Abstract

Economic and non-economic motives for gambling may amplify anxiety and depression among young adults. On the grounds that online gambling is highly addictive, it is imperative to assess significant contributory factors in gambling that aggravate financial harm and psychological distress. The study examines gamified problem gambling and psychological distress among young adults in Ghanaian universities. The study further explores the mediating role of cognitive biases and heuristics as well as financial motive for gambling between gamified problem gambling and psychological distress. Through a cross-sectional design and convenience sampling technique, the study employed (n = 678) respondents who took part in different forms of gambling events in the last 2 years. Instruments for construct assessment include problem gambling severity, cognitive biases and heuristics, financial motive for gambling and psychological distress scales. Control variables include gender, age, income source and type of gambling patronized in the last 2 years. Using hierarchical regression, gamified problem gambling was found to have a positive effect on psychological distress. Also, cognitive biases & heuristics partially mediates between gamified problem gambling and psychological distress. Finally, financial motive for gambling moderates between gamified problem gambling and psychological distress. The outcomes bring to bear economic and non-economic motives that exacerbate psychological distress among young adults. Based on the vulnerability of problem gamblers in developing countries, the researchers recommend a need for stricter regulations to somewhat control online gambling frequency among young adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Globally, mental health disorders have been established as the main cause of ill-health and disability (Anyanwu, 2023). As at 2019, the World Health Organization estimated that one out of every eight persons across the globe suffers some form of mental disorder at some point in time. This translates into approximately a billion people, with 14% being adolescents (WHO, 2023). The report adds that the two leading forms of mental health disorders are depression and anxiety, which are termed psychological distress. Psychological distress describe a person’s emotional state of helplessness, unhappiness, fear, discomfort and development of social seclusion tendencies (Ryu & Fan, 2023). Among young people, psychological distress is deemed as a major cause of a number of negative behavioral outcomes such as suicidal thoughts and attempts, below average academic performance and deteriorating physical health (EC, 2018; Ratanasiripong et al., 2022; Waters & Ashton, 2022). Henceforth, there has been growing scholarly interest among researchers and practitioners on psychological distress among young people (Burt, 2022; Tataw & Kim, 2022). In this vein, this study argues that components of antisocial behavior among young people are major antecedents of psychological distress. The researchers infer this assertion from contemporary issues such as global emergencies like COVID-19, where social distancing significantly contributed to aggression and violence among young people (O’Connell et al., 2021).

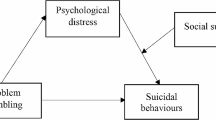

The current study extends literature on antisocial behavior by exploring the concept from gambling perspective and its related economic and psychological motives among young people. Empirical literature on problem gambling has been sparingly conducted, nonetheless, scholarly evidence suggests that problem gambling is an integral part of the ‘generality of deviance’, a concept that is central to antisocial behavior (AGRI, 2019; Mishra et al., 2017). On the bases of preceding discussions and rarity of empirical evidence, the study assesses the effect of gamified problem gambling (GPG) on psychological distress among young people. Further, an assessment of the mediating effect of cognitive biases and heuristics between GPG and psychological distress was conducted. Lastly, the study explores moderating effect of financial motive for gambling between GPG and psychological distress. The study employed both cognitive theory of gambling (CTG) and relative deprivation theory (RDT) to explain relationships among the study variables.

Motivation for this paper stems from a number of pressing global health and well-being issues. First, mental health challenge is a major setback for the promotion of human well-being across the globe, hence there is a need to understand varying factors that trigger these negative health conditions. Second, in an era of rapidly increasing technological evolution, there is a need to understand its potential negative consequences on economic and psychological outcomes among young adults.

Literature Review

Theory Grounding the Study and Hypothesis Development

Gamified Problem Gambling and Psychological Distress

Problem gambling (PG) describes addictive tendencies of persons to take part in gambling events to their own detriment or to the detriment of others (Quilty et al., 2019). PG is associated with lack of control in use of resources for gambling with less or no regard for financial, personal and social burdens (APA, 2013). This lack of control has further been exacerbated by the adoption of digital technologies such as gamified applications in gambling. Gamified apps are user convenient digital platforms that deploy simple computational design processes to execute tasks (Hulsey, 2019). Thus, gamified apps have in-built game mechanics that deliver design affordances to optimize loyalty and trigger end-user enthusiasm (Martín-Peña et al., 2023). This may consequently lead to high gambling frequency due to ease and convenience.

