Abstract

Pathological Gambling (PG) has been linked to both specific personality traits and personality disorders (PDs). However, previous studies have used a wide variety of research designs that preclude clear conclusions about the personality features that distinguish adults with PG from other groups. The current investigation seeks to advance this research by using a sample including adults who do not gamble, who gamble socially, and who exhibit PG, using self-report, informant-report, and interview-rated measures of personality traits and disorders. A total of 245 adults completed measures of gambling behaviour and problems, as well as normative and pathological personality over two assessment visits. A multivariate ANCOVA was conducted to investigate differences between groups. Analyses supported numerous group differences including differences between all groups on the Neuroticism facet of Impulsivity, and between non-gambling/socially gambling and PG groups on the Conscientiousness facet of Self-Discipline. Adults with PG exhibited more symptoms of Borderline, Paranoid, Schizotypal, Avoidant, and Dependent PDs than adults who gamble socially or not at all. The current investigation provides a comprehensive survey of personality across a wide range of gambling involvement, using a multi-method approach. Our findings help to clarify the most pertinent personality risk factors for PG.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gambling disorder is the only non-substance-related addictive disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5; American Psychological Association). Pathological Gambling (PG) was previously used to capture these difficulties within the impulsive control disorder chapter of the DSM-IV. Notably, the more inclusive term problem gambling is used in many applied settings and captures a broader definition of maladaptive gambling behaviours ranging from mild to severe. Despite differences in measurement, definitions, and terminology, there is considerable overlap between the behaviours and symptoms that make up problem gambling, pathological gambling, and gambling disorder. For the purpose of this paper, we will use the abbreviation PG to refer to pathological gambling to reflect our focus on clinically significant gambling associated with substantial distress and impairment. Indeed, PG has been linked to a range of negative consequences, from relationship conflict, occupational issues, and financial strain to medical and mental health impacts, including suicidality (Cook et al. 2015; Black et al. 2015a, b; Kim et al. 2016; Rawat et al. 2017; Ronzitti et al. 2018). It has long been recognized that personality features may impact the onset, development, and clinical course of PG (Raylu and Oei 2002; Ramos-Grille et al. 2015; Black et al. 2015a, b; Bischof et al. 2015; Yan et al. 2016). Personality also predicts response to different treatment for PG, and may therefore have potential to inform clinical services (Ramos-Grille et al. 2014). Importantly, the personality features linked to problem gambling vary substantially across investigations, limiting conclusions about how to maximize their clinical utility.

PG and Personality Disorders

Adults with PG often meet criteria for one or more personality disorders; however, there is considerable variability in personality disorder (PD) prevalence estimates in PG samples. In a narrative review of 15 peer reviewed studies, Bagby and colleagues found that estimates of adults with PG with at least one DSM-IV Axis II disorder ranged widely from 25 to 93% (Bagby et al. 2008). Bagby and colleagues found a similarly large range in prevalence rates when PDs were assessed by self-report versus interview measures in both pathological and non-pathological gambling samples. The prevalence of at least one PD in PGs ranged from 87 to 93% when assessed by self-report and from 25 to 61% when assessed by interview. Additionally, there was considerable variance in the most commonly comorbid PDs, although Cluster C PDs were most consistently associated with PG. In a more recent study, Dowling et al. (2015) found that an average of 47.9% of adults with problem gambling included in their meta-analysis exhibit at least one comorbid PD, with Cluster B disorders appearing most frequently at 17.6% (ranging from 6.5 to 42% between studies). This was followed by Cluster C (mean of 12.6%; range of 3.7–27%), and Cluster A (mean of 6.1%; range of 2.2–24%). Subsequent investigations have extended these results. For example, Brown et al. (2016) found that DSM-IV Cluster B PDs were uniquely associated with PG severity. Similarly, Bischof et al. (2015) found the presence of comorbid PG and Cluster B personality disorders, especially borderline and antisocial PD, to indicate a significantly elevated risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. By contrast, in one of the largest interview based investigations of gambling and psychopathology, Ronzitti et al. (2018) found pathological and at risk gamblers to exhibit significantly higher comorbidity with all PDs except dependent PD than low risk or non-gamblers. In addition, the authors found Cluster A and C disorders to display greater prevalence than Cluster B disorders in PGs with a history of suicide attempts and ideation. Research has been consistent, however, regarding demonstration of similar poorer treatment outcomes, substance use comorbidity, and higher mortality for individuals with PG and a concurrent PD diagnosis (Meier and Barrowclough 2009; Trull et al. 2010; Black et al. 2015a, b).

Notably, the literature on PG/PD comorbidity remains challenging to synthesize due to design differences and limitations across studies. Many studies do not include or assess all PDs, which limits the degree to which a consensus can be reached about which disorders and Axis II Clusters are most highly comorbid with PG. PG/PD comorbidity studies also commonly exhibit other differences in study design such as the type and size of sample (adolescent vs. adult, university students vs. general population, treatment seeking vs. non-treatment seeking), choice of assessment instrument (particularly self-report or clinical interview), and differential treatment outcomes for different PD comorbidities. Furthermore, few studies adequately or consistently statistically control for the co-morbidity among PD diagnoses. As such, there remains a need for additional research that takes these considerations into account.

