Abstract

Gambling disorder affects approximately 1.1–3.5% of the population, with the rates being higher in young adults. Despite this high prevalence, little is known regarding which pathological gamblers decide to seek treatment. This study sought to examine the differences in three groups of pathological gamblers: those who did not seek treatment (n = 94), those who sought therapy (n = 106) and those who sought medication therapy (n = 680). All subjects were assessed on a variety of measures including demographics, family history, gambling history, comorbid psychiatric disorders and an assortment of clinical variables such as the Quality of Life Inventory, Hamilton Depression and Anxiety Rating Scales, Yale Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale for Pathologic Gambling (PG-YBOCS), Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, Eysenck Impulsiveness Questionnaire and select cognitive tasks. Those seeking treatment were more likely to be Caucasian, have lost more money in the past year due to gambling, and were more likely to have legal and social problems as a result of their gambling. Those seeking therapy or medical treatment also scored significantly higher on the PG-YBOCS. This study suggests that pathologic gamblers seeking treatment were more likely to exhibit obsessive–compulsive tendencies likely leading to the increased legal and social problems that exist in this group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gambling disorder is characterized by persistent and recurrent problematic gambling behavior that leads to clinically significant impairment or distress. It is classified as a substance-related and addictive disorder, a tribute to its similarity with other behavioral and substance addictions (APA 2013; Petry et al. 2013). The prevalence of gambling disorder has been shown to range from 1.1 to 3.5% (Lorains et al. 2011; Williams et al. 2012). The rates have been shown to be even higher in young adults, ranging from 6 to 9% (Barnes et al. 2010).

A number of treatments for gambling disorder have been studied with varying results and have included serotonin reuptake inhibitors, opioid antagonists, mood stabilizers and antipsychotics, as well as therapy modalities such as cognitive-based therapy, motivational interviewing and gamblers anonymous (Grant and Kim 2006; Nautiyal et al. 2017). However, to date no medical treatment has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for gambling disorder.

Despite its often debilitating nature, and the promise of several treatments, less than 10% of problem gamblers seek treatment (Braun et al. 2014). Some have attributed this to the high rates of natural recovery that exist across not only gambling disorders, but also other substance use disorders (Slutske 2006; Hodgins and el-Guebaly 2000). Other studies have shown distinct barriers that exist to seeking treatment such as pride, shame and denial (Pulford et al. 2009). Conversely, some research suggests that when gambling problems become severe, reflected by the amount of gambling debt and intervention by legal and/or social networks, individuals seek treatment (Weinstock et al. 2011; Braun et al. 2014).

Given this background, there are several questions that remain unanswered. Are there differences in gamblers who seek treatment versus those who do not? When individuals do seek treatment, are there differences between those who seek medication or psychotherapy? To our knowledge, no study has examined the differences in therapy seeking versus medication seeking problem gamblers. Does the difference in modality change the desire of a problem gambler to seek treatment?

In our examination of these questions, and based on the extant research, we made the following hypotheses. (1) We hypothesized that among pathologic gamblers those seeking treatment (either therapy or medication) would have increased urges to gamble when compared to those who do not seek treatment. (2) While the three groups analyzed in this study (non-treatment seeking gamblers, therapy seeking gamblers and medication seeking gamblers) likely suffer from a similar drive to initiate gambling, we hypothesized that treatment-seeking gamblers would have increased urges to keep gambling causing increased financial losses. (3) As a result of this increased drive to continue gambling, we hypothesized that treatment-seeking gamblers would be more likely to have legal, social and/or familial problems secondary to gambling. (4) Finally, because these repercussions may be the driving factor behind why a pathologic gambler ends up seeking treatment, we hypothesized that those treatment-seeking gamblers with more serious gambling related problems would be more likely to seek pharmacological treatment instead of psychotherapy.

Materials and Methods

Participants

A group of non-treatment seeking gamblers, a group of therapy seeking gamblers and a group of medication seeking gamblers were recruited from the Minneapolis and Chicago metropolitan areas via media advertisements. For detailed information regarding these individual studies see the following citations: Harries et al. (2017), Kim et al. (2001, 2002), Grant et al. (2003, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010a, b, 2013, 2014) and Grant and Potenza (2006). Common exclusion criteria for both treatment groups included, but was not limited to, current suicidality, severe depression or other severe mental illness requiring intervention, impaired cognitive ability, substance or alcohol use disorder within the last 3 months, current diagnosis of bipolar or psychotic disorder or current participation in Gambler’s Anonymous.