High frequency gambling has the propensity to create financial harm, which includes depletion of savings, debt payment challenges and bankruptcy (Newall & Talberg, 2023). Also, the condition of ‘house edge’ propels gambling firms to design events in a manner that is attractive and addictive to gamblers (Swanton & Gainsbury, 2020). Within this context, mounting losses may irrationally and erroneously provoke gamblers’ cognition to continuous gambling in quest to ‘get even’ (Edson et al., 2022). This assertion is grounded in the cognitive theory of gambling (CTG), which posits that irrational cognitive biases such as illusion of control make gamblers believe they can influence random outcomes (Rao & Hastie, 2023). The CTG add that gamblers’ fallacy irrationally makes them believe that after a nearly missed event comes a win. Based on cognitive distortions and corresponding financial harm posed by problem gambling, some prior studies contend that problem gambling leads to psychological distress (Oksanen et al., 2018; Mills et al., 2021). In a recent study undertaken by Buen and Flack (2022) they opined that through some erroneous cognition, gamblers believe that the more they gamble the better their understanding, competency and predictive abilities. However, this continuous patronage of gambling events may culminate into emotional challenges of psychological distress.

Empirical studies have established a positive link between online problem gambling and psychological distress (André et al., 2022; Håkansson & Widinghoff, 2020). Based on the preceding arguments advanced, the study hypothesized that:

H2: Gamified problem gambling is positively linked to psychological distress.

Mediating Effect of Cognitive Biases and Heuristics (CBHs)

The study assesses mediating effect of cognitive biases and heuristics between gamified problem gambling and psychological distress. Conception of the mediation role is premised on the grounds that CBHs are mechanisms that ignite gambling action (Ford & Shook, 2019; Gu et al., 2015), and have propensity to affect psychological distress of gamblers (Acciarini et al., 2021; Leung et al., 2022). Further, heuristics describe a state of mind where mental shortcuts that seem to deliver quicker decisions are deployed when entities or persons are faced with uncertainties (Parveen et al., 2020). Cognitive biases and heuristics are phenomena that are gaining considerable attention among investment decision-making researchers in contemporary times. For example, Mittal (2022) conducted a review and concluded that behavioral biases in decision-making processes are integral parts of human life in a contemporary multifaceted world. Thus, a person’s decision-making processes are highly reliant on intuitiveness, which is dependent on heuristics.

Additionally, heuristics inspires overconfidence in decision-making (Goyal et al., 2023). Nevertheless, the authors acknowledge that though it seems a simple process, it can lead to systematic errors in some situations. Cognitive biases and heuristics are relevant in explaining gambling behaviors, however, very little is known about gamblers’ prejudiced dispositions and overconfidence in extant literature. To address this gap, the current study draws theoretical strength from the cognitive theory of gambling (CTG) to explore the mediating role of cognitive biases and heuristics between gamified problem gambling and psychological distress. The theory argues that though gambling events are independent of each other, some gamblers connote spurious signs as strong tactical grounds to engage in gambling (Tabri et al., 2023). These spurious signs are commonly termed ‘cognitive distortions’, and may manifest in varying ways. For instance, some gamblers become overconfident in their actions, choices and personal attributes, perceiving them as determinants of likelihood of event outcomes. The mediating effect of CBHs have been established in a number of empirical studies (Jain et al., 2022) and (Wang et al., 2021). Based on these discussions, the study hypothesized that:

H2. Cognitive biases and heuristics mediate between GPG and Psychological Distress.

Moderating role Of Financial Motive for Gambling (FMG)

Financial motive for gambling is an important economic arrangement (Watanapongvanich et al., 2022), but has been far less explored in current studies as conditioning factor, particularly in relation to psychological distress. Although, several reasons may account for the involvement of young people in different forms of gambling, nonetheless, financial motive has been commonly touted as a major motivation for gambling (Emond et al., 2022; Price, 2022). Solely participating in gambling activities for economic reasons may promote severe gambling behavior, a psychological state that could consequently result in gambling related disorders (MacLaren et al., 2015; Mulkeen et al., 2017).

Extant literature has established financial motive as a major determinant of high frequency of gambling and problem gambling (Tabri et al., 2022; Leslie & McGrath, 2023). Within context, the study employed the relative deprivation theory (RDT) propounded by Stouffer (1949). The RDT refers to the opinion that a person or group is disadvantaged when matched to a set reference group, which correspondingly leads to emotional responses such as annoyance, bitterness and a state of feeling powerlessness (Smith & Pettigrew, 2015). The study argues that FMG serves as a persuasive force for gamblers to attain financial success in the midst of economic hardship and limited opportunities for economic empowerment (Welte et al., 2017). Thus, the moderating effect of FMG was explored between gamified problem gambling and psychological distress in the current study. This relationship draws strength from a number of empirical studies that established the moderating effect of FMG (Tabri et al., 2015, 2022). Based on this premise, the study hypothesized that:

H3: Financial motive of gambling moderates between GPG and psychological distress.

Methodology

Participants and Procedure

An anonymous survey was conducted among young adults in a number of universities in the Greater Accra Region of Ghana. The study setting was selected for a number of reasons. First, problem gambling among young adults in universities has become a major cause of concern for authorities (Çelik et al., 2022; Torrado et al., 2020), hence there is a need for academics to investigate this growing phenomenon. Second, digitalization has increased gambling behavior among young adults in universities (Biegun et al., 2022), hence the need to explore the role of gamified app use. Accordingly, the study population was targeted at university students in Ghana, and the survey was conducted between the months of September 2022 and January 2023. This study was conducted at 4 main locations, namely; Tema, Madina, Tesano and Legon in the Greater Accra Region of Ghana. A number of gambling centres located within these suburbs were sampled. They include casinos and betting centres. The research team engaged respondents who admitted that they were university students and have been involved in some form gambling in the last two years.