PG and Personality Traits

Varied estimates of PG/PD co-morbidity may simply reflect the flawed nature of the PD system of diagnosis (see Widiger and Trull 2007), in addition to specific study design features of PG/PD research. Dimensional personality models have far greater empirical support; among these, the Five Factor Model (FFM) is among the most widely used, including five higher-order trait domains, all of which are comprised of lower-order traits of greater specificity (e.g., Costa and McCrae 1992). FFM measures such as the Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO PI-R; Costa and McCrae 1992) have been used extensively in personality research in clinical populations. A meta-analysis conducted by MacLaren et al. (2012) found PGs to exhibit significantly higher negative affect (analogous to higher FFM neuroticism), higher unconscientious disinhibition (lower conscientiousness) and higher disagreeable disinhibition (lower agreeableness) than healthy controls. In subsequent studies, MacLaren et al. (2015) found that gambling severity scores were positively correlated with the neuroticism aspects of withdrawal and volatility, and negatively correlated with the extraversion aspect of enthusiasm, the agreeableness aspect of compliance, and the conscientiousness aspect of industriousness. In a large sample (N > 10,000) in Norway, Brunborg et al. found that PG samples scored higher on neuroticism and lower on the traits of conscientiousness and agreeableness than non-problem gamblers (Brunborg et al. 2016).

Despite the quantity of research that has been conducted to investigate personality traits associated with PG, there remain significant gaps in the literature. First, there exists mixed evidence for the importance of certain FFM traits as potential risk factors for PG. While the recent literature has established high neuroticism and low conscientiousness in PG (Bagby et al. 2007; Maclaren et al. 2012; 2015; Brunborg et al. 2016), there exists less agreement between studies on other FFM traits. For example, while some studies have found low FFM openness to be associated with PG (Myrseth et al. 2009; Cerasa et al. 2018) others have not (Maclaren et al. 2015; Brunborg et al. 2016). The same is true of some studies finding PG to be linked to low trait agreeableness (Brunborg et al. 2016; McGrath et al. 2018). Inconsistent associations between personality trait dimensions and PG may be the consequence of varied sample type (clinical versus undergraduate samples) and measure used. Furthermore, many investigations to date are limited by high reliance on self-report measures of personality and a lack of comparison groups across the spectrum of gambling involvement. Multi-method appraisal of personality traits improves the reliability and of validity of assessment substantively. Interview-based assessment has been found to enable the determination of the persistence, pervasiveness and adaptiveness of each trait (Trull et al. 2001). Informant-rated assessment provides an external perspective of each trait and permits the investigation of new research questions (Vazire 2006). The assessment of non-gamblers, social gamblers, and pathological gamblers ensures that the full range of gambling and personality phenomenology is sampled, and that problem gambling is compared to both non-problem gambling and non-gambling. A comprehensive and multimodal investigation is therefore necessary to understand inconsistencies in PG research, using rigorous personality research design and the current most widely-used overarching models of personality.

The Current Investigation

Our primary goals in the current research were to address concerns in the personality and problem gambling literature described above, including (1) measurement differences between self-report, informant-report, and interview-rated personality measures; (2) comparison sample differences in adults, including non-gambling and social gambling; and (3) personality pathology model (PD vs. personality traits). To achieve these goals, we employed a multi-method investigation in three groups of participants: (1) non-gambling, defined as those who have never gambled, (2) social gambling, defined as those who gamble but do not exhibit PG, and (3) pathological gambling, defined as those who meet criteria for PG. In secondary analyses, we also compared those not currently seeking treatment for PG and those currently seeking treatment for PG. This comprehensive, multi-method investigation of gambling and personality has several strengths. First, comparing non-gambling, social gambling, and PG samples simultaneously addresses the issues of study sample differences and comparison sample differences. Second, using self-report, observer-rated, and interview-based measures of psychopathology in a single cohort allows for a precise appraisal of measurement effects. Third, employing both categorical and dimensional measures of personality allow for estimation of the comparative utility of these measures in predicting PG.

We posed the following research hypotheses based on previous literature: (1) PG participants will demonstrate elevated Cluster B PDs compared to non-gambling and social gambling groups. PDs will not differ between non-gamblers and social gamblers. (2) The PG group will demonstrate elevated impulsivity and decreased self-discipline and deliberation compared to the non-gambling and social gambling groups. (3) The PG group will demonstrate elevated neuroticism compared to the other groups. (4) The social gambling group will demonstrate elevated openness-to-experience compared to the non-gambling group.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 245 adults (130 males, 115 females), with an age range of 18–64 years (M = 41.86, SD = 12.86). Study groups consisted of 60 non-gamblers (21 males, 39 females); 111 social gamblers (62 males, 49 females); 35 non-treatment-seeking pathological gamblers (22 males, 13 females); and 39 treatment-seeking pathological gamblers (24 males, 15 females). DSM-IV Axis I diagnoses were present in 48% (n = 117) of the sample, and included the following: mood disorders (n = 34), psychotic disorders (n = 9), substance use disorders (n = 14), anxiety disorders (n = 42), eating disorders (n = 2), and adjustment disorder (n = 1; n = 45 exhibited more than one co-occurring diagnosis).

