Abstract

This study examined the relationships between risk (i.e., gambling cognitions, gambling urges, psychological distress) and protective factors (i.e., life satisfaction, resilience, gambling refusal self-efficacy) and problem gambling among 310 Singaporeans aged between 18 and 73 years. Data on demographics, risk and protective factors, and gambling behavior were collected through electronic and paper surveys. Hierarchical multiple regression was employed to assess the contributions of the risk and protective factors in predicting problem gambling. Three risk factors (i.e., gambling cognitions, gambling urges, psychological distress) and two protective factors (i.e., resilience, gambling refusal self-efficacy) were found to significantly and uniquely predict problem gambling. Furthermore, the risk factors significantly interacted with the protective factors to moderate gambling severity. Gambling refusal self-efficacy shows significant protective effects against problem gambling, while the effects of resilience on gambling vary across settings. Both factors need to be taken into account in the understanding of problem gambling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In many modern societies, gambling is a socially acceptable form of entertainment or leisure activity (Loo et al. 2008). Recently, more governments are legalizing gambling, particularly in Asian regions, thus making gambling more accessible (Lee 2005). This is an area of concern, considering possible increases in problem gambling following rising gambling accessibility (Jacques et al. 2000).

In Singapore, from a study using self-report data on the diagnostic criteria for pathological gambling in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), 1.2–1.4 % of Singaporeans were found to present with probable pathological gambling, and 1.2–1.7 % were categorized under the less severe category (APA 1994; MCYS 2008, 2011). Among gambling patrons residing in Singapore, a majority was also observed to be Chinese (57–62 %), male (87.3 %), and having a secondary education or less (67.4 %; MCYS 2008, 2011; Teo et al. 2007). While most subjects started gambling in their early twenties (M age of onset = 22.9, SD = 9.0), the mean age of treatment-seeking was 42.5 (SD = 10.2), suggesting a lengthy delay between gambling onset and the decision to seek help (Teo et al. 2007).

Apart from the above-mentioned factors, other risk factors and correlates that have been implicated in problem gambling include demographic variables (e.g., male gender, middle-aged; Teo et al. 2007), personality traits (e.g., negative emotionality, constraint, higher risk-taking and impulsivity, neuroticism, openness, need for stimulus; Slutske et al. 2005; Myrseth et al. 2009; Ozorio and Fong 2004), personality disorders (e.g., Borderline, Antisocial; Sacco et al. 2008), cognitive errors (e.g., illusion of control, magical thinking; Oei et al. 2008), mood disorders and psychological distress (Kim et al. 2006; Raylu and Oei 2002), gambling motivations (Oei and Raylu 2007; VCGA 2000), gambling urges (Potenza et al. 2003), early onset of gambling experiences, access to gambling venues (Derevenksy and Gupta 2004; Dickson et al. 2002), participation in casino gambling and more types of gambling, and alcohol abuse (Welte et al. 2004), and delay in seeking treatment (Loo et al. 2008).

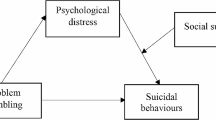

Recently, more attention has been paid to three specific risk factors, i.e., gambling cognitions, gambling urges, and psychological states (e.g., depression and anxiety). These factors were implicated in the initiation and maintenance of problem gambling and to be responsive towards the treatment of pathological gambling (Ladouceur et al. 1998; Raylu and Oei 2004a, b; Sylvain et al. 1997). On the other hand, compared to risk factors, far less is known about the contributive roles of protective factors (Fraser et al. 1999). Accordingly, effective protective factors minimize the negative impact of gambling behaviors and problem gambling (Dickson et al. 2008).

Among studies using adult populations, effective protective factors that have been implicated include religiosity (Cunningham-Williams et al. 2005; Hodge et al. 2007), personal characteristics such as having a tertiary or higher level of education, a better life satisfaction, engagement in non-gambling activities, and concern for negative impact of gambling (Lai 2006; VCGA 2000), environmental factors like family cohesion and school connectedness (Dickson et al. 2002), and personal resources such as self-reported resilience and self-efficacy (Casey et al. 2008; DiClemente et al. 1995; Fraser et al. 1999). For example, self-perceived resilient youth reported less gambling severity than those who viewed themselves as less resilient (Lussier et al. 2007). In addition, high self-efficacy has been observed to contribute positively towards the treatment of other addictive behaviors e.g., alcohol addiction (Hasking and Oei 2007).

