Abstract

This study examined the impact of temporal changes in intimate partner violence (IPV) on individuals’ romantic relationship. Analyses based on a sample of 8279 young adults from Waves III and IV of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) revealed that greater temporal increases in victimization were related to lower satisfaction. The association between increases in perpetration and satisfaction was not significant. Additionally, for women, greater increases in IPV perpetration were related to higher satisfaction. For men, the association between increases in perpetration and satisfaction was not significant. For both men and women, greater increases in victimization were related to lower satisfaction. Thus, temporal changes in IPV might have differing impacts on relationship satisfaction for men versus women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV), often defined as physical, sexual, or psychological harm by a current or former partner or spouse (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2013), is prevalent in the United States (O’Leary et al. 1989). Even young couples experience IPV. It is estimated that 16 % to 36 % of newlywed husbands and 24 % to 44 % of newlywed wives have perpetrated physical aggression against their partners (Panuzio and DiLillo 2010). Studies have shown that IPV is related to a variety of negative outcomes, including increased levels of stress (Testa and Leonard 2001), as well as symptoms of depression (Peltzer, Pengpid, McFarlane, and Banyini 2013). One of the strongest correlates of IPV that has received a lot of attention in the academic literature is romantic relationship satisfaction (O’Leary et al. 1989). Not surprisingly, previous research has repeatedly resulted in findings indicating a negative association between IPV and satisfaction (e.g., Panuzio and DiLillo 2010). However, the vast majority of studies on romantic relationships are based primarily on cross-sectional data, which limits interpretation of results and reveals little about how relationships may become more or less satisfying over time (Karney and Bradbury 1995). In addition, since individuals’ relationship status, partners, and the nature of the relationship itself can change, it is important to look at changes in rates of relationship aggression and to examine how these changes might effect partners’ satisfaction with their current relationships. However, this point has been relatively ignored in the literature. Thus, the purpose of the present study was to examine the impact of changes in rates of IPV over time on individuals’ relationship experiences, specifically, on their levels of relationship satisfaction.

Lawrence and Bradbury (2007) draw attention to the importance of clarifying the temporal nature of IPV in intimate relationships, reasoning that while evidence of stability would draw attention to between-subjects explanatory factors, such as personality characteristics, evidence of change would draw attention to within-subject or within-marriage explanatory factors, such as stress in other areas of an individual’s life or communication issues between partners. Studies examining temporal changes in IPV have reached three main conclusions (Lawrence and Bradbury 2007). First, rates of aggression in relationships tend to decrease over time (Jacobson et al. 1996; O’Leary et al. 1989; Vickerman, and Margolin 2008). In a study by O’Leary et al. (1989), 31 % of men and 44 % of women engaged in physically aggression towards their partner pre-marriage. At 18 months post-wedding these numbers had reduced to 27 % for men and to 36 % for women and at 30 months post-wedding to 25 % for men and to 32 % for women. This reduction in aggression over time was found to be significant for women, however, not for men, highlighting the potentially moderating role of gender in this association. Second, relationship aggression tends to be continuous, that is, an aggressive act in a relationship is not likely to be an isolated event (Capaldi et al. 2003; O’Leary 1999; Schumacher, and Leonard 2005). For example, Capaldi et al. (2003) assessed young couples over a 2 ½-year period and found that there was persistence in any physical aggression across time in the group of couples who stayed together. In fact, 60 % of men and 68 % of women, who had engaged in physical aggression towards their partner at age 18 to 19, continued to engage in aggression towards their partner 2 years later. Third, changes in aggression tend to occur as a function of initial levels of severity (Lawrence, and Bradbury 2007; Quigley, and Leonard 1996). Lawrence and Bradbury (2007) studied 172 newlywed couples over the first 4 years of marriage. They found that couples, who initially experienced no aggression, did not experience any aggression over time, while couples, who initially experienced moderate aggression, tended to continue to experience moderate aggression over time, and couples, who initially experienced severe aggression, tended to experience a decline in aggression over time.