We collected informant ratings for 88% of our sample (N = 216; 111 males, 105 females). Informant age ranged from 18 to 73 years (M = 41.35, SD = 14.03). Informants endorsed a duration of acquaintance with our participants ranging from 1 to 66 years (M = 13.93, SD = 12.93).

Procedure

Participants were solicited from the community sample using newspaper advertisements for a “Personality and Gambling Research Study.” Treatment-seeking participants were also recruited from the hospital research registry. Of the 711 individuals who contacted the laboratory in response to advertisements or gave consent to be contacted for future research, 406 expressed interest in participating and consented to a brief telephone screen to assess their suitability for participation. Of the 355 telephone screens conducted, 305 individuals were eligible for and interested in participation. Of the 255 assessments initiated, 1 was terminated due to inconsistent symptom endorsement and 9 were terminated due to past history of pathological gambling but no current symptomatology.

All participants were required to be between 18 and 65 years old, have completed a minimum of 8 years of education, be able to provide written informed consent, and be able to complete the study protocol in English. To be eligible for either PG group, participants were required to meet DSM-IV criteria for PG in the last 12 months. For the social gambling group, participants were required to have gambled during his/her lifetime but not meet DSM-IV criteria for either current or lifetime PG. For the non-gambling group, participants were required to not have gambled during his/her lifetime, and/or to have a score of 0 on the South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS). Eligible participants attended two five-hour sessions of interviewing and psychometric testing; an informant (family member or friend who knew the participant for > 1 year at time of study) attended the second session for approximately three hours of interviewing and psychometric testing. All participants provided both oral and written consent and received an honorarium to compensate them for their time and participation upon completion.

Measures

Axis I pathology: Axis I disorders were assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, Axis I Disorders, Patient Form (SCID-I/P; First et al. 1995). PG was assessed by an interview-based assessment of DSM-IV PG symptoms as well as the Canadian Problem Gambling Questionnaire (CPGI; Ferris and Wynne 2001) and South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS; Gambino and Lesieur 2006), which have demonstrated reliability and validity (Beaudoin and Cox 1999; Petry et al. 2005).

Personality disorders: PDs were assessed with the self-report Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders, Personality Questionnaire (SCID-II/PQ; First et al. 1997), informant-rated Multi-source Assessment of Personality Pathology (MAPP; Oltmanns & Turkheimer, 2006), and interview-based Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (DIPD-IV; Zanarini et al. 1996). The SCID-II/PQ is a widely used self-report questionnaire with good reliability and validity (Ekselius et al. 1994; Lobbestael et al. 2011). The MAPP is an informant measure that assesses the features of the 10 DSM-IV PDs (Oltmanns and Turkheimer 2006). The DIPD-IV is considered the “gold standard” interview for assessing PDs and was used in the NIMH-funded Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorder Study (CLPS), a major multi-site study of the longitudinal stability of personality disorders (Gunderson et al. 2000). All scales varied in item format (SCID-II/PQ items are scored 0 or 1, DIPD items are scored 0, 1, or 2, and MAPP items are scored 1 to 4), and PD subscales varied in item number. Scales were scored according to standardized instructions, with raw scores used in analyses and reported in Tables below. PD symptom counts are included in Figures to facilitate comparison across scales.

Personality traits: The traits of the Five-Factor Model of personality were assessed with the self-report (Form S) and observer-rated (Form R) Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO PI-R; Costa and McCrae 1992) and the Structured Interview for the Five-Factor Model (SIFFM; Trull and Widiger 1997), a semi-structured interview which has demonstrated acceptable levels of reliability and validity (Trull et al. 1998). The NEO PI-R items are scored from 0 to 4, with facet scales ranging from 0 to 32 and domain scales ranging from 0 to 192. In contrast, the SIFFM items are scores from 0 to 2, with facet scales ranging from 0 to 8 and domain scales ranging from 0 to 48. Raw scores were used in all analyses; however, T scores are presented in Figures below to facilitate comparisons across scales.

Statistical Analyses

To evaluate personality trait dimensions in each group, a series of multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVAs) were conducted to compare each gambling sample with the non-gambling sample on PD symptom counts and personality trait dimensions. Post hoc-t tests were conducted when supported by the results of the MANOVA using least squares difference (LSD). Cohen’s d was used to provide an estimate of effect size.

