseling should focus on preventing unintentional injuries, while for teenagers, counseling should focus on suicide prevention . An important universal recommendation that pediatric clinicians can make for all ages includes ideally not having a gun in the home. However, if a gun is present in the home, clinicians should recommend that it is necessary to store all guns unloaded, locked, and separated from the locked ammunition. In addition, parents of preschool and school-aged children should be advised to ask about firearms in the homes their children visit. Pediatric clinicians should speak to adolescents directly about their exposure to and carrying of guns at school/outside of the home, and parents of adolescents should be advised to talk with their teenagers about guns [20].

For the past 30 years, pediatricians have espoused their beliefs that counseling families about firearm safety is important and should be a part of pediatric primary care anticipatory guidance [21]. However, when it comes to firearm counseling, beliefs do not always translate into actions. Though pediatricians recognize the inherent risks associated with guns in the home, they often do not provide routine firearm counseling with any consistency. In a study of Maryland pediatricians in 1992, only 30% said that they had ever spoken to a family about firearm safety, and only 7% counseled at least 50% of their patients [21]. In a survey of pediatricians and family medicine doctors in Washington, only 20% and 8% of practitioners, respectively, counseled more than 5% of their patients about firearms [22]. Fast forward to 2019 and not much has changed – a study of pediatric residents at three different programs showed that 50% essentially never counseled about firearms, and only 15% of them counseled more than 50% of their patients during well-child visits [23]. Rest assured, pediatricians do not differ from their adult counterparts – among internists, 58% report never asking their patients if they have a gun in the home, 77% never discuss ways to reduce the risk for gun-related injury or death, and 62% never discuss the importance of keeping guns in the home away from children [24].

The reasons for the lack of counseling are broad. Some clinicians report fears of confrontation or upsetting their patients and/or caregivers. Others report a lack of comfort with counseling, a lack of training, or uncertainty about what to say. In a study of pediatric residents’ beliefs and practices, the majority felt comfortable counseling about gun safety and gun storage , but only 15% were comfortable discussing trigger locks and other safety devices [23]. Others report skepticism that counseling is effective. Uncertainty about physician gag laws and concerns about restrictions on what can be recorded discourage some clinicians (see Chap. 13; spoiler alert – all clinicians in every state can discuss firearms with patients and families). Many report that the significant limitation of time available during the well-child visit impedes these discussions. Some clinicians do not believe that firearms are a major part of their patient’s lives; therefore, the counseling does not apply to them. A small percentage of clinicians do not believe that firearm counseling is a part of their work. For some gun owning (and non-gun owning) physicians, their beliefs around the Second Amendment may temper their willingness to have these conversations [23,24,26].

6 What Do Parents Believe About Firearms and Their Children?

One challenge that exists is in parents’ perceptions about firearm safety and risks . Though historically most gun owners used firearms for hunting, today over two-thirds of firearm owners overall, and 75% of handgun owners, keep them for personal safety [5]. Major shifts in the belief about the safety of a firearm in the home have occurred in the past two decades. Gallup polls have asked the following question over time “Do you think having a gun in the house makes it a safer place to be or a more dangerous place to be?” In 2000, a third answered “safer” and half “more dangerous.” By 2014, the numbers had flipped (Fig. 7.3) [27].

Do you think having a gun in the house makes it a safer place to be or a more dangerous place to be? [27]

When it comes to guns and children, 75% of gun-owning parents believe that their 4- to 12-year-old children can tell the difference between toy guns and real guns and nearly a quarter believe their child could be trusted with a loaded gun. Even among non-gun owning parents, over half believe their child could differentiate toy versus real guns and 14% could trust their child with a loaded gun. Three quarters of all parents felt their child would not touch a gun if they found one [28].

Reality demonstrates that children have the opposite kind of behavior when they find a gun. Boys in particular appear to have an affinity for guns. A study of 29 small groups of boys 8–12 years old demonstrated that when these boys found a real gun, 74% of them handled the gun and 48% pulled the trigger [29]. This occurred despite the training 90% of these boys had completed called the Eddie Eagle Gunsafe® safety program advocated by the National Rifle Association [30]. This program instructs children with the following: “If you see a gun, (1) Stop, (2) Don’t touch, (3) Run away, (4) Tell a grownup.” Good advice, but based on this study, it is unfortunately unlikely to be followed by the majority of boys.