A convenience sampling technique was employed to administer a total of 950 questionnaires, however, only 678 valid responses were retrieved, which constitute 71.4% response rate. SPSS version 23 was employed for the statistical analyses. Pre-testing of the questionnaire was undertaken through distribution of sample questions to 38 lecturers with area of expertise relating to psychology as recommended by Preneger et al. (2014). The pre-test outcomes were deemed adequate, thus, the researchers concluded that all items on the questionnaire were well understood. Finally, likely challenges of common method variance (CMV) were addressed through the Harman single factor test (Podsakoff et al., 2003). It was unearthed that no single factor ‘variance explained’ was less than the adequacy benchmark of 50%, consequently the study established that there was no CMV challenges with the dataset.

Measures and Instruments

The research employed empirically established measurement scales relating to the study constructs. But due to contextual differences, a number of minor modifications were made to the research instruments. A five-point Likert-type scale with anchors (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree was used to gather responses on all the constructs. The descriptions of the scales are given below.

Gamified problem gambling. For this construct, a nine-item scale by IJsselsteijn et al. (2013) and five-item scale (Addiction Severity Index-Gambling) by Petry (2003) were employed. Within context, gamified problem gambling refers to severity of gambling due to enhanced online platforms, which deliver gambling convenience. A sample item on the scale is; “I felt completely absorbed using gamified apps for gambling”. The scale recorded a Cronbach’s alpha (α > 0.70) value of 0.872.

Cognitive biases and heuristics. For this construct, three items from ‘Interpretive Bias’ sub-scale was adapted from Raylu and Oei (2004). The study describes cognitive biases as self-assuring tenets of a gambler arising from over-confidence, misjudgment and illusion. A sample item on the scale is; “I am sure about my chances of winning anytime I gamble”. Reliability of the construct’s score was 0.883.

Financial motive for gambling. For this construct, a nine-item scale adapted from Mathieu et al. (2020) was used. The study contextualized financial motives for gambling as monetary rewards likely to accrue from a gambling event. A sample item on the scale is; “Winning will change my lifestyle”. Reliability of the construct score was 0.899.

Psychological distress. The construct was measured with a five-item scale adapted from Mental Health Inventory (MHI-5) by Berwick et al. (1991) was used. The study describes psychological distress as mental disorders such as depressive tendencies and anxiety arising from gambling behaviors. A sample item on the scale is; “I feel nervous when I gamble”. Reliability score was 0.917.

3.2.1 Control variables. Age, gender, family history of gambling and type of gambling were controlled for in the study. The control variables were selected based on demographic and contextual factors. Accordingly, the controlled variables made a significant impact on psychological distress.

Results

Psychometric Properties of Measures

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted with eigenvalue fixed above 1 for each scaled item. EFA outcomes unearthed that all items of GPG, CBHs, FMG and psychological distress met the benchmarked value of 0.07 (Hair et al., 2017). Consequently, cognitive biases and heuristics, as well as psychological distress had all items loading significantly. On the other hand, GPG had 8 out of 14 items loading adequately, while FMG had 6 out of 9 items loading adequately. Further, robustness of the data (goodness-of-fit) was examined through an alternate technique to guarantee data credibility (Hair et al., 2010).

Sampling Adequacy Tests

KMO and Bartlett’s test of sphericity are primary valuation methods that are used to ascertain sampling satisfactoriness when undertaking EFA. KMO values are expected to fall between 0 and 1 to be deemed as adequate. Also, adequacy benchmark of Bartlett’s test is any value less than 0.05. KMO scores revealed in this study are as follows; GPG, cognitive biases and heuristics and financial motive for gambling (all explanatory variables were grouped) = 0.861; and explained 69.093% of variance in the model. Further, psychological distress = 0.834 and explained 56.912% of variance in the model. The p-values of Bartlett’s test of sphericity (p-value sig of 0.000 < 0.05) were significant for all variables. In summary, the dataset was deemed as adequate and suitable for further analyses.

Reliability, Validity and Correlation Analysis

The study assessed internal consistency of the research instruments through Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability. Nunnally and Bernstein (1994) assert that Cronbach’s alpha values must be > 0.70, whereas Composite reliability must be > 0.80. Each construct loaded significantly; GPG = (α 0.872, CR 0.968); CBHs = (α 0.883, CR 0.919); FMG (α 0.899, CR 0.949) and psychological distress (α 0.917, CR 0.956). These show that each construct recorded good reliability and composite reliability (see Table 1).

In establishing convergent validity, all average variance extracted (AVE) values were expected to be greater than 0.5. Similarly, the square root of all constructs’ AVE must be greater than the correlations between the constructs in the model to establish discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). The figures obtained show that convergent and discriminant validities have been established (see Table 1).