Overall, the literature presented more studies on risk factors than protective factors. Furthermore, most gambling research has been done in Western populations; Asian studies in gambling are limited, especially among Chinese populations. Loo et al. (2008) observed increasing prevalence estimates (currently 2.5–4.0 %) of problem gamblers over time in a comprehensive review of gambling among the Chinese. Although findings from studies in Western countries (i.e., USA, Canada, and Australia) are useful as a reference, the extent to which these results are applicable to Asian context, particularly in Singapore, remains uncertain. Thus, the present study aimed to investigate the effects of risk and protective factors contributing towards the development of gambling behaviors and resulting gambling-related problems in the Singapore setting. It was hypothesized that the identified risk and protective factors would be positively and negatively related to problem gambling severity as measured by frequency of gambling-related problems respectively. It was further hypothesized that protective factors would moderate the effects of risk factors on the development of gambling behaviors and resulting gambling-related problems. Specifically, having greater life satisfaction was expected to reduce problem gambling severity among individuals with stronger gambling urges and higher levels of psychological distress, as being satisfied with one’s life implies having less of a need to acquire satisfaction through gambling (e.g., by satisfying urges or relieving psychological distress). Secondly, perceiving oneself as being resilient was expected to reduce the impact of gambling urges and psychological distress on problem gambling severity. Resilience connotes inner strength, competence, and the ability to cope effectively when faced with adversity (Wagnild and Collins 2009), and self-perceived resilient individuals are expected to be able to resist the urge to gamble as well as cope with psychological distress without resorting to unconstructive gambling activity. Finally, having greater gambling refusal self-efficacy was expected to reduce problem gambling severity in the presence of elevated gambling urges, gambling cognitions, and psychological distress as an internalized ability to refuse gambling could operate under any circumstances.

Method

Participants

310 individuals (155 university students, 155 members of the public) living in Singapore participated in the study. Sample demographics are presented in Table 1.

Of the sample, 30.6 % were male and 69.4 % were female. The mean age of participants was 27.6 (SD = 11.4) with ages ranging from 18 to 73 years. In terms of ethnicity, 91.6 % of the sample was Chinese, 1.3 % was Malay, 4.2 % was Indian, 2.3 % consisted of other ethnicities (e.g., Japanese, Javanese, Eurasian), and 0.6 % did not report their ethnicity (see Table 1). The percentage of participants who indicated their education to be secondary school equivalent (i.e.,, 10 years or less) was 7.1 %; post-secondary equivalent was 55.2 %; university degree and above was 34.2 %, and other qualifications was 2.9 %. 73.9 % of the participants were never married, 7.1 % were married with no children, 17.1 % were married with children, and 1.3 % were divorced/separated. Most of the participants were students (53.5 %), while others were working full or part-time (42.3 %), homemakers (0.6 %), retired (2.3 %), or unemployed (0.6 %; see Table 1).

Materials

Canadian Problem Gambling Index (CPGI)

The CPGI is a 42-item, multi-component problem gambling screening tool for use in general populations. 9 out of 42 items (e.g., “Has your gambling caused any financial problems for you or your household?”) are scored, on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 (Never) to 3 (Almost always), with higher scores indicating more gambling-related problems and hence, implying higher problem gambling severity (Ferris and Wyne 2001; Smith and Wynne 2002). The scale demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .84) and criterion-related validity (Wiebe et al. 2001) among 193 university students in Singapore. The CPGI has been found previously to be valid and reliable in Chinese (Arthur et al. 2008). Cronbach’s α for the current sample was .75.

Gambling Related Cognitions Scale (GRCS)

The GRCS is a five-factor, 23-item questionnaire measuring distorted beliefs among gamblers (e.g., “I have specific rituals and behaviors that increase my chances of winning”; Raylu and Oei 2004b). Responders’ level of agreement with each statement was rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), with higher scores indicating more gambling-related distorted beliefs. The scale has shown high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .93), with each subscale demonstrating moderate to high reliability (Cronbach’s α ranged from .77 to .91). A Chinese-translated version of the scale was reported to be valid and reliable (Oei et al. 2007a). Internal consistency for the current sample was good (Cronbach’s α = .93).

Gambling Urge Scale (GUS)

The GUS is a six-item questionnaire measuring gambling urges (e.g., “I crave a gamble right now”; Raylu and Oei 2004b). Responders’ level of agreement with each statement was rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), and higher scores indicate higher levels of gambling urges. The GUS has been shown to have high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .81) and good reliability (Raylu and Oei 2004b). Similar to the GRCS, a Chinese translation of the GUS was also found to be valid and reliable among the Chinese (GUS-C; Oei et al. 2007b). Internal consistency for the current sample was good (Cronbach’s α = .94).

Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21)

The DASS-21 is a 21-item questionnaire screen for the affective states of depression, anxiety and stress (7 items per subscale; Lovibond and Lovibond 1995). Examples of items include “I couldn’t seem to experience any positive feelings at all” (Depression subscale), “I felt I was close to panic” (Anxiety subscale), and “I found it hard to unwind” (Stress subscale). Responders rate their degree of agreement to each statement on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied to me very much, or most of the time), and higher scores indicating greater psychological distress. The validity (r = .84) and reliability (i.e., Cronbach’s α of 0.94, 0.87 and 0.91 for Depression, Anxiety and Stress subscales respectively) indices are well-placed; Oei et al. (2013) affirmed the scales’ validity and reliability on Asian samples. Internal consistency for the current sample was good (Cronbach’s α = .93).

Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS)

The SWLS is a 5-item measure of global life satisfaction (e.g., “The conditions of my life are excellent”; Pavot and Diener 2008). Responders rate their agreement with each statement on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The scale demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .87). The SWLS was validated in a Malaysian sample (Sinniah et al. 2013). Internal consistency for the current sample was good (Cronbach’s α = .87).

Resilience Scale (RS)

The RS is a 26-item measure of overall resilience (e.g., “When I’m in a difficult situation, I can usually find my way out of it”; Wagnild and Young 1993). Responders rate their agreement with each item on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). A review of 12 completed studies that used the RS found Cronbach’s α coefficients to range from .72 to .94, thereby supporting the internal consistency of the RS (Wagnild and Collins 2009). Internal consistency for the current sample was good (Cronbach’s α = .94).

Gambling Refusal Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (GRSEQ)

The GRSEQ is a four-factor, 25-item measure of one’s ability to refuse gambling opportunities in given situations (e.g., “When I’m in places where I usually gamble”; Casey et al. 2008). Respondents rate their confidence to refuse gambling on an 11-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (No confidence, cannot refuse) to 100 (Extreme confidence, certainly can refuse) with 10-point subdivisions. Confirmatory factor analysis revealed a good fit of a 4-factor model in a population of non-clinical and problem gamblers, with composite and factor scores showing high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α ranging from .92 to .98; Casey et al. 2008). Internal consistency for the current sample was excellent (Cronbach’s α = .98).

Procedure

Ethical clearance was obtained from the National University of Singapore Institutional Review Board (NUS IRB). Participants were recruited via advertisements (i.e., flyers and the World Wide Web) and by distribution of questionnaires through privatized companies. Participants either completed a hardcopy questionnaire package, or completed the questionnaires online. Participation was completely voluntary and participants were assured of total anonymity and confidentiality. Participants took an average of 45 min to complete the questionnaires.

Data Analysis

Data was analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, Inc. 1998). Prior to analyses, the data was examined for inaccurate data entry, missing values, and the assumptions of multivariate analysis. Minor and non-systematic missing data was found for approximately 6 % of the individuals and these were substituted by sample means. Using a p < .001 criterion for Mahalanobis distance, six outliers were identified and removed from subsequent analyses. Collinear relationships between study variables were assessed using multiple regression analysis and tolerance values for all variables were above 0.10, indicating no violation of the assumption. A hierarchical multiple regression (HMR) analysis was used to assess the predictive contribution of the six gambling risk and protective factors (i.e.,, gambling cognitions, gambling urges, psychological states, life satisfaction, resilience, gambling refusal self-efficacy) on problem gambling severity as measured by the CPGI as well as the interactions between risk and protective factors. As problem gambling severity has been reported to vary accordingly to gender and age in previous research, these variables were controlled for in all analyses (Bruce and Johnson 1994; Lai 2006). Bivariate correlation analysis was also used to determine the strength and direction of the relationships between the variables used in the HMR analysis.

Results

Correlations Between Gambling Correlates (Risk and Protective Factors) and Gambling Behavior

Means, standard deviations, Cronbach’s α, and correlations of the scales used are presented in Table 2.

Bivariate correlation analysis was used to examine the relationships among the assessed variables. As expected, results indicated that all risk factors (i.e.,, Gambling Cognitions, Gambling Urges, and Psychological States) had a significant positive correlation with problem gambling severity (i.e.,, CPGI scores), confirming the relationships found in previous studies with both Chinese and Caucasian samples (e.g., Raylu and Oei 2004b, c; Oei et al. 2007a, b, 2008; see Table 2). The hypothesized protective factors (i.e.,, life satisfaction and gambling refusal self-efficacy) were significantly negatively correlated with problem gambling severity. However, self-perceived resilience, a hypothesized protective factor, did not correlate significantly with problem gambling severity. Nonetheless, self-perceived resilience had significant negative correlations with two risk factors (i.e.,, Gambling Cognitions, Psychological States) and a significant positive correlation with one protective factor (i.e., life satisfaction).