Results

Personality Traits

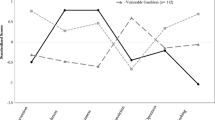

Results from the NEO PI-R Form S/R and SIFFM are displayed in Table 1, with domain level results depicted graphically in Fig. 1. MANOVA results are found in Table 2 and indicate significant group differences on the domain and facet level for each of the five factors of the FFM, with the exception of the extraversion facets of the NEO PI-R Form S. Post-hoc results indicate multiple specific intergroup differences on each facet, summarized below by domain:

Neuroticism: At the domain level, on both the NEO PI-R Form S and the SIFFM, all three gambling involvement groups differed significantly in their level of Neuroticism, with non-gamblers showing the lowest neuroticism scores, social gamblers the second highest, and problem gamblers the highest scores. Results from the NEO PI-R Form R replicated the differences between the NG-PG and SG-PG groups, but found no differences between NG-SG on trait Neuroticism. At the facet level, the same pattern of group differences was found for the facets of Anxiety, Depression, and Self-Consciousness. A pattern of differences between NGs-PGs and SGs-PGs was found across all three measures in Angry Hostility and Vulnerability. Impulsivity was the only facet that displayed significant differences across all groups and all measures.

Extraversion: At the domain level, results from the NEO PI-R Form S and SIFFM found differences between groups, in both cases between NG-PG and SG-PG groups. At the facet level, there was limited consistency between measures: results from the NEO PI-R Form S indicated differences between the NG-PG and SG-PG groups on Warmth, Gregariousness, Assertiveness, and between all groups on Positive Emotionality. In contrast, the SIFFM found significant differences between NG-PG and SG-PG groups on Gregariousness and Activity, and there were no significant differences found using NEO PI-R Form R. No group differences were consistent across the three measures.

Openness: At the domain level, differences were found across all groups when using the NEO PI-R Form S, whereas the NEO PI-R Form R found differences between NG-PG and SG-PG groups and the SIFFM found none. At the facet level, results from the NEO PI-R Form S found differences across all groups in Actions and Values, as well as differences between NG-PG and SG-PG groups in Ideas, and between NG-PG groups in Aesthetics and Feelings. On the NEO PI-R Form R, results showed differences between NG-PG and NG-SG on Actions and Values, a difference between NG-PG on Fantasy, and a difference between NG-SG on Aesthetics. On the SIFFM, results showed NG-PG differences on Fantasy and Feelings and a SG-PG difference on Values. The only difference between groups that was consistent across all three measures was SG-PG on Values.

Agreeableness: At the domain level, results from the NEO Form S indicated differences between NG-PG and SG-PG groups, whereas the NEO Form R found only a difference between NG-PG groups and the SIFFM found none. At the facet level, results from the NEO Form S indicated differences across all groups in Trust, differences between NG-PG and SG-PG groups in Altruism and Compliance, and differences between NG-PG groups in Straightforwardness and SG-PG groups in Tendermindedness. On the NEO Form R, NG-PG differences were found in the facets of Trust, Straightforwardness, and Compliance, and a NG-SG difference was found in Modesty. On the SIFFM, differences between NG-PG and SG-PG were found in Modesty and differences between NG-SG and NG-PG were found in Tendermindedness. No group differences were consistent across all three measures.

Conscientiousness: At the domain level, differences between all groups were found with the NEO Form S, and between NG-PG groups with the NEO Form R. At the facet level, differences between NG-PG and SG-PG groups were found using the NEO Form S for Competence, Dutifulness, and Self-Discipline. NG-PG differences were found for Order and Achievement Striving, and differences across all groups were found for Deliberation. Using the NEO Form R, NG-PG differences were found for Competence and Dutifulness, NG-PG and SG-PG differences were found for Self-Discipline, and differences across all groups were found for Deliberation. Using the SIFFM, NG-PG differences were found in Order and Deliberation, and NG-PG and SG-PG differences were found in Self-Discipline. The NG-PG difference on Deliberation and the NG-PG, SG-PG differences on Self-Discipline were significant across all three measures.

Personality Disorders

Results indicating symptom counts for PD from the DIPD, MAPP, and SCID-II PQ are shown in Table 3, and depicted graphically in Fig. 2. On the DIPD, significant differences between NG-PG and SG-PG groups were found for Paranoid, Antisocial, Borderline, Narcissistic, Avoidant, Dependent, and Obsessive–Compulsive PD. NG-SG and NG-PG differences were found for Schizoid PD, and a difference between all groups was found for Schizotypal PD. On the MAPP, NG-PG and SG-PG differences were found for Paranoid, Schizotypal, Antisocial, Borderline, Histrionic, Narcissistic, Avoidant, and Dependent PD, and a SG-PG difference was found for Obsessive–Compulsive PD. On the SCID-II PQ, differences were found for Paranoid, Schizoid, Schizotypal, Borderline, Avoidant, Dependent, and Obsessive–Compulsive PD between all groups, and significant NG-SG and NG-PG differences were found for Antisocial and Narcissistic PD.

Non-Treatment-Seeking/Treatment-Seeking PG Comparisons

With respect to personality traits, differences were found on the Conscientiousness facet of Deliberation on the NEO Form S (t = 2.48, p = 0.01, d = 0.66), the Openness facet of Aesthetics of the NEO Form R (t = 2.07, p = 0.04, d = 0.54), and the Openness facet of Feelings of the SIFFM (t = 2.13, p = 0.04, d = 0.34). There were no differences across groups in PD symptoms.