Measurement and Structural Model

The statistics measurement model recorded is illustrated as follows (\(x2 = 488.326, df = 392, p = 0.001\)), the other indices include; (CFI = 0.994, NFI = 0.998, TLI = 0.992, GFI = 0.993, RMSEA = 0.003), indicating good fit of the model.

Demographic Characteristics and Test of Normality

The survey is made up of 4 demographic characteristics, namely; gender, age, main gambling form and family history. Gender was dominated by males with 76.8%. Age range 18–27 recorded the highest frequency, accounting for 60.3%. Respondents’ family history of gambling was predominantly “Yes” with 69.0%. Finally, 83.8% of respondents ticked sports betting as their main form of gambling. Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk’s test of normality was deployed to test normality of the dataset. The p-values for all constructs were above the threshold α-value of 0.05 (Pallant, 2007); for this reason, the dataset was deemed as normally distributed.

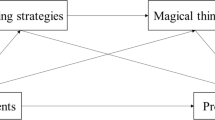

Cognitive Biases and Heuristics (CBHs) as A Mediator (The Bootstrapping Approach)

The study deployed Model 5 of mediation techniques established by Hayes and Preacher (2013) to assess the mediating effect of CBHs. A bootstrapping technique with advanced features of process macro with ‘bias-corrected’ confidence estimations was used to investigate the mediation effect. The assessment of indirect effect of cognitive biases and heuristics between gamified problem gambling and psychological distress was executed via the estimation of lower-limit and upper-limit confidence intervals, which have no zero value. Finally, 5,000 bootstrap re-samples set to 95% confidence interval was used in the inferential analysis.

The “total effects” reveal that GPG positively influences psychological distress (“c” path: B = 0.119, SE = 0.040, z = 2.96, p < 0.001). GPG has a positive effect on CBHs (“a” path: B = 0.681, SE = 0.035, z = 19.47, p < 0.001); whereas a positive effect of CBHs was established on psychological distress (“b” path: B = 0.113, SE = 0.035, z = 3.22, p < 0.001). The indirect effect between GPG, FMG and psychological distress of (0.077) was significantly positive. The indirect effect between GPG and psychological distress via cognitive biases and heuristics (CBHs) ranged from LL 0.030 – UL 0.125 and did not contain zero, hence CBHs was significant as a mediator, rendering support to objective 1 and 2. In addition, the mediating effect of CBHs was established as partial. Finally, the result of the indirect effect (0.077) divided by total effect (0.196) is 0.394; this predicts that about 39.4% of the effect of GPG and psychological distress is mediated by cognitive biases and heuristics (CBHs). Similarly, the result of the indirect effect (0.077) divided by the direct effect (0.119) is 0.651; connoting that the mediated effect is about 0.7 times as large as the direct effect of GPG and psychological distress.

Effect of Financial Motive for Gambling (FMG) as A Moderating Variable

Moderation effect of financial motive for gambling (FMG) was tested through hierarchical regression analysis. Hierarchical regression analysis is applicable when product of an interaction effect of variables, for example, X and M have a significant effect on an outcome variable termed Y. Precisely, the analysis was undertaken to examine linear, as well as, interaction effects of gamified problem gambling (GPG) and FMG. The study variables were sequentially entered into the statistical model as follows: the first variable entered was GPG. GPG and FMG were loaded in the second entry. The third entry includes; GPG, FMG and the interaction term (GPG*FMG).

Based on the 3 explanatory variables loaded in the model to explain students’ psychological distress, the following R2 changes were revealed. GPG explained 3.6% of total variations in psychological distress; addition of FMG caused a positive change of 34.2% (37.8%). The third model includes GPG, FMG and GPG*FMG, and had a positive change of 6.3% (44.1%) on respondents’ psychological distress. Additionally, the hierarchical regression analysis was tested through a Durbin Watson assessment to exclude any latent autocorrelation present in the dataset. The Durbin Watson value obtained was 1.697, which is less than benchmark score of 2.0; thus, the dataset is deemed to be free from autocorrelation challenges. Lastly, out of the 3 statistical models tested for overall goodness of fit, the third model proved to have a relatively higher indices, henceforward, the third model was chosen for further analysis.

Regarding beta values in the regression model, the 3 variables loaded, namely; GPG, FMG and GPG*FMG have significant and positive effect on respondents’ psychological distress (β = 0.064); (β = 0.525); and (β = 0.266) respectively. Likely multicollinearity risks were addressed via the variance inflation factor (VIF) test. Hair et al. (2010) recommend a VIF benchmark value of less than 4.0 as passable for further analysis. The test result shows that VIF values recorded for all explanatory variables were less than 4, consequently there was no multicollinearity challenges with the dataset.