7 What Do Parents Believe About Health Clinicians Talking About Firearms?

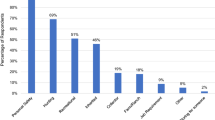

The vast majority of patients and parents believe that it is ok to for their physician to ask about firearms in the household and to provide firearm safety education. In a study of over 1200 parents, 66% thought a pediatrician should ask about the presence of guns in the household, including 58% of parents who own guns. Seventy five percent of parents felt that pediatricians should advise parents on the safest ways to store firearms in the home, including 71% of gun-owning parents. When asked “If a pediatrician advised me to not have any firearms in the home for child safety, I would…” – the responses were as follows (overall/gun-owning parents): think it over (48%/49%), follow the advice (35%/14%), ignore the advice (11%/22%), and be offended by the advice (8%/14%) [31]. When it comes to talking to other families about guns in their homes, a study of caregivers who had received teaching about ASK (Asking Saves Kids campaign), 96% of caregivers felt that doctors should provide ASK education [32].

Multiple focus groups of gun owners provide insight into some of the beliefs and concerns gun owners have regarding these conversations with their clinicians. Reason for ownership (hunting versus protection) plays a major role in overall perceptions of these conversations. Many owners view the overall risk for firearm injury as low. In truth, this is a matter of opinion with fatality rates around 7.5/100,000 for 10- to 19-year-old children. To place these numbers in context, this rate is actually higher than motor vehicle fatality rates (6.9/100,000), and yet physician advice about seatbelts and safe driving is typically acceptable and expected.

Many gun owners believe that safe firearm storage interferes with personal protection needs, especially for handguns. Devices like trigger locks are considered a nuisance and rarely used. Many parents feel confident in their youth’s ability to handle guns safely and do not believe that safe storage would deter suicide. Though gun owners state they are willing to talk to their doctors about firearms, they prefer safe storage education from members of the military or law enforcement [33]. In a nationally representative survey of 1444 gun owners, only 19% rated physicians as excellent or good messengers to teach gun owners about safe gun storage [34].

However, broadly speaking, adult patients are likely more willing to discuss firearms with their doctor than the above data would suggest. In a national survey, nearly 4000 adults were asked, “In general, would you think it is never, sometimes , usually, or always appropriate for physicians and other health professionals to talk to their patients about firearms?” Seventy percent of non-firearm owners and 54% of firearm owners said it is at least sometimes appropriate for clinicians to talk to patients about firearm [35].

8 Can You Talk to Your Patients About Guns?

As of 2020, a health care clinician can talk about firearms with their patient in all 50 states. There was a physician gag law in place in Florida from 2011 to 2017, which was ultimately overturned. See Chap. 13 for further details. Twelve other states have attempted to pass laws restricting firearm conversations. Minnesota, Missouri, and Montana have restrictions against laws requiring physicians to ask about guns, but do not prevent the conversation itself. They also have specific limitations on how information can be collected and stored (i.e., standardized questionnaires/data forms).

A health care clinician can document the question asked and the response about firearm ownership and storage in all states. Clinicians can disclose about firearm ownership if there is an imminent concern about safety under the HIPAA exemption stating disclosure “is necessary to prevent or lessen a serious and imminent threat to the health or safety of a person or the public….” In addition, HIPAA regulations state, “No federal law prevents health care providers from warning law enforcement authorities about threats of violence” [36].

9 Storage Options

Understanding storage options for firearms is key to moving the conversation from generalizations about safety to actionable change.

As discussed above, storage of firearms outside of the home, and off of the property, is the safest way to keep a gun. Though this is not an option for someone who keeps their gun for home protection, it is an option for hunters and collectors and should be discussed within that context.

Cable/trigger locks : A cable lock blocks either the barrel of the gun and/or the ammunition by preventing a detachable magazine, which holds the bullets, from being attached to the gun. A trigger lock is a two-piece lock that fits over a gun’s trigger and trigger guard to prevent a gun from being fired. They are available in versions with keys or combinations and are designed for use on unloaded guns. The cost of these items ranges from $10 to $50. Among some experts, there are concerns that trigger locks can potentially be disabled. Gun owners may find them cumbersome.