Discussion

Results demonstrated a wide array of personality differences across participants with different gambling involvement and harms. Results varied across self-, other-, and interview-report as well as model of personality; however, several dimensional traits were consistently associated with gambling status.

Group Differences in Personality Features

Consistent with hypotheses, we found consistent differences across most measures of Neuroticism, with the exception of no difference between social and non-gambling groups using informant report. These group differences presented sequentially, with the NG group scoring lowest on neuroticism measures, followed by the SG group, and finally the PG group scoring highest. These results are largely consistent with existing evidence for links between problem gambling and neuroticism (Bagby et al. 2007; Maclaren et. al. 2012; Maclaren et al. 2015; Brunborg et al. 2016); however, our findings suggest not only that control groups score lower on Neuroticism than problem gamblers, but also that non-gamblers exhibited lower scores than social gamblers. The group differences we found across all measures and groups on Impulsivity replicates a number of previous studies that have linked problem gambling to impulsivity, further supporting the role of trait impulsivity as a specific and robust risk factor for the development of problem gambling (Blaszczynski et al. 1997; Petry 2001a, b; Alessi and Petry 2003; Verdejo-Garcia et al. 2008; Myrseth et al. 2009; Barrault and Varescon 2013; Marazziti et al. 2014; Black et al. 2015a, b; Hodgins and Holub 2015). NG-PG differences in impulsivity exhibited particularly robust effect sizes, with an average effect size across measures of d = 1.23.

Neuroticism was the only trait in which consistent differences were found across all three groups at the domain level; however, other consistencies did emerge. The PG group scored significantly lower on Conscientiousness than the NG group across all measures, again replicating previous research implicating low conscientiousness in PG (Bagby et al. 2007; Maclaren et al. 2015; Brunborg et al. 2016; Mann et al. 2017; McGrath et al. 2018). In addition, consistent NG-PG differences on Deliberation as well as consistent NG-PG and SG-PG differences on Self-Discipline are largely in agreement with our hypotheses and highlight the specific facets of conscientiousness relevant to PG.

Notably, we did not find evidence of consistent differences between NGs and SGs/PGs on the Extraversion facet of Excitement Seeking. Bagby et al. (2007) found high scores on Excitement Seeking for both non-PGs and PGs in their study, suggesting that heightened Excitement-Seeking is a personality trait associated with gambling involvement rather than gambling problems specifically. We did find a significant difference between NGs and PGs on Excitement Seeking only on the informant-report NEO PI-R Form-R, calling the robustness of this result into question. One key difference of note between our sample and that of Bagby et al. (2007), however, was that while we used a trio of groups representing non-gamblers, social-gamblers, and individuals with PG, Bagby et al. collapsed both non-gamblers and social gamblers within the comparison group. Beyond these differences, social gamblers and non-gamblers did not consistently differ on any five-factor personality variables (although other differences did emerge, see below).

Similarly, we found a large number of group differences across measures in the number of PD symptoms endorsed. Consistent with hypotheses, the PG group exhibited more symptoms of Borderline PD than other groups. Notably, however, the PG group also exhibited more symptoms than both NGs and SGs on Paranoid, Schizotypal, Avoidant and Dependent PDs, and more symptoms than either NGs or SGs on Antisocial, Narcissistic, and Obsessive–Compulsive PD across all measures. Previous research has suggested a shared etiological basis for Borderline PD and gambling disorder (Brown et al. 2015). This nonspecific result may reflect the high comorbidity rates among Axis II disorders (Zanarini et al. 1996; Loas et al. 2013), and underscore the value in a dimensional approach such as the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP; Kotov et al 2017).

Differences Between Instrument Modality

With the exception of the Neuroticism and Conscientiousness, personality trait differences varied according to which report measure was used. Overall, we found that self-report yielded the greatest overall number of statistically significant group differences, followed by informant report and interview. There was a lack of agreement between informant and interview measures regarding which traits differentiated between groups. Informant report located a NG-SG difference only for Openness, whereas interview ratings found a NG-SG difference only for Neuroticism. Additionally, informant report located SG-PG differences in Neuroticism and Conscientiousness, whereas interview ratings found differences for Neuroticism and Extraversion.

Similar to our findings for dimensional personality traits, for personality disorder symptomatology, we found that self-report yielded the most significant group differences (25), followed by interview ratings (19) and informant-report (18). Informant report yielded the highest overall symptom counts for PDs in non-gamblers, in concordance with previous PD studies (Balsis et al. 2018). Previous research comparing mean differences between different types of report measures has found that while FFM self-report measures tend to have reasonably high convergent validity with informant-report and semi-structured interview measures at the trait and facet level, there is more divergence between mean scores between informant reports and interview measures (Samuel and Widiger 2010). This mirrors our own findings for FFM data.