Figure 1 demonstrates how conditional moderating effect of FMG affects relation between GPG and psychological distress. Conditional indirect effect of FMG between GPG and participants’ psychological distress was assessed in the study. The study was modelled on Preacher et al.’s (2007) recommendation of setting low and high limits for moderators. Further, the recommendation is explained by standard deviations above and below the mean scores. The study outcomes shows that the positive indirect effect of financial motive for gambling between GPG and respondents’ psychological distress is stronger when it is high than low (β = 0.116, p < 0.05), LLCI – ULCI (0.043–0.178), and does not contain zero (see Tables 2 and 3; Fig. 1).

Discussion of Findings

Frequency in gambling may be exacerbated by use of gamified apps, as they create ease of use platforms that increase frequency to gamble. Although gambling is thought-out to be inspired by personal motives such as fun, travel experience and coping, it may also result in adverse effects such as anxiety, stress and depression. This study develops a comprehensive conceptual model to examine relationships between gamified gambling experience, cognitive biases and heuristics, financial motives for gambling and psychological distress among young gamblers in Ghanaian universities. The study explores significant body of literature on theories that explain linkages between technologies aided gambling experience, overconfidence gambling skills, economic deprivation and psychological distress of young gamblers. Thus, the study builds an empirical model that links GPG to psychological distress. Additionally, the study explores the mediating role of CBHs, as well as, moderating role of FMG.

Relationship Between Gamified Problem Gambling and Psychological Distress

As projected in the conceptual mappings, the results provide support for all hypothesized paths. The first hypothesis was supported as the study outcome confirms a positive association between GPG and psychological distress. It could be said that increase in frequency and uncontrolled gambling may be worsened by digital technologies such as gamified apps (Rosenbaum et al., 2022). Further, GPG is largely underpinned by cognitive distortions and gambler’s ‘near miss comes a win’ fallacy, a situation that may pose dire financial consequences and subsequently leads to psychological distress (Mills et al., 2021; Rao & Hastie, 2023). The current study corroborates research undertaken by André et al. (2022)d kansson and Widinghoff (2020), where the authors separately established that GPG is a major influencer of psychological distress.

Mediating Effect of Cognitive Biases and Heuristics (CBHs)

A partially significant mediating effect of CBHs between GPG and psychological distress was established in the study. In providing an understanding of the study outcomes, it could be inferred that cognitive distortions such as belief in one’s gambling prowess, as well as overconfidence in false claims of competency in gambling are major determinants of problem gambling. Further, each gambling event is independent of the other, however, many gamblers falsely draw computations and trend analysis to deploy predictive outcomes. These cognitive distortions motivate increase in gambling frequency leading to problem gambling. Problem gambling is positively associated with anxiety and depression. Thus, the mediating effect of cognitive biases & heuristics is well-established in the current study. This finding resonates with those undertaken by Jain et al. (2022) and Wang et al. (2021), where the studies established the mediating role of cognitive biases & heuristics within the context of gambling literature. For pictoral representation of the mediation effect, refer to Fig. 2.

Moderating Effect of Financial Motive for Gambling (FMG)

The findings demonstrate that FMG moderates between gamified problem gambling and psychological distress. The quest to satisfy socio-economic needs provide a good starting point for understanding young people’s drive to engage in gambling. This assertion is further strengthened by digital innovation, which has brought variety of gambling activities much closer to young people. In the mind of the gambler, gambling is a form of investment that has the propensity to generate economic utility, hence making financial commitments is deemed a worthwhile exercise. Accordingly, it could be inferred that FMG forms the base for young adults to engage in several forms of gambling (Lee et al., 2022). The study argues that if use of gamified problem gambling is high (input = output), then financial motive for gambling will increase. Consequently, this will lead to debt accumulation, heightened anxiety, stress and depression among gamblers (Oksanen et al., 2018). The study’s finding resonates with studies undertaken by Tabri et al. (2015) and Tabri et al. (2022). For graphical representation of the moderation effect, refer to Fig. 1.

Conclusion and Implications of the Study

Owing to the significant effect of GPG on psychological distress, researchers continue to investigate links between different forms of problem gambling and their associated mental and emotional risks on young adults. Further, adoption of digital platforms has been established as an enabler of positive, easy and convenient input for work designs in contemporary times. Accordingly, empirical studies on digital transformation have been predominantly targeted at exploring positive impact of technology on people’s lives. Nevertheless, there are dark sides of technology that need scholarly attention. To it, the current study explores links between GPG, cognitive biases & heuristics, financial motive for gambling and psychological distress among young adults, which has jointly received little research attention within the domain of gambling literature. By deploying hierarchical regression analysis, the findings indicate that GPG has a positive effect on psychological distress. Also, a partial mediating effect of cognitive biases & heuristics was established between GPG and psychological distress. Lastly, the findings reveal that financial motive for gambling moderates between GPG and psychological distress.