Lock box/safe: Lock boxes and gun safes provide the same type of security, namely a place to store a firearm in a locked, ideally unloaded, location. Companies selling these recommend that the lock box should be securely bolted to prevent theft. Lock boxes and safes can be accessed multiple ways including keys, combinations, keypad, biometrics, and radio-frequency indentification (RFID) devices. Makers of biometric access devices state the boxes/safes can be opened in seconds. Safes are typically used for multiple guns or long guns. Costs range from $25 to $350 for lock boxes and $200–$2500 for safes.

Personalized “smart” guns: These firearms are designed to recognize authorized users. The "smart gun" may recognize the authorized user via biometrics embedded into the grip and/or trigger, or they may recognize RFID bracelets or rings that the user wears. These are currently not readily available in the US but have been under development for over a decade and are available in other parts of the world. Please see Chap. 12 for further details.

Transfer possession : An individual may transfer their firearm to another person for safe keeping. This may occur in times of particular concern such as suicidality or may be done at baseline, for instance when there are children in the home. Firearms may be transferred to relatives, non-relatives, police stations, firearm dealers, and shooting ranges. Different states have restrictions on who may receive a firearm; this is especially important in states that require registration of firearms and in states that require background checks beyond the federal laws which only mandate background checks when firearms are sold by legal firearm dealers [37]. There are also some states, which provide regulations and protections related to the transfer back of the firearm, so that an individual who returns a firearm to the owner is not held liable should an injury or fatality occur [38, 39].

Extreme Risk Protection Orders : An Extreme Risk Protection Order (ERPO) , also known as a red flag law , is an order from a judge that suspends a person’s license to possess or carry a gun. This typically occurs when the family petitions to have a firearm removed from an individual because they believe the individual is at risk of hurting themselves or others. In some states, law enforcement, mental health providers, and others can petition to have a firearm temporarily removed. The immediate removal of the firearm is very brief, 2–3 days, and then an in-person hearing typically determines whether the firearm should be removed for a period typically up to 1 year. As of 2020, 20 states had ERPO laws (Fig. 7.4). Please see Chap. 14 for further details.

10 What Interventions Work?

There have been 12 studies examining how to intervene with parents and/or adolescents to lower the risk of unsafe firearm exposure or harm [40]. Six of these studies were randomized control trials (RCT). Unfortunately, they are all relatively small and many lack high-quality research methods. The two studies with the highest quality scores were found to improve firearm safety and are described in detail below.

In one RCT involving 124 pediatric practices and a total of 4890 participants, parents/primary caregivers received an intervention that included information about patient-family behavior and concerns related to media use, discipline, and children’s exposure to firearms. Practitioners were trained in and provided motivational interviews and instructed families about the use of firearm cable locks and safe storage. Practitioners offered free cable locks to parents who lived in homes with children where guns were stored. Of the families, 470 reported gun ownership. Among these parents, reported use of cable locks at 6-month follow-up increased from 58% to 68% in the intervention group and decreased from 66% to 54% in the control group (odds ratio of increased usage 2.0, P = 0.001) [41].

The second RCT involved adolescents who experienced either intentional or unintentional injuries requiring hospitalization at a level 1 trauma center in Seattle, WA. After risk assessment, patients randomized to the intervention arm received care from a social worker and nurse practitioner team. The intervention included care management and motivational interviewing targeting risk behaviors and substance use, as well as pharmacotherapy and cognitive behavioral therapy elements targeting symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression. Among the 120 randomized adolescents followed for 12 months, 33% reported carrying a weapon at baseline. Carrying dropped from 35% to 7% in the intervention group and 31% to 21% in the usual care group (relative risk 0.31, 95% CI 0.11, 0.90) [42].

Though not as rigorous as the above studies, a quasi-experimental evaluation of a single, in-person message delivered to patients about firearm storage provides an intervention that can readily be incorporated into practices. In two family medicine clinics, 1233 patients were screened for firearm ownership by a nurse after asking basic demographic information. The question was “Does anyone living in your home own a gun?” A total of 156 patients reported guns in their household and were enrolled in the study. Those in the counseling group received verbal counseling from their physician who provided the following advice: “Having a loaded or unlocked gun in your house increases the risk of injury or death to family members, whether by accident or on purpose. I urge you to store your unloaded guns in a locked drawer or cabinet, and out of reach of children.” By 2 or 3 months follow-up, among those in the intervention groups, 64% had made a safe firearm storage change, while only 33% in the control group had make a safe change (P = 0.02); the odds of making a safe change was 3.0 [43].