Multiple studies have evaluated the accuracy of different report measures for studying personality variables and found that different measures are sensitive to different areas of personality. As such, while we have focused mainly on the results which showed cross-measure agreement, it is possible that different report measures are differentially sensitive to different traits, such that interview report measures are more sensitive to differences in extraversion and informant reports relatively more sensitive to differences in openness. Previous research has found some partial evidence for this, in that informant reports tend to be more accurate at identifying more evaluative and externalizing traits, such as Openness/Intelligence, whereas self-reports tend to be more accurate at identifying internalizing traits in which the individual has the most insight, such as neuroticism (Vazire 2010; Carlson et al. 2013). It is worth noting here that both the NEO-R and the SIFFM found scores on the Openness facet of Fantasy to be significantly higher for PGs than NGs, whereas the NEO-S did not, consistent with Vazire’s Self-Other Knowledge Asymmetry model (SOKA; Vazire 2010). The NEO-R also found evidence of increased Excitement Seeking, which can be conceptualized as an externalizing personality trait, in PGs over NGs (as suggested by Bagby et al. 2008). Additionally, the NEO-S found scores on the facet of Positive Emotionality (an internalizing trait) to decrease linearly from NGs-SGs-PGs.

Limitations and Future Directions

There were several limitations to the current study. First, given the considerable variability present in the results across our three report measures, it is difficult to reach a clear conclusion about which personality variables and disorders are most important to consider as risk factors. While we chose to focus mainly on results that were consistent across report measures as a proxy for “robustness”, this may be an inappropriate way to interpret the results of our study. As such, cross-method replication is needed in order to gain a better understanding of personality risk factors for the development of PG, particularly if certain methods are indeed selectively sensitive to different traits. Replication of some of our inconsistent results using the same report method in question could add credence to the idea that these variables are indeed worth consideration as risk/resilience factors in PG. Additionally, as this is a cross-sectional study, we are unable to make any conclusions about predictive relationships between either normative personality traits or personality disorders and PG. Future studies utilizing a longitudinal design and including a full range of gambling involvement groups can support the investigation of how these personality variables change over time and are prospectively linked to gambling in those exhibiting lower gambling involvement (i.e. non/social gambling) to PG. Although there were limited changes to diagnostic criteria between DSM-IV and DSM-5, it would also be of benefit to ensure these associations replicate or extend to Gambling Disorder as well.

Conclusion

The present investigation represents a broad assessment of personality risk and resilience factors associated with problem gambling. By using both normative and pathological personality models and three different modalities, in addition to two comparison groups, we sought to address some of the gaps in the literature and obtain precise information about the personality profile of PG. Analyses supported numerous group differences including differences between all groups on the Neuroticism facet of Impulsivity, and between non-gambling/socially gambling adults and PGs on the Conscientiousness facet of Self-Discipline. Adults with PG exhibited more symptoms of Borderline, Paranoid, Schizotypal, Avoidant, and Dependent PDs than adults who gamble socially or not at all. Our findings have the potential to inform etiological models of PG as well as broader models of personality-psychopathology.

References

Alessi, S. M., & Petry, N. M. (2003). Pathological gambling severity is associated with impulsivity in a delay discounting procedure. Behavioural Processes, 64(3), 345–354.

Bagby, R. M., Vachon, D. D., Bulmash, E., & Quilty, L. C. (2008). Personality disorders and pathological gambling: A review and re-examination of prevalence rates. Journal of Personality Disorders, 22(2), 191–207. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2008.22.2.191.

Bagby, R. M., Vachon, D. D., Bulmash, E. L., Toneatto, T., Quilty, L. C., & Costa, P. T. (2007). Pathological gambling and the five-factor model of personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(4), 873–880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.02.011.

Balsis, S., Loehle-Conger, E., Busch, A. J., Ungredda, T., & Oltmanns, T. F. (2018). Self and informant report across the borderline personality disorder spectrum. Personality Disorders, 9(5), 429–436. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000259.

Barrault, S., & Varescon, I. (2013). Impulsive sensation seeking and gambling practice among a sample of online poker players: Comparison between non pathological, problem and pathological gamblers. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(5), 502–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.04.022.

Beaudoin, C. M., & Cox, B. J. (1999). Characteristics of problem gambling in a Canadian context: A preliminary study using a DSM-IV-based questionnaire. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 44(5), 483–487.

Bischof, A., Meyer, C., Bischof, G., John, U., Wurst, F. M., Thon, N., et al. (2015). Suicidal events among pathological gamblers: The role of comorbidity of axis I and axis II disorders. Psychiatry Research, 225(3), 413–419.

Black, D. W., Coryell, W., Crowe, R., McCormick, B., Shaw, M., & Allen, J. (2015b). Suicide ideations, suicide attempts, and completed suicide in persons with pathological gambling and their First-Degree relatives. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 45(6), 700–709. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12162.

Black, D. W., Coryell, W. H., Crowe, R. R., Shaw, M., McCormick, B., & Allen, J. (2015a). Personality disorders, impulsiveness, and novelty seeking in persons with DSM-IV pathological gambling and their first-degree relatives. Journal of Gambling Studies, 31(4), 1201–1214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-014-9505-y.

Blaszczynski, A., Steel, Z., & McConaghy, N. (1997). Impulsivity in pathological gambling: the antisocial impulsivist. Addiction, 92(1), 75–87.

Brown, M., Allen, J. S., & Dowling, N. A. (2015). The application of an etiological model of personality disorders to problem gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 31(4), 1179–1199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-014-9504-z.