The study makes several theoretical contributions to gambling and human behavior research. The study delivers an original perspective by combining cognitive theory of gambling and relative deprivation theory to explain links between online problem gambling and psychological distress among young adults in Ghana. More specifically, the study extends knowledge on existing literature by providing causal effects of cognitive distortions in decision-making processes with regard to gambling. Also, the relative deprivation theory has been extended as a motivational affordance (economic benefit) for young people, as they are deemed to be confronted with less socio-economic opportunities. In terms of practical contributions, the study results pose implications for governments, regulators and advertisers of gambling events in Ghana. First, these outcomes add to a growing body of evidence demonstrating that digital platforms such as gamified apps are a major determinant of problem gambling. This is evident in the mean score recorded in the study for gamified problem gambling. Ease of use and convenience in use have led to a greater participation of gamblers in gambling events. Thus, these findings will further strengthen discussions on means by which negative consequences of technology on gambling could be lessened. Second, deprivation and economic challenges have been identified as a major motive for gambling in this study. Hence there is a need for regulators to institutionalize harm minimization techniques, an approach that stipulates upper limits for taking part in gambling events. Thus, this study reiterates the call by some scholars for gambling firms and regulators to formulate and implement harm minimization interventions in order to reduce financial and psychological harm (Drummond et al., 2019, 2020). Third, cognitive distortions and overconfidence are major addictive behaviors that lead to problem gambling and consequently anxiety and depression (Coelho et al., 2022; Kim et al., 2020). Although gambling is legal and has a number of socio-economic benefits, policy makers should draw equilibrium between its benefits and psychological challenges posed to individual gamblers. This can help build control mechanisms to regulate gambling activities among the youth in Ghana.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

There are a number of pragmatic implications posed by this study, nevertheless, some limitations are noteworthy to guide future studies on the phenomenon. First, the study assessed online problem gambling and psychological distress from a cross-sectional design viewpoint. Although, this research design has numerous merits in measuring perceptions and behaviors of gamblers within context, it fails to take into cognizance changing dynamics of respondents’ overtime. The current study suggests future studies to explore the phenomenon using a longitudinal survey design. Second, the study was conducted from a positivism philosophical paradigm though its advantages span from outcome generalization to data objectivity, it is limited in providing in-depth understanding of the cause and effect relationships. The study recommends future research to be explored from an interpretivist’s outlook.

Data availability

The study’s primary data will be made available upon reasonable request.

References

Acciarini, C., Brunetta, F., & Boccardelli, P. (2021). Cognitive biases and decision-making strategies in times of change: A systematic literature review. Management Decision, 59(3), 638–652. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-07-2019-1006.

André, F., Håkansson, A., & Claesdotter-Knutsson, E. (2022). Gaming, substance use and distress within a cohort of online gamblers. Journal of Public Health Research, 11(2434), 1–7.

Anyanwu, M. (2023). Psychological distress in adolescents: Prevalence and its relation to high-risk behaviors among secondary school students in Mbarara Municipality, Uganda. BMC Psychology, 11(5), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01039-z.

Berwick, D., Murphy, J. M., Goldman, P. A., Ware, J. E., Barsky, A. J., & Weinstein, M. C. (1991). Performance of a five-item Mental Health Screening Test. Medical Care, 29(2), 169–176.

Biegun, J., Edgerton, J., & Roberts, L. (2022). Measuring Problem Online Video Gaming and its Association with Problem Gambling and suspected motivational, Mental Health, and behavioral risk factors in a sample of University students. Games and Culture, 16(4), https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412019897524.

Buen, A., & Flack, M. (2022). Predicting problem gambling severity: Interplay between emotion dysregulation and gambling-related cognitions. Journal of Gambling Studies, 38(2), 483–498.

Burt, S. (2022). The genetic, environmental, and Cultural Forces Influencing Youth Antisocial Behavior are tightly intertwined. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 18, 155–178. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-072220-015507.

Çelik, S., Öztürk, A., Kes, E., & Kurt, A. (2022). The relationship of gambling with sensation-seeking behavior and psychological resilience in university students. Perspectives of Psychiatric Care, 58(4), 2199–2207. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.13047.

Coelho, S. G., Tabri, N., Kerman, N., Lefebvre, T., Longpre, S., Williams, R. J., & Kim, H. S. (2022). The Perceived Causes of problems with Substance Use, Gambling, and other behavioural addictions from the perspective of people with lived experience: A mixed-methods investigation. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-022-00900-3.

Drummond, A., Sauer, J., & Hall, L. (2019). Loot box limit-setting: A potential policy to protect video game users with gambling problems? Addiction, 114(5), 935–936. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14583.

Drummond, A., Sauer, J., Ferguson, C., & Hall, L. (2020). The relationship between problem gambling, excessive gaming, psychological distress and spending on loot boxes in Aotearoa New Zealand, Australia, and the United States-A cross-national survey. Plos One, 15(3), https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230378.

Edson, T., Nairn, A., Collard, S., & Hollén, L. (2022). Returning to the virtual casino: A contemporary study of actual online casino gambling. International Gambling Studies, 22(1), 114–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2017.1333131.

Emond, A., Nairn, A., Collard, S., & Hollén, L. (2022). Gambling by young adults in the UK during COVID19 lockdown. Journal of Gambling Studies, 38(1), 1–13.