In addition to examining the temporal nature of changes in IPV, researchers have been interested in studying the negative association between IPV and romantic relationship satisfaction. For example, in a study by Panuzio and DiLillo (2010), newlyweds’ physical, psychological, and sexual IPV perpetration during the first year of marriage, as well as victim marital satisfaction during the second and third years of marriage were assessed. All three types of IPV were negatively correlated with victim marital satisfaction, with psychological IPV being the most consistent correlate. Similarly, Lawrence and Bradbury (2001) found that marital distress and instability were more common in the first 4 years of marriage among couples who initially tended to exhibit aggression towards their partners. Aggression remained a reliable predictor of marital outcomes after controlling for stressful events and negative communication. Similar associations have been reported in other studies using different samples and methodological approaches. For example, Marcus (2012) compared relationship quality among non-violent, unilaterally violent, and mutually violent couples and found that those individuals who experienced violence in their relationships reported lower relationship quality than those individuals who did not experience any violence in their relationships. According to a study by Tang and Lai (2008), the relation between the occurrence of IPV and poor relationship quality also holds in non-Western cultures, such as in China. In sum, intimate partner aggression is a prevalent phenomenon and its negative association with relationship satisfaction is well documented.

However, a limitation of the aforementioned studies is the lack of assessment of partners’ levels of aggression over time. In Panuzio and DiLillo’s (2010) study, as well as Lawrence and Bradbury's (2001) study, the authors only assessed initial levels of aggression. Thus, they were unable to examine the impact of changes in aggression over time on relationship satisfaction. It remains unclear from these previous studies whether the experience of initial aggression by itself leads to lower relationship satisfaction or whether changes in levels of aggression are responsible for couples’ lower satisfaction with their relationships. Assuming that this second alternative is the case, additional questions arise about possible gender differences in the association between changes in IPV and satisfaction. Lawrence and Bradbury (2007) assessed partners’ levels of aggression at four different time points as well as marital discord and dissolution. While husbands’ physical aggression predicted marital discord, wives’ aggression predicted marital dissolution. In addition, in determining marital satisfaction, husbands’ fluctuations in aggression were found to be more influential than wives’ fluctuations in aggression. Thus, it appears that changes in aggression over time, particularly changes in husbands’ aggression, have an impact on partners’ satisfaction with their relationships. Also, it is likely that an individual’s relationship history would have an effect on their current relationship. Over time, people will experience changes in the nature of their romantic relationships, including their experiences of abuse of violence. Thus, changes in relationship violence experienced, regardless of whether violence is used by the same partner or not, are likely to have an effect on an individual’s current relationship. Moreover, although Lawrence and Bradbury’s (2007) study provides valuable information about the association between changes in aggression and relationship satisfaction, it fails to distinguish between the roles individuals may play in IPV (i.e., whether they are the perpetrators or victims of IPV). It is important to distinguish between IPV perpetration and IPV victimization when examining the relation between changes in IPV and partners’ satisfaction, because the role that individuals play in the IPV they experiences might have very differing influences on their feelings of satisfaction.

In addition, it is crucial to examine gender differences in the association between aggression and satisfaction, because gender might be an important moderator of this association (O’Leary et al. 1989). A literature review by Caldwell et al. (2012), for example, indicates that women experience greater decreases in relationship satisfaction as a result of IPV victimization than do men. The authors highlight the relation between gender and power as a possible explanation for these findings. In most cultures, higher status is ascribed to men than to women. As a result, female victims of IPV might feel less powerful and might be more strongly affected by IPV perpetration than male victims. In addition, due to men’s overall greater size and strength, women are more likely to encounter severe outcomes, which might lead to steeper decreases in relationship satisfaction.

A meta-analytic review on marital satisfaction and marital discord as risk markers of IPV by Stith et al. (2008) resulted in similar findings. Results indicate that the association between IPV perpetration and satisfaction might be stronger for men than for women. However, the association between IPV victimization and satisfaction might be stronger for women than for men. Stith et al. (2008) speculate that men who use violence feel more shame than women who use violence and therefore feel less satisfied after using violence than do women. In addition, male victims might not feel as much fear as female victims, and thus, the negative impact of IPV on relationship satisfaction might not be as strong for male victims as for female victims. Findings by Ackerman and Field (2011), however, do not support this previous research. The authors propose that aggression is more harmful to the quality of women’s romantic relationships than to the quality of men’s relationships, regardless of whether the male or the female partner is the perpetrator or victim of this aggression. Their findings show that women experience steeper declines in relationship satisfaction than do men, independent of whether they are the victims or the perpetrators of IPV.