Brown, M., Oldenhof, E., Allen, J. S., & Dowling, N. A. (2016). An empirical study of personality disorders among treatment-seeking problem gamblers. Journal of Gambling Studies, 32(4), 1079–1100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-016-9600-3.

Brunborg, G. S., Hanss, D., Mentzoni, R. A., Molde, H., & Pallesen, S. (2016). Problem gambling and the five-factor model of personality: A large population-based study. Addiction, 111(8), 1428–1435. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13388.

Carlson, E. N., Vazire, S., & Oltmanns, T. F. (2013). Self-other knowledge asymmetries in personality pathology. Journal of Personality, 81(2), 155–170.

Cerasa, A., Lofaro, D., Cavedini, P., Martino, I., Bruni, A., Sarica, A., & Quattrone, A. (2018). Personality biomarkers of pathological gambling: A machine learning study. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 294, 7–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2017.10.023.

Cook, S., Turner, N. E., Ballon, B., Paglia-Boak, A., Murray, R., Adlaf, E. M., & Mann, R. E. (2015). Problem gambling among Ontario students: Associations with substance abuse, mental health problems, suicide attempts, and delinquent behaviours. Journal of Gambling Studies, 31(4), 1121–1134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-014-9483-0.

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). NEO-PI-R professional manual. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Dowling, N. A., Cowlishaw, S., Jackson, A. C., Merkouris, S. S., Francis, K. L., & Christensen, D. R. (2015). The prevalence of comorbid personality disorders in treatment-seeking problem gamblers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Personality Disorders, 29(6), 735–754. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi_2014_28_168.

Ekselius, L., Linstrom, E., von Knorring, L., Bodlund, O., & Kullgren, G. (1994). SCID II interviews and the SCID screening questionnaire as diagnostic tools for personality disorders in DSM-III-R. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 90(2), 120–123.

Ferris, J., & Wynne, H. (2001). The Canadian Problem Gambling Index: User Manual. Report to Canadian Inter-Provincial Task Force on Problem Gambling.

First, M. B., Gibbon, M., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B. W., & Benjamin, L. S. (1997). User’s guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders. Washington: American Psychiatric Press.

First, M. B., Spitzer, R. L., Gibbon, M., & Williams, J. B. W. (1995). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis_I disorders—patient edition (SCID-I/P, version 2.0). New York: New York Psychiatric Institute.

Gambino, B., & Lesieur, H. (2006). The south oaks gambling screen (SOGS): A rebuttal to critics. Journal of Gambling Issues. https://doi.org/10.4309/jgi.2006.17.10.

Gunderson, J. G., Shea, M. T., Skodol, A. E., McGlashan, T. H., Morey, L. C., Stout, R. L., et al. (2000). The collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study: Development, aims, design, and sample characteristics. Journal of Personality Disorders, 14(4), 300–315.

Hodgins, D. C., & Holub, A. (2015). Components of impulsivity in gambling disorder. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 13(6), 699–711. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-015-9572-z.

Kim, H. S., Salmon, M., Wohl, M. J., & Young, M. (2016). A dangerous cocktail: Alcohol consumption increases suicidal ideations among problem gamblers in the general population. Addictive Behaviors, 55, 50–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.12.017.

Kotov, R., Krueger, R. F., Watson, D., Achenbach, T. M., Althoff, R. R., Bagby, R. M., & Eaton, N. R. (2017). The hierarchical taxonomy of psychopathology (HiTOP): A dimensional alternative to traditional nosologies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(4), 454.

Loas, G., Pham-Scottez, A., Cailhol, L., Perez-Diaz, F., Corcos, M., & Speranza, M. (2013). Axis II comorbidity of borderline personality disorder in adolescents. Psychopathology, 46(3), 172–175.

Lobbestael, J., Leurgans, M., & Arntz, A. (2011). Inter-rater reliability of the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders (SCID I) and axis II disorders (SCID II). Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 18(1), 75–79. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.693.

Maclaren, V., Ellery, M., & Knoll, T. (2015). Personality, gambling motives and cognitive distortions in electronic gambling machine players. Personality and Individual Differences, 73, 24–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.09.019.

MacLaren, V. V., Fugelsang, J. A., Harrigan, K. A., & Dixon, M. J. (2012). Effects of impulsivity, reinforcement sensitivity, and cognitive style on pathological gambling symptoms among frequent slot machine players. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(3), 390–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.10.044.

Mann, K., Lemenager, T., Zois, E., Hoffmann, S., Nakovics, H., Beutel, M., & Fauth-Bühler, M. (2017). Comorbidity, family history and personality traits in pathological gamblers compared with healthy controls. European Psychiatry, 42, 120–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.12.002.

Marazziti, D., Picchetti, M., Baroni, S., Consoli, G., Ceresoli, D., Massimetti, G., & Catena Dell’Osso, M. (2014). Pathological gambling and impulsivity: An italian study. Rivista Di Psichiatria, 49(2), 95.