Ford, C., & Shook, N. (2019). Negative cognitive Bias and Perceived stress: Independent mediators of the relation between mindfulness and emotional distress. Mindfulness, 10, 100–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0955-7.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Goyal, P., Gupta, P., & Yadav, V. (2023). Antecedents to heuristics: Decoding the role of herding and prospect theory for indian millennial investors. Review of Behavioral Finance, 15(1), 79–102. https://doi.org/10.1108/RBF-04-2021-0073.

Gu, J., Strauss, C., Bond, R., & Cavanagh, K. (2015). How do mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction improve mental health and wellbeing? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 37, 1–12.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Hair, J. F. J., Babin, B. J., & Krey, N. (2017). Covariance-based structural equation modeling in the journal of advertising: Review and recommendations. Journal of Advertising, 46(1), 163–177.

Håkansson, A., & Widinghoff, C. (2020). Gender differences in Problem Gamblers in an online gambling setting. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 13, 681–691. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S248540.

Hayes, A. F., & Preacher, K. J. (2013). Conditional process modeling: Using structural equation modeling to examine contingent causal processes. In G. R. Hancock, & R. O. Mueller (Eds.), Structural equation modeling: A second course (pp. 219–266). AP Information Age Publishing.

Hulsey, N. (2019). Game Studies and Gamification. Games in Everyday Life: For play (pp. 17–34). Bingley. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-83867-937-820191002.

IJsselsteijn, W. A., de Kort, Y. A. W., & Poels, K. (2013). The game experience questionnaire. Technische Universiteit: Eindhoven.

Jain, R., Sharma, D., Behl, A., & Tiwari, A. (2022). Investor personality as a predictor of investment intention – mediating role of overconfidence bias and financial literacy. International Journal of Emerging Markets. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-12-2021-1885.

Kim, H., Hodgins, D., Kim, B., & Wild, T. (2020). Trans-diagnostic or disorder specific? Indicators of substance and behavioral addictions nominated by people with lived experience. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(2), https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9020334.

Lee, S., Shin, Y., & Na, J. (2022). Differences in gambling behaviors and mental health depending on types of gambling motives among young adults in Korea. International Gambling Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2022.2130957.

Leslie, R. D., & McGrath, D. S. (2023). A comparative Profile of Online, Offline, and Mixed-Mode problematic gamblers’ gambling involvement, motives, and HEXACO personality traits. Journal of Gambling Studies, 1–17.

Leung, C., Yiend, J., Trotta, A., & Lee, T. (2022). The combined cognitive bias hypothesis in anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2022.102575. 89.

MacLaren, V., Ellery, M., & Knoll, T. (2015). Personality, gambling motives and cognitive distortions in electronic gambling machine players. Personality and Individual Differences, 73, 24–28.

Martín-Peña, M. L., García-Magro, C., & Sánchez-López, J. M. (2023). Service design through the emotional mechanics of gamification and value co-creation: A user experience analysis. Behaviour & Information Technology. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2023.2177823.

Mathieu, S., Barrault, S., Brunault, P., & Varesco, I. (2020). The role of gambling type on gambling motives, cognitive distortions, and gambling severity in gamblers recruited online. Plos One, 15(10), https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238978.

Mills, D. J., Li Anthony, W., & Nower, L. (2021). General motivations, basic psychological needs, and problem gambling: Applying the framework of self-determination theory. Addiction research & theory, 29(2), 175–182.

Mishra, S., Lalumière, M., & Williams, R. (2017). Gambling, Risk-Taking, and antisocial behavior: A replication study supporting the generality of deviance. Journal of Gambling Studies, 33(1), 15–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-016-9608-8.

Mittal, S. K. (2022). Behavior biases and investment decision: Theoretical and research framework. Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, 14(2), 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRFM-09-2017-0085.

Mulkeen, J., Abdou, H., & Parke, J. (2017). A three stage analysis of motivational and behavioural factors in UK internet gambling. Personality and Individual Differences, 107, 114–125.

Newall, P. W. S., & Talberg, N. (2023). Elite professional online poker players: Factors underlying success in a gambling game usually associated with financial loss and harm. Addiction Research & Theory. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2023.2179997.

Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

O’Connell, K., Berluti, K., Rhoads, S., & Marsh, A. (2021). Reduced social distancing early in the COVID-19 pandemic is associated with antisocial behaviors in an online United States sample. PLOS ONE, 16(1), https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244974.

Oksanen, A., Savolainen, I., Sirola, A., & Kaakinen, M. (2018). Problem gambling and psychological distress: A cross-national perspective on the mediating effect of consumer debt and debt problems among emerging adults. Harm Reduction Journal, 15(1), 1–11.

Pallant, J. (2007). SPSS survival manual—A step by step guide to data analysis using SPSS for windows ( (3rd ed.). Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Parveen, S., Satti, Z., Subhan, Q., & Jamil, S. (2020). Exploring market overreaction, investors’ sentiments and investment decisions in an emerging stock market. Borsa Istanbul Review, 20(3), 224–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bir.2020.02.002.