Measurements

Grouping Methods

All participants were diagnosed with a gambling disorder based on the qualifications established in the Minnesota Impulsive Disorders Interview (MIDI) or the Structured Clinical Interview for Pathological Gambling (SCI-PG), depending on the respective study (Grant 2008; Grant et al. 2004). Subjects were grouped into one of three categories: non-treatment seekers, those seeking and receiving psychotherapy and those seeking and receiving medication treatment.

Demographic and Family History Variables

All subjects responded to a variety of basic demographic questions pertaining to age, gender, education, race and income. Subjects were also asked if first-degree family members had gambling problems.

Gambling History

Subjects responded to a semi-structured interview pertaining to their gambling behavior and its implications. Such questions included the age of first gambling, the age at which they began gambling regularly, and the financial losses due to gambling over the past year. In addition, subjects were asked why they gambled (e.g. to make money, to escape from problems, etc.). Subjects also reported whether or not they had legal, financial, work or social problems as a result of their gambling.

Comorbidities

Co-occurring Psychiatric Disorders

All participants were assessed for current and past co-occurring psychiatric disorders [e.g. major depressive disorder, general anxiety disorder and obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD)] using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) (Sheehan et al. 1998). Participants were also asked to report lifetime history of other medical diagnoses.

Clinical Variables

Quality of Life

The self-administered Quality of Life Inventory (QoLI) was used to examine satisfaction with various life domains (e.g. work, leisure activities) (Frisch 2013).

Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms

Depressive symptoms and anxiety symptoms were examined using the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) (Hamilton 1959, 1960).

Yale Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for Pathological Gambling (PG-YBOCS)

The PG YBOCS was used to assess gambling severity for the week prior to the evaluation. The PG-YBOCS is comprised of a total score and two subscale scores assessing urges/preoccupations with gambling and gambling behavior (Pallanti et al. 2005).

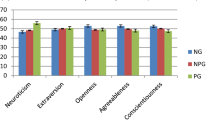

Impulsiveness

Participants completed self-report measures: the Eysenck Impulsiveness Questionnaire (EIQ) and the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11 (BIS). The EIQ consists of 54 questions and examines three sub-domains of impulsivity: impulsiveness (the subject’s likelihood to act without thinking), venturesomeness (the subject’s likelihood to engage in a new activity or action) and empathy (the subject’s likelihood to feel similarly or engage in similar actions with those around them) (Eysenck et al. 1985). The Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11 (BIS) consists of 30 questions and is divided into 3 sub-scales: attention impulsiveness, motor impulsiveness, and non-planning impulsiveness (Patton et al. 1995).

Neurocognitive Variables

The Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB) was used to analyze cognitive functioning. Testing occurred in a quiet room using a touch-screen computer. Two domains were tested: (1) Set-shifting (via the Intra-Extra Dimensional Set Shift Task) and response inhibition (via the Stop Signal Response Task). These domains were chosen as a result of previous literature showing impairments in these areas in subjects with impulsive behavior in the form of gambling disorder (Clark 2010; van Holst et al. 2010; Grant et al. 2011; Odlaug et al. 2011).

Cognitive Flexibility; Intra-extra Dimensional Set Shift Task (IED)

Participants are asked to learn, and then follow an underlying rule given by the computer. Once the participant demonstrates understanding of the rule, by answering six tasks correctly, the computer changes the underlying rule. At this point the subject must learn the new, computer determined underlying rule. Once the subject answers six tasks correctly, applying the new rule, the computer again changes the underlying rule. This process is repeated. There are a number of output measures, including the total number of adjusted errors (i.e. how many errors does the subject make before learning the new rule) and the number of errors the subject makes during specific portions of the task (Owen et al. 1991).

Response Inhibition; Stop Signal Task (SST)

This task examines the subject’s ability to inhibit a desired response. The computer presents the participant with an arrow pointing to the right or left. The subject must then press the matching arrow on the keyboard. However, at random, after presenting the participant with a right or left arrow, the computer will make a loud beeping sound. When the sound occurs the subject must refrain from pressing the matching arrow on the keyboard. The SST provides a variety of output measures. For the purpose of this study, the response time (SSRT) was analyzed. This output measures the time it takes for the subject to inhibit their desired motor decision to press the arrow on the keyboard (Aron 2007).