Predictability of Risk and Protective Factors on Problem Gambling Severity

Effects of Protective Factors

The contribution of protective factors above and beyond that of risk factors were examined using hierarchical regression analyses. The HMR results (see Table 3) revealed that Gender entered in Step 1 explained 2.3 % of the variance. After the risk factors (i.e.,, Gambling Cognitions, Gambling Urges, and Psychological States) were entered in step 2, the model accounted for 27.4 % of the variance in problem gambling severity, R 2 change = .25, F change (3, 305) = 35.16, p < .001. When the protective factors were entered in step 3, the model explained 31.2 % of the variance in problem gambling severity, R 2 change = .04, F change (3, 302) = 35.16, p < .01. When the 9 two-way interactions were entered at Step 4, the model explained 42.5 % of the variance in problem gambling severity, R 2 change = .11, F change (9, 293) = 6.37, p < .001. The HMR model was significant, F(16, 293) = 13.52, p < .001, and all the risk factors and two protective factors (i.e.,, resilience, and gambling refusal self-Efficacy) were found to significantly predict problem gambling severity. The unique variance in problem gambling severity scores accounted for by each factor was 2.0, 3.4, 1.3, 1.6, and 0.9 %, respectively. Furthermore, five interactions between protective factors and risk factors (i.e.,, Life Satisfaction × Gambling Urges, Resilience × Gambling Urges, Resilience × Psychological States, Gambling Refusal Self-Efficacy × Gambling Urges, Gambling Refusal Self-Efficacy × Psychological State) were found to be significant. The unique variance in problem gambling severity scores contributed by each interaction was 0.8, 2.1, 1.5, 0.9, and, 3.0 % respectively.

Effects of Risk Factors

A second HMR assessed the unique contributions of risk factors after protective factors were taken into account. The independent variables (IVs) were entered into the second HMR model in the following order: Gender (Step1); protective factors (Step 2), risk factors (Step 3); and the two-way interactions between each protective factor and risk factor (Step 4; see Table 3).

Similar to the previous HMR model, the results showed this model to be significant, F(16, 293) = 13.52, p < .001. The same five risk and protective factors identified in the first model (i.e.,, Gambling Cognitions, Gambling Urges, Psychological States, Resilience, Gambling Refusal Self-Efficacy) as well as the same five interactions (i.e., Life Satisfaction × Gambling Urges, Resilience × Gambling Cognitions, Resilience × Psychological States, Gambling Refusal Self-Efficacy × Gambling Urges, Gambling Refusal Self-Efficacy × Psychological States) contributed significantly to predicting problem gambling severity scores, with each factor accounting for similar degree of variance. In summary, the risk factors, the protective factors, and a number of their interactions contributed significantly to predicting problem gambling severity.

Analysis of Moderator Interactions

To examine the patterns for all significant interactions, regression slopes were plotted using values of problem gambling severity (i.e.,, CPGI scores) that were predicted from representative groups of participants who scored at the mean value, one standard deviation above the mean, and one standard deviation below the mean, of the respective risk and protective factors. Data above or below one standard deviation of the mean were not considered for moderator analyses to minimize effects of skewed data. Following procedures underlined by Aiken and West (1991), predicted values were calculated by multiplying the unstandardized regression coefficients for each variable by the appropriate value, summing the products, and then adding the value of the constant. In addition, each regression line was tested in an analysis of simple slopes to see if the slope differed from zero. Finally, the slopes were compared to determine whether they differed significantly from one another.

As predicted, the Life Satisfaction × Gambling Urges interaction was significant, β = −0.13, t(309) = −2.04, p < .05 [see bold lines in Graph (2), Fig. 1]. Analysis of simple slopes indicated that individuals who were more satisfied with life reported more gambling-related problems (hence, implying higher problem gambling severity) when they had stronger gambling urges than when their gambling urges were weaker, β = 0.26, t(309) = 2.89, p < .01. Similarly, those who were less satisfied with life reported more gambling-related problems when their gambling urges were strong than when these urges were weak, β = 0.26, t(309) = 2.89, p < .01. Importantly, at higher levels of gambling urges, individuals with higher life satisfaction were less likely to report gambling-related problems than individuals with lower life satisfaction, β = −0.20, t(309) = −2.85, p < .01. In contrast, self-reported gambling-related problems did not vary according to life satisfaction levels when gambling urges were weak, β = 0.01, t(309) = 0.18, p = .86. This finding suggests that having greater life satisfaction provides a buffer against the negative effects of problem gambling that is motivated by the urge to gamble, although it may not cancel out the effects of gambling urges completely.

Contrary to study hypotheses, self-perceived resilience significantly moderated the effects of gambling cognitions on problem gambling severity, but did not moderate the effects of gambling urges on problem gambling severity significantly. Specifically, the Resilience × Gambling Cognitions interaction was significant, β = 0.21, t(309) = 3.27, p < .01 [see Graph (3) in Fig. 1]. Analysis of simple slopes indicated that individuals with high self-perceived resilience reported more gambling-related problems when gambling cognitions were stronger than when they were weaker, β = 0.39, t(309) = 4.22, p < .001. In contrast, those with low self-perceived resilience did not differ in their report of gambling-related problems according to the strength of their gambling cognitions, β = −0.01, t(309) = −0.17, p = .87. At high levels of gambling cognitions, individuals with high self-perceived resilience reported more gambling-related problems than those who viewed less of themselves, β = 0.35, t(309) = 3.98, p < .001. Problem gambling severity did not vary according to self-perceived resilience when gambling cognitions were low, β = −0.05, t(309) = -0.71, p = .48. These findings suggest that perceiving oneself as being resilient may precipitate gambling-related problems among individuals whose erroneous beliefs about gambling are strong, but does not affect that of individuals with weak gambling cognitions.