In sum, existing longitudinal studies suggest that although aggression in intimate relationships tends to decrease over time, it tends to be continuous, and changes in aggression tend to occur as a function of initial levels of severity. In addition, a clear link between intimate partner aggression and romantic relationship satisfaction has been established in the academic literature. Since romantic relationships can change, it is important to look at changes in IPV and to examine how these changes might effect partners’ current satisfaction. However, to date and to the best of our knowledge, only one study (Lawrence and Bradbury 2007) examining the association between changes in IPV over time and satisfaction has been conducted. The results of this study indicate that there might be differential impacts of fluctuations in aggression on satisfaction based on gender. Furthermore, the sample size used in Lawrence and Bradbury’s (2007) study was relatively small (164 couples) and thus, conclusions are limited and warrant replication. Clearly, more information on the changes in IPV-relationship satisfaction association is needed and important questions remain about the differential impact of IPV perpetration and IPV victimization on male and female partners.

Young adults may be an especially appropriate sample to examine changes in IPV, because people’s romantic relationships, including the emotions and behaviors that are part of these relationships, are most likely to undergo change during this developmental period. The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) is a nationally representative study that began in 1995 and assessed health-related behaviors during adolescence and young adulthood at four different time points (called “waves”; see Udry and Bearman 2002 for study design). Previous research has made use of the Add Health dataset to investigate IPV, as well as its association with romantic relationship satisfaction (e.g., Ackerman and Field 2011; Marcus 2012). However, to date, no study has used the Add Health dataset to examine the association between temporal changes in IPV perpetration and victimization and relationship satisfaction.

Thus, the present study aimed to examine the changing nature of IPV perpetration and IPV victimization in romantic relationships and the relation of changes in IPV on men and women’s satisfaction with the same or with subsequent relationships using the Add Health dataset. Two hypotheses were tested. In concordance with findings of previous research (e.g., Ackerman and Field 2011; Panuzio and DiLillo 2010), we predicted (1) that increases in both perpetration and victimization over time would be associated with decreased current relationship satisfaction and (2) that the negative impact of temporal increases in IPV on relationship satisfaction would be stronger for women than for men.

Method

Participants

The present study used archival data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) dataset. Analyses were conducted using a sub-sample of individuals who were participants in sections 17 (“Compiling a Table of Relationships”) and 19 (“Relationships in Detail) of Wave III (collected in 2001–2002 and containing a total of 80,709 participants) and section 17 (“Relationships in Detail”) of Wave IV (collected in 2008 and containing a total of 15,216 participants). The sections of the Wave III dataset include information on as many relationships as individual participants desired to list. In order to come up with a final sample to be used for the present study, we screened Wave III participants to only include a sub-sample of individuals who were involved in only one current relationship at the time of study conduction. The goal of this screening was to limit the number of relationships per participant to a manageable and interpretable number by creating a sample that only included information on one single relationship per participant. To do so, we first merged sections 17 and 19 of Wave III and then filtered out those participants, who responded “Yes” to the question, “Are you currently involved in a sexual or romantic relationship with {INITIALS}?” This screening procedure reduced the original sample size to 9844 participants. As a next step, all participants who listed more than one current relationship at Wave III were deleted, resulting in a final Wave III sample of 8279 participants. All of these 8279 individuals also participated in Section 17 of Wave IV, which only included participants who were involved in a current relationship at the time of study conduction, and, thus, made up the final sample for analysis. A total of 2905 men and 4340 women were included in the final sample (1034 participants failed to indicate their gender). The full sample (N = 8279) was used to address Hypothesis 1. In order to address Hypothesis 2, only data from those participants who indicated their gender (N = 7245) were examined. Descriptive statistics on all study variables for both the full sample used to address Hypothesis 1 (N = 8279) as well as the reduced sample used to address Hypothesis 2 (N = 7245) indicated no significant differences between the two samples.

In our Add Health sub-sample, participants ranged in age from 18 to 28 years (M = 22.43, SD = 1.81) at Wave III and from 25 to 34 years (M = 29.11, SD = 1.74) at Wave IV. Due to the nature of the screening procedure, all participants were in a current relationship at Wave III and at Wave IV (although they did not necessarily remain in the same relationship with the same partner from Wave III to Wave IV).

Procedure

Add Health is a study of a nationally representative sample of individuals between the ages of 11 and 32, in which respondents completed in-home interviews at four separate time points (“waves”). The Add Health Study began in 1995 and assessed health-related behaviors among adolescents and their outcomes during young adulthood (see Udry and Bearman 2002 for study design). Upon completion of a pre-test, in-home interviews were conducted on eligible participants. Survey data were then collected through interviews using a CAPI/CASI instrument, meaning that less sensitive questionnaire sections were administered with the assistance of an interviewer (computer-assisted personal interview, or CAPI), while more sensitive questionnaire sections were self-administered using CASI technology (computer-assisted self-interview). Monetary incentives were offered to participants for completing the interviews.