11 Implementation of Interventions

What does it take to implement these interventions? Analysis of stakeholders’ perspectives on implementing firearm safety interventions in pediatrics emphasizes the importance of leveraging existing infrastructures such as electronic medical records as well as brevity of the intervention [44]. Interventions requiring the distribution of firearm locks or lock boxes, though desirable, pose complications of storage space within a practice, cost expenditures and lack of reimbursement, as well as questions of efficacy. But if your clinic is committed to handing out safety devices, families appear to be receptive.

Concerns exist about the appropriateness of talking to parents; the concern of one pediatrician in particular captures this well, “So we’re talking about coming into a culture trying to do a very reasonable urban intervention on a mostly rural population that is politically very, very, very charged around gun rights.” To lower clinician burden, the notion of screening outside of the examination room (e.g., the waiting room) bundled with other safety questions may be more feasible and acceptable. To make this work within a clinic, staff would require education and training and the availability of hard copies of materials to hand to families could be useful [44].

Teaching kids how to safely use a gun within the context of target shooting or hunting is clearly an important task. However, no known data exist showing that teaching children not to touch a gun and to tell an adult if they see a gun actually works. The Eddie Eagle program mentioned above and the STAR (Straight Talk About Risks) gun-safety programs have not been shown to prevent children from handling guns.

12 A Framework for Clinicians to Provide Firearm Safety Counseling

In 2017, the Massachusetts Attorney General’s office assembled a collection of pediatricians, psychiatrists, emergency physicians, public health specialists , law enforcement, lawyers, and other professionals to develop guidelines on how to talk to patients about firearms. The freely available pamphlet “Talking to Patients about Gun Safety” [45], http://www.massmed.org/firearmguidanceforproviders/, emphasizes the following key points (see Fig. 7.5):

-

1.

Most gun owners are knowledgeable and committed to gun safety

-

2.

Focus on health

-

3.

Provide context for the questions

-

4.

Make sure the questions are not accusatory

-

5.

Start with open-ended questions to avoid sounding judgmental (e.g., “Do you have any concerns about the accessibility of your gun?” instead of “Is your gun safely secured?”)

-

6.

Meet patients where they are. Where there is a risk, brainstorm together harm reduction measures

Guide to talking to patients about firearms. From: Talking to Patients About Gun Safety [Internet]. Boston; 2017. Available from: http://www.massmed.org/firearmguidanceforproviders/

The same group created freely available information sheets that can be given to families entitled “Gun Safety and Your Health, ” http://www.massmed.org/firearmguidanceforpatients/ (see Fig. 7.6) [46]. Beyond the information about gun safety and health, and the recommendations about safe firearm storage, the pamphlet also discusses how to dispose of an unwanted gun. Options for gun disposal include sale to a dealer, surrender the gun to the police, gun buyback programs, which are sponsored annually, and donation to law enforcement and gun safety training programs.

Handout to give to patients about firearm safety. From: Gun Safety and Your Health [Internet]. Boston; 2017. Available from: http://www.massmed.org/firearmguidanceforpatients/

13 Research for Primary Prevention

There is a significant deficit in the knowledge about what interventions work best to reduce both pediatric exposure to unsafely stored firearms and, most importantly, pediatric firearm injuries and deaths. Multiple firearm research groups, including the Firearm Safety Among Children and Teens (FACTS) Consortium and the American Foundation for Firearm Injury Reduction in Medicine (AFFIRM) organization , as well as the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) , AAP, and other national groups have put forth research agendas and grants to identify best practices for screening and interventions with patients and families [46,47,49]. See Chap. 15.