Petry, N. (2003). Validity of a gambling scale for the addiction severity index. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 191(6), 399–407. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NMD.0000071589.20829.DB.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42(1), 185–227.

Preneger, T., Courvoisier, D., Hudelson, P., & Gayet-Ageron, A. (2014). Sample size for pre-tests of questionnaires. Quality of Life Research, 24(1), 147–151.

Price, A. (2022). Online gambling in the midst of COVID-19: A Nexus of Mental Health concerns, substance use and financial stress. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20, 362–379.

Quilty, L. C., Wardell, J. D., Thiruchselvam, T., Keough, M. T., & Hendershot, C. S. (2019). Brief interventions for problem gambling: A meta-analysis. Plos One, 14(4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214502.

Ratanasiripong, P., Wang, C. D., Ratanasiripong, N., Hanklang, S., Kathalae, D., & Chumchai, P. (2022). Impact of psychosocial factors on academic performance of nursing students in Thailand. Journal of Health Research, 36(4), 598–606. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHR-07-2020-0242.

Raylu, N., & Oei, T. (2004). The Gambling related Cognitions Scale (GRCS): Development, confirmatory factor validation and Psychometric Properties. Addiction, 99, 757–769. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00753.x.

Rosenbaum, M., Walters, G., Edwards, K., & Gonzalez-Arcos, C. (2022). Commentary: The unintended consequences of digital service technologies. Journal of Services Marketing, 36(2), 97–109. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-03-2021-0072.

Ryu, S., & Fan, L. (2023). The relationship between financial worries and psychological distress among U.S. adults. Journal Family Economic Issues, 44(1), 16–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-022-09820-9.

Smith, H., & Pettigrew, T. (2015). Advances in relative deprivation theory and research. Social Justice Research, 28(1), 1–6.

Stouffer, S. (1949). The american soldier. Princeton. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Swanton, T., & Gainsbury, S. (2020). Gambling-related consumer credit use and debt problems: A brief review. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 31, 21–31.

Tabri, N., Dupuis, D. R., Kim, H. S., & Wohl, M. J. (2015). Economic mobility moderates the effect of relative deprivation on financial gambling motives and disordered gambling. International Gambling Studies, 15(2), 309–323.

Tabri, N., Xuereb, S., Cringle, N., & Clark, L. (2022). Associations between financial gambling motives, gambling frequency and level of problem gambling: A meta-analytic review. Society for the study of addiction, 117(3), 559–569.

Tabri, N., Salmon, M. M., & Wohl, M. J. A. (2023). Advancing the Pathways Model: Financially focused self-concept and erroneous beliefs as Core Psychopathologies in Disordered Gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 39, 13–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-022-10105-x.

Tataw, D., & Kim, S. (2022). Antisocial behavior and attitudes towards antisocial behavior after a five-year Municipal Youth and Family Master Plan in Pomona, California, USA. Social Work in Public Health, 37(7), 655–678. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2022.2072037.

Torrado, M., Bacelar-Nicolau, L., Skryabin, V., Teixeira, M., Eusébio, S., & Ouakinin, S. (2020). Emotional dysregulation features and problem gambling in university students: A pilot study. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 38(4), 550–566. https://doi.org/10.1080/10550887.2020.1800889.

Wang, M., Xu, Q., & He, N. (2021). Perceived interparental conflict and problematic social media use among chinese adolescents: The mediating roles of self-esteem and maladaptive cognition toward social network sites. Addictive Behaviors, 112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106601.

Watanapongvanich, S., Khan, M., Putthinun, P. O. S., & Kadoya, Y. (2022). Financial literacy and Gambling Behavior in the United States. Journal of Gambling Studies, 38, 445–463. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-021-10030-5.

Waters, S., & Ashton, J. (2022). Guest editorial. Journal of Public Mental Health, 21(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMH-03-2022-155.

Welte, J. W., Barnes, G. M., Tidwell, M. C. O., & Wieczorek, W. F. (2017). Predictors of problem gambling in the U.S. Journal of Gambling Studies, 33(2), 327–342.

APA (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5™ (5th ed.). Retrieved from: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.

EC (2018). Seventh Framework Programme: Emerging mental health systems in low- and middle-income countries. Retrieved from: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/305968/reporting [Accessed 7 March 2023].

AGRI (2019). Alberta Gambling Research Institute – Written evidence (GAM0017) Retrieved from: https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/104767/html/.

WHO (2023). World Health Organization. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/news/item/17-06-2022-who-highlights-urgent-need-to-transform-mental-health-and-mental-health-care [Accessed 7 March 2023].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Agbenorxevi, C.D., Hevi, S.S., Malcalm, E. et al. Gamified Problem Gambling and Psychological Distress: The Mediated-Moderated Roles of Cognitive and Economic Motives. J Gambl Stud 39, 1355–1370 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-023-10219-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-023-10219-w