Materials

Intimate Partner Violence

A modified version of the Conflicts Tactics Scales (CTS; Straus 1979) asked participants if they had experienced psychological, physical and/or sexual abuse over the past 12 months. There were four items assessing perpetration (α = 0.68 for Wave III; α = 0.68 for Wave IV) and four items assessing victimization (α = 0.74 for Wave III; α = 0.68 for Wave IV). Examples include, “How often have you slapped, hit, or kicked <PARTNER> ?” and “How often has <PARTNER> slapped, hit, or kicked you?” Items were rated on a 7-point scale from 0 (never) to 6 (more than 20 times). Perpetration and victimization scores on the individual four items were summed to yield overall summed scores. In the present sample, summed scores ranged from 0 to 19 (perpetration) and from 0 to 23 (victimization) at Wave III and ranged from 0 to 16 (for both perpetration and victimization) at Wave IV. The same eight items, in varying order, were asked of participants at Wave III and at Wave IV. Table 1 lists means and standard deviations of summed scores as well as percentages of participants who engaged in one or more acts of perpetration and victimization at Wave III and Wave IV for all participants and for men and for women separately. Perpetration-difference and victimization-difference scores were calculated to assess temporal changes in IPV from Wave III to Wave IV by subtracting Wave III IPV summed scores from Wave IV IPV summed scores such that positive difference scores would indicate an increase in IPV and negative difference scores would indicate a decrease in IPV. In the present sample, the difference scores ranged from −16 (perpetration) to 16 and from −23 to 15 (victimization).

Relationship Satisfaction

Seven items were used to assess participants’ satisfaction with their relationships at Wave IV (α = 0.89; relationship satisfaction was not assessed at Wave III of the Add Health study). Examples include, “We enjoy doing even ordinary, day-to-day things together.” and “I am satisfied with the way we handle our problems and disagreements.” Items were rated on a 5-point scale from −2 (strongly disagree) to +2 (strongly agree). Relationship satisfaction scores of the individual seven items were averaged to yield a mean satisfaction score. In the present sample, mean satisfaction scores ranged from −2 to +2. Table 1 lists means and standard deviations of mean satisfaction scores for all participants as well as for men and for women separately.

Control Variables

Age, ethnicity, education, and household income were assessed at Wave IV using individual items. To assess age, the difference between the year of the interview and respondents’ date of birth was calculated. Participants ranged in age from 25 to 34 years (M = 29.11, SD = 1.74). To assess ethnicity, the item “Indicate the race of the sample member/respondent from your own observation (not from what the respondent said)” from the field interviewer’s report was used. About 65 % of participants were identified as White by the field interviewer. To assess level of education, the item, “What is the highest level of education that you have achieved to date?” was used. The majority of participants either indicated they had completed some college (30.4 %) or had completed college (17.3 %). Finally, to assess household income, the item “Thinking about your income and the income of everyone who lives in your household and contributes to the household budget, what was the total household income before taxes and deductions in {2006/2007/2008}? Include all sources of income, including non-legal sources” was used. The majority of participants either indicated that their total household income was between $50,000 and $74,999 (21.0 %) or between $75,000 and $99,999 (13.4 %). Correlations between all study variables can be found in Table 2.

Results

As can be seen in Table 1, overall, rates of perpetration and victimization decreased from Wave III to Wave IV. A higher percentage of women than men reported that they had been the perpetrators of violence while a higher percentage of men than women reported that they had been the victims of violence. There was a potential decrease in the use of mutual violence from Wave III to Wave IV among both men and women, as indicated by correlations between Wave III and Wave IV IPV perpetration and victimization. At Wave III, the correlation between IPV perpetration and IPV victimization in the overall sample was r = 0.67 (p < 0.001; r = 0.69, p < 0.001 for men; r = 0.66, p < 0.001 for women). At Wave IV, the correlation between IPV perpetration and IPV victimization in the overall sample was r = 0.53 (p < 0.001; r = 53, p < 0.001 for men; r = 0.55, p < 0.001 for women). The IPV perpetration difference and IPV victimization difference scores were also strongly related to one another in the overall sample (r = 0.59, p < 0.001) as well as for men (r = 0.61, p < 0.001) and women (r = 0.59, p < 0.001) separately.