Primary prevention screening and interventions should not be limited to the pediatrician’s office. Though clinicians should play an important role in the effort to reduce firearm injuries, as the FACTS consortium describes, it is essential to evaluate the role of school and community-based interventions in primary prevention as well. Engaging caregivers who own firearms is critical for the development of effective prevention strategies [47]. Likewise, research is needed across different regions of the country as attitudes about the role of firearms in the household likely differ. The consideration of scalability and practical implementation is paramount for widespread protection of children.

14 My Personal Approach to Firearm Screening and Advice

As a pediatric emergency physician, I do not ask every patient about firearms. I do ask, and I teach my trainees to ask, every patient who comes in with a mental health issue and every patient exposed to violence.

Ideally, I speak to both the patient and their parents separately. With my patients, I use the adolescent conversation approach of starting with safer topics using the HEADDSS acronym: Home, Education, Activities, Drugs, Depression, Sex, Suicide [50]. When I get to the topic of depression and suicide, I ask them directly “Is there a gun in the home?” I explain my reason for asking, “having a gun in the home of a person with depression puts them at higher risk of killing themselves, and I want to help keep you safe.” If there is a gun in the home, I ask the patient who owns the gun and how it is stored. I also ask them if they have access to a gun, since data about firearm suicides suggests that of adolescents who commit firearm suicide, 25% use a gun obtained outside of the home [15].

When I speak with the parents as part of the lethal means restrictions conversation, I first ask about how they store medications in their home to provide an overall context for safety planning. I then provide advice about using a locked tackle box to store the medications to provide protection for their child. And then I ask them the same direct questions about firearms that I have asked their children, “Is there a gun in the home?”. Regardless of how they answer, I provide the same advice. “The best place to store a gun for the safety of your child is outside of the home, in a safety deposit box or other locked space. If a gun must be stored in the home, for the safety of your child, it is important that the gun is stored locked, unloaded, and separate from the locked ammunition.” I provide advice about trigger locks and safety boxes and how to purchase them. I tell them that Massachusetts has laws mandating safe storage of all firearms to prevent access to firearms by children and youth. And I talk about the options of temporarily transfering the firearms to other people including family, friends, gun stores, shooting ranges or law enforcement. Please see Chap. 9 for further details.

One shift, I screened a 12-year-old girl who was acutely suicidal. When I asked about guns in the home, she told me that her brother, a police officer, regularly left his gun on the kitchen table when he came home from work. When I asked the parents if there were any guns in the house, the mom initially said no. I waited silently for 2 seconds. Then her eyes opened wide and her pupils dilated. “Wait! My son is a cop and he doesn’t always lock his gun up right when he comes home! I’ll talk to him today!”

Take Home Points

-

It is difficult to predict which families own guns, and it is difficult to predict which families will store guns safely or unsafely in their homes.

-

How firearms are stored in the home makes a difference for risk of injury and death.

-

Though clinicians broadly believe in and support screening and providing firearm storage advice, the majority do not regularly provide counseling to their patients.

-

The majority of families support health care clinicians discussing firearm safety.

-

There are multiple effective approaches to safe firearm storage.

-

Health care clinicians can legally talk to their patients about firearms and there are interventions and advice that can be provided effectively to parents and patients.

References

Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS™) [Internet]. Center for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. [cited 2020 Mar 21]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/fatal.html.

Okoro CA, Nelson DE, Mercy JA, Balluz LS, Crosby AE, Mokdad AH. Prevalence of household firearms and firearm-storage practices in the 50 states and the District of Columbia: findings from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 2002. Pediatrics. 2005;116(3):e370–6.

Terry L. Schell, Samuel Peterson, Brian G. Vegetabile, Adam Scherling, Rosanna Smart, and Andrew R. Morral. State-Level Estimates of Household Firearm Ownership [Internet]. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2020. https://www.rand.org/pubs/tools/TL354.html.

Smith TW, Son J. General Social Survey: trends in gun ownership in the United States, 1972–2014 [Internet]. NORD at the University of Chicago. Chicago; 2015. Available from: https://www.norc.org/PDFs/GSS%20Reports/GSS_Trends%20in%20Gun%20Ownership_US_1972-2014.pdf.

Parker BYK, Horowitz J, Igielnik R, Oliphant B, Brown A. America’s complex relationship with guns [Internet]. Pew Research Center. 2017. Available from: https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2017/06/22/the-demographics-of-gun-ownership/.