McGrath, D. S., Neilson, T., Lee, K., Rash, C. L., & Rad, M. (2018). Associations between the HEXACO model of personality and gambling involvement, motivations to gamble, and gambling severity in young adult gamblers. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(2), 392–400. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.29.

Meier, P., & Barrowclough, C. (2009). Mental health problems: Are they or are they not a risk factor for dropout from drug treatment? A systematic review of the evidence. Drugs: Education Prevention and Policy, 16(1), 7–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687630701741030.

Myrseth, H., Pallesen, S., Molde, H., Johnsen, B. H., & Lorvik, I. M. (2009). Personality factors as predictors of pathological gambling. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(8), 933–937. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.07.018.

Oltmanns, T. F., & Turkheimer, E. (2006). Perceptions of self and others regarding pathological personality traits. In R. F. Krueger & J. L. Tackett (Eds.), Personality and psychopathology (pp. 71–111). New York: Guilford Press.

Petry, N. M. (2001a). Delay discounting of money and alcohol in actively using alcoholics, currently abstinent alcoholics, and controls. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 154(3), 243–250.

Petry, N. M. (2001b). Pathological gamblers, with and without substance use disorders, discount delayed rewards at high rates. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110(3), 482–487.

Petry, N. M., Stinson, F. S., & Grant, B. F. (2005). Comorbidity of DSM-IV pathological gambling and other psychiatric disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 66, 564–574.

Ramos-Grille, I., Gomà-I-Freixanet, M., Aragay, N., Valero, S., & Vallès, V. (2015). Predicting treatment failure in pathological gambling: The role of personality traits. Addictive Behaviors, 43, 54–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.12.010.

Rawat, V., Greer, N., Langham, E., Rockloff, M., & Hanley, C. (2017). What is the harm? Applying a public health methodology to measure the impact of gambling problems and harm on quality of life. Journal of Gambling Issues. https://doi.org/10.4309/jgi.2017.36.2.

Raylu, N., & Oei, T. P. S. (2002). Pathological gambling: A comprehensive review. Clinical Psychology Review, 22(7), 1009–1061. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(02)00101-0.

Ronzitti, S., Kraus, S. W., Hoff, R. A., Clerici, M., & Potenza, M. N. (2018). Problem-gambling severity, suicidality and DSM-IV axis II personality disorders. Addictive Behaviors, 82, 142–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.03.003.

Samuel, D. B., & Widiger, T. W. (2010). Comparing personality disorder models: Cross-method assessment of the FFM and DSM-IV-TR. Journal of Personality Disorders, 24(6), 721–745. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2010.24.6.721.

Trull, T. J., Jahng, S., Tomko, R. L., Wood, P. K., & Sher, K. J. (2010). Revised NESARC personality disorder diagnoses: gender, prevalence, and comorbidity with substance dependence disorders. Journal of personality disorders, 24(4), 412–426.

Trull, T. J., & Widiger, T. A. (1997). Structured interview for the five-factor model of personality (SIFFM): Professional manual. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Trull, T. J., Widiger, T. A., & Burr, R. (2001). A structured interview for the assessment of the five-factor model of personality: Facet-level relations to the Axis II personality disorders. Journal of Personality, 69(2), 175–198.

Trull, T. J., Widiger, T. A., Useda, J. D., Holcomb, J., Doan, B., Axelrod, A. R., et al. (1998). A structured interview for the assessment of the five-factor model of personality. Psychological Assessment, 10(3), 229–240.

Vazire, S. (2006). Informant reports: A cheap, fast and easy method for personality assessment. Journal of Research in Personality, 40(5), 472–481.

Vazire, S. (2010). Who knows what about a person? The self-other knowledge asymmetry (SOKA) model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(2), 281–300. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017908.

Verdejo-García, A., Lawrence, A. J., & Clark, L. (2008). Impulsivity as a vulnerability marker for substance-use disorders: Review of findings from high-risk research, problem gamblers and genetic association studies. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 32(4), 777–810. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.11.003.

Widiger, T. A., & Trull, T. J. (2007). Plate tectonics in the classification of personality disorder: Shifting to a dimensional model. American Psychologist, 62(2), 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.2.71.

Yan, W., Zhang, R., Lan, Y., Li, Y., & Sui, N. (2016). Comparison of impulsivity in non-problem, at-risk and problem gamblers. Scientific Reports. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep39233.

Zanarini, M. C., Frankenburg, F. R., Sickel, A. E., & Yong, L. (1996). The diagnostic interview for DSM-IV personality disorders (DIPD-IV). Belmont: McLean Hospital.

Funding

This study was funded by a Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre (OPGRC) Level IV grant (#2662). OPGRC approved the research proposal, including objectives and methodology, but had no involvement in the design, conduct, analysis, or write-up.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. Quilty has received research funding from the Ontario Lottery and Gaming. All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee (CAMH Research Ethics Board, REB14-1623) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Quilty, L.C., Otis, E., Haefner, S.A. et al. A Multi-Method Investigation of Normative and Pathological Personality Across the Spectrum of Gambling Involvement. J Gambl Stud 38, 205–223 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-021-10011-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-021-10011-8