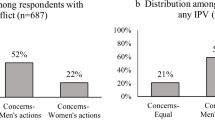

To test the first hypothesis that temporal increases in both perpetration and victimization would be associated with decreased relationship satisfaction, we regressed relationship satisfaction on IPV perpetration-difference and IPV victimization-difference, while simultaneously accounting for all control variables (age, ethnicity, education, and household income). Results partially support the hypothesis. The overall model was found to be significant (R 2 = 0.05, F (6, 5697) = 50.37, p < 0.001). As can be seen in Fig. 1, the association between changes in IPV perpetration and relationship satisfaction was not significant (β = 0.03, p = 0.11). However, a greater increase in IPV victimization from Wave III to Wave IV was related to lower relationship satisfaction at Wave IV (β = −0.14, p < 0.001).

To test the second hypothesis that the negative impact of temporal increases in IPV on relationship satisfaction would be stronger for women than for men, we regressed relationship satisfaction on IPV perpetration-difference, IPV victimization-difference, gender, the interaction of IPV perpetration-difference and gender, and the interaction of IPV victimization-difference and gender, while simultaneously accounting for all control variables (age, ethnicity, education, and household income). Results partially support the hypothesis. The overall model was found to be significant (R 2 = 0.06, F (9, 5694) = 36.69, p < 0.001). Both the gender-by-perpetration difference interaction and the gender-by-victimization difference interaction were found to be significant (β = 0.09, p = 0.005 for perpetration; β = −0.13, p < 0.001 for victimization). As can be seen in Figs. 2 and 3, for men, the association between changes IPV perpetration and relationship satisfaction was not found to be significant (β = −0.03, p = 0.20), while for women, a greater increase in IPV perpetration from Wave III to Wave IV was related to higher relationship satisfaction at Wave IV (β = 0.07, p = 0.002). For both, men and women, a greater increase in IPV victimization from Wave III to Wave IV was related to lower relationship satisfaction at Wave IV and this association was found to be stronger for women (β = −0.06, p = 0.03 for men; β = −0.20, p < 0.001 for women). Table 3 shows each of the variables entered into the regression analyses.

In order to examine which kinds of violent acts were particularly responsible for driving the significant associations between men’s and women’s increases in IPV and their levels of satisfaction, regression analyses for Hypothesis 2 were re-run by including the difference scores for all individual IPV perpetration and IPV victimization items instead of the IPV summed scores. These analyses indicated that the positive association between changes in IPV perpetration and satisfaction for women was predominantly driven by the item assessing threats of violence (β = 0.20, p = 0.24). The negative association between changes in IPV victimization and satisfaction for women was predominantly driven by the item assessing sexual coercion (β = −0.18, p = 0.11). The negative association between changes in IPV victimization and satisfaction for men was predominantly driven by the item assessing injury (β = −0.15, p = 0.54). For more information on these additional analyses, please contact the first author.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to examine changes in IPV perpetration and victimization among young adults and to examine how these changes might be related to men’s and women’s satisfaction with the same as well as subsequent relationships. In the present sample, overall levels of IPV perpetration as well as victimization decreased from Wave III (23.9 % for perpetration and 22.2 % for victimization) to Wave IV (12.9 % for perpetration and 18.1 % for victimization). A decrease in rates of IPV over time is consistent with previous research (e.g., O’Leary et al. 1989). However, overall rates of IPV in the present sample were lower than rates of IPV found in previous studies. In Lawrence and Bradbury’s (2001) sample, for example, 52 % of couples reported having engaged in violence towards an intimate partner. Discrepancies in rates of IPV between the present study and previous studies might be accounted for by differences in relationship status. While Lawrence and Bradbury’s (2001) sample consisted of newlyweds, the present sample consisted of participants involved in any type of romantic relationship. Unmarried participants might be more likely to switch partners and might, thus, have fewer opportunities to engage in intimate partner aggression, which might account for the lower rates of IPV found in the present study. In addition, it is unclear (due to the design of the Add Health study) whether participants stayed in the same relationship from Wave III to Wave IV or whether they in fact switched partners. This also might have implications for rates of IPV. In addition, overall rates of perpetration were found to be higher among women (14.6-28.9 %) than among men (10.4-16.9 %), while overall rates of victimization were found to be higher among men (22.6-22.8 %) than among women (15.0-22.0 %). Again, this finding is consistent with previous research. In O’Leary et al. (1989) study, for example, rates of IPV perpetration ranged from 32 % to 44 % for women and from 25 % to 31 % for men. If women more frequently engage in aggression, it is reasonable to expect that rates of IPV victimization will be higher among men, as found in the present study.