Mannix R, Lee LK, Fleegler EW. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and Firearms in the United States: Will an Epidemic of Suicide Follow? Ann Intern Med. 2020;4:173(3):228–9.

Nass, D. How Many Guns Did Amercians Buy Last Month? We’re Tracking the Sales Boom. The Trace. [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://www.thetrace.org/2020/08/gun-sales-estimates/.

Azrael D, Cohen J, Salhi C, Miller M. Firearm storage in gun-owning households with children: results of a 2015 National Survey. J Urban Health. 2018;95(3):295–304.

Healthychildren.org, American Academy Pediatrics; Gun safety and children [Internet]. Chicago; 2019. Available from: https://www.aap.org/en-us/ImagesGen/Gun Safety 7 x 12 half English_FINAL.jpg.

Grassel KM, Wintemute GJ, Wright MA, Romero MP. Association between handgun purchase and mortality from firearm injury. Inj Prev. 2003;9(1):48–52.

Siegel M, Rothman EF. Firearm ownership and suicide rates among US men and women, 1981–2013. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(7):1316–22.

Brent DA, Perper JA, Allman CJ, Moritz GM, Wartella ME, Zelenak JP. The presence and accessibility of firearms in the homes of adolescent suicides: a case-control study. JAMA. 1991;266(21):2989–95.

Dahlberg LL, Ikeda RM, Kresnow M. Guns in the home and risk of a violent death in the home: findings from a national study. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(10):929–36.

Miller M, Azrael D, Barber C. Suicide mortality in the United States: the importance of attending to method in understanding population-level disparities in the burden of suicide. Annu Rev Public Health. 2012;33(1):393–408.

Azad HA, Monuteaux MC, Hoffmann J, Lee LK, Mannix R, Rees CA, et al. Firearm violence in children and teenagers: the source of the firearm. Under Review 2020.

Grossman DC, Mueller BA, Riedy C, Dowd MD, Villaveces A, Prodzinski J, et al. Gun storage practices and risk of youth suicide and unintentional firearm injuries. JAMA. 2005;293(6):707–14.

Monuteaux MC, Azrael D, Miller M. Association of increased safe household firearm storage with firearm suicide and unintentional death among US youths. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(7):657–62.

Dowd MD, Sege R. Council on injury, violence and Poison Prevention. Firearm-related injuries affecting the pediatric population. Pediatrics. 2012;130(5):e1416–23.

Leshner AI, Altevogt BM, Lee AF, McCoy MA, Kelley PW. Priorities for research to reduce the threat of firearm-related violence. Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013. p. 1–109.

Hagan JF, Shaw JS, Duncan PM. Bright futures: Guidelines for health supervision of infants, children and adolescents [pocket edition]. 4th ed. Elk Grove Village: American Academy of Pediatrics. 2017.

Webster DW, Wilson ME, Duggan AK, Pakula LC. Firearm injury prevention counseling: a study of pediatricians' beliefs and practices. Pediatrics. 1992;89(5 Pt 1):902–7.

Grossman DC, Mang K, Rivara FP. Firearm injury prevention counseling by pediatricians and family physicians: practices and beliefs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149(9):973–7.

Hoopsa K, Crifasi C. Pediatric resident firearm-related anticipatory guidance: why are we still not talking about guns? Prev Med. 2019;124:29–32.

Butkus R, Weissman A. Internists’ attitudes toward prevention of firearm injury. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:821–7.

Grossman DC, Mang K, Rivara FP. Firearm injury prevention counseling by pediatricians and family physicians. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1996;149:973–7.

Becher EC, Cassel CK, Nelson EA. Physician firearm ownership as a predictor of firearm injury prevention practice. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(10):1626–8.

Guns [Internet]. Gallup. 2020 [cited 2020 Mar 30]. Available from: https://news.gallup.com/poll/1645/guns.aspx.

Farah MM, Simon HK, Kellermann AL. Firearms in the home: parental perceptions. Pediatrics. 1999;104(5 Part 1):1059–63.

Jackman GA, Farah MM, Kellermann AL, Simon HK. Seeing is believing: what do boys do when they find a real gun? J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2001;22(6):1247–50.

National Rifle Association. Eddie Eagle gunsafe program [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Mar 27]. Available from: https://eddieeagle.nra.org/.