The Resilience × Psychological Distress interaction was also significant, β = 0.16, t(309) = 2.74, p < .01, although not in the expected direction as well [see bold lines in Graph (1), Fig. 1]. Analysis of simple slopes indicated that individuals with high self-perceived resilience reported more gambling-related problems when their levels of depression, anxiety and stress were high than when they were lower on these psychological states, β = 0.28, t(309) = 3.72, p < .001. In contrast, individuals with low self-perceived resilience did not differ in their report of gambling —related problems according to psychological distress, β = −0.01, t(309) = −0.07, p = .94. Contrary to expectations, at high levels of depression, anxiety and stress, individuals with high self-perceived resilience reported more gambling-related problems than those with low self-perceived resilience, β = 0.29, t(309) = 4.24, p < .001. Problem gambling severity did not vary according to resilience when psychological distress was at low levels, β = 0.01, t(309) = 0.07, p = .94. This finding, similar to the previous one, indicates that perceiving oneself as resilient may promote problematic gambling behaviors when in greater psychological distress. On the other hand, perceiving oneself as less resilient may lead one to refrain from engaging in problematic gambling behaviors regardless of psychological distress levels.

There was a significant Gambling Refusal Self-Efficacy × Gambling Urges interaction, β = 0.221, t(309) = 2.16, p < .05, in an unexpected direction [see dashed lines in Graph (2), Fig. 1]. Analysis of simple slopes indicated that individuals high in gambling refusal self-efficacy reported more gambling-related problems when their urge to gamble was strong than when it was weak, β = 0.50, t(309) = 3.57, p < .001. Likewise, individuals who were low in their perceived ability to refuse gambling opportunities reported less gambling-related problems when their urge to gamble was stronger, β = −0.24, t(309) = 4.09, p < .001. Interestingly, at high levels of gambling urge, individuals who could readily refuse to gamble did not differ in self-reported gambling-related problems from individuals with lower self-efficacy to refuse gambling, β = 0.01, t(309) = 0.18, p = .86. However, at low levels of gambling urge, individuals with higher gambling refusal self-efficacy reported less gambling-related problems as compared to individuals with lower gambling refusal self-efficacy. The finding is intriguing as it suggests refusal self-efficacy to be a protective factor for those reporting little internalized desire to gamble, despite facing external pressures to do so (e.g., peer gambling).

The Gambling Refusal Self-Efficacy × Psychological Distress interaction was significant, β = −0.20, t(309) = −3.93, p < .001, in the expected direction [see dashed lines in Graph (1), Fig. 1]. Analysis of simple slopes indicated that individuals high in gambling refusal self-efficacy did not differ in their report of gambling-related problems according to levels of depression, anxiety and stress, β = −0.05, t(309) = −0.68, p = .50. In contrast, individuals who were low in their perceived ability to refuse gambling opportunities reported more gambling-related problems when they are more psychologically distressed, β = −0.32, t(309) = 4.58, p < .001. As expected, at high levels of psychological distress, individuals who could refuse to gamble more readily reported less gambling-related problems than individuals with lower self-efficacy to refuse gambling, β = −0.30, t(309) = −4.48, p < .001. In contrast, problem gambling severity did not vary with gambling refusal self-efficacy when psychological distress was low, β = 0.08, t(309) = 1.02, p = .31. These findings suggest that gambling refusal self-efficacy cancels out the effects of psychological distress that trigger problematic gambling behaviors (e.g., distress–relieving, distraction from life difficulties), thus acting as a protective factor against problem gambling.

Discussion

Direct and Moderating Effects of Protective Factors

The major findings from this study were that all the risk and protective factors except for life satisfaction were significantly and directly related to problem gambling severity. Significant interactions between risk and protective factors also demonstrated moderating effects of protective factors (i.e.,, Resilience, Gambling Refusal Self-Efficacy, and Life Satisfaction) on risk factors (i.e.,, Gambling Cognitions, Gambling Urges, Psychological States). In addition, resilience and gambling refusal self-efficacy contributed uniquely to the prediction of problem gambling severity, after the effects of risk factors were taken into account. Specifically, gambling refusal self-efficacy was observed to negate the effects of psychological distress and to reduce frequency of gambling-related problems among individuals with minimal gambling urges. Having higher life satisfaction also reduced the likelihood of experiencing gambling-related problems when gambling urges were strong. Lastly, resilience was found to increase frequency of gambling-related problems among individuals with strong erroneous gambling beliefs or elevated psychological distress. This runs contrary to previous research and warrants some discussion (Lussier et al. 2007).