In addition, findings of the present study indicate that temporal increases in IPV victimization were related to decreased satisfaction, while the association between temporal changes in IPV perpetration and satisfaction was not found to be significant, thereby partially supporting our first hypothesis. Previous research (e.g., Panuzio and DiLillo 2010) has repeatedly shown that, in general, there is a negative association between being the victim of violence in a romantic relationship and individuals’ satisfaction with this relationship. Thus, it is not surprising that temporal increases in victimization would also be related to decreased satisfaction. The association between IPV perpetration and satisfaction has not been studied as extensively. Interestingly, our findings indicate that perpetrators’ relationship satisfaction is not as strongly impacted by increasing rates of IPV as compared to victims’ relationship satisfaction. Again, this finding might be explained by pointing to perpetrators’ higher control over the violence that occurs in the relationship, as they are the ones deciding when IPV is going to occur and when it is not.

Finally, both gender-by-IPV interactions were found to be significant. For women, a greater temporal increase in IPV perpetration was related to higher relationship satisfaction, while for men, the association between temporal increases in IPV perpetration and relationship satisfaction was not found to be significant. For both, men and women, a greater temporal increase in IPV victimization was related to lower relationship satisfaction. This association was found to be stronger for women. These results partially support our second hypothesis that the negative impact of temporal increases in IPV on relationship satisfaction would be stronger for women than for men. While both women and men suffer from being a victim of IPV, women’s victimization is more strongly related to their own satisfaction than men’s victimization. This finding is concordant with previous research (e.g., Ackerman and Field 2011) and might be explained by the fact that the negative consequences that female victims of IPV experience are worse than those consequences that male victims experience (Caldwell et al. 2012). The finding that men’s IPV perpetration was not significantly related to men’s relationship satisfaction is concordant with the finding of the present study that, in general, people’s IPV perpetration is not significantly related to their relationship satisfaction. Male perpetrators might not be as affected by increases in IPV perpetration, because they themselves have control over these increases. Interestingly, however, women’s IPV perpetration was significantly related to their levels of satisfaction, however in the opposite direction of what we predicted in our second hypothesis: For women, we found a positive association between temporal increases in perpetration and relationship satisfaction.

The finding that increases in women’s IPV perpetration was related to higher satisfaction is particularly compelling, especially because the analysis controlled for differences in victimization. As indicated by the correlation analyses between IPV perpetration and victimization, both men and women appear to experience a decrease in mutual violence between Wave III and Wave IV. Thus, it is unlikely that the differences in the IPV perpetration-satisfaction association among men versus women are due to changes in mutual versus one-sided violence. However, it may be that men and women do experience mutual versus one-directional violence differently and thus, are impacted differently by changes in these types of violence in regards to their levels of relationship satisfaction. It may also be that this observed positive association is be due to women’s entry into a new relationship, in which the new male’s retaliatory aggression is less likely. Alternatively, it might be that an increase in women’s perpetration leads them to perceive themselves as more powerful in the relationship. These increased perceptions of power, in turn, might be related to increased relationship satisfaction. In fact, although most previous studies have focused on power playing a role in men’s IPV perpetration, some research has shown that dissatisfaction with the level of power an individual perceives in their relationship is positively associated with IPV perpetration for both men and women (Kaura and Allen 2004). The finding indicating that this positive association between women changes in IPV and satisfaction was predominantly driven by women’s increased use of threats towards their partners may indicate that women derive their feelings of power from the use of psychological aggression against their partner. However, since these speculative findings are based on single-item measures of the different types of IPV and none of these individual items remained a significant predictor of satisfaction in the follow-up regression analyses, more research in this area is clearly warranted.