Garbutt JM, Bobenhouse N, Dodd S, Sterke R, Strunk RC. What are parents willing to discuss with their pediatrician about firearm safety? A parental survey. J Pediatr. 2016;179:166–71.

Agrawal N, Arevalo S, Castillo C, Lucas AT. Effectiveness of the asking saves kids gun violence prevention campaign in an urban pediatric clinic. Pediatrics. 2018;142:730.

Aitken ME, Minster SD, Mullins SH, Hirsch HM, Unni P, Monroe K, et al. Parents’ perspectives on safe storage of firearms. J Community Health. 2020;45:469–77.

Crifasi CK, Doucette ML, McGinty EE, Webster DW, Barry CL. Storage practices of US gun owners in 2016. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(4):532–7.

Betz ME, Azrael D, Barber C, Miller M. Public opinion regarding whether speaking with patients about firearms is appropriate: results of a national survey. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(8):543–50.

Wintemute GJ, Betz ME, Ranney ML. Yes, you can: physicians, patients, and firearms. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(3):205–13.

McCourt AD, Vernick JS, Betz ME, Brandspigel S, Runyan CW. Temporary transfer of firearms from the home to prevent suicide: legal obstacles and recommendations. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(1):96–101.

Gibbons MJ, Fan MD, Rowhani-Rahbar A, Rivara FP. Legal Liability for Returning Firearms to Suicidal Persons Who Voluntarily Surrender Them in 50 US States. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(5):685–8.

Fleegler EW, Madeira JL. First, prevent harm: eliminate firearm transfer liability as a lethal means reduction strategy. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(5):619–20.

Roszko PJD, Ameli J, Carter PM, Cunningham RM, Ranney ML. Clinician attitudes, screening practices, and interventions to reduce firearm-related injury. Epidemiol Rev. 2016;38(1):87–110.

Barkin SL, Finch SA, Ip EH, Scheindlin B, Craig JA, Steffes J, et al. Is office-based counseling about media use, timeouts, and firearm storage effective? Results from a cluster-randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2008;122(1):e15–25.

Zatzick D, Russo J, Lord SP, Varley C, Wang J, Berliner L, et al. Collaborative care intervention targeting violence risk behaviors, substance use, and posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms in injured adolescents a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(6):532–9.

Albright TL, Burge SK. Improving firearm storage habits: impact of brief office counseling by family physicians. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16(1):40–6.

Benjamin Wolk C, Van Pelt AE, Jager-Hyman S, Ahmedani BK, Zeber JE, Fein JA, et al. Stakeholder perspectives on implementing a firearm safety intervention in pediatric primary care as a universal suicide prevention strategy: a qualitative study. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(7):e185309. 1–12.

Talking to Patients About Gun Safety [Internet]. Boston; 2017. Available from: http://www.massmed.org/firearmguidanceforproviders/.

Gun safety and Your Health [Internet]. Boston; 2017. Available from: http://www.massmed.org/firearmguidanceforpatients/.

Cunningham RM, Carter PM, Ranney ML, Walton M, Zeoli AM, Alpern ER, et al. Prevention of firearm injuries among children and adolescents: consensus-driven research agenda from the firearm safety among children and teens (FACTS) consortium. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(8):780–9.

AFFIRM [Internet]. American Foundation for Firearm Injury Reduction in Medicine. 2020 [cited 2020 Mar 21]. Available from: https://affirmresearch.org/grants/.

Ranney ML, Fletcher J, Alter H, Barsotti C, Bebarta VS, Betz ME, et al. A Consensus-Driven Agenda for Emergency Medicine Firearm Injury Prevention Research. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;69(2):227–40.

Goldenring JM, Cohen E. Getting into adolescent heads. Contemp Pediatr [Internet]. 1988;5(7):75–90. Available from: http://contemporarypediatrics.modernmedicine.com/contemporary-pediatrics/news/getting-adolescent-heads.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Fleegler, E.W. (2021). Talking with Families: Interventions for Health Care Clinicians. In: Lee, L.K., Fleegler, E.W. (eds) Pediatric Firearm Injuries and Fatalities . Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-62245-9_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-62245-9_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-62244-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-62245-9

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)