One possibility is that the study involved a community sample whose problem gambling severity was generally not pathological. That is, although resilient individuals tended to gamble more under certain circumstances, they were able to regulate and limit their gambling behaviors and minimize resulting gambling-related problems. Based on recommended cut-offs for CPGI scores (Ferris and Wyne 2001), only two individuals (0.6 %) in the sample were classified as problem gamblers. Future studies could investigate the role of resilience in a sample of pathological gamblers, in view of previous findings demonstrating its importance in the prevention, treatment, recovery and relapse prevention of other addictive disorders (Zucker et al. 2003; Hall and Webster 2007; Robitschek and Kashubeck 1999). A second possibility relates to the role of culture. The present sample consisted mostly of Chinese living in Singapore (91.6 %). This is an important consideration given that gambling is a socially accepted communal entertainment among Chinese around the world (Loo et al. 2008). It is likely that resilient individuals (whose relationships with their families are stronger) within a predominantly Chinese population are more accepting of gambling and participate in gambling activities as a common family or community activity (Springer and Phillips 1992). This may not be unusual in Singapore as gambling opportunities increase over time (Lee 2005; Lim and Ong 2012). In the present sample, it is suggested that viewing oneself as resilient provides a false sense of confidence, making one more confident of winning or recouping losses when gambling triggers (i.e.,, gambling cognitions, psychological distress) are strong. On the other hand, less resilient individuals may feel less confident of winning under any circumstances, and, hence, abstain from gambling altogether. Further studies are needed to investigate the mechanism by which resilience impacts upon gambling behaviors and its resulting problems.

Notably, the present results differed from the findings of Lussier et al. (2007) who demonstrated protective effects of resilience in youths at risk of problem gambling. This could be because Lussier et al. (2007) incorporated the effects of internalized risk factors in defining resilience while the present study did not. Thus, definitional differences in resilience exist between both studies. Notwithstanding this, in the present study, those who scored higher on both resilience and the risk factors tended to gamble more than those who did not. Another reason for the observed differences in findings relates to the measurements of resilience. In Lussier et al. (2007), resilience as measured on the IPFI included constructs of social bonding and competence. The Resilience Scale (Wagnild and Young 1993) used in this study focused more closely on personal competence than interpersonal interactions. Therefore, the two measures may be measuring somewhat different constructs. Future research could explore the different definitions and measurements of the resilience construct. A third reason for the discrepancy may be related to demographic differences between the samples. Lussier et al. (2007) was conducted in a largely Caucasian sample of Canadian youth aged between 12 and 19 years. The present study was based largely on a Chinese sample of adults aged between 18 and 73 years. Differences in geographical location, culture and age may explain the discrepant findings. In summary, the differences in findings between the present study and Lussier et al. (2007) may be accounted for by a combination of definitional, measurement, and population differences. With the research of resilience still in its infancy, future studies are needed to investigate and understand these differences.

In general, direct relationships between risk factors and gambling-related problems were consistent with previous literature. Similarly, the moderating effects of protective factors, specifically life satisfaction and gambling refusal self-efficacy, on risk factors in problem gambling were consistent with the literature.

Limitations and Future Directions

Firstly, the present study used cross-sectional data and, thus, associative inferences can be made at best. It would be useful for future research to examine gambling risk and protective factors longitudinally to verify causal links between these factors and gambling outcomes, particularly in a clinical sample. Secondly, the sample consisted mainly of Chinese (91.6 %), females (69.4 %) and students (53.5 %). Given that pathological gamblers among Chinese were mainly middle-aged males, some caution is to be taken for the present findings (Teo et al. 2007; Volberg 1996).

In light of the present findings on resilience and problem gambling severity, future research should examine the role of culture in problem gambling (Raylu and Oei 2004a). It is possible that family and peer connectedness mediates the relationship between resilience and problem gambling in societies where gambling is more socially accepted. Additionally, it is suggested that resilient individuals identify more strongly with their ethnic identity; this may incline resilient Chinese individuals who are well integrated into the community to engage in more gambling activities. For instance, using a sample of 2,272 older Chinese in Canada, Lai (2006) showed that having more social support and a stronger identification with the Chinese ethnic identity increased one’s risk of problem gambling among the older Chinese. Subsequent gambling research should therefore investigate the roles and functions of resilience across cultures.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrated the protective function of gambling-refusal self-efficacy and life satisfaction with respect to gambling cognitions, gambling urges, and psychological distress. The findings also raised the possibility that being resilient may put one at risk of engaging in more gambling behaviors that may seed gambling-related problems under certain conditions, although not necessarily to the extent that one becomes a problem gambler.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Arthur, D., Tong, W. L., Chen, C. P., Hing, A. Y., Sagara-Rosemeyer, M., Kua, E. H., et al. (2008). The validity and reliability of four measures of gambling behavior in a sample of Singapore university students. Journal of Gambling Studies, 24, 451–462.

Bruce, A. C., & Johnson, J. E. V. (1994). Male and female betting behavior: New perspectives. Journal of Gambling Studies, 10, 183–198.

Casey, L. M., Oei, T. P. S., Melville, K. M., Bourke, E., & Newcombe, P. A. (2008). Measuring self-efficacy in gambling: The gambling refusal self-efficacy questionnaire. Journal of Gambling Studies, 24, 229–246.