Statistical Analysis

Participants were divided into three groups: (1) non-treatment seeking pathologic gamblers (n = 94), (2) pathologic gamblers seeking and receiving psychotherapy for gambling (n = 106), (3) pathologic gamblers seeking and receiving medication for gambling (n = 680). An additional age-matched data set was created from this larger data set to eliminate the confounding variable of age (the non-treatment seeking pathologic gamblers were significantly younger than both treatment groups). This age-matched data set included only subjects from all three groups who were aged 20–29. The three age-matched groups were grouped in the same manner with n = 68, 11, and 52 respectively. Demographic, family and gambling history, clinical and cognitive variables were measured using Chi squared and analysis of variance tests where appropriate.

Ethical Issues

The Institutional Review Boards at the University of Chicago and the University of Minnesota approved the study and the informed consent procedures. All study procedures were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and all subjects provided voluntary, written informed consent after being explained all of the study procedures.

Results

We examined whether demographic and family history differences existed (Table 1) in regards to age, gender, education and race, as well as in general gambling information in a population of non-treatment seeking gamblers (n = 94), therapy seeking gamblers (n = 106) and medication seeking gamblers (n = 680). Significant differences existed in race (p < 0.001) with Caucasian individuals being more likely to seek therapy or medication treatment. Significant differences (p < 0.001) in age also existed between the three groups. However, this significant difference disappeared (p = 0.95) when a smaller, age-matched subset was created. The treatment seeking groups reported higher rates of maternal gambling problems (p = 0.047).

Those seeking treatment lost significantly more money in the past year when compared to the non-treatment seeking group (p < 0.001). Those seeking medication or therapy treatment were significantly more likely to report that they gambled to make money (p = 0.024) or escape from problems (p = 0.003), and they report more legal (p < 0.001) and social problems (p = 0.017) secondary to their gambling. Those individuals seeking therapy as treatment exhibited the highest levels of legal and social problems. Information pertaining to gambling behavior is presented in Table 2.

Comorbidities were also examined between groups (Table 3). Non-treatment seekers were significantly more likely to have a current or past major depressive episode (p < 0.001) while those seeking therapy were more likely to have comorbid general anxiety disorder (p = 0.007).

When examining clinical measures, significant differences existed in all 3 scales of the PG-YBOCS: urge, behavior and total scores (p < 0.001, Table 4). Those seeking medical treatment had higher scores than the other two groups. Those seeking therapy had higher scores than non-treatment seekers. A significant difference existed in non-planning impulsiveness (p = 0.002), with non-treatment seekers exhibiting lower scores. There were no group significant differences on any neurocognitive measure. Specific n-values for each variable are provided in Table 5.

Discussion

In confirmation of our first hypothesis, this study found significant differences in the obsessive–compulsive nature of the three groups as measured by the PG-YBOCS. Non-treatment seeking gamblers scored significantly lower than both therapy and medical treatment seeking gamblers in all three categories of the scale: urge, behavior and total score. Those seeking therapy scored in between non-treatment seeking gamblers and gamblers seeking medical treatment. This finding was true in both the large group and the smaller age matched analysis. This finding may signify a difference in the cognitive nature of disordered gamblers seeking treatment. While all three groups struggle to resist the impulse to gamble, the differences in PG-YBOCS scores may suggest treatment-seeking gamblers tend to gamble in a more compulsive manner. Such behavior could lead to increased financial losses, resulting in increased social, legal and or work problems, leading to the individual seeking treatment. Such a conclusion correlates with previous literature that has hypothesized a transformation from impulsive to compulsive behavior in pathologic gamblers (Brewer and Potenza 2008; Leeman and Potenza 2012), but contradicts another study that suggests gambling severity increases due to impulsivity changes (Blanco et al. 2009). This transformation may be a result of a neurological shift of control from the pre-frontal cortex to the dorsolateral striatum and putamen (Brewer and Potenza 2008; Holland 2004). Such a transition from impulsive to compulsive addictive behavior has been shown to exist in animal models and hypothesized for human addictions (Dalley et al. 2011).

Taken together, this finding seems to signify that gambling disorder lies on a continuum; gamblers seeking treatment appear to have a more severe form of the disease than disordered gamblers who do not seek treatment. If this is true, then one may hypothesize that the severity of gambling disorder may also be due to duration of illness. Interestingly, however, this study did not find this to be the case, contradicting our second hypothesis. Despite the larger sample showing medication seekers to have a significantly longer duration of illness, the significant difference between groups disappeared in the age-matched sample. Thus, an individual with new onset gambling disorder appears just as likely to seek treatment as an individual who has been diagnosed with gambling disorder for many years. This conclusion is supported by a recent study that found no correlation between duration of illness and gambling severity (Medeiros et al. 2017).