Limitations

Some qualities of this research limit interpretation of the present findings. The main limitations of the current study lie in the design of the original Add Health study. For example, we were unable to assess whether participants stayed with the same partner from Wave III to Wave IV or whether they in fact might have switched partners. A former victim of violence might not experience any violence at a later point in time, not because of actual decreases in their partner’s levels of perpetration, but because they are now dating a different person. Capaldi et al. (2003), for example, found that stability in levels of aggression was higher for men who stayed with the same partner than for men who re-partnered. Thus, it would be useful to determine whether participants in the present study stayed with the same partners or not, as this might explain the direction and steepness of changes of IPV perpetration and victimization over time. However, the findings of the present study are useful in shedding light on the effects of temporal changes in perpetration and victimization on relationship experiences (i.e., perceptions of satisfaction) in general. It is plausible to assume, based on the current results, that the negative impact of changes in IPV might not only affect individuals’ relationship with the violent partner but might also carry over to new, subsequent relationships that individuals might be involved in at later points in time.

Furthermore, relationship satisfaction was not assessed at Wave III of Add Health, which prevented us from examining changes in relationship satisfaction over time and to control for initial (i.e., Wave III) relationship satisfaction in our regression analyses that examined the association between temporal changes in IPV from Wave III to Wave IV and satisfaction at Wave IV. In addition, because only one members of the dyad provided information on the study variables, it is impossible to determine whether increases in one partner’s levels of perpetration might be related to increases in the other partner’s levels of victimization as well as increases in the other partner’s levels of perpetration. Also, the use of two waves of data and the use of self-report and single-reporter measurement to assess both, IPV and satisfaction, might limit the interpretation of the current results. Finally, we observed a reduction in the sample sizes used to examine Hypotheses 1 and 2. However, according to comparisons of descriptive statistics of the study variables in the full versus the reduced sample, the survey sample for the evaluation of Hypothesis 2 was not found to be different in critical ways from the evaluation of Hypothesis 1.

Research Implications

Three main implications can be drawn from the present study that might have important implications for future research. First, the findings of the present study underscore that it is important to not only examine rates of relationship violence at one point in time but to also track how violence changes over time and how these changes in violence might be related to other constructs, such as relationship satisfaction. Thus, it is important for researchers to regard IPV as a temporally dynamic phenomenon (Lawrence and Bradbury 2007).

Second, we were surprised to find differing impacts of changes in IPV perpetration and victimization on individuals’ levels of relationship satisfaction. While the association between changes in IPV perpetration and satisfaction was not significant, increases in victimization over time were related to decreases in relationship satisfaction. Since most previous studies have only assessed IPV victimization and studies on the impacts of IPV perpetration on relationship satisfaction are limited, we call for researchers to distinguish between perpetration and victimization in future studies. Doing so might shed more light on the issues discovered in the present study.

Finally, the consideration of gender differences revealed important similarities and distinctions in men and women’s IPV and the relation of temporal increases in perpetration and victimization to their relationship satisfaction. Consistent with previous research, we found that, even though both men and women’s relationship satisfaction was negatively impacted by IPV victimization; this decrease in satisfaction was stronger for women. The association between perpetration and satisfaction was found to be non-significant for men and for women. These findings highlight the importance of assessing gender differences when examining the effects of IPV in future research.

Future studies should be constructed to take into account the aforementioned implications. In addition, limitations of the present study could be addressed by tracking partners over time to assess whether they stay together or separate; by assessing relationship satisfaction at all time points; by collecting data from both members of the dyad; by assessing IPV at more than two points in time; and by including measures other than self report to assess IPV and satisfaction, such as observational measures.

Clinical and Policy Implications

The same three implications as discussed in the context of possible future research might have implications for clinical practice and policy. First, practitioners and policy-makers need to acknowledge that IPV is a temporally dynamic phenomenon (Lawrence and Bradbury 2007). Assessing aggression at more than one time point and acknowledging that aggression in a relationship is not stable but might change (both, when individuals stay with the same partner as well as when they re-partner, see Capaldi et al. 2003) may allow to design the most effective treatment plans possible.

Second, it is important for practitioners to take into account the role that an individual plays in IPV. Differing treatment plans should be developed for perpetrators and victims of intimate partner aggression. It might be advisable to address the seemingly absent impact of IPV on perpetrators’ relationship satisfaction in therapy sessions in order to increase motivation for change and feelings of closeness to one’s partner.

Third, since the present findings show that men and women’s relationship satisfaction was impacted differently as a result of IPV, it is important to treat male and female victims and perpetrators of IPV differently. Thus, findings of the present study might help practitioners in developing effective treatment plans for individuals as well as for couples and to adjust interventions for male versus female victims and perpetrators of IPV.