Cunningham-Williams, R. M., Grucza, R. A., Cottler, L. B., Womack, S. B., Books, S. J., Przybeck, T. R., et al. (2005). Prevalence and predictors of pathological gambling: results from the St. Louis personality, health and lifestyle (SLPHL) study. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 39, 377–390.

Derevenksy, J., & Gupta, R. (2004). Adolescents with gambling problems: a review of our current knowledgeg. E-Gambling The Electronic Journal of Gambling Issues, 10, 119–140.

Dickson, L., Derevensky, J., & Gupta, R. (2002). The prevention of youth gambling problems: A conceptual model. Journal of Gambling Studies, 18, 97–159.

Dickson, L., Derevensky, J., & Gupta, R. (2008). Youth gambling problems: Examining risk and protective factors. International Gambling Studies, 8(1), 25–47.

DiClemente, C. C., Fairhurst, S. K., & Piotrowski, N. A. (1995). Self-efficacy and addictive behaviour. In J. E. Maddux (Ed.), Self-efficacy, adaptation, and adjustment; theory, research, and application (pp. 109–138). New York: Plenum Press.

Ferris, J., Wyne, H. (2001). The Canadian problem gambling index: Final report. Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse, February.

Fraser, M. W., Richman, J. M., & Galinsky, M. J. (1999). Risk, protection, and resilience: Toward a conceptual framework for social work practice. Social Work Research, 23, 131–143.

Hall, C. W., & Webster, R. E. (2007). Multiple stressors and adjustment among adult children of alcoholics. Addiction Research and Theory, 15, 425–434.

Hasking, P. A., & Oei, T. P. (2007). Alcohol expectancies, self-efficacy and coping in an alcohol dependent sample. Addictive Behaviors, 32, 99–113.

Hodge, D. R., Andereck, K., & Montoya, H. (2007). The protective influence of spiritual-religious lifestyle profiles on tobacco use, alcohol use, and gambling. Social Work Research, 31, 2007.

Jacques, C., Ladouceur, R., & Ferland, F. (2000). Impact of availability on gambling: A longitudinal study. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 45, 810–815.

Kim, S. W., Grant, J. E., Eckert, E. D., Faris, P. L., & Hartman, B. K. (2006). Pathological gambling and mood disorders: Clinical associations and treatment implications. Journal of Affective Disorders, 92, 109–116.

Ladouceur, R., Sylvain, C., Letarte, H., & Giroux, I. (1998). Cognitive treatment of pathological gamblers. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36, 1111–1119.

Lai, D. W. L. (2006). Gambling and the older Chinese in Canada. Journal of Gambling Studies, 22, 121–141.

Lee, M. (2005). The role of local government in gambling expansion in British Columbia (Doctoral dissertation), Department of Political Science-Simon Fraser University.

Lim, J., Ong, C. (2012). Online gambling growing on the quiet: The Straits Times. http://app.msf.gov.sg/pressRoom.aspx?tid=67&title=Gambling/Problem%20Gambling.

Loo, J. M. Y., Raylu, N., & Oei, T. P. S. (2008). Gambling among the Chinese: A comprehensive review. Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 1152–1166.

Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33, 335–343.

Lussier, I., Derevensky, J. L., Gupta, R., Bergevin, T., & Ellenbogen, S. (2007). Youth gambling behaviors: An examination of the role of resilience. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 21, 165–173.

Ministry of Community Youth and Sports (MCYS). (2008). Report of survey on participation in gambling activities among Singapore residents. Ministry of Community, Youth and Sport. www.mcys.gov.sg.

Ministry of Community, Youth and Sports (MCYS). (2011). Report of survey on participation in gambling activities among Singapore residents. Ministry of Community, Youth and Sport. www.mcys.gov.sg.

Myrseth, H., Pallesen, S., Molde, H., Johnsen, B. H., & Lorvik, I. M. (2009). Personality factors as predictors of pathological gambling. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(8), 933–937.

Oei, T. P. S., Lin, J., & Raylu, N. (2007a). Validation of the Chinese version of the Gambling Related Cognitions Scale (GRCS-C). Journal of Gambling Studies, 23, 309–322.

Oei, T. P. S., Lin, J., & Raylu, N. (2007b). Validation of the Chinese version of the Gambling Urges Scale (GUS-C). International Gambling Studies, 7, 101–111.

Oei, T. P. S., Lin, J., & Raylu, N. (2008). The relationship between gambling cognitions, psychological states, and gambling: A cross-cultural study of Chinese and Caucasians in Australia. Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology, 39, 147–161.

Oei, T. P. S., & Raylu, N. (2007). Gambling behaviours and motivations towards gambling among the Chinese. In T. P. Oei & N. Raylu (Eds.), Gambling and problem gambling among the Chinese (pp. 62–83). Brisbane: The University of Queensland.