The results of this study also confirmed our third and fourth hypotheses that gamblers seeking treatment likely do so due to gambling related difficulties. Those receiving treatment, either therapy or medication, had significantly higher ratios of money lost to income, as well as increased legal problems. Treatment seekers were also significantly more likely to gamble to make money or to escape from problems, further supporting these findings. Previous research has shown severity of gambling to correlate with financial losses (Suurvali et al. 2012). This relationship signifies that the treatment seeking gamblers in this study were also more severe gamblers, supporting the hypothesis and the findings discussed prior.

Finally, this study found a significant difference between races in treatment seeking behavior amongst disordered gamblers. Caucasians were significantly more likely to seek treatment than African-American patients. This finding confirms many previous studies that have found similar patterns in psychiatric care (Broman 1987; Anglin et al. 2008; Snowden 2001). However, it contradicts another group of studies (Alegría et al. 2009; Broman 1987). While not a novel finding, this result supports previous research that has shown African American populations are less likely to seek mental health treatment than Caucasian populations. This study supports the need to include gambling disorder in this conversation.

There are a few limitations to this study that need to be noted. First, this study was unable to prove that any variable was causative in determining the grouping of subjects into their treatment-seeking category. While many of the correlative findings were significantly strong, it is possible the results may have been confounded by another variable. One of these potential confounding variables was age. We attempted to solve for this by creating an age-matched category to ensure statistically significant findings still held. However, it must be noted that the n value of the therapy-seeking group was small, n = 11, in comparison to the non-treatment seeking group and medication seeking group, n = 68 and n = 52, respectively. Finally, many of the variables examined in this analysis were self-reported values that were retrospectively volunteered (i.e. age of first gambling). Therefore, these values may be subject to recall bias.

In conclusion, this study adds to the literature by providing a better understanding of the differences between non-treatment seeking, therapy seeking and medication seeking gamblers. To our knowledge this is the only study to examine all three groups in a population of individuals diagnosed with gambling disorder. In support of our hypotheses, this study suggests that the three groups differ significantly in regards to the nature of their gambling behavior. Medication and therapy seeking gamblers were more likely to exhibit obsessive–compulsive tendencies, likely resulting in the increased legal and social problems seen in the medication-seeking group. Additional research studies attempting to better delineate the causative variables determining which group pathologic gamblers fall into should be pursued.

References

Alegría, A. A., Petry, N. M., Hasin, D. S., Liu, S. M., Grant, B. F., & Blanco, C. (2009). Disordered gambling among racial and ethnic groups in the US: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. CNS Spectrums, 14(3), 132–142.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5 ® ). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Anglin, D. M., Alberti, P. M., Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2008). Racial differences in beliefs about the effectiveness and necessity of mental health treatment. American Journal of Community Psychology, 42(1–2), 17–24.

Aron, A. R. (2007). The neural basis of inhibition in cognitive control. Neuroscientist, 13(3), 214–228.

Barnes, G. M., Welte, J. W., Hoffman, J. H., & Tidwell, M.-C. O. (2010). Comparisons of gambling and alcohol use among college students and noncollege young people in the United States. Journal of American College Health, 58(5), 443–452.

Blanco, C., Potenza, M. N., Kim, S. W., Ibáñez, A., Zaninelli, R., Saiz-Ruiz, J., et al. (2009). A pilot study of impulsivity and compulsivity in pathological gambling. Psychiatry Research, 167(1–2), 161–168.

Braun, B., Ludwig, M., Sleczka, P., Bühringer, G., & Kraus, L. (2014). Gamblers seeking treatment: Who does and who doesn’t? Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 3(3), 189–198.

Brewer, J. A., & Potenza, M. N. (2008). The neurobiology and genetics of impulse control disorders: Relationships to drug addictions. Biochemical Pharmacology, 75(1), 63–75.

Broman, C. L. (1987). Race differences in professional help seeking. American Journal of Community Psychology, 15(4), 473–489.

Clark, L. (2010). Decision-making during gambling: An integration of cognitive and psychobiological approaches. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B: Biological sciences, 365(1538), 319–330.

Dalley, J. W., Everitt, B. J., & Robbins, T. W. (2011). Impulsivity, compulsivity, and top-down cognitive control. Neuron, 69(4), 680–694.