Conclusion

Bearing the limitations discussed in mind, it can be concluded from the present study (1) that aggression in romantic relationships is a temporally dynamic phenomenon, (2) that IPV perpetration and IPV victimization have differing impacts of relationship satisfaction, and (3) that the impacts of IPV perpetration and victimization might differ by gender. These findings are relevant to those studying relationship violence as well as to those involved in the treatment of partners who are involved in violent relationships.

References

Ackerman, J., & Field, L. (2011). The gender asymmetric effect of intimate partner violence on relationship satisfaction. Violence and Victims, 26(6), 703–724.

Caldwell, J. E., Swan, S. C., & Woodbrown, V. (2012). Gender differences in intimate partner violence outcomes. Psychology of Violence, 2(1), 42–57.

Capaldi, D. M., Shortt, J. W., & Crosby, L. (2003). Physical and psychological aggression in at-risk young couples: stability and change in young adulthood. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 49, 1–27.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. (2013). Intimate Partner Violence. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/

Jacobson, N. S., Gottman, J. M., Gortner, E., Berns, S., & Shortt, J. (1996). Psychological factors in the longitudinal course of battering: when do the couples split up? when does the abuse decrease? Violence and Victims, 11(4), 371–392.

Karney, B. R., & Bradbury, T. N. (1995). The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: a review of theory, method, and research. Psychological Bulletin, 118, 3–34.

Kaura, S. A., & Allen, C. M. (2004). Dissatisfaction with relationship power and dating violence perpetration by men and women. Journal Of Interpersonal Violence, 19(5), 576–588.

Lawrence, E., & Bradbury, T. N. (2001). Physical aggression and marital dysfunction: a longitudinal analysis. Journal of Family Psychology, 15(1), 135–154.

Lawrence, E., & Bradbury, T. (2007). Trajectories of change in physical aggression and marital satisfaction. Journal of Family Psychology: JFP: Journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 21(2), 236–247.

Marcus, R. (2012). Patterns of intimate partner violence in young adult couples: nonviolent, unilaterally violent, and mutually violent couples. Violence and Victims, 27(3), 299–314.

O’Leary, K. D. (1999). Developmental and affective issues in assessing and treating partner aggression. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 6, 400–414.

O'Leary, K., Barling, J., Arias, I., Rosenbaum, A., Malone, J., & Tyree, A. (1989). Prevalence and stability of physical aggression between spouses: a longitudinal analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 57(2), 263–268.

Panuzio, J., & DiLillo, D. (2010). Physical, psychological, and sexual intimate partner aggression among newlywed couples: longitudinal prediction of marital satisfaction. Journal of Family Violence, 25(7), 689–699.

Peltzer, K., Pengpid, S., McFarlane, J., & Banyini, M. (2013). Mental health consequences of intimate partner violence in Vhembe district, South Africa. General Hospital Psychiatry, 35(5), 545–550.

Quigley, B. M., & Leonard, K. E. (1996). Desistance of husband aggression in the early years of marriage. Violence and Victims, 11, 355–370.

Schumacher, J. A., & Leonard, K. E. (2005). Husbands’ and Wives’ marital adjustment, verbal aggression, and physical aggression as longitudinal predictors of physical aggression in early marriage. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(1), 28–37.

Stith, S. M., Green, N. M., Smith, D. B., & Ward, D. B. (2008). Marital satisfaction and marital discord as risk markers for intimate partner violence: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Family Violence, 23(3), 149–160.

Straus, M. A. (1979). Measuring intra-family conflict and violence: the conflict tactics scale. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 41, 75–88.

Tang, C., & Lai, B. (2008). A review of empirical literature on the prevalence and risk markers of male-on-female intimate partner violence in contemporary China, 1987–2006. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 13(1), 10–28.

Testa, M., & Leonard, K. E. (2001). The impact of marital aggression on women’s psychological and marital functioning in a newlywed sample. Journal of Family Violence, 16(2), 115–130.

Udry, J. R., & Bearman, P. S. (2002). New methods for new perspectives on adolescent sexual behavior. In R. Jessor (Ed.), New perspectives on adolescent sexual behavior. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vickerman, K. A., & Margolin, G. (2008). Trajectories of physical and emotional marital aggression in midlife couples. Violence and Victims, 23(1), 18–34.

Acknowledgments

This research uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and funded by grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth). No direct support was received from grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ulloa, E.C., Hammett, J.F. Temporal Changes in Intimate Partner Violence and Relationship Satisfaction. J Fam Viol 30, 1093–1102 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-015-9744-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-015-9744-4