Oei, T. P. S., Sawang, S., Goh, Y. W., Mukhtar, F. (2013) Using the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21) across culture. International Journal of Psychology, (in press).

Ozorio, B., & Fong, D. K. C. (2004). Chinese casino gambling behaviors: Risk taking in casinos vs. investments. UNLV Gaming Research and Review Journal, 8, 27–38.

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (1993). Review of the Satisfaction With Life Scale. Psychological Assessment, 5, 164–172.

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2008). The Satisfaction With Life Scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3, 137–152.

Potenza, M. N., Steinberg, M. A., Skudlarski, P., Fulbright, R. K., Lacadie, C. M., Wilber, M. K., et al. (2003). Gambling urges in pathological gambling: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, 828–836.

Raylu, N., & Oei, T. P. S. (2002). Pathological gambling: A comprehensive review. Clinical Psychology Review, 22, 1009–1061.

Raylu, N., & Oei, T. P. S. (2004a). Role of culture in gambling and problem gambling. Clinical Psychology Review, 23, 1087–1114.

Raylu, N., & Oei, T. P. S. (2004b). The Gambling Related Cognitions Scale (GRCS): Development, confirmatory factor validation and psychometric properties. Addiction, 99, 757–769.

Raylu, N., & Oei, T. P. S. (2004c). The gambling urge scale: Development, confirmatory factor validation, and psychometric properties. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 18, 100–105.

Robitschek, C., & Kashubeck, S. A. (1999). Structural model of parental alcoholism, family functioning, and psychological health: The mediating effects of hardiness and personal growth orientation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 46, 159–172.

Sacco, P., Cunningham-Williams, R. M., Ostmann, E., & Spitznagel, E. L. (2008). The association between gambling pathology and personality disorders. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 42, 1122–1130.

Sinniah, A., Maniam, T., Karuthan, C., Hatta, S., Jaafar, N., Oei, T. P. S. (2013). Psychometric properties and validation of the Satisfaction With Life Scale in psychiatric and medical outpatients in Malaysia. Comprehensive Psychiatry, (in press).

Slutske, W. S., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., & Poulton, R. (2005). Personality and problem gambling: A prospective study of a birth cohort of young adults. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 769–775.

Smith, G. J., Wynne, H. (2002). Measuring gambling and problem gambling in Alberta: Using the Canadian Problem Gambling Index (CPGI). Alberta Gaming Research Institute. www.uofaweb.ualberta.ca.

Springer, J. F., & Phillips, J. L. (1992). Extended national youth sports program 1991–1992 evaluation II: Individual protective factors index (IPFI) and risk assessment study. Folsom, CA: EMT Associates.

SPSS Inc. (1998). SPSS Base 8.0 for Windows User’s Guide. SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL.

Sylvain, C., Ladouceur, R., & Boisvert, J. M. (1997). Cognitive and behavioral treatment of pathological gambling: A controlled study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65, 727–732.

Teo, P., Mythily, S., Anantha, S., & Winslow, M. (2007). Demographic and clinical features of 150 pathological gamblers referred to a community addictions programme. Annals Academy of Medicine Singapore, 36, 165–168.

Victorian Casino and Gaming Authority. (2000). The impact of gaming on specific cultural groups report. Melbourne: Victoria.

Volberg, R. A. (1996). Prevalence studies of problem gambling in the United States. Journal of Gambling Studies, 12, 111–128.

Wagnild, G. M., & Collins, J. A. (2009). Assessing Resilience. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing, 47, 28–33.

Wagnild, G. M., & Young, H. M. (1993). Development and psychometric evaluation of the Resilience Scale. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 1, 165–178.

Welte, J. W., Barnes, G. M., Wieczorek, W. F., Tidwell, M. O., & Parker, J. C. (2004). Risk factors for pathological gambling. Addictive Behaviors, 29, 323–335.

Wiebe, J., Single, E., & Falkowski-Ham, A. (2001). Measuring gambling and problem gambling on Ontario. Ontario, Canada: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse and Responsible Gambling Council.

Zucker, R. A., Wong, M. M., Puttler, L. I., & Fitzgerald, H. E. (2003). Resilience and vulnerability among sons of alcoholics: Relationship to development outcomes between early childhood and adolescence. In S. S. Luthar (Ed.), Resilience and vulnerability: Adaptation in the context of childhood adversities (pp. 76–103). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Acknowledgments

This study started when Dr. Oei was a visiting professor at the National University of Singapore (NUS) and Mr. Goh was completing his thesis for the Master of Clinical Psychology degree. Dr. Oei now is an Emeritus Professor of UQ and a part-time visiting Professor at James Cook University, Singapore campus, and Mr Goh is now at the Institute of Mental Health, Singapore. We would like to thank Ms. WW Lai for her help. We would like to thank NUS and UQ for their support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Oei, T.P.S., Goh, Z. Interactions Between Risk and Protective Factors on Problem Gambling in Asia. J Gambl Stud 31, 557–572 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-013-9440-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-013-9440-3