Eysenck, S. B., Pearson, P. R., Easting, G., & Allsopp, J. F. (1985). Age norms for impulsiveness, venturesomeness and empathy in adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 6, 613–619.

Frisch, M. B. (2013). Evidence-based well-being/positive psychology assessment and intervention with quality of life therapy and coaching and the quality of life inventory (QOLI). Social Indicators Research, 114, 193–227.

Grant, J. E. (2008). Impulse control disorders: A clinician’s guide to understanding and treating behavioral addictions. New York, NY: WW Norton and Company.

Grant, J. E., Chamberlain, S. R., Odlaug, B. L., Potenza, M. N., & Kim, S. W. (2010a). Memantine shows promise in reducing gambling severity and cognitive inflexibility in pathological gambling: A pilot study. Psychopharmacology, 212(4), 603–612.

Grant, J. E., Chamberlain, S. R., Schreiber, L. R., Odlaug, B. L., & Kim, S. W. (2011). Selective decision-making in at-risk gamblers. Psychiatry Research, 189(1), 115–120.

Grant, J. E., Donahue, C. B., Odlaug, B. L., Kim, S. W., Miller, M. J., & Petry, N. M. (2009). Imaginal desensitization plus motivational interviewing for pathological gambling: Randomized controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry, 195(3), 266–267.

Grant, J. E., & Kim, S. W. (2006). Medication management of pathological gambling. Minnesota Medicine, 89(9), 44–48.

Grant, J. E., Kim, S. W., & Hartman, B. K. (2008). A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the opiate antagonist naltrexone in the treatment of pathological gambling urges. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69(5), 783–789.

Grant, J. E., Kim, S. W., & Odlaug, B. L. (2007). N-acetyl cysteine, a glutamate-modulating agent, in the treatment of pathological gambling: A pilot study. Biological Psychiatry, 62(6), 652–657.

Grant, J. E., Kim, S. W., Potenza, M. N., Blanco, C., Ibanez, A., Stevens, L., et al. (2003). Paroxetine treatment of pathological gambling: A multi-centre randomized controlled trial. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 18(4), 243–249.

Grant, J. E., Odlaug, B. L., Chamberlain, S. R., Hampshire, A., Schreiber, L. R., & Kim, S. W. (2013). A proof of concept study of tolcapone for pathological gambling: Relationships with COMT genotype and brain activation. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 23(11), 1587–1596.

Grant, J. E., Odlaug, B. L., Chamberlain, S. R., Potenza, M. N., Schreiber, L. R., Donahue, C. B., et al. (2014). A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of N-acetylcysteine plus imaginal desensitization for nicotine-dependent pathological gamblers. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 75(1), 39–45.

Grant, J. E., Odlaug, B. L., Potenza, M. N., Hollander, E., & Kim, S. W. (2010b). Nalmefene in the treatment of pathological gambling: Multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 197(4), 330–331.

Grant, J. E., & Potenza, M. N. (2006). Escitalopram treatment of pathological gambling with co-occurring anxiety: An open-label pilot study with double-blind discontinuation. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 21(4), 203–209.

Grant, J. E., Steinberg, M. A., Kim, S. W., Rounsaville, B. J., & Potenza, M. N. (2004). Preliminary validity and reliability testing of a structured clinical interview for pathological gambling. Psychiatry Research, 128(1), 79–88.

Hamilton, M. (1959). The assessment of anxiety states by rating. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 32, 50–55.

Hamilton, M. (1960). A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 23, 56–62.

Harries, M. D., Redden, S. A., Leppink, E. W., Chamberlain, S. R., & Grant, J. E. (2017). Sub-clinical alcohol consumption and gambling disorder. Journal of Gambling Studies, 33(2), 473–486.

Hodgins, D. C., & el-Guebaly, N. (2000). Natural and treatment-assisted recovery from gambling problems: A comparison of resolved and active gamblers. Addiction, 95(5), 777–789.

Holland, P. C. (2004). Relations between Pavlovian-instrumental transfer and reinforcer devaluation. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 30(2), 104–117.

Kim, S. W., Grant, J. E., Adson, D. E., & Shin, Y. C. (2001). Double-blind naltrexone and placebo comparison study in the treatment of pathological gambling. Biological Psychiatry, 49(11), 914–921.

Kim, S. W., Grant, J. E., Adson, D. E., Shin, Y. C., & Zaninelli, R. (2002). A double-blind placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of paroxetine in the treatment of pathological gambling. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 63(6), 501–507.

Leeman, R. F., & Potenza, M. N. (2012). Similarities and differences between pathological gambling and substance use disorders: A focus on impulsivity and compulsivity. Psychopharmacol., 219(2), 469–490.

Lorains, F. K., Cowlishaw, S., & Thomas, S. A. (2011). Prevalence of comorbid disorders in problem and pathological gambling: Systematic review and meta-analysis of population surveys. Addiction, 106(3), 490–498.

Medeiros, G. C., Redden, S. A., Chamberlain, S. R., & Grant, J. E. (2017). Gambling disorder: Association between duration of illness, clinical and neurocognitive variables. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 31, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.029.

Nautiyal, K. M., Okuda, M., Hen, R., & Blanco, C. (2017). Gambling disorder: An integrative review of animal and human studies. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1394(1), 106–127.

Odlaug, B. L., Chamberlain, S. R., Kim, S. W., Schreiber, L. R., & Grant, J. E. (2011). A neurocognitive comparison of cognitive flexibility and response inhibition in gamblers with varying degrees of clinical severity. Psychological Medicine, 41(10), 2111–2119.

Owen, A. M., Roberts, A. C., Polkey, C. E., Sahakian, B. J., & Robbins, T. W. (1991). Extra-dimensional versus intra-dimensional set shifting performance following frontal lobe excisions, temporal lobe excisions or amygdalo-hippocampectomy in man. Neuropsychologia, 29(10), 993–1006.

Pallanti, S., DeCaria, S. M., Grant, J. E., Urpe, M., & Hollander, E. (2005). Reliability and validity of the pathological gambling adaptation of the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (PG-YBOCS). Journal of Gambling Studies, 21(4), 431–443.

Patton, J. H., Stanford, M. S., & Barratt, E. S. (1995). Factor structure of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 51, 768–774.

Petry, N. M., Blanco, C., Stinchfield, R., & Volberg, R. (2013). An empirical evaluation of proposed changes for gambling diagnosis in the DSM-5. Addiction, 108(3), 575–581.

Pulford, J., Bellringer, M., Abbott, M. W., Clarke, D., Hodgins, D. C., & Williams, J. (2009). Barriers to help-seeking for a gambling problem: The experiences of gamblers who have sought specialist assistance and the perceptions of those who have not. Journal of Gambling Studies, 25(1), 33–48.

Sheehan, D. V., Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, K. H., Amorim, P., Janavs, J., Weiller, E., et al. (1998). The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 20(22–23), 34–57.

Slutske, W. S. (2006). Natural recovery and treatment-seeking in pathological gambling: Results of two U.S. national surveys. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(2), 297–302.

Snowden, L. (2001). Barriers to effective mental health services for African Americans. Mental Health Services Research, 3(4), 181–187.

Suurvali, H., Hodgins, D. C., Toneatto, T., & Cunningham, J. A. (2012). Motivators for seeking gambling-related treatment among Ontario problem gamblers. Journal of Gambling Studies, 28(2), 273–296.

van Holst, R. J., van den Brink, W., Veltman, D. J., & Goudriaan, A. E. (2010). Brain imaging studies in pathological gambling. Current Psychiatry Reports, 12(5), 418–425.

Weinstock, J., Burton, S., Rash, C. J., Moran, S., Biller, W., Krudelbach, N., et al. (2011). Predictors of engaging in problem gambling treatment: Data from the West Virginia Problem Gamblers Help Network. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 25(2), 372–379.

Williams, R., Volberg, R., & Stevens, R. M. G. (2012). The population prevalence of problem gambling: Methodological influences, standardized rates, jurisdictional differences and worldwide trends. Report prepared for the Ontario Problem Gambling Research Center and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Mr. Michael Harries and Ms. Sarah Redden report no conflicts of interest. Dr. Jon Grant currently has research grants from the National Center for Responsible Gaming, Brainsway, the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, the TLC Foundation for Body Focused Repetitive Behaviors, Forest Takeda and Psyadon Pharmaceuticals. He receives yearly compensation from Springer Publishing for acting as Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Gambling Studies and has received royalties from Oxford University Press, American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc., Norton Press, and McGraw Hill.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Harries, M.D., Redden, S.A. & Grant, J.E. An Analysis of Treatment-Seeking Behavior in Individuals with Gambling Disorder. J Gambl Stud 34, 999–1012 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-017-9730-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-017-9730-2